Abstract

Background

Children are anxious when hospitalized due to being away from home and undergoing treatment.This anxiety has an effect on their disease process, treatment, growth and development.Children’s anxiety has an effect on parents’ anxiety and can lead to lower level of cooperation among the children and their parents with the treatment team.the present study aimed to compare the effect of play therapy and storytelling on the anxiety of hospitalized children.

Methods

A randomized controlled trial study with a three-group design (play therapy, storytelling and control) was conducted in 75 children aged 3 to 10 years admitted to Imam Ali Alborz Hospital of Karaj, Iran between 2022–2023.The data before and after the intervention were collected by the Spence children’s anxiety scale and the face tool for anxiety assessment and analyzed by the Mixed effect model statistical method.

Results

There is a statistically significant difference between the anxiety score of the children for whom storytelling was used and control group. Also, among the two therapies of storytelling and play therapy, only storytelling therapy has a significant effect on reducing children’s anxiety.Regarding the time of measuring the anxiety score(the first, second, third day after the intervention), it was found that as this time increases, the children’s anxiety decreases significantly.morever, the children’s gender, age, and history of hospitalization are influencing factors.

Conclusion

Play therapy and storytelling play an effective role in controlling the anxiety of hospitalized children, although storytelling had a greater role in reducing the anxiety of hospitalized children than play therapy. It is suggested to provide the necessary conditions and facilities for the implementation of these methods in children’s inpatient departments.

Trial registration

https://irct.behdasht.gov.ir/ ,IRCT20220704055367N1,13/7 /2022.

Keywords: Play therapy, Storytelling, Anxiety, Hospitalized children, Mother

Introduction

Anxiety is the most common emotion experienced by hospitalized children [1]. Anxiety in children is associated with fatigue, low energy, obesity, and impaired growth and development [2]. Hospitalization is always considered as a negative anxiety-inducing experience [3], which can have significant health effects on children [4]. Fear of separation from parents is an attachment style and a normative experience in which children experience negative feelings or emotions such as sadness, loneliness, or loss [5]. When admitted to the hospital, a new situation occurs that is accompanied by stress for the patient and his family, especially if the patient is a child because he depends on his parents for help and support to deal with the disease [6].

In fact, the moment of a child’s admission to the hospital is stressful for the treatment staff in addition to the child and his parents. However, the treatment staff helps them to interact with the parents and transfer their experiences. Hospitalization of children causes anxiety, stress, and depression in parents [7]. Anxiety in parents occurs when nursing procedures such as blood sampling, infusion, injection, and other procedures are performed on the child [8]. Research shows that stress increases in parents during the child’s hospitalization period and before it. Findings show that parental stress can affect the child in two ways: First, parental stress increase enables them to help their children. Secondly, the increase of stress in parents transfers the stress to the child [9].

Besides stress transfer from the parents to the hospitalized child, being hospitalized for children means leaving home and being away from their caregivers, siblings, and a break in their daily activities [10]. Furthermore, hospital wards are often associated with staying in a cold and medical environment, facing fear of medical examinations, pain, immobility, uncertainty, separation from family members, and creating disturbances [11], especially in primary school children who are involved in mental, emotional, and social developmental tasks [12].

Hospitalized children should be seen as active and participating individuals in the hospitalization process. The provided care should consider emotional and social needs and include techniques that enable communication in addition to meeting physical needs [13]. Effective early interventions targeting children can improve their social-emotional competencies and prevent the onset of significant distress, future injuries, and mental disorders such as depression in adolescence and adulthood. Playing is one of the vital factors in the natural growth and development of children, improving self-confidence, anxiety, social skills, resilience, social-emotional competencies, and behavioral problems [14]. During hospitalization, play therapy is necessary not only because children love to play, but also because it facilitates medical interventions. Play is an essential activity in a child’s life, so it can help children face this unknown situation, express their feelings and concerns, feel more comfortable and safe, get to know medical techniques, and make decisions during hospitalization [15].

Several studies have shown that play therapy can be beneficial for hospitalized children. For instance, a study found that children who participated in structured play therapy during their hospital stay experienced lower levels of anxiety and distress compared to those who did not [16]. Similarly, another study demonstrated that play interventions can help children understand medical procedures, reducing their fear and increasing cooperation with healthcare providers. Furthermore, play therapy has been linked to long-term benefits, such as improved social-emotional functioning and coping skills [17].

Storytelling has also emerged as an effective tool for managing anxiety in hospitalized children. Research on storytelling as a preoperative intervention suggests that it can help children process and understand medical experiences. In some studies, researchers used a children’s storybook about a rabbit undergoing surgery, presented through illustrated drawings and interactive sessions with the child and their parents. The results indicated that storytelling significantly reduced both child and parent anxiety and enhanced the child’s cooperation with medical staff [18, 19]. Subsequent studies have further supported the idea that storytelling can mitigate fear and anxiety, particularly in children facing unknown or distressing hospital procedures [12, 20]. Studies on the effectiveness of storytelling on hospitalized children have shown that these children cope with anxiety, fear, and worry. Researchers have investigated the effect of using children’s story books on the preoperative preparation of children and their parents. They presented the story of a rabbit hospitalized for surgery in the form of colored drawings book to children and parents during a few sessions tailored to the child’s understanding with mutual interaction and question-answer to ensure his understanding of the story content. The results showed that storytelling reduces the anxiety of children and parents and increases cooperation with the staff [21].

The choice of play therapy and storytelling as interventions for hospitalized children is grounded in the understanding that hospitalization itself is a stressful and anxiety-inducing experience for young patients. These interventions were selected due to their well-documented benefits in alleviating anxiety, fostering emotional expression, and improving coping mechanisms in children facing medical challenges. However, while the benefits of both play therapy and storytelling have been noted in existing literature, there is a noticeable gap in the combined use of these interventions to address the anxiety of hospitalized children. Although both approaches individually have demonstrated positive effects, limited research has examined their joint impact on children’s emotional well-being during hospitalization. Specifically, studies exploring how these two interventions interact to alleviate anxiety and improve coping strategies in hospitalized children are scarce. Most of the current literature focuses on either play therapy or storytelling in isolation, without investigating their combined potential. As such, the present study aims to fill this gap by evaluating the effects of both play therapy and storytelling on the anxiety levels of hospitalized children, providing new insights into the effectiveness of these interventions when used together.

Methods

Study design

This randomized, single-blind, controlled trial was approved by Ethics Committee of Alborz University of Medical Sciences (Approval ID: IR.ABZUMS.REC.1401.084). The trial adhered to the CONSORT guidelines. All individuals gave written consent prior to study participation.

Participants and randomization

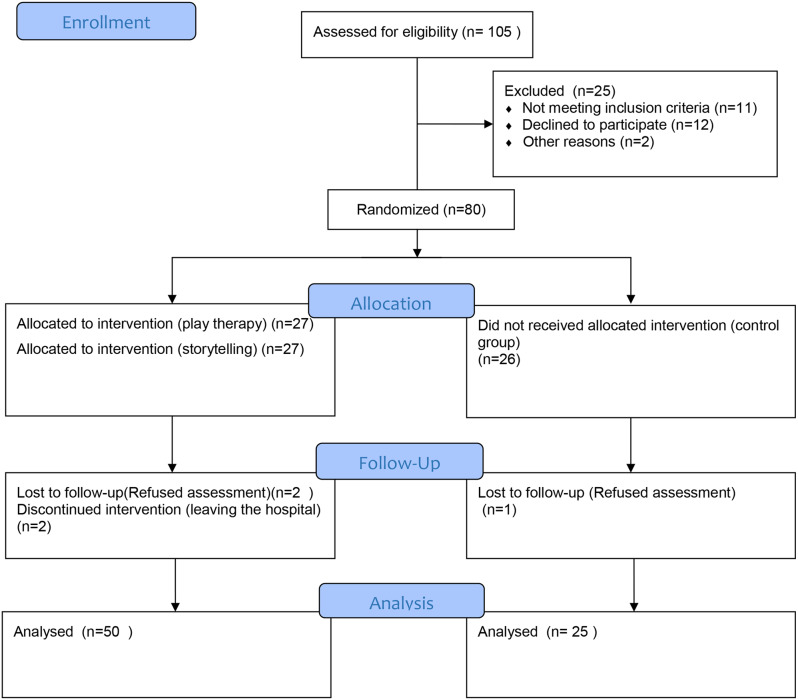

The research population consisted of children hospitalized in Imam Ali Hospital of Karaj in Alborz Province, Iran. The inclusion criteria involved children aged 3 to 10 years, being admitted to the ward for at least 48 h, staying in the hospital for at least 5 days, and obtaining informed consent from the child’s parents. The exclusion criteria included having cognitive, neurological, and learning problems, child unconsciousness, and inability to participate in the interventions [22]. The required sample size with a confidence factor of 95% (5% error rate) and a test power of 95% was 25 for each group, using the sample size formula and the study of Davidson et al. [23]. After obtaining consent from the parents and ensuring the confidentiality of their information, 75 childrenTotally, 75 children were included (n = 25 for each group) meeting the inclusion criteria were selected from among those referring pediatric ward of Imam Ali Hospital of Karaj, Iran from 2022 to 2023 until reaching the required sample size using the limited randomization method according to the random allocation rule. The CONSORT flowchart is illustrated in Fig. 1. For this purpose, a random sequence was generated based on three groups using Random Allocation Software 2.0, and then the participants were assigned to three groups: storytelling group (A), play therapy group (B), and control group (C).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flowchart

See Fig. 1 for an overview of the screening and recruitment process.

To prevent bias in the selection and assignment of participants, a limited randomization method was used. First, a random sequence was generated based on three groups ([A], [B], and [C]) using Random Allocation Software 2.0. This process ensured that participants were randomly assigned to each of the three groups according to the random allocation rule, reducing selection bias. In addition, the allocation was concealed, meaning that the person assigning participants to groups was unaware of the group allocations at the time of assignment, further reducing the risk of bias. Moreover, both the participants and the research team conducting the interventions were blinded to group assignments (single-blind design) to minimize performance and detection bias. To ensure that the sample was representative and that randomization was properly implemented, the process was continuously monitored by an independent researcher who was not involved in the interventions.

Intervention procedure

Demographic profile questionnaire

Initially, a demographic profile questionnaire was used to collect the children’s personal information based on parents’ responses to the questions at the first day. Additionally, other questionnaires were completed by each participant before the interventions began. In other words, the data collected on the first day correspond to the period prior to the start of the interventions. Parents were allowed to stay with their children during the procedures, ensuring the children felt secure in a familiar presence.

Control group

In the control group, the usual ward procedures were carried out. These included monitoring vital signs, administering injections, and providing drug therapy as prescribed by the attending physician. No additional therapeutic interventions were implemented in this group.

Play therapy intervention

In the play therapy group, children participated in therapeutic play sessions using toy medical kits to engage in patient-doctor role play. Additionally, medical equipment available in the hospital, such as microsets, cotton, needleless syringes, and abselang, were used to create craft activities. Play therapy was conducted individually for each child, under the supervision of the researcher. The intervention lasted for 30 min each day for 2 consecutive days. The goal of this intervention was to reduce anxiety and help children process their medical experiences through play.

Storytelling intervention

In the storytelling group, two books were used to address the children’s hospital experience:

On the first day, the book “Should I Go to the Hospital?” by Pat Thomas, translated by Dr. Geeta Mullally, was read to the children.

On the second day, the book “Franklin Goes to the Hospital” by Paulette Bourgeois, translated by Shohreh Hashemi, was read by either the child’s parents or one of the researchers.

The goal of the storytelling intervention was to familiarize children with the hospital environment and reduce anxiety through narrative and familiarization with hospital procedures.

Anxiety measurement

After the interventions, children’s anxiety levels were assessed using two anxiety scales:

Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS).

Visual Facial Anxiety Scale (VFAS).

A blinded researcher collected the data from the children to measure their anxiety levels. In the groups, anxiety was measured daily using the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale. For children aged 3–4 years, parents were asked to respond to the SCAS questions based on their observations of the child’s behavior. For children aged 5–10 years, the SCAS was administered directly to the children, with any clarifications provided if needed. Notably, children’s anxiety was measured over three consecutive days.

Mesurements

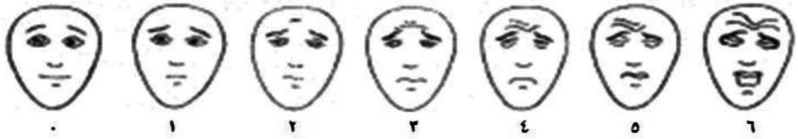

The data collection tool included a demographic questionnaire, including child age and gender, the number of children, the number of pregnancies, the use of assisted reproductive technology, what number the hospitalized child is for the mother’s child? and the shadow of hospitalization. We used two anxiety scales as complementary: (1) general measures of anxiety and severity of anxiety (2) administered by self-report.The Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (1997) was designed to assess the anxiety of children [24], consisting of 45 questions and six domains and measuring children’s anxiety based on a four-point Likert scale (never: 0, sometimes: 1, often: 2, always: 3). The six investigation domains include separation anxiety, social anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic-agoraphobia, generalized anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. A 0–44 score indicates a low level of children’s anxiety, 44–88 a medium level of anxiety, and above 88 a high level of anxiety. Cronbach’s alpha in Zargami’s research et al. for this questionnaire was estimated above 0.7 (0.86) [25]. The Visual Facial Anxiety Scale was invented in 1990 by Piyeri. According to the images below (Fig. 2), the Visual Facial Anxiety Scale for anxiety assessment includes seven facial expressions with a number under each, which makes a numerical scale of 0 to 6. Face 1 has a neutral expression, but faces 2–7, respectively, show the increase in anxiety. This tool is shown to the child to measure anxiety; he is asked to report his anxiety corresponding to one of the faces [26].

Fig. 2.

Five-face scale for assessing distress in children modified smiley faces scale. Aadpted from [16]

Analysis method

The Mixed effect model statistical method was used to analyze the data. Assuming the data structure and baseline time control, the random intercept effect was used in this model so that possible heterogeneity was also controlled with this method. Also, due to the non-normal distribution of the data, this model was fitted to the data based on the inverse Gaussian distribution. Since the response scale for 3-8-year-old children was different from 8-10-year-old children, first the data was normalized and then the desired model was fitted to the data to homogenize the scale and involve all children in the study and accurately compare the results. To achieve the most accurate results in this model, the effect of some variables was controlled, listed in Table 1. Finally, SPSS 22 was used for data analysis; the significance level was set at 0.05.

Table 1.

Description of children’s anxiety in different times and treatment groups

| Group | Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| First day | Second day | Third day | |

| Mean ± SD, [Median (IQR)] | |||

| Storytelling |

0.32 ± 0.17 [0.33 (0.33)] |

0.14 ± 0.15 [0.17 (0.29)] |

0.17 ± 0.15 [0.17 (0.25)] |

| Play Therapy |

0.36 ± 0.18 [0.33 (0.33)] |

0.15 ± 0.16 [0.17 (0.17)] |

0.23 ± 0.19 [0.17 (0.17)] |

| Control |

0.31 ± 0.25 [0.29 (0.50)] |

0.17 ± 0.20 [0.17 (0.33)] |

0.26 ± 0.23 [0.25 (0.33)] |

SD: Standard deviation, IQR: Interquartile range

Tiral registration

The study registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (Code: IRCT20220704055367N1) as of July 13, 2022; it is avalible at the website: https://irct.behdasht.gov.ir/.

Results

Children who participated in the study (Table 2) were 52% boys and 48% girls with a mean age of 6.48 years (SD 2.48).Overall, 75 interested children responded to study recruitment. Please see Fig. 1 for an overview of the screening and recruitment process. Table 1 describes the variable of children’s anxiety, the results of which include the mean, standard deviation, median, and the interquartile range of children’s anxiety by treatment groups at different times. Analyzing the data at baseline (before the intervention) revealed that there was no statistically significant difference between the three groups (p-value = 0.63). The results showed a statistically significant difference between the anxiety scores of children whom storytelling (A) was used for and the children of the control group (C). Only the storytelling therapy had a significant effect on reducing children’s anxiety among the two therapies of storytelling and play therapy (B). It was found that as this time increases, children’s anxiety decreases significantly with regard to the anxiety score’s measurement time (first day, second day, and third day after the intervention). Furthermore, it was found that children with no history of hospitalization had less anxiety than other children with a history of hospitalization. In terms of gender, boys had less anxiety compared to girls. Age is also a factor affecting children’s anxiety, so that with increasing age, children’s anxiety decreases (Table 3).

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of the participants

| Variable | Category | N (%), Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Storytelling | 25 (33.30) |

| Play Therapy | 25 (33.30) | |

| Control | 25 (33.30) | |

| Age | - | 6.48 ± 2.48 |

| Sex | Boy | 36 (48.00) |

| Girl | 39 (52.00) | |

| IVF | No | 71 (94.70) |

| Yes | 4 (5.30) | |

| Hospitalization history | No | 33 (44.00) |

| Yes | 42 (56.00) | |

| Number of children | 1 | 27 (36.00) |

| 2 | 37 (49.30) | |

| 3 | 10 (13.30) | |

| 4 | 1 (1.40) | |

| Child rank | 1 | 31 (41.30) |

| 2 | 34 (45.30) | |

| 3 | 9 (12.00) | |

| 4 | 1 (1.40) | |

| Number of pregnancies | 1 | 20 (26.70) |

| 2 | 29 (38.70) | |

| 3 | 18 (24.00) | |

| 4 | 8 (10.60) |

N: Frequency, SD: Standard deviation

Table 3.

Random intercept mixed effect model results to examine the effect of independent variables on the children’s anxiety

| Variable | Estimate | %95 CI for estimate | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Storytelling | -0.07 | (-0.13, -0.008) | 0.03 |

| Play Therapy | -0.04 | (-0.11, 0.03) | 0.24 | |

| Control | 0 | - | - | |

| Gender | Boy | -0.06 | (-0.11, -0.008) | 0.001 |

| Girl | 0 | - | - | |

| IVF | No | -0.01 | (-0.13, 0.10) | 0.85 |

| Yes | 0 | - | - | |

| Hospitalization history | No | -0.11 | (-0.16, -0.05) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 0 | - | - | |

| Time | -0.05 | (-0.08, -0.02) | 0.001 | |

| Age | -0.02 | (-0.03, -0.002) | 0.02 | |

| Number of children | 0.10 | (-0.01, 0.21) | 0.07 | |

| Child rank | -0.07 | (-0.17, 0.03) | 0.16 | |

| Number of pregnancies | -0.04 | (-0.08, 0.004) | 0.08 |

CI: Confidence interval

Other results revealed that in children aged 3–8, both storytelling and play therapy could reduce children’s anxiety. In children aged 8–10, storytelling had no significant effect on controlling their anxiety, while playing therapy increased their anxiety, which is a negative effect (Table 4). Regarding other variables, children having mothers with no history of undergoing IVF had a lower anxiety score; also, the older the child in the family, the lower his/her anxiety.

Table 4.

Different effects of storytelling on children’s anxiety based on age group

| Age group | Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First day | Second day | Third day | ||

| Mean ± SD, [Median (IQR)] | p-value | |||

| 3–8 |

0.34 ± 0.15 [0.33 (0.33)] |

0.10 ± 0.13 [0.01 (0.17)] |

0.13 ± 0.11 [0.17 (0.17)] |

< 0.001 |

| 8–10 |

0.27 ± 0.18 [0.33 (0.33)] |

0.22 ± 0.16 [0.25 (0.25)] |

0.24 ± 0.18 [0.25 (0.33)] |

0.65 |

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the effectiveness of play therapy and storytelling on children’s anxiety and indicated that play therapy and storytelling have an effective role in controlling the anxiety of hospitalized children although storytelling had a greater impact compared to play therapy in reducing the anxiety of hospitalized children.

The biggest stress of children when admitted to the hospital is separation anxiety, which can be accompanied by symptoms such as anorexia, sleep disorders, quiet crying, teasing, and poor cooperation with the medical staff. Hence, storytelling can be used as an effective method along with other treatments [27]. In line with the present results, the study of Cooper et al. (2019) showed that storytelling is a very effective tool in communicating with the patient, and this becomes much easier with the Internet and virtual space [28]. Also, Al-Khotani et al. (2016) showed that audio-visual distraction techniques during dental visits can be effective in reducing situational anxiety and behavioral disorders of children [29]. Storytelling is one of the best ways to counsel children and allows them to deal with feelings, thoughts, and behaviors that they are not yet able to talk about directly with their counselor. The purpose of storytelling is to acquaint children with the hospitalization process, so nurses should acquaint them and their family with the hospital personnel, peers, and the physical environment since children return to their previous stages to deal with the stress caused by hospitalization when placed in an unfamiliar environment [30].

The present results are in line with previous studies regarding the positive effect of play therapy on reducing the anxiety of hospitalized children. In the study of Zengin et al. (2020), play therapy was developed in the framework of a dramatic play with the active participation of children. For 45 min, the children played with toys such as dolls and plastic animal figurine toys and engaged in activities such as singing, puzzles, computer games, watching movies, played with clinical instruments such as cannula without needle injection, cotton, volume expander and its stand, plaster, and playing medical toy doll. The results indicated that play therapy reduced children’s anxiety and fear [31]. In Silva et al.‘s (2017) randomized clinical trial, children were asked to draw an image of a person in the hospital after accessing the toy and participating in the Dramatic Therapeutic Play (DTP) session applied by the researchers. Then the child was asked this question: “Can you kill someone in the hospital?” The results showed 75% of children with a low anxiety score with an average CD: H score of 73.9 and 69.4 in the intervention and control groups, respectively [32]. Also, Li et al. (2016) evaluated 304 hospitalized children subjected to game interventions for 30 min a day and found that the children in the intervention group experienced lower levels of anxiety and negative emotions [33].

The current findings are consistent with previous studies reporting that both play therapy and storytelling are directly related to the reduction of children’s anxiety symptoms [5, 34]. Moreover, Shahrabadi et al. (2016) conducted a semi-experimental study to investigate the effect of story books and face-to-face teaching on children’s anxiety level. Children and their mothers were randomly divided into three groups of story books, face-to-face, and routine. The results manifested a significant difference in children’s anxiety after the intervention between the two groups of storybook and routine, but no significant difference was observed between the storybook group and face-to-face and face-to-face method with routine [26]. Others showed that play therapy intervention is effective in reducing children’s anxiety symptoms [35, 36]. Play therapy causes mental well-being and obviously increases the ability to cope with depression [37]. In other words, the therapist creates a general game situation through play therapy, where the child can release his fear and stress. In other words, the child shows his inner self through play therapy, and the therapist can understand feelings such as hatred, fear, loneliness, insecurity, failure, incompetence, and unwanted [38]. Play therapy is a symbolic way for the child to understand what his roles are and to understand what exactly happened and how to solve them. Thus, his/her functional level increases. Play therapy is not only limited to revealing the internal problems of children. When a therapist encounters an anxious or depressed child, he can imagine the reasons and different assumptions for the cause of these problems, the choice of which may find a more coherent state for diagnosis regarding the type of toy, the method, and the content of the child’s expressions with the toy [39, 40]. The analysis of a systematic study on the effectiveness of play therapy in hospitalized children with cancer recommended play therapy in reducing hospitalization of children as it is simple, does not require many tools and materials, and is easy, affordable, and practical [41].

Regarding the time of measuring the anxiety score (first, second, third day after the intervention), it was found that as this time increased, the anxiety of children decreased significantly. Al-Yateem et al. (2016) conducted a study to assess the effect of unstructured play on the anxiety of hospitalized children. Special care was taken to adjust play to each child’s physical capacity and for those with limited exercise tolerance. They used games that required minimal energy from the child. They performed game activities twice a day for an average of 30 min per session. The results revealed that anxiety scores decreased significantly within 3 days [42]. Another study demonstrated that children often develop moderate to severe problems and sleep disturbances at home during the first 3 days after surgery after adenotonsillectomy. Preoperative problems and need to know information were associated with increased pain at home. These researchers suggested that screening for these problems can help identify vulnerable children and prepare them by providing appropriate information, programs, and non-pharmacological treatments [43].

Conclusion

Play therapy and storytelling play an effective role in controlling the anxiety of hospitalized children; however, play therapy played a greater role than storytelling in reducing the anxiety of hospitalized children. Therefore, it is suggested to provide the necessary conditions and facilities for the implementation of these methods in children’s inpatient wards.

Practice implications

The findings from this study have important implications for clinical practice, particularly in the treatment of childhood anxiety. Storytelling therapy was found to significantly reduce anxiety levels in children, especially in younger age groups (3–8 years), making it a potentially valuable therapeutic intervention for children experiencing anxiety. Play therapy, while also effective for younger children, showed negative effects in children aged 8–10, which warrants careful consideration of age appropriateness when using this method.

From a cost-effectiveness perspective, storytelling therapy may offer a low-cost, non-invasive approach to managing childhood anxiety. The materials required for storytelling interventions are minimal, which can make it a practical option for healthcare providers, especially in resource-limited settings. Additionally, the ease of implementation and the flexibility of storytelling (which can be adapted to a wide range of settings) may improve accessibility for families.

The study also identified that children with no prior history of hospitalization had lower anxiety levels, suggesting that targeting interventions toward children with more extensive medical histories may be particularly beneficial. Gender differences were observed, with boys showing lower anxiety scores than girls, which may have implications for tailoring interventions based on gender.

Furthermore, the age group of 3–8 years appears to be the most appropriate for both storytelling and play therapy. In contrast, children aged 8–10 may not benefit from storytelling to the same extent and may even experience increased anxiety with play therapy. These age differences underscore the importance of customizing therapeutic approaches according to developmental stages.

In summary, storytelling therapy is a promising, cost-effective option for reducing childhood anxiety, particularly in younger children and those without a history of hospitalization. However, clinicians should be mindful of the potential for age-related and gender-related differences in anxiety responses, and adjust treatment approaches accordingly. Further research could help to refine these findings and explore additional factors that may influence the effectiveness of these interventions.

Limitations

This study focused on assessing anxiety levels in hospitalized children, but it did not examine other aspects of psychological distress, such as depression, fear, or post-traumatic stress, which may also affect children during hospitalization. Future research could expand the scope to include a more comprehensive evaluation of various psychological responses to hospitalization, providing a broader understanding of the emotional challenges faced by pediatric patients.

Additionally, the children’s psychological responses in this study may have been influenced by the specific environment and organizational structure of the hospital and the inpatient ward. These factors could limit the generalizability of the findings to other hospitals with different facilities or settings. Further studies could explore whether the outcomes of play therapy and storytelling interventions vary across different hospital environments, helping to assess the broader applicability of these approaches in diverse settings.

Another limitation was the constraint of space for implementing the interventions, which may have impacted the effectiveness of the sessions. Future research could consider addressing these spatial limitations by using larger, more adaptable spaces for interventions, or by exploring alternative delivery methods (e.g., digital platforms or mobile interventions) that can be more flexible in terms of space and availability.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely acknowledge Alborz University of Medical Sciences.

Author contributions

FA, MAJ conceived, designed, and wrote the paper the experiments, ML, FGH, NSH performed the experiments. AAN, EA contributed data. AK analyzed and interpreted the data.

Funding

The current study did not receive any funding support.

Data availability

All data analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This article approved by ethics committee of Alborz University of Medical Sciences (ID: IR.ABZUMS.REC.1401.084). As well, informed consent to participate was obtained from all of the parents of the participants in the study.

Consent to publish

Not applicable. The manuscript does not contain data from any individual person.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Juwita H. Effectiveness of multimodal interventions play therapy: colouring and origami against anxiety levels in toddler ages. J Health Sci Prev. 2019;3(3S):46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armandpishe S, Pakzad R, Jandaghian-Bidgoli M, Abdi F, Sardashti M, Soltaniha K. Investigating factors affecting the prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression among citizens of Karaj city: A population-based cross-sectional study. Heliyon. 2023;9(2023):e16901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Salsabila P, Anggraini IR, Alifatin A, Aini N. Play therapy to reduce anxiety in children during hospitalization: a literature review. KnE Med. 2022:765–73.

- 4.Bryan MA, Mihalek AJ. Gaps in Immunizing Children during hospitalization: how can we close them? Hosp Pediatr. 2024;14(9):e391–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zarra-Nezhad M, Pakdaman F, Moazami-Goodarzi A. The effectiveness of child-centered group play therapy and narrative therapy on preschoolers’ separation anxiety disorder and social-emotional behaviours. Early Child Dev Care. 2023;193(6):841–53. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azevêdo AVS, Lançoni AC, Crepaldi MA. Nursing team, family and hospitalized child interaction: an integrative review. Ciencia Saude Coletiva. 2017;22:3653–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doupnik SK, Hill D, Palakshappa D, Worsley D, Bae H, Shaik A et al. Parent coping support interventions during acute pediatric hospitalizations: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Pragholapati A, Septiani DD, Sudiyat R. Parent anxiety levels in hospitalization children in RSUD Majalaya Kab. Bandung Health Media. 2020;1(2):40–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang Y, Li S, Ma L, Zheng Y, Li Y. The effects of mother-father relationships on children’s social-emotional competence: the chain mediating model of parental emotional expression and parent-child attachment. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2023;155:107227. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grandjean C, Ullmann P, Marston M, Maitre M-C, Perez M-H, Ramelet A-S et al. Sources of stress, Family Functioning, and needs of families with a chronic critically ill child: a qualitative study. Front Pead. 2021;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Demirbağ S, Ergin D. A voice of children: I would like a hospital just for children’ - children’s perspectives on hospitalization: a phenomenological study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2024;77:e125–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delvecchio E, Salcuni S, Lis A, Germani A, Di Riso D. Hospitalized children: anxiety, coping strategies, and pretend play. Front Public Health. 2019;7:250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheehan J, Laver K, Bhopti A, Rahja M, Usherwood T, Clemson L, et al. Methods and Effectiveness of Communication between Hospital Allied Health and Primary Care Practitioners: a systematic narrative review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:493–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Signorelli C, Robertson EG, Valentin C, Alchin JE, Treadgold C. A review of Creative Play interventions to improve children’s hospital experience and wellbeing. Hosp Pediatr. 2023;13(11):e355–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godino-Iáñez MJ, Martos-Cabrera MB, Suleiman-Martos N, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Vargas-Román K, Membrive-Jiménez MJ, et al. editors. Play therapy as an intervention in hospitalized children: a systematic review. Healthcare: Mdpi; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godino-Iáñez MJ, Martos-Cabrera MB, Suleiman-Martos N, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Vargas-Román K, Membrive-Jiménez MJ et al. Play Therapy as an Intervention in Hospitalized Children: A Systematic Review. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). 2020;8(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Burns-Nader ES. The effects of medical play on reducing fear, anxiety, and procedure distress in school-aged children going to visit the doctor. The University of Alabama; 2011.

- 18.Sekhavatpour Z, Khanjani N, Reyhani T, Ghaffari S, Dastoorpoor M. The effect of storytelling on anxiety and behavioral disorders in children undergoing surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Health Med Ther. 2019;10:61–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bally JMG, Burles M, Spurr S, McGrath J. Exploring the Use of Arts-Based Interventions and Research Methods in families of seriously Ill children: a scoping review. J Fam Nurs. 2023;29(4):395–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramamurthy C, Zuo P, Armstrong G, Andriessen K. The impact of storytelling on building resilience in children: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2024;31(4):525–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zamani M, Sigaroudi AE, Pouralizadeh M, Kazemnejad-Leili E. Effect of the Digital Education Package (DEP) on prevention of anxiety in hospitalized children: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Nurs. 2022;21(1):324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samanta S, Bandyopadhyay A, Mukherjee A, Bhattacherjee S. Appropriateness of hospital admission and length of stay in the Pediatric Department of a Tertiary Care Hospital in West Bengal. Indian J Community Medicine: Official Publication Indian Association Prev Social Med. 2023;48(6):841–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davidson B, Satchi NS, Venkatesan L. Effectiveness of play therapy upon anxiety among hospitalised children. Int J Adv Res Ideas Innovations Technol. 2017;3(5):441–4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spence SH, Barrett PM, Turner CM. Psychometric properties of the Spence Children’s anxiety scale with young adolescents. J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17(6):605–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zarghami F, Heidarinasab L, Shairi MR, Shahrivar Z. The effectiveness of cognitive behavior treatment based on Kendall’s coping program on anxiety disorders: a Transdiagnostic Approach. Clin Psychol Stud. 2015;5(19):183–202. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shahrabadi H, Talebi S, Ganjloo J, Nekah S, Talebi S. Comparison of the effectiveness of educative story books and face-to-face education on anxiety of hospitalized children. Iran J Psychiatric Nurs. 2016;4(3):58–64. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ajorloo M, Irani Z, Aliakbari Dehkordi M. Story therapy effect on reducing anxiety and improvement habits sleep in children with cancer under chemotherapy. Health Psychol. 2016;5(18):87–107. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper K, Hatfield E, Yeomans J. Animated stories of medical error as a means of teaching undergraduates patient safety: an evaluation study. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8:118–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Khotani A, Bello LAa, Christidis N. Effects of audiovisual distraction on children’s behaviour during dental treatment: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Acta Odontol Scand. 2016;74(6):494–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dewi MM, Nurhaeni N, Hayati H. The effect of storytelling on fear in school-age children during hospitalization. La Pediatria Med E Chirurgica: Med Surg Pediatr. 2021;43:s1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zengin M, Yayan EH, Düken ME. The effects of a therapeutic play/play therapy program on the fear and anxiety levels of hospitalized children after liver transplantation. J PeriAnesthesia Nurs. 2021;36(1):81–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silva SGTd, Santos MA, Floriano CMF, Damião EBC, Campos FVd, Rossato LM. Influence of therapeutic play on the anxiety of hospitalized school-age children: clinical trial. Revista brasileira de enfermagem. 2017;70:1244–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li WH, Chung JOK, Ho KY, Kwok BMC. Play interventions to reduce anxiety and negative emotions in hospitalized children. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yati M, Wahyuni S, Islaeli I. The effect of storytelling in a play therapy on anxiety level in pre-school children during hospitalization in the general hospital of buton. Public Health Indonesia. 2017;3(3):96–101. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghasemzadeh S. Effectiveness of child-centered play therapy on resiliency of children with leukemia cancer. J Pediatr Nurs. 2022;8(3):47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramdaniati S, Hermaningsih S. Comparison study of art therapy and play therapy in reducing anxiety on pre-school children who experience hospitalization. Open J Nurs. 2016;6(01):46. [Google Scholar]

- 37.AlaeiFard N, Ahadi H, Mehrvarz A, Jomehri F, Doulatabadi S. Comparison of the effectiveness of play therapy and story therapy on depression and anxiety separation in children with leukemia. Med J Mashhad Univ Med Sci. 2021;64(4):3796–808. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Senko K, Bethany H. PLAY THERAPY: an illustrative case. Innovations Clin Neurosci. 2019;16(5–6):38–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asli Azad M, Arefi M, Farhadi T, Mohammadi S, Ruh A. The effectiveness of child-centered play therapy on anxiety and depression in children girl with anxiety disorder and depression in primary school. Psychol Methods Models. 2012;3(9):71–90. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dalei SR, Nayak GR, Pradhan R. Effect of art therapy and play therapy on anxiety among hospitalized preschool children. J Biomedical Sci. 2020;7(2):71–6. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ibrahim HA, Amal AA. The effectiveness of Play Therapy in Hospitalized Children with Cancer: systematic review. J Nurs Pract. 2020;3(2):233–43. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al-Yateem N, Rossiter RC. Unstructured play for anxiety in pediatric inpatient care. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2017;22(1):e12166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berghmans JM, Poley MJ, van der Ende J, Veyckemans F, Poels S, Weber F, et al. Association between children’s emotional/behavioral problems before adenotonsillectomy and postoperative pain scores at home. Pediatr Anesth. 2018;28(9):803–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data analysed during this study are included in this published article.