Significance

High-affinity molecular recognition has carried the mysteries of life processes and serves as the foundation for the biomedical applications of macrocyclic receptors. Achieving the ultrahigh affinity binding of macrocyclic hosts remains a formidable challenge. Drawing inspiration from the biotin/avidin system, we have introduced the “Assembly-Enhanced Recognition” (AER) strategy. An amphiphilic azocalix[4]arene derivative QAAC4A12C was designed and demonstrated to exhibit ultrahigh binding affinities (up to 1012 M−1) in water phase. The AER strategy not only paves the way for artificial receptors with exceptional recognition properties but also propels the exploration of related applications.

Keywords: high-affinity recognition, noncovalent assembly, biomimetic strategy, azocalixarene, controlled release

Abstract

On the one hand, nature utilizes hierarchical assemblies to create complex biological binding pockets, enabling ultrastrong recognition toward substrates in aqueous solutions. On the other hand, chemists have been fervently pursuing high-affinity recognition by constructing covalently well-preorganized stereoelectronic cavities. The potential of noncovalent assembly, however, for enhancing molecular recognition has long been underestimated. Inspired by (strept)avidin, an amphiphilic azocalix[4]arene derivative capable of assembly in aqueous solutions has been explored by us and demonstrated to exhibit ultrahigh binding affinity (up to 1012 M−1), which is almost four orders of magnitude higher than those reported for nonassembled azocalix[4]arenes. An ultrastable azocalix[4]arene/photosensitizer complex has been applied in hypoxia-targeted photodynamic therapy for tumors. These findings highlight the immense potential of an assembly-enhanced recognition strategy in the development of the next generation of artificial receptors with appropriate functionalities and extraordinary recognition properties.

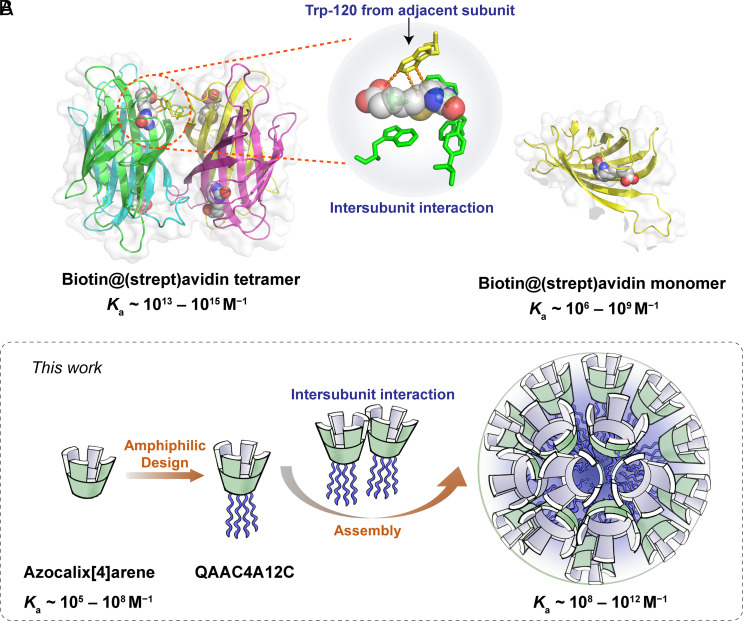

Molecular recognition and so-called self-assembly (1, 2) are two fundamental intermolecular processes vital for the maintenance of life in organisms. Through intricate folding and assembly, proteins and enzymes create preorganized cavities in a meticulous manner, thereby facilitating molecular recognition in water with high affinity and fidelity (3, 4). A notable example (5–7) is (strept)avidin, a tetrameric protein with hydrophobic pockets in each of its four monomers, exhibiting remarkable binding affinity (Ka = 1013–1015 M−1) for four biotin molecules. Disrupting this assembly by making the protein monomeric results (Fig. 1A) in a significant affinity reduction (8), often by at least a factor of 10,000. This reduction occurs not only because a portion of the binding sites within the pocket originates (9, 10) from neighboring subunits but also due to the enhanced conformational rigidity (11) for the binding pockets upon forming the tetrameric assembly. This assembly-enhanced recognition (AER) mechanism results in the astonishingly high affinity that has led to the widespread utilization (12–14) of the biotin/(strept)avidin pair in various biotechnological applications.

Fig. 1.

Assembly-enhanced recognition in natural and artificial systems. (A) Biotin/(strept)avidin pair (6). Every binding pocket of the tetrameric (strept)avidin shows ultrastrong (1013 to 1015 M−1) binding affinity toward biotin, while the monomer displays significantly decreased (106 to 109 M−1) binding affinity. In this case, adjacent subunits contribute additional recognition sites for the binding pockets of (strept)avidin. Intersubunit interactions provided by Trp-120 (from another subunit) with biotin are essential for recognition and biotin-induced tighter subunit association (10). (B) Recognition properties of azocalix[4]arenes. In general, azocalix[4]arenes display moderate (105 to 108 M−1) affinities toward organic guests. The amphiphilic calixarene QAAC4A12C, however, can self-assemble into nanomicelles and display significantly enhanced affinities (108 to 1012 M−1).

By contrast, over 95% of synthetic receptors known today (15–17) struggle to achieve biomolecular range affinities (Ka > 106 M−1), with only a handful of exceptions achieving nanomolar affinities (18–24). These low Ka values present a significant limitation when it comes to applications since receptor–substrate pairs with low affinities are susceptible (25, 26) to dissociation caused by dilution or interferences. The development of new ultrahigh-affinity synthetic pairs holds a lot of promise across numerous fields, including protein purification (27), drug sequestration (28), bioconjugation (29), and drug delivery (30, 31). Nevertheless, conventional strategies aimed at enhancing affinities, which rely on the covalent synthesis of highly preorganized cavities (32), have encountered bottlenecks because of enthalpy–entropy compensation constraints (33). Enhancing preorganization is a critical pathway for reducing entropy loss (34), while self-assembly serves as an effective strategy to augment preorganization (35). However, it appears that the impact of assembly on (enhancing) molecular recognition has been overlooked for too long.

In this context, we employed a positively charged, amphiphilic functionalized azocalix[4]arene derivative, QAAC4A12C (Fig. 1B), in order to showcase the immense potential of the AER strategy. This deep-cavity receptor assembles readily into nanomicelles in aqueous solutions and exhibit Ka values of 108 to 1012 M−1 toward a series of bioactive substrates in aqueous solution. In contrast, positively charged azocalix[4]arene, which cannot form assemblies, only gives rise to Ka values in the range of 105 to 108 M−1. In line with (strept)avidin, the significantly enhanced binding affinity of the QAAC4A12C assembly can be attributed to the additional binding sites and hydrophobic surfaces provided by neighboring subunits, in addition to the enhanced rigidity of the cavities. Unlike (strept)avidin and other ultrastrong synthetic receptors that fail to undergo controlled release of tightly bound substrates, the inherent redox-cleavable feature of the azo bond enables (36) azocalix[4]arenes to release rapidly and completely bioactive substrates under hypoxic microenvironments. This feature makes these ultrahigh-affinity pairs particularly valuable (37) in biomedical applications. Specifically, we chose a complex of QAAC4A12C with a porphyrin photosensitizer (TPPS) to investigate its application in tumor-targeted photodynamic therapy (PDT). Benefiting from ultrahigh affinity (Ka = 4.4 × 1011 M−1), the TPPS/QAAC4A12C complex displays much better interference resistance in biofluids and significantly reduced off-target dissociation compared with the control pair Fl/QAAC4A12C which has a lower affinity (Ka = 2.1 × 108 M−1). As a result, the TPPS/QAAC4A12C complex exhibits superior PDT therapy efficacy. These findings underscore the enormous potential of the AER strategy for crafting the next generation of synthetic receptors capable of rivaling their biological counterparts, not only in recognition properties but also in functionalities.

Results

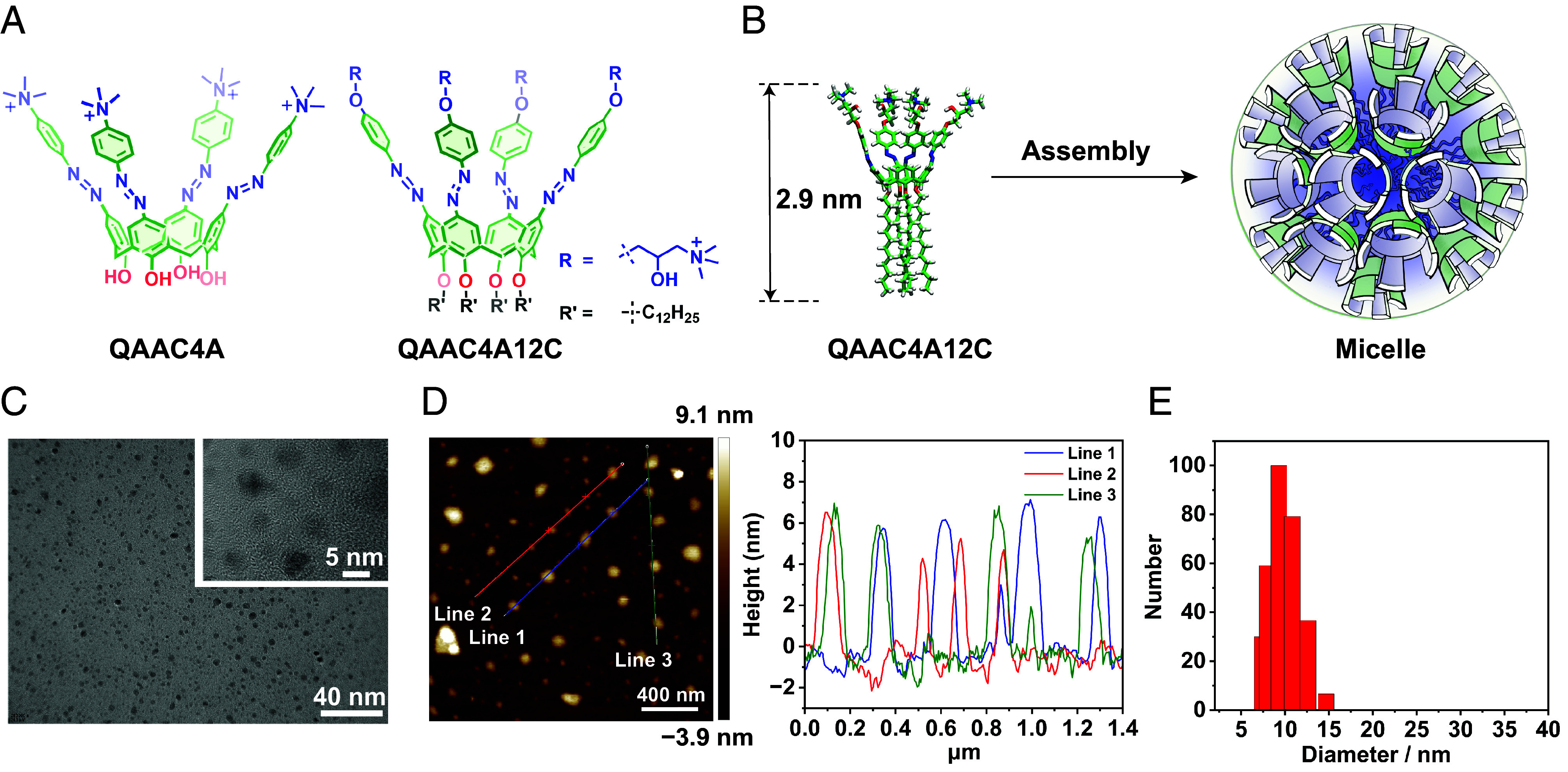

In an attempt to mimic the AER mechanism of (strept)avidin, we selected (Fig. 2 A and B) an amphiphilic-modified azocalix[4]arene derivative (38), QAAC4A12C, as the macrocyclic receptor in our investigation based on two considerations. First, the amphiphilic structure of QAAC4A12C promotes (39) its tendency to assemble in aqueous environments. Second, the deep hydrophobic cavity of azocalix[4]arenes is not entirely enclosed, featuring distinct gaps between the four aromatic sidewalls. Consequently, after forming assemblies, adjacent azocalix[4]arene subunits may fill these gaps, thereby increasing the number and efficiency of interaction sites with encapsulated guests, enhancing cavity enclosure, and strengthening the hydrophobic effect of the cavity.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of QAAC4A12C assembly and recognition. (A) Structure formulas of QAAC4A and QAAC4A12C. (B) Graphical display of QAAC4A12C self-assembling into a micelle. (C) TEM images of QAAC4A12C micelles (1.0 μM in water), showing the formation of small micelles with an average diameter of 4.2 nm. (D) AFM image and height section of QAAC4A12C micelles (1.0 μM in water), demonstrating micelles height of 4 ~ 6 nm, consistent with the TEM measurements. (E) DLS results from QAAC4A12C micelles (2.0 μM in water), indicating an average hydrated diameter of 9.6 nm.

In order to illustrate the impact of assembly on recognition properties, we synthesized another positively charged azocalix[4]arene, namely QAAC4A, which lacks four long alkyl chain substituents, resulting in significantly weaker self-assembly. This compound serves as a control for comparative purposes. Notably, despite containing large apolar and hydrophobic components, QAAC4A12C still exhibits moderate water solubility (>2.0 mg/mL), as a result of the formation of amphiphilic assemblies. The morphology of the self-assembled QAAC4A12C in water (1.0 μM) was characterized using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S2) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) (Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Fig. S3), both of which confirmed that the diameter of the micelles ranges from 4 to 6 nm. The hydrated diameter of the micelles, determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements (Fig. 2E), was found to be 9.6 ± 1.1 nm on average. The discrepancy between the diameter obtained from AFM/TEM measurements and DLS can be attributed to the shrinkage of nanoparticles in the dry conditions employed during AFM/TEM measurements. QAAC4A12C micelles remained stable in water over a period of 14 d (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) and displayed no significant difference in DLS measurement after binding with guest or in biological media (SI Appendix, Figs. S5 and S6). We also determined the radius of gyration of the QAAC4A12C assembly to be approximately 25.6 nm by small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) method (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). The discrepancies between the SAXS and dynamic light scattering (DLS) results may stem from the higher concentration utilized in the SAXS measurements (1.0 mM), which could have led to the formation of secondary aggregates at elevated concentrations. However, it is not easy to measure the critical aggregation concentration accurately in the concentration range of <1.0 μM.

By contrast, QAAC4A, because of the absence of four long alkyl chains, exhibits no discernible signs (SI Appendix, Fig. S8) of assembly formation in water at concentration under 100 μM, indicating a significantly weaker tendency to assemble compared to QAAC4A12C. Consequently, we selected a concentration of around 1.0 μM to assess the binding affinities of QAAC4A12C (assemblies) and QAAC4A (molecularly dispersed), thereby elucidating the impact of assembly on recognition properties.

The host–guest binding affinities of QAAC4A12C and QAAC4A toward a series of hydrophobic guests were subsequently accessed in HEPES buffer by carrying out titration experiments. Given that azocalix[4]arenes are known to be effective fluorescence quenchers, competitive fluorescence titrations were conducted using Fl as the indicator and the boron cluster (Na2B12H12) as the competitor to determine the binding affinities, since high concentrations of boron clusters have no influence on fluorescence and UV spectra of tetraphenylporphyrins.

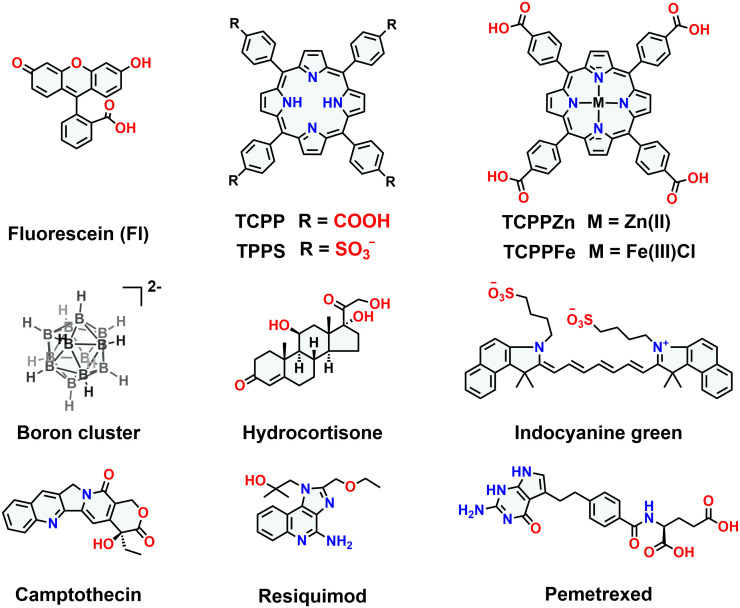

QAAC4A12C exhibits nanomolar affinities (108 to 109 M−1) toward the two fluorescent dyes (Fl and indocyanine green), as well as four drug molecules, i.e., camptothecin, hydrocortisone, resiquimod, and pemetrexed (Fig. 3, Table 1, and SI Appendix, Figs. S9–S16). Remarkably, QAAC4A12C also demonstrates ultrahigh 1:1 binding affinities ranging from 1010 to 1012 M−1 toward a series of tetraphenylporphyrins. Notably, one metalloporphyrin derivative, TCPPFe, shows the highest binding affinity (4.2 × 1012 M−1) with QAAC4A12C among the four tested tetraphenylporphyrins. These binding affinities are almost comparable to those observed (1013 to 1015 M−1) in the biotin/(strept)avidin pairs.

Fig. 3.

Chemical formulas of guest molecules.

Table 1.

Binding affinities of QAAC4A12C, QAAC4A, and related guest molecules

| Guests | Ka/M−1 | Ka/M−1 |

|---|---|---|

| QAAC4A12C | QAAC4A | |

| Fluorescein | 2.1 × 108* | 6.3 × 105* |

| Boron cluster | 5.3 × 108* | 3.1 × 106* |

| TCPP | (4.0 ± 0.5) × 1011† | (5.6 ± 1.3) × 107†, ¶ |

| (3.0 ± 0.7) × 1011‡ | ||

| TCPPZn | (3.9 ± 0.5) × 1010† | (5.6 ± 1.3) × 107†¶ |

| (3.1 ± 1.3) × 1010‡ | ||

| TPPS | (4.4 ± 1.0) × 1011† | (4.6 ± 1.1) × 107†,¶ |

| (2.8 ± 1.0) × 1011‡ | ||

| TCPPFe | (4.2 ± 0.2) × 1012§ | –# |

| Camptothecin | 1.9 × 108* | |

| Hydrocortisone | 1.7 × 109* | 2.1 × 105* |

| Resiquimod | 1.7 × 108* | 7.3 × 105* |

| Indocyanine green | 1.6 × 108* | 2.0 × 107* |

| Pemetrexed | 1.5 × 109* | 2.5 × 106* |

The 1:1 binding constants of QAAC4A12C and QAAC4A toward different guests were measured in HEPES buffer (10 mM, pH = 7.4, 25 °C).

*Data from ref. 40.

†Measured by competitive fluorescence titration using Fl as the indicator.

‡Measured by competitive fluorescence titration with Na2B12H12 as the indicator.

§Measured by competitive UV-Vis titration using Na2B12H12 as the competitor.

¶2:1 Host: guest complex.

#Not measured.

In order to validate the reliability of the ultrahigh binding affinities of QAAC4A12C/ tetraphenylporphyrin pairs, UV-Vis competitive titrations were also performed. This approach was chosen on account of the noticeable changes in the UV-Vis spectra of the tetraphenylporphyrin derivatives upon binding with QAAC4A12C. The results from UV-Vis competitive titrations (Table 1) were found to be in excellent agreement with those obtained from the fluorescence titrations, i.e., both spectroscopic titrations unequivocally confirmed that QAAC4A12C recognizes the four tetraphenylporphyrins with extraordinarily high affinities.

As a comparison, QAAC4A demonstrates notable lower recognition affinities (105 to 107 M−1, Table 1) toward the two dyes and four drugs compared to QAAC4A12C. Therefore, although QAAC4A12C shares a similar azocalix[4]arene cavity structure with QAAC4A, the binding affinities and modes diverge dramatically. We have collected (SI Appendix, Figs. S17 and S18 and Table S1) recognition data for other previously reported negatively charged azocalix[4]arenes measured under nonassembled states, which are generally within the range of 105 to 107 M−1. It follows that the formation of nanomicellar assemblies is pivotal for the exceptional ultrahigh binding affinities of QAAC4A12C in comparison with QAAC4A and other azocalix[4]arenes.

To avoid complex heat effects in the QAAC4A12C assembly as the guest equivalents increase to more than one equivalent, we chose an alternative approach: measuring the heat changes upon adding low guest equivalents to estimate the enthalpy change (SI Appendix, ITC Titration for ΔH Measurement). The Gibbs free energy changes (ΔG) were derived from the binding constants obtained via fluorescence titrations, enabling us to determine the entropy effect (ΔS) of the binding process. Table 2 summarizes the thermodynamic parameters of the host–guest binding processes involving Fl, Na2B12H12, and TPPS as guests (SI Appendix, Figs. S19–S24). Notably, there is not a significant difference in ΔH between QAAC4A12C (assembled) and QAAC4A (nonassembled) when binding guests, the primary distinction lies in the entropy effect. Specifically, upon assembly formation, the entropy loss upon guest binding is markedly reduced, and it may even turn into an entropy gain process. This favorable entropy effect may have two possible sources: 1) the formation of the assembly reduces conformational freedom, decreasing the entropy loss during the binding process; 2) since the “classic” hydrophobic effect (41) is considered entropy-driven, the favorable entropy effect of the assembly when binding guests may also stem from the enhanced hydrophobic effect of the cavity. In other words, assembly formation increases the accessible hydrophobic surface area of the cavity, thereby resulting in a stronger (classic) hydrophobic effect upon guest binding (42).

Table 2.

Thermodynamic parameters during the complexation

| Host–guest pair | Ka M−1 | ΔG* kcal/mol | ΔH† kcal/mol | −TΔS kcal/mol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QAAC4A12C-Fl | 2.1 × 108 | −11.2 | −(6.1 ± 0.5) | −5.1 |

| QAAC4A-Fl | 6.3 × 105 | −7.8 | −(6.7 ± 1.1) | −1.1 |

| QAAC4A12C-Na2B12H12 | 5.0 × 108 | −11.8 | −(7.4 ± 0.8) | −4.4 |

| QAAC4A-Na2B12H12 | 3.1 × 106 | −8.8 | −(6.6 ± 0.9) | −2.2 |

| QAAC4A12C-TPPS | 4.4 × 1011 | −15.8 | −(15.6 ± 0.4) | −0.2 |

| QAAC4A-TPPS | 4.6 × 107 | −10.4 | −(16.5 ± 1.1) | 6.1 |

*The ΔG was calculated by Ka obtained from fluorescence titration.

†The ΔH was measured by ITC in HEPES buffer (10 mM, pH = 7.4, 25 °C), and the −TΔS was calculated by ΔG − ΔH.

To further elucidate the AER strategy, we performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations on QAAC4A12C monomers and aggregates. The resulting root mean square deviation (RMSD) analysis (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Figs. S25 and S26) quantifies the rigidity of the molecular conformations. The RMSD profiles of QAAC4A12C in dimeric and trimeric forms were similar to that of the monomeric state. However, a notable decrease in RMSD was observed as the number of molecules increased (from 3.45 nm for the monomer to 2.25 nm for the octamer), indicating enhanced molecular rigidity. Consistent with findings by Inoue, the entropy loss exhibited an approximately linear correlation with the enthalpy change, with the slope serving as an indicator of receptor rigidity (43). The increased rigidity of QAAC4A12C in micellar structures effectively reduced entropy loss during the recognition process.

Fig. 4.

RMSD distribution analysis of monomer and aggregates of QAAC4A12C molecules by MD simulation. See SI Appendix, Molecular Simulations for details.

Macrocyclic carriers have emerged as a promising means of drug delivery, offering unique advantages (44–46). These delivery systems have faced the challenge of drugs leaking from the cavity during in vivo circulation, resulting in off-target drug activation and damage to normal tissues. We believe that ultrahigh-affinity receptors are likely to provide a welcome change and overcome this obstacle. Besides, azobenzene modification of calixarene provides a unique cleavable motif using sodium dithionite (SDT) or microsomes as the mimic of hypoxia microenvironments (Fig. 5A and SI Appendix, Fig. S27), enabling hypoxia-induced substrate release in tumor microenvironments. Therefore, the combination of ultrahigh hosting ability and the unique stimuli-responsiveness of QAAC4A12C position them as highly promising drug carriers for therapeutic applications.

Fig. 5.

Hypoxia-responsive supramolecular photosensitizer delivery with ultrahigh binding affinity. (A) Reduction of QAAC4A12C (5.0 μM in PBS buffer, pH = 7.4, 25 °C) by rat microsome (80 μg/mL) with NADPH (100 μM), under a hypoxia environment. (B) Schematic illustration demonstrating the interferent resistance and responsive effect of QAAC4A12C in bioapplications. The ultrahigh binding complex does not dissociate until reaching hypoxia microenvironment such as a tumor. The fluorescence and photoactivity of a photosensitizer are “turned on” after being released from the QAAC4A12C carrier. (C) Binding constants between dyes and QAAC4A12C in DMEM medium, measured by ultrafiltration and direct fluorescence titration. In the case of the ultrafiltration method, the host–guest complex (50/50 μM) was centrifuged in an ultrafiltration tube, and the concentration of the dissociated dye in the filtrate was measured by UV-Vis spectroscopy, leading to the Ka value. (D) Ex vivo imaging of tumor and major organs harvested from 4T1 bearing mice after TPPS or TPPS/QAAC4A12C were intravenously injected at different time periods. (E and F) Quantitative analysis of ex vivo imaging of tumor and major organs harvested from 4T1 bearing mice after TPPS/QAAC4A12C or TPPS were injected. (G) Tumor volumes of each group after different treatments. Data were recorded from day 1 to day 15.

Initially, the fluorescence of TPPS was shown to be quenched by 71% and the 1O2 production rate was reduced by 90% upon complexation in water (SI Appendix, Fig. S28). These observations indicate that the phototoxicity of TPPS is turned “off” upon complexation and is activated on being released from the cavity of QAAC4A12C.

We also investigated the stability of TPPS/QAAC4A12C complex in a biological environment using Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM). Fl and TCPP were also employed as comparisons in making the measurements. Direct fluorescence titration was conducted in DMEM to measure the (apparent) binding constants of the recognition pairs (Fig. 5C) at the concentration of 1.0 μM for QAAC4A12C. Notably, the binding affinity of Fl/QAAC4A12C in DMEM decreased to 1.3 × 104 M−1, indicating significant dissociation of this complex at micromolar concentrations in biofluids. In contrast, TPPS/QAAC4A12C and TCPP/QAAC4A12C still exhibit high affinities (1.3 × 107 and 1.1 × 107 M−1, respectively) under the same conditions (SI Appendix, Figs. S30 and S31). In order to verify these results, an ultrafiltration method was exploited (Fig. 5C) to estimate the binding constants at the concentration of 50 μM for QAAC4A12C. When the 1:1 complex of the dye and QAAC4A12C (50/50 μM) was subjected to ultrafiltration in DMEM, the absorbance of free Fl detected in the filtrate indicated 64% of the Fl/QAAC4A12C complex had dissociated. Accordingly, the Ka value for Fl/QAAC4A12C in DMEM was estimated to be 1.5 × 104 M−1. In contrast, the concentrations of free TPPS and TCPP in the filtrates were both below 1.0 μM according to UV-Vis spectroscopy, suggesting the Ka values for TPPS/QAAC4A12C and TCPP/QAAC4A12C were both higher than 5 × 107 M−1. These results demonstrate that, although the Fl/QAAC4A12C complex showed a good affinity of 2.1 × 108 M−1 in HEPES buffer, it undergoes significant leakage in DMEM at micromolar concentrations. In contrast, both TPPS/QAAC4A12C and TCPP/QAAC4A12C complexes remain almost completely bound under the same conditions, highlighting the importance of ultrahigh affinities for supramolecular complexes applied in biofluids. The flow cytometry analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S32) of cell uptake experiments also confirmed this conclusion.

Bioimaging and PDT experiments (Fig. 5B) were conducted using TPPS/QAAC4A12C pair (Ka = 4.4 × 1011 M−1) on 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. In the bioimaging experiments (Fig. 5 D–F), mice treated with free TPPS showed not only intense fluorescence at the tumor site but also moderate to strong fluorescence at other organs, e.g., spleen, lung, and kidney. In comparison, the TPPS/QAAC4A12C group displayed strong fluorescence mainly located at the tumor with moderate to weak fluorescent intensity at other positions. The tumor-to-organ ratio of the fluorescence signal was noticeably increased (SI Appendix, Fig. S33) in lung and spleen after complexation. These results indicate relatively effective prevention of nonspecific leakage and tumor-targeted release of TPPS from the QAAC4A12C nanocarrier. Similar experiments were carried out using Fl (Ka = 2.1 × 108 M−1) as the imaging dye. In contrast, the results of the “Fl” and “Fl/QAAC4A12C” groups showed no significant difference (SI Appendix, Figs. S34–S36) in the bioimaging experiments, likely because the binding affinity is not strong enough to prevent off-target leakage of Fl from QAAC4A12C in vivo.

In the PDT experiment, the tumor-bearing mice were divided into six groups randomly, and different treatments were administered. The control groups of “PBS + L” (L refers to light irradiation), “TPPS” and “TPPS/QAAC4A12C” exhibited (Fig. 5G and SI Appendix, Figs. S37–S39) negligible effects on tumor suppression compared to the “PBS” group, indicating that neither laser irradiation alone nor TPPS alone had any tumor suppression effect. Meanwhile, the “TPPS + L” group exhibited a tumor growth inhibition of 41%. In contrast, complexing TPPS with QAAC4A12C improved significantly the tumor suppression effect of PDT, as evidenced by the tumor growth inhibition of the “TPPS/QAAC4A12C + L” group, which increased to 79%. The superior therapeutic efficacy was attributed to i) the enhanced cell uptake of TPPS upon complexation with QAAC4A12C and ii) the efficient hypoxia-triggered release of TPPS from the carriers, leading to increased accumulation in the tumor. Additionally, toxicity was evaluated through body-weight measurement and tissue section analysis. The weight of the mice did not change significantly among the groups, and the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of main organ sections revealed (SI Appendix, Figs. S40 and S41) no evident organ damage during therapy. Taken together, this ultrahigh binding receptor QAAC4A12C has demonstrated excellent potential as a photosensitizer carrier in vivo.

Discussion

Drawing inspiration from nature, we have harnessed the micellar assemblies of an amphiphilic azocalix[4]arene to achieve remarkable recognition affinities approaching 1012 M−1 toward several bioactive substrates, comparable to the well-known (strept)avidin/biotin pair. The extraordinary binding strength exhibited by this azocalix[4]arene receptor imparts exceptional stability upon the recognition complexes, even within intricate biological environments. Hence, together with the hypoxia-cleavable nature of the azo-bonds, the precise loading and release of bioactive agents into hypoxia-related lesion sites become a real possibility. Our research findings offer an innovative path toward amplifying the recognition capabilities of artificial receptors, transcending the constraints of traditional covalent synthesis and modification. Given the vast number of macrocyclic motifs that have been developed, along with the significant potential for (ultra-)high-affinity receptors in biomedical applications, the biomimetic AER strategy could promote the development and application of artificial (ultra-)high-affinity receptors.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

All chemicals were used as received without further purification. Fluorescein (Fl) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. TCPPZn was bought from Frontier Scientific. TCPP and TCPPFe were bought from Aladdin Scientific. TPPS was bought from TCI Chemicals. Boron cluster (Na2B12H12) was purchased from Katchem. The azocalix[4]arene QAAC4A12C (38) and QAAC4A (47) were synthesized according to literature procedures.

Instruments.

UV-Vis spectra were recorded on a Cary 100 spectrophotometer. Steady-state fluorescence measurements were recorded on a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrometer. Fluorescence lifetimes were measured on a FS5 spectrofluorometer. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AV400 spectrometer. MS spectrum was collected on a Varian 7.0 T FTMS (QFT-ESI). DLS measurements were carried out on a laser light scattering spectrometer (NanoBrook 173plus and Brookhaven ZetaPals/BI-200SM). TEM images were taken on a Talos F200X TEM. AFM Data were collected on Bruker Dimension ICON AFM. Ex vivo organ imaging was carried on an IVIS Lumina II imaging system. Isothermal titration calorimeter measurements were recorded on Malvern MicroCal PEAQ-ITC. SAXS measurement was carried on Anton paar Saxsess MC2.

Binding Constant Measurements.

Fluorescence titration and/or UV-Vis titration are employed to measure the binding affinities of the azocalixarenes. All data were processed using Origin software. For direct host–guest titrations, the concentrated solution of a host (azocalixarene) is titrated into the solution of a guest (usually a dye). The equation of complexation between the host and the guest is expressed according to a 1:1 binding stoichiometry.

where Ka is the binding constant between the host and the guest, [H] is the concentration of the free host, [G] is the concentration of the free guest, and [HG] is the concentration of the host–guest complex. Total absorbance or fluorescence (I) is the linear combination of the free guest (IG) and the host–guest complex (IHG). [H]0 is the total concentration of the free and complexed host ([H]0 = [H]+ [HG]), and [G]0 is the total concentration of the free and complexed guest ([G]0 = [G]+ [HG]).

For competitive titrations, the concentrated solution of a host is titrated into the solution which contains both a guest and a competitor. Alternatively, the competitor can also be titrated into the mixed solution of the guest and the host solution. The guest is used as the indicator in the competitive titration. The intensity (I) of the absorbance or fluorescence (I) upon titrations are recorded at prescribed wavelengths. There is another equilibrium existing between host and competitor. We define [C] as concentration of free competitor, [HC] as concentration of host-competitor complex, and [C]0 as total concentration of competitor ([C]0 = [C]+ [HC]). The signal from competitor should be negligible in measurement. The equation is expressed.

The measured intensity (I) is still the linear combination of free guest (IG) and host–guest complex (IHG).

(Apparent) Ka values were measured by ultrafiltration in DMEM. QAAC4A12C and dye (50 μM/50 μM) solution was centrifuged (5,000 rpm, 10 min) in ultrafiltration tube (10 kDa). The free dye was collected in filtrate and quantified by UV-Vis absorbance.

Enthalpy Change Measurement.

To avoid the complex interaction process associated with assembly and precipitation resulting from electrical neutralization, we selectively measured the enthalpy change using low equivalents of the guest via ITC titration. The calixarenes solution (50 μM, 200 μL) was prepared in the cell, and guest solution (200 μM) was loaded in the injector. Then, 2 μL of guest solution was titrated into the cell at 25 °C with total of 11 injections (0.4 μL for the first injection). The enthalpy change of last 10 injections was calculated from three groups of parallel experiments based on complexation ratio calculated from binding constants. The dilution heat of these guests can be neglected according to the measurement.

Preparation and Characterization of the QAAC4A12C Assembly.

QAAC4A12C, QAAC4A were synthesized according to previous reports. To characterize the morphology and size of QAAC4A12C assembly, QAAC4A12C was dissolved in H2O under sonication (80 °C, 2 h). After stabilization at room temperature, the solution was passed over a syringe filter (hydrophilic PTFE, 0.22 μm). The solution was diluted and used for the TEM, AFM, and DLS measurements. The represented structure was analyzed by MD simulations. Detailed molecular simulation methods can be found in SI Appendix, Molecular Simulations.

Hypoxia-Responsive Experiments.

SDT was used as the azo reductase mimic in order to test the hypoxia-responsive property of QAAC4A12C. QAAC4A12C was dissolved in PBS buffer, UV-Vis spectra were recorded before or after the addition of SDT to the solution. For microsome reduction, calixarenes were dissolved in PBS buffer with microsome (80 μg/mL) with NADPH (100 μM) in cuvettes, N2 was continuously purged into the solution to maintain the hypoxic environment. The UV-Vis spectra were recorded at different times to track the reducing process.

In Vitro Cell Uptake Studies.

After the 4T1 cells were seeded in 12-well plate, dyes (Fl or TPPS) or a complex of dyes and QAAC4A12C (10/10 μM) were added and cultured under normoxic conditions for 4 h to facilitate cell uptake. Then, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium, and the cells were subsequently incubated at 37 °C under hypoxic conditions for 18 h. The medium was washed off with PBS, and the cells were digested with trypsin and resuspended. The fluorescence signal intensity of the cells was measured using a flow cytometer, and the data were processed using FlowJo software.

In Vivo Fluorescence Imaging and PDT Studies.

Female BALB/c mice were bought from Yishengyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. For in vivo application, QAAC4A12C was coassembled with 4-(dodecyloxy)benzamido-terminated methoxy poly(ethylene glycol) to enhance its biocompatibility. The 4T1 tumor-bearing mice were administrated intravenously with 200 μL dye (470 μM) or dye/calixarene (470 μM/470 μM) complex solution when tumor volume reached 250 mm3. Mice were dissected after 12, 24, 36, and 48 h. Tumors and major organs were collected and subjected for ex vivo imaging.

In PDT study, 4T1 tumor bearing mice were randomly divided into six groups, that is: “PBS,” “PBS + L” (L means light irradiation), “TPPS,” “TPPS + L,” “TPPS/QAAC4A12C,” and “TPPS/QAAC4A12C + L.” The mice were intravenously administrated with 200 μL PBS, free TPPS (470 μM), or QAAC4A12C/TPPS complex (470 μM/470 μM) solution on day 0 when the tumor volume reached 20 mm3. For group “PBS + L,” “TPPS + L,” and “TPPS/QAAC4A12C + L,” the tumors were irradiated by laser (635 nm, 300 mW cm−2) for 10 min at 24 and 48 h post injection. The volumes of tumor and body weights were measured every other day from day 1 to day 15. Mice were dissected at day 15, tumors and major organs were collected for H&E-stained section and TUNEL section.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. U20A20259, 22371147, and 22271164) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, which are gratefully acknowledged. We thank Prof. Zhao Dong-Bing for the help with fluorescence lifetime measurement. The animal use protocol has been reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethical and Welfare Committee of Institution of Radiation Medicine (Tianjin, China). (Approval number IRM-DWLL-2022219).

Author contributions

D.-S.G. designed research; F.-Y.C., W.-C.G., M.-M.C., R.F., H.H., Z.-Z.Z., W.-B.L., Y.-Q.C., J.-J.L., and K.C. performed research; F.-Y.C. and W.-C.G. analyzed data; and F.-Y.C., J.F.S., and D.-S.G. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Contributor Information

J. Fraser Stoddart, Email: stoddart@hku.hk.

Kang Cai, Email: kangcai@nankai.edu.cn.

Dong-Sheng Guo, Email: dshguo@nankai.edu.cn.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Persch E., et al. , Molecular recognition in chemical and biological systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 54, 3290–3327 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pieters B. J., et al. , Natural supramolecular protein assemblies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 24–39 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tommasone S., et al. , The challenges of glycan recognition with natural and artificial receptors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 5488–5505 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciferri A., Critical issues in molecular recognition: The enzyme-substrate association. Soft Matter 17, 8585–8589 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heinisch T., Ward T. R., Artificial metalloenzymes based on the biotin-streptavidin technology: Challenges and opportunities. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 1711–1721 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan X., et al. , Single particle cryo-em reconstruction of 52 kda streptavidin at 3.2 angstrom resolution. Nat. Commun. 10, 2386 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu W., et al. , Synthetic mimics of biotin/(strept)avidin. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 2391–2403 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qureshi M. H., Wong S. L., Design, production, and characterization of a monomeric streptavidin and its application for affinity purification of biotinylated proteins. Protein Expr. Purif. 25, 409–415 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howarth M., et al. , A monovalent streptavidin with a single femtomolar biotin binding site. Nat. Methods 3, 267–273 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sano T., Cantor C. R., Intersubunit contacts made by tryptophan 120 with biotin are essential for both strong biotin binding and biotin-induced tighter subunit association of streptavidin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 3180–3184 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim K. H., et al. , Engineered streptavidin monomer and dimer with improved stability and function. Biochemistry 50, 8682–8691 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laitinen O. H., et al. , Brave new (strept)avidins in biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 25, 269–277 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller B. S., et al. , Spin-enhanced nanodiamond biosensing for ultrasensitive diagnostics. Nature 587, 588–593 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodrigues M., et al. , Structure-specific amyloid precipitation in biofluids. Nat. Chem. 14, 1045–1053 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houk K. N., et al. , Binding affinities of host-guest, protein-ligand, and protein-transition-state complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 42, 4872–4897 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escobar L., Ballester P., Molecular recognition in water using macrocyclic synthetic receptors. Chem. Rev. 121, 2445–2514 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shetty D., et al. , Can we beat the biotin-avidin pair?: Cucurbit[7]uril-based ultrahigh affinity host-guest complexes and their applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 8747–8761 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao L., et al. , Cucurbit[7]uril⋅guest pair with an attomolar dissociation constant. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 988–993 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xue W., et al. , Pillar[n]maxq: A new high affinity host family for sequestration in water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59, 13313–13319 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu W., et al. , Guest back-folding: A molecular design strategy that produces a deep-red fluorescent host/guest pair with picomolar affinity in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 3361–3370 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou H., et al. , Biomimetic recognition of quinones in water by an endo-functionalized cavity with anthracene sidewalls. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 60, 25981–25987 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu W., et al. , Xcage: A tricyclic octacationic receptor for perylene diimide with picomolar affinity in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 3165–3173 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Escobar L., Ballester P., Quantification of the hydrophobic effect using water-soluble super aryl-extended calix[4]pyrroles. Org. Chem. Front. 6, 1738–1748 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y., et al. , Chloride capture using a c-h hydrogen-bonding cage. Science 365, 159–161 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu G., Chen X., Host-guest chemistry in supramolecular theranostics. Theranostics 9, 3041–3074 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beatty M. A., Hof F., Host-guest binding in water, salty water, and biofluids: General lessons for synthetic, bio-targeted molecular recognition. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 4812–4832 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee D. W., et al. , Supramolecular fishing for plasma membrane proteins using an ultrastable synthetic host-guest binding pair. Nat. Chem. 3, 154–159 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brockett A. T., et al. , Pillar[6]maxq: A potent supramolecular host for in vivo sequestration of methamphetamine and fentanyl. Chem 9, 881–900 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schreiber C. L., Smith B. D., Molecular conjugation using non-covalent click chemistry. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 393–400 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webber M. J., et al. , Supramolecular biomaterials. Nat. Mater. 15, 13–26 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geng W. C., et al. , Supramolecular prodrugs based on host-guest interactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 2303–2315 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parks F. C., et al. , Revealing the hidden costs of organization in host-guest chemistry using chloride-binding foldamers and their solvent dependence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 1274–1287 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chodera J. D., Mobley D. L., Entropy-enthalpy compensation: Role and ramifications in biomolecular ligand recognition and design. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 42, 121–142 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inoue Y., Hakushi T., Enthalpy–entropy compensation in complexation of cations with crown ethers and related ligands. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, 935–946 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim N. H., et al. , Supramolecular assembly of protein building blocks: From folding to function. Nano Convergence 9, 4 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geng W. C., et al. , A noncovalent fluorescence turn-on strategy for hypoxia imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 58, 2377–2381 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu X.-Y., et al. , Hypoxia-responsive host–guest drug delivery system. Acc. Mater. Res. 4, 925–938 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Z., et al. , Macrocyclic-amphiphile-based self-assembled nanoparticles for ratiometric delivery of therapeutic combinations to tumors. Adv. Mater. 33, 2007719 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amaral M., et al. , Protein conformational flexibility modulates kinetics and thermodynamics of drug binding. Nat. Commun. 8, 2276 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yue Y.-X., et al. , Azocalixarenes: A scaffold of universal excipients with high efficiency. Sci. China: Chem. 67, 1697–1706 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biedermann F., et al. , The hydrophobic effect revisited–studies with supramolecular complexes imply high-energy water as a noncovalent driving force. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 11158–11171 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen F. Y., et al. , Expanding the hydrophobic cavity surface of azocalix[4]arene to enable biotin/avidin affinity with controlled release. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 63, e202402139 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inoue Y., Wada T., “Molecular recognition in chemistry and biology as viewed from enthalpy-entropy compensation effect” in Advances in Supramolecular Chemistry, Gokel G. W., Ed. (JAI Press, 1997), pp. 55–96. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zou L., et al. , Single-molecule nanoscale drug carriers with quantitative supramolecular loading. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 5, 197–204 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu J.-J., et al. , Casting: A potent supramolecular strategy to cytosolically deliver sting agonist for cancer immunotherapy and sars-cov-2 vaccination. CCS Chem. 5, 885–901 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yue Y.-X., et al. , Promoting tumor accumulation of anticancer drugs by hierarchical carrying of exogenous and endogenous vehicles. Small Struct. 3, 2200067 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Z., et al. , Design of calixarene-based icd inducer for efficient cancer immunotherapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2213967 (2023). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.