Abstract

Background

The accelerated advancement of information technology and artificial intelligence in the modern globalized world has necessitated a high level of technology competence from translators to adapt to the increasing needs of clients and the language industry. Prior research indicated that emotional intelligence, self-esteem, and innovation capability independently affected students’ translation competence. However, no research has investigated how these psychological factors influence student translators’ proficiency in translation technology.

Methods

This research engaged 663 senior EFL students through an online questionnaire to investigate the systematic associations among the identified variables. Descriptive statistics, structural equation modeling, and the bootstrap method were adopted to analyze the collected data.

Results

The results showed that students’ translation technology competence (TTC) was significantly influenced by emotional intelligence, self-esteem, and innovation capability. Furthermore, self-esteem and innovation capability were independent and sequential mediators in the connection between emotional intelligence and TTC of college EFL students.

Conclusions

This study provides theoretical and practical insights for designing curricula and interventions to enhance TTC by integrating psychological and pedagogical strategies. By emphasizing emotional intelligence, fostering self-esteem, and cultivating innovation capability, educators and institutions can prepare students to meet the demands of the technology-driven language service market.

Keywords: Self-esteem, Innovation capability, Emotional intelligence, Translation technology competence, Student translator

Introduction

In today’s interconnected world, translation services are critical for effective communication across diverse linguistic backgrounds [1]. Traditional approaches can be time-consuming and costly [2], which may limit access to language services. Meanwhile, rapid advances in computer science, information technology, and artificial intelligence have given rise to more sophisticated translation tools, substantially enhancing translation performance and reshaping the industry [3, 4]. Despite these technological advances, few empirical studies have comprehensively explored the multifaceted psychological processes that underlie student translators’ competence in using these emerging tools. This is particularly critical in light of the growing market demand for translators who are adept at utilizing translation technology, making research into psychological factors a key step in developing well-rounded, technologically competent graduates.

Universities are facing growing pressure to produce technology-savvy graduates capable of meeting the demands of a technology-driven language service market [5]. In response to this need, many bachelor’s programs now include both traditional translation methods and technology-driven approaches within their compulsory courses, particularly for senior EFL students. These students typically receive formal training in various translation tasks, including those relying on translation technology, to prepare them for future employment where translation is either a core or auxiliary responsibility. It is therefore essential for translation students to stay informed about the latest developments in translation technology and leverage them for their benefit [6]. Moreover, although translator training programs have expanded globally, the applicability of research findings may vary based on cultural, linguistic, and educational contexts. This study primarily focuses on senior EFL students in China, a context where English-language proficiency and exposure to translation technology are rapidly expanding. However, given the overarching shifts toward automation and digital solutions worldwide, the insights gained here hold potential relevance for a broader international audience seeking to cultivate translation technology competence (TTC) in higher education.

The interplay between psychology and translation has long been recognized in the field of translation studies, underscoring the translator’s cognitive and affective processes when rendering texts in another language [7, 8]. This perspective encompasses a range of factors, including emotional states, cognitive mechanisms, and individual traits, that can shape translation performance [9]. Previous investigations confirmed that translators’ psychology can positively influence their overall translation competence [10–12]. Yet, there remains an evident gap in the literature regarding how these psychological attributes specifically affect TTC, which is increasingly regarded as a cornerstone of modern translator training [13]. Understanding these underlying processes is essential for developing targeted, context-specific interventions to enhance TTC both locally and globally.

Recent empirical studies have offered insights into the isolated impacts of emotional intelligence, self-esteem, and innovation capability on translation outcomes [14–16]. Translators high in emotional intelligence demonstrate resilience and adaptability, thereby enhancing their capacity to manage the complexities and pressures involved in both traditional translation tasks and technology-mediated workflows [17, 18]. Moreover, self-esteem is a crucial factor in driving learners’ motivation, autonomy, and decision-making capabilities, enabling them to overcome challenges in translation training and technology use more effectively [19–21]. Simultaneously, innovation capability encourages student translators to explore emerging translation tools and adopt novel strategies, promoting a willingness to experiment and take risks [22, 23]. Despite these promising findings, most investigations examine these psychological factors individually rather than holistically, leaving unexplored the fundamental mechanisms through which emotional intelligence, self-esteem, and innovation capability collectively shape TTC.

To address the gaps, the present study seeks to investigate how these interrelated psychological factors directly and indirectly influence students’ TTC. Specifically, we propose a model in which self-esteem and innovation capability function as sequential mediators in the relationship between emotional intelligence and TTC. Our sample comprises 663 senior EFL students in China, a context experiencing rapid expansion in higher education enrollment and a growing emphasis on producing graduates with robust TTC to meet local and international market needs. Given that senior EFL students are approaching graduation and will soon enter the workforce, their development of both traditional and technology-driven translation skills is especially critical for employability and professional success. By adopting an integrated perspective, this study aims to shed light on the pathways through which pivotal psychological attributes foster the acquisition of technology-related competencies among translation students. In particular, our findings offer practical insights that are expected to benefit multiple stakeholders: translation educators who can incorporate targeted psychological interventions into curricula, technology developers who can design and refine user-centric translation tools that accommodate learners’ psychological needs, and students themselves who gain a clearer understanding of how their psychological traits facilitate TTC.

Literature review and hypothesis development

TTC

The current research adopts the framework for TTC developed by Li et al. [13], which is composed of the following attributes: (1) Machine translation. A translator’s technological competence has traditionally been connected with machine translation [24]. Translation professionals have been able to increase their productivity across various language service sectors [25] and enhance translation quality [26] through the incorporation of machine translation into the translation workflow. (2) Post-editing. The increasing acceptance of machine translation by suppliers and customers of translation services has enabled post-editing machine-generated results to become a lucrative business opportunity for translation companies [27]. Post-editing after machine translation is the most reliable method to guarantee that the text adheres to the client’s specifications and retains its original message and style [28]. (3) Information literacy. It is widely recognized that the capacity to identify and make use of information is a key component of multiple translation models, for instance, the PACTE Model [29, 30] and the EMT translation competence framework [31]. Information literacy plays an important role in helping translators to comprehend and reproduce source texts through the acquisition of knowledge and information, and it is a fundamental tool for translators to make decisions and resolve issues encountered in translation tasks [32, 33]. (4) Terminology management. Translation terminology management entails recognizing, extracting, storing, applying, and regularly updating terms in translation projects [34]. The selection of appropriate terms and their pertinence to the specific domain are essential for guaranteeing successful translation [35]. (5) Translation memory. Translation memory is a tool that archives segments of text in the source and target languages in a database, allowing translators to quickly detect and reuse previously-translated segments in a new document [36, 37]. It has become widespread in recent years for boosting efficiency and accuracy in translation processes, as it enables users to build on existing work and guarantee consistency in different projects [38, 39]. (6) Computer-aided translation (CAT). In response to the growing complexity and specialization of translation tasks, translators have to adopt CAT platforms to complete jobs quickly and effectively [40, 41], keep up with the demands of their work [42] and meet customer needs [43]. The majority of translators in large translation companies have implemented CAT tools in their work, as these tools provide a productive environment for the efficient organization and execution of translation tasks [44].

Emotional intelligence and TTC

Emotional intelligence is characterized as the capacity to recognize, understand, and respond to the emotions of oneself and those around him/her, utilizing that understanding to guide one’s thinking and behavior [45]. It involves the capacity to detect, express, use, and cope with one’s feelings effectively. Having high emotional intelligence lays a solid foundation to build upon a wide range of capabilities that can enable people to achieve better results. Those who possess an aptitude for effectively managing their emotions may be more likely to acquire additional professional expertise [46]. The translation process is known to be heavily influenced by emotions, with both positive and negative feelings leading to distinct processing approaches [47]. Translators possessing higher emotional intelligence have greater chances to accurately transmit the implied message from one language to another due to their heightened awareness of linguistic and non-linguistic details and their ability to replicate those aspects in the target language [48]. Individuals with a greater capacity for emotional intelligence are particularly adept at understanding the emotional content of texts [49]. For example, a multiple regression analysis of 54 Iranian postgraduates in Translation Studies revealed that emotional intelligence was a major contributor to the translation performance of the participants [50]. A survey of 248 college translation students found that emotional intelligence was a critical factor in predicting how well students would do during training exercises for simultaneous interpreting [14]. However, an investigation of 100 professional translators with 2–7 years of experience indicated no correlation between their emotional intelligence and the quality of their translations [51]. Hence, Hypothesis 1 was proposed:

H1: Student translators’ emotional intelligence positively affects their TTC.

Self-esteem and TTC

An individual’s self-esteem is the evaluation they hold of themselves in terms of their worthiness and acceptance [52]. Strong self-esteem is a valuable asset for psychological well-being, shielding individuals from mental distress and difficult life events [53]. Those with strong self-esteem tend to have loftier ambitions and are more likely to remain steadfast when confronted with failure, as well as possessing the courage to tackle complex issues [54]. The translator’s sense of accomplishment regarding their work is heavily influenced by personality traits closely associated with self-esteem [55, 56]. The use of collaborative learning in a translation course provided a boost of self-esteem to the students, which in turn improved their translation competence when the group was able to tackle translation issues and create successful translations [57]. A study conducted on 33 Spanish translation trainees showed that those with greater self-esteem experienced lower levels of anxiety during and after their training, indicating that it may provide a buffer against stress [15]. In terms of TTC, self-esteem had an influence on information literacy and related information activities, according to an empirical study on 5,842 adult consumers [20]. However, the results of 45 freshman participants completing three translation tasks during a semester showed that student translators with high self-esteem did not demonstrate superior performance compared to those with low self-esteem [58]. Thus, this study put forward Hypothesis 2 to test whether self-esteem impacts TTC:

H2: Student translators’ self-esteem positively affects their TTC.

Innovation capability and TTC

Innovation capability encompasses a range of skills and competencies that facilitate the completion of the innovation process and the achievement of successful outcomes through the effective acquisition and application of knowledge. An innovative mindset can boost students’ confidence in their translation technology skills by encouraging them to take risks and make decisions with limited information. The implementation of the Internet and translation technology has revolutionized the language service industry, fueling growth and providing new opportunities for innovation in the sector [59]. Translation businesses will have to adjust their profit models and operation patterns due to the advances in translation-related technologies, such as machine translation, online crowdsourcing [60], and the application of large language models [61], which require higher levels of innovation capability from translation professionals. Students majoring in English should develop creative skills to enhance their translation competence [23], as translators can exercise similar levels of innovation and hold ultimate authority in making translation decisions [62]. Taking these arguments into consideration, Hypothesis 3 was proposed:

H3: Student translators’ innovation capability positively affects their TTC.

Emotional intelligence and self-esteem

Emotional intelligence is connected with an individual’s capacity to recognize, evaluate, and manage the emotions of oneself and others [63], while an individual’s self-esteem is a reflection of how they feel about themselves and can be impacted by a range of elements such as intelligence and capability [64]. Emotional intelligence had a profound effect on self-esteem with those displaying a higher emotional intelligence exhibiting a higher degree of self-esteem [65, 66]. Emotionally intelligent people tend to possess increased self-esteem due to their adeptness in managing their emotions [67], allowing them to stay in a positive mental state. They were more resilient in unfavorable circumstances and were able to better maintain their self-esteem [68]. Having a positive attitude and the capability to recognize and manage emotions can be a strong indicator of good mental health and a strong sense of self-worth [69], thus leading to a higher aptitude for managing interpersonal relationships and moderating negative emotions [70]. Higher emotional intelligence was also linked to greater self-esteem because emotional skills can help individuals handle the pressures of new commitments and stressful life events more effectively [71]. As a result, Hypothesis 4 was put forward:

H4: Student translators’ emotional intelligence positively affects their self-esteem.

Self-esteem and innovation capability

People with strong self-esteem generally think of themselves as competent and deserving. Thus, they tend to articulate perspectives that contrast with those of others and are more open to giving out innovative concepts [72]. Individuals with higher self-esteem may approach translation challenges more innovatively than those with lower self-esteem, as greater self-esteem often drives individuals to pursue ambitious goals [58]. Strong self-esteem can also help to protect people from feeling overwhelmed by the pressure of a challenging situation; therefore, they are less likely to experience a decline in creativity due to the stress of being judged [73]. For example, an empirical investigation of 732 Chinese undergraduates revealed that self-esteem and innovation correlated significantly and positively, and self-esteem mediated the correlation between the Big Five personality traits and undergraduates’ creativity [74]. An experiment involving 336 participants suggested a strong relationship between trait creativity and self-esteem, indicating that individuals with low self-esteem may be more reactive to momentary inputs, whereas those with high self-esteem tend to focus on specific stimulus features [75]. Therefore, Hypothesis 5 was proposed:

H5: Student translators’ self-esteem positively affects their innovation capability.

Emotional intelligence and innovation capability

Emotional intelligence was identified to positively affect creativity in previous studies [76, 77]. Individuals may be motivated by their emotional capabilities to identify opportunities, set ambitious objectives, and devise strategies to conquer potential obstacles [78]. The capability to regulate and express emotions is a contributing factor in predicting successful creative performance under frustration, as emotional intelligence facilitates the use of emotional resources that are essential to creative thought [79]. Emotionally intelligent individuals can identify issues more effectively, ward off negative feelings, and increase their internal motivation to tackle problems, resulting in improved creative productivity [80]. Those who lack emotional intelligence are often overwhelmed by unexpected occurrences and struggle to maintain a positive outlook, whereas those with higher emotional intelligence are capable of converting negative emotions into constructive ideas, which can lead to more creative and adaptive thinking [81]. Emotional experiences not only enhance the thinking process but also foster diverse perspectives on specific topics, which can lead to creative ideas [82], and research by Othman and Muda [83] further suggests that students’ emotional intelligence is correlated with innovative attitudes that may inspire the generation of novel ideas. A notable connection was observed between emotional intelligence and creative performance in knowledge-intensive workplaces where innovation, motivation, and persistence are valued [84]. Employees who possess the capacity to manage their emotions can remain in a more positive state when presented with difficult tasks while being able to access and draw on positive emotions can help boost their creative thinking [85]. Nevertheless, research into the relationship between emotional intelligence and creativity has yielded inconsistent findings. For example, the questionnaire survey of 241 Spanish executives showed that emotional intelligence did not significantly affect innovation [86]. Thus, Hypothesis 6 was proposed to examine the relation in this context:

H6: Student translators’ emotional intelligence positively affects their innovation capability.

Mediating effect

Self-esteem also plays a role in the relationship between emotional intelligence and TTC. Developing emotional intelligence is essential for building self-esteem in student translators [66], as it entails recognizing and controlling emotions both within oneself and in interactions with others [45], which contributes to a sense of personal value. Emotional intelligence can also help to build a student translator’s self-esteem by equipping them with tools to effectively manage stress, such as learning to recognize and accept their emotions and finding healthier ways to manage their pressure [87]. When student translators are able to manage their stress levels, they are more likely to feel increased self-esteem and confidence in their abilities as translators. Meanwhile, self-esteem is a crucial factor that can influence an individual’s performance in translation technology, as individuals with greater self-esteem are more willing to take risks [21] when learning and using the technology. Students with higher self-esteem are more likely to possess strong problem-solving skills [88], enabling them to identify efficient solutions for translation tasks. In short, higher emotional intelligence correlated with greater self-esteem, which in turn was related to higher TTC. This indicates self-esteem may mediate the relationship between emotional intelligence and TTC. To examine that assumption, Hypothesis 7a was proposed:

H7a: Student translators’ self-esteem mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence and TTC.

Emotional intelligence has been widely recognized as an important factor in enhancing creativity [77, 84], which enables translators to understand the impact of emotions on using translation technology effectively. It can play a critical role in the innovation capability of translators to manage the complex and sometimes conflicting demands of translation technology, enabling them to come up with creative solutions to problems [14]. Emotionally intelligent student translators can better regulate their own emotions, and those of others [89], which can lead to a more effective process of decision-making and creative problem-solving. By having a better comprehension of others’ emotions, student translators can evaluate new concepts objectively and respond to potential opportunities for innovation. At the same time, creativity entails the generation of novel ideas, products, or solutions to existing problems [90], and it directly impacts the successful application of translation technology. The engagement in creative activities enables translators to identify and implement innovative solutions to their translation technology tasks. Innovation capability can also help translators develop their TTC by allowing them to experiment with new methods, tools, and techniques [91]. In conclusion, emotional intelligence positively affects innovation capability, and innovation capability has a significant impact on TTC. It seems that innovation capability may serve as an intermediary in the relationship between emotional intelligence and TTC. Hence, Hypothesis 7b was put forward:

H7b: Student translators’ innovation capability mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence and TTC.

Sequential mediating effect

As discussed in previous sections, emotional intelligence enhances individuals’ ability to manage emotions, fostering a positive mental state and resilience [68, 71], which contributes to higher self-esteem [65]. Self-esteem, in turn, strengthens innovation capability by promoting confidence and openness to new ideas, as well as a willingness to take risks in problem-solving [72, 74]. Emotionally intelligent individuals, equipped with tools to manage stress and recognize their value, are better positioned to develop strong self-esteem, which subsequently boosts creativity and innovation in translation tasks [66, 77]. Furthermore, innovation capability is pivotal for effectively engaging with translation technology, as it empowers translators to experiment with tools and implement creative solutions [14, 91]. This indicates that self-esteem and innovation capability may play a sequential intermediary role in the relationship between emotional intelligence and TTC. As a result, Hypothesis 8 was proposed to test such prediction:

H8: Student translators’ self-esteem and innovation capability sequentially mediated the relationship between emotional intelligence and TTC.

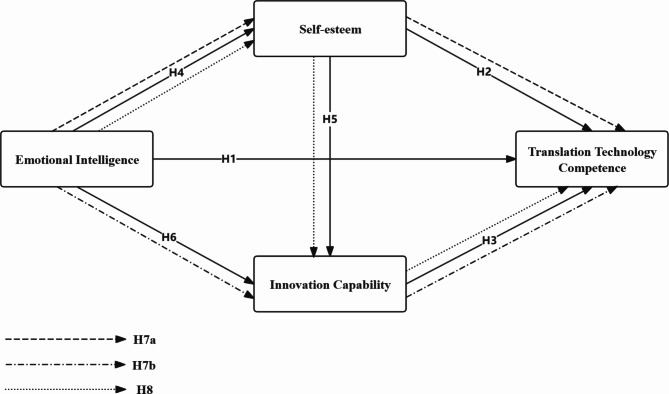

Figure 1 presents an overview of the research model.

Fig. 1.

Research model

This research makes a novel contribution by integrating emotional intelligence, self-esteem, and innovation capability into a single, comprehensive framework to examine their collective impact on student translators’ TTC. While prior studies have highlighted the isolated roles of emotional intelligence [17, 18], self-esteem [19, 20], and innovation [22, 23] in translation training, few have explored how these psychological variables function together in shaping students’ proficiency with emerging translation tools [13]. By testing sequential mediation pathways, this study illuminates the interconnected processes through which emotional intelligence cultivates higher self-esteem, which subsequently reinforces innovation capability, culminating in more robust TTC. This novel approach highlights the interplay between emotional-cognitive traits and technical competence in a domain increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence and digital tools [18].

Moreover, unlike earlier studies that predominantly focused on student translators’ overall translation aptitude or linguistic competence, our research focuses specifically on TTC, a domain of growing significance in translator training and employability [5, 6, 61]. By theorizing and empirically validating a model in which self-esteem and innovation capability sequentially mediate the impact of emotional intelligence on TTC, we extend the scope of existing findings on how psychological resources can encourage learners to explore and master emerging translation tools, a pathway that had not been systematically investigated in existing translation studies [12, 13]. This emphasis on the specific subset of translation technology skills sheds light on a vital aspect of translator education, given the industry’s rapid shift toward automation and the integration of artificial intelligence [4].

By pinpointing self-esteem and innovation capability as distinct yet sequential mediators, the study not only clarifies the underlying mechanisms connecting emotional intelligence to TTC but also offers practical insights for curriculum design and instructional interventions. Unlike existing studies that highlight only one or two factors (e.g., emotional intelligence or creativity) at a time [14, 15, 61], our findings show that systematically strengthening students’ self-esteem and innovation capability, while also nurturing their emotional intelligence, can lead to demonstrable improvements in TTC. Educators, technology developers, and policymakers can utilize these insights to design evidence-based programs, assessment methods, and user-centric platforms that holistically support emerging translators in a rapidly evolving language service market.

Methods

Pilot test

In November 2022, a pilot study employing a convenience sampling approach was conducted at a public university in China, yielding 232 valid questionnaires. Harman single-factor test, Cronbach’s alpha, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were performed, which led to the removal of 5 items from the questionnaire. As opposed to 42 items initially, the final questionnaire had 37 items. Moreover, the pilot test resulted in the rewording of one item to make it more understandable. The pilot study and the subsequent formal survey were conducted together with another empirical research investigating critical thinking, academic self-efficacy, cultural intelligence, and TTC by our team.

Participants

This study received ethical approval from the institutional ethics committee in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Grant number: HRECA22-003). All participants provided informed consent prior to their participation in the study. As this research involved only questionnaire-based data collection from university students and did not involve any patients or medical procedures, no patient consent was required.

A total of 663 senior EFL students from seven Chinese public universities participated in this study voluntarily, collectively representing a substantial and diverse segment of prospective translators in China. To guarantee these participants possessed both relevant academic training and direct exposure to translation technology, only seniors were chosen for this study. In many Chinese universities, courses incorporating translation technology are commonly introduced in the third or fourth year, which aligns with industry expectations that translators master both traditional and technology-enhanced approaches. The majority of the participants were female (89%). Male students only accounted for 11%. 169 respondents were from urban families (25.5%), and 494 were from rural backgrounds (74.5%). 57.9% were specialized in English Language and Literature (n = 384), 31.5% in Translation (n = 209), and 10.6% in Business English (n = 70). All participants were on track to graduate with the competencies needed for translation-oriented careers, ranging from full-time translator or interpreter roles to positions in international business, thus reflecting the broader translator community’s need for diverse skill sets that merge linguistic expertise with emerging technologies.

The participants’ anonymity was preserved throughout the study, and they were informed about the study’s purpose before participation. All data were collected and stored in accordance with ethical research guidelines.

Measures

Emotional intelligence was assessed by the self-report Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS) [89] with 16 items. A variety of empirical studies have provided evidence for the reliability and validity of the scale [92–94]. However, two items were removed in the current study due to their poor factor loadings following CFA in the pilot test. The Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.955 in the final investigation. Self-esteem was evaluated by the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) [95]. A 1–4 scale is used, where higher scores indicate greater self-esteem. The Chinese version revealed satisfactory reliability and validity among university students [70, 96, 97], with a Cronbach’s Alpha at 0.932. Innovation capability was measured by the 10-item Innate Innovativeness Scale (IIS) developed by Salhieh and Al-Abdallat [98], which was adapted from prior studies by Goldsmith et al. [99] and Pallister & Foxall [100]. The instrument demonstrated strong internal reliability and validity in the original study. Nevertheless, the pilot study revealed that three items had to be excluded as their factor loadings were deemed too low, which led to a Cronbach’s Alpha at 0.904 in the present study. TTC of student translators was evaluated by the 6-item scale developed by Li et al. [13]. The Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.877 in the present investigation.

Procedure and data analysis

The final questionnaire was translated from English to Chinese by a professional translator with the Certificate of China Accreditation Test for Translators and Interpreters. It was then formulated on the online platform “Wenjuanxin”, a widely-used survey website in China. The teachers from the seven investigated Chinese universities helped distribute the electronic questionnaire to their senior students. The questionnaire was completed by participants through a convenience sampling method from November 29th, 2022, to December 13th, 2022. Data analysis was performed using multiple statistical software packages: descriptive statistics were computed through SPSS 27.0, structural equation modeling (SEM) was executed in Amos 24.0, and bootstrapping procedures were implemented via PROCESS macro 3.5.

Results

Common method deviation test

The Harman single-factor test is the most commonly applied approach for assessing common method bias [101, 102]. A variance of less than 50% for a single factor indicates that common method bias is not present [103]. The first factor contributed 35.335% of the total variance extracted by the principal components analysis in the current study. As a result, this research does not appear to have major common method bias issues.

Validity and reliability

An item is considered significant to the related construct if its standardized factor loading exceeds 0.5 [104]. Table 1 shows the factor loadings of all items in the scale vary from 0.577 to 0.946, suggesting a robust correlation between each item and their latent variable.

Table 1.

Factor loadings of the items

| Item | Factor Loading | Item | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| EI1 | 0.686 | SE1 | 0.707 |

| EI2 | 0.846 | SE2 | 0.681 |

| EI3 | 0.928 | SE3 | 0.827 |

| EI4 | 0.823 | SE4 | 0.762 |

| EI5 | 0.863 | SE5 | 0.845 |

| EI6 | 0.669 | SE6 | 0.697 |

| EI7 | 0.749 | SE7 | 0.806 |

| EI8 | 0.605 | SE8 | 0.65 |

| EI9 | 0.577 | SE9 | 0.875 |

| EI10 | 0.919 | SE10 | 0.791 |

| EI11 | 0.946 | ||

| EI12 | 0.837 | ||

| EI13 | 0.661 | ||

| EI14 | 0.902 | ||

| Item | Factor Loading | Item | Factor Loading |

| IC1 | 0.679 | TTC1 | 0.712 |

| IC2 | 0.597 | TTC2 | 0.672 |

| IC3 | 0.726 | TTC3 | 0.75 |

| IC4 | 0.92 | TTC4 | 0.909 |

| IC5 | 0.753 | TTC5 | 0.646 |

| IC6 | 0.784 | TTC6 | 0.753 |

| IC7 | 0.859 |

EI = emotional intelligence, SE = self-esteem, IC = innovation capability, TTC = translation technology competence

The Cronbach’s alpha for the overall scale in the current research is 0.943. Table 2 shows Cronbach’s α coefficients of the subscales were within the range of 0.877 to 0.955, indicating that the scales have good reliability [105]. The construct validity was assessed by examining convergent and discriminant validity. AVE and CR were adopted to test convergent validity, which was deemed satisfactory if the AVE was higher than 0.50, the CR was above 0.70, and the CR was greater than the AVE [106, 107]. There was good convergent validity on the scale in the present study, with all variables’ AVEs and CRs exceeding 0.5 and 0.7 correspondingly. It demonstrates good discriminant validity of the scale when there are greater square roots of AVE values than correlations between constructs [104]. Table 3 shows the correlation coefficients between the constructs are less than the square roots of the AVE of all variables, indicating a favorable discriminant validity of the present scale.

Table 2.

Reliability and convergent validity results

| Variable | Mean | S.D. | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.EI | 3.926 | 0.546 | 0.955 | 0.959 | 0.633 | 1 | |||

| 2.SE | 2.961 | 0.515 | 0.932 | 0.934 | 0.589 | 0.576** | 1 | ||

| 3.IC | 3.306 | 0.670 | 0.904 | 0.907 | 0.587 | 0.611** | 0.594** | 1 | |

| 4.TTC | 4.315 | 0.475 | 0.877 | 0.881 | 0.555 | 0.367** | 0.350** | 0.365** | 1 |

** p < 0.01

Table 3.

Discriminant validity analysis

| Items | CT | ASE | CI | TTC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI | 0.796 | |||

| SE | 0.440*** | 0.768 | ||

| IC | 0.293*** | 0.442*** | 0.766 | |

| TTC | 0.305*** | 0.280*** | 0.236*** | 0.745 |

*** p < 0.001

Model estimates

Direct effect on TTC

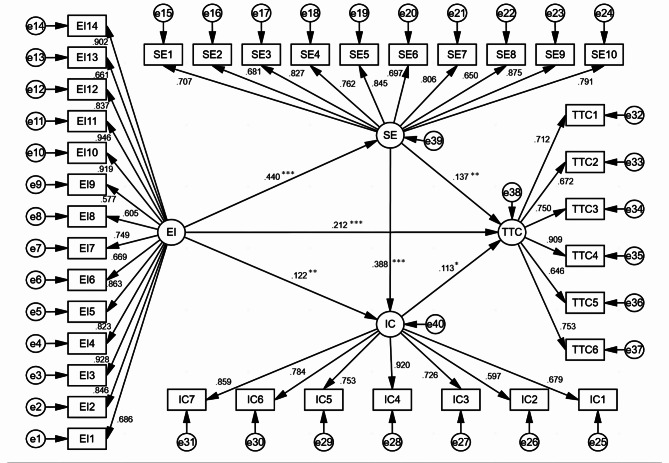

Fitting index results showed that there was a good fit between the data and the proposed research model (χ2/df = 2.735, SRMR = 0.0467, RMSEA = 0.051, GFI = 0.871, NFI = 0.911, IFI = 0.942, TLI = 0.938, CFI = 0.942) [108]. The results of SEM are presented in Fig. 2. Table 4 summarizes the test results of the hypotheses that were proposed to examine the direct impact of emotional intelligence, self-esteem, and innovation capability on TTC. The path coefficient of EI to TTC was 0.212 (p < 0.001), SE to TTC 0.137 (p < 0.01), IC to TTC 0.113 (p < 0.05), EI to SE 0.440 (p < 0.001), SE to IC 0.388 (p < 0.001), and EI to IC 0.122 (p < 0.01). Therefore, Hypotheses 1–6 were all confirmed. Students’ TTC is positively influenced by their emotional intelligence, self-esteem, and innovation capability.

Fig. 2.

Result of SEM

*** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05

Table 4.

Results of direct effects

| Hypothesis | Path | β | S.E. | C.R. | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | TTC←EI | 0.212 | 0.037 | 4.64 | *** |

| H2 | TTC←SE | 0.137 | 0.048 | 2.81 | ** |

| H3 | TTC←IC | 0.113 | 0.032 | 2.47 | * |

| H4 | SE←EI | 0.440 | 0.036 | 9.909 | *** |

| H5 | IC←SE | 0.388 | 0.066 | 8.147 | *** |

| H6 | IC←EI | 0.122 | 0.048 | 2.897 | ** |

*** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05

Mediation of self-esteem and innovation capability

In this research, IBM SPSS macro PROCESS 3.5 by Hayes [109] was used to investigate whether self-esteem and innovation capability mediate the connection between emotional intelligence and TTC among student translators. In Model 6, a Bootstrap CI method consisting of 5,000 bootstrap samples at a bias-corrected confidence interval of 95% was selected.

Table 5 shows the total indirect effect of self-esteem and innovation capability on the correlation between emotional intelligence and students’ TTC was 0.081 (BootLLCI = 0.045, BootULCI = 0.121). The indirect effect of self-esteem on the relation between emotional intelligence and TTC was 0.051 (BootLLCI = 0.015, BootULCI = 0.091). Thus, H7a was supported [110]. Emotional intelligence had an effect on students’ TTC through self-esteem. The indirect impact of innovation capability on the effect of emotional intelligence on TTC was 0.013 (BootLLCI = 0.003, BootULCI = 0.029). Hence, H7b was supported. Innovation capability mediated the association between emotional intelligence and TTC. The sequential indirect effect of self-esteem and innovation capability on the link between emotional intelligence and TTC was 0.016 (BootLLCI = 0.005, BootULCI = 0.033). Thus, H8 was verified in this study. Self-esteem and innovation capability served as sequential mediators in the relationship between emotional intelligence and TTC of EFL students.

Table 5.

Results of indirect effects

| Hypothesis | Path | Indirect effect | Boot SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | Effect of the amount |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total indirect effect | 0.081 | 0.019 | 0.045 | 0.121 | 30.57% | |

| H7a | EI-SE-TTC | 0.051 | 0.019 | 0.015 | 0.091 | 19.25% |

| H7b | EI-IC-TTC | 0.013 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.029 | 4.91% |

| H8 | CT-SE-IC-TTC | 0.016 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.033 | 6.04% |

Discussion

Direct relationships

The findings indicated that emotional intelligence has a significant play in improving students’ TTC. Emotional intelligence is a powerful tool that has been shown to improve students’ success in developing a clear understanding of their own emotions, recognizing and understanding the emotions of others, and managing their stress to remain focused on the task [111]. It can help student translators understand the process of problem-solving and tackle the complex challenges they may encounter while working with translation technology [112]. This is especially important in today’s increasingly technology-driven world, as mastering new technology can be a difficult and stressful process. Students with greater emotional intelligence tend to consider multiple perspectives and approach problems from different angles in order to come up with the most effective solutions [113]. It also allows student translators to recognize how their emotions are influencing their translation work, and to make adjustments to ensure the result is accurate and up to standard. Further, emotional intelligence helps students effectively communicate and interact with others in understanding and using the translation technology, enabling them to take full advantage of the educational opportunities to improve their technology competences [114]. By working together, students are able to benefit from each other’s knowledge and skills to attain better application of the technology and put forward innovative solutions to problems that may arise in the use of translation technology.

Self-esteem is an important factor that has a significant influence on TTC among student translators, as having a positive attitude and belief in one’s capabilities can significantly enhance performance [115]. Higher self-esteem leads to greater confidence, which in turn enables students to take on more challenging tasks that require more effort and higher levels of skill and try new approaches while learning translation technology. Those with greater self-esteem tend to take the initiative to explore and learn new technologies and have the courage to experiment with different applications [116]. This can be especially helpful when it comes to translation technology like machine translation, post-editing, and CAT, as it often requires a great deal of effort, creative problem-solving, and a willingness to try different approaches. At the same time, motivation is a crucial factor in achieving success, and self-esteem plays a significant role in improving motivation [117]. When students have a positive self-image and strong belief in their capabilities, they will be motivated to invest time and effort into mastering the technology and seek out additional resources to further their understanding of the technology and refine their skills. Additionally, self-esteem can provide a source of inspiration [118], helping students to remain positive and motivated even when faced with obstacles in translation practices. The increased motivation to use translation technology can also lead to greater willingness to share their experiences and successes with their peers, which can provide valuable feedback and guidance that can further help to improve performance.

Innovation capability has a direct influence on TTC among student translators. Increased adaptability to emerging technologies through innovation capability can help students stay on top of the latest advancements in translation technology and utilize the most up-to-date technical tools and processes. The capacity for innovation prompts students to investigate various methods for addressing their translation requirements and to implement inventive strategies when integrating translation technologies [119]. It also equips students with the ability to engage critically and analytically by involving them in active problem-solving because educators cannot offer students solutions to every problem they might encounter in their practices [120]. In addition, innovation capability can also help individuals to become more comfortable with ambiguity [121]. Innovative students are more willing to take risks and explore new technologies and approaches [22] to create translations that fit the context. This increased comfort with ambiguity can help students to make better decisions when faced with uncertain or incomplete information. By leveraging innovative approaches, students can ensure that they are able to scale their TTC to meet the needs of more complex projects, identify areas of improvement, and optimize their application of specific translation technology.

Mediating relations

Self-esteem has been identified as an essential factor mediating the correlation between emotional intelligence and TTC among student translators. Defined as an individual’s evaluation of their own worth and competence [122], self-esteem influences how people perceive, interpret, and interact with their environment, as well as how they respond to challenges and opportunities. Studies have shown that higher emotional intelligence correlates with greater levels of self-esteem [123], as emotionally intelligent individuals are better at identifying, comprehending, and regulating their own emotions and those of others [124]. They are more adept at recognizing their strengths and weaknesses [125] when using translation technology, focusing on areas that foster personal growth and bolster self-esteem. This process also facilitates more positive interactions with peers [64], potentially leading to higher levels of self-worth and increased willingness to persevere in acquiring TTC. In parallel, self-esteem itself is a critical factor in determining students’ TTC, as it influences their beliefs about their abilities and how successful they can be in this field.

Innovation capability also significantly mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence and TTC. Individuals with higher emotional intelligence tend to be more open to new ideas and better equipped to think innovatively [77, 84]. They can anticipate and recognize the potential risks and opportunities associated with translation projects, collaborate more effectively with peers and teachers [126], and resolve conflicts productively, all of which cultivate a supportive environment for creativity. Innovation capability, understood as an individual’s capacity to generate, develop, and implement new ideas efficiently [90], closely relates to problem-solving and other cognitive abilities. It allows student translators to harness diverse resources, techniques, and knowledge, fostering inventive solutions in challenging translation tasks. Moreover, innovation capability has been shown to influence students’ TTC [23], as it drives them to explore novel strategies and apply newly gained insights.

Beyond these individual mediation effects, self-esteem and innovation capability function sequentially in the linkage between emotional intelligence and TTC among EFL students. Students with elevated self-esteem show greater confidence in their capability for innovation, exhibit increased creativity, and are more inclined to take risks and explore new ideas [73, 127]. These tendencies enhance their determination and effort in confronting complex problems, leading them to adopt and refine translation technology skills more effectively. As self-esteem rises, individuals also tend to initiate fresh approaches essential for developing innovative solutions [128]. Thus, higher emotional intelligence fosters both self-esteem and innovation capability, ultimately facilitating greater TTC. By accounting for both mediators, educators, and researchers can better understand the underlying mechanisms through which emotional intelligence drives student translators’ success in translation technology.

Implications

Theoretical implications

This study highlights the significant influence of psychological factors such as emotional intelligence, self-esteem, and innovation capability on student’s TTC. The findings offer new insight into the cognitive processes and developmental pathways of TTC, which requires not only knowledge of translation technology, but also a mastery of the psychological factors that can affect a student’s competence and performance. Furthermore, it reveals the fundamental mechanism by which these psychological factors influence TTC to develop effective interventions. By incorporating psychological and translation theories, the research contributes to the interdisciplinary understanding of how these traits shape TTC and suggests pathways for designing interventions aimed at enhancing translation competence among student translators.

Practical implications

The findings offer actionable insights for translation educators and institutions aiming to improve students’ TTC through psychological and pedagogical strategies. Emotional intelligence was found to positively influence TTC, suggesting the need for translation curricula to incorporate activities that enhance this trait. Activities such as role-playing and discussions about emotional regulation can help students manage the complexities of translation tasks [129]. Additionally, integrating collaborative peer workshops where students practice responding to simulated translation challenges under emotionally charged scenarios could improve their adaptability and stress management skills. Further, collaboration with psychology departments to offer elective courses or guest lectures on emotional intelligence in professional contexts could enhance students’ ability to apply these skills specifically in translation scenarios. Educators should also assess students’ emotional intelligence levels and adapt teaching strategies to address specific needs, fostering a supportive classroom environment that encourages emotional growth [130].

Self-esteem emerged as another critical factor influencing TTC. Teachers can nurture self-esteem by creating a classroom atmosphere of trust and mutual respect, offering clear and structured guidance for mastering translation technologies, and providing constructive feedback that builds students’ confidence [131]. Providing students with opportunities to present their translation technology projects in non-evaluative settings, such as workshops or seminars, can also bolster self-esteem by highlighting their progress and achievements. Practical strategies could also include designing tiered learning modules that progressively increase in complexity, allowing students to achieve early successes and gradually tackle more challenging tasks. This scaffolding approach can reinforce confidence while maintaining motivation. Moreover, institutions can implement mentoring systems pairing senior students with junior learners to foster supportive relationships and instill confidence in both groups. Recognizing and rewarding innovative uses of translation technologies through awards or certificates can further enhance students’ sense of accomplishment and self-worth. Additionally, empowering students with autonomy in their learning process can help them take ownership of their success, mitigating anxiety and fostering a positive attitude toward translation technology.

Innovation capability was shown to play a significant role in shaping TTC. To enhance this, educators should integrate creative problem-solving tasks and encourage experimentation with new translation tools and methods. For instance, students can be tasked with creating personalized translation workflows using a combination of computer-assisted translation (CAT) tools, machine translation engines, and editing software. This approach can cultivate a mindset of exploration and adaptability. Assignments tailored to individual learning conditions, simulations, and translation competitions can deepen students’ understanding of the practical applications of innovation in translation [90]. Meanwhile, technology developers can design flexible, customizable interfaces that empower students to test out creative solutions, such as user-generated macros or plug-ins, thus directly fostering innovative capacities in authentic translation scenarios. Institutions could also partner with technology developers to provide access to beta tools, encouraging students to think critically and innovate by identifying bugs, offering feedback, and developing novel use cases. Promoting collaboration and open dialogue among students can further stimulate critical thinking and innovation, equipping them with the skills needed to excel in technology-driven translation tasks.

Conclusion

This study sought to investigate the psychological factors that should be cultivated in higher education institutions to improve students’ TTC through an empirical approach. The findings indicated that emotional intelligence, self-esteem, and innovation capability could all significantly contribute to a student’s proficiency in translation technology. Additionally, self-esteem and innovation capability served as independent and sequential mediating roles in the relationship between emotional intelligence and TTC. The results of this research offer a valuable perspective on how these psychological factors influence students’ acquisition of translation technology, which can be conducive to further studies and practices that strive to enhance students’ performance in translation technology through the psychological mechanism.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations that can inform directions for future research. First, the participants were drawn from seven public universities in China, which may constrain the generalizability of the findings to other cultural and institutional settings. Future studies could adopt cross-cultural or multi-institutional designs to better capture the influence of sociocultural variations on the relationships examined. Second, the cross-sectional design may limit the ability to infer causal relationships between variables. Longitudinal or experimental studies can be conducted to validate the proposed model and explore how the relationships evolve over time. Third, this research focused on three psychological factors: emotional intelligence, self-esteem, and innovation capability, while other potential influencers, such as critical thinking, resilience, or digital literacy, remain unexplored. Future research could investigate these factors to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the determinants of TTC.

Acknowledgements

We extend our deepest thanks to the teachers who aided in the distribution of the questionnaire and to the participants who kindly completed the questionnaires for this research.

Author contributions

Junfeng Zhao contributed to conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, and writing review & editing. Xiang Li contributed to formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, software, and writing– original draft. Jin Wei was responsible for validation, visualization, and writing– original draft. Xinyuan Long contributed to investigation, formal analysis, and writing review & editing. Zhaoyang Gao contributed to data curation, methodology, and supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the research grant (No. CTS202404) from the Center for Translation Studies, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of the School of Foreign Languages and Cultures at Panzhihua University provided ethical approval in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and validated that this study complied with both local and global regulations pertaining to research involving humans, prior to its commencement (Grant number: HRECA22-003). The participants provided the informed consent before filling out the questionnaire.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jiang X. Research on the analysis of correlation factors of English translation ability improvement based on deep neural network. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2022;2022:9345354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sitender BS. A Sanskrit-to-English machine translation using hybridization of direct and rule-based approach. Neural Comput Applic. 2021;33:2819–38. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu K, Kwok HL, Liu J, Cheung AKF. Sustainability and influence of machine translation: perceptions and attitudes of translation instructors and learners in Hong Kong. Sustainability. 2022;14:6399. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munkova D, Munk M, Benko Ľ, Hajek P. The role of automated evaluation techniques in online professional translator training. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2021;7:e706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esfandiari MR, Shokrpour N, Rahimi F. An evaluation of the EMT: compatibility with the professional translator’s needs. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2019;6:1601055. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu D, Zhang LJ, Wei L. Developing translator competence: understanding trainers’ beliefs and training practices. Interpreter Translator Train. 2019;13:233–54. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes JS. Translated! Papers on literary translation and translation studies. Amsterdam: Rodopi; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu L. A critical review of the research on translation psychology: theoretical and methodological approaches. LANS-TTS. 2020;19:53–79. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jääskeläinen R. Translation psychology. In: Gambier Y, van Doorslaer L, editors. Handbook of translation studies. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2012. pp. 191–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolaños-Medina A, Núñez JL. A preliminary scale for assessing translators’ self-efficacy. Lang Cult. 2018;19:53–78. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peña-Cervel MS, Ovejas-Ramírez C. Simple and complex cognitive modelling in oblique translation strategies in a corpus of English–Spanish drama film titles. Target. 2022;34:98–129. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Y, Cao X, Huo X. The psychometric properties of translating self-efficacy belief: perspectives from Chinese learners of translation. Front Psychol. 2021;12:642566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, Gao Z, Liao H. The effect of critical thinking on Translation Technology competence among College students: the Chain Mediating Role of Academic Self-Efficacy and Cultural Intelligence. PRBM. 2023;16:1233–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferdowsi S, Razmi MH. Examining associations among emotional intelligence, creativity, self-efficacy, and simultaneous interpreting practice through the mediating effect of field dependence/independence: a path analysis approach. J Psycholinguist Res. 2022;51:255–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rojo López AM, Cifuentes Férez P, Espín López L. The influence of time pressure on translation trainees’ performance: testing the relationship between self-esteem, salivary cortisol and subjective stress response. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0257727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao L, Zeng J. An empirical study on the improvement of students’ strategic competence through Translation Project Teaching. IES. 2023;16:123–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghaemi H, Bayati M. Others. A structural equation modeling of the relationship between emotional intelligence, burnout and translation competence of experienced translators. Trans Comp Educ. 2022;4:30–42. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lahodynskyi O, Bohuslavets A, Nitenko O, Sablina E, Viktorova L, Yaremchuk I. Emotional intelligence of translator: an integrated system of development. RREM. 2019;11:68–92. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haro Soler M. del M. Vicarious learning in the translation classroom: how can it influence students’ self-efficacy beliefs? ESNBU. 2019;5:92–113.

- 20.Nam S-J, Hwang H. Consumers’ participation in information-related activities on social media. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0250248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yildirim N, Karaca A, Cangur S, Acıkgoz F, Akkus D. The relationship between educational stress, stress coping, self-esteem, social support, and health status among nursing students in Turkey: a structural equation modeling approach. Nurs Educ Today. 2017;48:33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lytras MD, Serban AC, Ruiz MJT, Ntanos S, Sarirete A. Translating knowledge into innovation capability: an exploratory study investigating the perceptions on distance learning in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic - the case of Mexico. J Innov Knowl. 2022;7:100258. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun M, Qiu Y. Research on the development of Double Abilities of English majors through project-based assignment based on constructivist learning theory. In: 2018 International Conference on Education, Psychology, and Management Science (ICEPMS 2018). Shanghai: Francis Academic Press; 2018.

- 24.Plaza-Lara C. SWOT analysis of the inclusion of machine translation and postediting in the master’s degrees offered in the EMT network. J Specialised Translation. 2019;:260–80.

- 25.Zheng J, Fan W. Multivaried acceptance of post-editing in China: attitude, practice, and training. PS. 2022;13:644–62. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nunes Vieira L, Alonso E. Translating perceptions and managing expectations: an analysis of management and production perspectives on machine translation. Perspectives. 2020;28:163–84. [Google Scholar]

- 27.ATC. UK Language Services Industry Survey and Report 2021. London: The Association of Translation Companies; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Egdom G, Pluymaekers M. Why go the extra mile? How different degrees of post-editing affect perceptions of texts, senders and products among end users. J Specialised Translation. 2019;:158–76.

- 29.PACTE. Building a translation competence model. In: Alves F, editor. Triangulating translation: perspectives in process oriented Research. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2003. pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- 30.PACTE. Investigating translation competence: conceptual and methodological issues. Meta. 2005;50:609–19. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Directorate-General for Translation. European Master’s in Translation-EMT competence Framework 2022. Brussels: The European Master’s in Translation (EMT); 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olalla-Soler C. Using electronic information resources to solve cultural translation problems: differences between students and professional translators. J Doc. 2018;74:1293–317. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prieto Ramos F. The use of resources for legal terminological decision-making: patterns and profile variations among institutional translators. Perspectives. 2021;29:278–310. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowker L. Computer-aided translation technology: a practical introduction. Ottawa: University of Ottawa; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiocchetti E, Wissik T, Lusicky V, Wetzel M. Quality assurance in multilingual legal terminological databases. J Specialised Translation. 2017;:164–88.

- 36.Martín Mor A. Do translation memories affect translations? Final results of the TRACE project. Perspectives. 2019;27:455–76. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ortega JE, Forcada ML, Sanchez-Martinez F. Fuzzy-match repair guided by quality estimation. IEEE T Pattern Anal. 2022;44:1264–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiménez-Crespo MA. The effect of translation memory tools in translated web texts: evidence from a comparative product-based study. LANS-TTS. 2021;8:213–32. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, Wang K, Zong C, Su K-Y. A unified framework and models for integrating translation memory into phrase-based statistical machine translation. Comput Speech Lang. 2019;54:176–206. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang G, Zhang J, Zhou Y, Zong C. Input method for human translators: a novel approach to integrate machine translation effectively and imperceptibly. Acm T Asian Low-reso. 2019;18:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang C, Peng J, He X. Effects of flipped blended learning based on assessment: an action research study in translation technology education. Technol Pedagogy Educ. 2024;33:613–28. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodríguez-Castro M. An integrated curricular design for computer-assisted translation tools: developing technical expertise. Interpreter Translator Train. 2018;12:355–74. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bundgaard K, Christensen TP, Schjoldager A. Translator-computer interaction in action: an observational process study of computer-aided translation. J Specialised Translation. 2016;:106–30.

- 44.Alotaibi HM. Computer-assisted translation tools: an evaluation of their usability among arab translators. Appl Sci. 2020;10:6295. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salovey P, Mayer JD. Emotional intelligence. Imagination Cognition Personality. 1990;9:185–211. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hubscher-Davidson S. Translation and emotion: a psychological perspective. New York: Routledge; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rojo A, Ramos Caro M. In: Lacruz I, Jääskeläinen R, editors. Chapter 6. The role of expertise in emotion regulation: exploring the effect of expertise on translation performance under emotional stir. American Translators Association Scholarly Monograph Series. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2018. pp. 105–29. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ożańska-Ponikwia K. Emotions from a Bilingual Point of View: personality and Emotional Intelligence in Relation to Perception and expression of emotions in the L1 and L2. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publ; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hubscher-Davidson S. Emotional intelligence and translation studies: a new bridge. Meta. 2013;58:324–46. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghobadi M, Khosroshahi S, Giveh F. Exploring predictors of translation performance. Trans-Int. 2021;13.

- 51.Varzande M, Jadidi E. The effect of translators’ emotional intelligence on their translation quality. Engl Lang Teach. 2015;8:104–11. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheung C-K, Cheung HY, Hue M-T. Emotional intelligence as a basis for self-esteem in young adults. J Psychol. 2015;149:63–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taylor SE, Kemeny ME, Reed GM, Bower JE, Gruenewald TL. Psychological resources, positive illusions, and health. Am Psychol. 2000;55:99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Di Paula A, Campbell JD. Self-esteem and persistence in the face of failure. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;83:711–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frérot C, Landry A, Karagouch L. Multi-analysis of translators’ work: an interdisciplinary approach by translator and ergonomics trainers. Interpreter Translator Train. 2020;14:422–39. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hurtado Albir A, editor. Researching translation competence by PACTE Group. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Romney J. Collaborative learning in a translation course. Can Mod Lang Rev. 1997;54:48–67. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cifuentes-Ferez P, Fenollar-Cortes J. On the impact of self-esteem, emotion regulation and emotional expressivity on student translators’ performance. VIAL-Vigo Int J Appl Linguistics. 2017;14:71–97. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luo H, Meng Y, Lei Y. China’s language services as an emerging industry. Babel. 2018;64:370–81. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Desjardins R. A preliminary theoretical investigation into [online] social self-translation: the real, the illusory, and the hyperreal. Transl Stud. 2019;12:156–76. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li J, Zhou H, Huang S, Cheng S, Chen J. Eliciting the translation ability of large Language models via Multilingual Finetuning with translation instructions. Trans Association Comput Linguistics. 2024;12:576–92. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jansen H. I’m a translator and I’m proud: how literary translators view authors and authorship. Perspectives. 2019;27:675–88. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zeidner M, Matthews G, Roberts RD. What we know about Emotional Intelligence: how it affects Learning, Work, relationships, and our Mental Health. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sa B, Ojeh N, Majumder MAA, Nunes P, Williams S, Rao SR, et al. The relationship between self-esteem, emotional intelligence, and empathy among students from six health professional programs. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:536–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peláez-Fernández MA, Rey L, Extremera N. A sequential path model testing: emotional intelligence, resilient coping and self-esteem as predictors of depressive symptoms during unemployment. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2021;18:697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saati M, NasiriZiba F, Haghani H. The correlation between emotional intelligence and self-esteem in patients with intestinal stoma: a descriptive‐correlational study. Nurs Open. 2021;8:1769–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Salovey P, Sluyter DJ, editors. Emotional development and Emotional Intelligence: Educational implications. 1st ed. New York: Basic Books; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schutte NS, Malouff JM, Simunek M, McKenley J, Hollander S. Characteristic emotional intelligence and emotional well-being. Cogn Emot. 2002;16:769–85. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Obeid S, Haddad C, Zakhour M, Fares K, Akel M, Salameh P, et al. Correlates of self-esteem among the Lebanese population: a cross-sectional study. Psychiat Danub. 2019;31:429–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yiyi O, Jie P, Jiong L, Jinsheng T, Kun W, Jing L. Research on the influence of sports participation on school bullying among college students-chain mediating analysis of emotional intelligence and self-esteem. Front Psychol. 2022;13:874458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jiménez Ballester AM, de la Barreera U, Schoeps K, Montoya-Castilla I. Emotional factors that mediate the relationship between emotional intelligence and psychological problems in emerging adults. Behav Psychol. 2022;30:249–67. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thatcher SMB, Brown SA. Individual creativity in teams: the importance of communication media mix. Decis Support Syst. 2010;49:290–300. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang Y, Wang L. Self-construal and creativity: the moderator effect of self-esteem. Pers Indiv Differ. 2016;99:184–9. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hong M, Dyakov DG, Zheng J. Self-esteem and psychological capital: their mediation of the relationship between big five personality traits and creativity in college students. J Psychol Afr. 2020;30:119–24. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wu X, Guo J, Wang Y, Zou F, Guo P, Lv J, et al. The relationships between trait creativity and resting-state EEG microstates were modulated by self-esteem. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14:576114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rodrigues AP, Jorge FE, Pires CA, António P. The contribution of emotional intelligence and spirituality in understanding creativity and entrepreneurial intention of higher education students. ET. 2019;61:870–94. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Silva D, Coelho A. The impact of emotional intelligence on creativity, the mediating role of worker attitudes and the moderating effects of individual success. J Manage Organ. 2019;25:284–302. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bonesso S, Gerli F, Pizzi C, Boyatzis RE. The role of intangible human capital in innovation diversification: linking behavioral competencies with different types of innovation. Ind Corp Change. 2020;29:661–81. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Agnoli S, Franchin L, Rubaltelli E, Corazza GE. The emotionally intelligent use of attention and affective arousal under creative frustration and creative success. Pers Indiv Differ. 2019;142:242–8. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lea RG, Qualter P, Davis SK, Pérez-González J-C, Bangee M. Trait emotional intelligence and attentional bias for positive emotion: an eye tracking study. Pers Indiv Differ. 2018;128:88–93. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Su H, Zhang J, Xie M, Zhao M. The relationship between teachers’ emotional intelligence and teaching for creativity: the mediating role of working engagement. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1014905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Paek B, Martyn J, Oja BD, Kim M, Larkins RJ. Searching for sport employee creativity: a mixed-methods exploration. Eur Sport Manage Q. 2022;22:483–505. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Othman N, Tengku Muda TNAA. Emotional intelligence towards entrepreneurial career choice behaviours. ET. 2018;60:953–70. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stawicki C, Krishnakumar S, Robinson MD. Working with emotions: emotional intelligence, performance and creativity in the knowledge-intensive workforce. J Knowl Manag. 2023;27:285–301. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Parke MR, Seo M-G, Sherf EN. Regulating and facilitating: the role of emotional intelligence in maintaining and using positive affect for creativity. J Appl Psychol. 2015;100:917–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Blázquez Puerta CD, Bermúdez-González G, Soler García IP. Human systematic innovation helix: knowledge management, emotional intelligence and entrepreneurial competency. Sustainability. 2022;14:4296. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li X, Chang H, Zhang Q, Yang J, Liu R, Song Y. Relationship between emotional intelligence and job well-being in Chinese clinical nurses: multiple mediating effects of empathy and communication satisfaction. Bmc Nurs. 2021;20:144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 88.D’zurilla TJ, Chang EC, Sanna LJ. Self-esteem and social problem solving as predictors of aggression in college students. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2003;22:424–40. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wong C-S, Law KS. The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude. Leadersh Q. 2002;13:243–74. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Selznick BS, Mayhew MJ. Measuring undergraduates’ innovation capacities. Res High Educ. 2018;59:744–64. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Baumol WJ. The Microtheory of innovative entrepreneurship. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jing X, Meng H, Li Y, Lu L, Yao Y. Associations of psychological capital, coping style and emotional intelligence with self-rated health status of college students in China during COVID-19 pandemic. PRBM. 2022;15:2587–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kong F, Zhao J, You X. Emotional intelligence and life satisfaction in Chinese university students: the mediating role of self-esteem and social support. Pers Indiv Differ. 2012;53:1039–43. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zou R, Zeb S, Nisar F, Yasmin F, Poulova P, Haider SA. The impact of emotional intelligence on career decision-making difficulties and generalized self-efficacy among university students in China. Psychol Res Behav Ma. 2022;15:865–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen F. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the revised-positive version of Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Adv Psychol. 2015;5:531–5. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jia N, Sakulsriprasert C, Wongpakaran N, Suradom C, O’ Donnell R. Borderline personality disorder symptoms and its clinical correlates among Chinese university students: a cross-sectional study. Healthcare-basel. 2022;10:1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Salhieh SM, Al-Abdallat Y. Technopreneurial intentions: the effect of innate innovativeness and academic self-efficacy. Sustainability. 2021;14:238. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Goldsmith RE, Freiden JB, Eastman JK. The generality/specificity issue in consumer innovativeness research. Technovation. 1995;15:601–12. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pallister JG, Foxall GR. Psychometric properties of the Hurt-Joseph-Cook scales for the measurement of innovativeness. Technovation. 1998;18:663–75. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jabłońska MR, Zajdel R. Artificial neural networks for predicting social comparison effects among female Instagram users. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0229354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tehseen S, Ramayah T, Sajilan S. Testing and controlling for common method variance: a review of available methods. jms2014. 2017;4:142–68. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Harman HH. Modern Factor Analysis. Third Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1976.

- 104.Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981;18:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Meng F-C, Xu X-J, Song T-J, Shou X-J, Wang X-L, Han S-P, et al. Development of an autism subtyping questionnaire based on social behaviors. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34:789–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bagozzi RP, Yi Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J Acad Market Sci. 1988;16:74–94. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Huang Y, Wu Y, Dai Z, Xiao W, Wang H, Si M, et al. Psychometric validation of a Chinese version of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy scale: a cross-sectional study. Bmc Infect Dis. 2022;22:765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.McDonald RP, Ho M-HR. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:64–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Second edition. New York: Guilford Press; 2018.

- 110.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing Indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nicholls L, Webb C. What makes a good midwife? An integrative review of methodologically-diverse research. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56:414–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Korkmaz S, Danacı Keleş D, Kazgan A, Baykara S, Gürkan Gürok M, Feyzi Demir C, et al. Emotional intelligence and problem solving skills in individuals who attempted suicide. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;74:120–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhang SJ, Chen YQ, Sun H. Emotional intelligence, conflict management styles, and innovation performance: an empirical study of Chinese employees. Int J Confl Manage. 2015;26:450–78. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hendon M, Powell L, Wimmer H. Emotional intelligence and communication levels in information technology professionals. Comput Hum Behav. 2017;71:165–71. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Forsyth DR, Lawrence NK, Burnette JL, Baumeister RF. Attempting to improve the academic performance of struggling college students by bolstering their self-esteem: an intervention that backfired. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2007;26:447–59. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yu Z, Hao J, Shi B. Dispositional envy inhibits prosocial behavior in adolescents with high self-esteem. Pers Indiv Differ. 2018;122:127–33. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Herrmann J, Koeppen K, Kessels U. Do girls take school too seriously? Investigating gender differences in school burnout from a self-worth perspective. Learn Individ Differ. 2019;69:150–61. [Google Scholar]