Abstract

Background

To address the health inequity caused by decentralized management, China has introduced a provincial pooling system for urban employees’ basic medical insurance. This paper proposes a research framework to evaluate similar policies in different contexts. This paper adopts a mixed-methods approach to more comprehensively and precisely capture the causal effects of the policy. Ultimately, this paper aims to assess the impact of the UPA policy on health inequity.

Methods

This study takes the provincial unified reform of basic medical insurance for urban employees in China as an example, uses the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) data and related policy documents, and adopts the DID-RIF hybrid method to test the impact of the equalization of the medical insurance system on health inequity, by using the interaction term in the DID (Difference-in-Differences) model as the independent variable in the RIF (Recentered Influence Function) to exclude the influence of other interfering variables. In addition, the DID method explores the effects of UPA on medical expenditures, which can guide the improvement of the policy.

Results

The empirical results show that the UPA policy increases the likelihood of patients developing chronic diseases within six months. Although factors such as age, gender, and marital status influence the probability of chronic disease, health inequity between income groups after the policy’s implementation primarily stems from the rise in outpatient and reimbursement expenses.

Conclusions

Although the gap in medical reimbursement expenses between participants of different socioeconomic statuses narrowed after the provincial medical insurance pooling reform, health inequity among the insured population increased. The equalized health insurance reform failed to address health inequities based on socioeconomic status. Additionally, the reverse reallocation of medical resources and outpatient arbitrage driven by moral hazard warrant close attention. This paper recommends that, in advancing the provincial pooling of UEBMI, greater focus should be placed on strengthening digital oversight and improving the hierarchical diagnosis and treatment system to promote social equity.

Keywords: Health insurance reform, Health equity, Chronic disease group, Socioeconomic status, Reimbursement expense, DID-RIF approach

Introduction

Health inequities are observable, systematic, avoidable, and unfair differences in health outcomes among groups in society [1–3]. These disparities persist despite advancements in medical technology and healthcare access globally [4, 5]. Addressing health inequities is crucial for achieving social justice and sustainable development [6]. Government policies play a critical role in shaping health outcomes and addressing health inequities [7]. Effective pooling arrangements in health insurance can enhance risk-sharing and resource allocation, contributing to universal health coverage and reducing health disparities [8–10].

China offers a pertinent case study in this regard. In recent years, the health level and physical quality of Chinese residents have continued to improve, yet significant regional disparities remain. Factors such as medical resource allocation, health expenses, and drug consumption are closely related to local economic conditions, leading to disparities in health outcomes among Chinese residents [11, 12].

In response to these challenges, the Chinese government has implemented the Unified Pooling Arrangement (UPA) for Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI), consolidating funds at a provincial rather than municipal level. This reform aims to enhance the redistribution of healthcare resources, improve insurance funds’ resilience and funding capacity, and ensure more equitable access to medical services. Despite its ambitious goals, the actual impact of the UPA on health inequity in China remains unclear. Existing studies often focus on descriptive analyses or simple before-and-after comparisons, which may not adequately capture the policy’s causal effects [13–15]. There is a pressing need for more rigorous empirical analyses to evaluate the effectiveness of such pooling arrangements in addressing health inequities [16, 17].

In recent years, research on health insurance has focused on its impact on individual health, including areas such as long-term care, commercial insurance, and social health insurance [18–20]. Studies have covered various age groups, emphasizing how age differences influence insurance demand and effectiveness. The field is shifting from single-effect evaluations to comprehensive analyses, which consider individual characteristics, as well as environmental and policy factors [20–22]. China’s socioeconomic context and medical policies offer valuable research opportunities. While most studies highlight the positive effects of health insurance on health, some have noted that specific types of insurance, such as unified school private insurance, have limited health benefits. It suggests that the effectiveness of insurance may depend on its level of personalization and how well it fits the target group [23].

The highlight of this paper is that it uses the interaction term in the DID (Difference-in-Differences) model as an independent variable in the RIF (Recentered Influence Function) to perform RIF regression on health inequity, estimating the effect of the UPA on health inequity. This study tries to employ a DID approach combined with the RIF method. The DID approach controls for unobserved confounders and isolates the causal effect of the UPA. At the same time, the RIF method provides a detailed examination of the policy’s impact on different points of health distribution [24–26]. By integrating these methodologies, we offer a comprehensive and nuanced analysis of the UPA’s effects on health inequity in China. Our methodology provides a framework for evaluating similar policies in diverse contexts. Finally, the insights gained from this study can inform policymakers in designing more effective interventions to reduce health inequities.

Method

Policy background

In 1998, China established the UEBMI system, managing at the county level to adapt to local conditions and encourage participation. However, significant disparities in health insurance treatment levels emerged across regions due to varying economic development, demographic structures, and implementation methods. This fragmented management exacerbated financial risks and inequities, undermining the mutual-aid function of health insurance.

China began raising the level of health insurance pooling to address these issues. Between 2000 and 2020, eight provinces and cities piloted the provincial pooling reform of UEBMI. Shanghai led the way in December 2000, followed by Beijing, Tianjin, Tibet, Chongqing, Hainan, Ningxia, and Fujian, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pilot regions and timelines for provincial pooling arrangement

| Province | Pilot time |

|---|---|

| Shanghai | 2000.12.01 |

| Beijing | 2001.04.01 |

| Tianjin | 2001.11.01 |

| Tibet | 2009.10.01 |

| Chongqing | 2011.10.24 |

| Hainan | 2012.01.01 |

| Ningxia | 2017.01.01 |

| Fujian | 2019.01.01 |

Data source: Official documents from the National Healthcare Security Administration of China and the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of China

The reform unified insurance levy, treatment standards, and fund management within pilot provinces. Employers and insured persons in these provinces now follow a unified contribution standard. Medical expenses are reimbursed uniformly for inpatient and outpatient services. The UEBMI department centrally collects and manages the provincial fund, ensuring participants receive the same level of medical insurance treatment across regions.

Data sources

The data used in this paper are primarily sourced from micro-survey databases, various statistical yearbooks, and official documents from relevant functional departments. For micro data, the study utilizes the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) database from 2016 to 2022 to estimate the impact of the unified UEBMI reform in pilot provinces on residents’ health inequity. Macro data are gathered from sources such as the China Urban Statistical Yearbook and the China Statistical Yearbook, providing key information on population, economy, and public health services in China. Information on the provincial pooling pilot is mainly drawn from official documents available on the websites of provincial governments, medical insurance bureaus, and human resources bureaus. These documents, which include details on implementation timelines and treatment standards for provincial pooling in each province, were manually collated for this study.

Model design

The empirical model in this paper is divided into two steps. The first step is to examine the effects of the unified pooling arrangement (UPA) policy on health status. In the second step, based on the significance of the policy variable results, the policy variable is incorporated into the RIF function to perform RIF regression on the health inequity index, estimating the effects of UPA policy on health inequity.

Considering the differences in implementation time of provincial pooling arrangements in different regions [27, 28], this article uses the staggered DID model to estimate the effects of UPA on health status. The model settings are as follows:

| 1 |

Among them, the explained variable is health status; the core independent variable refers to whether the province p where the individual i is located has implemented provincial pooling arrangement policy in the survey year t, indicating that the individual’s region has implemented policy during this year; otherwise, it is 0. is the set of all control variables; represents individual fixed effects; represents time fixed effects; represents regional fixed effects, and is a random disturbance term. This article defines provinces that implement provincial pooling as the treatment group and provinces that do not implement provincial pooling as the control group. This article selects four survey data from 2016 to 2022 in the CFPS database for analysis. Likewise, to evaluate the effects of UPA on medical expenditures, sequentially substitute the explained variable with five distinct medical expenses.

The RIF regression model refers to use the Recentralized Influence Function (RIF) to obtain the effect of changes in the independent variable on the distributional statistic of the dependent variable . Firpo et al. (2009) argue that the RIF regression model is able to estimate the effect of covariates on the explanatory variables when the distributional statistics are quantile [24]. The discussion in this section is based on the RIF function of health status (), inequity index (I). RIF (;I) is a non-monotonic transformation of health status ().

| 2 |

In Eq. (2), is the Influence Function (IF) proposed by Hampel (1974), which measures the effect of a small change in a specific value of health status on a target statistic (health inequity index) with the property that the expectation is zero [29]. This yields the expectation of equal to the health inequity index . Assuming that the expectation of is a linear function of the eigenvector X, the coefficient vector can be obtained by OLS regression as follows:

| 3 |

| 4 |

In Eq. (3), the coefficient vector represents the marginal impact of a small change in the mean of the corresponding characteristic on the inequity index when all else being equal. Firpo et al. (2009) used the impact function to obtain RIF estimates of various distributional statistics of health status (such as quantile, variance, and Gini coefficient) [24]. Cowell and Flachaire (2002) and Gradín (2018) further calculated RIF estimates for mean logarithmic deviation (MLD) and Theil index [25, 26]. Referring to the above literature, this paper measures the impact of the unified reform of UEBMI in the pilot provinces on the residents’ health inequity based on three types of inequity indices: quantile, Gini coefficient, and variance.

Variables design

Explained variable . The explained variable is health status, which includes chronic diseases and self-rated health [30, 31]. In the CFPS questionnaire, the corresponding question for chronic diseases is “Have you had any chronic diseases within six months?” and the value of “Yes” is 1 and “No” is 0. The corresponding question for health self-assessment is “How do you think your health is?” with 1–5 representing very healthy, very healthy, relatively healthy, average, and unhealthy, respectively. In addition, the explained variables in this paper are mainly the five types of medical expenses [32]. The total medical expenses are obtained by adding the inpatient and outpatient expenses. Inpatient expenses correspond to the question, “How much did you spend on hospitalization in the past 12 months, including reimbursed and expected reimbursements?”; outpatient expenses correspond to “How much did you spend in the past 12 months, including reimbursed and expected reimbursement, due to your injury or illness?”; out-of-pocket expenses correspond to “How much of the expense of your injury or illness in the past 12 months did you pay directly out of your own home?”; reimbursement equals total medical expenses minus out-of-pocket expenses. Considering the possible bias of the results due to outliers, this paper winsorizes the five types of medical expenses.

Explanatory variable . The explanatory variable is the provincial pooling arrangement policy [33]. Firstly, the year of policy release was obtained based on the date marked on the documents issued by various places regarding the implementation of provincial pooling. Secondly, match the release date of the document with the year of the questionnaire survey. If the release year is earlier than the year of the questionnaire survey, the variable takes “1,” meaning that the region has implemented provincial medical insurance pooling. Otherwise, it is “0”.

Control variables. Due to the impact of population, family, medical resources, and regional characteristics on health status, this article selects individual characteristic variables (age, gender, marriage, education, income) and regional characteristic variables (number of hospital beds, number of physicians, number of hospitals, population size, GDP) as the control variables [32, 34–36]. Among them, the age variable is obtained by subtracting the year of birth answered by the respondent from the time of the questionnaire. For the gender variable, women were assigned a value of 1, and men were assigned a value of 0. The marriage variable was obtained by asking the respondent, “Your current marital status,” and “Married” was assigned a value of 1, while “Unmarried,” “Cohabiting,” “Divorced,” and “Widowed” were assigned a value of 0. The education variable is based on the questionnaire “What is the highest level of education you are currently receiving (excluding adult education)?”. Assign “No education” to 1, indicating illiteracy; “Elementary school” to 2; “Junior high school” to 3; “High school/junior high school/technical school/vocational high school” to 4; “College” to 5; “Bachelor’s degree” to 6; “Master’s degree” to 7; “Doctor” is assigned to 8. Income refers to an individual’s monthly income, calculated by dividing the annual income by 12. The regional characteristics variables were obtained by matching the number of hospital beds, physicians, hospitals, population size, and per capita GDP across provinces.

Results

Descriptive statistics

This paper selected respondents who were enrolled in UEBMI as the research subjects. After excluding the sample with missing information, the final panel data of 4 periods with 3156 observations were obtained. The descriptive results of the relevant variables are shown in Table 2. Regarding the UPA policy variable, about 13.7% of the respondents were within the regions where the provincial pooling policy was implemented. Regarding health status, 17.7% of the respondents had suffered from chronic diseases within six months, and the average self-rated health score was 3.0. Concerning personal features, the age range of the sample was 21–88, with an average age of about 47; the proportion of male observation samples was higher than that of females, with 56.4% of them being male; the majority of respondents were married, accounting for 88.2%; the majority of respondents were at the college level, with a mean value of 4.4 for education level; the average per capita monthly income is 3774.9 CNY.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics

| Characteristics | Total N(%) | Mean(sd) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 3156 | |

| UPA | ||

| yes | 432(13.7) | |

| no | 2724(86.3) | |

| Chronic diseases | 3.0(1.0) | |

| yes | 560(17.7) | |

| no | 2596(82.3) | |

| Self-rated health score | ||

| very healthy | 236(7.5) | |

| healthy | 448(14.2) | |

| relatively healthy | 1795(56.9) | |

| average | 338(10.7) | |

| unhealthy | 339(10.9) | |

| Age | 47.4(13.7) | |

| < 45 | 1440(45.6) | |

| 45–60 | 1049(33.2) | |

| > = 60 | 667(21.1) | |

| Gender | ||

| women | 1375(43.6) | |

| men | 1781(56.4) | |

| Marriage | ||

| married | 2782(88.2) | |

| unmarried/cohabiting/divorced/widowed | 374(11.9) | |

| Education | 4.4(1.3) | |

| no education | 34(1.1) | |

| elementary school | 159(5.0) | |

| junior high school | 649(20.6) | |

| high school/junior high school/technical school/vocational high school | 756(24.0) | |

| college | 760(24.1) | |

| bachelor’ s degree | 730(23.1) | |

| master’ s degree | 59(1.9) | |

| doctor | 9(0.3) | |

| Income | 3774.9(4151.3) | |

| < 768 | 2377(75.3) | |

| > = 768 | 779(24.7) | |

| Number of hospital beds | 365,551.6(182,957.5) | |

| Number of physicians | 158,743.5(82,413.2) | |

| Number of hospitals | 43,117.8(24,776.5) | |

| Population size | 57,600,000(30,400,000) | |

| GDP | 69,515.3(33,795.8) | |

| Total medical expenses | 3040.8(7663.4) | |

| Inpatient expenses | 1487.5(5566.5) | |

| Outpatient expenses | 927.0(2207.9) | |

| Reimbursement expenses | 1363.3(4017.9) | |

| Out-of-pocket expenses | 1534.4(3765.5) | |

Data source: CFPS Database

The real GDP per capita of each province was approximately 69,515.3 CNY. Despite the huge population size, medical resources remain relatively scarce. The average number of hospital beds per province is 365,551, the average number of physicians per province is 158,743, and the average number of hospitals per province is 43,117. Regarding medical expenses, the average annual total medical expense was 3040.8 CNY. The average annual inpatient expense was 1487.5 CNY, which exceeded the average outpatient expense of 927.0 CNY, highlighting the high cost of inpatient care. Furthermore, the average annual reimbursement expense was 1363.3 CNY, close to the average annual out-of-pocket expense of 1534.4 CNY. It suggests that the reimbursement system has somewhat alleviated the personal financial burden. However, out-of-pocket medical expenses remain high, indicating that the medical security system needs further improvement to reduce the personal financial burden.

DID benchmark regression results

As shown in Table 3, for chronic diseases, the coefficient of UPA was significant at the 10% level, regardless of whether control variables were included. This indicated that UPA had a significant positive effect on the chronic disease variable. In contrast, for self-rated health, the coefficient of UPA was not significant, regardless of whether control variables were included, suggesting that UPA did not have a significant impact on self-rated health.

Table 3.

Effects of UPA policy on health status

| VARIABLES | Chronic diseases | Self-rated health | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| UPA | 0.063* | 0.060* | 0.134 | 0.124 |

| (0.036) | (0.035) | (0.097) | (0.094) | |

| Age | 0.008*** | 0.018*** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |||

| Gender | −0.022 | −0.135** | ||

| (0.018) | (0.053) | |||

| Education | 0.008 | 0.010 | ||

| (0.008) | (0.023) | |||

| Marriage | −0.044* | −0.010 | ||

| (0.025) | (0.064) | |||

| Ln Income | −0.002 | 0.003 | ||

| (0.002) | (0.004) | |||

| Ln GDP | −0.018 | 0.013 | −0.135 | −0.066 |

| (0.031) | (0.030) | (0.084) | (0.081) | |

| Time fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.323 | −0.306 | 4.471*** | 2.993*** |

| (0.334) | (0.331) | (0.891) | (0.902) | |

| Observations | 3156 | 3156 | 3156 | 3156 |

| R2 | 0.005 | 0.071 | 0.003 | 0.060 |

Standard errors in parentheses; *, **, *** represent significant at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively

Data source: CFPS Database

The regression results indicated that the UPA policy increased the probability of patients developing chronic diseases within six months. This outcome could be explained from two perspectives. First, in regions where the previous medical insurance benefits were relatively weak, the increase in reimbursement rates allowed low-income groups to have their medical needs met, leading to an increased likelihood of potential chronic disease patients seeking medical care. Second, with the elevation of the overall planning level, the shift of financial authority upwards and the delegation of administrative power downwards might cause municipal-level management departments to relax their supervision of medical insurance funds, potentially leading to excessive medical treatment by high-income groups. Therefore, it is essential to not only examine the impact of the UPA policy on various medical expenses but also to conduct further analysis using the RIF method.

Building on the above results, further investigation into the impact of the UPA policy on health inequity requires focusing on medical expenses. Considering the impact of medical resources and population demographics, control variables such as the number of hospital beds, physicians, hospitals, and population size are included to provide a broader perspective [32, 35, 36]. The empirical findings, presented in Table 4, show consistent results. Whether or not control variables are added, the regression coefficients for the UPA policy on outpatient expenses and reimbursement expenses are significant at the 1% and 10% levels, respectively. It indicates that the UPA policy has a significant positive effect on both outpatient and reimbursement expenses. The regression coefficients show that the implementation of the UPA policy led to an increase in outpatient expenses by approximately 868.96 CNY and in reimbursement expenses by about 774.91 CNY.

Table 4.

The effects of UPA policy on medical expenditures

| Variables | Total expenses | Inpatient expenses | Outpatient expenses | Reimbursement expenses | Out-of-pocket expenses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPA | 1255.61 | −139.90 | 868.96*** | 774.91* | 266.78 |

| ( 880.18) | (600.19) | (234.26) | (451.81) | ( 432.42) | |

| Control Variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 1632.83 | −1843.20 | 5061.01** | −1208.92 | 2034.30 |

| ( 9226.27) | (6440.79) | (2497.61) | (4769.89) | (4542.83) | |

| N | 3156 | 3156 | 3156 | 3156 | 3156 |

| R2 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

Standard errors in parentheses; *, **, *** represent significant at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively

Data source: CFPS Database

For inpatient expenses and out-of-pocket expenses, regardless of whether control variables were added, the regression coefficients of UPA were not significant. It indicated that provincial pooling arrangements had weak effects on inpatient and out-of-pocket expenses. The weak impact of out-of-pocket expenses stems from moral hazard. It includes issues such as the mismanagement of medical insurance funds by lower-level governments, excessive medical treatment in hospitals, and the waste of medical resources by insured individuals. To save money, insured individuals prefer to use reimbursed expenses rather than paying out of pocket.

From the DID baseline regression results, the increase in total medical expenses caused by UPA came from the increase in outpatient and reimbursement expenses rather than the inpatient and out-of-pocket expenses.

By sorting out the provincial pooling and implementation measures for urban employee medical insurance in various provinces, it was found that the employee medical insurance pooling fund is mainly used to pay for inpatient and outpatient medical expenses after deducting personal out-of-pocket payments. Since this article mainly focuses on chronic disease groups, the urban employee basic medical insurance fund, after deducting personal contributions, is mainly used to pay for outpatient medical expenses and inpatient expenses that comply with the special disease regulations for urban employee outpatients. Out-of-pocket expenses mainly consist of expenses incurred by the insured when going to pharmacies, private clinics, or hospitals that are not covered by the policy. Insured individuals bear these expenses, so provincial pooling does not impact out-of-pocket expenses.

All provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions implementing provincial pooling of UEBMI adopt a hospital-level differential reimbursement mechanism. For inpatient expenses, different levels of hospitals require different minimum payment standards and reimbursement ratios for insured persons’ inpatient reimbursement. Subdividing medical benefits according to different hospital levels can divert the insured’s demand for medical service resources, curb the excessive pursuit of high-quality medical service resources, and also reasonably avoid the moral hazard of local governments [37]. According to the “Opinions of the Ningxia Autonomous Region on the Regional-level Overall Management of Basic Medical Insurance for Urban Employees,” the minimum payment standards for medical insurance for employees in medical institutions at different levels are 300 CNY, 500 CNY, 800 CNY, and 1200 CNY respectively. The payment proportions within the scope of the medical insurance policy above the minimum standard are 95%, 90%, 85%, and 80%, respectively. In the “Shanghai Basic Medical Insurance Measures for Urban Employees,” the hospital-level differential reimbursement mechanism is subdivided based on employment status. However, the provincial pooling areas have not introduced specific measures to control outpatient expenses, so it may be unable to effectively restrain the reverse reallocation of medical resources and outpatient arbitrage caused by moral hazard. Outpatient and reimbursement expenses have increased after provincial pooling, which may be the main reason for the increase in medical expenses.

Robustness test

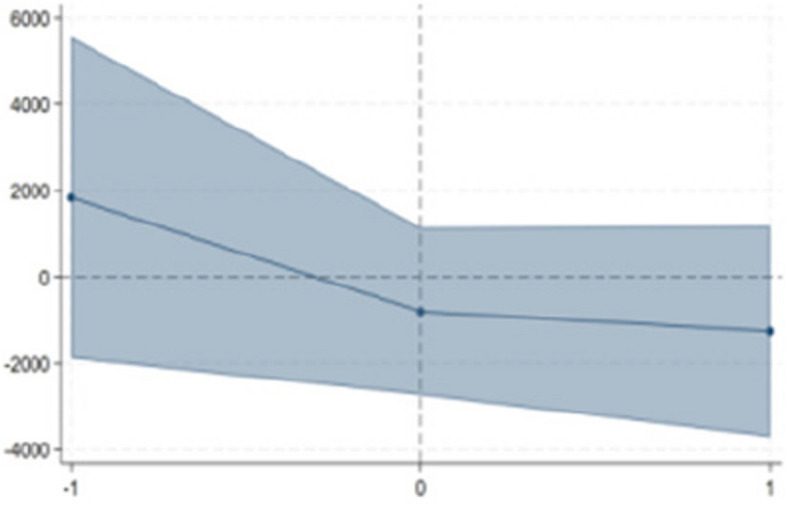

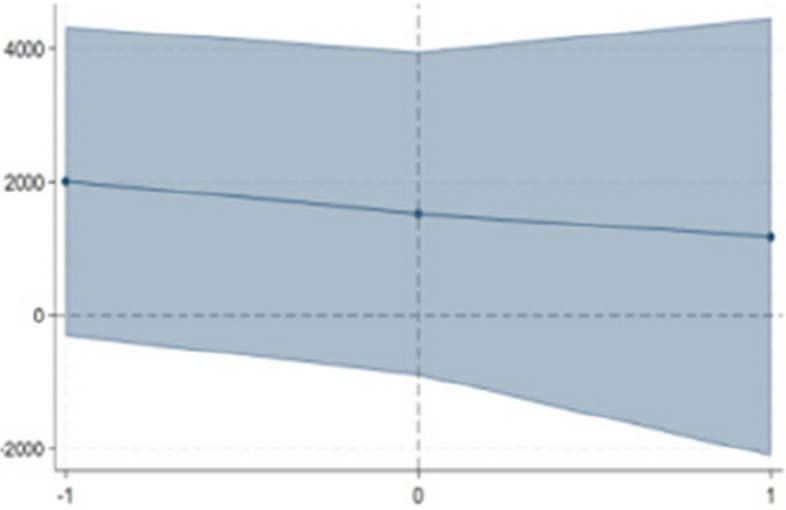

To verify the robustness of the DID benchmark regression results, this paper conducts two tests: the parallel trend test and the PSM-DID test. For the parallel trend test, this paper applies a dynamic effect analysis method based on event study methodology [38]. For the PSM-DID test, this paper combines propensity score matching with heterochronous difference-in-differences to further assess the robustness of the DID regression results [39]. The results confirm that the DID regression findings are robust. Detailed results are provided in the appendix (see Appendix Figs. 1-5, Table 11 and Table 12).

RIF regression results

Given the positive effects of the UPA policy on the chronic disease variable, this paper examined its impact on health inequity among chronic disease groups using RIF regression. Table 5 presents the RIF regression results for the effects of independent variables on health inequity indicators. The average RIF at the bottom of the table provides a reference point for interpreting the UPE, helping to understand how each variable in the model affects the distribution of the dependent variable. It serves as a common benchmark. Table 5 also reports standard errors based on bootstrap estimates from 500 replications. While standard errors in regression analyses with quantile statistics tend to be larger, bootstrap standard errors are the most appropriate for statistical inference [24]. All interpretations focus on current levels of inequity, ensuring comparability across different inequity indicators [40].

Table 5.

Determinants of chronic disease inequity

| Variables | Chronic disease | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| iqr (90 10) | Gini | Variance | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| UPA |

0.0776*** (0.0268) |

5.1590*** (1.7800) |

0.0516*** (0.0178) |

| Age |

0.0074*** (0.0006) |

0.4890*** (0.0390) |

0.0049*** (0.0004) |

| Gender |

−0.0209 (0.0128) |

−1.3920 (0.8500) |

−0.0139 (0.0085) |

| Educational level |

0.0069 (0.0065) |

0.4580 (0.4300) |

0.0046 (0.0043) |

| Marital status |

−0.0449** (0.0201) |

−2.9860** (1.3340) |

−0.0299** (0.0133) |

| Ln Income |

−0.0039** (0.0019) |

−0.2560** (0.1250) |

−0.0026** (0.0013) |

| Ln GDP |

0.0023 (0.0201) |

0.1540 (1.3360) |

0.0015 (0.0134) |

| Constant |

0.7150*** (0.2270) |

−7.9810 (15.0900) |

−0.0798 (0.1510) |

| Avg.RIF | 1.0542 | 14.5910 | 0.1460 |

| Observations | 3156 | 3156 | 3156 |

Standard errors in parentheses; **, *** represent significant at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively

Data source: CFPS Database

As shown in Table 5, column (1) reports the gap in the probability of chronic disease between the 90th and 10th quantiles. This gap reflects changes in health inequity between individuals with low-probability chronic diseases (10th quantile) and those with high-probability chronic diseases (90th quantile). Column (2) examines factors associated with the Gini coefficient of chronic disease probability. While the Gini coefficient is commonly used to measure income or wealth inequity, it is applied here to indicate inequity in chronic disease probability. Column (3) uses variance to measure inequity in chronic disease probability.

Although different inequity indicators measure the results, all variables consistently influence the probability of chronic disease. Researchers should interpret categorical variables, such as UPA, gender, and marital status, with caution. Interpreting their coefficients as varying from 0 to 1 may introduce bias into the predictions [40]. Upon analyzing Table 5, we conclude that the implementation of the UPA policy has increased the probability of chronic disease among urban employees. The likelihood of developing chronic diseases rises with age. For every one-year increase in age, the predicted Gini coefficient increases by 3.35%, the variance increases by 3.36%, and the health gap between the 90th and 10th quantiles rises by 0.70%. Low-income individuals are more likely to suffer from chronic diseases than high-income individuals. Likewise, married individuals face a higher risk of chronic diseases compared to people of other marital statuses. These results are consistent with the findings from the DID analysis.

Based on Eqs. (3), and (4), the UPE of categorical variables should be analyzed as deviations from the observed unconditional averages [40]. For instance, if the proportion of respondents in areas implementing the UPA policy increases by 10% (from 13.7% to 23.7%), the health ratio between the 90th and 10th quantiles will rise by 0.74% (0.0776/1.0542 × 0.1). Similarly, the predicted Gini coefficient will increase by 3.54% (5.1590/14.5910 × 0.1).

Discussion

RIF-OB decomposition

This study further investigates health inequity across income groups using RIF-OB decomposition. By controlling for observable characteristics such as age, gender, education level, and marital status, it examines the impact of the UPA policy on health disparities between different income groups.

Table 6 shows that higher IQR and variance in the low-income group suggest that health conditions are more dispersed and fluctuate more significantly. In contrast, the higher Gini coefficient in the high-income group reflects greater health inequity. Overall, the level of inequity is greater in the low-income group. Even if the low-income group shares the same distribution of control variables (age, gender, education level, and marital status) with the high-income group, their health inequity would still worsen.

Table 6.

OB decomposition results for chronic disease inequity indicator

| Chronic disease iqr (90 10) |

Chronic disease Gini |

Chronic disease Variance |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||

| Low-income group |

1.0960*** (0.0101) |

0.7910*** (0.0144) |

0.1650*** (0.0084) |

| High-income group with Low-income group |

1.0580*** (0.0062) |

0.8220*** (0.0092) |

0.1470*** (0.0059) |

| High-income group |

1.0500*** (0.0058) |

0.8330*** (0.0080) |

0.1390*** (0.0053) |

| Tdifference |

0.0459*** (0.0115) |

−0.0422*** (0.0162) |

0.0263*** (0.0098) |

| Total composition effect |

0.0080*** (0.0030) |

−0.0113*** (0.0044) |

0.0074*** (0.0028) |

| Total health structure |

0.0380*** (0.0112) |

−0.0309* (0.0162) | 0.0189* (0.0097) |

| Pure explained UPA |

−0.0007** (0.0003) |

0.0006** (0.0003) |

−0.0004** (0.0002) |

| Observations | 3156 | 3156 | 3156 |

| High-income group | 2377 | 2377 | 2377 |

| Low-income group | 779 | 779 | 779 |

Standard errors in parentheses; *, **, *** represent significant at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively

Data source: CFPS Database

After controlling for other variables, the UPA policy has reduced health inequity in the low-income group, as reflected in a more concentrated distribution. However, the increase in health inequity in the high-income group may be driven by moral hazard arising from potential over-treatment.

Heterogeneity test

Income and age are key factors influencing health status [41–43]. Higher-income people typically have better health due to greater access to resources. In contrast, older adults tend to have worse health than younger individuals. Variations in income and age also impact medical expenditure. The previous section analyzed the impact of the UPA policy on outpatient and reimbursement expenses from a holistic perspective. However, while the policy benefits people, differences in age and socioeconomic status among urban workers of varying age groups and income levels can lead to medical inequity and disparity in expenditure. To comprehensively analyze the impact of the UPA policy on medical inequity and expense disparities, this study conducts a DID regression based on age and income groups [44]. It enables a further exploration of the heterogeneous effects of the UPA policy on medical inequity and expenses.

The age classification divides adults under 45 as youth, those aged 45 to 59 as middle-aged adults, and individuals aged 60 and above as elderly [43, 45]. Income grouping classifies individuals with a monthly income below 768 CNY as the low-income group, and those with a monthly income of 768 CNY or more as the high-income group [46].

As shown in Table 7, for middle-aged adults, the coefficients of UPA are significant at the 5% and 10% levels for chronic diseases and self-rated health, regardless of whether control variables are included. It indicates that the UPA policy has a significant positive impact on both chronic diseases and self-rated health. The regression results indicate that the UPA policy raises the probability of middle-aged adults developing chronic diseases within 6 months. However, it also results in an improvement in their self-rated health.

Table 7.

DID regression analysis of chronic disease and self-rated health by age group

| Variables | Chronic diseases | Self-rated health | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth | Middle-aged adults | Elderly | Youth | Middle-aged adults | Elderly | |

| UPA |

0.038 (0.036) |

0.127** (0.061) |

0.079 (0.112) |

0.121 (0.117) |

0.340* (0.177) |

−0.023 (0.243) |

| Control Variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant |

−0.307 (0.361) |

0.325 (0.581) |

−0.793 (1.142) |

2.266** (1.155) |

4.100** (1.657) |

4.108 (2.522) |

| N | 1440 | 1049 | 667 | 1440 | 1049 | 667 |

| R2 | 0.015 | 0.021 | 0.036 | 0.024 | 0.034 | 0.034 |

Standard errors in parentheses; * and **, represent significant at the 10% and 5% levels, respectively

Data source: CFPS Database

Table 8 shows that for middle-aged adults and the elderly, the coefficient of UPA is significant at the 1% level for outpatient costs, regardless of whether control variables are included. It suggests that the UPA policy has a significant positive impact on outpatient costs. The regression results show that, following the implementation of the UPA policy, outpatient expenses increased by 1332.909 CNY for middle-aged adults and 1751.232 CNY for the elderly. Given the rising incidence of chronic diseases and improved self-rated health among middle-aged individuals, there may be a risk of medical resource waste and moral hazard in this group.

Table 8.

DID regression analysis of outpatient expenses and reimbursement expenses by age group

| Variables | Outpatient expenses | Reimbursement expenses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth | Middle-aged adults | Elderly | Youth | Middle-aged adults | Elderly | |

| UPA |

318.958 (247.291) |

1332.909*** (445.700) |

1751.232*** (575.864) |

627.878 (423.646) |

1042.848 (842.007) |

1422.818 (1427.696) |

| Control Variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant |

−1237.142 (2755.472) |

11,920.150** (4679.397) |

6209.507 (6225.778) |

−1378.681 (4750.675) |

1298.690 (8458.617) |

31.601 (15,167.930) |

| N | 1440 | 1049 | 667 | 1440 | 1049 | 667 |

| R2 | 0.053 | 0.087 | 0.175 | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.048 |

Standard errors in parentheses; **, *** represent significant at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively

Data source: CFPS Database

According to Table 9, for high-income groups, the UPA coefficient is significant at the 5% level for self-rated health, regardless of whether control variables are included. It indicates that the UPA policy positively influences self-rated health. The regression result shows that the UPA policy improves the self-rated health of high-income groups.

Table 9.

DID regression analysis of chronic disease and self-rated health by income group

| Variables | Chronic diseases | Self-rated health | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-income group | High-income group | Low-income group | High-income group | |

| UPA |

0.093 (0.059) |

0.057 (0.038) |

0.025 (0.152) |

0.205** (0.102) |

| Control Variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant |

0.002 (0.556) |

−0.340 (0.372) |

3.399** (1.442) |

3.354*** (0.997) |

| N | 779 | 2377 | 779 | 2377 |

| R2 | 0.101 | 0.063 | 0.053 | 0.066 |

Standard errors in parentheses; **, *** represent significant at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively

Data source: CFPS Database

Table 10 reveals that, for the high-income group, the coefficients of UPA are significant at the 1% and 5% levels for outpatient and reimbursement expenses, regardless of whether control variables are included. It indicates that the UPA policy has a significant positive impact on both outpatient costs and reimbursement expenses. The regression results indicate that, following the implementation of the UPA policy, outpatient expenses and reimbursement expenses for high-income groups increased by 1210.391 CNY and 1149.544 CNY, respectively. Considering the improvement in self-rated health among this group, there may be concerns about medical resource waste and moral hazard. High-income groups have more access to information about reimbursement policies. This access increases the likelihood of outpatient arbitrage and contributes to over-treatment.

Table 10.

DID regression analysis of outpatient expenses and reimbursement expenses by income group

| Variables | Outpatient expenses | Reimbursement expenses | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-income group | High-income group | Low-income group | High-income group | |

| UPA |

−118.959 (349.300) |

1210.391*** (281.512) |

354.862 (825.850) |

1149.544** (495.508) |

| Control Variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant |

589.944 (3761.219) |

5918.129* (3082.525) |

−10,240.050 (8908.098) |

3302.360 (5403.136) |

| N | 779 | 2377 | 779 | 2377 |

| R2 | 0.058 | 0.122 | 0.082 | 0.056 |

Standard errors in parentheses; *, **, *** represent significant at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively

Data source: CFPS Database

Conclusion

The Health Economics view is that the higher the socioeconomic status of the population, the better the health status. So, can implementing a parity health insurance system reduce the health gap between different income groups? The data for the study were obtained from the 2016–2022 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) data, various statistical yearbooks, and relevant policy documents. The paper examined the impact of the equalized health insurance policy on health inequity among different socioeconomic status groups by the Recentered Influence Function (RIF). It was found that although the gap in medical reimbursement expenses between participants of different socioeconomic statuses was narrowing after the implementation of the provincial pooling of UEBMI, the health inequity among the participants widened. The equalized reform of UEBMI did not alleviate the health inequity brought about by socioeconomic status.

Accordingly, this paper puts forward the following policy recommendations. Firstly, establishing a medical insurance data platform and strengthening digital supervision. It would eliminate information silos and enable the sharing and oversight of medical insurance data through a unified information system. Using digital tools, such as intelligent auditing and monitoring systems, the efficiency and security of medical funds can be improved while curbing moral hazards among high-income groups and the middle-aged and elderly. Secondly, promoting and enhancing the hierarchical diagnosis and treatment system. It will guide patients to seek appropriate medical care, reduce pressure on large hospitals, and improve primary healthcare capacity. Reforming medical insurance payment methods, such as disease-based payment, capitation, and other composite methods, can incentivize patients to prioritize primary care facilities, thus avoiding the waste of medical resources. Thirdly, focusing on vulnerable groups and increasing reimbursement for rare and chronic diseases. Reducing the financial burden on patients with such conditions. Finally, strengthening medical ethics and professional conduct education to prevent excessive treatment by doctors.

The contributions of this paper are: (1) combining macro and micro data with policy documents to analyze the impact of increasing the level of health insurance pooling on health inequity among different socioeconomic status and age groups; (2) exploring the policy transmission mechanism from the perspective of participants’ income and age; (3) examining how changes in health insurance benefits affect the health status of different socioeconomic and age groups, treating the UEBMI provincial pooling policy as an exogenous shock to effectively address the issue of endogeneity. The weaknesses of this paper are: (1) the measurement of health inequity needs to be further refined; (2) the data itself has limitations, particularly in terms of assessing the psychological impact and administrative capacity, which should be explored in future research.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- DID

Difference-in-Differences

- RIF

Recentered Influence Function

- UPA

Unified Pooling Arrangement

- CFPS

China Family Panel Studies

- UEBMI

Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance

- MLD

Mean Logarithmic Deviation

- CNY

Chinese Yuan

Appendix

Parallel trend test of the effects of UPA policy on medical expenditures

Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. Tables 11 and 12

Fig. 1.

Trend in total medical expenses. Data source: Compiled by the author

Fig. 2.

Trend in inpatient expenses. Data source: Compiled by the author

Fig. 3.

Trend in outpatient expenses. Data source: Compiled by the author

Fig. 4.

Trend in reimbursement expenses. Data source: Compiled by the author

Fig. 5.

Trend in out-of-pocket expenses. Data source: Compiled by the author

Table 11.

PSM—DID test of the effects of UPA policy on health status

| VARIABLES | Chronic diseases | Self-rated health score |

|---|---|---|

| UPA | 0.062* | 0.126 |

| (0.035) | (0.095) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| Constant |

−0.292 (0.332) |

3.014*** (0.903) |

| Observations | 3152 | 3152 |

| R2 | 0.070 | 0.060 |

Standard errors in parentheses, *** p < 0.01, * p < 0.1

Table 12.

PSM—DID test of the effects of UPA policy on medical expenditures

| VARIABLES | Total medical expenses | Inpatient expenses | Outpatient expenses | Reimbursement expenses | Out-of-pocket expenses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| UPA | 1302.728 | −123.687 | 865.050*** | 817.156* | 273.040 |

| (879.944) | (600.956) | (234.832) | (450.315) | (432.864) | |

| Control Variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 2207.248 | −1653.593 | 5016.551** | −699.951 | 2107.729 |

| (9225.414) | (6649.557) | (2503.370) | (4755.088) | (4548.364) | |

| Observations | 3152 | 3152 | 3152 | 3152 | 3152 |

| R2 | 0.054 | 0.031 | 0.104 | 0.057 | 0.046 |

Standard errors in parentheses, *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1

Authors’ contributions

Jing Wu is responsible for the concept, the framework of the article and the research design/methodology, the writing of the paper, data collection and processing; Yuqing Liu is responsible for data analysis and interpretation, proofreading and revising the paper, acted as the Corresponding Author for the article; Chuncheng Wang is responsible for logical sorting and paper revision, acted as the Corresponding Author for the article; Lianjie Liu contributed to data support and the optimization of the experimental design; Jiaqian Lu assisted with the optimization of the experimental design and manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Hebei Province Yanzhao Golden Platform Talent Program under the project “Research on Improving the System and Mechanisms for Urban–Rural Integration Development in County Areas” (Grant ID. HJZD202520) and the Hebei Provincial Social Science Fund for the project “Research on the Digital Collaborative Supervision Model of Medical Insurance Funds in the Context of Enhanced Coordination” (Grant ID. HB24GL006).

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) repository, http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study follows the relevant regulations and submit applications for ethical review to the “Biomedical Ethics Committee of Peking University” and the project ethical review lot number: IRB00001052-14010. The China Family Panel Studies were approved by the Ethical Committee of Peking University; informed consent was obtained from all individual participants; and the data were collected in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations or Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yuqing Liu, Email: liuyuqing202312@163.com.

Chuncheng Wang, Email: wangcc@ysu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Fuchs VR. The future of health economics. J Health Econ. 2000;19(2):141–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinda EM, Attermann J, Gerdtham UG, et al. Socio-economic inequalities in health and health service use among older adults in India: results from the WHO Study on global ageing and adult health survey. Public Health. 2016;141:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCartney G, Popham F, McMaster R, Cumbers A. Defining health and health inequalities. Public Health. 2019;172:22–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindahl M. Estimating the effect of income on health and mortality using lottery prizes as an exogenous source of variation in income. J Hum Resour. 2005;40(1):144–68. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D, et al. Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. JAMA. 1995;274(4):305–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27(1):167–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinda EM, Rajkumar AP, Attermann J, et al. Health, social, and economic variables associated with depression among older people in low and middle income countries: World Health Organization study on global ageing and adult health. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(12):1196–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, et al. The Oregon health insurance experiment: evidence from the first year. Q J Econ. 2012;127(3):1057–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathauer I, Saksena P, Kutzin J. Pooling arrangements in health financing systems: a proposed classification. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):198–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Currie J, Stabile M. Socioeconomic status and child health: why is the relationship stronger for older children? Am Econ Rev. 2003;93(5):1813–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ottersen OP, Dasgupta J, Blouin C, Buss P, Chongsuvivatwong V, Frenk J, et al. The political origins of health inequity: prospects for change. Lancet. 2014;383(9917):630–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng J, Song H, Wang Z. The elderly’s response to a patient cost-sharing policy in health insurance: Evidence from China. J Econ Behav Organ. 2020;169:189–207. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu J. Does Unified Pool Arrangement Trigger Healthcare Corruption? Evidence from China’s Public Health Insurance Reform. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2023;16:2259–61. 10.2147/RMHP.S435404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong B. The promotion of pooling level of basic medical insurance and participants’ health: impact effects and mediating mechanisms. Int J Equity Health. 2023;22(1):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu J, Yang H, Pan X. Forecasting health financing sustainability under the unified pool reform: evidence from China’s Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance. Health Econ Rev 14. 2024;77. 10.1186/s13561-024-00554-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Ma C, Huo S, Chen H. Does integrated medical insurance system alleviate the difficulty of using cross-region health Care for the Migrant Parents in China–evidence from the China migrants dynamic survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren Y, Zhou Z, Cao D, et al. Did the Integrated Urban and Rural Resident Basic Medical Insurance Improve Benefit Equity in China? Value Health. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Wang Q, Wang J, Gao F. Who is more important, parents or children? Economic and environmental factors and health insurance purchase. North Am J Econ Finance. 2021;58: 101479. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Guan J, Wang G. Impact of long-term care insurance on the health status of middle-aged and older adults. Health Econ. 2023;32(3):558–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao L, Guan J, Wang G. Does media-based health risk communication affect commercial health insurance demand? Evidence from China Appl Econ. 2022;54(18):2122–34. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guan J, Tena JD. Estimating the effect of physical exercise on juveniles’ health status and subjective well-being in China. Appl Econ. 2021;53(46):5385–96. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guan J, Tena JD. On the importance of internet access for children’s health and subjective well-being: the case of China. Appl Econ. 2024;1–13.

- 23.Guan J. Does school-based private health insurance improve students’ health status? Evidence from China Econ Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja. 2021;34(1):469–83. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Firpo S, Fortin N, Lemieux T. Unconditional Quantile Regressions. Econometrica. 2009;77(3):953–73. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cowell F, Flachaire E. Sensitivity of Inequality Measures to Extreme Values. LSE STICERD Research Paper. 2002;No. 60.

- 26.Gradín C. Explaining Cross-state Earnings Inequality Differentials in India: An RIF Decomposition Approach. WIDER Working Paper. 2018;No. 2018 /24.

- 27.Beck T, Levine R, Levkov A. Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. J Finance. 2010;65(5):1637–67. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu HP, Yue Y, Lin ZH. Effects of centralizing fund management on Chinese public pension and health insurance programs. Econ Res J. 2020;11:101–20. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hampel F. The influence curve and its role in robust estimation. J Am Stat Assoc. 1974;69:383–93. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu N, Luo J. The Status Quo and Influencing Factors of Chronic Diseases in Middle-aged and Elderly People in China: An Empirical Analysis Based on the CHARLS Database. Sci Res Aging. 2020;8(12):48–54. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang HL. Study on Measurement and Influencing Factors of Health Inequality among Chinese Residents. Popul Econ. 2023;2:124–44. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wen J, Du FY, Li LQ, Lu ZX. Influencing Factors and Empirical Research of Total Expenditure on Health in China. Chin Gen Pract. 2016;19(07):824–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan CJ, Yang J. The Impact of the Implementation of Hierarchical Medical Policy on Health Inequality Among the Chinese Elderly. Soc Sec Stud. 2022;1:49–60. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hong YB, Zeng DY, Shen J. Self-selection or Situational Stratification? A Quasi-Experimental Study of Health Inequalities. Sociol Stud. 2022;37(2):92–113+228.

- 35.Wang YD, Li TY. Can Provincial Pooling Improve the Accumulation Balance Rate of the Basic Medical Insurance Fund for Urban Workers: An empirical study based on provincial panel data from 2002 to 2021. Financ Dev Rev. 2024;6:68–82. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen YP. Medical Insurance Pooling, Utilization and Welfare: Intervening Mechanisms of the Rise in Medical Expenses with Pooling at the Provincial Level. Chin Soc Secur Rev. 2022;6(04):83–101. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu H, Yue Y, Xu J. Effects of Public Expenditures on Health Care Cost in China. Econ Res J. 2021;56(12):149–67. [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Chaisemartin C, d’Haultfoeuille X. Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects. American economic review. 2020;110(9):2964–96. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu ML, He M. Does Long - Term Care Insurance Crowd out Informal Care?Evidences from 2011–2018 CHARLS Data. Insurance Stud. 2021;12:21–38. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rios-Avila F. Recentered influence functions (RIFs) in Stata: RIF regression and RIF decomposition. Stata J. 2020;20(1):51–94. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;80–94. [PubMed]

- 42.Wang H. An empirical analysis of health inequality among residents in China. Stat Decis. 2022;38(13):77–82. 10.13546/j.cnki.tjyjc.2022.13.015. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu R, Li J. Trend and Decomposition of Health Inequality among Middle - Aged and Older Adults in China. Popul Dev. 2022;28(05):43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang XM, Yi FM, Jiang Y. “To Exacerbate”or “Mitigate” Income Inequality Among Migrant Workers : the impact of Digital Economy. J Huazhong Agric Univ (Soc Sci Ed). 2024;06:100–11. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang TX, Han JJ. Analysis of Health Inequality Among Urban and Rural Elderly in China from the Perspective of Integrated Medical and Elderly Care. Dongyue Tribune. 2018;39(7):169–77. [Google Scholar]

- 46.China National Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Communiqué of the People's Republic of China on National Economic and Social Development in 2023. [Internet] 2024 Feb 28. Available from: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202402/t20240228_1947915.html.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) repository, http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/.