Abstract

Objective: Like medical and health sciences libraries throughout the country, the Lamar Soutter Library (LSL) at the University of Massachusetts Medical School is dealing with ever-increasing outreach needs in times of diminishing funding. With the goal of reshaping the library's outreach program to better serve our patron groups, the Outreach Study Group was formed to investigate existing models of outreach.

Methods: The group initially examined the current literature and subsequently conducted a nationwide survey of medical and health sciences libraries to identify trends in outreach. This article details the methods used for the survey, including establishing criteria for selecting participants, determining the focus, and developing and conducting the survey.

Results: Of the 40 libraries invited to participate, 63% completed the survey. An analysis of the data revealed successes, problems, and trends. The group's conclusions led to recommendations for the LSL's future outreach efforts.

Conclusions: Analysis of the data revealed key findings in the areas of strategic planning, funding, and evaluation. A thoughtful definition of outreach ensures that outreach activities are expressions of the library's mission. Funding shifts require flexible programs. Evaluation provides data necessary to create new programs, sustain successful ones, and avoid repeating mistakes.

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

Outreach is a service commonly pursued by medical libraries. Outreach activities in libraries have the potential to involve many staff members, serve multiple audiences, use several project methods, and cost a great deal of money. Without thoughtful rationale and direction, library outreach activities may simply be immediate responses to service requests or service needs perceived in the moment. Well-intentioned but unfocused efforts can result in redundant and uncoordinated projects that cannot be sustained.

The Lamar Soutter Library (LSL) serves the faculty, students, and staff of the University of Massachusetts Medical School and affiliated sites, supporting their education and research information needs. It is the only public medical library in Massachusetts. To support the school's clinical partner, UMass Memorial Health Care System and its affiliated hospital network, LSL serves health care professionals and their patients throughout central and western Massachusetts.

To encourage a strategic approach to outreach, Elaine Russo Martin, director of the LSL, charged a newly formed Outreach Study Group (composed of seven staff members from five departments) to investigate outreach models and to make recommendations for future outreach activities at the LSL. The group set out to determine characteristics that contribute to successful outreach programs, as well as characteristics that lead to unsuccessful programs. The group's methodology was to talk with other health sciences librarians about their outreach activities and draw conclusions about factors that contribute to the success of an outreach program.

This paper describes the group's efforts to gather and analyze data and presents recommendations to help health sciences libraries assume strategic and thoughtful approaches to outreach activities.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The health sciences library professional literature is replete with descriptions of specific outreach projects intended to meet the information needs of various library constituents. Although these papers contain much of interest, the question of the broader purpose of an outreach program in medical libraries is not addressed.

Some papers discuss the history and significance of health sciences library outreach. Pifalo traces a history of outreach in rural areas [1]. Scherrer and Jacobson note that outreach is fast becoming a core duty of librarians, and, therefore, ways to assess this work should be formulated to accurately portray library work to administrators [2]. Increase in outreach activity is due in part to the National Library of Medicine's (NLM's) long-range plan Improving Health Professionals' Access to Information, in which NLM identifies outreach to health professionals as a priority [3].

Although the literature contains little discussion of the characteristics of medical library outreach in general, some papers describe traits of particular projects. Several authors describe features that contribute to a successful project. Dorsch finds that outreach to rural health professionals is more successful with a liaison at the outreach site [4]. McGowan examines outreach in a health sciences library at a land grant institution and finds that forming partnerships and making outreach a core value of the library are vital to success. She also predicts that to ensure continued success, libraries would need to rely on revenue generated from outreach projects for funding [5]. Wood et al. describe an outreach project to a specific audience (Native Americans) and emphasize the importance of the initial needs assessment [6].

Other papers describe features of specific projects that had mixed success. Scherrer describes problems encountered in a project focusing on community organizations, including not knowing the audience and its needs sufficiently, not clearly stating the responsibilities of all parties, and overestimating the computer skills of the constituents [7]. Banks et al. present lessons learned from four outreach projects [8]. The authors identify several challenges to successful outreach projects, including time, money, technology, and collaboration. Both Scherrer and Banks et al. suggest strategies for dealing with such challenges.

Other articles, while not focusing on specific projects, describe traits of outreach to specific audiences. Rambo et al. describe characteristics of medical library outreach to public health professionals [9]. The authors emphasize the importance of a needs assessment and clear objectives. The authors also report that attendees at a forum identified two approaches to outreach: a library-centered model, in which library services are promoted to a new audience, and an audience-centered model, in which the librarian assesses information needs and designs a plan to fill those needs.

Although medical and health sciences librarians take great care to describe their outreach projects in the professional literature, little has been written about the overall nature and characteristics of medical library outreach. Missing from the literature is a paper compiling the traits of multiple projects across multiple institutions and analyzing them in terms of success factors and challenges.

The group revisited the literature after completing the survey and found a recently published paper by the National Council on Disabilities [10]. The paper focuses on the literature of outreach to people with disabilities and/or from diverse cultures, identifies characteristics of outreach, and draws conclusions. Although some points are very specific to issues of disability and diversity, others are applicable to outreach in general. The authors identify six themes from the literature: basing value on target population, assessing needs, advocating, transforming social behaviors and attitudes, disseminating information, and strengthening communities. In addition, the report identifies six methods of outreach as well as sixteen challenges to outreach. Many of these are specific to disability and diversity outreach, but many others are similar to challenges described in the library literature: limited funding, lack of an assessment of needs, failure to engage local leaders, and lack of coordinated services. However, the majority of the report examines outreach in the context of federal agency outreach to people with disabilities from diverse cultures. A thorough review of outreach of this sort is still missing from the professional medical library literature. Interestingly, although the report was written in a very different context, the authors reached the same conclusion that the LSL group had: not much has been written in general about the effectiveness of outreach and empirical research is lacking.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Conducting the survey

The group decided to use a survey as the instrument to gather data. Open-ended questions were used to elicit details and to avoid leading respondents to predetermined conclusions. To encourage participation, the survey was short. The group estimated that the participants would need only fifteen to twenty minutes to complete the process.

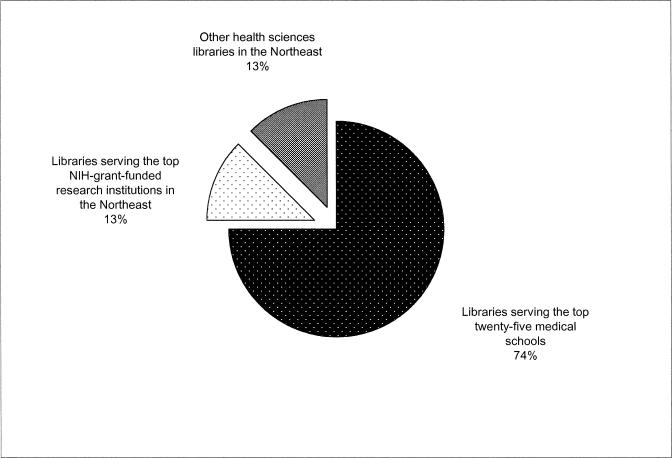

For consistency, the group scripted an invitation to participate. The group members emailed the scripted formal invitation to each targeted participant (Appendix A). Those who agreed to participate received the survey in electronic format. As a way to accommodate preferences and to encourage a high response rate, the group gave participants the option of returning completed surveys or answering the questions during a telephone call. In either case, every participant received a telephone call. For those who had sent back a completed survey, the telephone call served to clarify the responses. Otherwise, the survey was conducted over the telephone. The efforts to accommodate were successful, even though the group vastly underestimated the amount of time each telephone call would require. The average telephone call lasted from thirty to sixty minutes. The majority of respondents were enthusiastic about discussing their projects and were generous with their time. The group achieved a response rate of 63% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Breakdown of survey participants

Selection criteria

Using the following criteria, the group targeted forty medical and health sciences libraries as possible participants in the survey:

libraries serving the top twenty-five medical schools, as defined by “The Best Graduate Schools” issue of U.S. News & World Report, 2002 [11]

libraries serving the top National Institutes of Health (NIH)–grant-funded research institutions in the Northeast [12]

other health sciences libraries in New England

These criteria were chosen with the guidance of the library director and with an eye toward reaching the LSL's aspirant peer group. Each library's Website provided the initial contact information via their staff listings. Staff whose position titles included the word “outreach” became the contacts. If a given library did not have such personnel, the head of reference or the library's director was the default contact. In some cases, the initial contact provided the name of another staff member who could more appropriately answer the questions.

Survey description

The first page of the survey included a brief introduction to what the group was trying to accomplish. This page also solicited demographic information, so that the group could compare each responding library to the LSL. The second page asked one question, “How would you define outreach at your library?” The group was grappling with defining outreach in terms of the LSL and thought it would be helpful to consider how other libraries defined “outreach.” The third page was a “Project Description” form, which asked for information regarding three to five outreach projects from each library. The last page was a summary page to identify success factors and obstacles to success by asking respondents to identify their most successful and least successful projects.

The survey was beta-tested internally with the help of LSL staff from several departments. As a result of the testing, the group modified the survey to clarify the instructions as well as several questions that test respondents had found ambiguous. In addition, testing provided guidance as to the method of conducting the survey. If group members could receive the completed forms before calling, they could use the call to ask respondents to elaborate on or clarify certain points, rather than to try to collect all the information orally. Also, encouraging respondents to complete the survey electronically would facilitate sharing the information among group members later.

At this point, the group discovered a flaw in its approach to the summary questions. When the test respondents were asked to identify “less successful” projects, they hesitated to judge projects in those terms. So, in the final survey, the group instead asked respondents to discuss some obstacles to success. Appendix B contains the survey in its final format.

RESULTS

As this was a qualitative survey, the group identified trends and patterns in the responses and defined categories to quantify the results.

Questions about outreach

What was each institution's definition of outreach?

The survey returned many definitions of outreach. Some focused on specific audiences, others focused on specific types of activities, and others focused on a particular theory or philosophy. Some examples of definitions follow:

“It depends on when you ask.”

“Outreach is serving unaffiliated users for a fee.”

“Extending the provision of library services beyond the physical boundaries of the library.”

“Any outside of the library activities on or off campus with the intent to provide support to staff, students, and faculty.”

“Provide information skills training to health professionals and/or consumers through training, [interlibrary loan] (ILL), document delivery, and quality-filtered Websites.”

What outreach projects were being done?

The group identified six categories of projects from the seventy-six projects listed by survey respondents. Some projects had goals in more than one category. The categories are:

Training (forty-two projects): delivering instruction

Consultation/Research (twenty-one projects): offering traditional library assistance and services, such as reference, research, and interlibrary loan

Marketing (nineteen projects): increasing the library's visibility

Technical Expertise (fifteen projects): contributing expertise to help other groups with technical projects, such as setting up a Website, an email list, or a network of computers

Liaison (nine projects): assigning library representatives to specific departments in the home institution to facilitate services and communication between the library and respective departments

Web (four projects): creating a library-sponsored Website for a particular purpose or audience

Traditional library activities of training or instruction and consultation or research ranked as the most popular goals. Marketing was a goal of only 25% of the programs. Although many projects incorporated Web-based information, only four projects focused on a Website as a goal. Liaison programs were also surprisingly less common than the group expected. Only nine of the seventy-six projects were specified as liaison projects, although liaison programs in medical libraries are traditional and have a long history [13]. Libraries might have underreported liaison programs, because they could be considered part of the routine work of librarians, as noted by Scherrer [14].

What contributes to a successful project?

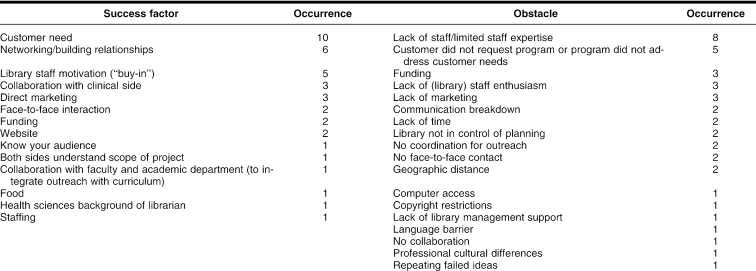

Table 1 presents the reported success factors and obstacles. The most commonly cited success factor for outreach projects was understanding customer need. The most commonly mentioned obstacle to success was lack of staff or limited staff expertise.

Table 1 Success factors and obstacles

How did these institutions compare to the Lamar Soutter Library and what were the demographics of each one?

Library organization among the targeted group varied widely, and the methods of collecting and reporting statistics varied widely. However, the group believes that the responding health sciences libraries had similar outreach experiences, regardless of demographics. They all reported similar projects with basically the same successes and obstacles.

Other data collected

The group asked for a variety of information about several aspects of each project. This resulted in some valuable information, especially in the areas of funding, evaluation, and audience.

Funding sources

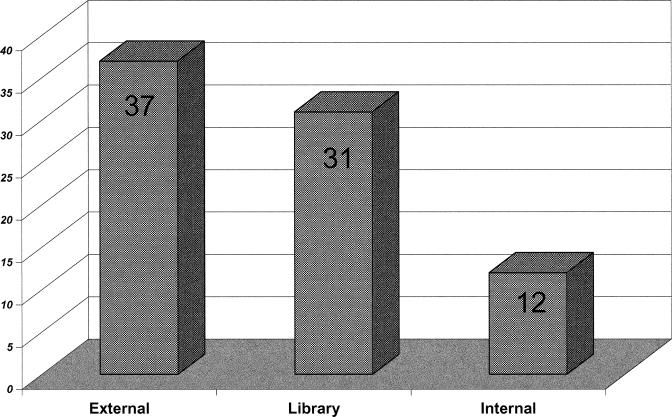

Librarians reported funding information for seventy of the seventy-six projects (Figure 2). Eight projects had multiple funding sources, resulting in eighty total funding sources. The group divided funding into three categories: external, internal, and library.

External funding comes from sources outside the library and the library's parent institution. Of the eighty funding sources noted, thirty-seven were external, making this the largest category. Of these thirty-seven, twenty-five were grants and six were fees for service.

Internal funding comes from sources within the library's parent institution, but not the library itself. The twelve instances of internal funding made this the smallest funding category. Eight of the twelve instances were institutional departments that were at least partially paying for services received.

Library funding comes from the library's budget. Thirty-one of the eighty sources were library funded.

Figure 2.

Sources of funding for outreach

Evaluation method

Thirty-nine projects out of seventy-six (51%) used some formal evaluation method. Another ten projects (13%) contained evaluation plans that had not yet been carried out at the time of the survey. Some used more than one method of evaluation. Evaluation methods ranged from analyzing usage statistics and evaluation forms to focus groups and testing.

Audience

Six audience categories were identified by respondents. Faculty and health professionals were the most targeted audiences, with consumers and students not far behind. Each of those four groups was cited as an audience for between twenty-two and thirty projects. Librarians and public health workers were the two least targeted audiences (associated with only nine and seven projects, respectively). Many projects were geared toward multiple audiences.

Health professionals and consumers made up 69% of the audience of projects funded by grants. Faculty, students, and health professionals made up 73% of the audience of projects funded internally by library operating budgets. Faculty, students, and health professionals made up 88% of the audience of projects funded by the library's institution. Health professionals and consumers made up 100% of the audience for fee-based projects.

DISCUSSION

The group felt that an open-ended method of data collection worked well because it did not lead the respondents to predetermined conclusions. Allowing respondents to word their own answers led to more detailed and candid responses than would have been received through a structured survey instrument.

However, it is important to note that this open-ended method did result in some limitations. Due to the respondents' variations in wording and vocabulary and the interviewers' differing styles, each survey response was very different from the next. This in turn made the data difficult to analyze. Also, each respondent was free to choose which projects to describe. These choices might have resulted in some libraries reporting only on successful projects or on those that most closely exemplified their definition of outreach.

The group anticipated that a formal definition of outreach, as it pertained to each institution, would form the basis of a strategic plan for outreach. Based on the survey data, the group could not prove whether the projects were part of strategic plans. The survey did not ask the origin of the respondent's definition. So although the definitions provided the group with some food for thought, they did not really help the group determine if a library was working from a larger outreach plan or simply executing stand-alone projects.

Only some libraries' outreach projects correlated closely with their given definitions of outreach. Possibly, these libraries had projects that closely matched their definition because the definition was derived from the projects and not the other way around. In either case, whether the project met the definition did not seem to be a factor in whether it was judged to be successful.

The group expected that one goal of outreach, marketing the library and its services, would be much more common than it was reported to be. This result might suggest that many libraries viewed outreach as a service and to a much lesser extent as an opportunity for them to increase the visibility of the library. Or it might suggest that measures taken primarily to increase a library's visibility were not considered outreach at all by some libraries. Strictly Web-based goals were not common either, although many projects had a Web component. Significantly, two libraries specified direct human contact as key to an effective project. Websites and computer networks complemented outreach but did not seem to be a satisfactory replacement for person-to-person interaction.

It is important to note that in Table 1 the opposite of many “successes” appear on the “obstacles” side and vice versa. For example, three institutions said that direct marketing was a success factor and three institutions said that lack of marketing was an obstacle. However, it is equally important that many successes and obstacles do not have their mirror images listed. Lack of time was cited as an obstacle by two institutions, but having enough time was not cited by anyone as a success factor. The number one obstacle was lack of staff or limited staff expertise. However, only one institution cited enough staff as a key to success, and only one other institution cited the expertise of a staff member as a success factor. This suggested health sciences librarians were unaware of the basic elements required for a successful project. If any one element was absent and the project was less than successful, only then did the librarians realize its importance.

NLM emphasized the importance of evaluation in its 2000 publication, Measuring the Difference: Guide to Planning and Evaluating Health Information Outreach. This guide stressed the need to conduct evaluation at all stages of a project.

Overall, evaluation helps programs refine and sharpen their focus; provide accountability to funders, managers, or administrators; improve quality so that effectiveness is maximized; and better understand what is achieved and how outreach has made a difference. Limited attention to evaluation can result in continuation of outreach activities that are ineffective and/or inefficient; failure to set priorities; or an inability to demonstrate to funding agencies that the outreach activities are of high quality. [15]

Despite NLM's emphasis on evaluation, 36% of projects did not report any formal evaluation methods. Clearly, health sciences libraries were still struggling with implementation and use of evaluation.

Choosing the appropriate audience is an important aspect of preprogram planning and needs assessment, and the survey results confirmed that targeting the appropriate audience is essential. One survey respondent relayed the story of a program that failed to draw the original targeted audience but was widely successful when redirected to another audience.

Projects were often considered successful when they were designed to meet needs the intended audience had self-identified; not meeting those needs was cited as an obstacle. Either the library staff defined a “need” that was not recognized by the target audience or the program did not meet the correct need. This result spoke directly to two fundamental concepts: developing and maintaining a relationship with the groups served and adequately assessing needs.

There seemed to be no correlation between the number of projects reported and the number of audiences targeted. Even when an institution reported many projects, each project targeted the same audiences. In most cases, an institution was not trying to reach every potential audience. Although some libraries defined outreach in terms of target audience, many did not. It was difficult to determine whether choosing some audiences over others signified a library was deliberately following a plan or merely following tradition.

The survey data suggest that type of funding affects the choice of audience. It appears that libraries spend operating budget dollars on internal customers (students, faculty, and/or health professionals) and look for other funding sources to serve other audiences.

In the current economic environment, it is not surprising that lack of funding was cited as one of the top three reasons why an outreach activity failed. Thirty-one of the seventy projects for which funding information was reported were funded in whole or in part by regular library budget dollars. One implication of this is that, given the current fiscal crises in many libraries, outreach projects funded by a library's budget could be adversely affected or cut entirely.

The majority of outreach projects that were reported did not involve fees or charges from the library to the audience. Historically, librarians have been reluctant to charge fees [16]. However, fees represent an underutilized source of funding that librarians may reconsider. Grants, special endowment funds, and gifts are other external sources of funding represented in the survey results. Perhaps still other sources of funding exist and deserve consideration.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Our review of the literature and the results of our qualitative survey led us to formulate specific recommendations for future outreach activities at the LSL. Our recommendations have broad implications that should be considered by the medical and health sciences library community.

First, simply understanding what “outreach” means is critical. The exercise of carefully considering goals and objectives and using this knowledge to craft a definition of outreach for an institution is a valuable one. A thoughtful definition clarifies the focus and simplifies the selection of activities. Each institution should have a clear understanding of what “outreach” means to that institution. Also, the medical and health sciences library community needs to have a greater understanding of what we mean when we talk about “outreach.” The lack of a common definition of outreach among medical and health sciences libraries is an obstacle for librarians who would benefit from sharing their outreach experiences with each other. Recognizing this obstacle is a first step toward a more meaningful dialogue.

Second, an institution's definition of outreach should be the basis of a strategic plan for outreach. Strategic planning has been an important component of successful business practices since the 1970s [17] and is widely recognized as an effective planning tool in libraries [18]. Therefore, the systematic development of an outreach plan can be key to the success of outreach activities. A comprehensive outreach plan should include detailed goals and objectives, assessment and evaluation methods, and a marketing strategy. A strategic approach to outreach can turn haphazard outreach efforts into a single focused program that can enhance a health sciences library's ability to deliver health information to its patrons.

Third, it is critical that the librarians conducting outreach are clear about a library's outreach definition and that they ensure that the outreach efforts are consistent with the goals of the library's outreach program and the mission of the institution. A particular project's success does not necessarily imply overall success of an outreach program unless the project makes sense in terms of the institution's outreach goals.

Fourth, it is essential to match the audience with the project. It may be difficult to know what the audience wants, rather than what the library thinks it needs. Developing long-term relationships with patron groups helps librarians understand patron needs. The outreach delivery method can be just as critical to success as content. A Website will not be successful if what a particular group wants is direct personal contact. Establishing relationships with patron groups helps librarians not only understand their wants and needs, but also the best delivery methods.

Fifth, a greater effort needs to be made to plan for and conduct evaluation. Although discussed frequently, evaluation often falls by the wayside. Evaluation is critical for answering important questions: Was the project a success? What could be done differently next time? Following a plan that places a high priority on evaluation will help to make sure that it is done and, more importantly, that the results are used in the future. The continuous cycle of assessment, delivery, evaluation, and reassessment is essential to the continued success of outreach programs as well as individual outreach activities.

Sixth, the materials from previous projects should be accessible to current outreach staff. Many outreach projects involve the use of training or marketing materials and planning and evaluation tools. Effectively managing the knowledge gained from past outreach projects enables outreach planners to introduce best practices into outreach programming. Past project elements can be judiciously “mixed and matched” to allow for more cost-effective projects requiring less staff time for project development. Also, a review of past project evaluations helps ensure that methods that did not work well will not be repeated.

Seventh, funding for outreach needs to be approached with flexibility and creativity. Exploring funding options apart from those provided by the library budget is necessary. Providing staff with the tools to identify and acquire alternative sources of funding (such as grant-writing and fund-raising skills) will increase the likelihood of effectively creating and maintaining outreach programs.

In addition, outreach goals and methods must be continuously reviewed. Factors such as staffing and funding change all too quickly. As outreach programs are evaluated and reassessed, the outreach definition must also be reviewed. Whether on an annual basis or with the development of strategic planning for the library or the institution, the definition and plan must be addressed regularly.

Although outreach activities are affected by forces such as economic trends and institutional policies and staffing, the use of outreach activities to deliver information as well as market library services is likely to continue. Carefully defining outreach for the library as well as developing and assessing an outreach strategic plan helps ensure that future outreach activities help the library meet its goals and fulfill its mission.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elaine Russo Martin who read drafts of the manuscript and offered suggestions, Carol Scherrer who reviewed an early draft of the survey, LSL staff who beta-tested the survey, Jeff Long who proofread, and Renee Rice and Diana Crosbie who provided graphics support. We are indebted to all of the health sciences librarians who were generous with their time, completed the survey, and enthusiastically shared information about their projects.

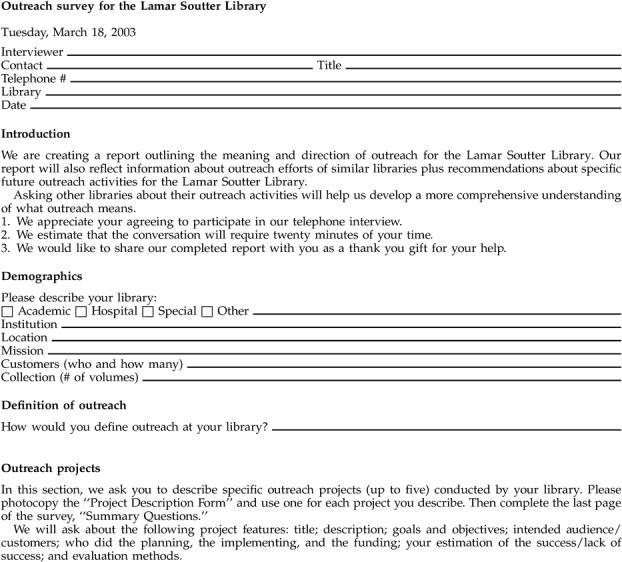

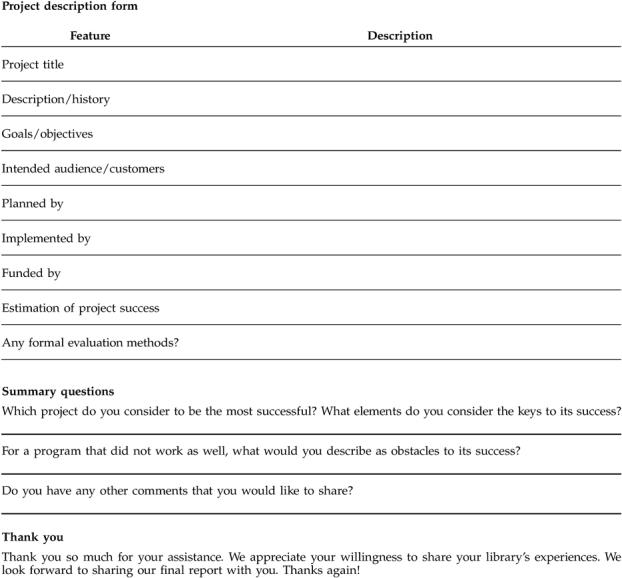

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX B

Contributor Information

Jane Fama, Email: jane.fama@umassmed.edu.

Donna Berryman, Email: donna.berryman@umassmed.edu.

Nancy Harger, Email: nancy.harger@umassmed.edu.

Paul Julian, Email: paul.julian@umassmed.edu.

Nancy Peterson, Email: nancy.peterson@umassmed.edu.

Jennifer Varney, Email: jvarney@blc.org.

REFERENCES

- Pifalo V. The evolution of rural outreach from Package Library to Grateful Med: introduction to the symposium. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Oct; 88(4):339–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer CS, Jacobson S. New measures for new roles: defining and measuring the current practices of health sciences librarians. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Apr; 90(2):164–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine. Improving health professionals' access to information. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, 1989 Aug. (National Library of Medicine long range plan, report of the Board of Regents.). [Google Scholar]

- Dorsch JL. Equalizing rural health professionals' information access: lessons from a follow-up outreach project. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997 Jan; 85(1):39–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan JJ. Health information outreach: the land-grant mission. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Oct; 88(4):355–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood FB, Sahali R, Press N, Burroughs C, Mala TA, Siegel ER, Fuller SS, and Rambo N. Tribal connections health information outreach: results, evaluation, and challenges. J Med Libr Assoc. 2003 Jan; 91(1):57–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer CS. Outreach to community organizations: the next consumer health frontier. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Jul; 90(3):285–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks RA, Thiss RH, Rios GR, and Self PC. Outreach services: issues and challenges. Med Ref Serv Q. 1997 Summer; 16(2):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambo N, Zenan JS, Alpi KM, Burroughs CM, Cahn MA, and Rankin J. Public Health Outreach Forum: lessons learned. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2001 Oct; 89(4):403–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council on Disability Cultural Diversity Initiative,. Frieden L Outreach and people with disabilities from diverse cultures: a review of the literature. Washington, DC: National Council on Disability, 2003 Nov 20. [Google Scholar]

- Schools of medicine: top schools: research. U.S. News & World Report 2002 Apr 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University of Massachusetts Medical School. National research ranking: NIH FY 2000 ranking report. [Web document]. Worcester, MA: University of Massachusetts Medical School, 2004. [cited 29 Jun 2004]. <http://www.umassmed.edu/research/ranking.cfm>. [Google Scholar]

- Shedlock J. The library liaison program: building bridges with our users. Med Ref Serv Q. 1983 Spring; 2(1):61–5. [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer CS. Reference librarians' perceptions of the issues they face as academic health information professionals. J Med Libr Assoc. 2004 Apr; 92(2):226–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs CM, Wood FB. Measuring the difference: guide to planning and evaluating health information outreach. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine, 2000 Sep. [Google Scholar]

- Downing A. The consequences of offering fee-based services in a medical library. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1990 Jan; 78(1):57–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JH, King WR. The logic of strategic planning. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Feinman VJ. Five steps toward planning today for tomorrow's needs. Comput Libr. 1999 Jan; 19(1):18–21. [Google Scholar]