Highlights

-

•

Identified key HR+BC subtypes, especially C3, linked to aggressive behavior and poor prognosis.

-

•

Highlighted the importance of the MK signaling pathway in tumor progression.

-

•

In vitro experiments confirmed that MAZ knockdown restrained tumor progression.

-

•

High PCLAF+ tumor risk scores were associated with poorer survival outcomes.

-

•

Personalized treatment strategies targeting vulnerabilities of HR+BC subtypes could improve clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Single-cell RNA sequencing, Hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, Tumor microenvironment, Prognosis, Immunotherapy

Abstract

Background

Breast cancer had been the most frequently diagnosed cancer among women, making up nearly one-third of all female cancers. Hormone receptor-positive breast cancer (HR+BC) was the most prevalent subtype of breast cancer and exhibited significant heterogeneity. Despite advancements in endocrine therapies, patients with advanced HR+BC often faced poor outcomes due to the development of resistance to treatment. Understanding the molecular mechanisms behind this resistance, including tumor heterogeneity and changes in the tumor microenvironment, was crucial for overcoming resistance, identifying new therapeutic targets, and developing more effective personalized treatments.

Methods

The study utilized single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data sourced from the Gene Expression Omnibus database and The Cancer Genome Atlas to analyze HR+BC and identify key cellular characteristics. Cell type identification was achieved through Seurat's analytical tools, and subtype differentiation trajectories were inferred using Slingshot. Cellular communication dynamics between tumor cell subtypes and other cells were analyzed with the CellChat. The pySCENIC package was utilized to analyze transcription factors regulatory networks in the identified tumor cell subtypes. The results were verified by in vitro experiments. A risk scoring model was developed to assess patient outcomes.

Results

This study employed scRNA-seq to conduct a comprehensive analysis of HR+BC tumor subtypes, identifying the C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells subtype, which demonstrated high proliferation and differentiation potential. C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells subtype was found to be closely associated with cancer-associated fibroblasts through the MK signaling pathway, facilitating tumor progression. Additionally, we discovered that MAZ was significantly expressed in C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells subtype, and in vitro experiments confirmed that MAZ knockdown inhibited tumor growth, accentuating its underlying ability as a therapeutic target. Furthermore, we developed a novel prognostic model based on the expression profile of key prognostic genes within the PCLAF+/MAZ regulatory network. This model linked high PCLAF+ tumor risk scores with poor survival outcomes and specific immune microenvironment characteristics.

Conclusion

This study utilized scRNA-seq to reveal the role of the C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells subtype in HR+BC, emphasizing its association with poor prognosis and resistance to endocrine therapies. MAZ, identified as a key regulator, contributed to tumor progression, while the tumor microenvironment had a pivotal identity in immune evasion. The findings underscored the importance of overcoming drug resistance, recognizing novel treatment targets, and crafting tailored diagnosis regimens.

Graphical abstract

The workflow diagram of this study.

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) was the most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women worldwide [1]. Its incidence exceeded 2 million cases annually, with more than 680,000 deaths [2]. According to the latest statistics from the American Cancer Society, by 2024, 42,250 women in the United States were expected to die from BC, with the median age at diagnosis for women being 62 years. Hormone receptor-positive (HR+) / human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2-) was the most commonly encountered molecular subtype, with the highest incidence among White women, while Black women have a higher proportion of HR-/HER2-(triple-negative) BC [3]. Hormone receptor-positive breast cancer (HR+BC) was the most commonly identified subtype, accounting for 70 % of BC cases. Its main trait was the expression of estrogen receptor (ER) and/or progesterone receptor (PR) [4]. Out of the 300,000 BC patients in 2023, approximately 190,000 were diagnosed with HR+BC [5]. Although HR+BC tended to have a more favorable prognosis in its early stages compared to other subtypes like HER2- and triple-negative BC, the outlook for patients with advanced or metastatic HR+BC was still unfavorable [6,7].

Endocrine therapy was considered one of the primary treatment options for HR+BC [8]. Endocrine therapy mainly consisted of two categories of therapeutic medications, one was aromatase inhibitors, and the other was antiestrogens [9]. Clinical guidelines recommended first-line endocrine therapy with or without targeted therapy [10]. A phase 1b dose-expansion study of gedatolisib combined with palbociclib and endocrine therapy in women with HR+, HER2-advanced BC demonstrated encouraging objective response rate and reasonable safety [11]. Another study compared the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy combined with endocrine therapy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone, and neoadjuvant endocrine therapy alone, finding that combining neoadjuvant chemotherapy with endocrine therapy improved the objective response rate and pathological complete response in HR+BC patients [12]. Despite recent advances in endocrine therapy, 25–30 % of HR+BC patients developed primary or secondary resistance [13], and many patients with advanced disease ultimately developed resistance, leading to disease progression. Resistance due to endocrine drug resistance and new adjuvant treatments remained a challenge in HR+ BC treatment, and tumor heterogeneity and multiple molecular mechanisms also contributed to the emergence of resistance. Relapse caused by endocrine drug resistance and new adjuvant treatments was a challenge in the treatment of HR+BC. Currently, mechanisms of endocrine therapy resistance in BC included ER gene abnormalities, deregulated activation of cellular pathways, epigenetic regulation, and abnormal cell cycle regulation [14]. Additionally, studies showed that components of the tumor microenvironment (TME) had a significant impact on endocrine therapy resistance in BC and changes within the TME were key factors that contributed to resistance and drove disease progression [15]. The TME was the cellular environment in which the tumor existed. In addition to tumor cells, it included stromal cells, fibroblasts, immune cells (such as T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, natural killer cells, natural killer T cells, tumor-associated macrophages, etc.), and pericytes [[16], [17], [18]]. Recent research concentrated on the effect of the TME in endocrine resistance. The complex interactions between tumor cells and their surrounding stromal and immune components were found to promote tumor growth, immune evasion, and resistance to therapy [19,20]. Immune cells within the TME, including tumor-associated macrophages, were known to create an immunosuppressive environment that limited the effectiveness of treatments [21]. Targeting the TME, therefore, represented a promising approach to overcoming resistance and improving therapeutic outcomes.

In recent years, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) revolutionized cancer research by enabling the detailed study of tumor heterogeneity and TME at the single-cell level [[22], [23], [24]]. The technology facilitated the analysis of gene expression profiles at the single-cell level, uncovering the cellular composition and molecular interactions within the tumor. It was particularly useful in identifying distinct subtypes of cancer cells and immune cells that might contribute to therapy resistance.

In this study, we used scRNA-seq to explore the effect of the TME in HR+BC, with a particular focus on the molecular interactions that drove tumor progression and therapy resistance. Specifically, we identified MAZ (myc associated zinc finger protein), a transcription factor (TF) that played a dual regulatory role in transcription and was highly expressed in many malignant tumors [[25], [26], [27]], as a potential therapeutic target. Our experimental results provided evidence that MAZ expression was associated with poor prognosis in HR+BC. By utilizing two HR+BC cell lines (MDA-MB-361 and HCC1428), we performed in vitro functional assays to evaluate the impact of MAZ knockdown on tumor cell proliferation, invasion, and migration. The results showed that MAZ knockdown significantly reduced cell viability and metastatic potential, highlighting its key role in promoting tumor progression. One of the key innovations of this study was the identification of MAZ as a novel therapeutic target in HR+BC, particularly for patients with tumors characterized by a high proportion of C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells. Furthermore, we demonstrated the potential of combining MAZ-targeting strategies with immune-modulating therapies to overcome the immunosuppressive nature of the TME. We carried out additional research on the role of MK signaling pathway in mediating interactions between C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells and tumor-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) through CellChat analysis, identifying the MDK-NCL ligand-receptor pair as a key facilitator in this communication.

Our findings contributed to the growing body of evidence supporting the importance of the TME in HR+BC progression and therapy resistance. This study not only expanded our understanding of the molecular mechanisms driving tumor heterogeneity but also provided a solid foundation for the development of more personalized and effective treatment strategies in HR+BC. By targeting both tumor cells and their microenvironment, our goal was to improve patient outcomes, particularly for those with high-risk subtypes resistant to traditional therapies.

Materials and methods

Data sources

The HR+BC scRNA-seq data were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), with the GSE number GSE228499. The nine samples included in the single-cell analysis were GSM7122845, GSM7122846, GSM7122847, GSM7122848, GSM7122849, GSM7122850, GSM7122851, GSM7122852 and GSM7122853. In addition, bulk RNA-seq data were sourced from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) website (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), which included clinical information such as age, race, stage, and tumor clinical stages (T, M, N), as well as genetic variation data for BC patients. As our study used data from a public database, ethical review was not deemed necessary.

Processing of single-cell derived data

The gene expression data were imported using the R software (version 4.2.0) with the Seurat package (v4.3.0) [28]. Low-quality cells were excluded, and stringent quality control was applied to the single-cell data. Cells that aligned with the following criteria were incorporated into the research: (1) nFeature range (300–7500); (2) nCount range (500–100,000); (3) mitochondrial gene expression did not exceed 25 % of the total gene expression in the cell; (4) erythrocyte gene expression was limited to less than 5 % of the total gene expression. After quality control, we obtained a total of 26,360 cells.

All samples were normalized and scaled using the ``NormalizeData'' and ``ScaleData'' functions [[29], [30], [31]] in the Seurat R package (v3.1.4) [32], and the top 2000 most variable genes were selected using the ``FindVariableFeatures'' function [[33], [34], [35]] after filtering. Principal component analysis (PCA) was then performed using the Harmony R package (v0.1.1) to mitigate batch effects between datasets [36]. Finally, uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) [37,38] was applied to the top thirty principal components for dimensionality reduction and gene expression visualization [39].

Using inferCNV to distinguish tumor cells

Using the inferCNV R program (v1.6.0, https://github.com/broadinstitute/inferCNV), scRNA-seq data were analyzed for the Copy Number Variation (CNV) detection [[40], [41], [42]]. This analysis involved examining gene expression levels and chromosomal positions to infer CNV status, thereby distinguishing between normal and malignant tumor cells.

Cell type identification and annotation

Seurat's analytical tools were used to further investigate the heterogeneity and differentiation of HR+BC tumor cells and focused on the identification of subtype characterization based on unique genetic profiles identified through marker identification techniques compared to other cell type identification methods. Initially, we utilized the ``FindAllMarkers'' function with parameters like Threshold = 0.25, min.pct = 0.25, and min.diff.pct = 0.25 to ascertain differentially expressed genes (DEGs) among various cell clusters. Visualizing the expression patterns of these markers using Seurat's ``DotPlot'' and ``FeaturePlot'' tools provided insights into the molecular characteristics of each cluster. Manual curation and consultation of literature aided in annotating these cell types accurately.

Cancer preferences analysis

To assess the cancer phase preference for HR+BC subtypes, a specific calculation method was used to calculate odds ratios.

Enrichment analysis

In our investigation of HR+BC cells, we conducted comprehensive enrichment analyses using various computational tools. Gene Ontology (GO) [43,44] and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) were pivotal in identifying enriched pathways and biological processes associated with DEGs. Utilizing the ``ClusterProfiler'' R package (v4.6.0) [45], we assessed the significance of GO terms with an adjusted p-value threshold of less than 0.05 [[46], [47], [48]]. Additionally, we employed Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) to evaluate the enrichment scores of predefined gene sets based on the variability of gene expression data across samples.

Slingshot and pseudotime analyses of HR+BC subtypes

To investigate the development and differentiation of HR+BC tumor cell subtypes, we used Slingshot software (v2.6.0) to infer the cell lineage [49] of HR+BC subtypes differentiation. All analyses were performed on normalized data to ensure consistency and comparability. The normalization was conducted using the log-transformed counts per million methods to mitigate batch effects and improve the robustness of pseudotime trajectory inference. The ``getLineages'' and ``getCurves'' tools were then used to estimate the level of cell expression for each lineage and visualize their trajectories in the dimensionality reduction space. The criteria for determining the starting and ending points of differentiation trajectories were guided by biological prior knowledge of HR+BC tumor cell subtypes and their respective marker gene expressions.

Analysis of cell communication

In our study of cell-cell communication dynamics, we utilized the "CellChat" R package (v1.6.1) [50] to analyze intercellular interactions across various cell types, which allowed us to conceive regulatory networks based on ligand-receptor levels and infer complex communication patterns [[51], [52], [53]]. We employed functions such as ``netVisual_diffInteraction'' to visualize variations in communication strength between cells and ``identifyCommunicationPatterns'' to estimate the number of communication patterns present. We then utilized the CellChatDB database (http://www.cellchat.org/) to identify the associated signaling pathways and receptor pairs. Our analysis involved setting a significance threshold with a p-value of 0.05 to assess the statistical significance of these interactions, enhancing our understanding of the intricate cellular dialogues observed in our scRNA-seq data.

Gene regulatory landscape

To identify stable cell states and evaluate transcriptional activity, we used the pySCENIC package (v0.10.0) in Python (v3.7) with default parameters [54]. The key default parameters included a minimum regulon size of 30 genes, motif database from JASPAR 2020, AUCell score threshold of 0.2, 100 random permutations for AUCell score significance, and 50 principal components for dimensionality reduction. The threshold for identifying important transcription factors was determined based on their regulon specificity score and AUCell activity. A TF was considered significant if its regulon activity was among the top 10 % across all tumor subtypes and exceeded a 1.5-fold enrichment over background.

Construction and verification of the model for HR+BC

To validate the predictive capabilities of a model based on PCLAF+ tumor cell scores in HR+BC, we obtained relevant data from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Initially, univariate Cox regression analysis was carried out to determine genes significantly linked to prognosis [[55], [56], [57]]. To address multicollinearity among the genes, we applied Lasso regression [58] for further refinement, which allowed us to select prognostic genes. A multivariate Cox regression analysis was then conducted to identify key prognostic genes [59]. We calculated the coefficient values of these genes, and established a risk scoring formula: Risk score = ∑_in (Xi × Yi), where X represented the coefficient, and Y represented the gene expression level. The optimal cutoff value for categorizing patients into high and low-risk groups was determined using the ``surv_cutpoint'' function.

For model validation, Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis [[60], [61], [62], [63], [64]] was conducted to judge the predictive accuracy of the model, and Kaplan-Meier survival curves were implemented to differentiate survival differences between the risk groups. To further evaluate the predictive power, we used the Time ROC package (v0.4.0) to generate ROC curves for 1, 3, and 5-year survival rates and calculated the Area Under the Curve (AUC) [65]. To refine the prediction of patient survival, we constructed a nomogram using clinical variables (age, race, stage, tumor stage) and risk score, and appraised the model's accuracy through the C-index and ROC curves.

Immune microenvironment assessment of HR+ BC

We utilized the CIBERSORT R package (v0.1.0) to calculate immune-related scores across twenty-two types of immune cells within HR+BC samples [66]. Next, we estimated the stromal score, immune score, ESTIMATE score, and tumor purity using relevant methods to assess the overall TME [67,68]. Additionally, the xCell package was used to determine immune cell enrichment within each sample, providing insights into specific immune cell populations. To further evaluate immunotherapeutic potential, we accessed The Cancer Imaging Archive database (https://www.cancerimagingarchive.net/) to analyze medication immune response within the samples. We also investigated the relationship between immune checkpoint gene expression and risk scores.

Mutation status analysis

We used the TCGAbiolinks and maftools R packages to obtain somatic mutation data for HR+BC from the TCGA database. Only single nucleotide variants with an allelic fraction of 10 % or higher were considered, and expression data along with tumor mutation burden (TMB) files were imported into the R package. After applying standard filters, TMB was determined by the number of nonsynonymous single nucleotide variants per megabase. In the end, GENEKEEPER was employed to handle and interpret genetic modifications, guaranteeing a thorough evaluation of pathogenicity and clinical value.

Drug sensitivity analysis

We used the ``pRRophetic'' R package (v0.5) along with the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer database (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/), the most extensive pharmacogenomics resource, to predict drug response across tumor samples. Regression analysis was conducted to estimate the half-maximal inhibitory concentration values for each drug, and both regression and prediction accuracy were evaluated using 10-fold cross-validation with the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer training set. All parameters were set to their default, including ``combat'' for batch effect removal and the mean value for duplicate gene expression.

Cell culture

MDA-MB-361 and HCC1428 cell lines were cultured in L15 and RPMI 1640 media, respectively. MDA-MB-361 cells were cultured in L15 medium supplemented with 1 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1 % penicillin/streptomycin, while HCC1428 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 10 % FBS and 1 % penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were maintained under standard conditions (37 °C, 5 % CO2, 95 % humidity) [69].

Cell transfection

MAZ expression was silenced using small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) sourced from GenePharma (Suzhou, China). Cells were cultivated in 6-well plates to 50 % confluence and transfected with siMAZ-1 (AUGCUGAGCUCGGCUUATA), siMAZ-2 (UUCAAGAACGGCUACAAUC), or the negative control siRNA (si-NC) using Lipofectamine 3000 RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blotting

Upon reaching approximately 70 % confluency, transfected cells were harvested by lysis with RIPA buffer. The lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min to remove cellular debris, and the supernatant was collected for protein analysis. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes [70]. To prevent non-specific binding, the membranes were blocked with 5 % bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1.5 h at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with a primary antibody against the target protein (e.g., Anti-MAZ), followed by a 1-h incubation with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) at room temperature. Protein bands were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate. The expression levels of the target protein were quantified using a chemiluminescence imaging system.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRt-PCR)

We extracted RNA using TRIzol reagent and then performed reverse transcription with the PrimeScript™ Kit. qRt-PCR was performed using SYBR Green premix. The primers for MAZ were: F: TCTACCACCTGAACCGACAC, R: GAGCAGTTGTAGGGCTTGTG.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was measured using the CCK-8 assay. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 5 × 103 cells per well and incubated for 24 h. Following this, 10 µL of CCK-8 reagent (A311-01, Vazyme) was added to each well, and plates were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Absorbance at 450 nm was gauged using a microplate reader (A33978, Thermo) on days 1, 2, 3, and 4 post-transfections. The mean optical density (OD) values were calculated and plotted to illustrate cell viability over time [71].

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) proliferation assay

Transfected MDA-MB-361 and HCC1428 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well, followed by incubation with 2 × EdU working solution for 2 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, the medium was removed, and the cells were gently washed twice with PBS. The cells were fixed in a 4 % paraformaldehyde solution for 30 min. After fixation, the cells were permeabilized with a glycine solution at 2 mg/mL and 0.5 % Triton X-100 for 15 min. Finally, the cells were stained with a mixture of 1 ml of 1X Apollo and 1 ml of 1X Hoechst 33,342 for 30 min at room temperature. Cell proliferation was measured with a fluorescence microscope.

Wound healing assay

Following transfection, the cells were seeded in 6-well plates and cultivated until they reached approximately 95 % confluence. A sterile 200 μL pipette tip was then employed to create linear scratches across the cell layers in each well. The wells were subsequently washed gently with PBS to remove any cellular debris. The culture medium was replaced with serum-free medium, allowing the cells to migrate. Images of the scratched areas were captured at the initial time point (0 h) and again after 48 h. The widths of the scratches were analyzed using Image-J software to quantify cell migration [72].

Transwell assay

Before beginning the assay, cells were starved in serum-free medium for 24 h. Following this preparation, a layer of matrix gel (BD Biosciences, USA) was applied to the upper chamber, where cell suspensions were then seeded. The lower chamber was infused with medium containing serum to create a chemoattractant gradient. The setup was incubated in a cell culture incubator for a period of 48 h. Following the incubation process, cells on the membrane's lower surface were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet, allowing for evaluation of their invasive ability.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using both R and Python software to process and interpret the dataset. Statistical significance was assessed with two-tailed p-values, where values under 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. For further differentiation, p-values less than 0.01 were categorized as very significant, p-values less than 0.001 as highly significant, and those below 0.0001 as extremely significant.

Results

ScRNA-seq revealed the main cell types in HR+BC

An in-depth analysis of the dataset was performed to uncover the intricate single-cell landscape of the HR+BC microenvironment. Following rigorous quality control and batch effect correction, 26,360 cells were retained for subsequent analysis. Through dimensionality reduction clustering, we categorized the 26,360 cells into twenty-two distinct clusters and identified six major cell types: epithelial cells (EPCs) (n = 20,193), T cells and NK cells (n = 3807), fibroblasts (n = 1193), myeloid cells (n = 666), endothelial cells (ECs; n = 319), B cells and plasma cells (n = 182). The UMAP plots also revealed various sample groups (BC03, BC05, BC06, BC08, BC11, BC12, BC14, BC15, BC17) and distinct cell cycle phases (G1, G2/M, S) (Fig. 1A). Then we analyzed the proportion of cell types in different groups and phases. As shown in the stacked bar graphs, EPCs accounted for a larger proportion of each group and phase, followed by fibroblasts, T cells and NK cells. Compared with G2/M and S phases, EPCs occupied a larger proportion in the G1 phase (Fig. 1B). In addition, we provided a detailed description of the expression level of top marker genes for each cell type through Fig. 1C. Afterward, we analyzed the distribution of nCount-RNA, nFeature-RNA, G2/M.score and S.score in six cell types (Fig. 1D). In order to observe the differences among these cell types more intuitively, we used violin plots to visualize the expression levels of different cell types in these terms (Fig. 1E). We also utilized UMAP plots to display the signature marker genes for six cell types (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

Single-cell analysis in HR+BC.

(A) UMAP plot represented twenty-two distinct cell clusters in HR+BC patients (upper left), while the number of cells within each cluster was shown. Another UMAP plot (lower left) visual displayed the six primary cell types after dimensionality reduction clustering. The upper right UMAP plot illustrated the distribution of groups based on the sample source, while the lower right plot showed how different phases (G1, G2/M, S) were distributed. (B) The stacked bar graphs depicted the relative proportions of each cell types across nine sample groups (upper) and three phases (lower). (C) Heatmap showcased the top five marker genes corresponding to the six principal cell types. (D) UMAP plots indicated the distribution of nCount-RNA, nFeature-RNA, G2/M.Score, and S.Score across diverse cell types. (E) Violin plots showed expression levels for nCount-RNA, nFeature-RNA, G2/M.Score, and S.Score in different cell types. (F) UMAP plots illustrated distribution of expression levels of the differential genes across six cell types.

Visualization, enrichment analysis, and biological processes of tumor cell subtypes in HR+BC

To differentiate between tumor cells and normal cells, and to study the malignancy levels and abnormal states of tumor cells, we used ECs as a reference to infer the CNV profiles of EPCs (Supplementary Fig. 1). The results pointed to the existence of abnormal chromosomal copy number fluctuations in malignant EPCs of HR+BC. We conducted an in-depth analysis of their subtypes to further elucidate the heterogeneity and biological characteristics of tumor cells. We identified eight dissimilar subtypes of tumor cells, each characterized by specific cell marker genes: C0 EVL+ tumor cells, C1 ALB+ tumor cells, C2 ERRFI1+ tumor cells, C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells, C4 CXCL17+ tumor cells, C5 UGT2B11+ tumor cells, C6 SERPINA1+ tumor cells, and C7 ANXA1+ tumor cells (Fig. 2A). To illustrate differences in cell cycle distribution among these subtypes, we used UMAP plots combined with pie charts to depict proportions and distribution of cell cycle (Fig. 2B, C). We found that other tumor cell subtypes were mainly in G1 phase, while C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells were mainly in G2/M phase and S phase. In addition, we also observed from Fig. 2D that C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells subtype had a higher proportion in G2/M and S phases. Similarly, the Ro/e score also showed that the C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells subtype preferred G2/M and S phases (Fig. 2E). Therefore, we speculated that compared with other tumor cell subtypes, the C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells subtype had stronger cell division and proliferation abilities. Fig. 2F showcased the differential expression of the top five marker genes among eight tumor cell subtypes. Then, we described the distribution of typical marker genes related to cell subtypes in tumor cells (Fig. 2G). Subsequently, Fig. 2H showed that, compared to other tumor cell subtypes, C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells exhibited the highest expression levels of G2/M.Score and S.Score, as well as elevated levels of CNVscore and nCount-RNA. This indicated a greater frequency of CNVs and a more active state of cellular proliferation compared to other subtypes, suggesting a potentially higher degree of malignancy. We studied the major biological processes for each tumor cell subtype, and the results showed that C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells were particularly enriched in mitotic cell cycle, mitotic cell cycle process, cell division, cell cycle process, chromosome organization, and nuclear division (Fig. 2I). Subsequently, we visualized the key biological functions of eight tumor cell subtypes. Compared to other tumor cell subtypes, we focused on that C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells exhibited enrichment in biological functions related to ribose phosphate biosynthesis process, chromosome separation, aerobic respiration, nucleoside triphosphate biosynthesis process, proton motive force−driven ATP synthesis and oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. 2J). Fig. 2K depicted the metabolic pathways and revealed that C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells showed significant enrichment in the metabolic pathways related to pyruvate metabolism, pyrimidine metabolism, phenylalanine metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, glutathione metabolism, and drug metabolism-other enzymes. C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells exhibited enhanced biological function and metabolic capacity in many aspects.

Fig. 2.

Visualization of tumor cell subtypes in HR+BC.

(A) The circular plot illustrated the clustering of eight tumor cell subtypes, with contour lines marking the overall boundary of their clustering. The outer axis represented the logarithmic scale of clusters per cell subtype, while the central and inner axes showed the groups and phases of each cell subtype, respectively. (B) UMAP plot demonstrated the distribution of eight tumor cell subtypes, and the pie charts depicted the proportion of different phases in each cell subtype. (C) UMAP plot illustrated the distribution of tumor cells according to different cell phases. (D) The stacked bar graph demonstrated the proportions of eight tumor cell subtypes across different phases. (E) The Ro/e score was utilized to assess the phase preference of each tumor cell subtype. (F) Bubble plot highlighted the mean expression levels of the top five distinctively expressed genes for each tumor cell subtype. The bubble size indicated the percentage of gene expression, while color indicated normalized data. (G) UMAP plots displayed the signature marker genes for eight tumor cell subtypes. (H) Violin plots showed expression levels of CNVscore, nCount-RNA, G2/M.Score, and S.Score across different tumor subtypes. (I) Bubble plot presented the results of GO-BP enrichment analysis of the major biological processes for each tumor cell subtype. (J) The key biological functions of eight tumor cell subtypes were visualized. (K) Bubble plot illustrated the different metabolic pathways enriched in each subtype of tumor cells.

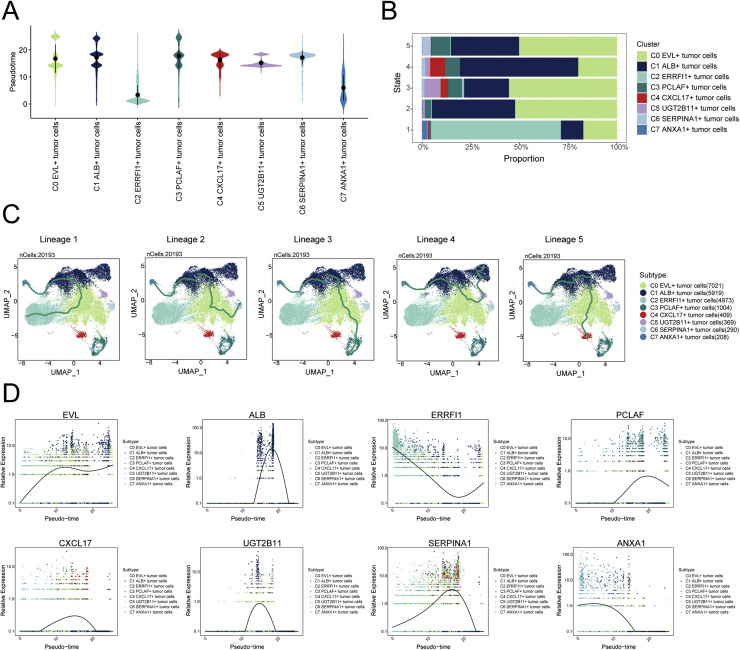

Tumor cell subtypes development and differentiation

To understand the source and development of HR+BC tumor cells, we analyzed the intricate lineage and advancement of tumor cells. The pseudotime differentiation stages of various tumor cell subtypes were shown in Fig. 3A, indicating that C2 and C7 subtypes were in early differentiation stages, while the C3 subtype was in the late differentiation stage. We respectively explored the proportion of each tumor cell subtypes in five different states (state 1, state 2, state 3, state 4, state 5), and the results showed that compared with the proportion in other states, C2 and C7 subtypes had the highest proportion in state 1, while the C3 subtype had the highest proportion in state 5 (Fig. 3B). Due to the association of the C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells with late differentiation and a high proportion in state 5, we speculated that this might indicate a poorer prognosis and greater malignant potential. We then utilized UMAP plots to separately illustrate the five cell lineage trajectories of the tumor cell subtypes (Fig. 3C). Including lineage 1: C7 → C2 → C1 → C0 → C2; lineage 2: C7 → C2 → C1 → C0 → C6; lineage 3: C7 → C2 → C1 → C0 → C3; lineage 4: C7 → C1 → C0 → C5 → C1; lineage 5: C7 → C2 → C1 → C0 → C4. Slingshot analysis revealed that five trajectories originated from C7 subtype and differentiated in C0 and C1 subtypes. What's even more remarkable was that the differences among the five trajectories mainly resided in the late stages. We believed that lineage 3 represented the differentiation lineage of tumor cells related to HR+BC, because C3 subtype was at the end of differentiation and had a high degree of malignancy. Subsequently, we analyzed the expression of dissimilar marker genes throughout the suggested temporal alterations (Fig. 3D). From the figure, it could be seen that the gene ERRFI1, a marker for the C2 subtype, and the gene ANXA1, a marker for the C7 subtype, were mainly expressed during the early stages of the developmental trajectory, while the gene PCLAF, a marker for the C3 subtype, was mainly expressed during the later stages of the developmental trajectory. This further confirmed our speculation that the malignancy of C3 subtype was higher.

Fig. 3.

Tumor cell subtype development and differentiation.

(A) Violin plot showed the differentiation stages of eight subtypes of tumor cells in pseudotime. (B) The stacked bar graph showed the proportions of tumor cell subtypes across five-time states. (C) UMAP plots highlighted Slingshot trajectories of tumor cell subtypes, with solid lines representing differentiation paths and arrows indicating the maturation direction. Each trajectory was individually displayed in UMAP. (D) The dynamic trend graphs showed the relative expression of eight marker genes over time at different differentiation stages.

CellChat analysis among all cells and visualization of the MK signaling pathway

In order to better understand cellular interactions, we sought to probe the relationships and ligand-receptor communication networks between tumor cells and other cells to identify key signaling pathways and reveal TME. We mapped intercellular communication networks among various cell types, including T cells and NK cells, fibroblasts, myeloid cells, ECs, B cells and plasma cells, and multiple tumor cell subtypes, through CellChat analysis. We then calculated the number and intensity of interactions between these cell types (Fig. 4A). The circle graphs in Fig. 4B and C quantified both the number and strength of interactions, with C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells acting as the signal source and fibroblasts as the target. These results highlighted a robust intercellular communication network between C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells and fibroblasts. We analyzed the pattern recognition of incoming (left) and outgoing (right) signals across all cell types (Fig. 4D). Notably, in tumor cells, especially C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells, both incoming and outgoing signaling were primarily driven by pattern 1, both involving CADM, SEMA4, CEACAM, and MK pathways. Based on this analysis and the visualization of all incoming and outgoing signal intensities in Fig. 4E, the signaling molecule MK stood out. MK was found to be involved in both the incoming and outgoing pathways between C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells and fibroblasts. Given its potential connection to tumor progression, we shifted our focus to MK for further investigation. Network centrality analysis of the inferred MK signaling network revealed that C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells primarily functioned as sender, mediator, and influencer. Compared to the other four cell types, fibroblasts had higher expression in the MK signaling pathway and predominantly acted as receiver, but also as sender, mediator, and influencer (Fig. 4F). In addition, Fig. 4G showed that, in the MK signaling pathway network, the association between the eight tumor cell subtypes and fibroblasts was the strongest, while there was also a certain degree of association with ECs. We compared the expression levels of vital genes within the MK signaling pathway among various tumor cell subtypes and other cell types (Fig. 4H, I) and found that MDK and NCL had a higher probability of communication in the C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells and fibroblasts. Additionally, the circle graph further confirmed that the interaction between C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells and fibroblasts could be mediated by the key ligand-receptor pair MDK-NCL within the MK signaling pathway (Fig. 4J). Therefore, our study demonstrated that the MK signaling pathway connected C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells and fibroblasts to promote tumor progression.

Fig. 4.

HR+BC cellular communication network.

(A) Circle graphs showed the number (upper) and intensity (lower) of interactions among between eight tumor cell subtypes and five cell types. (B) Circle graphs illustrated the number (upper) and intensity (lower) of interactions between C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells as the source and other cells. (C) Circle graphs displayed the number (upper) and intensity (lower) of interactions between fibroblasts as the target and other cells. (D) Heatmaps presented the pattern recognition of incoming signals of eight tumor cell subtypes and five cell types, and the incoming signal pathways of three communication patterns (left). Heatmaps presented the pattern recognition of outgoing signals for eight tumor cell subtypes and five cell types, and outgoing signaling pathways of three communication patterns (right). (E) Bar plots illustrated the relative strength of incoming and outgoing cell signaling patterns of eight tumor cell subtypes and five cell types (upper), while the heatmaps described the relative strength of various signaling pathways in the incoming and outgoing signaling patterns across eight subtypes of tumor cells and five cell types (lower). (F) Heatmap depicted centrality scores for the MK signaling pathway. (G) Hierarchical graphs detailed the interactions between C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells and other types of cells within the MK signaling pathway. (H-I) Bubble plot and violin plot displayed the expression levels of key genes of the MK signaling pathway in eight tumor cell subtypes and different cell types. (J) Circle graph showed the communication network of MDK-NCL ligand-receptor pair.

Potential regulatory mechanism of MAZ in C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells

TFs played a crucial role in regulating gene expression within cells, which was essential for maintaining cellular functions and the homeostasis of organisms. To start, we utilized the pySCENIC and connection specificity index matrix to categorize HR+BC cells into five regulatory modules (M1, M2, M3, M4, M5) according to AUCell score rule similarity (Fig. 5A). In order to better understand the dynamic characteristics of tumor cells at different phases, we studied the influence of cell cycle on the interrelationships between tumor cell subtypes. Fig. 5B showed that there were considerable variations in the correlation between each tumor cell subtype in different cell phases. The high correlation of C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells in the G2/M and S phases implied a significant similarity in biological characteristics during these cell cycle stages, as well as lower similarity with other subtypes. This suggested that C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells might have had a more specific cell cycle regulation mechanism. Therefore, we inferred that this stable expression pattern indicated a unique role of C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells in tumor growth and cell proliferation processes. We performed cluster analysis of tumor cells based on regulator activity (Fig. 5C, D). The discretization of the UMAP plot based on regulator activity was smaller, effectively minimizing interference factors and resulting in a clearer clustering and distribution of all tumor cells. By comparing the expression levels and regulon activities of TFs in each module across various tumor cell subtypes, we found that the TFs expression levels and regulon activities of C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells in the M4 module were higher compared to other modules (Fig. 5E, F). Based on the fraction of variance in each module and regulon specificity score, we ranked the TFs across subtypes and identified five key regulatory factors (E2F2+, E2F8+, E2F1+, TFDP1+, and MAZ+) in C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells (Fig. 5G, H). Finally, we successfully visualized the expression of these five key regulatory factors in C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells (Fig. 5I, J), showing significantly higher expression of MAZ in C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells compared to other tumor cell subtypes. MAZ was a key regulator of cell cycle progression and tumor growth, and it took part in the regulation of genes related to cell proliferation [73]. MAZ was highly expressed in C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells, which indicated a strong and specific regulatory relationship between MAZ and its target genes, underscoring its potential as a biomarker and pointing to new avenues for targeted therapy. However, the precise mechanism by which MAZ affected HR+BC remained unclear. Therefore, conducting in vitro functional experiments was essential to validate the role of MAZ in HR+BC.

Fig. 5.

Gene regulatory networks in C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells.

(A) Heatmap identified five regulatory modules in tumor cell subtypes based on pySCENIC regulatory rules and AUCell similarity scores. (B) Heatmap illustrated the Pearson correlation between tumor cell subtypes in different phases. (C) UMAP plot provided a visual representation of all tumor cells based on regulon activity score, colored by cell subtype. (D) UMAP plots separately showed a visual representation of each tumor cell subtype based on regulon activity score. (E) Violin plots displayed the expression levels of eight tumor cell subtypes in five regulatory modules. (F) Scatter plots illustrated the regulon activity score within each module across various tumor cell subtypes. (G) Scatter plots ranked TFs based on fraction of variance across subtypes in each module. (H) The TFs of tumor cell subtype were ranked by regulon specificity score. (I-J) The expression level and distribution of key TFs (E2F2+, E2F8+, E2F1+, TFDP1+, MAZ+) across different tumor subtypes.

In vitro experimental validation of MAZ

MAZ protein was a TF that participated in a dual capacity during transcription [74]. The dysregulated expression of the MAZ gene was tightly connected to tumorigenesis and progression, with significantly increased levels in many malignant tumors. Depletion of MAZ inhibited the growth and survival of cancer cells via inhibition of proliferation, invasion, and migration [75]. However, the exact role of MAZ in HR+BC remained unclear. To address this, we performed in vitro functional assays to evaluate the impact of MAZ on HR+BC, using two cell lines (MDA-MB-361 and HCC1428). We first knocked down MAZ, then divided the two cell lines into three groups: si-NC, si-MAZ-1, and si-MAZ-2. Following this, we evaluated the mRNA and protein expression levels before and after the knockdown. The knockdown of MAZ in these cell lines showed significant reductions in both mRNA and protein levels compared to control group (Fig. 6A). Fig. 6B showed that knockdown of MAZ in these cell lines led to a significant reduction in tumor cell viability as compared to the control group by CCK-8 assay. Additionally, both colony formation and EdU assays confirmed a marked reduction in cellular proliferation following MAZ knockdown in both cell lines (Fig. 6C, D). Furthermore, the cell wound healing and transwell assays revealed a significant decrease in the invasive and migratory abilities of tumor cells with MAZ knockdown compared to the control group (Fig. 6E–G). Collectively, these findings demonstrated that MAZ knockdown suppressed the activity, proliferation, invasion and migration of tumor cells, inhibiting tumor growth.

Fig. 6.

Validation of MAZ knockdown effects in vitro.

(A) Bar plots illustrated the relative expression levels of MAZ mRNA (left) and MAZ protein (right) across three groups: si-NC, siMAZ-1, and siMAZ-2, in MDA-MB-361 and HCC1428 cell lines. Both mRNA and protein levels showed a reduction following MAZ knockdown. (B) The CCK-8 assay indicated a marked decrease in cell viability post-MAZ knockdown, compared to the control group. (C-D) Colony formation and EdU staining assays demonstrated a significant drop in colony numbers and impaired cell proliferation following MAZ knockdown. (E) The cell wound healing assays appraised the migration ability of C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells after MAZ knockdown. (F) Transwell assays appraised invasion and migration abilities of C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells after MAZ knockdown. (G) Bar plots revealed that MAZ knockdown suppressed both invasion and migration abilities of MDA-MB-361 and HCC1428 cell lines. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Building on these findings, we managed to conduct research on the broader implications of MAZ's role in HR+BC by investigating potential prognostic factors associated with its expression.

Prognostic model identified key genes predicting HR+BC survival outcomes

To further elucidate the clinical significance of these observations, we developed a prognostic model to explore the clinical relevance of the PCLAF+/MAZ regulatory network. First, univariate Cox regression analysis identified ten genes significantly associated with prognosis (Fig. 7A). To address multicollinearity among these genes, we applied LASSO regression analysis for further refinement (Fig. 7B). We then performed a multivariate Cox regression analysis and identified eight prognostic genes (Fig. 7C). We calculated the coefficient values of these genes (Fig. 7D), and the results showed that TUBA1B, RPA3, DUT, GGCT, and LSM3 were poor prognostic factors (HR > 1 indicated poor prognosis). Next, we analyzed DEGs to further explore the differences between various scoring groups. Patients in the study cohort were stratified into high and low PCLAF+ tumor risk scores (PtRS) groups based on the optimal cutoff value of the PCLAF+ tumor cells score. The findings indicated that patients with higher scores had poorer prognoses. The curves and scatter plots showed differences in risk scores and survival outcomes between high and low PtRS groups, respectively, suggesting that the high PtRS group was associated with a poorer prognosis (Fig. 7E). Subsequently, Fig. 7F showed the differential expression of the eight prognostic genes between the two groups. Kaplan-Meier survival curves in Fig. 7G also confirmed the poor survival outcome of the high PtRS group (P < 0.0001). In addition, ROC curves used AUC values to assess the sensitivity and specificity of survival outcomes at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years, underscoring the predictive power of the model (Fig. 7H). Finally, we investigated the survival differences among patients grouped by the expression levels of eight prognostic genes (Fig. 7I). Our analysis further showed that in the high PtRS group, TUBA1B, RPA3, LSM3, and GGCT were risk factors associated with poorer prognosis, while TFF1, PTMA, and MZT2A were protective factors linked to better prognosis. This model highlighted the potential for these genes to serve as prognostic biomarkers.

Fig. 7.

Prognostic model construction for C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells.

(A) Forest plot of univariate Cox regression analysis displayed risk factors (HR > 1) and protective factors (HR < 1). (B) LASSO regression analysis identified prognostic genes. The optimal parameter (lambda) was selected through ten-fold cross-validation (lower), and the LASSO coefficient curve was generated based on the optimal lambda (upper). (C) Forest plot illustrated that eight prognostic genes were identified by multivariate Cox regression analysis. (D) Bar plot showed coefficient values for the genes used in the model construction. (E) Risk curve displayed the scores of high and low PtRS groups (upper), with a scatter plot showing alive/death events in both groups over time (lower). The blue color indicated the low PtRS group, whereas the red color represented the high PtRS group. (F) Heatmap demonstrated differential expression of eight prognostic genes used in the model, with color scale based on normalized data. (G) Kaplan-Meier curves showed survival differences between the high and low PtRS groups. (H) ROC curves assessed the sensitivity and specificity of survival outcomes using AUC values at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years. (I) OS curves showed the survival differences grouped by the expression levels of eight prognostic genes.

PCLAF+ tumor cells risk scores and prognostic genes predicted patient survival

To verify the independent and predictive value of PCLAF+ tumor cells risk score as a prognostic factor for patient survival, we performed multivariable Cox regression analysis, including risk score and clinical factors such as age, race, stage, and tumor stages (T, M, N). The analysis showed that high PtRS was an independent predictor of poor prognosis in patients (P < 0.001, HR > 1) (Fig. 8A). To more accurately predict patient survival, we developed a nomogram based on age, race, stage, tumor clinical stages (T, M, N), and risk score. We used the nomogram to predict OS for 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years, and Fig. 8B showed that there was a significant difference in the PtRS groups. In addition, we used the C index and ROC curve to confirm the accuracy of the model, obtaining AUC values of 0.729 (1 year), 0.668 (3 years), and 0.641 (5 years), thus further confirming our prediction (Fig. 8C, D). To gain deeper insight into the impact of various genes on prognosis, we analyzed the correlations among eight prognostic genes, OS, risk, and their expression levels in the high and low PtRS groups (Fig. 8E–H). TUBA1B, RPA3, LSM3, GGCT, and DUT were significantly positively correlated with the risk scores and showed higher expression in the high PtRS group. Furthermore, TUBA1B, RPA3, LSM3, and DUT were significantly negatively correlated with OS, indicating that the high expression of these genes might be associated with poorer prognosis. In contrast, TFF1, PTMA, and MZT2A were significantly negatively correlated with the risk scores and showed higher expression in the low PtRS group. At the same time, TFF1 and PTMA were significantly positively correlated with OS, suggesting that the high expression of these genes might be associated with better prognosis. Furthermore, the size of the correlation coefficient provided an early clue to the importance these genes might play in patient outcomes. These findings were crucial for identifying potential biomarkers that could be used for patient stratification and targeted therapies based on gene expression profiles.

Fig. 8.

C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells risk score model.

(A) Forest plot presented multivariate Cox regression results, incorporating risk scores with clinical factors such as age, race, stage and tumor stage (T, M and N). (B) Nomogram predicted OS based on factors like age, race, stage and tumor stage (T, M, and N) at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years. ***P < 0.001. (C) Violin plot displayed the C-index for cross-validation at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years. (D) ROC curves showed the nomogram AUC for 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years. (E) Heatmap combined with scatter plots demonstrated the correlations among prognostic genes, risk, and OS using the correlation coefficient. (F) Scatter plots visualized correlations between prognostic genes and risk. (G) Ridge and box plots were used to compare gene expression differences of prognostic genes between high and low PtRS groups. The high and low peaks in the ridge plots indicated the patient density corresponding to different levels of gene expression. (H) Scatter plots visualized correlations between prognostic genes and OS.

The relationship between immune cell infiltration, mutation status, treatment sensitivity, and immune checkpoint-related genes with prognostic outcomes

We comprehensively assessed the infiltration levels of twenty-two immune cell types in HR+BC patients from the TCGA database across high and low PtRS groups. The comparison of the proportions for immune cells between the two groups was presented in Fig. 9A. In particular, Macrophages M2, M1, M0, T cells CD4 memory activated, and NK cells resting were higher in the high PtRS groups. In contrast, T cells regulatory, T cells CD8, and B cells naive were higher in the low PtRS group (Fig. 9B). Subsequent analyses explored the correlations among immune cells, risk scores, OS, risk, and prognostic genes (Fig. 9C, D). The findings indicated that the prognostic model was positively correlated with T cells CD4 memory activated, Macrophage M2, and Neutrophils, suggesting these cells might contribute to tumor progression or form an immunosuppressive microenvironment. Conversely, it was negatively correlated with T cells regulatory, B cells naive, T cells CD8, and NK cells activated, which might suggest potential immune suppression or evasion mechanisms driven by these cell types. We also analyzed gene mutations, CNVs, and TMB in HR+BC patients to investigate the relationship between gene variations and tumor progression or immune evasion. The waterfall plot showed the mutation of the top 30 high mutation frequency genes in 991 samples (Fig. 9E), where missense mutation was the dominant mutation type, and the mutation frequencies of TP53, PIK3CA, and TTN were relatively high. Fig. 9F demonstrated that CNV-loss in DUT and PTMA was more frequent compared to other prognostic genes. The high PtRS group had a higher TMB, while the low PtRS group had higher immune score, ESTIMAT score, and stromal score (Fig. 9G, H). Tumor purity was higher in the high PtRS group (Fig. 9I), often associated with more aggressive tumor behavior and poor immune infiltration. Fig. 9J revealed significant differences in the expression of prognostic genes and immune cell infiltration between the two groups. The upregulation of prognostic genes and infiltration of specific immune cells in the high PtRS group might lead to a poor prognosis. However, low PtRS group gene expression and immune microenvironment showed more favorable characteristics for anti-tumor response. Moreover, we compared the responsiveness of two immunotherapeutic drugs, CTLA4 and PD1, in the two groups (Fig. 9K), and the results showed that the sensitivity level was generally lower in the high PtRS group, especially in the CTLA4-neg/PD1-neg and CTLA4-pos/PD1-pos groups. Lastly, the analysis of the relationship between prognostic genes and immune checkpoint-related genes (Fig. 9L) showed that TUBA1B and PTMA were positively correlated with most immune checkpoint-related genes, while RPA3, LSM3, GGCT, TFF1, and MZT2A were negatively correlated. The expression levels of immune checkpoint-related genes TNFRSF14, TNFRSF18, CD86, and C10orf54 were elevated in both the high and low PtRS groups (Fig. 9M). These findings underscored PtRS as an independent predictor of patient outcomes and highlight potential therapeutic strategies targeting immune checkpoints.

Fig. 9.

Comparative analysis of immune infiltration across different risk groups.

(A) The proportions of infiltrating immune cell types across risk score groups were evaluated using CIBERSOFT. (B) Box plot compared thirteen immune cell types between high and low PtRS groups. (C) Lollipop chart showed the correlations between immune cells and risk scores. (D) Heatmap presented the correlations among eight prognostic genes, risk, OS, and twenty-two immune cell types. (E) The waterfall plot displayed the mutation status of the top thirty genes with the highest mutation frequency across the samples. The upper bar plot illustrated the mutation load for each sample, while the histogram on the right summarized the mutation status for each gene by mutation type. (F) Bar plot showed the gains and losses of CNVs across eight prognostic genes. (G) Tumor mutation load was compared between high and low PtRS groups. (H) Stromal score, immune score, and ESTIMAT score were calculated for high and low PtRS groups. (I) Tumor purity for the high and low PtRS groups was calculated. (J) Heatmap demonstrated differences in prognostic gene expression, risk score, stromal score, immune score, ESTIMAT score, tumor purity, microenvironment score and immune cell infiltration between high and low PtRS groups. (K) Violin combined with box plots compared drug sensitivity to CTLA4 and PD1 immunotherapeutic agents between high and low PtRS groups. (L) Bubble plot presented correlations among prognostic genes, risk, OS, and immune checkpoint-related genes. (M) Box plot illustrated the expression levels of immune checkpoint-related genes in the high and low PtRS groups. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

Enrichment analysis and drug sensitivity in prognostic contexts

We analyzed the DEGs in the high and low PtRS groups to identify the critical roles of these genes in prognosis or the characteristics of both groups. A volcano plot displayed the upregulation and downregulation of differential genes (Fig. 10A). Fig. 10B illustrated the expression of DEGs in the high and low PtRS groups. GO analysis results in Fig. 10C suggested that DEGs were enriched in multiple biological processes, including epithelial structure maintenance, tissue homeostasis, anatomical structure homeostasis and histone deacetylase binding, which might contribute significantly to maintain tissue integrity and control tissue stability, thereby influencing tumor initiation and progression. In addition, differential genes were analyzed by GSEA (Fig. 10D). Upregulated genes were enriched in sister chromatid separation, chromosome separation, nuclear chromosome separation and dna replication initiation. This reflected the enhancement of tumor cell division and proliferation. Down-regulated genes were mainly concentrated in negative regulation of megakaryocyte differentiation, B cell receptor signaling pathway, skeletal muscle contraction and actin myosin filament sliding. It indicated that the immune response was reduced, which may lead to immune evasion and deterioration of prognosis. The results of GSVA enrichment analysis showed pronounced differences in functional characteristics and pathway enrichment of tumor cell subtypes across high and low PtRS groups (Fig. 10E). Lastly, we identified several drugs with potential clinical efficacy targeting prognostic genes (Fig. 10F), including ABT.263, ATRA, BAY.61.3606, BIBW2992, CMK, Cyclopamine, Etoposide, IPA.3, and Z.LLNle.CHO, through drug sensitivity analysis. However, we also found Bicalutamide to be effective in the low PtRS group. These findings helped identify the potential therapeutic effects of multiple drugs in HR+BC patients with different risk profiles, providing a potential basis for personalized treatment.

Fig. 10.

Enrichment analysis and drug sensitivity.

(A) The volcano plot displayed the upregulated and downregulated DEGs between high and low PtRS groups. (B) Heatmap of DEGs displayed gene expression patterns between high and low PtRS groups, with each row corresponding to a gene. (C) Bar plot depicted the results from GO enrichment analysis of DEGs, showing key biological processes. (D) The results of GSEA enrichment analysis of DEGs showed upregulated and downregulated genes enriched in the main biological functions. (E) The results of GSVA enrichment analysis for differential gene sets in the high and low PtRS groups were presented. (F) Violin plots evaluated drug sensitivity in tumor cells from high and low PtRS groups. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

HR+BC was the most common subtype of BC [76], accounting for approximately 60–75 % of BC patients, and the 5-year survival rate for most ER/PR subtypes of stage IV remained well below 20 % [77,78]. HR+BC was driven by the expression of ER and/or PR [79], which made it highly responsive to endocrine therapies in its early stages. However, despite the initial responsiveness, many patients eventually developed resistance to these therapies, leading to disease progression. This issue was particularly critical in metastatic HR+BC [6], underscoring the need for more effective treatment strategies. Current therapeutic options such as CDK4/6 inhibitors had shown promise, but resistance and tumor heterogeneity continued to present significant challenges [80].

Endocrine resistance, which could occur either de novo or be acquired after initial sensitivity to treatment, was a major obstacle in the effective management of HR+BC [81]. Several molecular mechanisms contributed to this resistance, including mutations in the ER, deregulation of plexin complex, activation of alternative signaling pathways such as the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, and changes in the TME [15,[82], [83], [84], [85], [86]]. Multiple cell types within TME might interact with tumor cells to promote tumor cell survival, growth, and immune escape. Understanding the interplay between the tumor and its microenvironment was key to developing more effective therapeutic approaches that could overcome resistance and improve patient outcomes.

One of the significant advancements in cancer research had been the use of scRNA-seq to dissect tumor heterogeneity and the TME at the cellular level. This technology had allowed for the identification of distinct tumor cell subtypes within HR+BC, each with unique molecular characteristics. In this study, eight tumor subtypes were identified, among which the C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells subtype was found to exhibit particularly high proliferative activity and malignancy potential. C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells were particularly enriched in processes related to mitotic cell cycle, mitotic cell cycle process, cell division, cell cycle process, chromosome organization, and nuclear division. In addition, these cells exhibited significant enrichment in biological functions associated with ribose phosphate biosynthesis process, chromosome separation, aerobic respiration, nucleoside triphosphate biosynthesis process, proton motive force−driven ATP synthesis and oxidative phosphorylation. Furthermore, C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells showed substantial enrichment in the metabolic pathways related to pyruvate metabolism, pyrimidine metabolism, phenylalanine metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, glutathione metabolism, and drug metabolism-other enzymes, which were crucial for cell growth and survival [87,88]. These cells were also predominantly active in the G2/M and S phases of the cell cycle, indicating that they were more prone to division and exhibited a higher degree of proliferation compared to other subtypes [89,90].

We further explored some potential relationships between the C3 PCLAF+ tumor cell subtype and other tumor cell subtypes and found that this interplay between the subtypes, particularly in metabolic and cell cycle pathways, might have contributed to the aggressive phenotype of the C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells and their potential to evade therapeutic interventions. C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells and C0 EVL+ tumor cells both exhibited enrichment in metabolic pathways, such as pyruvate and phenylalanine metabolism, suggesting a potential synergy in energy production and cellular maintenance [91]. C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells and C1 ALB+ tumor cells might interact due to their shared involvement in mitochondrial functions, with C1 ALB+ tumor cells focusing on ATP synthesis and aerobic respiration, while C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells were involved in oxidative phosphorylation and ATP production through proton motive force-driven mechanisms. This overlap suggested that both subtypes might cooperated in maintaining energy production, with C1 ALB+ tumor cells providing mitochondrial functions and C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells utilizing these pathways to support their high proliferative activity [92]. C2 ERRFI1+ tumor cells, enriched in actin filament organization, glycolysis, and gluconeogenesis, might work in conjunction with C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells to support rapid cell division and motility [93]. C4 CXCL17+ tumor cells' enrichment in protein folding, response to unfolded protein, oxidative phosphorylation, and riboflavin metabolism suggested a role in cellular stress response [94], which could complement C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells' high proliferative activity and cell cycle progression by helping maintain cellular integrity under conditions of rapid division. C5 UGT2B11+ tumor cells' involvement in drug metabolism and detoxification processes might help maintain cellular homeostasis and protect C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells from metabolic stress during rapid proliferation [95]. C6 SERPINA1+ tumor cells, focusing on purine and nucleoside triphosphate biosynthesis, might support the rapid growth and division of C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells [96,97]. Lastly, the heightened proliferative activity of C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells might rely on the support from C7 ANXA1+ tumor cells' ribosome biogenesis to sustain high rates of cell division [98]. These potential relationships reflected the dynamic and interconnected nature of the TME, with different subtypes potentially supporting each other in metabolic and cell cycle regulation.

The discovery of increased chromosomal CNV in C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells was another critical finding of this study. Genomic instability, reflected by CNV, was a hallmark of cancer progression and was often associated with more aggressive tumor behavior [99,100]. Slingshot and pseudotime analyses further revealed that C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells were found in the later stages of differentiation, correlating with advanced disease and a poorer prognosis [101]. These cells were predominantly located in ``state 5′' of differentiation, indicating that they might represent a terminally differentiated, highly malignant population that drove HR+BC progression. Given the aggressive nature of this subtype, targeting C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells could provide a therapeutic avenue for controlling disease progression, particularly in patients with advanced HR+BC. However, while Slingshot analysis provided valuable insights into HR+BC differentiation, it oversimplified complex pathways, omitted TME interactions, and was affected by data quality and inter-sample variability, which might limit the accuracy and generalizability of the findings.

TME played a pivotal role in supporting the survival and growth of tumor cells, particularly through interactions with stromal components such as CAFs. CAFs were known to promote tumor progression by remodeling the extracellular matrix, facilitating angiogenesis, and aiding immune evasion [102,103]. In this study, the MK signaling pathway was identified as a key mediator of communication between C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells and CAFs to promote tumor progression. It had been documented that this was related to several mechanisms involving CAFs and lactate signaling pathways that activated and maintained the TME [104]. In the MK signaling pathway network, the association between the eight tumor cell subtypes and fibroblasts was the strongest, while there was also a certain degree of association between tumor cells and ECs. Therefore, we hypothesized that fibroblasts played a key role in responding to tumor-derived signals, potentially participating in tumor progression or changes in the TME. Furthermore, tumor cells might influence the endothelial system, promoting tumor angiogenesis. The MK pathway, involving the ligand MDK and its receptor NCL, was found to be highly active in these interactions, promoting tumor growth by enhancing the pro-tumorigenic activity of CAFs. The presence of active MK signaling between C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells and CAFs suggested that targeting this pathway could disrupt the supportive role of the TME and inhibit tumor growth. This highlighted the potential of therapies aimed at both the tumor cells and their microenvironment, rather than focusing solely on the tumor itself.

Another key finding of this study was the identification of TFs that regulated the proliferation and survival of HR+BC cells, particularly within the C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells subtype. MAZ (myc associated zinc finger protein), a TF involved in transcription initiation and termination, was highly expressed in many malignant tumors and was found to play a key role in promoting cell cycle progression and proliferation of cancer cells [[25], [26], [27]]. Overexpression of MAZ had been shown to upregulate SIPL1 expression at the transcriptional level in triple negative breast cancer cells, thereby promoting tumor progression and predicting poor survival [105]. Compared to normal breast EPCs, both PPARγ1 and MAZ were highly expressed in MCF-7 BC cells, with the tumor-specific expression of PPARγ1 being MAZ-dependent, and decreased expression of PPARγ1 leaded to reduced proliferation of MCF-7 BC cells [106]. Research had also shown that MAZ expression in BC tissues was significantly higher than in adjacent normal tissues, and patients with high MAZ expression had a significantly lower survival rate than those with low expression [107]. Functional experiments showed that knockdown of MAZ in HR+BC cell lines significantly reduced cell viability, proliferation, and migration, underscoring its role in promoting tumor growth and metastasis. Given its importance in regulating key genes involved in cell survival and division, MAZ represented a promising therapeutic target for HR+BC, particularly for tumors with a high proportion of C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells. This finding warranted further investigation into whether any specific candidate drugs could selectively target MAZ without causing significant off-target effects. Considering the pivotal role of MAZ in driving tumor advancement and its relevance to clinical outcomes, selective inhibition of MAZ could potentially halt or even reverse the malignant behavior of tumor cells, particularly those enriched in C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells subtype. However, it was crucial to evaluate the potential side effects of MAZ-targeting therapies, as MAZ might also play a role in normal cellular functions. Comprehensive studies were required to assess the safety and clinical value of such treatments, along with the identification of possible biomarkers to predict patient response. The development of MAZ inhibitors or modulators could offer a novel approach for the treatment of HR+BC, especially for patients with tumors characterized by high levels of MAZ expression.

In addition to identifying potential therapeutic targets, the study also developed a prognostic model based on the expression profiles of the different tumor subtypes. Several genes, including TUBA1B, RPA3, LSM3, GGCT, and DUT, were found to be associated with poorer survival outcomes, particularly in patients with high PtRS. Compared to the low PtRS group, Macrophages M2, M1, and M0 were significantly infiltrated in the high PtRS group, with T cells CD4 memory activated and NK cells resting also showing a certain degree of infiltration. We then analyzed the correlation between risk scores and immune cells and found a significant positive correlation between risk scores and T cells CD4 memory activated, Macrophages M2, and Neutrophils. Therefore, we hypothesized that the significant association between high PtRS and poor survival outcomes in HR+BC was closely related to TME. Macrophages M2 promoted tumor progression by remodeling the extracellular matrix, enhancing immune suppression, and facilitating angiogenesis [21,108]. At the same time, Macrophages M1, which were usually pro-inflammatory and anti-tumor, can transitioned into immune-suppressive roles in the TME, thanks to the lactic acid secreted by tumor cells to promote the activation of CAFs and M2 polarization in Macrophages [104]. Similarly, Macrophages in the transitional M0 state were polarized toward Macrophage M2, which might be supported by the metabolism of pyruvate enriched by lactic acid through the C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells subtype, further driving immunosuppression [109]. We speculated that this transition might promote tumor survival by increasing local inflammation and interacting with T cells, NK cells, and Neutrophils, ultimately leading to immune evasion [110,111]. In contrast, patients in the low PtRS group showed higher levels of immune-activating cells, such as T cells CD8 and B cells naïve, which were associated with better survival outcomes and stronger anti-tumor immune responses [112,113]. Compared to the high PtRS group, the low PtRS group also showed higher levels of immune-suppressive T cells regulatory, but at a relatively smaller proportion. Additionally, we found that the high PtRS group exhibited a higher TMB score, while the low PtRS group had higher immune score, ESTIMAT score and stromal score, suggesting greater immune cell infiltration and possibly better patient prognosis. This also indicated that stromal cells had a weaker impact on the tumor compared to immune cells, especially in terms of tumor suppression [114]. These discoveries pointed to the essential role of the immune microenvironment in determining prognosis for HR+BC patients. Targeting immune-suppressive elements in the TME, such as Macrophages M2, and enhancing the activity of immune-activating cells could provide new therapeutic strategies for improving survival in advanced HR+BC patients. Immune-modulating therapies, especially those aimed at restoring anti-tumor immunity, could be particularly beneficial for patients who had developed resistance to traditional endocrine therapies [115].

Furthermore, the immune escape mechanisms observed in the C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells subtype deserved further exploration. C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells were characterized by high proliferative activity and chromosomal instability [116], which might interact with the immune system in ways that promoted disease progression and metastasis. A more comprehensive analysis of the immune microenvironment, particularly how interactions with CAFs and other stromal components supported the survival and immune escape of C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells, was crucial. Specifically, the MK signaling pathway had been identified as key in the interaction between C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells and CAFs, and it might represent a potential target to disrupt tumor-supportive signaling within the TME. Future research could investigate how disrupting MK signaling impacted immune cell recruitment and function within the TME, potentially reversing immune suppression and sensitizing C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells to existing therapies. These insights were essential for developing combination therapies that directly targeted tumor cells while modulating the immune microenvironment to enhance anti-tumor responses. Addressing immune escape and overcoming resistance in aggressive subtypes like C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells remained a significant challenge. One potential approach was the development of combination therapies. For example, combining CDK4/6 inhibitors with immune checkpoint inhibitors might help overcome the immunosuppressive effects of the TME, reactivating immune surveillance while simultaneously targeting the proliferative pathways driving tumor growth. Additionally, targeting specific TFs such as MAZ, which regulated both tumor proliferation and immune evasion, could be an effective strategy to reduce tumor growth and enhance immune response. Since MAZ overexpression was associated with poor prognosis and resistance to endocrine therapy, selective inhibition of MAZ in HR+BC, particularly in C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells subtype, could potentially reduce tumor progression and reverse resistance to treatment. Furthermore, combination therapies targeting both tumor cells and immune modulators, such as inhibitors of Macrophages M2 activity or activators of T cells CD8, might improve overall treatment efficacy by overcoming the immune escape mechanisms used by tumors.

Finally, the study also conducted drug sensitivity analyses to identify therapeutic agents that might be effective against different HR+BC subtypes. Bicalutamide, an androgen receptor inhibitor, was found to be effective in patients with the low PtRS group, while drugs such as ABT-263 and Etoposide were identified as potential treatments for high PtRS group with more aggressive tumor subtypes. These findings suggested that personalized treatment approaches, based on the molecular and cellular characteristics of the tumor, could lead to better outcomes for HR+BC patients. By targeting the unique vulnerabilities of each tumor subtype, more effective therapies could be developed that were tailored to the specific needs of individual patients.

However, more detailed clinical data were needed to better understand how to implement these personalized treatments in clinical practice. For instance, understanding how to combine immune checkpoint blockade with endocrine therapy or CDK4/6 inhibitors in patients with high-risk C3 PCLAF+ tumor cells subtype was critical. Furthermore, a better understanding of biomarkers that predicted response to these combined therapies could help tailor treatment plans [117,118], improving overall treatment efficacy. Before these combination approaches were widely recommended in clinical settings, it was essential to evaluate their safety, tolerability, and effectiveness.