Abstract

While newer, more potent tyrosine kinase inhibitors have largely addressed drug resistance due to acquired BCR-ABL1 kinase domain point mutations in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), sequential treatment can select for compound mutations that exhibit high level resistance to all approved ABL1 inhibitors. We previously showed that such compound mutants can, however, be effectively targeted by combining the ATP-site inhibitor ponatinib and the allosteric inhibitor asciminib. Here, we report the first clinical validation of this approach in a CML patient harboring a BCR-ABL1 T315I/E355G compound mutant, along with dissection of the structural mechanism underlying the cooperative binding of both drugs to this mutant kinase. Our findings provide a strong basis for combination therapy to overcome BCR-ABL1 compound mutant resistance in patients.

Keywords: combination therapy, compound mutations, allosteric inhibitor, resistance, CML

INTRODUCTION

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI)-based therapy dramatically changed the landscape for the treatment of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), effectively transforming an invariably fatal, progressive malignancy into a well managed disease with which most patients now live a normal life span (1). For those patients who develop resistance, the most common mechanism is through point mutations acquired in the kinase domain of the oncogenic BCR-ABL1 fusion protein (2). However, years of research, trials, and development have resulted in an impressive arsenal of multiple FDA-approved TKIs targeting the ABL1 ATP-binding site, which currently includes imatinib, nilotinib, dasatinib, bosutinib, ponatinib. The rational application of these drugs effectively facilitates control of resistance in most BCR-ABL1 kinase domain mutation-driven cases as well as provides alternative options for managing intolerance to individual TKIs (3).

Among the currently approved ATP-site ABL1 inhibitors, the only one which effectively targets the highly resistant T315I gatekeeper mutant is ponatinib (4). While resistant patients harboring T315I or other point mutations demonstrate sensitivity to ponatinib (5), limitations regarding dose-dependent increased risk for vascular occlusive events and tolerability have presented additional challenges in the clinic for its broader use (6). These challenges have been at least partly addressed with the subsequent development of asciminib, the first FDA-approved ABL1 TKI to target the allosteric myristoylation pocket (7), which has proved effective and well-tolerated in patients with T315I mutant, albeit requiring increased doses than those indicated for non-T315I patients (8).

While the collection of available ABL1 kinase inhibitors for CML largely enables effective control of BCR-ABL1 point mutation-driven resistance, the sequential application of these drugs in disease management has been shown to select for compound mutations, where two or more mutations occur in the same BCR-ABL1 molecule (9). In contrast to their point mutant counterparts, compound mutants often exhibit increased degrees of resistance to multiple or all approved ABL1 TKIs (10), presenting a daunting, unmet challenge for treating affected patients. Recently, we showed that such compound mutants can be effectively targeted by combining the ATP-site inhibitor ponatinib and the allosteric inhibitor asciminib (11). To date, however, validation of this strategy in patients has not been studied.

Here, we report the first clinical validation of this approach in a CML patient harboring a BCR-ABL1 T315I/E355G compound mutant, along with dissection of the structural mechanism underlying this mutant kinase.

METHODS

Patient consent

Prior to participation in this study, informed consent was obtained from the patient in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and under the approval of the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board (eIRB# 4422).

Combination treatment protocol

Given that asciminib had not yet been granted approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration at the time of this study, we petitioned for and received approval from Novartis to obtain compassionate use asciminib for this patient. Commercially available ponatinib was co-prescribed under the indication of her history and persistence of a BCR-ABL1 T315I mutation. Combination treatment was approved under a single-patient investigational new drug (IND) protocol, with starting doses of ponatinib at 15 mg QD and asciminib at 40 mg BID with the possibility of dose escalation based on tolerance and response. Relevant lab values and responses were collated from the patient’s medical records over the course of treatment.

Mutation analysis

Total RNA was isolated from patient mononuclear cells using the Qiagen RNeasy protocol, and cDNA was synthesized with the Superscript Vilo kit. The BCR-ABL1 kinase domain was amplified using Accuprime Taq-based PCR and primers upstream of the p210 breakpoint in BCR (forward; 5’-TTCAGAAGCTTCTCCCTGACAT-3’) and downstream of the end of the kinase domain of ABL1 (reverse; 5’-AGCTCTCCTGGAGGTCCTC-3’). PCR products were purified by Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (Millipore) and subjected to Sanger sequencing (Eurofins Genomics) using primers flanking the ABL1 kinase domain: forward (5’-ACCACGCTCCATTATCCAGCC-3’) and reverse (5’-CCTGCAGCAAGGTAGTCA-3’).

Drug transporter gene expression analysis

For timepoints prior to and during treatment with the combination of ponatinib and asciminib, total RNA was isolated and analyzed by qPCR for relative gene expression of a panel of 10 different human drug transporter genes as described [REF: Qiang et al., Leukemia 2017]. For comparison, gene expression levels were also tested in two control cell lines: K562 cells and K562-R cells (adapted for resistance to asciminib with reported upregulation of the ABCG2 transporter).

Cell line generation and drug sensitivity assays

The T315I and E355G mutations were originally introduced individually into the p210 BCR-ABL1 sequence in the pSRα retroviral vector by site directed mutagenesis as described previously (12). To generate the compound mutant construct, the BCR-ABL1 T315I pSRα plasmid was linearized by BsrGI-SrfI restriction digest, swapping out 1.4 kb sequence of wild-type sequence downstream of the mutation with a PCR amplicon of the identical region containing the E355G mutation by InFusion recombinatorial cloning (Takara). The resulting BCR-ABL1 mutant pSRα constructs were then used to transfect HEK293T cells by Fugene and pEcoPack method, and retroviral supernatant was used to spinnoculate murine Ba/F3 cells as described (12). Infected cells were selected using G418 (Gibco) and withdrawn from media containing IL-3. For drug sensitivity assays, cells were seeded (1000/well) into 384-well plates in the presence of graded concentrations of TKIs alone or in combination, tested in quadruplicate. Plates were cultured for 72 h at 37°C with 5% CO2 prior to analysis by standard MTS-based colorimetric absorbance assay (Promega) on a BioTek Synergy2 plate reader. Synergy calculations were performed across a 7x7 concentration matrix of both drugs using the zero interaction potency (ZIP) model, and analyzed via the ‘synergyfinder’ R package (13).

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of inhibitor for 6 h at 37°C, then lysed in 1X Cell Lysis buffer (Cell Signaling) supplemented with a cocktail of protease inhibitors (cOmplete Mini tablet; Roche), 1% v/v phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma #P5726) and 1% v/v phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; Sigma #93482) for 30 min on ice. Clarified lysate supernatant was quantified for protein concentration using standard BCA assay (Fisher) per the manufacturer’s protocol and analyzed on a BioTek Synergy 2 plate reader. Equal amount (50 ug) of protein was loaded into each lane and samples were run on a pre-cast 4–15% Tris-Glycine gel (Biorad), transferred to PVDF membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore) overnight, blocked in 5% BSA solution for 1 h at room temp, and probed for primary antibodies against phospho-CRKL (Cell Signaling #3181S) and β-tubulin (Sigma #05-661). Membranes were washed 3x with TBS-T buffer, incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, washed again, and membranes were imaged using a Biorad Chemi Doc instrument.

Miniaturized single-cell immunofluorescence imaging

For three samples from this patient with sufficient cells, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were purified using standard Ficoll-Paque separation protocol according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (GE healthcare Life Sciences). PBMCs were fixed in paraformaldehyde (PFA) and permeabilized prior to conducting immunostaining. Cells were blocked (8% normal goat serum and 2% BSA) and labelled with selected antibodies: CD34 A488 (clone QBEnd10, R&D Systems #FAB7227G, and one of the four phosphoprotein antibody from Cell Signaling Technologies – pERK (clone D13.14.4E, #4370), pSTAT5 (Tyr 694; #9359), pCRKL (Tyr 207, #3181), and pAKT (Ser 473, clone D9E, #4060). All the phospho-antibodies were detected using a secondary anti-rabbit BV480 antibody. HCS NuclearMask Deep Red Stain was used as a nuclear counterstain (Invitrogen #H10294). Imaging was performed with an epi-fluorescent microscope (Zeiss Observer Z1) at 20X magnification. Images were acquired in 4 channels (DIC, A488, BV480 and A647) with 5 slices per fluorescent channel. Single cells from the images were detected using CellProfiler (V2.1.1) and single-cell fluorescence of the protein target in each channel was quantified using custom written MATLAB software. Single-cell fluorescent values were further analyzed by quantifying phosphoprotein expression levels in CD34+ cells.

NMR spectroscopy analysis

The constructs of ABL1b229–515 mutants were generated by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent) and cloned in the pET16b vector for expression as maltose binding protein (MBP)-His6 fusion proteins including a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site. ABL1 constructs were expressed and purified as described previously (14). The methyl-protonated samples in an otherwise deuterated background were prepared as described (15,16) by supplementing the medium with 50 mg/L α-ketobutyric acid, 90 mg/L α-ketoisovaleric acid, 50 mg/L of [13CH3]-Met, and 50 mg/L of [2H2, 13CH3]-Ala one hour before the IPTG induction. [U-2H; Ala-13CH3; Met-13CH3; Ile-δ1-13CH3; Leu/Val-13CH3/12CD3]-labelled ABL1 variants were prepared in 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.1) containing 75 mM NaCl, 3.0 mM BME, in 100% 2H2O. NMR experiments were acquired on Bruker 800 MHz spectrometers equipped with cryogenic probes at 10 °C. All NMR data were processed using NMRPipe (17) and analyzed using NMRFAM-Sparky (18). The sidechain methyl resonance assignment of T389Y/E355G mutant was achieved by comparing with the methyl assignment of the wild-type and T389Y mutant.

RESULTS

Patient clinical history

A 52-year-old female initially presented to her local clinic with abnormal uterine bleeding. Notable past medical history included Graves’ disease with thyroidectomy and thyroid replacement, Addison’s disease requiring corticosteroid and minimum mineral and corticosteroid replacement therapy, and degenerative joint disease. She underwent uterine biopsy which was negative for malignancy and was given a course of medroxyprogesterone acetate to halt her bleeding. Subsequent blood work showed a gradual thrombocytosis that approached 600–800x103 platelets/μL within 5 months, accompanied at that time by concurrent mild leukocytosis without evidence of a left-shift on peripheral blood. She was followed expectantly over the next 6 months on hydrea for suspected myeloproliferative disorder before being referred to the OHSU Center for Hematologic Malignancies. At this point, a bone marrow biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), with karyotype analysis interestingly showing all 20 abnormal metaphases harboring both the t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) classic Philadelphia chromosome along with a second rearrangement between chromosomes 11 and 15 (t(11;15)(q13.1;q15)), which was confirmed to be constitutional in origin. FISH studies confirmed 91% positivity for the double BCR and ABL1 fusion signal pattern; BCR-ABL1 transcripts were detected at a level of 49% on the international scale. Her marrow featured 100% cellularity, myeloid hyperplasia with left-shift in maturation to eosinophilia and basophilia, marked megakaryocytic hyperplasia and atypia, and some increased fibrosis. Peripheral blood showed basophilia and rare circulating blasts, and the patient demonstrated no splenomegaly upon examination. Together, these findings were consistent with low-risk CML in the chronic phase.

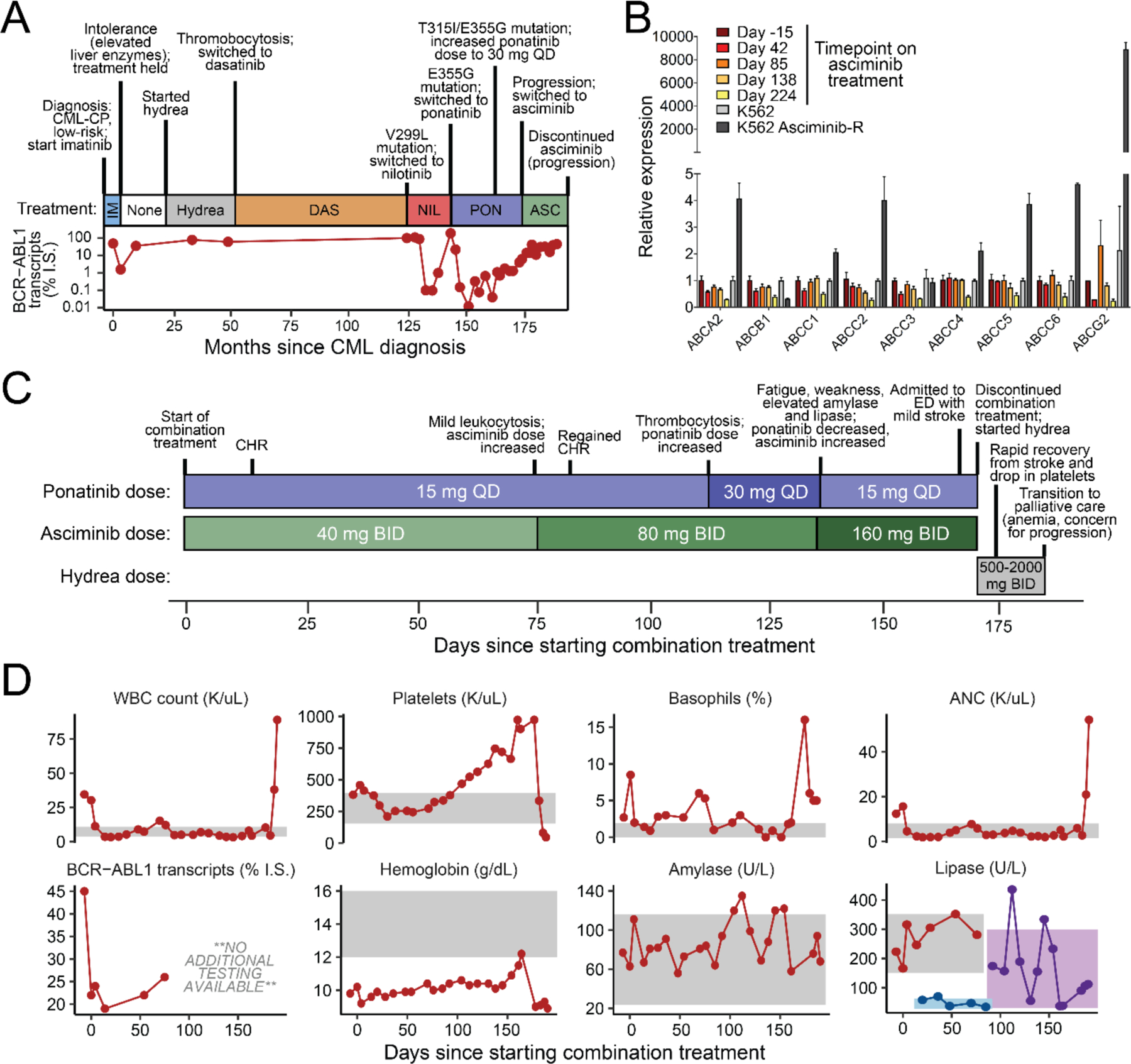

She was initially treated with imatinib at a dose of 400 mg QD combined with low-dose cytarabine (20 mg/m2, given days 15 to 28 of each 28-day cycle), but quickly developed substantial toxicity to protocol-based therapy. Subsequent re-challenge with imatinib alone resulted in elevated liver enzymes, prompting discontinuation (Figure 1A). Over the next four years, she was managed with hydroxyurea alone, until her platelet counts rose to between 1.5 and 2 million/μL. Consequently, she was switched to dasatinib at an initial dose of 50 mg BID, but developed thrombocytopenia and neutropenia. She was treated with varying dosing regimens of dasatinib over the next six years, ranging from 100 mg QD to 20 mg three times a week. Despite this, she was unable to maintain a complete hematologic response (CHR). At the time of dasatinib discontinuation, mutation analysis showed evidence of a V299L mutation, a known resistance liability for this drug. Over the course of the following 18 months, she was treated with nilotinib, initially at a dose of 400 mg BID. However, prompt development of grade 3 lipase and grade 2 amylase elevation necessitated dose modifications, which ranged from 400 mg QAM and 200 mg QHS to eventually 400 mg QD due to elevation in pancreatic enzymes at higher doses. In addition, she again developed resistance, this time with emergence of a new E355G mutation. This mutation along with the V299L mutant were confirmed to be present in two different clones, rather than as a compound variant. NGS-based sequencing revealed the presence of an additional ASXL1 Y591* mutation, though bone marrow aspirate staging at this time confirmed that she remained in chronic phase.

Figure 1. Clinical history and response of a CML patient harboring a compound mutation to combined therapy with ponatinib and asciminib.

(A) Schematic highlighting a relevant timeline of the patient’s diagnosis and response to past TKI therapies. CML-CP: chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase. (B) Gene expression levels of a panel of drug transporter genes from different timepoints on past treatments. Levels for K562 and asciminib-resistant K562 cells are included as controls. (C) Schematic highlighting timeline, dosing changes, and response of the patient, who harbored a BCR-ABL1 T315I/E355G compound mutant at baseline, to combination treatment with ponatinib and asciminib. CHR: complete hematologic response. (D) Changes in levels of the patient’s relevant clinical lab values over the course of combination treatment.

As both of the detected BCR-ABL1 mutants have been shown to be sensitive to ponatinib (4), she was started on ponatinib at a dose of 30 mg QD. Her leukemia was initially sensitive to ponatinib, achieving greater than a major molecular response (MMR; defined as <0.1% BCR-ABL1 transcript levels on the international scale) within six months. Despite a good response to ponatinib, she had significant difficulties tolerating this medication and her dose was reduced to 15 mg QD a little over a year on treatment. Within six months following this dose reduction, however, her BCR-ABL1 transcript levels had increased to 1.1% and mutational analysis showed high levels of both the previously detected E355G mutation and a newly acquired T315I mutation. Given concerns about the ability to control these mutations, her dose of ponatinib was subsequently increased to 30 mg QD. Despite this dose increase, her BCR-ABL1 transcripts continued to increase to 6.3% over the course of the next 7 months, with mutational analysis again showing T315I and E355G (Figure 1A). In this case, the predominant levels of these two variants (with virtually no wild-type sequence detected) were confirmed to represent a compound mutant acquired and expanded on treatment.

Although the patient was evaluated for a possible allogeneic stem cell transplant, she preferred to pursue non-transplant options. She was eligible for and enrolled on a phase 1 clinical trial using asciminib, an allosteric ABL1 kinase inhibitor with efficacy against T315I and several other common BCR-ABL1 mutants (8). Unfortunately, consistent with preclinical predictions of T315I-inclusive compound mutation insensitivity to asciminib (11), even with initial control of her blood counts, she quickly lost a complete hematological response despite being on a maximally tolerated dose of 200 mg BID. Additional survey of multiple drug transporter genes for which various ABL1 TKIs, including asciminib, are substrates (19,20) revealed no altered levels of expression potentially contributing to resistance (Figure 1B).

Clinical response and outcome to ponatinib + asciminib combination treatment

Based on previous work from our group showing that the addition of asciminib can re-sensitize highly resistant T315I-inclusive BCR-ABL1 compound mutants to ponatinib (11), we negotiated approval from Novartis to obtain compassionate use asciminib to combine with commercially available ponatinib to treat this patient under an approved single-patient IND protocol, as asciminib had not yet received FDA approval. Combination treatment was initiated with a dose of ponatinib at 15 mg QD combined with asciminib at 40 mg BID, and within two weeks she achieved a CHR, despite having failed each drug individually previously (Figure 1C & D). After ~2.5 months, she showed mild leukocytosis with left shift concerning for progression, prompting an increase in asciminib dose to 80 mg BID with continuation of ponatinib 15 mg QD. This resulted in normalization of her counts, which remained stable over the next 2 months, after which point labs began to show gradually increasing thrombocytosis. Consequently, her dose of ponatinib was increased to 30 mg QD. Unfortunately, her platelet counts continued to rise and she developed intolerance on this combination dosing with significant worsening of fatigue and weakness, so she was changed to asciminib at 160 mg BID with a dose reduction of ponatinib to 15 mg QD (Figure 1C & D).

Unfortunately, ~1 month later she was admitted to her local hospital with a mild stroke and a platelet count greater than 1x106/μL. Given concerns of the association of ponatinib with vaso-occlusive events (6) and inability of the ponatinib/asciminib combination to control her persistent thrombocytosis, both of these medications were discontinued and the patient was started on hydrea (500 mg BID) along with continuing aspirin and adding Plavix. She achieved a rapid and full recovery from her stroke, with eventual normalization of her platelets following an increased hydrea dose of 2000 mg BID (Figure 1C & D). However, at this point she remained significantly anemic and showed evidence of increased basophilia, again concerning for possible disease progression. At this point, the patient and her family made the decision to discontinue treatment and enroll in hospice comfort care, and the patient passed away one week later.

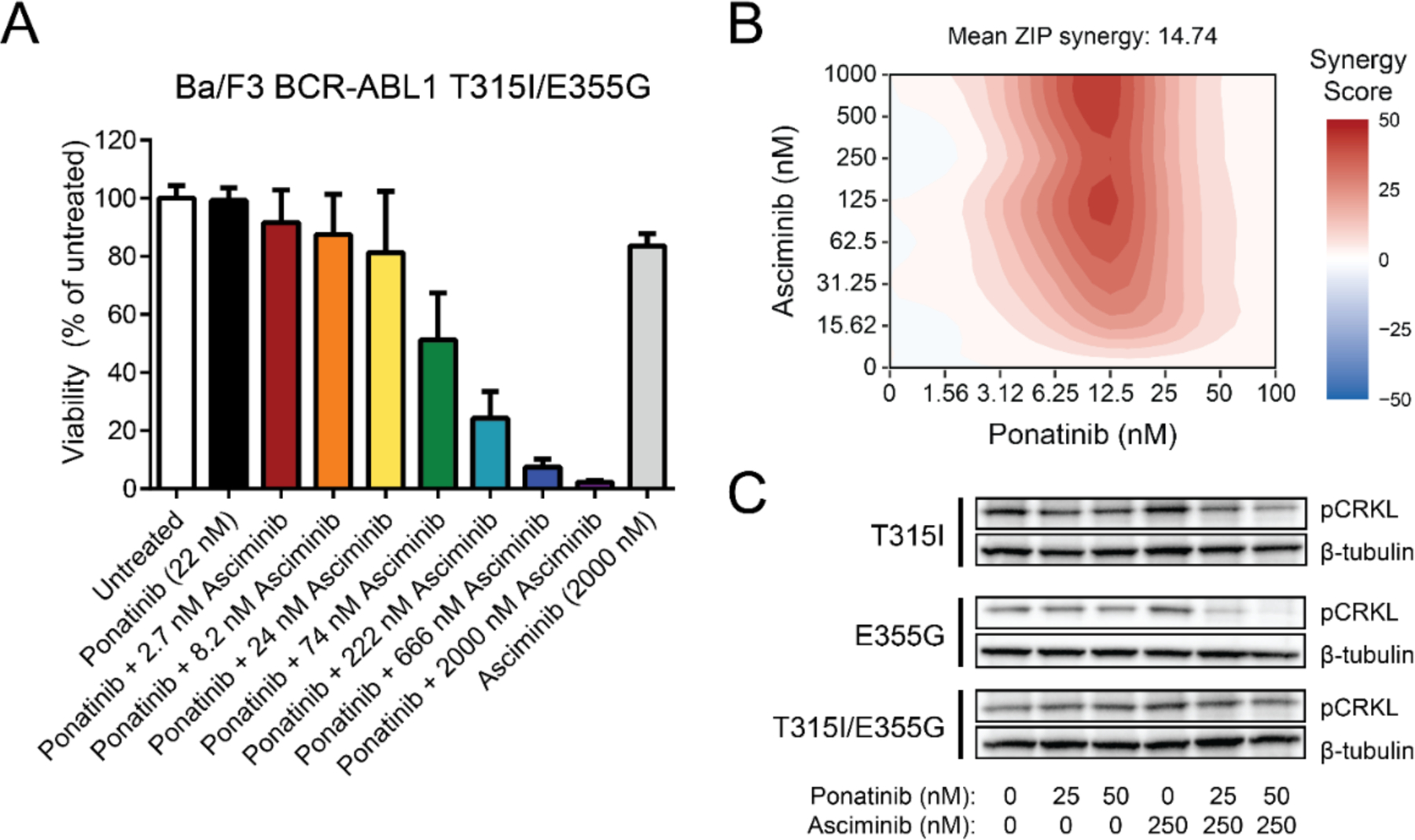

Resistance conferred by the BCR-ABL1 T315I/E355G compound mutant in vitro can be overcome by the combination of ponatinib and asciminib

The T315I/E355G compound mutation remained the dominant clone throughout this patient’s treatment, with no detectable wild-type trace or additional mutations by Sanger sequencing of the ABL1 kinase domain. In order to better characterize the unique properties of the BCR-ABL1 T315I/E355G compound mutant observed in this patient, Ba/F3 cells engineered to express the compound mutant construct were screened with respect to single-agent or combination treatment with ponatinib and asciminib. The T315I/E355G compound mutant showed insensitivity to asciminib and decreased sensitivity to ponatinib compared to either the T315I or E355G mutation alone (Supplemental Figure S1). Although the mutant showed some inhibition by ponatinib alone, this was only at higher concentrations that are either not tolerated or achievable physiologically in patients (21). However, addition of increasing concentrations of asciminib to a clinically achievable concentration of ponatinib (22 nM) demonstrated enhanced inhibition of cellular proliferation, despite the concentrations of each single agent having any no effect alone (Figure 2A). Evaluation of the activity of the combination of ponatinib + asciminib in these cells across an expanded matrix of possible dose combinations revealed strong synergy of the two agents (Figure 2B). Immunoblot analysis confirmed that despite varying levels of inhibition of BCR-ABL1 activity (as measured by levels of phosphorylated adapter protein CRKL) by ponatinib in the T315I and E355G single mutants alone, combination with higher doses of asciminib were required to begin to inhibit CRKL phosphorylation in T315I/E355G compound mutant cells (Figure 2C). Together, these data suggest that, consistent with the patient’s response, the T315I/E355G compound mutant confers resistance to both ponatinib and asciminib alone, but the combination of both drugs leads to synergistic inhibition.

Figure 2. In vitro sensitivity of the BCR-ABL1 T315I/E355G compound mutant to single-agent versus combination treatment with ponatinib and asciminib.

(A) Ba/F3 cells expressing BCR-ABL1 T315I/E355G were treated in vitro with ponatinib and asciminib alone or in combination at the indicated concentrations for 72 h. Viability normalized to untreated cells is shown, with each bar representing the mean ± SEM for four independent replicates. (B) Synergy of the combination in Ba/F3 BCR-ABL1 T315I/E355G cells across a dose matrix of possible concentrations. Synergy was calculated using the zero interaction potency (ZIP) model, where the heatmap reflects regions of synergy (red), additivity (white), and antagonism (blue). The mean synergy value across the full matrix of combined doses is shown. (C) Immunoblot analysis of Ba/F3 cells expressing BCR-ABL1 with a T315I, E355G, or T315I/E355G mutation. Cells were treated in vitro for 4 h with the indicated concentrations of each inhibitor, then probed for CRKL phosphorylation levels by western blot, as a readout of BCR-ABL1 kinase activity. β-tubulin was included as a loading control.

Single-cell imaging suggests eventual loss of clinical response potentially due to BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent mechanism

Although this patient achieved a rapid hematologic response on combination treatment and maintained stable disease for several months, only a transient and shallow reduction in BCR-ABL1 transcript levels was observed, suggesting that despite inhibition of BCR-ABL1 kinase activity other resistance mechanisms may have emerged on treatment. To address this, primary patient mononuclear cells isolated from samples from various timepoints on treatment (Days 0, 14, and 75) for which sufficient cell material was available were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with antibodies for CD34 and four phosphorylated kinases representing pathways activated downstream of BCR-ABL1: AKT, CRKL, ERK, and STAT5. Quantification of phosphoprotein levels within the CD34+ population revealed over the course of treatment a shift in the overall distribution towards cells expressing lower levels of pAKT, pCRKL, and pSTAT5 while simultaneous enriching for cells expressing higher levels of pERK (Figure 3A & B). This was most pronounced at Day 75 of treatment, which corresponded to an uptick in the patient’s white count to ~15 K/uL, necessitating an increase in the dose of asciminib within the combination treatment. At this timepoint, imaging of individual CD34+ cells showed notably brighter co-expression of pERK than at baseline (Figure 3C), suggesting evidence of reactivation of a potential survival escape pathway.

Figure 3. Evidence of dysregulated, BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent resistance pathway activation prior to combination treatment discontinuation.

(A) Violin-plot distributions of overall fluorescence intensity values for phosphoprotein markers from single-cell imaging analysis of primary patient cells conducted at various timepoints on combination treatment. Mononuclear cells isolated at the indicated timepoints were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for each of the indicated phosphoproteins along with CD34. Analysis shown is confined to those cells expressing CD34. (B) Breakdown of relative expression levels of each phosphoprotein with the CD34+ cells from the patients at the indicated timepoints on combination treatment. Expression level for each marker in each cell analyzed per sample was binned into high (orange), intermediate (green), and low (blue) groups defined by the top quartile, middle 50%, and bottom quartile of fluorescence intensity, respectively. (C) Select fields of view and inset zoom on a representative cell comparing pERK expression from baseline and Day 75 timepoints. Cells of interest within the view are highlighted with dashed yellow boxes, and example zoomed views of one of those cells is show in the inset. Images of the identical field of view for each stain (differential interference contrast (DIC) only, CD34 (green), and pERK (purple)) are shown for both timepoints on treatment.

Coupling of the T315I and E355G mutants results in a dramatic shift toward an active kinase conformational state with diminished binding for single-agent asciminib and ponatinib

Given the observed phenotype of decreased sensitivity to both ponatinib and asciminib for the T315I/E355G compound mutant compared to either constituent mutation alone, the structural underpinnings of this resistance were pursued. Two-dimensional 1H-13C heteronuclear correlation NMR analysis was performed using a control ABL1 T389Y mutant, which shifts the innate equilibrium of ABL1 kinase towards the inactive state to which imatinib binds (I2) (22), facilitating baseline visibility of both the active (A) and I2 states to enable ease of direct comparison. Importantly, the introduction of the E355G substitution markedly depleted the I2 state, with only the A state being detectable, consistent with the highly activating effect of this mutant (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the effect of the chemical shift induced by the E355G mutant is long-range (Fig. 4B), strongly affecting many residues including those of the αF-helix of the myristoylation pocket (Fig. 4C). Given that the T315I gatekeeper mutant has been reported previously to also shift the equilibrium toward the active state (22), these data suggest that the T315I/E355G compound mutant ABL1 kinase very strongly favors an active conformational state while depleting an inactive conformation conducive to durable binding of ponatinib and asciminib.

Figure 4. NMR-based structural impact of the T315I/E355G compound mutant on ABL1 kinase conformational state.

(A) 2D heteronuclear correlation NMR analysis of the impact of the ABL1 E355G mutation. The relative abundance of both the inactive conformation of ABL1 kinase to which imatinib binds (I2) and the active conformation of the kinase are indicated in the 1H-13C plots shown for key kinase residues. The ABL1 T389Y mutation serves as a control which induces an approximately equal abundance of both conformational states for visualization; addition of the E355G mutant on top of this background control reveals a dramatic shift toward favoring the active conformation. (B) Mapping chemical shift perturbations (CSP) caused by the E355G mutation onto ABL1 kinase domain. The Glu side chain is shown with stick representation, and methyl groups throughout are shown as spheres, where the coloration (yellow through red) indicate the increasing degree of chemical shift perturbation observed at that position as a result of the mutation. For reference, the activation loop is highlighted in blue. (C) 1H-13C correlations are shown for select residues identified as having large or small to medium degree of CSP as a result of the E355G mutation.

DISCUSSION

Despite the largely effective management of BCR-ABL1 point mutation-based resistance with the currently available set of single-agent ABL1 TKI therapies, BCR-ABL1 compound mutations acquired on sequential treatment confer increased resistance to most if not all of these drugs. In vitro studies suggest that this is particularly true for those compound mutations which include T315I (10), in part due to their significantly increased resistance to ponatinib and asciminib, the only two of the approved TKIs retaining activity against the T315I point mutation. Compound mutations have been reported in patients with resistance to both ponatinib (5,10) and asciminib (8,11), and at least in the case of ponatinib such mutations appear more common among patients with advanced disease compared to those in chronic phase (23).

The patient described in this study acquired a T315I/E355G compound mutant on ponatinib treatment, driving relapse but remaining in chronic phase throughout. The patient generally tolerated combination treatment with ponatinib + asciminib well, particularly at starting drug doses of 15 mg QD and 40 mg BID, respectively. The steady increase in platelets beginning around Day 110 on combination treatment was initially mild, but progressed rapidly to extreme thrombocytosis and did not resolve despite dose adjustment until the treatment was ultimately held and the patient was switched to hydrea, aspirin, and Plavix. Furthermore, increasing the dose of ponatinib to 30 mg unfortunately led to the patient reporting worsening fatigue and weakness (grade 3). Other non-hematological events involving mild, transient elevation of amylase and lipase levels (grade 1) were also observed with the higher dose of ponatinib, but resolved upon dose modification to 15 mg QD ponatinib + 160 mg BID asciminib. Notably, this patient also had a history of complicated intolerance issues on various other TKI therapies, including instances of thrombocytosis and elevated liver and pancreatic enzymes. Clinical trials of ponatinib and asciminib have also reported low-grade adverse events involving fatigue, elevations in amylase and lipase, as well as instances of thrombocytopenia (5,8) rather than the increased platelets observed in this patient’s course.

In terms of response, rapid achievement (within 2 weeks) of CHR on the starting doses of the combination treatment and an increased asciminib dose tracked with maintenance of stable disease for nearly 4 months. While the initial rapid response tracked with a decrease in BCR-ABL1 transcripts, the depth of response on the starting dose appeared shallow with levels subsequently creeping back up despite hematologic count control. However, due to travel considerations with the patient being managed at her local clinic for most of the trial, BCR-ABL1 transcripts were not able to be tested later in the course of combination treatment, precluding knowing the precise level of molecular response eventually achieved. While the depth and timing to achieving molecular response in newly diagnosed CML patients is strongly associated with the relative long-term risk of relapse (24), the landscape becomes more complicated among heavily pre-treated relapsed patients such as the patient in this study. Nonetheless, the hematologic response seen in this patient who had previously failed both of these two drugs individually represents an important validation of the approach. Evaluation in additional patients with longer follow-up and potentially with a history of fewer TKI-related toxicities would help better answer questions as to the depth of response possible on such a combination regimen.

It appears possible that, in addition to harboring a highly resistant BCR-ABL1 compound mutation, this patient may have also on combination treatment exhibited some evidence of a BCR-ABL1 kinase mutation-independent resistance mechanism. Notably, at the time the T315I/E355G mutation was detected at relapse on ponatinib therapy, additional NGS-based sequencing panels revealed the presence of an additional mutation in ASXL1. Unfortunately, additional similar sequencing was not feasible for earlier timepoints given a lack of stored material, making it difficult to know exactly when the ASXL1 mutation was acquired. In the context of CML, mutations of genes such as ASXL1 in patients at diagnosis have been associated with poorer responses to TKI treatments and increased risk of progression (25–27). Furthermore, this patient showed evidence around Day 75 of combination treatment of enrichment of ERK phosphorylation among CD34+ cells analyzed by immunofluorescent imaging. Persistent reactivation of the ERK pathway has been previously reported to contribute to resistance in CML patients who lack BCR-ABL1 mutations, as well as to the persistence of CML stem cells on TKI therapy (28). This, combined with a known importance of MAPK pathway signaling in platelet formation and activation (29), suggests the possibility of such a mechanism contributing to the shallow molecular response and eventual thrombocytosis and progression of disease in this patient on treatment.

There are multiple intriguing aspects of the specific compound mutation harbored by this patient. First is the additional resistance conferred by these two mutations in tandem. In line with previous studies profiling T315I-inclusive BCR-ABL1 compound mutations using in vitro models, we found the T315I/E355G compound mutant showed increased resistance to ponatinib and asciminib. For example, while ponatinib exhibits in vitro IC50 values for Ba/F3 cells expressing WT or T315I of <1 and 11 nM, respectively (4), cells expressing the T315I/E355G mutant exhibited several fold-higher IC50 values that are above levels safely achievable in patients. With respect to asciminib, in vitro IC50 values in this same Ba/F3 expression vector model of 4.5 and 137 nM are observed against BCR-ABL1 WT and T315I, respectively (11), whereas we found that T315I/E355G cells were insensitive to asciminib (IC50 > 2000 nM). Consistent with previously reported resensitization of T315I-inclusive compound mutations with the combination of ponatinib and asciminib (11), despite resistance to each single agent, Ba/F3 cells expressing the T315I/E355G compound mutant are synergistically inhibited by the combination. Given that we also observed synergistic kill at a range of tested doses in vitro, this suggests opportunities for dose adjustment of both drugs while still achieving similar efficacy, with implications for managing potential toxicities.

A second point of interest regarding this specific compound mutant is the involvement of the E355G change. This mutation has been reported previously in resistance to imatinib and nilotinib (30,31), but also represents an analogous substitution to one that was reported many years ago to be constitutively activating in the highly related SRC kinase (32,33). Our studies revealed that the ABL1 E355G mutant results in a number of long-range shifts, including to the αF-helix and myristoylation pocket. Consistent with the decreased sensitivity of the E355G point mutant to asciminib but not ponatinib in vitro, one potential consequence of the mutation may be an altered asciminib pocket which limits its binding. In addition to direct steric hindrance of drug binding, an established mechanism by which many point mutations in ABL1 confer resistance to TKIs is by altering the catalytic conformational state of the kinase. In such cases, mutations effectively deplete or enrich for certain inactive or active conformation states amenable to binding of a given TKI (22). Indeed, NMR-based structural dissection of the consequence of introducing the E355G mutant revealed a strong activating phenotype in ABL1, with near complete depletion of the I2 inactive conformation. Importantly, in the context of native full-length BCR-ABL1, binding of allosteric inhibitors like asciminib to the myristoylation pocket helps further stabilize a fully-assembled inactive conformation where the SH2 and SH3 domains are docked to the back of the kinase domain (22,34). However, certain mutant forms of the full kinase (such as T315I) continue to favor an active state even in the presence of allosteric inhibitor (22). Based on previous molecular dynamics structural modeling of other T315I-inclusive compound mutants (10), given the near complete depletion of the I2 state by the T315I/E355G compound mutant, we believe these results would be consistent with a mechanism of the combination wherein ponatinib binds this highly active compound mutant, shifting the balance toward an I2-like inactive conformational state and allowing asciminib to bind for more durable, fully-assembled kinase inhibition.

In total, our findings represent the first reported clinical validation of using a combination of an ATP-site and allosteric ABL1 kinase inhibitor to target BCR-ABL1 compound mutation-driven resistance. The response observed in a patient who had previously failed both drugs separately and was literally out of targeted therapy options underscore the importance of matching resistance mechanism to actionable treatment regimens to improve outcomes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to dedicate this work to the memory of this patient. She was a smart, caring, outgoing, and funny individual who loved travel, adventure, music, her family, and her community. Her bravery and desire to advance the treatment for CML are a lasting inspiration. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/ National Cancer Institute (NCI) (R01 CA065823-21; PI: B.J.D.) and by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) (R35 GM122462; PI: C.G.K.). We also thank Orlando Antelope and Johnathan Ahmann for technical assistance.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

B.J.D. serves on scientific advisory boards for Aileron Therapeutics, Therapy Architects (ALLCRON), Cepheid, Vivid Biosciences, Celgene, RUNX1 Research Program, Novartis, Gilead Sciences (inactive), Monojul (inactive); serves on Scientific Advisory Boards and receives stock from Aptose Biosciences, Blueprint Medicines, EnLiven Therapeutics, Iterion Therapeutics, Third Coast Therapeutics, GRAIL (inactive on scientific advisory board); is scientific founder of MolecularMD (inactive, acquired by ICON); serves on the board of directors and receives stock from Amgen, Vincera Pharma; serves on the board of directors for Burroughs Wellcome Fund, CureOne; serves on the joint steering committee for Beat AML LLS; is founder of VB Therapeutics; has a sponsored research agreement with EnLiven Therapeutics; receives clinical trial funding from Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer. The remaining authors have no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bower H, Bjorkholm M, Dickman PW, Hoglund M, Lambert PC, Andersson TM. Life Expectancy of Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Approaches the Life Expectancy of the General Population. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(24):2851–7 doi 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun TP, Eide CA, Druker BJ. Response and Resistance to BCR-ABL1-Targeted Therapies. Cancer Cell 2020;37(4):530–42 doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes TP, Shanmuganathan N. Management of TKI-resistant chronic phase CML. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2022;2022(1):129–37 doi 10.1182/hematology.2022000328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Hare T, Shakespeare WC, Zhu X, Eide CA, Rivera VM, Wang F, et al. AP24534, a pan-BCR-ABL inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia, potently inhibits the T315I mutant and overcomes mutation-based resistance. Cancer Cell 2009;16(5):401–12 doi 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortes JE, Kantarjian H, Shah NP, Bixby D, Mauro MJ, Flinn I, et al. Ponatinib in refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med 2012;367(22):2075–88 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1205127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valent P, Hadzijusufovic E, Schernthaner GH, Wolf D, Rea D, le Coutre P. Vascular safety issues in CML patients treated with BCR/ABL1 kinase inhibitors. Blood 2015;125(6):901–6 doi 10.1182/blood-2014-09-594432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wylie AA, Schoepfer J, Jahnke W, Cowan-Jacob SW, Loo A, Furet P, et al. The allosteric inhibitor ABL001 enables dual targeting of BCR-ABL1. Nature 2017;543(7647):733–7 doi 10.1038/nature21702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes TP, Mauro MJ, Cortes JE, Minami H, Rea D, DeAngelo DJ, et al. Asciminib in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia after ABL Kinase Inhibitor Failure. N Engl J Med 2019;381(24):2315–26 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1902328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah NP, Skaggs BJ, Branford S, Hughes TP, Nicoll JM, Paquette RL, et al. Sequential ABL kinase inhibitor therapy selects for compound drug-resistant BCR-ABL mutations with altered oncogenic potency. J Clin Invest 2007;117(9):2562–9 doi 10.1172/JCI30890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zabriskie MS, Eide CA, Tantravahi SK, Vellore NA, Estrada J, Nicolini FE, et al. BCR-ABL1 compound mutations combining key kinase domain positions confer clinical resistance to ponatinib in Ph chromosome-positive leukemia. Cancer Cell 2014;26(3):428–42 doi 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eide CA, Zabriskie MS, Savage Stevens SL, Antelope O, Vellore NA, Than H, et al. Combining the Allosteric Inhibitor Asciminib with Ponatinib Suppresses Emergence of and Restores Efficacy against Highly Resistant BCR-ABL1 Mutants. Cancer Cell 2019;36(4):431–43 e5 doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.La Rosee P, Corbin AS, Stoffregen EP, Deininger MW, Druker BJ. Activity of the Bcr-Abl kinase inhibitor PD180970 against clinically relevant Bcr-Abl isoforms that cause resistance to imatinib mesylate (Gleevec, STI571). Cancer Res 2002;62(24):7149–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ianevski A, He L, Aittokallio T, Tang J. SynergyFinder: a web application for analyzing drug combination dose-response matrix data. Bioinformatics 2017;33(15):2413–5 doi 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saleh T, Rossi P, Kalodimos CG. Atomic view of the energy landscape in the allosteric regulation of Abl kinase. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2017;24(11):893–901 doi 10.1038/nsmb.3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monneau YR, Ishida Y, Rossi P, Saio T, Tzeng SR, Inouye M, et al. Exploiting E. coli auxotrophs for leucine, valine, and threonine specific methyl labeling of large proteins for NMR applications. J Biomol NMR 2016;65(2):99–108 doi 10.1007/s10858-016-0041-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossi P, Monneau YR, Xia Y, Ishida Y, Kalodimos CG. Toolkit for NMR Studies of Methyl-Labeled Proteins. Methods Enzymol 2019;614:107–42 doi 10.1016/bs.mie.2018.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR 1995;6(3):277–93 doi 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee W, Tonelli M, Markley JL. NMRFAM-SPARKY: enhanced software for biomolecular NMR spectroscopy. Bioinformatics 2015;31(8):1325–7 doi 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eadie LN, Saunders VA, Branford S, White DL, Hughes TP. The new allosteric inhibitor asciminib is susceptible to resistance mediated by ABCB1 and ABCG2 overexpression in vitro. Oncotarget 2018;9(17):13423–37 doi 10.18632/oncotarget.24393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiang W, Antelope O, Zabriskie MS, Pomicter AD, Vellore NA, Szankasi P, et al. Mechanisms of resistance to the BCR-ABL1 allosteric inhibitor asciminib. Leukemia 2017;31(12):2844–7 doi 10.1038/leu.2017.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byrgazov K, Lucini CB, Valent P, Hantschel O, Lion T. BCR-ABL1 compound mutants display differential and dose-dependent responses to ponatinib. Haematologica 2018;103(1):e10–e2 doi 10.3324/haematol.2017.176347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie T, Saleh T, Rossi P, Kalodimos CG. Conformational states dynamically populated by a kinase determine its function. Science 2020;370(6513) doi 10.1126/science.abc2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deininger MW, Hodgson JG, Shah NP, Cortes JE, Kim DW, Nicolini FE, et al. Compound mutations in BCR-ABL1 are not major drivers of primary or secondary resistance to ponatinib in CP-CML patients. Blood 2016;127(6):703–12 doi 10.1182/blood-2015-08-660977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quintas-Cardama A, Cortes JE, Kantarjian HM. Early cytogenetic and molecular response during first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: long-term implications. Cancer 2011;117(23):5261–70 doi 10.1002/cncr.26196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Branford S, Kim DDH, Apperley JF, Eide CA, Mustjoki S, Ong ST, et al. Laying the foundation for genomically-based risk assessment in chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2019;33(8):1835–50 doi 10.1038/s41375-019-0512-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Branford S, Wang P, Yeung DT, Thomson D, Purins A, Wadham C, et al. Integrative genomic analysis reveals cancer-associated mutations at diagnosis of CML in patients with high-risk disease. Blood 2018;132(9):948–61 doi 10.1182/blood-2018-02-832253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim T, Tyndel MS, Zhang Z, Ahn J, Choi S, Szardenings M, et al. Exome sequencing reveals DNMT3A and ASXL1 variants associate with progression of chronic myeloid leukemia after tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Leuk Res 2017;59:142–8 doi 10.1016/j.leukres.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma L, Shan Y, Bai R, Xue L, Eide CA, Ou J, et al. A therapeutically targetable mechanism of BCR-ABL-independent imatinib resistance in chronic myeloid leukemia. Sci Transl Med 2014;6(252):252ra121 doi 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flevaris P, Li Z, Zhang G, Zheng Y, Liu J, Du X. Two distinct roles of mitogen-activated protein kinases in platelets and a novel Rac1-MAPK-dependent integrin outside-in retractile signaling pathway. Blood 2009;113(4):893–901 doi 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kantarjian HM, Giles F, Gattermann N, Bhalla K, Alimena G, Palandri F, et al. Nilotinib (formerly AMN107), a highly selective BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is effective in patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase following imatinib resistance and intolerance. Blood 2007;110(10):3540–6 doi 10.1182/blood-2007-03-080689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shah NP, Nicoll JM, Nagar B, Gorre ME, Paquette RL, Kuriyan J, et al. Multiple BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations confer polyclonal resistance to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (STI571) in chronic phase and blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 2002;2(2):117–25 doi 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kato JY, Takeya T, Grandori C, Iba H, Levy JB, Hanafusa H. Amino acid substitutions sufficient to convert the nontransforming p60c-src protein to a transforming protein. Mol Cell Biol 1986;6(12):4155–60 doi 10.1128/mcb.6.12.4155-4160.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levy JB, Iba H, Hanafusa H. Activation of the transforming potential of p60c-src by a single amino acid change. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1986;83(12):4228–32 doi 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hantschel O, Nagar B, Guettler S, Kretzschmar J, Dorey K, Kuriyan J, et al. A myristoyl/phosphotyrosine switch regulates c-Abl. Cell 2003;112(6):845–57 doi 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.