Abstract

Background

Dengue virus (DENV) infection, a mosquito-borne disease, presents a significant public health challenge globally, with diverse clinical manifestations. Although oral dengue manifestations are uncommon, they can serve as crucial diagnostic indicators and impact patient management in dental practice. This scoping review aims to map the evidence on the oral manifestations associated with DENV infection and their clinical implications for dental practice.

Methods

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines and was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022337572). A comprehensive search was conducted across six electronic databases (MEDLINE, Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, Cochrane Library, and LILACS/BBO) up to June 2024. Eligible studies included case reports, case-control, cohort, and cross-sectional studies reporting oral manifestations in patients with DENV infection.

Results

A total of 41 studies were included, comprising 17 case reports, 15 retrospective cohort studies, 4 prospective cohort studies, and 5 cross-sectional studies. Gingival bleeding, oral ulceration, bilateral inflammatory increase in the parotid glands, and lingual hematoma were the most frequently reported oral manifestations. Less common manifestations included Ludwig’s angina, osteonecrosis of the jaw, and angular cheilitis. These findings suggest a broad spectrum of oral symptoms that could aid in the early identification and management of dengue patients.

Conclusions

This review highlights the importance of recognizing oral manifestations in dengue patients, which can facilitate early diagnosis and intervention, particularly in dengue-endemic regions. Dental professionals play a crucial role in identifying these symptoms and improving patient outcomes. Further research is needed to explore the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying these manifestations and to develop standardized protocols for clinical assessment and management.

Clinical relevance

This paper highlights the role of dental professionals in early dengue diagnosis, emphasizing oral manifestations like gingival bleeding. It promotes interdisciplinary care, improving patient outcomes and management in dengue-endemic regions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12903-025-05504-6.

Keywords: Dengue virus, Oral manifestations, Dentistry, Oral medicine

Introduction

Dengue is a mosquito-borne viral disease that has been rapidly increasing across the globe in recent years, with at least 390 million estimated annual cases [1]. Dengue virus is from the Flaviviridae family, and there are five different serotypes that can infect human beings (DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, DENV-4, and DENV-5) [2]; However, the dengue disease has different epidemiological patterns worldwide, and often one serotype is transmitted to another region of the world through infected travelers, causing an alarming endemic from different serotypes of dengue. The primary infection vector for dengue virus (DENV) is the female mosquitoes of the species Aedes aegypti and A. albopictus [3]. These types of mosquitoes are prevalent in tropical and subtropical climates such as Southeast Asia, India, and Latin American countries [4].

DENV remains a critical public health challenge in Brazil, characterized by complex dynamics influenced by environmental, social, and virological factors. This disease has seen fluctuating patterns of incidence with periodic resurgences, notably post-Zika epidemic [5]. Recent data from 2023 highlights the introduction of new DENV lineages and a concerning increase in cases and fatalities, exacerbated by the overlapping impact of the COVID-19 pandemic [6, 7]. These developments emphasize the continued need for vigilant surveillance, vector control, and public health preparedness to manage and mitigate the impacts of dengue.

Most of the infections are estimated to be asymptomatic. Moreover, dengue fever can manifest mild flu-like symptoms, such as fever, nausea, muscle and joint pain, and headaches [8]. Although dengue fever is self-resolving, transitory thrombocytopenia is a common finding in blood screenings during the acute phase of the febrile illness. However, in the minority of the patients, complications emerge due to this reduction in the platelet count, evolving into more severe cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS). These stages of severe dengue fever are potentially lethal to the host due to coagulation abnormalities, plasma leakage, severe bleeding, respiratory distress, and fluid loss leading to hypovolemic shock and multi-organ failure [9].

Although oral manifestations of the dengue virus are considered uncommon [10], dental professionals should be able to identify oral symptoms related to DENV and give an early diagnosis of infected patients undergoing dental procedures. Commonly reported manifestations include gingival bleeding, oral ulceration, lingual hematoma, and bilateral inflammatory swelling of the parotid glands. From this perspective, this scoping review aims to retrieve all relevant data regarding the oral manifestations of DENV and critically analyze the clinical implications to dental practice and the oral outcomes related to this viral disease, giving insight to dental professionals as to how to manage the patient infected with DENV.

Materials and methods

Protocol registration and research question

This scoping review is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [11, 12], and the protocol for this study was registered a priori on the PROSPERO database (registration code: CRD42022337572).

The research question was developed within the population-concept-context (PCC) framework for scoping reviews: What are the oral manifestations (Concept) associated with patients with dengue virus infection (Population), and what are their clinical implications for dental practice (Context)?

Eligibility and exclusion criteria

Eligible studies were original articles that reported any oral manifestation directly related to dengue infection and its clinical outcome. The design of the included studies was limited to case reports, case-control, cohort, and cross-sectional studies.

In order to extract patient-level data, exclusion criteria were applied to in vitro and ex vivo studies, animal studies, gray literature, literature reviews, short commentaries, letters to the editor, and congress abstracts.

Information sources and search strategy

A search strategy was elaborated based on the combination of MEDLINE MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms related to dengue virus infection and oral health, and they were adapted for the other databases, respecting their syntax rules (Supplementary file 1). A total of 6 electronic databases were systematically searched until June 20th, 2024: MEDLINE (via PubMed), Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, Cochrane Library, and LILACS/BBO. Additionally, the references of eligible studies were manually verified to increase the pool of studies.

Selection process

The selection process began with a systematic search, and the resulting references were uploaded to Mendeley (Elsevier, Amsterdam, NE) to remove duplicates. These references were then transferred to Rayyan online software (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Doha, QA) [13] for further evaluation. In this phase, two independent reviewers performed a blind review of titles and abstracts. Once this initial review was completed, the blind was removed, and discrepancies were resolved through consultation with a third researcher. This selection process was based on established eligibility criteria. Studies that met these criteria or those that could not be conclusively assessed from the title and abstract were chosen for full-text review. Additionally, a manual search of the references from these selected studies was conducted to find other pertinent studies that the initial search might have missed.

Data collection process

Two independent reviewers extracted data from the eligible studies using a standardized Excel sheet (Microsoft, Redmond, USA). Subsequently, a third reviewer performed a double-check of the extracted data. The following information was collected: study characteristics (e.g., author, publication year, country, and study type), participant characteristics (e.g., sample size, age, gender), details of the dengue infection (e.g., serotype, geographic distribution, and transmission vector), information about the clinical manifestation of DENV (e.g., symptomatology and oral manifestations), and the outcome as reported by the studies.

Results

Search strategy

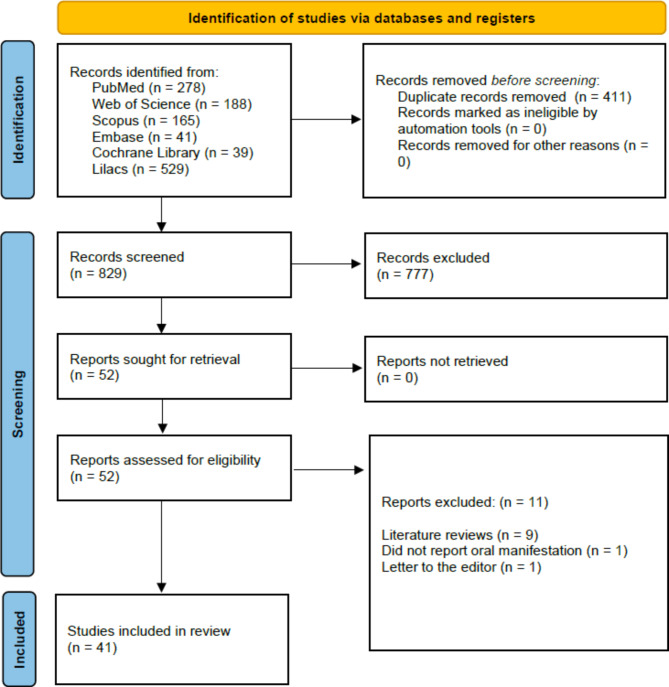

Figure 1 presents a flowchart detailing the study selection process for this review. The final systematic search across all databases was completed in July 2024, resulting in 1240 records. After removing 411 duplicates, the remaining records were screened based on titles and abstracts, leading to the exclusion of 777 records that did not meet the eligibility criteria. This left 52 studies for detailed full-text analysis. Of these, eleven were excluded for various reasons, such as being literature reviews, not reporting oral manifestations, or being letters to the editor. Ultimately, 41 studies met all the criteria and were included in this review.

Fig. 1.

Search flowchart according to the PRISMA 2020 statement

Study characteristics

We identified 41 studies that addressed the oral manifestations of dengue. Among these, 41% (17/41) were clinical case reports [14–30], 37% (15/41) were retrospective cohort studies [31–45], 10% (4/41) were prospective cohort studies [46–49], and 12% (5/41) were cross-sectional studies [50–54]. The included studies in this review originate from a diverse range of countries, reflecting the global impact of dengue fever. India contributes the highest number of studies with 13 publications [17, 21–27, 29, 30, 36, 39, 40] followed by Brazil with 6 studies [19, 28, 38, 43, 45, 50], Pakistan with 4 studies [41, 48, 53, 54], Mexico [32, 52], Bangladesh [34, 46] and Taiwan [35, 37] with 2 studies each. Additionally, Sri Lanka [47] is represented by a prospective cohort study. Other contributions include 1 study each from Colombia [51], Fiji [31], Venezuela [14], the United States [15], Yemen [16], Honduras [44], Japan [18], Cuba [42], Bolivia [20], China [33], and France [49], highlighting the widespread concern and varied research efforts addressing oral manifestations of dengue across different regions and populations.

The sample described in Table 1 encompasses a diverse group of patients affected by dengue. The studies collectively include thousands of participants (n = 42.817), with individual study sample sizes varying from single case reports to large cohort studies involving thousands of patients. The mean age range of participants, where specified, varied widely from 8 to 44 years. However, all age groups were represented, reflecting the broad range affected by dengue. Both genders were included across the studies, showing a balanced perspective on how dengue impacts males and females.

Table 1.

Study characteristics and oral manifestations

| Study characteristics | Participant characteristics | DENV characteristics | Oral manifestations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/Year | Study design | Sample size | Age | Gender | Serotype | Geographic distribution | Transmission vector | |

| Fagbami et al., 1995 | Retrospective cohort | 426 | All ages | Both genders | DENV-1 and DENV-2 | Fiji | Aedes albopictus | Gingival bleeding |

| Desruelles et al., 1997 | Retrospective cohort | 39 | All ages |

Both genders |

DENV-2 | Mexico | Aedes aegypti | Pharyngitis Erythematous Diffuse, Glossitis Depapillated, Gingival Bleeding and Purpura of the Palate |

| Vasconcelos et al., 1998 | Cross-sectional | 1341 | All ages | Both genders | DENV-2 | Brazil | Aedes aegypti | Gingival bleeding and epistaxis |

| Torres et al., 2000 | Case report | 1 | 55 years | Man | DENV-1 | Venezuela | Aedes aegypti | Bilateral inflammatory increase in the parotid glands |

| Ahmed et al., 2001 | Prospective cohort | 72 | Average 8 years old | N/A | Bangladesh | Aedes aegypti | Gingival bleeding | |

| Setlik et al., 2004 | Case report | 1 | 61 years | Woman |

DENV-1, DENV-2 and DENV-3 |

United States | Aedes aegypti | Oral ulceration |

| Díaz-Quijanoa et al., 2005 | Cross-sectional | 891 | Over 15 years old |

Both genders |

N/A | Colombia |

Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. |

Gingival bleeding |

| Malavige et al., 2006 | Prospective cohort | 104 | N/A | Both genders | N/A | Sri Lanka | Aedes aegypti | Oral candidiasis |

|

Ramırez-Zepeda et al., 2009 |

Cross-sectional | 241 |

Average 34 years old |

Both genders | N/A | Mexico | Aedes aegypti |

Gingival bleeding |

| Ribeiro et al., 2010 | Retrospective cohort | 4818 | All ages | Both genders | DENV-1, DENV-2 and DENV-3 | Brazil | Aedes aegypti | Gingival bleeding |

| Bhaskar et al., 2010 | Retrospective cohort | 128 | Average 33 years old | Both genders | N/A | India | Aedes aegypti | Gingival bleeding |

| Kumar et al., 2010 | Retrospective cohort | 466 | N/A | Both genders | N/A | India | Aedes aegypti | Gingival bleeding |

| Sarkar et al., 2011 | Case report | 1 | N/A | Man | N/A | India | Aedes mosquito | Lingual hematoma causing upper airway obstruction |

|

Mahboob et al., 2012 |

Prospective cohort | 60 | All ages | Both genders | N/A | Pakistan | Aedes mosquito | Oral mucous membrane congestion |

| Sheikh et al., 2012 | Cross-sectional | 109 | All ages | Both genders | N/A | Pakistan | Aedes mosquito | Diffuse erythema, candidiasis and oral aphthae |

| Azfar et al., 2012 | Cross-sectional | 300 | All ages | Both genders | N/A | Pakistan | Aedes mosquito |

Erythema of the buccal mucosa and palate |

| Mithra et al., 2013 | Case Report | 1 | N/A | Female | N/A | India | Aedes aegypti |

Bilateral submandibular Lymphadenopathy, hemorrhagic plaques blue mucosa area of erosion tonsils inflamed. xerostomia and the tongue appeared to be coated. |

| Dubey et al., 2013 | Case report | 1 | 20-year-old | Male | N/A | India | Aedes aegypti | Gingival bleeding |

| Ahmed et al., 2013 | Retrospective cohort | 640 | All ages | Both genders | DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4 | Pakistan | Aedes mosquito | Gingival bleeding |

| Khan et al., 2013 | Case report | 1 | 18 years | Male | N/A | India | Aedes aegypti | Gingival bleeding |

| Byatnal et al., 2013 | Case report | 1 | 50 years | Female | N/A | India | Aedes aegypti | Gingival bleeding |

| Pontes et al., 2014 | Case report | 1 | 18 years | Male | N/A | Brazil | Aedes aegypti | Gingival and lip reddish swelling |

| Bansal et al., 2014 | Case report | 1 | 40 years | N/A | India | Aedes aegypti | Gingival bleeding | |

| Brito, 2014 | Retrospective cohort | 997 | N/A | Both genders | N/A | Cuba | Aedes aegypti | Gingival bleeding |

| Indurkar and Sethi, 2015 | Case report | 1 | 46 years | N/A | India | Aedes aegypti | Osteonecrosis of the jaw | |

| Pone et al., 2016 | Retrospective cohort | 145 | Under 18 years | Both genders | N/A | Brazil | Aedes aegypti | Gingival bleeding |

| Al-Namnam et al., 2016 | Case report | 1 | 30 years | Both genders | N/A | Yemen | Aedes aegypti |

Maxillary osteonecrosis, periodontitis with root resorption |

| Bhardwaj et al., 2016 | Case report | 1 | 19 years | Male | N/A | India | Aedes aegypti |

Blisters in mouth, soreness on the gums, alveolar mucosa on soft palate, and difficulty in swallowing |

| Fernandez et al., 2016 | Retrospective cohort | 390 | Average 21 years | Both genders | N/A | Honduras | Aedes aegypti | Gingival bleeding |

| Yamamoto, 2019 | Case report | 1 | 6 years | Male | DENV-1 | Japan | Aedes aegypti |

Submucosal hemorrhages on the hard palate and rose-colored spots on the soft palate |

| Barros et al., 2020 | Retrospective cohort | 1,003 | All ages | Both genders | N/A | Brazil | Aedes aegypti | Ulcerative stomatitis |

| Fernandes, et al., 2020 | Case report | 1 | 29 year | Female | N/A | Brazil | Aedes aegypti |

Gingival bleeding, maculopapular lesions, erythema, petechiae and ecchymoses |

| Cossaboom et al., 2020 | Case report | 5 |

65, 25, 22, 48 years Case 5: N/A |

Male | N/A | Bolivia | Aedes aegypti | Gingival hemorrhage |

| Wang et al., 2021 | Retrospective cohort | 718 | All ages | Both genders | N/A | China | Aedes aegypti | Dry mouth |

| Khan et al., 2021 | Retrospective cohort | 190 | Under 15 years | Both genders | DENV-1 | Bangladesh | Aedes aegypti | Mouth sores |

| Chang et al., 2021 | Retrospective cohort | 29,365 |

Average 44 years |

Both genders | N/A | Taiwan | Aedes aegypti | Sjogren’s syndrome |

| Shang et al., 2021 | Retrospective cohort | 105 | All ages | Both genders | N/A | Taiwan | Aedes aegypti | Gingival bleeding |

| Dronamraju et al., 2022 | Case report | 1 | 31 years | Female | N/A | India | Aedes aegypti | Ludwig’s angina |

| Randhawa et al.,2023 | Retrospective cohort | 84 | Under 12 years | Both genders | N/A | India | Aedes aegypti | Oral mucosal changes |

| Fera et al., 2023 | Prospective cohort | 163 | N/A | Both genders | N/A | France | Aedes aegypti |

Mouth involvement including lip, tongue, cheek, angular cheilitis, pharyngitis, mouth ulcer and gingivitis |

| Das et al., 2024 | Case report | 2 | 30 years and 43 years | Male | DENV-1 | India | Aedes aegypti | Oral/oro-pharyngeal pseudomembranous candidiasis |

DENV-1: Dengue virus serotype 1; DENV-2: Dengue virus serotype 2; DENV-3: Dengue virus serotype 3; DENV-4: Dengue virus serotype 4; DF: Dengue fever; DHF: Dengue hemorrhagic fever; N/A: Not applicable

The distribution of DENV serotypes across the studies showed that DENV-2 was the most frequently reported, accounting for 20% (8/41) of the studies, followed by combinations of DENV-1 and DENV-2 at 5% (2/41) and DENV-1, DENV-2, and DENV-3 at 7% (3/41). A single study, reported all four serotypes (DENV-1 to DENV-4), while the serotype was unspecified in 66% (27/41) of the studies. Geographically, the studies were concentrated in tropical and subtropical regions as shown in Fig. 2. By continent, Asia accounted for 61% (25/41) of the studies, followed by South America with 22% (9/41), North America with 7% (3/41), Central America with 5% (2/41), Oceania and Europe with 2% (1/41) each; no studies were reported from Africa. Within countries, Brazil and India were the most represented countries. Regarding transmission vectors, Aedes aegypti was identified as the primary vector in 78% (32/41) of the studies, Aedes albopictus in 5% (2/41), and a combination of both vectors in 17% (7/41). These findings emphasize the global variability in DENV serotypes, the regional burden of disease, and the transmission dynamics.

Fig. 2.

Global map showing the distribution of DENV studies. Search flowchart according to the PRISMA 2020 statement

Table 1 presents a wide array of oral manifestations associated with DENV infections. Gingival bleeding emerged as the most frequently reported symptom (51%), documented in 21 studies across various countries. Other notable oral manifestations included oral ulcerations (10%), often severe enough to cause significant discomfort or complications; pharyngitis (10%); and oral/oropharyngeal pseudomembranous candidiasis (7%).

Additional symptoms, such as bilateral inflammatory swelling of the parotid glands, indicating systemic involvement, and lingual hematoma, which can obstruct the upper airways, were also reported. Other manifestations included hemorrhagic plaques, blue mucosa, submucosal hemorrhages on the hard palate, pink spots on the soft palate, and Ludwig’s angina, highlighting the diverse and often severe nature of oral involvement in dengue cases. Further documented findings, such as osteonecrosis of the jaw and angular cheilitis, underscore the importance of comprehensive oral examinations in patients with dengue.

Discussion

This scoping review identified 41 studies that discussed various aspects of oral manifestations related to DENV infection. Among these, 17 were clinical case reports, 15 were retrospective cohort studies, 4 were prospective cohort studies, and 5 were cross-sectional studies. The oral manifestations most frequently reported in the included studies were gingival bleeding, oral ulceration, bilateral inflammatory increase in the parotid glands, and lingual hematoma. Gingival bleeding emerged as the most common oral manifestation, reported in multiple studies across various countries, reflecting a potential diagnostic clue for DENV infection in clinical practice. Dengue is characterized by thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy, which increase bleeding tendencies, making the highly vascularized and easily irritated gingival tissues particularly susceptible to spontaneous bleeding [55–57]. Additionally, oral ulcers may arise from immune dysregulation triggered by DENV, involving the activation of inflammatory cytokines and immune cells that cause mucosal damage [58]. Systemic effects of dengue, such as dehydration and nutritional deficiencies, further exacerbate mucosal fragility, compounding the vulnerability of oral tissues [59]. The variation in clinical presentation, ranging from mild symptoms like gingival bleeding to more severe manifestations such as osteonecrosis of the jaw and Ludwig’s angina, highlights the complexity of oral involvement in dengue cases and the importance of early diagnosis and comprehensive management. These manifestations are likely due to the combination of direct viral effects, immune-mediated tissue damage, and systemic complications like thrombocytopenia and vascular leakage, which are hallmarks of severe dengue infection.

The findings align with previous reviews, such as the study by Pedrosa et al. (2017) [10], which also identified gingival bleeding as a prevalent oral manifestation of dengue fever. However, our review expands upon earlier work by including recent studies that report additional, previously undocumented oral symptoms. For instance, Ludwig’s angina has been associated with dengue due to the immunosuppressed state caused by the virus, which predisposes patients to severe infections [21]. Furthermore, new associations such as Sjögren’s syndrome, identified in recent studies [35], suggest potential autoimmune implications of DENV infections. These novel findings underscore the evolving understanding of the diverse oral manifestations associated with dengue and the need for continuous surveillance and research to understand the full spectrum of symptoms better.

The wide range of oral symptoms associated with DENV may stem from several factors, including the complexity of the disease’s pathophysiology, variability in patient immune responses, and differences in diagnostic practices across regions [60]. Misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis of dengue, particularly in endemic areas with common febrile illnesses, may also contribute to the observed variability in reported symptoms [6]. For example, conditions such as Ludwig’s angina might initially be attributed to other causes until a definitive dengue diagnosis is made, reflecting a gap in clinical awareness and timely recognition of DENV’s impact on oral health [60]. It is essential for healthcare providers, especially dental professionals in dengue-endemic regions like Asia and South America, to be well-versed in the oral manifestations of dengue. This knowledge will facilitate early differential diagnosis and prompt intervention, potentially improving patient outcomes by preventing the progression to more severe stages of the disease.

This review highlights several controversies that warrant further investigation. The variability in reported oral manifestations, ranging from common symptoms such as gingival bleeding to rare findings like Ludwig’s angina and Sjögren’s syndrome, raises concerns about the consistency of diagnostic practices and reporting standards across regions and studies. While immune dysregulation and thrombocytopenia are proposed as explanations, the mechanisms underlying severe cases like osteonecrosis of the jaw remain speculative and require more robust evidence. Additionally, diagnostic gaps and potential misdiagnoses, particularly in endemic regions, emphasize the need for enhanced clinical awareness and education. These controversies underscore the need for large-scale, multicenter studies to validate findings, elucidate mechanisms, and develop standardized diagnostic and management protocols.

Dental professionals’ early identification of oral manifestations can significantly contribute to the early diagnosis of dengue, thereby improving patient outcomes. Recognizing symptoms such as gingival bleeding, oral ulceration, and mucosal changes as potential indicators of dengue can prompt timely referral for medical evaluation and appropriate management, which is crucial in preventing severe complications like DHF and DSS. This underscores the importance of comprehensive training and awareness among dental practitioners regarding the signs of DENV infection. Additionally, dentists should remain vigilant when considering potential diagnoses, as medications must be prescribed with caution. For patients with suspected dengue, the use of non-essential drugs—particularly anti-inflammatories, antibiotics, and medications with renal, hepatic, or hematologic toxicity—is not recommended, in accordance with World Health Organization guidelines [4].

It is important to highlight that this review expanded the literature search compared to the last published review by utilizing six databases. Although this review provides valuable insights into the oral manifestations of dengue, limitations must be acknowledged. The reliance on case reports and cohort studies introduces variability in the quality of evidence [61], and the geographic distribution of studies may not fully capture the global diversity of DENV’s clinical presentation. The exclusion of gray literature ensured the inclusion of high-quality, peer-reviewed evidence to enhance reliability and standardization. However, this decision may have introduced some publication bias. To address this, we conducted a manual reference search and adhered to a transparent methodology. Additionally, a quality assessment was not performed, as the primary objective of this scoping review was to map the available evidence. Future research should focus on large-scale, multicenter studies to validate these findings and explore the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the oral manifestations of dengue.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the timely diagnosis of dengue through the recognition of oral manifestations is crucial in mitigating the impact of this disease. Dental professionals play a pivotal role in identifying early signs of DENV infection, especially in endemic regions. Future research should aim to elucidate the pathogenesis of oral manifestations associated with dengue and develop standardized protocols for clinical assessment and management. Enhanced education and awareness programs for healthcare professionals are recommended to strengthen early detection and improve patient care outcomes in the context of dengue fever.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

LPA, SKW, and ETC drafted the main manuscript and conducted the initial analysis. BCC and MAK reviewed the analysis and contributed to data extraction. NKW and SAK reviewed the final manuscript and provided support for the methodology.

Funding

This research received no grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496(7446):504–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mustafa MS, Rasotgi V, Jain S, Gupta V. Discovery of fifth serotype of dengue virus (denv-5): a new public health dilemma in dengue control. Med J Armed Forces India. 2015;71(1):67–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mutheneni SR, Morse AP, Caminade C, Upadhyayula SM. Dengue burden in India: recent trends and importance of climatic parameters. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2017;6(8):e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control. WHO/HTM/NTD/DEN/2009.1 (World Health Organization, 2009). [PubMed]

- 5.Brito AF, Machado LC, Oidtman RJ, Siconelli MJL, Tran QM, Fauver JR, et al. Lying in wait: the resurgence of dengue virus after the Zika epidemic in Brazil. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naveca FG, Santiago GA, Maito RM, Meneses CAR, do Nascimento VA, de Souza VC, et al. Reemergence of Dengue Virus Serotype 3, Brazil, 2023. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29(7):1482–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Souza CS, Romano CM. Dengue in the cooling off period of the COVID-19 epidemic in Brazil: from the shadows to the spotlight. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2022;64:e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rathore SJAL. Adaptive immune responses to primary and secondary dengue virus infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19(4):218–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatt P, Sabeena SP, Varma M, Arunkumar G. Current understanding of the pathogenesis of Dengue Virus infection. Curr Microbiol. 2021;78(1):17–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MS P M, de Oliveira P, Pereira L, C da S S, Pompeu J. Oral manifestations related to dengue fever: a systematic review of the literature. Aust Dent J. 2017;62(4):404–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torres JR, Liprandi F, Goncalvez AP. Acute parotitis due to dengue virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(5):E28–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Setlik RF, Ouellette D, Morgan J, Kenneth McAllister C, Dorsey D, Agan BK, et al. Pulmonary hemorrhage syndrome associated with an autochthonous case of dengue hemorrhagic fever. South Med J. 2004;97(7):688–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Namnam NM, Nambiar P, Shanmuhasuntharam P, Harris M. A case of dengue-related osteonecrosis of the maxillary dentoalveolar bone. Aust Dent J. 2017;62(2):228–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhardwaj VK, Negi N, Jhingta P, Sharma D. Oral manifestations of dengue fever: a rarity and literature review. Eur J Gen Dent. 2016;5(2):95–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto K. Images in clinical tropical medicine: oral manifestation like forchheimer spots of dengue fever. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;101(4):729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandes CIR, Perez LE da C, Perez DE da C. Uncommon oral manifestations of dengue viral infection. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;86(xx):3–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cossaboom C, Medina Ramirez A, Romero C, Morales-Betoulle M, de la Vega GA, Gutiérrez JTM, et al. Re-emergence of Chapare hemorrhagic fever in Bolivia, 2019. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;101(June 2019):244–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dronamraju S, Acharya S, Jain S, Bagga C, Kumar S. Ludwig’s angina after severe thrombocytopenia associated with dengue fever in a primigravida: a case report. Med Sci. 2022;26(119):1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das D, Sahu SN, Panda PK, Panda M. Oro-pharyngeal candidiasis in two dengue patients. Cureus. 2024;16(1):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarkar J, Mohan C, Misra DN, Goel A. Lingual hematoma causing upper airway obstruction: an unusual manifestation of dengue fever. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2011;4(5):412–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mithra R, Baskaran P, Sathyakumar M. Oral presentation in dengue hemorrhagic fever: a rare entity. J Nat Sci Biology Med. 2013;4:264–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dubey P, Kumar S, Bansal V, Kumar KVA, Mowar A, Khare G. Postextraction bleeding following a fever: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115(1):e27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan S, Gupta ND, Maheshwari S. Acute gingival bleeding as a complication of dengue hemorrhagic fever. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17(4):520–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Byatnal A, Mahajan N, Koppal S, Ravikiran A, Thriveni R, Devi MKP. Unusual yet isolated oral manifestations of persistent thrombocytopenia - A rare case report. Brazilian J Oral Sci. 2013;12(3):233–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pontes FSC, Frances LTM, Carvalho M, de Fonseca V, Neto FP, do Nascimento NC. Severe oral manifestation of dengue viral infection: a rare clinical description. Quintessence Int. 2014;45(2):151–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bansal R, Goyel P, Agarwal D. Bleeding from gums: can it be a dengue. Dent Hypotheses. 2014;5(3):121–3. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Indurkar M, Sethi R. An unusual case of osteonecrosis of the jaw associated with dengue fever and periodontitis. Aust Dent J. 2016;61(1):113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fagbami AH, Mataika JU, Shrestha M, Gubler DJ. Dengue type 1 epidemic with haemorrhagic manifestations in Fiji, 1989-90. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73(3):291–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Desruelles F, Lamaury I, Roudier M, Goursaud R, Mahé A, Castanet J, et al. Manifestations cutaneo-muqueuses de la dengue. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1997;124(3):237–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J, Chen Q, Jiang Z, Li X, Kuang H, Chen T, et al. Epidemiological and clinical analysis of the outbreak of dengue fever in Zhangshu City, Jiangxi Province, in 2019. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;40(1):103–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khan MAS, Al Mosabbir A, Raheem E, Ahmed A, Rouf RR, Hasan M, et al. Clinical spectrum and predictors of severity of dengue among children in 2019 outbreak: a multicenter hospital-based study in Bangladesh. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang CC, Yen YC, Lee CY, Lin CF, Huang CC, Tsai CW, et al. Lower risk of primary Sjogren’s syndrome in patients with dengue virus infection: a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40(2):537–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Randhawa MS, Angurana SK, Nallasamy K, Kumar M, Ravikumar N, Awasthi P, et al. Comparison of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome (MIS-C) and Dengue in Hospitalized Children. Indian J Pediatr. 2023;90(7):654–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shang JT, Wang YY, Chang HY, Lo CL, Chen YH, Chien CI. The relationship between symptoms and nursing diagnoses in hospitalized patients with dengue fever. J Nurs. 2021;68(4):32–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ribeiro V, Angerami R, Resende M, Pavan MH, Hoehne E, Souza V, et al. Dengue fever in a Southeastern region of Brazil. Ten years period (1997–2007) clinical and epidemiological retrospective study. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(Icid):e384.19781971 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emmanuel Bhaskar M, Moorthy S, Senthil Kumar N, Arthur P. Dengue haemorrhagic fever among adults - an observational study in Chennai, South India. Indian J Med Res. 2010;132(12):738–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar A, Rao CR, Pandit V, Shetty S, Bammigatti C, Samarasinghe CM. Clinical manifestations and trend of dengue cases admitted in a tertiary care hospital, Udupi District, Karnataka. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35(3):386–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmed S, Mohammad WW, Hamid F, Akhter A, Afzal RK, Mahmood A. The 2011 dengue haemorrhagic fever outbreak in lahore - an account of clinical parameters and pattern of haemorrhagic complications. J Coll Physicians Surg Pakistan. 2013;23(7):463–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brito AE. Fiebre hemorrágica dengue. Estudio clínico en pacientes adultos hospitalizados Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. Clinical study of hospitalized adult patients. MediSur. 2015;12(4):570–91. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pone SM, Hökerberg YHM, de Oliveira R, de VC, Daumas RP, Pone TM, Pone MV da. Sinais clínicos e laboratoriais para o dengue com evolução grave em crianças hospitalizadas. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2016;92(5):464–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernández E, Smieja M, Walter SD, Loeb M. A predictive model to differentiate dengue from other febrile illness. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barros AMI, Martins-De-barros AV, Costa MJF, Sette-De-souza PH, de Lucena EE. Araújo FA Da C. Prevalence of ulcerative stomatitis in arbovirus infections in a Brazilian northeast population. Med Oral Patol Oral y Cir Bucal. 2020;25(6):e810–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmed FU, Mahmood CB, Sharma J, Das, Hoque SM, Zaman R, Hasan MS. Dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever in children during the 2000 outbreak in Chittagong, Bangladesh. Dengue Bull. 2001;25(2):33–9. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malavige GN, Ranatunga PK, Velathanthiri VGNS, Fernando S, Karunatilaka DH, Aaskov J, et al. Patterns of disease in Sri Lankan dengue patients. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(5):396–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahboob A, Iqbal Z, Javed R, Taj A, Munir A, Saleemi MA, et al. Dermatological manifestations of dengue fever. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2012;24(1):52–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fera C, Maillard O, Joly E, Diallo K, Mavingui P, Koumar Y, et al. Descriptive and comparative analysis of mucocutaneous manifestations in patients with dengue fever: a prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2024;38(1):191–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vasconcelos PFC, Lima JWO, Travassos da Rosa APA, Timbó MJ, Travassos da Rosa ES, Lima HR, Rodrigues SG, Travassos da Rosa JFS. Epidemia de dengue em Fortaleza, Ceará: inquérito soro-epidemiológico aleatório. Rev Saúde Pública. 1998;32(5):447–54. 10.1590/S0034-89101998000500007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Díaz-Quijano FA, Martínez-Vega RA, Villar-Centeno LÁ. Indicadores Tempranos De Gravedad en El dengue. Enferm infecc microbiol clín. (Ed Impr). 2005;23(9):529–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramírez-Zepeda MG, Velasco-Mondragón HE, Ramos C, Peñuelas JE, Maradiaga-Ceceña MA, Murillo-Llanes J, et al. Caracterización clínica Y epidemiológica De Los casos de dengue: Experiencia Del hospital general de culiacán, sinaloa, México. Rev Panam Salud Publica/Pan Am J Public Heal. 2009;25(1):16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sheikh KR, Shehzad A, Mufti S, Mirza UA, Shamsuddin. Skin involvement in patients of dengue fever during the 2011 epidemic in Lahore, Pakistan. J Pakistan Assoc Dermatologists. 2012;22(4):325–30. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Azfar NA, Malik LM, Jamil A, Jahangir M, Tirmizi N, Majid A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in patients of dengue fever. J Pakistan Assoc Dermatologists. 2012;22(4):320–4. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shang JT, Wang YY, Chang HY, Lo CL, Chen YH, Chien CI. The relationship between symptoms and nursing diagnoses in hospitalized patients with Dengue Fever. Hu Li Za Zhi. 2021;68(4):32–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Quirino-Teixeira AC, Andrade FB, Pinheiro MBM, Rozini SV, Hottz ED. Platelets in dengue infection: more than a numbers game. Platelets. 2021;33(2):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shabir MM, Nisar S, Urooj Z, Sohail M, Khan MS, Khan DH. Thrombocytopenia and its relationship with bleeding manifestations in Dengue Patients-A Tertiary Care Hospital Experience. Pakistan Armed Forces Med J. 2022;72(6):2021–4. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lai S, Huang Z, Zhou H, Anders KL, Perkins TA, Yin W, et al. The changing epidemiology of dengue in China, 1990–2014: a descriptive analysis of 25 years of nationwide surveillance data. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Utzinger J, Becker SL, Knopp S, Blum J, Neumayr AL, Keiser J, et al. Neglected tropical diseases: diagnosis, clinical management, treatment and control. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142(4748):w13727–13727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Luo L, Jiang LY, Xiao XC, Di B, Jing QL, Wang SY, et al. The dengue preface to endemic in mainland China: the historical largest outbreak by Aedes albopictus in Guangzhou, 2014. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cuffe RL. The inclusion of historical control data may reduce the power of a confirmatory study. Stat Med. 2011;30(12):1329–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].