Abstract

The appearance of antiviral therapy has led to a change in the prognosis and clinical manifestations of patients with human immunodeficiency virus infections and Kaposi’s sarcoma. However, there are still countries in which access is inadequate and the disease progresses toward disseminated forms with an unfavorable outcome. We present two patients who presented with skin lesions that progressed for a month, compatible with disseminated Kaposi’s sarcoma in the context of HIV. One month after starting treatment, they were admitted for multi-organ failure associated with an Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome and eventually died.

Keywords: HIV, Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, SK-Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome

Introduction

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) has been classically defined as a paradoxical worsening of known and previously treated or subclinical infections in HIV patients who have recently initiated antiviral therapy (ART).[1] However, patients who also have Kaposi’s sarcoma may experience a similar syndrome without underlying infectious complication (SK-IRIS). We added a second case to a previously published one of disseminated Kaposi sarcoma with unknown HIV infection and SK-IRIS in its evolution.[1]

Case Reports

Case 1

A 35-year-old male, originally from Brazil, attended the emergency department with fever, progressive skin lesions and a loss of 5 kg in the last month.

On examination, erythematous-violaceous asymptomatic plaques and nodules were observed, with a firm consistency, which were distributed linearly and bilaterally on the trunk, upper, and lower limbs [Figure 1]. Cervical lymphadenopathy was palpable.

Figure 1.

Infiltrated erythematous-violaceous plaques distributed symmetrically on the trunk, and upper and lower limbs in the patient of case 1

Blood tests showed pancytopenia (hemoglobin 6.50 g/dL, leukocytes 2.74 × 10^9/L, absolute lymphocytes 0.56 × 10^9/L, and platelets 85 × 10^9/L) and splenomegaly was detected by ultrasound. The bone marrow aspirate ruled out a myeloproliferative syndrome, and the study using blood cultures, skin biopsy cultures, and serologies revealed an unknown HIV infection.

Biopsies of the skin [Figure 2], bone marrow, and lymph node were performed [Figures 3 and 4], all of them compatible with disseminated Kaposi’s sarcoma, so treatment with tenofovir/bictegravir/emtricitabine and liposomal doxorubicin was started.

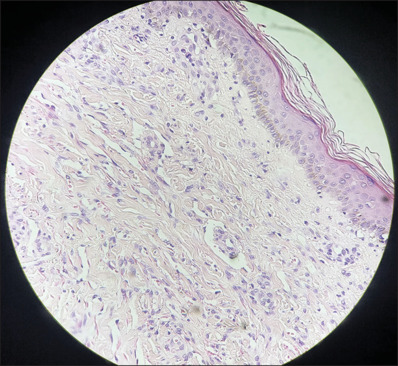

Figure 2.

Histology section corresponding to patient 1’s skin biopsy. A proliferation of small vessels in the superficial dermis can be observed, along with blood extravasation and lymphohistocytic infiltrate. The classic “prontorium sign” is present, where the walls of the vessels are dissected by the new vascular structures (H and E, ×10)

Figure 3.

The histology section corresponds to a lymph node from patient 1, where destructuring of the lymph node architecture with the appearance of vascular structures is observed (H and E, ×5)

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical technique with positive Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus marker performed on lymph node sections

One month into treatment, the patient was admitted due to deterioration in general condition, worsening skin lesions, and anasarca. The CT scan revealed pulmonary opacities [Figure 5], and the study was extended to rule out sepsis of unknown origin, with a negative result. Finally, a SK-IRIS diagnosis was made, and the patient died from multiple organ failure.

Figure 5.

Chest computed tomography image of patient 1 showing pulmonary infiltrates in the setting of SK-SIRI

Case 2

A 45-year-old male, originally from Ecuador, came to the hospital because of the appearance of lesions consisting of indurated erythematous-violet plaques on the trunk, face (nasal and mandibular level), and extremities that had been present for 1 month [Figure 6]. In the extension study, unknown syphilis and HIV were diagnosed, so it was suggested that it could be an epidemic Kaposi’s sarcoma. However, the skin biopsy was inconclusive, as no KSHV was found by immunohistochemistry in the sample, suggesting a possible benign lymphangioendothelioma, which is the reason why the patient only started treatment with antiviral therapy.

Figure 6.

Skin lesions with similar characteristics to the previous patient, in the male of case 2

The patient was admitted on two occasions due to an immune reconstitution syndrome. On the second occasion, pulmonary infiltrates, pleural effusion, and lymphadenopathy were evident, so the skin biopsy was repeated, which was compatible with Kaposi’s sarcoma, as was the study of the sample obtained through bronchoscopy. The patient finally died due to a progressive deterioration a few days after admission.

Discussion

The term IRIS is described as a series of inflammatory disorders that trigger a paradoxical worsening of preexisting infectious processes (whether previously diagnosed and treated or masked) after the initiation of Antiretroviral therapy (TAR) in people with HIV.[1] Some of the microorganisms implicated are Mycobacterium tuberculosis and avium, Cytomegalovirus, Cryptococcus neoformans, or Pneumocystis jirovecii and low CD4 levels, high viral load at the time of diagnosis, rapid immunological improvement and fungal infections have been described as risk factors.[2]

On the other hand, patients with a recent diagnosis of Kaposi’s sarcoma may suffer from a similar syndrome, known as KS-IRIS, in which an infectious complication is not determined. This is defined as an abrupt worsening of KS, in the first 6 months after starting or modifying the TAR dose; understood as an increase in the size, number or pain of skin lesions, appearance or exacerbation of lymphedema and extension to other organs. In addition, the symptoms are accompanied by a reduction in the HIV viral load (at least 1 log10 of HIV-1 RNA) and/or an increase in the CD4 lymphocyte count (≥50 cells/mm3 or ≥ two-fold increase in the count basal cell CD4).[3]

It is difficult to establish the incidence of SK-IRIS because data differ by geographic area and type of study. Advanced KS tumor stage, HIV viral load >5 log10 copies/mL, detectable KSHV, and initiation of TAR without simultaneous chemotherapy have been determined as risk factors.[4]

In cases where it appears, TAR should not be suspended, and the patient should start systemic chemotherapy if they had not previously started it. Liposomal anthracyclines (liposomal doxorubicin) are considered the first choice and, as an alternative, paclitaxel. On the other hand, systemic corticosteroids would be contraindicated. A case–control study established a higher rate of SK-IRIS in patients who received systemic glucocorticoids (54.90% vs. 36.47%, P = 0.0474 and odds ratio (OR): 2.362, 1.08380–5.149 95% confidence interval (CI), P = 0. 0306). Likewise, its use has been related to higher mortality (OR: 4.719, 1.383–16.103 95% CI, P = 0.0132).[5]

In cases in which the symptoms are accompanied by cachexia, hypoalbuminemia, and hyponatremia, among others, a differential diagnosis must be made with Kaposi’s sarcoma inflammatory cytokine syndrome (KICS) and multicentric Castleman disease. The appearance of KICS symptoms is not temporally associated with the initiation of TAR, HIV, and KSHV viral load remains high and CD4 levels remain low (<100 cells/μL). For its part, multicentric Castleman disease must be confirmed with a histological study of a lymph node that will show hypocellular germinal centers and polyclonal plasmacytoid cells infected by KSHV in the interfollicular area. In this case, the HIV viral load must not be high and CD4 levels can be >200 cells/μL.[6,7]

Conclusion

We present two patients with a recent diagnosis of HIV-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma who had a poor outcome due to an IRIS. Although infrequent, SK-SIRI is a feared complication that must be taken into account in highly immunosuppressed patients with severe SK involvement who have recently started ART.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

Nil.

References

- 1.Vila-Cobreros L, Dios-Guillán V, Fernández-Romero C, Carmona-Ramón R. Diagnosis of HIV by Appearance of Facial Violaceous Macules, Clinical Cases of Residents of Dermatology. Editorial AEDV and Almirall. 2023:382–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant PM, Komarow L, Andersen J, Sereti I, Pahwa S, Lederman MM, et al. Risk factor analyses for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a randomized study of early versus deferred ART during an opportunistic infection. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volkow P, Cesarman-Maus G, Garciadiego-Fossas P, Rojas-Marin E, Cornejo-Juárez P. Clinical characteristics, predictors of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome and long-term prognosis in patients with Kaposi sarcoma. AIDS Res Ther. 2017;14:30. doi: 10.1186/s12981-017-0156-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poizot-Martin I, Brégigeon S, Palich R, Marcelin AG, Valantin MA, Solas C, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome associated Kaposi sarcoma. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:986. doi: 10.3390/cancers14040986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernández-Sánchez M, Iglesias MC, Ablanedo-Terrazas Y, Ormsby CE, Alvarado-de la Barrera C, Reyes-Terán G. Steroids are a risk factor for Kaposi’s sarcoma-immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome and mortality in HIV infection. AIDS. 2016;30:909–14. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polizzotto MN, Uldrick TS, Wyvill KM, Aleman K, Marshall V, Wang V, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with symptomatic Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV)-associated inflammation: Prospective characterization of KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome (KICS) Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:730–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cantos VD, Kalapila AG, Ly Nguyen M, Adamski M, Gunthel CJ. Experience with Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus inflammatory cytokine syndrome in a large urban HIV clinic in the United States: Case series and literature review. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx196. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]