Abstract

Comprehensive examinations of health literacy (HL) among students in Kazakhstan are lacking. The existing literature from adult populations in Kazakhstan suggests associations between higher HL and socioeconomic and demographic factors. The HLS19-Q12 tool was used in this study to assess the HL level of 3230 students with various backgrounds. A multivariate linear regression model was used to define determinants of HL. The mean HL score for the total sample was 85.86 ± 18.67 out of 100, which indicates “excellent” level of HL. The highest HL score was in students of Health Sciences field (88.22 ± 17.53), whereas mean HL score in students of Engineering field of study was 83.27 ± 20.07, and it was 86.13 ± 18.11 for the Humanities and Social sciences field of study. The factors negatively associated with HL were region of origin, health information searching, lack of basic life support skills, smoking, self-assessment of health as bad, and missing study days. Students who smoked and used tobacco for 6 days per week had a significantly lower HL. Interaction analysis showed positive three-way interaction for male students over 19 years studying in Engineering field. Socioeconomic factors, regional disparities, and health behaviors significantly influenced HL, with lower scores observed among students from the West region, rural areas, and those with unhealthy behaviors or low socioeconomic status. The following factors were positively associated with HL in this study: field of education, affordability of medical examination and treatment, social connections and support, age, and social status. This study will allow future research and youth health promotion programs to make decisions based on the field of study and the factors that negatively and positively influence HL.

Subject terms: Population screening, Epidemiology

Introduction

Health literacy (HL), defined as the ability to access, comprehend, evaluate, and apply health information, plays a significant role in shaping individuals’ health and well-being1. The importance of HL within public health has led to the development of comprehensive assessment tools, such as the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) and the Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q), enabling cross-country comparisons2–4. The use of different tools and measures has identified that the distribution of HL levels varies across regions, influenced by social determinants such as financial status, age, and education levels5–7. As global public health increasingly focuses on HL, assessing HL among university students has become important, given their role as emerging professionals and influencers within society8,9. University students, undergoing substantial life transitions, are a key demographic for targeted HL enhancement due to their need for informed decision-making that can influence long-term health outcomes10. The transition from adolescence to adulthood presents challenges that affect lifestyle habits, such as dietary practices, mental health management, and substance use11.

Studies have consistently reported that HL among university students is frequently compromised, even among those studying the health sciences. In Portugal, a study involving 1,228 higher education students with various majors found that 82.3% had limited HL, with a mean score of 19.3 out of 50. Those students enrolled in health-related courses had higher HL levels compared to their peers in non-health-related disciplines12. Research conducted in Nepal among 469 undergraduate students reported that nearly 61% had limited HL, with 24.5% classified as having “inadequate” and 36.3% as “problematic” HL. Students from non-health-related majors were significantly more likely to have limited HL compared to those in health-related fields13. In Pakistan, a study assessing 1,590 engineering, science, art, and humanities undergraduate students revealed low HL levels, with mean scores ranging from 2.20 to 2.71 on a 5-point scale across different HL dimensions14. A study in Turkey found that 70.1% of university students across different departments lacked adequate HL15. Among 1,275 medical university students in Chongqing, China, 20.4% of the participants were found to have low HL16. A study conducted in Spain with 219 participants reported that only 36.5% of health and social care students possessed sufficient HL17.

Factors influencing HL levels among university students include demographic, academic, and socioeconomic variables. A systematic review by Kühn et al indicates that HL among students is generally insufficient, with higher scores observed among those in health-related disciplines18. Similarly, other studies suggest that students in health-related fields tend to demonstrate stronger HL competencies than their peers in non-health fields19–21. Variables such as age, gender, parental education, socioeconomic background, and academic discipline have been identified as key determinants22,23. A research on 1,526 students from various universities identified demographic and behavioral factors, including sex, family income, and health behaviors, as significant determinants of HL24. Male students often report lower HL levels compared to females, who also demonstrate greater proficiency in navigating digital health resources25. Self-esteem, health status, and year of study can be associated with limited HL among undergraduates26–28.

Psychological well-being is another factor linked to HL. Research shows that higher HL levels, supported by strong social networks, correspond to reduced depressive symptoms29–31. During the COVID-19 pandemic, HL was identified as a protective factor against anxiety, with healthcare students having fewer pandemic-related fears compared to non-health students32,33. Moreover, digital HL interventions have proven effective in enhancing health knowledge and promoting help-seeking attitudes34,35.

Despite existing research, studies focusing on HL among university students in Kazakhstan remain scarce. The country, as a regional leader in Central Asia, faces notable public health challenges despite substantial investments in the sector36–38. Limited data on HL levels and their determinants among students highlights the need for comprehensive research, particularly in the context of persistent public health challenges, such as vaccine hesitancy39. Available studies have primarily examined adult populations, identifying associations between HL and socioeconomic factors, such as education and access to healthcare40,41. However, large-scale evaluations of HL within the student population are lacking, despite evidence suggesting that HL and health behaviors are mutually influential42.

Our study addresses this gap by assessing HL among university students across various academic disciplines in Kazakhstan. We aimed to identify and analyze the factors that influence HL in this population. We believe that this study will support future research and youth health promotion programs by enabling data-driven decisions based on academic fields and the factors that positively or negatively influence HL. Additionally, the results may be valuable not only for Kazakhstan but for the broader Central Asian region.

Methods

Study design and procedure

This cross-sectional study was conducted between October and November 2023. The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: 1) a registered student at a higher educational institution or university in a Health Sciences, Humanities and Social Sciences or Engineering field of study at the undergraduate level; 2) an adult (18 years and older); and 3) a citizen of Kazakhstan. The research team sent out invitations to participate in universities containing undergraduate educational programs in Engineering, Health Sciences, and Humanities and Social Sciences fields of study. The universities of interest were located in the three main student cities of Kazakhstan, where students from all over the country study: Almaty, Astana and Karaganda. These invitations included information about the purpose of the study, the HL assessment tool, and the benefits of participation. Eight universities agreed to participate and provided access to students for the research team. Those responsible for educational work with students at these universities organized meetings of students and researchers, during which an informational meeting was held with students about the study’s purposes and how to fill out the questionnaire. Students were asked to fill out a paper-based questionnaire or an online questionnaire using QR codes in Google Forms. Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all interested students. This study was approved by the Committee on Bioethics of Karaganda Medical University No. 17 on September 20, 2022. The research was conducted according to relevant guidelines and regulations.

We aplied a stratified convenience sampling method that was designed to ensure representation across key university cities and educational fields within Kazakhstan. Initially, we identified three primary university clusters in major cities: Astana (67,211 students), Almaty (177,568 students), and Karaganda (35,924 students), which are hubs for higher education and attract students from across the country. The total number of university students in Kazakhstan during the 2023-2024 academic year was 578,23743,44.

Then, the student population was stratified by the field of study, with the following breakdown for the selected three strata: Humanities and Social Sciences (292,354 students), Health Sciences (48,342 students), and Engineering (96,684 students)45.

To determine an appropriate sample size that would provide sufficient statistical power while allowing for subgroup analyses, we considered both the total population of students within these cities and specific strata (educational fields). We calculated the sample size required for our study using Cochran’s formula for calculating a representative sample from a large population46:

|

where, “n0” is the initial sample size Z represents the Z-score corresponding to the desired confidence level (1.96 for 95% confidence), “p” is the estimated proportion of an attribute that is present in the population (assumed to be 0.5 for maximum variability), “e” is the margin of error we were willing to accept (±4%).

The calculation resulted in an initial sample size of approximately 600 respondents per field of study, after applying the finite population correction. Finally, the total sample size was distributed proportionally across the three strata based on the relative size of each stratum: Humanities and Social Sciences (292,354/437,380 × 1,800 ≈ 1,200), Health Sciences (48,342/437,380 × 1,800 ≈ 200), and Engineering (96,684/437,380 × 1,800 ≈ 400).

The final sample was adjusted to reflect actual participation rates, resulting in 3,230 students distributed as follows: 1,180 in Humanities and Social Sciences, 1,019 in Health Sciences, 1,029 in Engineering, and 2 in an uncertain field.

Measurements

Dependent variable (HL assessment tool)

The HLS19-Q12 General HL Assessment Tool was used to assess students’ HL in this study47. The HLS19-Q12 instrument used in this research was developed within “The European HL Population Survey 2019-2021 (HLS19)” of M-POHL45. The HLS19-Q12 is a 12-item questionnaire measuring comprehensive general HL in the general adult population and is part of the HLS19 family of instruments for measuring HL. The 12 items of the questionnaire were rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from “very easy” to “very difficult.” Study participants were asked to rate how easy or difficult it was for them to complete certain tasks in the questionnaire. Thus, the HLS-19Q12 is a “subjective” instrument based on perception.

The HL index score is determined by calculating the proportion of items that had valid responses ranging from 0 to 100 and were answered “very easy” or “easy”. The score is calculated using the following formula:

HL score = (number of responses marked as “easy” or “very easy”/ total number of valid responses) ×10047.

If fewer than 80% of the items contain valid responses, the score is recorded as “missing.” A higher percentage indicates a greater level of overall HL.

Students were asked to perform a general HL assessment in both the Kazakh and Russian languages. Knowledge of three languages (Russian, Kazakh and English) is common in Kazakhstan, which allowed both the research team and the involved experts to carry out a back translation into Kazakh and Russian. To assess the validity and internal consistency of the Kazakh and Russian versions of the questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated.

Independent variables

The questionnaire included sociodemographic factors such as age, sex, place of origin (rural or urban), the housing condition of the student, the field of education (humanities and social sciences, health sciences and engineering), the academic course of the respondent, the highest education level of the student and his/her parents, family completeness (parental status as having both parents or not), and self-rated financial and social status (where 1 is the lowest and 10 is the highest). The body weight of the students was assessed using the body mass index (BMI), which was calculated based on self-reported height and weight and was calculated as BMI= weight/height2.

Additionally, the questionnaire included questions about health status self-assessment, such as searching for medical information, basic life support skills, affordability of medication and medical examination, health status assessment, impact of health problems on activities and number of occurrences in use of emergency services, in visits of general practitioners (GPs) and family doctors, specialists, hospital visits and absent days at universities. Moreover, there were survey items on health behaviors, such as alcohol consumption, smoking and tobacco use, physical activity and consumption of fruits and vegetables per week.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize categorical variables by quantifying the quantity and frequency of students across sociodemographic parameters, self-assessed health status, and health behaviors. The HL was assessed using descriptive statistics, including the mean and standard deviation.

Significant differences in HL scores were compared using independent sample t tests for comparisons of means between two distinct categories and ANOVA for comparisons of means across three or more groups.

Moreover, linear regression analysis with interaction was conducted to determine the characteristics that impact HL. The independent variables of the study consisted of sociodemographic parameters, health status self-assessment, and health behaviors. The dependent variable, on the other hand, was the HL score. We used a dummy coding system to convert categorical independent variables into a numerical format suitable for linear regression. The reference category was carefully selected to ensure meaningful comparisons. This approach allowed the regression coefficients for the dummy variables to represent the effect of each category relative to the reference category.

Results

Internal consistency of the HLS19-Q12 tool and distribution of participants and comparison of HL levels according to sociodemographic determinants

The internal consistency of the Russian and Kazakh versions of the HLS19-Q12 was measured using Cronbach’s alpha. This score ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating that the questionnaire is more reliable. The Cronbach’s alpha value for the Kazakh version of the HLS19-Q12 questionnaire was 0.94 (CI [0.93-0.94]); for the Russian version, this indicator was 0.93 (CI [0.92-0.94]).

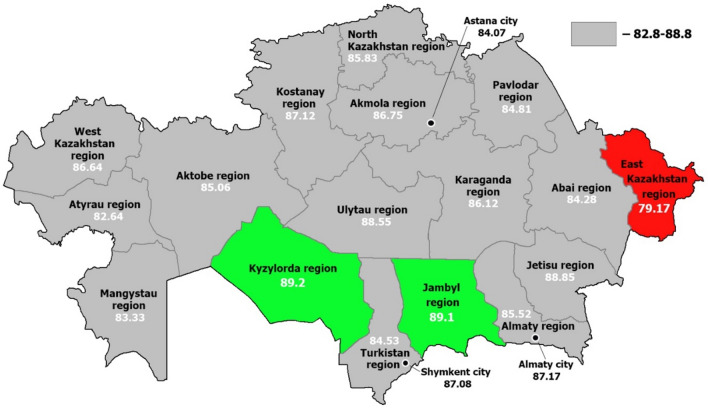

The social and demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1. Overall, 3230 respondents returned the questionnaires; of these, 1810 (56.04%) were female. The mean age of the participants was 20.14±4.76 y.o. The mean BMI was 21.48±3.56 Participants were from all 17 regions of Kazakhstan and the three large cities (Figure 1).

Table 1.

HL level according to the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents.

| Variable | Category | n (%)/mean (sd) | HL mean (sd) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 (0.03) | 0.0001 | ||

| Female | 1810 (56.03) | 86.21 (17.51) | ||

| Male | 1419 (43.93) | 85.46 (20.04) | ||

| Place of origin | 2 (0.06) | (75) | 0.012 | |

| Rural | 1047 (32.41) | 85.53 (19.52) | ||

| Urban | 2181 (67.52) | 86.04 (18.27) | ||

| Housing conditions | 6 (0.18) | 0.05 | ||

| Student residence | 714 (22.10) | 85.74 (19.03) | ||

| Parental accommodation | 1029 (31.85) | 85.54 (17.77) | ||

| Rental apartment | 661 (20.46) | 84.7 (20.43) | ||

| Field of study | 2 (0.06) | 0.0001 | ||

| Humanities and Social Sciences | 1180 (36.53) | 86.13 (18.11) | ||

| Health Sciences | 1019 (31.54) | 88.22 (17.53) | ||

| Engineering | 1029 (31.85) | 83.27 (20.07) | ||

| Year of study | 1 | 1174 (36.34) | 87 (17.05) | 0.015 |

| 2 | 757 (23.43) | 84.52 (18.99) | ||

| 3 | 759 (23.49) | 85.8 (19.36) | ||

| 4 | 454 (14.05) | 84.66 (20.41) | ||

| 5 | 63 (1.95) | 89.42 (22.95) | ||

| Highest level of education, which was completed | 3 (0.09) | 0.292 | ||

| Bachelor Level | 31 (0.95) | 92.2 (14.42) | ||

| Special Secondary Education Level | 397 (12.29) | 86.13 (19.81) | ||

| Master Level | 1 (0.03) | 83.33 (.) | ||

| Secondary Education Level | 2798 (86.62) | 85.79 (18.49) | ||

| Family completeness | 10 (0.30) | 0.250 | ||

| No | 409 (12.66) | 83.56 (19.55) | ||

| Yes | 2811 (87.02) | 86.23 (18.47) | ||

| Father’s education level | 51 (1.57) | 82.17 (19.34) | 0.027 | |

| Bachelor Level | 1258 (38.94) | 85.87 (19.19) | ||

| Special Secondary Education Level | 668 (20.68) | 84.63 (19) | ||

| Master Level | 277 (8.57) | 88.07 (15.95) | ||

| Doctoral Education Level | 53 (1.64) | 81.45 (24.39) | ||

| Secondary Education Level | 923 (28.57) | 86.54 (17.99) | ||

| Mother’s education level | 10 (0.30) | 0.017 | ||

| Bachelor Level | 1466 (45.38) | 85.9 (18.64) | ||

| Special Secondary Education Level | 559 (17.30) | 84.27 (18.98) | ||

| Master Level | 433 (13.40) | 87.32 (17.69) | ||

| Doctoral Education Level | 51 (1.57) | 80.88 (25.62) | ||

| Secondary Education Level | 711 (22.01) | 86.77 (18.06) | ||

| Social status scale | 7.86 (1.77) | |||

| Financial status scale | 7.24 (1.86) | |||

Fig. 1.

Geographic distribution of the HL scores of study participants across Kazakhstan (the map in Fig. 1 was created using the official version of the graphic editor Adobe Photoshop Ver: 20.0.0 20,180,920.r.24 2018/09/20 (manufacturer’s website: https://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop.html).

More than half of the students (2181; 67.52%) were from urban areas, with the greatest percentage residing with their parents/relatives (1029; 31.86%), followed by those with their own apartment (820; 25.39%). A total of 714 (22.11%) and 661 (20.46%) individuals lived in the dormitories and rental apartments, respectively. The vast majority of the respondents indicated that they had both parents.

The respondents were almost evenly distributed according to the field of study, with 1180 participants (36.53%) from the fields of Humanities and Social Sciences, 1019 (31.55%) from the Health Sciences field and 1029 (31.86%) from the Engineering fields of study.

The majority of the respondents (2798, 86.63%) completed secondary school, while some also had secondary special education (397, 12.29%). A small proportion of participants had completed education, with 31 participants (0.95%) falling into the category “Bachelor” and 1 participant (0.03%) having achieved a master’s level of education.

The majority of the respondents (1258, 38.94%) reported that the highest level of education achieved by their father was a bachelor’s degree, followed by a secondary education level (923, 28.57%) and a secondary special education level (668, 20.68%). A bachelor’s degree was achieved by 1466 (45.38%) of the participants’ mothers, 711 (22.01%) respondents had a secondary school education, and 559 (17.30%) respondents had a secondary special education level.

The average social status of the students was 7.86±1.77 points. At the same time, the mean financial status was 7.24±1.87.

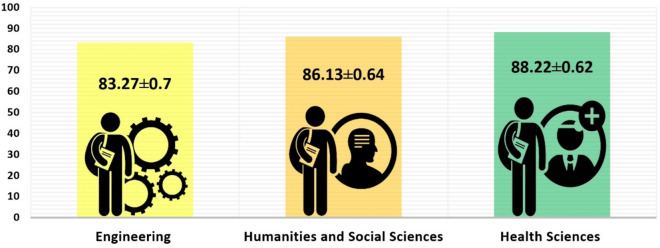

The mean HL score for the total sample was 85.86±18.67, which indicates excellent level of HL. The highest HL score was in students of Health Sciences field (88.22±17.53), whereas mean HL score in students of Engineering field of study was 83.27±20.07, and it was 86.13±18.11 for the Humanities and Social sciences field of study (Figure 2).Fig. 2Distribution of HL levels of study participants by field of study, mean scores ± 2SE.Fig. 2Distribution of HL levels of study participants by field of study, mean scores ± 2SE.Fig. 2Distribution of HL levels of study participants by field of study, mean scores ± 2SE.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of HL levels of study participants by field of study, mean scores ± 2SE.

The mean HL score was significantly greater for female students (p=0.0001), participants from urban areas (p=0.012), students in health-related fields of study (p=0.0001), and senior students (p= 0.015). In addition, respondents whose fathers’ or mothers’ education level was reported as ‘master’ had significantly greater levels of general HL (p=0.027, p=0.017, respectively).

HL level according to self-assessment of health status and health behavior of students

The majority of respondents who reported searching for health information (2381, 73.7%) demonstrated a significantly greater level of general HL than did those, who answered otherwise, with a p-value of 0.0001 (Table 2). Participants previously trained in basic life support skills (1743, 54%) had significantly greater levels of general HL (p=0.0001).

Table 2.

HL level according to self-assessment of respondent health status.

| Variable | Category | n (%)/mean (sd) | HL mean (sd) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health information search | 4 (0.10) | 68.75 (47.32) | 0.0001 | |

| No | 845 (26.20) | 85.03 (20.92) | ||

| Yes | 2381(73.7) | 86.19 (17.73) | ||

| Basic life support skills | 9(0.2) | 73.96 (34.05) | 0.0001 | |

| No | 1478(45.8) | 83.15 (19.89) | ||

| Yes | 1743(54) | 88.24 (17.14) | ||

| Affordability of medication | 8(0.2) | 79.17 (33.03) | 0.0001 | |

| Easy | 2145(66.4) | 86.47 (17.15) | ||

| Difficult | 442(13.7) | 77.55 (25.05) | ||

| Very easy | 600(18.6) | 91 (14.17) | ||

| Very difficult | 35(1.1) | 67.86 (30.86) | ||

| Affordability of medical examinations and treatments | 3(0.1) | 55.56 (48.83) | 0.0001 | |

| Easy | 2007(62.1) | 87.89 (15.65) | ||

| Difficult | 698(21.6) | 77.77 (24.14) | ||

| Very easy | 452(14) | 92.11 (12.52) | ||

| Very difficult | 70(2.2) | 69.76 (29.63) | ||

| Number of close individuals to the respondent | 24(1.6) | 82.5 (23.4) | 0.0001 | |

| 1 or 2 | 1386(42.9) | 84.63 (20.25) | ||

| 3 to 5 | 1205(37.3) | 86.37 (16.69) | ||

| 6 or more | 444(13.7) | 89.77 (15.78) | ||

| none | 171(5.3) | 82.26 (23.06) | ||

| General health status assessment | 2(0.1) | 33.34 (47.14) | 0.0001 | |

| Bad | 64(2) | 75.13 (19.27) | ||

| Good | 1670(51.7) | 87.68 (16.92) | ||

| Fair | 765(23.7) | 79.8 (21.72) | ||

| Very bad | 7(0.2) | 78.57 (15.85) | ||

| Very good | 722(22.4) | 89.27 (16.88) | ||

| Long-term illness or health problem | 1(0) | 0.001 | ||

| No | 2518(78) | 86.79 (18.01) | ||

| Yes | 711(22) | 82.71 (20.32) | ||

| Impact of health problems on activities (limitation level) | 4(0.1) | 58.33 (42.49) | 0.0001 | |

| Limited but not severely | 866(26.8) | 82.32 (20.16) | ||

| No Health Problem | 1378(42.7) | 87.92 (17.06) | ||

| Not limited at all | 982(30.4) | 86.23 (18.86) | ||

| Emergency service usage (n) | 0.69 (1.47) | |||

| GP or family doctor visits (n) | 1.69 (2.40) | |||

| Medical or surgical specialist visits (n) | 1.02 (1.89) | |||

| Hospital inpatient visits (n) | 0.12 (0.43) | |||

| Hospital day patient visits (n) | 0.75 (1.83) | |||

| Absent days in university due to health problems | 2.87 (5.59) | |||

Most students indicated easy affordability of medication (2145, 66.4%), and medical examinations and treatments (2007, 62.1%). General HL was significantly greater in those students who answered that it was ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ for them to afford medication and medical examination and treatments (p=0.0001).

Students who reported having 6 or more close individuals whom they could rely on in case of serious personal problems demonstrated a significantly greater level of general HL (p = 0.0001). Those respondents who self-assessed their health as ‘good’ or ‘very good’ had a greater level of general HL than did those who answered differently (p=0.0001).

Participants who denied long-term illness or health problems had significantly greater levels of general HL (p=0.0001). Respondents who did not have health problems or limitations had a higher level of general HL (p=0.0001).

The average usage of emergency services over the last 24 months was 0.69, with a standard deviation of 1.47. Respondents, on average, visited a GP or family doctor approximately 0.69±1.47 times in the last 12 months. Students, on average, visited a medical or surgical specialist approximately 1.69±2.40 times in the last 12 months. The students were admitted to the hospital as an inpatient approximately 0.12±0.43 times in the last 12 months. The respondents had been to the hospital as a day patient approximately 0.75±1.83 times in the last 12 months. Approximately 2.87±5.59 days of education were missed in the past 12 months due to health problems.

The majority of the participants indicated that they had never smoked (2835, 87.8%) and had never consumed alcohol (2898, 89.7%). The majority of the respondents (642, 19.9%) had never engaged in any kind of physical activity or were involved in less than one day per week (571, 17.7%).

Certain health behaviors of the respondents, such as eating habits, were linked to HL (Table 3). Thus, those respondents who consumed fruits and vegetables 7 times per week had the significantly higher level of general HL (p=0.037). Those who never smoked had one of the highest HL scores (p=0.000). There was no statistically significant difference in the mean HL score between the respondents according to their physical activity and alcohol consumption.

Table 3.

HL according to the health behavior of the study subjects.

| Variable | Category | n (%)/mean (sd) | HL mean (sd) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking and Tobacco Use per Week | 3(0.1) | 0.004 | ||

| 1 day | 36(1.1) | 85.42 (18.41) | ||

| 2 days | 20(0.6) | 81.58 (30.12) | ||

| 3 days | 25(0.8) | 86 (17.96) | ||

| 4 days | 9(0.3) | 87.04 (11.11) | ||

| 5 days | 10(0.3) | 84.17 (15.44) | ||

| 6 days | 14(0.4) | 72.02 (18.67) | ||

| 7 days | 156(4.8) | 81.45 (18.89) | ||

| Less than one day per week | 122(3.8) | 83.13 (20.31) | ||

| Never | 2835(87.8) | 86.38 (18.41) | ||

| Alcohol Consumption per Week | 7(0.2) | 0.253 | ||

| 1 day | 22(0.7) | 86.74 (20.36) | ||

| 2 days | 8(0.2) | 85.42 (15.27) | ||

| 3 days | 4(0.1) | 83.33 (6.81) | ||

| 4 days | 1(0) | 75 (.) | ||

| 5 days | 1(0) | 75 (.) | ||

| 6 days | 3(0.1) | 83.34 (14.43) | ||

| 7 days | 1(0) | 41.67 (.) | ||

| Less than one day per week | 285(8.8) | 84.24 (17.11) | ||

| Never | 2898(89.7) | 86.09 (18.76) | ||

| Physical activity per week | 5(0.2) | 66.67 (40.4) | 0.092 | |

| 1 day | 284(8.8) | 83.89 (18.87) | ||

| 2 days | 249(7.7) | 85.27 (18.68) | ||

| 3 days | 409(12.7) | 85.49 (17.17) | ||

| 4 days | 183(5.7) | 86.02 (15.6) | ||

| 5 days | 294(9.1) | 84.76 (17.94) | ||

| 6 days | 125(3.9) | 86.47 (15.14) | ||

| 7 days | 468(14.5) | 84.76 (17.75) | ||

| Less than one day per week | 571(17.7) | 86.92 (19.05) | ||

| Never | 642(19.9) | 87.57 (21.07) | ||

| Consumption of fruits and vegetables, dietary habits per week | 5(0.1) | 47.92 (38.11) | 0.037 | |

| 1 day | 334(10.3) | 84.03 (20.4) | ||

| 2 days | 260(8) | 83.53 (18.84) | ||

| 3 days | 372(11.5) | 85.66 (16.14) | ||

| 4 days | 284(8.8) | 86.06 (16.73) | ||

| 5 days | 336(10.4) | 85.29 (18.82) | ||

| 6 days | 175(5.4) | 86.26 (16.27) | ||

| 7 days | 659(20.4) | 87.72 (16.08) | ||

| Less than one day per week | 559(17.3) | 85.65 (21.12) | ||

| Never | 246(7.6) | 87.53 (22.14) |

Factors affecting HL

A multiple regression analysis with interactions examining the impact of age, gender, and educational field on HL Score revealed no significant main effects for age, gender, or educational field independently (Figure 3). However, significant interaction effects were observed: students older than 19 years combined with studying in Engineering field showed a negative impact on HL, as did male students in Engineering field of study. Interestingly, a three-way interaction between being male, older than 19, and studying in Engineering field positively influenced HL (intercept = 85.46, coefficient = 7.7, p-value < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Interaction effects of factors on HL score.

An analysis of the influence of socioeconomic indicators, students’ region of origin, and health behaviors on HL revealed several significant findings. The West region exhibited a negative coefficient (-40.27) with a p-value < 0.05, indicating that students from this region have significantly lower HL Scores compared to the reference region. Furthermore, interaction effects demonstrated that non-smoking students from the South and East regions scored higher on HL, with coefficients of 38.75 and p-values < 0.05 for both regions. Students from rural areas of West Kazakhstan who neither smoke nor drink exhibit significantly lower HL (coefficient = -42.39, p-value < 0.05) compared to their smoking and drinking counterparts from urban areas in other regions of Kazakhstan (coefficient = -68.82, p-value < 0.05). Additionally, students from rural areas in the Central, North, and South regions of Kazakhstan who do not follow a healthy diet have lower HL scores (coefficients = -3.34, p-value < 0.05; -2.27, p-value < 0.05; -1.99, p-value < 0.05) compared to students from urban areas in other regions who maintain a healthy diet. Students from the Central Kazakhstan who perceive their social and material status as low, coupled with a lack of physical activity, exhibit significantly lower levels of HL compared to their peers (coefficient = -26.63, p-value < 0.05; coefficient = -47.12, p-value < 0.05, respectively). This finding underscores the combined impact of socioeconomic challenges and physical inactivity on HL outcomes. Additionally, students from Central Kazakhstan who consume alcohol show even more pronounced deficits in HL, with notably low values recorded (coefficient = -58.69, p-value < 0.001).

Regression analysis demonstrated that the mean HL score was associated with the range of factors (Table 4). Thus, participants who studied in the Humanities and Social Sciences and Health Sciences had higher mean HL scores than did students in the Engineering fields of study (B=2.27, p=0.008 and B=3.86, p=0.0001, respectively). HL was greater for those respondents who indicated that the procedure was very easy (B=15.41, p=0.0001), easy (B=13.03, p=0.0001) or difficult to afford medical examinations and treatments (B=5.48, p=0.038) than for those respondents who indicated that the affordability of those procedures was very difficult. The students who reported having 6 or more close individuals had 5.32 points greater mean HL than did those who did not have any close persons (p=0.002). The students who reported having 3-5 close individuals had 3.08 points greater mean HL scores than those who did not have any close persons (p=0.049).

Table 4.

Determinants of HL.

| Parameter | B | Std error | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| East Kazakhstan region (ref – West Kazakhstan Region) | − 9.47 | 4.21 | 0.025 |

| Humanities and Social Sciences (ref—Engineering) | 2.27 | 0.86 | 0.008 |

| Health Sciences Universities (ref—Engineering) | 3.86 | 1.01 | 0.0001 |

| Not engaged to search health information (ref—Yes) | − 1.98 | 0.83 | 0.017 |

| Lack of basic life support skills (ref—Yes) | − 3.97 | 0.69 | 0.0001 |

| Easy affordability of medical examinations and treatments (ref – Very difficult) | 13.03 | 2.64 | 0.0001 |

| Difficult affordability of medical examinations and treatments (ref – Very difficult) | 5.48 | 2.64 | 0.038 |

| Very easy affordability of medical examinations and treatments (ref – Very difficult) | 15.41 | 2.98 | 0.0001 |

| 3–5 close individuals (ref – No close people) | 3.08 | 1.57 | 0.049 |

| 6 or more close individuals (ref – No close people) | 5.32 | 1.71 | 0.002 |

| 6 days of smoking and tobacco use per week (ref—Never) | − 10.08 | 4.73 | 0.033 |

| Bad assessment of health status (ref – Very good) | − 6.72 | 2.70 | 0.013 |

| Fair assessment of health status (ref – Very good) | − 4.88 | 1.17 | 0.0001 |

| Age | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.01 |

| Absent days in university due to health problems | − 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Social status scale | 0.50 | 0.23 | 0.034 |

Compared to those who were from West Kazakhstan region, students from East Kazakhstan region had, on average, a HL that was 9.47 points lower, with a statistically significant p-value of 0.025. The respondents who did not actively search for health information had a HL scores 1.98 points lower than those who did actively search for health information, with a statistically significant p-value of 0.017. Students who did not have basic life support skills training had a 3.97-point lower HL than did those who had such skills, with a statistically significant p-value of 0.0001.

On average, students who smoked and used tobacco for 6 days per week had a significantly lower HL (10.08 points) than those students who had never smoked, with a p-value of 0.033. Students who assessed their health status as bad in comparison with very good assessment of health had a 6.72 points lower HL, with a statistically significant p-value of 0.013. A highly statistically significant difference was 4.88 points lower for students who assessed their health status as fair than for those who assessed it as very good (p-value of 0.0001).

Each one-unit increase in age was associated with a 0.24-point increase in HL, with a p-value of 0.01. Each one-day increase in absent days in university due to health problems was associated with a 0.17-point decrease in HL, with a statistically significant p-value of 0.01. Each one-unit increase in the social status scale is associated with a 0.50-point increase in HL, with a statistically significant p-value of 0.034.

Discussion

This large-scale study of assessing HL among university students in different fields is the first in Kazakhstan. Approximately two-thirds of the students from urban regions participated in the study. This proportion nearly reflects the demographic structure of the overall population, where urban inhabitants similarly make up approximately 62.1% of the people. Moreover, gender disparities in the sample overall, were in line with the demographic situation of the Kazakhstani population43. The respondents in this study were distributed across fields of education in approximately equal proportions.

Students whose parents had a master’s degree had a greater mean HL than did the other students. Moreover, these results were supported by several studies48,49.

Students with basic life support skills had a greater mean HL than did those without such support. This can be related to the potential advantages of participating in such courses, which encompass improved availability of health knowledge and experience in managing the healthcare system. Furthermore, nearly nine out of the ten students reported not consuming alcohol or smoking throughout the week.

Despite the expectation that students who eat more fruits and vegetables will have higher levels of HL50, in our study, it was interesting to note that students who consumed fruits and vegetables every day, as well as those who never consumed them, showed greater mean HL in comparison with others.

An adequate level of HL allows university students to make correct decisions about their health. Although a recent meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies assessing HL among university students reported that the level of general HL among university students appears to be insufficient and needs to be improved16, our study revealed that 84.27% of students had adequate and excellent levels of HL.

Based on the results of multiple linear regression, our study identified the following determinants of general HL: students’ region of origin, field of education, basic life support skills, affordability of medical examinations and treatments, number of close people, health self-assessment, age, missed days at university because of health problems, and self-assessment of social status.

Starting from the determinants associated with higher levels of HL, in our study, training in Humanities and Social Sciences, and Health Science education programmes were the determinants associated with increased HL. This finding is consistent with previous reports that higher levels of HL are associated with training in health-related sciences17,23,51. One reason for this finding may be that topics, disciplines, or entire courses related to HL are taught mostly in Health Sciences universities. Thus, a systematic review of studies on approaches to teaching HL at universities revealed that two-thirds of the studies included in the review were from medical schools52. In our study, socioeconomic factors such as older age, financial ability to easily afford medications, treatment and medical examinations as needed, strong social connections and high social status were also significantly associated with higher scores of HL. Many studies confirm the significant influence of socioeconomic factors, particularly family income, on the level of HL16,53,54. Moreover, Oridanigo et al. reported that family income is an associated factor for the affordability of medications55. Klinger et al. reported that social support has a significant positive effect on HL in young people, which also supports our findings56.

Moving to the factors that were associated with lower HL in our study, on average, students from the East Kazakhstan region had lower scores of HL, which is most likely because the majority of students from these regions were from a rural community. In turn, studies report that rural areas have a negative impact on HL among young people, particularly in developing countries such as Kazakhstan57,58. Challenges that can be encountered in rural communities that negatively impact HL include limited access to health services, limited resources, low literacy levels, cultural and language barriers, financial constraints and a low level of digitalization.

As expected in this study, students (approximately a quarter of respondents) who reported that they had never sought health information and had never trained in basic life support skills (approximately half of respondents) had significantly lower scores of HL. The level of HL is an important determinant in the context of health information seeking. Higher HL and greater access to technological devices were associated with higher levels of health-related online information seeking behavior. In other words, the higher the level of HL is, the more likely the respondent is to use the Internet to search for health-related information and interact with the healthcare system, which influences the management of their own health59. The number of study days missed due to health problems among students was also a determinant associated with a decreasing score of HL. This was inextricably linked to how respondents assessed their health. This study revealed that students who rated their health as bad had significantly lower levels of HL. Although self-assessment of health as good is usually positively associated with HL60, such a relationship was not observed in our study.

The findings of this study highlight complex interactions between demographic, educational, and socioeconomic factors and HL among Kazakhstani students. While age, gender, and educational field alone did not significantly influence HL scores, notable interaction effects were observed. A three-way interaction revealed that male students over 19 years studying engineering exhibited improved HL, possibly due to factors like academic maturity or exposure to targeted curricula. These results underscore the importance of examining interaction effects to uncover nuanced patterns in HL61. Regional disparities and health behaviors significantly influenced HL outcomes. Students from the West region had notably lower HL compared to other regions, highlighting geographic inequities in health education. Non-smoking students from the South and East scored higher, potentially reflecting a link between healthier behaviors and better health awareness. In contrast, rural students from West Kazakhstan who neither smoked nor drank showed significantly lower HL compared to urban counterparts who engaged in these behaviors, emphasizing the role of urbanization and access to information. These findings align with research identifying rurality as a barrier to HL57. Socioeconomic and lifestyle factors further shaped HL levels. Rural students in the central, northern, and southern regions who did not follow healthy diets had lower scores than urban peers with better nutrition, reinforcing the link between diet and health awareness. Students from central Kazakhstan with low perceived social and material status or insufficient physical activity also displayed markedly lower HL. These findings reflect established associations between low socioeconomic status, sedentary lifestyles, and poor HL. Alarmingly, alcohol consumption was associated with the lowest HL levels, highlighting the detrimental impact of unhealthy behaviors62.

Although this study is the first to examine HL and its determinants among university students from various fields of study and has a relatively large sample size, it has a number of limitations. Thus, in our study, the number of junior students involved was greater compared to senior ones. The reason is that the number of senior students, especially at Health Science universities, is significantly decreasing for various reasons, particularly for academic performance. Additionally, the duration of undergraduate study at Health Sciences faculties in Kazakhstan is 5 years, while that at other fields of studies is 4 years. This explains the low number of 5th-year students. Like many subjective instruments, the HLS19-Q12 tool’s subjective rating scale makes it challenging to evaluate confirmation bias, which is linked to respondents’ propensity to assert skills and knowledge that they do not actually possess.

The sample may have also been biased, as it is likely that only the most motivated and engaged students participated in the survey. This potential selection bias could have skewed the findings and reduced the representativeness of the overall student population. The convenience sampling approach may not fully capture the diversity of the student population in Kazakhstan. While the stratification by field of study aimed to capture differences in HL across educational contexts, the selected fields may not fully represent the diversity of academic programs in Kazakhstan. Students in other fields, such as natural sciences or arts, were not included. Another limitation is the cross-sectional design of the study, which restricts the ability to infer causal relationships between health attitudes and HL. To better understand temporal relationships and causality, future studies should adopt longitudinal designs. Lastly, the study did not account for several potential confounding variables, such as access to healthcare and prior experiences with the healthcare system, both of which are known to significantly influence HL and health-related attitudes.

In conclusion, this study provides insights into the HL levels and their determinants among university students across various academic disciplines in Kazakhstan. The findings reveal some disparities in HL based on sociodemographic factors, health behaviors, and regional backgrounds. Higher HL levels were associated with students in health-related fields, those with strong social support networks, and individuals reporting good self-assessed health. Students from rural areas, those with unhealthy behaviors, and those with lower socioeconomic status showed lower HL levels. By identifying key determinants of HL, this study may support the development of evidence-based policies and programs aimed at improving HL and, consequently, enhancing health outcomes among youth. Our findings may have broader relevance for neighboring Central Asian countries facing similar public health challenges, highlighting the need for region-specific strategies to address HL disparities effectively.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, G.K. and A.T.; methodology, Zh.B.; validation, K.N., O.Zh. and Zh.B.; formal analysis, K.N.; investigation, O.Zh.; resources, Zh.D.; data curation, A.T., O.Zh., N.Y., Zh.B.; writing—original draft preparation,G.K., A.T., Zh.B., Zh.D., N.Y., K.N., O.Zh.; visualization, N.Y.; supervision, A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MINISTRY OF SCIENCE AND HIGHER EDUCATION OF THE REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN, grant number AP19679263.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.L, N.-B., AM, P. & DA, K. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. 10.17226/10883. (2004).

- 2.Nakayama, K. et al. Comprehensive health literacy in Japan is lower than in Europe: A validated Japanese-language assessment of health literacy. BMC Public Health15, 1–12 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osborne, R. H. et al. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health13(658), 1–17 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sørensen, K. et al. Measuring health literacy in populations: illuminating the design and development process of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). BMC Public Health13(948), 1–10 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sørensen, K. et al. Health literacy in Europe: comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public Health25, 1053–1058 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Der Heide, I. et al. The relationship between health, education, and health literacy: results from the Dutch Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey. J. Health Commun.18(Suppl 1), 172–184 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erdei, R. J., Barth, A., Fedor, A. R. & Takács, P. Measuring the factors affecting health literacy in East Hungary – Health literacy in the adult population of Nyíregyháza city. Kontakt20, e375–e380 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altin, S. V., Finke, I., Kautz-Freimuth, S. & Stock, S. The evolution of health literacy assessment tools: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 14, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Vamos, S. et al. Exploring Health Literacy Profiles of Texas University Students. Heal. Behav. Policy Rev.3, 209–225 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uysal, N., Ceylan, E. & Koç, A. Health literacy level and influencing factors in university students. Health Soc. Care Commun.28, 505–511 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulye, T. P. et al. Trends in adolescent and young adult health in the United States. J. Adolesc. Health45, 8–24 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosário, J., Dias, S. S., Dias, S. & Pedro, A. R. Health literacy and its determinants among higher education students in the Alentejo region of southern Portugal—A cross-sectional survey. PLoS One19(9), 1–20 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhusal, S. et al. Health literacy and associated factors among undergraduates: A university-based cross-sectional study in Nepal. PLOS Global Public Health10.1371/journal.pgph.0000016 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rehman, A. ur, Bin Naeem, S. & Faiola, A. The prevalence of low health literacy in undergraduate students in Pakistan. Heal. Inf. Libr. J. 40, 103–108 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Acar, A. K., Savcı, S., Kahraman, B. Ö. & Tanrıverdi, A. Comparison of E-Health Literacy, Digital Health and Physical Activity Levels Of University Students In Different Fields. J. Basic Clin. Heal. Sci.8, 380–389 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang, Y. et al. Exploring Health Literacy in Medical University Students of Chongqing, China: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLOS One11, e0152547 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juvinyà-Canal, D. et al. Health Literacy among Health and Social Care University Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, Vol. 17, Page 2273 17, 2273 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Kühn, L. et al. Health Literacy Among University Students: A Systematic Review of Cross-Sectional Studies. Front. Public Health9, 680999 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sukys, S., Cesnaitiene, V. J. & Ossowsky, Z. M. Is health education at university associated with students’ health literacy? evidence from cross-sectional study applying HLS-EU-Q. BioMed Res. Int.10.1155/2017/8516843 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cal, A. et al. Health Literacy Level of First-year University Students: A Foundation University Study. J. Clin. Pract. Res.44, 216–221 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallè, F. et al. Are Health Literacy and Lifestyle of Undergraduates Related to the Educational Field? An Italian Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health10.3390/ijerph17186654 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhamantayev, O., Nukeshtayeva, K., Kayupova, G., et al. (2023). Mapping the terrain: A comprehensive exploration of health literacy among youth. J CLIN MED KAZ, 20(6), 12–22. 10.23950/jcmk/13917

- 23.Rababah, J. A., Al-Hammouri, M. M., Drew, B. L. & Aldalaykeh, M. Health literacy: Exploring disparities among college students. BMC Public Health19, 1–11 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vozikis, A., Drivas, K. & Milioris, K. Health literacy among university students in Greece: determinants and association with self-perceived health, health behaviors and health risks. Arch. Public Health72, 15 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dadaczynski, K. et al. Digital Health Literacy and Web-Based Information-Seeking Behaviors of University Students in Germany during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-sectional Survey Study. J. Med. Int. Res.23, e24097 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans, A.-Y., Anthony, ; Edusei & Gabriel, G. Comprehensive Health Literacy Among Undergraduates: A Ghanaian University-Based Cross-Sectional Study. HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice 3, 227–237 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Hsu, W., Chiang, C. & Yang, S. The effect of individual factors on health behaviors among college students: The mediating effects of eHealth literacy. J. Med. Int. Res.16, e3542 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holt, K. A., Overgaard, D., Engel, L. V. & Kayser, L. Health literacy, digital literacy and eHealth literacy in Danish nursing students at entry and graduate level: A cross sectional study. BMC Nurs.19, 1–12 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen, H. T. et al. Fear of COVID-19 Scale—Associations of Its Scores with Health Literacy and Health-Related Behaviors among Medical Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, Vol. 17, Page 4164 17, 4164 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Rababah, J. A., Al-Hammouri, M. M. & Drew, B. L. The impact of health literacy on college students’ psychological disturbances and quality of life: A structural equation modeling analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes18, 1–9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong, Y., Schroeder, E., Gao, Y., Guo, X. & Gu, Y. Social Support, Health Literacy and Depressive Symptoms among Medical Students: An Analysis of Mediating Effects. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, Vol. 18, Page 633 18, 633 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Frings, D. et al. Differences in digital health literacy and future anxiety between health care and other university students in England during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health22, 1–9 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, S., Cui, G., Kaminga, A. C., Cheng, S. & Xu, H. Associations Between Health Literacy, eHealth Literacy, and COVID-19-Related Health Behaviors Among Chinese College Students: Cross-sectional Online Study. Journal of medical Internet research 23, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Kurki, M. et al. Digital mental health literacy -program for the first-year medical students’ wellbeing: a one group quasiexperimental study. BMC Med. Educ.21, 1–11 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aydınlar, A. et al. Awareness and level of digital literacy among students receiving health-based education. BMC Medical Education 2024 24:1 24, 1–13 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Kazakhstan 2041: The Next Twenty-Five Years. https://isdp.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/2016-cornell-engvall-starr-kazakhstan-2041-1.pdf

- 37.Kazakhstan: Tested by Transition | 6. Relations with other Central Asian states. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2019/11/kazakhstan-tested-transition/6-relations-other-central-asian-states

- 38.Gulis, G. et al. Population Health Status of the Republic of Kazakhstan: Trends and Implications for Public Health Policy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, Vol. 18, Page 12235 18, 12235 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Bolatov, A. K., Seisembekov, T. Z., Askarova, A. Z. & Pavalkis, D. Barriers to COVID-19 vaccination among medical students in Kazakhstan: development, validation, and use of a new COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale. Hum.Vacc. Immunotherapeutics17, 4982–4992 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kayupova, G. et al. Health Literacy among Visitors of District Polyclinics in Almaty Kazakhstan. Iranian J. Public Health46, 1062 (2017). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duong, T. V. et al. Measuring health literacy in Asia: Validation of the HLS-EU-Q47 survey tool in six Asian countries. J. Epidemiol.27, 80–86 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baisunova, G., Baisunova, G. S., Turdaliyeva, B. S. & Tulebayev, K. A. Study of health literacy and health behavior in Almaty City and Almaty Region, Kazakhstan: Gaukhar Baisunova. European Journal of Public Health 26, (2016).

- 43.Agency for Strategic planning and reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan Bureau of National statistics - Main. https://stat.gov.kz/en/

- 44.Bureau of National Statistics of the Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan. https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/stat/press/news/details/476731?lang=kk

- 45.Statistics of education, science and innovation. https://stat.gov.kz/ru/industries/social-statistics/stat-edu-science-inno/publications/3921/

- 46.Bartlett, J. E. II, Kotrlik, J. W., & Higgins, C. C. Determining appropriate sample size in survey research. Organizational Research. Information Technology, Learning, and Performance Journal, Vol. 19 (1), 43–50, https://www.opalco.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Reading-Sample-Size1.pdf (2001).

- 47.The HLS19 Consortium of the WHO Action Network M -POHL. The HLS19-Q12 Instrument to measure General Health Literacy (Austrian National Public Health Institute, Vienna, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarhan, M. B. A. et al. Exploring health literacy and its associated factors among Palestinian university students: a cross-sectional study. Health Promot. Int.36, 854–865 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eyimaya, A. Ö., Özdemir, F., Tezel, A. & Apay, S. E. Determining the healthy lifestyle behaviors and e-health literacy levels in adolescents. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP55, e03742 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oberne, A., Vamos, C., Wright, L., Wang, W. & Daley, E. Does health literacy affect fruit and vegetable consumption? An assessment of the relationship between health literacy and dietary practices among college students. J. Am. College Health70, 134–141 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rita Pedro Pedro, A. A. et al. Health literacy in higher education students: findings from a Portuguese study. Eur J Public Health 32, (2022).

- 52.Røe, Y., Torbjørnsen, A., Stanghelle, B., Helseth, S. & Riiser, K. Health Literacy in Higher Education: A Systematic Scoping Review of Educational Approaches. Pedagogy Health Promot (2023).

- 53.Tang, C., Wu, X., Chen, X., Pan, B. & Yang, X. Examining income-related inequality in health literacy and health-information seeking among urban population in China. BMC Public Health19, 1–9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma, T. et al. Health Literacy Mediates the Association Between Socioeconomic Status and Productive Aging Among Elderly Chinese Adults in a Newly Urbanized Community. Front Public Health9, 647230 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mathewos Oridanigo, E., Beyene Salgedo, W. & Gebissa Kebene, F. Affordability of Essential Medicines and Associated Factors in Public Health Facilities of Jimma Zone Southwest Ethiopia. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm Sci10.1155/2021/6640133 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klinger, J., Berens, E. M. & Schaeffer, D. Health literacy and the role of social support in different age groups: results of a German cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health23, 1–12 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aljassim, N. & Ostini, R. Health literacy in rural and urban populations: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns103, 2142–2154 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pailaha, A. D. Public health nursing: Challenges and innovations for health literacy in rural area. Public Health Nurs.40, 769–772 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sundell, E., Wångdahl, J. & Grauman, Å. Health literacy and digital health information-seeking behavior – a cross-sectional study among highly educated Swedes. BMC Public Health22, 1–10 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bíró, É., Vincze, F., Nagy-Pénzes, G. & Ádány, R. Investigation of the relationship of general and digital health literacy with various health-related outcomes. Front Public Health11, 1229734 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kickbusch, I., Pelikan, J. M., Apfel, F., & Tsouros, A. D. Health Literacy: The Solid Facts. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe (2013). https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/326432.

- 62.Suka, M. et al. Relationship between health literacy, health information access, health behavior, and health status in Japanese people. Patient Educ. Counseling98(5), 660–668 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.