Abstract

Background

Preterm infants may experience many health and developmental issues, which continue even after discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit. Once home, the mother, as a non-professional and the primary caregiver will be responsible for the essential care of her preterm infant.

Purpose

Understanding the take care ability in mothers with preterm infants.

Methods

The content analysis method was used. The data were collected using in-depth and semi-structured interviews from April 2021 to February 2022. Eleven mothers, two fathers, two grandmothers, one neonatal nurse, and two neonatologists with a mean age of 36.05 ± 10.88 years were selected using purposeful and snowballing sampling in Tehran, Iran. Allocating adequate time for data collection, gathering data through different methods, peer checking by two qualitative researchers, long interaction with the settings, maximum variation sampling, appropriate quotations, and showing the range of facts fairly and honestly were considered to ensure the trustworthiness of this study. The data were analyzed through Lindgren et al.’s approach using MAXQDA software.

Results

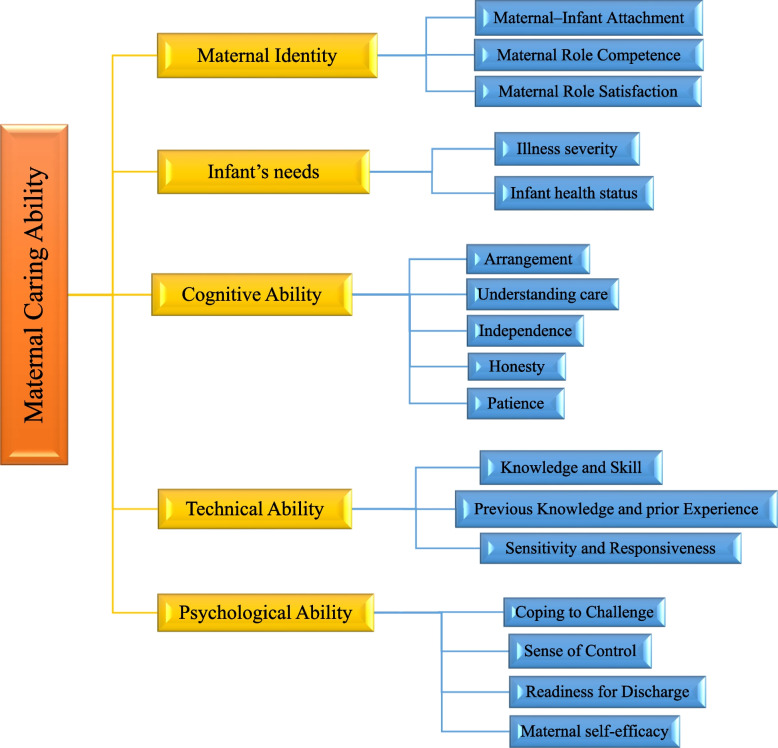

Based on the findings and participants’ experiences in 18 deep interviews, the mothers with desirable care ability have adequate ability as described by 17 subcategories and are categorized into five dimensions. The care ability of the mothers of preterm infants upon neonatal intensive care unit discharge consisted of five categories including maternal identity, infant’s needs, cognitive ability, technical ability, and psychological ability.

Implications for practice and research

In the mothers of preterm infants, maternal identity and the infant’s needs are antecedents of the care ability concept. The care ability of the mothers with preterm infants is distinct from those of other caregivers. This is a multi-dimensional concept and trait related to maternal cognitive ability, technical ability, and maternal psychological ability. Professional neonatal nurses should assess their care ability from multiple perspectives: cognitive, technical, and psychological abilities. They should be considered in designing empowerment and engagement programs for the improvement of the care ability of the mothers of preterm infants. Both mothers and professional neonatal nurses should take responsibility for improving the mothers' ability to take care of their preterm infants.

Keywords: Caring Ability, Mother, Preterm, Infant, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

Background and significance

When the neonate is born before 259 days after conception it is considered a preterm birth. Preterm birth is often an unexpected event for women [1] and infants, who are born preterm, often need neonatal intensive care to survive [2, 3]. They are often separated from their mother. Also preterm birth and hospitalization places stress on the parents [4, 5]. The physical environment, appearance and behavior of the infant and changing parental roles are all sources of stress for parents of preterm infants [6, 7]. They are concerned about medical consequences and even potential death [8, 9]. Therefore, the infant’s hospitalization in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is a crisis for the parents [10].

Mothers of preterm infants experience unique anxiety and often cannot focus on their preterm infants [11]. The first few days after birth the biggest concern is about the infant's chances of survival, but over time, this worry evolves into grief, sadness and guilt about not delivering a healthy infant. The fear of losing the infant is a huge source of suffering for mothers of preterm infants [12].

However, the motherhood requires reorganization and a change of personal identity, to being a mother of this new infant, and this process begins during pregnancy when the mother anticipates the birth of a new infant [13]. Preterm birth causes a sudden cessation of the maternal images of the anticipated infant to one of a tiny, vulnerable one [14]. The birth of a preterm infant disrupts this natural process and the separation of mother and infant occurs before the mother is physically and mentally able to shift to the actual infant [15].

Consequently, the process of transferring and accepting the role of mother in women who give birth preterm may be different from others, because the process of psychological preparation stops abruptly with the birth of a preterm infant Thus, preterm delivery and birth may trigger a crisis of adjustment in women [16–20].

Familial caregivers become responsible for more of the neonatal care at home [21]. It is essential to involve fathers in newborn care in NICU and at home.Not only does it improve the father-child attachment, but it also has positive effects on the psychological and physical development of the infant. Moreover, it has positive effects on the health of the mother and other family members, too [22, 23]. The fathers experience their role during their preterm infant’s stay in the NICU, and act as support for the mothers themselves, the mothers’ care for the infant, and the couple’s relationship [8].

Engaging fathers also has positive benefits on early mother-infant interaction [24]. During the long hospital stay, the mothers of preterm infants need assistance from trained professionals to develop their ability to provide care for their infants at home [25–27]. Preterm infants are capable of contingent communication shortly after birth. They communicate with their mothers better in comparison with others. Mothers show higher levels of engagement, interpreted as more arousing [28, 29].

Mothers as the key caregivers need to have sufficient knowledge to provide care and are the best non-professional caregivers from birth to beyond discharge. Mothers as the key caregivers need sufficient knowledge to provide care and are the best non-professional caregivers from birth to beyond discharge. Mothers from diverse cultural backgrounds exhibit varying capacities in addressing the needs of their infants. Cultural background can significantly influence parenting practices, including how mothers care for their infants. Different cultures have diverse traditions, beliefs, and practices that shape their approach to caregiving. These differences are not about one culture being better than another but rather reflect the rich diversity of human experience and how cultural heritage shapes parenting. Understanding and respecting these differences can help provide culturally sensitive support and care to mothers and their infants. Therefore understanding parent perspectives about the caring ability is crucial.

It is important to explore the meaning and attributes of caring ability of mother with preterm infant. The qualitative convectional content study provides the platform to explore the meaning of phenomenon such as caring ability. The aim of this study was to understanding the experiences regarding the care ability of the mothers of the preterm infants in the NICU and at home using the conventional content analysis method.

Literature review

Ability according to the Cambridge Dictionary means having the physical or mental strength or skill/ability needed to do a task [30], and in the Oxford dictionary means the power of an individual to perform an action [31]. The caring ability concept was first presented by Mayeroff et al. (1965) for professional neonatal nurses [32]. Caring ability means having the ability to assume responsibility for the protection and welfare of another without being perfunctory or begrudging [33].

Nemati et al. [34] defined the caring ability in caregivers of cancer disease as the rate of application of care strategies by the family caregiver, while his physical-mental health, competence, readiness, spiritual cohesion, and responsible economic status to meet patient care needs [34]. Khademi et al., defined the power of caring for a mother with a child with cancer means that the mother has the necessary characteristics and skills to meet her child's care needs [35, 36]. Nachshen believed that the power of parental care reflected their attitude, knowledge, and behavior in caring for their child [37].

Dalir et al. [38] stated that the mother’s caregiving ability for a child with congenital heart disease consisted of three dimensions: "adaptation", "care efficiency" and "care management". To provide optimal care for these children, the family must have the necessary personal characteristics to perform proper care, and in addition. must be given appropriate opportunities to strengthen and increase their ability to care [38, 39].

A family caregiver’s ability has a significant effect on the overall status of patient care. Increasing the ability of family caregivers often improves patient status [40]. Non-professional caregivers in different families and cultures have different capabilities. When confronted with the needs of their patients, they may feel vulnerable and unable to sufficiently meet these needs. This situation can lead to inadequate patient care [41–43].

Studies by Rossman et al. showed that mothers of preterm infants are not psychologically prepared for childbirth [44, 45]. A study by O'Donovan and Nixon showed that preterm birth is considered a sudden and unpredictable event that is accompanied by feelings of shock and disability. Mothers of preterm infants often describe the discharge process in terms of falling into the deep end and getting caught in the tornado and storm that surrounds them, and acknowledge that they experience a sense of lack of control and inability [46, 47]. In these stressful situations, the use of ineffective coping strategies must be considered. If the use of ineffective coping methods is not detected promptly and appropriate measures are not taken to combat them, then inadequate coping may continue [48].

Numerous studies show that maternal mental health potentially puts the preterm infant at risk for acute and chronic problems [49–51]. Caring for preterm infants also has several effects on the parents' quality of life [52, 53]. The birth of a preterm infant has a significant impact on the parents and other family members as it changes their daily routines and jobs; it may even make them reduce their working hours. The birth of a preterm infant affects the natural needs of parents, including eating, resting, health, and psychological and economic factors [54, 55].

Admitting preterm babies to the neonatal intensive care unit, hospitalization and then discharging them home may cause psychological damage to parents and even affect family relationships [56]. Broadly speaking health conditions of the infnt to be the main distressing factor for parents. During the hospitalization of the preterm infant, care is provided by professional caregivers and the mother also participates in the care. After discharge, the care is assigned to familial (non-professional) caregivers [57].

The ability to provide care has some definitions. The ethical committees and the neonatology professional bodies should make recommendations for assessing the parents’ ability to provide care and define what adequate caregiving, especially of a preterm infant means.

Method

Study design

The aim of this study is to understand the experiences regarding the caring ability of the mothers of preterm infants.This paper was a conventional content analysis based on in-person semi-structured interviews aimed to understanding the experiences regarding the care ability of the mothers of the preterm infants in the NICU and at home. The qualitative content analysis of physiological, psychological, and cultural aspects of this concept within mothers of preterm infants.

Participants

The participants were enrolled from Juan 2021 to February 2022 through purposeful and snowballing sampling. The maximize variation was considered in maternal age, multiple gestational births, the infant’s gender, the participant’s educational level, and neonatal gestational age. The participants’ infants were hospitalized in the NICU in 7 hospitals in Tehran, Iran: five public hospitals affiliated to the universities of medical sciences, and 2 private hospitals. They enrolled in the study from April 2021 to February 2022.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria consisted of being the mother of a preterm infant with a gestational age under 34 weeks, living with the spouse, speaking Farsi, being willing to participate in the study, and not having any physical or mental illnesses. The exclusion criteria consisted of having a preterm infant with congenital anomalies.

Interview

Each interview guided the researchers to find the next participant. During the first interview, with 33 years old mother the role of fathers, grandmothers, and neonatal nurses in forming the concept of care ability was mentioned; such as the role of father support, a grandmother taking care, and role of professional healthcare givers for have eligible care ability of mother. So they were then invited to participate in the study, too. Then the inclusion criteria were changed to reflect the addition of fathers, grandmothers, and the neonatal nurses who were important for the participating mothers. Totally, 11 mothers, 2 fathers, 2 grandmothers of preterm infants, 1 neonatal nurse, and 2 neonatologists participated in the present study. The neonatal nurse, and neonatologists were working in NICUs wards and had eligible experience in mother’s empowerment. Also we asked people who responded to invitations, regardless of whether they were eligible for the trial or not, to invite their family and other mothers to participate. Table 1 shows a list of open-ended and targeted questions. This, multiple data sources, is an important key component in qualitative study when striving to ensure trustworthiness that referred as data triangulation [58].

Table 1.

List of open-ended and targeted questions

| Mother | Father, Grandmother | Nurse, Neonatologists | |

|---|---|---|---|

| preinterview open ended questions | How did your infant’s hospitalization affect you?Please explore your experiences and perceptions about your caring ability? | How did infant’s hospitalization affect his/her mother?Please explore your experiences and perceptions about his/her mother caring ability? | How did infants hospitalization affect mothers and family? |

| Main questions | How do you feel you have more ability for caring?What caused you to lose your caring ability | How do you feel his/her mother has more ability for caring?What caused his/her mother to lose her caring ability? | Under what conditions do you feel the mother is desirable ability to care?What causes the mother to lose the ability to provide care? |

| Probing questions | What do you mean? Can you explain more about this? Can you give an example? | ||

| Final question | Are there any other things you want to talk to me about | ||

Data collection

The mothers who were admitted, discharged from the NICU, or visited the neonatal healthcare clinics for the first follow-up and continuing care 3–5 days after discharge were invited to join the study. The participants were selected using the purposive sampling method. The first mother was selected with the help of an NICU head nurse, who had been in contact with the mothers of the infants admitted to the NICU for a long time, based on the objectives of the study. She met the inclusion criteria, possessed extensive experience, and demonstrated effective communication skills. Subsequent participants were chosen based on the data collected from each participant.

An in-depth and semi-structured interview was used for data collection, administered by the first researcher, who is an experienced neonatal intensive care nurse. She is a registered nurse (RN), holds a PhD, and was unknown to the participants of this study. Due to the cultural rituals of discharging a baby from the hospital, the face to face interviews performed on the first visit after discharge in the clinic included broad questions (Listed in Table 1). The mothers who were admitted, discharged from the NICU, or visited the healthcare facility for follow-up and continuing care were included. Each interview guided the researchers to find the next participant. The time and the place of the interviews with formal caregivers were arranged according to the their comfort and preferences. All of them prefered doing interviw after follow up visit at a room near to neonatology clinic.

Data collection was done through in-depth and semi-structured online interviews with neonatologists and neonatal nurse via Skype. Despite we worried about, unstability of internet connection, technology issues and lack of personal interaction but all interviws well done. So the average interview length was 75 min, ranging from 53 to 110 min. The details of the interviews have been presented in Table 1. The participants were interviwed once, and all the interviews were digitally recorded. They were assured confidentiality and anonymity, as well as the right to withdraw from the study at any point without any impact on their treatment process.

Data collection continued until reaching data saturation, which was achieved after interviewing 15 participants. To confirm saturation, three more interviews were conducted, in which no new themes or information emerged. Finally, data collection finished with a total of 18 interviews.

Data analysis

Content analysis was used for subjective data interpretation. The researchers used bracketing, and allowed categories to emerge through induction. Qualitative content analysis has three main approaches: conventional, directed, and summative. The conventional approach was used in this study. It is appropriate when there is limited information and few theories about the phenomenon. Gaining information directedly, without previous categories imposed, is one of the most important attributes of conventional content analysis.

Lindgren et al.’s approach was used for data analysis. Initially, each interview was transcribed, and the transcript was read several times to immerse in the data and understand its main ideas. Then, the meaning units were identified and coded (De-contextualization). In the next step, the generated codes were compared and grouped into subcategories based on their similarities and differences. Then, the subcategories were grouped into categories. With each new interview, the previous categories could be reviewed and even merged, or a new category was created. Thus, with the formation of the subcategories, the main categories of the study were extracted and the relationships between the subcategories were determined (Re-contextualization) [59]. An author performed data analysis and other authors compared and revised the codes, subcategories, and categories. MAXQDA software version 10 was used to manage the data. An example of data analysis has been presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

An example of analysis

| De- Contextualization | Recontextualization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quotations | Condensed Meaning Units | Codes | Subcategory | Category |

| “… I saw bruising due to the lack of oxygen while hospitalization…So, I can recognize if my infant is not breathing or is breathing with difficulty …” | ability to recognize breathing stopes and distress | recognision highrisk apneas and distress breathing | sensitivity and responsiveness | Technical Ability |

| “…My baby was born preterm although she is 1360 g, and the doctors said it is not enough for discharge, but I'm not afraid that my baby might be harmed after discharge, and I am ready enough for discharge…” | to have enough feeling readiness for discharge to home | feeling readiness for discharge to home | readiness for discharge | Psychological Ability |

Trustworthiness

To ensure the rigor, Guba and Lincoln's criteria were used: credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability [60]. Credibility was ensured by allocating adequate time for data collection, data gathering through different methods, peer checking by two qualitative researchers, and long interaction with the setting and the data. The most experienced participants with the highest variety were selected to ensure confirmability. The interviews were held and analyzed in regular time intervals, and the codes and the categories were continually revised by the co-authors throughout data analysis to ensure dependability. Transferability was ensured by maximum variation sampling and appropriate quotations. To achieve authenticity, the researchers tried to show the range of facts fairly and honestly.The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist [61] was used as a support to ensure comprehensive reporting and transparency of the study.

Ethical considerations.

The Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, approved this study (code:IR.IUMS.REC.1398.1407). The aim of the study was explained to the participants and they were assured about confidential data management and their freedom to withdraw from the study in case they desired.Oral and written informed consents were obtained. The participants were given nicknames to ensure anonymity.

Findings

The study included 18 participants, i.e. 11 mothers (with the mean age of 30.54 ± 4.69 years), 2 fathers, 2 grandmothers of preterm infants, one neonatal nurse, and 2 neonatologists. Other participants' characteristics have been presented in Table 3. Data analysis resulted in the generation of 1083 final codes, which were classified into 17 subcategories and 5 categories.

Table 3.

Demographic charastristic of participants

| Participant | Infant | Interview | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) |

Kinship with infant | Education Level | Job | Gestational Age(week) | Sex | Length of NICU Stay (days) | Hospital Type | Time (minutes) |

Location of interviwe |

| 33 | Mother | Bachelor | Homemaker | 33 | F | 22 | Public | 63 | Neonatal clinic |

| 27 | Mother | Bachelor | Homemaker | 29 | F | 54 | Public | 80 | Neonatal clinic |

| 32 | Mother | Bachelor | Employee | 32 | F | 30 | Public | 52 | Neonatal clinic |

| 33 | Mother | Bachelor | Homemaker | 29 | F | 63 | Private | 55 | Neonatal clinic |

| 33 | Mother | Bachelor | Homemaker | 28 | F | 52 | Private | 53 | Neonatal clinic |

| 35 | Mother | Master | Employee | 27 | F | 81 | Public | 83 | Neonatal clinic |

| 29 | Mother | Diploma | Homemaker | 34 | F | 23 | Public | 75 | Neonatal clinic |

| 27 | Mother | Diploma | Homemaker | 31 | F | 38 | Private | 73 | Neonatal clinic |

| 28 | Mother | Master | Employee | 29 | F | 61 | Public | 85 | Neonatal clinic |

| 21 | Mother | Bachelor | Employee | 31 | F | 42 | Private | 57 | Neonatal clinic |

| 38 | Mother | Diploma | Employee | 31 | F | 29 | Private | 54 | Neonatal clinic |

| 34 | Father | Diploma | Self-Employed | 30 | M | 43 | Public | 73 | Neonatal clinic |

| 28 | Father | Doctorate | Employee | 30 | M | 33 | Public | 95 | Neonatal clinic |

| 64 | Grandmother | Primary | Retired | 32 | F | 28 | Public | 80 | Neonatal clinic |

| 53 | Grandmother | Diploma | Homemaker | 27 | F | 49 | Private | 95 | Neonatal clinic |

| 38 | Nurse | Master degree | Employee | - | F | - | Public | 75 | Online |

| 44 | Neonatologist | Medical Doctor | Employee | - | M | - | Public | 110 | Online |

| 52 | Neonatologist | Medical Doctor | Employee | - | F | - | Private | 90 | Online |

M:Male; F.Female

Main categories

Five major themes emerged from the experience of the mothers' ability to take care of their preterm infants inncluding maternal identity, infant’s needs, cognitive ability, technical ability, and psychological ability. The main categories and subcategories have been summarised in detail in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

An example of the abstraction process

Category A. Maternal identity

This category, with the three subcategories of maternal–infant attachment, maternal role competence, and maternal role satisfaction, affects the occurrence of mothers’ care ability and deals with the attribute of mothers' ability to take care of their preterm infants.

Sub-category-1-A. Maternal–infant attachment

From the participants’ point of view, this refers to the emotions and behaviors that represent an affectionate tie between a mother and her infant. Mothers showed attachment to their infants by loving them and by trying to improve the quality of care. A participant said, "… I became more excited and calmer when I touched him. So, I tried to bond with him by hugging him and singing a lullaby for him…"(Participant 4, a 33-year-old mother).

Sub-category-2-A. Maternal role competence

It refers to the mother’s judgment of how well she can function in the caregiving capacity and carry out specific tasks related to the parenting role. A participant said, "… my wife was quite competent in mothering because my miniature baby enjoyed her taking care of him. He was fragile but my wife can best take care of him without any problems. He continued to gain weight since she participated in care…." (Participant 14, a 28-year-old father).

Sub-category-3-A. Maternal role satisfaction

It refers to the mother’s enjoyment and pleasure in interacting with her infant and in carrying out maternal tasks after the neonate’s birth. A participant said, "… When they gave her to me to take care of her and she laughed at me, I became more pleased. I think my little daughter enjoys me taking care of her, too…." (Participant 2, a 27-year-old mother).

Category B. Infant’s needs

This category,with the two subcategories of illness severity and infant health status deals with the attribute of mothers’ care ability occurrence. The identification of these subcategories facilitates the transparency of mothers' ability to take care of their preterm infants.

Sub-category-1-B. Illness severity

It refers to the extent of the immaturity, the infant’s organ system’s being compromised, physiological decompensation, the duration of being involved with the disorder, and the time required for providing care. A participant said, "… I don't want to say this special condition is embarrassing, but it is bad. Although I am eating, I have to suction my baby's tracheostomy secretion. This is repeated several times a day….I spend time with her, I don’t usually participate in relatives or friends’ parties. Even if I am in company, I feel lonely…." (Participant 6, a 35-year-old mother).

Sub-category-2-B. Infant health status

The experiences of these participants demonstrated that infant health status refers to the physical condition, receiving health care, and disability. A participant said, "… Supposing that I have superpowers, is my child the same as my sister's child? No, our children have a lot of challenges. Every little thing can create a big problem for them. The children that were born term, can solve their own shortcomings and problems, and compensate to some extent….Our children are so weak and fragile that if something happens to them, they don't have the guts to let us know that there is a problem. That's why everyone says that we should always be attentive to them. Especially during the first weeks…." (Participant 11, a 38-year-old mother).

Category C. Cognitive ability

This category, with five subcategories, deals with the attribute of mothers’ ability to care for their preterm infants. Almost all the participants stated that for the provision of care, they need arrangement, logic and reasoning, independence, patience, and honesty.They believed this ability was necessary for them in order to participate in care provision and experience independent caring and problem-solving.

If the mother has enough knowledge and skill, she will be able to anticipate and detect care problems and challenges, and analyze them logically. Therefore, she can remove the challenges, either through the interventions she has learned, or through her creativity and innovation, in a way that leads to maintaining or promoting the infant’s health.

Reaching this ability is an evolutionary process, and in order to achieve this goal, the mother must participate in care provision on a regular basis, following a pre-planned schedule. She must be patient and discuss problems honestly with professional care providers so as to minimize the occurrence or the repetition of errors, and provide better quality treatment. Most of the mothers said that their cognitive ability should be assessed to identify their ability to provide care.

Sub-category-1-C. Arrangement

It refers to the mother’s planning and preparations to provide safe infant care. A participant said, "… When I came home, I was certainly very tired, but despite fatigue, I did not take my eyes off it. Sometimes, fatigue overcame me and I fell asleep, but I knew if I did not concentrate, if I did not pay attention, I would face problems somewhere. I knew I had to work hard. Thus, I wrote a day-to-day plan with accurate caregiving times….A written care plan will be helpful for the mother to improve the quality of care…." (Participant 2, a 27-year-old mother).

Sub-category-2-C. Understanding care

It refers to understanding the infant's care needs, in order to enable mothers to properly cope with the difficulties and continue providing care successfully. A participant said,“ … I mostly think that taking care of my infant is a maternal duty. In fact, I take care of my infant because I fully understand this need and have accepted that it is a part of my life now…”(Participant 8, a 27-year-old mother).

Sub-category-3-C. Independence

The experience of these participants demonstrated that they showed mothers' independence in caring for their infants by exhibiting a sense of freedom from others’ control, influence, support, aid, etc. in care provision. A participant said, “…as a first step, I was afraid of touching my infant and he was just cared for by the nurses. Then I got involved by the nurses' support. Next I did the job and they directly supervised me, mentioning my points of strength and weaknesses. Later, I provided the care and they indirectly supervised me. I gained technical skills by myself. I think this condition helped me acquire independence and an desireble sense of caring ability. When I became independent in taking care of my infant, I prepared to continue care at home…." (Participant 5, a 33-year-old mother).

Sub-category-4-C. Patience

From the participants’ points of view, what enable mothers to exhibit tolerance and persistence in spite of suffering and difficulties, without becoming annoyed or anxious, is patience. A participant said,"….The preterm infant is delicate and may not burp early after feeding, and does not have a regular bowel deficit, but the mother should be patient….Having patience helps the mother perform better.…Having patience can reduce her tension….and improve the infant’ development and weight gain …." (Participant 9, a 28-year-old mother).

Sub-category-5-C. Honesty

According to the mothers, what enables them to acquire the cognitive ability to continue providing care successfully is clear and honest communication with professional caregivers. A neonatal nurse said,“…Mothers may make mistakes while providing care. If they make a mistake, they should be honest and talk about this mistake to healthcare providers and consult them in order to know how to correct the mistake. These mothers, then, can improve their care ability skills…”(Participant 12, a 34-year- old nurse).

“…My wife once breastfed our baby more than the baby needed and what the nurse told her. Our baby also was also hungry and ate all of it, but he vomited it, which made him aspirate the milk and his breathing became difficult….. My wife told the nurse about her extravagance. This expression of my wife was very good. It made the nurses train us more and more about the indication and contraindication of take care activities…" (Participant 14, a 28-year-old father).

The mothers of preterm infants will exhibit cognitive abilities if they have a sufficient perception of care and try to become independent caregivers. They try to provide care with patience and honestly admit their caregiving mistakes. The mothers believed that cognitive ability was defined as the qualities which help them to analyze and manage the care situation.

Category D. Technical ability

This category, with three subcategories, deals with the attribute of mothers’ abilitities to care for their preterm infants through knowledge and skills, previous experience, sensitivity, and responsiveness.

Sub-category-1-D. Knowledge and skills

It deals with being aware of the nature of the special care considerations on the part of the mother in order to provide better care for her preterm infant. Skills means performing caring tasks effectively, efficiently, and confidently. All the neonatal nurses believed that the mothers were trying to gain knowledge and skills for better care provision for their preterm infants. During hospital stay, they asked their questions to nurses, doctors, and other neonatal nurses. Most of the mothers try to achieve adequate knowledge and high skills during hospital stay. A participant said, "…. When I came home, after a few days, we wanted to bathe our baby. My wife believed that she was prepared enough, as she had learned how to do it from the nurses and experienced it. In addition, my wife's mom had recorded videos while she was practicing to bathe the baby at the NICU. We had an educational booklet about basic neonatal care, which the nurse had given us during the empowerment program. If my wife knows and practices basic care, she can claim she has enough caring ability and can do it …" (Participant 9, a 28-year-old mother).

Sub-category-2-D. Previous knowledge and experience

It focuses on a broad range of background, knowledge, and prior skills to take care of infants. Some of the mothers talked with each other about their past and present experiences regarding the caring process. A participant said, "… I had no previous experience of caring for infants. So, when my baby was crying, I was desperate and I cried, too. I compared myself with other moms, I had weaknesses… However, step by step, I tried to gain awareness and skills through professional neonatal nurses, other moms, and the Internet. This process was effective for me in preparing for discharge and continuing care at home…. Now, I can identify the cause of my baby's crying and restlessness, and I know what I must do…" (Participant 2, a 27-year-old mother).

Sub-category-3-D. Sensitivity and responsiveness

It refers to the mother's ability to accurately understand and interpret the signals, identify normal and high-risk signals, and appropriately and promptly react in response to the infant’s needs. A participant said,"… When Infants are hungry, defecate, urinate, have an illness, are scared, or have other needs, they cry. Mothers must be able to recognize the difference between these so that they can take appropriate action as soon as possible. Acquiring this ability is not hereditary, neither does it happen immediately. In the first days, you, as the mother of a preterm baby, may not be able to recognize it, but over time and during the empowerment process, you will be able to identify normal and high-risk signals. In this situation, you can take the best action as soon as possible…" (Participant 4, a 33-year-old mother).

Also mentioned, "…My wife slept very well. She slept in a lot of noise and bright light and did not wake up even if the noise was loud. This was both good and bad…. When our baby was born with these special conditions and when we brought him home, I was really worried that she wouldn't sleep and something bad would happen to the baby and my wife would find out too late. ….After discharge to home, but contrary to my expectation, my wife was very alert….. It was unlikely from my wife, but she would wake up at the slightest sound of our baby and go to him and take care of his needs, and he would not return when he was not sure of his safety…" (Participant 13, a 34-year-old father).

Another mentioned,“…Participating in care provision can improve the opportunity to gain problem-solving skills. Preterm infants are at high risk for complications after discharge. When they experience care provision, they acquire sufficient sensitivity to interpret the signals. Moreover, they will be able to solve caring problems and take proper action. Thus, participating in care provision can improve one’s caring abilities…”(Participant 17, a 44- year-old Medical Doctor).

The mothers agreed that technical ability is actually defined as the knowledge and the skills to identify the strengths and the weaknesses of caring for a preterm infant. Besides having general and specialized knowledge and skills, the mother should be able to correctly understanding and interpret the signs and the symptoms of the infant’s problems, and be able to respond to them. It was stated that the mothers who possess technical ability are able to provide quality care.

Category E. Psychological ability

This category, with four subcategories, deals with the attribute of providing appropriate and enough space for the mothers’ care ability. Its four subcategories include coping with challenge, sense of control, self-efficacy, and readiness for discharge. Maternal psychological characteristics are important regarding the care ability of the mothers with preterm infants.The mothers believed that having mental strength is actually a kind of mental arrangement and makeup that helps the mother cope with the challenges she may face after discharge. If the mother has enough self-confidence and feels that she has sufficient knowledge and skills to be able to adapt to the arrival of the infant, and the challenges following its joining the family, she may feel that she is in control of the situation. She will believe that in such a situation, sudden events cannot disturb her. The mother will be prepared for the infant’s discharge and will possess acceptable self-efficacy to continue care provision. A mother who has an acceptable expectation of herself has a positive sense of self.

Sub-category-1-E. Coping with challenge

It refers to the level of ability at which the mother tries to adapt to the external environment socially, emotionally, psychologically, and morally for having a healthy and satisfactory life. A participant stated,“…As soon as I saw my baby, I hated God. I thought,‘Why me?’ I thought I could not accept that fragile infant…. But gradually, I gained more technical skills and mental preparedness. So, now, what makes me take care of my miniatoric infant is love. I hug my infant, and I have been taking care of it with love since discharge…”(Participant 2, a 27-year-old mother).

Another mentioned, “…My grandson was born preterm, and my son's wife even was afraid of touching her. She could not tolerate our fragile baby as her child… Recently she lost her mom due to Covid 19 and was so complicated…. But she decided to face take-care challenges and participated in care…. It was not simple but my dear son's wife succeed. In my opinion, she is a superman…" (Participant 16, a 64-year-old grandmother).

Sub-category-2-E. Sense of control

It deals with the extent to which the mother feels that she has control over the preterm birth event which is now influencing her life. A participant said,“…When our daughter was born, I felt that I had no control over the situation. Contrary to my expectations, my baby was born early. She had special needs and required intensive considerations. I felt that I had lost track of my life, and that I could not control the situation. I was very upset. But it didn't last long. When a week or two passed, I felt that the situation had improved, and that I could predict and evaluate the events, and had more control over the situation…” Participant 8, a 27-year-old mother).

Sub-category-3-E. Maternal self-efficacy

It refers to the mother's confidence in her own ability to successfully provide care and to perform goal-directed maternal duties. A participant said,“…Something that is very important is your beliefs.You have to be able to believe in yourself, to see your ability, as much as it really is, neither more nor less.You should believe that you are enough as a caregiver at home… This helped me a lot. I always wondered if I could independently provide care at home, whether it was time then or not, whether I was a good mom or not…I always checked my expectations of myself. At first,I had higher expectations of myself and I had a bad feeling about myself. Then I saw the other moms, and I understood preparedness would be gained gradually. As I went on, my expectations became more realistic. Now, I expect to be a perfect mother, but a mom who gets tired can sometimes be pressured. I feel better this way. I think my infant gives me the right to be a human…”(Participant 4, a 33-year-old mother).

Another mentioned,“…There is no stalemate for great men because they believe that they will find a way, if they can't they will create a way.My mom taught us when we were in complicated situations, we were supposed to be like Zagros mountains. Such kids won’t sound weak anymore. I always say it to myself repeatedly…”(Participant 2, a 27-year-old mother).

Sub-category-4-E. Readiness for discharge

It deals with the readiness for leaving the hospital for home, following an intensive care hospitalization. A participant said, “…At first, I was afraid of touching my infant. After I had more experience, my self-confidence gradually increased. Then I participated in care provision seriously, and I felt I had achieved success. I believe this helped me prepare for discharge and gain the ability to continue care provision at home…” (Participant 6, a 35-year-old mother).

All the neonatal nurses believed that these mothers had more self-efficacy, self-esteem, and more ability to provide care.

Discussion

This study was the first one to explore the caring ability of mothers of preterm infants.The findings demonstrated that the mothers of preterm infants describe caring ability based on five categories of ability: maternal identity, infant’s needs, cognitive, technical, and psychological.

According to the study’s findings, maternal identity is one of the antecedents of maternal ability. Our findings show maternal–infant attachment, maternal role competence, and maternal role satisfaction develop maternal identity. Thornton and Nardi's defined maternal identity as psychosocial readiness to role-play, which begins during pregnancy and continues by recognizing the baby, that by copying the behaviors of others, and following the recommendations. This is critical because this has a decisive effect on the child's life, developing the ideal mother–child relationship [62]. Previous studies show that the disorganized maternal identity due to internal conflicts causes some women who intend to breastfeed to experience a breastfeeding aversion response [63]. Inconsistency of maternal ability negatively impacted the mothers’ mental health and their ability to exclusively breastfeed [64]. Rafii et al. reported that maternal identity leads to the formation of maternal skills and, in turn, supports maternal well-being [65].

According to our findings infant’s needs is another antecedent. This includes the infant’s illness severity and infant health status.The infant’s health status and the severity of the disease affect the care ability of family caregivers [66]. The infant's illness’s worsening affects the ability to care, resulting in a decrease in the family caregivers' ability to provide care [67]. The ability of family members to care for another person becomes meaningful when the care process becomes chronic and lasts for days, months, or years [66]. The time required to provide care is one of the factors influencing care ability. For example, if care provision for the patient takes more than 6 months, the caregiver should have a higher care ability [66]. In addition, the required length of care affects it- the longer the required length of care, the less the provided care [36].

Participants mentioned infants' health status is not fixed, and this can effect on mother' take care ability. same to sea wave and mothers ability is like arriving a boat to the beach. Some times when sea be calm, boat can near to beach and when be storm the boat getting away from the beach. Mothers need more exposure to ill infants, more support to understand the illness.Identifying maternal identity and infant’s needs facilitates the transparency of mothers' ability to take care of their preterm infants.

According to our findings, cognitive ability, technical ability, and psychological ability are traits related to the mother’s care ability. The conceptual framework of cognitive ability was driven by reviewing the literature by Nkongho which showed that is a dimension of care ability [68]. Cognitive ability includes the skills that a person needs to do everything from the simplest to the most complex tasks such as perceptual, decision making, motor, language, and social skills [69]. Cognitive ability is the link between behavior and the brain structure, and includes a wide range of abilities, such as planning, paying attention, problem solving, doing simultaneous tasks, and cognitive flexibility [70, 71]. In the present study, cognitive ability consists of the mother’s ability to be independent; to be a problem-solver; to remember tasks; and to exhibit discipline, patience, and honesty regarding her caregiving mistakes.

Cognitive skills and abilities help the brain remember, reason, focus, think, and solve problems. They help a person process information and use cognitive skills to retrieve and use information [72]. By developing cognitive skills, one can complete this process faster and more efficiently, ensuring that he/she captures the new situation and can process it effectively [73]. The findings of a study conducted in 2004 showed that having good cognitive ability had a significant impact on the infant’s health [74]. The early stress reduction intervention and the mother–infant transaction programs can improve cognitive skills, care ability, and the infant’s neurodevelopmental outcomes [75].

Technical ability, another trait of a mother’s care ability, means the skill to apply the knowledge, methods, techniques and tools necessary to perform specific tasks gained through experience, training and education. Technical skill is the ability and skill to perform an activity with the right method and techniques. Overall the technical ability or technical skills referred to the abilities and knowledge to perform the specific care interventions the ability to provide care is mentioned, but not defined, in the 1992 report and it that does not suggest criteria for evaluating the ability to provide care by the parents. However, the operationalization of the ability to provide care involves more complex considerations [76].

Technical skill refers to specialized knowledge and expertise needed to accomplish complex actions, tasks, and processes for neonatal care. They include the following: feeding (breast and/or bottle and/or tube); attaining appropriate caloric density; bathing; donning suitable clothing; tending skin, umbilical cord and genitalia; and correctly implementing a safe infant sleeping environment. Also technical ability includes skills for handling any complex medical needs and specific health interventions e.g., the use of medical equipment [77]. Feeding issues are paramount. So Swedish families who felt they failed during the transition to home, had tube feedings and breastfeeding issues [78]. Mothers' masterful attainment of technical care skills and knowledge, in addition to the emotional comfort and confidence with preterm infant care by the time of discharge, is one of the first steps of readiness for NICU discharge [79].

Maternal sensitivity and responsibility are important features of the technical ability in forming the concept of mothers’ care ability between the mother and the preterm infants. Maternal sensitivity means the mother's ability to accurately understand and interpret signals, implicitly communicate infant behavior, and respond appropriately and promptly to them [80]. Maternal responsibility is defined as the mother's ability to recognize and act on the infant’s signals [81]. Maternal responsibility is defined as the mother's ability to recognize and act on infant symptoms [82–85]. The lived experience of the mother of a preterm infant show that they receive several signals but cannot understand which of these symptoms represents their infant’s needs. Therefore, they respond in a trial-and-error approach that may cause serious harm to the infant or mother [86]. Studies show that maternal sensitivity has modulatory effects on the developmental outcomes of preterm infants [87, 88] and maternal sensitivity is an important factor in the formation of long-term resilience to Problems are immature [89]. Previous studies showed the mothers of preterm infants are less sensitive compare to mothers of term infants [90, 91].

Technical ability is not absolute, but it can be acquired. This is not directly related to or following changes and disturbances. Preterm infants are likely to experience many complications and subsequently need care and therapeutic interventions after their discharge [92]. Heath care providers should assess the maternal intrinsic ability and empower and enable processes to attain the skills necessary for a successful NICU discharge.

Psychological ability, another trait of a mother’s care ability, was described as an internal state or feeling of being ready or prepared that referred to the alignment of conscious thoughts and actions with non-conscious behaviors [93]. Polizzi et al. found that the mother's image of inadequacy could continue or even increase when she returned home therefore the ability to cope emotionally are one of the most important dimensions of a mother's competence in the crisis after a preterm infant discharge. This means the ability to respond to the emotional needs of her infant's concerns [94]. Moreover, Erfina et al. found that the mother’s psychological well-being led to her successful transition to motherhood, and improved her ability to care for her baby [75].

The mother's psychological characteristics also affect her ability to care. Preterm birth and hospitalization in the neonatal intensive care unit cause many psychological problems for parents: anxiety, stress, worry, frustration, and confusion. In addition, anger, crying, sadness, frustration, dissatisfaction, regret, frustration, bad feelings, self-blame, nervousness, confusion and lack of self-control were some of the major emotional problems raised [95].

The NICU discharge is associated with an increase in stress and anxiety in parents and neonatal nurses [96]. Parents often experience stress, guilt, anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep disorder, and fear, after the neonate's admission to NICU [96–99]. They are decision-making agents for neonates in NICU, and as a result, this responsibility increases their mental pressure. Thus, mental preparedness should be considered as part of parental empowerment programs [100–102]. Some mothers may have mental health issues (anxiety, postpartum depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and nightmares) as well as psychological effects of illness (e.g., pain) that are barriers to discharge planning [103]. Mothers use various coping strategies to calm and support themselves and their infants while adjusting to their preterm infant [104]. Thus, a mental readiness assessment is recommended before discharge to evaluate their maternal caring ability.

Parent education begins the first day the infant arrives in the NICU and builds throughout the hospitalization with consistent visitation and participation by the parents/caregivers. Parents become more confident about their skills and are prepared to take their infant home [105]. Discharge teaching for parents of newborns with special needs is a unique process. This process begins with the establishment of a trusting relationship with the parents and includes an assessment of the family's feelings, readiness to learn, and resources [106].

Also, active participation of mothers in NICU is essential. So, this can improve respiratory function, improve nutrition, improve weight gain, reduce the length of hospital stay and care costs, improve survival quality, and reduce other risks of preterm infants. Family-centered care can also affect the psychological and behavioral problems of infants in the future [107].

Parents of preterm infants experience bittersweet events that give rise to a contrasting pendulum sensation. Reflecting parents' voices and understanding their experiences, needs and problems will turn their bitter experiences into sweet ones [108]. So if neonatal nurses are aware of post-discharge challenges, they will be able to purposefully prepare parents for care and minimize post-discharge confusion [109].

[110], who studied the characteristics of the concept of hospital discharge using an analytical approach, found that having physical stability, adequate support, psychological strength, and having sufficient knowledge and information are the characteristics of readiness for discharge [110].

Broadly speaking there is a wide variability of situations leading to admission to the NICU, some acute but with a positive prognosis, others with aspects of severity and/or chronicity and/or low birth weight. Likewise, it should not be forgotten that the impact of a NICU admission is embedded in a pre-existing personal psychological framework. These elements must be taken into account for any parenting support intervention for these families. Also according to the results, NICU environment should be interactive. The dissociation of the mother and the infant should be limited, and the zero-separation approach should be implemented.

In the present study, we found that maternal caring ability is a concept that is multidimensional, relative, unique, complex, and has a consequential nature. A mother that has the mothers’ care ability has cognitive, technical and psychological abilities. Discharge plans should be combination of educational formats that incorporate the cognitive, technical and psychological abilities of mothers of preterm infants.

Strength limitations

The present study has some points of strength. Based on the literature review, the concept of the care ability of a mother with a preterm infant has not been explained yet and this study was designed to explore formal and non-professional caregivers. This study was conducted in seven NICUs and a diverse study population, using multiple data sources. The limitation of this study that should be considered while interpreting the results, maybe the limitation of transferability due to limited diversity of groups of participants, as in other qualitative research studies.

Conclusion

Achieving a desirable ability to provide care is a process that starts during hospitalization and continues beyond discharge. The mothers with desirable caring ability must have sufficient cognitive, technical, and psychological abilities. They should have the knowledge and the skills to continuously learn to manage possible post-discharge complications. It is necessary for nurses and other neonatal nurses to understand caring ability. The identification and understanding of mothers' experiences are of particular importance for providing services to reduce post-discharge suffering and care burden, and to increase the quality of life. Neonatal nurses need to understand behaviors in the mothers who are trying to participate in care provision. They should also manage the mothers’ abilities to provide interventions in order to empower and enable them to engage in neonatal care as soon as possible. It can also help health planners and policy makers to prepare facilities and services for caregivers. The ethical committees and the neonatology professional bodies should make recommendations for assessing the parents’ ability to provide care.

Acknowledgements

This article is part of a Ph.D. thesis of the first author, which was financially supported by the Nursing Care Research Center in Iran University of Medical Sciences (NCRC-1407). The authors would like to extend their sincere thanks to mothers, healthcare providers and other participants who shared their experiences with us.

Preprint disclosure

Authors have not consent for preprint publication.

Abbreviations

- NICU

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

- RN

Registered Nurse

Authors’ contribution

Authorship Contribution Statement: Saleheh Tajalli: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Soroor Parvizy: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Validation, Funding acquisition. Abbas Ebadi: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing review & editing, Resources. Fateme Zamaniashtiani: Writing—review & editing. Carole Kenner: Writing -review & editing, Resources. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Saleheh Tajalli, Abbas Ebadi and Carole Kenner have no funding to disclose. Soroor Parvizy is supported by a grant from the vice chancellor of research from Nursing are Research Center in Iran University of Medical Sciences under Grant number [1398-12-27-1407] CRediT.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Request access to other supplementary material can be directed to the first or corresponding author.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All ethical considerations of the study were approved by the ethics committee at the IRAN University of Medical Sciences (IR. IUMS. REC.1398.1407). Also all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

All parents of neonate in the study were informed of the study objectives and signed a written informed consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Completing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Soroor Parvizy, Email: s_parvizy@yahoo.com.

Abbas Ebadi, Email: ebadi1347@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Lasiuk GC, Comeau T, Newburn-Cook C. Unexpected: an interpretive description of parental traumas’ associated with preterm birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howson C, Merialdi M, Lawn J, Requejo J, Say L. March of dimes white paper on preterm birth: the global and regional toll. March of dimes foundation. 2009:13.

- 3.Santhakumaran S, Statnikov Y, Gray D, Battersby C, Ashby D, Modi N. Survival of very preterm infants admitted to neonatal care in England 2008–2014: time trends and regional variation. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018;103(3):F208–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stefana A, Lavelli M. Parental engagement and early interactions with preterm infants during the stay in the neonatal intensive care unit: protocol of a mixed-method and longitudinal study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2): e013824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ionio C, Colombo C, Brazzoduro V, Mascheroni E, Confalonieri E, Castoldi F, et al. Mothers and fathers in NICU: the impact of preterm birth on parental distress. Eur J Psychol. 2016;12(4):604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller-Nix C, Forcada-Guex M, Pierrehumbert B, Jaunin L, Borghini A, Ansermet F. Prematurity, maternal stress and mother–child interactions. Early Human Dev. 2004;79(2):145–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zelkowitz P, Bardin C, Papageorgiou A. Anxiety affects the relationship between parents and their very low birth weight infants. Infant Mental Health Journal: Official Publication of The World Association for Infant Mental Health. 2007;28(3):296–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stefana A, Biban P, Padovani EM, Lavelli M. Fathers’ experiences of supporting their partners during their preterm infant’s stay in the neonatal intensive care unit: a multi-method study. J Perinatol. 2022;42(6):714–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stefana A, Padovani EM, Biban P, Lavelli M. Fathers’ experiences with their preterm babies admitted to neonatal intensive care unit: A multi-method study. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(5):1090–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gateau K, Song A, Vanderbilt DL, Gong C, Friedlich P, Kipke M, et al. Maternal post-traumatic stress and depression symptoms and outcomes after NICU discharge in a low-income sample: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee Y, Tang F. More caregiving, less working: Caregiving roles and gender difference. J Appl Gerontol. 2015;34(4):465–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowler C, Green J, Elliott D, Petty J, Whiting L. The forgotten mothers of extremely preterm babies: A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(11–12):2124–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stern DN, Bruschweiler-Stern N. The birth of a mother: How the motherhood experience changes you forever: Basic Books; 1998.

- 14.Slade A, Cohen LJ, Sadler LS, Miller M. The psychology and psychopathology of pregnancy. Handbook of infant mental health. 2009;3:22–39. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spinelli M, Frigerio A, Montali L, Fasolo M, Spada MS, Mangili G. ‘I still have difficulties feeling like a mother’: The transition to motherhood of preterm infants mothers. Psychol Health. 2016;31(2):184–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alinejad-Naeini M, Peyrovi H, Shoghi M. Self-reinforcement: Coping strategies of Iranian mothers with preterm neonate during maternal role attainment in NICU. A qualitative study Midwifery. 2021;101:103052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kenner C. Caring for the NICU parent. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 1990;4(3):78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenner C, Flandermeyer A, Spangler L, Thornburg P, Spiering D, Kotagal U. Transition from hospital to home for mothers and babies. Neonatal Netw. 1993;12(3):73–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boykova M. Transition from hospital to home in parents of preterm infants: revision, modification, and psychometric testing of the questionnaire. J Nurs Meas. 2018;26(2):296–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boykova M, Kenner C. Transition from hospital to home for parents of preterm infants. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2012;26(1):81–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raina P, O’Donnell M, Rosenbaum P, Brehaut J, Walter SD, Russell D, et al. The health and well-being of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):e626–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldoni F, Ancora G, Latour JM. Being the father of a preterm-born child: contemporary research and recommendations for NICU staff. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:724992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stefana A, Lavelli M, Rossi G, Beebe B. Interactive sequences between fathers and preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Early Human Dev. 2020;140:104888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yogman M, Garfield CF, Bauer NS, Gambon TB, Lavin A, Lemmon KM, et al. Fathers’ roles in the care and development of their children: The role of pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20161128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jefferies AL. Society CP, Fetus, Committee N Going home: facilitating discharge of the preterm infant. Paediatr child health. 2014;19(1):31–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raffray M, Semenic S, Osorio Galeano S, Ochoa Marín SC. Barriers and facilitators to preparing families with premature infants for discharge home from the neonatal unit. Perceptions of health care providers. Investigacion y educacion en enfermeria. 2014;32(3):379–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D, Rodgers CC. Wong's essentials of pediatric nursing-e-book: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021.

- 28.Feldman R, Eidelman AI. Maternal postpartum behavior and the emergence of infant–mother and infant–father synchrony in preterm and full-term infants: The role of neonatal vagal tone. Dev Psychobiol. 2007;49(3):290–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lavelli M, Stefana A, Lee SH, Beebe B. Preterm infant contingent communication in the neonatal intensive care unit with mothers versus fathers. Dev Psychol. 2022;58(2):270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cambridge D. Cambridge University Press 2018. 2018.

- 31.Matthews PH. The concise Oxford dictionary of linguistics: Oxford University Press; 2014.

- 32.Mayeroff M. On caring. International Philosophical Quarterly. 1965;5(3):462–74. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noddings N. An ethic of caring and its implications for instructional arrangements. Am J Educ. 1988;96(2):215–30. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nemati S, Rassouli M, Ilkhani M, Baghestani AR, Nemati M. Development and validation of ‘caring ability of family caregivers of patients with cancer scale (CAFCPCS).’ Scand J Caring Sci. 2020;34(4):899–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nemati S, Rassouli M, Ilkhani M, Baghestani AR. Perceptions of family caregivers of cancer patients about the challenges of caregiving: a qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2018;32(1):309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khademi F, Rassouli M, Mojen LK, Heidarzadeh M, Farahani AS. Psychometric Evaluation of the Caring Ability of Family Caregivers of Patients With Cancer Scale–Mothers’ Version for the Mothers of Children With Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2022;45(1):E179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nachshen JS. Empowerment and families: Building bridges between parents and professionals, theory and research. Journal on Developmental Disabilities. 2005;11(1):67–76. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dalir Z, Heydari A, Kareshki H, Manzari ZS. Coping with caregiving stress in families of children with congenital heart disease: A qualitative study. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery. 2020;8(2):127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dalir Z, Manzari Z-S, Kareshki H, Heydari A. Caregiving strategies in families of children with congenital heart disease: A qualitative study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2021;26(1):60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grant JS, Elliott TR, Weaver M, Glandon GL, Raper JL, Giger JN. Social support, social problem-solving abilities, and adjustment of family caregivers of stroke survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(3):343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiménez L, Antolín-Suárez L, Lorence B, Hidalgo V. Family education and support for families at psychosocial risk in Europe: Evidence from a survey of international experts. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;27(2):449–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith ME, Lindsey MA, Williams CD, Medoff DR, Lucksted A, Fang LJ, et al. Race-related differences in the experiences of family members of persons with mental illness participating in the NAMI Family to Family education program. Am J Community Psychol. 2014;54(3–4):316–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Atagün Mİ, Balaban ÖD, Atagün Z, Elagöz M, Özpolat AY. Caregiver burden in chronic diseases. Current Approaches in Psychiatry. 2011;3(3):513–52. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aktaş S, Aydın R. The analysis of negative birth experiences of mothers: A qualitative study. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2019;37(2):176–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossman B, Greene MM, Meier PP. The role of peer support in the development of maternal identity for “NICU moms.” J Obstetr, Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2015;44(1):3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Medina IMF, Granero-Molina J, Fernández-Sola C, Hernández-Padilla JM, Ávila MC, Rodríguez MdML. Bonding in neonatal intensive care units: Experiences of extremely preterm infants’ mothers. Women and Birth. 2018;31(4):325–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Donovan A, Nixon E. “Weathering the storm:” Mothers’ and fathers’ experiences of parenting a preterm infant. Infant Ment Health J. 2019;40(4):573–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Association NAND. NANDA nursing diagnosis list for 2015–2017.

- 49.Beck CT, Harrison L. Posttraumatic stress in mothers related to giving birth prematurely: A mixed research synthesis. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2017;23(4):241–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galeano MD, Carvajal BV. Coping in mothers of premature newborns after hospital discharge. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev. 2016;16(3):105–9. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glynn LM, Howland MA, Fox M. Maternal programming: Application of a developmental psychopathology perspective. Dev Psychopathol. 2018;30(3):905–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jubinville J, Newburn-Cook C, Hegadoren K, Lacaze-Masmonteil T. Symptoms of acute stress disorder in mothers of premature infants. Adv Neonatal Care. 2012;12(4):246–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boykova M, Kenner C. Transition from hospital to home for parents of preterm infants. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2012;26(1):81–7; quiz 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Foster M, Whitehead L. Family centred care in the paediatric high dependency unit: Parents’ and Staff’s perceptions. Contemp Nurse. 2017;53(4):489–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kenner C, McGrath JM. Developmental care of newborns & infants: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2021.

- 56.Garfield JM, Garfield FB, Kodali B, Sarin P, Liu X, Vacanti JC. A postoperative visit reveals a significant number of complications undetected in the PACU. Perioperative Care and Operating Room Management. 2016;2:38–46. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Franck LS, O’Brien K. The evolution of family-centered care: From supporting parent-delivered interventions to a model of family integrated care. Birth defects research. 2019;111(15):1044–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(5):545–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lindgren B-M, Lundman B, Graneheim UH. Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;108: 103632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handbook of qualitative research. 1994;2(163–194):105. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thornton R, Nardi PM. The dynamics of role acquisition. Am J Sociol. 1975;80(4):870–85. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morns MA, Steel AE, McIntyre E, Burns E. “It Makes My Skin Crawl”: Women’s experience of breastfeeding aversion response (BAR). Women Birth. 2022;35(6):582–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuswara K, Knight T, Campbell KJ, Hesketh KD, Zheng M, Bolton KA, et al. Breastfeeding and emerging motherhood identity: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of first time Chinese Australian mothers’ breastfeeding experiences. Women Birth. 2021;34(3):e292–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rafii F, Alinejad-Naeini M, Peyrovi H. Maternal Role Attainment in Mothers with Term Neonate: A Hybrid Concept Analysis. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2020;25(4):304–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coppetti LdC, Girardon-Perlini NMO, Andolhe R, Gutiérrez MGRd, Dapper SN, Siqueira FD. Caring ability of family caregivers of patients on cancer treatment: associated factors. Revista latino-americana de enfermagem. 2018;26:3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Wang D, Wang H, Gao H, Zhang H, Zhang H, Wang Q, et al. P2X7 receptor mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation in depression and diabetes. Cell Biosci. 2020;10(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nkongho NO. The caring ability inventory. Measurement of nursing outcomes. 2003;3:184–98. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Benjamin DJ, Brown SA, Shapiro JM. Who is ‘behavioral’? Cognitive ability and anomalous preferences. J Eur Econ Assoc. 2013;11(6):1231–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ones DS, Dilchert S, Viswesvaran C, Salgado JF. Cognitive abilities. 2010.

- 71.Ree MJ, Carretta TR, Steindl JR. Cognitive ability. Handbook of industrial, work and organizational psychology. 2001;1:219–32. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ones DS, Dilchert S, Viswesvaran C, Salgado JF. Cognitive ability: Measurement and validity for employee selection. Handbook of employee selection: Routledge; 2017. p. 251–76. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dilchert S. Cognitive ability. 2018.

- 74.Rubalcava LN, Teruel GM. The role of maternal cognitive ability on child health. Econ Hum Biol. 2004;2(3):439–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Milgrom J, Holt C, Bleker L, Holt C, Ross J, Ericksen J, et al. Maternal antenatal mood and child development: an exploratory study of treatment effects on child outcomes up to 5 years. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2019;10(2):221–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moratti S. The parents’ ability to take care of their baby as a factor in decisions to withhold or withdraw life-prolonging treatment in two Dutch NICUs. J Med Ethics. 2010;36(6):336–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smith V, Hwang S, Dukhovny D, Young S, Pursley D. Neonatal intensive care unit discharge preparation, family readiness and infant outcomes: connecting the dots. J Perinatol. 2013;33(6):415–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Larsson C, Wågström U, Normann E, Thernström BY. Parents experiences of discharge readiness from a Swedish neonatal intensive care unit. Nurs Open. 2017;4(2):90–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Smith VC. Discharge planning considerations for the neonatal intensive care unit. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2021;106(4):442–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall SN. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation: Psychology Press; 2015.

- 81.Karl D. Maternal responsiveness of socially high-risk mothers to the elicitation cues of their 7-month-old infants. J Pediatr Nurs. 1995;10(4):254–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.De Wolff MS, Van Ijzendoorn MH. Sensitivity and attachment: A meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Dev. 1997;68(4):571–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shin H, Park YJ, Ryu H, Seomun GA. Maternal sensitivity: A concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2008;64(3):304–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Perricone G, Prista Guerra M, Cruz O, Polizzi C, Lima L, Morales MR, et al. Maternal coping strategies in response to a child’s chronic and oncological disease: a cross-cultural study in Italy and Portugal. Pediatric reports. 2013;5(2):e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nakić Radoš S, Brekalo M, Matijaš M. Measuring stress after childbirth: development and validation of the Maternal Postpartum Stress Scale. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2021;41(1):65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mousavi SS, Keramat A, Mohagheghi P, Mousavi SA, Motaghi Z, Khosravi A, et al. The need for support and not distress evoking: A meta-synthesis of experiences of iranian parents with premature infants. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. 2017;11(4).

- 87.Jaekel J, Pluess M, Belsky J, Wolke D. Effects of maternal sensitivity on low birth weight children’s academic achievement: a test of differential susceptibility versus diathesis stress. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(6):693–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shah PE, Robbins N, Coelho RB, Poehlmann J. The paradox of prematurity: The behavioral vulnerability of late preterm infants and the cognitive susceptibility of very preterm infants at 36 months post-term. Infant Behav Dev. 2013;36(1):50–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Faure N, Habersaat S, Harari MM, Müller-Nix C, Borghini A, Ansermet F, et al. Maternal sensitivity: a resilience factor against internalizing symptoms in early adolescents born very preterm? J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2017;45(4):671–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Butti N, Montirosso R, Borgatti R, Urgesi C. Maternal sensitivity is associated with configural processing of infant’s cues in preterm and full-term mothers. Early Human Dev. 2018;125:35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Korja R, Latva R, Lehtonen L. The effects of preterm birth on mother–infant interaction and attachment during the infant’s first two years. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(2):164–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Burnham N, Feeley N, Sherrard K. Parents’ perceptions regarding readiness for their infant’s discharge from the NICU. Neonatal Netw. 2013;32(5):324–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Conner-Spady BL, Marshall DA, Hawker GA, Bohm E, Dunbar MJ, Frank C, et al. You’ll know when you’re ready: a qualitative study exploring how patients decide when the time is right for joint replacement surgery. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Polizzi C, Perricone G, Morales MR, Burgio S. A Study of Maternal Competence in Preterm Birth Condition, during the Transition from Hospital to Home: An Early Intervention Program’s Proposal. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]