Abstract

Objective:

This is a randomized controlled trial (NCT03056157) of an enhanced adaptive disclosure (AD) psychotherapy compared to present-centered therapy (PCT; each 12 sessions) in 174 veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related to traumatic loss (TL) and moral injury (MI). AD employs different strategies for different trauma types. AD-Enhanced (AD-E) uses letter writing (e.g., to the deceased), loving-kindness meditation, and bolstered homework to facilitate improved functioning to repair TL and MI-related trauma.

Method:

The primary outcomes were the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), evaluated at baseline, throughout treatment, and at 3- and 6-month follow-ups (Brief Inventory of Psychosocial Functioning was also administered), the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-5), the Dimensions of Anger Reactions, the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale, and the Quick Drinking Screen.

Results:

There were statistically significant between-group differences on two outcomes: The intent-to-treat (ITT) mixed-model analysis of SDS scores indicated greater improvement from baseline to posttreatment in the AD-E group (d = 2.97) compared to the PCT group, d = 1.86; −2.36, 95% CI [−3.92, −0.77], t(1,510) = −2.92, p < .001, d = 0.15. Twenty-one percent more AD-E cases made clinically significant changes on the SDS than PCT cases. From baseline to posttreatment, AD-E was also more efficacious on the CAPS-5 (d = 0.39). These differential effects did not persist at follow-up intervals.

Conclusion:

This was the first psychotherapy of veterans with TL/MI-related PTSD to show superiority relative to PCT with respect to functioning and PTSD, although the differential effect sizes were small to medium and not maintained at follow-up.

Keywords: randomized controlled trial, adaptive disclosure–enhanced, posttraumatic stress disorder, functional outcomes, war veterans

Adaptive disclosure (AD) is a manualized experiential psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), specifically designed to consider combatant roles within the military culture among service members and war veterans (B. T. Litz et al., 2017). The foundational assumptions of AD are: (a) fear- and victimization-related traumas are phenomenologically and etiologically distinct from traumatic loss (TL; Prigerson et al., 2009) and moral injury (MI), the latter entailing the lasting aftermath of doing things or failing to do things, or being the victim of, or bearing witness to others’ actions that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations (B. T. Litz et al., 2009); (b) fear-based warzone experiences are for the most part expected and trained-for occupational hazards, are more readily assimilated, and have less impact on self- and other-schemas (Graham et al., 2016; Kelley et al., 2009); and (c) TL and MI can result in responsibility-taking (and assigning) that stems from the bonds of us-group members (e.g., the unit) and violations of a moral code of conduct (which sustains sacrifice and hardship; Gray et al., 2017). With respect to loss, survivor’s guilt is understandable given the sacred expectation to protect fellow service members from harm; a warzone loss is arguably akin to the loss of a child to violence (Neria & Litz, 2004). TL/MI, which entails violations of us-group rules by the self or others, results in intense moral emotions (guilt/shame, anger, disgust), threats to personal and shared identity (belongingness) and social bonds, and losses of faith in personal or collective humanity (B. T. Litz et al., 2022). These unique outcomes arguably stem from losses of valued activity or no longer being valued by others in a kinship group, which are otherwise rewarding, positively inform identity and sense of purpose, and promote safety.

Existing evidence-based cognitive behavioral treatments (CBT) for PTSD (e.g., Ehlers et al., 2005; Foa et al., 2007; Resick et al., 2002; Sloan et al., 2018) employ cognitive restructuring to challenge the degree of responsibility-taking for TL/MI and normalize many transgressions based on contextual factors (e.g., due to the “fog of war”). Given that many veterans with PTSD fail to make clinically significant gains after treatment with CBT (Steenkamp et al., 2015), the development of alternative strategies is important to augment standard care, provide more options to patients, and open pathways to personalized care. AD employs distinct change agents to foster experiential learning to challenge views of personal or collective humanity and beliefs about the goodness and badness of the self or others and belonging/worthiness (see table in the Supplemental Materials). AD is a “yes–and” approach to the moral emotions and sequelae of perceived failures to ensure the safety of intimates that are lost to violence or grave moral harms by the self or others. The “yes” aspect acknowledges the lasting existential reality and phenomenology of responsibility-taking and assigning, and it provides enough time for the patient to unburden and share what is true, as well as to experience compassion, nonjudgmental understanding, and empathy. This is followed by a focus on what can be done to heal and repair the experience to rebalance beliefs about personal (or humanity’s) goodness relative to badness, which entails a flexible plan for exposure to corrective experiences in the patient’s context. This is in contrast with arguably “yes–but” approaches, which use Socratic questioning, moral relativism, and contextualizing to address TL/MI (e.g., Smith et al., 2013; Wachen et al., 2021).

Another feature that distinguishes AD from existing CBT approaches entails emotion-focused Gestalt therapy techniques (Paivio & Greenberg, 1995) to help service members and veterans process their trauma and consider pathways to healing and repair. For TL, the patient is asked to have evocative real-time dialogues (in imagination) with the lost service member. The patient is asked to share what happened and how the death has impacted them. In subsequent sessions, the patient voices in real-time the response of the lost person to the patient’s guilt, self-handicapping, and so forth. They also voice what the lost person would like the patient to be doing differently in service of healing the loss and how they would want the patient’s life path to unfold. If necessary, the therapist helps shape the dialogue, emphasizing that the mandate to live a good and connected life is the best way to honor the lost person and the importance of carrying on in a manner that commemorates the fallen. For life-threat traumas, in-session experiential exposures, followed by extensive in-vivo repair plans, are assumed to be sufficient change agents.

For MI, patients engage in an imaginal dialogue with a compassionate and forgiving moral authority (e.g., a trusted family member) about their own or others’ transgressions. Patients are also asked to share what the moral authority’s reaction is to what they just heard. In subsequent sessions, the experiential dialogue moves to voicing in real time what the compassionate person would say about how the patient should proceed in their life. For personal transgressions, a common theme from the compassionate moral authority is the expression of alarm and disappointment, yet it also includes recommendations to make amends and repair damage done, underscoring that the patient has done good, has been good, and should do good things (e.g., be compassionate, volunteer, take care of others in need) to restore goodness. For traumas that entail grave violations of trust, a common theme entails expressions of anger, resentment, aggrievement, and solidarity, but also a wish for the patient to move on by allowing goodness to occur around him or her. These experiential dialogues are akin to secular confessions, aiming to challenge guilt, shame, retribution, focus on grievance, and condemnation of self and others.

A six-session AD protocol was first evaluated with an open trial with 44 active-duty marines and sailors (Gray et al., 2012). Pre- to posttreatment effect sizes were large for PTSD (d = 0.79) and depression (d = 0.71), 75% of participants completed treatment, the therapy was well-tolerated, and satisfaction was high. Next, in a noninferiority trial comparing eight 90-min sessions of AD and 12 60-min sessions of cognitive processing therapy (CPT; Resick et al., 2016), also with active-duty marines and sailors, AD was found to be no less effective than CPT with respect to PTSD, depression, and functional change (B. T. Litz et al., 2021).

In consultation with study therapists and clinical experts, we accommodated lessons learned about AD from the previous trials and modified AD in several respects. First, because AD is distinguished from existing therapies by its focus on TL/MI and nearly all cases reported TL/MI as their worst and most currently distressing trauma (when fear-based events were focal, the lasting impact endorsed by service members pertained to shame about losing functional capacities and letting unit members down), the enhanced version of AD (AD-E) was designed to chiefly address TL/MI. Second, to reduce the burden on therapists to shape and guide varied in-session experiential processes, we incorporated letter-writing (e.g., to a lost person, to people who were harmed) as a change agent. Third, we added loving-kindness (compassion) meditation and mindfulness training because these are evidence-based strategies that help veterans accept their own and others’ humanity, promote approach behaviors toward others, and increase veterans’ motivation to progress toward meaningful social and work goals (compassion may also increase openness to the possibility of self- or other forgiveness; Au et al., 2017; B. Litz & Carney, 2018). Fourth, we shifted to a personalized recovery/rehabilitation approach (vs. the tacit disease/“cure” model). Consequently, we bolstered the behavioral contracting (i.e., homework) process to prioritize helping patients recover functioning in occupational, relationship, and family roles (Benfer & Litz, 2023). The therapy was also personalized in that various change agents were emphasized based on preference and likelihood of success experience, and all were framed to be in service of functional recovery aims.

The purpose of this study was to compare AD-E to present-centered therapy (PCT; Belsher et al., 2019), a supportive non-trauma-focused psychotherapy that helps patients deal with daily functional challenges with homework using a problem-solving framework. The primary outcomes were functioning, PTSD symptom severity, externalizing (anger, aggression), and harmful behavior (alcohol consumption). Secondary outcomes, such as self-report measures of PTSD, depression, shame, and compassion, will be reported in subsequent publications. We predicted that AD-E would lead to greater changes in all outcomes than PCT.

Method

Overview

This was a multisite randomized controlled trial comprising investigators from Veterans Affairs (VA) sites in Minneapolis; San Diego; San Francisco; Waco, Texas; and Boston. Boston exclusively served as the coordinating center for the study (a data safety monitoring board also oversaw the study in Boston), randomized cases, and conducted blind independent evaluations of PTSD. The other sites recruited and treated cases. Potential participants were recruited from providers who were informed that we were seeking veterans deployed to post-9–11 operations who had TL/MI-related trauma.

Transparency and Openness

We reported how we determined our sample size, all manipulations, and all measures in the study, and we followed Journal Article Reporting Standards. There were no data exclusions. Requests for deidentified data, analysis code, and research materials should be made to the first author. Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 26, SAS 9.4, and R Version 4.0.2 using RStudio. This study was preregistered at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show NCT03056157, and the protocol was described in Yeterian et al. (2017). Manuals are available upon request.

Participants

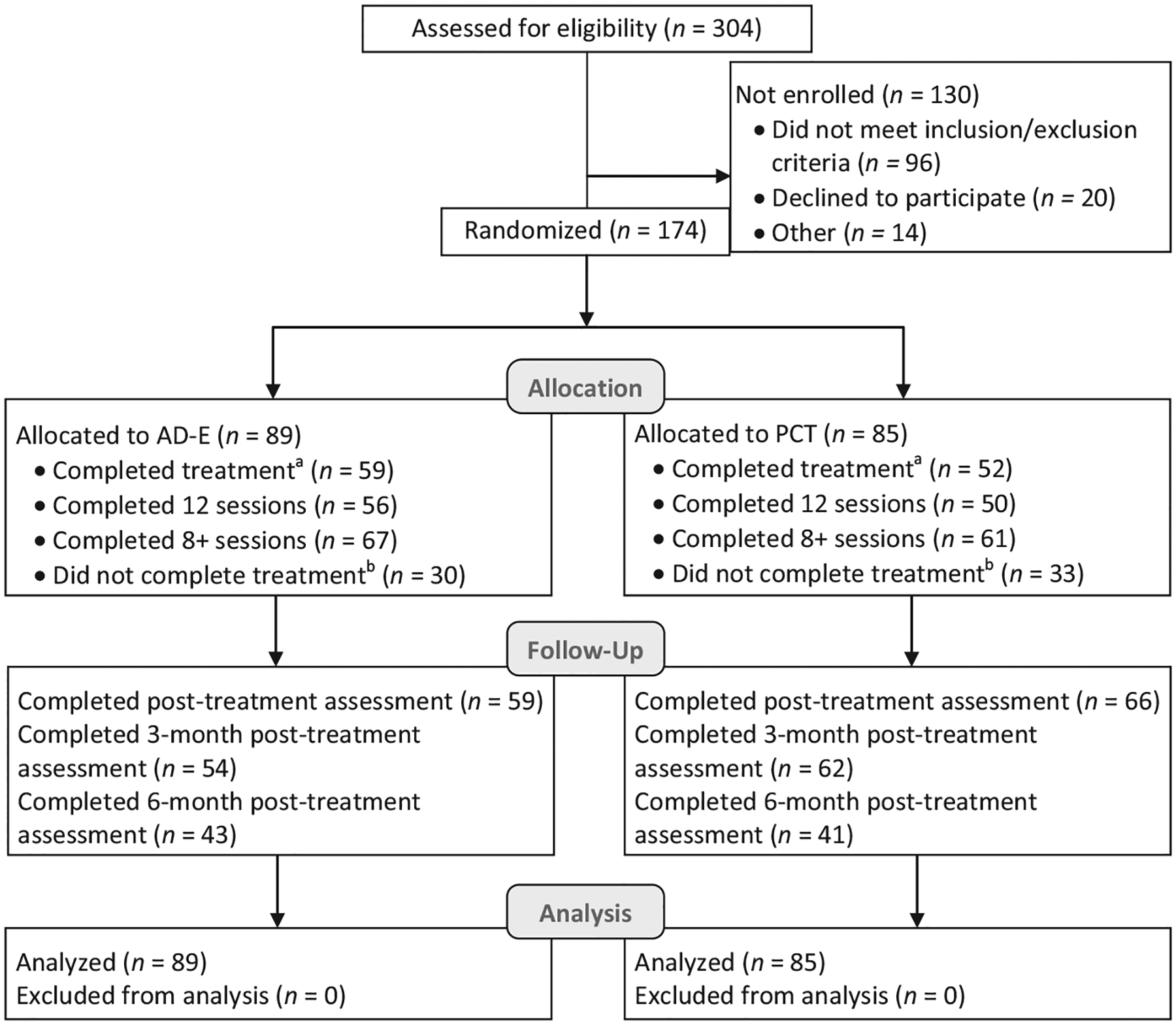

One hundred seventy-four veterans who served in post-9–11 warzones were randomized (see Figure 1). Number randomized by location: Minneapolis: 68; San Francisco: 44; San Diego: 54; and Central Texas (a site added late in the trial): 8. The mean age of participants was 39.02 years (SD = 8.62). Seventy-seven percent were males, 59.2% were Caucasian, 22.4% were Hispanic/Latino, and 48.3% were married (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Flow Diagram

Note. AD-E = Adaptive Disclosure–Enhanced; PCT = present-centered therapy.

a A participant was considered to have completed treatment if they received 12 sessions within the allotted 16-week interval or were deemed an early completer by their study therapist. b A participant was considered to not have completed treatment if they did not receive 12 sessions within the allotted 16-week interval or they were not deemed an early completer by their study therapist.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Participant groups, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entire sample (n = 174) | AD-E (n = 89) | PCT (n = 85) | |

| Age, M (SD) | 39.02 (8.62) | 38.82 (8.61) | 39.24 (8.68) |

| Post high school education | 161 (92.5) | 83 (93.3) | 78 (91.8) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 135 (77.6) | 69 (77.5) | 66 (77.6) |

| Female | 37 (21.3) | 19 (21.3) | 18 (21.2) |

| Other | 2 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) |

| Race | |||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Asian | 9 (5.2) | 4 (4.5) | 5 (5.9) |

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 5 (2.9) | 3 (3.4) | 2 (2.4) |

| Black or African American | 19 (10.9) | 10 (11.2) | 9 (10.6) |

| White | 104 (59.8) | 54 (60.7) | 50 (58.8) |

| More than one race | 17 (9.7) | 5 (5.6) | 12 (14.1) |

| Other | 19 (10.9) | 12 (13.5) | 7 (8.2) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 40 (23.0) | 19 (21.3) | 21 (24.7) |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 123 (70.7) | 66 (74.2) | 58 (68.2) |

| Unknown | 11 (6.3) | 4 (3.4) | 6 (7.1) |

| Marital status | |||

| Never married | 40 (23.3) | 19 (21.3) | 21 (24.7) |

| Married or common law | 86 (49.4) | 48 (53.9) | 38 (44.7) |

| Currently separated or divorced | 46 (26.4) | 22 (24.7) | 24 (28.2) |

| Widowed | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.4) |

| Years in militarya, M (SD) | 10.99 (7.67) | 11.11 (7.64) | 10.87 (7.75) |

| Branch of service | |||

| Army | 80 (46.0) | 41 (46.1) | 39 (45.9) |

| Marine corps | 43 (24.7) | 22 (34.7) | 21 (24.7) |

| Airforce | 17 (9.8) | 9 (10.1) | 8 (9.4) |

| Navy | 34 (19.5) | 17 (19.1) | 17 (20.0) |

| Military ranka | |||

| Junior enlisted | 7 (4.0) | 4 (4.5) | 3 (3.5) |

| Noncommissioned officer | 153 (87.9) | 79 (88.8) | 74 (87.1) |

| Warrant officer | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Junior officer | 10 (5.7) | 4 (4.5) | 6 (7.1) |

| Senior officer | 2 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) |

Note. AD-E = Adaptive Disclosure–Enhanced; PCT = present-centered therapy.

Data regarding years in military and military rank were available for 173 participants.

Measurement Domains and Measure

Functioning

We administered the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS; K. H. Sheehan & Sheehan, 2008) at baseline, before every treatment session, posttreatment, and at a 3- and 6-month follow-up. The SDS is a self-report measure that assesses social, educational, and occupational functioning. Respondents indicated the degree to which PTSD symptoms disrupted work/school, social life, and family life/responsibilities on an 11-point scale ranging from not at all to extremely. The SDS is used to track disability and has demonstrated good treatment validity (K. H. Sheehan & Sheehan, 2008). When applicable, we prorated scores such that only social and family ratings were included for veterans who were not employed or attending school. There were no statistically significant differences in the frequency of entering N/A for the work/school item between arms at any time point (e.g., 25/89 participants in A-DE rated N/A at least once and 20/85 in PCT rated N/A at least once).

We also administered the Brief Inventory of Psychosocial Functioning (B-IPF; Kleiman et al., 2020) at baseline, posttreatment, and 3- and 6-month posttreatment. The B-IPF is a seven-item self-report scale that assesses functioning in relationships, with children or family, socializing, work, training and education, and activities of daily living. Respondents indicated the degree to which they had trouble in the last 30 days in each area on a 7-point scale ranging from not at all to very much. Scores were prorated if veterans were not involved in training or education. The B-IPF has good internal consistency and concurrent validity (Kleiman et al., 2020).

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

PTSD symptom severity was assessed with the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (CAPS-5; Weathers et al., 2018) at baseline, posttreatment, and 3- and 6-month posttreatment. The CAPS-5 is a structured clinical interview to assess PTSD severity in the past month with excellent psychometric properties and diagnostic efficiency (Weathers et al., 2018). The internal consistency reliability in this trial was .80. PTSD caseness was defined as ratings of >2 (moderate/threshold) for the requisite Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition criteria. The CAPS-5 was administered by telephone, which has been shown to be a reliable and valid method (Litwack et al., 2014).

Externalizing: Anger and Aggressive Behavior

We used the Dimensions of Anger Reactions (DAR; Forbes et al., 2014) to assess state anger at baseline, posttreatment, and both 3- and 6-month follow-ups. The DAR is a widely used self-report measure of state anger with good psychometric properties (Forbes et al., 2014). The measure consists of seven items rated on a scale from 0 (none or almost none of the time) to 8 (all or almost all of the time), with higher scores indicating higher state anger. The internal consistency reliability in this trial was .88.

We used the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus & Douglas, 2004; Straus et al., 1996) to assess self-reported engagement in physically and/or psychologically aggressive behavior (i.e., the physical assault subscale and the psychological aggression subscale, respectively). These two subscales of the CTS2 were administered at baseline, posttreatment, and both 3- and 6-month follow-ups. The subscales consist of 12 and eight items, respectively, rated on a scale from 0 (never) to 7 (more than 20 times), with higher scores indicating greater use of aggressive behaviors in the past month. The internal consistency of each subscale in this trial was .84 for both physical assault and psychological aggression.

Alcohol Use

We assessed alcohol consumption by calculating average drinks per week using Items 1 and 2 of the Quick Drinking Screen (QDS; Sobell et al., 2003) at baseline, posttreatment, and at both 3- and 6-month follow-ups. The QDS is a self-report measure that has very good psychometric properties (Sobell et al., 2003). The internal consistency of the QDS items in this trial was .88.

Procedure

Inclusionary criteria included: (a) age 18 or older, (b) deployed to post-9–11 operations, (c) meeting the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition diagnostic criteria for PTSD (diagnosed by the CAPS-5), and (d) willingness to complete 12 consecutive weekly sessions, lasting up to 90 min in duration, as well as four assessment sessions. Participants were excluded if they had: (a) bipolar or psychotic disorders, (b) current moderate to severe substance use disorder (other than caffeine or tobacco use disorders), (c) evidence of traumatic brain injury severe enough to influence the ability to understand and respond to study procedures, (d) suicidal or homicidal ideation severe enough to warrant immediate attention, and (e) current psychotherapy that involved systematic disclosure of troubling deployment-related memories. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (D. V. Sheehan et al., 1998) was used to assess 1–4. Participants could continue pharmacological treatment if stable on medication for at least 6 weeks.

Veterans were recruited through referrals from mental health clinics. Interested veterans were prescreened by phone or in person for basic eligibility requirements and, if eligible, scheduled for an appointment in which consenting procedures and a more in-depth eligibility/baseline assessment took place. The baseline assessment was completed jointly by local study staff, who conducted the consenting and basic eligibility procedures, and the Boston-based independent evaluator (IE), who conducted the full clinical evaluation by phone.

During the baseline visit, local study staff obtained written informed consent for study participation and recording of assessments and treatment sessions. This study was approved by the internal review board at VA Boston and by each participating site’s internal review boards. Participants then completed the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013). If veterans met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition diagnostic criteria for PTSD on the PCL-5, based on the requisite symptoms endorsed at a moderate severity or greater, and did not endorse exclusion criteria, they continued to the diagnostic assessment by telephone with the Boston IE. Once PTSD and the absence of exclusionary criteria were confirmed, the participant was randomized to one of the two therapy arms and scheduled for treatment.

We used a randomized permuted block scheme to assign patients to blocks by gender and minority status. Block size for gender and minority status was based on the distribution of these variables at each site. If an unexpected imbalance occurred between-treatment arms, we used constrained biased coin randomization to address it.

The IEs were blind to treatment condition and reminded participants to help maintain their blindness by not disclosing details about treatment procedures. Study staff also emphasized to veterans that all assessment materials are kept private, and baseline, posttreatment, and follow-up data would not be shared with study therapists.

Treatment Arms and Fidelity Monitoring

Over the course of the trial, 10 doctoral-level therapists across four sites were trained and supervised to conduct both therapies. We initially planned to have two half-time therapists at each site, one to provide AD-E and one to provide PCT to minimize the chances of treatment contamination. However, we used a single therapist at each site to stay within budget, obviate hiring problems, minimize therapist effects, and reduce the risk of unblinding.

Present-Centered Therapy (12 Sessions)

We used the PCT manual that was used in prior trials of service members and veterans (e.g., Foa et al., 2018). In PCT, discussion and processing of traumatic events are proscribed. Instead, PCT first entails a didactic about what PTSD is, how it can affect present-day functioning, and how addressing current problems that have arisen as a result of the trauma can help reduce PTSD symptoms. In each session, the PCT therapist provides the essential nonspecific elements of psychotherapy, namely supportive, caring, and empathic reflective listening. Each session is also devoted to a discussion of current-day stressors and issues in the patient’s life, with an emphasis on expanding the patient’s understanding of the connection between PTSD symptoms and current-day problems. Homework is assigned in each session to help patients develop adaptive responses to functional stressors using a simple problem-solving approach.

Adaptive Disclosure–Enhanced (12 Sessions)

The AD-E manual includes sections on the military culture and the warrior ethos, how and why TL and MI are uniquely harmful, pathways to healing and repairing these unique outcomes, and why threat-, loss-, and MI-related traumas require unique treatment plans, followed by detailed session-by-session instructions (Litz & Carney, 2018; Litz et al., 2017). The AD-E manual also includes guidelines for troubleshooting common barriers to treatment for each facet of treatment, scripts for mindfulness and compassion exercises, and handouts associated with all recommended exercises. The components that were added to AD to create AD-E were: (a) a compassion history assessment (in the first session) to inform treatment planning (e.g., identifying potential behaviors that could be reclaimed, identifying a compassionate moral authority) and a discussion of changes in compassion toward self and others as the result of treatment (last session); (b) loving-kindness meditation (LKM) and mindfulness training (see Au et al., 2017; Litz & Carney, 2018), which included a background on LKM, how and why to integrate it throughout sessions, patient handouts, recommendations for addressing barriers to implementing a mindfulness practice, and training scripts; (c) letter-writing forms, tasks, and instructions, specific to different trauma types. A serially ordered set of letters (event disclosure/confession, describing the lasting negative impact, and writing the feedback in the voice of a compassionate moral authority or lost person) were read aloud in therapy to promote experiential processing of these experiences and to reveal potential areas for corrective action and healing outside of treatment; and (d) a comprehensive Healing and Repair Plan, which is a shared-decision-making approach to behavioral contracting that identifies doable activities the patient is willing to engage in outside of therapy to promote functional change. The manual includes a master list to help providers and veterans generate daily repair activities, broken down by behavioral activation/self-care, in vivo exposure, and thematically corrective/repair activities. The change agents in AD-E are described in Supplemental Table S1.

Training and Supervision

Training involved a review of the respective manuals and supporting materials, intensive supervision of two trial cases, and weekly individual phone supervision. All sessions were audiotaped. Two random recordings of AD-E sessions from a random 20% of each therapist’s cases were rated to ensure fidelity by one of the coauthors of the AD book. Each AD-E session had a corresponding checklist of necessary elements and procedures that were rated as present or not. Eighty-five percent of a random 10% of sessions reviewed had 100% fidelity; 100% of sessions had either full compliance or all but one required component present. Therapists also monitored deviations from the protocol. Seven percent of sessions had problems arise that led to departure from the agenda (2.5% of sessions entailed intervention strategies not included in the manual, 4.7% of sessions entailed engaging in more than 15 min of off-task discussion, and 89% of sessions had a homework compliance score of 1 [completed] or 2 [partially completed]).

For PCT, first, therapists read the PCT manual and had Q&A sessions with the supervisor, which included group discussions. Then, therapists had group supervision weekly via video conference with a psychologist with extensive expertise in PCT. Group supervision was chosen so that study therapists could share and get support for the most difficult aspect of PCT, namely not veering off into proscribed processes (such as not talking about the trauma, which is a source of frustration for trauma-trained therapists). The supervisor steadily emphasized the necessity to adhere to the manual and the mandate not to veer into discussions about the trauma and its meaning. At various times, role-playing was used to generate solutions to various problems. Fifty-two sessions were randomly selected for fidelity rating by the supervisor throughout the course of the trial. The supervisor used a standardized form, sampling five or six key components of fidelity for each session, depending on the complexity of the manualized material for that session. Errors found in these ratings were immediately discussed with the therapist involved to address any drift from the model. Session ratings from the reviewed sessions indicated 99% fidelity to the manual. With respect to therapist session ratings, 2% of sessions had problems arise that led to departure from the agenda (2% of sessions entailed strategies not included in the manual, no sessions entailed engaging in more than 15 min of off-task discussion, and 80% of sessions had a homework compliance score of 1 or 2).

Statistical Analysis

Power Calculation

We used the RMASS2 Power Calculation software to determine an adequate sample size to detect a differential effect size for the SDS selected based on a trial by Lang et al. (2017) that used the SDS, which showed a differential effect size from baseline to a 3-month follow-up of d = 0.33. Presuming significant within-subject Level 1 clustering and between-site Level 2 clustering, we generated the sample size necessary to have 90% power to detect the effect size of 0.33 for the longitudinal linear mixed-effects model, presuming an Auto Regression, AR(1) correlation structure for the within-subject measurements and statistically significant clustering variance between the four treatment sites. The requisite sample size for 90% power was N = 168, presuming 1:1 randomization.

Data Analysis Plan

Using SAS 9.4 and R/R Studio, intent-to-treat (ITT) linear mixed-effect models (LMM) were used to assess the differential treatment effects (the interaction of arm and time) on symptom severity from baseline to final follow-up assessment. All analyses were performed at the two-tailed, 95% level of confidence. Based on an examination of the data, a linear piecewise representation of time was used to fit the mixed-effect models, with two estimated linear slopes between baseline and posttreatment assessments and the posttreatment to 6-month follow-up assessment. For the B-IPF and the DAR, a linear model was used from baseline to 6-month follow-up to best model change trajectory. For each measure, “time” was composed of three 3-month intervals over which the change in symptom trajectory was measured, starting from baseline. The presence of random variation, such as treatment site and between-subject cluster effects, was tested. There was statistically significant between-subject variance but no evidence of additional site-based variance; thus, the site was modeled as a fixed effect, along with baseline scores of respective measures. The between-subject variance was statistically significant in terms of individual change in symptom trajectory across all time intervals; consequently, we incorporated random slopes for change over time at the participant level into the mixed-effect models. Within and between-treatment standardized effect sizes of regression coefficients (Cohen’s d) were calculated using t-to-d conversion. To control the false discovery rate at .05 level of significance under multiple testing, we applied the Benjamini and Hochberg (1995) correction. To complement the ITT LMM analyses, we conducted observational complete case, per protocol analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) analyses to further examine between arm bitemporal change trajectories (namely, baseline to posttreatment and baseline to 3- and 6-month follow-up, respectively; presented in Supplemental Materials).

Linear mixed-effects models assume missingness at random (MAR), which is a strong assumption that cannot be explicitly proved to classify all missing data. We therefore performed pattern-mixture modeling for the ITT LMM analyses, which assumes that there is an influence of missingness not at random (MNAR; Hedeker & Gibbons, 2006). We determined three distinct treatment adherence patterns, namely, participants who: (a) completed therapy and all follow-up assessments, (b) completed therapy but did not complete the follow-up assessments, and (c) did not complete therapy. We compared an MNAR-weighted average growth curve to the growth curves produced by the MAR-assuming LMM models to test the robustness of the ITT LMM conclusions to missingness assumptions. Except for the CTS-2 Psychological Aggression and the QDS, we did not find statistically significant moderation of missingness pattern on the treatment arm by time differential in the other measures; the MAR assumption pertinent to those analyses is robust and warranted. These analyses and results are described in the Supplemental Materials.

To index clinical significance, we used the Jacobson and Truax (1991) method to classify participants into clinical outcome categories. First, we determined if a given cross-sectional posttreatment endpoint score indicated a shift to putative functional statistical normality. We used published cutoffs, if available. If a criterion was not available, we calculated the “Criterion C” cutoff score, which is the midpoint between the population clinical and nonclinical distributions, calculated when normed data were available. If normed data were not available, we calculated the “Criterion A” cutoff score from our study group, which is calculated as two standard deviations below the baseline mean of the sample. Second, we determined if the change from baseline to a posttreatment interval was not an artifact of measurement error. The change score associated with statistically reliable change is called the reliable change index (RCI) threshold. The RCI is calculated by ([x2−x1]/SEdiff), where x1 represents the participant’s pretreatment total score, x2 represents the participant’s posttreatment or follow-up total score, and SEdiff is the standard error of difference between the two test scores. SEdiff is calculated from the test–retest reliability coefficient of a given measure and the baseline standard deviation. An RCI larger than 1.96 reflects the change that exceeds measurement error (statistically reliable individual-level change). When published RCI thresholds were unavailable, we calculated them using our sample. At each follow-up, individuals were classified as probably recovered if they passed the criterion cutoff and the RCI criteria; improved if they passed only the RCI criterion; unchanged if they failed to pass the RCI; or deteriorated if they passed the RCI criterion but symptom scores increased. Fisher’s exact test for differences in proportions was used to compare the prevalence of categories between arms at each follow-up.

Results

Participants

Study participants were predominantly in their mid late 30s, male, non-Hispanic White, and formerly enlisted in the military, with an average of 11 years of service, with some post high school education. Table 1 provides a detailed description of participant characteristics.

Attendance

Fifty-six (63%) of the participants in the AD-E arm completed treatment, and 50 (59%) participants in the PCT arm completed treatment, defined by receiving 12 sessions within the allotted 16-week interval. There was no statistically significant difference in the proportions of treatment completers between AD-E and PCT (OR = 1.19, 95% CI [.62, 2.29], Fisher’s p = .62). The modal number of sessions attended in both arms was 12. The mean number of sessions attended in the AD-E arm was 9.24 (SD = 4.25); the mean number of sessions attended in the PCT arm was 9.07 (SD = 4.20). There was no statistically significant difference in the number of sessions attended between AD-E and PCT, mean difference = 0.17, 95% CI [−1.10, 1.43], t(172) = 0.26, p = .80. Sixty-seven (75%) in the AD-E arm and sixty-one (72%) in the PCT arm completed eight or more treatment sessions. There was no statistically significant difference in proportions of participants completing 8+ sessions between AD-E and PCT (OR = 1.20, 95% CI [.58, 2.150], Fisher’s p = .36). Thirty-five (40%) in the AD-E arm and 36 (42%) in the PCT arm completed eight or more treatment sessions and all follow-up assessments. There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of participants completing 8 + sessions and all follow-up assessments (OR = 0.88, 95% CI [0.46, 1.69], Fisher’s p = .76). Participants with missing data did not differ on baseline demographics or baseline outcomes.

The complete case per protocol observational analyses (presented in Supplemental Materials) were composed of participants with available data for the components of the bitemporal change slopes for each time interval (i.e., participants with observed baseline and posttreatment measurements). Because these participants were in the majority treatment completers, we regarded the complete case analysis sample as per protocol. For example, in the AD-E arm, those participants with available baseline and posttreatment SDS scores attended a mean of 11.94 sessions (SD = 0.31); in the PCT arm, the mean was 11.43 (SD = 2.00).

Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive information for measures at each interval per arm is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Outcome Descriptives per Arm and Cross-Sectional Between Arm t Tests

| Outcome and time point | AD-E | PCT | Difference between meansa | 95% CI | p b | Cohen’s d (differential) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | |||||

| Functioning | ||||||||||

| SDS | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 89 | 20.43 | 5.01 | 85 | 20.31 | 5.19 | 0.12 | [−1.41, 1.65] | .88 | 0.03 |

| Posttreatment | 51 | 9.76 | 6.43 | 56 | 14.04 | 7.91 | −4.27 | [−7.05, −1.49] | .02 | 0.60 |

| 3 months | 43 | 13.21 | 8.83 | 52 | 15.38 | 7.71 | −2.18 | [−5.35, 1.00] | .24 | 0.28 |

| 6 months | 37 | 11.22 | 6.87 | 38 | 15.66 | 7.40 | −4.44 | [−7.73, −1.16] | .02 | 0.63 |

| B-IPF | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 85 | 60.58 | 21.71 | 82 | 61.06 | 19.38 | −0.48 | [−6.77, 5.81] | .88 | 0.02 |

| Posttreatment | 49 | 52.68 | 25.96 | 59 | 55.97 | 24.77 | −3.28 | [−12.98, 6.42] | .67 | 0.13 |

| 3 months | 47 | 43.47 | 36.86 | 51 | 52.87 | 24.44 | −9.39 | [−20.53, 1.75] | .36 | 0.34 |

| 6 months | 39 | 41.12 | 25.95 | 40 | 51.73 | 25.31 | −10.61 | [−22.10, 0.88] | .28 | 0.42 |

| Mental and behavioral health | ||||||||||

| CAPS-5 | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 89 | 36.08 | 11.88 | 85 | 35.69 | 13,69 | 0.38 | [−3.43, 4.20] | .84 | 0.03 |

| Posttreatment | 59 | 21.78 | 18.53 | 66 | 30.74 | 14.92 | −8.96 | [−13.80, −4.12] | .00 | 0.67 |

| 3 months | 54 | 24.33 | 13.65 | 52 | 29.5 | 14.43 | −5.16 | [−10.58, 0.25] | .08 | 0.37 |

| 6 months | 40 | 21.16 | 13.07 | 39 | 27.41 | 14.47 | −6.25 | [−12.48, −0.02] | .10 | 0.44 |

| DAR | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 85 | 30.27 | 12.90 | 81 | 32.32 | 12.06 | −2.05 | [−5.89, 1.78] | .29 | 0.16 |

| Posttreatment | 49 | 24.63 | 13.96 | 59 | 29.10 | 15.17 | −4.44 | [−10.05, 1.17] | .16 | 0.31 |

| 3 months | 46 | 22.52 | 14.53 | 52 | 28.96 | 15.10 | −6.44 | [−12.40, −0.48] | .06 | 0.43 |

| 6 months | 40 | 20.85 | 14.28 | 39 | 28.51 | 13.37 | −7.66 | [−13.86, −1.46] | .08 | 0.55 |

| CTS-2 Psychologicalc | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 85 | 2.71 | 1.34 | 82 | 2.65 | 1.31 | 0.07 | [−0.34, 0.47] | .75 | 0.05 |

| Posttreatment | 49 | 1.92 | 1.46 | 59 | 2.30 | 1.31 | −0.37 | [−0.90, 0.16] | .23 | 0.27 |

| 3 months | 43 | 1.63 | 1.50 | 50 | 2.01 | 1.54 | −0.38 | [−1.01, 0.25] | .96 | 0.25 |

| 6 months | 38 | 1.80 | 1.51 | 39 | 2.19 | 1.38 | −0.39 | [−1.05, 0.27] | .96 | 0.27 |

| CTS-2 Physicalc | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 85 | 0.34 | 0.99 | 82 | 0.20 | 0.61 | 0.14 | [−0.11, 0.39] | 1.00 | 0.17 |

| Posttreatment | 49 | 0.25 | 0.67 | 59 | 0.29 | 0.81 | −0.04 | [−0.33, 0.24] | .78 | 0.05 |

| 3 months | 43 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 50 | 0.21 | 0.86 | −0.13 | [−0.40, 0.15] | .48 | 0.20 |

| 6 months | 38 | 0.08 | 0.30 | 39 | 0.21 | 0.75 | −0.13 | [−0.39, 0.13] | .62 | 0.23 |

| QDS | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 82 | 3.51 | 5.14 | 81 | 3.89 | 5.50 | −0.38 | [−2.02, 1.27] | .65 | 0.07 |

| Posttreatment | 49 | 1.67 | 3.16 | 59 | 4.25 | 7.08 | −2.58 | [−4.75, −0.42] | .08 | 0.47 |

| 3 months | 46 | 2.41 | 4.44 | 51 | 4.80 | 8.63 | −2.39 | [−5.20. 0.42] | .12 | 0.35 |

| 6 months | 39 | 1.67 | 3.67 | 39 | 4.90 | 9.48 | −3.23 | [−6.47, 0.01] | .10 | 0.45 |

Note. Table 2 depicts the mean and standard deviation of each outcome score at each time point, as well as the results of the t test for between-treatment arm mean differences. AD-E = Adaptive Disclosure–Enhanced; PCT = present-centered therapy; CI = confidence interval; SDS = Sheehan Disability Scale; B-IPF = Brief Inventory of Psychosocial Functioning; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; CAPS-5 = Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition; DAR = Dimensions of Anger Reactions; CTS-2 = Conflict Tactics Scale 2: Psychological Aggression and Physical Assault subscales; QDS = Quick Drinking Screen.

A difference in means that is negative indicates that AD-E has lower symptom severity than PCT.

The p values are corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure for multiple tests.

The CTS-2 subscales were log-transformed to address right-skewness and to better approximate a normal distribution.

Functioning Outcomes

SDS Scores

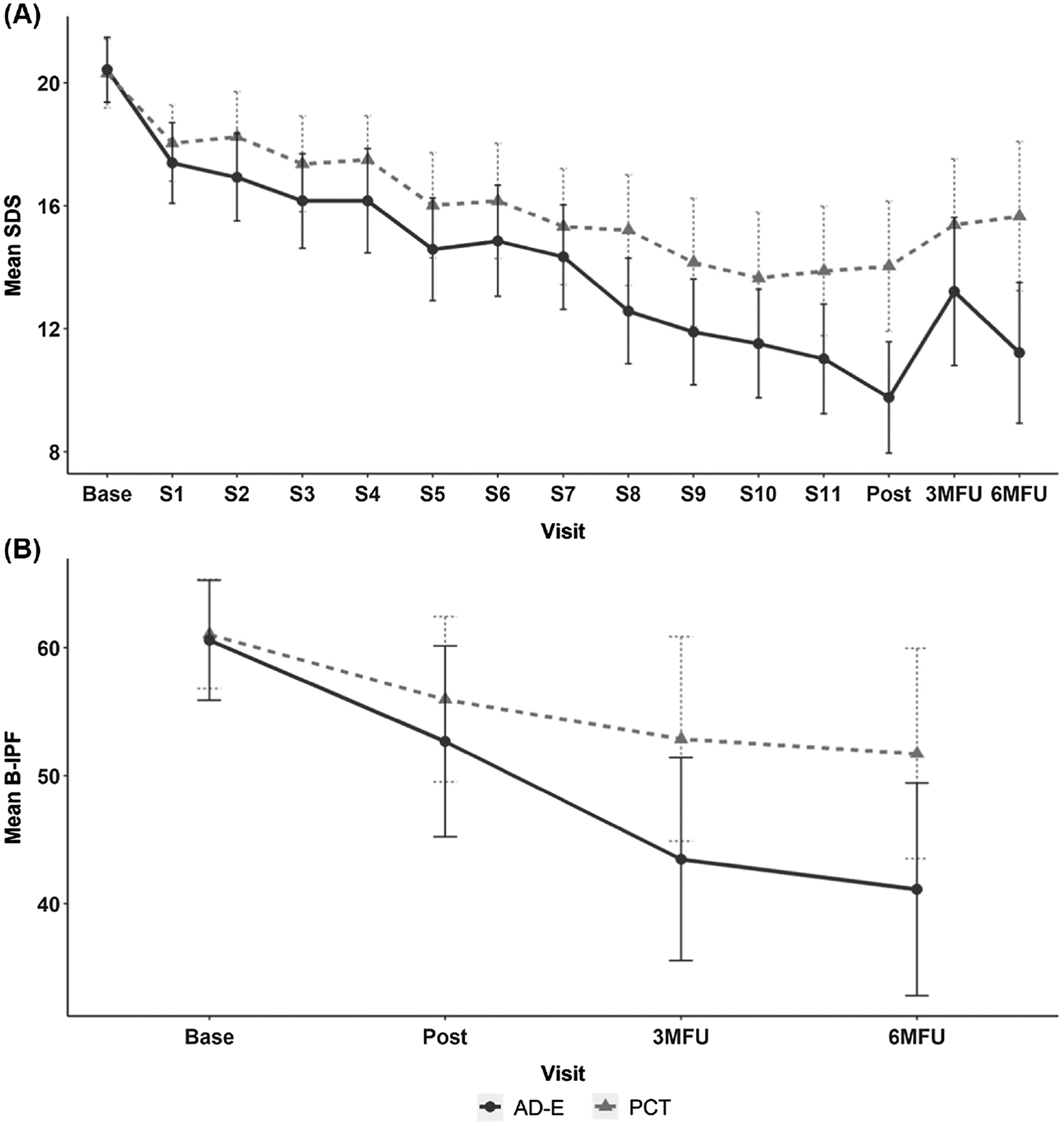

The ITT mixed-model analysis revealed that while both treatments led to large effect size improvements in SDS scores from baseline to posttreatment (p < .001; see Figure 2), AD-E led to greater improvements in that timeframe (p < .001; see Table 3; this differential effect size remained statistically significant when corrected for multiple tests using the Benjamini–Hochberg method). The treatment differential in the posttreatment to 6-month follow-up timeline was not statistically significant (see Table 3).

Figure 2.

Raw Mean Functioning Measures Scores and 95% Confidence Intervals Over the Course of Treatment and the Posttreatment Follow-Up Intervals

Note. Panels A and B depict means and 95% confidence interval at each assessment interval for the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) and the Brief Inventory of Psychosocial Functioning (B-IPF). Base = baseline visit; S1–S11 = treatment Sessions 1–11; post = posttreatment visit; 3MFU = 3-month follow-up visit; 6MFU = 6-month follow-up visit; AD-E = Adaptive Disclosure–Enhanced; PCT = present-centered therapy.

Table 3.

Results of Intent-to-Treat Linear Mixed Models Assessing Treatment Effects Over Time

| Outcome and time interval | AD-E | PCT | Comparison | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | df | t | d | B | df | t | d | B | df | t | d | |

| Functioning | ||||||||||||

| SDS | ||||||||||||

| Pre–post | −8.97 | 160 | −15.73 | 2.97*** | −6.62 | 160 | −11.74 | 1.86*** | −2.36 | 1,510 | −2.92 | 0.15***b |

| Post–6 months | 1.10 | 1,510 | 2.11 | 0.11* | 1.75 | 1,510 | 3.45 | 0.18*** | −0.65 | 1,510 | −0.90 | 0.05 |

| B-IPF | ||||||||||||

| Pre–6 months | −6.81 | 116 | −4.35 | 0.81*** | −2.37 | 116 | −1.55 | 0.29 | −4.44 | 328 | −2.03 | 0.22* |

| Mental and behavioral health | ||||||||||||

| CAPS-5 | ||||||||||||

| Pre–post | −11.88 | 131 | −9.14 | 1.60*** | −5.23 | 131 | −4.10 | 0.72** | −6.66 | 348 | −3.65 | 0.39***b |

| Post–6 months | 0.08 | 348 | 0.07 | 0.01 | −1.28 | 348 | −1.15 | 0.12 | 1.36 | 348 | 0.87 | 0.09 |

| DAR | ||||||||||||

| Pre–6 months | −2.99 | 116 | −3.85 | 0.71*** | −1.18 | 116 | −1.55 | 0.29 | −1.81 | 327 | −1.67 | 0.19 |

| CTS-2 psychologicala | ||||||||||||

| Pre–post | −0.83 | 116 | −6.40 | 1.18*** | −0.47 | 116 | −3.78 | 0.70*** | −0.37 | 319 | −2.03 | 0.23* |

| Post–6 months | −0.10 | 319 | −0.96 | 0.11 | −0.02 | 319 | −0.19 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 319 | −0.56 | 0.06 |

| CTS-2 physicala | ||||||||||||

| Pre–post | −0.13 | 116 | −1.39 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 116 | 1.18 | 0.13 | −0.23 | 319 | −1.82 | 0.20 |

| Post–6 months | −0.03 | 319 | −0.51 | 0.06 | −0.07 | 319 | −1.00 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 319 | 0.37 | 0.04 |

| QDS | ||||||||||||

| Pre–post | −0.76 | 114 | −1.35 | 0.25 | 0.34 | 114 | 0.63 | 0.12 | −1.10 | 316 | −1.42 | 0.16 |

| Post–6 months | −0.04 | 316 | −0.08 | 0.001 | 0.57 | 316 | 1.21 | 0.14 | −0.60 | 316 | −0.89 | 0.10 |

Note. B = mean change in symptom trajectory over 3-month intervals, within- and between-treatment arms, produced by linear mixed-effect models. d = Cohen’s d standardized effect size of mean change over time. AD-E = Adaptive Disclosure–Enhanced; PCT = present-centered therapy; df = degrees of freedom; SDS = Sheehan Disability Scale; B-IPF = Brief Inventory of Psychosocial Functioning; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; CAPS-5 = Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition; DAR = Dimensions of Anger Reactions; CTS-2 = Conflict Tactics Scale 2: Psychological Aggression and Physical Assault subscales; QDS = Quick Drinking Screen.

The CTS-2 subscales were log-transformed to address right-skewness and to better approximate a normal distribution.

Statistically significant after Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

B-IPF Scores

The ITT mixed-model analysis revealed that while both treatments led to significant improvements in B-IPF scores from baseline to the 6-month follow-up (for AD-E, p < .001, for PCT, p = .010), AD-E led to greater improvements in that timeframe (p = <.001; see Table 3). However, this differential effect was not statistically significant after the Benjamini–Hochberg multiple test correction.

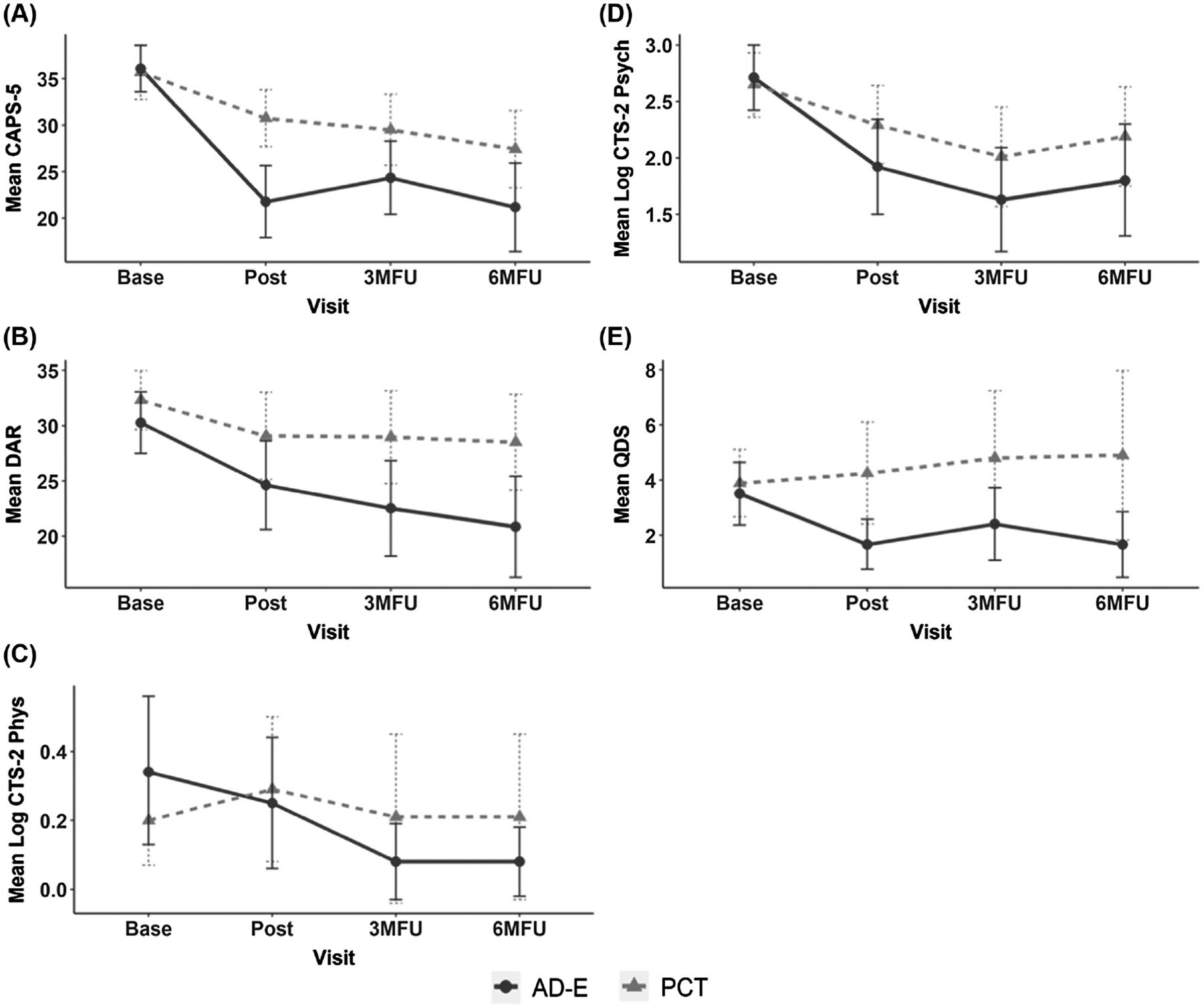

PTSD

The ITT mixed-model analysis revealed that while both treatments led to significant improvements in CAPS-5 scores from baseline to posttreatment (p < .001), AD-E led to greater improvements in that timeframe (p = .02; see Table 3 and Figure 3); this differential effect size remained statistically significant after Benjamini–Hochberg correction. The treatment differential in the posttreatment to 6-month follow-up timeline was not statistically significant (see Table 3).

Figure 3.

Raw Mean Mental and Behavioral Health Measure Scores and 95% Confidence Intervals Over the Course of Treatment and the Posttreatment Follow-Up Intervals

Note. Panels A–E depict means and 95% confidence interval at each assessment interval for Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5), Dimensions of Anger Reactions (DAR), the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-2) Psychological Aggression and Physical Assault subscales, and the Quick Drinking Screening (QDS). The CTS-2 Psychological Aggression and Physical Assault subscales were log-transformed to address right-skewness in the distribution to better approximate normality. Base = baseline visit; post = posttreatment visit; 3MFU = 3-month follow-up visit; 6MFU = 6-month follow-up visit; AD-E = Adaptive Disclosure–Enhanced; PCT = present-centered therapy; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition.

Externalizing

Anger

The ITT mixed-model analysis revealed that while both AD-E and PCT led to significant improvements in DAR scores from baseline to 6-month follow-up (p < .001), there was not a statistically significant treatment differential (see Table 3).

Aggressive Behaviors

We log-transformed CTS-2 scores because they were heavily positively skewed in conjunction with zero inflation. There were also extreme tail values, which caused the distribution to deviate from an approximate normality. The clinical significance tests require approximate normality for valid classification. However, for CTS-2 Physical Assault, the measure was too zero-inflated, such that a log transformation could not approximate a normal distribution (and the measure could not be used for J&T calculations).

Psychological Aggression

The ITT mixed-model analysis revealed that while both AD-E and PCT led to significant improvements in the log-transformed CTS-−2 Psychological Aggression scores from baseline to posttreatment (p < .001; see Table 3), AD-E led to greater improvements in that time frame (p = .03; see Table 3). However, this differential was no longer statistically significant after Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

Physical Assault Behaviors

The ITT mixed-model analysis did not reveal statistically significant change within or between the treatment arms in the log-transformed CTS-2 Physical Assault subscale scores. An examination of the distribution of scores revealed zero inflation and a high degree of positive skew, which suggests a floor effect made statistical tests impossible.

Alcohol Use

The ITT mixed-model analysis also did not reveal statistically significant change within or between the treatment arms in the QDS scores. Our study group endorsed minimal to normal drinking and an examination of the distribution of scores revealed zero inflation and a high degree of positive skew, which also suggests a floor effect made statistical tests impossible.

Individual Case Clinical Significance Outcomes

The results of the individual-level clinical significance for the functional and PTSD outcomes are depicted in Supplemental Table S2. One of the limitations of the Jacobson and Truax methodology is that classifications require observed data. Because of lowered observed data in the two follow-up intervals, the likelihood of Type II error is arguably substantially high for these results. Consequently, we only mention posttreatment findings here. The most noteworthy finding is that 21% more participants in the AD-E arm were classified as probably recovered (57%) than participants in the PCT arm (36%) based on SDS scores (OR = 2.35, 95% CI [1.02, 5.56], Fisher’s p = .03). For the CAPS-5 measure, the proportion of participants classified as probably recovered between AD-E (15%) and PCT (3%) was also statistically significant (OR = 5.69, 95% CI [1.11, .56.35], Fisher’s p = .02). Finally, for the CTS-2, Psychological Aggression subscale, the proportion of participants classified as probably recovered between AD-E (21%) and PCT (3%) was statistically significant (OR = 7.40, 95% CI [1.41, 74.22], Fisher’s p = .01).

Per-Protocol (Complete Case) Results (Presented in Supplemental Materials)

The complete case/per protocol observational ANCOVA analyses for SDS scores revealed medium statistically significant differential effect sizes between AD-E and PCT from baseline to posttreatment and from baseline to the 6-month follow-up. The complete case ANCOVA observational analysis for CAPS-5 scores revealed medium statistically significant differential effect sizes between AD-E and PCT from baseline to posttreatment, and from baseline to the 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Finally, the complete case ANCOVA observational analysis for B-IPP and DAR scores revealed medium statistically significant differential effect sizes between AD-E and PCT from baseline to the 3- and 6-month follow-ups.

Adverse Events

There were 97 adverse events (52 [54%] in the AD-E arm and 45 [46%] in the PCT arm); the majority (>68%) were related to physical ailments, and all were unrelated to study procedures. Serious adverse events were rare (AD-E = 1; PCT = 2). COVID-19 started halfway into this trial; another milestone stressor was the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. Twenty-five participants mentioned this event at their baseline and/or follow-up assessments, and 19 of those (76%) reported that the event affected their PTSD symptoms (no arm differences).

Discussion

We conducted a multisite randomized controlled trial comparing AD-E with PCT in veterans with TL/MI-related PTSD. AD-E is unique in that it specifically aims to restore functioning to repair loss- and moral-injury-related traumatic harms, and this was the only randomized controlled individual psychotherapy trial of a PTSD treatment to date that examined functioning as one of several primary outcomes. As predicted, the ITT analyses revealed AD-E to be more efficacious than PCT (ranging from small to low medium differential effects) from baseline to posttreatment in terms of SDS and PTSD scores. With respect to SDS scores, 57% of the AD-E cases with available data also probably recovered at posttreatment, compared to 36% of the PCT cases. In addition, 12% more AD-E cases probably recovered on the CAPS-5.

With respect to mean changes in PTSD symptom severity, one prior high-quality individual psychotherapy trial of women veterans with PTSD compared PCT and prolonged exposure (PE), and the investigators found a small pre- to posttreatment differential effect (Schnurr et al., 2007). Another high-quality trial of mixed-sex service members with PTSD found that PE was not superior to PCT (Foa et al., 2018). Although the within AD-E ITT effect sizes in this trial were very large and two times the PCT effect sizes, the magnitude of the between-arm pre- to posttreatment effect size for the full ITT models was low moderate (.39). This confirmed that, although AD-E was somewhat superior to PCT, PCT remains an uncomplicated, evidence-based patient-directed simplified problem-solving approach to functional challenges related to military-related trauma (see B. T. Litz et al., 2019). Unfortunately, efficacy trials are not suitable to determine who would most benefit from AD-E and whether these results will generalize to practice. Future practice-based research is needed to test the effectiveness of AD-E, particularly among cases that providers expect to have the motivation and capacity to complete treatment, and a stepped-care model, starting with the least restrictive alternative, PCT, should be tested.

This was the first trial of an individual psychotherapy for military-related PTSD to show any degree of superiority relative to PCT with respect to functioning. Although no prior individual psychotherapy trial for veterans with PTSD examined functioning as a primary outcome, Schnurr et al. (2007) and Holliday et al. (2015) failed to find differences in functioning/quality of life as secondary outcomes between PCT and PE and CPT, respectively. A cognitive therapy, trauma-informed guilt reduction therapy led to greater changes in guilt and PTSD in veterans who endorsed guilt than supportive psychotherapy (which they framed as a modified PCT without the problem-solving and homework designed to address present-day stressors and functioning), but quality of life remained unchanged by either intervention (Norman et al., 2022; this trial suggests that problem solving to promote functional changes is an active component of PCT and PCT with these features is a bona fide therapy). There is interest in framing PTSD as a chronic condition and benchmarking success in functional terms (e.g., Schnurr & Lunney, 2016), yet the standard of care continues to be symptom-based with the hope that collateral functional changes will occur. Evidence-based individual CBTs for military-related PTSD, which have not been shown to substantially change functioning in veterans with PTSD, should consider testing modifications that address functioning. If treatment success should be defined by changes in functioning and quality of life, why not target these directly, as in AD-E?

Even though AD-E is more demanding than PCT, is trauma-focused, and AD-E can entail intense experiential in- and extrasession activities (e.g., visiting the grave of a lost person), an equal percentage of participants in AD-E (66%) completed treatment relative to PCT (61%), and 75% of participants in AD-E and 72% in PCT completed eight or more sessions. However, in prior trials of CBT for PTSD, PCT was associated with less dropout than trauma-focused therapies (e.g., Belsher et al., 2019; B. T. Litz et al., 2019), and the frequency of dropouts in the PCT arm in our trial was higher than previous trials. It is possible that a relatively higher percentage of veterans dropped out before completing PCT because the treatment failed to be meaningful or resonate emotionally in terms of the intense moral emotions that characterize TL/MI (anger, guilt, shame, and disgust). This is an empirical question that will need to be addressed in future research. Finally, even though we attempted to prevent allegiance effects in the PCT training and supervision, we cannot rule these out, and allegiance effects could have led to less engagement and interest in PCT. Consequently, this may have been an internal validity problem that biased the results in favor of AD-E.

There were no between AD-E and PCT (differential) effect sizes on primary outcomes between posttreatment and the 6-month follow-up interval. For SDS scores, the null result appears to be due to a statistically significant within-treatment arm uptick in scores in both AD-E and PCT. Although the pattern of results does not entail a substantive deterioration in AD-E (or PCT) at the follow-up intervals, we plan to interrogate the potential for a decline in gains made over time to generate testable hypotheses about ways of mitigating these problems in AD-E.

There are several limitations to this trial. First, as stated above, because the therapists provided both therapies, allegiance effects cannot be ruled out. Second, although all participants endorsed a TL/MI trauma (either from personal transgressions or mistakes, bearing witness to grave inhumanity, or being the victim of other’s cruelty) or to a lesser degree an event that was a life threat significantly colored by TL or MI, we failed to measure prolonged grief symptoms or MI as an outcome. The first issue was an oversight; the second omission was the result of the lack of a treatment-valid measure of MI as an outcome at the time the trial was planned (this situation has since changed; see B. T. Litz et al., 2022). Third, half of the participants were not evaluated at 6 months. This means that the results are biased by participants who were motivated or able to be assessed. Although there is no reason to expect any bias between arms, the follow-up results need to be replicated. Fourth, we evaluated functioning by paper and pencil measures, which introduce potential response bias and retrospection error. Fifth, we studied veterans seeking treatment at VA hospitals, consisting of a majority of White men, and most were noncommissioned service members. It is unclear whether the findings generalize to veterans who are not seeking care at the VA, which could include individuals who distrust the VA. Generalizability may also be limited for women, who frequently experience different types of morally injurious trauma, non-White individuals, whose trauma frequently occurs within the context of identity-based bias, or individuals who served as officers, whose responsibilities and duties may differ in ways that alter one’s sense of responsibility in the context of trauma. Sixth, whether AD-E leads to greater changes in aggressive behavior and alcohol use will need to be addressed in subsequent research. For unknown reasons, our study group stands out by endorsing chiefly nominal physical aggression, and virtually no problem drinking. It may be that research will need to use samples with comorbid substance abuse, which may also increase the probability of physical aggression problems. Finally, AD-E is a multifarious therapy with varied change agents that are applied flexibly, based on patient preference and exigencies, to ensure success experiences with respect to the healing and repair plan. Consequently, empirical questions remain about the necessity and impact of individual change agents.

Future practice-based research is needed to determine the effectiveness of AD-E in other populations with PTSD. Additional trauma contexts that are high risk for TL/MI and as a result are uniquely appropriate to consider AD-E include health care workers in untenable professional binds leading to various transgressive experiences and when there are grave workplace and leadership failures (e.g., during pandemics), first responders, traumas that entail bearing witness to human cruelty, United Nations peacekeepers, refugee and political violence trauma, accidental maiming and killing, being the victim of cruelty and brutality, victims of terrorism, severe trust violations/high-stakes betrayal, loss of loved ones to violence, and incarcerated individuals with lifespan MI related to personal transgression and being the victim of others and systemic transgressions. Finally, although an empirical question, AD-E would likely be as effective for high-stakes MI that does not entail a concurrent Criterion-A traumatic event nor PTSD (B. T. Litz et al., 2022) and for prolonged grief problems, which is also a separable syndrome from PTSD (Prigerson et al., 2009).

Notwithstanding the methodological concerns, these results suggest that AD-E should be considered as an evidence-based treatment option, particularly for war veterans with TL/MI trauma and PTSD. The results appear to be sufficiently promising for researchers to consider designing and testing therapies in the rehabilitation framework, for providers to consider targeting functioning directly, and for providers to consider AD-E as an option in their toolkit to address MI and TL related to warzone exposure. AD-E may be especially useful for providers to consider when a flexible approach is indicated.

Supplementary Material

What is the public health significance of this article?

Warzone-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a highly multifarious clinical problem, partly because combat trauma can entail extensive traumatic loss and moral injury, either from personal transgressive acts or bearing witness to or being victimized by others’ transgressions. Adaptive disclosure (AD) is an evidence-based psychotherapy that was designed to help service members and veterans with war-related PTSD. We applied lessons learned from previous research on AD and enhanced AD to better help war veterans with loss- and moral-injury-related PTSD. We compared the enhanced AD (AD-E) with present-centered therapy (PCT) in a clinical trial of 174 veterans with PTSD. We found AD-E to be superior to PCT with respect to helping veterans function better and in terms of reducing PTSD symptom burden.

Acknowledgments

This trial was funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development (5I01RX002135 to Brett T. Litz; https://clinicaltrials.gov: NCT03056157).

This trial was a major multisite effort. The trial therapists—Shawnee Brew, Anne Malaktaris, Cait McLean, Brandon Griffin, Alexandra Dick, Jordana Hazam, Amy Wheelecor, Tim Usset, Jake Borst, Meaghan Mobbs, and Alison Kraus—were terrific, and the research assistants at each site—Sarah Siegel, Claudia Villierme, Edith Bonilla, Valerie Luskey, Laura Zambrano-Vazquez, Selena Baca, Mary Evans-Lindquist, Rebecca Basal-dua, Mackenzie Cummings, Ruth Chartoff, Breanna Grunthal, Maya Bina Vannini, and Stephanie Brown—made it all happen. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of their collaborator, Pollyanna Casmar, who provided guidance about loving-kindness meditation and compassion.

The contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. The AD-E treatment manual is available upon request.

Supplemental materials: https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000873.supp

References

- Au TM, Sauer-Zavala S, King MW, Petrocchi N, Barlow DH, & Litz BT (2017). Compassion-based therapy for trauma-related shame and posttraumatic stress: Initial evaluation using a multiple baseline design. Behavior Therapy, 48(2), 207–221. 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsher BE, Beech E, Evatt D, Smolenski DJ, Shea MT, Otto JL, Rosen CS, & Schnurr PP (2019). Present-centered therapy (PCT) for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2019(11), Article CD012898. 10.1002/14651858.CD012898.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfer N, & Litz BT (2023). Assessing functioning and quality of life in PTSD. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 10(1), 1–20. 10.1007/s40501-023-00284-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, & Hochberg Y (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300. 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Clark DM, Hackmann A, McManus F, & Fennell M (2005). Cognitive therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: Development and evaluation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(4), 413–431. 10.1016/j.brat.2004.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree E, & Rothbaum B (2007). Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Therapist guide: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences. Oxford University Press. 10.1093/med:psych/9780195308501.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, McLean CP, Zang Y, Rosenfield D, Yadin E, Yarvis JS, Mintz J, Young-McCaughan S, Borah EV, Dondanville KA, Fina BA, Hall-Clark BN, Lichner T, Litz BT, Roache J, Wright EC, Peterson AL, & the STRONG STAR Consortium. (2018). Effect of prolonged exposure therapy delivered over 2 weeks vs 8 weeks vs present-centered therapy on PTSD symptom severity in military personnel: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 319(4), 354–364. 10.1001/jama.2017.21242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D, Alkemade N, Mitchell D, Elhai JD, McHugh T, Bates G, Novaco RW, Bryant R, & Lewis V (2014). Utility of the Dimensions of Anger Reactions–5 (DAR-5) scale as a brief anger measure. Depression and Anxiety, 31(2), 166–173. 10.1002/da.22148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Legarreta M, North L, DiMuzio J, McGlade E, & Yurgelun-Todd D (2016). A preliminary study of DSM-5 PTSD symptom patterns in Veterans by trauma type. Military Psychology, 28(2), 115–122. 10.1037/mil0000092 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MJ, Nash WP, & Litz BT (2017). When self-blame is rational and appropriate: The limited utility of Socratic questioning in the context of moral injury: Commentary on Wachen et al. (2016). Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 24(4), 383–387. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2017.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MJ, Schorr Y, Nash W, Lebowitz L, Amidon A, Lansing A, Maglione M, Lang AJ, & Litz BT (2012). Adaptive disclosure: An open trial of a novel exposure-based intervention for service members with combat-related psychological stress injuries. Behavior Therapy, 43(2), 407–415. 10.1016/j.beth.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, & Gibbons RD (2006). Longitudinal data analysis. Wiley-Interscience. [Google Scholar]

- Holliday R, Williams R, Bird J, Mullen K, & Surís A (2015). The role of cognitive processing therapy in improving psychosocial functioning, health, and quality of life in veterans with military sexual trauma-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Services, 12(4), 428–434. 10.1037/ser0000058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, & Truax P (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12–19. 10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley LP, Weathers FW, McDevitt-Murphy ME, Eakin DE, & Flood AM (2009). A comparison of PTSD symptom patterns in three types of civilian trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(3), 227–235. 10.1002/jts.20406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman SE, Bovin MJ, Black SK, Rodriguez P, Brown LG, Brown ME, Lunney CA, Weathers FW, Schnurr PP, Spira J, Keane TM, & Marx BP (2020). Psychometric properties of a brief measure of posttraumatic stress disorder-related impairment: The Brief Inventory of Psychosocial Functioning. Psychological Services, 17(2), 187–194. 10.1037/ser0000306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AJ, Schnurr PP, Jain S, He F, Walser RD, Bolton E, Benedek DM, Norman SB, Sylvers P, Flashman L, Strauss J, Raman R, & Chard KM (2017). Randomized controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy for distress and impairment in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(Suppl. 1), 74–84. 10.1037/tra0000127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwack SD, Jackson CE, Chen M, Sloan DM, Hatgis C, Litz BT, & Marx BP (2014). Validation of the use of video teleconferencing technology in the assessment of PTSD. Psychological Services, 11(3), 290–294. 10.1037/a0036865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz B, & Carney JR (2018). Employing loving-kindness meditation to promote self- and other-compassion among war Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 5(3), 201–211. 10.1037/scp0000174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Berke DS, Kline NK, Grimm K, Rusowicz-Orazem L, Resick PA, Foa EB, Wachen JS, McLean CP, Dondanville KA, Borah AM, Roache JD, Young-McCaughan S, Yarvis JS, Mintz J, & Peterson AL (2019). Patterns and predictors of change in trauma-focused treatments for war-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(11), 1019–1029. 10.1037/ccp0000426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Lebowitz L, Gray MJ, & Nash WP (2017). Adaptive disclosure: A new treatment for military trauma, loss, and moral injury. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Plouffe RA, Nazarov A, Murphy D, Phelps A, Coady A, Houle SA, Dell L, Frankfurt S, Zerach G, Levi-Belz Y, & the Moral Injury Outcome Scale Consortium. (2022). Defining and assessing the syndrome of moral injury: Initial findings of the Moral Injury Outcome Scale Consortium. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, Article 923928. 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.923928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Rusowicz-Orazem L, Doros G, Grunthal B, Gray M, Nash W, & Lang AJ (2021). Adaptive disclosure, a combat-specific PTSD treatment, versus cognitive-processing therapy, in deployed marines and sailors: A randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. Psychiatry Research, 297, Article 113761. 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, Lebowitz L, Nash WP, Silva C, & Maguen S (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(8), 695–706. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neria Y, & Litz BT (2004). Bereavement by traumatic means: The complex synergy of trauma and grief. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 9(1), 73–87. 10.1080/15325020490255322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman SB, Capone C, Panza KE, Haller M, Davis BC, Schnurr PP, Shea MT, Browne K, Norman GJ, Lang AJ, Kline AC, Golshan S, Allard CB, & Angkaw A (2022). A clinical trial comparing trauma-informed guilt reduction therapy (TrIGR), a brief intervention for trauma-related guilt, to supportive care therapy. Depression and Anxiety, 39(4), 262–273. 10.1002/da.23244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paivio SC, & Greenberg LS (1995). Resolving “unfinished business”: Efficacy of experiential therapy using empty-chair dialogue. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63(3), 419–425. 10.1037/0022-006X.63.3.419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Horowitz MJ, Jacobs SC, Parkes CM, Aslan M, Goodkin K, Raphael B, Marwit SJ, Wortman C, Neimeyer RA, Bonanno GA, Block SD, Kissane D, Boelen P, Maercker A, Litz BT, Johnson JG, First MB, & Maciejewski PK (2009). Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLOS Medicine, 6(8), Article e1000121. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Monson CM, & Chard KM (2016). Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD: A comprehensive manual. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Nishith P, Weaver TL, Astin MC, & Feuer CA (2002). A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(4), 867–879. 10.1037/0022-006X.70.4.867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Engel CC, Foa EB, Shea MT, Chow BK, Resick PA, Thurston V, Orsillo SM, Haug R, Turner C, & Bernardy N (2007). Cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in women: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 297(8), 820–830. 10.1001/jama.297.8.820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, & Lunney CA (2016). Symptom benchmarks of improved quality of life in PTSD. Depression and Anxiety, 33(3), 247–255. 10.1002/da.22477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, & Dunbar GC (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(Suppl. 20), 22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan KH, & Sheehan DV (2008). Assessing treatment effects in clinical trials with the discan metric of the Sheehan Disability Scale. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 23(2), 70–83. 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f2b4d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, & Resick PA (2018). A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(3), 233–239. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ER, Duax JM, & Rauch SA (2013). Perceived perpetration during traumatic events: Clinical suggestions from experts in prolonged exposure therapy. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(4), 461–470. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.12.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Agrawal S, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Young LJ, Cunningham JA, & Simco ER (2003). Comparison of a quick drinking screen with the timeline followback for individuals with alcohol problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64(6), 858–861. 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp MM, Litz BT, Hoge CW, & Marmar CR (2015). Psychotherapy for military-related PTSD: A review of randomized clinical trials. JAMA, 314(5), 489–500. 10.1001/jama.2015.8370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, & Douglas EM (2004). A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence and Victims, 19(5), 507–520. 10.1891/vivi.19.5.507.63686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy SUE, & Sugarman DB (1996). The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17(3), 283–316. 10.1177/019251396017003001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wachen JS, Evans WR, Jacoby VM, & Blankenship AE (2021). Cognitive-processing therapy for moral injury. In Currier JM, Drescher KD, & Nieuwsma J (Eds.), Addressing moral injury in clinical practice (pp. 143–161). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/0000204-009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Bovin MJ, Lee DJ, Sloan DM, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, Keane TM, & Marx BP (2018). The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychological Assessment, 30(3), 383–395. 10.1037/pas0000486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, & Schnurr PP (2013). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp

- Yeterian JD, Berke DS, & Litz BT (2017). Psychosocial rehabilitation after war trauma with adaptive disclosure: Design and rationale of a comparative efficacy trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 61, 10–15. 10.1016/j.cct.2017.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.