Abstract

Background

Digestive system carcinomas (DSC) constitute a significant proportion of solid tumors, with incidence rates rising steadily each year. The systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) has been identified as a potential prognostic marker for survival in various types DSC. This meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the prognostic value of SIRI in patients with DSC.

Methods

We conducted a comprehensive literature search of PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases, searching for studies published from inception to May 30, 2023. Eligible studies included cohort studies that assessed the association between pre-treatment SIRI levels and DSC prognosis. We extracted and synthesized hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using STATA/SE 12.0, stratifying HRs based on univariable and multivariable analysis. Due to substantial heterogeneity, we applied a random-effect model for all pooled analyses. The primary outcome of interest was the overall survival (OS), while secondary outcomes included progression-free survival (PFS), disease-free survival (DFS), time to progression (TTP), and disease specific survival (DSS). Publication bias was evaluated using Begg’s test and Egger’s tests.

Results

A total of 34 cohort studies encompassing 9628 participants were included in this meta-analysis. Notable heterogeneity was observedin the OS (I2 = 76.5%, p < 0.001) and PFS (I2 = 82.8%, p = 0.001) subgroups, whereas no significant heterogeneity was detected in the DFS, TTP, and DSS subgroups. Elevated SIRI was found to be significantly associated with shorter OS (HR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.70–2.30, tau2 = 0.0966) and poorer PFS (HR = 2.36, 95% CI: 1.58–3.53, tau2 = 0.1319), DFS (HR = 1.80, 95% CI: 1.61–2.01, tau2 < 0.0001), TTP (HR = 2.03, 95% CI: 1.47–2.81, tau2 = 0.0232), and DSS (HR = 1.99, 95% CI: 1.46–2.72, tau2 < 0.0001). Furthermore, an increase in SIRI following treatment was linked to reduced OS, TTP, and DFS, while a decrease in SIRI post-treatment corresponded with improved OS, TTP, and DFS compared to baseline levels.

Conclusions

Elevated SIRI is associated with poorer clinical outcomes in patients with DSC. This index may serve as a valuable prognostic biomarker, offering a promising tool for predicting survival in DSC patients.

PROSPERO: registration number

CRD42023430962

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12876-025-03635-2.

Keywords: Gastroenterology, Oncology, Prognosis

Introduction

Digestive system carcinomas (DSCs) encompass a significant portion of solid tumors, primarily including cancers of the esophagus, stomach, colon, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. The incidence of malignant tumors associated with the digestive tract has been increasing, largely due to dietary shifts towards higher consumption of fats and proteins [1, 2]. According to the World Health Organization, in 2020, there were an estimated 5 million new cases of DSC, accounting for 26.5% of all new cancer diagnoses, with over 3.6 million deaths, representing 36.4% of total cancer-related mortality [2, 3]. Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranked third in incidence, followed by gastric (fifth), liver (sixth) and esophageal (seventh) cancers. In terms of mortality, CRC ranked second, with liver (third), gastric (fourth), esophageal (sixth), and pancreatic cancer (seventh) trailing behind [3]. A meta-analysis involving 920 patients from 15 studies reported that DSCs have a worse prognosis compared to non-DSC [4]. Despite substantial dvancements in the diagnosis and treatment of DSC, patients continue to face poor prognoses, often with high risks of recurrence or metastasis [1, 5]. As such, DSC have become a significant medical challenge and economic burden, posing a substantial threat to human health. Identifying reliable biomarkers is thus crucial for assessing prognosis and selecting optimal treatment strategies.

Tumor-related inflammation has been recognized as a hallmark of cancer, playing a crucial role in tumor initiation, progression, and treatment responses [6, 7]. In recent years, various inflammation-based prognostic indicators have been developed, including the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), prognostic nutritional index (PNI), and systemic immune-inflammation index (SII). These indicators have been associated with poor prognosis, and systemic inflammatory markers have demonstrated superior prognostic value over localized immune markers, such as tumor infiltrating lymphocytes [8–11]. In 2016, Qi et al. introduced a novel inflammatory-related marker termed the systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) [12]. This index, calculated using neutrophil and monocyte counts divided by lymphocyte count, provided a non-invasive tool to predict survival in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Their study revealed that patients with a SIRI ≥ 1.8 had significantly shorter overall survival (OS) and time to progression (TTP) compared to those with a SIRI < 1.8. Additionally, an increased SIRI after 8 weeks of treatment was associated with poorer OS and TTP, compared to, patients whose SIRI levels remained stable [12].

Recent studies have demonstrated that SIRI is a more robust prognostic marker compared to other inflammation-based indices in DSC [13–15]. For instance, Li et al. reported that SIRI levels are associated with tumor size, offering valuable insights for the early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer [16]. Multivariable analyses in cohorts with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) undergoing liver transplantation, operable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and gastric cancer (GC) identified SIRI as an independent predictor of prognosis, while NLR, MLR, PLR, PNI and SII did not demonstrate high predictive values [13–15]. Given its efficiency and simplicity, SIRI has increasingly been recognized as an independent prognostic marker for various DSC types in numerous studies [14, 17–19]. Several meta-analyses have confirmed that elevated pretreatment SIRI levels are significantly associated with poorer clinical outcomes in various malignancies [20–22]. However, it is noteworthy that prior studies have not specifically explored whether SIRI offers comparable predictive value for DSC, despite its distinct characteristics and associated risks. Furthermore, the limited number of studies included in these meta-analyses, along with their narrow geographic scope, have hindered a comprehensive assessment of SIRI’s prognostic value in DSC patients.

This meta-analysis aims to address these gaps by systematically reviewing the existing literature on the prognostic value of preoperative SIRI and changes in SIRI levels after systemic treatment compared to baseline in patients with DSC. The goal is to confirm the impact of SIRI on OS in DSC patients and to provide a more robust evaluation of its prognostic utility, thus aiding in clinical decision-making and improving patient outcomes.

Methods

Retrieval strategies

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and the Cochrane Handbook [23]. Additionally, the study adhered to the Reporting Recommendations for Tumor MarkerPrognostic Studies (REMARK) guidelines [24]. The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42023430962).

A comprehensive literature search was performed in PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/; 1996–2023), Web of Science Core Collection (https://clarivate.com/products/web-of-science/; 1970–2023), Embase (Ovid; 1974–2023), and Cochrane Library, to identify studies evaluating the prognostic significance of the SIRI in DSC. The search was restricted to publications in English due to institutional resource limitations in screening non-English literature. The search will start from the establishment of the database and end on May 30, 2023. The following MeSH terms and free-text keywords were used: (“SIRI” OR “systemic inflammation response index”) AND (“neoplasm” OR “tumor” OR “carcinoma” OR “cancer”). The detailed search strategies are provided in the “Supplemental file-search strategy”. Additionally, reference lists of included articles were reviewed to identify further eligible studies. Gray literature was not included, as it is often challenging to retrieve.

All retrieved literature was managed using EndNote software to remove duplicate entries. The search and screening process was independently conducted by two authors (Niu Zuohu and Peng Hongye). In cases of disagreement regarding study inclusion, a third author (Xu Chunjun) was consulted to reach a consensus.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) studies involving human participants with DSC; (2) studies evaluating the prognostic impact of SIRI, including OS, progression-free survival (PFS), disease-free survival (DFS), TTP, or disease specific survival (DSS); (3) original articles.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) articles not retrieved; (2) duplicate publications.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was OS; Secondary outcomes included PFS, DFS, TTP, and DSS. OS was defined as the period from the enrollment to death or last follow-up. PFS was defined as the time from the enrollment to disease progression or death. DFS was defined as the period from enrollment to the disease recurrence or death. TTP was the period from the enrollment to disease progression. DSS was defined as the time from enrollment to death due specifically to the disease. The definitions of the these outcomes were extracted from the included studies.

Data extraction

Data collected for each cohort study included study characteristics (first author’s name, publication year, and country), participant data (tumor type, sample size, patient age, gender, tumor stage, and treatment), SIRI values pre- and post-treatment, and prognosis data (cut-off value, calculation method, outcome indicators, COX regression analysis method, follow-up period). Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the prognostic significance of SIRI were extracted directly from multivariable COX regression analyses. Data extraction was independently conducted by two authors (Niu Zuohu and Zheng Xinzhuo), and the disagreements were resolved by consulting a third author (Xu Chunjun).

Quality assessment

Quality assessment of each study was performed using the Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) criteria [25], which includes six domains: participation, attrition, prognostic factor measurement, outcome measurement, confounding measurement and account, and analysis and reporting). Each domain consists of three to seven subdomains, which were used to assign a low, medium, or high risk of bias score for each main domain. Two authors (Niu Zuohu and Zheng Xinzhuo) conducted the quality assessment, with discrepancies resolved through consultation with a third author (Xu Chunjun).

Statistical analysis

Pooled HRs were calculated using the HRs and 95% CIs extracted from each cohort study. Separate analyses were conducted for cohort studies with univariable and multivariable analysis. Heterogeneity among studies was evaluated using the chi-square test, I2, and tau2. Due to the high heterogeneity typically associated with studies on prognostic factors, a random-effect model was applied to all pooling processes. For datasets with ten or more cohort studies, Begg’s and Egger’s test were used to assess publication bias, and a sensitivity analysis (by sequentially excluding studies) was performed to evaluate the stability of the results. A univariable random-effects meta-regression was conducted to explore potential influencing factors, including country, sample size, SIRI cut-off, treatment, and tumor type. Subgroup analyses were performed to further elucidate the role of SIRI in DSC prognosis and to reduce statistical heterogeneity. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata/SE 12.0 software (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Included studies and characteristics

Following the previously described retrieval strategy, a total of 857 articles were initially identified. After removing duplicates, 599 potentially relevant articles were selected for preliminary screening. Of these, 46 articles remained after excluding non-research articles, non-original articles, articles unrelated to SIRI, studies not focused on human DSC, and those lacking prognostic data, based on title and abstracts review. A detailed full-text review was subsequently conducted according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Ultimately, after excluding studies with duplicate data and those lacking full-text availability, 40 articles were included in our review (Fig. 1). These studies were included in the systematic review section, and after screening, 26 articles were finally included in the meta-analysis section.

Fig. 1.

The flow chart of the literature selection. Abbreviations: SIRI, systemic inflammation response index

A total of 1366 patients from 49 cohorts from 40 studies were included. Notably, seven articles [13, 14, 19, 26–29] contained two cohort studies each, while one article [12] included three cohort studies. The cohort studies covered various cancer types: five focused on esophageal cancer [13, 17, 30, 31]; nine on GC [14, 19, 32–36]; six on CRC [26, 37–40]; thirteen on pancreatic cancer [12, 16, 27, 28, 41–45]; twelve on HCC [15, 29, 46–54]; and one study each on gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (GEJA) [55], combined GEJA and GC [18], cholangiocarcinoma [56], and gallbladder cancer [57] (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the thirty-four cohort studies enrolled in the meta-analysis

| First author, year | Country | Cancer type | Sample size (M/F) | Age distribution (years) | Treatment | Cutoff value | Cutoff selection | Stage | End point | Analytic method | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qi, 2016 (training) | China | PC | 177 (108/69) | 58.8 ± 10.7a | No surgery | 1.8 | ROC analysis | TNM III-IV | OS/TTP | M | NA |

| Qi, 2016 (validation 1) | China | PC | 321 (208/113) | 61.0 ± 10.1a | No surgery | 1.8 | ROC analysis | TNM III-IV | OS/TTP | M | NA |

| Qi, 2016 (validation 2) | China | PC | 76 (46/30) | 60.9 ± 9.6a | No surgery | 1.8 | ROC analysis | TNM III-IV | OS/TTP | M | NA |

| Li, 2017 (training) | China | GC | 455 (321/134) | Mean: 57.6 | With surgery | 0.82 | ROC analysis | TNM I-III | DFS/DSS | M | 77.5 (range 3.0-111.7)b |

| Li, 2017 (validation) | China | GC | 327 (235/92) | Mean: 57.6 | With surgery | 0.82 | ROC analysis | TNM I-III | DFS/DSS | M | 56.3 (range 4.9–76.3)b |

| Xu, 2017 | China | HCC | 351(300/51) | Mean: 53.4 | No surgery | 1.05 | ROC analysis | BCLC B-C | OS | M | NA |

| Geng, 2018 (training) | China | EC | 542 (416/126) | Mean: 54 | With surgery | 1.2 | ROC analysis | TNM I-III | OS | M | NA |

| Geng, 2018 (validation) | China | EC | 374 (280/94) | Mean: 51 | With surgery | 1.2 | ROC analysis | TNM I-III | OS | M | NA |

| Chen, 2019 | China | GEJA | 302 (244/58) | 63 (range 43–84)b | With surgery | 0.68 | ROC analysis | TNM I-III | OS | M | 55 (range 4–98)b |

| Li, 2019 (training) | China | PC | 371 (224/147) | 62 (range 35–84)b | With surgery | 0.69 | ROC analysis | TNM I-III | OS/DFS | M | NA |

| Li, 2019 (validation) | China | PC | 310 (164/146) | 60 (range 34–82)b | With surgery | 0.69 | ROC analysis | TNM I-III | OS/DFS | M | NA |

| Gao, 2020 | China | GC | 240 (163/77) | 60.5 (range 22.0–86.0)b | With surgery | 1.2 | X-tile software | TNM I-III | OS/DFS | U | NA |

| Pacheco-Barcia, 2020 | North America | PC | 164 (92/72) | 66 (57.5–74)c | No surgery | 2.3 | ROC analysis | TNM IV | OS/PFS | M | NA |

| Sun, 2020 | China | GBC | 124 (69/55) |

72: ≤ 65 52: > 65 |

With surgery | 0.89 | ROC analysis | TNM 0-IV | OS | M | 20 (range 0.5–153)b |

| Liu, 2021 (training) | China | GC | 442 (295/147) | 57 (range 23–89)b | With surgery | 0.85 | ROC analysis | TNM I-III | OS | M | 35 (range 4–68)b |

| Liu, 2021 (validation) | China | GC | 152 (115/37) |

97: ≤ 60 55: > 60 |

With surgery | 0.85 | ROC analysis | TNM I-III | OS | M | 35 (range 4–68)b |

| Chen, 2021 | China | GC | 107 (82/25) | 56 (range 32–73)b | With surgery | 1.21 | ROC analysis | TNM II-III | OS/DFS | M | NA |

| Ying, 2021 (training) | China | CRC | 1,014 (622/392) |

554: ≤ 60 460: > 60 |

With surgery | 1.95 | X-tile software | TNM II-III | DFS | M | 36 |

| Ying, 2021 (validation) | China | CRC | 519 (348/171) |

191: ≤ 60 328: > 60 |

With surgery | 1.95 | X-tile software | TNM II-III | DFS | M | 36 |

| Topkan, 2021 | Turkey | PC | 152 (119/33) | 59 (range 27–79)b | No surgery | 1.8 | ROC analysis | TNM III | OS/PFS | M | 18.5 (range 3.2–91.3)b |

| Wu, 2021 | China | HCC | 161 (141/20) | 56.24 ± 11.44a | With surgery | 1.03 | ROC analysis | BCLC 0-C | DFS | M | ≥ 24 |

| Jin, 2021 | China | CC | 232 (136/96) |

155: < 65 77: ≥ 65 |

With surgery | 0.68 | X-tile software | TNM 0-IV | OS | M | 18.5 (1.0-192.0)c |

| Yan, 2022 | China | EC | 192 (111/81) | 73 (range 65–88)b | No surgery | 1.03 | ROC analysis | TNM II-III | OS/PFS | M | 21.3 (range 3.8–95.1)b |

| Xu, 2022 | China | EC | 370 (245/125) | 61 (40–81)c | With surgery | 0.49 | ROC analysis | TNM I-IV | OS | M | NA |

| Wang, 2022 | China | GC/GEJA | 89 (69/20) | 59 (range 32–78)b | With surgery | 0.58 | ROC analysis | TNM IB-IIIC | DFS | U | 29.1 (range 4.1-115.8)b |

| Kamposioras, 2022 (training) | Britain | PC | 138 (87/51) | 62 (range 29–77)b | No surgery | 2.35 | ROC analysis | TNM III-IV | OS | M | 42.7 (range 0.3–64.9)b |

| Kamposioras, 2022 (validation) | Britain | PC | 67 (44/23) | 58 (range 25–74)b | No surgery | 2.35 | ROC analysis | TNM III-IV | OS | M | 42.7 (range 0.3–64.9)b |

| Kim, 2022 | South Korea | PC | 160 (92/68) | 61.8 ± 8.9a | With surgery | 0.87 | Contal/O’Quigely’s method | TNM I-IV | DFS | M | Median: 30 |

| Dâmaso, 2022 | Portugal | PC | 112 (53/59) | 71 (range 34–88)b | No surgery | 1.34 | ROC analysis | TNM III-IV | OS | M | Median: 8.7 |

| Zhao, 2022 | China | HCC | 160 (129/31) | 58 (range 26–86)b | No surgery | 1.64 | ROC analysis | BCLC B-C | OS/PFS | M | NA |

| Xin, 2022 | China | HCC | 403 (328/75) | 58 (range 30–80)b | No surgery | 1.36 | X-tile software | BCLC 0-B | DFS | M | 44.5 (range 12.6–95.0)b |

| Wang, 2023 | China | EC | 508 (340/168) |

283: < 65 225: ≥ 65 |

With surgery | 0.901 | ROC analysis | TNM I-IV | OS | M | > 12 |

| Cao, 2023 | China | CRC | 298 (172/126) | Mean: 56.5 | With surgery | 1.4 | X-tile software | TNM I-IV | OS/DFS | M | NA |

| Cui, 2023 | China | HCC | 218 (197/21) | 53. 9 ± 8.5a | With surgery | 1.25 | ROC analysis | NA | OS/DFS | M | Median: 39.4 |

a Mean ± standard deviation

b Median (range)

c Median ( interquartile range)

NA: Not reported in the initial publication

M, multivariable analysis; U, univariable analysis; CC, cholangiocarcinoma; CRC, colorectal carcinoma; EC, esophageal cancer; GBC, gallbladder cancer; GC, gastric cancer; GEJA, gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; PC, pancreatic cancer; DFS, disease-free survival; DSS, disease-specific survival; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; TTP, time to progression; QUIPS, Quality in Prognosis Studies; ROC, the receiver operating characteristic curve

Table 2.

Main characteristics of the fifteen cohort studies enrolled in the review

| First author, year | Country | Cancer type | Sample size (M/F) | Age distribution (years) | Treatment | Stage | End point | Analytic method | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang, 2020 | China | GC | 231 (156/75) | 62 (range 26–85)b | With surgery | TNM I-III | OS | M | 43 (range 3–73)b |

| Topkan. 2020 | Turkey | PC | 154 (120/34) | 57 (range 29–79)b | No surgery | TNM III | OS/PFS | M | 14.3 (range: 2.9–74.6)b |

| Yeşil, 2020 | Turkey | HCC | 80 (67/13) | 69 (range 29–83)b | Some with surgery | NA | OS/PFS | U | 7.9 (range 1.3–38.8)b |

| Li, 2021 | China | PC | 78 (47/31) | NA | No surgery | TNM I-IV | NA | NA | NA |

| Wang, 2021 | China | HCC | 194 (174/20) | 56.5 ± 12.0a | No surgery | BCLC A-B | OS/PFS | M | NA |

| Cai, 2022 | China | CRC | 646 (403/243) |

267: < 60 379: ≥ 60 |

With surgery | TNM I-IV | DFS | M | Median: 23 |

| Mao, 2022 | China | HCC | 360 (298/62) | 59.2 ± 10.9a | With surgery | NA | OS/DFS | M | 24 (range 1–61)b |

| Zheng, 2022 (training) | China | HCC | 349 (308/41) | 54.5 ± 11.4a | With surgery | BCLC 0-C | DFS | M | 37 (36–43)c |

| Zheng, 2022 (validation) | China | HCC | 234 (209/25) | 49.6 ± 11.1a | With surgery | BCLC 0-B | DFS | NA | 65.6 (63-67.9)c |

| Puhr, 2023 | Austria | GC | 769 (523/246) | 63.9 ± 12.2a | Some with surgery | TNM I-IV | OS | M | NA |

| Yazici, 2023 | Turkey | GC | 199 (130/69) | 64 (range 26–90)b | With surgery | TNM I-IV | OS | NA | 25 (range 1–56)b |

| Cai, 2023 | China | CRC | 217 (124/93) |

123: < 60 94: ≥ 60 |

With surgery | TNM I-III | OS | M | NA |

| Guo, 2023 | China | HCC | 162 (125/37) |

107: ≤ 60 55: > 60 |

With surgery | TNM I-IV | DFS | M | > 24 |

| Cai, 2023 | China | CRC | 210 (118/92) |

89: < 60 121: ≥ 60 |

With surgery | TNM I-III | OS | M | NA |

| Liu, 2023 | China | HCC | 151 (124/27) | 57.4 ± 9.1 | Some with surgery | TNM I-IV | OS/PFS | M | NA |

a Mean ± standard deviation

b Median (range)

c Median ( interquartile range)

NA: Not reported in the initial publication

M, multivariable analysis; U, univariable analysis; CRC, colorectal carcinoma; GC, gastric cancer; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; PC, pancreatic cancer

Geographically, 31 out of 40 articles originated from China, while four were from Turkey [36, 44, 45, 54], and one each from the United Kingdom [27], South Korea [41], Portugal [42], North America [43], and Austria [35]. The sample sizes across studies ranged from 67 to 1014 participants, with the SIRI cut-off values varying betwee 0.49 to 2.35. The included cohort studies utilized OS, DFS, PFS, TTP, and DSS as the outcome measures. Out of these, 26 articles comprising a total of 9,628 participants were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Details of the covariates adjusted for in the HR estimates are provided in Supplementary Table (1) The quality assessment and the risk of bias evaluation for each domain of the included cohort studies are documented in Supplementary Table (2) Additional characteristics of all enrolled cohort studies, such as patient age, gender, tumor staging, treatment modalities, SIRI cut-off selection, and follow-up duration, are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The study designs and primary results of the included studies are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Design and main results of the twenty-six studies enrolled in the meta-analysis

| First author, year | Study design | Main results |

|---|---|---|

| Qi, 2016 | Retrospective study | Higher SIRI had a shorter TTP and OS. |

| Li, 2017 | Retrospective study | Patients who had a higher SIRI had a shorter DFS and DSS. |

| Xu, 2017 | Retrospective study | OS was longer in patients with low SIRI scores. |

| Geng, 2018 | Retrospective study | The patients with a high SIRI and an increase in SIRI > 75% had worse OS, while the patients with a decrease in SIRI > 75% or in the scope of 25% ~75% exhibited better OS. |

| Chen, 2019 | Retrospective study | High SIRI was associated with worse OS. |

| Li, 2019 | Retrospective study | OS and RFS were significantly better in patients with low SIRI. |

| Gao, 2020 | Retrospective study | High preoperative SIRI was significantly associated with worse DFS and OS. |

| Pacheco-Barcia, 2020 | Retrospective study | Patients with low SIRI showed a longer OS and PFS. |

| Sun, 2020 | Retrospective study | The high SIRI group tended to be associated with OS. |

| Liu, 2021 | Retrospective study |

A high SIRI was associated with poor prognosis; patients with a SIRI increase > 50% had a worse OS, while patients. with a SIRI decrease > 50% had a better prognosis. |

| Chen, 2021 | Retrospective study | The DFS and OS in the low SIRI group were longer than the high SIRI group. |

| Ying, 2021 | Retrospective study | High SIRI remained a independent predictor for worse DFS in multivariate analysis. |

| Topkan, 2021 | Retrospective study | High SIRI was associated with poorer OS and PFS. |

| Wu, 2021 | Retrospective study | High SIRI was not associated with DFS. |

| Jin, 2021 | Retrospective study | High SIRI was associated with poorer OS. |

| Yan, 2022 | Retrospective study | Patients in the high-SIRI had poorer OS and PFS. |

| Xu, 2022 | Retrospective study | High SIRI was not associated with OS. |

| Wang, 2022 | Retrospective study | High SIRI was not associated with DFS. |

| Kamposioras, 2022 | Retrospective study | Higher pretreatment SIRI score was associated with poor OS. |

| Kim, 2022 | Retrospective study | Preoperative SIRI value was correlated with DFS, while changes in SIRI values were correlated with OS. |

| Dâmaso, 2022 | Retrospective study | Higher SIRI was associated with significantly lower OS. |

| Zhao, 2022 | Retrospective study | Low SIRI was a independent predictor for better OS and PFS. |

| Xin, 2022 | Retrospective study | OS and DFS were significantly higher in patients with a low SIRI. |

| Wang, 2023 | Retrospective study | High SIRI was not associated with OS. |

| Cao, 2023 | Retrospective study | High SIRI was associated with poorer OS and DFS. |

| Cui, 2023 | Retrospective study | High SIRI was independently associated with low OS and DFS. |

DFS, disease-free survival; DSS, disease-specific survival; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; TTP, time to progression; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index

Table 4.

Design and main results of the fourteen studies enrolled in the review

| First author, year | Study design | Main results |

|---|---|---|

| Zhang, 2020 | Retrospective study | Patients with high FAR-SIRI scores had poorer OS. |

| Topkan. 2020 | Retrospective study | The lower SIRI had significantly superior PFS and OS. |

| Yeşil, 2020 | Retrospective study | Low SIRI value was associated with increased OS, while was not associated with increased PFS. |

| Li, 2021 | Cross-sectional study | Combined detection of CA19-9, NLR and SIRI are of higher value in the early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. |

| Wang, 2021 | Retrospective study | High SIRI was significantly related to poorer tumor response. Low SIRI group had longer PFS and OS. |

| Cai, 2022 | Retrospective study |

Patients with a lower NSAP (established based on SIRI) had significantly associated with better. DFS |

| Mao, 2022 | Retrospective study | SIRI was an independent prognostic factor for 1-year RFS in patients after curative resection. |

| Zheng, 2022 | Retrospective study | Higher SIRI was associated with poorer DFS. |

| Puhr, 2023 | Retrospective study | Higher SIRI scores was associated with shorter OS. |

| Yazici, 2023 | Retrospective study | The higher SIRI was associated with male gender, lower serum albumin level, and Clavien-Dindo Grade III and higher complications. |

| Cai, 2023 | Retrospective study | High preoperative C-SIRI was significantly correlated with poorer OS. |

| Guo, 2023 | Retrospective study | Higher SIRI was a risk factor for early recurrence. |

| Cai, 2023 | Retrospective study | Patients with lower SIRI values had significantly better OS. |

| Liu, 2023 | Retrospective study | High SIRI was not associated with OS and PFS. |

DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index

Relationship between SIRI and OS

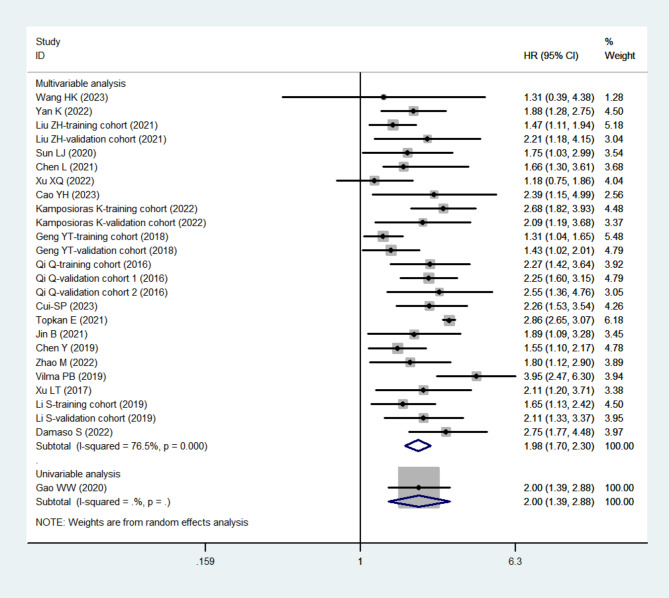

A total of 20 articles, comprising 26 cohort studies with 6,500 participants, examined the relationship between SIRI and OS in patients with DSC. Significant heterogeneity was observed in the pooled adjusted HR (I2 = 76.5%, p < 0.001). Using a random-effects model, we found that higher pre-treatment SIRI levels were significantly associated with shorter OS (HR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.70–2.30, tau2 = 0.0966) (Fig. 2). Patients with elevated SIRI levels had poorer OS compared to those with lower SIRI levels.

Fig. 2.

The forest plot for the association between SIRI and OS in digestive system carcinomas. Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index

To investigate potential sources of heterogeneity, univariable random-effects meta-regression was performed. We identified significant heterogeneity related to country (p = 0.020), sample size (p = 0.001), SIRI cut-off value (p < 0.001), treatment type (p < 0.001), and tumor type (p < 0.001) (Table 5). The cut-off values for subgroup analysis were determined by the median SIRI cut-off across all included studies. Subgroup analyses confirmed that higher SIRI levels were significantly associated with shorter OS across all subgroups of DSC (Supplemental Figs. 1–6). Notably, no significant heterogeneity was observed in any of the subgroups, except for the non-metastatic subgroup (I2 = 86.9%, p < 0.001) (Supplemental Fig. 4).

Table 5.

Stratification analysis of the prognostic value of SIRI on OS in digestive system carcinomas

| Subgroup | Number of studies | Pooled HR (95% CI) | Heterogeneity | Meta-regression (p value) |

tau2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 (%) | p value | |||||

| Country | 0.020 | |||||

| China | 21 | 1.71 (1.56–1.87) | 6.8 | 0.370 | 0.0033 | |

| Britain | 2 | 2.48 (1.80–3.40) | 0.0 | 0.476 | < 0.0001 | |

| Turkey | 1 | 2.86 (2.66–3.08) | - | - | < 0.0001 | |

| North America | 1 | 3.95 (2.47–6.31) | - | - | < 0.0001 | |

| Portugal | 1 | 2.75 (1.73–4.38) | - | - | < 0.0001 | |

| Sample number | 0.001 | |||||

| ≥ 220 | 13 | 1.61 (1.45–1.79) | 18.0 | 0.262 | 0.0085 | |

| < 220 | 13 | 2.72 (2.55–2.90) | 38.4 | 0.077 | 0.0210 | |

| Dividing line for SIRI | < 0.001 | |||||

| ≤ 1.2 | 14 | 1.58 (1.43–1.76) | 0.0 | 0.578 | < 0.0001 | |

| > 1.2 | 12 | 2.75 (2.58–2.93) | 22.0 | 0.227 | 0.0090 | |

| Treatment | < 0.001 | |||||

| With surgery | 15 | 1.60 (1.44–1.77) | 0.0 | 0.479 | < 0.0001 | |

| No surgery | 11 | 2.75 (2.57–2.93) | 29.0 | 0.169 | 0.0122 | |

| Cancer type | < 0.001 | |||||

| Esophageal cancer | 5 | 1.40 (1.20–1.64) | 0.0 | 0.536 | < 0.0001 | |

| Gastric cancer | 4 | 1.70 (1.40–2.06) | 0.0 | 0.481 | < 0.0001 | |

| Gallbladder cancer | 1 | 1.75 (1.03–2.99) | - | - | < 0.0001 | |

| Colorectal carcinoma | 1 | 2.39 (1.15–4.98) | - | - | < 0.0001 | |

| Pancreatic cancer | 10 | 2.75 (2.58–2.94) | 37.4 | 0.109 | 0.0170 | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 3 | 2.06 (1.57–2.71) | 0.0 | 0.779 | < 0.0001 | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 1 | 1.89 (1.09–3.28) | - | - | < 0.0001 | |

| Gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma | 1 | 1.55 (1.10–2.18) | - | - | < 0.0001 | |

OS, overall survival; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index

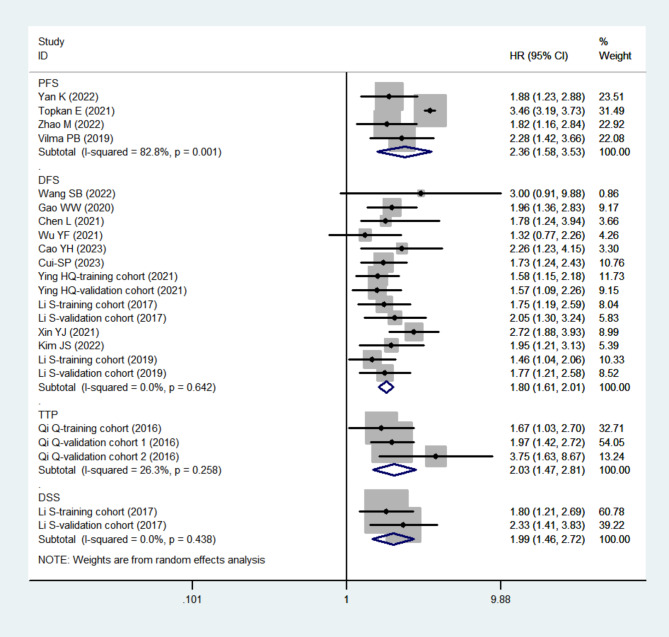

Relationship between SIRI and PFS/DFS/TTP/DSS

A total of four cohort studies with 668 participants [31, 43, 44, 47] assessed PFS, 14 cohort studies with 4672 participants [15, 18, 19, 26, 28, 32, 33, 37, 41, 46, 49] assessed DFS, three cohort studies with 574 participants [12] assessed TTP, and two cohort studies with 782 participants [19] assessed DSS. Elevated SIRI levels were associated with poorer outcomes, including PFS (HR = 2.36, 95% CI: 1.58–3.53, tau2 = 0.1319), DFS (HR = 1.80, 95% CI: 1.61–2.01, tau2 < 0.0001), TTP (HR = 2.03, 95% CI: 1.47–2.81, tau2 = 0.0232), and DSS (HR = 1.99, 95% CI: 1.46–2.72, tau2 < 0.0001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The forest plot for the association between SIRI and PFS/DFS/TTP/DSS in digestive system carcinomas. Abbreviations: DFS, disease free survival; DSS, disease specific survival; HR, hazard ratio; PFS, progression free survival; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index, TTP, time to progression

Heterogeneity was minimal for DFS (I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.642), TTP (I2 = 26.3%, p = 0.258), and DSS (I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.438) subgroups, whereas the PFS subgroup showed substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 82.8%, p = 0.001) (Fig. 3). Due to the limited number of cohort studies included, further meta-regression, subgroup, or sensitivity analyses were not performed for these outcomes.

Relationship between changes in SIRI and OS/TTP/DFS

A total of two cohort studies with 290 participants [12, 13], one cohort study with 202 participants [49], and one cohort study with 64 participants [12] investigated the impact of changes in SIRI levels post-treatment on OS, TTP, and DFS, respectively. A reduction of more than 75% in SIRI levels was associated with improved OS, TTP, and DFS (Fig. 4A), while a reduction of 25–75% was correlated with improved OS and DFS but not significantly associated with TTP, (Fig. 4B). An increase of 25–75% was not correlated with OS, TTP, or DFS (Fig. 4C). Conversely, an increase of more than 75% in SIRI levels was linked to poorer OS, TTP, and DFS (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

The forest plot for the association between changes in SIRI and OS/TTP/DFS in digestive system carcinomas. (A) SIRI decrease > 75%; (B) SIRI decrease 25-75%; (C) SIRI increase 25-75%; (D) SIRI increase > 75%. Abbreviations: DFS, disease free survival; OS, overall survival; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index, TTP, time to progression

Publication bias

Publication bias was assessed using Begg’s and Egger’s tests for OS and DFS. According to Begg’s test, no publication bias was detected for OS (p = 0.078) (Supplemental Fig. 7A), while Egger’s test indicated potential publication bias (p < 0.001) (Supplemental Fig. 7B). For DFS, both Begg’s and Egger’s tests showed no evidence of publication bias (p = 0.063; p = 0.080) (Supplemental Fig. 7C and 7D).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the robustness of the findings by sequentially excluding each cohort study. As shown in Supplemental Fig. 8, the exclusion of individual studies did not significantly alter the pooled HRs for OS (Supplemental Fig. 8A) or DFS (Supplemental Fig. 8B), indicating that the results were stable and reliable.

Discussion

The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate whether SIRI is associated with the prognosis of patients with DSC. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive review investigating the relationship between SIRI and prognosis in DSC patients. A total of 26 articles encompassing 9,628 participants across 34 cohort studies were included. Our analysis demonstrated that elevated SIRI levels were significantly correlated with poorer outcomes, including OS, as well as worse PFS, DFS, TTP, and DSS. Furthermore, an increase in SIRI after treatment was associated with a shorter OS, TTP, and DFS, whereas a decrease in SIRI was linked to improved outcomes in these parameters compared to baseline levels. These findings suggest that DSC patients with high SIRI levels may experience reduced survival rates, higher rates of disease progression, and increased recurrence rates. Given the presence of heterogeneity in the meta-analysis of OS, a meta-regression analysis was conducted to explore potential contributing factors, including country, sample size, SIRI cut-off values, treatment type, and tumor type. The cut-off values for the included studies were determined based on the respective populations of each study, and variations in these cutoff values did not significantly impact the results of the meta-analysis. As shown in Supplemental Fig. 3, SIRI remains closely associated with the prognosis of DSC, regardless of whether the cutoff value is > 1.2 or ≤ 1.2. Hence, subgroup analyses further confirmed that elevated SIRI levels were consistently associated with poorer OS, regardless of stratification by these factors. Collectively, these results indicate that SIRI may serve as a valuable prognostic biomarker for DSC patients.

This study was conducted in accordance with the REMARK guidelines, which provide detailed instructions on how to accurately report studies involving tumor markers. These guidelines include comprehensive checklists and examples to ensure clarity and transparency in the reporting process, facilitating a deeper understanding of the prognostic impact of tumor markers [24].

To further explore the clinical application of the SIRI, we propose that SIRI has potential as a screening tool to help identify high-risk patients with DSCs. For instance, by assessing SIRI levels, clinicians could identify patients who may benefit from more intensive monitoring or early intervention. Moreover, SIRI could support the decision-making process by guiding decisions on treatment escalation or de-escalation. Liu et al. found that higher SIRI levels were linked to poorer outcomes in HCC patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), suggesting that SIRI could serve as a non-invasive biomarker for predicting ICI efficacy [52]. Similarly, another study reported that lower SIRI levels were associated with increased survival in HCC patients receiving sorafenib [54]. In patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma and high SIRI levels, treatment with the mFOLFIRINOX regimen was associated with better outcomes compared to gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel or gemcitabine alone [43]. Additionally, patients with unresectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and high SIRI were found to benefit more from platinum-based chemotherapy than from gemcitabine-based regimens [42]. Conversely, Li et al. demonstrated that postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy significantly improved DFS and DSS in localised GC patients with low SIRI levels [19]. In cases of locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma, low SIRI levels were predictive of a favorable prognosis in patients undergoing concurrent chemoradiotherapy [45]. Furthermore, pre-treatment peripheral blood SIRI was identified as an independent predictor of tumor response and clinical outcomes in HCC patients undergoing transarterial chemoembolization [53]. Additionally, studies involving 124 gallbladder cancer patients and 232 cholangiocarcinoma patients indicated that those with higher SIRI levels were less likely to undergo radical surgery [47, 57]. Therefore, SIRI may help predict which patients are more likely to benefit from standard therapeutic regimens and which patients may require alternative or additional therapies. This personalized approach to treatment could optimize resource allocation and potentially improve patient outcomes.

Inflammation plays a critical role in the initiation and progression of DSC. Numerous endogenous inflammatory mediators, including proinflammatory cytokines, reactive nitrogen species, and reactive oxygen species (ROS), contribute to tumor development. The intake of food or chemical agents can lead to immune cell infiltration in the digestive organs, potentially perpetuating chronic inflammation, which increases the likelihood of tumorigenesis [58, 59]. The study found that T lymphocytes can secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines while simultaneously releasing the immunosuppressive factor IL-35, which plays a dual role in promoting tumor growth and anti-apoptosis [60]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are closely associated with inflammation and mediate metabolic immune regulation, playing a critical role in cancer progression. Metabolites produced by tumor cells activate immunosuppressive regulatory B cells via PPARα, thereby promoting tumor metastasis and immune evasion. Furthermore, increased PPARγ activity leads to elevated levels of ROS in tumors, which exacerbate tumor progression by increasing mutation rates and enhancing pathways that drive invasiveness [61].

The SIRI, a marker of both systemic inflammatory and local immune response, has been associated with the prognosis of various malignancies [20–22]. Several studies have shown that higher SIRI levels correlate with a greater tumor burden, including larger tumor size and more tumor lesions, in patients with various DSCs [31, 49]. Furthermore, patients with elevated SIRI levels tend to have higher tumour markers, more advanced clinicopathological stages, and poorer tumor differentiation compared to those with lower SIRI levels [13, 37, 47, 48, 57]. Additionally, Liu et al. demonstrated that dynamic changes in SIRI were more informative than TNM staging in evaluating the prognostic value of radical gastrectomy [14]. Li et al. also found that an elevated SIRI was strongly associated with lymphovascular and perineural invasion in patients with localised GC [19]. These findings may explain why high SIRI levels are associated with poorer prognoses in DSC patients.

SIRI may also promote tumour progression through various mechanisms. Cao et al. found that the species enrichment of the gut microbiota of CRC patients with low SIRI was significantly higher than that of the high SIRI group [37]. A decrease in beneficial bacteria in the intestine led to an increase in the secretion of toxic metabolites, which could cause the development of CRC [62]. Cancer stem cells, which play a key role in tumor initiation and metastasis, have also been linked to SIRI. A clinical study reported a positive correlation between SIRI levels and CD44 + cancer stem cells, which were more resistant to chemotherapy in patients with localised GC [19].

Several studies have combined SIRI with other tumour prognostic markers to create more robust predictive indices. These composite markers have demonstrated superior prognostic value compared to SIRI alone [33, 44]. For example, novel indicators incorporating SIRI have shown significant prognostic value in patients with resectable CRC and HCC [29, 40, 50]. Preoperative SIRI combined with CEA has been proposed as an important prognostic biomarker for CRC patients [39]. Additionally, SIRI combined with other inflammatory indices has been shown to better predict early recurrence following surgery in CRC and hepatitis B-associated HCC patients [38, 51]. Gao and Zhang et al. integrated SIRI with coagulation indices, revealing that these novel indicators were strongly correlated with poorer OS and DFS in patients with resectable GC [33, 34]. A pancreas cancer prognostic index (PCPI) based on CA19-9 and SIRI was also developed, with higher PCPI correlating with lymphatic metastases and poorer OS and PFS in patients with unresectable locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinomas [44]. The psoas muscle index (PMI), an indicator of sarcopenia, has been combined with SIRI to assess prognosis. HCC patients with low SIRI and high PMI demonstrated significantly better OS and PFS compared to those with high SIRI or low PMI [47]. Additionally, Yan et al. found that combining SIRI with PNI provided better predictive value for elderly patients with locally advanced ESCC than SIRI alone [31]. These findings collectively suggested that high SIRI levels are closely linked to poor prognosis in DSC patients.

Several mechanisms help explain why SIRI is a reliable prognostic indicator for DSC. Systemic inflammation and immunity play an important role in tumor progression. Neutrophils, for instance, have been shown to promoted tumour onset, progression, and metastasis through mechanisms such as gene damage induced by ROS, inhibition of immune cell activity, and stimulation of angiogenesis and cancer cell migration [63]. Zhang et al. suggested that neutrophils could exacerbate multi-organ damage in the digestive system by inducing inflammatory polarisation through SRC kinase and STAT1/STAT5 signaling pathways [64]. Intratumor neutrophils could also promote tumor cell proliferation and metastasis through paracrine secretion [65]. Monocytes are thought to link innate and adaptive immunity, facilitating immune tolerance, promoting angiogenesis, and aiding in the dispersion of tumor cells within the tumor microenvironment [66]. Monocytes can also disrupt the epithelial barrier of the digestive tract via IL-6 and CCL-2 signalling, contributing to digestive tract dysfunction [67]. Lymphocytes, on the other hand, play a tumor-suppressing role by inhibiting tumor proliferation and growth [68]. However, deficiencies in lymphocytes can lead to lower cytokine production, impairing anti-tumor immunity [22]. Given these mechanisms, it is understandable why the SIRI, calculated from the levels of neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes, serves as a prognostic marker for DSC.

The focus of this research has been primarily on Asia, particularly China, due to several factors. First, the incidence of DSC has been rapidly increasing in recent years, which has drawn significant attention in China. Second, given the large population of cancer patients in China, it is often impractical to conduct invasive or imaging examinations for all patients. As such, there is a pressing need for reliable, non-invasive scoring systems that can predict patient prognosis effectively.

This meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the prognostic value of SIRI for DSC, and it presents several notable strengths. Firstly, the cohort studies included were numerous and geographically diverse, enhancing the objectivity and representativeness of our findings. Second, by directly extracting data such as HRs and 95% CIs from the original studies, we minimized approximation bias while retaining crucial information. Additionally, we explored potential sources of heterogeneity using meta-regression and conducted multiple subgroup analyses. Finally, the sensitivity analysis, where we systematically excluded individual cohort studies, showed no significant changes in the results, reinforcing the stability and robustness of our findings.

Despite these strengths, there are several limitations to our study. First, significant heterogeneity was observed in the OS meta-analysis, even though all subgroup analyses—except for the non-metastatic subgroup—did not show heterogeneity. Second, the Egger’s test indicated publication bias in the OS meta-analysis, likely due to the exclusion of gray literature, and the difficulty in publishing negative results. However, the sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the pooled OS estimates remained reliable despite this bias. Third, we acknowledged that restricting the scope of our research to English-language literature may introduce selection bias, potentially excluding important studies in other languages and thereby affecting the generalizability and extrapolation of the results. This limitation may lead to an overestimation of treatment effects. Therefore, we recommend that readers interpret the findings with caution and advocate for future research to include multilingual literature to enhance the accuracy and representativeness of the results. Fourth, as there were few studies focusing on other prognostic indices such as PFS, TTP, DSS, publication bias and sensitivity analysis could not be performed for these outcomes. Fifth, the majority of the studies were concentrated in a specific region (Asia), which may limit the representativeness of our findings for other regions. Additionally, converting continuous SIRI values to categorical variables might lead to a loss of statistical power and potential residual confounding. Further studies with more depth are needed to determine whether SIRI can serve as a predictor of treatment response for DSC in the future.

We also considered other possible approaches to mitigate the impact of publication bias. For example, we conducted subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses by excluding studies that might have a higher risk of publication bias to assess their influence on the overall estimates. Additionally, we attempted to include grey literature, such as conference abstracts and unpublished studies, to capture a more comprehensive range of relevant studies. However, due to the challenges in accessing grey literature and its incomplete information, our efforts may not have fully eliminated the influence of publication bias. Future research should consider pre-registering study protocols, improving reporting standards, and encouraging the publication of negative results. These measures may help reduce publication bias and provide more accurate effect estimates.

Conclusion

In conclusion, elevated pre-treatment SIRI was associated with adverse prognostic outcomes in patient with DSC, despite some heterogeneity. SIRI has shown potential as an independent predictor of survival, recurrence and progression, which may help in predicting patients outcomes and enabling early, targeted interventions to improve survival. Moreover, SIRI is an easily accessible and cost-effective biomarker, making it suitable for routine prognostic screening in DSC patients. However, large-scale, high-quality studies from diverse geographical regions are required to further confirm the prognostic value of SIRI in the future.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

None declared.

Author contributions

Chunjun Xu and Fengxia Sun contributed to the study conception and design. Literature search, data collection and analysis were performed by Zuohu Niu, Li Lin, Hongye Peng and Xinzhuo Zheng. The figures and tables were prepared by Zuohu Niu, Li Lin and Miyuan Wang. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Zuohu Niu and Li Lin, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zuo-hu Niu and Li Lin contributed equally to this work and shared first authorship.

Contributor Information

Feng-xia Sun, Email: sunfengxia01969@163.com.

Chun-jun Xu, Email: xu1409@126.com.

References

- 1.Li J, Xu Q, Huang ZJ, Mao N, Lin ZT, Cheng L, Sun B, Wang G. CircRNAs: a new target for the diagnosis and treatment of digestive system neoplasms. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(2):205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li HS, He T, Yang LL. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the digestive system: a literature review. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(11):1268–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu X, Ming X, Jing W, Luo P, Li N, Zhu M, Yu M, Liang C, Tu J. Long non-coding RNA XIST predicts worse prognosis in digestive system tumors: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Biosci Rep. 2018;38(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Feng X, Li Z, Guo W, Hu Y. The effects of traditional Chinese medicine and dietary compounds on digestive cancer immunotherapy and gut microbiota modulation: a review. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1087755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landskron G, De la Fuente M, Thuwajit P, Thuwajit C, Hermoso MA. Chronic inflammation and cytokines in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014:149185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Denk D, Greten FR. Inflammation: the incubator of the tumor microenvironment. Trends cancer. 2022;8(11):901–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma N, Jha S. NLR-regulated pathways in cancer: opportunities and obstacles for therapeutic interventions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(9):1741–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Q, Qiao W, Liu B, Li J, Yuan C, Long J, Hu C, Zang C, Zheng J, Zhang Y. The monocyte to lymphocyte ratio not only at baseline but also at relapse predicts poor outcomes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma receiving locoregional therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22(1):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Lin S, Yang X, Wang R, Luo L. Prognostic value of pretreatment systemic immune-inflammation index in patients with gastrointestinal cancers. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(5):5555–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li B, Zhou P, Liu Y, Wei H, Yang X, Chen T, Xiao J. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in advanced cancer: review and meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2018;483:48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qi Q, Zhuang L, Shen Y, Geng Y, Yu S, Chen H, Liu L, Meng Z, Wang P, Chen Z. A novel systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting the survival of patients with pancreatic cancer after chemotherapy. Cancer. 2016;122(14):2158–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geng Y, Zhu D, Wu C, Wu J, Wang Q, Li R, Jiang J, Wu C. A novel systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting postoperative survival of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;65:503–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Z, Ge H, Miao Z, Shao S, Shi H, Dong C. Dynamic changes in the systemic inflammation response index predict the outcome of resectable gastric cancer patients. Front Oncol. 2021;11:577043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui S, Cao S, Chen Q, He Q, Lang R. Preoperative systemic inflammatory response index predicts the prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1118053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Min L, Ziyu D, Xiaofei Z, Shunhe X, Bolin W. Analysis of levels and clinical value of CA19-9, NLR and SIRI in patients with pancreatic cancer with different clinical features. Cellular and molecular biology (Noisy-le-Grand, France). 2022;67(5):302–308. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Xu X, Jing J. Inflammation-related parameter serve as prognostic biomarker in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2022;12:900305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang SB, Chen JY, Xu C, Cao WG, Cai R, Cao L, Cai G. Evaluation of systemic inflammatory and nutritional indexes in locally advanced gastric cancer treated with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy after D2 dissection. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1040495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li S, Lan X, Gao H, Li Z, Chen L, Wang W, Song S, Wang Y, Li C, Zhang H, et al. Systemic inflammation response index (SIRI), cancer stem cells and survival of localised gastric adenocarcinoma after curative resection. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143(12):2455–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei L, Xie H, Yan P. Prognostic value of the systemic inflammation response index in human malignancy: a meta-analysis. Medicine. 2020;99(50):e23486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Liu F, Wang Y. Evidence of the prognostic value of pretreatment systemic inflammation response index in cancer patients: a pooled analysis of 19 cohort studies. Disease markers. 2020;2020:8854267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Zhou Q, Su S, You W, Wang T, Ren T, Zhu L. Systemic inflammation response index as a prognostic marker in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 38 cohorts. Dose-response: Publication Int Hormesis Soc. 2021;19(4):15593258211064744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Res ed). 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altman DG, McShane LM, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2012;9(5):e1001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Côté P, Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):280–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ying HQ, Liao YC, Sun F, Peng HX, Cheng XX. The role of cancer-elicited inflammatory biomarkers in predicting early recurrence within stage II-III colorectal cancer patients after curable resection. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:115–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamposioras K, Papaxoinis G, Dawood M, Appleyard J, Collinson F, Lamarca A, Ahmad U, Hubner RA, Wright F, Pihlak R, et al. Markers of tumor inflammation as prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer receiving first-line FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy. Acta Oncol (Stockholm Sweden). 2022;61(5):583–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li S, Xu H, Wang W, Gao H, Li H, Zhang S, Xu J, Zhang W, Xu S, Li T, et al. The systemic inflammation response index predicts survival and recurrence in patients with resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Manage Res. 2019;11:3327–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng Z, Guan R, Zou Y, Jian Z, Lin Y, Guo R, Jin H. Nomogram based on inflammatory biomarkers to predict the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma-a multicentre experience. J Inflamm Res. 2022;15:5089–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang HK, Wei Q, Yang YL, Lu TY, Yan Y, Wang F. Clinical usefulness of the lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio and aggregate index of systemic inflammation in patients with esophageal cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Cancer Cell Int. 2023;23(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan K, Wei W, Shen W, Du X, Zhu S, Zhao H, Wang X, Yang J, Zhang X, Deng W. Combining the systemic inflammation response index and prognostic nutritional index to predict the prognosis of locally advanced elderly esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients undergoing definitive radiotherapy. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;13(1):13–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen L, Chen Y, Zhang L, Xue Y, Zhang S, Li X, Song H. In gastric cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy systemic inflammation response index is a useful prognostic indicator. Pathol Oncol Research: POR. 2021;27:1609811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao W, Zhang F, Ma T, Hao J. High preoperative fibrinogen and systemic inflammation response index (F-SIRI) predict unfavorable survival of resectable gastric cancer patients. J Gastric Cancer. 2020;20(2):202–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J, Ding Y, Wang W, Lu Y, Wang H, Wang H, Teng L. Combining the fibrinogen/albumin ratio and systemic inflammation response index predicts survival in resectable gastric cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:3207345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puhr HC, Weirauch CC, Selimi F, Oberreiter K, Dieterle MA, Jomrich G, Schoppmann SF, Prager GW, Berghoff AS, Preusser M, et al. Systemic inflammatory biomarkers as prognostic tools in patients with gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(19):17081–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yazici H, Yegen SC. Is systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) a reliable tool for prognosis of gastric cancer patients without neoadjuvant therapy? Cureus. 2023;15(3):e36597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Cao Y, Zheng X, Hu Y, Li J, Huang B, Zhao N, Liu T, Cai K, Tian S. Levels of systemic inflammation response index are correlated with tumor-associated bacteria in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(1):69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cai X, Chen F, Liang L, Jiang W, Liu X, Wang D, Wu Y, Chen J, Guan G, Peng XE. A novel inflammation-related prognostic biomarker for predicting the disease-free survival of patients with colorectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20(1):79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cai H, Chen Y, Zhang Q, Liu Y, Jia H. High preoperative CEA and systemic inflammation response index (C-SIRI) predict unfavorable survival of resectable colorectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2023;21(1):178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cai H, Li J, Chen Y, Zhang Q, Liu Y, Jia H. Preoperative inflammation and nutrition-based comprehensive biomarker for predicting prognosis in resectable colorectal cancer. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1279487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim JS, Choi M, Kim SH, Hwang HK, Lee WJ, Kang CM. Systemic inflammation response index correlates with survival and predicts oncological outcome of resected pancreatic cancer following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Pancreatology: Official J Int Association Pancreatology (IAP) [et al]. 2022;22(7):987–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dâmaso S, Paiva R, Pinho I, Esperança-Martins M, Lopes Brás R, Melo Alvim C, Quintela A, Lúcia Costa A, Costa L. Systemic inflammatory response index is a prognostic biomarker in unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma and identifies patients for more intensive treatment. memo - Magazine Eur Med Oncol. 2022;15(3):246–52. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pacheco-Barcia V, Mondéjar Solís R, France T, Asselah J, Donnay O, Zogopoulos G, Bouganim N, Guo K, Rogado J, Martin E, et al. A systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) correlates with survival and predicts oncological outcome for mFOLFIRINOX therapy in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology: Official J Int Association Pancreatology (IAP) [et al]. 2020;20(2):254–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Topkan E, Selek U, Pehlivan B, Kucuk A, Haksoyler V, Kilic Durankus N, Sezen D, Bolukbasi Y. The prognostic significance of novel pancreas cancer prognostic index in unresectable locally advanced pancreas cancers treated with definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:4433–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Topkan E, Mertsoylu H, Kucuk A, Besen AA, Sezer A, Sezen D, Bolukbasi Y, Selek U, Pehlivan B. Low systemic inflammation response index predicts good prognosis in locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma patients treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:5701949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Wu Y, Tu C, Shao C. Inflammatory indexes in preoperative blood routine to predict early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative hepatectomy. BMC Surg. 2021;21(1):178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao M, Duan X, Han X, Wang J, Han G, Mi L, Shi J, Li N, Yin X, Hou J, et al. Sarcopenia and systemic inflammation response index predict response to systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma and are associated with immune cells. Front Oncol. 2022;12:854096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu L, Yu S, Zhuang L, Wang P, Shen Y, Lin J, Meng Z. Systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) predicts prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8(21):34954–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xin Y, Zhang X, Li Y, Yang Y, Chen Y, Wang Y, Zhou X, Li X. A systemic inflammation response index (SIRI)-based nomogram for predicting the recurrence of early stage hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency ablation. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2022;45(1):43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mao S, Yu X, Sun J, Yang Y, Shan Y, Sun J, Mugaanyi J, Fan R, Wu S, Lu C. Development of nomogram models of inflammatory markers based on clinical database to predict prognosis for hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wenpei G, Yuan L, Liangbo L, Jingjun M, Bo W, Zhiqiang N, Yijie N, Lixin L. Predictive value of preoperative inflammatory indexes for postoperative early recurrence of hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1142168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu C, Zhao H, Zhang R, Guo Z, Wang P, Qu Z. Prognostic value of nutritional and inflammatory markers in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who receive immune checkpoint inhibitors. Oncol Lett. 2023;26(4):437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang TC, An TZ, Li JX, Pang PF. Systemic inflammation response index is a prognostic risk factor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing TACE. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:2589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pence S, Caykara B, Pence HH, Tekin S, Keskin BC, Uncu AT, Uncu AO, Ozturk E. Transcriptomic analysis of asymptomatic and symptomatic severe Turkish patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection. North Clin Istanbul. 2022;9(2):122–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen Y, Jin M, Shao Y, Xu G. Prognostic value of the systemic inflammation response index in patients with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction: a propensity score-matched analysis. Disease markers. 2019;2019:4659048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Jin B, Hu W, Su S, Xu H, Lu X, Sang X, Yang H, Mao Y, Du S. The prognostic value of systemic inflammation response index in cholangiocarcinoma patients. Cancer Manage Res. 2021;13:6263–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun L, Hu W, Liu M, Chen Y, Jin B, Xu H, Du S, Xu Y, Zhao H, Lu X, et al. High systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) indicates poor outcome in gallbladder cancer patients with surgical resection: a single institution experience in China. Cancer Res Treat. 2020;52(4):1199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chiba T, Marusawa H, Ushijima T. Inflammation-associated cancer development in digestive organs: mechanisms and roles for genetic and epigenetic modulation. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(3):550–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tahara T, Arisawa T. Potential usefulness of DNA methylation as a risk marker for digestive cancer associated with inflammation. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2012;12(5):489–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khalil RG, Mohammed DA, Hamdalla HM, Ahmed OM. The possible anti-tumor effects of regulatory T cells plasticity / IL-35 in the tumor microenvironment of the major three cancer types. Cytokine. 2024;186:156834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pratama AM, Sharma M, Naidu S, Bömmel H, Prabhuswamimath SC, Madhusudhan T, Wihadmadyatami H, Bachhuka A, Karnati S. Peroxisomes and PPARs: emerging role as master regulators of cancer metabolism. Mol Metabolism. 2024;90:102044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sepich-Poore GD, Zitvogel L, Straussman R, Hasty J, Wargo JA, Knight R. The microbiome and human cancer. Science (New York, NY). 2021;371(6536). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Xiong S, Dong L, Cheng L. Neutrophils in cancer carcinogenesis and metastasis. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang Y, Lin R, Pradhan K, Geng S, Li L. Innate priming of neutrophils potentiates systemic multiorgan injury. ImmunoHorizons. 2020;4(7):392–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ren J, Ma Y, Wei M, Li Z. Effects of intravenous anesthesia and inhalation anesthesia on postoperative inflammatory markers in patients with esophageal cancer: a retrospective study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024;24(1):462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ugel S, Canè S, De Sanctis F, Bronte V. Monocytes in the tumor microenvironment. Annu Rev Pathol. 2021;16:93–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Delbue D, Cardoso-Silva D, Branchi F, Itzlinger A, Letizia M, Siegmund B, Schumann M. Celiac disease monocytes induce a barrier defect in intestinal epithelial cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(22). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Heinzel S, Marchingo JM, Horton MB, Hodgkin PD. The regulation of lymphocyte activation and proliferation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2018;51:32–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.