Abstract

Seizure is among the most severe FDA black box warnings of neurotoxicity reported on drug labels. Gaining a better mechanistic understanding of off-targets causative of seizure will improve the identification of potential seizure risks preclinically. In the present study, we evaluated an in vitro panel of 9 investigational (Cav2.1, Cav3.2, GlyRA1, AMPA, HCN1, Kv1.1, Kv7.2/7.3, NaV1.1, Nav1.2) and 2 standard (GABA-A, NMDA) ion channel targets with strong correlative links to seizure, using automated electrophysiology. Each target was assessed with a library of 34 preclinical compounds and 10 approved drugs with known effects of convulsion in vivo and/or in patients. Cav2.1 had the highest frequency of positive hits, 20 compounds with an EC30 or IC30 ≤ 30 µM, and the highest importance score relative to the 11 targets. An additional 35 approved drugs, with categorized low to frequent seizure risk in patients, were evaluated in the Cav2.1 assay. The Cav2.1 assay predicted preclinical compounds to cause convulsion in nonclinical species with a sensitivity of 52% and specificity of 78%, and approved drugs to cause seizure in nonclinical species or in patients with a sensitivity of 48% or 54% and specificity of 71% or 78%, respectively. The integrated panel of 11 ion channel targets predicted preclinical compounds to cause convulsion in nonclinical species with a sensitivity of 68%, specificity of 56%, and accuracy of 65%. This study highlights the utility of expanding the in vitro panel of targets evaluated for seizurogenic activity, in order to reduce compound attrition early on in drug discovery.

Keywords: convulsion, seizure, neurotoxicity, electrophysiology, ion channels, pharmaceuticals

Among the most severe FDA “black box warnings” of neurotoxicity reported on drug labels, seizure/convulsion is listed within the top 4, behind suicidal ideation, sedation, and abuse liability (Walker et al. 2018). Seizures are characterized by abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain. The overall incidence of drug-induced seizures in patients is unknown, but in a retrospective study of 393 drugs approved in Japan between 1999 and 2013, representing a broad spectrum of indications, 26.7% of the drugs had reported an adverse drug reaction (ADR) of seizure or convulsion (Nagayama 2015). Drug categories implicated in seizure include analgesics, anesthetic agents, antibacterial/antiviral agents, antineoplastic agents, central nervous system (CNS) agents, contrast media, cardiovascular agents, immunosuppressants, immunomodulators, and vaccines (Nagayama 2015; Walker et al. 2018).

Drugs that act on the nervous system (CNS penetrating) pose the greatest risk in patients for ADRs of seizure/convulsion, with 35% and 12.7% of seizure-associated drugs in AstraZeneca and UCB Japan studies, respectively, classified as drugs for CNS indications (Easter et al. 2009; Nagayama 2015). Drugs that reduce the seizure threshold can be life-threatening if progressed to status-epilepticus, which occurs in up to 15% of seizure ADRs, depending on drug and patient-related risk factors, and reported to lead to mortality in 2% of status-epilepticus patients (Ruffmann et al. 2006; Nagayama 2015). Therefore, it is important to understand the concordance of clinical seizure findings to nonclinical safety studies, in order to assess the risk as early as possible preclinically. Retrospectively, in the UCB Japan study, only 23.8% of drugs with ADR of seizure/convulsion in patients had concordance with nonclinical safety data (Nagayama 2015).

Proconvulsant effects (myoclonus, severe muscle jerks, or convulsions) may be overlooked in nonclinical safety studies due to inherent limitation in study designs. The ICH S7A Guidance for industry “Safety Pharmacology Studies for Human Pharmaceuticals” recommends use of in Irwin assay (Irwin 1968) or the functional observational battery testing paradigms to assess drug-induced CNS adverse effects in rodents, but the guideline does not address how seizure/convulsion should be investigated in nonclinical safety studies (Moser et al. 1995; Agency EM 2021). These observational testing paradigms do not adequately assess a drug’s seizure potential, as standard behavior endpoints are insufficient to assess seizure, and additionally, continuous video monitoring for convulsion and electroencephalograms to confirm seizure are not routinely included on pre-clinical in vivo studies (Yip et al. 2019). Additional challenges in diagnosing seizure in nonclinical in vivo studies are that not all convulsive-like motor behaviors are attributable to seizure (ie, tremors), and similarly, some seizures may not involve muscular contractions (Kaplan 1996; Scharfman 2007).

In addition to in vivo screening for seizure during preclinical development, compounds can be assessed in vitro for promiscuity against seizurogenic targets early in the discovery stage. To identify off-target interactions, compounds are routinely screened in either binding or functional activity assays, against a select panel of protein targets (receptors, enzymes, ion channels, and transporters) with strong correlation to adverse findings across target organs (Lynch et al. 2017). Of those targets, a small subset has established links to seizure, but a thorough panel has yet to be validated (Easter et al. 2009; Lynch et al. 2017; Rockley et al. 2023). Gaining a better mechanistic understanding of off-targets causative of seizure will improve identification of potential seizure risks preclinically, allowing for more scientifically rigorous in vivo study designs to assess seizure prior to IND submission, and subsequently, lower drug attrition rates related to seizure/convulsion during development.

In the present study, we evaluated a panel of 9 novel ion-channel targets (Cav2.1, Cav3.2, GlyRA1, AMPA, HCN1, Kv1.1, Kv7.2/7.3, NaV1.1, Nav1.2) and 2 standard ion channel targets (GABA-A, NMDA) with strong correlative links to seizure with genetic, in vitro, in vivo, and/or patient derived data. Each target was assessed using a human in vitro functional activity assay with automated electrophysiology and a library of 34 preclinical compounds and 10 approved drugs with known effects of convulsion in vivo and/or patients. Results identified Cav2.1 as having the highest frequency of positive hits (IC30 ≤ 30 µM) and highest importance score relative to the 11 targets. Therefore, an additional 35 approved drugs were evaluated in the Cav2.1 assay. We report here (1) the predictivity of the Cav2.1 assay and the integrated panel of 11 ion channel targets with preclinical compounds and approved drugs to cause convulsion in nonclinical species and/or patients and (2) classification of compound characteristics relative to therapeutic area and preclinical species susceptibility.

Materials and methods

Selection of chemicals

Thirty-four preclinical compounds were selected from Takeda’s internal chemical library and defined as neurotoxic or nonneurotoxic based on the results of single or repeat-dose toxicity studies in rats, mice, dogs, or NHPs. Twenty-five preclinical compounds were classified as neurotoxic because convulsions were observed in at least 1 nonclinical species, and 9 compounds were classified as nonneurotoxic because no convulsions or any pathological changes in the CNS were observed in any of the nonclinical species tested. The compound IDs and intended pharmacological targets are blinded. The 45 approved drugs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Company Ltd (St Louis, Missouri), R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minnesota), or SelleckChem.com (Houston, Texas) and were categorized low to frequent seizure risk in patients (Table S1).

Selection of ion channels

A literature search was preformed using key words (convulsion, seizure, epilepsy) through a number of data bases, including: DisGenet (https://www.disgenet.org/home/), Drugbank (https://go.drugbank.com/), Metacore (https://portal.genego.com/), NCBI SNP (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/), Off-X (https://access.clarivate.com/login?app=safety), OMIM (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim), OpenTarget (https://www.opentargets.org/), and PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The 9 targets were prioritized based on the literature weight of evidence and targets already captured within Takeda’s standard off-target functional activity panel were excluded (Brown et al. 2020; Sameshima et al. 2020).

Ion channel assays

The GABA-A-R antagonist, and NMDA-R A1/2B agonist assays were performed by Eurofins DiscoverX (San Diego, California). These assays are based on Calcium Mobilization. The FLIPR Membrane Potential Assay Kit was used which employed a proprietary fluorescent indicator dye in combination with a quencher to reflect real-time membrane potential changes associated with ion channel activation. The GABA-A (alpha1/beta2/gamma2) Human Ion Channel in stably transfected CHO cells was used for the GABA-A-R antagonist assay. The NMDAR (1A/2B) Human Glutamate (Ionotropic) Ion Channel in stably transfected HEK293 cells was used for the NMDA-R A1/2B agonist assay. GABA was used as an agonist, and Picrotoxin was used as a reference antagonist for the GABA-A-R antagonist assay. L-Glutamic acid was used as a reference agonist in the NMDA-R A1/2B agonist assay. Compounds were tested with 10 concentrations (A half-log dilution from the top concentration, 10 µM).

The GABA binding assays using a radioligand were performed by Axcelead Drug Discovery Partners, Inc. (Japan) or Eurofins Panlabs Discovery Services Taiwan, Ltd (Taiwan). The membrane fraction was prepared by Axcelead Drug Discovery Partners, Inc. for the human GABA binding assay, or prepared from whole brains of male Wistar-derived rats for the rat GABA binding assays. The radioligand was [³H]Ro15-1788 in the human assay and [³H]Muscimol, [³H]Flunitrazepam, or [³H]TBOB in the rat assay. The positive control was Flumazenil for the human assay and 4-Aminobutyric acid, hydrogen diazepam chloride, or picrotoxin for the rat assay. Each compound was tested at 1 and/or 10 µM. The NMDA binding assays using a radioligand were performed by Eurofins Panlabs Discovery Services Taiwan, Ltd (Taiwan). The membrane fraction was prepared from cerebral cortical of male Wistar-derived rats. The radioligand was [³H]CGP-39653, [³H]MDL 105,519 Glycine, or [³H]TCP, and the controls were L-glutamic acid, MDL 105,519, or dizocilpine ((+)-MK-801). Each compound was tested at 10 µM.

The hNav1.1 agonist and antagonist assay, hNav1.2 agonist assay, hKv1.1 antagonist assay, hCav3.2 agonist assay, hHCN1 antagonist assay, and hGlyRα1 antagonist assay were performed by Eurofins Pharma Discovery Services (St Charles, Missouri). The hNav1.1, hNav1.2, hKv1.1, Cav3.2, and hHCN1 assays were conducted using the Qpatch automated Patch Clamp Assay. The vendor performed a voltage-step protocol specific to each channel, which was applied to the cells (HEK293 or CHO-K1) that overexpressed the ion channel. The cells (n ≥ 2) were pulsed to activate or inactivate the ion channel of interest and a single concentration of compound (3, 10, 30 µM) per cell was applied for 5 min and recorded. For the automated patch clamp assays, test compound current amplitude was compared with the positive control or neutral control current amplitude and the percent inhibition or percent activation was provided for each compound at each tested concentration. The list of control compounds specific to each assay is provided in Table S2. The DMSO control was included for all assays. For the GlyRα1 assay, the Ionflux assay was performed per the vendor’s protocol, glycine (activator) and strychnine (inhibitor) were used to establish baseline response. A normalized peak current (Icompound+Glycine/IGlycine) was used to calculate the percent inhibition.

The GluR2 (AMPA), Cav2.1, and KCNQ2/Q3 (Kv7.2/7.3) agonist and antagonist assays were performed by SB drug discovery (Glasgow, UK). The vendor performed automated patch clamp-recordings using the SyncroPatch 384PE with a voltage-step protocol specific to each ion channel that was overexpressed in HEK293 cells. Each compound was tested with 3 concentrations (3, 10, 30 µM). For the AMPA assays (PAM, NAM, agonist), glutamate was used to activate the channel and percent effect was quantified based on 0% effect being equivalent to NAM, 100% being equivalent to glutamate EC50, and >100% was equivalent to PAM effect. The PAM effect was calculated as (Icomp-INoCurr)/(Iref-INoCurr), in which Icomp is the current amplitude at each concentration of compound in the presence of Glutamate at EC50 and Iref is the current at the Glutamate EC50 and INoCurr is the current in the presence of the full block with CNQX. The NAM effect was calculated as (1 − (Iconc − IFB)/(Iref − IFB)), in which Iconc is the current in the presence of the compound + Glutamate EC50, IFB is the current in the presence of the reference channel blocker + Glutamate EC50, and Iref is the current during the control period (Glutamate EC50). For the Cav2.1 and KCNQ2/Q3 assays, pulses were applied to evoke the current, and test compounds were added as a single concentration, followed by a saturating concentration of reference blocker for 1 min. The % inhibition was calculated using the equation(1 − (Iconc − IFB)/(Iref − IFB)), where Iconc is the current in the presence of the compound, IFB is the current in the presence of the reference channel blocker, and Iref is the current during the control period (in the absence of compound).

The IC50 and IC30 were calculated using XLfit software (Version 5.5.0, IDBS, Munich, Germany). Briefly, A, B, C, and D in the equation [fit = (A + ((B − A)/(1 + ((C/x)^D))))] were calculated by curve fitting with the constraint of D > 0, where A = bottom response, B = top response, C = IC50, x = test concentrations, and D = slope factor. Then, IC30 was calculated using the following equation: IC30 = (C/((((B − A)/(30 − A)) − 1)^(1/D))).

Data compilation, extrapolation, and visualizations

The profiles of the 34 preclinical compounds and 45 clinical compounds used in the data analyses are summarized in Table S3. Risk category of nonclinical and clinical seizure for these compounds was assigned based on the review of literature or information from various resources. First, online databases such as SIDER 4.1: Side Effect Resource, PharmaPendium, and Off-X, and the product labels or package inserts for approved compounds were screened for the presence of the risk of seizure or convulsion associated with the compounds. If the information collected from this first step is not sufficient to determine the compound’s risk of seizure, then further search was performed within PubMed to identify relevant publications. Search words “seizure” and “convulsion” were used to identify the relevant literature. A thorough review of the identified articles was performed to assess and categorize the level of risk of seizures for each compound. For clinical seizure risk, the following categories were assigned: “Yes (Frequent)” if a compound is associated with a greater than 1% frequency of seizure or convulsion adverse event; “Yes (Infrequent)” if a compound is associated with a greater than > 0.1% but less than 1% frequency of seizure or convulsion adverse event; “Yes (Rare or No Frequency Information)” if a compound presents with a seizure or convulsion adverse event at a less than 0.1% or unknown frequency; “Low Clinical Seizure Risk” if a compound has a very low risk of seizure or convulsion; and “No Data Available” if a compound does not have data on the risk of clinical seizure or convulsion. For the purpose of data exploration in this article, the compounds were considered to have no clinical seizure risk if they were in “Low Clinical Seizure Risk” category. For nonclinical seizure risk, the following categories were assigned: “Yes” if there is strong evidence (at least one well-designed, industry-led nonclinical tox study) of seizure or convulsion risk of a compound in nonclinical species; “No” if there is weak evidence of seizure or convulsion risk of a compound in nonclinical species; “No Data Available” if a compound does not have data on the risk of seizure or convulsion in nonclinical species. Prior to data exploration, visualization, and/or analyses, missing values in the dataset were reviewed and handled by either removal or imputation based on mean, as appropriate. Visualizations of the data landscape were created using Tableau Desktop software and Matplotlib library in Python v3.10.

Calculation of importance score for ion channels for predictivity of convulsion in nonclinical species with preclinical compounds

Random forest modeling was implemented using the RandomForestClassifier from scikit-learn library in Python v3.10. The model was trained with and without Free Cmax using a fixed random seed for reproducibility. Feature importance scores were calculated, which quantify the impact of the contribution of each feature in the model’s predictive performance. These importance scores are sorted in descending order to identify the most important variables for predicting nonclinical seizure risk.

Performance analysis of Cav2.1 assay for prediction of seizure liability

Histograms and boxplots were constructed to check the distribution of compounds among nonclinical and clinical seizure risk categories against Cav2.1 IC30 values. The plot histogram function from the library matplotlib was utilized. All histograms were created with 20 bins (range of IC30 values for Cav2.1) and the frequency of occurrence (number of compounds) in each bin was plotted on the y axis. The plot_boxplot function from matplotlib library was used to create the boxplots.

A point-biserial correlation analysis was conducted to investigate the relationship of Cav2.1 IC30 values to nonclinical or clinical seizure risk of compounds. The point-biserial correlation coefficient quantifies the strength and direction of the linear relationship between a binary variable and a continuous variable. Here, correlation coefficient (r_pb) was calculated using the pointbiserialr function from the module scipy.stats. Hypothesis testing was performed to assess the statistical significance of the observed correlation coefficient. The P-values associated with the correlation coefficient were computed using the point-biserial correlation test and significance level of 0.05 was chosen to determine statistical significance.

Machine learning-based analysis of predictivity of the ion channel assay for seizure liability

True positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN) values were determined by comparing the Ion channel assay results (“Positive/Yes” or “Negative/No” based on Cav2.1 IC30 values only or on IC30 values across all channels (“integrated ion channel risk”)) and the nonclinical or clinical seizure risk categories (“Yes” or “No”) of the compounds. Using these 2 labels, confusion matrix was generated using “confusion matrix” function from the sklearn.metrics to get TP, F), TN, and FN. Accuracy (defined as (TP + TN)/(TP + TN + FP + FN))—is a metric that measures the proportion of correctly classified instances, sensitivity (defined as TP/(TP + FN)), and specificity (defined as TN/(TN + FP)) values are generated at each threshold value. Confusion matrix was also displayed as heatmap using the “imshow” function from “matplotlib”. In these graphical representations, x axis represents the predicted labels whereas y axis represents the actual labels.

The ROC curves were subsequently generated using a regression model, and the performance summary metrics were calculated to quantify the model’s ability to correctly classify instances of nonclinical or clinical seizure risk. The “roc_curve” function from the module “sklearn.metrics” was utilized to plot the ROC curves with True positive rate (TPR) on the y axis and False positive rate (FPR) on the x axis. Prior to model fitting, categorical variables were converted into a binary variable, where “Yes” was labeled as 1 and “No” as 0. A logistic regression model was fitted using the “Logit” function of “statsmodels” library. The performance of the logistic regression models was used to calculate the TPR and FPR across different thresholds. Finally, the AUC (area under the curve) is computed that represents the overall performance of a model. Furthermore, threshold values were selected to classify the observations into binary outcomes based on predicted probabilities. These threshold values were selected to compute confusion matrix to summarize the performance of logistic regression models.

Survey of marketed drugs associated with seizure and convulsions

Reports of seizure and convulsion were collected using the OFF-X database from Clarivate. All the reports were compiled, excluding “alcoholic seizure”, and studies categorized under “genetic variants” action were excluded from the listed studies to focus on drug related effects and data was exported (date: May 29, 2024). The data was cross examined and grouped into four general modalities: “small molecules”, “biologics”, “cell therapies”, and “oligonucleotides”, in addition to therapies that were not clearly classified by the database under the category “others”. The data were analyzed, and the percentage of compounds per modality and development phase were calculated. Data were not limited by development phase or region, including all the geographic regions available in OFF-X at the search time. The alert phase associated to drug development phases displayed on the figures were grouped as described, “Postmarketing” included “Clinical/Postmarketing” and “Postmarketing” reports; “Phase I” includes “Phase I” and “Phase I/II” reports; “Phase II” includes “Phase II” and “Phase II/III” reports; “Phase III”; “Phase IV”; “Preclinical”; “Target Discovery”.

Seizure data for marketed compounds was sourced from Pharmapendium. Preclinical and clinical data were selected and exported (date: June 5, 2024). The data was analyzed and the number of drugs reporting seizure events in preclinical species vs. human was calculated. The data visualization was generated using Tableau Desktop software.

Results

Establishing the panel of pharmacological targets associated with seizure

To study the molecular mechanisms of drug induced seizure, we sought to expand upon the standard panel of pharmacological ion channel targets that Takeda routinely evaluates in off-target binding and/or functional activity assays that have high correlation to seizure, including gamma-amino-butyric acid A (GABA-A) and glutamate 1A/2B (NMDA-1A/2B) (Waring et al. 2015; Whitebread et al. 2016; Sameshima et al. 2020). Although these targets are evaluated for discovery-stage molecules to predict CNS target organ toxicity, the standard panel is not intended to be comprehensive and is not always able to predict seizure liability. Therefore, 9 investigational pharmacological targets (Cav2.1, CaV3.2, GlyRA1, AMPA, HCN1, Kv1.1, Kv7.2/7.3, NaV1.1, Nav1.2) were prioritized for further characterization in vitro using automated electrophysiology, given the substantial literature linked to seizure and/or convulsion with genetic, in vitro, in vivo, and/or patient-derived data, as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pharmacological targets with substantial literature association to drug-induced seizure.

| Target | Seizure mechanism | Literature linked to seizure/convulsion | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P/Q type voltage-gated calcium channel alpha 1A subunit (Cav2.1, CACNA1A) | Cav2.1 ablation in cortical interneurons selectively impairs fast-spiking basket cells and causes generalized seizures | Genetic | CACNA1A mutation is linked to infantile epileptic encephalopathy-42 and autosomal recessive progressive myoclonic epilepsy | (Fletcher et al. 1996; Saito et al. 2009; Rossignol et al. 2013; Zamponi and Currie 2013; Kim et al. 2015; Epi 2016; Kim et al. 2016; Lv et al. 2017) |

| In vivo |

|

|||

| T-type voltage-gated calcium channel alpha 1H subunit (Cav3.2, CACNA1H) | Cav3.2 activation can promote absence seizures by modulating membrane properties with low-threshold calcium spikes and calcium-dependent potassium currents | Genetic | CACNA1H gain-of-function (GOF) mutations are linked to Childhood Absence Epilepsy 6 and idiopathic generalized epilepsy | (Chen et al. 2003; Heron et al. 2007; Becker et al. 2008; Powell et al. 2009; Tringham et al. 2012; Eckle et al. 2014; Marks et al. 2016) |

| In vitro |

|

|||

| In vivo |

|

|||

| Glycine receptor alpha 1 subunit (GlyRA1, GLRA1) | Loss or reduction of inhibitory signal in motoneurons | Genetic | GLRA1 mutation is linked to hyperekplexia, convulsions, and startle disorders | (Gundlach et al. 1988; Smith 1990; El Idrissi et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2008; Chung et al. 2010; Lecker et al. 2012; Ude and Ambegaonkar 2016; Sadek et al. 2017) |

| In vitro | Tranexamic acid competitively antagonized GlyRA1 in primary cultures of mouse embryonic neurons and induced seizure-like events in mouse coronal neocortical slices | |||

| In vivo |

|

|||

| Clinical |

|

|||

| Glutamate ionotropic receptor α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) type subunit 2 (GluR2, GRIA2) | AMPA receptors are of primary importance in initiating epileptiform discharges | Genetic | Genetics variants of GRIA2 gene are linked to seizures and altered current amplitude | (Sandyk and Gillman 1985; Friedman and Veliskova 1998; Friedman and Koudinov 1999; Hu et al. 2001; Chappell et al. 2002; Huang et al. 2002; Friedman et al. 2003; Faught 2014; Schulze-Bonhage 2015; Mi et al. 2018; Salpietro et al. 2019; Konen et al. 2020) |

| In vivo | Disruption of GluR2 expression or function via genetic and epigenetic modification is associated with higher seizure vulnerability and seizure-induced neuronal injury in mice and rats | |||

| Clinical |

|

|||

| Potassium/sodium hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel 1 (HCN1) | HCN1 channels regulate dendritic intrinsic membrane properties and hence cortical pyramidal cell excitability | Genetic |

|

(Richichi et al. 2008; Huang et al. 2009; Santoro et al. 2010; Nava et al. 2014; Wemhoner et al. 2015) |

| In vitro | HCN1 mRNA expression was reduced by seizure-like events in organotypic rat hippocampal slide cultures by Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptor-mediated Ca2+ influx, and subsequent activation of Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II | |||

| In vivo |

|

|||

| Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily Q, member 2/3 (Kv7.2/7.3, KCNQ2/3) | Blockage of KCNQ2/3 induces membrane depolarization in resting conditions and increases neuronal input resistance and likelihood of action potentials. It is predicted that a 25% decrease in KCNQ2/3 channels can cause epilepsy | Genetic | Mutation in KCNQ gene (loss-of-function or gain-of-function) is linked to benign familial neonatal convulsions, developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, and infantile spasms | (Watanabe et al. 2000; Freibauer and Jones 2018; Kim et al. 2018; Goto et al. 2019; Narahara et al. 2019; Soldovieri et al. 2019; Ikuta et al. 2020) |

| In vitro | Mutations in KCNQ2 gene failed to reduce excitability of caused cell deaths in the rat hippocampal neurons | |||

| In Vivo | Heterozygous mice with reduced KCNQ2 expression were hypersensitive to a seizure-inducing pentylene-tetrazole | |||

| Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily A, member 1 (Kv1.1, KCNA1) | Blockage of Kv1.1 results in a lower voltage threshold for action potential generation, additional action potentials being fired, action potential broadening, and increased neurotransmitter release | Genetic | Loss-of-function mutation in KCNA1 gene is linked to generalized or partial seizures associated to episodic ataxia type-1, severe dyskinesia, and neonatal epileptic encephalopathy | (Rho et al. 1999; Wenzel et al. 2007; Robbins and Tempel 2012; Moore et al. 2014; Gautier and Glasscock 2015; Villa and Combi 2016; Simeone et al. 2018; Dhaibar et al. 2019; Ren et al. 2019; Trosclair et al. 2020; Verdura et al. 2020; Yuan et al. 2020) |

| In vivo | Systemic or neuron-specific knockout of KCNA1 in mice is associated with developmental or spontaneous seizure, and respiratory dysfunction/failure and/or sudden death associated with epilepsy | |||

| Sodium voltage-gated channel, type I, alpha subunit (Nav1.1, SCN1A1) | Antagonism of Nav1.1 and subsequent reduction in sodium currents in inhibitory neurons leads to hyperexcitability of dentate granule and pyramidal neurons which may result in epilepsy | Genetic | Variants of SCN1A1 gene is linked to generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus, type 2, developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 6B (non-Dravet), Dravet syndrome, and familial febrile seizures type 3A | (Martin et al. 2007; Ogiwara et al. 2007; Guo et al. 2008; Oakley et al. 2009; Catterall et al. 2010; Martin et al. 2010; Cao et al. 2012; Cheah et al. 2012; 2013; Ogiwara et al. 2013; Hedrich et al. 2014; Schutte et al. 2014) |

| In vitro | Increased spontaneous thalamocortical and hippocampal network activity was observed in Nav1.1 mutant mouse brain slices | |||

| In vivo | Systemic or neuron-specific knockout of SCN1A1 in mice and Drosophila flies is associated with severe ataxia, seizure phenotype generalized seizures, myoclonic epilepsy, and increased susceptibility to fluoroethyl- or hyperthermia-induced seizure | |||

| Sodium voltage-gated channel, type II, alpha (Nav1.2, SCN2A) | Enhanced function of Nav1.2 increases neuronal excitability | Genetic | Variants of SCN2A gene (gain-of-function) are linked to developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 11, episodic ataxia type 9, and benign familial infantile seizure type 3 | (Ben-Shalom et al. 2017; Cheng et al. 2017; Flor-Hirsch et al. 2018; AlSaif et al. 2019; Kong et al. 2019; Schwarz et al. 2019) |

| In vivo | Systemic or neuron-specific mutation of SCN2A genet in mice was associated with seizures and behavioral abnormalities | |||

Literature for pharmacological targets was categorized by seizure mechanism or genetic, in vitro, or in vivo evidence of seizure or convulsion. Abbreviations: Cav2.1, Cav3.2, GlyRA1, AMPA, HCN1, Kv7.2/7.3, Kv1.1, NaV1.1, Nav1.2.

Evaluation of the panel of pharmacological targets with preclinical compounds and approved drugs

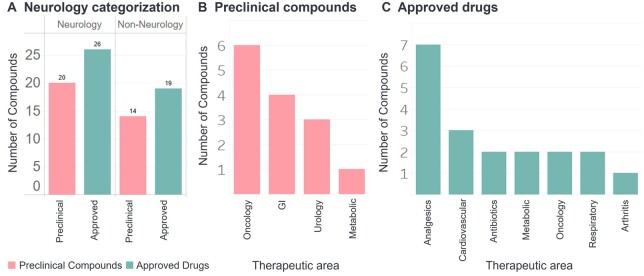

The panel of 9 investigational pharmacological ion channel targets were evaluated with a library of 34 preclinical compounds and 10 approved drugs with known effects of convulsion in vivo or seizure in patients, respectively. The therapeutic area categorization of the 34 preclinical compounds included gastroenterology, metabolic, neurology (CNS penetrating), oncology, and urology; with 20 of the compounds being developed for neurology indications (Fig. 1A and B). The therapeutic area categorization of the 10 approved drugs included analgesic (1), antibiotic (1), cardiovascular (1), neurology (5), and respiratory (2) indications (Fig. 1A and C).

Fig. 1.

Therapeutic area categorization of preclinical compounds and approved drugs. A) Approved drugs and preclinical compounds were categorized as Neurology (CNS acting) or non-neurology. Non-neurology B) preclinical compounds and C) approved drugs were further categorized by therapeutic area.

Table 2 summarizes the side-by-side comparison of the relative number of positive hits in the standard panel of seizure targets (GABA-A, NMDA) to the investigative panel of 9 pharmacological ion channel targets. According to the seizurogenic ion channel activity grading system defined by Rockley et al. (2023), compounds with a response >100 µM have no activity, 30–100 µM have moderate activity, and <30 µM have strong inhibition (high risk) (Rockley et al. 2023). Therefore, in our analysis, compounds were evaluated in a 3-point dose-response curve up to 30 µM (3, 10, 30 µM) in order to predict the highest tier of seizurogenic risk. A positive hit in an individual assay, according to vendor specifications, was a response ≥25% (agonism/activation, antagonist/inhibition) relative to negative control reference data, but to provide a more robust threshold, we completed a confusion matrix analysis of XCY values from XC10 to XC50 that identified XC30 as the most appropriate threshold based on balanced accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity (Table 3).

Table 2.

Number of positive hits on seizurogenic targets.

| Standard targets, positive hits (# (%)) |

Investigational pharmacological targets, positive hits (# (%)) |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seizure (+/−) | GABA-A Ant | NMDA 1A/2B Ag | N | Cav2.1 Ant | Kv1.1 Ant | Nav1.1 Ant | GlyRA Ant | Cav3.2 Ag |

KCN

Q2/Q3 Ant |

AMPA (GLUR2) |

HCN Ant | Nav1.2 Ag | Nav 1.1 Ag | |||

| PAM | NAM | Ag | ||||||||||||||

| Preclinical compounds | + | 2/22 (9.1%) | 0/15 (0%) | 25 | 12 (48%) | 8 (32%) | 5 (20%) | 4 (16%) | 3 (12%) | 2 (8%) | 4 (16%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| − | 0/9 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 9 | 3 (33%) | 2 (22%) | 3 (33%) | 1 (11%) | 1 (11%) | 2 (22%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Approved drugs | + | na | na | 8 | 4 (50%) | 4 (50%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 2 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| − | na | na | 2 | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Total # of positive hits* | na | 2/31 (6.4%) | 0/23 (0%) | 44 | 20 (45%) | 14 (32%) | 12 (27%) | 5 (11%) | 6 (14%) | 6 (14%) | 4 (9.1%) | 2 (4.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

The number (#) and percent (%) of positive hits are described for preclinical and approved drugs with observed convulsion/seizure (+) or no observation (−) for Standard Targets and Investigational Pharmacological Targets. *For the total # of compound positive hits, the standard targets had varying historical data for each target, including 31 compounds evaluated in GABA-A and 23 compounds evaluated in NMDA 1A/2B. Approved drugs were not evaluated in the standard targets. Ag, agonist; Ant, antagonist; na, not applicable; N, total number of compounds; NAM, negative allosteric modulator; PAM, positive allosteric modulator; % hits = # positive hits/total # of compounds.

Table 3.

Confusion matrix analysis of seizure panel and nonclinical seizure risk.

| Endpoints | Threshold |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XC10 < 30 µM | XC20 < 30 µM | XC30 < 30 µM | XC40 < 30 µM | XC50 < 30 µM | |

| TP | 31 | 25 | 20 | 15 | 13 |

| TN | 0 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| FP | 12 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| FN | 0 | 6 | 11 | 16 | 18 |

| Accuracy (%) | 72 | 63 | 60 | 49 | 44 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 100 | 81 | 65 | 48 | 42 |

| Specificity (%) | 0 | 17 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

Summary of accuracy, sensitivity, and, specificity at varying XC values (10 to 50%). XC represents the lowest IC or EC observed in the seizure panel.

Of the 31 preclinical compounds evaluated in the GABA-A antagonist assay, 22 of the 31 compounds had confirmed convulsions in animals, but only 2 of the compounds had positive hits in the GABA antagonist assay (Table 2). A subset of 23 preclinical compounds were further evaluated in the NMDA agonist assay and there were no positive hits. This historical dataset of preclinical compounds in GABA-A and NMDA binding and/or functional activity assays prompted the investigative work in the panel of 9 pharmacological targets. Of the 34 preclinical compounds evaluated in the investigative panel of 9 pharmacological targets, 25 of the 34 compounds had confirmed convulsions in animals, with the highest incidence of positive hits in the Cav2.1 (15 compounds), Kv1.1 (10 compounds), and Nav1.1 (8 compounds) antagonist assays, followed by GlyRA antagonist (5 compounds), Cav3.2 agonist (4 compounds), AMPA PAM (4 compounds), AMPA NAM (2 compounds), and no compounds with positive hits in the HCN antagonist or AMPA, Nav1.1, and Nav1.2 agonist assays (Table 2).

Additionally, 10 approved drugs, with known effects of seizure in patients in 8 of the 10 compounds, were evaluated in the investigative panel of 9 pharmacological targets. The approved drugs had a similarly high incidence of response to the top 3 targets identified with the preclinical compounds, including Cav2.1 (5 compounds), Kv1.1 (4 compounds), and Nav1.1 (4 compounds). Overall, inclusive of the 34 preclinical compounds and 10 approved drugs evaluated (44 compounds total), Cav2.1 had the highest response rate of 45% within the panel of 9 investigational targets, compared with only 6.4% and 0% response rate for GABA and NMDA, respectively. Concentration response data for all targets is included in Table S3.

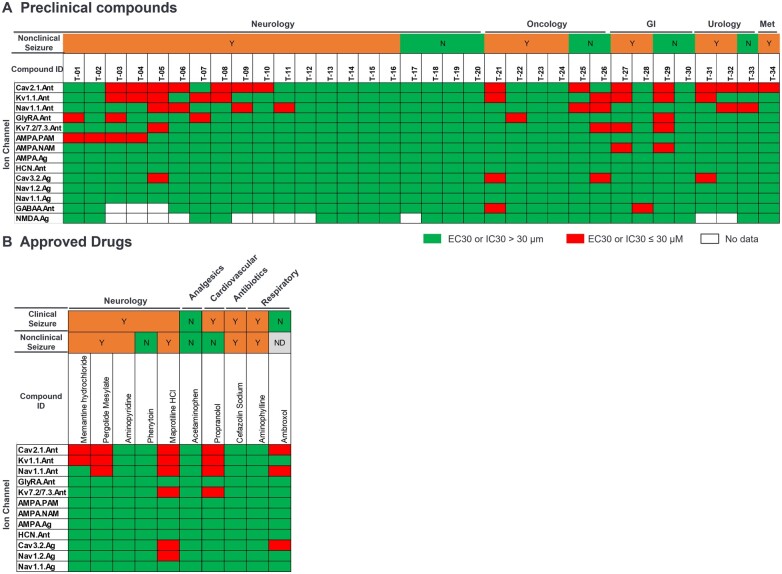

Figure 2 displays a heatmap of positive hits across each ion channel assay with the preclinical compounds and approved drugs. Twenty preclinical compounds (Fig. 2A) and 5 approved drugs (Fig. 2B) demonstrated at least one positive hit (red) against one of the 9 investigative ion channel assays. Additionally, 16 preclinical compounds demonstrated positive hits against two or more of the 11 ion channel assays, inclusive of the 2 standard targets and 9 investigational pharmacological targets.

Fig. 2.

Heatmap of positive hits (EC30 or IC30 ≤ 30 µM) in the 11 individual pharmacological target assays. A) Preclinical compounds and B) approved drugs. Gastrointestinal (GI); metabolic (Met); no data available (ND); no (N); yes (Y).

Expanded evaluation of Cav2.1 performance for predicting seizure liability

The variable importance scores were modeled to determine which variables/features were most predictive of convulsion in nonclinical species with preclinical compounds (Fig. 3). Variables analyzed were individual pharmacological targets, the integrated panel of 11 targets, and free vs total Cmax (highest concentration of a compound in the plasma) that convulsion was observed. In the bar graph, the visualization of the importance scores for each variable shows that Cav2.1 assay had the highest accuracy for predicting convulsion in nonclinical species, relative to all other individual ion channels (Fig. 3). Additionally, free Cmax (unbound fraction of compound in the plasma) was more predictive than total Cmax.

Fig. 3.

Variable importance scores predictive of convulsion in nonclinical species with preclinical compounds. Variables included the 11 individual pharmacological targets (positive hits with EC30 or IC30 ≤ 30 µM), integrated panel of 11 targets, free Cmax (µM), and total Cmax (µM). The model was trained using the RandomForestClassifier from the scikit-learn library. Variable importance scores were calculated and visualized using Seaborn and Pandas libraries in Python. Ag, agonist; Ant, antagonist; NAM, negative allosteric modulator; PAM, positive allosteric modulator.

In order to further interrogate the performance of the Cav2.1 assay, an additional 35 approved drugs were evaluated in the Cav2.1 assay (45 approved drugs total). The therapeutic area categorization of the 39 approved drugs included analgesics, antibiotics, arthritis, cardiovascular, metabolic, oncology, and respiratory indications; with 28 of the approved drugs indicated for neurology disorders (Fig. 1). The performance analysis of the Cav2.1 assay prediction of convulsion in nonclinical species was evaluated for the 34 preclinical compounds and 38 approved drugs (38 of the 45 approved drugs that had nonclinical safety data available), presented in Fig. 4. For preclinical compounds (Fig. 4A–C) and approved drugs (Fig. 4D–F), histograms and boxplots illustrate the frequency of positive hits relative to the distribution of Cav2.1 IC30 values (µM), which suggests that many preclinical compounds and drugs that had convulsion in animals were associated with lower Cav2.1 IC30 values (µM). The ROC curves with performance metrics (Fig. 4C, F, and I) were generated to illustrate the discriminatory ability of the model. The Cav2.1 assay predicted preclinical compounds to cause convulsion in nonclinical species with a sensitivity of 52% and specificity of 77%, and approved drugs to cause convulsion in nonclinical species with a sensitivity of 48% and specificity of 71%. A similar performance analysis was completed for the Cav2.1 assay prediction of seizure in patients for the 45 approved drugs (Fig. 4G–I), resulting in a sensitivity of 53% and specificity of 77%.

Fig. 4.

Performance analysis of Cav2.1 assay for prediction of convulsion in nonclinical species and seizure in patients. Histogram representations depict the distribution of Cav2.1 IC30 (µM) values on the x axis and frequency of occurrence (number of compounds) on the y axis for prediction of convulsion in nonclinical species with (A) preclinical compounds and (D) approved drugs, and for prediction of seizure in patients with (G) approved drugs. Boxplots showcase the distribution of Cav2.1 IC30 (µM) values (y axis) relative to the categorization (yes or no) of the observation of convulsion in nonclinical species with (B) preclinical compounds and (E) approved drugs, and for prediction of seizure in patients with (H) approved drugs. The relationship between Cav2.1 IC30 and nonclinical seizure risk was evaluated using the point-biserial correlation coefficient, with the associated P-values displayed on each boxplot. For both the histogram and boxplots, preclinical compounds with convulsion and drugs with seizure are labeled ‘Yes’ and negative compounds are labeled ‘No’. The ROC curve, generated using a regression model, illustrates the discriminatory ability of the model. False positive rates are plotted on the x axis, whereas true positive rates are plotted on the y axis. The performance summary (sensitivity, specificity, accuracy) is provided for prediction of convulsion in nonclinical species with (C) preclinical compounds and (F) approved drugs, and for prediction of seizure in patients with (I) approved drugs.

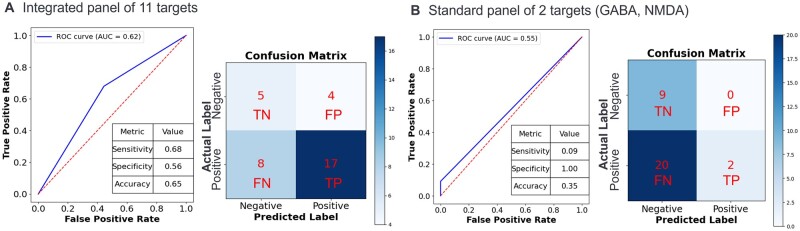

Predictivity of integrated panel of ion channels for seizure liability

For the integrated panel of 11 ion channel targets with preclinical compounds, the performance of the predictive models was evaluated, and ROC curves with performance metrics and confusion matrixes are displayed in Fig. 5. The integrated panel of 11 ion channel targets predicted preclinical compounds to cause convulsion in nonclinical species with a sensitivity of 68%, specificity of 56%, and accuracy of 65% (Fig. 5A). Comparatively, the standard panel of 2 ion channels routinely evaluated (GABA, NMDA) predicted preclinical compounds to cause convulsion in nonclinical species with a sensitivity of 9%, specificity of 100%, and accuracy of 35% (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Predictivity of the integrated panel of 11 ion channels for seizure liability. The performance of the predictive models was evaluated using ROC curves, where the true positive rate (TPR) is plotted on the y axis and the false positive rate (FPR) is plotted on the x axis. The confusion matrix indicates true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), and false negatives (FN) based on the in silico prediction (predicted label, x axis) and in vitro ion channel response (true/actual label, y axis) of negative or positive. The ROC curve, confusion matrix, and performance summary for predicting seizure liability of preclinical compounds in nonclinical species is illustrated for the (A) integrated panel of 11 targets and (B) standard panel of 2 standard targets (GABA-A and NMDA).

Comparison of in vitro IC30 to peripheral free Cmax

For the preclinical compounds (Fig. 6A) and approved drugs (Fig. 6B), the plasma free Cmax of convulsion observed in vivo or therapeutic exposure of seizure observed in patients, respectively, was plotted for comparison to the lowest in vitro EC30 or IC30 value (μM) across the panel of 9 investigative targets. Many of the preclinical compounds and approved drugs with seizure liability displayed an EC30 or IC30 below 10 µM in at least 1 individual ion channel. In general, lower plasma free Cmax values correlated with lower in vitro EC30 or IC30 values.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of peripheral free Cmax in animals or patients to lowest in vitro EC30 or IC30 across the investigative panel of 9 pharmacological targets. The scatterplots depict the relationship between the lowest in vitro EC30 or IC30 (M) across the panel of 9 investigative pharmacological targets and the plasma-free Cmax for (A) preclinical compounds with convulsion in nonclinical species (mouse, rat, dog, or monkey) and (B) therapeutic exposure of approved drugs with seizure in patients. A ‘□’ denotes a neurology indication (CNS) and “X” non-neurology indications (non-CNS). A) Preclinical compounds that had convulsion are denoted as ‘Yes’ and compounds with no observation is denoted as ‘No’, and in (B) clinical seizure score of approved drugs is categorized from low, rare or no information, infrequent, to frequent.

Species susceptibility of preclinical compounds and approved drugs to seizure

In nonclinical safety studies, the clinical observation of convulsion was categorized across species for the preclinical compounds and approved drugs (Fig. 7). For the 34 preclinical compounds, the species with the highest frequency of convulsion were rat > dog > monkey > mouse. For the approved drugs, 38 of the compounds had nonclinical safety data available, with the highest frequency of convulsion observed in rat > dog > mouse > rabbit > hamster.

Fig. 7.

Species susceptibility of preclinical compounds and approved drugs to convulsion/seizure. For each nonclinical species, the number (#) of compounds on the y axis corresponds to the number of individual studies with convulsion observed.

Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated a panel of 9 investigational ion channel targets (Cav2.1, Cav3.2, GlyRA1, AMPA, HCN1, Kv7.2/7.3, Kv1.1, NaV1.1, Nav1.2) with strong correlative links to seizure, and 2 well characterized seizurogenic targets (GABA-A, NMDA), with 34 preclinical compounds and 10 approved drugs with known effects of convulsion in animals and/or seizure in patients. All the compounds evaluated were small molecules, which are known to suffer from promiscuity or lack of selectivity for the intended pharmacological drug target of interest (Takai et al. 2023). For the 34 preclinical compounds, 16 of the compounds demonstrated positive hits against two or more of the 11 ion channel assays associated with seizure.

Given that the nervous system is a complex neural network, it is expected that seizurogenic activity may be resultant from the direct interaction of a compound with multiple ion channel targets (Curtis and Pugsley 2015). Disruption of single or multiple ion channel targets in the brain have the capacity to disrupt the balance between excitatory and inhibitory neural circuits, potentially leading to seizurogenic activity (Scharfman 2007). Realistically, to evaluate a high volume of discovery stage compounds, and to keep associated costs within a reasonable range, a small panel of ion channel targets with highest correlation to seizure would typically be utilized.

Takeda’s small panel of ion channel targets to predict seizure includes GABA-A and NMDA, but relative to the chemistry evaluated, these two targets were shown to be insufficient at identifying seizure liability with the preclinical compounds prior to running in vivo studies, with only 2 of 34 preclinical compounds with a positive hit in GABA-A binding and/or functional activity assays. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the standard panel of these two targets (GABA-A and NMDA) were 9%, 100%, and 35%, respectively. The overall low number of positive hits in the standard panel contributed to the poor sensitivity and but the high specificity was due to there being zero false positives. The low percentage of accuracy confirmed insufficient performance of the standard panel to predict convulsion in vivo with the preclinical compounds. Whereas the assay with the highest positive response rate within the panel of 9 investigational targets was the Cav2.1 antagonist assay, confirmed by variable importance scores. The Cav2.1 assay predicted preclinical compounds to cause convulsion in nonclinical species with a sensitivity of 52% and specificity of 77%, and approved drugs to cause convulsion in nonclinical species with a sensitivity of 48% and specificity of 71%. A similar performance analysis was completed for the Cav2.1 assay prediction of seizure in patients for the 45 approved drugs, resulting in a sensitivity of 53% and specificity of 77%. Therefore, including the Cav2.1 assay, along with GABA-A and NMDA, will improve in vitro predictive modeling of seizure liability. Discovery stage compounds that have positive hits in these ion channels can be rank ordered and prioritized appropriately, relative to the overall risk-benefit profile of the molecule.

One consideration with prioritization relative to in vitro concentrations, is that similar exposures may not be achieved in discovery stage animal studies to identify seizure liability in vivo. For the preclinical compounds, 25 had convulsion observed in animal studies, and 9 structural analogs from the same chemical series were negative for convulsion. Four of the negative structural analogs had positive hits in the panel of 9 investigational targets, and 3 of those 4 analogs were also positive in the human 3D neuronal spheroid assay, which used calcium imaging to correlate to seizurogenic response (Wang et al. 2022). Given the positive results of these 3 analogs across multiple in vitro assays, it is likely these compounds have the risk of seizure liability as well. The negative observations in animal studies (rat, dogs, and/or monkeys) could be due to lack of high enough exposure (Cmax) in the animals (2 of the 3 compounds were oncology targets and dosed at low concentrations). This was further emphasized by the results that total and free plasma Cmax were shown to be the most important factors in predicting seizure liability in vivo (Fig. 3), highlighting that the seizure liability of compounds should be considered in the context of exposure. Other contributing factors of discordance between in vitro and in vivo may include differences in peripheral vs brain pharmacokinetics and compartmental protein binding (Kpuu), infrequent monitoring of the animals, differences in receptor kinetics (on/off rates) between in vitro and in vivo, potential for synergistic effects of compounds modulating multiple ion channel targets in vivo, or seizure not resulting in convulsive-like motor behaviors, to name a few.

There were also 7 preclinical compounds that had convulsions observed in animals but had no positive hits against any of the 11 ion channels. The lack of concordance between in vitro and in vivo could be due to the limited number of pharmacological targets evaluated, lack of metabolic potential of the in vitro assays, or secondary mechanisms related to overall health of the animal (diminished renal clearance, hypoxia, reduced oxygen carriage, lack of energy, hypotension, disturbances of glucose, perturbations in electrolyte metabolism, or systemic inflammation lowering seizure threshold) (Delanty et al. 1998; Curtis and Pugsley 2015; Nagayama 2015). In regard to limitations on the number of targets evaluated, of the 9 investigational targets evaluated, 4 targets (Nav1.1, Nav1.2, Kv7.2/7.3, Kv1.1) overlapped with the ion channel in vitro seizure screening panel conducted by Rockley et al. (2023), which identified positive hits (IC50 < 30 µM) across the channels with the nine approved drugs they had evaluated (Rockley et al. 2023). In our study, the 34 preclinical compounds and 10 approved drugs also had a high frequency of hits in the Nav1.1 and Kv1.1 antagonist assays, with Nav1.1 having the second highest variable importance score, relative to Cav2.1.

We also sought to classify compound characteristics of the 34 preclinical compounds and 45 approved drugs, relative to therapeutic area and preclinical species susceptibility. Both preclinical compounds and approved drugs had the highest incidence of proconvulsive effects with neuroactive drugs, comparatively across therapeutic areas. In regard to the incidence of convulsion in preclinical species, both preclinical compounds and approved drugs had the highest incidence of seizure in rat > dog. Our results were slightly different from an IQ DruSafe consortium initiative survey across 11 companies (80 unique compounds) that ranked the sensitivity of nonclinical species to convulsion and found the highest incidence of convulsion was observed in dog > NHP > rat > mouse (DaSilva et al. 2020). These differences may be attributable to the number of studies run across species.

Data presented in several publications have classified compound characteristics of seizurogenic drugs, including incidence of seizure in patients across 393 approved drugs in Japan, categorization of drug by therapeutic area, and concordance of seizure in patients to observation of convulsion in nonclinical safety studies (Ruffmann et al. 2006; Nagayama 2015; Authier et al. 2016; Walker et al. 2018). We expanded upon this characterization by collecting 6112 safety alerts associated with seizure and convulsion across 979 drugs, compiled within the OFF-X (Clarivate) and Pharmapendium databases, and evaluated characteristics of modalities (Fig. 8A), development phase (Fig. 8B), and relative concordance of clinical to nonclinical species of seizure (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Overview of 979 drugs reporting seizure categorized by drug modality, development phase, and species. According to the OFF-X database, 979 drugs were associated with seizure, generating 6112 reported cases. A) Percentage of compounds associated to seizure reports categorized by therapeutic modality. B) Percentage of compounds associated to seizure across drug development phase. C) Percentage of marketed compounds reporting seizure events within regulatory documents, categorized across preclinical species and human.

In a comparison of seizure incidence across modalities, the highest incidence (% of compounds) of safety alerts was associated with small molecules (66.2%), cell therapy (5%), oligonucleotides (2.5%), and 15% (other, mixed modalities) (Fig. 8A). It is important to note that the database consists of cumulative data, with small molecules overly represented, given the higher quantity of data available relative to newer modalities such as cell therapy or oligonucleotides with a smaller set of data available. Relative to phases of drug development, the highest incidence of seizure reports was in post-marketing (44.6%), clinical development (Phase I to IV) (36%), and preclinical (12.6%), which highlights a gap in the prediction of seizure events during preclinical stages (Fig. 8B). In a review of data for just post-marketed drugs, the incidence of adverse events of seizure in patients is 86% of the drugs, whereas only 38% of those drugs had reports of convulsion or seizure in nonclinical studies (Fig. 8C). According to this analysis, there is a considerable gap between preclinical detection of seizure and its occurrence in human subjects, suggesting that preclinical prediction could be improved by alternatives methods such as in vitro models.

Overall, our data have identified the Cav2.1 antagonist assay as a predictive assay to enhance early in vitro assessment of seizure liability in drug candidates. Including the Cav2.1 assay as a standard electrophysiological screen in the early discovery phase of drug development may help to identify compounds at risk of causing an imbalance of neuronal excitation-inhibition. This will help to aid in assessing the risk-benefit profile and rank-ordering of compounds for progression, trigger evaluation with more complex in vitro systems, and/or enable increased monitoring for CNS effects on in vivo studies to further characterize seizure liability. Together, this approach will help to reduce later-stage drug attrition due to seizure liability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jodi Goodwin and Matthew Wagoner for their critical review of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jennifer D Cohen, Drug Safety Research & Evaluation, Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc, San Diego, CA 92121-1964, United States.

Dahea You, Drug Safety Research & Evaluation, Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc, San Diego, CA 92121-1964, United States.

Ashok K Sharma, Drug Safety Research & Evaluation, Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc, San Diego, CA 92121-1964, United States.

Takafumi Takai, Drug Safety Research & Evaluation, Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc, San Diego, CA 92121-1964, United States.

Hideto Hara, Drug Safety Research & Evaluation, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Fujisawa, Kanagawa 251-8555, Japan.

Vicencia T Sales, Drug Safety Research & Evaluation, Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc, Cambridge, MA 02139, United States.

Tomoya Yukawa, Drug Safety Research & Evaluation, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Fujisawa, Kanagawa 251-8555, Japan.

Beibei Cai, Drug Safety Research & Evaluation, Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc, San Diego, CA 92121-1964, United States.

Author contributions

Jennifer D. Cohen and Dahea You contributed equally to this study.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Toxicological Sciences online.

Funding

This study was sponsored and conducted by Takeda Development Center Americas.

Conflicts of interest. This study was funded and conducted by Takeda Development Center Americas. The authors Jennifer D. Cohen, Dahea You, Ashok K. Sharma, Takafumi Takai, Hideto Hara, Vicencia T. Sales, Tomoya Yukawa, and Beibei Cai acknowledge that they are employed by and own stock in Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

References

- Agency EM. 2021. ICH Topic S7A. Safety pharmacology studies for human pharmaceuticals. Note for guidance on safety pharmacology studies for human pharmaceuticals. Cpmp/ich/539/00.

- AlSaif S, Umair M, Alfadhel M. 2019. Biallelic SCN2A gene mutation causing early infantile epileptic encephalopathy: case report and review. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 11:1179573519849938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Authier S, Arezzo J, Delatte MS, Kallman MJ, Markgraf C, Paquette D, Pugsley MK, Ratcliffe S, Redfern WS, Stevens J, et al. 2016. Safety pharmacology investigations on the nervous system: an industry survey. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 81:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker AJ, Pitsch J, Sochivko D, Opitz T, Staniek M, Chen CC, Campbell KP, Schoch S, Yaari Y, Beck H. 2008. Transcriptional upregulation of Cav3.2 mediates epileptogenesis in the pilocarpine model of epilepsy. J Neurosci. 28:13341–13353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shalom R, Keeshen CM, Berrios KN, An JY, Sanders SJ, Bender KJ. 2017. Opposing effects on Na(v)1.2 function underlie differences between SCN2A variants observed in individuals with autism spectrum disorder or infantile seizures. Biol Psychiatry. 82:224–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DG, Smith GF, Wobst HJ. 2020. Promiscuity of in vitro secondary pharmacology assays and implications for lead optimization strategies. J Med Chem. 63:6251–6275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao D, Ohtani H, Ogiwara I, Ohtani S, Takahashi Y, Yamakawa K, Inoue Y. 2012. Efficacy of stiripentol in hyperthermia-induced seizures in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. Epilepsia. 53:1140–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Kalume F, Oakley JC. 2010. Nav1.1 channels and epilepsy. J Physiol. 588:1849–1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell AS, Sander JW, Brodie MJ, Chadwick D, Lledo A, Zhang D, Bjerke J, Kiesler GM, Arroyo S. 2002. A crossover, add-on trial of talampanel in patients with refractory partial seizures. Neurology. 58:1680–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah CS, Westenbroek RE, Roden WH, Kalume F, Oakley JC, Jansen LA, Catterall WA. 2013. Correlations in timing of sodium channel expression, epilepsy, and sudden death in Dravet syndrome. Channels (Austin). 7:468–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah CS, Yu FH, Westenbroek RE, Kalume FK, Oakley JC, Potter GB, Rubenstein JL, Catterall WA. 2012. Specific deletion of Nav1.1 sodium channels in inhibitory interneurons causes seizures and premature death in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109:14646–14651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Lu J, Pan H, Zhang Y, Wu H, Xu K, Liu X, Jiang Y, Bao X, Yao Z, et al. 2003. Association between genetic variation of CACNA1H and childhood absence epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 54:239–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Zhang L, Huang X, Pei Y, Fan M, Xu L, Gao W, Tang W. 2017. De novo SCN2A mutation in a Chinese infant with severe early-onset epileptic encephalopathy, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and adrenal hypofunction. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 10:10358–10362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SK, Vanbellinghen JF, Mullins JG, Robinson A, Hantke J, Hammond CL, Gilbert DF, Freilinger M, Ryan M, Kruer MC, et al. 2010. Pathophysiological mechanisms of dominant and recessive glra1 mutations in hyperekplexia. J Neurosci. 30:9612–9620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Pugsley MK. 2015. Principles of safety pharmacology. 1st ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. Imprint: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- DaSilva JK, Breidenbach L, Deats T, Li D, Treinen K, Dinklo T, Kervyn S, Teuns G, Traebert M, Hempel K. 2020. Reprint of: nonclinical species sensitivity to convulsions: an IQ DruSafe consortium working group initiative. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 105:106919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delanty N, Vaughan CJ, French JA. 1998. Medical causes of seizures. Lancet. 352:383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaibar H, Gautier NM, Chernyshev OY, Dominic P, Glasscock E. 2019. Cardiorespiratory profiling reveals primary breathing dysfunction in KCNA1-null mice: implications for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis. 127:502–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easter A, Bell ME, Damewood JR Jr, Redfern WS, Valentin JP, Winter MJ, Fonck C, Bialecki RA. 2009. Approaches to seizure risk assessment in preclinical drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 14:876–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckle VS, Shcheglovitov A, Vitko I, Dey D, Yap CC, Winckler B, Perez-Reyes E. 2014. Mechanisms by which a CACNA1H mutation in epilepsy patients increases seizure susceptibility. J Physiol. 592:795–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Idrissi A, Messing J, Scalia J, Trenkner E. 2003. Prevention of epileptic seizures by taurine. Adv Exp Med Biol. 526:515–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epi KC. 2016. De novo mutations in SLC1A2 and CACNA1A are important causes of epileptic encephalopathies. Am J Hum Genet. 99:287–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faught E. 2014. BGG492 (selurampanel), an AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist drug for epilepsy. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 23:107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher CF, Lutz CM, O'Sullivan TN, Shaughnessy JD Jr, Hawkes R, Frankel WN, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. 1996. Absence epilepsy in tottering mutant mice is associated with calcium channel defects. Cell. 87:607–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor-Hirsch H, Heyman E, Livneh A, Reish O, Watemberg N, Litmanovits I, Ben Sason Lilli A, Lev D, Lerman Sagie T, Bassan H. 2018. Lacosamide for SCN2A-related intractable neonatal and infantile seizures. Epileptic Disord. 20:440–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freibauer A, Jones K. 2018. KCNQ2 mutation in an infant with encephalopathy of infancy with migrating focal seizures. Epileptic Disord. 20:541–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LK, Koudinov AR. 1999. Unilateral GluR2(b) hippocampal knockdown: a novel partial seizure model in the developing rat. J Neurosci. 19:9412–9425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LK, Veliskova J. 1998. GluR2 hippocampal knockdown reveals developmental regulation of epileptogenicity and neurodegeneration. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 61:224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LK, Veliskova J, Kaur J, Magrys BW, Liu H. 2003. GluR2(b) knockdown accelerates Ca3 injury after kainate seizures. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 62:733–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier NM, Glasscock E. 2015. Spontaneous seizures in kcna1-null mice lacking voltage-gated Kv1.1 channels activate Fos expression in select limbic circuits. J Neurochem. 135:157–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto A, Ishii A, Shibata M, Ihara Y, Cooper EC, Hirose S. 2019. Characteristics of KCNQ2 variants causing either benign neonatal epilepsy or developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. Epilepsia. 60:1870–1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundlach AL, Dodd PR, Grabara CS, Watson WE, Johnston GA, Harper PA, Dennis JA, Healy PJ. 1988. Deficit of spinal cord glycine/strychnine receptors in inherited myoclonus of Poll Hereford calves. Science. 241:1807–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F, Yu N, Cai JQ, Quinn T, Zong ZH, Zeng YJ, Hao LY. 2008. Voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.1, Nav1.3 and Beta1 subunit were up-regulated in the hippocampus of spontaneously epileptic rat. Brain Res Bull. 75:179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich UB, Liautard C, Kirschenbaum D, Pofahl M, Lavigne J, Liu Y, Theiss S, Slotta J, Escayg A, Dihne M, et al. 2014. Impaired action potential initiation in GABAergic interneurons causes hyperexcitable networks in an epileptic mouse model carrying a human Na(v)1.1 mutation. J Neurosci. 34:14874–14889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron SE, Khosravani H, Varela D, Bladen C, Williams TC, Newman MR, Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF, Mulley JC, Zamponi GW. 2007. Extended spectrum of idiopathic generalized epilepsies associated with CACNA1H functional variants. Ann Neurol. 62:560–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu RQ, Cortez MA, Man HY, Roder J, Jia Z, Wang YT, Snead OC. 3rd. 2001. Gamma-hydroxybutyric acid-induced absence seizures in Glur2 null mutant mice. Brain Res. 897:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Doherty JJ, Dingledine R. 2002. Altered histone acetylation at glutamate receptor 2 and brain-derived neurotrophic factor genes is an early event triggered by status epilepticus. J Neurosci. 22:8422–8428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Walker MC, Shah MM. 2009. Loss of dendritic HCN1 subunits enhances cortical excitability and epileptogenesis. J Neurosci. 29:10979–10988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikuta Y, Asai H, Kawaguchi T, Akiyama S, Hayashi K, Oba K, Sumita T, Katori T, Kato M. 2020. kcnq2-related epilepsy associated with neonatal seizures, febrile seizures and mild developmental delays. No to Hattatsu. 52:26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PW. 1996. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Semin Neurol. 16:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EC, Zhang J, Pang W, Wang S, Lee KY, Cavaretta JP, Walters J, Procko E, Tsai NP, Chung HJ. 2018. Reduced axonal surface expression and phosphoinositide sensitivity in K(v)7 channels disrupts their function to inhibit neuronal excitability in KCNQ2 epileptic encephalopathy. Neurobiol Dis. 118:76–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TY, Maki T, Zhou Y, Sakai K, Mizuno Y, Ishikawa A, Tanaka R, Niimi K, Li W, Nagano N, et al. 2015. Absence-like seizures and their pharmacological profile in tottering-6j mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 463:148–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TY, Niimi K, Takahashi E. 2016. Protein expression pattern in cerebellum of Cav2.1 mutant, tottering-6j mice. Exp Anim. 65:207–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konen LM, Wright AL, Royle GA, Morris GP, Lau BK, Seow PW, Zinn R, Milham LT, Vaughan CW, Vissel B. 2020. A new mouse line with reduced Glua2 Q/R site RNA editing exhibits loss of dendritic spines, hippocampal CA1-neuron loss, learning and memory impairments and NMDA receptor-independent seizure vulnerability. Mol Brain. 13:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y, Yan K, Hu L, Wang M, Dong X, Lu Y, Wu B, Wang H, Yang L, Zhou W. 2019. Data on mutations and clinical features in SCN1A or SCN2A gene. Data Brief. 22:492–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecker I, Wang DS, Romaschin AD, Peterson M, Mazer CD, Orser BA. 2012. Tranexamic acid concentrations associated with human seizures inhibit glycine receptors. J Clin Invest. 122:4654–4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Y, Wang Z, Liu C, Cui L. 2017. Identification of a novel CACNA1A mutation in a Chinese family with autosomal recessive progressive myoclonic epilepsy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 13:2631–2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JJ 3rd, Van Vleet TR, Mittelstadt SW, Blomme EAG. 2017. Potential functional and pathological side effects related to off-target pharmacological activity. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 87:108–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks WN, Cain SM, Snutch TP, Howland JG. 2016. The t-type calcium channel antagonist z944 rescues impairments in crossmodal and visual recognition memory in genetic absence epilepsy rats from Strasbourg. Neurobiol Dis. 94:106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MS, Dutt K, Papale LA, Dube CM, Dutton SB, de Haan G, Shankar A, Tufik S, Meisler MH, Baram TZ, et al. 2010. Altered function of the scn1a voltage-gated sodium channel leads to gamma-aminobutyric acid-ergic (GABAergic) interneuron abnormalities. J Biol Chem. 285:9823–9834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MS, Tang B, Papale LA, Yu FH, Catterall WA, Escayg A. 2007. The voltage-gated sodium channel SCN8A is a genetic modifier of severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Hum Mol Genet. 16:2892–2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi Q, Yao G, Zhang GY, Zhang J, Wang J, Zhao P, Liu J. 2018. Disruption of GluR2/GAPDH complex interaction by TAT-GluR2(NT1-3-2) peptide protects against neuronal death induced by epilepsy. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 48:460–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BM, Jerry Jou C, Tatalovic M, Kaufman ES, Kline DD, Kunze DL. 2014. The Kv1.1 null mouse, a model of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). Epilepsia. 55:1808–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser VC, Cheek BM, MacPhail RC. 1995. A multidisciplinary approach to toxicological screening: III. Neurobehavioral toxicity. J Toxicol Environ Health. 45:173–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama T. 2015. Adverse drug reactions for medicine newly approved in Japan from 1999 to 2013: syncope/loss of consciousness and seizures/convulsions. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 72:572–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narahara S, Fukasawa T, Kubota T, Hattori T, Kato Y, Negoro T, Asai H, Kato M. 2019. Abnormal neonatal movements followed by infantile spasms caused by the recurrent kcnq2 gain-of-function variant. No to Hattatsu. 51:386–389. [Google Scholar]

- Nava C, Dalle C, Rastetter A, Striano P, de Kovel CG, Nabbout R, Cances C, Ville D, Brilstra EH, Gobbi G, et al. ; EuroEPINOMICS RES Consortium. 2014. De novo mutations in HCN1 cause early infantile epileptic encephalopathy. Nat Genet. 46:640–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley JC, Kalume F, Yu FH, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. 2009. Temperature- and age-dependent seizures in a mouse model of severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 106:3994–3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogiwara I, Iwasato T, Miyamoto H, Iwata R, Yamagata T, Mazaki E, Yanagawa Y, Tamamaki N, Hensch TK, Itohara S, et al. 2013. Nav1.1 haploinsufficiency in excitatory neurons ameliorates seizure-associated sudden death in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 22:4784–4804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogiwara I, Miyamoto H, Morita N, Atapour N, Mazaki E, Inoue I, Takeuchi T, Itohara S, Yanagawa Y, Obata K, et al. 2007. Nav1.1 localizes to axons of parvalbumin-positive inhibitory interneurons: a circuit basis for epileptic seizures in mice carrying an SCN1A gene mutation. J Neurosci. 27:5903–5914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell KL, Cain SM, Ng C, Sirdesai S, David LS, Kyi M, Garcia E, Tyson JR, Reid CA, Bahlo M, et al. 2009. A Cav3.2 T-type calcium channel point mutation has splice-variant-specific effects on function and segregates with seizure expression in a polygenic rat model of absence epilepsy. J Neurosci. 29:371–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y, Chang J, Li C, Jia C, Li P, Wang Y, Chu XP. 2019. The effects of ketogenic diet treatment in KCNA1-null mouse, a model of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Front Neurol. 10:744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho JM, Szot P, Tempel BL, Schwartzkroin PA. 1999. Developmental seizure susceptibility of kv1.1 potassium channel knockout mice. Dev Neurosci. 21:320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richichi C, Brewster AL, Bender RA, Simeone TA, Zha Q, Yin HZ, Weiss JH, Baram TZ. 2008. Mechanisms of seizure-induced ‘transcriptional channelopathy’ of hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide gated (HCN) channels. Neurobiol Dis. 29:297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins CA, Tempel BL. 2012. Kv1.1 and kv1.2: similar channels, different seizure models. Epilepsia. 53:134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockley K, Roberts R, Jennings H, Jones K, Davis M, Levesque P, Morton M. 2023. An integrated approach for early in vitro seizure prediction utilizing hiPSC neurons and human ion channel assays. Toxicol Sci. 196:126–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol E, Kruglikov I, van den Maagdenberg AM, Rudy B, Fishell G. 2013. Cav 2.1 ablation in cortical interneurons selectively impairs fast-spiking basket cells and causes generalized seizures. Ann Neurol. 74:209–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffmann C, Bogliun G, Beghi E. 2006. Epileptogenic drugs: a systematic review. Expert Rev Neurother. 6:575–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadek B, Oz M, Nurulain SM, Jayaprakash P, Latacz G, Kieć-Kononowicz K, Szymańska E. 2017. Phenylalanine derivatives with modulating effects on human alpha1-glycine receptors and anticonvulsant activity in strychnine-induced seizure model in male adult rats. Epilepsy Res. 138:124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H, Okada M, Miki T, Wakamori M, Futatsugi A, Mori Y, Mikoshiba K, Suzuki N. 2009. Knockdown of Cav2.1 calcium channels is sufficient to induce neurological disorders observed in natural occurring CACNA1A mutants in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 390:1029–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salpietro V, Dixon CL, Guo H, Bello OD, Vandrovcova J, Efthymiou S, Maroofian R, Heimer G, Burglen L, Valence S, et al. ; SYNAPS Study Group. 2019. AMPA receptor GluA2 subunit defects are a cause of neurodevelopmental disorders. Nat Commun. 10:3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameshima T, Yukawa T, Hirozane Y, Yoshikawa M, Katoh T, Hara H, Yogo T, Miyahisa I, Okuda T, Miyamoto M, et al. 2020. Small-scale panel comprising diverse gene family targets to evaluate compound promiscuity. Chem Res Toxicol. 33:154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandyk R, Gillman MA. 1985. Piracetam causes confusion in a patient with temporal lobe epilepsy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 33:305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro B, Lee JY, Englot DJ, Gildersleeve S, Piskorowski RA, Siegelbaum SA, Winawer MR, Blumenfeld H. 2010. Increased seizure severity and seizure-related death in mice lacking HCN1 channels. Epilepsia. 51:1624–1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE. 2007. The neurobiology of epilepsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 7:348–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Bonhage A. 2015. Perampanel for epilepsy with partial-onset seizures: a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 11:1329–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte RJ, Schutte SS, Algara J, Barragan EV, Gilligan J, Staber C, Savva YA, Smith MA, Reenan R, O'Dowd DK. 2014. Knock-in model of Dravet syndrome reveals a constitutive and conditional reduction in sodium current. J Neurophysiol. 112:903–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N, Bast T, Gaily E, Golla G, Gorman KM, Griffiths LR, Hahn A, Hukin J, King M, Korff C, et al. 2019. Clinical and genetic spectrum of scn2a-associated episodic ataxia. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 23:438–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone KA, Hallgren J, Bockman CS, Aggarwal A, Kansal V, Netzel L, Iyer SH, Matthews SA, Deodhar M, Oldenburg PJ, et al. 2018. Respiratory dysfunction progresses with age in KCNA1-null mice, a model of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 59:345–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BA. 1990. Strychnine poisoning. J Emerg Med. 8:321–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldovieri MV, Ambrosino P, Mosca I, Miceli F, Franco C, Canzoniero LMT, Kline-Fath B, Cooper EC, Venkatesan C, Taglialatela M. 2019. Epileptic encephalopathy in a patient with a novel variant in the Kv7.2 S2 transmembrane segment: clinical, genetic, and functional features. Int J Mol Sci. 20:3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai T, Jeffy BD, Prabhu S, Cohen JD. 2023. Retrospective analysis of chemical structure-based in silico prediction of primary drug target and off-targets. Comput Toxicol. 26:100273. [Google Scholar]

- Tringham E, Powell KL, Cain SM, Kuplast K, Mezeyova J, Weerapura M, Eduljee C, Jiang X, Smith P, Morrison JL, et al. 2012. T-type calcium channel blockers that attenuate thalamic burst firing and suppress absence seizures. Sci Transl Med. 4:121ra19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]