Abstract

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a common neurodevelopmental disorder in children, is associated with alterations in gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which are metabolites influencing the gut-brain axis. Evidence suggests that psychostimulant medications, widely used to manage ADHD symptoms, may also impact gut microbiota composition and SCFA levels. This study explores these potential effects by examining gut microbiota profiles and SCFA concentrations in unmedicated and medicated children with ADHD, compared to healthy controls. Fecal samples from 30 children aged 6–12 years (10 unmedicated ADHD, 10 medicated ADHD, and 10 healthy controls) were analyzed using 16 S rRNA sequencing and targeted metabolomics. Unmedicated ADHD children show distinct gut microbiota profiles, with lower level of Tyzzerella, Prevotellaceae, and Coriobacteriaceae, compared to controls. Notably, propionic acid levels were negatively associated with ADHD symptom severity, suggesting a potential biomarker role. Medicated ADHD children showed lower gut microbial diversity, unique taxa, and lower SCFA levels, compared to unmedicated children with ADHD. These findings suggest that gut microbiota and SCFAs may be linked to ADHD symptomatology, underscoring the importance of gut-brain interactions in ADHD. This study highlights the potential of gut health monitoring as part of future ADHD management strategies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-87546-y.

Keywords: ADHD, Gut microbiota, SCFAs, Psychostimulants, Children, Biomarkers

Subject terms: Neurological disorders, Microbiology, Paediatric research, Metabolomics

Introduction

The gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication network linking the central nervous system (CNS) and the enteric nervous system, plays a critical role in maintaining physiological homeostasis and influencing neurodevelopment and behavior1–3. This axis facilitates communication through neural, immune, and endocrine pathways, with the gut microbiota—a diverse community of microorganisms residing in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract—playing a pivotal role2,4. Gut microbiota influence the brain by producing bioactive compounds, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and neurotransmitter precursors, as well as modulating immune responses and maintaining the integrity of the blood-brain barrier5. Dysbiosis, or imbalances in the gut microbiota, has been implicated in neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders, including autism spectrum disorder, anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)6–8.

ADHD is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders, affecting approximately 3.4–7.6% of children globally9–12. In Thailand, ADHD prevalence among primary school-aged children is reported to be 6.5%, with boys (9.1%) more affected than girls (3.6%)13. Characterized by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, ADHD significantly impairs academic performance, social interactions, and overall quality of life, often persisting into adulthood14. While genetic, environmental, and neurobiological factors contribute to ADHD, its molecular mechanisms remain unclear, posing challenges for accurate diagnosis and effective management15.

Emerging evidence suggests that the gut-brain axis may influence ADHD symptoms. Specific gut microbial profiles have been associated with ADHD, indicating that microbiota may contribute to symptoms through pathways involving neurotransmitter synthesis, neuroinflammation, and immune modulation8,16–18. Among these mechanisms, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid, are of particular interest2. These metabolites are produced by gut microbiota through the anaerobic breakdown of dietary fibers19. These metabolites play a vital role in regulating immune responses, maintaining gut health, and facilitating gut-brain communication20,21. Animal studies have demonstrated that SCFAs can modulate neurodevelopment and behavior, with elevated propionic acid levels linked to hyperactivity and repetitive behaviors in neurodevelopmental disorder models22. However, the role of SCFAs in human ADHD remains largely unexplored, representing a critical gap in understanding the gut-brain interactions that may underlie ADHD pathology.

Psychostimulant medications, such as methylphenidate, are the primary treatment for ADHD, effectively targeting neurotransmitter pathways to alleviate core symptoms23. Recent evidence suggests that psychostimulants may also influence gut microbiota composition and SCFAs production24. Studies on psychotropic medications have shown their capacity to alter microbial diversity and abundance, potentially impacting gut-brain communication pathways and neurodevelopment7,25. Additionally, the bioavailability and stability of methylphenidate may be influenced by the gut microbiota indirectly through pH modulation. Research indicates that variations in intestinal pH, potentially driven by microbial activity, can affect the hydrolysis of methylphenidate, emphasizing the interplay between gut conditions and psychostimulant pharmacokinetics24. These findings underscore the potential bidirectional relationship, where psychostimulants may modulate gut microbiota composition, and microbial-derived changes in the gut environment could, in turn, influence drug stability and absorption. Despite these insights, the influence of psychostimulants on the gut-brain axis in children with ADHD remains poorly understood. Most existing studies focus on treatment-naïve individuals, leaving significant gaps in understanding how psychostimulants modulate gut microbial diversity and metabolic profiles26–30.

This study aims to address these gaps by examining gut microbiota composition and SCFA concentrations in children with ADHD, comparing unmedicated and medicated groups to healthy controls. By focusing on children aged 6–12 years—a developmental period marked by significant changes in gut and brain function31—this study explores the potential effects of psychostimulants on gut microbial diversity and metabolic profiles during this key stage of development. Although prior research has explored gut microbiota in treatment-naïve ADHD children, no studies have specifically assessed the impact of psychostimulant medications on gut microbiota and SCFA production in this age group27–29,32,33.

We hypothesize that psychostimulant-treated children will exhibit distinct alterations in their gut microbiota and SCFA profiles compared to unmedicated ADHD children and healthy controls. By investigating these differences, we aim to improve understanding of how psychostimulant medication may influence the gut-brain axis, potentially identifying microbial and metabolic biomarkers that could inform future ADHD management strategies.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

The study included 30 participants divided equally into three groups: unmedicated ADHD (n = 10), medicated ADHD (n = 10), and healthy controls (n = 10). Demographic and clinical characteristics, including age, gender, BMI, gestational age, birth delivery mode, breastfeeding and dietary intake, did not differ significantly among the groups (detailed statistics in Supplementary Table S1).

Gut microbial diversity and composition

Alpha diversity

Alpha diversity, assessed using Observed Feature, Pielou’s Evenness, Shannon, and Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity (Faith’s PD) index, revealed differences between groups. Faith’s PD was significantly higher in unmedicated ADHD children compared to healthy controls. Medicated ADHD children showed significantly lower in Pielou’s evenness, Shannon index and Faith’s PD compared to the unmedicated ADHD children, indicating a lower microbial diversity with psychostimulant treatment (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Alterations in gut microbiota diversity and composition among healthy controls, children with unmedicated ADHD and children with medicated ADHD. (A) Alpha diversity measured using Observed Feature, Pielou’s Evenness, Shannon, and Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity index. (B) Beta diversity analysis using Bray-Curtis, Jaccard, Unweighted UniFrac, Weighted UniFrac metrics. (C) Relative abundance of specific taxa across the three groups. * p < 0.05 for unmedicated ADHD vs. healthy controls; # p < 0.05 for medicated ADHD vs. unmedicated ADHD.

Beta diversity

Beta diversity analysis using PCoA revealed distinct clustering of the three groups based on Jaccard and UniFrac distances, indicating differences in overall microbial community structure (PERMANOVA p = 0.001). Pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences in both weighted and unweighted UniFrac distances between unmedicated ADHD children and control group, and between medicated and unmedicated ADHD children (Fig. 1B).

Differential abundance analysis

The relative abundance of specific taxa across the three groups was shown in Fig. 1C. ANCOM-BC analysis (Fig. 2) revealed significantly lower levels of several phyla in the unmedicated ADHD group compared to healthy controls, including Verrucomicrobiota, Desulfobacterota, Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteriota.

Fig. 2.

Differential abundance of gut microbiota among healthy controls, children with unmedicated ADHD and children with medicated ADHD. Significant taxa with differential abundance were identified using ANCOM-BC at the phylum, class, order, family, and genus levels. Each panel displays comparisons between (1) unmedicated ADHD and healthy controls, (2) medicated ADHD and unmedicated ADHD, and (3) medicated ADHD and healthy controls. Positive fold changes indicate taxa enriched in the first group of the comparison, while negative fold changes indicate enrichment in the second group. Error bars represent confidence intervals. p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons using FDR.

At the genus level, unmedicated ADHD children displayed significantly lower levels of Tyzzerella, Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group, Blautia and Anaerostipes compared to healthy controls.

In the medicated ADHD group, nine genera, including Ruminococcaceae, Haemophilus, Enhydrobacter, Kytococcus, Micrococcus, Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, Brevundimonas, and Odoribacter were significantly lower compared to the unmedicated ADHD group. In contrast, Anaerostipes abundance was higher in the medicated group. Parvimonas abundance was significantly higher in the medicated ADHD group compared to healthy controls (detailed statistics in Supplementary Table S2).

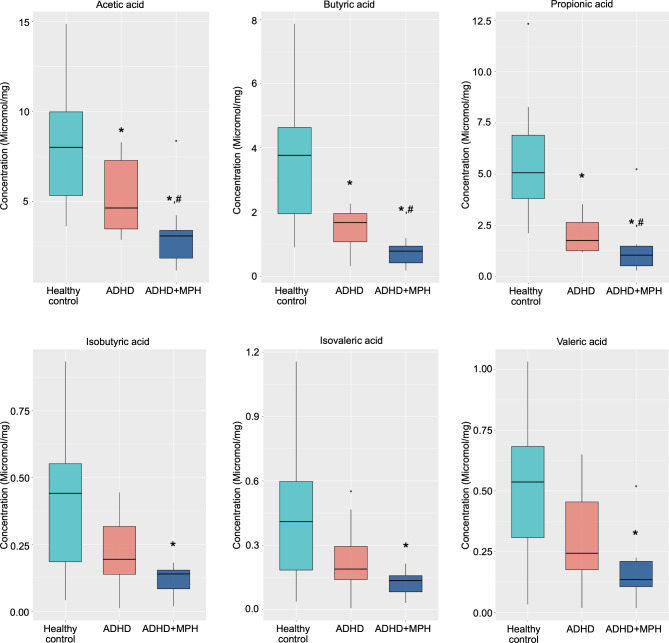

Gut microbial metabolites (SCFAs)

SCFA concentrations were progressively lower in medicated ADHD children compared to both unmedicated ADHD children and healthy controls (Fig. 3). Acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid were significantly lower in the unmedicated ADHD group compared to healthy controls. Medicated ADHD children exhibited significantly lower levels of these SCFAs compared to unmedicated ADHD children.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of fecal short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) concentrations among healthy controls, children with unmedicated ADHD and children with medicated ADHD. Box plots illustrate the concentrations of six SCFAs: acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, valeric acid, isobutyric acid, and isovaleric acid across the three groups. * p < 0.05 for unmedicated ADHD vs. healthy controls; # p < 0.05 for medicated ADHD vs. unmedicated ADHD.

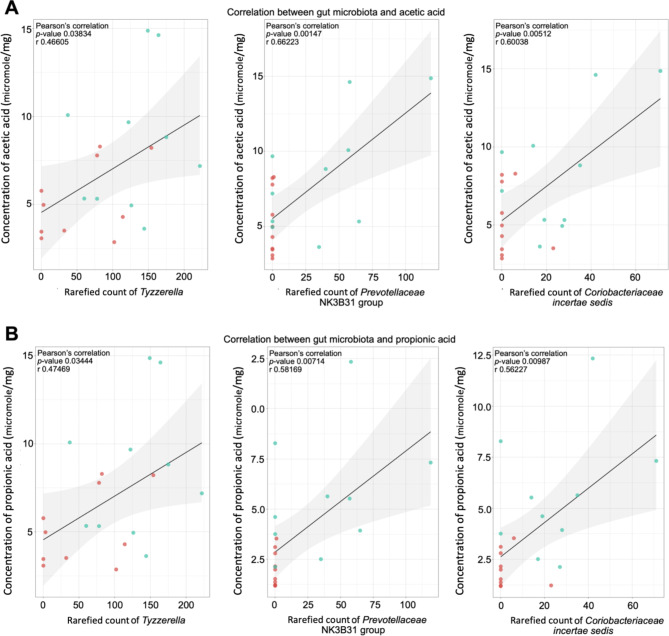

Correlation between gut microbial abundance and SCFAs

Correlation analyses revealed significant associations between certain SCFAs and ADHD symptom scores (Fig. 4). Propionic acid showed the strongest negative correlations with inattention, hyperactivity, and combined symptom scores. Acetic acid levels were also inversely correlated with all symptom domains. Butyric acid displayed significant correlations only with inattention scores. The effect sizes for these correlations were moderate, indicating a meaningful association between SCFA concentrations and ADHD symptoms.

Fig. 4.

Spearman correlation analysis between fecal SCFA concentrations and ADHD symptom scores. Correlation coefficients are presented for acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, isobutyric acid, isovaleric acid, and valeric acid against inattention, hyperactive, and combined ADHD symptom scores. Significant correlations (p < 0.05) are highlighted with color-coded circles: blue for negative correlations and pink for positive correlations. The size of the circles corresponds to the strength of the correlation, with larger circles indicating stronger associations.

Positive correlations were observed between Tyzzerella, Prevotellaceae NK3 B31 group, and Coriobacteriaceae incertae sedis with propionic and acetic acid levels (Fig. 5). Among unmedicated ADHD children, higher inattention scores were associated with lower levels of Tyzzerella, Treponema, Granulicatella, and Glutamicibacter (Fig. 6). (detailed statistics in Supplementary Table S3)

Fig. 5.

Associations between gut microbiota and fecal SCFA concentrations. Scatter plots illustrate Spearman correlations between Tyzzerella, Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group, and Coriobacteriaceae with fecal levels of (A) Acetic (B) Propionic acid. Each panel displays the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r), p-value, and a linear regression line with a shaded 95% confidence interval to highlight the strength and direction of the associations.

Fig. 6.

Association between gut microbiota and clinical parameters in children with ADHD. Bubble plot depicting associations between the relative abundance of gut microbiota taxa (phylum, class, order, family, and genus levels) and clinical parameters, including ADHD symptom scores (inattention, hyperactivity, combined) and fecal SCFA levels (acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid). The size of each bubble represents the absolute fold change (|FC|), while the color gradient reflects the strength of the association (log10 FDR-adjusted p-value), with blue indicating negative associations and red indicating positive associations.

Functional profiling using PICRUSt2 (Fig. 7) indicates higher activity of SCFA production pathways in the unmedicated ADHD group, especially for key metabolites like propionate and butyrate, in contrast to low fecal SCFA levels. In the medicated ADHD group, lower SCFA production pathways were consistent with the observed lower levels in fecal SCFA levels. (detailed pathway analysis in Supplementary Table S4)

Fig. 7.

Functional potential prediction of gut microbiota using PICRUSt2 reveals differential pathways for SCFA production among healthy controls, children with unmedicated ADHD, and children with medicated ADHD. Heatmap showing predicted metabolic pathways related to short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production based on PICRUSt2 analysis. Rows represent specific metabolic pathways, and columns represent individual participants grouped by health status (healthy controls, unmedicated ADHD, medicated ADHD). The color gradient reflects the relative abundance of pathway activity, with blue indicating lower activity and red indicating higher activity.

Multivariable regression and power analysis

Multivariable regression models confirmed that acetic and propionic acid concentrations were significant predictors of inattention scores (Fig. 8). Post-hoc power analysis for detecting differences in fecal SCFA concentrations showed sufficient power (> 0.80) for propionic (0.948) and butyric acid (0.864), moderate power for Acetic Acid (0.618), and lower power for the remaining SCFAs (0.410–0.548).

Fig. 8.

Multiple regression analysis of fecal SCFA levels and ADHD symptom scores in medicated ADHD children. Note: The asterisk indicates significance < 0.05.

In summary, these findings reveal significant alterations in gut microbial diversity, composition, and metabolic pathways among unmedicated ADHD, medicated ADHD, and healthy controls. Unmedicated ADHD children exhibited higher predicted activity in SCFA production pathways but lower fecal SCFA levels. Medicated ADHD children demonstrated the most pronounced dysbiosis, characterized by lower microbial diversity, SCFA-producing taxa, and metabolic pathways. Furthermore, negative correlations were observed between SCFA levels and ADHD symptom severity, suggesting potential functional links between microbial metabolites and clinical outcomes, underscoring the role of gut microbiota in ADHD pathology.

Discussion

This study highlights significant changes in gut microbiota composition and SCFA profiles in children with ADHD, with distinct differences observed between unmedicated and medicated groups compared to healthy controls. The findings underscore the importance of the gut-brain axis in ADHD pathology and suggest that psychostimulant medications like methylphenidate may further influence gut microbial diversity, composition, and metabolite production.

Gut microbial diversity in ADHD

Children with unmedicated ADHD exhibited distinct gut microbiota profiles compared to healthy controls, with notable differences in alpha and beta diversity metrics. Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity (Faith’s PD) was significantly higher in unmedicated ADHD children, suggesting an increase in phylogenetic diversity. This contrasts with findings from other neurodevelopmental disorders, where reduced microbial diversity is often observed5–7. The increase in Faith’s PD may reflect compensatory microbial adaptations or unique gut-brain interactions specific to the ADHD population. Similar patterns have been reported Jiang et al.27 and Wan et al.30, raising the possibility that increased diversity could either be an adaptive response to ADHD-related physiological changes or contribute directly to ADHD pathology. Further functional studies, including metagenomic and metabolomic analyses, are needed to elucidate the implications of increased microbial diversity in ADHD.

In contrast, in medicated ADHD children, lower levels in alpha diversity metrics, including Pielou’s evenness, Shannon index, and Faith’s PD, were observed. This suggests that psychostimulant treatment may exacerbate pre-existing dysbiosis, potentially affecting neurodevelopment through altered microbial metabolic activity. Reduced microbial diversity is often associated with less resilient gut ecosystems34, which may increase vulnerability to inflammatory or metabolic dysregulation. This highlights the need to explore how long-term psychostimulant use impacts gut health and neurodevelopment.

Taxonomic changes in gut microbiota

Taxonomic shifts in gut microbiota composition were evident across groups. Unmedicated ADHD children showed significant lower levels in SCFA-producing phyla, including Verrucomicrobiota, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidota, consistent with previous studies35,36. Verrucomicrobiota, essential for polysaccharide breakdown and SCFA production, play a critical role in maintaining gut barrier integrity and immune homeostasis37. The reduction in this phylum may compromise metabolic and immune processes, exacerbating ADHD symptoms. Additionally, an increase in pro-inflammatory taxa such as Proteobacteria, particularly Alphaproteobacteria, was observed, potentially reflecting a shift toward a more inflammatory gut environment in ADHD.

Interestingly, no significant differences were detected in Bacteroides or Bifidobacterium levels between unmedicated ADHD and control groups, contrary to previous studies26,28. This discrepancy may reflect age-related differences in microbiota composition, as this study focused on children aged 6–12 years, while prior studies included adolescents. The observed increase in Moraxellaceae families aligns with earlier findings in children with ADHD27. These differences underscore the importance of considering developmental stages in microbiota research.

Lower levels of SCFA-producing genera such as Blautia, Anaerostipes, and Tyzzerella were observed. Tyzzerella, a member of Lachnospiraceae family, has recently attracted interest in microbiome research due to its potential impact on human health38. Tyzzerella positively correlated with propionic acid levels and negatively correlated with inattention symptoms, highlighting its potential role in ADHD pathology. These findings underscore the importance of further functional studies to elucidate the role of specific taxa in gut-brain signaling.

Impact of psychostimulant medication

A key finding of this study is the differential gut microbiota composition between medicated and unmedicated ADHD children. Methylphenidate treatment was associated with significant reductions in microbial diversity and SCFA concentrations, particularly acetic, propionic, and butyric acids.

Lower levels of key SCFA producers, such as Ruminococcaceae, suggest that psychostimulants may contribute to gut dysbiosis by selectively reducing beneficial microbial populations. However, we did not detect a difference in Bacteroides Stercoris CL09T0301 between the two groups33. Limited research in methylphenidate restricted further comparisons. The observed increases in Xanthomonadales and Sphingomonadale orders, as well as the Lachnospiraceae family in medicated group, align with findings from studies on other stimulant medications39, suggesting shared microbial shifts across psychotropic treatments.

The exact mechanism by which methylphenidate influences gut microbiota remains speculative. It is hypothesized that psychostimulant medications may alter gut motility and physiology, resulting in alterations in gut transit time and immune system interactions. Additionally, methylphenidate may influence gut microbiota indirectly by regulating the host’s immune responses or modifying gut-brain signaling pathways23.

Interestingly, increases in Parvimonas abundance in medicated ADHD children compared to controls suggests a shift in microbial composition toward that of healthy individuals. Parvimonas is known to metabolize methylphenidate into its inactive form (ritalinic acid)40,41 highlighting a bidirectional relationship between gut microbiota and psychostimulant metabolism. This interaction underscores the need to explore how gut microbiota influence drug bioavailability, efficacy, and potential side effects, paving the way for personalized ADHD treatment strategies.

SCFA concentrations and their functional implications

SCFA levels, including acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid, were significantly lower in both ADHD groups compared to healthy controls, with the medicated group showing the most pronounced reductions. Among SCFAs, propionic acid demonstrated the strongest negative correlation with ADHD symptom severity, particularly inattention scores, suggesting its potential as a biomarker for ADHD.

While functional pathway analyses revealed higher predicted SCFA production capacity in unmedicated ADHD children, their fecal SCFA levels remained lower than those in healthy controls. This discrepancy may reflect heightened absorption or systemic utilization of SCFAs within the gut. SCFAs, particularly butyrate and propionate, serve as critical energy sources for colonocytes and play key roles in glucose metabolism, lipid synthesis, and immune regulation. Increased SCFA utilization to meet elevated systemic energy demands in unmedicated ADHD children could explain their reduced fecal SCFA levels despite enhanced microbial production. Furthermore, alterations in gut permeability, transporter activity, or epithelial turnover, commonly associated with neurodevelopmental disorders, may contribute to higher SCFA absorption. Reduced plasma SCFA levels, as reported in a recent study42, further support potential disruptions in systemic SCFA distribution or metabolic pathways in ADHD. This hypothesis underscores the need for a holistic approach, integrating fecal and plasma SCFA analyses alongside metabolic pathway evaluations, to fully understand SCFA dynamics and their implications for gut-brain axis dysfunction in ADHD.

In the medicated ADHD group, a lower abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria, such as Ruminococcaceae, likely contribute to the observed SCFA deficiencies. Functional pathway analysis indicates lower predicted SCFA production capacity, aligning with the observed low fecal SCFA levels and suggesting that reduced microbial metabolic activity is the primary driver in this group. These findings highlight the dual impact of psychostimulant use—potential gut dysbiosis and diminished SCFA production—on gut health and its downstream effects on the gut-brain axis.

While animal studies have linked elevated propionic acid levels to hyperactivity and repetitive behaviors22, our findings suggest a negative correlation between propionic acid and ADHD symptom severity in humans. These discrepancies may reflect species-specific differences in microbiota composition, SCFA metabolism, and brain sensitivity.

Propionic acid’s ability to regulate dopamine synthesis by influencing the expression of key enzymes involved in catecholamine biosynthesis, such as tyrosine hydroxylase43,44. Tyrosine hydroxylase converts the amino acid tyrosine into dopamine, potentially influencing dopamine levels in the brain44,45. This modulation is especially relevant as dopamine plays a critical role in attention and impulse control, key factors in ADHD26. Moreover, propionic acid can regulate the production of other neurotransmitters, including serotonin, by regulating the expression of tryptophan hydroxylase, the enzyme responsible for converting tryptophan into serotonin44,45. Additionally, its role in modulating immune responses and inflammation can indirectly affect brain function and neurotransmitter dynamics46–48. The significant SCFA deficiencies in medicated ADHD children raise concerns about the long-term impact of psychostimulants on gut health. Addressing these deficiencies through dietary modifications, prebiotics, or probiotics could mitigate potential negative effects on the gut-brain axis.

Clinical implications

Our findings suggest that fecal propionic acid may serve as a potential biomarker for ADHD, aiding in diagnosis, monitoring disease progression, and evaluating treatment effectiveness. Personalized treatment strategies could benefit from understanding individual gut microbiota profiles and SCFA levels. For instance, targeted probiotic interventions, dietary modifications, or SCFA supplementation could complement standard ADHD treatments, especially in patients with significantly altered gut microbiota. Monitoring gut health in ADHD patients undergoing long-term psychostimulant use may mitigate potential negative effects on the gut-brain axis. These findings also open new avenues for therapeutic interventions, including prebiotic or probiotic strategies designed to enhance SCFA production and support gut-brain communication.

Future directions and limitations

This study is the first to document alterations in fecal SCFA levels among both medicated and unmedicated ADHD children aged 6–12 years, compared to age- and gender-matched controls. While potential confounders such as BMI, gestational age, birth delivery mode, breastfeeding duration, and dietary intake were carefully controlled49–52, several limitations should be considered.

First, the relatively small sample size (n = 10 per group) may limit the generalizability of findings and reduce statistical power, increasing the risk of Type II errors. Larger, more diverse cohorts are needed to validate these results and detect subtle microbial and metabolic differences.

Second, the cross-sectional design precludes establishing causality between gut microbiota, SCFA levels, and ADHD symptoms. Longitudinal studies are necessary to evaluate changes in gut microbiota and SCFA profiles over time, particularly before and after psychostimulant treatment.

Third, while potential confounders were controlled at baseline, these factors were not included as covariates in regression models due to the small sample size. Future studies should incorporate these variables in statistical models to enhance robustness.

Fourth, psychostimulant use, particularly methylphenidate, may suppress appetite, indirectly influencing dietary intake and gut microbiota composition. Future research with mediation analyses could explore these interactions more deeply.

Fifth, the study population was exclusively Thai and recruited from a single tertiary hospital, limiting generalizability to other racial or ethnic groups. Including participants from diverse ethnic backgrounds will be critical to exploring racial and ethnic differences in microbiota-ADHD relationships.

Sixth, advanced bioinformatic analyses, such as multivariate approaches and microbial network analyses, were not performed due to the small sample size. These methods are valuable for exploring complex interactions within the gut microbiome and identifying relationships between microbial taxa, SCFA levels, and ADHD symptoms. Future studies with larger cohorts should incorporate these techniques to provide deeper insights into the gut-brain axis dynamics.

Finally, while this study highlights potential links between gut microbiota, SCFA levels, and ADHD symptoms, causative relationships remain speculative. The reliance on correlation and association analyses underscores the need for future research integrating longitudinal designs, neuroimaging, functional assays, and dietary interventions to validate and expand upon these findings.

Despite these limitations, this study provides critical insights into the gut-brain axis and its potential role in ADHD. These findings pave the way for future research and the development of gut-focused, personalized interventions in ADHD management.

Conclusions

This study represents a significant step in advancing our understanding of the gut-brain axis and its role in ADHD. By documenting alterations in gut microbiota composition and fecal SCFA levels in both medicated and unmedicated ADHD children compared to healthy controls, our findings highlight the intricate interplay between gut health and neurodevelopmental disorders. Specifically, the strong negative correlation between propionic acid levels and ADHD symptom severity underscores the potential of SCFAs as biomarkers for ADHD diagnosis, progression tracking, and treatment evaluation.

These results provide a foundation for integrating gut-focused interventions into ADHD management strategies. Targeted approaches such as dietary modifications, prebiotics, probiotics, or direct SCFA supplementation may offer novel avenues for enhancing treatment efficacy and mitigating the potential side effects of psychostimulant medications.

Future studies should address the limitations of our research, including the small sample size and cross-sectional design, and expand upon these findings through longitudinal studies, diverse cohorts, and advanced bioinformatic analyses. Incorporating neuroimaging, functional assays, and mediation analyses will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the causal pathways linking gut microbiota and ADHD symptoms.

We hope this work inspires further exploration of the gut-brain axis, ultimately leading to more personalized and gut-focused interventions to improve outcomes for children with ADHD.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study investigated gut microbiota composition and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) profiles in children with ADHD. Participants aged 6–12 years were recruited from Chiang Mai University Hospital, a tertiary care center in Thailand, and categorized into three groups: unmedicated ADHD, medicated ADHD (receiving methylphenidate), and healthy controls. ADHD diagnoses were confirmed by developmental and behavioral pediatricians using the criteria in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)14. Age- and gender-matched healthy controls were screened to exclude neurodevelopmental or chronic disorders. (Supplementary Fig. 1.)

Exclusion criteria included children with other neurodevelopmental disorders such as intellectual disability (ID) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD), those with chronic disorders requiring long-term medication, including cancers, autoimmune disorders, metabolic disorders, and chronic neurological disorders. Also, children administered sedatives, antipsychotics, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, oral antibiotics, and prebiotics/probiotics within the last 14 days were excluded.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University (study code: PED-2563-07623). All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians, and child assent was provided before participation.

Measurements

The Thai version of the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham version IV Scale (SNAP-IV) was administered to assess ADHD core symptoms. The questionnaire consists of 18 ADHD symptom items, with nine items each for inattentive symptoms and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms53,54. Parents completed the SNAP-IV and food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) to determine their children’s macronutrient and fiber intake.

Fecal sample collection

Parents collected fecal samples in sterile plastic cups and refrigerated them at 4 °C immediately. Upon reaching at the laboratory within 24 h, samples were treated with RNAlater (Invitrogen, Massachusetts, USA) to preserve microbiome integrity and subsequently stored at -80 °C until DNA extraction.

Gut microbiota analysis

Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA kit (Qiagen, Germany). The 16s rRNA hypervariable regions V3-V4 were then sequenced on the MiSeq Illumina platform, a process facilitated by Novogene Inc., Singapore. Data processing was undertaken with Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology 2 (QIIME2-2022.8)55. The average input sequencing reads of 164,979 (108,235 − 184,719) reads per sample were processed through the QIIME2 pipeline. The pair-ended reads and quality scores data were merged, denoised, and trimmed based on quality scores. The q2-dada2 plugin56 assigned Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs), leading to a feature table detailing the quantity of each ASV in the samples57. The ASVs underwent alignment using the Multiple Sequence Alignment Program (MAFFT) to generate a phylogenetic tree for further analysis58,59.

To ensure comparability across samples, sequencing reads were rarefied to a uniform depth. The rarefaction depth was determined based on rarefaction curves, ensuring that the selected cutoff occurred after all curves reached their plateau. This approach minimized potential biases associated with uneven sequencing depths while maintaining data integrity and consistency. The resulting data are referred to as “rarefied counts” throughout the analysis. Sensitivity analyses confirmed that the chosen depth provided reliable and consistent diversity metrics across the dataset.

Taxonomy assignments for the ASVs employed the q2-feature‐classifier classify‐sklearn naïve Bayes taxonomy classifier, cross-referenced with the SILVA database version 13860. Differences in taxa abundance between groups and associations between taxa and ADHD symptom scores were determined using the ANCOM-BC statistical framework61. For a clearer depiction of microbial diversity in the gut and related compositions, we utilized alpha and beta diversity indices presented in box plots and Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) plots, using visualization tools in R version 4.1.1 and the qiime2R package.

Targeted metabolomics analysis for fecal SCFAs

A 50-milligram fecal sample was mixed with 0.5 mL of methanol and then sonicated for 15 s. After resting on ice for 5 min, it underwent centrifugation at 16,800 rpm, at a temperature of 4 °C for 10 min. The subsequent supernatant was earmarked for Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis. Adhering to a protocol from a previous study62, concentrations of six SCFAs were quantified: acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, isobutyric acid, valeric acid, and isovaleric acid. Concentrations were then normalized based on the dried weight of the fecal sample.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as median (interquartile range) and percentages. Alpha and beta diversity metrics were analyzed to assess gut microbial diversity. Differential abundance testing was conducted using ANCOM-BC, and correlations between bacterial taxa and SCFA concentrations were determined using Spearman’s correlation. False discovery rate (FDR) corrections were applied to account for multiple comparisons.

Mann-Whitney U tests compared relative abundance and SCFA levels between ADHD and control groups, while ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis tests were applied for three-group comparisons. To predict the functional potential of the gut microbiota, Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States 2 (PICRUSt2) was used. Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) identified during taxonomic profiling were input into PICRUSt2 to infer gene families and KEGG Orthology (KO) pathways. Pathway abundances were compared across the three study groups (healthy controls, unmedicated ADHD, and medicated ADHD) using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Multiple testing corrections were applied using the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR method.

Regression models explored associations between SCFA concentrations and ADHD symptom scores. All analyses were conducted in SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY), with significance set at p < 0.05.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all Cardiac Electrophysiology Research and Training Center staff and all the study participants for their cooperation. We would like to acknowledge the Erawan HPC Project organized by the Information Technology Service Center (ITSC), Chiang Mai University, for providing us with the high-performance computing resources necessary for systems biology and bioinformatics, enabling us to perform metagenomic analysis.

Author contributions

N.B.: Contributed to conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis and investigation, writing-original draft preparation, and funding acquisition, O.L. and N.L.: Contributed to methodology, and formal analysis and investigation; C.K .and S.S.: Contributed to formal analysis and investigation; C.T. and W.N.: Contributed to methodology, and formal analysis and investigation, N.C.: Contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis and investigation, writing-review and editing, and funding acquisition; S.C.C.: Contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis; validation, writing-review and editing, funding acquisition, and supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University (Grant number 086/2564 to NB), Thailand Science Research and Innovation-Chiang Mai University (Fundamental Fund 2566 to NB and SCC), the Distinguished Research Professor Grant from the National Research Council of Thailand (N42A660301 to SCC), the Research Grant for New Scholar from the National Research Council of Thailand (RGNS 64 − 059 CT), the Research Chair Grant from the National Research Council of Thailand (N42A670594 to NC), and the Chiang Mai University Center of Excellence Award (to NC).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database, under Accession No: PRJNA1192585.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Appleton, J. The gut-brain Axis: influence of Microbiota on Mood and Mental Health. Integr. Med. (Encinitas). 17, 28–32 (2018). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cryan, J. F. et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol. Rev.99, 1877–2013. 10.1152/physrev.00018.2018 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Socała, K. et al. The role of microbiota-gut-brain axis in neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders. Pharmacol. Res.172, 105840. 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105840 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belzer, C. & de Vos, W. M. Microbes inside—from diversity to function: the case of Akkermansia. ISME J.6, 1449–1458. 10.1038/ismej.2012.6 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mhanna, A. et al. The correlation between gut microbiota and both neurotransmitters and Mental disorders: a narrative review. Medicine10310.1097/md.0000000000037114 (2024). e37114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Srikantha, P. & Mohajeri, M. H. The possible role of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain-Axis in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2010.3390/ijms20092115 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Liu, L. et al. Gut microbiota and its metabolites in depression: from pathogenesis to treatment. EBioMedicine90, 104527. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104527 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang, N., Gao, X., Zhang, Z. & Yang, L. Composition of the gut microbiota in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 838941. 10.3389/fendo.2022.838941 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polanczyk, G. V., Salum, G. A., Sugaya, L. S., Caye, A. & Rohde, L. A. Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 56, 345–365. 10.1111/jcpp.12381 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sayal, K., Prasad, V., Daley, D., Ford, T. & Coghill, D. ADHD in children and young people: prevalence, care pathways, and service provision. Lancet Psychiatry. 5, 175–186. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30167-0 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas, R., Sanders, S., Doust, J., Beller, E. & Glasziou, P. Prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics135, e994–1001. 10.1542/peds.2014-3482 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salari, N. et al. The global prevalence of ADHD in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ital. J. Pediatr.49, 48. 10.1186/s13052-023-01456-1 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arrirak, N., Sombuteyotha, K., Bourneow, C., Namwong, T. & Glangkarn, S. Prevalence of ADHD and factors for parent’s participation in the care of children with ADHD, Yasothon, Thailand. J. Educ. Health Promot. 12, 423. 10.4103/jehp.jehp_475_23 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

- 15.Faraone, S. V. et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 1, 15020. 10.1038/nrdp.2015.20 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boonchooduang, N., Louthrenoo, O., Chattipakorn, N. & Chattipakorn, S. C. Possible links between gut-microbiota and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders in children and adolescents. Eur. J. Nutr.59, 3391–3403. 10.1007/s00394-020-02383-1 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gkougka, D. et al. Gut microbiome and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review. Pediatr. Res.10.1038/s41390-022-02027-6 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang, Q., Yang, Q. & Liu, X. The microbiota-gut-brain axis and neurodevelopmental disorders. Protein Cell.14, 762–775. 10.1093/procel/pwad026 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva, Y. P., Bernardi, A. & Frozza, R. L. The role of short-chain fatty acids from gut microbiota in Gut-Brain communication. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 11, 25. 10.3389/fendo.2020.00025 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalile, B., Van Oudenhove, L., Vervliet, B. & Verbeke, K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.16, 461–478. 10.1038/s41575-019-0157-3 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rooks, M. G. & Garrett, W. S. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol.16, 341–352. 10.1038/nri.2016.42 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foley, K. A., MacFabe, D. F., Kavaliers, M. & Ossenkopp, K. P. Sexually dimorphic effects of prenatal exposure to lipopolysaccharide, and prenatal and postnatal exposure to propionic acid, on acoustic startle response and prepulse inhibition in adolescent rats: relevance to autism spectrum disorders. Behav. Brain Res.278, 244–256. 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.09.032 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shellenberg, T. P., Stoops, W. W., Lile, J. A. & Rush, C. R. An update on the clinical pharmacology of methylphenidate: therapeutic efficacy, abuse potential and future considerations. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol.13, 825–833. 10.1080/17512433.2020.1796636 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aresti-Sanz, J., Schwalbe, M., Pereira, R. R. & Permentier, H. El Aidy, S. Stability of Methylphenidate under various pH conditions in the Presence or absence of gut microbiota. Pharmaceuticals14, 733 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cussotto, S., Clarke, G., Dinan, T. G. & Cryan, J. F. Psychotropics and the Microbiome: a Chamber of secrets. Psychopharmacol. (Berl). 236, 1411–1432. 10.1007/s00213-019-5185-8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aarts, E. et al. Gut microbiome in ADHD and its relation to neural reward anticipation. PLoS One. 12, e0183509. 10.1371/journal.pone.0183509 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang, H. Y. et al. Gut microbiota profiles in treatment-naive children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behav. Brain Res.347, 408–413. 10.1016/j.bbr.2018.03.036 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang, L. J. et al. Gut microbiota and dietary patterns in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 29, 287–297. 10.1007/s00787-019-01352-2 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prehn-Kristensen, A. et al. Reduced microbiome alpha diversity in young patients with ADHD. PLoS One. 13, e0200728. 10.1371/journal.pone.0200728 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wan, L. et al. Case-control study of the effects of Gut Microbiota Composition on Neurotransmitter Metabolic pathways in Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Front. Neurosci.14, 127. 10.3389/fnins.2020.00127 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Derrien, M., Alvarez, A. S. & de Vos, W. M. The gut microbiota in the First Decade of Life. Trends Microbiol.27, 997–1010. 10.1016/j.tim.2019.08.001 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szopinska-Tokov, J. et al. Investigating the gut microbiota composition of individuals with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Association with symptoms. Microorganisms810.3390/microorganisms8030406 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Stiernborg, M. et al. Bacterial gut microbiome differences in adults with ADHD and in children with ADHD on psychostimulant medication. Brain Behav. Immun.110, 310–321. 10.1016/j.bbi.2023.03.012 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delgado-Baquerizo, M. et al. Microbial diversity drives multifunctionality in terrestrial ecosystems. Nat. Commun.7, 10541. 10.1038/ncomms10541 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steckler, R., Magzal, F., Kokot, M., Walkowiak, J. & Tamir, S. Disrupted gut harmony in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: dysbiosis and decreased short-chain fatty acids. Brain Behav. Immun. Health. 40, 100829. 10.1016/j.bbih.2024.100829 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan, C. et al. SCFA producing Bacteria shape the subtype of ADHD in children. (2019). 10.21203/rs.2.16337/v1

- 37.Yang, H. et al. Comparative studies on the intestinal health of wild and cultured ricefield eel (Monopterus albus). Front. Immunol.15, 1411544. 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1411544 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang, H. et al. Potential Association of Gut Microbial Metabolism and Circulating mRNA Based on Multiomics Sequencing Analysis in Fetal Growth Restriction. Mediators Inflamm 9986187 (2024). (2024). 10.1155/2024/9986187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Yang, Y. et al. Altered fecal microbiota composition in individuals who abuse methamphetamine. Sci. Rep.11, 18178. 10.1038/s41598-021-97548-1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Josefsson, M. & Rydberg, I. Determination of methylphenidate and ritalinic acid in blood, plasma and oral fluid from adolescents and adults using protein precipitation and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry–a method applied on clinical and forensic investigations. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal.55, 1050–1059. 10.1016/j.jpba.2011.03.009 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aresti-Sanz, J., Schwalbe, M., Pereira, R. R., Permentier, H. & El Aidy, S. Stability of Methylphenidate under various pH conditions in the Presence or absence of gut microbiota. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 14. 10.3390/ph14080733 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Yang, L. L. et al. Lower plasma concentrations of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in patients with ADHD. J. Psychiatr Res.156, 36–43. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.09.042 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim, Y. K. & Shin, C. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Neuropsychiatric disorders: pathophysiological mechanisms and novel treatments. Curr. Neuropharmacol.16, 559–573. 10.2174/1570159x15666170915141036 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eastwood, J. et al. The effect of probiotic Bacteria on composition and Metabolite Production of Faecal Microbiota using in Vitro batch cultures. Nutrients15, 2563. 10.3390/nu15112563 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ullah, H. et al. The efficacy of S-Adenosyl methionine and probiotic supplementation on Depression: A Synergistic Approach. Nutrients14, 2751. 10.3390/nu14132751 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puddu, A., Sanguineti, R., Montecucco, F. & Viviani, G. L. Evidence for the gut microbiota short-chain fatty acids as key pathophysiological molecules improving diabetes. Mediat. Inflamm.2014, 1–9. 10.1155/2014/162021 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hee, B. & Wells, J. M. Microbial regulation of host physiology by short-chain fatty acids. Trends Microbiol.29, 700–712. 10.1016/j.tim.2021.02.001 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.González-Bosch, C., Boorman, E., Zunszain, P. A. & Mann, G. E. Short-chain fatty acids as modulators of Redox Signaling in Health and Disease. Redox Biol.47, 102165. 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102165 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Makki, K., Deehan, E. C., Walter, J. & Backhed, F. The impact of Dietary Fiber on gut microbiota in Host Health and disease. Cell. Host Microbe. 23, 705–715. 10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.012 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katsirma, Z., Dimidi, E., Rodriguez-Mateos, A. & Whelan, K. Fruits and their impact on the gut microbiota, gut motility and constipation. Food Funct.12, 8850–8866. 10.1039/d1fo01125a (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao, J., Zhang, X., Liu, H., Brown, M. A. & Qiao, S. Dietary protein and gut microbiota composition and function. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci.20, 145–154. 10.2174/1389203719666180514145437 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramne, S. et al. Gut microbiota composition in relation to intake of added sugar, sugar-sweetened beverages and artificially sweetened beverages in the Malmo offspring study. Eur. J. Nutr.60, 2087–2097. 10.1007/s00394-020-02392-0 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bussing, R. et al. Parent and teacher SNAP-IV ratings of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms: psychometric properties and normative ratings from a school district sample. Assessment15, 317–328. 10.1177/1073191107313888 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pityaratstian, N., Booranasuksakul, T., Juengsiragulwit, D. & Benyakorn, S. ADHD Screening properties of the Thai Version of Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham IV Scale (SNAP-IV) and strengths and difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). J. Psychiatr Assoc. Thail.59, 97–110 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol.37, 852–857. 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 13, 581–583. 10.1038/nmeth.3869 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McDonald, D. et al. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J.6, 610–618. 10.1038/ismej.2011.139 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol.30, 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One. 5, e9490. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res.41, D590–596. 10.1093/nar/gks1219 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin, H. & Peddada, S. D. Analysis of compositions of microbiomes with bias correction. Nat. Commun.11, 3514. 10.1038/s41467-020-17041-7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sriwichaiin, S. et al. Deferiprone has less benefits on gut microbiota and metabolites in high iron-diet induced iron overload thalassemic mice than in iron overload wild-type mice: a preclinical study. Life Sci.307, 120871. 10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120871 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database, under Accession No: PRJNA1192585.