Abstract

ASAP1 (ADP ribosylation factor [ARF]- GTPase-activating protein [GAP] containing SH3, ANK repeats, and PH domain) is a phospholipid-dependent ARF-GAP that binds to and is phosphorylated by pp60Src. Using affinity chromatography and yeast two-hybrid interaction screens, we identified ASAP1 as a major binding partner of protein tyrosine kinase focal adhesion kinase (FAK). Glutathione S-transferase pull-down and coimmunoprecipitation assays showed the binding of ASAP1 to FAK is mediated by an interaction between the C-terminal SH3 domain of ASAP1 with the second proline-rich motif in the C-terminal region of FAK. Transient overexpression of wild-type ASAP1 significantly retarded the spreading of REF52 cells plated on fibronectin. In contrast, overexpression of a truncated variant of ASAP1 that failed to bind FAK or a catalytically inactive variant of ASAP1 lacking GAP activity resulted in a less pronounced inhibition of cell spreading. Transient overexpression of wild-type ASAP1 prevented the efficient organization of paxillin and FAK in focal adhesions during cell spreading, while failing to significantly alter vinculin localization and organization. We conclude from these studies that modulation of ARF activity by ASAP1 is important for the regulation of focal adhesion assembly and/or organization by influencing the mechanisms responsible for the recruitment and organization of selected focal adhesion proteins such as paxillin and FAK.

INTRODUCTION

Attachment of cells to the extracellular matrix (ECM) is primarily mediated by the integrin family receptors (Hynes, 1992). Engagement of heterodimeric integrin receptors leads to the clustering of integrins and recruitment of numerous proteins to form multi-protein complexes on the cytoplasmic face of the plasma membrane termed focal adhesions (Burridge et al., 1988). Focal adhesions serve to anchor actin cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane and to provide a linkage between the extracellular environment and the cytoplasm (Burridge and Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, 1996). The recruitment of cytoskeletal proteins and the assembly of focal adhesions are functionally important for a number of cellular processes, including cell migration, survival, and proliferation (Lauffenburger and Horwitz, 1996). In the case of migrating cells (or cells spreading on ECM proteins), there is a requirement for the coordinated reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and the formation of new attachments with the substratum (Huttenlocher et al., 1995; Bretscher, 1996). This process is temporally and spatially controlled, consistent with integrins functioning as both cell adhesion receptors and as initiators of signaling cascades that convey signals from ECM to actin cytoskeleton (Bretscher, 1996).

Because integrins are catalytically inactive, their signaling ability is dependent upon the recruitment and activation of other signaling molecules, including focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (Schaller et al., 1992), pp60Src family kinases (Rohrschneider, 1980), protein kinase C (Woods and Couchman, 1992), and the Rho family of small GTPases (Schwartz and Shattil, 2000). The attachment of cells on ECM proteins results in an increase in FAK phosphorylation on tyrosine residues and the concomitant activation of FAK kinase activity (Lipfert et al., 1992; Schaller and Parsons, 1994). The phosphorylation of FAK on Tyr397 creates a docking site for the SH2 domain of pp60Src. Binding of pp60Src to Tyr397 activates pp60Src catalytic activity by displacing phosphorylated Tyr527, a Tyr residue in the C terminus of pp60Src whose phosphorylation and interaction with the SH2 domain negatively regulates pp60Src kinase activity (Schaller et al., 1994). The structure of FAK has also provided insight to how signals are transduced from integrin receptors to the actin cytoskeleton. The N-terminal domain of FAK binds directly in vitro to peptides corresponding to regions of the cytoplasmic domain of β integrin subunits (Schaller et al., 1995), and has recently been shown to bind to certain growth factor receptors (Sieg et al., 2000). The C-terminal domain of FAK contains binding sites for a variety of molecules, including the adapter protein Crk-associated substrate (Cas) (Harte et al., 1996; Polte and Hanks, 1997), the GTPase-activating protein GTPase regulator associated with FAK (Graf) (Hildebrand et al., 1996; Taylor et al., 1998, 1999), and the cytoskeletal proteins paxillin (Hildebrand et al., 1995) and talin (Chen et al., 1995). The associations of FAK with these molecules are believed to provide linkages between integrins, small GTP binding proteins, and serine/threonine kinases (Burridge and Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, 1996; Parsons et al., 2000).

Members of the ADP ribosylation factors (ARF) family of small GTPases were originally identified as cofactors required for the cholera toxin-catalyzed ADP ribosylation of Gs (Kahn and Gilman, 1986). One function of ARFs is to regulate endocytosis and vesicle trafficking by controlling the interaction of coat proteins with intracellular membranes (Donaldson et al., 1992; Stamnes and Rothman, 1993; Donaldson and Klausner, 1994). In addition, ARFs have recently been implicated in the regulation of cytoskeletal remodeling (D'Souza-Schorey et al., 1997; Radhakrishna and Donaldson, 1997; Norman et al., 1998; Song et al., 1998), although the exact mechanisms by which they act are poorly understood. ARF1 is reported to mediate the recruitment of paxillin to focal adhesions and to facilitate Rho-stimulated stress fiber formation in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts (Norman et al., 1998). ARF6, the least conserved member of the ARF family, cycles between plasma membrane and endocytic compartments, depending on its nucleotide status (Radhakrishna and Donaldson, 1997). Both constitutively active and dominant negative mutants of ARF6 have been shown to cause pronounced cell morphology changes when overexpressed in cells (D'Souza-Schorey et al., 1997; Song et al., 1998). A function of ARFs in integrin signaling has been suggested by virtue of the identification of proteins with ARF-GTPase-activating protein (GAP) homology that bind to focal adhesion components. ASAP1 (ARF-GAP containing SH3, ANK repeats, and PH domain) is a phospholipid-dependent ARF-GAP that binds to and is phosphorylated by pp60Src (Brown et al., 1998). ASAP1 is found in focal adhesions, and overexpression of ASAP1 is reported to block cell spreading and platelet-derived growth factor-induced cell ruffling (Randazzo et al., 2000). The ASAP1-related protein proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2) C terminus-associated protein (PAP)α/PAG3/KIAA0400 interacts with the FAK-related protein tyrosine kinase Pyk2 and paxillin (Andreev et al., 1999; Kondo et al., 2000). A second family of ARF-GAPs includes G-protein–coupled receptor kinase–interacting target 1 (GIT1)/CAT1/APP1 and GIT2/CAT2/paxillin kinase linker (PKL). PKL binds directly to the LD4 domain of paxillin and the guanine nucleotide exchange factor PAK-interactive exchange factor (PIX) and thus mediates the association of paxillin with a complex composed of PAK, Nck, and PIX (Turner et al., 1999). The association of several ARF-GAPs with focal adhesion proteins suggests that ARF GTPases and associated GAPs are important regulators of integrin signaling pathways during cell attachment and migration.

We have used several approaches to identify proteins that stably interact with the C-terminal region of FAK. We report here the characterization of ASAP1, an ARF GTPase-activating protein that interacts via its C-terminal SH3 domain with a proline-rich motif in the C-terminal region of FAK. Endogenous ASAP1 colocalizes with FAK and can be coimmunoprecipitated with FAK from extracts of both adherent and suspended cells. Transient overexpression of wild-type ASAP1 in rat embryo fibroblasts (REF52 cells) inhibited cell spreading and focal adhesion localization of paxillin and FAK. In contrast, overexpression of a catalytically inactive form of ASAP1 or a truncated form of ASAP1 bearing a deletion of the C-terminal SH3 domain failed to substantially inhibit cell spreading and paxillin/FAK localization to focal adhesions. We suggest that the association of ASAP1 with FAK as well as its GAP activity are functionally important in the organization and/or trafficking of paxillin/FAK-containing adhesion complexes in adherent cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA Constructs

Hexahistidine-tagged FAK-related nonkinase (FRNK; His-FRNK) has been described previously (Ma, et al., 2001). For yeast two-hybrid analysis, sequences encoding the C-terminal 201 amino acids of chicken FAK 853-1053 were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers FAT1 (5′-GCGGATCCCTCCAGGGCCCAGCT-3′) and FAT2 (5′-GCGAATTCTTAGTGGGGCCTGGACTG-3′). The resultant PCR product was cloned into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pGBT10, which was derived from pGBT9 (CLONTECH, Palo Alto, CA) by insertion of a multiple cloning site (5′-BamHI-AatII-EcoRI-SalI-PstI-3′).

The glutathione S-transferase (GST)-ASAP1 SH3 and CasL SH3 constructs were generated by subcloning the BamHI/EcoRI fragments from clone FV38, 23, 22 (Figure 1), respectively, into pGEX3X (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ). The construction of GST-FRNK, GST-P2FAT, and FRNK constructs containing proline to alanine mutations has been described elsewhere (Harte et al., 1996).

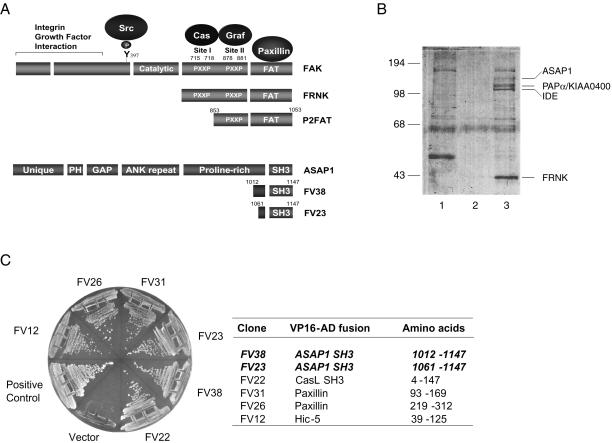

Figure 1.

FAK C-terminal interacting proteins. (A) FAK binding proteins and the documented sites of interaction are indicated. The amino-terminal domain, the central catalytic domain, two proline-rich motifs, and the focal adhesion targeting (FAT) domain of FAK are denoted for full-length FAK, the autonomously expressed C-terminal domain protein, FRNK, and the yeast two hybrid “bait” P2FAT. The individual domains of ASAP1 are indicated: unique region, PH domain, GAP domain, ankyrin repeats, proline-rich motif, and SH3 domain. ASAP1 SH3 clones identified in the two-hybrid screen are aligned with the full-length ASAP1 protein. (B) A FRNK affinity column was made by coupling His-tagged, bacterially expressed FRNK to Sepharose beads. Murine brain lysate was mixed with either Tris-Sepharose (lane 1) or recombinant His-tagged-FRNK-Sepharose (lane 3). As an additional control (lane 2), His-tagged-FRNK-Sepharose beads were eluted without the addition of brain lysate. Proteins recovered by incubation of the beads with elution buffer were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie Blue staining as described previously (Weed et al., 2000). Bands representing proteins selectively associated with FRNK (lane 3) were subjected to liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis as described in “Materials and Methods.” Positions of identified proteins are indicated. For ASAP1 and PAPα, 23 and 18 peptides were sequenced, providing 24 and 16% coverage of the respective proteins. (C) Yeast two-hybrid analysis of the interaction of P2FAT bait with FAK-interacting proteins. CG1945 cells were cotransformed with P2FAT bait plasmid and clones identified from two-hybrid screen. The resultant transformants were grown on Leu−Trp−His− plates supplemented with 5 mM 3-aminotriazole to test HIS3 reporter activity as described in “Materials and Methods.”

The mouse ASAP1 mammalian expression construct pFlagASAP1 was a generous gift from Paul A. Randazzo (National Institutes of Health). This construct was generated by subcloning an N-terminal Flag tag and the mouse ASAP1 cDNA into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) (Brown et al., 1998). To generate the ASAP1ΔSH3 mutant, ASAP1 cDNA was amplified by PCR using primers A5Full (5′-ATAAGCTTCGATGAGATCTTCAGCCTCCCG-3′) and A3SH3 (5′-CGGAATTCTACCCCGTATTGATTTTTCTC-3′). The resultant PCR product was digested with HindIII and EcoRI and was subcloned into pcDNA3Flag3AB (Devarajan et al., 1997). The R497K mutant was created from pFlagASAP1 with primers R497K1 (5′-GTTCCGGAATCCATAAGGAAATGGGGGTTC-3′) and R497K2 (5′-GAACCCCCATTTCCTTATGGATTCCGGAAC-3′) using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). All constructs were confirmed by direct DNA sequencing.

Identification of FRNK Binding Partners by Affinity Chromatography

Recombinant FRNK (8 mg) was coupled to cyanogen bromide-activated Sepharose 4B (Amersham Pharmacia) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Resins were suspended in 1 ml of column buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.8, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% NP40) and stored at 4°C. Coupling efficiency was ∼90%. Affinity purification, sequencing, and analysis of FRNK binding proteins from murine brain extracts were done according to previously described procedure (Weed et al., 2000).

Yeast Two-Hybrid Analysis

Transformation of yeast strain CG1945 was performed by the lithium acetate method (Gietz and Schiestl, 1991). β-Galactosidase activity was measured by the filter lift assay (Bartel and Fields, 1995). Yeast transformants carrying GAL4BD-P2FAT bait were transformed with a day 9.5 mouse embryonic cDNA library fused to VP16 activation domain (Joberty et al., 2000) and selected for growth on Leu−Trp−His− plates supplemented with 5 mM 3-aminotriazole. The positive clones were subsequently subjected to β-galactosidase assay. Plasmid DNA was isolated from yeast by phenol extraction and was recovered in the KC8 strain of Escherichia coli by selection on minimal medium plates without Leu.

In Vitro Binding Assays

GST fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli and were purified (Smith and Johnson, 1988) using glutathione-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia). Equal amounts of GST fusion proteins or GST alone (5 μg) were incubated with 500 μl of 1 mg/ml cell lysates in modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.05U/ml aprotinin, and 1 mM sodium vanadate) at 4°C for 2 h. The beads were washed twice with modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer and once with Tris-buffered saline. Associated proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis and western blotting with FAK specific monoclonal antibody (mAb) 2A7 (Wu et al., 1991) or anti-Flag mAb M5 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Antibodies and Coimmunoprecipitation Assay

ASAP1-specific rabbit polyclonal antiserum 642 was a generous gift from Paul A. Randazzo. Mouse anti-FAK mAb 2A7 was described previously (Wu et al., 1991). Anti-Flag mAb M5 and anti-vinculin mAb were purchased from Sigma. Anti-paxillin mAb, anti-FAK mAb, and anti-phosphotyrosine mAb RC20 were purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). Anti-FAK phospho-Tyr397 antibody was purchased from BioSource Inc. (Camarillo, CA). Anti-Cas was a generous gift from Amy Bouton (University of Virginia).

To immunoprecipitate endogenous FAK, 5 μg of anti-FAK mAb 2A7 was incubated with 500 μl of phosphate-buffered saline containing 50 μl of Protein A-Sepharose (Sigma) complexed to rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) at 4°C for 1 h. The beads were washed three times with cold phosphate-buffered saline and were incubated with 500 μg of clarified cell lysates in lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.8, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.05U/ml aprotinin, and 1 mM sodium vanadate) at 4°C for 2 h. Immune complexes were collected by centrifugation, washed twice with 1.0 ml of lysis buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and western blotted with anti-ASAP1 antibody 642. Antibody binding was detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG or horseradish peroxidase-conjugated protein A, followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia).

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Immunofluorescence Microscopy

REF52 and C3H10T1/2 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 10 μg/ml penicillin, and 0.25 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). For transient transfection experiments, cells were grown to 80% confluency in 100-mm dishes and were transfected with 10 μg of epitope-tagged ASAP1 construct using SuperFect (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Twenty-four hours after transfection, REF52 cells were trypsinized and replated on fibronectin in DMEM, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and immunostained as described previously (Weed et al., 1998). Endogenous ASAP1 was detected with antibody 642 (Randazzo et al., 2000), and endogenous FAK was detected with anti-FAK mAb 77 (BD Transduction Laboratories). In cell spreading assays, epitope-tagged ASAP1 was detected with anti-Flag mAb. To examine the localization and organization of actin and focal adhesion proteins paxillin, vinculin, and FAK, cells were stained with Texas-Red phalloidin (to detect polymerized actin), anti-ASAP1 642 and anti-paxillin mAb, or anti-vinculin mAb or anti-FAK mAb. Rabbit IgG was detected with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-rabbit, and mouse IgG was detected with Cy5-labeled goat anti-mouse (Jackson Laboratories, West Grove, PA). The transfected and nontransfected cells were distinguished by the level of ASAP1 staining.

RESULTS

Identification of FAK C-Terminal Binding Partners

To better understand the role of FAK in integrin signaling, we utilized both the yeast two-hybrid screen and affinity chromatography to identify proteins that interact with the C-terminal amino acids of FAK (Figure 1). Using an affinity matrix consisting of purified His-tagged FRNK (Figure 1A) coupled to Sepharose beads, several proteins (Figure 1B) were identified as strong FRNK binding partners. Mass spectrometry analysis of the individual bands revealed sequence matches with the ARF GTPase-activating protein, ASAP1, and a related family member, PAPα/KIAAA0400 (Figure 1B). Also identified was insulin degrading enzyme (IDE), a protein implicated in the degradation of intracellular insulin (Duckworth et al., 1998).

The C-terminal region of FAK contains a proline-rich PXXP motif (referred to as Site II) that interacts with the SH3 domain of Graf (Hildebrand et al., 1996; Taylor et al., 1998, 1999), a GAP for the Rho family of GTPases. In a parallel screen using a GAL4 fusion protein encompassing Site II and the FAT domain (P2FAT) as the bait (Figure 1A), we identified two independent clones encoding the SH3 domain of ASAP1 (Figure 1B) from a 9.5-d mouse embryo cDNA library (Joberty et al., 2000). In addition, cDNAs encoding proteins previously shown to bind to this region of FAK were also identified, including paxillin, CasL, and the paxillin homolog Hic-5. All clones expressing both GAL4BD-P2FAT and the identified mouse cDNAs were positive for cell growth on His− plates (Figure 1C) and β-galactosidase expression (unpublished results), indicating strong protein–protein interactions. Because two independent interaction screens identified ASAP1 as a FAK binding protein, we proceeded to characterize the function of this interaction more carefully. Further analysis of PAPα and insulin degrading enzyme was not carried out.

ASAP1 SH3 Domain Stably Associates with Site II of FAK In Vitro

To verify the interaction of the ASAP1 SH3 domain with FAK, GST fusion proteins were produced that contained GST fused to each of the two ASAP1 SH3 sequences identified from the two-hybrid screen. In addition, GST-CasL SH3 was also generated to serve as a positive control in the pull-down assay. Lysates from mouse 10T1/2 cells were incubated with 5 μg of each GST fusion protein, or GST alone, immobilized on glutathione beads, and the associated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting using anti-FAK mAb 2A7. As shown in Figure 2A, both GST fusion proteins containing the ASAP1 SH3 domains readily bound endogenous FAK from cell lysates (Figure 2, lanes 3 and 4). A GST fusion protein containing the CasL SH3 domain (Figure 2, lane 5) also bound efficiently to FAK, whereas GST alone failed to bind FAK (Figure 2, lane 2). These data clearly show that the SH3 domain of ASAP1 forms a stable complex with FAK in vitro.

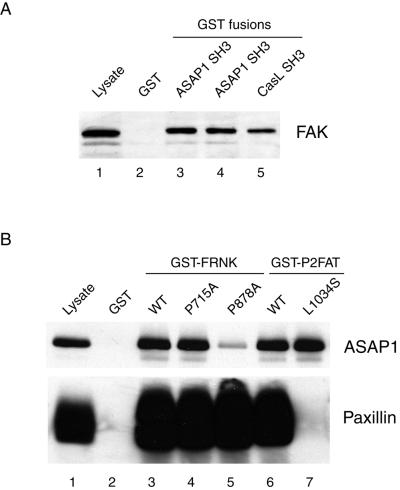

Figure 2.

The SH3 domain of ASAP1 interacts with the second proline-rich motif of FAK. (A) Constructs encoding GST fusion proteins were derived from sequences identified by yeast two-hybrid analysis, including two independent ASAP1 SH3-containing clones (lanes 3 and 4) and one CasL SH3 clone (lane 5). These GST fusions or GST alone were incubated with 10T1/2 mouse fibroblast cell lysate (500 μg) as described in “Materials and Methods,” and associated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using 2A7 anti-FAK mAb. CasL SH3 serves as positive control. Equal amounts of GST fusion proteins were used in the pull-down assay (unpublished results). (B) To map the targeting site of ASAP1, variants of GST-FRNK or GST-P2FAT were generated encoding proteins mutated in Site I (P715A, lane 4), Site II (P878A, lane 5), or in the paxillin binding domain (L1034S, lane 7). The GST fusion proteins were incubated with lysate (500 μg) from 10T1/2 cells transiently overexpressing Flag-tagged ASAP1, and the associated proteins were eluted and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-Flag mAb. The blot was subsequently stripped and reprobed with anti-paxillin to assess paxillin binding. In A and B, 25 μg of whole cell lysate was loaded as a control (lane 1).

The C terminus of FAK contains two proline-rich sequences, … P712PKPSRPGYPSP… and … P874PKKPPRPGAP… , which function as binding sites for SH3 domain-containing proteins. Because the P2FAT bait used in the two-hybrid screen encompassed the second but not the first proline-rich motif of FAK, we speculated that the major binding site of the ASAP1 SH3 was the second proline-rich motif. To test this, Pro→Ala point mutations (P715A and P878A) were generated to disrupt the first and the second PXXP motifs, respectively. These point mutations were constructed in the context of FRNK, which comprises the two proline-rich sequences and the FAT domain (Figure 1A). GST-FRNK fusion proteins were generated and assayed for their ability to associate with full-length ASAP1 transiently overexpressed in 10T1/2 cells. GST-FRNK P878A, which contains a mutation within the proline-rich region proximal to the FAT domain of FAK (Site II), displayed decreased association with ASAP1, whereas P715A mutation (Site I) had no impact on this interaction (Figure 2B, lanes 4 and 5). The association of ASAP1 with FRNK was not dependent upon paxillin binding because another mutation, L1034S, which blocked paxillin binding to FAK/FRNK (Tachibana et al., 1995), did not affect ASAP1 association with FRNK (Figure 2B, lane 7).

ASAP1 Associates with FAK In Vivo and Localizes to Focal Adhesions

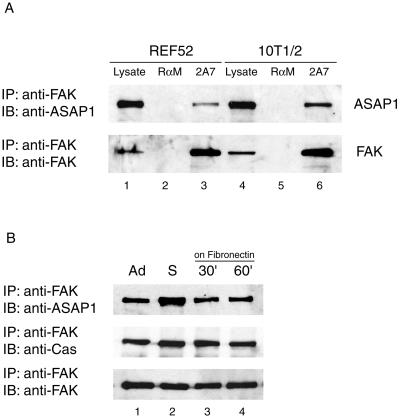

To demonstrate that ASAP1 and FAK form stable complexes within the cell, coimmunoprecipitation experiments were carried out. REF52 or 10T1/2 cells were grown to 90% confluency, and endogenous FAK was immunoprecipitated from the whole cell lysates using a FAK-specific mAb 2A7. As shown in Figure 3A, endogenous ASAP1 was readily detected in FAK immune complexes as revealed by blotting with an ASAP1-specific polyclonal antiserum 642 (Figure 3, lanes 3 and 6). A control antibody, rabbit anti-mouse IgG (RαM), failed to immunoprecipitate FAK–ASAP1 complex (Figure 3, lanes 2 and 5). To determine if the interaction between FAK and ASAP1 is adhesion dependent, the ability of ASAP1 to coprecipitate with FAK immune complexes was compared in the lysates of continuously adherent versus suspended or replated 10T1/2 fibroblasts. As shown in Figure 3B, ASAP1 was efficiently coprecipitated with FAK from suspended cells as well as from adherent cells. Another FAK associating protein, Cas, was also found in the FAK immune complexes in the lysate from suspended cells (Figure 3B), suggesting that a multi-protein complex containing FAK and its binding partners may exist during the process of focal adhesion turnover.

Figure 3.

Coimmunoprecipitation of ASAP1 and FAK. (A) REF52 and 10T1/2 cells were grown to 90% confluency. Endogenous FAK was immunoprecipitated from 500 μg of whole cell lysate using an anti-FAK mAb 2A7. The presence of endogenous ASAP1 in the immune complexes was assessed using ASAP1-specific antiserum 642. The blot was subsequently stripped and the efficiency of immunoprecipitation was assessed by blotting with anti-FAK mAb 2A7. Immunoprecipitation with rabbit anti-mouse IgG served as a control (lanes 2 and 5). Whole cell lysates (25 μg) were analyzed for FAK and ASAP1 expression (lanes 1 and 4). (B) Endogenous FAK was immunoprecipitated as in A from lysates of 10T1/2 cells cultured continuously on plastic (lane 1, Ad), detached, and held in suspension for 1 h (lane 2, S), detached, held in suspension for 1 h, and replated on fibronectin (2.5 μg/cm2) for 30 min (lane 3) or 60 min (lane 4). ASAP1 and Cas present in FAK immune complexes were detected with specific antibodies 642 and CasB, respectively. Approximately 1–5% of endogenous ASAP1 was found associated with FAK in immune complexes.

The association of ASAP1 with FAK both in vitro and in vivo points to ASAP1 being a focal adhesion protein. To confirm the subcellular localization of ASAP1, indirect immunofluorescence labeling of REF52 cells was carried out using ASAP1 antiserum 642. As shown in Figure 4, this antibody displayed strong staining of focal adhesions, (Figure 4, B and E), giving a pattern of staining identical to that observed with antibodies to paxillin or FAK, two well-characterized focal adhesion proteins (Figure 4, C and F).

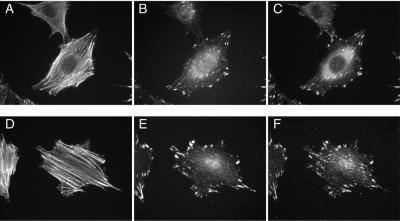

Figure 4.

ASAP1 is localized to focal adhesions. REF52 cells were plated on a fibronectin-coated coverslip (2.5 μg/cm2) for 4 h without serum. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and immunostained to detect actin (Texas Red-phalloidin, A and D), ASAP1 (anti-ASAP1 antibody 642, B and E), paxillin (anti-paxillin, C), or FAK (anti-FAK, F) as described in “Materials and Methods.”

Overexpression of ASAP1 Inhibits Cell Spreading and the Localization of Paxillin and FAK to Focal Adhesions

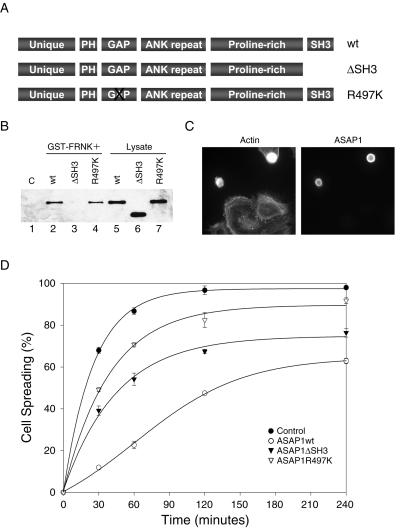

The association of ASAP1 with FAK, coupled with its localization to focal adhesions, indicates that ASAP1 may play a role in regulating events linked to integrin signaling pathways such as the cytoskeletal changes associated with cell adhesion and spreading. To test whether the interaction between FAK and ASAP1 and/or the GAP activity of ASAP1 was functionally important for integrin-mediated cell adhesion and spreading, two ASAP1 mutants were generated (Figure 5A). ASAP1ΔSH3 is a truncated variant that lacks the C-terminal SH3 domain and thus fails to stably bind FAK (Figure 5B, lane 3). ASAP1R497K bears an Arg→Lys mutation at a conserved position in the GAP domain and is defective for GAP activity (Randazzo et al., 2000); however, it still binds to FAK (Figure 5B, lane 4). Each of the variant forms of ASAP1, along with wild-type ASAP1, were tested for their ability to perturb cell spreading on fibronectin upon expression in REF52 cells. As shown in Figure 5, ASAP1wt-transfected cells exhibited a significant inhibition of cell spreading compared with nontransfected cells at 1 h (Figure 5, C and D). Four hours after initial plating, ∼40% ASAP1wt-expressing cells still displayed rounded phenotype (Figure 5D). Cells transfected with the GAP-deficient mutant, ASAP1R497K, showed a modest inhibition of cell spreading compared with the control cells (Figure 5D). Finally, cells expressing the ΔSH3 variant exhibited a clear inhibition of cell spreading, although the inhibitory effects were not as pronounced as that observed in cells expressing wild-type ASAP1. In an independent set of experiments, we determined that expression of GFP fusions to wild-type ASAP1 and GAP-deficient ASAP1 inhibited cell spreading to virtually the same extent as Flag-tagged wild-type ASAP1 and GAP-deficient ASAP1, respectively (unpublished results). We speculate that the inhibition of cell spreading observed in cells expressing ΔSH3 variant may reflect, in part, the negative regulation of ARF activity by this enzymatically active variant protein. The modest inhibition of spreading observed with the GAP-deficient variant likely reflects interactions mediated by other domains of ASAP1.

Figure 5.

Transient overexpression of ASAP1 inhibits spreading of REF52 cells. (A) Diagram of ASAP1 constructs. wt denotes wild-type ASAP1; ΔSH3 denotes a variant of ASAP1 lacking the SH3 domain, and R497K denotes a variant of ASAP1 bearing a mutation in the GAP domain that inhibits GAP activity. (B) REF52 cells were transiently transfected with ASAP1wt, ASAP1ΔSH3, and ASAP1R497K constructs. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cell lysates were prepared and GST pull-down assays were carried out using GST (lane 1) or GST-FRNK fusion proteins as described in Figure 2B. In lanes 5–7, 25 μg of cell lysates were analyzed to assess the expression level of three ASAP1 constructs. (C) A representative field of ASAP1wt-transfected cells plated on fibronectin (FN) for 1 h. Cells were trypsinized and plated on FN 24 h after transfection. Actin and ASAP1 were visualized using Texas Red phalloidin or anti-Flag epitope tag antibodies as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. (D) REF52 cells were transiently transfected with ASAP1wt, ASAP1ΔSH3, and ASAP1R497K, respectively. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were trypsinized and replated on FN for the indicated times and were immunostained for actin and ASAP1 as described in C. Cells were scored with respect to the extent of cell spreading as described previously (Randazzo et al., 2000; Richardson and Parsons, 1996). The data represent mean ± SD for two independent experiments.

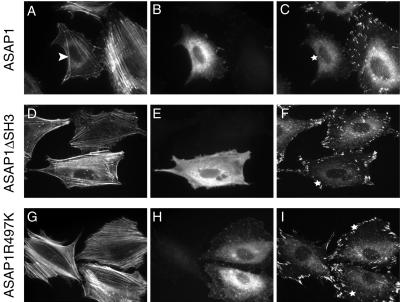

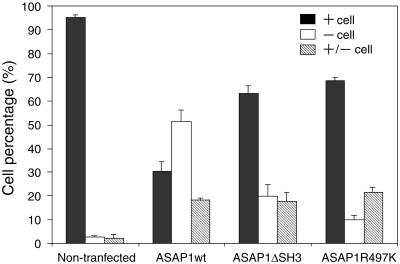

ARFs have been implicated in membrane trafficking (Donaldson et al., 1992; Stamnes and Rothman, 1993; Donaldson and Klausner, 1994) and cytoskeletal remodeling (D'Souza-Schorey et al., 1997; Radhakrishna and Donaldson, 1997; Norman et al., 1998; Song et al., 1998). To investigate the role of ASAP1 in the regulation of the subcellular localizations of paxillin and other focal adhesion components, REF52 cells were transiently transfected with ASAP1wt, ASAP1ΔSH3, or GAP-deficient ASAP1R497K, and paxillin localization was visualized as described in “Materials and Methods.” As shown in Figure 6, in ASAP1wt-transfected cells plated on fibronectin for 4 h, the distribution of paxillin was predominantly cytosolic, and paxillin localization to focal adhesions was significantly attenuated. In contrast, in cell expressing ASAP1ΔSH3 and ASAP1R497K, paxillin was almost exclusively localized to focal adhesions. To provide a quantitative measurement of these observations, paxillin localization was assessed in a population of transfected cells 4 h after initial plating. Cells exhibiting significant number (>20) of paxillin-positive focal adhesions were scored as “+ cells.” Cells that exhibited <10 paxillin-positive focal adhesions were scored as “−cells.” The designation “± cells” indicates those cells that had less than normal but more than 10 focal adhesions and/or cells that had focal adhesions with significantly smaller size. As shown in Figure 7, ∼50% of ASAP1wt-transfected cells displayed a “−cells” phenotype, whereas most (>60%) ASAP1ΔSH3 and ASAP1R497K-transfected cells showed a typical “+ cells” phenotype.

Figure 6.

Transient overexpression of ASAP1 alters the focal adhesion localization of paxillin. REF52 cells were transiently transfected with ASAP1wt, ASAP1ΔSH3, and ASAP1R497K. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were trypsinized and replated on FN-coated coverslip (2.5 μg/cm2) for 4 h in the absence of serum. Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and costained for actin (A, D, and G), ASAP1 (B, E, and H), or paxillin (C, F, and I). (A) The white arrow denotes the observed decrease in the overall number of actin stress fibers present in ASAP1 expressing cells. (C, F, and I) The “white stars” denote the transfected cells present in B, E, and H.

Figure 7.

Quantitation of paxillin-positive focal adhesions in cells expressing wt and variant forms of ASAP1. Cells were scored for the presence of paxillin containing focal adhesions as described in “Materials and Methods” and “Results.” For each variant construct, three independent experiments were performed and 100 cells were scored for each experiment. The data represent mean ± SD of the three independent experiments.

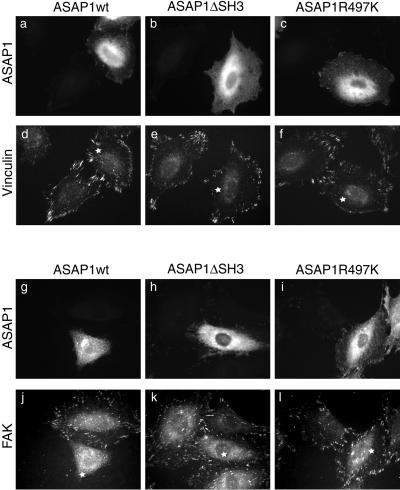

Although “−cells” exhibited reduced focal adhesion staining by anti-paxillin mAb, most cells still displayed some filamentous actin structures (Figure 5A, arrowhead). We suspected that other focal adhesion proteins such as vinculin could potentially drive formation of focal adhesion-like structures in the absence of paxillin in ASAP1-transfected cells. Therefore, vinculin localization was examined in cells transiently overexpressing ASAP1 constructs. As shown in Figure 8, unlike paxillin, vinculin localization was not affected by overexpression of wild-type ASAP1 (Figure 8, d–f). Quantitation of vinculin-positive focal adhesions in transfected cells showed that >50% of ASAP1wt-transfected cells exhibited a “+ cells” phenotype (unpublished results). The effects of ASAP1 variants on FAK localization were also examined. Similar to paxillin, FAK localization was perturbed by the expression of wild-type ASAP1, but not the ASAP1ΔSH3 or the GAP-deficient mutant (Figure 8, j–l). These results, coupled with the data from above, clearly indicate that overexpression of wild-type ASAP1 inhibits cell spreading and reduces the stable association of paxillin and FAK, but not vinculin, with focal adhesion structures. These observations are consistent with paxillin/FAK and vinculin being recruited to focal adhesions by different pathways.

Figure 8.

Transient overexpression of ASAP1 alters FAK but not vinculin localization. REF52 cells were transiently transfected with ASAP1wt, ASAP1ΔSH3, and ASAP1R497K. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated as in Figure 6 and were stained for ASAP1 (a–c and g–i), vinculin (d–f), and FAK (j–l). The “white stars” denote the ASAP1-expressing cells.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we show that ASAP1, an ARF GTPase-activating protein localized to focal adhesions, stably associates with FAK. The interaction of ASAP1 and FAK was initially identified using both yeast two-hybrid screen and protein affinity purification analysis. The C-terminal SH3 domain of ASAP1 selectively interacts with the second proline-rich motif in the C-terminal region of FAK. This interaction was verified by the pull-down of FAK with purified GST-ASAP1-SH3 domains, the pull-down of ASAP1 with purified GST-C-terminal FAK fusion proteins, and by coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous FAK and ASAP1 proteins. ASAP1 and FAK colocalize in focal adhesions of REF52 fibroblasts. Transient overexpression of wild-type ASAP1 significantly retarded the spreading of REF52 cells when plated on fibronectin. In contrast, overexpression of a truncated variant of ASAP1 that failed to bind FAK or a catalytically inactive variant lacking GAP activity resulted in less pronounced inhibition of cell spreading. Finally, transient overexpression of wild-type ASAP1 prevented efficient organization of paxillin and FAK in focal adhesions during cell spreading while failing to significantly alter vinculin localization and organization. These studies point out that regulation of ARF activity by ASAP1 is an important factor for the assembly and/or organization of focal adhesions by influencing mechanisms responsible for the recruitment and organization of selected focal adhesion proteins such as paxillin and FAK.

ASAP1 was originally identified as a tyrosine-phosphorylated substrate of pp60Src and was demonstrated to bind directly to the SH3 domain of pp60Src (Brown et al., 1998). However, the multidomain nature of ASAP1 indicates that it may also bind other signaling molecules, thus possibly coordinating ARF activity with multiple signaling pathways. The identification of an interaction between ASAP1 and FAK links ASAP1 activity to the integrin signaling pathway and is consistent with the observation that other closely related ARF-GAPs, GIT1 and PAPα, bind to FAK and FAK-related protein Pyk2, respectively (Andreev et al., 1999; Zhao et al., 2000). In the case of PAPα, the interaction with Pyk2 is likely mediated by the C-terminal SH3 domain analogous to the interactions described above (Andreev et al., 1999).

Previous experiments have shown that the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain and ANK repeats of ASAP1 are essential for its phospholipid-dependent ARF-GAP activity. An ASAP1 variant comprised of only the PH domain, the GAP domain and the ANK repeats exhibits GAP activity in vitro (Brown et al., 1998). However, in contrast to the putative role for the PH domains of ARF-GEFs (guanine nucleotide exchange factors) in intracellular targeting, the PH domain of ASAP1 appears dispensable for targeting ASAP1 to membrane ruffles induced by growth factors (Kam et al., 2000). The association of ASAP1 with FAK through its C-terminal SH3 domain may provide a potential mechanism by which ASAP1 is both recruited to adhesion sites and is activated via interactions with phospholipids.

As demonstrated herein and shown previously, ASAP1 is found in focal adhesions, and overexpression of ASAP1 blocks cell spreading and platelet-derived growth factor-induced cell ruffling (Randazzo et al., 2000). The ASAP1-related protein PAPα/KIAA0400 interacts with both FAK-related protein tyrosine kinase Pyk2 as well as paxillin (Andreev et al., 1999; Kondo et al., 2000). However, PAPα/KIAA0400 does not appear to accumulate in focal adhesions, which distinguishes this protein from ASAP1 (Kondo et al., 2000). At this time, it is not clear whether PAPα/KIAA0400 function is redundant with that of ASAP1. A second family of ARF-GAPs consists of GIT1/CAT1/APP1 and GIT2/CAT2/PKL. GIT1, which shows considerable sequence homology to PKL, binds to paxillin and PIX and is also reported to bind directly to FAK (Zhao et al., 2000). Interestingly, overexpression of GIT1 in fibroblasts causes the loss of paxillin from focal adhesions; however, these cells exhibit enhanced cell motility (Zhao et al., 2000). The association of multiple ARF-GAPs with focal adhesion proteins indicates that ARF GTPases and associated GAPs are likely to be important regulators of protrusive events and are likely to influence integrin signaling pathways during cells attachment and migration.

The demonstration that FAK and ASAP1 coimmunoprecipitate from extracts from suspended cells indicates that these two proteins may form an adhesion-independent stable complex. We have previously noted that FAK and paxillin are found stably associated in extracts of avain embryo cells placed in suspension (Hildebrand et al., 1995). These observations lead us to speculate that ARFs may participate in the organization of higher order complexes containing FAK, paxillin, Cas, and perhaps other adhesion proteins (e.g., PIX/Pac). These multi-protein complexes may exist at intracellular structures other than focal adhesions during focal adhesion turnover.

ASAP1 was shown to be tyrosine phosphorylated in cells expressing an activated form of Src (SrcF527) (Brown et al., 1998). However, we have been unable to detect ASAP1 tyrosine phosphorylation of endogenous ASAP1 from lysates of continuously adherent 10T1/2 cells, cells kept in suspension, or cells replated on fibronectin (Y. Liu and J.T. Parsons, unpublished observations). Under these conditions, tyrosine phosphorylation of endogenous FAK is readily detected upon cell spreading as revealed by a FAK phospho-Tyr397-specific antibody (unpublished results). In addition, we failed to observe ASAP1 tyrosine phosphorylation when cells were treated with 50 μM pervanadate for brief periods of time (unpublished results). These observations make less clear the role of tyrosine phosphorylation in ASAP1 regulation.

The observation that overexpression of ASAP1 retards REF52 cell spreading is consistent with the earlier studies of Randazzo et al. (2000) in which overexpression of ASAP1 delayed the spreading of NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. As shown in both studies, the inhibition of ASAP1 on cell spreading is dependent upon its GAP activity, based on the comparison of a GAP-deficient mutant with wild-type ASAP1. In addition, we provide evidence that the interaction with FAK appears to be functionally important because a mutant lacking the C-terminal SH3 domain affected cell spreading less substantially than wild-type ASAP1. Because cell spreading on fibronectin requires the rapid formation of new adhesion complexes and subsequent focal adhesion remodeling, the observed inhibition of cell spreading by ASAP1 is suggestive of a role of ARF GTPase activity in focal adhesion dynamics.

In an earlier study using a serum-starved streptolysin-O-permeabilized fibroblasts system, Norman et al. (1998) showed that paxillin recruitment to focal adhesions was dependent upon ARF1. Leakage of endogenous ARF from permeabilized cells coincided with the loss of GTPγS-stimulated redistribution of paxillin from perinuclear region to focal adhesions, whereas addition of ARF1 to the medium rescued paxillin redistribution. Our observation that ASAP1 overexpression perturbed paxillin localization to focal adhesions during cell spreading suggests that ASAP1 may regulate the assembly or organization of focal adhesions by modulating ARF1 activity in vivo. Using a cell-based ARF GAP assay, Furman et al. (2002) showed that ASAP1 functions as a GAP for ARF1 but not ARF6 in vivo, providing additional evidence with regard to the ARF specificity of ASAP1. The less potent impact on vinculin localization by ASAP1 overexpression indicates that regulatory proteins, such as paxillin or FAK, and structural proteins, such as vinculin, may be targeted to focal adhesions by different pathways. In addition of ASAP1, GIT1 also inhibits paxillin localization but not vinculin localization when overexpressed in cells (Zhao et al., 2000). Norman et al. (1998) also showed that the redistribution of vinculin to focal adhesions and that of paxillin responded differently to cells permeabilization and GTPγS addition, further implicating the existence of multiple recruitment pathways.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Paul A. Randazzo for generously providing antiserum 642 and mouse ASAP1 cDNA. We thank Ian G. Macara for sharing the mouse embryonic cDNA library, and Amy Bouton for anti-Cas serum. We thank Rick Horwitz, James Casanova, and members of the JTP laboratory for helpful discussion. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health-National Cancer Institute (grants CA40042, CA29243, and CA80606 to J.T.P.). K.H.M. was supported by a National Research Service Award NRSA (grant 1 F32 GM19795).

Abbreviations used:

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- ARF

ADP-ribosylation factor

- ASAP

ARF-GAP containing SH3, ankyrin repeats and PH domain

- Cas

Crk-associated substrate

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- FN

fibronectin

- FRNK

FAK-related nonkinase

- GAP

GTPase-activating protein

- GIT

G protein-coupled receptor kinase-interacting target

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- Pyk2

proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2

- PAP

Pyk2 C terminus-associated protein

- PH

pleckstrin homology

- PIX

PAK-interactive exchange factor

- PKL

paxillin kinase linker

- REF

rat embryo fibroblasts

- SH2

Src homology 2

- SH3

Src homology 3

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E02–01–0018. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E02–01–0018.

REFERENCES

- Andreev J, Simon JP, Sabatini DD, Kam J, Plowman G, Randazzo PA, Schlessinger J. Identification of a new Pyk2 target protein with Arf-GAP activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2338–2350. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel PL, Fields S. Analyzing protein-protein interactions using two-hybrid system. Methods Enzymol. 1995;254:241–263. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)54018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretscher MS. Getting membrane flow and the cytoskeleton to cooperate in moving cells. Cell. 1996;87:601–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81380-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MT, Andrade J, Radhakrishna H, Donaldson JG, Cooper JA, Randazzo PA. ASAP1, a phospholipid-dependent arf GTPase-activating protein that associates with and is phosphorylated by Src. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7038–7051. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge K, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M. Focal adhesions, contractility, and signaling. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:463–518. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge K, Fath K, Kelly T, Nuckolls G, Turner C. Focal adhesions: transmembrane junctions between the extracellular matrix and the cytoskeleton. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1988;4:487–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HC, Appeddu PA, Parsons JT, Hildebrand JD, Schaller MD, Guan JL. Interaction of focal adhesion kinase with cytoskeletal protein talin. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16995–16999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devarajan P, Stabach PR, De Matteis MA, Morrow JS. Na, K-ATPase transport from endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi requires the Golgi spectrin-ankyrin G119 skeleton in Madin Darby canine kidney cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10711–10716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson JG, Cassel D, Kahn RA, Klausner RD. ADP-ribosylation factor, a small GTP-binding protein, is required for binding of the coatomer protein β-COP to Golgi membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6408–6412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson JG, Klausner RD. ARF: a key regulatory switch in membrane traffic and organelle structure. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:527–532. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza-Schorey C, Boshans RL, McDonough M, Stahl PD, Van Aelst L. A role for POR1, a Rac1-interacting protein, in ARF6-mediated cytoskeletal rearrangements. EMBO J. 1997;16:5445–5454. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth WC, Bennett RG, Hamel FG. Insulin degradation: progress and potential. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:608–624. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.5.0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman C, Short SM, Subramanian RR, Zetter BR, Roberts TM. DEF-1/ASAP1 is a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) for ARF1 that enhances cell motility through a GAP-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7962–7969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Schiestl RH. Applications of high efficiency lithium acetate transformation of intact yeast cells using single-stranded nucleic acids as carrier. Yeast. 1991;7:253–263. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harte MT, Hildebrand JD, Burnham MR, Bouton AH, Parsons JT. p130Cas, a substrate associated with v-Src and v-Crk, localizes to focal adhesions and binds to focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13649–13655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand JD, Schaller MD, Parsons JT. Paxillin, a tyrosine phosphorylated focal adhesion-associated protein binds to the carboxyl terminal domain of focal adhesion kinase. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:637–647. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.6.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand JD, Taylor JM, Parsons JT. An SH3 domain-containing GTPase-activating protein for Rho and Cdc42 associates with focal adhesion kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3169–3178. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher A, Sandborg RR, Horwitz AF. Adhesion in cell migration. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:697–706. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joberty G, Petersen C, Gao L, Macara IG. The cell-polarity protein Par6 links Par3 and atypical protein kinase C to Cdc42. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:531–539. doi: 10.1038/35019573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RA, Gilman AG. The protein cofactor necessary for ADP-ribosylation of Gs by cholera toxin is itself a GTP binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:7906–7911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam JL, Miura K, Jackson TR, Gruschus J, Roller P, Stauffer S, Clark J, Aneja R, Randazzo PA. Phosphoinositide-dependent activation of the ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein ASAP1. Evidence for the pleckstrin homology domain functioning as an allosteric site. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9653–9663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo A, Hashimoto S, Yano H, Nagayama K, Mazaki Y, Sabe H. A new paxillin-binding protein, PAG3/Papα/KIAA0400, bearing an ADP- ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein activity, is involved in paxillin recruitment to focal adhesions and cell migration. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:1315–1327. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.4.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauffenburger DA, Horwitz AF. Cell migration: a physically integrated molecular process. Cell. 1996;84:359–369. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipfert L, Haimovich B, Schaller MD, Cobb BS, Parsons JT, Brugge JS. Integrin-dependent phosphorylation and activation of the protein tyrosine kinase pp125FAK in platelets. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:905–912. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma A, Richardson A, Schaefer EM, Parsons JT. Serine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase in interphase and mitosis: a possible role in modulating binding to p130Cas. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1–12. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman JC, Jones D, Barry ST, Holt MR, Cockcroft S, Critchley DR. ARF1 mediates paxillin recruitment to focal adhesions and potentiates Rho-stimulated stress fiber formation in intact and permeabilized Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1981–1995. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Martin KH, Slack JK, Taylor JM, Weed SA. Focal adhesion kinase: a regulator of focal adhesion dynamics and cell movement. Oncogene. 2000;19:5606–5613. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polte TR, Hanks SK. Complexes of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Crk-associated substrate (p130Cas) are elevated in cytoskeleton-associated fractions following adhesion and Src transformation. Requirements for Src kinase activity and FAK proline-rich motifs. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5501–5509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishna H, Donaldson JG. ADP-ribosylation factor 6 regulates a novel plasma membrane recycling pathway. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:49–61. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo PA, Andrade J, Miura K, Brown MT, Long YQ, Stauffer S, Roller P, Cooper JA. The Arf GTPase-activating protein ASAP1 regulates the actin cytoskeleton. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4011–4016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070552297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A, Parsons T. A mechanism for regulation of the adhesion-associated protein tyrosine kinase pp125FAK. Nature. 1996;380:538–540. doi: 10.1038/380538a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrschneider LR. Adhesion plaques of Rous sarcoma virus-transformed cells contain the src gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:3514–3518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller MD, Borgman CA, Cobb BS, Vines RR, Reynolds AB, Parsons JT. pp125FAK a structurally distinctive protein-tyrosine kinase associated with focal adhesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5192–5196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller MD, Hildebrand JD, Shannon JD, Fox JW, Vines RR, Parsons JT. Autophosphorylation of the focal adhesion kinase, pp125FAK, directs SH2- dependent binding of pp60src. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1680–1688. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller MD, Otey CA, Hildebrand JD, Parsons JT. Focal adhesion kinase and paxillin bind to peptides mimicking β integrin cytoplasmic domains. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:1181–1187. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.5.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller MD, Parsons JT. Focal adhesion kinase and associated proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:705–710. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MA, Shattil SJ. Signaling networks linking integrins and rho family GTPases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:388–391. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01605-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieg DJ, Hauck CR, Ilic D, Klingbeil CK, Schaefer E, Damsky CH, Schlaepfer DD. FAK integrates growth-factor and integrin signals to promote cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:249–256. doi: 10.1038/35010517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DB, Johnson KS. Single-step purification of polypeptides expressed in Escherichia coli as fusions with glutathione S-transferase. Gene. 1988;67:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Khachikian Z, Radhakrishna H, Donaldson JG. Localization of endogenous ARF6 to sites of cortical actin rearrangement and involvement of ARF6 in cell spreading. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2257–2267. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.15.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamnes MA, Rothman JE. The binding of AP-1 clathrin adaptor particles to Golgi membranes requires ADP-ribosylation factor, a small GTP-binding protein. Cell. 1993;73:999–1005. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90277-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana K, Sato T, D'Avirro N, Morimoto C. Direct association of pp125FAK with paxillin, the focal adhesion- targeting mechanism of pp125FAK. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1089–1099. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.4.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JM, Hildebrand JD, Mack CP, Cox ME, Parsons JT. Characterization of graf, the GTPase-activating protein for rho associated with focal adhesion kinase. Phosphorylation and possible regulation by mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8063–8070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JM, Macklem MM, Parsons JT. Cytoskeletal changes induced by GRAF, the GTPase regulator associated with focal adhesion kinase, are mediated by Rho. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:231–242. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CE, Brown MC, Perrotta JA, Riedy MC, Nikolopoulos SN, McDonald AR, Bagrodia S, Thomas S, Leventhal PS. Paxillin LD4 motif binds PAK and PIX through a novel 95-kD ankyrin repeat, ARF-GAP protein: a role in cytoskeletal remodeling. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:851–863. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weed SA, Du Y, Parsons JT. Translocation of cortactin to the cell periphery is mediated by the small GTPase Rac1. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2433–2443. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.16.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weed SA, Karginov AV, Schafer DA, Weaver AM, Kinley AW, Cooper JA, Parsons JT. Cortactin localization to sites of actin assembly in lamellipodia requires interactions with F-actin and the Arp2/3 complex. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:29–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods A, Couchman JR. Protein kinase C involvement in focal adhesion formation. J Cell Sci. 1992;101:277–290. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Reynolds AB, Kanner SB, Vines RR, Parsons JT. Identification and characterization of a novel cytoskeleton-associated pp60src substrate. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5113–5124. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZS, Manser E, Loo TH, Lim L. Coupling of PAK-interacting exchange factor PIX to GIT1 promotes focal complex disassembly. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6354–6363. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.17.6354-6363.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]