Abstract

Téa Collins and colleagues argue that evidence based digital health can improve access to and the quality of integrated care, especially in low and middle income countries

The past decade has seen rapid growth in the use of information and communications technologies in healthcare worldwide. The covid-19 pandemic further accelerated the uptake of digital health, with the average growth of internet traffic in 2020 of 48% compared with pre-pandemic forecasts of average annual growth between 2016 and 2020 of 30%.1 The effective use of adequately designed digital health technologies (box 1) has the potential to strengthen health systems and reduce health inequalities.2 Digital health may increase access to and the quality of healthcare, particularly in remote areas; improve opportunities for integrated services throughout the life course; support healthcare workers in clinical decision making and facilitate their interactions with patients; and strengthen data collection and management for improved surveillance.

Box 1. Definitions of digital health and related interventions.

Digital health—An umbrella term referring to the systematic application of information and communications technologies, computer science, and data to support informed decision making by individuals, the health workforce, and health systems, towards strengthening resilience to disease and improving health and wellness5

eHealth (electronic health)—Use of information and communications technologies in support of health and health related fields, including healthcare services, health surveillance, health literature, and health education, knowledge, and research6

Telemedicine —Provision of healthcare services at a distance through telecommunications platforms (eg, patient evaluation or diagnosis through online consultations)7

Telemonitoring —Remote monitoring of patients’ health or diagnostic data enabled by digital technologies (eg, implanted sensors)8

Digital therapeutics—Evidence based treatments delivered using digital technologies (eg, smart inhalers for respiratory conditions or continuous glucose monitors for diabetes)8

mHealth (mobile health)— A component of eHealth. It refers to the use of mobile and wireless technologies to support health objectives9

The 2018 resolution on digital health adopted by the 71st World Health Assembly recognised the value of digital health technologies in supporting the sustainable development goals (SDGs) and universal health coverage (UHC).3 Building on this resolution, in 2019 the World Health Organization developed a global strategy on digital health, setting out a framework for action to scale up digital health globally and at national and sub-national levels.4

Digital health technologies have an important role in expanding patient centred, integrated care to prevent and control non-communicable diseases. Management of long term conditions involves complex interventions, and digital health technologies can facilitate better integrated care across levels and providers throughout the life span, including as part of maternal, newborn, and child health services. We use the examples of Vietnam and Kyrgyzstan to discuss how digital health technologies can enhance access to and the quality of integrated services for non-communicable diseases and maternal and child health, and suggest priority areas for action to increase the positive effect of digital health and help reduce some of its limitations, especially in low and middle income countries.

Benefits of digital health for integrated care

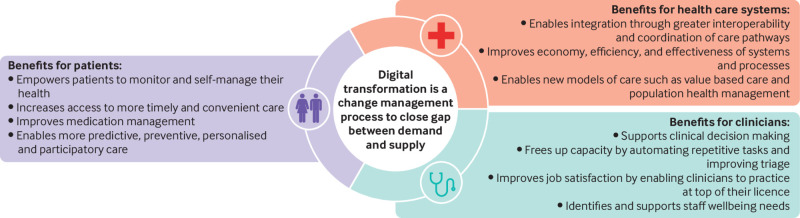

Within the context of integrated services for non-communicable diseases and maternal, newborn, and child health, digital transformation is not merely about new technology. It is about the development and adoption of appropriate, accessible, affordable, scalable, and sustainable person centred digital health solutions to change processes and improve the efficiency and quality of integrated care for the benefit of patients, healthcare providers, and the health system as a whole (fig 1).10

Fig 1.

Benefits of digital transformation (reproduced with permission10)

At the patient level, digital health technologies can promote healthy behaviours and enhance preventive care for women of reproductive age who are at risk of or living with non-communicable diseases.11 12 13 As an example, around 260 million women have diabetes globally, and it is becoming the most common pre-existing medical condition complicating pregnancies, leading to miscarriages, maternal and perinatal death, and congenital malformations.14 Optimal preconception health education and care for women of reproductive age and their partners can increase the chances of safe motherhood and the birth of a healthy infant.15 However, less than half of women in low and middle income countries receive preconception advice. Systemic barriers to accessing preconception care can be reduced through the use of digital health applications designed to address the challenges of distance, cost, waiting time, and availability of specialised care.7 14

At the provider level, several improvements to the quality of integrated care have been made possible by digital health interventions in low and middle income countries. For instance, digital technologies can improve providers’ ability to register patients’ data and better monitor their care through electronic medical records.16 17 In areas with a shortage of qualified mental health professionals, digital technologies can facilitate remote training for local community health workers to help identify and treat common mental health problems during pregnancy. Telemedicine can also reduce treatment gaps by connecting patients in rural or underserved communities to qualified providers through their smartphones.18 19 20

At the health system level, digital health technologies bring unique opportunities for improving access to and the quality of integrated care. In particular, robust electronic health records simplify the planning, execution, and evaluation of interventions during pregnancy.19 Moreover, integrating digital health interventions into antenatal care along with better streamlined services saves lives and resources, especially in low and middle income countries.20 For example, it was estimated that scaling up the mCare programme in Bangladesh could prevent as many as 3076 deaths among new mothers and infants from 2018 to 2027 at an incremental cost of $43m over the 10 years.21 The digital intervention package with both supply side and demand side promotion components includes pregnancy surveillance using a mobile phone based system by government community health workers and automated SMS and home visit reminders to pregnant women sent before scheduled antenatal visits. However, initial investments are needed to establish a sustainable financing model.22 23 24

Interviews with healthcare providers from Vietnam and Kyrgyzstan, conducted as part of a WHO assessment for its project to improve the quality of hospital care to reduce maternal, newborn, and child deaths, highlight the perceived benefits and challenges of using digital interventions to integrate maternal and child care with that for non-communicable diseases (boxes 2 and 3). Table 1 provides an overview of the digital interventions implemented in the two countries at the time of the assessment.

Box 2. Digital health technology in Vietnam.

Vietnam, with a population of about 99 million, has experienced substantial economic growth over the past 20 years, with the annual per capita earnings rising 2.7-fold between 2002 and 2020, and reaching almost $2800 (£2200; €2500) in 2022. Between 1990 and 2015, Vietnam reduced its maternal and infant mortality by 60%, from 139 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births in 1990 to 54 in 2015. Non-communicable diseases currently account for 77% of all deaths. The healthcare system in Vietnam is mixed public and private, with a large portion of services being delivered through public hospitals. Health coverage is provided to 90% of Vietnam’s population and is targeted to reach 95% by 2025.25 26 27

Perceived benefits

Interviewed healthcare providers from several hospitals reported having observed shorter waiting times for patients when digital technologies were used. Further reported benefits included improvements in the early detection of non-communicable diseases, treatment coordination, and information sharing between providers, which enhanced overall case management and helped prevent pregnancy complications. Overall, respondents thought digital health had made it easier for mothers and children to access the healthcare system.

Perceived challenges

Hospital staff reported facing several challenges during Vietnam’s digital transition, including inadequate information and communications technology infrastructure, insufficient technical support, limited existing technical knowledge, and inadequate data storage. Limited use of digital applications by healthcare providers, lack of funding, and poor health literacy in the community were also mentioned as important challenges

Box 3. Digital health technology in Kyrgyzstan .

Kyrgyzstan is a lower middle income country with a population of 6.6 million and a gross domestic profit (GDP) of $1166 per capita. It has made large investments in its primary care system for the past 30 years, spending 8% of GDP on healthcare. Between 1996 and 2016, the average life expectancy increased from 66.5 years to 71 years. However, non-communicable diseases account for 80% of all deaths in Kyrgyzstan, posing a serious economic burden, equivalent to about a 3.9% loss of GDP every year.28 29

Perceived benefits

Interviewed hospital staff in Kyrgyzstan reported observing several major benefits as the health system becomes more digitalised, including reduced waiting times for patients and time saved by providers both in the documentation and in deciphering illegible handwriting. Other advantages include fewer lost files, better continuity of care, and case management. The availability of telemedicine and greater capacity for staff training were also reported as important benefits of the digitalisation process. One respondent had been involved in developing and adopting a mobile app for parents on child development, designed to provide parents with expert advice on child health and development, including nutrition, breastfeeding, early learning, the importance of play, responsible parenting, and child protection and safety.

Perceived challenges

Major reported challenges to the implementation of digital interventions include low health literacy, discomfort among older staff using new technologies, and poor quality of information provided by patients. Infrastructure barriers such as unreliable internet connection and lack of computer equipment and technical support were also reported as challenges to digital transformation. Finally, the loss of “live” contact between doctors and patients was an additional challenge.

Table 1.

Digital health interventions at the patient, provider, and health system levels in Vietnam and Kyrgyzstan

| Level | Vietnam | Kyrgyzstan |

|---|---|---|

| Patient | ▪ Citizen based reporting/citizen report cards ▪ Targeted patient communications ▪ Personal health tracking |

▪ Citizen based reporting/citizen report cards ▪ Targeted and untargeted patient communications ▪ Patient-to-patient communications ▪ Patient financial transactions |

| Provider | ▪ Laboratory and diagnostics imaging management ▪ Electronic patient identification, registration, and health records, including population databases (eg, for diabetes, cancers, or cardiovascular diseases) ▪ Health provider decision support (including through telemedicine) ▪ Referral to specialised services for coordinated continuous care and effective follow-up ▪ Adherence of healthcare services to care plans, guidelines, and protocols ▪ Prescription and medication management ▪ Assessment of capacity of healthcare provider(s) |

▪ Laboratory and diagnostics imaging management ▪ Electronic patient identification, registration, and health records, including population databases (eg, for diabetes, cancers, or cardiovascular diseases) ▪ Healthcare provider decision support (including through telemedicine) ▪ Referral to specialised services for continuous care and effective follow-up ▪ Adherence of service delivery to care plans, guidelines, and protocols ▪ Scheduling and activity planning for healthcare providers ▪ Prescription and medication management ▪ Healthcare provider training ▪ Supportive supervision, and appraisal for performance improvement |

| Health system | ▪ Public health event notification ▪ Human resource, supply chain, and equipment and asset management ▪ Civil registration and vital statistics ▪ Health financing |

▪ Public health event notification ▪ Facility, human resource, supply chain, and equipment and asset management ▪ Civil registration and vital statistics ▪ Health financing |

Digital health is not a panacea

Although digital health technologies have the potential to enhance integrated non-communicable disease and maternal, newborn, and child care in low and middle income countries, big challenges remain. Like other health interventions, digital health has its limitations. Firstly, as countries are promoting greater adoption of digital health, the challenge remains to ensure that everyone has unimpeded access to information and communications technologies. In 2019, 89% of households in high income countries were using the internet versus less than 10% in low and middle income countries. In Africa, mobile devices cost around 63% of the average monthly income. Globally, nearly 2.5 billion people live in countries where the cost of the cheapest smartphone is more than 25% of an average monthly income.30 Within countries, a digital divide can exist between urban and rural populations, educated and uneducated individuals, and different socioeconomic groups.

Secondly, digital health cannot fix broken healthcare systems; nor can it entirely replace in-person care.31 Digital interventions that fail to connect patients to a high functioning continuum of care are not only unpopular but ineffective.20 32 Moreover, digital health is limited by its users’ digital health literacy, willingness to use digital health applications,33 34 35 and sociocultural or accessibility barriers. Hence, digital health is only as useful as patients’ and providers’ ability to use it, and interventions designed without engaging end users may exacerbate health disparities rather than reduce them.36 37 Digital health should be seen as a tool to strengthen patients’ relationships with providers and enhance their engagement with the healthcare system.38

Another shortcoming of many digital health interventions is that they are developed as pilot projects with no long term planning for their integration into the existing architecture of national health systems.24 31 39 40 If created in a silo without sustainable supporting infrastructure or funding, and in the absence of a conducive governance environment, digital interventions are destined for eventual failure, especially in low and middle income countries, where the cost effectiveness of solutions and digital literacy constitute major obstacles to digital health transformation.34 41 Furthermore, many digital health interventions for the prevention and management of non-communicable diseases have not been rigorously evaluated, and best practices are yet to be identified.21 42

Priorities for realising the potential of digital health

We propose three priority areas for action that policy makers should consider to scale up the effective use of digital health technologies at national level.

Establish and strengthen governance and financing mechanisms

National digital health strategies and policies need to encourage intersectoral cooperation to break down silos by involving all relevant stakeholders from the start. The cooperation of the public and private sectors can offer sustainable funding, supportive infrastructure, and technical know-how to scale up sustainable solutions that are well aligned with local culture and socioeconomic, legal, and regulatory environments, as well as local health needs and health system capabilities (box 4).

Box 4. Cooperation of Ethiopian government and consortium of partners to scale up digital health2 .

Ethiopia, as the fastest growing economy in Africa and the second most populous country in the region with more than 117 million people, aims to reach lower middle income status by 2025 and achieve the sustainable development goals by 2030. As part of the country’s ambitious growth agenda, in August 2020 the Ethiopian Ministry of Health launched a Digital Health Innovation and Learning Centre, where experts can develop digital health tools, promote best practices, and scale up innovations.

In May 2021, the government awarded a telecom licence to a consortium of companies (Vodafone and Vodacom, the British development finance agency CDC Group, and Japan’s Sumitomo Corporation) that plans to create jobs for 1.5 million citizens and invest more than $8bn in upgrading digital health infrastructure and facilitate access to quality healthcare for all Ethiopians.

Improve digital health literacy and willingness to use digital health technologies

As well as easy access, the success of digital health interventions depends on end users’ digital health literacy and willingness to use digital health applications. These two elements can be enhanced through education campaigns, digital training, ongoing support for technologies, and by involving end users (eg, patients, communities, healthcare workers, and public health practitioners) in all stages of digitalisation. End user involvement can also foster trust in digital solutions, which is critical for discussions around data ownership and management. Monetary compensation of healthcare providers for learning new skills and successfully incorporating digital interventions into clinical practice could be considered to counter barriers to participating in training, such as lack of motivation or time taken away from paid employment. As an example, a qualitative study of challenges and prospects for implementation of community health volunteers’ digital health solutions in Kenya suggests that extra motivation for users, including performance based remuneration, may facilitate the adoption of digital solutions.42

Several successful digital health programmes also have technical support in place so that learning can be an ongoing process. For example, South Africa’s MomConnect, a national text message based pregnancy support app, includes a 24 hour help desk to provide pregnant women with human connection and technology support, which has contributed to the programme’s popularity and success.43 Such support systems require sustainable funding but are necessary to address and overcome the digital divide.

Encourage interdisciplinary implementation research and evaluation

Research and academic institutions need to be engaged to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of existing digital health interventions and generate evidence on new cost effective solutions from the wide range of options that digital health has to offer. This evidence will be used to identify best practices, support the decision making of policy makers, and encourage investments. The growing interest in digital health technologies in the past decade, accelerated by the covid-19 pandemic, has stimulated several studies to test and evaluate digital solutions for integrated care.44 45 46 47 However, further systematic and interdisciplinary research is required to identify and validate cost effective solutions that can be implemented in low and middle income countries.

Conclusion

Digital health technologies have the potential to improve access to and quality of integrated services for non-communicable diseases and maternal and child health. At the patient level, digital health solutions can be used to promote healthy behaviours and enhance preventive care for women of reproductive age who are at risk of or living with non-communicable diseases. At the provider level, the application of digital health technologies can enhance the quality of integrated care—for instance, by using telemedicine for specialised care, through improved digital monitoring of patients, or remote training of health care providers. At the health system level, electronic health records simplify the planning, execution, and evaluation of interventions during pregnancy, while integration of digital health interventions into antenatal care saves lives and resources, especially in low and middle income countries. However, it is essential to reduce the digital divide between high income and low and middle income countries, as well as within the countries, to ensure digital health technologies do not exacerbate existing health inequalities.

Governments should establish conducive policy and regulatory environments and ensure sustainable financing to facilitate the use of digital health technologies, in particular through intersectoral collaboration and public-private partnerships. Efforts are required to improve end users’ digital health literacy and willingness to use digital health applications through training, ongoing support for technologies, and involvement in all stages of the digitalisation process. Finally, well constructed implementation research and evaluation studies are required to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of existing digital health interventions and identify best practices to inform policy development, implementation, and greater investments.

Key messages.

Digital health solutions have the potential to strengthen health systems and help achieve universal health coverage

The use of digital health technologies has been spreading rapidly, but it is essential to address the digital divide between high income and low and middle income countries, as well as within the countries

Scale-up of digital health interventions will require strong governance mechanisms, regulatory frameworks, sustainable financing, and engagement of end users, such as patients, communities, healthcare workers, and public health practitioners at all stages

Interdisciplinary implementation research will be crucial to guide the scale-up of digital health in low and middle income countries

Acknowledgments

Members of the expert contributors’ group: Mekhri Shoismatuloeva, Virginia Arnold, Alexey Kulikov, Garett Mehl, Natschja Ratanaprayul, Tigest Tamrat, Flaminia Ortenzi, Abigail Williams.

We thank the healthcare providers in Vietnam and Kyrgyzstan who participated in the initial assessment of the facility readiness for integration of non-communicable disease services into MNCH care in the context of the WHO project.

Contributors and sources: All authors have the experience and expertise in maternal and child health, NCDs, integrated care and the use of digital health technologies to improve the availability, accessibility, and quality of health services. TC and SA conceptualised the paper. TC wrote the first draft. AM and QN provided country examples. All authors contributed intellectual content, provided specific inputs on their areas of expertise, edited the manuscript, and approved the final submitted version.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of a series commissioned by The BMJ based on a proposal from the World Health Organization. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication. WHO paid the open access fees.

References

- 1.International Telecommunication Union and United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. The state of broadband. People-centred approaches for universal broadband. 2021. https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-s/opb/pol/S-POL-BROADBAND.23-2021-PDF-E.pdf

- 2. Manyazewal T, Woldeamanuel Y, Blumberg HM, Fekadu A, Marconi VC. The potential use of digital health technologies in the African context: a systematic review of evidence from Ethiopia. NPJ Digit Med 2021;4:125. 10.1038/s41746-021-00487-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. 71st World Health Assembly resolution on digital health. 2018. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA71/A71_ACONF1-en.pdf

- 4.World Health Organization. Global strategy on digital health 2020-2025. 2021. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/gs4dhdaa2a9f352b0445bafbc79ca799dce4d.pdf

- 5. World Health Organization . Digital implementation investment guide (DIIG): integrating digital interventions into health programmes. WHO, 2020.. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010567. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Global diffusion of eHealth: making universal health coverage achievable: report of the third global survey on eHealth. 2016. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511780

- 7.World Health Organization. Classification of digital health interventions v1.0: a shared language to describe the uses of digital technology for health. 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/260480

- 8.World Health Organization. Recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening. 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550505 [PubMed]

- 9.World Health Organization. mHealth: new horizons for health through mobile technologies. 2011. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44607

- 10.Deloitte Centre for Health Solutions. Digital transformation: shaping the future of European healthcare. 2020. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/life-sciences-health-care/deloitte-uk-shaping-the-future-of-european-healthcare.pdf

- 11. Jack BW, Bickmore T, Yinusa-Nyahkoon L, et al. Improving the health of young African American women in the preconception period using health information technology: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Digit Health 2020;2:e475-85. 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30189-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sung JH, Lee DY, Min KP, Park CY. Peripartum management of gestational diabetes using a digital health care service: a pilot, randomized controlled study. Clin Ther 2019;41:2426-34. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Dijk MR, Oostingh EC, Koster MP, Willemsen SP, Laven JS, Steegers-Theunissen RP. The use of the mHealth program smarter pregnancy in preconception care: rationale, study design and data collection of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:46. 10.1186/s12884-017-1228-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2022;183:109119. 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Preconception care: report of a regional expert group consultation. New Delhi, 2014. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/205637/B5124.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- 16. Citrin D, Thapa P, Nirola I, et al. Developing and deploying a community healthcare worker-driven, digitally- enabled integrated care system for municipalities in rural Nepal. Healthc (Amst) 2018;6:197-204. 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Faujdar DS, Sahay S, Singh T, Kaur M, Kumar R. Field testing of a digital health information system for primary health care: A quasi-experimental study from India. Int J Med Inform 2020;141:104235. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shidhaye R, Madhivanan P, Shidhaye P, Krupp K. An integrated approach to improve maternal mental health and well-being during the covid-19 crisis. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:598746. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.598746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hussain-Shamsy N, Shah A, Vigod SN, Zaheer J, Seto E. Mobile health for perinatal depression and anxiety: scoping review. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e17011. 10.2196/17011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bogale B, Mørkrid K, O’Donnell B, et al. Development of a targeted client communication intervention to women using an electronic maternal and child health registry: a qualitative study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2020;20:1. 10.1186/s12911-019-1002-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jo Y, LeFevre AE, Ali H, et al. mCARE, a digital health intervention package on pregnancy surveillance and care-seeking reminders from 2018 to 2027 in Bangladesh: a model-based cost-effectiveness analysis. BMJ Open 2021;11:e042553. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tian M, Zhang X, Zhang J. mHealth as a health system strengthening tool in China. Int J Nurs Sci 2020;7(suppl 1):S19-22. 10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broadband Commission. The promise of digital health. Addressing non-communicable diseases to accelerate universal health coverage in LMICs. 2018. https://www.novartisfoundation.org/sites/novartisfoundation_org/files/2020-11/2018-the-promise-of-digital-health-full-report.pdf

- 24. Monaco A, Casteig Blanco A, Cobain M, et al. The role of collaborative, multistakeholder partnerships in reshaping the health management of patients with noncommunicable diseases during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging Clin Exp Res 2021;33:2899-907. 10.1007/s40520-021-01922-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Bank. Overview: the World Bank in Vietnam. 2022. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam/overview#1

- 26.KPMG. Future of digital health in Vietnam. 2022. https://home.kpmg/vn/en/home/insights/2021/01/future-of-digital-health-in-vietnam.html

- 27.Ministry of Health Viet Nam, Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health, WHO, World Bank and Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research. Success factors for women’s and children’s health. 2014. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/178633

- 28.World Bank. Overview: the Kyrgyz Republic. 2021. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/kyrgyzrepublic/overview#1

- 29.World Health Organization European Office for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Disease. Prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases in Kyrgyzstan: the case for investment. 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/351407

- 30. Krah EF, de Kruijf JG. Exploring the ambivalent evidence base of mobile health (mHealth): a systematic literature review on the use of mobile phones for the improvement of community health in Africa. Digit Health 2016;2:2055207616679264. 10.1177/2055207616679264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gallardo-Rincón H, Montoya A, Saucedo-Martínez R, et al. Integrated Measurement for Early Detection (MIDO) as a digital strategy for timely assessment of non-communicable disease profiles and factors associated with unawareness and control: a retrospective observational study in primary healthcare facilities in Mexico. BMJ Open 2021;11:e049836. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zaidi S, Kazi AM, Riaz A, et al. Operability, usefulness, and task-technology fit of an mHealth app for delivering primary health care services by community health workers in underserved areas of Pakistan and Afghanistan: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e18414. 10.2196/18414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McCool J, Dobson R, Muinga N, et al. Factors influencing the sustainability of digital health interventions in low-resource settings: lessons from five countries. J Glob Health 2020;10:1-9. 10.7189/jogh.10.020396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ruton H, Musabyimana A, Gaju E, et al. The impact of an mHealth monitoring system on health care utilization by mothers and children: an evaluation using routine health information in Rwanda. Health Policy Plan 2018;33:920-7. 10.1093/heapol/czy066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Steinman L, van Pelt M, Hen H, et al. Can mHealth and eHealth improve management of diabetes and hypertension in a hard-to-reach population? -lessons learned from a process evaluation of digital health to support a peer educator model in Cambodia using the RE-AIM framework. Mhealth 2020;6:40. 10.21037/mhealth-19-249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goto R, Watanabe Y, Yamazaki A, et al. Can digital health technologies exacerbate the health gap? A clustering analysis of mothers’ opinions toward digitizing the maternal and child health handbook. SSM Popul Health 2021;16:100935. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McBride B, O’Neil JD, Hue TT, Eni R, Nguyen CV, Nguyen LT. Improving health equity for ethnic minority women in Thai Nguyen, Vietnam: qualitative results from an mHealth intervention targeting maternal and infant health service access. J Public Health (Oxf) 2018;40(suppl_2):ii32-41. 10.1093/pubmed/fdy165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Labrique AB, Wadhwani C, Williams KA, et al. Best practices in scaling digital health in low and middle income countries. Global Health 2018;14:103. 10.1186/s12992-018-0424-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gyselaers W, Lanssens D, Perry H, Khalil A. Mobile health applications for prenatal assessment and monitoring. Curr Pharm Des 2019;25:615-23. 10.2174/1381612825666190320140659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kruse C, Betancourt J, Ortiz S, Valdes Luna SM, Bamrah IK, Segovia N. Barriers to the use of mobile health in improving health outcomes in developing countries: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e13263. 10.2196/13263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hossain MM, Tasnim S, Sharma R, et al. Digital interventions for people living with non-communicable diseases in India: A systematic review of intervention studies and recommendations for future research and development. Digit Health 2019;5. 10.1177/2055207619896153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bakibinga P, Kamande E, Kisia L, Omuya M, Matanda DJ, Kyobutungi C. Challenges and prospects for implementation of community health volunteers’ digital health solutions in Kenya: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:888. 10.1186/s12913-020-05711-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Barron P, Peter J, LeFevre AE, et al. Mobile health messaging service and helpdesk for South African mothers (MomConnect): history, successes and challenges. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3(suppl 2):e000559. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nwolise CH, Carey N, Shawe J. Exploring the acceptability and feasibility of a preconception and diabetes information app for women with pregestational diabetes: a mixed-methods study protocol. Digit Health 2017;3. 10.1177/2055207617726418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Patel SA, Sharma H, Mohan S, et al. The integrated tracking, referral, and electronic decision support, and care coordination (I-TREC) program: scalable strategies for the management of hypertension and diabetes within the government healthcare system of India. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:1022. 10.1186/s12913-020-05851-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Patil S, Patil N, Joglekar C, et al. Adolescent and preconception health perspective of adult non-communicable diseases (DERVAN): protocol for rural prospective adolescent girls cohort study in Ratnagiri district of Konkan region of India (DERVAN-1). BMJ Open 2020;10:e035926. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Crimmins SD, Ginn-Meadow A, Jessel RH, Rosen JA. Leveraging technology to improve diabetes care in pregnancy. Clin Diabetes 2020;38:486-94. 10.2337/cd20-0047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]