Abstract

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) drive metastasis, the leading cause of death in individuals with breast cancer. Due to their low abundance in the circulation, robust CTC expansion protocols are urgently needed to effectively study disease progression and therapy responses. Here we present the establishment of long-term CTC-derived organoids from female individuals with metastatic breast cancer. Multiomics analysis of CTC-derived organoids along with preclinical modeling with xenografts identified neuregulin 1 (NRG1)–ERBB2 receptor tyrosine kinase 3 (ERBB3/HER3) signaling as a key pathway required for CTC survival, growth and dissemination. Genome-wide CRISPR activation screens revealed that fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) signaling serves a compensatory function to the NRG1–HER3 axis and rescues NRG1 deficiency in CTCs. Conversely, NRG1–HER3 activation induced resistance to FGFR1 inhibition, whereas combinatorial blockade impaired CTC growth. The dynamic interplay between NRG1–HER3 and FGFR1 signaling reveals the molecular basis of cancer cell plasticity and clinically relevant strategies to target it. Our CTC organoid platform enables the identification and validation of patient-specific vulnerabilities and represents an innovative tool for precision medicine.

Subject terms: Breast cancer, Mechanisms of disease, Cancer models, Cancer

Trumpp and colleagues develop a method to obtain long-term circulating tumor cell-derived organoids from individuals with metastatic breast cancer and identify the neuregulin 1–HER3 axis as important for organoid growth and a promising therapeutic target.

Main

Breast cancer (BC) treatment and prognosis have been greatly improved in recent years. Nevertheless, metastatic BC (MBC) remains incurable. BC cells spread mainly to the lungs, liver, bones, lymph nodes and brain, and the source of these metastases has been suggested to be circulating tumor cells (CTCs) with metastasis-initiating ability1. Even though CTC enumeration serves as a prognostic marker2,3, CTC biology remains poorly understood4. Notably, the field still lacks a standardized method for the functional characterization of CTCs, which is essential to unveil the mechanisms and pathways involved in tumor spreading, dissemination and colonization to distant organs. The scarcity of CTCs in blood and the difficulty of culturing them limit their use for functional analyses. Limited publications have reported the possibility of expanding CTCs from few patients with MBC (MBCPs) with extremely high CTC numbers5–7. Nonetheless, a systematic and detailed assessment of the in vitro conditions required to generate long-term propagatable CTCs is lacking8. Liquid biopsies are easy to obtain and almost noninvasive, and they provide a continuous source of tumor-derived material (CTCs or circulating cell-free tumor DNA), granting the possibility of longitudinal sampling. The establishment of experimental platforms supporting reliable isolation and expansion of CTCs is therefore of great interest due to relevant clinical implications9, including the identification of adaptive resistance mechanisms and CTC plasticity in response to environmental challenges10,11.

A recent study suggested that CTC lifespan is the most critical parameter governing metastasis12. Hence, identification of the pathways responsible for CTC survival represents a crucial step for blocking CTC dissemination. The treatment algorithms for MBC are mainly decided based on estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor and ERBB2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ERBB2/HER2) expression, assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of the primary tumor. To date, HER2 inhibitors, such as trastuzumab, pertuzumab, tucatinib, lapatinib and HER2-directed antibody–drug conjugates (such as trastuzumab deruxtecan), are the standard approaches exclusively for BC with HER2 amplification even though HER2-expressing cells also exist in HER2–/HER2lo BCs13,14. Indeed, a recent landmark study demonstrated that treatment with trastuzumab deruxtecan significantly prolonged progression-free survival in individuals with HER2lo BC15, highlighting the relevance of the HER2 pathway in MBC irrespective of the HER2 IHC score determined at diagnosis. HER2 activates downstream oncogenic signaling via the PI3K–AKT, MAPK and JAK–STAT pathways, mainly by dimerizing with its partner HER3 (ref. 16), which contains the binding pocket for the ligand neuregulin 1 (NRG1). Although the NRG1–HER3 pathway has been studied in BC17 and other entities18, only limited information is available on its role in MBC CTCs.

Here, we established a method for the long-term expansion of MBCP-derived CTCs from multiple liquid biopsy sources. Using this platform, we identified NRG1 as a key factor that promotes HER3+ CTC survival, facilitating metastatic growth. Moreover, we uncovered FGFR1 signaling as a compensatory mechanism able to sustain CTC survival and growth in the absence of NRG1. Last, we provide functional data showing that combinatorial blockade of NRG1 and FGFR1 signaling could efficiently target CTCs in MBCPs.

Results

Role of NRG1 in metastasis and CTC-derived organoid establishment

In the initial attempt to establish in vitro conditions for MBCP-derived CTCs, we pre-expanded cells in vivo, generating xenografts where CTCs (CTC-derived xenograft (CDX))1 or cells collected from effusions (effusion-derived xenograft (EDX))19 were transplanted into immunocompromised NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice. We then isolated tumor cells from the xenografts and expanded them in a serum-free molecularly defined medium containing different supplements that support the organotypic growth of primary cells (first-generation G1 medium). CTC-derived organoids (CDOs) were expanded as three-dimensional structures, either in a matrix-free condition or embedded in a collagen-based chemically defined floating matrix20. Using this strategy, we successfully established and expanded a total of six different CDX or EDX models for more than 20 passages while preserving their genetic profile (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). Only in one out of six models did cells acquire an additional mutation in SMAD4 at passage 14, with concomitant change in their morphology (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Importantly, the CDOs faithfully recapitulated the original individual and matched xenograft subtypes (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Thus, we were able to establish human BC CDOs from CDXs and EDXs while maintaining patient-specific characteristics.

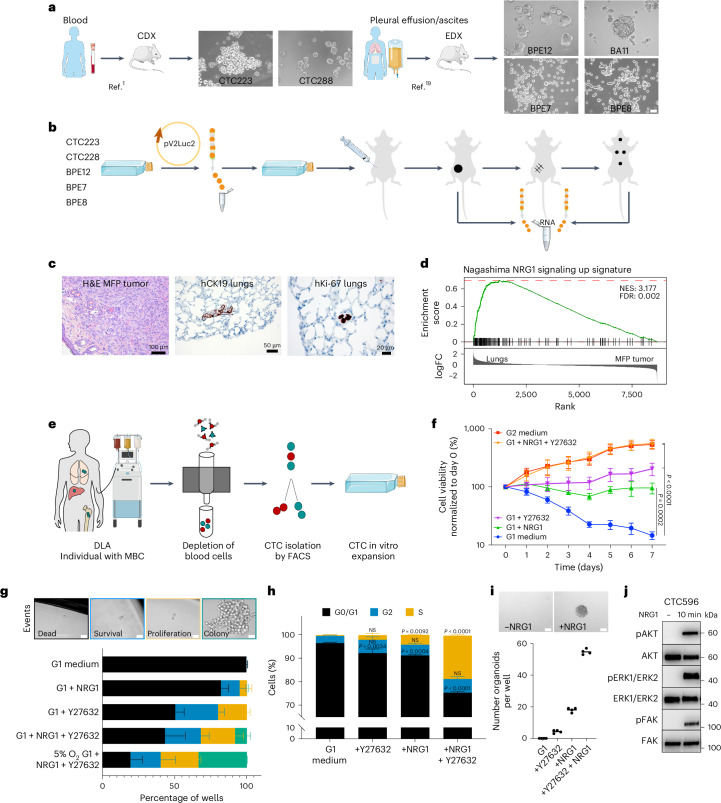

Fig. 1. NRG1 signaling is upregulated in metastasis-initiating cells in vivo and is crucial to establish primary CDOs.

a, CDX and EDX in vitro models. Scale bar, 20 µm. BPE, pleural effusion from a patient with breast cancer; BA peritoneal effusion from a patient with breast cancer b, In vivo preclinical model of spontaneous metastatic formation. c, Representative IHC images of mammary fat pad (MFP) tumor (hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)) and matched lung-colonizing cells detected using human-specific antibodies to CK19 and Ki-67; experiments were repeated three times independently with similar results. d, Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) applying the ‘Nagashima NRG1 signaling up’ signature21 to the dataset of sorted lung-colonizing cells (Lungs) and matched primary tumor cells (MFP tumor); NES, normalized enrichment score; FDR, false discovery rate; FC, fold change. e, CTC isolation and in vitro direct expansion workflow. f, CTC596 cell growth under different medium conditions using the CellTiter Blue (CTB) assay. Mean values were normalized to day 0 for each condition and log10 transformed to enhance approximate normality. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.; n = 3 biological replicates for G1 + Y27632 and G1 + NRG1 + Y27632; n = 4 biological replicates for G1, G1 + NRG1 and G2. Data were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance with a Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test; G1 + NRG1, P = 0.0002; G1 + Y27632, G1 + NRG1 + Y27632 and G2, P < 0.0001, each versus G1 medium at day 7. g, Top: clonogenic assay representative brightfield images. Scale bar, 10 μm. Bottom: stacked bar plot showing the percentages of colonies (green), proliferating cells (orange), surviving cells (blue) and dead cells (black). Data are shown as mean ± s.d.; n = 2 biological replicates for 5% O2 G1 + NRG1 + Y27632, G1 + NRG1 + Y27632; n = 3 biological replicates for G1 + Y27632, G1 + NRG1 and G1. h, Cell cycle phase distribution (S (orange), G2 (blue) and G0/G1 (black)) after 48 h under different medium conditions. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.; n = 3 biological replicates. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA test with a Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test versus G1; NS, not significant; G0/G1: +Y27632, P = 0.0034; +NRG1, P = 0.0004; +NRG1 + Y27632, P < 0.0001. S: +NRG1, P = 0.0092; +NRG1 + Y27632, P < 0.0001. i, Top: representative brightfield images of CTC596 organoids without (left) or with (right) NRG1 (20 ng ml–1). Scale bars, 100 μm. Bottom: organoid quantification. Bars represent the mean, and each dot represents a technical replicate (n = 4). j, Representative western blot showing phosphorylated and total levels of AKT, ERK1/ERK2 and FAK, with or without NRG1 (20 ng ml–1, 10 min). Experiments were repeated two times independently with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 1. Characterization of CDX and EDX-derived organoids.

a. Oncoprint showing the molecular alterations including the most frequent mutated genes in breast cancer. Targeted-DNA panel sequencing has been performed on longitudinal CDX and EDX-derived CDOs and from the xenograft they have been generated (labelled as ‘xeno’). Different in vitro passages of xenograft-derived CDOs are labelled with p and the number. Pink: possibly amplified; Red: amplified; Light green: possibly deleted, Green: deleted; Mustard: mutation; Azure/Red: partial gene duplication; Azure/Green: partial gene deletion. b. Representative IHC pictures of different CDX- and EDX-derived CDOs, repeated two times independently with similar results. Scale bar 50 µm.

To avoid the time-consuming patient-derived xenograft (PDX) pre-expansion step and thus be able to analyze tumor cells in the laboratory in parallel to the clinical course of disease, we tested the efficacy of the G1 medium in supporting the expansion of CTCs directly isolated from MBCP liquid biopsies. G1 was not sufficient to promote cell proliferation nor to maintain cell survival of CTCs in vitro. Therefore, to optimize culture conditions for primary CDOs, we performed transcriptomic analysis on primary and metastatic cells from preclinical xenografts with the aim of identifying the molecular pathways critical for CTC growth in vivo (Fig. 1b). To study the early stages of cell spreading and distant organ colonization after primary tumor removal, we analyzed the micrometastatic stage whereby only small clusters of cells were present (Fig. 1c). As expected, interparticipant heterogeneity was larger than the intraparticipant differences between primary and metastatic cells (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Within each individual, primary tumors clustered separately from metastatic cells, suggesting substantial transcriptional differences already at the micrometastatic stage. As all the models consistently gave rise to lung metastases while other organs were differentially colonized, we focused on lung-metastatic cells. Here, we found an NRG1-dependent signature21 that was strongly enriched in lung-colonizing cells compared to in the primary tumor (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 2b). Based on these results, we supplemented the G1 medium with NRG1 (20 ng ml–1) along with other factors that are beneficial for ex vivo carcinoma cultures, namely FGF3, FGF7, FGF8, FGF9, FGF10, noggin, gremlin-1, SB431542 (activin–BMP–TGFβ pathway inhibitor) and Y27632 (ROCK inhibitor)22,23. To test this now-termed G2 formula, we established a protocol to isolate CTCs directly from MBCP blood by diagnostic leukapheresis (DLA; CTC596). The DLA product was processed by depletion of hematopoietic and endothelial cells, followed by enrichment of EPCAM+CD45− CTCs by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS; Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 1). Both our G1 medium and previously reported CTC medium7 were not sufficient to promote cell proliferation nor to maintain CTC survival. By contrast, G2 medium allowed the exponential growth of CDOs over time, with a significant reduction of apoptotic and necrotic cells compared to CDOs in the original G1 medium (Fig. 1f,g and Extended Data Fig. 3a,b).

Extended Data Fig. 2. Neuregulin 1 signaling is up-regulated in metastasis-initiating cells in vivo.

a. Heatmap showing the expression levels of the top 1000 most differentially expressed genes. Within each patient, transcriptional profiles clustered based on the sample source: primary tumor ´MFP tumor´ or different metastatic sites: lungs, adrenal gland, brain, liver, spleen. b. Top ten signatures enriched in metastatic cells, using as dataset the sorted lung-colonizing cells (Lungs) and matched cells from the primary tumor (MFP Tumor), ranked according to the -log10 p value (one side) after gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) with gage R package using the C2 curated gene sets from MSigDB.

Extended Data Fig. 3. CTC medium and NRG1 in plasma.

a. Stacked bar plots showing the percentages of growing colonies (green), proliferating cells (orange), surviving cells (blue) and dead cells (black) in a clonogenic assay. Different media conditions are used (see Material and Methods for more details on media composition). Counting was performed 30 days after single CTC596 cells FACS sorting. Data are shown as mean ± s.d., n = 2 5%O2 G1 + NRG1 + Y27632, G1 + NRG1 + Y27632, G1 + R-spondin, G1+Noggin (NOG), Gremlin-1 (GREM), G1 + SB431542, G1+FGFs, 5%O2 Published medium, Published medium, n = 3 5%O2 G2, G2, G1 + Y27632, G1 + NRG1, G1 biological replicates. b. Stacked bar plots showing live or dead CTC596 cell distribution (healthy (green), early apoptotic (orange), late apoptotic (blue), and necrotic (black)) after 48 (left) and 120 (right) hours in either G1, G2, G2 w/o NRG1, G2 w/o Y27632, or G2 w/o both Y27632 and NRG1 medium. Cell state analysis was determined via flow cytometry after Annexin and Phosphoinositol (PI) staining. Data are mean ± s.e.m, n = 3 biological replicates. two-way ANOVA test, Dunnett´s multiple comparisons test, statistical analysis is reported in Source Data. c. Plot showing NRG1 concentration (pg/ml) in blood samples of metastatic breast cancer patients (MBCPs, n = 7) measured with the Human NRG1 ELISA kit. d. Western blot analysis of whole-cell protein lysate derived from CTC596 cells in absence or presence of NRG1 at different concentrations (0.1, 0.5, 0.8 and 20 ng/ml), including the average NRG1 concentration in the blood of MBC patients (0.8 ng/ml). Phosphorylated and total HER3 and Protein Kinase B (Akt) were detected, tubulin was used as the loading control, n = 1.

To identify the essential supplements required and sufficient for the robust proliferative effect of G2 medium, each molecule/growth factor was tested separately by either the addition to G1 medium or removal from G2 medium, respectively. Remarkably, although none of the single growth factors tested was able to completely recapitulate the effects observed using G2, NRG1 and Y27632 promoted survival and proliferation when added individually to the G1 medium (Fig. 1h,i). Strikingly, by adding both NRG1 and Y27632, a synergistic effect on CDO growth was observed, and the addition of both compounds fully phenocopied the growth mediated by G2 (Fig. 1f–h and Methods). We therefore defined ‘CTC medium’ as G1 + NRG1 + Y27632. Interestingly, we observed that low oxygen (5%) enhanced cell viability and colony formation (Fig. 1g), similar to what was observed for induced pluripotent stem cells24. Finally, we confirmed that NRG1 treatment triggered downstream signaling pathways, including AKT, MAPK and FAK (Fig. 1j).

These data suggest that CTC survival in blood may be supported by the presence of NRG1 in the bloodstream. We therefore measured NRG1 levels in plasma from MBCP blood samples (n = 7) and detected an average concentration of 815.14 pg ml–1 (range of 479–1,107 pg ml–1; Extended Data Fig. 3c). These NRG1 levels are likely sufficient to activate the downstream signaling pathways because as low as 100 pg ml–1 was sufficient to phosphorylate and activate HER3 and AKT in CTC596 cells (Extended Data Fig. 3d).

Together, our data demonstrate that NRG1 signaling plays a key role in the establishment and growth of primary CTCs in vitro.

Long-term CDOs from individuals with MBC

After successful generation of the first long-term CDO, we established additional CDOs from different MBC liquid biopsy sources. To select samples with higher CTC numbers, we enumerated relatively intact CTCs in blood using the Food and Drug Administration-approved CellSearch system in a cohort of 567 MBCPs treated at the National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT) in Heidelberg from January 2017 to April 2022 (Fig. 2a). In 263 (46.38%) samples, CTCs were not detected, 165 (29.10%) individuals showed between 1 and 9 CTCs, 110 (19.40%) individuals showed between 10 and 100 CTCs, and 28 individuals (4.94%) showed more than 100 CTCs (Fig. 2b). Survival correlated with the number of CTCs, with a median survival of 1,129 days in individuals where CTCs were not detectable, 492 days in individuals with CTC counts between 1 and 9, 267 days in individuals with CTC counts between 10 and 100 and 254.5 days in individuals with more than 100 CTCs (Fig. 2c). Next, we collected additional liquid biopsies from individuals with the highest (>100) CTC counts for CDO generation. From 8 of 12 samples (66.7%) available, we successfully generated long-term CDOs: three from DLA and five from peripheral blood (Extended Data Fig. 4a). In addition, we established CDOs from effusions from two individuals, one of which contained no CTCs in the blood. The models included all major subtypes of BC: hormone receptor+HER2– (HR+HER2–; luminal), HR–HER2– (triple negative BC (TNBC)) and HER2+ (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 1). The absence of cross-contamination with cell lines and the match between CDOs and the corresponding participant were confirmed (Extended Data Fig. 4b,c). CDOs were profiled for genetic alterations using participant-matched biopsies of tumor lesions as references and matched buffy coats as germline controls25. As expected, TP53 and PIK3CA were the most frequently mutated genes, followed by APC and CDH1 (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Table 2). Moreover, copy number analysis highlighted a strong consistency between the genomic profiles of CDOs and matched participant profiles (Extended Data Fig. 4d). Of note, a gain of chromosome 1q (chr1q; CTC1119 and CTC1063) or loss of chr16q (CTC1296, CTC775 and CTC1106) was observed in the matched CDOs and participant samples, in line with what was previously reported for HR+ BCs. In TNBC-derived CTC1273 and CTC1007 cells, a typical gain of chr10p was detected in both CDOs and matched participant samples26. All models were also subjected to transcriptomic analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA) showed that transcriptomes clustered primarily by participant ID, as expected. Nonetheless, the BC subtype was the main driver of PC1 separation because TNBC-derived CDOs clustered separately from either HER2+ or luminal-derived CDOs (Fig. 2f). CDO heterogeneity was highlighted by varying levels of EpCAM, vimentin, Ki-67 and ER expression (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 5a). Next, we demonstrated that the CDOs can be used as a clinically relevant platform to model drug sensitivity or resistance. Indeed, sensitivity to the selective PIK3CA inhibitors alpelisib or taselisib27,28 correlated with PIK3CA status (Fig. 2h and Extended Data Fig. 5b). We then collected a second liquid biopsy from participant CTC1106 (Fig. 2i) who, after an initial response, developed resistance to alpelisib/fulvestrant as assessed by computed tomography scans, tumor markers and reduced general condition. The second established CDO from CTC1106 at time point t2 showed lower sensitivity to either alpelisib or taselisib than t1 CDOs (Fig. 2j and Extended Data Fig. 5c), recapitulating the clinical resistance status of the participant at this stage.

Fig. 2. Systematic establishment and characterization of long-term CDOs directly from individuals with MBC.

a, MBCP cohort (n = 567). b, Distribution of participants according to CTC number per 7.5 ml of blood using the CellSearch system (Menarini). NA, not available. c, Probability of survival stratified by CTC count in MBCPs (n = 566 participants). Data were analyzed by log rank (Mantel–Cox) test, and the P value of each comparison is reported. d, Left: isolation of CTCs from peripheral blood or effusion products. Right: brightfield images of the CDOs are shown. Scale bar, 50 μm. e, Mutational profile of the top ten most commonly mutated genes in CDOs and matched participant lesions. f, PCA plot using RNA-seq data from CDOs. Different tumor subtypes are indicated with different shapes (HER2+, circle; luminal, triangle; TNBC, square). RNA-seq libraries were prepared in triplicates for each model. g, Representative IHC images for H&E, ER, EpCAM, vimentin and Ki-67 protein expression in CDOs from the CTC1063 luminal subtype and CTC1125 TNBC subtype; n = 1; scale bar, 50 µm. h, Area under the curve (AUC) values for dose–response to alpelisib. A CTB assay was performed after 72 h. Bars represent the median, and each dot represents the AUC mean derived from two independent experiments for each CDO. CDOs were grouped according to PIK3CA status: WT (left, n = 6) and mutated (mut; right, n = 4) CDOs. Data were analyzed by two-tailed unpaired t-test; P = 0.0097. i, CTC numbers in 7.5 ml of blood in longitudinal samples from participant CTC1106. An overview of the treatment regimen is reported; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response. Dates are shown along the x axis. j, Plot representing the dose–response of CTC1106 (blue, t1) and CTC1106 effusion (gray, t2) CDOs to alpelisib treatment. A CTB assay was performed after 72 h. The CTB fluorescence value was normalized to the viability of cells without the drug. Dots represent the mean; n = 2 biological replicates. The average half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values are reported.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Establishment and characterization of long-term CDOs.

a. Donut plot showing successful (Establishment) or unsuccessful (Failed) attempts to obtain long-term CDOs. b. Heatmap showing the logarithm of the odds (LOD) score calculated for pairwise comparisons of RNAseq data from our CDOs and publicly available cell lines (from both human breast and blood cancer). c. Heatmap showing the LOD score calculated for pairwise comparisons of WGS data from primary patient material (buffy coat and tumor lesions) and matched CDOs. d. logR plots showing copy number profiles of primary patient tumor lesions and CDOs. Matched buffy coats were used as germline controls.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Phenotyping and drug sensitivity of long-term CDOs.

a. Representative IHC pictures of different CDOs, n = 1. Scale bar 50 µm. b. Plot showing area under the curve (AUC) values for dose-response to Taselisib. Cells were grouped according to PIK3CA status (wild-type (wt) on the left, n = 6, mutated (mut) on the right, n = 4). CTB assay was performed after 72 hours. Each dot represents the AUC mean obtained from n = 5 CTC1106, n = 3 CTC1063, CTC1007, CTC1125, n = 2 CTC1119, CTC782, CTC775, CTC596, CTC1273, CTC1296 biological replicates. Two-tailed Unpaired t test: p = 0.0136. c. Plot representing the dose response of CTC1106 CDO T1 (blue) and CTC1106 CDO T2 (grey) to Taselisib. CTB assay was performed after 72 h. The CTB fluorescence value was normalized to the viability of cells without the drug. Bars represent the mean, error bars indicate standard error of the mean, n = 5 T1, n = 3 T2 biological replicates. The average IC50 values are reported (µM). d. Boxplots showing EGFR, ERBB2, ERBB4 expression using RNAseq normalized counts from CDOs, n = 3 biological replicates. Boxplots show low and upper quartiles and median line is indicated. Whiskers, 1.5 × interquartile range. Dashed line represents the median expression. RNAseq libraries have been prepared in triplicates for each of the CTC models.

Together, we generated 11 primary CDOs from liquid biopsies of 10 MBCPs. These CDOs serve as a platform for studying how cancer cells become resistant to therapy over time.

HER3 is crucial for CTC growth and survival in vivo

Given the critical role of NRG1 in maintaining CDO survival and proliferation, we next investigated the expression of ERBB family member receptors (EGFR and HER2–HER4) relevant to mediating NRG1 intracellular signaling. Among these, HER3, capable of directly binding NRG1 and preferred dimerization partner of HER2 (ref. 16), showed the highest and most consistent, albeit heterogeneous, expression across the different models (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 5d). HER3 protein expression was detected in CDOs of all subtypes, matched xenograft tumors (CDX) and matched participant primary tumors and metastases (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 6a).

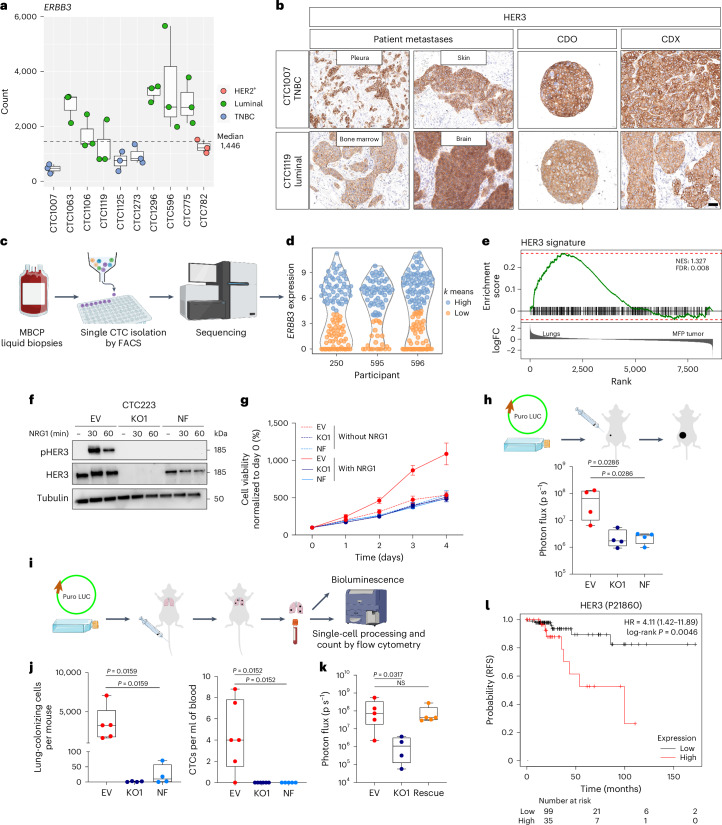

Fig. 3. HER3 expression is crucial for CTC growth and survival in vivo.

a, ERBB3 expression; n = 3 biological replicates. Box plots show the median and top and bottom quartiles. Whiskers denote 1.5× the interquartile range. b, Representative IHC images of HER3; n = 1; scale bar, 50 µm. c, scRNA-seq workflow. d, ERBB3 expression in CD45–EpCAM+ CTCs. ERBB3hi, turquoise; ERBB3lo, orange. e, GSEA using the HER3 CTC signature on the dataset from Fig. 1b. f, Western blot showing phosphorylated and total levels of HER3 with or without NRG1 (20 ng ml–1; 30 and 60 min) in ERBB3-WT or ERBB3-KO CTC223 cells; n = 1. g, CTB assay with (solid line) or without (dotted line) NRG1. Mean values were normalized to day 0 for each condition. Error bars indicate s.e.m.; n = 4 biological replicates for all conditions but EV without NRG1 day 4 and EV with NRG1 days 2, 3 and 4 (n = 3 biological replicates). Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. h, Top: in vivo tumorigenic assay workflow. Puro, puromycin resistance; LUC, luciferase. Bottom: tumor growth quantification via bioluminescence. Each dot represents a mouse; n = 4 per condition. Box plots show the median and top and bottom quartiles, and whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values. Data were analyzed by two-tailed Mann–Whitney test; KO1 versus EV, P = 0.0286; NF versus EV, P = 0.0286. i, In vivo metastasis assay workflow. j, Box plot showing tumor cell number per mouse (left, EV, n = 5 mice; KO1 and NF: n = 4 mice) and CTC number per ml of blood (right, EV and KO1, n = 6 mice; NF, n = 5 mice). Each dot represents a mouse. Box plots show median values and top and bottom quartiles, and whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values. Data were analyzed by two-tailed Mann–Whitney test (left, KO1 versus EV, P = 0.0159; NF versus EV, P = 0.0159; right, KO1 versus EV, P = 0.0152; NF versus EV, P = 0.0152). k, Box plot showing ex vivo lung bioluminescence intensity. Each dot represents a mouse. Box plots show median values and top and bottom quartiles, and whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values (EV and NF, n = 5 mice; KO1, n = 4 mice). Data were analyzed by two-tailed Mann–Whitney test (KO1 versus EV, P = 0.0317; ERBB3 rescue versus EV, P = 0.8413). l, Relapse-free survival (RFS) in ER+ stage 3 BC according to HER3 protein expression interrogating TCGA RPPA cohort; low, black; high, red; HR, hazard ratio.

Extended Data Fig. 6. HER3 expression and scRNAseq of CTCs.

a. Representative IHC picture for HER3 protein expression in patient primary tumor and metastatic lesions (left), in vitro CTCs Derived Organoids (CDO) (middle) and xenograft (CDX) (right), n = 1. Scale bar, 50 μm b. UMAP plot from scRNAseq analysis. Each dot represents one putative CTC, the color gradient is based on the origin (patient) of the cells. c. UMAP plot from scRNAseq analysis. Each dot represents one putative CTC, the color gradient is based on the expression of the indicated gene. d. Violin plot representing mean z-scores per cell for ERBB3high and ERBB3low cell populations. Z-score was computed for each signature gene and the mean of all z-scores was calculated for each cell. Two side t-test. e. Scatter plot of mean z-score over HER3-signature genes against mean z-score over NRG1-signature genes (Nagashima21). Each point represents a cell colored according to the patient of origin. Coefficient of determination (R2) and p-value result from Pearson´s correlation between the NRG1 mean z-scores and the HER3 mean z-scores is reported.

Single-cell transcriptomic analysis revealed heterogeneous expression of ERBB3 in three primary uncultured participant CTCs (Fig. 3c,d, Extended Data Fig. 6b,c and Supplementary Table 1). Analysis of differentially expressed genes in ERBB3hi compared to ERBB3lo clusters yielded 598 differentially regulated genes (Supplementary Table 3) that we used to generate a HER3 gene signature. This signature separated ERBB3hi from ERBB3lo CTCs within each participant (Extended Data Fig. 6d) and was highly enriched in lung-metastatic cells compared to primary tumor cells in the xenografts (Fig. 3e), indicating that HER3sign_high cells may mediate lung metastasis formation. Importantly, our CTC HER3 signature strongly correlates (R = 0.82, P < 2.2 × 10–16) with a reported functional NRG1 signature (‘Nagashima NRG1 signaling up’21), which was obtained after short-term treatment of MCF7 cell lines with NRG1 (Extended Data Fig. 6e). This is consistent with the functional expression of HER3 and activity of its downstream signaling cascade in CTCs of MBCPs.

To functionally dissect the role of HER3, we used CTC223 CDOs, which were established and maintained in G1 medium lacking NRG1 and thus developed independently of exogenous NRG1. We engineered CTC223 cells with an ERBB3-knockout (KO) allele or introduced an insertion–deletion-carrying non-functional (NF) allele defective for plasma membrane expression (Extended Data Fig. 7a). As expected, both ERBB3-KO cells and ERBB3-NF cells completely lacked NRG1-mediated HER3 phosphorylation (Fig. 3f). All edited CDOs showed similar growth kinetics in the absence of NRG1; however, only cells carrying wild-type (WT) ERBB3 (empty vector (EV)) responded to NRG1 treatment with increased growth, whereas the two mutant CDOs were refractory (Fig. 3g).

Extended Data Fig. 7. HER3 functional role in vivo.

a. Histogram showing representative flow-cytometry analysis for HER3 expression at the plasma membrane in CTC223 cells transduced with empty vector (EV, red) or two different gRNAs (KO in blue and NF in turquoise), n = 1. Experiments were repeated at least three times independently with similar results. b. Boxplot showing the quantification of luminescence signal from transplanted cells (CTC223 cells (EV (red), ERBB3 KO (blue), and NF (turquoise)) in the mammary fat pad (MFP) of female NSG mice at the day of injection. Each dot represents a mouse, boxs show low and upper quartiles and median line is indicated, whiskers indicate minimum and maximum value, n = 4 mice. Two-tailed Mann Whitney test, ns: not significant vs EV. c. Boxplot showing tumor weight in grams at end point. Each dot represents a tumor, n = 4 per condition, boxes show low and upper quartiles and median line is indicated, whiskers indicate minimum and maximum value. Two-tailed Unpaired t test, KO1 vs EV: p = 0.0286, NF vs EV: p = 0.0009. d. Representative flow-cytometry plots of lung-colonizing cells at end point. Tumor cells are defined as Blood Lineage− and EpCAM+. HER3 expression was checked. e. Boxplot showing lung bioluminescence intensity at the day (day 0) of the intravenous (tail vein) injection of CTC223 cells. Each dot represents a mouse, boxs show low and upper quartiles and median line is indicated, whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values, n = 6 mice. Two-tailed Mann Whitney test, ns: not significant vs EV. f. Boxplot showing ex vivo lung bioluminescence intensity at end point from intravenous injection of CTC223 cells. Each dot represents a mouse, boxs show low and upper quartiles and median line is indicated, whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values, EV, KO1: n = 6, NF: n = 5 mice. Two-tailed Mann Whitney test, KO1 vs EV: p = 0.0022, NF vs EV: p = 0.0043. g. Image of ex vivo lung bioluminescence from Fig. 3i,j and Extended Data Fig. 7f. h. Plot representing the blood volume used to detected CTCs at the end point of the metastatic assay. Each dot represents one mouse, mean ± s.d. id indicated, EV, KO1: n = 6, NF: n = 5 mice. One-way ANOVA, Tukey´s multiple comparisons test, the p value of each comparison is reported.

We next tested whether blocking HER3–NRG1 signaling could affect tumor growth in vivo by transplanting CDOs into the mammary fat pad of NSG mice. ERBB3-KO- and ERBB3-NF-cell-derived tumors were significantly smaller than ERBB3-EV controls (Fig. 3h and Extended Data Fig. 7b,c). To specifically evaluate the role of HER3 in mediating lung colonization independent of primary tumor growth, we performed tail vein injections of each of the three ERBB3 variant cell lines (Fig. 3i). After 5 months, thousands of ERBB3-EV cells (average of 3,430.6; range of 1,649–7,074) colonized the lungs, but none or only a few cells were detected in the ERBB3-KO (average of 1.25, range of 0–3) and ERBB3-NF groups (average of 22.75, range of 0–71; Fig. 3j, left, and Extended Data Fig. 7d). This was confirmed by bioluminescence quantification (Extended Data Fig. 7e–g). Consistently, we observed an average of 4.4 (range of 0–8.8) CTCs per ml of blood in ERBB3-EV transplant recipients, whereas no CTCs were detected in the circulation in the HER3-KO or HER3-NF cohorts (Fig. 3j, right, and Extended Data Fig. 7h). Importantly, the reintroduction of WT ERBB3 into ERBB3-KO cells (rescue) completely rescued the phenotype, confirming that HER3 is required and sufficient for lung colonization (Fig. 3k). Lastly, interrogation of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) reverse-phase protein array (RPPA) cohort29 revealed that HER3 is associated with poor outcome at the later stage of BC with respect to both relapse-free survival (P = 0.0046) and overall survival (P = 0.0074; Fig. 3l and Extended Data Fig. 8).

Extended Data Fig. 8. HER3 expression and breast cancer patient survival.

Kaplan-Meier curves indicating the overall survival (OS, left panels) and relapse free survival (RFS, right panels) according to HER3 protein expression (low in black and high in red) using the TCGA RPPA cohort filtered for ER positive breast cancer. First row in the plots all stages (1 + 2 + 3) are included, second row only stage 1 is included, third row only stage 2 is included, bottom plot only stage 3 is included.

Collectively, these data suggest a crucial role for NRG1–HER3 signaling in CTC dissemination and lung colonization, raising the possibility that high HER3 activity provides CTCs with propagating and lung metastasis-initiating capacity.

FGFR1 signaling circumvents HER3–NRG1 dependency in CDOs

Interestingly, although all established CDOs expressed high levels of HER3, they showed variable dependencies on NRG1 as measured by their clonogenic outgrowth efficiency in the presence or absence of NRG1. We identified an ‘NRG1-dependent’ group, which includes CTC596, CTC1106, CTC782, CTC775 and CTC1296, and an ‘NRG1-independent’ group, which includes CTC1063, CTC1119, CTC1007, CTC1125 and CTC1273 (Fig. 4a).

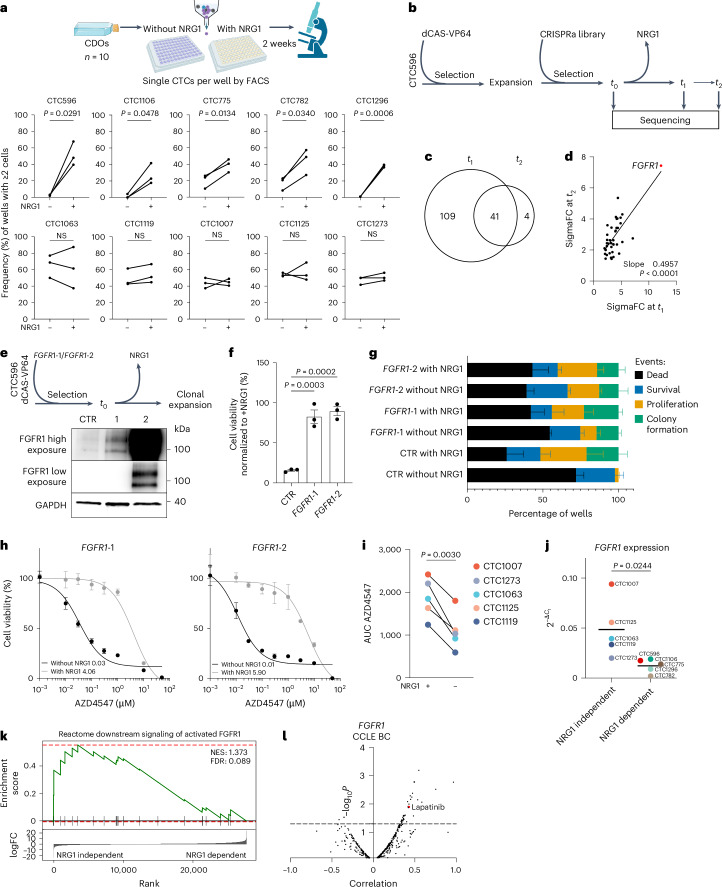

Fig. 4. FGFR1 signaling acts as a compensatory pathway and circumvents HER3–NRG1 dependency in CTCs.

a, Top: clonogenic assay workflow. Bottom: clonogenic assay quantification. Data were analyzed by two-tailed paired t-test (CTC596, P = 0.0291; CTC1106, P = 0.0478; CTC775, P = 0.0134; CTC782, P = 0.0340; CTC1296, P = 0.0006; CTC1063, P = 0.6965; CTC1119, P = 0.0848; CTC1007, P = 0.8611; CTC1125, P = 0.7429; CTC1273, P = 0.1869 with versus without NRG1; n = 3 biological replicates). b, CRISPR–dCas9 genome-wide activation screening workflow. c, Overlapping enriched genes in t1 and t2 compared to t0 (FDR < 0.05, number of gRNAs ≥ 2). d, Correlation plot between SigmaFC at t1 and t2 for overlapping genes (n = 41). A simple linear regression was calculated, and slope and P values are reported. e, Top: validation experiment workflow. Bottom: western blot analysis of CTC596 cells overexpressing FGFR1 (FGFR1-1 and FGFR1-2) and control (CTR, n = 1). f, Viability of CTC596 cells expressing dCas9 (CTR) or overexpressing FGFR1 (FGFR1-1 and FGFR1-2) without NRG1. Values were normalized to CTR cells with NRG1. Bars represent the mean, error bars indicate s.e.m., and each dot represents an experiment (n = 3 biological replicates). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with a Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (FGFR1-1 versus CTR, P = 0.0003; FGFR1-2 versus CTR, P = 0.0002). g, Clonogenic assay quantification (n = 3 biological replicates). Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. h, Dose–response of FGFR1-overexpressing cells treated with AZD4547 in the presence or absence of NRG1. Bars represent the mean, and error bars indicate s.e.m.; n = 3 biological replicates for all FGFR1-1 conditions but NRG1 0.001 µM (n = 2), and n = 3 for all FGFR1-2 conditions but NRG1 0.001 µM (n = 2) and NRG1 3 µM (n = 1). The average IC50 values are reported. i, AUC values for the NRG1-independent models in response to treatment with AZD4547 with (left) or without (right) NRG1. Each dot represents the AUC mean derived from two independent experiments. Data were analyzed by two-tailed paired t-test; P = 0.0030. j, FGFR1 expression in CDOs grouped according to NRG1 dependency. The bars represent the mean. Data were analyzed by two-tailed unpaired t-test; P = 0.0244. k, GSEA using the Reactome downstream signaling of activated FGFR1 signature as the dataset and RNA-seq data from NRG1-dependent and NRG1-independent CDOs as the gene set. l, Correlation plot between drug sensitivity and FGFR1 expression in BC cell lines.

To identify pathways that can compensate for NRG1–HER3 signaling at the functional level, we performed a genome-wide CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) screen using NRG1-dependent CTC596 CDOs (Fig. 4b). When NRG1 was withdrawn from the medium, we observed an initial massive cell death, followed by regrowth of NRG1-independent clones carrying specific single guide RNA (sgRNA), which we then collected at two different time points (t1 and t2). The screen identified 41 genes significantly enriched at both t1 and t2 compared to the initial time point (t0; Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table 4). The top enriched hit was FGFR1 (Fig. 4d), which is also genetically altered in 20% of MBCs30.

To validate these data, we overexpressed FGFR1 in CTC596 CDOs using a CRISPRa system with two different sgRNAs (1 and 2), resulting in either 5- or 400-fold FGFR1 overexpression (Fig. 4e and Extended Data Fig. 9a). Although cell viability of control cells was reduced to 15.6% 72 h after removal of NRG1, as expected, FGFR1 overexpression was sufficient to rescue this phenotype, achieving 82.66% and 89.48% (FGFR1 sgRNAs 1 and 2, respectively) of viable cells despite the absence of NRG1 (Fig. 4f). These results were further confirmed by clonogenic assays; although 71.88% of cells died and no colony formation was observed in control cells in the absence of NRG1, FGFR1-overexpressing CDOs (sgRNA 1 or sgRNA 2) showed a significantly lower percentage of dead cells (54.51% and 39.23%, respectively) and a higher proportion of proliferating and colony-forming cells in the absence of NRG1 (Fig. 4g). These data suggest that FGFR1 overexpression fully compensates for the absence of NRG1, leading to a complete rescue of cell viability and clonogenic growth potential.

Extended Data Fig. 9. FGFR1 expression and its correlation with HER3.

a. Bar plot representing the expression level of FGFR1 after overexpression in CTC596 using two independent guides (FGFR1#1, FGFR1#2). Data are shown as mean ± s.d., n = 2 biological replicates. b. Plots representing the dose response of CTC223 cells to AZD4547 in the presence (grey) or absence (black) of NRG1. CTB assay was performed after 72 h. The CTB fluorescence value was normalized to the viability of cells without the drug. Bars represent the mean, error bars indicate standard error of the mean, n = 3 biological replicates. The average IC50 values are reported (µM). c. Boxplot showing FGFR1 expression (normalized counts) from RNAseq data. Cells are grouped according to NRG1 dependency (CTC1106, CTC596, CTC1296, CTC782, CTC775 NRG1 dependent models on the left, CTC1007, CTC1125, CTC1063, CTC1119, CTC1273 NRG1 independent models on the right). Boxplots show low and upper quartiles and median line is indicated. Whiskers, 1.5 × interquartile range. Two-sided Wilcoxon test was used. d. Boxplots showing FGFR2-3-4 mRNA expression (normalized counts) from RNAseq data. Cells are grouped according to NRG1 dependency (CTC1106, CTC596, CTC1296, CTC782, CTC775 NRG1 dependent models on the left, CTC1007, CTC1125, CTC1063, CTC1119, CTC1273 NRG1 independent models on the right). Boxplots show low and upper quartiles and median line is indicated. Whiskers, 1.5 × interquartile range. Two-sided Wilcoxon test was used. e. Correlation plot between Lapatinib sensitivity (AUC) and FGFR1 expression in n = 33 breast cancer cell lines. Data retrieved from DepMap portal (CTDv2 database). f. Correlation plot between drug sensitivity (n = 543 drugs) and FGFR1 expression in pan-cancer cell lines. Data retrieved from DepMap portal (CTDv2 database). g. Correlation plot between drug sensitivity (n = 543 drugs) and ERBB3 expression in breast cancer cell lines. Data retrieved from DepMap portal (CTDv2 database). h. Correlation plot between AZD4547 sensitivity (AUC) and ERBB3 expression in n = 33 breast cancer cell lines. Data retrieved from DepMap portal (CTDv2 database).

To functionally validate this finding, we treated FGFR1-overexpressing CDOs with a selective FGFR inhibitor (AZD4547)31. As shown in Fig. 4h, FGFR1-overexpressing CDOs were highly sensitive to AZD4547 in the absence of NRG1. Notably, cell viability reduction induced by FGFR inhibition was completely rescued by adding NRG1. We further validated the mutual compensatory effect of NRG1 and FGFR1 in our NRG1-independent CDX models (Extended Data Fig. 9b) as well as in all five NRG1-independent CDOs (Fig. 4i). Lower sensitivity to AZD4547 was observed in the presence of NRG1, demonstrating that in nongenetically manipulated CDOs, NRG1–HER3 signaling can also rescue cell viability reduction induced by FGFR1 inhibition.

Given the ability of NRG1 to confer resistance to FGFR1 inhibition, we conclude that the FGFR1 and NRG1–HER3 pathways are functionally interdependent in BC cells. This suggests that the cells exhibit adaptive plasticity, enabling them to switch between these pathways to promote survival, proliferation and ultimately metastasis. Accordingly, we investigated whether NRG1-dependent CDOs had lower baseline FGFR1 signaling levels. As shown in Fig. 4j, compared to NRG1-dependent cells, NRG1-independent cells indeed showed overall higher FGFR1 mRNA expression. These findings were confirmed using RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data (Extended Data Fig. 9c) and were specific to FGFR1 (Extended Data Fig. 9d). Importantly, NRG1-independent CDOs displayed a corresponding enrichment in an FGFR1 activation signature (Fig. 4k). To corroborate these findings in a larger and independent cohort, we interrogated DepMap datasets. A positive correlation between FGFR1 expression and resistance to lapatinib was observed not only in BC cell lines (Fig. 4l and Extended Data Fig. 9e) but also for the entire PanCancer dataset (Extended Data Fig. 9f). In line with this, ERBB3 expression positively correlated with resistance to the FGFR inhibitor AZD4547 (Extended Data Fig. 9g,h).

Together, these results demonstrate that the plastic engagement of either FGFR1 or HER3 allows cancer cells to adapt to different environmental cues.

Combined NRG1 and FGF inhibition eradicates CDOs

Driven by the observation of the mutual plasticity between NRG1–HER3 and FGFR1 signaling, we hypothesized that concurrent inhibition of both pathways would be most effective in eliminating CDOs. We tested this hypothesis by performing viability assays on both NRG1-dependent and NRG1-independent CDOs treated with lapatinib or AZD4547 alone or in combination (Fig. 5a). Although NRG1-dependent CDOs (CTC596, CTC1106, CTC782, CTC775 and CTC1296) were highly sensitive to lapatinib, NRG1-independent CDOs were more resistant (Fig. 5b). Generally, CDOs showed resistance to AZD4546 in the presence of NRG1. As expected, combination treatment with lapatinib and AZD4547 was significantly more effective than either of the two drugs alone in all CDOs, regardless of their dependency on NRG1. These findings were also confirmed in the NRG1-independent CDX model. Although combination treatments in the absence of NRG1 eliminated all viable cells, NRG1 stimulation supported cellular viability in the presence of both drugs yet significantly less than treatment with either of the drugs alone (Fig. 5c). Furthermore, although lapatinib alone caused strong suppression of AKT/ERK activity downstream of HER2/HER3 stimulation in NRG1-dependent lines, combination treatment blocked AKT/ERK phosphorylation in both NRG1-dependent and NRG1-independent cells (Fig. 5d).

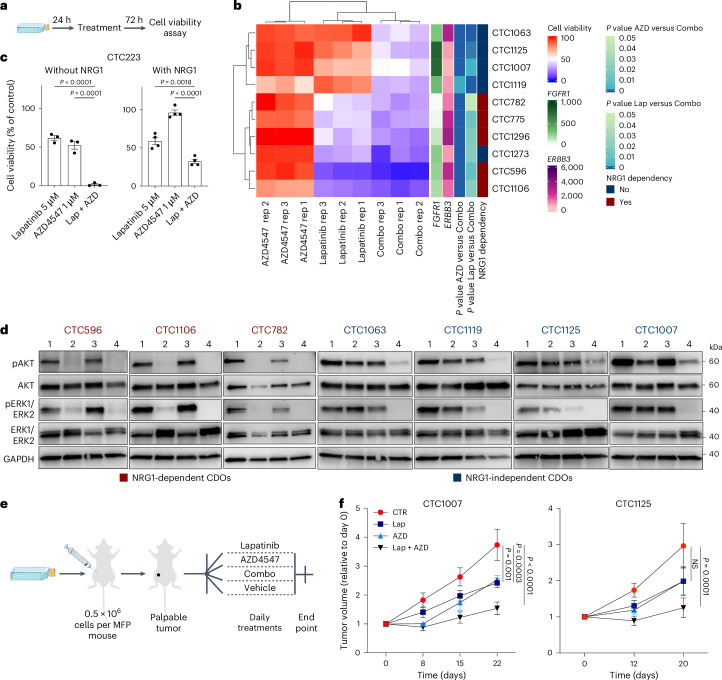

Fig. 5. Combined inhibition of NRG1 and FGF signaling leads to CDOs elimination.

a, Experimental design of the drug screening experiment in CDOs. b, Heat map showing relative viability of different CDOs (rows) in the presence of lapatinib (Lap), AZD4547 (AZD) or lapatinb + AZD4547 (combo). Each column represents one biological replicate; each condition has three biological replicates (rep1–3). FGFR1 and ERBB3 expression (RNA-seq normalized counts) as well as statistical analyses (one-way ANOVA with a Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test) were added as additional annotation. A CTB assay was performed after 72 h of treatment. CTB fluorescence values were normalized to the viability of control cells incubated with vehicle only. c, Bar plot showing relative viability of CTC223 cells in response to lapatinib or AZD4547 alone or lapatinb + AZD4547 in the absence (left, n = 3 biological replicates) or presence (right, n = 4 biological replicates) of NRG1. A CTB assay was performed 72 h after treatment. CTB fluorescence values were normalized to the viability of control cells incubated with vehicle only. Bars represent the mean, error bars indicate s.e.m., and each dot represents an experiment. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (Lap + AZD versus Lap, P < 0.0001; Lap + AZD versus AZD, P = 0.0001 without NRG1; Lap + AZD versus Lap, P = 0.0018; Lap + AZD versus AZD, P < 0.0001 with NRG1). d, Western blot analysis of whole-cell protein lysates derived from CDOs treated with DMSO, lapatinib, AZD4547 or lapatinb + AZD4547 for 12 h. Phosphorylated and total protein kinase B (AKT) and ERK1/ERK2 were detected. GAPDH was used as the loading control; n = 1; lane 1, DMSO; lane 2, 5 μM lapatinb; lane 3, 1 μM AZD4547; lane 4, lapatinb + AZD4547. e, Experimental design of drug treatment in vivo. f, Plots showing increases in tumor volume over time in PDXs treated with vehicle (red), lapatinib (blue), AZD4547 (turquoise) or lapatinib + AZD4547 (black). Tumor volume was measured with a digital caliper and normalized to the volume at baseline (day 0). Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.; n = 6 mice per group. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (CTC1007 Lap + AZD versus CTR, P < 0.0001; Lap versus CTR, P = 0.0003; AZD versus CTR, P = 0.001; CTC1125 Lap + AZD versus CTR, P = 0.0001; Lap versus CTR and AZD versus CTR, not significant).

As proof of concept, with the aim of translating these findings into an in vivo setting, we transplanted two TNBC NRG1-independent CDOs (CTC1007 and CTC1125) into the mammary fat pads of NSG mice and performed in vivo drug treatment (Fig. 5e). As shown in Fig. 5f, although a mild tumor reduction was observed when mice were treated with either lapatinib or AZD4547 alone, a stronger reduction was achieved following combined treatment in both models.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that simultaneous inhibition of NRG1–HER3 and FGF–FGR1 signaling pathways impaired CTC survival and proliferation in vitro and tumor formation in vivo.

FGFR1 expression in therapy-resistant BC cells

Considering that, after initial response, most individuals will ultimately develop resistance to HER2-targeted therapies32, we first interrogated our single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) dataset to explore FGFR gene expression in uncultured MBCP-derived CTCs (Fig. 6a and Extended Data Fig. 10a). FGFR1 expression levels were heterogeneous and higher in participants treated with anti-HER2/HER3 therapy regimens administered before liquid biopsy collection (Fig. 6b (participant CTC595 progressed on different lines of anti-HER2/HER3 therapy) and Supplementary Table 1). ERBB3– CTCs showed a positive correlation with FGFR1 expression and functional signatures representing FGFR1 activation in all three participants (R = 0.26–0.73). Interestingly, the strongest correlations (R = 0.65–0.73) were found in participant 595 (Fig. 6c). These analyses suggest the functional activity of FGFR1 and its downstream pathway in ERBB3– CTCs, particularly in individuals resistant to HER2/HER3-targeted therapy.

Fig. 6. FGFR1 expression is functionally relevant in therapy-resistant BC cells.

a, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot from scRNA-seq analysis from Fig. 3c. Each dot represents one putative CTC, and the color gradient is based on FGFR1 expression. b, Dot plot showing FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3 and FGFR4 expression in putative CTCs from each participant (CTC250, CTC595 and CTC596). Below each participant ID, the treatment received before collection of the liquid biopsy is specified (more details are available in Supplementary Table 1). c, Correlation dot plot of HER3, NRG1 and FGFR1 signatures. Mean z scores per CTC were computed for the HER3 signature, the Nagashima NRG1 signature and three FGFR1-related Reactome gene sets and were correlated against FGFR1 expression (exp) and the HER3 and Nagashima signature scores. Pearson correlations were computed per participant using only the non-ERBB3-expressing CTCs. d, Schematic workflow of longitudinal sample collection in the CATCH cohort for transcriptomic analysis. e, Left: box plot showing FGFR1 expression levels assessed by RNA-seq in matched biopsies before and after drug treatment. Treatments are indicated by color. Righ:, box plot showing FGFR1 expression in matched biopsies before and after drug treatment with either PI3Kα inhibitors (pink) or anti-HER2 (turquoise). Each dot represents a participant. f, Growth curve of CTC1106 cells (effusion, t2) in the reported medium. Cells were counted weekly for 1 month. Dots represent the mean; n = 3 technical replicates. g, Plot representing FGFR1 expression in CTC1106 CDOs established from the first (t1, blue; n = 3 biological replicates) and second (t2, gray; n = 2 biological replicates) time points measured. Data were analyzed by two-tailed unpaired t-test; P = 0.0101. h, GSEA using the Reactome downstream signaling of activated FGFR1 signature on data from CTC1106 CDOs established from the first (t1) and second (t2) time points. i, Plot showing the frequency of wells with two or more live cells in a clonogenic assay using CTC1106 models. Counting was performed 14 days after single-cell FACS seeding in CTC medium without NRG1. Data were analyzed by two-tailed paired t-test; P = 0.0024 (n = 4 biological replicates). j, Graphical abstract.

Extended Data Fig. 10. FGFRs expression in CTCs and body weight during in vivo treatments.

a. UMAP plot from scRNAseq analysis. Each dot represents one putative CTC, the color gradient is based on the expression of the indicated gene. b. Plot showing body weights of mice monitored over time in PDX1007 treated with vehicle (red), Lapatinib (blue), AZD4547 (turquoise) or Lapatinib+AZD4547 (black). Data are mean ± standard deviation, n = 6 mice per group.

To test whether individuals who developed resistance to HER2/HER3 or PI3K inhibitors (HER2/HER3 downstream effector) show increased FGFR1 expression, we collected RNA-seq data from the Heidelberg CATCH cohort25 of matched longitudinal biopsies before (t1) and after (t2; progressive disease) therapy (Fig. 6d). Heterogeneous FGFR1 expression was observed in all (n = 14) matched longitudinal samples (Fig. 6e). However, in individuals receiving HER2/HER3 or PI3KA inhibitors (n = 4), increased FGFR1 expression was observed at t2. This observation supports the finding that FGFR1 pathway activation represents an escape mechanism in individuals treated with HER2/HER3 signaling pathway-inhibiting drugs.

To further validate the role of the NRG1–HER3 and FGF–FGFR1 pathways in CTC survival and proliferation, we processed a liquid biopsy from participant CTC1106 (t2; Fig. 2i). Following hematopoietic cell depletion and live-cell sorting via FACS, the isolated CTCs were plated in complete CTC medium but with the following modifications: (1) standard with NRG1 and FGF, (2) without FGF, (3) without NRG1 and (4) without both NRG1 and FGF. As expected, complete CTC medium supported initial CTC survival and subsequent proliferation over time. Conversely, the absence of both NRG1 and FGF in the CTC medium resulted in a dramatic reduction of CTC survival and failed to sustain their proliferation, demonstrating that both NRG1 and FGF are essential. In medium lacking only FGF, CTC growth was modestly impaired. However, culturing in the absence of NRG1 (gray line) resulted in substantially reduced CTC expansion over time, highlighting its critical role in CTC proliferation and survival (Fig. 6f).

Finally, using the longitudinal CTC1106 CDOs (Fig. 2i), we further assessed the plastic interplay between FGFR1 and HER3. Notably, FGFR1 expression was significantly increased after alpelisib treatment (t2; Fig. 6g), which correlated with an enrichment of the FGFR1 activation signature (Fig. 6h). We then functionally linked the increased expression of FGFR1 with a reduction of NRG1 dependency. As shown in Fig. 6i, CTC1106 t2 showed a significantly stronger clonogenic ability in the absence of NRG1 than CTC1106 t1. These data show the relevance of the NRG1–HER3 and FGF–FGFR1 compensatory mechanism in longitudinal samples, suggesting FGFR1 upregulation as a potential escape mechanism of BC cells that develop treatment resistance (Fig. 6j).

Discussion

To date, MBC is an incurable disease and represents the second leading cause of death from cancer among women33. CTCs are the source of metastasis, but long-term expansion in vitro has been a major challenge preventing their functional interrogation. Here, we report the establishment and characterization of 17 long-term CDOs originating from liquid biopsies derived from 16 MBCPs spanning the different BC subtypes. Although 6 models were obtained from CDXs or EDXs, 11 CDOs were generated directly from effusion samples or peripheral blood (either by DLA or blood withdrawal) without any initial pre-expansion in vivo. Importantly, these CDOs can allow the investigation of molecular pathways crucial for CTC survival and can also be used as a preclinical model suitable for drug screening and therapy resistance studies in a personalized approach. Moreover, our platform is suitable for serial longitudinal isolation and expansion of tumor cells from MBCPs to monitor disease progression and therapy responses. Although our cohort size is limited and the paucity of data available from BC CTC cultures hinders statistically significant conclusions, copy number and single-nucleotide variant analyses of the CDOs do not provide evidence that our culture condition is selective for the growth of CTCs from individuals with specific genomic profiles. The most critical variable appears to be the starting number of cultured CTCs. By focusing on individuals with over 100 CTCs, this study necessarily limited its applicability to a narrower range of individuals. However, we showed that the use of alternative liquid biopsies like DLA or pleural and peritoneal effusions can overcome this limitation.

CTCs represent a heterogeneous population, with only a fraction able to survive, extravasate and seed distant metastases. The ability of certain CTCs to survive is a crucial step during metastasis formation. Our data identify NRG1–HER3 signaling as one of the key players mediating this process. Indeed, NRG1 enabled the establishment of robust in vitro conditions, which allowed initiation and long-term expansion of primary CTCs. Accordingly, in vivo data show that HER3+ CTCs represent a highly aggressive subpopulation with superior survival and metastatic potential.

In response to extrinsic factors, such as drug treatments, phenotypic plasticity can contribute to the heterogeneity of CTCs, leading to treatment resistance11. Here, we provide evidence of a complementary mechanism of action in which cells can switch between HER3 and FGFR1 to promote growth and survival via AKT–ERK pathways. As a consequence, combined blockade of NRG1 and FGF signaling resulted in sustained growth inhibition of CDOs both in vitro and in vivo. These findings are in line with other studies where the cross-talk between FGFRs and ERBB family members have been hypothesized to mediate therapy resistance in liver cancer34,35, lung cancer36 and BC37. In addition, amplification of FGF signaling has been shown to promote resistance to HER2 inhibition in HER2+ BC38. The ability of FGFR1 to upregulate NRG1 was recently reported in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma39; however, we did not observe this phenomenon in our models.

To inhibit the HER2/HER3 pathway, we used lapatinib, a reversible, ATP-competitive tyrosine kinase inhibitor of HER2 that has been approved for treatment of HER2+ BC for a decade. Alternative strategies are at different stages of approval and may offer more effective options. Based on our in vitro, in vivo and ex vivo data, MBCPs with advanced disease and HER3-expressing CTCs will likely benefit from treatment with last-generation HER3 inhibitors, such as patritumab deruxtecan, a HER3-directed antibody-drug conjugate recently approved for the treatment of metastatic EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer40,41 with encouraging results in early BC42. Ideally, the subsequent addition of an FGFR1 inhibitor would prevent potential adaptive resistance mediated by cell plasticity.

Methods

All research performed in this study complied with all relevant German ethical regulations.

Clinical specimens

Liquid biopsy samples (pleural and ascitic effusions and peripheral blood withdrawals) were obtained from MBCPs participating in the CATCH (Comprehensive Assessment of Clinical Features and Biomarkers to Identify Patients with Advanced or Metastatic Breast Cancer for Marker Driven Trials in Humans) trial at the Division of Gynecologic Oncology, NCT Heidelberg (case number S-164/2017). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Participant and tumor characteristics are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. CTC-specific assessments were further approved by the ethical committee of the University of Heidelberg (case number S295/2009) and University of Mannheim (2010-024238-46).

EDX and CDX models

The procedure for generating orthotopic xenografts from effusion was first described by Al-Hajj et al.43 and was recently refined by our group19; peripheral blood withdrawal was previously described by our group1.

CTC enumeration

Blood samples were collected in CellSave tubes (Menarini Silicon Biosystems) and run with CellSearch (Menarini) using the CTC kit (Menarini) at the Department of Tumor Biology, Hamburg, according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Blood samples

Peripheral blood samples were directly collected in Vacutainer CPT tubes (BD Biosciences) and processed following the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Leukapheresates

MBCPs with ≥10 CTCs per 7.5 ml of blood were asked to participate in the CTC leukapheresis study, approved by the ethical committee of the University of Heidelberg (case number S-408/2013). DLA was performed at the Medical University Hospital Heidelberg using a Spectra Optia (Terumo BCT) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Plasma and CTCs were collected using the cMNC program with a reduced packing factor of 4.5 and with 2–3% hematocrit.

Apheresate products were immediately collected and processed under sterile conditions. Depletion of blood cells was performed using Miltenyi Biotec microbeads (anti-CD45, 130-045-801; anti-CD3, 130-050-101; anti-CD31, 130-091-935; anti-CD16, 130-045-701; anti-CD235a, 130-050-501; each 20 µl per 107 cells).

FACS and flow cytometry

Cells were stained in PBS + 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 2 mM EDTA using the following antibodies: EpCAM-FITC and APC-Vio770 (clone HEA-125, REA764 Miltenyi Biotec, 1:50), CD45-VioBlue (REA747 clone, Miltenyi Biotec, 1:50), HER3-PE (66223 clone, FAB3481P, R&D, 1:20), CD31-VioBlue (clone AC128, Miltenyi Biotec, 1:50), CD16-VioBlue (clone REA423, Miltenyi Biotec, 1:50), CD41-VioBlue (clone REA386, Miltenyi Biotec, 1:50) and CD235a-VioBlue (clone REA175, Miltenyi Biotec, 1:50). Propidium iodide (PI; P3566, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:1,000) or DAPI (D1306, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:1,000) was used to exclude dead cells. The following antibodies were used for the analysis of xenograft-derived samples (all anti-mouse, PacificBlue, Biolegend): CD45 clone 30-F11 (103116, 1:1,000), CD11b clone M1/70 (101226, 1:2,000), TER-119/Ly-76 clone TER-119 (116223, 1:200), Ly-6G clone 1A8 (A25985, 1:2,000), CD31 clone 390 (102422, 1:1,000) and H-2Kd clone SF1-1.1 (116629, 1:50).

Cells were sorted and analyzed using a FACSAria Fusion and LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences). BD FACSDiva software and FlowJo software were used for analysis.

Determination of NRG1 blood concentration

NRG1 concentration in blood samples from MBCPs was measured with a Human NRG1 ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was determined on a SpectraMax iD3 microplate reader.

Long-term in vitro expansion of CTCs

Immediately after FACS or immunomagnetic sorting, the CTC-enriched cell suspension was centrifuged, the supernatant was carefully removed, and the pellet was resuspended in the appropriate volume of CTC medium, transferred to a plate (Corning, Primaria) and cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 5% O2. Medium was partially replaced every 48–72 h. When cluster formation was detected, cells were collected, dissociated with Accutase (Sigma, Life Technologies) and expanded in larger plates and subsequently in flasks. Floating three-dimensional collagen gels with a final concentration of 1.3 mg ml–1 collagen I (Corning) were prepared as previously described with minor modifications20. NRG1 concentration used in the medium and in all experiments was 20 ng ml–1 unless otherwise specified. The medium recipe was licensed to Miltenyi Biotec, and the optimized formulation is available under the name ‘Breast TumorMACS Medium’; only Y27632 has to be added separately according to the manufacturer’s instructions (StemMACS Y27632, 130-103-922).

The cells were confirmed to be negative for contaminants (no Mycoplasma, Squirrel Monkey Retrovirus, Epstein-Barr virus or interspecies contamination was detected) by the Multiplex Cell Contamination Test (Multiplexion)44. To test cross-contamination with commercially available cell lines, single-nucleotide polymorphism fingerprints were extracted from RNA-seq data on CDOs in vitro and publicly available RNA-seq data from BC and acute myeloid leukemia cell lines from CCLE45 (PRJNA523380) using ExtractFingerprints and CrosscheckFingerprints from GATK4 (ref. 46). Briefly, given a BAM/SAM/VCF file, single-nucleotide polymorphisms in specific highly variable genomic locations were extracted and calculated. Concordance between fingerprints was estimated, and the logarithm of the odds score for identity was calculated (Extended Data Fig. 4a).

The match between CDOs and corresponding participant material was confirmed by ExtractFingerprints and CrosscheckFingerprints from GATK4 on whole-genome sequencing data (Extended Data Fig. 4b).

Clonogenic assay

Single-cell suspensions were obtained by treating cells with Accutase at 37 °C for 5 min. Cells were washed with PBS, spun down, resuspended in a PBS solution containing 1% BSA, 2 mM EDTA and DAPI and filtered through a 40-µm cell strainer. Cells were sorted using a FACSAria Fusion (BD Biosciences) coupled with BD FACSDiva Software using a 100-μm nozzle. After morphological gating using forward and side scatter, we excluded duplets and dead cells (DAPI+) and sorted one single cell per each well of a 96-well plate, previously filled with 200 µl of medium. All plates were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 20.9% O2 for normoxia and 5% O2 for hypoxia. After 2 or 4 weeks, cells were checked and counted under brightfield microscopy.

CRISPR–Cas9-mediated ERBB3 KO

ERBB3-KO gRNA sequences (Supplementary Table 1) were cloned into the pLKO.005 backbone of the pLKO5.sgRNA.EFS.tRFP657 plasmid, as previously described47,48. The correct assembly of the resulting DNA plasmids was confirmed using Sanger sequencing. Lentivirus production was performed using a second-generation lentivirus system (psPAX2, Addgene plasmid 12260; pMD2.G, Addgene plasmid 12259). Viral supernatant was collected 48 h after transfection, passed through a 450-nm filter, ultracentrifuged at 4 °C for 120 min, resuspended in cold PBS and stored at −80 °C until use. CTC223 cells were transduced with pCW-Cas9-tGFP plasmid. After 4 days of incubation, the GFP–Cas9+ CTC223 cells were sorted by FACS, expanded and transduced with pLK05-gRNA1-tRFP (ERBB3-KO1), pLK05-gRNA2-tRFP (ERBB3-NF) or pLK05-EV-tRFP (EV). GFP+tRFP+ cells were sorted by FACS and expanded. After 10 days, ERBB3 KO was induced by adding 1 μM doxycycline hydrochloride to the medium for 96 h and exchanging the medium after 48 h.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was measured using the CTB (Promega) assay. Specifically, 8,000–10,000 cells were seeded under the appropriate medium conditions in each well of a 96-well multiwell plate. The day after, the following compounds were added: AZD4547 (S2801), lapatinib (S2111), taselisib (S7103) and alpelisib (S2814; all purchased from Selleckchem).

Cell cycle analysis

In total, 1 × 105 cells per well were seeded in G1 medium. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with G1, G2, G1 + NRG1, G1 + Y27632 and G1 + NRG1 + Y27632. After 48 h, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU; 1:1,000) of a Click-iT Plus EdU Alexa Fluor 647 Flow Cytometry Assay kit (Invitrogen) was added. After 3 h, cells were processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions and analyzed using an LSR Fortessa.

Apoptosis assay

In total, 1 × 105 cells per well were seeded in G1, G2, G2 without NRG1 or G2 without Y27632. After 48 or 120 h, cells were washed with PBS and detached with Accutase. Cells were then stained in 1× Annexin V Binding buffer with 1:20 PI and 1:100 Annexin V-PE. After 15 min of incubation at room temperature, samples were measured using an LSR Fortessa. The fractions of alive (PI–Annexin–), early apoptotic (PI–Annexin+), late apoptotic (PI+Annexin+) and necrotic (PI+Annexin–) cells were determined using FlowJo software.

Synergism between NRG1 and Y27632

To investigate the synergistic effect of NRG1 and Y27632 on CTC proliferation, we used a linear model to describe cell viability. This model included binary variables for NRG1 treatment, Y27632 treatment and their combination. To test for synergy, we compared two generalized linear mixed models: one with and one without an interaction term for the double treatment. An ANOVA revealed a significant improvement in the model with the interaction term (P = 1.25 × 10–6), indicating a synergistic effect.

Mouse studies

Animal care and procedures followed German legal regulations and were previously approved by the governmental review board of the state of Baden-Württemberg, operated by the local Animal Welfare Office (Regierungspräsidium Karlsruhe) under license numbers G-240/11, G-115/17 and G-104/22. Mice were housed in individually ventilated cages under temperature and humidity control. Cages contained an enriched environment with bedding material.

In vivo preclinical model for micrometastases

Luciferase-labeled CDX models were injected into the fourth mammary fat pad of female NSG mice that were at least 6 weeks old. Cells were resuspended in a 1:1 ratio of sterile PBS and growth factor-reduced Matrigel (BD). All mice received subcutaneous implantation of β-estradiol as solid pellets (Innovative Research of America), as previously described1. Primary tumors were resected after reaching a size of ~0.5 cm3. Micromestastasis formation was monitored by measuring bioluminescent signal using an IVIS Spectrum Xenogen device (Caliper Life Sciences). Animals were killed, and micrometastasis-containing organs were collected.

CDX generation

NSG mice were transplanted with 1 × 106 cells in the fourth mammary fat pad, as described above. Tumor growth was monitored, and mice were killed when end point criteria were reached.

In vivo lung colonization assay

In total, 1 × 105 cells in 100 µl of PBS were injected via the tail vein. Lung colonization was monitored by measuring bioluminescent signal using an IVIS Spectrum Xenogen machine (Caliper Life Sciences). Bioluminescence analysis was performed using Living Image software version 4.4 (Caliper Life Sciences).

In vivo drug treatments

Tumor growth was monitored, and drug treatment was initiated when primary tumors were palpable. Mice were treated by oral gavage daily with vehicle (0.1% Tween 80/0.5% Na-CMC, 100 μl), 100 mg per kg (body weight) lapatinib, 10 mg per kg (body weight) AZD4547 or 100 mg per kg (body weight) lapatinib + 10 mg per kg (body weight) AZD4547 all in 0.1% Tween 80/0.5% Na-CMC (100 µl). Tumor size was recorded weekly using digital calipers. Animal weight was recorded daily to monitor potential drug toxicity. At the experimental end point, the maximal tumor size (1.5 cm3) was not exceeded. None of the treatments had major toxic effects in vivo (Extended Data Fig. 10b).

Gene expression analysis by quantitative PCR

Cells were collected, washed with PBS and centrifuged. RNA extraction was performed using miRNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) or PicoPure kit (Thermo Fisher), depending on the cell number, following the manufacturers’ instructions. RNA concentration and purity were determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Reverse transcription (RT) was performed using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosciences) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Quantitative PCR was performed using 0.5 μl of forward and reverse primers (10 μM stock solution), 5 μl of Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Life Technologies), 3 μl of nuclease-free water and 1 μl of 1:10 diluted cDNA. The reaction was run on a Thermo Fisher ViiA-7 Real-time PCR system. Data were analyzed using the comparative cycling threshold (ΔΔCt) method. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 5.

Gene expression analysis of the PDX model

Primary tumor and metastatic tissues derived from our PDX mouse model were freshly processed using the GentleMACS system (Miltenyi Biotec) to obtain a single-cell suspension. Live tumor cells were sorted by FACS into RNA lysis buffer (Arcturus PicoPure RNA Isolation kit, Life Technologies, Invitrogen). RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene expression analysis was performed using Affy Human U133Plus 2.0 at the Genomics and Proteomics Core Facility of the German Cancer Research Center (GPCF DKFZ, Heidelberg).

To test differences in lung metastases versus primary tumors, genes were ranked based on log fold change. GSEA was performed with the R package gage (v2.36.0) and default settings using the C2 curated gene sets from MSigDB (v7.4). For the top hit (Nagashima NRG1 signaling up) as well as our custom HER3 signature (Supplementary Table 3 and scRNA-seq analysis), GSEA was performed with the R package fgsea (v1.12.0) and default settings to produce the plots in Figs. 1d and 3e, respectively.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA-based protein lysis buffer. Protein concentration was determined using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit (Thermo). After blocking for 1 h at room temperature with 1× Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20 buffer containing 5% BSA, membranes were incubated overnight with the appropriate primary antibodies diluted 1:1,000 in blocking buffer. Antibodies to phospho-HER3/ERBB3 (Tyr 1289; 21D3; rabbit monoclonal 4791), HER3/ERBB3 (D22C5; XP rabbit monoclonal 12708), FGFR1 (D8E4; XP rabbit monoclonal 9740), phospho-AKT (Ser 473; D9E; XP rabbit monoclonal 4060), AKT (pan; C67E7; rabbit monoclonal 4691), phospho-p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/ERK2; Thr 202/Tyr 204; D13.14.4E; XP rabbit monoclonal 4370), p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/ERK2; 137F5; rabbit monoclonal 4695), phospho-FAK (Tyr 397; D20B1; rabbit monoclonal 8556), FAK (rabbit polyclonal 3285) and GAPDH (14C10; rabbit monoclonal 2118) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Monoclonal anti-α-tubulin T5168 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

IHC analysis

Sections from fixed CDOs or tissues were obtained, processed and stained as previously described49, with minor modifications. The following antibodies were used: anti-EpCAM (Agilent Dako, clone Ber-EP4, 1:100), anti-human KRT19 (Agilent Dako, clone RCK108, 1:50), anti-human Ki-67 (Agilent Dako, clone Ki-67, 1:1,000), anti-ERα (Thermo Fisher Scientific, clone SP1, 1:50), anti-CDH1 (Agilent Dako, clone M3612, 1:30) and anti-vimentin (Agilent Dako, clone M7020, 1:1,000). For HER3 expression, we incubated samples with anti-HER3/ERBB3 (D22C5, XP rabbit monoclonal 12708, 1:50) at 4 °C overnight and used heat-induced antigen unmasking with damp heat at 90 °C with EDTA unmasking solution (pH 9 (1:10); 14747 Signal Stain) for 30 min. Sections were scanned using a Zeiss AxioScan, and representative images are shown.

Targeted next-generation sequencing of somatic mutations

Genomic DNA was extracted from CDOs and CDXs. DNA concentration was assessed by fluorimetric measurement using a QuBit 3.0, and the amount of amplifiable DNA (sequencing-grade quality) was determined using a quantitative assay (TaqMan RNaseP detection assay) on a StepOnePlus instrument (both Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were amplified using a custom-designed gene panel for BC50, covering the most recurrent mutations51. Library preparation and sequencing were performed using multiplex PCR-based Ion Torrent AmpliSeq (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Ion S5XL technology, as previously described52.

Bulk RNA-seq of CDOs

CTCs were collected, washed in PBS and lysed in RNA lysis buffer. RNA was extracted using a PicoPure RNA isolation kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and quality were assessed by Bioanalyzer (Agilent). Libraries were prepared using 5 ng of total RNA with an NEBNext Single Cell/Low Input RNA Library Prep kit (New England Biolabs) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Library concentration was quantified with QuBit, and library size distribution was assessed by Bioanalyzer. Up to 15 libraries were pooled equimolarly and sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 S1 (paired-end, 150 base pairs).

Bulk RNA-seq analysis

Bcl2fastq2 2.20 was used for conversion. Reads were trimmed for adapter sequences and aligned to the 1000 Genomes Phase 2 assembly of the Genome Reference Consortium human genome (build 37, version hs37d5) with STAR53 (v2.5.3a) using the following parameters: alignIntronMax: 500,000; alignMatesGapMax: 500,000; outSAMunmapped: within; outFilterMultimapNmax: 1; outFilterMismatchNmax: 3; outFilterMismatchNoverLmax: 0.3; sjdbOverhang: 50; chimSegmentMin: 15; chimScoreMin: 1; chimScoreJunctionNonGTAG: 0 and chimJunctionOverhangMin: 15. GENCODE gene annotation (GENCODE release 19) was used for building the index. BAM files were sorted using SAMtools54 (v1.6), and duplicates were marked with Sambamba55 (v0.6.5). Raw counts were generated using featureCounts56 (Subread version 1.5.3).

For calculation of normalized counts, mitochondrial RNA, tRNA, rRNA and all transcripts from the Y and X chromosomes were removed, and normalization was performed in analogy to transcripts per million.

Differential gene expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 (ref. 56; v1.26.0). The lfcshrink function was used to define differentially expressed genes (| log2 (fold change) |) of ≥1, adjusted P value of ≤0.05). The log2 (fold change) values (nonshrinked) were used for GSEA with clusterProfiler57 and the Molecular Signatures Database v7.411 as reference gene sets. Data handling was performed in R (v3.6.0) using RStudio (v1.4).

Gene expression analysis of human CTCs: scRNA-seq

From cryopreserved vials of CTC samples, single live Lin–EpCAM+ cells were directly sorted by FACS into 100 µl of TRIzol (Thermo Fisher). Samples were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. For RNA isolation, TRIzol samples were thawed on ice and mixed with 20 µl of chloroform. After incubation at room temperature for 3 min, samples were centrifuged (12,000g, 5 min, room temperature) and immediately transferred on ice. The aqueous phase was collected and mixed with 0.4 µl of GlycoBlue (Thermo Fisher) in 75 µl of isopropanol, and samples were stored at −20 °C for at least 5 days. Samples were centrifuged (13,000g, 1 h, 4 °C), and the pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and centrifuged again (13,000g, 15 min, 4 °C). The pellet was resuspended in 5 µl of Smart-Seq2 buffer. Whole-transcriptome amplification was performed using the modified Smart-Seq2 protocol as previously described58. Libraries were constructed using a Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation kit (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions but using one-fourth of all volumes. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform.

scRNA-seq analysis

Raw data processing was performed with kallisto59 (v0.43.0). The kallisto index file was generated with a hg38 transcriptome fasta file (release-98) downloaded from Ensembl, and reads were then pseudoaligned to the transcriptome with kallisto in quant mode. The R package tximport60 (v1.14.2) was used to perform gene-level summaries, and the resulting count matrix was imported as a SingleCellExperiment object in R.