Abstract

Behavior‐change lifestyle interventions are fundamental in children and adolescent obesity management. This scoping review discusses optimal behavior‐change lifestyle interventions in the treatment of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents. A literature search on diet, physical activity, and behavioral intervention for obesity treatment in children and adolescents aged 0–19 years was conducted in the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE (OVID), EMBASE, and ClinicalTrials.gov. Systematic reviews and meta‐analyses with randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in English from June 2016 to November 2022 were retrieved to identify recent advancements. Obesity outcomes included body weight, body mass index (BMI), BMI z‐score, and fat percentage, among others. The 28 located reviews included: four studies on diet therapy; five on physical activity (exercise training); one on sedentary activities; 18 on multicomponent behavior‐change lifestyle interventions, including three that incorporated gaming; three with eHealth, mobile health (mHealth), or telehealth, with one in each category; and two on motivational interviewing. Behavior‐change lifestyle interventions to reduce obesity in children and adolescents were associated with moderate effects, with low‐quality evidence for diet therapy and high‐quality evidence for exercise training, both for weight or BMI reduction. Long‐term intensive multicomponent behavioral interventions with parental involvement demonstrated better effects.

Keywords: behavior‐change intervention, children and adolescents, obesity, randomized controlled trial, systematic review

This scoping review discusses optimal behavior‐change lifestyle interventions in the treatment of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents.

INTRODUCTION

Behavior‐change interventions, also referred to as lifestyle interventions, play a central role in obesity management for children and adolescents. These interventions include diet, physical activity, and/or other behavior‐change approaches. Decreased energy intake with increased physical activity, and/or with other lifestyle modifications (e.g., reduced sedentary time and improved sleep hygiene) is often recommended across all obesity management approaches. 1 Recently published clinical practice guidance, expert consensus, and position statements of academic panels on interventions for managing obesity in children and adolescents include a large body of evidence focused on behavioral change recommendations. 2 , 3 , 4 These recommendations are based on evidence syntheses such as the Cochrane reviews on the efficacy of behavior‐change interventions in children up to the age of six, children and adolescents 6–11 years old, and adolescents 12–17 years old. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Despite this body of evidence, some research gaps remain, including the impact of these interventions on obesity measures, safety (i.e., adverse effects), and clarity on the active components of successful behavior change.

Recent studies conducted in low‐ and middle‐income countries are yet to be incorporated into existing systematic reviews. 9 , 10 , 11 A more up‐to‐date review of the evidence on approaches for the treatment of pediatric overweight and obesity will help clinicians adopt evidence‐based decision making when providing care to children and adolescents and their families. This review aimed to describe the benefits, harms, and active components of behavioral‐change lifestyle interventions for the treatment of obesity in children (0–9 years old) and adolescents (10–19 years old) with obesity.

METHODS

Study design

We performed an overview of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on behavior‐change intervention for obesity management in children and adolescents aged 0–19 years according to the PRISMA guidelines 12 , 13 (see Appendix I in the Supporting Information).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria in Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO)

The PICO framework includes the following: (1) P: children and adolescents 0–19 years old with overweight or obesity; (2) I: any single or combination behavior‐change approaches, for example, diet/nutrition, exercise and/or physical activity, sedentary behaviors, sleep hygiene, and behavior‐change strategies/techniques; (3) C: with a control or any comparator; (4) O: primary or secondary outcome changes related to managing obesity, that is, body weight, body mass index (BMI), BMI z‐score, or other adiposity indices such as body fat percentage, fat mass, waist circumferences; or proportion of change of the indices. Effect size of obesity measurement was expressed as mean difference (MD), weighted mean difference (WMD), standard mean difference (SMD), or Hedges’ g.

We included systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of RCTs, including clustered RCT studies. They could be conducted in any setting, for example, clinics, hospitals, labs, families, schools, or communities, with or without intervention techniques (e.g., gaming, eHealth, mobile health [mHealth], telehealth). Topics included diet, physical activity, and behavioral treatment interventions for children and adolescents under 19 years old with overweight or obesity.

Studies were excluded for any of the following reasons: (1) reviews included non‐RCT or observational studies (in this case, only extracted the results of meta‐analyses in RCT studies); (2) studies that assessed obesity prevention interventions; (3) studies that involved drug trials (including micronutrient supplement intervention) or an intervention that dealt with eating disorders, or targeted cardiometabolic risks; (4) studies that included participants with obesity due to secondary or syndromic causes; (5) studies that included children and adolescents without obesity at baseline; or (6) studies that assessed diet combined with pharmacological treatments or surgical interventions.

Databases and search criteria

In 2016 and 2017, a series of updated Cochrane systematic reviews and meta‐analyses evaluated the effects of diet, physical activity, and behavioral lifestyle interventions on obesity treatment in children and adolescents. 5 , 6 , 7 This scoping review aimed to identify recent advancements on the same topic. A literature search strategy was developed based on the previously mentioned references 5 and was revised by an academic librarian as well as experts on evidence‐based medicine. Key terms used in the search strategy included diet*, behavior*, obes*, overweight, child*, adolescen*, p*diatric, management, weight management, and treatment. The databases used to conduct the systematic searches were the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE (OVID), EMBASE, and ClinicalTrials.gov. The search strategies for each database are included in Appendix I in the Supporting Information. Studies retrieved were published between June 2016 and November 2022. Additional supplementary searches included reference checking of the included publications and consultation with subject experts for relevant published studies. Gray literature was not included in the systematic search due to time constraints.

Study selection and data extraction

The search results were imported into EndNote 20.0, which was employed for screening titles, abstracts, and full texts. Data were extracted by one of the authors (L.L.); a separate group of authors captured study characteristics. During the first search phase, articles were selected according to their title and summary/abstract. Articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were discarded. In the second phase, full‐text versions of the remaining references were read and analyzed. The information extracted from the selected articles included the countries where the research was conducted, the number of studies included, the number of participants, and the type and duration of the interventions. In addition, specific data were recorded regarding the effect size, safety, mechanisms of action, and/or moderators/mediators of the interventions in each study. The quality of evidence was recorded as per the authors' reports.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the included reviews

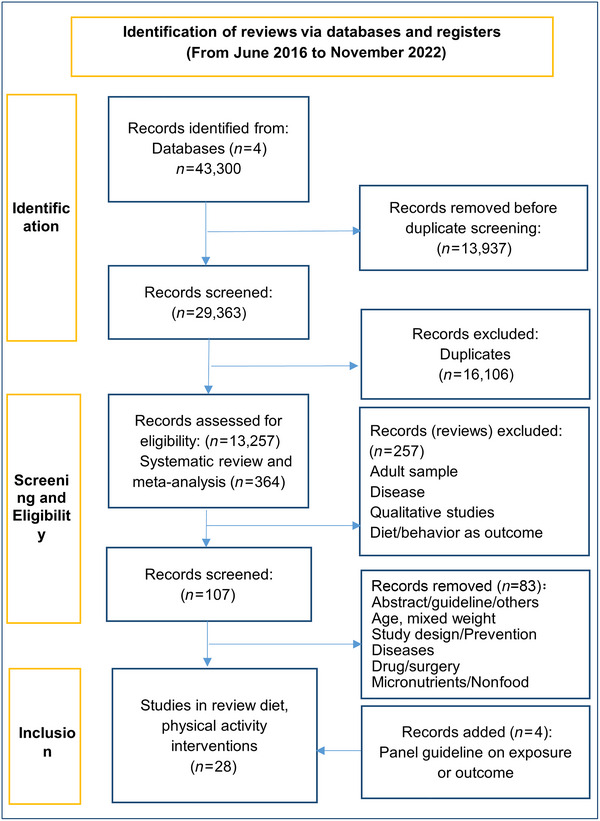

The searches generated 13,257 hits (including clinical trials) after duplicates were removed. Of these, 364 systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of RCTs on this topic were screened by title and abstract. One hundred and seven records were considered for full‐text screening, of which 24 were included in the review. Four additional records were identified through the snowball technique from nondatabase sources. The flowchart can be found in Figure 1. Of the 28 reviews, four focused on diet therapy only; 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 five on supervised exercise training; 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 one on sedentary behaviors; 23 and 18 on multicomponent behavior‐change lifestyle interventions, including three with gaming tools; three with eHealth, mHealth, or telehealth, with one in each category; and two with motivational interviewing. 5 , 6 , 7 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 For a detailed description of the included reviews, see Appendix II in the Supporting Information.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of the study selection.

Summary of findings

Most behavior‐change lifestyle interventions had moderate effects in reducing obesity outcomes (e.g., body weight, BMI, and BMI z‐score). The quality of evidence was low or moderate. Intervention settings included clinics, primary care, family, school, and community, among others. Behavior‐change strategies such as motivational interviewing and/or various behavior‐change strategies/techniques (e.g., goal setting, monitoring, and stimulus control) were widely used, with the concurrent increase in the use of digital technologies such as gaming tools, 19 , 24 , 25 eHealth, 26 mHealth, 27 telehealth, 28 and so forth. However, some lifestyle interventions failed to improve the main obesity outcomes (e.g., some dietary interventions, 15 , 16 resistance exercise training, 29 mHealth, 27 some lifestyle or educational intervention, etc.) or presented controversial results. 30 , 31 The main results are presented in Appendix II in the Supporting Information.

Impact of behavior‐change lifestyle interventions in obesity treatment

Lifestyle interventions with diet, physical activity, and behavior‐change components induced small to modest changes in obesity measurements in all age groups.

Age and populations

In the Cochrane reviews, lifestyle interventions were reported to be beneficial for reducing weight and BMI measures, most with low‐ or very low‐quality evidence. 5 , 6 , 7 In children 0–6 years old (seven trials, 923 participants), multicomponent behavior‐change lifestyle interventions resulted in a greater reduction in BMI than the comparator at the end of the intervention period and at 24 months follow‐up (MD in BMI z‐score: −0.3 to −0.4 units). 5 In children and adolescents 6–11 years old (70 trials, 8461 participants), family interventions with portion control strategy promoted short‐term (up to 6‐month post–intervention) reductions in measures including BMI (−0.53 kg/m2), BMI z‐score (−0.06 units), and body weight (−1.45 kg). 6 In adolescents 12–17 years old (44 trials, 4781 participants), obesity measures were reduced (BMI: −1.18 kg/m2; BMI z‐score: −0.13 units; and body weight: −3.67 kg) at the longest follow‐up period (24 months). The effect on weight measures persisted in trials with 18‐ to 24‐month follow‐ups for both BMI (−1.49 kg/m2) and BMI z‐score (−0.34 units). 7

Similar impacts were reported in some non‐Cochrane reviews in children 2–5 years of age (BMI: −0.17 kg/m2), 32 in children and adolescents under 19 years of age (BMI and BMI z‐score: −0.255, 18 trials), 23 in children and adolescents 6–12 years old (BMI z‐score: −0.09 units, four trials), in adolescents (BMI and BMI z‐score: −0.54 Hedges’ g), 38 and in children and adolescents of different socioeconomic backgrounds (BMI z‐score: −0.16 to −0.08 units), respectively. 39 Resistance training physical activity combined with calorie restriction in children and adolescents <18 years old (23 trials) reduced the body fat percentage (−2.1%) and whole‐body fat mass (−1.9 kg, good‐quality evidence), although body weight and BMI were not significantly reduced. 29 Besides obesity reduction, behavior‐change lifestyle interventions were effective in weight maintenance for 6–12 months in children and adolescents (BMI z‐score: 2.22–2.00 units, 11 trials). 34

Settings

Some systematic reviews and meta‐analyses reported on eligible community and school interventions for obesity treatment in children and adolescents. Community group interventions (20 trials) were delivered in various settings, including home, outpatient clinics, and community health services, with various intervention delivery methods including face‐to‐face, online, phone, mobile applications, and mixed methods. These interventions were associated with a reduction in BMI z‐score by 2%–9% from 6 weeks to 24 months. BMI z‐score decreased significantly (i.e., ≥10%) when including a psychological component (four trials). The involvement of digital technologies, such as online interventions in addition to face‐to‐face sessions did not add better effects. 35 School nutrition interventions in various populations from Asia 36 , 37 were effective in BMI reduction (−0.94 kg/m2 36 and −2.03 kg/m2 37 ) although effects differed by the intervention duration, sample characteristics, sample size, and engagement of parents. BMI changes were strengthened with longer duration (more than 1 year, −3.03 kg/m2) or in adolescents 12–18 years old (−1.90 kg/m2). 37

Digital technology involvement

Interventions involving digital technology that integrated games, 19 , 24 , 25 eHealth, 26 mHealth, 27 and telehealth 28 were reported as promising tools and have been increasingly used in obesity treatment through the past decade. However, the effect sizes on obesity reduction were closely associated with the intervention contexts and implementation characteristics. The effects of diet‐incorporated game interventions in obesity management were inconclusive regarding obesity reduction in children 3–6 years old and adolescents 10–12 years old (23 trials). Games, however, improved self‐efficacy and healthy eating behaviors. 25 Game‐integrated exercises (10 trials) in children and adolescents 8–16 years old induced significant positive effects (SMD of BMI: −0.234 kg/m2, BMI z‐score: −0.181 units; 10 trials). 24 Behavior‐change lifestyle interventions targeted obesity‐relating behaviors via eHealth reduced obesity measures (pooled effect SMD −0.219, 16 trials), 26 while interventions via mHealth technologies employing self‐monitoring on weight status (two trials) did not show significant changes in weight status. 27 Telehealth education and behavior‐based studies reduced BMI z‐score (pooled net change: −0.04 units, 10 trials) when compared to usual care. 28

Overall, long‐term, comprehensive, and intensive interventions targeting multiple components of energy‐balance‐related behaviors, integrated with behavior‐change strategies, can produce significant effects across settings and populations. 5 , 6 , 7 , 35 , 36 , 37 Comprehensive, intensive interventions refer to interventions consisting of multiple components including sessions targeting both the parents and child (separately, together, or both); offering group sessions in addition to individual or single‐family sessions; providing information about healthy eating, safe exercising, and reading food labels; incorporating behavior‐change techniques (BCTs) such as problem solving, monitoring diet and physical activity behaviors, and goal setting; and with contact time >26 h over 3–12 months. Gaming and digital technologies may improve efficacy when combined with other interventions. 19 , 24 , 25 These results are based on only a few studies and the meta‐analyses had a high heterogeneity. The results must be interpreted with caution.

Physical activity/exercise training

Supervised exercise was associated with modest effects on body weight, BMI, or central obesity, mostly based on moderate‐ to high‐quality evidence. Supervised exercise interventions reduced obesity measures in children and adolescents 6–18 years old (BMI: −1.34 kg/m2, 12 trials), with various exercise trainings or other interventions leading to physical stress (i.e., cardio training, cardio training and strength training, cardio training and flexibility, or multicomponent exercise) 18 ; in children and adolescents 6–12 years old (BMI z‐score: −0.09 units, four trials) using active video games 19 ; in adolescents (BMI: −1.99 kg/m2, 15 trials) using different exercise modalities (i.e., aerobic training, resistance training, combined aerobic and resistance training, or high‐intensity interval training) 20 ; and in children and adolescents 6–18 years old (BMI: −1.34 kg/m2, SMD: −0.29, lean body mass increase of 3.07 kg, SMD: 0.32, 12 trials) using concurrent aerobic plus resistance exercise when compared to aerobic exercise favoring longer term programs (>24 weeks). 21 Concurrent aerobic and strength training produced the biggest effect size (BMI z‐score: −0.11 to 0.04 units, 34 trials) among the exercise modalities. 22

Overall, supervised exercise can reduce BMI, BMI percentile, BMI z‐score, waist circumference, and fat mass, and increase lean body mass in children and adolescents with overweight or obesity (high‐quality evidence). Aerobic plus resistance exercise in children and adolescents 6–18 years of age with longer term programs (>24 weeks) of 2–3 days (most 3 days) per week, with sessions lasting 20–60 min/day, were reported to work better. The combination of aerobic plus resistance exercise was superior to aerobic training for reducing body adiposity. 20 , 21

Treatment of obesity in adolescence

Adolescence (10–19 years old, as defined by WHO) is a life stage of increased autonomy that expresses greater independence in decision making about food choices and other behaviors. However, parents continue to influence the dietary intake of adolescents as well as other behaviors by role modeling and through the home environment. 40 Recognizing the impact of foods and behaviors in changing relationship dynamics is an important consideration in the obesity management of adolescents. 10

In the Cochrane reviews (44 trials, 4781 participants), 7 the magnitude of behavior‐change lifestyle interventions in managing obesity in adolescents 12–17 years old (BMI: −1.49 kg/m2, six trials, 760 participants; BMI z‐score: −0.34 units, five trials, 602 participants; body weight: −3.67 kg, 20 trials, 1993 participants; low‐to‐moderate‐quality evidence) was similar with other younger age groups, and the effects of diet therapy were the same as that in multicomponent lifestyle interventions. 7 Most trials used multidisciplinary intervention approaches with a combination of diet, physical activity, and behavioral components. Optimal parental involvement was often integrated as age increased. It is important to highlight that obesity management for adolescents improved self‐esteem and body image in short and medium terms, with the improvement in self‐esteem independent of weight‐related outcomes. 7 Motivational interviewing was often incorporated to initiate weight management interventions for adolescents and parental involvement. 30 , 31

Although various intermittent fasting approaches may play a role in adolescent obesity control, there is insufficient evidence of benefit beyond adjunctive caloric reduction or energy‐balance activity intervention. Exercise training was moderately effective in reducing obesity and increasing lean body weight in adolescents. Although little research into novel lifestyle approaches for adolescents has been conducted, the concepts of focusing on health‐promoting behaviors at all stages of the weight management process, rather than a weight‐centric approach, are consistent with clinical guidelines. 41

Safety of behavior‐change lifestyle interventions

In the retrieved reviews, only the Cochrane reviews reported adverse events induced by lifestyle interventions. 5 , 6 , 7 No potential medical concerns occurred in terms of impaired height, linear growth, injury, allergies, or an increase in eating pathology. Quality of life and self‐esteem improved in some studies, while all‐cause mortality was seldom reported. In the recent non‐Cochrane reviews, few reported safety data on a high attrition rate or low compliance specifically. 22 , 28 , 34 However, effects on linear growth, behavior disorders, development of injury or allergy, and psychological well‐being, among others, should be considered in behavior‐change lifestyle interventions. In addition to potential physical and mental health benefits or harms, behavior changes may induce negative parent–child relationships or family conflicts during treatments, and children and adolescents may develop psychological issues related to the success or failure of the recommended intervention. 42 , 43

In diet/nutrition‐incorporated behavior‐change lifestyle interventions, adverse effects are the result of insufficient energy intake, fiber, or other nutrients; therefore, disruptions to balanced diet intakes should be considered. 14 , 15 , 44 No significant negative effects were reported in linear growth during the intervention and follow‐up in the reviews reporting adverse events. Potential adverse effects may be caused by reduced energy interventions such as metabolic disorders and eating disorders. 5 , 6 , 7 Energy‐restricted diet has low adherence, is not reliable for long‐term interventions, and must be conducted under the guidance of a dietician or another form of medical monitoring. Therefore, long‐term effects are difficult to ascertain.

Future research should focus on implementation strategies, including structured safety monitoring. 42 A focus on behavior change and overall well‐being may be more beneficial than obesity management per se in obesity treatment in children and adolescents. 43 , 45

How might behavior‐change lifestyle interventions work in obesity control and management?

Behavior‐change lifestyle interventions that aim to improve dietary intake, increase physical activity levels, and reduce sedentary behaviors are often prescribed as treatment options to create an energy deficit via adjunctive caloric reduction and/or energy‐balance behavior change. In children and adolescents, fostering healthy behaviors and lifestyles may be more meaningful than weight management. 10 Given the complexity of behavior‐change lifestyle interventions, it is important to identify the elements that facilitate long‐term behavior change and enable meaningful obesity reduction interventions.

Mediators and moderators of overall effect

A systematic review and meta‐analysis assessed the correlations of intervention characteristics in obesity management in children and adolescents. 46 The review reported that participant and intervention characteristics had little impact on the overall effect size. However, gender, age, duration of intervention, intervention type (behaviors targeted), intensities, intervention delivery, and comparators may influence the effect size. 46 Few studies reported gender differences in effect size. Behavior‐change lifestyle interventions produced a greater effect size in 0–6‐year‐olds than in 6–11‐year‐olds and 12–17‐year‐olds, with the least effect observed in 6–11‐year‐olds. 5 , 6 , 7 This suggests that childhood and adolescent obesity should be identified as early as possible for effective interventions. Adolescents seem to show a slightly major decrease in BMI than younger participants during lifestyle interventions.

Obesity treatment and weight maintenance interventions lasting 12 months or more resulted in a slightly bigger effect size. Family‐based interventions for 6–12‐year‐olds generally focus on parenting skills, and substantial parental involvement somewhat increases the intervention effect. Combined diet and physical activity interventions resulted in a higher effect size than any single component, but with overlapping confidence intervals among the intervention types. 46 Comprehensive, intensive interventions with a combination of diet and physical activity and behavior therapy showed improvement in BMI z‐score (−0.46 units), which is assumed to be effective in reducing cardiometabolic risks in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity. 46

Behavior‐change components

Behavior‐change strategies providing techniques to modify diet and physical activity patterns are key components in behavior‐change lifestyle interventions. Some commonly used techniques include goal setting (behavior or weight outcomes), stimulus control (modifying or restricting environmental influences), self‐monitoring (identifying behavioral patterns, targeting areas for change, and tracking progress toward goals in behavior and weight), and problem solving (analyzing challenges and developing effective solutions). 47 More than half of studies included in the Cochrane reviews on diet, physical activity, and behavioral treatment of childhood and adolescent obesity used behavioral therapy components with different levels of intensity that incorporated single or multiple BCTs. 45 Some selected reviews demonstrated that integrated psychological components improved the effects of community interventions. 35 Regarding values and preferences, the least valued component by patients is the burden of behavior‐change strategies (stimulus control and self‐monitoring). 45 Simpler guidance such as the traffic light food reminder is preferred. 48

Regarding the active components of successful BCTs for obesity management, a systematic review assessed BCTs from the 41 CALO‐RE taxonomy—a refined taxonomy of BCTs to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviors—used during behavior‐change obesity treatment RCTs in children and adolescents. This review reported that six BCTs may be the most effective components of obesity treatment interventions (e.g., the standardized difference in the mean value of BMI between groups at follow‐up was at least ≥−0.13 kg/m2). These are (1) providing information on the consequences of behavior to the individual, (2) environmental restructuring, (3) prompt practice, (4) prompt identification of role model/position advocate, (5) stress management/emotional control training, and (6) general communication skills training. 49 Evidence on the approaches of behavior‐change intervention that lead to sustained weight management in children and adolescents is currently limited. 2 , 47 , 50 , 51

Family/parent involvement

Family‐based multicomponent behavioral interventions have shown the most promise in improving weight status in children and adolescents with overweight or obesity. However, relatively little is known about the efficacy of specific characteristics of these multicomponent interventions or their efficacy for different subgroups of children and adolescents. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Given the importance of social support in family‐involved interventions, a mixed method evidence synthesis conducted in high‐income countries identified the critical features of successful weight management lifestyle interventions for children and adolescents 0–11 years old. The systematic review used qualitative comparative analysis to identify critical pathways to effectiveness conducted in Australia, New Zealand, North America, and Western Europe. The findings suggested that three important mechanisms are among the critical features of successful weight management lifestyle interventions for children and adolescents 0–11 years old with overweight: (1) providing families with physical activity sessions, practical behavior‐change strategy sessions, and calorie intake advice; (2) ensuring all family members are on board via delivering discussion/education sessions for children and adolescents and parents, delivering age‐appropriate sessions, and aiming to change behavior across the whole family; and (3) enabling social support for both children and adolescents and parents by delivering both child/adolescent group sessions and parent group sessions. The author stated that programs should encourage whole‐family involvement and show all members how to implement practices. 52

Motivational interviewing

Behavior‐change lifestyle interventions may also include motivational interviewing, which can help individuals make positive behavioral and cognitive changes and may facilitate adherence to health behaviors for managing obesity. Motivational interviewing is an evidence‐based counseling approach described as four processes: engaging, focusing, evoking, and planning. Motivational interviewing was used explicitly in clinics as a treatment intervention to strengthen adolescents’ commitment to choosing healthy lifestyles and managing their weight. 30 , 47 In clinics, motivational interviewing was also used at the parental decision‐making level to influence the lifestyle behaviors of young children under 10 years of age; however, more information is needed regarding the effects. 53 With complete participation and high implementation fidelity, motivational interviewing‐based interventions could produce small to medium effect sizes (SMD: −0.18 to −0.63) across a range of anthropometric outcomes in adolescents (BMI, waist circumference, and body fat percentage). Greater effects were reported in adolescent girls and adolescents with complete participation (≥11 years old; g = 0.22). 31 Additional investigation is needed to better sustain long‐term behavioral changes in children and adolescents. 31 , 54

Digital technology

Digital tools and technologies including games, eHealth, mHealth, and telehealth are increasingly used in behavior change and weight management. Some of the technologies have shown effects on obesity outcomes and on quality of life. However, the effects were small, and the quality of the evidence was low or very low (authors’ report). Further, well‐designed studies are needed before conclusions on the effect of digital technology on obesity management in children and adolescents can be made. 24 , 26 , 27 , 28

DISCUSSION

Main findings

Behavior‐change lifestyle interventions combining diet, physical activity intervention, and behavior‐change strategies may be useful for obesity treatment in children and adolescents. The quality of evidence is very low to low, and the effects are small to modest (the authors’ report). Long‐term intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions of 26 h or more total contact with sufficient parental involvement demonstrated better effects. Digital technologies were evaluated in some selected systematic reviews but the effects on childhood and adolescent obesity treatment are unclear. More well‐designed studies are needed on behavioral‐change lifestyle interventions for childhood and adolescent obesity treatment. In addition, some authors have drawn attention to the heterogeneity of the included studies in their systematic reviews and to the low quality of many primary studies, thus the translation of the evidence to policy should be cautious.

Side effects are infrequently reported across all intervention modalities. Monitored (called follow‐up) interventions between 2 weeks and 3 years did not show negative effects on linear growth, behavior disorders, or well‐being. However, there is a need for further studies assessing the safety of these interventions. Insufficient energy intake during nutritional interventions may cause an unbalanced diet and lead to related adverse effects. Long‐term physical development (linear growth), behavior disorders, quality of life, and the overall well‐being of children and adolescents should be prioritized throughout behavioral lifestyle interventions.

Importance

We identified reviews covering a wide variety of behavior‐change lifestyle interventions, including different components administered across multiple settings (e.g., school, family, community, and clinics). The observed moderate effects may have been influenced by study characteristics, implementation factors, and the social, economic, and cultural factors in the settings where it was conducted. Interventions should meet individual needs while considering contextual obesogenic factors. For children and adolescents, especially the latter, developmental characteristics may be the main determinants of efficacy and safety.

Safety data in behavior‐change lifestyle interventions in childhood and adolescent obesity treatment were infrequently reported in the reviews. Core safety data monitoring should be prioritized in the future, particularly potential adverse effects on linear growth, behavior disorders, body image, psychological well‐being, and family interactions. Structured monitoring systems and reporting templates should be further developed and implemented. 42

Comparisons

The findings of this overview of reviews are consistent with recent practice guidelines and similar reviews on obesity management for children and adolescents. Multidisciplinary lifestyle interventions that address diet, physical activity, and sedentary and sleep were widely recommended as the basis of all obesity treatment approaches in the world. 4 , 55 Ells et al. conducted an overview of the Cochrane systematic reviews on the effectiveness and risks of obesity treatment in children and adolescents. Authors reported that multicomponent behavior‐change lifestyle interventions may be beneficial in achieving small, short‐term reductions in BMI, BMI z‐score, and weight in children and adolescents 6–11 years old. Adverse events, health‐related quality of life, behavior‐change outcomes, and social demographics were poorly or inconsistently reported. 45 The authors concluded that there is low‐certainty evidence that lifestyle and behavioral interventions are effective for obesity management among children and adolescents with overweight or obesity. Safety data remain lacking across all intervention modalities. 42 Our findings are reflected in recommendations of various expert panels and current guidance in Australia, 51 the People's Republic of China, 56 the Republic of India, 57 the United States, 4 and some European countries, 58 among others.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is the systematic literature search of recent publications conducted, including a wide array of behavior‐change strategies/techniques targeting childhood and adolescent obesity treatment, and tracking the progress of lifestyle interventions. Novel therapies such as motivational interviewing and digital technologies (e.g., games, eHealth, mHealth, and telehealth, etc.) were also included.

The limitations of this study are related to the narrower inclusion criteria in the study design. This restriction may limit the uptake of interventions that may be useful for obesity management, but that cannot be assessed using a RCT study design (eligible for inclusion in the included systematic reviews). Interventions targeting behavior‐change per se (e.g., diet/energy intakes, healthy eating, and lifestyle promotion trials) were also left out. In addition, because of time constraints, data were extracted by a single reviewer, which may have resulted in some bias in data collection.

The low‐to‐moderate effect of behavior‐change lifestyle interventions reported in the reviews was mainly related to body weight, BMI, and BMI z‐score outcomes. The adequacy of BMI‐related indices in the evaluation of obesity reduction in children and adolescents should be exercised with caution because of their low discrimination of body fat change. 59 Nonetheless, a small change in these outcomes at the population level may have great significance in public health. In addition, obesity treatment in children and adolescents should focus more on health quality and overall well‐being of the child or adolescent instead of being confined to anthropometric measures. This review excluded cardiometabolic changes as a main outcome, however, the significance of reducing cardiometabolic risk, which is often experienced by children and adolescents with obesity, cannot be omitted from obesity treatment.

Implication for practice and future studies

Behavior‐change lifestyle intervention is fundamental in obesity therapies. A standard monitoring structure and critical techniques should be emphasized in intervention implementation. 9 , 55 The mechanisms of action of widely used behavior‐change strategies and their effectiveness are increasingly clear. Standard design and reporting pipelines are needed in further studies. These may improve efficacy, safety, and adherence to obesity treatment. Longer duration, better structuring, and parental participation seem to increase intervention efficacy.

CONCLUSIONS

Lifestyle interventions with behavior‐change components can effectively improve outcomes in children and adolescents with obesity. Behavior‐change treatments should be of high frequency (via frequent contact), of longer duration (26 h or more total contact), and incorporate psychological components and age‐appropriate parental involvement. Motivational interviewing and some BCTs are promising components of behavioral interventions for the treatment of obesity in children and adolescents, but their mechanisms of action need further study. Multitier social and environmental support systems are important for successful behavior‐change interventions.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Liubai Li, Feng Sun, Zhixia Li, and Jian Du were involved in study design and protocol development. Liubai Li, Feng Sun, Tianjiao Chen, Zhixia Li, and Xuanyu Shi led data abstraction and analysis. All authors critically reviewed and contributed to the manuscript.

DISCLAIMER

This manuscript was developed as input for the World Health Organization project “Integrated management of children and adolescents with obesity in all their diversity: a primary health care approach for improved health, functioning and reduced obesity‐associated disability.” This paper is being published individually but will be consolidated with other manuscripts as a special issue of Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, the coordinators of which were Maria Nieves Garcia‐Casal and Hector Pardo‐Hernandez. This special issue will provide insights to support the World Health Organization in developing practice and science‐informed, people‐centered guidelines on the integrated management of children 0–9 and adolescents 10–19 years of age in all their diversity with obesity using a primary health care approach. The special issue is the responsibility of the editorial staff of Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, who delegated to the coordinators preliminary supervision of both technical conformity to the publishing requirements of Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences and general oversight of the scientific merit of each article. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the World Health Organization, the publisher, or editorial staff of Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at: https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/nyas.15278

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Department of Nutrition and Food Safety at the World Health Organization (WHO) commissioned and provided financial support for this work. WHO acknowledges the financial support from the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), the Government of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, and the Government of Germany (BMG) to the Department of Nutrition and Food Safety.

Li, L. , Sun, F. , Du, J. , Li, Z. , Chen, T. , & Shi, X. (2025). Behavior‐change lifestyle interventions for the treatment of obesity in children and adolescents: A scoping review. Ann NY Acad Sci., 1543, 31–41. 10.1111/nyas.15278

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . (2017). Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity. Implementation plan: Executive summary (WHO). World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Styne, D. M. , Arslanian, S. A. , Connor, E. L. , Farooqi, I. S. , Murad, M. H. , Silverstein, J. H. , & Yanovski, J. A. (2017). Pediatric obesity—Assessment, treatment, and prevention: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 102, 709–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hassapidou, M. , Duncanson, K. , Shrewsbury, V. , Ells, L. , Mulrooney, H. , Androutsos, O. , Vlassopoulos, A. , Rito, A. , Farpourt, N. , Brown, T. , Douglas, P. , Ramos Sallas, X. , Woodward, E. , & Collins, C. (2023). EASO and EFAD position statement on medical nutrition therapy for the management of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents. Obesity Facts, 16, 29–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Browne, N. T. , & Cuda, S. E. (2022). Nutritional and activity recommendations for the child with normal weight, overweight, and obesity with consideration of food insecurity: An Obesity Medical Association (OMA) clinical practice statement 2022. Obesity Pillars, 2, 100012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Colquitt, J. L. , Loveman, E. , O'malley, C. , Azevedo, L. B. , Mead, E. , Al‐Khudairy, L. , Ells, L. J. , Metzendorf, M.‐I. , & Rees, K. (2016). Diet, physical activity, and behavioral interventions for the treatment of overweight or obesity in preschool children up to the age of 6 years. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3(3), CD012105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mead, E. , Brown, T. , Rees, K. , Azevedo, L. B. , Whittaker, V. , Jones, D. , Olajide, J. , Mainardi, G. M. , Corpeleijn, E. , O'malley, C. , Beardsmore, E. , Al‐Khudairy, L. , Baur, L. , Metzendorf, M.‐I. , Demaio, A. , & Ells, L. J. (2017). Diet, physical activity and behavioral interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese children from the age of 6 to 11 years. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6(6), CD012651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Al‐Khudairy, L. , Loveman, E. , Colquitt, J. L. , Mead, E. , Johnson, R. E. , Fraser, H. , Olajide, J. , Murphy, M. , Velho, R. M. , O'malley, C. , Azevedo, L. B. , Ells, L. J. , Metzendorf, M.‐I. , & Rees, K. (2017). Diet, physical activity and behavioral interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese adolescents aged 12 to 17 years. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6(6), CD012691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Loveman, E. , Al‐Khudairy, L. , Johnson, R. E. , Robertson, W. , Colquitt, J. L. , Mead, E. L. , Ells, L. J. , Metzendorf, M.‐I. , & Rees, K. (2015). Parent‐only interventions for childhood overweight or obesity in children aged 5 to 11 years. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(12), CD012008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tully, L. , Arthurs, N. , Wyse, C. , Browne, S. , Case, L. , Mccrea, L. , O'connell, J. M. , O'gorman, C. S. , Smith, S. M. , Walsh, A. , Ward, F. , & O'malley, G. (2022). Guidelines for treating child and adolescent obesity: A systematic review. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9, 902865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jebeile, H. , Kelly, A. S. , O'Malley, G. , & Baur, L. A. (2022). Obesity in children and adolescents: Epidemiology, causes, assessment, and management. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 10, 351–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carroll, C. , Sworn, K. , Booth, A. , & Pardo‐Hernandez, H. (2022). Stakeholder views of services for children and adolescents with obesity: Mega‐ethnography of qualitative syntheses. Obesity (Silver Spring), 30, 2167–2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liberati, A. , Altman, D. G. , Tetzlaff, J. , Mulrow, C. , Gøtzsche, P. C. , Ioannidis, J. P. A. , Clarke, M. , Devereaux, P. J. , Kleijnen, J. , & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62, e1–e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peters, M. D. J. , Godfrey, C. M. , Khalil, H. , Mcinerney, P. , Parker, D. , & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence‐Based Healthcare, 13, 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Andela, S. , Burrows, T. L. , Baur, L. A. , Coyle, D. H. , Collins, C. E. , & Gow, M. L. (2019). Efficacy of very low‐energy diet programs for weight loss: A systematic review with meta‐analysis of intervention studies in children and adolescents with obesity. Obesity Reviews, 20, 871–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ni, C. , Jia, Q. , Ding, G. , Wu, X. , & Yang, M. (2022). Low‐glycemic index diets as an intervention in metabolic diseases: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Nutrients, 14, 307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jakobsen, D. D. , Brader, L. , & Bruun, J. M. (2022). Effects of foods, beverages and macronutrients on BMI z‐score and body composition in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. European Journal of Nutrition, 62, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jazayeri, S. , Heshmati, J. , Mokhtari, Z. , Sepidarkish, M. , Nameni, G. , Potter, E. , & Zaroudi, M. (2020). Effect of omega‐3 fatty acids supplementation on anthropometric indices in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 53, 102487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Busnatu, S. S. , Serbanoiu, L. I. , Lacraru, A. E. , Andrei, C. L. , Jercalau, C. E. , Stoian, M. , & Stoian, A. (2022). Effects of exercise in improving cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight children: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Healthcare, 10, 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Erçelik, Z. E. , & Çağlar, S. (2022). Effectiveness of active video games in overweight and obese adolescents: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Annals of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism, 27, 98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li, D. , & Chen, P. (2021). The effects of different exercise modalities in the treatment of cardiometabolic risk factors in obese adolescents with sedentary behavior—A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Children, 8, 1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. García‐Hermoso, A. , Ramírez‐Vélez, R. , Ramírez‐Campillo, R. , Peterson, M. D. , & Martínez‐Vizcaíno, V. (2018). Concurrent aerobic plus resistance exercise versus aerobic exercise alone to improve health outcomes in paediatric obesity: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52, 161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kelley, G. A. , Kelley, K. S. , & Pate, R. R. (2017). Exercise and BMI z‐score in overweight and obese children and adolescents: A systematic review and network meta‐analysis of randomized trials. Journal of Evidence‐Based Medicine, 10, 108–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Azevedo, L. B. , Ling, J. , Soos, I. , Robalino, S. , & Ells, L. (2016). The effectiveness of sedentary behavior interventions for reducing body mass index in children and adolescents: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews, 17, 623–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ameryoun, A. , Sanaeinasab, H. , Saffari, M. , & Koenig, H. G. (2018). Impact of game‐based health promotion programs on body mass index in overweight/obese children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Childhood Obesity, 14, 67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suleiman‐Martos, N. , García‐Lara, R. A. , Martos‐Cabrera, M. B. , Albendín‐García, L. , Romero‐Béjar, J. L. , Cañadas‐De La Fuente, G. A. , & Gómez‐Urquiza, J. L. (2021). Gamification for the improvement of diet, nutritional habits, and body composition in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Nutrients, 13, 2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Azevedo, L. B. , Stephenson, J. , Ells, L. , Adu‐Ntiamoah, S. , DeSmet, A. , Giles, E. L. , Haste, A. , O'Malley, C. , Jones, D. , Chai, L. K. , Burrows, T. , & Hudson, M. (2021). The effectiveness of e‐health interventions for the treatment of overweight or obesity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews, 23, e13373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Darling, K. E. , & Sato, A. F. (2017). Systematic review and meta‐analysis examining the effectiveness of mobile health technologies in using self‐monitoring for pediatric weight management. Childhood Obesity, 13, 347–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Margetin, C. A. , Rigassio Radler, D. , Thompson, K. , Ziegler, J. , Dreker, M. , Byham‐Gray, L. , & Chung, M. (2021). Anthropometric outcomes of children and adolescents using telehealth with weight management interventions compared to usual care: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of the American Nutrition Association, 41, 207–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lopez, P. , Taaffe, D. R. , Galvão, D. A. , Newton, R. U. , Nonemacher, E. R. , Wendt, V. M. , Bassanesi, R. N. , Turella, D. J. P. , & Rech, A. (2022). Resistance training effectiveness on body composition and body weight outcomes in individuals with overweight and obesity across the lifespan: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews, 23, e13428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Amiri, P. , Mansouri‐Tehrani, M. M. , Khalili‐Chelik, A. , Karimi, M. , Jalali‐Farahani, S. , Amouzegar, A. , & Kazemian, E. (2021). Does motivational interviewing improve the weight management process in adolescents? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29, 78–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kao, T.‐S. A. , Ling, J. , Hawn, R. , & Vu, C. (2021). The effects of motivational interviewing on children's body mass index and fat distributions: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews, 22, e13308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Scott‐Sheldon, L. A. J. , Hedges, L. V. , Cyr, C. , Young‐Hyman, D. , Khan, L. K. , Magnus, M. , King, H. , Arteaga, S. , Cawley, J. , Economos, C. D. , Haire‐Joshu, D. , Hunter, C. M. , Lee, B. Y. , Kumanyika, S. K. , Ritchie, L. D. , Robinson, T. N. , & Schwartz, M. B. (2020). Childhood obesity evidence base project: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of a new taxonomy of intervention components to improve weight status in children 2–5 years of age, 2005–2019. Childhood Obesity, 16, S2‐21–S2‐48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Salam, R. A. , Padhani, Z. A. , Das, J. K. , Shaikh, A. Y. , Hoodbhoy, Z. , Jeelani, S. M. , Lassi, Z. S. , & Bhutta, Z. A. (2020). Effects of lifestyle modification interventions to prevent and manage child and adolescent obesity: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Nutrients, 12, 2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van der Heijden, L. B. , Feskens, E. J. M. , & Janse, A. J. (2018). Maintenance interventions for overweight or obesity in children: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews, 19, 798–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moores, C. J. , Bell, L. K. , Miller, J. , Damarell, R. A. , Matwiejczyk, L. , & Miller, M. D. (2018). A systematic review of community‐based interventions for the treatment of adolescents with overweight and obesity. Obesity Reviews, 19, 698–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pongutta, S. , Ajetunmobi, O. , Davey, C. , Ferguson, E. , & Lin, L. (2022). Impacts of school nutrition interventions on the nutritional status of school‐aged children in Asia: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Nutrients, 14, 589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li, B. , Gao, S. , Bao, W. , & Li, M. (2022). Effectiveness of lifestyle interventions for treatment of overweight/obesity among children in China: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 13, 972954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hens, W. , Vissers, D. , Hansen, D. , Peeters, S. , Gielen, J. , Van Gaal, L. , & Taeymans, J. (2017). The effect of diet or exercise on ectopic adiposity in children and adolescents with obesity: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews, 18, 1310–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Salam, R. A. , Padhani, Z. A. , Das, J. K. , Shaikh, A. Y. , Hoodbhoy, Z. , Jeelani, S. M. , Lassi, Z. S. , & Bhutta, Z. A. (2020). Effects of lifestyle modification interventions to prevent and manage child and adolescent obesity: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Nutrients, 12, 2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Miller, A. L. , Lo, S. L. , Bauer, K. W. , & Fredericks, E. M. (2020). Developmentally informed behavior change techniques to enhance self‐regulation in a health promotion context: A conceptual review. Health Psychology Review, 14, 116–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Steinbeck, K. S. , Lister, N. B. , Gow, M. L. , & Baur, L. A. (2018). Treatment of adolescent obesity. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 14, 331–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gates, A. , Caldwell, P. , Curtis, S. , Dans, L. , Fernandes, R. M. , Hartling, L. , Kelly, L. E. , Vandermeer, B. , Williams, K. , Woolfall, K. , & Dyson, M. P. (2019). Reporting of data monitoring committees and adverse events in paediatric trials: A descriptive analysis. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 3, e000426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gates, A. , Elliott, S. A. , Shulhan‐Kilroy, J. , Ball, G. D. C. , & Hartling, L. (2021). Effectiveness and safety of interventions to manage childhood overweight and obesity: An overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. Paediatrics & Child Health, 26, 310–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schwingshackl, L. , Hobl, L. P. , & Hoffmann, G. (2015). Effects of low glycaemic index/low glycaemic load vs. high glycaemic index/high glycaemic load diets on overweight/obesity and associated risk factors in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Nutrition Journal, 14, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ells, L. J. , Rees, K. , Brown, T. , Mead, E. , Al‐Khudairy, L. , Azevedo, L. , Mcgeechan, G. J. , Baur, L. , Loveman, E. , Clements, H. , Rayco‐Solon, P. , Farpour‐Lambert, N. , & Demaio, A. (2018). Interventions for treating children and adolescents with overweight and obesity: An overview of Cochrane reviews. International Journal of Obesity, 42, 1823–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kobes, A. , Kretschmer, T. , Timmerman, G. , & Schreuder, P. (2018). Interventions aimed at preventing and reducing overweight/obesity among children and adolescents: A meta‐synthesis. Obesity Reviews, 19, 1065–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Freshwater, M. , Christensen, S. , Oshman, L. , & Bays, H. E. (2022). Behavior, motivational interviewing, eating disorders, and obesity management technologies: An Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) clinical practice statement (CPS) 2022. Obesity Pillars, 2, 100014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Epstein, L. H. , & Squires, S. (1988). The stop light diet for children: An eight‐week program for parents and children. Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Martin, J. , Chater, A. , & Lorencatto, F. (2013). Effective behavior change techniques in the prevention and management of childhood obesity. International Journal of Obesity, 37, 1287–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mihrshahi, S. , Gow, M. L. , & Baur, L. A. (2018). Contemporary approaches to the prevention and management of paediatric obesity: An Australian focus. Medical Journal of Australia, 209, 267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sutin, A. R. , Boutelle, K. , Czajkowski, S. M. , Epel, E. S. , Green, P. A. , Hunter, C. M. , Rice, E. L. , Williams, D. M. , Young‐Hyman, D. , & Rothman, A. J. (2018). Accumulating data to optimally predict obesity treatment (ADOPT) core measures: Psychosocial domain. Obesity, 26, S45–S54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Burchett, H. E. D. , Sutcliffe, K. , Melendez‐Torres, G. J. , Rees, R. , & Thomas, J. (2018). Lifestyle weight management programmes for children: A systematic review using qualitative comparative analysis to identify critical pathways to effectiveness. Preventive Medicine, 106, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Suire, K. B. , Kavookjian, J. , & Wadsworth, D. D. (2020). Motivational interviewing for overweight children: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 146(5), e20200193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kao, T.‐S. A. , Ling, J. , Vu, C. , Hawn, R. , & Christodoulos, H. (2023). Motivational interviewing in pediatric obesity: A meta‐analysis of the effects on behavioral outcomes. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 57, 605–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lister, N. B. , Baur, L. A. , Felix, J. F. , Hill, A. J. , Marcus, C. , Reinehr, T. , Summerbell, C. , & Wabitsch, M. (2023). Child and adolescent obesity. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 9, 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Revision Committee of Guideline of Child Obesity Prevention and Control . (2021). Guideline of child obesity prevention and control. People's Medical Publishing House Co., LTD. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mittal, M. , & Jain, V. (2021). Management of obesity and its complications in children and adolescents. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 88, 1222–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hassapidou, M. , Duncanson, K. , Shrewsbury, V. , Ells, L. , Mulrooney, H. , Androutsos, O. , Vlassopoulos, A. , Rito, A. , Farpourt, N. , Brown, T. , Douglas, P. , Ramos Sallas, X. , Woodward, E. , & Collins, C. (2022). European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) position statement on medical nutrition therapy for the management of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents developed in collaboration with the European Federation of the Associations of Dietitians (EFAD). Obesity Facts, 08, 08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Freedman, D. S. , Butte, N. F. , Taveras, E. M. , Lundeen, E. A. , Blanck, H. M. , Goodman, A. B. , & Ogden, C. L. (2017). BMI z‐scores are a poor indicator of adiposity among 2‐ to 19‐year‐olds with very high BMIs, NHANES 1999–2000 to 2013–2014. Obesity (Silver Spring), 25, 739–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Supporting Information