Abstract

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a lymphoproliferative disease with significant variation in disease progression, response to therapy, and survival outcome. Deletions of 17p or mutations of TP53 have been identified as one of the poorest prognostic factors, being predictive of short time for disease progression, lack of response to therapy, short response duration, and short overall survival. The treatment of patients with CLL has improved significantly with the development of chemoimmunotherapy, but this benefit was not pronounced in patients with 17p deletion. We compare various treatment strategies used in these patients, including FCR-like chemoimmunotherapy, alemtuzumab, other antibody combinations, or novel targeted therapies with promising results. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation offers the possibility for long-term disease control in these patients and should be considered early in younger, transplant-eligible patients. The current state of therapy is far from optimal and resources should be applied to studying therapeutic options for patients who have CLL with loss of p53 function.

Keywords: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, p53, TP53, Frontline treatment, del(17p), Prognosis, Alemtuzumab, Combination therapies, Allogeneic stem cell transplantation, AlloSCT

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a disease of proliferation and accumulation of aberrant monoclonal B lymphocytes with defective cell death mechanisms. Although much remains to be understood about the etiology and pathophysiological mechanisms underlying CLL, there is accumulating knowledge of the genetic and epigenetic mechanisms underlying CLL cell survival. Our understanding of the cytogenetic abnormalities in CLL is shaping the future of therapy toward developing both targeted therapies for specific CLL subtypes and risk-adapted strategies for treatment. This is particularly true for patients with deletion or mutations of TP53.

The prognosis for patients with CLL requiring treatment has improved significantly with the advent of chemoimmunotherapy [1••]. There has been a progressive improvement in outcome from therapy using chlorambucil or an alkylating agent through the development of fludarabine monotherapy to the combination of purine analogue and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. The addition of rituximab to this combination therapy has further improved survival for most patients with CLL [2••, 3•], although patients with deletion or mutation of TP53 remain a high-risk group with a lower rate of response to frontline and salvage therapy, shorter remission duration, and shorter overall survival. Indeed, the most appropriate frontline therapy for this subgroup of patients has not been clearly defined. We review the treatment of patients with 17p deletion and describe novel mechanisms with therapeutic promise for this poor-prognosis, high-risk group.

P53 Structure and Function

The tumor suppressor protein, p53, was shown to play a critical role in oncogenesis and response to chemotherapy in a variety of human cancers. In humans, the TP53 gene is found on the short arm of chromosome 17 (17p13) [4] and is reported to be suppressed or mutated in over 50% of human cancers [5].

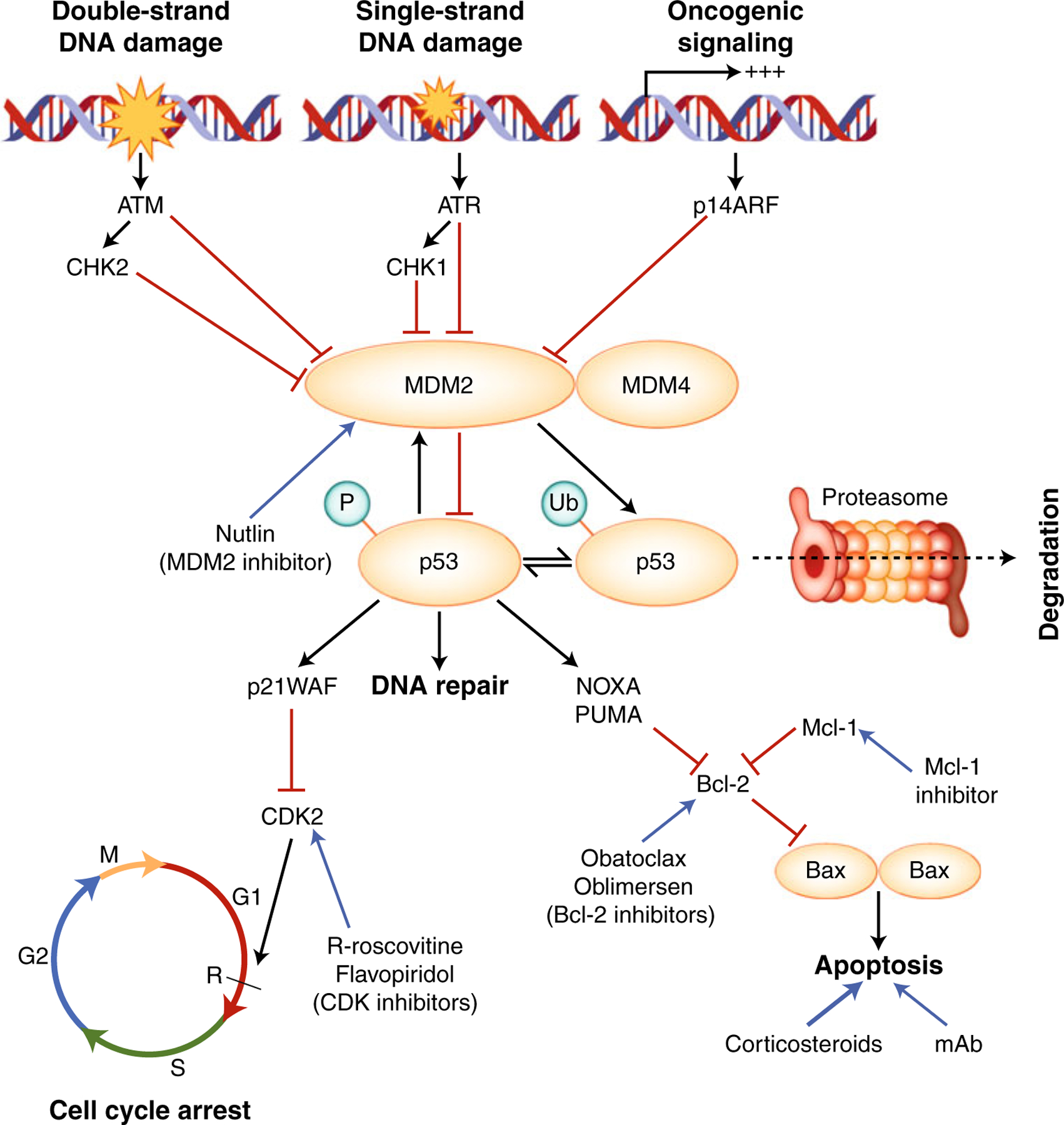

The p53 protein is upregulated in response to DNA damage, oxidative stress, heat stress, and other types of cellular injury (Fig. 1) [6]. The p53 protein plays an integral role in cellular response to DNA damage induced by UV radiation, cytotoxic agents, or radiotherapy. The response to DNA damage is mediated by signal transduction molecules such as ATM (Ataxia-Telangiectasia Mutated) or ATR (AT and Rad3-related), modulated by the serine/threonine-protein checkpoint kinases CHK2 or CHK1, respectively [7]. The interaction of ATM with p53 is of particular importance in CLL, as deletion of ATM (located at 11q23) is identified in 10% to 20% of CLL patients prior to therapy [8], thereby leading to dysfunctional p53 response following double-stranded DNA breaks. The p53 protein is also a potent tumor suppressor, which responds to oncogenic signaling via the signal transduction protein and MDM2-inhibitor, p14ARF (CDKN2 locus Alternative Reading Frame) [9]. Through these mechanisms, p53 is able to induce cell repair mechanisms or eventual apoptosis of cells following irreparable DNA or cellular injury.

Fig. 1.

Function of p53 protein and potential drug targets for p53-independent apoptosis induction. Black arrows indicate stimulatory interactions, red horizontal bars instead of arrowheads indicate inhibitory influences. The p53 protein is upregulated in response to DNA damage and oncogenic signaling via ATM/CHK2 (double-stranded DNA damage), ATR/CHK1 (single-stranded DNA damage) or p14ARF (oncogenic signaling). This process occurs by inhibition of Mdm2 and Mdm4, which inhibit p53 via ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, or by inhibition of p53 function. P53 induces Mdm2 transcription, leading to negative feedback inhibition of p53. When activated, p53 induces cell cycle arrest by inducing p21WAF and promotes transcription of genes involved in DNA repair. If the mechanisms of DNA repair fail, p53 induces apoptosis via upregulation of a number of genes, including PUMA, NOXA, and Bax. Some drugs currently under investigation that demonstrate activity in cells with dysfunctional p53 mechanisms are shown (blue). ATM—ataxia-telangiectasia mutated; ATR—AT and Rad3-related; Bcl—B-cell lymphoma; CDK—cyclin-dependent kinase; CHK—checkpoint kinase; mAb—monoclonal antibodies; MDM—murine double minute; P—phosphorylation; PUMA—p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis; Ub: ubiquitinated lysines

Regulation of p53 concentration and activity occurs through an important negative-feedback interaction with the E3 ubiquitin ligase, MDM2 (Murine-double minute 2 or its human homologue, HDM2) [10]. MDM2 binds p53, reduces its ability to bind DNA target sequences, and promotes the transport of p53 from the nucleus to the cytosol. In addition, MDM2 shortens the half-life of p53 by ubiquitination, consequently targeting the p53 protein for proteasome degradation [11]. Through the action of MDM2 and other regulators, the steady-state half-life of p53 in normal cells in their physiological environment is short (about 20 minutes). The level of p53 is increased and its function is activated via phosphorylation and deactivation of MDM2 induced by ATM, ATR, or ARF. Overexpression of MDM2 has also been reported in CLL and is an important area for drug development: MDM2 inhibitors such as nutlins may be useful in patients with p53 dysfunction not related to p53 deletion [12, 13].

The tumor suppressor functions of p53 are mediated via induction of cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, and apoptosis. In response to cellular injury, p53 induces cell cycle arrest via p21WAF1 (Wild-type p53 Activated Fragment), which in turn inactivates the cell cycle regulator, cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), usually responsible for transition of the cell cycle from the G1 phase to the S phase [6, 7, 14]. Cell cycle arrest is followed by induction of a number of cellular and DNA repair enzymes. If DNA repair fails, p53 may induce cell death via mitochondria-based apoptotic mechanisms. This process is mediated by Bax (Bcl-2 associated protein X) and can be down-modulated by Bcl-2 (B-cell lymphoma 2) [15, 16]. The role of Bcl-2 is of particular relevance in lymphoproliferative disorders and CLL, in which Bcl-2 upregulation has been implicated in the survival advantage of cells and has been associated with decreased response to therapy [16, 17]. Therefore, p53 is critical to the DNA integrity of cells, the prevention and control of malignancy, and the response to cytotoxic agents.

CLL and p53 Abnormalities

The prognosis of CLL is highly variable and dependent on a number of genetic and other biologic factors [8]. One of the strongest factors determining prognosis in CLL is the presence of del(17p) or mutation of TP53 [18]. Although cytogenetic abnormalities have long been known to be important to the prognosis of CLL, difficulty in obtaining metaphase karyotype in CLL has limited analysis of the impact of del(17p13) (containing the TP53 gene) on the prognosis of CLL [19–23]. About 5% of patients with CLL are noted to have abnormalities of chromosome 17 by conventional cytogenetic analysis prior to therapy [21, 23, 24]. Mutations in the TP53 gene as identified by gene sequencing may also be important determinants of survival in CLL [25–27]. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) has increased the sensitivity of detecting genomic abnormalities when compared with metaphase karyotype in CLL. Using FISH, approximately 4% to 9% of patients with CLL were noted to harbor del(17p13) at diagnosis and first therapy [18]. Over 80% of patients with del(17p) have concomitant TP53 mutations identified by gene sequencing, and an additional 4% to 5% of patients were noted to have TP53 mutations without the presence of del(17p) [28•, 29]. In patients with relapsed and refractory CLL, 17p abnormalities are more prevalent: del(17p) or TP53 mutations have been identified in up to 50% of patients with refractory CLL.

Prognosis of Patients with CLL With Del(17p) at Diagnosis

Del(17p) and mutations in TP53 have both been associated with poor survival and shorter time from diagnosis to treatment [18, 30•, 31], but the presence of del(17p) in patients with CLL with early-stage disease does not universally portend a poor prognosis. In a study of untreated patients with del(17p) by FISH, a subset with mutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene (IGHV) and Rai stage 0 disease had significantly longer time to initiation of treatment and significantly longer overall survival than those with unmutated IGHV and Rai stage I to IV disease [30•]. Indeed, many of these patients were observed for more than 3 years with stable disease and did not require treatment. A lower proportion of 17p-deleted nuclei by FISH (<25%) was also independently associated with longer median overall survival. Another study noted that a subset of patients with TP53 abnormalities and mutated IGHV may have long-term stable disease not requiring treatment [32]. In view of these findings, therapy for patients with del(17p) should be initiated according to criteria for active disease recently updated by the International Workshop for CLL (IWCLL), as some early-stage patients may have a reasonable prognosis despite the presence of del(17p) [33••].

Results of Frontline Therapy in Patients with CLL With Del(17p)

The presence of del(17p) or TP53 mutations in patients with CLL has been associated with poor response to treatment, short response duration, and short survival following monotherapy with an alkylating agent or purine analogue [25, 34, 35]. Purine analogues such as fludarabine and 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine (2-CDA) induce leukemia cell death by a p53-dependent mechanism of action in CLL cells; in vitro experiments demonstrated drug resistance in CLL cells with p53 dysfunction [36, 37]. Dysfunction of the p53 pathway is associated with in vitro resistance to chlorambucil [38, 39]. The poor response of CLL cells exposed to an alkylating agent and fludarabine in vitro was confirmed in phase II and phase III clinical trials (Table 1). Chlorambucil monotherapy for patients with CLL with del(17p) results in poor responses and short progression-free survival (overall response rate [ORR], 20%–27%; progression-free survival [PFS], 2–3 months) [40, 41]. Fludarabine monotherapy also results in a low ORR (27%–60%) and short PFS (~6–9 months). Combination therapy with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (FC) demonstrated improvements in complete remission (CR), ORR, and PFS in untreated patients with CLL without del(17p), but FC was not associated with significant improvement in CR or PFS for patients with del (17p) [42–44]. The small number of patients with del(17p) in these studies may have limited the ability to detect differences in outcomes in this subgroup.

Table 1.

Results of frontline regimen in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia with del(17p)

| Study | Regimen | Patients, n | CR, % | ORR, % | Median PFS, mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hallek et al., 2010 [2••] | FCR | 21 | 5 | 71 | 3y PFS, 17.9% |

| Keating et al. (pc) | FCR | 20 | 20 | 70 | 21 |

| Bosch et al., 2009 [48] | FCMR+Ra | 4 | 25 | n/a | n/a |

| Faderl et al., 2010 [49] | FCMR | 2 | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Kay et al., 2007 [50] | PCR | 3 | 0 | 0 | <6 |

| Wierda et al., 2009 [51] | O-FC | 8 | 13 | 63 | n/a |

| Fischer et al., 2009 [47] | BR | 7 | 0 | 43 | n/a |

| Hallek et al., 2010 [2••] | FC | 22 | 0 | 46 | 3y PFS, 0% |

| Robak et al., 2010 [86] | FC | 19 | 16 | n/a | 9.2 |

| Stilgenbauer et al., 2008 [44] | FC | 16 | 6.7 | 60 | 6.1b |

| Flinn et al., 2007 [43] | FC | 10 | n/a | 69 | 11.9 |

| Catovsky et al., 2007c [42] | FC | 8 | 0 | 25 | 3.7 |

| Robak et al., 2010 [86] | CC | 15 | 40 | n/a | 25.3 |

| Bosch et al., 2008 [87] | FCM | 5 | 0 | n/a | n/a |

| Byrd et al., 2006 [45] | FR | 3 | 0 | 100 | 18 |

| Kay et al., 2010 [46] | PR | 1 | 0 | n/a | 18.9 |

| Stilgenbauer et al., 2008 [44] | F | 10 | 0 | 60 | 5.6b |

| Catovsky et al., 2007c [42] | F | 8 | 0 | 38 | 3.1 |

| Flinn et al., 2007 [43] | F | 9 | n/a | 27 | 8.9 |

| Eichhorst et al., 2009 [88] | F | 5 | 0 | 20 | n/a |

| Hillmen et al., 2007d [40] | Alemtuzumab | 11 | n/a | 64 | 10.7 |

| Pettitt et al., 2009 [72] | CamPred | 17 | 37e | n/a | n/a |

| Stilgenbauer et al., 2010 [73] | CamDex | 22 | 23 | 100 | n/a |

| Parikh et al., 2009 [58] | CFAR | 14 | 57 | 78 | 15 |

| Hillmen et al., 2007d [40] | Chlorambucil | 10 | n/a | 20 | 2.2 |

| Catovsky et al., 2007c [42] | Chlorambucil | 15 | 0 | 27 | 3.8 |

| Eichhorst et al., 2009 [88] | Chlorambucil | 5 | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Castro et al., 2009 [70] | R-Pred | 1 | 0 | 1 | n/a |

| Badoux et al., 2010 [76] | Lenalidomide | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

BR bendamustine and rituximab, C cyclophosphamide, CamDex alemtuzumab and methylprednisolone, CamPred alemtuzumab and methylprednisolone, CC cladribine (2-Cda) and cyclophosphamide, CFAR FCR with alemtuzumab, CR complete remission, F fludarabine, FCM FC and mitoxantrone, FCR FC and rituximab,FCMR FCR and mitoxantrone, n/a not available, O-FC ofatumumab and FC, ORR overall response rate, pc personal communication, PCR pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab, PR pentostatin and rituximab, PFS median progression-free survival, R-Pred rituximab and methylprednisolone

Rituximab maintenance (375 mg/m2 q 3 mo)

Event-free survival

CR and PFS provided by personal communication, R. Wade

Del(17p) identified by metaphase karyotype

CR and CRi (CR with incomplete hematologic recovery)

Response to treatment and PFS for CLL and indolent B-cell lymphomas have improved with the availability and incorporation of rituximab in chemoimmunotherapy regimens. Combination chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) is now the standard of care in younger patients with CLL, based on the results of the German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Study Group (GCLLSG) CLL-8 trial [2••]. In this trial, patients with del(17p) who received FCR had a trend to improved ORR (FCR vs FC: ORR 71% vs 46%, P=0.08) and 3-year PFS (17.9% vs 0%, P=0.052) when compared with patients who received FC, but patient numbers were limited (FCR, n=21; FC, n=16), which may explain why outcomes did not differ by statistically significant amounts. We performed a retrospective analysis of patients at MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) with del(17p) by FISH who received FCR as frontline therapy for CLL (n=20). The responses and survival duration were significantly shorter for patients with CLL with del(17p) than for patients with other or no cytogenetic abnormalities by FISH. Nevertheless, the ORR for patients with del(17p) was 70% and the estimated median PFS was 21 months, not dissimilar to the results of the GCLLSG (personal communication, M. Keating). Chemoimmunotherapy responses for a subset of these patients from MDACC, in addition to patients from Mayo Clinic, Rochester, were previously published by Tam et al. [30•].

Other chemoimmunotherapy combinations have been explored in CLL, although experience with del(17p) is limited in these studies. There have been few reported cases of patients with del(17p) treated with combinations of a purine analogue and rituximab (3 patients treated with fludarabine and rituximab [FR] [45], and 1 patient treated with pentostatin and rituximab [PR] [46]. In a phase II frontline study of bendamustine and rituximab, 3 (43%) of 7 patients with del(17p) achieved partial remission (PR), and there were no complete responders [47]. Outcomes of a handful of patients with del(17p) have been reported with FCR-like chemoimmunotherapy regimens including FCR with mitoxantrone (FCMR); pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (PCR); and FC with ofatumumab (FCO), with little available long-term follow-up data (Table 1) [47–51]. To make more valid comparisons and draw meaningful conclusions about the treatment of patients with del(17p), we need greater numbers of patients treated uniformly.

Alemtuzumab, a CD52 monoclonal antibody (mAb), has been extensively studied in both B-cell and T-cell malignancies. In CLL, alemtuzumab monotherapy was first reported in the salvage setting, where patients with del(17p) experienced similar responses to patients without del(17p) [52–54]. Following a number of trials demonstrating the activity of alemtuzumab monotherapy in untreated patients with CLL [55, 56], a randomized phase III trial (CAM307) comparing alemtuzumab to chlorambucil for previously untreated patients with CLL demonstrated encouraging responses with alemtuzumab (n=11) versus chlorambucil (n=10) in the subgroup with del(17p): the ORR was 64% versus 20% (P= 0.08) [40]. The median PFS was disappointingly short (14.5 months in all patients after alemtuzumab), with no significant improvement in PFS for patients with del(17p) who received alemtuzumab compared with chlorambucil (PFS, 11 months vs 2.2 months; P=0.41), although the patient numbers are again limited. After 24 months of follow-up, the estimated median overall survival (OS) was not reached in either group. Although patients with bulky adenopathy (≥5 cm) experienced poor responses to alemtuzumab monotherapy in the relapsed and refractory setting, in CAM307 these patients experienced a significant improvement in ORR (76% vs 44%) compared with the chlorambucil group, although there was no significant improvement in PFS [40]. Although alemtuzumab led to more neutropenia and cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation than chlorambucil (mostly asymptomatic), severe infections did not increase significantly. The results of this study led to a recommendation that alemtuzumab monotherapy may be used as frontline therapy in patients with del(17p) and nonbulky disease.

Because of the activity of alemtuzumab monotherapy as initial therapy for CLL and the potential for synergy with chemotherapy, fludarabine-based combinations with alemtuzumab have been developed. The GIMEMA LLC0405 study investigated the effectiveness of the combination of fludarabine and alemtuzumab (FluCam) for high-risk untreated patients with CLL [57]. In this study, “high-risk” was highly heterogeneous; high-risk patients were defined as those with 17p deletion or with 11q deletion and an additional risk factor such as unmutated IGHV genes, high ZAP70, high CD38, or a number of unfavorable prognostic factors. At last update, responses for 45 high-risk patients were encouraging (CR, 30%; ORR, 71%) although del(17p) was identified in 3 of 7 patients refractory to therapy. No further information was available on the patients with del (17p), and final results of this study are pending.

Cyclophosphamide was combined with fludarabine and alemtuzumab (FCCam) to improve the efficacy of the FluCam regimen. The CLL2007FMP study from the French Study Group comparing FCR versus FCCam in high-risk patients without del(17p) was terminated prematurely because of increased fatal infections in the alemtuzumab arm. The Dutch Study Group is currently conducting the HOVON-68 study comparing FCCam versus FC as frontline therapy in high-risk CLL; results are pending. Alemtuzumab has been combined with FCR in a frontline trial for high-risk patients (defined by β2-microglobulin more than twice the upper limit of normal) younger than 70 years [58]. This study demonstrated good response rates in 14 patients with del(17p) (CR, 57%; ORR, 78%), but in a historical comparison, the PFS and OS appeared no better than rates for FCR-based regimens without alemtuzumab. Although alemtuzumab-containing chemoimmunotherapy regimens appear promising for patients with del(17p), no convincing results currently support their use as standard frontline therapy.

Consolidation Strategies

Alemtuzumab

Alemtuzumab consolidation for eradication of residual disease following chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy is feasible and was demonstrated in a number of studies [59–62]. In untreated patients with CLL, studies demonstrated the ability of alemtuzumab to improve CR rates after fludarabine-based therapy (F or FR) [63–66]. These studies were not randomized, however, and improvement in response duration or survival cannot be assessed. In addition, these studies demonstrated unacceptably high infection rates, with grade 3 or 4 infectious toxicity in about 16% to 21% of patients. The GCLLSG CLL-4B trial demonstrated an improvement in PFS in previously untreated patients with CLL who were randomized to alemtuzumab consolidation versus observation (PFS not reached vs 20.6 months at a median follow-up of 48 months; P=0.0035), even though the study was terminated early owing to early infectious toxicity [67]. Data for patients with del(17p) are not available from these studies, so it is not possible to make recommendations about this approach in this patient population, especially in view of the significant infectious toxicity associated with alemtuzumab.

Rituximab

Rituximab consolidation to increase response duration has also been evaluated. One study explored the feasibility of rituximab consolidation and maintenance following fludarabine induction for patients with CLL [68]. In patients who had residual disease (MRD+CR or PR), this study showed improved response duration with rituximab consolidation compared with a nonrandomized observation group. There was minimal associated grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicity (n=4, 14%) or infectious toxicity (n=7, 25%, all herpetic infections). Although the authors noted that patients with higher-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, including trisomy 12, del(11q), and del(17p), had shorter response duration after consolidation, no data were available for patients with del(17p). In view of the lack of data about the role of consolidation following frontline treatment for patients with del(17p), this approach should be investigated further in clinical trials before recommendations can be made about this strategy.

Antibody Combination Therapies and Immunomodulatory Drugs

Combinations of rituximab and high-dose methylprednisolone have been explored in patients with CLL and del(17p) in order to take advantage of the p53-independent mechanism of action of the mAbs and following reports of responses with high-dose methylprednisolone in heavily pretreated patients with CLL with del(17p) [69]. One frontline study of 36 patients reported good results and tolerability, although only one patient had del(17p) at initiation of treatment [70]. In the relapsed setting, this combination demonstrated a reasonable ORR (56%) in patients with del(17p) (n=9), but no follow-up data are currently available [71].

Alemtuzumab has also been combined with methylprednisolone (CamPred) in the National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) CLL206 study of 41 patients with del (17p) [72]. Of the 16 evaluable patients with untreated CLL, 6 patients (37.5%) achieved CR or CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi). Of these 16 patients, 3 died with a short median follow-up (<2 years). Patients treated with this combination experienced a relatively high rate of infections, with 41% of untreated patients experiencing at least one grade 3 or 4 infectious event and 41% of patients experiencing grade 3 or 4 CMV reactivation. Final results of this trial are awaited. The combined German and French CLL2O trial is investigating the combination of alemtuzumab and oral dexamethasone followed by alemtuzumab maintenance in patients with CLL who have del(17p) and are fludarabine-refractory (N=80), also including 31 patients with untreated CLL and del(17p). All evaluable patients (n=22) had an objective response, including 23% CR. Four patients have progressed after a median follow-up of 41 weeks, and median OS has not been reached. A grade 3 or 4 non-CMV infectious event was experienced by 32% of frontline patients [73]. Further update of these results is expected.

Rituximab and alemtuzumab have also been combined in treating patients with early-stage, high-risk CLL without National Cancer Institute–Working Group (NCI-WG) criteria for initiation of therapy [74]. High-risk patients were defined by the presence of del(17p), del(11q), or the combination of unmutated IGHV and high CD38 or ZAP70. Although 9 patients in this study had a del(17p), results were not available for this subgroup. The responses for the whole group of patients were good (ORR, 90%; CR, 37%), but the median response duration was short (14.4 months). Preliminary results of another phase II trial of alemtuzumab and rituximab in untreated patients with CLL also demonstrated good results (ORR, 90%; CR, 75%), although only one patient had del(17p) [75]. A low rate of infectious toxicity was reported for this combination, and this regimen warrants further study as frontline therapy.

Lenalidomide monotherapy was used with reasonable success to treat elderly patients with CLL, but the response rate for six patients with del(17p) was disappointing: there were no objective responses and PFS was short (6 months) [76].

Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation

Because of the short response duration of patients with CLL and del(17p) and their dismal outcomes after salvage therapy, the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) recognizes the presence of del (17p) in patients who have an indication for therapy as an indication for allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) [77]. According to registry data, transplant-related mortality rates were up to 44% for myeloablative alloSCT, whereas nonrelapse mortality rates were 15% to 25% for alloSCT with reduced-intensity conditioning [78]. Although this is generally considered too high a risk for frontline patients with CLL, who may have prolonged responses and survival after frontline FCR, this risk may be outweighed in patients with del(17p) by short response duration after standard frontline therapy (FCR) and the dismal prognosis after relapse [79]. A retrospective review of EBMT data for 44 patients with del(17p) CLL showed a 3-year PFS of 37%; patients with del(17p) who had received no more than three prior therapies had significantly higher 3-year PFS than those who had received more than three prior therapies (53% vs 19%, P=0.03) [80•]. The GCLLSG CLL-3X trial also demonstrated long-term survival for 13 patients with del(17p) after alloSCT, with 3-year event-free survival (EFS) of 45%. Compared with other cytogenetic groups, patients with del(17p) had equivalent outcomes after transplantation, but patients who were chemorefractory at the time of transplantation had significantly shorter EFS (HR, 2.77; 95% CI, 1.50–5.09) [81•]. Similarly, an internal review of 24 heavily pretreated patients who had CLL with del(17p) demonstrated an estimated 3-year PFS of 30% after transplantation at MDACC [79].

Although the results with alloSCT appear encouraging for patients with del(17p) who have had fewer prior treatments, patients with CLL in transplant studies are generally selected for age, performance status, and disease remission status, which may skew outcomes. In addition, a number of patients with del(17p) and a poorer prognosis who would otherwise be eligible for transplantation may not receive alloSCT because of early relapse or death. In view of the improved post-transplant outcomes for patients with fewer prior treatments and the current EBMT recommendations, studies should be conducted to examine survival outcomes following alloSCT for patients with del(17p), including appropriate control patients without available donors.

Flavopiridol and Other Cyclin D Kinase Inhibitors

Flavopiridol is a synthetic flavone that inhibits cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) and CDK2 by competitive inhibition with ATP and modulation of tyrosine phosphorylation of CDK1 and CDK2 [82]. In addition, flavopiridol downregulates the anti-apoptotic proteins Mcl-1 and XIAP-1. Mcl-1 is an important apoptotic protein in CLL cells and may contribute to CLL cells’ resistance to rituximab. An ORR of 57% (all PR) was reported in a phase II study of flavopiridol monotherapy in patients with CLL with del(17p) [83]. The main dose-limiting toxicity of this drug was severe tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), which required vigorous TLS prophylaxis. A combination study of flavopiridol with fludarabine and rituximab demonstrated complete response in two of three patients with CLL with del(17p), suggesting that this drug may have a role in combination chemoimmunotherapy [84].

Other Agents Under Investigation

A number of targeted therapies are currently under investigation in CLL (Table 2). Some of these agents cause CLL cell lysis in a p53-independent manner and should be assessed further in patients with del(17p). R-roscovitine (CYC202) is a cyclin D kinase inhibitor with in vitro activity in CLL cells with defective p53. Bruton tyrosine kinase (Btk), Lyn, and Syk are tyrosine kinases involved in signal transduction downstream of the B-cell receptor; they influence B-cell proliferation and survival. Small-molecule inhibitors of these protein kinases, as well as the phosphoinositide-3-kinase delta inhibitor, CAL-101, are currently in phase I and phase II clinical trials for CLL. A number of Bcl-2 inhibitors currently in clinical development for patients with CLL may prove useful in patients with del(17p). TRU-016, a CD37 small modular immunopharmaceutical, has activity in relapsed and refractory patients with CLL, including patients with del(17p) [85]. Active research in targeted therapy for CLL is an important area of development, which may lead to improvements in results of frontline combination therapy in the future. The safety and efficacy of these agents in combination remains to be demonstrated, however, and their activity against leukemia cells with del(17p) must be confirmed in larger numbers of patients.

Table 2.

Therapies under investigation with potential for response in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia with del(17p)

| Class | Agent | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclin D kinase (CDK) inhibitors | Flavopiridol | CDK1/2, Mcl-1 inhibitor |

| R-roscovitine | CDK inhibitor | |

| Monoclonal antibodies | Ofatumumab | Anti-CD20 |

| GA-101 | Anti-CD20 | |

| Small modular immunopharmaceuticals | TRU-016 | Anti-CD37 |

| Specific kinase inhibitors | PCI-32765 | Btk inhibitor |

| Fostamatinib | Syk inhibitor | |

| CAL-101 | PI3K-delta inhibitor | |

| Bafetinib | Lyn kinase inhibitor | |

| Bcl-2 inhibitors | Obatoclax | Bcl-2 inhibitor |

| Oblimersen | Anti-sense oligonucleotide |

Bcl B-cell lymphoma, Btk Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, CDK cyclin-dependent kinase, PI3K phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase, Syk spleen tyrosine kinase

Conclusions

There has been significant improvement in treatment outcomes for patients with CLL owing to chemoimmunotherapy regimens such as FCR, but patients with del(17p) continue to have a poor prognosis with chemoimmunotherapy because of inherent resistance to purine analogues and alkylating agents. Therapies that function via a p53-independent mechanism of cytotoxicity must be identified and developed for this population. Alemtuzumab was a promising agent for patients with del(17p), having good response rates. Unfortunately, frontline alemtuzumab monotherapy has been associated with relatively short remission duration, and chemoimmunotherapy combinations with alemtuzumab have been complicated by high rates of infectious toxicity; there has been no obvious advantage in PFS over standard FCR chemotherapy. It remains to be seen whether mAb combinations (with or without high-dose steroids) may lead to better remission duration and survival outcomes. An effective maintenance strategy may be needed for long-term disease control. One theoretical advantage of alemtuzumab over chemotherapy is that it avoids selecting for p53-deleted, chemotherapy-resistant CLL clones, but comparative OS data are not currently available to support this hypothesis. In view of the available evidence, FCR should still be considered for the frontline therapy of younger or fit elderly patients, including those with del(17p). Alemtuzumab monotherapy is a reasonable alternative approach, especially in more elderly patients and patients with nonbulky (<5 cm) lymph nodes.

The EBMT recommends alloSCT in patients with del (17p) who satisfy NCI-WG criteria for treatment in CLL. It is important to note that not all patients with del(17p) have similar outcomes. Response duration and survival after FCR may depend on other factors such as mutational status, performance status, and proportion of 17p-deleted cells identified by FISH. Data from the GCLLSG suggest that patients undergoing transplantation after no more than three prior treatments have a high probability of disease-free survival. These findings support the recommendation by the EBMT that alloSCT be given early consideration for patients with del(17p), especially those who are younger or fit (including those who achieve CR following frontline therapy). Because of the paucity of evidence for this recommendation, trials should be specifically designed to assess the validity of this approach.

Further research in this population of patients with CLL should focus on new agents with p53-independent mechanisms of action and on designing well-conducted trials to establish the most effective frontline strategy for this population.

Footnotes

Disclosure Conflicts of interest: X.C. Badoux: None. M.J. Keating: Consultant for Roche, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Genzyme. W.G. Wierda: Consultant, speaker, DSMB member for Genentech; speaker for Roche; speaker and consultant for Genzyme, Celgene, and Cephalon; speaker, research funding from GlaxoSmithKline.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.•• Tam CS and Keating MJ: Chemoimmunotherapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2010, 7:521–532. This is a thorough review of chemoimmunotherapy in CLL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.•• Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. : Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2010, 376:1164–1174. This publication demonstrates the survival advantage gained by adding rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in this important phase III study in untreated patients with CLL. In addition, the study confirms the inferior response and outcomes experienced by patients with 17p deletions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.• Tam CS, O’Brien S, Wierda W, et al. : Long-term results of the fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab regimen as initial therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2008, 112:975–980. This article reports long-term results of the initial study of frontline FCR in patients with CLL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isobe M, Emanuel BS, Givol D, et al. : Localization of gene for human p53 tumour antigen to band 17p13. Nature 1986, 320:84–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, et al. : p53 mutations in human cancers. Science 1991, 253:49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine AJ: p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell 1997, 88:323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Efeyan A and Serrano M: p53: guardian of the genome and policeman of the oncogenes. Cell cycle 2007, 6:1006–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seiler T, Dohner H and Stilgenbauer S: Risk stratification in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Semin Oncol 2006, 33:186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bates S, Phillips AC, Clark PA, et al. : p14ARF links the tumour suppressors RB and p53. Nature 1998, 395:124–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haines DS: The mdm2 proto-oncogene. Leuk Lymphoma 1997, 26:227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marine JC and Lozano G: Mdm2-mediated ubiquitylation: p53 and beyond. Cell death and differentiation 2010, 17:93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe T, Hotta T, Ichikawa A, et al. : The MDM2 oncogene overexpression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and low-grade lymphoma of B-cell origin. Blood 1994, 84:3158–3165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bixby D, Kujawski L, Wang S, et al. : The pre-clinical development of MDM2 inhibitors in chronic lymphocytic leukemia uncovers a central role for p53 status in sensitivity to MDM2 inhibitor-mediated apoptosis. Cell cycle 2008, 7:971–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris SL and Levine AJ: The p53 pathway: positive and negative feedback loops. Oncogene 2005, 24:2899–2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyashita T, Krajewski S, Krajewska M, et al. : Tumor suppressor p53 is a regulator of bcl-2 and bax gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene 1994, 9:1799–1805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas A, El Rouby S, Reed JC, et al. : Drug-induced apoptosis in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: relationship between p53 gene mutation and bcl-2/bax proteins in drug resistance. Oncogene 1996, 12:1055–1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston JB, Daeninck P, Verburg L, et al. : P53, MDM-2, BAX and BCL-2 and drug resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 1997, 26:435–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, et al. : Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2000, 343:1910–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han T, Ozer H, Sadamori N, et al. : Prognostic importance of cytogenetic abnormalities in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med 1984, 310:288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juliusson G and Gahrton G: Chromosome aberrations in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Pathogenetic and clinical implications. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1990, 45:143–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juliusson G, Oscier D, Juliusson G, et al. : Cytogenetic findings and survival in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Second IWCCLL compilation of data on 662 patients. Leukemia Lymphoma 1991, 5:21–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oscier DG, Stevens J, Hamblin TJ, et al. : Correlation of chromosome abnormalities with laboratory features and clinical course in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 1990, 76:352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pittman S and Catovsky D: Prognostic significance of chromosome abnormalities in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 1984, 58:649–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geisler CH, Philip P, Christensen BE, et al. : In B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia chromosome 17 abnormalities and not trisomy 12 are the single most important cytogenetic abnormalities for the prognosis: a cytogenetic and immunophenotypic study of 480 unselected newly diagnosed patients. Leuk Res 1997, 21:1011–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fenaux P, Preudhomme C, Lai JL, et al. : Mutations of the p53 gene in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report on 39 cases with cytogenetic analysis. Leukemia 1992, 6:246–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi D, Cerri M, Deambrogi C, et al. The prognostic value of TP53 mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia is independent of Del17p13: implications for overall survival and chemorefractoriness. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:995–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zenz T, Eichhorst B, Busch R, et al. TP53 mutation and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4473–4479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.• Butler T and Gribben JG: Biologic and clinical significance of molecular profiling in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood reviews 2010, 24:135–141. This is an up-to-date review of the utility of molecular profiling in CLL, including the roles of prognostic factors in developing risk-stratified therapy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dal-Bo M, Bertoni F, Forconi F, et al. : Intrinsic and extrinsic factors influencing the clinical course of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: prognostic markers with pathogenetic relevance. J Translational Med 2009, 7:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.• Tam CS, Shanafelt TD, Wierda WG, et al. : De novo deletion 17p13.1 chronic lymphocytic leukemia shows significant clinical heterogeneity: the M. D. Anderson and Mayo Clinic experience. Blood 2009, 114:957–964. This study demonstrates that patients with 17p deletion identified at diagnosis may have heterogenous prognosis, which may be dissected according to other clinical predictors, including IGHV mutational status, Rai stage, and percentage of cells with 17p deletions by FISH. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zenz T, Krober A, Scherer K, et al. : Monoallelic TP53 inactivation is associated with poor prognosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from a detailed genetic characterization with long-term follow-up. Blood 2008, 112:3322–3329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Best OG, Gardiner AC, Davis ZA, et al. : A subset of Binet stage A CLL patients with TP53 abnormalities and mutated IGHV genes have stable disease. Leukemia 2009, 23:212–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.•• Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. : Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood 2008, 111:5446–5456. These updated guidelines on the management of CLL include indications for initial therapy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dohner H, Fischer K, Bentz M, et al. : p53 gene deletion predicts for poor survival and non-response to therapy with purine analogs in chronic B-cell leukemias. Blood 1995, 85:1580–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.el Rouby S, Thomas A, Costin D, et al. : p53 gene mutation in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia is associated with drug resistance and is independent of MDR1/MDR3 gene expression. Blood 1993, 82:3452–3459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pettitt AR, Clarke AR, Cawley JC, et al. : Purine analogues kill resting lymphocytes by p53-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Br J Haematol 1999, 105:986–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pettitt AR, Sherrington PD and Cawley JC: The effect of p53 dysfunction on purine analogue cytotoxicity in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 1999, 106:1049–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silber R, Degar B, Costin D, et al. : Chemosensitivity of lymphocytes from patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia to chlorambucil, fludarabine, and camptothecin analogs. Blood 1994, 84:3440–3446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Begleiter A, Mowat M, Israels LG, et al. : Chlorambucil in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: mechanism of action. Leuk Lymphoma 1996, 23:187–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hillmen P, Skotnicki AB, Robak T, et al. : Alemtuzumab compared with chlorambucil as first-line therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2007, 25:5616–5623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oscier DG, Wade R, Orchard J, et al. : Prognostic Factors in the UK LRF CLL4 Trial [abstract]. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2006, 108:299. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Catovsky D, Richards S, Matutes E, et al. : Assessment of fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (the LRF CLL4 Trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007, 370:230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flinn IW, Neuberg DS, Grever MR, et al. : Phase III trial of fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide compared with fludarabine for patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: US Intergroup Trial E2997. J Clin Oncol 2007, 25:793–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stilgenbauer S, Eichhorst BF, Busch R, et al. : Biologic and Clinical Markers for Outcome after Fludarabine (F) or F Plus Cyclophosphamide (FC)—Comprehensive Analysis of the CLL4 Trial of the GCLLSG. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts 2008, 112:2089. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Byrd JC, Gribben JG, Peterson BL, et al. : Select high-risk genetic features predict earlier progression following chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine and rituximab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: justification for risk-adapted therapy. J Clin Oncol 2006, 24:437–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kay NE, Wu W, Kabat B, et al. : Pentostatin and rituximab therapy for previously untreated patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer 2010, 116:2180–2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fischer K, Cramer P, Stilgenbauer S, et al. : Bendamustine combined with rituximab (BR) in first-line therapy of advanced CLL: a multicenter phase II trial of the German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG) [abstract]. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts 2009, 114:205. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bosch F, Abrisqueta P, Villamor N, et al. : Rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone: a new, highly active chemoimmunotherapy regimen for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27:4578–4584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faderl S, Wierda W, O’Brien S, et al. : Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone plus rituximab (FCM-R) in frontline CLL <70 Years. Leuk Res 2010, 34:284–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kay NE, Geyer SM, Call TG, et al. : Combination chemoimmunotherapy with pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab shows significant clinical activity with low accompanying toxicity in previously untreated B chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2007, 109:405–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wierda WG, Kipps TJ, Durig J, et al. : Ofatumumab combined with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (O-FC) shows high activity in patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): results from a randomized, multicenter, international, two-dose, parallel group, phase II trial [abstract]. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts 2009, 114:207. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keating MJ, Flinn I, Jain V, et al. : Therapeutic role of alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) in patients who have failed fludarabine: results of a large international study. Blood 2002, 99:3554–3561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lozanski G, Heerema NA, Flinn IW, et al. : Alemtuzumab is an effective therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia with p53 mutations and deletions. Blood 2004, 103:3278–3281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Osuji NC, Del Giudice I, Matutes E, et al. : The efficacy of alemtuzumab for refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia in relation to cytogenetic abnormalities of p53. Haematologica 2005, 90:1435–1436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lundin J, Kimby E, Bjorkholm M, et al. : Phase II trial of subcutaneous anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) as first-line treatment for patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL). Blood 2002, 100:768–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Osterborg A, Fassas AS, Anagnostopoulos A, et al. : Humanized CD52 monoclonal antibody Campath-1H as first-line treatment in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 1996, 93:151–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mauro FR, Cortelezzi A, Molica S, et al. : Efficacy and Safety of a First-Line Combined Therapeutic Approach for Young CLL Patients Stratified According to the Biological Prognostic Features: First Analysis of the GIMEMA Multicenter LLC0405 Study. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts 2008, 112:3167. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parikh SA, Keating M, O’Brien S, et al. : Frontline Combined Chemoimmunotherapy with Fludarabine, Cyclophosphamide, Alemtuzumab and Rituximab (CFAR) in High-Risk Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts 2009, 114:208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dyer MJ, Kelsey SM, Mackay HJ, et al. : In vivo ‘purging’ of residual disease in CLL with Campath-1H. Br J Haematol 1997, 97:669–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Brien SM, Kantarjian HM, Thomas DA, et al. : Alemtuzumab as treatment for residual disease after chemotherapy in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer 2003, 98:2657–2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thieblemont C, Bouafia F, Hornez E, et al. : Maintenance therapy with a monthly injection of alemtuzumab prolongs response duration in patients with refractory B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (B-CLL/SLL). Leuk Lymphoma 2004, 45:711–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wierda WG, Kipps TJ, Keating MJ, et al. : Self-administered, subcutaneous alemtuzumab to treat residual disease in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer 2010, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Byrd JC, Peterson BL, Rai KR, et al. : Fludarabine followed by alemtuzumab consolidation for previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: final report of Cancer and Leukemia Group B study 19901. Leuk Lymphoma 2009, 50:1589–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hainsworth JD, Vazquez ER, Spigel DR, et al. : Combination therapy with fludarabine and rituximab followed by alemtuzumab in the first-line treatment of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma: a phase 2 trial of the Minnie Pearl Cancer Research Network. Cancer 2008, 112:1288–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin TS, Donohue KA, Byrd JC, et al. Consolidation therapy with subcutaneous alemtuzumab after fludarabine and rituximab induction therapy for previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: final analysis of CALGB 10101. J Clin Oncol 2010;28 (29):4500–4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Montillo M, Tedeschi A, Miqueleiz S, et al. : Alemtuzumab as consolidation after a response to fludarabine is effective in purging residual disease in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2006, 24:2337–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schweighofer CD, Ritgen M, Eichhorst BF, et al. : Consolidation with alemtuzumab improves progression-free survival in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) in first remission: long-term follow-up of a randomized phase III trial of the German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG). Br J Haematol 2009, 144:95–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Del Poeta G, Del Principe MI, Buccisano F, et al. Consolidation and maintenance immunotherapy with rituximab improve clinical outcome in patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2008;112:119–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thornton PD, Matutes E, Bosanquet AG, et al. : High dose methylprednisolone can induce remissions in CLL patients with p53 abnormalities. Ann Hematol 2003, 82:759–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Castro JE, James DF, Sandoval-Sus JD, et al. : Rituximab in combination with high-dose methylprednisolone for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia 2009, 23:1779–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bowen DA, Call TG, Jenkins GD, et al. : Methylprednisolone-rituximab is an effective salvage therapy for patients with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia including those with unfavorable cytogenetic features. Leuk Lymphoma 2007, 48:2412–2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pettitt R, Matutes E, Dearden C, et al. : Results of the phase II NCRI CLL206 trial of alemtuzumab in combination with high-dose methylprednisolone for high-risk (17p-) CLL. Haematologica 2009, 94[suppl.2]:abs. 0351. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stilgenbauer S, Cymbalista F, Leblond V, et al. Subcutaneous Alemtuzumab Combined with Oral Dexamethasone, Followed by Alemtuzumab Maintenance or Allo-SCT In CLL with 17p- or Refractory to Fludarabine - Interim Analysis of the CLL2O Trial of the GCLLSG and FCGCLL/MW. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts 2010, 116(21):920. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zent CS, Call TG, Shanafelt TD, et al. : Early treatment of high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia with alemtuzumab and rituximab. Cancer 2008, 113:2110–2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Frankfurt O, Hamilton E, Duffey S, et al. : Alemtuzumab and Rituximab Combination Therapy for Patients with Untreated CLL— a Phase II Trial. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts 2008, 112:2098. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Badoux X, Wierda WG, O’Brien SM, et al. : A phase II study of lenalidomide as initial treatment of elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2010, 28:abstr 6508. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dreger P, Corradini P, Kimby E, et al. : Indications for allogeneic stem cell transplantation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the EBMT transplant consensus. Leukemia 2007, 21:12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dreger P: Allotransplantation for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hematology 2009, 2009:602–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Badoux XC, Keating M, O’Brien S, et al. : Patients with Relapsed CLL and 17p Deletion by FISH Have Very Poor Survival Outcomes. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts 2009, 114:1248. [Google Scholar]

- 80.• Schetelig J, van Biezen A, Brand R, et al. : Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for chronic lymphocytic leukemia with 17p deletion: a retrospective European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation analysis. J Clin Oncol 2008, 26:5094–5100. The retrospective analysis of the EBMT registry data demonstrates the disease-free survival outcomes of patients with CLL after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. The survival of patients with 17p deletions is equivalent to those without deletions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.• Dreger P, Dohner H, Ritgen M, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation provides durable disease control in poor-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia: long-term clinical and MRD results of the German CLL Study Group CLL3X trial. Blood. 2010;116(14):2438–2447. These are results of a prospective trial of allogeneic stem cell transplantation in CLL, demonstrating the equivalent activity of transplantation (EFS) in patients with or without 17p deletion. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Christian BA, Grever MR, Byrd JC, et al. : Flavopiridol in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a concise review. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 2009, 9 Suppl 3:S179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lin TS, Ruppert AS, Johnson AJ, et al. : Phase II study of flavopiridol in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia demonstrating high response rates in genetically high-risk disease. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27:6012–6018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lin TS, Blum KA, Fischer DB, et al. : Flavopiridol, fludarabine, and rituximab in mantle cell lymphoma and indolent B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. J Clin Oncol 2010, 28:418–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Andritsos L, Furman R, Flinn IW, et al. : A phase I trial of TRU-016, an anti-CD37 small modular immunopharmaceutical (SMIP) in relapsed and refractory CLL [abstract]. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2009, 27:3017. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Robak T, Jamroziak K, Gora-Tybor J, et al. : Comparison of cladribine plus cyclophosphamide with fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide as first-line therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a phase III randomized study by the Polish Adult Leukemia Group (PALG-CLL3 Study). J Clin Oncol 2010, 28:1863–1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bosch F, Ferrer A, Villamor N, et al. : Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone as initial therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: high response rate and disease eradication. Clin Cancer Res 2008, 14:155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Eichhorst BF, Busch R, Stilgenbauer S, et al. : First-line therapy with fludarabine compared with chlorambucil does not result in a major benefit for elderly patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2009, 114:3382–3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]