Abstract

There are few in vitro models available to study microglial physiology in a homeostatic context. Recent approaches include the human induced pluripotent stem cell model, but these can be challenging for large-scale assays and may lead to batch variability. To advance our understanding of microglial biology while enabling scalability for high-throughput assays, we developed an inducible immortalized murine microglial cell line using a tetracycline expression system. The addition of doxycycline facilitates rapid cell proliferation, allowing for population expansion. Upon withdrawal of doxycycline, this monoclonal microglial cell line differentiates, resembling in vivo microglial physiology as demonstrated by the expression of microglial genes, innate immune responses, chemotaxis, and phagocytic abilities. We utilized live imaging and various molecular techniques to functionally characterize the clonal 2E11murine microglial cell line. Transcriptomic analysis showed that the 2E11 line exhibited characteristics of immature, proliferative microglia during doxycycline induction, and further differentiation led to a more homeostatic phenotype. Treatment with transforming growth factor-β modified the transcriptome of the 2E11 cell line, affecting cellular immune pathways. Our findings indicate that the 2E11 inducible immortalized cell line is a practical and convenient tool for studying microglial biology in vitro.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-87543-1.

Keywords: Inducible immortalized cell line, Murine microglia, Phagocytosis, Chemotaxis, Cytokines, Transcriptomics

Subject terms: Cell biology, Mechanisms of disease

Introduction

In recent decades, various in vitro models ofmicroglia have been developed, including primary dissociated cell cultures and human induced stem cell-derived microglial-like cells (iMGLs). While these models aim to replicate the characteristics and developmental processes of microglia in vivo, they come with several limitations. A significant challenge is that microglia tend to lose their specific expression profiles with prolonged culture time1. Cultured microglia often become more activated and amoeboid, exhibiting increased phagocytic activity that is heavily influenced by the composition of the culture media2. Many of these artificial characteristics can be reversed through engraftment into microglia-deficient brains, indicating that CNS-specific signals are essential for maintaining microglial identity and promoting a homeostatic phenotype3,4.

Microglial cell lines derived from mouse, rat, and human sources are typically immortalized through viral transduction using various oncogenes. These available cell lines offer advantages such as ease of maintenance and unlimited proliferation potential. The most commonly used cell line, BV-2, is derived from neonatal primary microglia transduced with v-raf/v-myc carrying J2 retroviruses, and expresses macrophage markers like MAC1 and MAC25. BV-2 cells are well-studied, particularly regarding their phagocytic abilities and inflammatory marker expression in response to LPS stimulation. However, they are also susceptible to dedifferentiation and changes in their microglial phenotype. Due to the ongoing expression of oncogenic genes, BV2 cells are often viewed as activated microglia-like cells with rapid proliferation capabilities, which complicates the assessment of functions that reflect a more homeostatic state.

Additionally, significant batch effects can arise in primary microglial cultures due to the genetic background of the mice or the purity of microglial isolation. In response to these issues, we propose a method for the inducible immortalization of murine microglia, allowing for the rapid expansion of single-cell colonies while minimizing the activation associated with fast-growing microglial populations. This approach facilitates high-throughput drug screening for gene targets, eliminating confounding factors like isolation purity and batch effects.

Methods

Molecular cloning and lentiviral production

A mutant form of HRAS G12V, containing a P2A sequence, was synthesized by GenScript based on the published HRAS G12V sequence6. pUC57 plasmid containing HRAS G12V was subsequently cloned into a lentiviral vector with a tetracycline response element with CMYC T58A7(19775, Addgene) using BsaBI and Xba1 restriction enzymes. The lentiviral TET-O-CMYC T58A-P2A-HRAS G12V and rTTA plasmids7 (19780, Addgene) were amplified using SURE2 Super competent cells (200152, Agilent) to produce stable plasmids. The cloned plasmid was sequenced to confirm the correct insertion. Lentivirus stocks were generated by co-transfecting HEK 293FT cells with the lentiviral TET-O-CMYC T58A-P2A-HRAS G12V and three packaging plasmids (pLP1, pLP2, and VSVg) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen 18324012) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Lentiviral particles were harvested 2–3 days post-transfection after a complete media change 24 h after transfection, concentrated by ultracentrifugation, and stored at −80 °C.

Microglia culture and lentiviral transduction

All animal procedures adhered to the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Boston University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Primary mouse microglia were isolated from CD1 E17.5–18.5 embryos (Charles River Laboratory) using the Embryonic Neural Dissociation Kit microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec 130-093-231) and CD11B microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec 130-093-634) following the manufacturer’s protocol as previously described8. The primary microglia were plated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco 11960044) with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and supplemented with 20 ng/ml M-CSF (RD 416-ML-010/CF) at a density of 100,000 cells per well in a 24-well plate. The media was refreshed by changing half every three to four days. On day in vitro (DIV) 4, half of the media was replaced with 1 µg/ml polybrene. TET-O-CMYC T58A-HRAS G12V and rTTA lentiviral particles were added at DIV 4 at a concentration of 1 µg/ml. The following day, the complete media was replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS, supplemented with 20 ng/ml M-CSF and 2.5 µg/ml doxycycline to induce the overexpression of CMYC T58A and HRAS G12V. Small molecules SB431542 (PeproTech 3014193), GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021 (Cayman Chemical Company 13122), and valproic acid (Cayman Chemical Company 13033) were added to the media after being dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

FACS and flow cytometry

The media was aspirated, and the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Gibco 10-010-049). Microglial cells were then dissociated from the plate using cold PBS and pipetting. Cells were resuspended in 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma A9418) in PBS for staining. The Live/Dead Blue kit (Thermo Fisher L34961) was used to exclude dead cells, and the cells were stained with CD11B-PeCy7 (Life Technologies 25–0112-82), CD45-BV421 (BD Biosciences 30-F11), and CX3CR1-APC (Biolegend 341609) as previously described. CD11b+ sorted cells were then plated for continued culture.

Immunocytochemistry

For immunocytochemistry, cells were plated on poly-D-lysine coated glass coverslips and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X in PBS. They were then treated with a blocking buffer (5% Normal Donkey Serum in PBS) for 1.5 h and incubated with a staining buffer (5% NDS, 0.1% Triton-X, 0.2% BSA) overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted 1:1000. The following primary antibodies were used: TREM2 (Bio-Rad AF1729) and rabbit-IBA1 (WAKO 019–19741). After washing with PBS, secondary antibodies were applied for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclear staining was performed with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen 62249) diluted 1:20,000 in PBS. Coverslips were then washed and mounted with Flouromount (Invitrogen 00495802).

Karyotyping

2E11 cells were sent to WiCell Research Institute for chromosome analysis, where a total of 20 cells were counted, and 18 were karyotyped with a band resolution greater than 230 G-bands per haploid genome.

Live imaging: phagocytosis and scratch-wound assay

For the phagocytosis assay, cells were dissociated using 30% Accutase (Sigma A6964) and placed in 48-well plates. A complete media change was performed the next day, followed by the addition of growth factors or doxycycline. After 3 days of incubation with or without treatments, the media was changed, and pHrodo E. coli bioparticles (Sartorius 4615) at 10 µg/ml were added just before imaging. Phase and orange channel images were captured to assess microglial confluence and fluorescence of internalized bioparticles every 15 min for the first 3 h, then at 1-hour intervals.

For the scratch wound assay, cells were passaged and plated in 96-well plates. A complete media change was done the following day, and 20 ng/ml M-CSF or 2 µg/ml doxycycline were added. After 3 days of incubation with or without treatments, the media was changed. When the cells reached confluence, a scratch wound was created with a P20 pipette tip, and debris was washed away with a complete media change with or without 20 ng/ml M-CSF. Images were captured every 30 min using a 20x IncuCyte (Sartorius).

LPS stimulation and ELISA

Following passaging and plating cells into a 12-well plate, the media was completely changed to DMEM/10% FBS with or without 20 ng/ml M-CSF. Three days later, the microglia were stimulated with 1 µg/ml LPS. Media was collected at 3 and 24 h post-stimulation. ELISA was conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol, using kits to detect mouse IL-6 (Biolegend 431304), mouse IL-1β (Abcam ab197742), mouse TNF-α (Biolegend 430901), and mouse CCR2/MCP-1 (Biolegend 446207). Expression levels were normalized based on total cell lysate protein using BCA (ThermoFisher Scientific 23225).

RNA-sequencing and transcriptomic analysis

Total RNA was extracted from treated primary microglia or 2E11 cells using the miRNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen 217084), yielding 5 and 4 biological replicates, respectively. RNA concentration and purity were verified with a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies), and all samples had a RIN score above 8.0. RNA libraries were prepared using 200 ng of total RNA following the Illumina Stranded mRNA Ligation Sample Prep Kit protocol. Library concentration and size distribution were assessed using a Bioanalyzer DNA 1000 chip (Agilent Technologies) and Qubit fluorometry (Invitrogen). Libraries were sequenced to obtain 50 M fragment reads per sample, adhering to Illumina’s standard protocol on the NovaSeq™ 6000 SP flow cell. Sequencing was performed as 100 × 2 paired-end reads using the NovaSeq SP sequencing kit and NovaSeq Control Software (version 1.8.0). Base-calling was completed with Illumina’s RTA version 3.4.4. For transcriptome analysis comparing 2E11 CTRL versus primary microglia, and 2E11 DOX versus CTRL, the MAPR-seq pipeline (v3.1.4) was utilized for alignment against the mouse (mm10) reference genome using STAR aligner, with featureCounts generating gene counts. Normalized counts per million (CPM) > 1 and a false discovery rate < 0.01 were applied to filter out lowly expressed genes. EdgeR was used to identify differentially expressed genes across comparisons. Heatmaps were generated with the Pheatmap package (version 1.0.12) in R (version 4.3.2).

The 2E11 comparison samples included four treatments (CTRL, DOX, M-CSF, and TGFb), with three biological replicates for each, and two samples extracted from each replicate. RNA quality checks and RNA-seq were conducted by the University of Chicago Genomics Core, yielding 30 million paired-end reads via the Illumina NovaSeq 6000, using the oligo dT directional method for library preparation. Reads were mapped to the mouse reference transcriptome GRCm39, version M27, using STAR (version 2.6.1d). Quality checks for raw reads and STAR mapping results were performed with FastQC and MultiQC. Raw reads were mapped to the Mus musculus transcriptome using Salmon (version 1.4.0), with results summarized in a report. Following read mapping with Salmon, tximport was employed to import outputs into the R environment. Annotation data from Mus_musculus.GRCm39M27 was utilized to summarize data from transcript-level to gene-level. Filtering was performed to eliminate non-protein coding genes and genes with low expression. Initially, non-protein coding genes were removed, reducing the count from 55,416 to 21,885. Subsequently, genes with less than 1 CPM in three or more samples were excluded, further reducing the total to 10,983. Differential gene expression analysis was carried out using limma, and heatmaps for microglial genes were created using Multiple Experiment Viewer (MeV, version 4.9.0). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment was performed using gprofiler for the 10,983 genes across all pairwise comparisons and treatment-specific differentially expressed genes, along with TRANSFAC (TF) for non-GO sources. Data wrangling and graphic generation were conducted using the tidyverse suite of R packages. All utilized R packages are accessible from the Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN), Bioconductor.org, or GitHub. EnrichR (https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/) was used for Wikipathway analysis of differentially expressed genes categorized as upregulated (FC > 0) or downregulated (FC < 0)9,10.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Student’s t-test for comparisons of single means. For group analyses, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test or other specified methods, using GraphPad Prism (version 8.3.0).

Results

Generation of immortalized murine microglia line using lentiviral transfection with oncogenes HRAS and CMYC

Initially, CD11b+ microglial cells were isolated from neonatal CD1 E18.5 embryos using MACS for primary cell culture. Various conditions and gene overexpression were explored to promote the immortalization of mouse microglia (Table 1). The small molecules tested included the TGFb inhibitor SB431542 (SB), the GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021 (CHIR), and valproic acid (VPA), none of which significantly affected long-term cell expansion or renewal. Additionally, growth factors such as thrombopoietin (TPO) and stem cell factor (SCF) did not enhance the self-renewal of primary mouse microglia, suggesting that external factors alone are insufficient to induce continuous self-renewal. The most effective strategy for inducible immortalization involved the combined oncogenic induction of CMYC T58A and HRAS G12V using a lentiviral TET-O system with rTTA in mouse microglial cells. The mutant T58A form of CMYC was found to boost self-renewal capacity and proliferation, enhancing clonogenic potential without tumorigenicity in neural stem cells11. Doxycycline (DOX) induction resulted in significantly increased cell proliferation in TET-O-HRAS-CMYC treated cells compared to primary microglia after two weeks of treatment (Fig. 1a-c). Immunocytochemistry confirmed that the isolated murine CD11b + cells expressed the microglial marker IBA1 (Fig. 1b). Live imaging over eight days indicated that the transduced microglial cells doubled in density within four days of DOX treatment for oncogenic expression (Fig. 1c). These results demonstrate successful transduction of primary IBA1+ microglia and proliferation induction through DOX treatment.

Table 1.

Experimental conditions tested for immortalization of microglia of human and mouse.

| Factors | Molecules | Concentration | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| TERT/MYC |

SB, CHIR, VPA ↓FBS |

10% FBS vs. 2% FBS | Reduction of FBS without replacement not healthy |

| TERT |

SB, TPO+ SCF+ PVA |

10 µg/mL, 100 ng/mL, 10 ng/mL, 10 ng/mL - 100 μg/mL |

Not proliferative |

| MYC | Not proliferative | ||

| TERT/MYC |

SB, CHIR, VPA ↓FBS |

10%FBS vs. 2% FBS | Reduction of FBS without replacement not healthy |

| CMYC T58A / HRAS G12V | M-CSF | 25 ng/mL M-CSF in DMEM/10% FBS |

FACS of CD11b+ CD45+ mouse microglia-> expansion-> able to select single cell colony and proliferate -> able to freeze/thaw for passage -> ongoing |

Fig. 1.

Primary mouse microglia can be immortalized through HRAS and CMYC transcriptional factors. (a) Timeline depicting the transduction of primary CD1 E17.5 microglial cells at DIV4, followed by doxycycline induction of CMYC T58A and HRAS G12V at DIV5. (b) Immunocytochemistry results showing IBA1+ (Green) non-transduced control microglia, indicating a high-purity microglial culture. (c) Live imaging of cell confluence using IncuCyte for microglial cells transduced with TET-O-CMYC T58A-HRAS G12V with doxycycline (DOX), compared to non-transduced primary microglia at DIV16-23. (d) FACS gating strategy for isolating CD11B+ LY6C– cells for microglial single-cell colony expansion. (e) Relative expression levels of microglial genes C1qa and P2ry12, as well as human oncogenes CMYC and HRAS, normalized to Gadph. This was assessed using qRT-PCR on CD11b+LY6C− microglial cells, comparing control and transduced TET-O-CMYC T58A-HRAS G12V with DOX microglial cells. Statistical significance was evaluated using an unpaired t-test (N = 3 replicates), with bars representing mean ± SEM. (f) Normalized counts per million (norm CPM) of murine proliferation genes Myc, Hras, Mki67, Mcm2 and Pcna in primary MG and 2E11 clonal line without doxycycline (2E11 CTRL) and with doxycycline (2E11 DOX) from RNA-sequencing of total mRNA.

After DOX-induced overexpression of CMYC T58A and HRAS G12V, microglial cells were sorted for CD11b+LY6C− to increase the purity of the microglial population (Fig. 1d). The proportion of CD11b+LY6C− cells decreased to about 3.9% of the total live cells in the transduced microglial population with CMYC-T58A and HRAS-G12V, compared to 30.1% in the control non-transduced microglial cells. This suggests that DOX-induced oncogene overexpression reduced the relative abundance of CD11b+ microglial cells (Fig. 1d). The decrease in CD11b expression following DOX induction may be due to a transition to a more proliferative and immature microglial state or an expansion of non-microglial cells. Consequently, FACS was necessary to eliminate contaminating cells after the MACS CD11b+ microglial isolation and doxycycline induction. Additionally, qRT-PCR results confirmed significant upregulation of the oncogenes CMYC and HRAS following DOX treatment, while expression of the microglial genes C1qa and P2ry12 was markedly reduced, indicating a loss of microglial identity during the proliferation phase (Fig. 1e). Both oncogenes were effectively induced by doxycycline, achieving at least a 1000-fold increase. Single-cell colony expansion was performed to create homogeneous microglial populations and assess whether CMYC T58A-HRAS G12V overexpression facilitates single-cell expansion. From two 96-well plates, four single-cell colonies (clones 2E11, 2D4, 1F3, and 1H9) were obtained, with subsequent characterization focusing on clone 2E11 due to its robust self-renewal capacity. Karyotyping results at passage 14 (P14) indicated that 2E11 cells are male and exhibit abnormalities in chromosome 3 (Supplemental Fig. 1). While these findings may arise from technical artifacts, they could also indicate developing clonal abnormalities or low-level mosaicism, suggesting that a lentiviral approach involving oncogenes may necessitate further karyotyping in later passages to confirm the stability of the microglial line.

Withdrawal of DOX promotes a more homeostatic and mature microglial phenotype in 2E11 line

Transcriptomic analysis of primary microglia (primary MG), 2E11 CTRL, and 2E11 DOX revealed distinct clustering in microglial gene expression (Fig. 2a-c). Upon withdrawal of DOX, 2E11 CTRL displayed lower levels of homeostatic microglial genes, such as P2ry12, Fcrls, and Cx3cr1, compared to primary MG, yet higher than in 2E11 DOX (Fig. 2a-b). This suggests that while 2E11 CTRL is less “mature” and “homeostatic” than primary MG, it exhibits more differentiation than 2E11 DOX. Additionally, 2E11 CTRL exhibited increased expression of inflammatory genes linked to disease-associated microglia (DAM) and the neurodegenerative microglial phenotype (MGnD)12,13, including Lyz2, Clec7a, Apoe, and Il1b, compared to both primary MG and 2E11 DOX (Fig. 2a, c). This may indicate a transition to a more pro-inflammatory and mature state compared to 2E11 DOX.

Fig. 2.

Distinct gene expression profiles in primary MG, CTRL, and DOX-treated 2E11 microglial cells. (a) Heatmap illustrating microglial gene expression across primary MG (CD1), 2E11 CTRL, and 2E11 DOX. (RED indicates high z-scores, while BLUE indicates low z-scores for gene expression). (b) Key genes linked to the microglial neurodegenerative phenotype (MGnD) and disease-associated microglia (DAM) in microglia (normalized CPM = counts per million). (c) Key genes related to homeostatic (M0) and anti-inflammatory functions in microglia (normalized CPM = normalized counts per million). The y-axis is represented on a log10 scale.

To elucidate the molecular pathways differentially regulated by DOX-induced overexpression of CMYC and HRAS in mouse microglia, gene ontology pathway analysis was performed on differentially expressed genes comparing 2E11 CTRL to primary MG and 2E11 DOX to 2E11 CTRL (Fig. 3a-d and Supplemental Table 1). The transient induction of CMYC and HRAS by DOX in 2E11 CTRL resulted in the upregulation of genes associated with IL2 production (GO: 0032743) and type I interferon cellular responses (GO: 0060337, 0071357, 0032479, and 0032480), alongside the downregulation of genes linked to mitotic cell cycle phase transitions (GO: 0044772, 0000082, 0044843) and DNA replication (GO: 0006260) (Fig. 3a, c). Furthermore, DOX-induced overexpression of CMYC and HRAS in 2E11 cells led to the upregulation of genes related to signal recognition particle-dependent cotranslational protein targeting to membranes (GO:0006614, 0006613) and viral gene expression (GO:0019080), while downregulating genes associated with pattern recognition receptor signaling (GO:0002221) and toll-like receptor pathways (GO:0002224) (Fig. 3b, d).

Fig. 3.

Altered gene expression in 2E11 CTRL microglia related to immune pathways, with DOX treatment inducing protein translation-related gene expression. (a) Volcano plots comparing 2E11 CTRL to Primary MG. A total of 2,130 differential genes were identified, with 1,121 genes upregulated and 1,009 genes downregulated. (b) Volcano plots comparing 2E11 DOX to 2E11 CTRL. A total of 2,963 differential genes were found, including 1,629 induced and 1,334 repressed. (c) The top 10 most significant Gene Ontology (GO) analyses for biological processes (2018 version) based on differentially expressed genes for 2E11 CTRL vs. Primary MG. (Upregulated genes are listed at the top, while downregulated genes are at the bottom). (d) The top 10 most significant Gene Ontology (GO) analyses for biological processes using differentially expressed genes for 2E11 DOX vs. 2E11 CTRL. (Upregulated genes are at the top, downregulated genes at the bottom). For parts a-d, the sample sizes were 5 replicates for Primary MG, 4 replicates for 2E11 CTRL, and 4 replicates for 2E11 DOX. Differential expression analysis criteria: CPM > 1, FDR < 0.01, Log2-Fold Change ≥ |1|. The color fill gradient represents -log10(adjusted p-value), with red indicating the lowest values, grey indicating middle values, and navy blue indicating the highest p-values. The numbers on the bars represent the overlapping genes for each biological pathway.

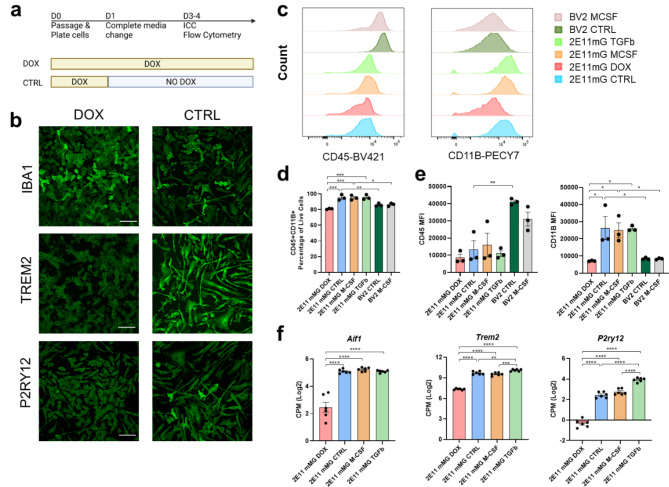

We hypothesized that DOX-induced oncogene expression allows for rapid expansion of 2E11 microglial cells, and withdrawing DOX facilitates their differentiation into a more homeostatic and mature state, enhancing physiological relevance for characterization (Fig. 4a). Our findings demonstrated that cell density was maintained, with morphological changes observed, such as increased ramification of microglia three days post-DOX withdrawal (Fig. 4b). The transduced 2E11 CTRL microglia exhibited more ramified IBA1+ cells and elevated expression of TREM2 and P2RY12 in vitro (Fig. 4b). Additionally, flow cytometry analysis revealed that DOX withdrawal significantly influenced 2E11 differentiation (Fig. 4c-e, Supplemental Table 2). We compared the effects of DOX, macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), and transforming growth factor-beta (TGFb) treatment. Standard microglial culture protocols typically require M-CSF for promoting cell survival and proliferation14,15. M-CSF is known to induce PU.1 expression, enhance antigen presentation proteins, and facilitate phagocytosis14. Meanwhile, TGFb is critical for establishing a homeostatic microglial signature in vitro4,16. Consequently, we examined whether M-CSF or TGFb modifies the microglial phenotype in the transduced 2E11 cell lines. Histograms of BV421-CD45 and PE-Cy7-CD11b indicated a shift in cell populations toward increased CD11b expression following doxycycline withdrawal (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, comparisons of all 2E11 treatments to the commonly used immortalized murine BV2 cell line revealed lower CD45 expression and higher CD11b expression across all 2E11 lines (Fig. 4c and Supplemental Fig. 2a-b). Flow cytometry of transduced cells four days post-passage indicated that approximately 90% of cells expressed CD45 and CD11b, typical microglial markers (Fig. 4d, left). However, DOX treatment reduced the mean fluorescent intensity of CD11b compared to 2E11CTRL, M-CSF, or TGFb-treated microglia (Fig. 4e). IBA1 expression is indicative of maturation and activation; our RNA-sequencing results showed increased Aif1 (IBA1), Trem2, and P2ry12 gene expression, suggesting a more mature and homeostatic state of microglia (Fig. 4f). Collectively, these findings indicate that transduced microglia can undergo rapid expansion in a controlled manner and differentiate into a more mature, ramified state upon DOX withdrawal. This suggests that the removal of DOX and the subsequent reduction of CMYC and HRAS oncogene expression facilitate microglial differentiation.

Fig. 4.

DOX withdrawal promotes microglial differentiation and increases expression of microglial genes TREM2, P2RY12, CD45, and CD11b. (a) Timeline of experiments for doxycycline induction (DOX) and control (CTRL) treatment groups. (b) Representative images of microglial cells at day 4: the left panel shows doxycycline-induced immortalization, while the right panel shows control cells. The top panel displays IBA1 expression, the middle panel highlights increased TREM2, and the bottom panel shows elevated P2RY12 expression following doxycycline withdrawal (scale bar = 50 μm). (c) Histogram comparing CD45 and CD11b expression in the immortalized BV-2 cell line (dark green) versus transduced microglia treated with doxycycline (DOX, red), no doxycycline (CTRL, blue), or with 20 ng/ml M-CSF (orange) or TGFb (bright green) over three days. (d) Percentage of CD45 + CD11b + microglial cells based on treatment. (e) Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for CD45 and CD11b. N = 3 replicates from 2 independent batches. (f) RNA sequencing results for microglial markers Aif1, Trem2, and P2ry12, presented in counts per million (CPM) on a log2 scale. N = 6 replicates from 3 independent batches. Statistical analyses were performed using One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Bars represent mean ± SEM.

TGFb treatment enhances homeostatic microglial gene expression in 2E11 line while MCSF treatment has minimal effect on microglial transcriptome

Our transcriptomic analysis of 2E11 cell lines indicates that the oncogenes CMYC T58A and HRAS G12V, along with growth factors M-CSF and TGFb, can influence microglial gene expression. Both DOX induction and TGFb treatment had the most significant effects on microglial gene expression, as shown by principal component analysis and heatmap data (Supplemental Fig. 3a-b). We observed that DOX-induced expression of CMYC and HRAS led to a more immature state, marked by reduced expression of homeostatic genes like Tmem119, P2ry12, and Fcrls (Fig. 5a). Gene ontology pathway analysis revealed that DOX treatment enriched genes related to RNA processing, ribosome biogenesis, and various cellular metabolic processing pathways (Supplemental Fig. 3c). E2f1 was identified as a critical regulator of DOX-induced microglial genes (Supplemental Fig. 3d), consistent with findings from Belhocine et al., who noted E2f transcription factors as essential regulatory checkpoints for efficient microglial cell cycling17.

Fig. 5.

DOX withdrawal and TGFb addition enhance homeostatic microglial gene expression. (a) Representative genes associated with homeostatic (M0) and anti-inflammatory genes in microglia (CPM = counts per million. (b) Representative genes associated with microglial neurodegenerative phenotype (MGnD) and disease-associated microglia (DAM) in microglia (2E11 CTRL, DOX, M-CSF, and TGFb).

Differential gene expression analyses between 2E11 DOX and CTRL highlighted significant downregulation of microglial genes, including Hexb and Spp1, while amino acid metabolism-related genes, such as Slc7a5, were significantly upregulated (Fig. 6a). TGFb treatment in 2E11 led to the induction of homeostatic genes, including Cx3cr1 and Fcrls (Fig. 6b). M-CSF showed minimal impact on the microglial transcriptome, suggesting it may not be essential for media supplements (Fig. 6c). We further conducted gene enrichment analysis using EnrichR with pairwise comparisons of specific treatments versus CTRL in 2E11 cell lines. Our findings indicated that the top pathways upregulated by DOX were linked to cytoplasmic ribosomal proteins (WP477) and DNA repair pathways (WP4946). Conversely, downregulated pathways included the TYROBP causal network in microglia (WP3945) (Fig. 6d). TGFb treatment robustly upregulated gene expression associated with insulin signaling (WP481) and TGFb receptor signaling in skeletal dysplasias (WP4816), while downregulated pathways included VEGFa-VEGFR2 signaling (WP3888) and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (WP4396) (Fig. 6e). M-CSF exhibited little to no significant effect compared to CTRL, primarily associated with upregulated interferon and complement pathways (Fig. 6f). These results demonstrate that DOX-induced overexpression of CMYC and HRAS significantly affects various immune-related pathways and cell cycle gene regulation. Additionally, the inclusion of TGFb resulted in greater gene expression changes than M-CSF treatment, indicating that M-CSF is not a critical supplement for the expression of microglial genes.

Fig. 6.

Differential gene expression analysis due to different treatment groups and Wikipathway of genes enrichment compared to CTRL. (a-c) Volcano plots illustrating significant differential expression, comparing (a) DOX vs. CTRL, (b) TGFb vs. CTRL, and (c) M-CSF vs. CTRL, based on -LOG10 adjusted p-value versus LogFC (log Fold Change). (d) Gene enrichment pathway analysis for DOX treatment compared to CTRL. (e) Gene enrichment pathway analysis for TGFb treatment compared to CTRL. (f) Gene enrichment pathway analysis for M-CSF treatment compared to CTRL. In panels d-f, upregulated genes are indicated (logFC > 0) or downregulated (logFC < 0), with the numbers on the bars representing the overlap of genes and the x-axis showing the negative log of adjusted p-values.

2E11 microglial cells are more ramified following MCSF and LPS stimulation

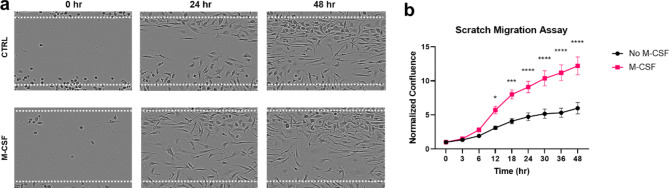

Microglial morphology can change in response to environmental shifts and immune stimuli, such as LPS exposure18–20. Our findings revealed that M-CSF treatment resulted in enhanced microglial process length and increased branch points, suggesting that M-CSF significantly promotes microglial differentiation and homeostatic function across all time points (Fig. 7a-b). Functional alterations are associated with these morphological changes20. Microglial cells can secrete pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in response to immune activation, such as LPS stimulation. In vivo studies indicate that LPS stimulation activates microglia and increases microglial volume, correlating with a neuroprotective phenotype in the brain21. Live imaging results demonstrated that LPS stimulation significantly increased the length of microglial processes 24 h post-stimulation in control microglia (Fig. 7c). These findings suggest that both M-CSF and LPS can independently alter the morphology of this transduced microglia in vitro, though LPS did not significantly affect microglial morphology in the presence of M-CSF. However, the ramification induced by M-CSF was less pronounced than that observed in vivo, where microglia exhibit more complex branching. Microglia can detect and migrate toward damaged areas to aid in cellular repair22,23. To determine whether this inducible 2E11 cell line can sense and migrate to injury sites, we conducted a scratch wound assay and observed the healing of the wound area (Fig. 8a-b). M-CSF treatment appeared to accelerate wound closure 12 h after creating a scratch wound with a pipette tip (Fig. 8b), indicating that M-CSF can activate microglia to enhance wound healing by increasing cell density.

Fig. 7.

M-CSF and LPS increase microglial ramification and branching. (a) Representative images of microglial cells after 3 days of treatment: withdrawal of doxycycline control (CTRL) and 20 ng/ml M-CSF treatment, with or without 1 µg/ml LPS stimulation at 48 h. Scale bar = 100 μm. (b) Quantification of microglial process length and branch points 24 h post-M-CSF treatment, analyzed using the Mann-Whitney T-test. (c) Quantification of microglial process length and branch points 24 h post-1 µg/ml LPS treatment, analyzed with two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test (n = 6 replicates from 2 independent batches). Bars represent mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Fig. 8.

M-CSF promotes migration of 2E11 microglial cells. (a) Representative images of control and M-CSF-treated microglial cells at 0, 24, and 48 h following the scratch wound. The dotted line indicates the path of the scratch created by the pipette tip. (b) Quantification of microglial cell migration across the scratch wound over 48 h at 3-hour intervals (n = 4–5, from 2 batches). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Bars represent mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

2E11 microglial cells demonstrate essential microglial characteristics

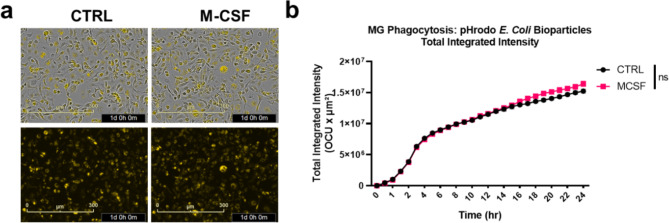

Another fundamental function of microglia is the phagocytosis of pathogens and cellular debris. After DOX withdrawal, the microglial cell line was treated with pHrodo E. coli bioparticles to assess phagocytic capacity. Results showed that transduced microglial cells could phagocytose E. coli bioparticles within hours, regardless of M-CSF treatment (Fig. 9a-b). M-CSF treatment did not significantly influence the total count or integrated intensity (Fig. 9b), although it did increase the area of pHrodo + microglial cells at 16 and 18–20 h, indicating transient phenotypic changes linked to phagocytosis due to M-CSF treatment, correlating with enhanced microglial processes (Fig. 9b). These findings demonstrate that microglia maintain their phagocytic capacity for E. coli bioparticles following immortalization and multiple passages, without the need for additional M-CSF treatment.

Fig. 9.

2E11 microglia exhibit phagocytosis of E. coli bioparticles. (a) Representative images showing merged views (top panels) and pHrodo (bottom panels) taken 24 h after the addition of E. coli bioparticles. (b) Quantification of phagocytosis of pHrodo bioparticles based on total integrated intensity (n = 6–7 replicates, from 2 independent batches). Analysis was conducted using repeated measures ANOVA and Sidak’s post hoc multiple comparison test.

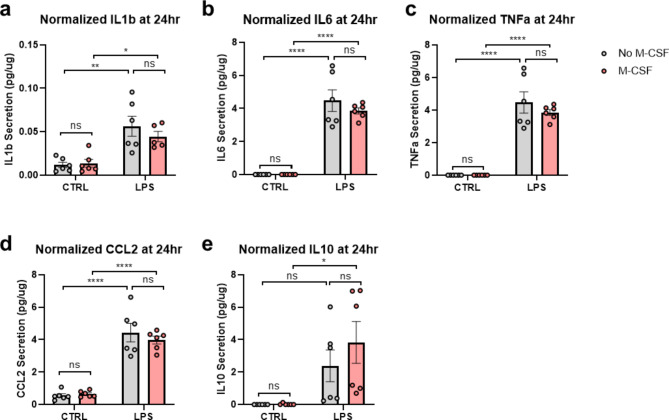

We also investigated whether 2E11 cells could secrete cytokines upon LPS stimulation after immortalization and DOX withdrawal. At 24 h post-LPS stimulation, levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and CCL2 secretion by microglia were significantly elevated (Fig. 10a-d). M-CSF treatment did not influence the secretion of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, or CCL2 (Fig. 10a-d). However, IL-10 levels increased only in the presence of LPS when treated with M-CSF (Fig. 10e). No significant batch effects were noted except for IL-10 secretion, indicating sustained microglial function regardless of passage number. In summary, LPS consistently stimulated the secretion of cytokines and chemokines by microglia, and the impact of M-CSF on IL-6 and IL-10 secretion was dependent on LPS stimulation.

Fig. 10.

LPS significantly increases cytokine and chemokine secretion from 2E11 microglial cells on days 3–4 following DOX withdrawal. (a) IL-1β, (b) IL-6, (c) TNF-α, (d) CCL2, and (e) IL-10 secretion levels, normalized to total cell lysate protein, measured 24 h after LPS stimulation by ELISA (n = 5–6 replicates, from 2 independent batches). Statistical analysis was performed using Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc multiple comparison. Bars represent mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Discussion

Numerous protocols have been developed for culturing microglia, often requiring complex formulations to mimic in vivo conditions; however, these methods have had limited success due to reliance on continuous expression of oncogenes for immortalization (Table 2)5,16,24,25. This study demonstrates that the inducible immortalization of primary microglial cells can achieve a more homeostatic state akin to human iPSC-derived microglial-like cells (iMGL). The use of doxycycline (DOX) to induce oncogenes CMYC T58A and HRAS G12V is essential for promoting rapid proliferation of CD45+CD11B+ microglial cells. Upon withdrawal of doxycycline, these cells adopt a more homeostatic phenotype, characterized by increased ramification and elevated TREM2 and CD11B expression. The transduced microglial cells can be passaged while retaining critical functions, such as cytokine secretion in response to LPS stimulation, wound healing, and pathogen phagocytosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of commonly used microglia cell lines examining microglial markers and function in vitro. Table modified from Stansley, Post, and Hensley (2012).

| Primary Microglia | BV-2 | 2E11 | N9 | HMO6 | iMGL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Mouse | Mouse | Mouse | Mouse | Human | Human |

| Immortalization | N/a | Transformed v-raf/v-myc | Inducible CMYC/HRAS | Transformed v-myc | Transformed v-myc | N/a |

| CD11b/MAC-1 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| P2RY12 | +→- (reduced with time in vitro) | - | + | - | N/A | + |

| LPS stimulation | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| lL-1β release | + | - | + | + | - | + |

| TNF-α release (Following LPS) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Phagocytosis | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Wound Healing | + | + | + | + | + | - |

We conducted comprehensive characterization of the 2E11 inducible microglial line using transcriptomics and functional assays. Following doxycycline withdrawal, the 2E11 CTRL cells began to differentiate and exhibited a more homeostatic profile. Gene ontology analysis revealed that the transient expression of oncogenes CMYC and HRAS resulted in the upregulation of genes linked to the IL-2 and type I interferon pathways, while downregulating genes associated with mitosis and cell cycle progression when compared to the transcriptome of primary microglia. Activation of the peripheral IL-2 signaling pathway led to an increase in regulatory T-cells and a greater number of plaque-associated microglia26, whereas type I interferon appeared to inhibit microglial niche colonization in mouse models27. These findings suggest that the rapid expansion of mouse microglia via CMYC and HRAS is regulated by genes in both the IL-2 and type I interferon pathways.

In comparison to primary microglia, the 2E11 CTRL microglia exhibit characteristics suggestive of increased maturity or senescence, as indicated by the downregulation of genes related to mitosis and DNA replication—likely due to replication stress and exposure to 10% fetal bovine serum. The decrease in expression of homeostatic microglial genes such as P2ry12, Fcrls, and Cx3cr1is expected, as in vitro conditions typically reduce microglial gene expression over time and passage when comparing 2E11 CTRL to primary microglia cultured for a few days1,3,4. However, 2E11 CTRL demonstrates higher expression of both homeostatic and disease-associated microglia (MGnD/DAM) genes compared to 2E11 DOX, suggesting that 2E11 CTRL may resemble microglia more closely than 2E11 DOX, which shows upregulation of genes involved in cotranslational protein targeting to membranes and rRNA processing. Our karyotyping results indicate detected abnormality in chromosome 3 after multiple passages in 2E11 cell line, suggesting the need to regularly karyotype to follow any additional abnormalities that might alter microglia function.

Further transcriptomic analysis indicated that DOX-induced CMYC and HRAS altered microglial gene expression, promoting RNA processing genes while reducing microglial-specific genes. Withdrawal of DOX led to a more homeostatic expression profile for various microglial genes, particularly those related to immune responses and the TYROBP causal network. The addition of M-CSF had minimal impact on the transcriptome, whereas TGFb treatment—often used to encourage a more homeostatic microglial phenotype—enhanced the expression of homeostatic microglial genes and reduced the expression of DAM/MGnD genes like Clec7a, Lgals3, and Bhlhe4012,13,16. While doxycycline withdrawal may facilitate differentiation, it may not be enough to elevate homeostatic markers to in vivo levels due to the absence of critical factors like IL-34, cholesterol, or astrocyte-derived growth factors that promote microglial differentiation4. Co-culturing with astrocytes or using astrocyte-conditioned media could further enhance homeostatic gene expression and microglial branching.

Our functional assays demonstrate that 2E11 CTRL and M-CSF-treated microglia can respond to LPS, secrete cytokines, perform phagocytosis, and migrate to wound sites. Future studies could explore neuron-glia interactions to assess how this cell line engages with brain circuitry and participates in synaptic pruning. This inducible system has been successfully applied to mouse microglial cell lines, and it would be beneficial for preclinical drug discovery to extend this method to human microglial cells, including primary microglia or iPSC-derived microglial-like cells1,28,29. Notably, significant genetic and potentially functional differences exist between human and mouse microglial cells, with human microglia exhibiting higher expression of complement genes such as C2 and C3. Human microglia are still not well characterized due to limited sample availability and the absence of standardized isolation and culturing techniques. Recent protocols for generating human iPSC-derived microglial-like cells (iMGLs) have advanced our understanding of human microglial biology25,30–33. These protocols produce iMGs with transcriptomic profiles more akin to in vitro human fetal microglia than to ex vivo microglia1,25,33. However, differentiating microglia from human iPSC-derived cells can be costly and subject to significant batch variability. Therefore, this inducible immortalization system may provide consistent results and enhance high-throughput screening capabilities.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

RNA sequencing of our primary microglia and 2E11 control and DOX conditioned cells was performed by Mayo Clinic’s Genome Analysis Core. We thank Jessie Hohenstein for processing raw data, conducting transcriptional analysis and heatmap generation. RNA sequencing for our 2E11 experiments was performed at the University of Chicago Genomic Core. We thank Jason Shapiro for processing raw data and transcriptomic analysis at the University of Chicago Center for Research Informatics Bioinformatics Core. The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Author contributions

T.I. designed the research; T.I. and S.I .provided the oversight and suggestion on data interpretation; H.Y., M.A.D.C., and Y.Y. performed the experiments. H.Y. and M.A.D.C. wrote the manuscript. T.I.,S.I., and Y.Y. assisted with the manuscript writing and editing. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was in part funded by Eisai (TI) and NIH grants R01 AG066429 (TI), R01 AG067763 (TI), R01 AG072719 (TI), R01 AG054199 (TI), RF1 AG082704 (SI, TI), and R01 AG079859 (SI).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gosselin, D. et al. An environment-dependent transcriptional network specifies human microglia identity. Science356, eaal3222 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Kettenmann, H., Hanisch, U. K., Noda, M. & Verkhratsky, A. Physiology of microglia. Physiol. Rev.91, 461–553 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett, M. L. et al. New tools for studying microglia in the mouse and human CNS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 113, E1738–E1746 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohlen, C. J. et al. Diverse requirements for microglial survival, specification, and function revealed by defined-medium cultures. Neuron94, 759–773e8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Timmerman, R., Burm, S. M. & Bajramovic, J. J. An overview of in vitro methods to Study Microglia. Front. Cell. Neurosci.12, 242 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Kendall, S. D., Linardic, C. M., Adam, S. J. & Counter, C. M. A network of genetic events sufficient to Convert Normal Human cells to a tumorigenic state. Cancer Res.65, 9824–9828 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maherali, N. et al. A high-efficiency system for the generation and study of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. Stem Cell.3, 340–345 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikezu, S. et al. Inhibition of colony stimulating factor 1 receptor corrects maternal inflammation-induced microglial and synaptic dysfunction and behavioral abnormalities. Mol. Psychiatry. 26, 1808-18 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, E. Y. et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinform.14, 128 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuleshov, M. V. et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res.44, W90–97 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Filippis, L. et al. Immortalization of human neural stem cells with the c-myc mutant T58A. PLoS One. 3, e3310 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keren-Shaul, H. et al. A Unique Microglia Type Associated with Restricting Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell169, 1276–1290e17 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krasemann, S. et al. The TREM2-APOE pathway drives the transcriptional phenotype of dysfunctional microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunity47, 566–581e9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith, A. M. et al. The transcription factor PU.1 is critical for viability and function of human brain microglia. Glia61, 929–942 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McQuade, A. et al. Development and validation of a simplified method to generate human microglia from pluripotent stem cells. Mol. Neurodegeneration. 13, 67 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butovsky, O. et al. Identification of a unique TGF-β–dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat. Neurosci.17, 131–143 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belhocine, S. et al. Context-dependent transcriptional regulation of microglial proliferation. Glia70, 572–589 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hart, A. D., Wyttenbach, A., Perry, V. H. & Teeling, J. L. Age related changes in microglial phenotype vary between CNS regions: grey versus white matter differences. Brain Behav. Immun.26, 754–765 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye, X. et al. Lipopolysaccharide induces neuroinflammation in microglia by activating the MTOR pathway and downregulating Vps34 to inhibit autophagosome formation. J. Neuroinflamm.17, 18 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He, Y., Taylor, N., Yao, X. & Bhattacharya, A. Mouse primary microglia respond differently to LPS and poly(I:C) in vitro. Sci. Rep.11, 10447 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen, Z. et al. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Microglial Activation and Neuroprotection against Experimental Brain Injury is Independent of Hematogenous TLR4. J. Neurosci.32, 11706–11715 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nimmerjahn, A., Kirchhoff, F. & Helmchen, F. Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science308, 1314–1318 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davalos, D. et al. ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nat. Neurosci.8, 752–758 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stansley, B., Post, J. & Hensley, K. A comparative review of cell culture systems for the study of microglial biology in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm.9, 115 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abud, E. M. et al. iPSC-derived human microglia-like cells to study neurological diseases. Neuron94, 278–293e9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dansokho, C. et al. Regulatory T cells delay disease progression in Alzheimer-like pathology. Brain139, 1237–1251 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lund, H. et al. Competitive repopulation of an empty microglial niche yields functionally distinct subsets of microglia-like cells. Nat. Commun.9, 4845 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geirsdottir, L. et al. Cross-species single-cell analysis reveals divergence of the Primate Microglia Program. Cell179, 1609–1622e16 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma, K., Bisht, K. & Eyo, U. B. A Comparative Biology of Microglia Across Species. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol.9, 652748 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Muffat, J. et al. Efficient derivation of microglia-like cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Med.22, 1358–1367 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Douvaras, P. et al. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells to Microglia. Stem Cell. Rep.8, 1516–1524 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haenseler, W. et al. A highly efficient human pluripotent stem cell Microglia Model displays a neuronal-co-culture-specific expression Profile and Inflammatory Response. Stem Cell. Rep.8, 1727–1742 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandya, H. et al. Differentiation of human and murine induced pluripotent stem cells to microglia-like cells. Nat. Neurosci.20, 753–759 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.