Abstract

Advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) poses treatment challenges, especially where access to multi-kinase inhibitors and ICIs is limited by high costs and lack of insurance. This study evaluates the effectiveness of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) plus platinum-based chemotherapy as an alternative systemic treatment for advanced HCC. A retrospective analysis of advanced HCC patients treated with 5-FU plus platinum-based chemotherapy was conducted. The Kaplan-Meier method determined median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). From April 2009 to October 2023, 48 patients with advanced HCC were included in the study. Nearly all patients (97.9%) had extrahepatic metastasis and stable liver function, with three-quarters previously treated with sorafenib. At a median follow-up of 7.8 months, the median PFS was 4.2 months (95% CI, 1.3–7.1), and the median OS was 8.2 months (95% CI, 2.5–13.9). A high pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (≥ 3.0) adversely affected both PFS (HR = 1.79; 95% CI, 0.99–3.25; p = 0.034) and OS (HR = 2.02; 95% CI, 1.10–3.69; p = 0.011). Hematologic toxicities related to the treatment were substantial, with 62.5% of patients experiencing grade 3 or 4 events, primarily neutropenia, which affected 60.4% of them. Our findings suggest that 5-FU combined with platinum-based chemotherapy is a viable, cost-effective alternative for advanced HCC treatment in resource-limited settings, particularly compared to ICIs and multi-kinase inhibitors, with significant implications for developing countries.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-86523-9.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Cytotoxic chemotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, Cisplatin

Subject terms: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Chemotherapy, Cancer, Medical research, Oncology

Introduction

The treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has made significant progress with the introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)1,2. In the IMbrave-150 trial, atezolizumab plus bevacizumab demonstrated an improvement in overall survival (OS) with a hazard ratio of 0.58 (95% CI 0.42–0.79) compared to sorafenib in patients with untreated HCC2. Similarly, trimelimumab plus durvalumab, in the HYMALAYA study, reported an extension in OS compared to sorafenib, paralleling the findings of the IMbrave-150 trial1. Consequently, based on these findings, ICIs have now become the standard of treatment for advanced HCC, replacing sorafenib3,4.

Despite these advancements, the objective response rates in these studies were relatively low, at 27.3% and 20.1%, respectively, and the median progression-free survival (PFS) was only 6.8 and 5.4 months. These findings highlight that a subset of patients derives limited benefit from ICIs and requires alternative therapeutic strategies1,2. Recently, efforts to enhance the antitumor efficacy of ICIs, such as combining ICIs with trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE), have been explored5. Simultaneously, significant efforts are underway to identify reliable predictive and prognostic biomarkers for the efficacy of ICIs6. Beyond the relatively limited benefits of ICIs, immune-related toxicities, such as peripheral neuropathy or hearing loss, may become intolerable, requiring adjustments to the treatment strategy7,8. For patients who fail to respond to ICIs, subsequent treatment often involves the use of multi-kinase inhibitors (MKIs), with the sequential administration of agents such as sorafenib, axitinib, and cabozantinib being a common approach. However, in real-world settings, this strategy can impose substantial financial burdens on patients9.

In South Korea, where the public health insurance system is well established, covering over 95% of the population, and many parts of severe disease treatments like cancer receive insurance benefits, the use of MKIs as subsequent treatments after ICIs is still not covered, leading to non-medical considerations in treatment decisions. According to World Bank data, Korea’s gross national income (GNI) per capita stands at $30,000. It is assumed that the difficulties observed in Korea might also be prevalent in many African and Asian countries where the GNI per capita is less than $10,00010.

Cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), cisplatin, and anthracycline, despite a decline in interest in the era of targeted therapy and immunotherapy compared to the past, are still effectively used in treating various solid cancers and are relatively inexpensive11,12. In HCC, the combination treatment of 5-FU, cisplatin, and epirubicin (ECF) was used prior to the advent of sorafenib11. Therefore, paradoxically, in environments where the use of ICIs or MKIs is challenging, it is necessary to reassess the effectiveness and limitations of traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy in the era of ICIs and MKIs.

This study is designed to investigate the oncologic outcomes, including both efficacy and adverse events, of using 5-FU, cisplatin, and anthracycline in the treatment of advanced HCC, and aims to explore potential approaches for applying cytotoxic chemotherapy in this context.

Results

Patients characteristics

From April 1, 2009, through October 31, 2023, a total of 48 patients were qualified for inclusion in this study. The clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. Median age was 55 years (range, 35–84) and 37 patients (77.1%) were male. Thirty-eight patients (79.2%) underwent prior TACE for primary tumor control and three-quarter patients were previously treated with sorafenib. The majority of patients (87.5%) had hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, and most (97.9%) exhibited stable liver function, reflected by a Child-Pugh Score (CPS) of 5 or 6. Nearly all patients (97.9%) presented with extrahepatic metastasis, predominantly in the lungs, followed by metastasis to bone, distant lymph nodes, and the peritoneum. Approximately half of the patients displayed elevated serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) levels, exceeding 400 ng/mL.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics. ECF, 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, and epirubicin; TACE, trans-arterial chemoembolization; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; MKIs, multi-kinase inhibitors; HBV, Hepatitis B virus; HCV, Hepatitis C virus.

| Variables | ECF chemotherapy (n = 48) |

|---|---|

| Age, Median (Range) | 55 (35–84) |

|

Gender, n (%) Male Female |

37 (77.1) 11 (22.9) |

|

Previous local treatment, n (%) Surgery TACE Radiotherapy RFA |

23 (47.9) 38 (79.2) 27 (56.2) 11 (22.9) |

|

Prior systemic therapy, n (%) None Sorafenib Other oral MKIs Regorafenib Cabozantinib Lenvatinib Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

7 (14.6) 36 (75.0) 14 (29.2) 11 (22.9) 4 (8.3) 3 (6.2) 10 (20.8) |

|

Prior systemic therapy lines, n (%) None or one Two or more |

36 (75.0) 12 (25.0) |

|

Etiology, n (%) HBV HCV Others |

42 (87.5) 1 (2.1) 6 (12.5) |

|

Child-Pugh Score, n (%) A (5–6) B (7) |

47 (97.9) 1 (2.1) |

|

Vascular invasion, n (%) Yes No |

7 (14.6) 41 (85.4) |

|

Extrahepatic spread, n (%) Yes No |

47 (97.9) 1 (2.1) |

|

Number of organs involved, n (%) 0–1 ≥ 2 |

23 (47.9) 25 (52.1) |

|

Site of metastatic lesions, n (%) Lung Distant lymph node Bone Peritoneum |

37 (77.1) 14 (29.2) 15 (31.2) 10 (20.8) |

|

Baseline α-fetoprotein, n (%) < 400 ng/mL ≥ 400 ng/mL |

25 (52.1) 23 (47.9) |

Chemotherapy dose adjustments

A summary of treatment dose modifications is listed in Table S1. The median duration of the ECF treatment was 3.9 months (interquartile ranges (IQR), 1.8–6.8) and the median number of cycles was four (IQR, 2–6). The median relative dose intensity (RDI) was 0.82 (IQR, 0.68–0.88), with no significant difference between cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients, and 29 patients (60.4%) received less than 85% of the RDI. The majority of patients (81.3%) had a dose reduction in the first 2 cycles of treatment. At the end of the follow-up period, all patients had discontinued planned treatment because of disease progression (37 patients, 77.1%), unacceptable adverse events (9 patients, 18.8%), or patient’s refusal (2 patients, 4.1%).

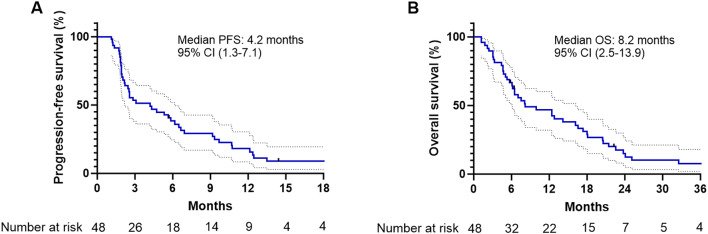

Treatment outcomes

The median follow-up time for all patients was 7.8 months (95% CI, 5.8–16.2). Disease progression and death occurred in 45 patients (93.8%) and 44 patients (91.7%), respectively. The median PFS was 4.2 months (95% CI, 1.3–7.1), and the 3-months and 6-months PFS rates were 53.3% (95% CI, 38.2–66.3%) and 38.3% (95% CI, 24.6–51.8%), respectively (Fig. 1A; Table 2). The median OS was 8.2 months (95% CI, 2.5–13.9), and the estimated OS rates were 66.7% (95% CI, 51.5–78.1%) at 6 months and 46.8% (95% CI, 32.1–60.2%) at 1 year (Fig. 1B; Table 2). Effectiveness outcomes are summarized in Table 2. The response evaluation indicated a partial response in 7 patients (14.6%), stable disease in 22 patients (45.8%), and progressive disease in 19 patients (39.6%). The objective response rate and disease control rate were 14.6% and 60.4%, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) in patients treated with ECF chemotherapy.

Table 2.

Efficacy outcomes. ECF, 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, and epirubicin; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival.

| ECF (n = 48) | |

|---|---|

| Best response | |

| Complete response | 0 |

| Partial response | 7 (14.6%) |

| Stable disease | 22 (45.8%) |

| Progressive disease | 19 (39.6%) |

| Objective response rate | 7 (14.6%) |

| Disease control rate | 29 (60.4%) |

| Median PFS, months [95% CI] | 4.2 [1.3–7.1] |

| 6-month PFS, % [95% CI] | 38.3 [24.6–51.8] |

| Median OS, months [95% CI] | 8.2 [2.5–13.9] |

| 1-year OS, % [95% CI] | 46.8 [32.1–60.2] |

Out of 48 patients, 39 (81.2%) had received at least one MKI treatment, achieving a median PFS of 2.8 months (95% CI, 2.0–3.7) and a median OS of 7.6 months (95% CI, 3.5–11.6). The objective response rate was 7.7%, and the disease control rate reached 56.4%. In the group of 10 patients (20.8%) with prior ICI exposure, the median PFS was 1.8 months (95% CI, 0.6–3.1) and the median OS was 5.7 months (95% CI, 1.7–9.6). Objective response and disease control rates for this subgroup were 10.0% and 40.0%, respectively. Of these 10 patients, 8 had undergone at least one prior MKI therapy, and 6 had received atezolizumab plus bevacizumab as part of their first-line treatment.

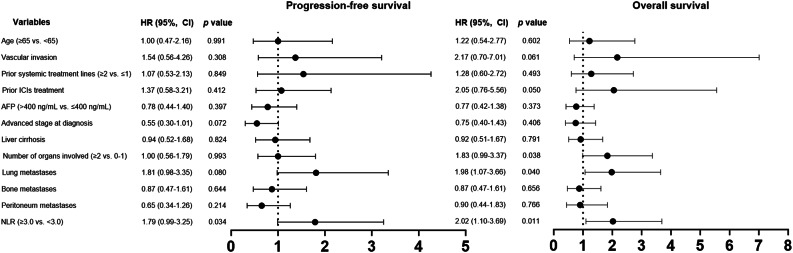

Analysis of prognostic factors

Subgroup analyses of PFS indicated that hazard ratios estimates were significantly increased in the subgroups of patients with high pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) ≥ 3.0 (vs. NLR < 3.0), with median PFS of 4.2 months in the high NLR group and 5.6 months in the low NLR group (HR = 1.79; 95% CI, 0.99–3.25; p = 0.034, Table 3). Patients with lung metastases exhibited a trend toward worse PFS compared to those without lung metastases, though this difference was not statistically significant. The median PFS was 2.6 months for patients with lung metastases and 8.2 months for those without (HR = 1.81; 95% CI, 0.98–3.35; p = 0.080). Analysis revealed no substantial correlation between PFS and other clinical parameters. A higher NLR was also associated with reduced survival outcome with median OS of 7.6 months in the high NLR group and 18.0 months in the low NLR group (HR = 2.02; 95% CI, 1.10–3.69; p = 0.011, Table 3). Additionally, a greater number of metastatic organs (≥ 2 vs. 0–1) and the presence of lung metastases were indicators of poorer OS outcomes. Figure 2 provides a forest plot that delineates the univariate analysis results for PFS and OS across respective subgroups.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of the clinical factors for progression-free survival or overall survival in patients with advanced HCC who received ECF chemotherapy. ECF, 5-fluorouracil cisplatin, and epirubicin; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; ICIs, immune checkpoint inhibitors; AFP, α-fetoprotein; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

| Variables | PFS | OS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age (≥ 65 vs. <65 years) | 1.00 (0.47–2.16) | 0.991 | 1.22 (0.54–2.77) | 0.602 |

| Vascular invasion | 1.54 (0.56–4.26) | 0.308 | 2.17 (0.70–7.01) | 0.061 |

| Prior treatment lines (≥ 2 vs. ≤1) | 1.07 (0.53–2.13) | 0.849 | 1.28 (0.60–2.72) | 0.493 |

| Prior ICIs treatment | 1.37 (0.58–3.21) | 0.412 | 2.05 (0.76–5.56) | 0.050 |

| AFP (> 400 ng/mL vs. ≤400 ng/mL) | 0.78 (0.44–1.40) | 0.397 | 0.77 (0.42–1.38) | 0.373 |

| Advanced stage at diagnosis | 0.55 (0.30–1.01) | 0.072 | 0.75 (0.40–1.43) | 0.406 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 0.94 (0.52–1.68) | 0.824 | 0.92 (0.51–1.67) | 0.791 |

| No. of organ involved (≥ 2 vs. 0–1) | 1.00 (0.56–1.79) | 0.993 | 1.83 (0.99–3.37) | 0.038 |

| Lung metastases | 1.81 (0.98–3.35) | 0.080 | 1.98 (1.07–3.66) | 0.040 |

| Bone metastases | 0.87 (0.47–1.61) | 0.644 | 0.87 (0.47–1.61) | 0.656 |

| Peritoneum metastases | 0.65 (0.34–1.26) | 0.214 | 0.90 (0.44–1.83) | 0.766 |

| NLR (≥ 3.0 vs. <3.0) | 1.79 (0.99–3.25) | 0.034 | 2.02 (1.10–3.69) | 0.011 |

Fig. 2.

Forest plots for univariable analysis of progression-free survival and overall survival. Hazard ratios were estimated in a Cox proportional hazards regression model.

Safety

Table 4 presents a summary of hematologic toxicities related to the treatment. A singular case of treatment-related adverse event led to a patient’s death, attributed to febrile neutropenia. Any-grade hematological toxicities were observed in the majority of patients (n = 40, 83.3%), and grade 3 or 4 adverse events were observed in 30 patients (62.5%). The predominant grade 3 or 4 adverse events were neutropenia, affecting 29 patients (60.4%), and thrombocytopenia, impacting 10 patients (20.8%). No notable statistical difference in the occurrence of grade 3 or 4 neutropenia between patients with liver cirrhosis and those without (56% vs. 69.6%, p = 0.214). In contrast, grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia tended to occur more frequently in non-cirrhosis patients (8.0% vs. 34.8%, p = 0.034).

Table 4.

Hematological toxicities during treatment. 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; MKIs, multi-kinase inhibitors.

| Adverse events | Any grade, n (%) | Grade 3–4, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Cirrhosis (n = 25) |

Non-cirrhosis (n = 23) |

p value | ||

| All | 40 (83.3) | 30 (62.5) | 14 (56.0) | 16 (69.6) | 0.332 |

| Neutropenia | 37 (77.1) | 29 (60.4) | 13 (52.0) | 16 (69.6) | 0.214 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 31 (64.6) | 10 (20.8) | 2 (8.0) | 8 (34.8) | 0.034 |

| Anemia | 30 (62.5) | 3 (6.3) | 2 (8.0) | 1 (4.3) | 1.000 |

Subsequent treatment

Half of the patients (n = 24, 50.0%) received subsequent systemic therapy (Table 5). Among these, 18 patients (75.0%) were treated with a 5-FU plus cisplatin-based regimen, while MKIs and ICIs were administered to five patients (20.8%), respectively. For those who underwent retreatment with the 5-FU plus cisplatin-based chemotherapy, the disease control rate was 38.9%. In comparison, the disease control rates for patients receiving MKIs and ICIs were 20.0% and 80.0%, respectively.

Table 5.

Subsequent systemic treatment and effectiveness.

| Total (n = 24) | |

|---|---|

| 5-FU/cisplatin-based chemotherapy, n (%) | 18 (75.0) |

| 5-FU and cisplatin | 8 (33.3) |

| 5-FU, cisplatin and mitoxantrone | 12 (50.0) |

| Oral MKIs, n (%) | 5 (20.8) |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors, n (%) | 5 (20.8) |

| Disease control rate (%) | |

| 5-FU/cisplatin-based chemotherapy | 38.9 |

| Oral MKIs | 20.0 |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors | 80.0 |

Discussion

Effective systemic treatment options for advanced HCC are very limited, apart from MKIs and ICIs3. These drugs are financially burdensome and require a well-structured social security system to ensure accessibility13. However, in real-world settings, we frequently encounter patients who are physically well enough to undergo anti-cancer treatment but face significant financial barriers. Consequently, there are often gaps in accessing these latest treatments. Our study showed that 5-FU plus platinum-based chemotherapy can provide a limited but notable extension in survival duration for selected patients with advanced HCC. This finding suggests a potential alternative approach to address the unmet clinical needs in the treatment of advanced HCC.

Currently, the recommended first-line systemic treatments for advanced HCC are atezolizumab plus bevacizumab or tremelimumab plus durvalumab. However, the high cost of these new agents suggests that they may not be the most cost-effective treatment options14. This issue is particularly significant in developing countries with limited healthcare resources. A study conducted in Thailand indicated that atezolizumab plus bevacizumab is unlikely to be a cost-effective option compared to best supportive care for patients with unresectable HCC15. Therefore, in clinical settings with limited healthcare resources, more accessible cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents may be considered as alternatives.

Lee et al. reported on the efficacy of a triplet regimen consisting of 5-FU, cisplatin, and epirubicin in 31 patients with advanced HCC, noting a median OS of 7.8 months, which is comparable to the findings in our study16. Notably, responders showed significantly longer survival (median OS of 20.4 months vs. 4.9 months) compared to non-responders, indicating the presence of a patient group responsive to cytotoxic chemotherapy in advanced HCC. Furthermore, a recent phase III study reported that hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) using 5-FU and oxaliplatin extended disease-free survival as post-surgery adjuvant treatment17. These data support the effectiveness of 5-FU plus cisplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced HCC.

In patients with advanced HCC who have failed sorafenib treatment, second-line therapy with ICIs or MKIs as monotherapy has demonstrated median PFS of 2.8–5.2 months and median OS of 8.5–13.9 months18. Although our study involved a population in a different clinical setting and thus requires careful interpretation, it demonstrated a median PFS of 4.2 months and a median OS of 8.2 months. Therefore, this combination chemotherapy could be considered an alternative option for sorafenib-refractory HCC cases where ICIs or MKIs are not feasible. However, considering the frequent toxicity associated with combination chemotherapy, it is crucial to carefully select patients based on factors such as age, liver function, and performance status to ensure appropriate treatment.

The patients enrolled in our study were relatively young, with HBV identified as the predominant risk factor for HCC development. Consequently, comprehensive subgroup analyses based on age or etiology were not feasible. Most patients were classified as Child-Pugh class A (5), indicating a higher capacity to tolerate intensive cytotoxic chemotherapy and recover from associated toxicities19. Although all patients were categorized as stage C according to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system, nearly all presented with extrahepatic metastasis. These findings must be interpreted in the context of the population characteristics, as the majority of patients had undergone prior local treatments for primary HCC, including surgery, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), radiotherapy, and TACE. In regions such as South Korea, where HBV is a predominant cause of HCC20,21, regular health screenings facilitate early detection at localized stages, which may explain the high prevalence of patients receiving local treatments before systemic therapy22,23.

In relation to dose adjustments for ECF chemotherapy, a significant proportion of patients (81.3%) underwent dose reductions due to toxicity within the initial two cycles, and approximately 20% experienced unacceptable toxicity leading to permanent discontinuation. These findings suggest a need to modify the dosing protocol of the ECF regimen and indicate that it should be cautiously applied only to younger patients who maintain normal organ function. In terms of adverse events, a relatively large number of patients experienced grade 3 or higher hematological toxicities, with one treatment-related death due to febrile neutropenia. Consequently, careful monitoring and management of severe hematologic toxicities, along with proactive consideration of chemotherapy dose modifications, are essential24.

In our study, a high pretreatment NLR was associated with poorer survival outcomes. NLR, an inflammatory marker, has been recognized for its prognostic significance in various solid tumors, including HCC treated with local therapies such as RFA, radioembolization, and TACE, as well as with systemic therapy with sorafenib25. Consistent with these findings, our study suggests that pretreatment NLR may also serve as a prognostic marker in advanced HCC patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Additionally, patients with prior ICI treatment tended to have worse OS outcomes compared to those who had not received ICIs. Although the sample size was limited, of the 5 patients who received ICIs as a subsequent therapy, 3 demonstrated durable responses, with survival extending beyond 22 months, potentially influencing the OS outcomes. The role of cisplatin in inducing DNA damage suggests the possibility of a synergistic effect between platinum-based chemotherapy and ICIs26,27. Therefore, further research into the potential synergistic effects between cytotoxic chemotherapy and ICIs in advanced HCC could be intriguing27.

A significant number of patients who failed ECF treatment received 5-FU plus cisplatin-based chemotherapy as subsequent therapy. Among these patients, some had clinical benefit from ECF therapy but had to discontinue due to the cumulative cardiac toxicity of epirubicin. Others had undergone significant dose reductions because of hematological toxicity from the triplet regimen, which likely resulted in suboptimal dosing of 5-FU and cisplatin. Considering these factors, patients with no other alternatives for subsequent treatment, the dose of 5-FU and cisplatin was increased, or a combination treatment with mitomycin was administered.

We explored the potential of 5-FU plus cisplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced HCC based on our study’s findings. This represents an effort to address the current real-world clinical challenges and underscores the importance of maintaining interest in cytotoxic chemotherapy, even in the era of immunotherapy and MKIs. Recent small-scale studies have reported relatively high objective response rates with combination treatments involving 5-FU and cisplatin-based HAIC alongside MKIs, indicating the potential for novel therapeutic strategies28. Furthermore, combination approaches in advanced HCC, including HAIC with ICIs or triple regimens involving HAIC, ICIs, and MKIs, have also been investigated. Building on these prior studies, our findings suggest that systemic chemotherapy could serve as a viable component in combination strategies with immunotherapy or MKIs29.

The development of reliable biomarkers represents a pivotal factor in advancing these novel treatment strategies. While pathological diagnosis is integral in other malignancies, HCC is often diagnosed through imaging, which poses challenges in obtaining detailed tumor molecular biology data. To bridge this gap, the TCGA database provides critical insights into the molecular characteristics of HCC, addressing this limitation30. Recent studies have explored immune-related gene signatures to predict both prognosis and response to immunotherapy in HCC31. These advancements in combination therapies and biomarker research are poised to drive significant progress in advanced HCC treatment over the next five years. The combination of ICIs or MKIs with TACE has shown encouraging results in multiple studies. Furthermore, adoptive cell therapies, such as NK-cell therapy integrated with cytotoxic chemotherapy, are actively being evaluated4,32. Continued research to identify patient populations most likely to benefit from specific therapeutic strategies4,31 could significantly enhance the survival outcomes of patients with advanced HCC.

This study has several limitations. Its single-arm, retrospective design does not allow for a comparative analysis to fully determine the efficacy of cytotoxic chemotherapy. Additionally, the heterogeneity of chemotherapy regimens and the variation in treatment lines complicate the interpretation of the results. The 15-year study period hindered reliable collection of non-hematologic toxicity data, making it difficult to assess the combination therapy’s impact on quality of life. Additionally, the patient characteristics during this period do not fully reflect current treatment standards, limiting subgroup analyses on the relationship between cytotoxic chemotherapy and immunotherapy in real-world settings. Finally, the small sample size and the high prevalence of patients with chronic hepatitis B should be considered when interpreting the findings. Nevertheless, with about one-third of patients achieving a PFS of over 6 months and many achieved an OS exceeding one year suggests that cytotoxic chemotherapy may still play a modest but meaningful role in prolonging survival.

Conclusions

This study suggests that 5-FU plus cisplatin-based chemotherapy could serve as a viable systemic treatment option for patients with advanced HCC and preserved liver function, particularly in cases where access to ICIs and MKIs is limited. This affordability is especially important in developing countries, providing a feasible alternative where access to advanced therapies is restricted. Further research is recommended to validate these findings and explore integrative treatment strategies for patients with advanced HCC in resource-limited settings.

Methods

Patients

The clinicopathological and survival outcome data from patients diagnosed with advanced HCC who received palliative ECF chemotherapy at the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital and Suwon St. Vincent’s Hospital between April 2009 and October 2023 were analyzed. Eligibility for this study required meeting several following criteria: (1) histologically or clinically confirmed HCC in alignment with international guidelines; (2) a stage C based on the BCLC prognosis and treatment strategy33; and (3) verifiable disease progression and survival status at the time of data collection. Data were retrospectively gathered, including age at treatment initiation, gender, etiology, history of local therapies (such as surgery, TACE, radiotherapy, and RFA), prior systemic treatments, CPS, tumor markers, metastatic sites, the NLR at the start of ECF chemotherapy, toxicities, subsequent systemic treatments, and survival outcomes. Liver cirrhosis was classified as present if any of the following criteria were met: characteristic features of cirrhosis, including but not limited to liver surface nodularity or indirect evidence of portal hypertension on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); transient elastography showing liver stiffness ≥ 15 kPa; or clinical signs of portal hypertension, such as the presence of esophageal or gastric varices confirmed by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

Treatment

Patients received intravenous infusion of epirubicin (50 mg/m2 on day 1), cisplatin (60 mg/m2 on day 1), and 5-FU (1000 mg/m2 over 8 h on day 1 to 3 or 200 mg/m2 over 12 h on day 1) every 28 days. Treatment continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or upon the patient’s refusal to continue. The treatments were halted before the maximum cumulative dose of epirubicin exceeded 650mg/m2. Chemotherapy dose interruption or modification were allowed during treatment course to manage adverse events. The RDI of chemotherapy was calculated as the percentage ratio of the actual delivered dose intensity to the planned dose intensity. Tumor response was assessed by investigators every 8 to 12 weeks using CT scans or MRI, in accordance with RECIST version 1.1, and serum AFP levels were also monitored. Adverse events were evaluated following the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported as proportions or medians with ranges or IQR, and proportions. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. PFS was defined as the interval between initiation of ECF chemotherapy and the onset of either progressive disease or death from any cause. OS was calculated from the start date of ECF chemotherapy to either the date of the last follow-up or death due to any cause. Survival outcomes were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and these were subsequently compared through the two-tailed log-rank test. Hazard ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the stratified Cox proportional hazards model. All conducted tests were two-sided, and p values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows version 24.0 (IBM SPSS Inc., Armonk, New York, USA) along with GraphPad Prism version 10.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

All authors helped to perform the research; Park SJ and Kim HH were involved with manuscript writing, drafting conception and design, acquisition of data, performing procedures and data analysis; Park SJ, Shin KS, Kim IH, Lee MA, and Hong TH contributed to writing the manuscript; Kim HH contributed to writing the manuscript, drafting conception and design, performing procedures and data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors wish to acknowledge the financial support provided by the Catholic Medical Center Research Foundation for the program years 2023 and 2024.

Data availability

The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study conformed to Korean regulations and the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for data acquisition was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of The Catholic University of Korea (approval ID: KC23RCDI0316). Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study, as approved by the ethics committee of The Catholic University of Korea.

STROBE statement

The authors have read the STROBE Statement-checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement-checklist of items.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abou-Alfa GK et al (2022) Tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. NEJM Evid. 1:EVIDoa2100070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finn RS et al (2020) Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 382:1894–1905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang, C. et al. Evolving therapeutic landscape of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Reviews Gastroenterol. Hepatol.20, 203–222 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rizzo, A. & Ricci, A. D. Vol. 23 11363 (MDPI, (2022).

- 5.Rizzo, A., Ricci, A. D. & Brandi, G. Trans-arterial chemoembolization plus systemic treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. J. Personalized Med.12, 1788 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sahin TK, Ayasun R, Rizzo A, Guven DC (2024) Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-eosinophil ratio (NER) in cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer. 16:3689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizzo, A. et al. Peripheral neuropathy and headache in cancer patients treated with immunotherapy and immuno-oncology combinations: the MOUSEION-02 study. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol.17, 1455–1466 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guven, D. C. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related hearing loss: a systematic review and analysis of individual patient data. Support. Care Cancer. 31, 624 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang, A., Yang, X. R., Chung, W. Y., Dennison, A. R. & Zhou, J. Targeted therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Signal. Transduct. Target. Therapy. 5, 146 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vezhnovets, T., Gurianov, V., Prus, N., Korotkyi, O. & Antoniuk, O. Health care expenditures of 179 countries with different GNI per capita in 2018. (2021). [PubMed]

- 11.Kim, D. W., Talati, C. & Kim, R. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): beyond sorafenib—chemotherapy. J. Gastrointest. Oncol.8, 256 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Batran, S. E. et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): a randomised, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet393, 1948–1957 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aly, A., Ronnebaum, S., Patel, D., Doleh, Y. & Benavente, F. Epidemiologic, humanistic and economic burden of hepatocellular carcinoma in the USA: a systematic literature review. Hepatic Oncol.7, HEP27 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su, D., Wu, B. & Shi, L. Cost-effectiveness of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs sorafenib as first-line treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. JAMA Netw. Open.4, e210037–e210037 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sriphoosanaphan, S. et al. Cost-utility analysis of atezolizumab combined with bevacizumab for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in Thailand. Plos One. 19, e0300327 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, J. E. et al. Epirubicin, cisplatin, 5-FU combination chemotherapy in sorafenib-refractory metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterology: WJG. 20, 235 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li, S. H. et al. Postoperative adjuvant hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with FOLFOX in hepatocellular carcinoma with microvascular invasion: a multicenter, phase III, randomized study. J. Clin. Oncol.41, 1898 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim, B. H. & Park, J. W. Systemic therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: consideration for selecting second-line treatment. J. Liver cancer. 21, 124 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyman, G. H., Abella, E. & Pettengell, R. Risk factors for febrile neutropenia among patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy: a systematic review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol.90, 190–199 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim, D. Y. & Han, K. H. Epidemiology and surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver cancer. 1, 2–14 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeo, Y. et al. Viral hepatitis and liver cancer in Korea: an epidemiological perspective. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev.14, 6227–6231 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong, S. Y., Kang, M. J., Kim, T., Jung, K. W. & Kim, B. W. Incidence, mortality, and survival of liver cancer using Korea central cancer registry database: 1999–2019. Annals of hepato-biliary-pancreatic surgery. 26, 211 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Singal, A. G., Lampertico, P. & Nahon, P. Epidemiology and surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma: new trends. J. Hepatol.72, 250–261 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt-Hieber, M., Teschner, D., Maschmeyer, G. & Schalk, E. Management of febrile neutropenia in the perspective of antimicrobial de-escalation and discontinuation. Expert Rev. anti-infective Therapy. 17, 983–995 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mouchli, M., Reddy, S., Gerrard, M., Boardman, L. & Rubio, M. Usefulness of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as a prognostic predictor after treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Review article. Ann. Hepatol.22, 100249 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dasari, S. & Tchounwou, P. B. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Pharmacol.740, 364–378 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu, H. et al. Oxaliplatin induces immunogenic cell death in hepatocellular carcinoma cells and synergizes with immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cell. Oncol.43, 1203–1214 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maruta, S. et al. Combination therapy of lenvatinib and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy using cisplatin with lipiodol and 5-fluorouracil: a potential breakthrough therapy for unresectable advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cureus16, e66185 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Ding, Y. et al. The worthy role of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy in combination with anti-programmed cell death protein 1 monoclonal antibody immunotherapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Immunol.14, 1284937 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ally, A. et al. Comprehensive and integrative genomic characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell169, 1327–1341 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang, F. et al. An immune-related gene signature predicting prognosis and immunotherapy response in hepatocellular carcinoma. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen.25, 2203–2216 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bae, W. K. et al. A phase I study of locoregional high-dose autologous natural killer cell therapy with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Immunol.13, 879452 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsilimigras, D. I. et al. Prognosis after resection of Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage 0, a, and B hepatocellular carcinoma: a comprehensive assessment of the current BCLC classification. Ann. Surg. Oncol.26, 3693–3700 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.