Abstract

Asthma is the most common chronic disease to affect pregnant women and can have a significant effect on pregnancy outcomes, with increased rates of preterm birth, premature delivery and caesarean section observed if poorly controlled. Pregnancy can also influence asthma control. Prescribing in pregnancy causes anxiety for patients and healthcare professionals and can result in alteration or undertreatment of asthma. Good asthma control with prompt and adequate management of exacerbations is key to reducing adverse pregnancy outcomes for both mother and fetus. The majority of asthma treatment can be continued as normal in pregnancy and there is emerging evidence of the safety of biologic medications also.

This article aims to summarise the current evidence about asthma in pregnancy and guide the appropriate management of this population.

Keywords: Asthma, Pregnancy, Maternal medicine, Prescribing in pregnancy, Biologics in pregnancy, Biologics for asthma

Key points.

-

1.

Good control of asthma and reduction in exacerbations are key to improving maternal and fetal outcomes in pregnancy

-

2.

Poor control and frequent exacerbations are associated with increased rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

-

3.

The vast majority of treatments for asthma can be given safety (and as for the non-pregnant patient) in pregnancy, including inhaled therapies and corticosteroids.

-

4.

There is limited but fast-growing evidence for the safety of biologic medications for asthma in pregnancy and a recent international consensus supporting their use.

-

5.

The risk of exacerbation in labour is low and decision for caesarean section should be made for obstetric reasons only, and ergometrine should be avoided due to risk of bronchospasm.

Asthma and pregnancy

Asthma is the most common chronic disease in pregnancy and affects an estimated 6.5% of adults in the UK.1 Reported prevalence varies but it is estimated to affect between 8 and 12% of pregnant women.1 It is a chronic respiratory condition with variable airflow obstruction caused by airway inflammation and hyper-responsiveness, and characterised by symptoms of cough, wheeze, shortness of breath and chest tightness.

There are well-documented physiological changes that occur within the respiratory system in pregnancy: increased oxygen demand and an increase in minute ventilation from early pregnancy; later, increased elevation of the diaphragm to accommodate the pregnancy, resulting in a reduction in tidal volume. Notably, forced expiratory volume in 1 second, forced vital capacity and peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) are unaffected by pregnancy.2

The severity of asthma can change in pregnancy, with a quarter thought to deteriorate.3 Several mechanisms have been proposed for this: hormonal and mechanical changes of pregnancy,4 increased susceptibility to viral infections5 and altered adherence to treatment.6 Women often attribute dyspnoea to the pregnancy rather than deteriorating asthma control, leading to potential undertreatment.

For most women, significant adverse effects are not observed but, with exacerbations of asthma and poor control, there are observed associations with low birth weight, preterm delivery and intra-uterine growth restriction.4 There are also associations with increased rates of pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes and caesarean section (CS).4 Active management of asthma can reduce the risk of preterm delivery to non-significant levels4 and, if asthma is well controlled, there is a minimal risk of poorer outcomes.

Management of asthma in pregnancy

The focus should be on maintaining or achieving good asthma control for optimal pregnancy outcomes. Management should be essentially the same as for the non-pregnant patient: there should be a review in early pregnancy with a focus on good control and continuing treatment; markers of activity like PEFR and fractional exhaled nitric oxide can be used to assess control; care should include assessment of medication adherence and inhaler technique, and a personalised asthma management plan should be created.4 Exacerbating factors should be addressed: gastro-oesophageal reflux is common and should be treated; smoking cessation should be encouraged; infection can precipitate exacerbation and should be treated promptly.7 The COVID and flu vaccinations are licensed in pregnancy and should be encouraged as part of routine care, especially as, during the COVID pandemic, COVID became one of the highest causes of mortality in pregnancy.8

Medication safety in pregnancy is a common anxiety for patients, and health professionals and patients should be reassured of the safety of continuing common asthma medications. These are summarised in Table 1 and have been used for many years with no evidence of increase in fetal abnormality or adverse fetal effect.9

Table 1.

| Indication | Safety | |

|---|---|---|

| SABAa eg salbutamol |

Previously recommended as reliever therapy for all asthma sufferers | Safe to use, unlikely to cause any fetal abnormalities |

| ICSa eg budesonide, fluticasone |

Now preferred in combination with SABA or LABA for reliever and maintenance therapy | No risk identified at normal doses. More data for budesonide and beclomethasone, but should continue alternative if established pre-pregnancy |

| LABAa eg formoterol |

Now preferred in combination with ICS for reliever and maintenance therapy | No risk identified in the available data. More data with salmeterol, but should continue alternative if established pre-pregnancy |

| LTRAa | Can be used as add-on therapy after ICS and LABA, but less data for efficacy | Limited data, but no evidence of significant malformation. Can be used if needed in pregnancy. |

SABA, short-acting beta-agonist; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta agonist; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonists.

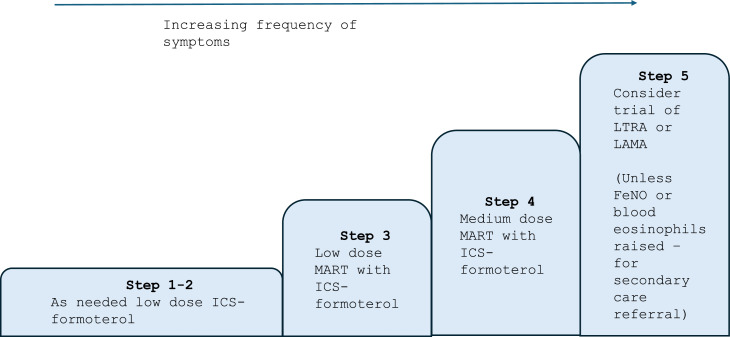

Management in pregnancy follows the same stepwise approach as outside pregnancy, recommended by the British Thoracic Society and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).10 In recent years there has been a move towards combined maintenance and reliever therapy (MART), which is reflected in the latest joint guidance on asthma management.10 This is based on evidence that has demonstrated fewer severe exacerbations with a combination of formoterol and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) than short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) as a reliever. This should be followed in pregnancy, and women should continue MART or be initiated on this if optimisation in pregnancy is required.

Fig. 1 is the preferred stepwise approach for asthma and should be used for all new diagnoses. For patients established on a SABA inhaler who have a preference to continue, in step 1 they should use the ICS whenever the SABA is taken and in step 2 have low-dose maintenance ICS plus SABA as needed.

Fig. 1.

Adapted stepwise approach as outlined by NICE and the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA).4,10

Abbreviations: ICS (inhaled corticosteroids), MART (maintenance and reliever therapy), LTRA (Leukotriene receptor antagonists), LAMA (Long-Acting Muscarinic Antagonists), FeNO (Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide).

Oral corticosteroids (OCS), typically prednisolone, are used as a rescue therapy for asthma exacerbation. There have been conflicting data regarding their use in pregnancy, as there are studies that suggest an increase in cleft palate when used in the first trimester; however, this is not seen consistently.

Prednisolone is not transferred across the placenta in significant amounts (<10%), and it is recommended that the significant benefit outweighs the possible risk. They should not be withheld if needed.9,10

A common theme when assessing adverse events in pregnancy is that women are treated differently because they are pregnant.8 Conventional asthma treatments have been shown repeatedly to be safe in pregnancy, and cessation poses a much higher risk to a woman than continuing treatment.

Biologics for asthma

Biologics are being used increasingly for asthma management in those for whom conventional treatment has not been effective. They have been shown to reduce exacerbations, are steroid sparing and improve quality of life.12,13

IgG antibodies cross the placenta from early pregnancy, increasing significantly in the third trimester via active transport through the upregulated Fc receptor. This results in full-term babies having comparable IgG levels to their mothers, protecting them from common pathogens that they may be exposed to.14 Biologics are IgG antibodies and therefore it is expected there will be significant levels of the biologic in the babies of mothers who have taken biologics in pregnancy.

The data available on the safety of these are limited but growing. Table 2 summarises common biologics and data available. There have, to date, been no randomised controlled trials on the use of biologics in asthma; however, the growing body of evidence from exposures and case series do not show any association between biologic use and adverse outcomes in, or following, pregnancy. There is most evidence for omalizumab published in the EXPECT registry15 and there is ongoing international data collection in registries for the other biologics. International consensus amongst experts in a recent Delphi study is that biologics can be used during conception and in pregnancy and also initiated in pregnancy, following the same prescribing criteria as in the non-pregnant patient.13 It was emphasised that there should be risk versus benefit discussions with patients when making decisions about biologics in pregnancy.

Table 2.

| Mechanism | Data in pregnancy | |

|---|---|---|

| Omalizumab | IgG1 antibody to anti-IgE | Best studied so far. Omalizumab pregnancy registry, EXPECT, shows no difference in congenital anomalies, low birth weight or SGA compared to asthma population |

| Mepolizumab | IgG1k antibody to IL-5 | Registry data collection ongoing – expected 2026. No signal of harm in animal studies and a small number of case reports |

| Bendralizumab | IgG1k antibody to IL-5R on basophils and eosinophils | No signal of harm in animal studies and in a small number of case reports |

| Dupilumab | IgG4 antibody blocks IL-4 | Registry data collection ongoing – expected 2026. No signal of harm in seven case reports reviewed of maternal exposure |

| Reslizumab | IgG4 antibody blocks IL-5 | No signal of harm in animal studies |

With regards to the timing of live vaccines to the infant, when exposed in utero in the third trimester, experts were unable to reach a consensus. Until further evidence is available, following the advice from rheumatology guidelines16 and delaying live vaccines until 6 months of age if there has been third trimester exposure to biologics is likely most appropriate.

Exacerbations in pregnancy

The priority in management of exacerbations is to treat early and adequately to avoid maternal, and subsequent fetal, hypoxia. Oxygen therapy should be given to maintain oxygen saturations of 94–98%. When interpreting an arterial blood gas, note that mild hypocapnia is normal in pregnancy, so a normal or raised arterial carbon dioxide level (PaCO2) would be significant. Pharmacological management can be given as would be to the general population, including the use of nebulised bronchodilators, either intravenous (IV) or oral corticosteroids, and IV magnesium,4 with emphasis placed on not withholding care due to pregnancy. The RCP toolkit provides an excellent summary of interpretation of signs and investigations in pregnancy and a guide to differentials to be considered for several common acute presentations, including shortness of breath.17

Considerations for labour and delivery

Asthma exacerbations in labour and delivery are uncommon, with reported rates of 10% in the peripartum period.18 There are no specific studies to evaluate intrapartum management; however, there is general consensus that a delivery plan should be implemented. As pain can be a trigger for exacerbations, adequate pain relief should be considered, and an epidural is recommended for this as it reduces minute ventilation and oxygen consumption.4 If a patient has been on an OCS dose of more than or equal to prednisolone 5 mg (or equivalent) for the 3 weeks prior to delivery, they should receive hydrocortisone 50 mg four times a day during labour.19

While CS rates are higher in women with asthma,9 the decision for a CS should be based on obstetric considerations only. Uterotonics can have an effect on the respiratory system: oxytocin can safely be used for induction of labour and is the drug of choice for management of a postpartum haemorrhage, and prostaglandins E1 and E2 can be used also. Ergometrine and its derivatives can cause bronchospasm and are generally avoided.9

Breastfeeding is encouraged, where possible, for all women for its numerous benefits and all conventional asthma treatments can be used in breastfeeding.20

Pre-conception counselling

The priority when planning a pregnancy should be achieving good disease control in advance of planned pregnancy. Organogenesis occurs in the first trimester and as there is an association with risk of birth defects and asthma, it is beneficial to ensure good control at this time. There is varied evidence on fertility and asthma, with one recent study showing that women on SABA only had reduced fertility, while those taking ICS did not, raising the possibility that the systemic inflammation might affect fertility.9 Among experts, there is consensus that biologics could be continued while trying to conceive.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

CE Jones: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology. Y. Jamil: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education (CME) activity. Completion of this CME activity enables RCP members to earn two external CPD credits. The CME questions are available at: https://cme.rcp.ac.uk/ in the title page.

References

- 1.NICE Clinical Knowledge summary: asthma. Updated 2024. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/asthma/. Accessed 29 November, 2024.

- 2.Soma-Pillay P, Nelson-Piercy C, Tolppanen H, Mebazaa A. Physiological changes in pregnancy. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2016;27(2):89–94. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2016-021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grosso A, Locatelli F, Gini E, et al. The course of asthma during pregnancy in a recent, multicase–control study on respiratory health. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2018;14:16. doi: 10.1186/s13223-018-0242-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global strategy of asthma management and prevention. 2024. Available from https://ginasthma.org. Accessed 23 November, 2024.

- 5.Forbes RL, Gibson PG, Murphy VE, et al. Impaired type I and II interferon response to rhinovirus infection during pregnancy and asthma. Thorax. 2021;67(3):209–214. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy VE, Gibson P, Talbot PI. Severe asthma exacerbations during pregnancy. Thorax. 2005;5:1046–1054. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000185281.21716.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robijn AL, Bokern MP, Jenson ME, et al. Risk factors for asthma exacerbations during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Resp Rev. 2022;31 doi: 10.1183/16000617.0039-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knight M., Bunch K., Felker A., Patel R., Kotnis R., Kenyon S., Kurinczuk J.J., editors. on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers' Care Core Report - Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2019-21. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford; Oxford: 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Middleton PG, Gade EJ, Aguilera C, et al. ERS/TSANZ Task Force Statement on the management of reproduction and pregnancy in women with airways diseases. Eur Respir J. 2020;55 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01208-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nice Guideline. Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management (BTS, NICE, SIGN). 2024: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng245. Accessed 29 November, 2024.

- 11.UKTIS – Evidence-Based. Safety Information about Medication, Vaccine, Chemical and Radiological Exposures in Pregnancy. https://uktis.org/ Accessed 22 November, 2024.

- 12.Shakuntulla F, Chiarella SE. Safety of biologics for atopic diseases during pregnancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(12):3149–3155. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naftel J, Jackson D, Coleman M, et al. An international consensus on the use of asthma biologics in pregnancy. Lancet Respir Med. 2024;S2213-2600(24):00174–00177. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(24)00174-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Palmeira P, Quinello C, Silveira-Lessa AL, et al. IgG placental transfer in healthy and pathological pregnancies. Clin Dev Immunol. 2011;2012:985646. doi: 10.1155/2012/985646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Namazy K, Cabana M, Scheuerle AE, et al. The Xolair Pregnancy Registry (EXPECT): the safety of omalizumab use during pregnancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(2):407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell M, Dey M, Flint J, et al. British Society for Rheumatology guideline on prescribing drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding: immunomodulatory anti-rheumatic drugs and corticosteroids. Rheumatology, 2023;62:e48–e88. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keac551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Royal College of Physicians and Society of Acute medicine. Acute care toolkit 15: managing acute medical problems in pregnancy. 2019: https://www.rcp.ac.uk/improving-care/resources/acute-care-toolkit-15-managing-acute-medical-problems-in-pregnancy/. Accessed 23 November, 2024.

- 18.Gluck JC, Gluck PA. The effect of pregnancy on the course of asthma. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;26(1):63–80. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NICE guideline. Intrapartum care for women with existing medical conditions or obstetric complications and their babies. 2019: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng121. Accessed 23 November, 2024. [PubMed]

- 20.Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet] National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Bethesda (MD): 2006. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/ Available from. [Google Scholar]