Abstract

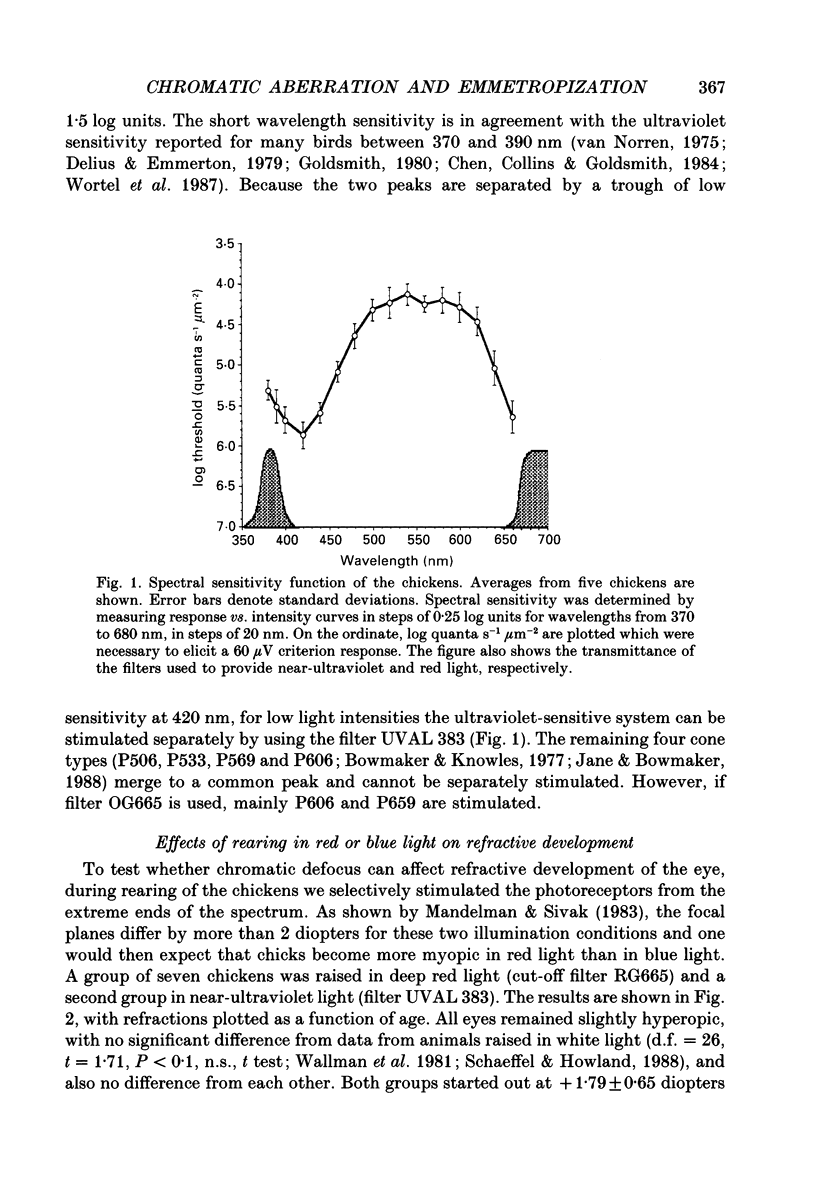

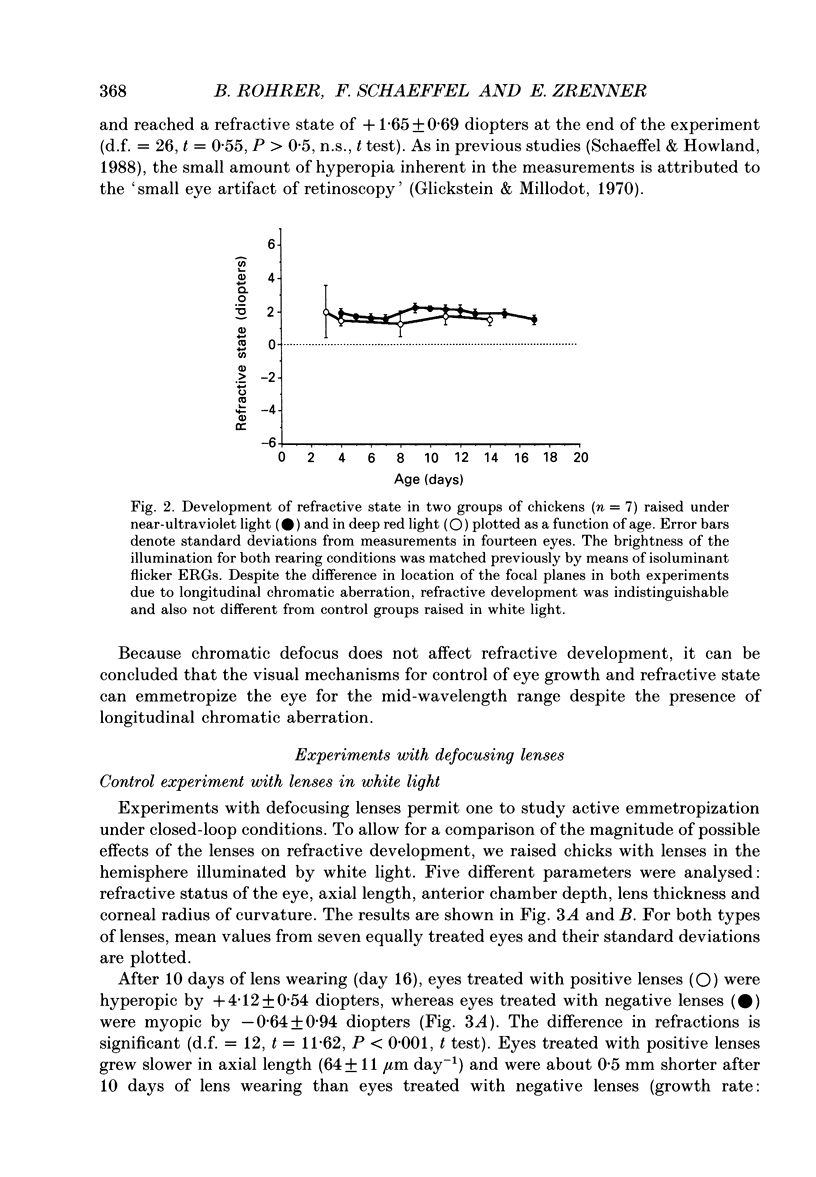

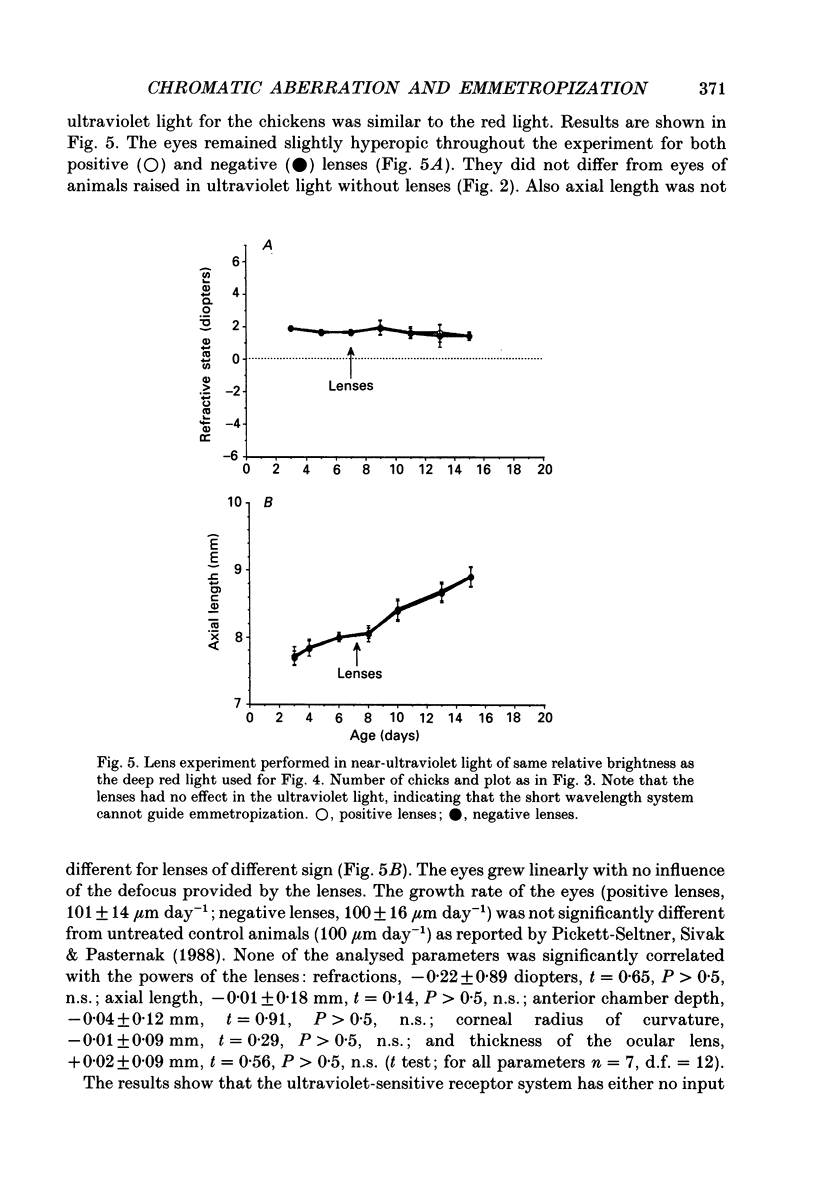

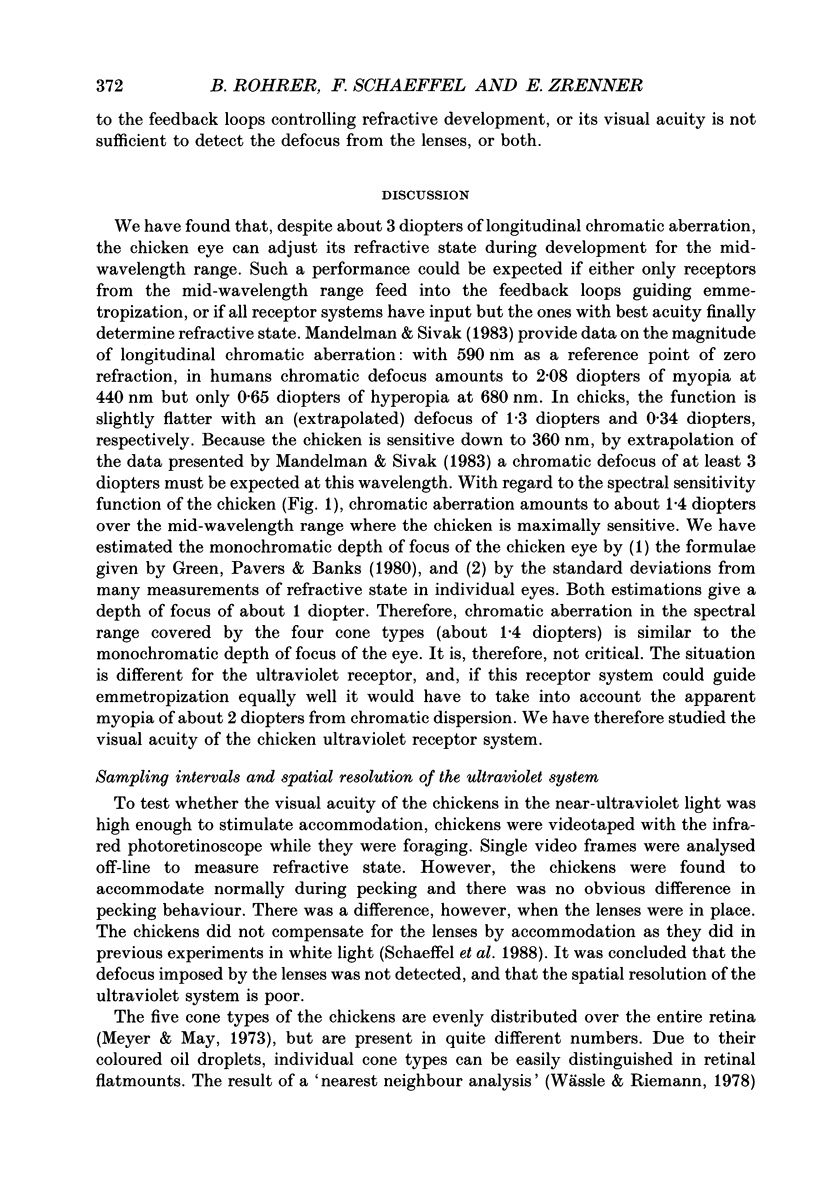

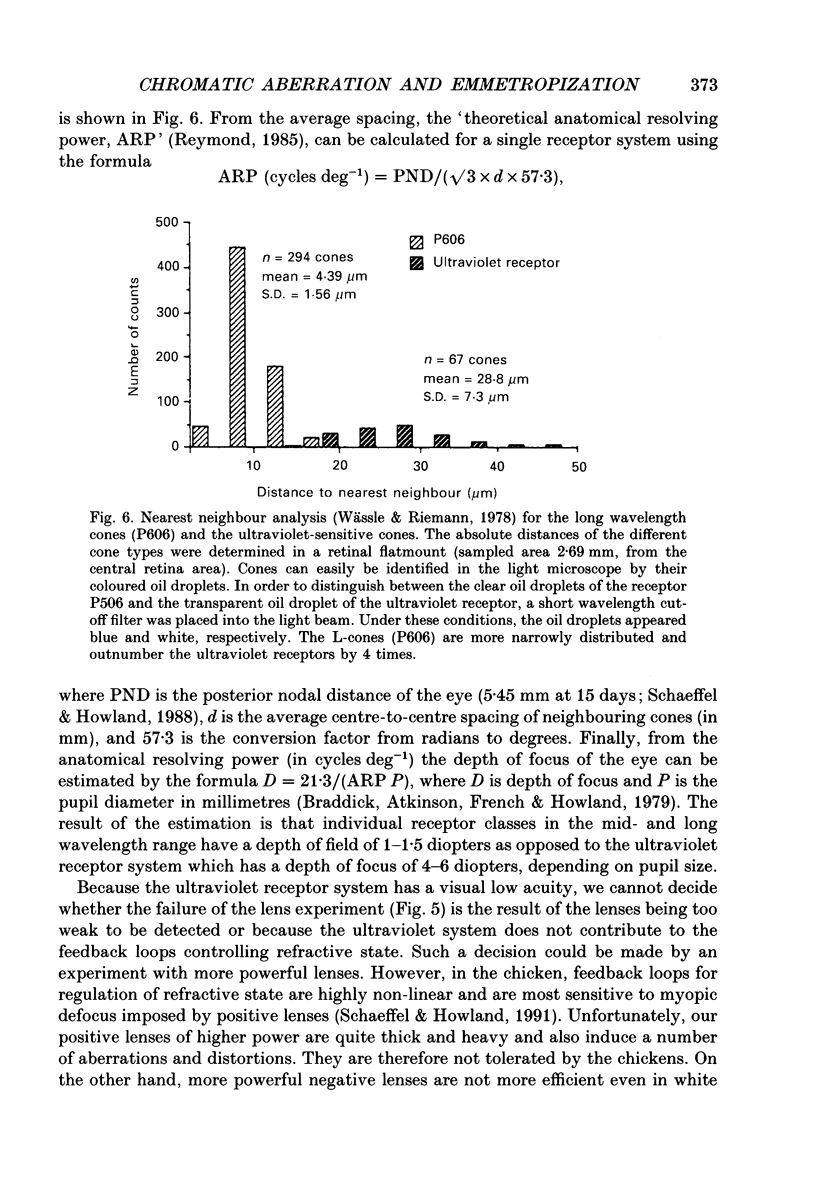

1. Due to the chromatic dispersion of the ocular media, the focal length of the optics of the eye is about 3 diopters longer for red light than for blue light. Because emmetropization in the chicken (Gallus domesticus) does not require colour cues and operates properly in monochromatic light, one can, therefore, expect that chickens raised in red light become more myopic (with longer eyes) than chicks raised in short wavelength light. Prior to conducting this experiment, we matched the brightness of both light conditions by means of flicker electroretinograms such that equiluminance was obtained for the chickens. 2. Unexpectedly, refractive development was not different from controls in white light for either red or near-ultraviolet light. 3. We tested whether the visual mechanisms guiding refractive development were still sensitive to defocus under both illuminations by treating the chicks with spectacle lenses. 4. Similar to a previous experiment in white light, the growth of the eye in red light also changed such that it compensated for the imposed defocus. It failed to do so, however, in near-ultraviolet light. 5. A histological analysis of the sampling intervals for the ultraviolet receptor system revealed that its spatial resolving power was too low to detect the defocus imposed by the lenses, whereas the long wavelength receptors provided sufficiently good visual acuity. 6. The results show that, during emmetropization, the chicken eye elegantly bypasses the problem of multiple chromatic focal planes by having a low sensitivity to defocus in the blue end of the spectrum. Because the chromatic dispersion function is steep in the blue range but flat at the red end of the spectrum, the remaining chromatic defocus in the spectral range of high visual acuity is low and may match the depth of field of the eye.

Full text

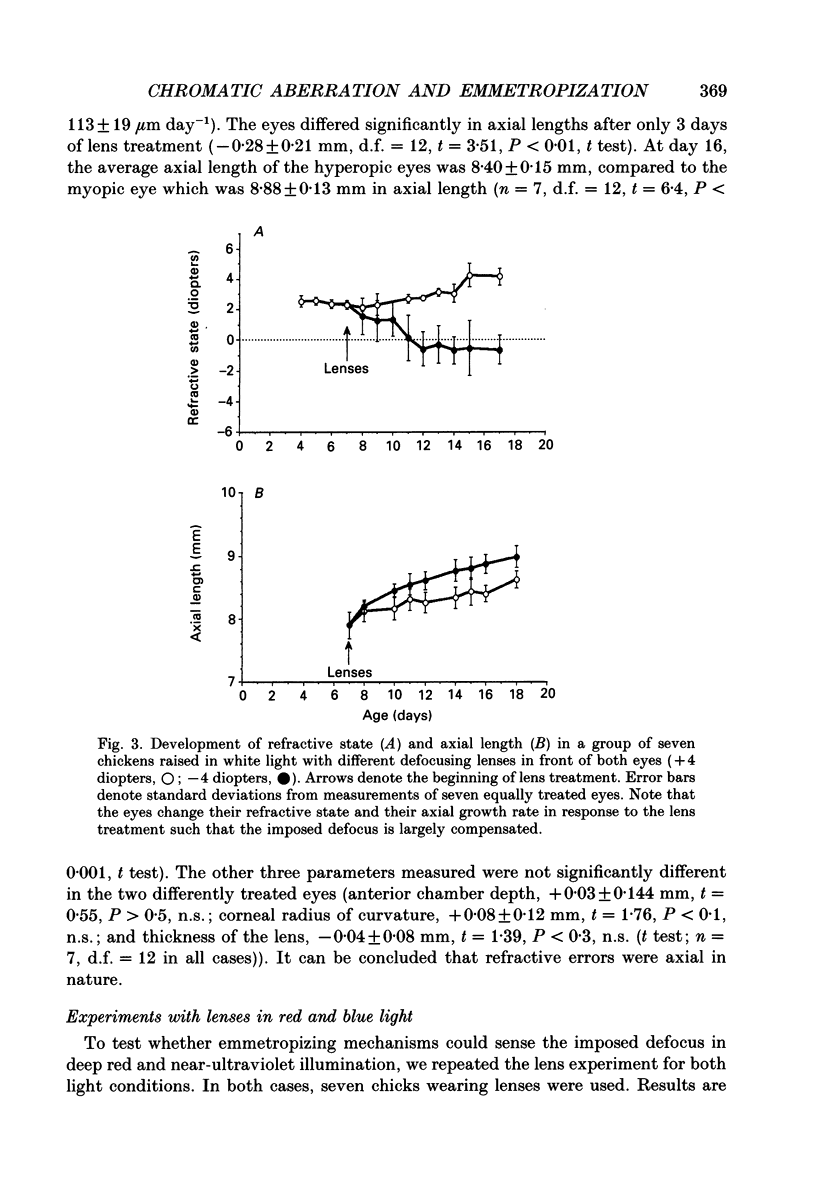

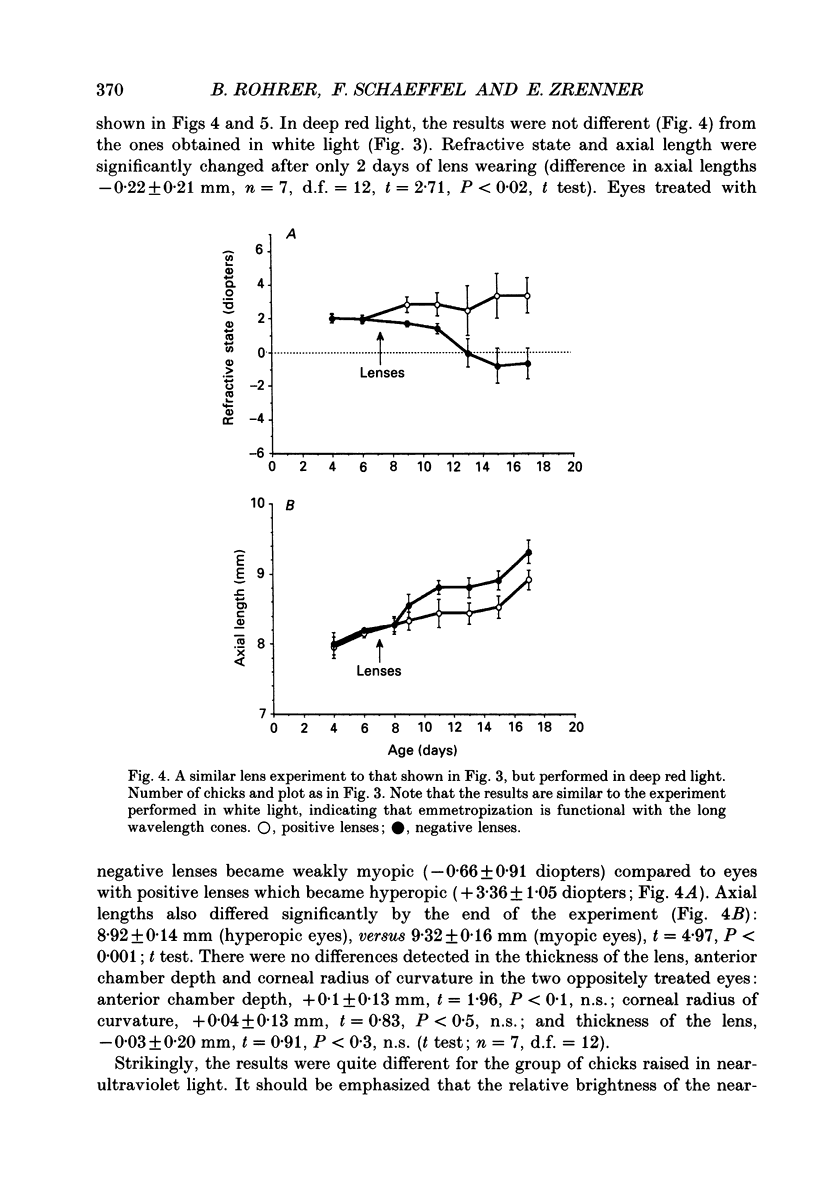

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bowmaker J. K., Knowles A. The visual pigments and oil droplets of the chicken retina. Vision Res. 1977;17(7):755–764. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(77)90117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braddick O., Atkinson J., French J., Howland H. C. A photorefractive study of infant accommodation. Vision Res. 1979;19(12):1319–1330. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(79)90204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D. M., Collins J. S., Goldsmith T. H. The ultraviolet receptor of bird retinas. Science. 1984 Jul 20;225(4659):337–340. doi: 10.1126/science.6740315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FINCHAM E. F. The accommodation reflex and its stimulus. Br J Ophthalmol. 1951 Jul;35(7):381–393. doi: 10.1136/bjo.35.7.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fain G. L., Dowling J. E. Intracellular recordings from single rods and cones in the mudpuppy retina. Science. 1973 Jun 15;180(4091):1178–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.180.4091.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickstein M., Millodot M. Retinoscopy and eye size. Science. 1970 May 1;168(3931):605–606. doi: 10.1126/science.168.3931.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith T. H. Hummingbirds see near ultraviolet light. Science. 1980 Feb 15;207(4432):786–788. doi: 10.1126/science.7352290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb M. D., Fugate-Wentzek L. A., Wallman J. Different visual deprivations produce different ametropias and different eye shapes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987 Aug;28(8):1225–1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govardovskii V. I., Zueva L. V. Visual pigments of chicken and pigeon. Vision Res. 1977;17(4):537–543. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(77)90052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green D. G., Powers M. K., Banks M. S. Depth of focus, eye size and visual acuity. Vision Res. 1980;20(10):827–835. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(80)90063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuvone P. M., Tigges M., Stone R. A., Lambert S., Laties A. M. Effects of apomorphine, a dopamine receptor agonist, on ocular refraction and axial elongation in a primate model of myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991 Apr;32(5):1674–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelman T., Sivak J. G. Longitudinal chromatic aberration of the vertebrate eye. Vision Res. 1983;23(12):1555–1559. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(83)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D. B., May H. C., Jr The topographical distribution of rods and cones in the adult chicken retina. Exp Eye Res. 1973 Nov 25;17(4):347–355. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(73)90244-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norren D. V. Two short wavelength sensitive cone systems in pigeon, chicken and daw. Vision Res. 1975 Oct;15:1164–1166. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(75)90017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew J. D., Wallman J., Wildsoet C. F. Saccadic oscillations facilitate ocular perfusion from the avian pecten. Nature. 1990 Jan 25;343(6256):362–363. doi: 10.1038/343362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett-Seltner R. L., Sivak J. G., Pasternak J. J. Experimentally induced myopia in chicks: morphometric and biochemical analysis during the first 14 days after hatching. Vision Res. 1988;28(2):323–328. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(88)90160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raviola E., Wiesel T. N. An animal model of myopia. N Engl J Med. 1985 Jun 20;312(25):1609–1615. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506203122505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reymond L. Spatial visual acuity of the eagle Aquila audax: a behavioural, optical and anatomical investigation. Vision Res. 1985;25(10):1477–1491. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(85)90226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffel F., Glasser A., Howland H. C. Accommodation, refractive error and eye growth in chickens. Vision Res. 1988;28(5):639–657. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(88)90113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffel F., Howland H. C. Corneal accommodation in chick and pigeon. J Comp Physiol A. 1987 Mar;160(3):375–384. doi: 10.1007/BF00613027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffel F., Howland H. C., Farkas L. Natural accommodation in the growing chicken. Vision Res. 1986;26(12):1977–1993. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(86)90123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffel F., Howland H. C. Properties of the feedback loops controlling eye growth and refractive state in the chicken. Vision Res. 1991;31(4):717–734. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(91)90011-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffel F., Rohrer B., Lemmer T., Zrenner E. Diurnal control of rod function in the chicken. Vis Neurosci. 1991 Jun;6(6):641–653. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800002637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troilo D., Wallman J. Changes in corneal curvature during accommodation in chicks. Vision Res. 1987;27(2):241–247. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(87)90186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troilo D., Wallman J. The regulation of eye growth and refractive state: an experimental study of emmetropization. Vision Res. 1991;31(7-8):1237–1250. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(91)90048-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallman J., Adams J. I. Developmental aspects of experimental myopia in chicks: susceptibility, recovery and relation to emmetropization. Vision Res. 1987;27(7):1139–1163. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(87)90027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallman J., Adams J. I., Trachtman J. N. The eyes of young chickens grow toward emmetropia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981 Apr;20(4):557–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wässle H., Riemann H. J. The mosaic of nerve cells in the mammalian retina. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1978 Mar 22;200(1141):441–461. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1978.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]