Abstract

Avicins are a recently discovered family of plant-derived terpenoid molecules that possess proapoptotic, antiinflammatory, and cytoprotective properties in mammalian cells. Previous work demonstrating that avicins can exert their effects by suppressing or activating the redox-sensitive transcription factors NF-κB and nuclear factor-erythroid 2 p45-related factor (Nrf2), respectively, has raised the idea that they may react with critical cysteine residues. To understand the molecular mechanism through which avicins regulate protein function, we examined their effects on the paradigmatic redox-responsive transcriptional activator, OxyR of Escherichia coli, which protects bacterial cells against oxidative and nitrosative stresses. In vitro transcription assays demonstrated that avicins activate OxyR and its target genes katG and oxyS in a DTT-reversible manner. In addition, katG-dependent hydroperoxidase I activity was enhanced in avicin-treated bacteria. Mass spectrometric analysis of activated OxyR revealed thioesterification of the critical regulatory cysteine, Cys-199, to an avicin fragment comprising the outer monoterpene side chain. Our results indicate that avicinylation can induce adaptive responses that protect cells against oxidative or nitrosative stress. More generally, transesterification may represent a previously undescribed thiol-directed posttranslational modification, which extends the code for redox regulation of protein function.

Keywords: cysteine, terpenes, thioester, OxyR, redox

Classic signal transduction is characterized by ligand-induced stimulation of pathways comprised of interconnected groups of proteins that undergo various regulatory modifications. Redox-based signaling usually involves small reactive molecules, which covalently and reversibly modify specific cysteine targets to regulate multiple cell processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (1). Recent work has demonstrated a significant interface that connects a prototypic redox-related signaling process, S-nitrosylation, with ligand-induced signaling involving multiprotein complexes (2, 3), and accumulating evidence suggests that malfunction in redox-based signaling may underlie disease pathogenesis (4-7). Hence, redox regulation may play an important role in normal physiology, as well as in a growing list of medical disorders.

Cells adapt to various forms of stress in part by activating redox-responsive genes, which encode proteins involved in detoxification, repair, and maintenance of homeostasis. Several classes of redox-sensitive transcription factors have been shown to regulate the expression of these genes (8). Studies designed to elucidate the mechanism by which such transcription factors are regulated have revealed the importance of critical cysteine residues, which play sensory as well as regulatory roles in transcriptional responses. In particular, cysteine thiols in transcription factors have been shown to exhibit highly selective and differential reactivity toward different reactive oxygen or nitrogen species (9-11). Transcription factors are thus capable of processing different nitric oxide (NO)/redox-based signals into distinct transcriptional responses.

Avicins form a family of plant stress metabolites that are capable of activating stress adaptation in human cells (12). Stress regulation by avicins in mammalian cells is a result of their ability to: (i) eliminate damaged and stressed cells by apoptosis (13, 14); (ii) suppress inflammatory responses via inhibition of NF-κB activity and thereby expression of its downstream targets, which include inducible NO synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 (15); (iii) diminish the generation of reactive oxygen species, apparently by decreasing the rate of oxygen consumption (unpublished data); (iv) activate the transcription factor nuclear factor-erythroid 2 p45-related factor (Nrf2) and/or its downstream target genes, which encode for multiple antioxidant proteins, including glutathione peroxidase, thioredoxin reductase, and hemeoxygenase, thereby reducing both peroxide and disulfide stress (12). NF-κB and Nrf2 are both redox-sensitive transcription factors, that is, critical thiols are present in their DNA-interacting domains (e.g., p65 and p50 of NF-κB) and/or in partner proteins (IκB-kinase and Keap-1) that sequester NF-κB and Nrf2, respectively, in the cytoplasm (8, 16, 17). Avicins contain an unusual side chain with two Michael reaction sites (α,β-unsaturated carbonyl groups) (13) in the inner and outer monoterpenes. It was therefore predicted that avicins would react with nucleophiles, especially cysteine sulfhydryl groups, by a Michael-type addition (to yield a thioether-linked cysteine adduct). However, modification by avicins of critical cysteine residues in NF-κB and Nrf2 was reversed by DTT (12, 15), indicating an alternative, thiol-based means of regulation.

To elucidate the nature of the function-regulating interaction of avicins with cysteine residues, we explored their effects on a well characterized redox-regulated response that is controlled by the Escherichia coli transcriptional activator OxyR. In response to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or S-nitrosothiols, OxyR triggers the expression of multiple protective genes (18-20). Each OxyR monomer has six cysteine residues, of which only Cys-199 is essential for regulation by redox agents (21). Earlier studies concluded that OxyR activation involves formation of an intramolecular disulfide bond between Cys-199 and -208, representing an “on-off switch” (19, 22). However, recent work has suggested an alternative model, wherein Cys-199 thiol can undergo a range of NO-dependent electrophilic and oxidative modifications as well as NO-independent oxidation by reactive oxygen species or by disulfide exchange (20, 23). These modifications are capable of eliciting unique functional effects (24), and thus cysteine modification by S-nitrosylation or by oxidation to form either a mixed disulfide with glutathione (S-SG, S-glutathionylation), an intramolecular disulfide (S-S), or a sulfenic acid (S-OH, S-hydroxylation) provides the basis for a molecular code that relates structure to function (23). Here we expand this paradigm by revealing that avicins activate OxyR by thioesterification of a small avicin fragment to the single critical Cys-199. Avicinylation of proteins is a reversible thiol-directed modification through which adaptive responses to nitrosative and oxidative stress can be regulated.

Materials and Methods

Avicins. Ground seedpods of Acacia victoriae were extracted in 20% MeOH as described (25). Solvent/solvent partitioning of the extract concentrated the bioactivity in a polar fraction designated (F094). Avicins D and G were purified from F094 as described (25).

Reduction of OxyR. The reduced form of OxyR was generated by addition of a large excess of DTT (200 mM) for 1 h, followed by exhaustive dialysis (25 mM potassium phosphate/250 mM potassium sulfate/1 mM magnesium sulfate/100 μM DTPA, pH 8) in an anaerobic glove box. Removal of DTT was monitored by the color change after addition of 5,5′-dithionitrobenzoic acid to an aliquot of the dialysis buffer.

Treatment of OxyR with Avicins. Reduced OxyR was treated with a 10-fold molar excess of F094 or purified avicin D or G to generate avicin-modified OxyR. The reaction was performed under anaerobic conditions for 1 h, followed by dialysis.

In Vitro Transcription and Primer Extension. In vitro transcription with the various modified forms of OxyR was performed as described (23). Plasmid pBT22 was used as the katG template and pUCOXYS, a plasmid containing the oxyS-coding region cloned into pUC19, was used as the oxyS template. Where indicated, avicin-modified forms of OxyR were reduced with 200 mM DTT. Primer extension assays were performed by using AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega), according to instructions supplied by the manufacturer.

Hydroperoxidase I (HPI) Assay. The peroxidase activity of HPI was measured as described (20), in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM H2O2, and 0.2 mg/ml o-dianisidine, by measuring the increase in absorbance at 460 nm (26). An extinction coefficient of 11.3 mM-1·cm-1 was used to calculate the specific activity of HPI (27).

Electrospray Ionization (ESI)/MS. ESI/MS (ESI/MS) was performed with a mass spectrometer equipped with an orthogonal electrospray source (Z-spray) operated in positive ion mode (LCT, Waters Micromass MS Technologies). Sodium iodide was used for mass calibration for a calibration range of m/z 100-2,500. Trypsin (2 μl, 1 mg/ml) was added to avicin-modified OxyR (500 μl, 150 μg/ml), and the mixture was incubated for 5 h at 37°C. Trypsin-digested proteins were suspended in 50% acetonitrile/50% and 0.1% formic acid at a concentration of ≈50 pmol/μl and infused into the electrospray source at a rate of 5-10 μl·min-1. Optimal ESI/MS conditions were: capillary voltage 3,000 V, source temperature 110°C, and a cone voltage of 55 V. The ESI gas was nitrogen. A quadrupole was set to optimally pass ions from m/z 500-2,000, and all ions transmitted into the pusher region of the TOF analyzer were scanned over m/z 500-3,000, with a 1-s integration time. Data were acquired in continuous mode until acceptable averaged data were obtained (10-15 min). ESI/MS data were deconvoluted by using MaxEnt I (Waters Micromass MS Technologies).

MALDI-TOF/MS. Avicin-modified OxyR was trypsin digested as above, followed by addition of 5 μl of 10% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to stop the digest. MALDI-TOF was performed with a mass spectrometer operated in linear positive ion mode with an N2 laser (Reflex III, Bruker, Bremen, Germany). Laser power was restricted to the minimum level required to generate a signal, and the accelerating voltage was set at 28 kV. The instrument was calibrated with protein/peptide standards bracketing the molecular weights of the protein/peptide samples (typically, mixtures of apomyoglobin and BSA using doubly charged, singly charged, and dimer peaks as appropriate, or bradykinin fragment 1-5 and adrenocorticotropic hormone fragment 18-39 for tryptic digest analysis). Samples were prepared in 0.1% TFA at an approximate concentration of 50 pmol/μl. Sinapinic acid was used as the matrix for proteins and α-cyano-4-hydroxy-cinnamic acid as the matrix for peptides prepared as saturated solutions in 50% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA (in water). Aliquots of 1 μl of matrix and 1 μl of sample were mixed thoroughly, and 0.5 μl of the mixture was spotted on the target plate and allowed to dry.

Results

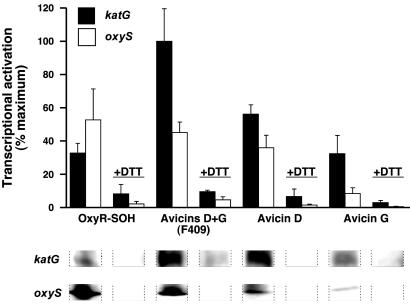

Exposure of reduced OxyR to room air [which generates Cys-199-SOH (23)] or to F094 (an unspecified mixture of avicin D and G), avicin D or G (avicins: OxyR, 1:10-100:1) under strictly anaerobic conditions resulted in OxyR activation as assessed by in vitro transcriptional activation of katG and oxyS (Fig. 1). F094 and avicin D were more potent activators than avicin G. Additional results, although preliminary, suggest that avicins can exert a graded and cooperative effect on both promoters (not shown). Addition of DTT after avicin modification reversed OxyR activation (Fig. 1). Thus, a thiol-based modification by avicin activates OxyR, and DTT sensitivity indicates that the modification is reversible rather than thioether-based.

Fig. 1.

In vitro transcriptional activation by avicin-modified OxyR. Avicin-modified OxyR was incubated with plasmids containing the katG or oxyS genes followed by primer extension (see Materials and Methods). After primer extension, samples were untreated or treated with DTT before gel analysis. Band intensities were quantified (phosphoimager), and data are plotted at top as percent maximal activation (n = 2-3). At bottom, corresponding raw data from an individual experiment are depicted.

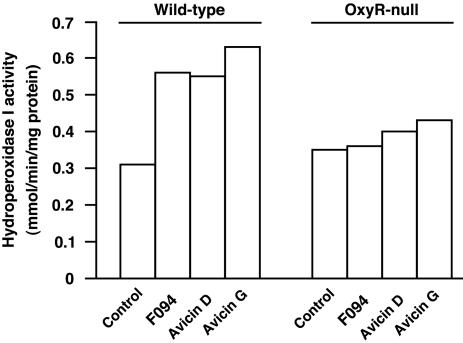

Activation of OxyR by avicin in situ was demonstrated by examining the induction of HPI. HPI, the enzyme encoded by the katG gene, protects bacterial cells against hydrogen peroxide-induced stress. Wild-type (RK4936) and OxyR-null (TA4112) strains of bacteria were treated with avicins and assayed for HPI activity. As shown in Fig. 2, F094, avicin D, and avicin G doubled HPI activity in wild-type cells, whereas no increase in activity was seen in OxyR-null cells. That avicin G was as potent an inducer of HPI as F094 and avicin D, even though its in vitro transcriptional activity was lower (Fig. 1), suggests that avicins may have additional direct effects on protein activity.

Fig. 2.

Induction of HPI by avicins in intact cells. E. coli strains RK4936 (wild-type) and TA4112 (OxyR-null) were grown aerobically to an A600 of 0.5 and then treated with 100 μM F094 or avicin D or G for 60 min. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, and the peroxidase activity in crude extracts was determined (see Materials and Methods).

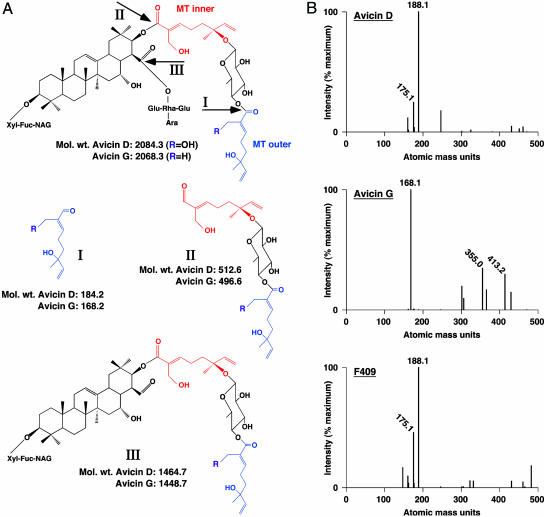

To identify the nature of the modification, the structure of avicin-modified OxyR was analyzed by ESI/MS (Fig. 3) and MALDI-TOF/MS (Table 1). In Fig. 3A, structures I-III show the theoretical fragmentation products that would result from scission of avicin fragments thioester-linked to OxyR. To identify the avicin-derived OxyR adduct, we analyzed by ESI/MS the low-molecular-weight products [<500 atomic mass units (amu)] of tryptic digests of OxyR modified by avicin G or D or F409. As shown in Fig. 3B, the major fragments recovered exhibited masses of 168.1 amu (avicin G) or 188.1 amu (avicin D or F409). Analysis by MALDI-TOF of tryptic digests of avicin-modified OxyR indicated a mass shift of 168.1 amu for the adducts derived from avicins G and D and F409 (Table 1). Note that an identical mass of 168.1 amu for the adduct derived from avicin G (R-group = H) or avicin D (R-group = OH), as determined by MALDI-TOF/MS, suggests the possible loss of a water molecule (or laser-induced changes during MALDI-TOF/MS). Taken together, these observations rule out the involvement of structures II and III and indicate that structure I is coupled to OxyR (Fig. 3). Michael acceptor sites are apparently not involved in the modification, but rather the reactive (electrophilic) carbonyl group of the outer monoterpene side chain (structure I) subserves transesterification (oxyester → thioester) of OxyR cysteine thiol. Mild alkaline hydrolysis also results in cleavage of avicins that yields structure I (25), which emphasizes the relative lability of the oxyester linkage that incorporates structure I within avicins.

Fig. 3.

Transesterification of OxyR by avicins. (A) The structures of avicins D and G show the presence of two monoterpenoid (MT) units (designated MT inner and MT outer), each of which contains an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group. A third reactive carbonyl group is linked to an oxyester present on C28. Structures I-III show the fragments that would be adducted to a Cys thiol within OxyR by transesterification (oxyester → thioester). (B) ESI/MS of avicin-modified OxyR. Each spectrum illustrates a range of amu of 0-500. The mass of all peaks of intensity ≥20% of the maximum intensity is indicated.

Table 1. MALD1-TOF/MS of avicin-modified OxyR.

| m/z, amu

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residues | Sequence | Cysteine | Modification | Expected | Detected |

| 191-201 | LLMLEDGHCLR | C199 | Control | 1,299.6 | 1,299.86 (5) |

| F094 | 1,299.6 | 1,295.54 (9) | |||

| 1,487.6 | 1,463.72 (100) | ||||

| Avicin D | 1,299.6 | 1,295.82 (15) | |||

| 1,487.6 | 1,463.96 (86) | ||||

| Avicin G | 1,299.6 | ND | |||

| 1,467.6 | 1,463.76 (63) | ||||

Values in parentheses are peak intensities relative to the highest peak for each spectrum. ND, not detected.

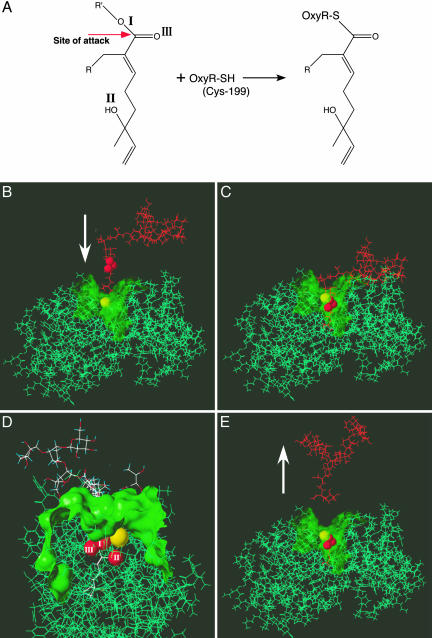

Modification of OxyR Cys-199 is necessary for transcriptional activation by redox-active molecules, but Cys-208 or -180 may also influence activity (23). MALDI-TOF/MS allowed us to identify the avicin-modified cysteine residue. After tryptic digests of avicin-treated OxyR, all of the expected peptides (mass >500) were detected (not shown). The avicin-modified cysteine-containing peptides are listed in Table 1. No avicin-modified peptides contained Cys residues other than Cys-199. Fig. 4A shows the probable reaction scheme that results in a thioester bond between Cys-199 of OxyR and the outer monoterpene of the avicin molecule.

Fig. 4.

Structural basis of the interaction between OxyR and Avicin. (A) Reaction scheme illustrates transesterification that results in the formation of a thioester linkage between Cys-199 of OxyR and the outer monoterpene side chain of avicin. (B-E) Molecular modeling of the interaction between avicin D and (reduced) OxyR reveals (B and C) that avicin D docks within a hydrophilic pocket at the surface of OxyR (as revealed by Connolly surface rendering, shown as translucent green in the region around Cys-199), which results in the close apposition (3.36 Å) of Cys-199 thiol and the reactive carbonyl within the outer monoterpene of avicin D. (D) The thiol of Cys-199 is spaced 2.9 Å from the outer oxygen atom (I) that links the outer monoterpenoid unit, 3.75 Å from the R-group oxygen (II) and 4.44 Å from the carbonyl group oxygen (III). (E) Cleavage of avicin D, coupled to thioesterification, leaves the outer monoterpenoid unit of avicin bound to OxyR. Oxygen atoms within avicin D are shown in space-filling representations with conventional coloring (sulfur, yellow; oxygen, red). Other OxyR groups are shown as green lines, and other avicin D groups are shown in orange in B, C, and E and in conventional coloring in D.

To gain further insight into the structural basis of the interaction between OxyR and avicins, we examined the docking of avicin D to OxyR with molecular modeling (SYBYL; Tripos Associates, St. Louis) (Fig. 4B). Connolly surface rendering (28) of the crystal structure of the reduced form of OxyR (PDB ID code 1I69) reveals that Cys-199 is situated in a hydrophilic pocket of ≈20 Å diameter at the surface of OxyR, which we have shown previously accommodates glutathione disulphide (GSSG) and S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) (23, 29). Docking and energy minimization (30) of OxyR and avicin D result in close apposition (3.36 Å) of Cys-199 thiol in OxyR and the reactive carbonyl in the outer monoterpene side chain of avicin D, which would subserve transesterification.

Discussion

We have identified a previously uncharacterized regulatory modification of cysteine thiol induced by avicins, a family of plant-derived glycosylated pentacyclic terpenoids. Specifically, we have shown that avicins transesterify the single critical regulatory Cys-199 in the bacterial transcription factor OxyR. Thioesters are known to form in a variety of metabolic processes including fatty acid oxidation (31), protein splicing (32), and activation of enzyme intermediates (e.g., ligases). Cys thiols within numerous mammalian proteins are also posttranslationally modified by long-chain fatty acid (predominantly palmitate), which is added enzymatically via thioester → thioester transesterification from an activated acylCoA donor, and which is thought to play a role predominantly in subcellular localization (33). Thioesterification to protein Cys thiol of a small regulatory adduct, a role for thioesterification in transcriptional regulation, and formation of a thioester linkage via transesterification from an oxyester-linked donor are, to our knowledge, unprecedented. Avicinylation of OxyR results in transcriptional activation of the target genes, katG and oxyS. OxyR has provided a model for understanding the ubiquitous influence of NO/redox on cellular function, and it is therefore likely that avicinylation will regulate additional classes of proteins.

Bacterial OxyR shares some similarities with mammalian Nrf2: both regulate the expression of detoxifying enzymes and antioxidant proteins, both contain critical Cys residues that serve sensory and regulatory roles, and both are activated by peroxides. HPI is a functional homolog in bacteria of glutathione peroxidase (GPx), the transcription of which is regulated by Nrf2. Like HPI, GPx protects cells against hydrogen peroxide-induced stress. We have previously shown that Nrf2 is activated by avicins in a DTT-reversible fashion, and it therefore seems likely that these transcriptional effects of avicin are also mediated by thioesterification. Whether the reactive moiety contained in the avicin molecule is found endogenously in higher organisms is an open question.

OxyR can be activated by several redox-related modifications of a single Cys-199 (OxyR-SX), including S-nitrosylation, S-OH, and S-glutathione. These alternatively modified forms of OxyR differ in structure, cooperative properties, and promoter activities (23). We have suggested that alternative modifications provide the basis for both graded and differential responsivity to redox-related signals, including control of unique sets of genes by S-nitrosylation and oxidation. The findings reported here indicate that avicins participate in a reversible thioester linkage to Cys-199, which activates OxyR, thus potentially expanding the redox-based code. It remains to be determined whether thioester linkages mimic the transcriptional effects of oxidation or nitrosylation or generate a distinct transcriptional response. More generally, our results emphasize that metabolites containing electrophilic functional groups might generally subserve redox-based modification of proteins (23).

A variety of plant constituents, many of which are abundant in the diet, contain α,β-unsaturated carbonyl groups (Michael acceptors), which have been shown to react with critical cysteines in target proteins such as in the Nrf2/Keap system (16, 17, 34). These interactions result in irreversible alkylation via formation of a thioether bond. Avicins contain not only Michael acceptor sites but also reactive oxyesters, which participate in transesterification to yield a protein adduct linked by a reversible thioester bond. Thioether and thioester modifications of particular substrates may have different effects on protein function, by analogy to the different posttranslational configurations induced in OxyR by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (23), thereby representing a combinatorial code for redox regulation by plant metabolites. It is tantalizing to speculate that a similar code may operate in mammalian cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Clayton Foundation for Research, the Biomedical Research Foundation, and the Katz Foundation.

Author contributions: V.H., S.-O.K., J.S.S., and J.U.G. designed research; V.H., S.-O.K., and G.N. performed research; V.H., S.-O.K., A.H., J.S.S., and J.U.G. analyzed data; and V.H., S.-O.K., J.S.S., and J.U.G. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: ESI/MS, electrospray ionization MS; HPI, hydroperoxidase I; Nrf2, nuclear factor-erythroid 2 p45-related factor; amu, atomic mass unit.

References

- 1.Stamler, J. S., Lamas, S. & Fang, F. C. (2001) Cell 106, 675-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsumoto, A., Comatas, K. E., Liu, L. & Stamler, J. S. (2003) Science 301, 657-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garban, H. J., Marquez-Garban, D. C., Pietras, R. J. & Ignarro, L. J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 2632-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung, K. K. K., Thomas, B., Li, X., Pletnikova, O., Troncoso, J. C., Marsh, L., Dawson, V. L. & Dawson, T. M. (2004) Science 304, 1328-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hare, J. M. & Stamler, J. S. (2005) J. Clin. Invest. 115, 509-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasukawa, T., Tokunaga, E., Ota, H., Sugita, H., Martyn, J. A. & Kaneki, M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 7511-7518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pawloski, J. R., Hess, D. T. & Stamler, J. S. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 2531-2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall, H. E., Merchant, K. & Stamler, J. S. (2000) FASEB J. 14, 1889-1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delaunay, A., Pflieger, D., Barrault, M. B., Vinh, J. & Toledano, M. B. (2002) Cell 111, 471-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green, J. & Paget, M. S. (2004) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 954-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forman, H. J., Fukuto, J. M. & Torres, M. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. 287, C246-C256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haridas, V., Hanausek, M., Nishimura, G., Soehnge, H., Gaikwad, A., Narog, M., Spears, E., Zoltaszek, R., Walaszek, Z. & Gutterman, J. U. (2004) J. Clin. Invest. 113, 65-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haridas, V., Higuchi, M., Jayatilake, G. S., Bailey, D., Mujoo, K., Blake, M. E., Arntzen, C. J. & Gutterman, J. U. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5821-5826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mujoo, K., Haridas, V., Hoffmann, J. J., Wachter, G. A., Hutter, L. K., Lu, Y., Blake, M. E., Jayatilake, G. S., Bailey, D., Mills, G. B., et al. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 5486-5490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haridas, V., Arntzen, C. & Gutterman, J. U. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 11557-11562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinkova-Kostova, A. T., Holtzclaw, W. D., Cole, R. N., Itoh, K., Wakabayashi, N., Katoh, Y., Yamamoto, M. & Talalay, P. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 11908-11913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakabayashi, N., Dinkova-Kostova, A. T., Holtzclaw, W. D., Kang, M. I., Kobayashi, A., Yamamoto, M., Kensler, T. W. & Talalay P. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 2040-2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Storz, G., Tartaglia, L. A. & Ames, B. N. (1990) Science 248, 189-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng, M., Aslund, F. & Storz, G. (1998) Science 279, 1718-1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hausladen, A., Privalle, C. T., Keng, T., DeAngelo, J. & Stamler, J. S. (1996) Cell 86, 719-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kullik, I., Toledano, M. B., Tartaglia, L. A. & Storz, G. (1995) J. Bacteriol. 177, 1275-1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aslund, F., Zheng, M., Beckwith, J. & Storz, G. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 6161-6165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim, S. O., Merchant, K., Nudelman, R., Beyer, W. F., Keng, T., De Angelo, J., Hausladen, A. & Stamler, J. S. (2002) Cell 109, 383-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stamler, J. S. & Hausladen, A. (1998) Nat. Struct. Biol. 5, 247-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jayatilake, G. S., Freeberg, D. R., Liu, Z., Richheimer, S. L., Blake, M. E., Bailey, D. T., Haridas, V. & Gutterman, J. U. (2003) J. Nat. Prod. 66, 779-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clairborne, A. & Fridovich, I. (1979) Biochemistry 18, 2324-2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Worthington, V. (1993) in Worthington Enzyme Manual: Peroxidase, ed. Worthington, V. (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Freehold, NJ), pp. 293-299.

- 28.Connolly, M. L. (1983) Science 221, 709-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hess, D. T., Matsumoto, A., Kim, S. O., Marshall, H. E. & Stamler, J. S. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 150-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rarey, M., Kramer, B., Lengauer, T. & Klebe, G. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 261, 470-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Genschel, U. (2004) Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 1242-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gogarten, J. P., Senejani, A. G., Zhaxybayeva, O., Olendzenski, L. & Hilario, E. (2002) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56, 263-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dietrich, L. E. & Ungermann, C. (2004) EMBO Rep. 5, 1053-1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Talalay, P. & Fahey, J. W. (2001) J. Nutr. 131, S3027-S3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]