Abstract

Introduction

This research is focused on early detection of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) using a multiscale feature fusion framework, combining biomarkers from memory, vision, and speech regions extracted from magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography images.

Methods

Using 2D gray level co-occurrence matrix (2D-GLCM) texture features, volume, standardized uptake value ratios (SUVR), and obesity from different neuroimaging modalities, the study applies various classifiers, demonstrating a feature importance analysis in each region of interest. The research employs four classifiers, namely linear support vector machine, linear discriminant analysis, logistic regression (LR), and logistic regression with stochastic gradient descent (LRSGD) classifiers, to determine feature importance, leading to subsequent validation using a probabilistic neural network classifier.

Results

The research highlights the critical role of brain texture features, particularly in memory regions, for AD detection. Significant sex-specific differences are observed, with males showing significance in texture features in memory regions, volume in vision regions, and SUVR in speech regions, while females exhibit significance in texture features in memory and speech regions, and SUVR in vision regions. Additionally, the study analyzes how obesity affects features used in AD prediction models, clarifying its effects on speech and vision regions, particularly brain volume.

Conclusion

The findings contribute valuable insights into the effectiveness of feature fusion, sex-specific differences, and the impact of obesity on AD-related biomarkers, paving the way for future research in early AD detection strategies and cognitive impairment classification.

Keywords: Multiscale feature fusion in Alzheimer’s disease, Feature importance analysis and Alzheimer’s disease, Sex differences in Alzheimer’s disease

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) biomarkers now include digital biomarkers like speech characteristics, alongside traditional methods such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis and neuroimaging. Digital biomarkers enable non-invasive, continuous monitoring and early detection of AD [1]. While we focus on imaging due to its accuracy, integrating digital biomarkers can enhance early detection, intervention, and prognosis by providing a comprehensive AD model.

Memory Regions and Their Roles in AD

In this study, extracting and analyzing certain regions of interest (ROI) from medical images is the main focus, along with process simplification and improved feature importance analysis. The two central ROIs in memory regions impacted by Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are the entorhinal cortex and the hippocampal regions. These two brain regions are critical and are frequently the first to show signs of damage [2–4]. The entorhinal cortex is critical in memory and spatial navigation, while the hippocampus is essential for learning and remembering. These regions’ fusion features can be used to provide early AD signs. Furthermore, the accumulation of proteins such as Tau and amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide can be measured in these regions, providing information about how the disease develops [5].

Vision Cortices and Their Roles in AD

AD is distinguished not only by its well-known memory deficits but also by a wide range of visual abnormalities that extend beyond cognitive domains. Deficits in various visual features, including visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, color discrimination, optic flow perception, and visuospatial orientation, have been observed in research [6–8]. These visual abnormalities in AD have sparked research into the visual system’s potential as a source of biomarkers for the disease. Recent research has revealed the prevalence of AD-related disorders in visual pathways ranging from the subcortical to the cortical region. Notably, visual deficits in AD are caused by changes in higher cortical areas, particularly the visual association regions, rather than changes in visual pathways up to the primary visual cortex [9].

While the presence of visual system defects in AD is well recognized, the timing of these impairments in connection to the early stages of the disease remains unknown. More research is needed to thoroughly understand the sensitivity and specificity of visual metrics in detecting early indications of AD. While AD-related disease is evident in both the peripheral and central visual systems of AD patients, the point at which such pathology first manifests in the visual system remains unknown [10]. A thorough examination of visual characteristics in AD patients versus healthy controls revealed substantial changes. Visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, color perception, and visual integration were all significantly poorer in AD patients as compared to healthy controls. When compared to healthy controls, mild AD patients had considerable macular thinning in the central region, whereas moderate AD patients had significant macular thickening in the central region [11].

The prevalence of motion perceptual abnormalities in AD is a well-known fact. However, previous research [12] found that net connectivity in the primary visual cortex (V1) significantly increases during visual motion stimulation in normal control patients but not in those with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or AD. This altered net activity inside V1 could be a critical factor in the motion perception abnormalities observed in MCI and AD.

Although it has received relatively less attention, the existence of visuospatial deficits has long been recognized as a prominent feature of AD over an extended timeframe. Notably, recent advancements in imaging research have confirmed the presence of these visuospatial impairments even during the initial phases of AD, as evidenced by the work of Kim and Lee [13]. Thus, our focus revolves around the brain’s visual regions to ascertain their relationship and significance concerning AD. The critical ROIs include:

Primary visual cortex (V1): Positioned in the occipital lobe at the brain’s posterior, V1 is responsible for the initial processing of visual information. It earns its name, the striate cortex, from its striped appearance. V1 recognizes basic visual features such as edges, lines, and orientations [14].

Secondary visual cortices (V2, V3, V4), middle temporal area (V5): These higher level visual regions continue to process progressively intricate visual information. V2 handles more complex shapes, V3 concentrates on form and motion processing, V4 is engaged in color perception, and V5 (also known as the medial temporal region) specializes in motion perception [14–17].

Figure 1 illustrates a functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain slice highlighting the primary visual centers in the occipital cortex. The figure illustrates the path of visual information from the retinas to the primary visual cortex using different colors for each hemisphere. Figure 2 employs FSL eyes visualization on the standard MRI image, clearly presenting the five regions we aim to extract from the entire brain.

Fig. 1.

The visual pathways from the retina in the eyes to the primary visual cortex at the rear of the brain are shown schematically.

Fig. 2.

Visual cortices V1-V5.

Speech Regions and Their Roles in AD

Many individuals with AD initially speak clearly but encounter difficulties in comprehending and conveying meaningful information [18, 19]. For example, a study by Harasty examined nine cortical areas related to language, such as Broca’s area, Brodmann 22, and angular gyrus. The results revealed significant impacts in most areas for females and males, with the most significant differences in the anterior superior temporal gyri, where females with Alzheimer’s had 59% greater loss in gyral volume than males [20]. Another study conducted by Yang et al. [21] highlighted the notable thinning of the pars triangularis, a part of Broca’s area, in the left hemisphere, accentuating the left hemisphere’s dominance in language function. The study also highlighted notable reductions in cortical thickness in the right hemisphere, specifically in the middle temporal gyrus and medial orbital frontal cortex, highlighting the significance of the medial temporal lobe in memory [21]. Moreover, Deldar et al. [22] highlight the complex interaction between language and working memory in the context of AD and emphasize how language tasks involving working memory engage specific brain systems, highlighting the possible consequences for the language regions afflicted by AD. Thus, our attention is focused on determining how the speech parts of the brain relate to AD. The key ROIs include:

Broca’s area, which includes Brodmann areas 44 and 45, is critical for speech production and regulation, which is necessary for language fluency and articulation [23].

Wernicke’s area, also known as Brodmann area 22, is in the superior temporal gyrus and is essential for language comprehension. Damage in this area causes problems with processing and understanding both spoken and written language [24].

Angular gyrus plays a role in several functions, including language and arithmetic processing [20].

Sex Differences in AD

Recent research has shed light on the significant impact of sex-related differences in the development and progression of AD. Ferretti et al. [25] found that men and women with AD exhibit distinct symptom profiles and rates of cognitive decline. Despite consistent Aβ levels, women experience accelerated brain atrophy during the early stages of the disease. Moreover, different risk factors have differential effects on each sex, emphasizing the need for further investigation into sex-specific distinctions in AD for tailored treatment approaches. Similarly, Contador et al. [26] observed that females with early onset AD (EOAD) demonstrate more pronounced cognitive impairment and broader brain atrophy compared to males. Although slight differences in the thickness of specific brain regions were noted, no significant variances in cognition or hippocampal volume were found. Notably, females with EOAD exhibited higher levels of tau protein in their cerebrospinal fluid, greater cognitive impairment, and a broader atrophy burden compared to male EOAD patients and same-sex healthy controls. The degree of brain atrophy in females was positively correlated with increased cognitive impairment, suggesting sex differences influence the pattern of cognitive decline and disease susceptibility in EOAD. Further investigations by Tsiknia et al. [27] indicate that women on the AD continuum tend to display higher levels of tau pathology compared to men. While plasma p-tau181 levels remain similar between the sexes, women show reduced brain glucose metabolism, increased brain Aβ deposition, raised CSF p-tau181, and accelerated cognitive decline linked to higher baseline plasma p-tau181 levels compared to males. Among individuals with Aβ pathology, women are at a higher risk of developing AD dementia as baseline plasma p-tau181 levels increase.

Methodology

Figure 3 illustrates the block diagram of a comprehensive methodology for early AD detection using the ADNI dataset. It begins with MRI and positron emission tomography (PET) data acquisition, followed by memory, vision, and speech region segmentation. Subsequently, the feature processing pipeline includes feature extraction, feature engineering, and feature fusion. Ultimately, feature importance analysis used LR, LRSGD, linear discriminant analysis (LDA), and linear support vector machine (L-SVM) classifiers.

Fig. 3.

Block diagram.

ADNI Dataset

For early AD detection, data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database was used (www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI). The ADNI was established in 2003 by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), private pharmaceutical companies, and nonprofit organizations. The main objective of the ADNI has been to determine whether serial MRI, PET, other biological markers, clinical evaluation, and neuropsychological testing may be integrated to track the evolution of MCI and early AD [28].

This study involved downloading MRI and PET images from the ADNI database, organized into two groups: MCIs (MCI stable, AD -ve), which included individuals not anticipated to develop AD, and MCIc (MCI conversion, AD +ve), which included individuals expected to develop AD. A total of 82 subjects were included, each with 8 scans in total – 4 MRI scans and 4 PET scans – across four time points: baseline, 6 months, 12 months, and 18 months. Specifically, each subject contributed 4 MRI images and 4 PET images, one from each time point, resulting in 8 images per subject. The study included 46 subjects in the MCIc group and 36 in the MCIs group. To ensure a balanced dataset and avoid bias, we selected 72 subjects – 36 from each group. Additionally, we ensured balance by sex, with 30 males and 30 females, which is important for exploring sex-based differences in MCI progression.

Regarding the time aspect of the scans, we acknowledge that scans taken at different time points (baseline, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months) are likely to differ due to disease progression. However, since the primary goal of our study was to classify subjects into MCI stable versus MCI conversion groups, rather than to track changes over time, we did not explicitly model time as a feature. Instead, we used all available scans (one for each time point) for each subject, treating them as independent feature sets. This approach allowed us to focus on overall subject-level characteristics rather than modeling temporal progression. To ensure that repeated measures (scans from the same subject) did not lead to data leakage or bias, we implemented a subject-based stratification strategy during the train-test-validation split, ensuring that scans from the same subject always remained in the same split (train, validation, or test). This clarifies our approach, which is now detailed in the manuscript.

Segmentation of Memory, Vision, and Speech Regions in MRI and PET Images

Accurate segmentation of ROIs such as memory-related regions (hippocampus and entorhinal cortex), vision-related regions (primary visual cortex [V1], secondary visual cortices [V2, V3, V4], middle temporal area [V5]), and speech-related regions (Broca area [Broca 44, Broca 45], Brodmann 22 area [Wernicke’s area], angular gyrus) in MRI and PET images has a significant impact on understanding and diagnosing neurological diseases. It involves dividing a region into its basic parts. Accurate segmentation is essential for quantitative analysis and learning more about the pathophysiology of these diseases [29, 30]. We used the built-in atlases of the FMRIB Software Library (FSL) to automate the segmentation of imaging data. The extensive toolkit and atlases provided by FSL ensured a precise segmentation process and effective results, making our research analytical process reliable and efficient [31].

Feature Processing Pipeline for Enhanced Feature Importance Analysis

Figure 4 illustrates the feature processing pipeline. The process starts with extracting GLCM, ROI volume, and standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) features. Subsequently, feature engineering is explicitly applied to the GLCM features, consolidating them into a single feature to ensure a balanced scale between features. Finally, the feature fusion process includes the engineered features of GLCM, volume, SUVR, and obesity.

Fig. 4.

Feature processing pipeline.

Feature Extraction

In this study, we extract textural features from 3D MRI images of the memory, vision, and speech regions using the gray level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM). The GLCM method evaluates the relationships between pixel values based on their co-occurrence frequency. Each element in the matrix represents the count of specific pixel pairs appearing in the image. Parameter values like radius, angle, and gray levels significantly influence GLCM computation. The selected parameters in this research include a radius (distance between pixels) of 1, 3, and 5, angles of 0, 45, 90, and 135°, and an analysis of 256 gray levels. The GLCM matrices are calculated for each 2D slice, combined into a single 2D GLCM for the entire ROI by averaging the GLCM matrices across all slices, and analyzed using statistical measures like dissimilarity, correlation, homogeneity, contrast, and angular second moment (ASM) to extract relevant information about texture features.

The contrast, dissimilarity, correlation, homogeneity, and ASM are computed using the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where N is the total number of gray levels within the ROI, and Pij denotes the number of occurrences where a pixel with gray-level i is adjacent to a pixel with gray-level j, given a specific offset d and orientation θ. μi and μj correspond to the mean values across the rows and columns of the GLCM, while σi and σj represent the respective standard deviations.

Furthermore, this study emphasizes the importance of volumetric measures in the speech, visual, and memory regions, especially in the diagnosis and follow-up of neurological diseases such as AD. The volume for each region side was determined by summing up the volumes of all the voxel volume within that region (vr) [31, 32]. This approach aims to quantify and analyze ROI volumes for diagnostic purposes.

Equation (6) represents the volumetric measurement process:

| (6) |

where Volumeregion is the total volume of the specified region, voxel represents individual voxels within the region, and Volumevoxel is the volume associated with each voxel. Additionally, the voxel volume (Volumevoxel) can be expressed as [31, 32].

| (7) |

Moreover, the SUVR, which is a metric that measures the accumulation of a radiotracer in particular brain regions in comparison to a reference region – typically the cerebellum – chosen for its consistency across subjects – is found in this work. It can be calculated by dividing the average uptake in the ROI by that in the cerebellum, as illustrated in Equation (8). Although SUVR only gives a relative measurement and cannot determine exact tau or amyloid levels, it is helpful for monitoring accumulation over time or between patients. As demonstrated by [33], SUVR helps differentiate between MCI, MCI with evidence of amyloid or tau pathology (MCIc), and AD. It also helps identify different phases of AD and other neurological diseases. An increased risk of neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s is correlated with higher levels of tau or amyloid accumulation, as shown by a higher SUVR measurement.

| (8) |

Furthermore, several studies suggest a potential link between obesity and AD through processes such as inflammation and insulin resistance [34–36]. Razay et al. [36] highlight significant associations between AD and obesity, underweight conditions, and abdominal obesity, with logistic regression (LR) analyses emphasizing the role of metabolic risk factors. Additionally, Terzo et al. [35] underscore the correlation between obesity and health risks, particularly AD, stressing the impact of metabolic issues such as insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.

Following the World Health Organization (WHO) classification, overweight in adults is determined based on the body mass index (BMI) as outlined in Table 1 [37].

Table 1.

Overweight determination in adults based on body mass index (BMI)

| Classification | BMI (kg/m2) |

|---|---|

| Underweight | <18.5 |

| Normal range | 18.5–24.9 |

| Overweight | >25.0 |

| Pre-obese | 25.0–29.9 |

| Obese class I | 30.0–34.9 |

| Obese class II | 35.0–39.9 |

| Obese class III | >40.0 |

Feature Engineering For GLCM Texture Features.

Feature engineering is essential for extracting meaningful data representations in machine learning tasks. We use histograms to extract a single feature from each ROI texture feature. The histogram approach involves creating histograms for GLCM features, offering insights into the prevalence and strength of texture patterns. This technique works exceptionally well when the frequency or intensity of the texture pattern and the statistical distribution of GLCM features are essential, like in image classification tasks.

To explain this process in detail, we first determine the range of each GLCM feature (minimum and maximum values) – such as contrast, correlation, and homogeneity – across all ROIs. This range is then used to divide the feature values into discrete bins, with the discretization step (ds) calculated using Equation (9) [38]:

| (9) |

where B is the number of bins. For each original feature value V, we calculate the discrete value DV and assign it to a bin using Equation (10) [38]:

| (10) |

The next step is to calculate the histogram for each feature within the range values. If B bins are used, the resulting histogram for a particular feature will have B values, transforming the original feature with N values into a histogram with B values, where N>B. The B values represent the transformed features, which are more robust and serve as a compact representation of the statistical distribution of the data.

For each GLCM feature extracted from an ROI, we construct individual histograms that represent the statistical distribution of the feature values. These histograms capture the frequency and intensity of texture patterns, reflecting the occurrence and strength of specific texture patterns within the ROI. Once the histograms for each GLCM feature are computed, they are concatenated to form a single, comprehensive histogram feature for each region. This combined histogram effectively encapsulates the most relevant information from the original GLCM features, highlighting the texture patterns significant for our analysis. By emphasizing the distribution of values and capturing the strength of these patterns, the histogram approach is deemed the most effective method for creating a new single texture feature from the major texture features, as previously outlined in our previous work [39].

Feature Fusion.

Several biomarkers acquired from distinct neuroimaging modalities provided complementary data, which was used through a fusion process [40–42]. The derived features from ROIs, such as the standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) from PET images and textural features from segmented MRI images, were integrated to form comprehensive feature vectors. Specifically, the feature vectors combine the following elements:

Memory regions: texture features and volume from the entorhinal cortex and hippocampal regions.

Vision regions: texture features and volume from the primary visual cortex (V1), secondary visual cortices (V2, V3, V4), and middle temporal area (V5).

Speech regions: texture features and volume from Broca’s area, Wernicke’s area, and the angular gyrus.

These features are merged through concatenation, represented mathematically in Equation (9):

where ⊕ denotes the concatenation of the individual feature components. The resulting fusion vectors were then classified using modern techniques, including probabilistic neural network classifiers. This integrated approach enhances overall classification performance by leveraging diverse and complementary data from multiple neuroimaging and biomarker sources.

Feature Importance Analysis.

Diogo et al. [43] employed classifiers selected for their ability to unveil the importance of features and generate probability outputs. In this study, feature importance was determined using a weight-based technique, which evaluates the contribution of each feature based on the weights assigned by the classifiers. The classifiers used were LR, logistic regression with stochastic gradient descent learning (LRSGD), LDA, and L-SVM. Each of these linear classifiers computes feature importance directly from the learned model parameters:

LR: feature importance is derived from the coefficients of the features in the LR equation, which represent their contribution to the log-odds of the prediction [44].

LDA: feature importance is determined from the discriminant weights in the linear discriminant function, which maximize between-class variance while minimizing within-class variance [45].

LRSGD: similar to LR, feature importance is based on the coefficients learned during the stochastic gradient descent optimization process, with larger absolute values indicating higher importance [46].

L-SVM: feature importance is determined by the magnitude of the weights (coefficients) assigned to each feature in the decision function. The SVM aims to maximize the margin between classes, and the weight of each feature can be interpreted as its contribution to that margin [47].

By integrating the outputs from these classifiers, the analysis calculated the feature importance using two methods.

Averaging: computing the mean importance scores across classifiers to provide a consensus measure.

Per classifier: isdentifying the most important features based on their ranks from individual classifiers.

This weight-based method provides a direct and interpretable measure of feature importance, leveraging the unique strengths of each classifier to ensure robustness. Overall feature importance was determined by employing both averaging and top-ranking methods based on the feature importance outputs from each classifier that contributed to the final decision through a voting process, as demonstrated in our previous work [39].

Classification

Weighted voting methods provide a powerful strategy for combining the strengths of individual classifiers to enhance overall predictive performance [48]. In this study, LR, LRSGD, LDA, and L-SVM are used and integrated into our framework [44–46, 49]. The ensemble’s decision-making process benefits from the diverse strengths of each classifier, leading to a more accurate classification model. The targeted classes are MCIs (AD -ve), patients not expected to develop AD, and MCIc (AD +ve), patients predicted to develop AD.

Data were initially split into training (70%), testing (20%), and validation (10%) sets in a stratified manner. For hyperparameter tuning, 5-fold cross-validation was performed within the training set, allowing for the selection of optimal parameters while minimizing the risk of overfitting. After model training and hyperparameter optimization, the 10% validation set was used to evaluate the final model’s performance, providing an independent assessment before testing on the hold-out test set. Classifiers demonstrated strong performance across the test set, with accuracy ranging from 84% to 99%. SVM achieved the highest accuracy, while LDA, LR, and SGD models consistently performed above 84%. F1 scores varied from 0.74 to 0.99, with precision and recall exceeding 0.69 for all models, indicating robust predictive capabilities. These results confirm the classifiers’ suitability for feature importance analysis in distinguishing between MCIc (AD +ve) and MCIs (AD −ve).

Data leakage was avoided by implementing a subject-based splitting strategy before feature scaling and GridSearchCV. Specifically, the dataset was split into training, testing, and validation sets based on subject IDs, ensuring that all scans from a given patient (across the 4-time points: baseline, 6 months, 12 months, and 18 months) were assigned exclusively to one of the splits. This approach prevented any overlap of data from the same subject across different sets, eliminating the risk of data leakage and ensuring that model selection and tuning were not influenced by information from the test or validation sets. Overall, these results highlight the strong performance of the SVM model and the acceptable performance of LDA, LR, and SGD models, supporting the relevance of feature importance analysis in identifying individuals likely to develop AD.

Results

Feature Importance Analysis (per Classifier): Memory, Vision, and Speech Regions – All Patients

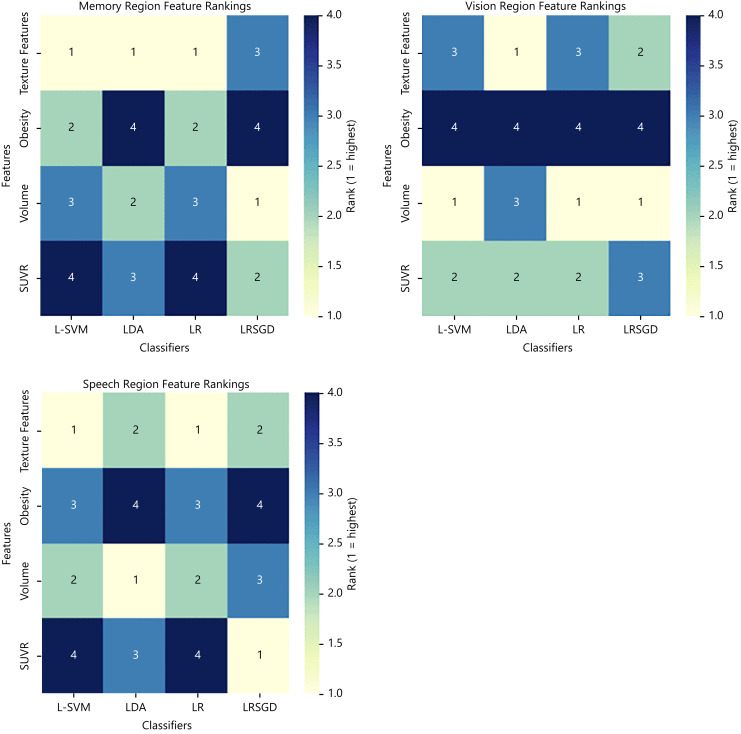

The feature ranking analysis across classifiers (L-SVM, LDA, LR, and LRSGD) reveals distinct prioritization patterns across memory, vision, and speech regions. As illustrated in Figure 5, L-SVM and LR consistently rank features identically in all regions, prioritizing texture features in memory and speech, and volume in vision, indicating their similar approach to feature evaluation. LDA and LRSGD, however, show more variability. In memory, LDA aligns partially with L-SVM and LR by prioritizing texture features but ranks obesity last, while LRSGD uniquely ranks volume highest. In vision, LDA prioritizes texture features, diverging from L-SVM, LR, and LRSGD, which all rank volume first. For Speech, LDA highlights volume as most important, while LRSGD emphasizes SUVR. These differences reflect the varied sensitivities and strategies of the classifiers in evaluating feature importance.

Fig. 5.

Feature importance analysis by classifier for memory, vision, and speech regions. The figure shows feature ranking patterns for L-SVM, LDA, LR, and LRSGD.

Feature Importance Analysis (Averaged across Classifiers): Memory, Vision, and Speech Regions – All Patients

The significant role of texture features in the memory and vision regions, as well as early and pronounced structural changes caused by AD, is a consistent observation in both clinical and research findings [39]. These findings consistently show that these regions are among the first to be affected by the disease. In contrast, the speech regions undergo less structural change in the early stages, which means that texture features are less critical for these areas.

Figure 6 illustrates the feature importance analysis for all MCIc and MCIs patients. Among the memory regions, texture features exhibited the highest importance (45.0%), emphasizing the role of brain texture features as a sensitive marker for early classification. This finding aligns with previous studies by [50, 51], where they demonstrated that texture features extracted from the entorhinal cortex (one of the memory regions) significantly outperformed other methods like volumetry in terms of predictive accuracy for AD detection. Additionally, changes in brain volume (30.9%) suggested a strong association with disease classification; however, the impact of SUVR (3.0%) and obesity (21.2%) is consistent with earlier research, which found that a higher late-life BMI was linked to larger hippocampal volumes and a decrease in Aβ concentration in the right hippocampal.

Fig. 6.

Memory, vision, speech feature importance analysis. Texture features are the most important in the memory and vision regions, while they are the least significant in the speech regions.

In the context of the vision regions, SUVR (63.8%) emerged as the most significant feature, highlighting the strong association between amyloid pathology and visual impairments. In contrast, texture features (12.7%), volume (22.7%), and obesity (0.7%) played comparatively minor roles. For speech biomarkers, texture features (46.1%) again showed the highest importance, emphasizing the significance of textural features of speech regions in disease classification. Moreover, changes in brain volume (23.2%) and SUVR (27.3%) reflected the impact of structural and amyloid changes on speech impairments, while the influence of obesity (3.3%) was relatively minor. This supports earlier research, which indicates that patients with AD are likely to have visual problems that have not been detected due to the developing dementia [52].

In the speech regions, texture features were shown to be the most significant features, accounting for 46.1% of the total. Although volume was substantial (23.2%), it had somewhat less influence than texture features, suggesting that the overall size of the brain areas related to speech is essential. SUVR came in second (27.3%), highlighting its significance in understanding the changes in speech regions. On the other hand, obesity seems to have the least effect, accounting for only 3.3% of the features considered, suggesting a negligible correlation in the context of speech regions.

Sex-Based Differences Results in AD

Memory, Vision, and Speech Regions Feature Importance Analysis: Females

Figure 7 illustrates that SUVR might be a more sensitive and significant indicator of Alzheimer’s pathology in the vision region for females, as women may have a higher amyloid burden than men at similar stages of the disease. It shows the analysis of a few extracted features from memory, vision, and speech regions for females. In the memory regions, females showed a significantly higher emphasis on texture features (73.7%), with a slightly lower focus on volume (21.6%) and notably lower SUVR (4.1%). This suggests that while volume features are important for Alzheimer’s detection in females, texture features play a more dominant role. When examining vision regions, females displayed greater significance for SUVR features (44.9%), indicating a higher amyloid burden. In the speech regions, females adopted a more texture-driven approach (39.1%), with a lower emphasis on volume and SUVR (19.3% and 35.2%, respectively). Additionally, females showed relatively lower levels of obesity effect, with the highest percentage recorded in the vision regions at 10.5%, followed by 6.3% in the speech regions and merely 0.6% in the memory regions.

Fig. 7.

Memory, vision, speech feature importance analysis – females. Texture features are the most important in the memory and speech regions, while SUVR is the most significant in the vision regions for females.

Memory, Vision, and Speech Regions Feature Importance: Males

Hormonal changes after menopause, combined with different patterns of amyloid plaque deposition in males and females, can lead to distinct brain changes between the sexes [53]. Due to hormonal influences, genetic factors, and other sex-specific elements, females may experience unique structural changes in the speech regions. These changes lead to microstructural changes often more effectively captured by texture features, making them particularly significant in females.

Figure 8 illustrates the analysis of a few extracted features from memory, vision, and speech regions for males. Regarding memory regions, males predominantly emphasized texture features, accounting for 86.2% of the total, followed by volume (6.7%) and SUVR (5.8%). This suggests that textural features could hold importance for Alzheimer’s patients among males. Furthermore, when examining vision regions, males emphasized volume more (55.8%) than females. Regarding speech regions, males showed a more significance on SUVR feature 40.8%. In males, the data indicate that obesity has a moderate effect across the three regions (memory, vision, and speech), with the highest percentage observed in the speech regions (26.8%), followed by 9.3% in the vision regions and 1.3% in the memory regions.

Fig. 8.

Memory, vision, speech feature importance analysis – males. Texture features are the most important in the memory regions, volume is the most significant in the vision regions, and SUVR is the most significant in the speech regions for males.

Obesity Impact on Brain-Extracted Features Using Linear Regression Analysis

We also used the linear regression analysis technique to investigate how obesity affects various brain-extracted features obtained from different ROIs (memory, vision, and speech).

These findings allow us to identify the following:

The features that are statistically significantly associated with obesity. It helps determine which brain features are affected by whether someone is obese.

The magnitude of the relation: In linear regression, a coefficient signifies the extent of the relationship between obesity and brain features. A higher coefficient implies a more pronounced association, whereas a lower one suggests a weaker connection.

The direction of the relationship: it helps determine whether obesity and brain features are positively or negatively correlated.

Figure 9 illustrates that obesity affects speech and vision more than the memory regions. Furthermore, its primary influence is on brain volume, followed by texture changes and then SUVR. These findings were derived from a linear regression analysis, with obesity as the independent variable and other features (regions’ volume, texture, and SUVR) as dependents.

Fig. 9.

Linear regression analysis: used to find how the independent variable (obesity status) affects various brain-extracted features obtained from different ROIs.

Discussion

Feature Importance Analysis (All Patients)

The examination of feature importance across all patients highlights critical insights. In memory regions, the importance of brain texture features stands out as crucial for the early detection of AD. Furthermore, the identified correlations among changes in brain volume, obesity, and cognitive impairment provide robust support for established research on BMI, hippocampus sizes, and Aβ concentration. However, the SUVR precedes vision regions as the most significant feature, indicating a robust link between amyloid concentration and visual impairments. Whereas, in speech regions, the discussion underscores the critical role of texture features in disease classification, emphasizing their vital contribution to this domain.

The results emphasize the critical role of brain texture features, particularly in memory regions, aligning with earlier studies emphasizing their superior predictive accuracy for early AD detection. Additionally, the correlation among changes in brain volume (memory regions), obesity, and cognitive impairment supports earlier findings emphasizing the relationship between increased late-life BMI, increased hippocampus sizes, and decreased Aβ concentration. In vision regions, SUVR is the most significant feature, indicating a strong association between amyloid concentration and visual impairments. In contrast, in the speech regions, texture features demonstrate the highest importance, highlighting their important role in classifying the disease using those regions.

This analysis used an averaged approach across all classifiers to assess overall feature importance. The ranking patterns across classifiers (L-SVM, LDA, LR, and LRSGD) reveal that L-SVM and LR consistently rank features similarly, prioritizing texture features in memory and speech, and volume in vision. LDA and LRSGD show more variability, with LDA prioritizing texture features in memory and vision, and LRSGD ranking volume highest in memory and SUVR in speech. These differences highlight the classifiers’ varying strategies in evaluating feature importance.

Feature Importance Analysis for Males and Females

Different patterns emerge when the feature importance analysis for males and females is examined. Both females and males emphasize the importance of textural elements in memory regions. However, in visual regions, there is a clear sex difference: males highlight volume, while females prioritize SUVR features. This raises the possibility of sex-related variations in certain visual processing regions. Furthermore, texture features are more significant for both females and males in speech regions. However, the second most crucial feature differs by sex: SUVR is substantial for females, while brain volume is significant for males. This emphasizes how critical such features are for classifying disorders within speech regions. Regarding the effects of obesity, we find sex-specific differences, with males often showing higher percentages of affected regions than females.

In memory regions, the results indicated that texture features were more significant in males, whereas volume measures were more significant in females. This suggests possible sex differences in the relevance of textural features for Alzheimer’s patients. In vision regions, texture features were more important in females, while volume measures were more significant in males, indicating possible differences in brain regions related to visual processing. In speech regions, males and females had their features prioritized differently, with males demonstrating a more balanced distribution and females showing greater significance for texture features. Additionally, the relationship between obesity and AD varied across sexes and regions, with males generally showing a higher percentage of affection than females.

Obesity Impact on Various Extracted Features from Memory, Vision, and Speech Regions

The research yielded valuable insights into the impact of obesity on various extracted features from different ROIs, such as memory, vision, and speech. The results show that obesity significantly affects speech and vision more than memory regions, primarily influencing brain volume, followed by texture changes and SUVR. These findings were obtained through a comprehensive linear regression analysis, with obesity as the independent variable and other features as dependent variables.

Study Limitation

One limitation of our study is the sample size, which may not represent the broader population, especially for individuals with MCIs and those with mild cognitive impairment converters (MCIc). This limitation can affect the generalizability of our findings to more diverse populations.

Conclusion

In this research, we aimed to explore the early detection of AD through a multiscale feature fusion framework. By fusing biomarkers from memory, vision, and speech regions and leveraging advanced neuroimaging modalities, we aimed to uncover significant patterns and insights that could aid in the early diagnosis of AD. Using texture features, volumetric data, SUVR, and obesity metrics, we applied multiple classifiers – linear support vector machine (L-SVM), linear discriminant analysis (LDA), LR, and LRSGD – to analyze the importance of different features within each ROI. A probabilistic neural network classifier was then used to validate our findings.

Using histograms for feature engineering proved crucial in extracting meaningful data from texture features within each ROI. This method effectively captured the statistical distribution of texture features, enhancing our models’ accuracy and reliability. The balanced approach of treating texture features equally with volume and obesity metrics led to a more comprehensive feature fusion.

Our feature importance analysis highlighted the critical role of texture features, especially in memory regions, and underscored the significant impact of obesity on various features across different ROIs. These findings emphasize the importance of considering obesity metrics in early AD detection.

Differences in feature importance between males and females could have significant implications for the diagnosis and treatment of AD. These differences align with existing clinical and research evidence, highlighting the need for sex-specific approaches in the diagnosis and management of AD. Understanding these gender-specific differences could lead to more accurate and personalized diagnostic tools and treatment strategies.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge that the data used in this study were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI). As such, the investigators within ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in the analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators is available at www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI/Collaboration/ADNI_Manuscript_Citations.pdf. In addition, this work was supported by funds from the Faculty Research and Creative Activities Award at Western Michigan University.

Statement of Ethics

Western Michigan University Institutional Review Board (IRB) granted this project an exempt status (Reference No. 22-10-03). It was determined that written informed consent was not required because the study did not involve human subjects or collect any personally identifiable information.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The Faculty Research and Creative Activities Award Funds at Western Michigan University partially supported this work in 2023.

Author Contributions

Aya Hassouneh: literature review, conceptualization, implementation of research methods, and implementation of experimental work, writing, and reviewing, manuscript writing and leading the effort, and project administration. Alessander Danna-dos-Santos: conceptualization, discussion, reviewing, and editing. Saad Shebrain: discussion, reviewing, and editing. Bradley Bazuin: editing. Ikhlas Abdel-Qader: project supervisor, conceptualization, research methods, experimental work design, discussion, reviewing, and editing.

Funding Statement

The Faculty Research and Creative Activities Award Funds at Western Michigan University partially supported this work in 2023.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI is a global research effort that collects, validates, and distributes data on AD, making it a crucial resource for our research. As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and provided data but did not participate in the analysis or writing of this report.

The data used in this study cannot be publicly disclosed due to the ADNI Data Use Agreement Policy. However, interested parties may obtain it through ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu). A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wpcontent/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf.

References

- 1. Tröger J, Baykara E, Zhao J, Ter Huurne D, Possemis N, Mallick E, et al. Validation of the remote automated ki: e speech biomarker for cognition in mild cognitive impairment: Verification and validation following DiME V3 Framework. Digit Biomark. 2022;6(3):107–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ahmad F, Zulifqar H, Malik T. Classification of Alzheimer disease among susceptible brain regions. Int J Imaging Syst Technol. 2019;29(3):222–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Braak H, Braak E. Evolution of the neuropathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 1996;165(S165):3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ausó E, Gómez-Vicente V, Esquiva G. Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease early diagnosis. J Pers Med. 2020;10(3):114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jorge L, Canário N, Martins R, Santiago B, Santana I, Quental H, et al. The Retinal Inner Plexiform Synaptic Layer Mirrors Grey Matter Thickness of Primary Visual Cortex with Increased Amyloid β Load in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. Neural Plast. 2020;2020:8826087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lim JKH, Li QX, He Z, Vingrys AJ, Wong VHY, Currier N, et al. The eye as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taylor JP, Firbank MJ, He J, Barnett N, Pearce S, Livingstone A, et al. Visual cortex in dementia with Lewy bodies: magnetic resonance imaging study. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(6):491–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yamasaki T, Horie S, Muranaka H, Kaseda Y, Mimori Y, Tobimatsu S. Relevance of in vivo neurophysiological biomarkers for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;31(Suppl 3):S137–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murphy C. Olfactory and other sensory impairments in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(1):11–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Salobrar-García E, de Hoz R, Ramírez AI, López-Cuenca I, Rojas P, Vazirani R, et al. Changes in visual function and retinal structure in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0220535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yamasaki T, Aso T, Kaseda Y, Mimori Y, Doi H, Matsuoka N, et al. Decreased stimulus-driven connectivity of the primary visual cortex during visual motion stimulation in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: An fMRI study. Neurosci Lett. 2019;711:134402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim NG, Lee HW. Stereoscopic depth perception and visuospatial dysfunction in alzheimer’s disease. In: Healthcare. MDPI; 2021. p. 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Andreatta RD. The Visual System. Neurosci Fundament Commun Sci Disord. 2022;393. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roe AW, Ts’o DY. Visual topography in primate V2: multiple representation across functional stripes. J Neurosci. 1995;15(5 Pt 2):3689–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zeki S. The representation of colours in the cerebral cortex. Nature. 1980;284(5755):412–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Newsome WT, Pare EB. A selective impairment of motion perception following lesions of the middle temporal visual area (MT). J Neurosci. 1988;8(6):2201–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Appell J, Kertesz A, Fisman M. A study of language functioning in Alzheimer patients. Brain Lang. 1982;17(1):73–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hart S. Language and dementia: A review. Psychol Med. 1988;18(1):99–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harasty JA, Halliday GM, Kril JJ, Code C. Specific temporoparietal gyral atrophy reflects the pattern of language dissolution in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 1999;122 (Pt 4)(4):675–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang H, Xu H, Li Q, Jin Y, Jiang W, Wang J, et al. Study of brain morphology change in Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment compared with normal controls. Gen Psychiatr. 2019;32(2):e100005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deldar Z, Gevers-Montoro C, Khatibi A, Ghazi-Saidi L. The interaction between language and working memory: a systematic review of fMRI studies in the past two decades. AIMS Neurosci. 2021;8(1):1–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ardila A, Bernal B, Rosselli M. How localized are language brain areas? A review of Brodmann areas involvement in oral language. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2016;31(1):112–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ardila A, Bernal B, Rosselli M. The role of Wernicke’s area in language comprehension. Psychol Neurosci. 2016;9(3):340–343. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferretti MT, Iulita MF, Cavedo E, Chiesa PA, Schumacher Dimech A, Santuccione Chadha A, et al. Sex differences in Alzheimer disease: the gateway to precision medicine. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(8):457–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Contador J, Pérez‐Millan A, Guillen N, Sarto J, Tort‐Merino A, Balasa M, et al. Sex differences in early‐onset Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29(12):3623–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tsiknia AA, Edland SD, Sundermann EE, Reas ET, Brewer JB, Galasko D, et al. Sex differences in plasma p-tau181 associations with Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers, cognitive decline, and clinical progression. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(10):4314–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mueller SG, Weiner MW, Thal LJ, Petersen RC, Jack CR, Jagust W, et al. Ways toward an early diagnosis in Alzheimer’s disease: the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Alzheimers Dement. 2005;1(1):55–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tsai C, Manjunath BS, Jagadeesan R. Automated segmentation of brain MR images. Pattern Recognit. 1995;28(12):1825–37. [Google Scholar]

- 30. E Woods R, C Gonzalez R. Digital image processing. Pearson Education Ltd; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bayat PD, Ghanbari A, Sohouli P, Amiri S, Sari-Aslani P. Correlation of skull size and brain volume, with age, weight, height and body mass index of Arak Medical Sciences students. Int J Morphol. 2012;30(1):157–61. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mulder MJ, Keuken MC, Bazin PL, Alkemade A, Forstmann BU. Size and shape matter: the impact of voxel geometry on the identification of small nuclei. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0215382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Barthélemy NR, Horie K, Sato C, Bateman RJ. Blood plasma phosphorylated-tau isoforms track CNS change in Alzheimer’s disease. J Exp Med. 2020;217(11):e20200861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Picone P, Di Carlo M, Nuzzo D. Obesity and Alzheimer’s disease: Molecular bases. Eur J Neurosci. 2020;52(8):3944–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Terzo S, Amato A, Mulè F. From obesity to Alzheimer’s disease through insulin resistance. J Diabetes Complications. 2021;35(11):108026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Razay G, Vreugdenhil A, Wilcock G. Obesity, abdominal obesity and Alzheimer disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(2):173–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weir CB, Jan A. BMI Classification Percentile And Cut Off Points. 2023 Jun 26. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zdravevski E, Lameski P, Mingov R, Kulakov A, Gjorgjevikj D. Robust histogram-based feature engineering of time series data. In: 2015 Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems (FedCSIS) IEEE; 2015. p. 381–8. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hassouneh A, Bazuin B, Danna-dos-Santos A, Acar I, Abdel-Qader I, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Feature Importance Analysis and Machine Learning for Alzheimer’s Disease Early Detection: Feature Fusion of the Hippocampus, Entorhinal Cortex, and Standardized Uptake Value Ratio. Digit Biomark. 2024;8(1):59–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mishra A, Bhateja V, Gupta A, Mishra A, Satapathy SC. Feature fusion and classification of EEG/EOG signals. Soft Comput Signal Proces Proceed ICSCSP. 2018;1:793–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shukla A, Tiwari R, Tiwari S. Review on alzheimer disease detection methods: Automatic pipelines and machine learning techniques. Sci. 2023;5(1):13. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Villa C, Lavitrano M, Salvatore E, Combi R. Molecular and imaging biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease: a focus on recent insights. J Pers Med. 2020;10(3):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Diogo VS, Ferreira HA, Prata D; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease using machine learning: a multi-diagnostic, generalizable approach. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2022;14(1):107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hosmer DW Jr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. John Wiley and Sons. Vol. 398; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Balakrishnama S, Ganapathiraju A. Linear discriminant analysis-a brief tutorial. Institute Sig inform Process. 1998;18:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bottou L. Large-scale machine learning with stochastic gradient descent. In: Proceedings of COMPSTAT’2010: 19th International Conference on Computational StatisticsParis France, August 22-27, 2010 Keynote, Invited and Contributed Papers. Springer; 2010. p. 177–86. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Guyon I, Weston J, Barnhill S, Vapnik V. Gene selection for cancer classification using support vector machines. Mach Learn. 2002;46(1/3):389–422. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tharwat A. Classification assessment methods. Applied computing and informatics. 2021;17(1):168–92. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cortes C, Vapnik V. Support-vector networks. Mach Learn. 1995;20(3):273–97. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sørensen L, Igel C, Liv Hansen N, Osler M, Lauritzen M, Rostrup E, et al. Early detection of Alzheimer’s disease using M RI hippocampal texture. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37(3):1148–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Leandrou S, Lamnisos D, Mamais I, Kyriacou PA, Pattichis CS, Alzheimer’s Disease and Neuroimaging Initiative . Assessment of Alzheimer’s disease based on texture analysis of the entorhinal cortex. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Armstrong RA. Alzheimer’s disease and the eye. J Optom. 2009;2(3):103–11. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mosconi L, Berti V, Dyke J, Schelbaum E, Jett S, Loughlin L, et al. Menopause impacts human brain structure, connectivity, energy metabolism, and amyloid-beta deposition. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):10867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI is a global research effort that collects, validates, and distributes data on AD, making it a crucial resource for our research. As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and provided data but did not participate in the analysis or writing of this report.

The data used in this study cannot be publicly disclosed due to the ADNI Data Use Agreement Policy. However, interested parties may obtain it through ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu). A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wpcontent/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf.