Abstract

As a vulnerable population, immigrants can be disproportionately affected by disasters. Because of their legal and migratory status, immigrants may have different challenges, needs, and possibilities when facing a disaster. Yet, within disaster studies, immigrants are rarely studied alone. Instead, they are often considered part of the large heterogeneous group of racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. This racial classification points to a gap in the literature and in our understanding of how disadvantaged groups may cope with disasters. To address this gap, the current study hypothesizes that: (1) Immigrants have unique experiences and disaster impacts compared to the broader aggregated category of racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S. and (2) There are variations in disaster experiences and impacts across different types of immigrant subgroups beyond refugees. To explore these hypotheses, a study of the literature across six databases from 2018 to 2023was conducted. The review identified a total of 17 articles discussing immigrant experiences during disasters. Major cross-cutting themes on immigrant disaster experiences include fear of deportation, restrictive immigration status, excessive economic burden and labor exploitation, employment rigidity, adverse health outcomes, limited informational resources and limited social capital, selective disaster relief measures, and infrastructural challenges as regards to housing and transportation. Many of the themes identified are unique to immigrants, such as the fear of deportation, restrictive immigration status and visa policies, and selective disaster relief measures.

Keywords: Systematic literature review, Disasters, Immigrants, Refugees

Introduction

Socially vulnerable populations encompass a wide range of demographic groups. This includes low-income households, single-parent families, elderly residents, individuals with disabilities or pre-existing health issues, and racial and ethnic minorities who often face social marginalization or discrimination [1–5]. Disaster vulnerability among these populations often arises from complex interactions between historical, socioeconomic, health, demographic, and geographic factors that create disparities between different societal groups [1]. These dynamics increase susceptibility to harm from disasters, crises, and stressors [1, 5–10]. A growing vulnerable population is that composed by immigrants. Comprising over 46.1 million people (about twice the population of New York) in the US, immigrants make up 13.9% of the total population according to the 2022 American Community Survey.

An immigrant is defined by the United States (U.S.) Department of Homeland Security as “[a]ny person lawfully in the U.S. who is not a U.S. citizen, U.S. national, or person admitted under a nonimmigrant category”. Yet, refugees and other classes of migrants are differentiated in current legislation, a fact that contrasts with broader common-sense interpretations that are popular in the media and everyday interactions. While the formal definition of immigrant often excludes those who are foreign-born noncitizens and who unauthorizedly reside in the U.S., known as undocumented immigrants, both terms may be and are often conflated. In this article, we use immigrants to refer to the broader class of foreign-born individuals who have made the U.S. their permanent home.

In addition to challenges related to their legality and their distance from their home country local networks, immigrants face several disadvantages that undermine their capacity to respond to disasters. Because immigrants intersect with multiple vulnerable groups, their susceptibility to experiencing negative effects from events such as hurricanes or floods can be amplified [11, 12]. For example, migrant women faced compounded vulnerabilities distinctly shaped by both of their identities as migrants and women. Additional gender-based inequalities surrounding domestic labor burden and gender-based violence risk exacerbated by containment and pandemic management policies increased their vulnerability [13].

Immigrant communities face growing threats from the escalating frequency and severity of disasters along the coast. Historically drawn to coastal states such as California, Texas, New York, New Jersey, and Florida [14–17] by economic opportunities, social networks, transportation access, and more affordable housing, these immigrant populations now find themselves increasingly vulnerable to the rising risks of flooding, heat waves, and extreme temperatures [18].

However, very little is known about the strategies and challenges that these groups are facing when adapting or responding to climate-related threats. Previous disaster research studies have often examined immigrants within the larger heterogeneous group of racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S. or exclusively focused on refugees. The distinct experiences and concerns of immigrant subgroups are often overlooked due to the conflation of categories, neglecting the understanding of how support can be built through both local and international networks [19–21]. Immigrants face unique needs and barriers compared to native-born racial and ethnic minorities [22, 23], and may also exhibit different coping strategies, which is crucial information for planning recovery and mitigation policies.

Furthermore, research on the impacts of disasters on temporary migrants with nonimmigrant visas or lawful permanent residents (LPRs) who are not naturalized citizens is limited. This paper aims to highlight the experiences of immigrants during disasters and identify potential knowledge gaps through a systematic literature review.

Background

Disasters are recognized as disruptive events that severely impact societies and their normal functioning [24–27], affecting social structures, relationships, and contexts [28, 29]. Disasters are also multifaceted, involving physical conditions, social constructions, and organizational dynamics, and can originate from natural hazards or be human induced [30].

Weather and climate-related disasters have increased in frequency and intensity in the past decades due to the interaction of global climate change and anthropogenic pressures such as population growth, agricultural intensification, and urban development [31, 32]. The change in what was once seen as purely natural events has resulted, in turn, in increased levels of exposure and vulnerability of the world’s most vulnerable populations [33]. For instance, in 2021 alone, over 16 million people globally were displaced by weather-related disasters [34]. Climate is now considered a key driver of global migration and population mobility, with projections suggesting the internal displacement of 216 million people in six world regions by 2050 [35, 36].

In the U.S., the umbrella term “immigrants” commonly refers to many subpopulations with different legal statuses and periods of residence. The formal definition of immigrant adopted by the government and immigration authorities, however, clearly distinguishes between these groups for legal, administrative, and fiscal purposes. Immigrants encompass naturalized citizens; foreign-born individuals who have fulfilled various requirements to become naturalized as U.S. citizens [37–39]. In fiscal year 2022, nearly 970,000 individuals became naturalized U.S. citizens, representing a 20% increase from 2021 and the highest number since 2008 the majority of the immigrant population in the U.S. annually.

Lawful permanent residents (LPRs) also known as "green card" holders, are considered immigrants for legislative and administrative purposes. This population refers to non-U.S. citizens who have been granted legal permanent residency status and authorization to live and work in the U.S. There are several pathways to obtaining LPR status, including family reunification, employment-based preferences, refugee or asylee status, the diversity visa lottery program, or other humanitarian programs [40]. However, family reunification accounts for most new lawful permanent residents (LPRs) admitted annually [41].

Temporary migrants, known as visitors, refer to foreign nationals who have been granted time-limited admission to the U.S. for a specific purpose, such as work, study, or tourism. Awarded with a visa that may exclude intent to migrate, major authorized categories include tourists, business visitors, students, specialized workers, cultural exchange visitors, and agricultural laborers. In fiscal year 2019, there were 81.6 million non-immigrant I-94 admissions, but this number plummeted to 37.2 million in 2020 and 13.6 million in 2021 due to pandemic restrictions [42–44].

Migrants with refugee or asylum status have unique considerations. According to the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), a refugee is an individual who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin or nationality due to persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution based on their race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. In contrast, an asylee meets the definition of a refugee but is already present in the U.S. or seeking admission at a port of entry while their refugee claim is still pending [45]. As of 2021, the U.S. hosted approximately 340,000 refugees and have over 1.3 million pending asylum seekers [46].

Unauthorized migrants, also known as undocumented immigrants, are foreign-born noncitizens who either entered the U.S. without inspection or have overstayed their visas after entering legally as a temporary migrant [47]. The unauthorized population rose to 11.35 million in January 2022, up by 1.13 million from January 2021 [48]. Although unauthorized migrants are the focal point of many policies, there is evidence to suggest that they are not the majority of the immigrant population in the U.S. annually. There were 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S. in 2011, accounting for 23% of the total immigrant population in the country [47].

Although immigrants face social vulnerability during disasters, it is inaccurate to characterize all immigrants in the U.S. as universally disproportionately impacted [49, 50]. This is true across all socially vulnerable populations in the U.S. [1]. For instance, some individuals have high levels of human, social, and economic capital that enable greater integration into the receiving countries [42, 51]. Therefore, immigrants like other marginalized populations with strong educational backgrounds, English language skills, financial assets, and professional networks face fewer barriers and vulnerabilities [52–54]. Still, marginalization may occur based on discrimination, racism, and xenophobia. In the US, immigrants from historically marginalized populations comprise 87.2% of the foreign-born population, such as those from Latin America, Asia, and Africa. Those from Europe, Northern America, and Oceania constitute 12.8% of the total immigrant population. This indicates that racial and ethnic minority immigrants may still face disproportionate risks and barriers [55, 56].

Addressing barriers that increase social vulnerability for immigrants is crucial to ensure equitable access before, during, and after disasters [7, 57]. For instance, migrants fleeing humanitarian crises, violence, instability, poverty, and climate change impacts in their home countries also face heightened risks and barriers when displaced, including trauma, lack of local community ties, language barriers, precarious legal status, lack of resources, and reliance on overwhelmed social services [58–61].

The social and political ecology theory of disasters focuses on exploring the interactions within social systems that may enhance or mitigate disaster risks, including the role of power differences and inequality and how disruptions to social structures can affect disaster recovery at the community and household levels [62–67]. Resource scarcity following a disaster can create competition in accessing recovery and emergency support, especially among socially vulnerable groups lacking robust social networks and financial, medical, material, educational, and informational assets [5, 68, 69]. Competition can lead to an uneven recovery process where minority and immigrant subpopulations can end up on the losing side of the equation.

Experiencing greater risks of physical harm and property destruction due to housing and financial precarity, these groups are often left disempowered and incapable of receiving aid [64]. Research shows the existence of recovery disparities across areas like housing, infrastructure, technology, and employment, consistent with the theory’s premise that social inequalities shape competition for scarce post-disaster resources [70, 71]. Furthermore, findings underscore that social networks and resource access mediate impacts to aid leading to uneven outcomes across households and social groups [65, 72–74].

This article attempts to survey and explore individual experiences of disaster among immigrants as found in the published literature. The following are the hypotheses explored:

H1: Immigrants’ experiences related to and impacts from disaster can differ from those of the broader aggregated category of racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S.

H2: Disaster experiences and impacts can vary across different types of immigrant subgroups.

These hypotheses contend that to fully understand the complexity of immigrant disaster experiences, research must examine this population separately from other ethnic minority groups while accounting for within-group differences across diverse immigration related factors and demographics [75–78].

Methods

The study employed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria to conduct the review [79]. Systematic reviews often highlight a need for knowledge of widely accepted principles to make them replicable and scientifically accurate [79–81]. The PRISMA standard, peer-accepted technique strictly adhered to in this paper included a checklist of guidelines to help ensure the quality and replicability of the revision process [79, 82]. A review protocol was created, outlining the criteria for selecting articles, the search strategy, the data extraction process, and the data analysis procedure.

Data Sources and Search Strategies

A structured literature search was performed in November 2023 across six electronic databases. For all databases, the exact following keywords were used: (immigrants OR refugees) AND (disasters OR natural disasters") AND ("United States"). The search was limited to articles published between the periods 2018 and 2023. The 2018–2023 timeframe captures a period of significantly increased frequency and financial impact of disasters in the U.S., including 28-billion- dollar weather and climate events in 2023 alone [83, 84], along with the COVID -19 pandemic [85]. Also, 2018 marked the beginning of a critical recovery period following the devastating impacts of Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria in 2017. Hurricane Harvey in particular, stands out as the second costliest hurricane in U.S. history [86, 87].

This period also saw substantial shifts in immigration policy, such as the Trump administration’s “Zero Tolerance” approach, expansion of the "public charge" rule, attempts to terminate DACA, and travel bans, as well as the Biden administration’s reversal of many of these policies and proposed reforms, including ending the "Remain in Mexico" policy and advocating for a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants [88–90]. These policy changes likely heightened immigrant vulnerability. A total of 392 research articles were obtained and processed according to the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion Criteria

Peer-reviewed research articles in English with available full text were included. A two-stage screening process assessed eligibility, reviewing titles, abstracts, and full text to ensure articles focused on immigrant and refugee experiences during U.S. disasters.

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they were published before 2018, were not research articles, did not focus on immigrant or refugee experiences during U.S. disasters, or were not written in English.

Results

Characteristics of the Literature

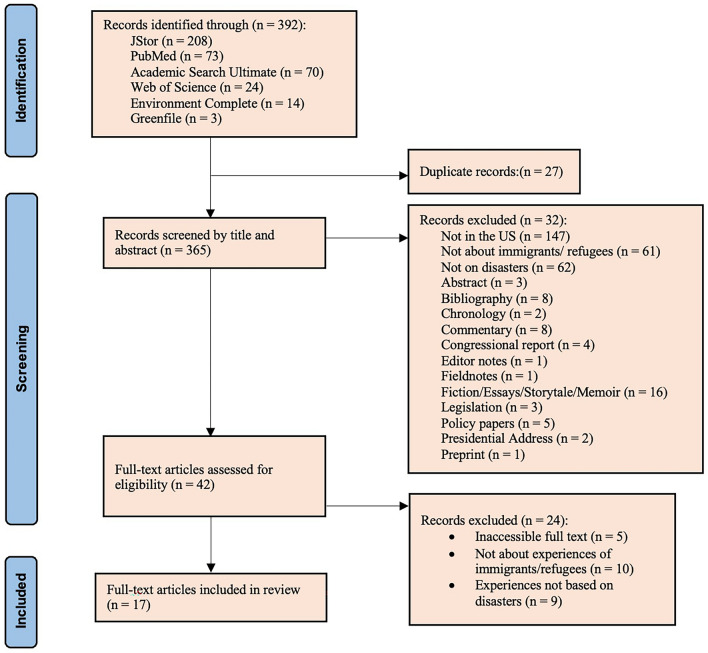

The keyword search yielded 208 articles in JSTOR, 73 in PUBMED, 70 in Academic Search Ultimate, 24 in Web of Science, 14 in Environment Complete, and 3 in Greenfile, totaling 392 articles across the six databases. As shown in Fig. 1, the initial screening excluded 323 records for the following reasons:

54 were not research articles: These included abstracts, bibliographies, chronologies, commentaries, essays, editor’s notes, fiction, legislation, memoirs, policy papers, presidential addresses, preprint, and story tales.

147 were not centered on experiences within the U.S.: Many articles focused on migrants from regions such as Africa, South America, and the Middle East. Others addressed crises abroad, including food security, mental health disorders, and women’s education in the Muslim world.

61 were not about immigrants or refugees: The excluded articles focused on the general population rather than specifically on immigrants or refugees, covering topics such as nightclub shootings of LGBTQ individuals, psychological trauma in children and young adults, global warming socio-politics, evacuee service coordination challenges, global food security, and housing stability.

62 were not about disasters: Other excluded articles covered various topics, including the criminalization of terrorist financing, criminal justice system, multilateralism, interdependence, internal brain drains, border profiteers, public cost of unilateral action, corporate renewable investments, Trump’s zero-tolerance policy, transitions, antibiotic use, trustworthy government, and legitimating beliefs.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of a systematic review on the experience of immigrants during disasters in the US (2018 – 2023)

In the second-round screening, 41 full-text research articles were assessed for eligibility, with 24 records ultimately excluded for the following reasons:

Five records were excluded due to the inaccessibility of the full text.

Nine records addressed immigrant and/or refugee experiences unrelated to disasters.

10 articles mentioned immigrants and/or refugees but did not focus on their challenges during disasters.

A total of 17 contributions were deemed eligible for full-text analysis and inclusion in the systematic review. Of the 17 articles included for analysis, 12 had an immigrant-specific focus, while the rest examined broader ethnic minority groups that included immigrants. The low number of contributions and the reduced proportion of articles that directly explored immigrants’ experiences reinforce our assertion that these populations are not often considered as a distinct group, obscuring their differential vulnerability.

A range of immigrant groups and nationalities were examined in these studies. Six articles focused on Latin American immigrants from Mexico, Honduras, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Venezuela, El Salvador, and the Dominican Republic. Three studies each centered on Vietnamese Americans and Chinese immigrants. Other populations included immigrants from Africa, Korea, the Philippines, and Cambodia. Four studies did not identify nationality or focused broadly on immigrant status.

The articles covered a range of subpopulations including, undocumented migrants, first-generation immigrant children, international graduate students (temporary migrants or visitors), naturalized immigrants, and refugees. Specifically, the studies emphasized migrant workers, migrants who relocated after disasters, and broader categories like Hispanic /Latino or Asian immigrants and Low English.

Proficiency (LEP) groups were also a focus in some of the studies.

The methodologies employed included a mix of quantitative (n = 8), qualitative (n = 6), and mixed method (n = 3) approaches. Quantitative studies used surveys (n = 5), analysis of census or administrative data (n = 3), descriptive and inferential statistics (n = 6), regression modeling (n = 3), and causal inference methods (n = 1). Qualitative studies utilized interviews (n = 5), focus groups (n = 2), participant observation and ethnographic fieldwork (n = 2), case studies (n = 3), and community meetings/feedback sessions (n = 1). Sample sizes varied from 36 participants in a focus group discussion to 42,862 from the World Trade Center Health Registry. Additionally, one study had over 7 million tweets but did not have direct study participants. There were three studies with an unspecified number of participants. Differences in sample sizes and recruitment policies suggest that we cannot meaningfully learn about intergroup differences nor make clear statements about potential biases that may be introduced across groups.

Disasters examined in the articles include natural hazards such as the EF3 tornado, the Thomas wildfires, COVID-19, and hurricanes Katrina, Harvey, and Maria. Additionally, the 9/11 terrorist attacks, a human-induced disaster was the focus of one study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of the articles included for review

| Author and Date | Methodology | Immigrant groups examined | # Study participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calvo, R., & Waters, M. C. (2023). [104] | Qualitative study based on in-depth interviews | Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Dominicans, Salvadorans, and Venezuelans | 178 |

| Hinchey, L. M.-E., Nashef, R., Bazzi, C., Gorski, K., & Javanbakht, A. (2023). [102] | Longitudinal study using self-report measures at two timepoints—upon arrival to the US and 2 years later. Used linear mixed-effects modeling to analyze the data | Minor refugees from Syria and Iraq who resettled in Michigan | 74 |

| Pham, N. K., Do, M., & Diep, J. (2023). [99] | Cross-sectional study using structured interviews and quantitative analysis | Vietnamese Americans living in the Houston, Texas area who were affected by Hurricane Harvey in 2017 | 120 |

| Hamideh, S., & Sen, P. (2022). [105] | Qualitative case study using interviews and ethnographic fieldwork | Focused on immigrant households in Marshalltown, Iowa, but did not specify particular immigrant groups | Not specified |

| Raker, E. J. (2022). [101] | Quantitative analysis of survey data. Used causal inference techniques like difference-in-differences and fixed effects models | Looked at first-generation immigrant children compared to native-born children. Did not provide breakdowns by specific immigrant groups | 160 |

| Yusuf, K. K., Madu, E., Kutchava, S., & Liu, S. K. (2022). [100] | Cross-sectional study using an online survey | African immigrants in the United States | 260 |

| Blue, S. A. (2021). [91] | Mixed methods combining quantitative survey data and qualitative in-depth interviews | Latino immigrants, predominantly from Central America—Honduras, Mexico, and other Central American countries | 256 |

| Ch Cheong, S.-M., & Babcock, M. (2021). [92] | Qualitative timeline analysis of tweet narratives & quantitative analysis of tweet spread and users | Did not specifically examine distinct immigrant groups | Over 7 million tweets but not direct study participants |

| Chu, H., Liu, S., & Yang, J. Z. (2021). [106] | Quantitative survey research. Data collected via online surveys | The study specifically focused on Chinese immigrants in Houston who used the social media platform WeChat | The study had 584 total participants. Of these, 82 were Chinese WeChat users and 126 were Hispanic respondents |

| Lara, M., Díaz Fuentes, C., Calderón, J., Geschwind, S., Tarver, M., & Han, B. (2021) [102] | Randomized controlled trial | Hispanic/Latino Day laborers in New Orleans, LA, predominantly from Honduras and Mexico | 98 |

| Maduka-Ezeh, A., Ezeh, I., Bagozzi, B., Horney, J., Nwegbu, S., & Trainor, J. (2021). [95] | Qualitative study using online focus groups | immigrants from 17 different countries across North America, Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia | 45 |

| Meltzer, G. Y., Zacher, M., Merdjanoff, A., Do, M. P., Pham, N. K., & Abramson, D. (2021). [98] | The study combined longitudinal data from 3 cohorts of survivors of Hurricane Katrina in 2005—the Resilience in Survivors of Katrina (RISK) project, the Gulf Coast Child, and Family Health (G-CAFH) study, and the Katrina Impacts on Vietnamese Americans in New Orleans (KATIVA NOLA) study | The KATIVA NOLA cohort examined Vietnamese immigrant families in New Orleans |

473 dyads from the RISK cohort 145 dyads from the G-CAFH cohort 30 dyads from the KATIVA NOLA cohort of Vietnamese immigrants |

| Chu, H., & Yang, J. Z. (2020) [107] | Quantitative analysis of survey data | Houston’s Chinese immigrant community | Not specified |

| DeYoung, S. E., Lewis, D. C., Seponski, D. M., Augustine, D. A., & Phal, M. (2020). [97] | Quantitative survey methodology | Cambodian and Laotian immigrant communities living along the Gulf Coast of the United States | 461 |

| Kozo, J., Wooten, W., Porter, H., & Gaida, E. (2020). [93] | Case study, focus groups, community feedback sessions, training sessions, and drills with partner organizations | Limited English-proficient populations in San Diego County, especially Spanish, Tagalog, Chinese, Arabic, Korean, Vietnamese, Karen and Somali speakers | Over 100 individuals and 490 partner organizations |

| Méndez, M., Flores-Haro, G., & Zucker, L. (2020) [94] | Case study using participant observation and interviews during and after the Thomas Fire in California in 2017–2018 | Undocumented Latino/a and indigenous immigrants in California’s Ventura and Santa Barbara counties | Not specified |

| Kung, W. W., Liu, X., Huang, D., Kim, P., Wang, X., & Yang, L. H. (2018). [96] | Bivariate chi-square tests, multivariate logistic regression modeling, Wald tests for racial differences, and multiple testing adjustment using the Hochberg method | Focused on Asian Americans, compared to non-Hispanic Whites | Included 4721 Asian Americans and 42,862 non-Hispanic Whites from the World Trade Center Health Registry |

Thematic Analysis of Immigrant Experiences

. 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the key themes and challenges identified through the literature review, organized into four interconnected areas of vulnerability separated into quadrants: (1) excessive economic burden, (2) legal status, (3) limited informational resources and (4) structural challenges The arrows in the diagram illustrate how these factors influence and compound one another, creating a complex web of vulnerabilities for immigrants affected by disasters in the U.S.

Excessive Economic Burden

Labor Exploitation

Pre-existing vulnerabilities are exacerbated when immigrants (especially undocumented immigrants) provide vital manual labor in disaster response, recovery, and rebuilding efforts. However, they often lack workplace rights, protections, and access to aid. For instance, Lara et al. (2021), discussed how immigrant Hispanic day laborers were concentrated in high-risk construction occupations. Contractors intentionally violated safety laws, failed to provide protective equipment, and exposed workers to dangerous conditions during debris clean-up and rebuilding after disasters like Hurricane Katrina. These issues align with the “Labor Exploitation” and “Economic Precarity” aspects highlighted in the first quadrant of Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Depiction of the overarching themes and immigrants specific challenges during a disaster

Nevertheless, fear of deportation deters reporting injuries, unsafe working environments, and wage theft. Language barriers and lack of familiarity with labor regulations among immigrant workers enable exploitation by employers according to Lara et al. (2021). Similarly, Méndez et al. (2020), described the plight of undocumented immigrant farmworkers forced to labor in ash-filled fields with minimal protective gear during the California wildfires. Their precarity as irregular workers inhibited complaints despite hazardous respiratory exposures.

In addition to language and cultural identity, gender also mediates experiences. For instance, though post-Katrina New Orleans attracted Latino migrants with construction job prospects, women were segregated into lower-paid domestic roles, such as cleaning and caregiving, which were subject to strict control and oversight, limiting their autonomy and opportunities for advancement. In contrast, men initially accessed higher-tier rebuilding jobs with greater flexibility and potential for upward mobility until wages declined. Women’s avoidance of construction work was partly due to gendered expectations around family care responsibilities, demonstrating how the unequal distribution of household and childcare duties can shape disaster labor outcomes and reinforce gender disparities in the workforce [91].

Economic Precarity

Pham et al. (2023), found that Vietnamese Americans affected by Hurricane Harvey in Houston exhibited notably low average scores on physical and mental health components a year after the storm, indicating sub-optimal health likely related to economic stressors inhibiting recovery. Meanwhile, Lara et al. (2021) worked with immigrant Hispanic day laborers rebuilding New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina exposed precarious pre-disaster livelihoods, with laborers exploited by contractors who ignored occupational safety laws and failed to provide benefits. COVID-19 only intensified the economic marginalization of undocumented immigrants concentrated in insecure service occupations, as described by Méndez et al. (2020). They were deemed “essential workers” yet excluded from unemployment benefits, paid leave protections, and federal relief payments in the CARES Act, forcing continued unsafe work while sick to avoid income loss [92, 93].

Multiple studies documented substantial job and income losses experienced by immigrants during disaster events, which federal policies then excluded them from recouping. For instance, Calvo and Waters (2023) found the older Latino immigrants interviewed lost jobs or work hours due to pandemic closures, could not access unemployment insurance, and avoided other governmental pandemic aid even when eligible due to confusion over the proposed Public Charge rule. Also, economic recovery programs like FEMA assistance or federal disaster loans administered through the Small Business Association had strict eligibility requirements regarding immigration status, credit history, and collateral that excluded many immigrants.

Several studies pointed to language barriers, lack of awareness of programs, and stringent regulations of governmental authorities as obstacles that prevent immigrants from accessing economic assistance post disaster. Chu et al. (2021) observed that ethnic media played a pivotal role in informing Chinese immigrants about pandemic economic aid. Local organizations had to step in to provide cash assistance to undocumented immigrants during wildfires in California partly because governmental agencies failed to disseminate information about relief in languages other than English [94]. Kozo et al. (2020) recommended linguistic and cultural tailoring of economic recovery programs to ensure equitable immigrant access.

Immigrants also utilized informal networks to economically cope after disasters in the absence of governmental support. Calvo and Waters (2023) described how older Latino immigrants shared pensions and Social Security income with unemployed family members and sought assistance from churches and nonprofits. Strategies also included taking out high-interest payday loans or credit card debt to cover necessities [92]. Savings from remittances previously sent to home countries pre-disaster helped temporarily sustain some immigrant households after job loss [95]. While exemplifying resilience, such makeshift solutions left immigrants vulnerable to spiraling debt and compounded economic precarity long after the initial disaster event.

Adverse Health outcomes

Unaddressed language barriers, cultural isolation, discrimination, and social marginalization contribute to immigrants’ disproportionate risk of disaster-related morbidity and mortality. Several studies revealed lingering psychological distress, anxiety, depression, psychiatric problems, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) persisting or even worsening over time in groups ranging from Vietnamese, Hispanic, and African immigrants to Asian American minorities [97–100]. This aligns with evidence of overall poorer self-rated health among immigrant children after disasters [101].

As indicated by Fig. 2, immigrant status emerged as a critical factor that intersects with minority race/ethnicity to confer greater susceptibility to both mental and physical health declines following disasters. Pre-migration trauma combines post-migration challenges and sociocultural dynamics to exacerbate disaster impacts as immigrants adjust to their new society [96, 97, 100]. For instance, a higher prevalence of anxiety, depression, and PTSD was observed among Cambodian immigrants after disasters compared to the general public [97]. This aligns with evidence from Yusuf et al. (2022) that the COVID-19 pandemic doubled rates of depression and anxiety among African immigrants in America.

Additionally, Kung et al. (2018) revealed critical sociocultural factors likely contribute to heightened adverse mental health outcomes post-disaster among immigrants. Cultural tendencies to express psychological distress through physical symptoms, combined with stigma and underutilization of mental health services, may impede the diagnosis and treatment of conditions like PTSD. For instance, Asian immigrants’ underutilization of mental healthcare after 9/11 partly stemmed from social stigmas around psychological help-seeking rather than integrated social linkage with providers [96]. Without timely, appropriate interventions, symptoms often persist or worsen over time, as indicated among war-exposed refugee youth in the two years after resettlement [102].

Legal Status

The second quadrant in Fig. 2 illustrates how restrictive immigration policies and visa policies coupled with fear of deportation creates legal challenges for immigrants. These legal barriers correlate strongly with increased economic hardship and limited access to critical information resources, highlighting the interconnected obstacles immigrants face in their new environments.

Restrictive Immigration Status and Visa Policies

Restrictive immigration policies and tenuous legal status exacerbate vulnerabilities for immigrants affected by disasters in the U.S. writ large. According to Calvo & Waters (2023), undocumented immigrants are restricted in terms of receiving federal disaster relief and aid despite paying taxes due to their unlawful status. Similarly, immigrants with legal status may avoid seeking government assistance after disasters because of confusion over eligibility or fear of negative consequences under restrictive policies. One such example is the proposed Public Charge rule under the Trump administration. The form, which was eliminated during Biden’s administration, cultivated fears that using public benefits could jeopardize green card or citizenship applications, deterring disaster aid access [91].

Restrictive immigration enforcement predominantly threatens immigrants who lack permanent legal status with deportation and family separation. This fear prevents them from evacuating to public shelters, pursuing healthcare, or reporting unsafe working conditions during rebuilding after disasters [94]. Undocumented immigrant laborers performing dangerous demolition and construction jobs post-disaster have little recourse against exploitation by employers who take advantage of their shaky immigration status [103]. The undocumented status has the effect of compelling immigrants to remain in unsafe conditions rather than seek assistance [92].

Unfortunately, repercussions of constrictive policies extend beyond the individual to the family unit that often accompanies the immigrant, augmenting the vulnerability of the household. Even more egregious is that immigration policy constraints may also undermine larger societal efforts at aiding and containing the crisis. For example, visa restrictions prohibited physicians from working outside their specified location, preventing highly qualified individuals from assisting with the pandemic response in overloaded hospitals even if willing and able.

Fear of Deportation

The constant fear of being separated from family members caused some immigrants to remain in damaged, unsafe housing after disasters rather than seek temporary shelter or housing assistance [92, 94]. Immigrants without a current legal status might be afraid of using public services that could jeopardize their ability to stay in the country. They avoid interacting with any government providers or facilities where their unauthorized status could arise [92]. Fear of deportation stops immigrants from visiting shelters or from pursuing healthcare to treat injuries or illnesses resulting from the disaster.

The possibility of incarceration and deportation prevents undocumented immigrant workers from reporting unsafe conditions, wage theft, or labor violations by employers during disaster rebuilding efforts. In turn, some employers tend to exploit their situation by deliberately failing to provide protective equipment, adequate wages, or benefits [94, 103]. There is also evidence of impacts among those who hold visitor permits that may afford them limited rights, such as those on temporary work visas. A pervasive climate of fear leads to avoidance of routine public health and social services among immigrants, exacerbating precarious living conditions that increase disaster vulnerability [104].

Limited Informational Resources

Selective Disaster Relief Measures

As illustrated in quadrant 3 of Fig. 2, existing disaster policies and programs often fail to provide equitable relief that meets the unique needs and overcomes the access barriers confronting these immigrant communities. Studies reviewed revealed major gaps, exclusions, and weaknesses in current disaster assistance efforts that serve to amplify suffering for the most vulnerable [91, 104, 105]. Other analyses also highlighted alternative sources of aid and strategies to build resilience when formal relief mechanisms neglect those most in crisis [95, 98]. For instance, an immigrant family having fled disaster only to encounter protracted resettlement instability, is disproportionately impacted by a subsequent crisis due to inaccessible relief mechanisms, resulting in compounded vulnerability that highlights inequities in disaster policy [91, 104, 105].

The exclusionary tenor of immigration policies was most pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic with pieces of legislation that explicitly excluded undocumented immigrants. Lack of access to government aid left many immigrants unemployed due to COVID-19, struggling to afford food, housing, and healthcare [104]. Similar dynamics occurred after Hurricane Harvey in Texas when many immigrants avoided applying for FEMA and other disaster benefits due to immigration concerns, leaving basic needs unmet [92].

After tornadoes struck immigrant-heavy neighborhoods in Iowa, language barriers and unfamiliarity in navigating bureaucratic aid systems prevented many residents from accessing FEMA and other recovery resources they desperately needed [93, 105]. Faith groups and nonprofits distinctly stepped up during both crises to provide alternative support like housing, food, and direct cash aid specifically targeting immigrant families neglected by federal programs. While crucial, these voluntary efforts could not fully replace equitable access to publicly funded relief [104, 105].

Limited Social Capital

Social capital constitutes the social bonds and communal resources individuals can leverage to access invaluable information, aid, and support [62]. However, Fig. 2 indicates that immigrants often have restricted social capital that exacerbates their vulnerability and hampered resilience [96, 106].While strong bonding ties exist within ethnic enclaves, bridging linkages to external assets may be lacking. Some studies reveal how this social capital deficiency compounds hardship when disasters hit while highlighting strategies to cultivate connections vital for resilience [92, 107]. A key finding from studies of Houston’s Chinese immigrant community is that dense bonding social capital does not necessarily confer the ability to withstand, adapt to, and recover from disasters [107]. While tight communal ties allowed coordinating ethnic-specific disaster response efforts after Hurricane Harvey, this bonding capital did not sufficiently bridge gaps blocking access to mainstream information and relief channels.

A recurrent theme is that policies overly focused on strengthening internal community resilience neglect the necessity of bridging social capital and establishing reliable and unambiguous channels of dialogue between different groups [106, 107]. For instance, during Hurricane Harvey evacuations, some immigration agents circulated messages on social media suggesting that evacuees would be asked for identification at shelters, which would lead to detainment of undocumented immigrants. These warnings, while not explicitly threatening arrest, created uncertainty and fear among immigrant communities. Advocates and government officials later attempted to clarify that immigration enforcement would not be conducted at evacuation sites, but the initial lack of clear, consistent messaging from authorities led to confusion and hesitation, delaying evacuation for many immigrants. As this example demonstrates, establishing trusted ties between immigrant communities and authorities to effectively coordinate communication is essential [92]. Studies have shown that disaster preparedness messaging solely transmitted through ethnic media outlets may fail to reach recently arrived immigrant groups with limited native language media access, pointing to the need for broader linkages between government, groups, and communities [93].

Structural Challenges

Housing and Transportation Inadequacies

Immigrants often reside in areas with aged, substandard infrastructure that exacerbates their vulnerability when disasters strike. Pham et al. (2023) noted that the large Vietnamese American population in Houston resided disproportionately in flood-prone areas, likely contributing to the high levels of storm exposure and mental health distress they exhibited after Hurricane Harvey. Méndez et al. (2020) criticized the neglect of California’s aging electricity infrastructure which sparked wildfires that endangered immigrant farmworkers, while Hamideh and Sen (2022) described tornado damage concentrated in the older, poorly maintained rental housing stock where immigrants resided in Marshalltown, Iowa.

Inadequate public transportation and services in receiving communities also challenge immigrants’ ability to access food, medications, schools, and jobs after relocating post-disaster. Meltzer et al. (2021) found that Vietnamese immigrants still displaced from Hurricane Katrina over a decade earlier lacked key social services in their host community, amplifying adolescents’ risk for psychological distress amidst repeated hurricane exposures.

Communication Challenges

Communication infrastructure failures posed additional risks, especially for immigrants with limited English proficiency unable to access emergency alerts or evacuation orders. Kozo et al. (2020) described how entire LEP neighborhoods went without emergency notifications during past wildfires and blackouts. Also, immigrants disproportionately rely on threatened infrastructure sectors for their livelihoods, including fisheries, agriculture, and tourism. Storms consistently devastate these industries along the Gulf Coast where many immigrants are employed per DeYoung et al. (2020), who argue policy changes are needed to facilitate immigrants’ disaster resilience and optimal utilization during response and recovery when these economic sectors are disrupted.

Discussions

The distinctiveness of immigrant disaster experiences (in response to hypothesis one (H1)) is underscored by a range of studies that highlight the multifaceted barriers they encounter before, during, and after disasters. These obstacles are intricately tied to the themes identified such as fear of deportation, restrictive immigration status and visa policies, selective disaster relief measures, and limited access to medical, financial, material, and information resources shape immigrants’ capacity to adapt and respond to disasters [73, 94, 108–113]. These findings align with the social and political ecology framework.

The unidirectional arrow from the legal status quadrant in Fig. 2. illustrates how legal status fundamentally shapes immigrants’ disaster experiences. Undocumented immigrants and mixed-status families face more significant barriers to information, aid, and resources compared to naturalized citizens or legal permanent residents [91, 94, 101], creating a cascading effect that amplifies their vulnerability to structural challenges and economic burdens. Furthermore, everyday marginalization and inequities across various domains compound immigrants’ vulnerability and hinder their recovery in the aftermath of disasters [92, 94].

The review also confirms hypothesis two (H2), revealing substantial variations in disaster impacts within immigrant groups based on factors like nationality, visa status, time spent in the U.S., age, gender, and socioeconomic status. [114, 115]. Undocumented immigrants and mixed-status families faced more aid barriers than naturalized citizens or lawful permanent residents (LPRs) [91, 94, 101].

These findings emphasize the need to disaggregate immigrants to fully capture the complexity of their disaster outcomes [77]. Lastly, the review aligns with the theory’s propositions regarding the influence of variable access to capital, social marginalization, and structural disparities on disaster vulnerability and resilience [65, 73, 116, 117].

However, this review has certain limitations. Firstly, the strict search criteria may have excluded potentially relevant studies. Widening the search to include additional databases and gray literature could provide fuller coverage of the research. Publication bias may have also skewed findings toward studies demonstrating poorer immigrant outcomes. Also, the focus on US-based literature excludes insights from other major immigrant-receiving nations. Secondly, the chosen timeframe of 2018–2023, may not capture the full extent of the long-term impacts of disasters and policy changes on immigrant populations.

Conclusions

This systematic review examined disaster experiences and impacts on U.S. immigrants, confirming evidence of their heightened risks and disproportionately adverse outcomes compared to native-born populations [90, 93, 94]. The findings emphasize the importance of disaggregating immigrant data and accounting for demographic heterogeneity, pre-migration vulnerabilities, and immigration-related factors within this diverse population. Understanding these complex dynamics is crucial for comprehending the unique challenges immigrants face in disaster contexts.

Author Contributions

All authors listed made substantial contributions to the manuscript preparation. DBG played a pivotal role in the idea conceptualization, manuscript preparation, provided critical oversight to the data analysis process, and extensively edited the manuscript. YAD was heavily involved in the data retrieval, data analysis, preparation, and editing of the manuscript. VR and EAG both provided crucial revisions to the manuscript and were actively engaged in the editing process. All authors have thoroughly reviewed the final manuscript and have given their approval for submission.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Science Foundation as part of the Megalopolitan Coastal.Transformation Hub (MACH) under NSF award ICER-2103754. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fordham M, Lovekamp WE, Thomas DSK, Phillips BD. Understanding social vulnerability. Soc Vulnerability Disasters. 2013;9:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman S. Preparing for disaster: protecting the most vulnerable in emergencies. UC Davis Law Rev. 2008;42:1491. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray JS, Monteiro S. Disaster risk and children. Part II: how pediatric healthcare professionals can help. J Spec Pediatr Nurs: JSPN. 2012;17:258–60. 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2011.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi L, Stevens GD. Vulnerable populations in the United States. John Wiley & Sons; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wisner, B. (Ed.). (2004). At risk: Natural hazards, people’s vulnerability, and disasters (2nd ed). Routledge.

- 6.Bankoff, G., Frerks, G., & Hilhorst, T. (Eds.). (2004). Mapping vulnerability: Disasters, development, and people. Earthscan Publications.

- 7.Cutter SL, Boruff BJ, Shirley WL. Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Soc Sci Q. 2003;84(2):242–61. 10.1111/1540-6237.8402002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flanagan BE, Gregory EW, Hallisey EJ, Heitgerd JL, Lewis B. A Social vulnerability index for disaster management. J Homel Secur Emerg Manage. 2011. 10.2202/1547-7355.1792. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masozera M, Bailey M, Kerchner C. Distribution of impacts of natural disasters across income groups: a case study of new Orleans. Ecol Econ. 2007;63(2–3):299–306. 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.06.013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tierney KJ. From the margins to the mainstream? Disaster research at the crossroads. Ann Rev Sociol. 2007;33(1):503–25. 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131743. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caron RM, Adegboye ARA. COVID-19: a syndemic requiring an integrated approach for marginalized populations. Front Public Health. 2021;9:675280. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.675280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.OHCHR, & Global Migration Group. (2018). Principles and guidelines on the human rights protection of migrants in vulnerable situations. OHCHR. https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/tools-and-resources/principles-and-guidelines-human-rights-protection-migrants-vulnerable

- 13.Trentin M, Rubini E, Bahattab A, Loddo M, Della Corte F, Ragazzoni L, Valente M. Vulnerability of migrant women during disasters: a scoping review of the literature. Int J Equity Health. 2023;22(1):135. 10.1186/s12939-023-01951-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Budiman, A. (2020). Key findings about U.S. immigrants. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/

- 15.Esterline, C., & Batalova, J. (2022). Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States. Migrationpolicy.Org. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states

- 16.Massey, D. S. (2008). New faces in new places: The changing geography of American immigration. In New faces in New Places: The Changing Geography of American Immigration (pp. 1–370). Russell Sage Foundation. https://collaborate.princeton.edu/en/publications/new-faces-in-new-places-the-changing-geography-of-american-immigr

- 17.Migration Policy Institute. (2022). U.S. Immigrant Population by Metropolitan Area. Migrationpolicy.Org. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/us-immigrant-population-metropolitan-area

- 18.Foner, N. (2002). From Ellis Island to JFK. Yale University Press. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/9780300093216/from-ellis-island-to-jfk

- 19.Bustamante AV, Chen J, Félix Beltrán L, Ortega AN. Health policy challenges posed by shifting demographics and health trends among immigrants to the United States. Health Aff. 2021;40(7):1028–37. 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Filindra A, Blanding D, Coll CG. The power of context: state-level policies and politics and the educational performance of the children of immigrants in the United States. Harv Educ Rev. 2011;81(3):407–38. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanson, G. H. (2009). The Economics and Policy of Illegal Immigration in the United States.

- 22.Abrego LJ. Legal consciousness of undocumented Latinos: fear and stigma as barriers to claims-making for first- and 1.5-generation immigrants: legal consciousness of undocumented Latinos. Law Soc Rev. 2011;45:337–70. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Enriquez LE. Multigenerational punishment: shared experiences of undocumented immigration status within mixed-status families. J Marriage Fam. 2015;77(4):939–53. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drabek TE. Human system responses to disaster. Springer NY. 1986. 10.1007/978-1-4612-4960-3. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fritz, C. E. (1961). Disaster. Institute for Defense Analyses, Weapons Systems Evaluation Division.

- 26.Kreps GA. Sociological inquiry and disaster research. Ann Rev Sociol. 1984;10(1):309–30. 10.1146/annurev.so.10.080184.001521. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreps GA, Drabek TE. Disasters are nonroutine social problems. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters. 1996;14(2):129–53. 10.1177/028072709601400201. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dynes RR. Organizational involvement and changes in community structure in disaster. Am Behav Sci. 1970;13(3):430–9. 10.1177/000276427001300313. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quarantelli EL. Realities and mythologies in disaster films. Comm. 1985;11(1):31–44. 10.1515/comm.1985.11.1.31. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perry RW, Lindell MK. Emergency planning. Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coronese M, Lamperti F, Keller K, Chiaromonte F, Roventini A. Evidence for sharp increase in the economic damages of extreme natural disasters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(43):21450–5. 10.1073/pnas.1907826116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, Ö., Yu, R., & Zhou, B. (Eds.). (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/9781009157896

- 33.USGCRP. (2018). Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment (Volume II; p. 1515). U.S. Global Change Research Program. nca2018.globalchange.gov

- 34.IDMC. (2023). IDMC | GRID 2023 | 2023 Global Report on Internal Displacement. https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2023/

- 35.Clement, V., Rigaud, K. K., de Sherbinin, A., Jones, B., Adamo, S., Schewe, J., Sadiq, N., & Shabahat, E. (2021). Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/36248

- 36.Rigaud, K. K., de Sherbinin, A., Jones, B., Bergmann, J., Clement, V., Ober, K., Schewe, J., Adamo, S., McCusker, B., Heuser, S., & Midgley, A. (2018). Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration. 10.1596/29461

- 37.Batalova, J. (2024). Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States. Migrationpolicy.Org. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states-2024

- 38.Batalova, J., & Sanchez, M. (2021). Naturalized Citizens in the United States. Migrationpolicy.Org. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/naturalization-trends-united-states

- 39.Office of Homeland Security Statistics. (2023). Glossary | Homeland Security. https://www.dhs.gov/ohss/about-data/glossary

- 40.Green Card Eligibility Categories | USCIS. (2022). https://www.uscis.gov/green-card/green-card-eligibility-categories

- 41.Zong, J., & Batalova, J. (2015). The Limited English Proficient Population in the United States in 2013. Migrationpolicy.Org. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/limited-english-proficient-population-united-states-2013

- 42.Batalova, J. B. J. (2022). Temporary Visa Holders in the United States. Migrationpolicy.Org. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/temporary-visa-holders-united-states

- 43.Pope, H. (2020). Annual Flow Report July 2020—U.S. Nonimmigrant Admissions: 2019.

- 44.USCIS. (2020). Form I-94, Arrival/Departure Record, Information for Completing USCIS Forms | USCIS. https://www.uscis.gov/forms/all-forms/form-i-94-arrivaldeparture-record-information-for-completing-uscis-forms

- 45.Immigration and Nationality Act | USCIS. (2019). https://www.uscis.gov/laws-and-policy/legislation/immigration-and-nationality-act

- 46.UNHCR. (2022). UNHCR - Refugee Statistics. UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/

- 47.Congressional Research Service. (2022). R47318.pdf. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47318

- 48.Camarota, S. A., & Zeigler, K. (2018). Overcrowded Housing Among Immigrant and Native-Born Workers. Healthcare Practitioners.

- 49.Alba R, Foner N. Strangers no more: immigration and the challenges of integration in North America and Western Europe. Princet Univ Press. 2015. 10.1515/9781400865901. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haller W, Portes A, Lynch SM. Dreams fulfilled and shattered: determinants of segmented assimilation in the second generation. Soc Forc. 2011. 10.1353/sof.2011.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee, J., & Zhou, M. (2015). The Asian American achievement paradox (pp. xx, 246). Russell Sage Foundation.

- 52.Hall M, Greenman E. Housing and neighborhood quality among undocumented Mexican and central American immigrants. Soc Sci Res. 2013. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White MJ, Glick JE. Achieving anew: How new immigrants do in American schools, jobs, and neighborhoods. Russell Sage Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xie Y, Gough M. Ethnic enclaves and the earnings of immigrants. Demography. 2011;48(4):1293–315. 10.1007/s13524-011-0058-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Menjívar C, Abrego LJ. Legal violence: immigration law and the lives of central American immigrants. Am J Sociol. 2012;117(5):1380–421. 10.1086/663575. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sohn H, Aqua JK. Geographic variation in COVID-19 vulnerability by legal immigration status in California: a prepandemic cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(5):e054331. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parker Frisbie W, Cho Y, Hummer RA. Immigration and the health of Asian and pacific Islander adults in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(4):372–80. 10.1093/aje/153.4.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Balsari S, Dresser C, Leaning J. Climate change, migration, and civil strife. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2020;7(4):404–14. 10.1007/s40572-020-00291-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eisenman DP, Glik D, Maranon R, Gonzales L, Asch S. Developing a disaster preparedness campaign targeting low-income Latino immigrants: focus group results for project PREP. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(2):330–45. 10.1353/hpu.0.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferris, E. (2015). Disasters, displacement, and climate change: New evidence and common challenges facing the north and south. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/disasters-displacement-and-climate-change-new-evidence-and-common-challenges-facing-the-north-and-south/

- 61.Orozco, M. (2018). CENTRAL AMERICAN MIGRATION.

- 62.Aldrich DP, Meyer MA. Social capital and community resilience. Am Behav Sci. 2015;59(2):254–69. 10.1177/0002764214550299. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bates, R. (1997). Introduction to Open-Economy Politics: The Political Economy of the World Coffee Trade.

- 64.Donner WR. The political ecology of disaster: an analysis of factors influencing U.S. tornado fatalities and injuries, 1998–2000. Demography. 2007;44:669–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peacock, W., & Ragsdale, K. (1997). Social Systems, Ecological Networks, and Disasters: Toward a Socio-Political Ecology of Disasters (pp. 20–35).

- 66.Phillips, B. D. (2015). Disaster recovery (Second Edition). CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group.

- 67.Yin, R. K. (with Campbell, D. T.). (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (Sixth edition). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- 68.Collins J, Ersing R, Polen A, Saunders M, Senkbeil J. The effects of social connections on evacuation decision making during hurricane Irma. Weather, Climate, and Society. 2018;10(3):459–69. 10.1175/WCAS-D-17-0119.1. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Klinenberg, E. (2018). Palaces for the people: How social infrastructure can help fight inequality, polarization, and the decline of civic life (First Edition). Crown.

- 70.Finucane ML, Acosta J, Wicker A, Whipkey K. Short-term solutions to a long-term challenge: rethinking disaster recovery planning to reduce vulnerabilities and inequities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(2):482. 10.3390/ijerph17020482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wilson B, Tate E, Emrich CT. Flood recovery outcomes and disaster assistance barriers for vulnerable populations. Front Water. 2021. 10.3389/frwa.2021.752307. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bennett Gayle D, Yuan X, Knight T. The coronavirus pandemic: accessible technology for education, employment, and livelihoods. Assis Technol. 2021. 10.1080/10400435.2021.1980836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peacock WG, Van Zandt S, Zhang Y, Highfield WE. Inequities in long-term housing recovery after disasters. J Am Plann Assoc. 2014;80(4):356–71. 10.1080/01944363.2014.980440. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang Z, Lam NSN, Obradovich N, Ye X. Are vulnerable communities digitally left behind in social responses to natural disasters? An evidence from Hurricane Sandy with Twitter data. Appl Geogr. 2019;108:1–8. 10.1016/j.apgeog.2019.05.001. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Amaya, S. (2022). “We’re Like Ghosts, but We Have to Be.” Invisibility & Liminality Among Kentuckiana’s Undocumented Population. Undergraduate Theses. https://scholarworks.bellarmine.edu/ugrad_theses/94

- 76.DasGupta S, Charon R. Personal illness narratives: using reflective writing to teach empathy. Acad Med. 2004;79(4):351–6. 10.1097/00001888-200404000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities: old issues, new directions. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):115–32. 10.1017/S1742058X11000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wilkes R, Wu C. Immigration, discrimination, and trust: a simply complex relationship. Front Sociol. 2019;4:32. 10.3389/fsoc.2019.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McKenzie JE. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021. 10.1136/bmj.n160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ioannidis JPA. Systematic reviews for basic scientists: a different beast. Physiol Rev. 2023;103(1):1–5. 10.1152/physrev.00028.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Siddaway AP, Wood AM, Hedges LV. How to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, Meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annu Rev Psychol. 2019;70(1):747–70. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sohrabi C, Franchi T, Mathew G, Kerwan A, Nicola M, Griffin M, Agha M, Agha R. PRISMA 2020 statement: what’s new and the importance of reporting guidelines. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105918. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cutter SL. The changing nature of hazard and disaster risk in the anthropocene. Ann Am Assoc Geogr. 2021;111(3):819–27. 10.1080/24694452.2020.1744423. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Smith, A. B. (2024). 2023: A historic year of U.S. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters | NOAA Climate.gov. http://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2023-historic-year-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters

- 85.Clark E, Fredricks K, Woc-Colburn L, Bottazzi ME, Weatherhead J. Disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immigrant communities in the United States. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(7):e0008484. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Qin R, Khakzad N, Zhu J. An overview of the impact of Hurricane Harvey on chemical and process facilities in Texas. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020;45:101453. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101453. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Smith, A. B. (2020). U.S. Billion-dollar Weather and Climate Disasters, 1980—Present (NCEI Accession 0209268) . NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. 10.25921/STKW-7W73

- 88.Meissner, D. & Gelatt. (2019). Eight Key U.S. Immigration Policy Issues: State of Play and Unanswered Questions. Migrationpolicy.Org. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/eight-key-us-immigration-policy-issues

- 89.Chishti, M., Bush-Joseph, K., & Putzel-Kavanaugh, C. (2024). Biden at the Three-Year Mark: The Most Active Immigration Presidency Yet Is Mired in Border Crisis Narrative. Migrationpolicy.Org. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/biden-three-immigration-record

- 90.Chishti, M., & Bush-Joseph, K. (2023). Biden at the Two-Year Mark: Significant Immigration Actions Eclipsed by Record Border Numbers. Migrationpolicy.Org. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/biden-two-years-immigration-record

- 91.Blue SA. Gendered constraints on a strategy of regional mobility: Latino/a migration to post-Katrina New Orleans. Area. 2021;53(1):175–82. 10.1111/area.12687. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cheong S-M, Babcock M. Attention to misleading and contentious tweets in the case of Hurricane Harvey. Nat Hazards. 2021;105(3):2883–906. 10.1007/s11069-020-04430-w. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kozo J, Wooten W, Porter H, Gaida E. The partner relay communication network: sharing information during emergencies with limited English proficient populations. Health Sec. 2020;18(1):49–56. 10.1089/hs.2019.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Méndez M, Flores-Haro G, Zucker L. The (in)visible victims of disaster: understanding the vulnerability of undocumented Latino/a and indigenous immigrants. Geoforum; J Phys Human Reg Geosci. 2020;116:50–62. 10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Maduka-Ezeh A, Ezeh IT, Bagozzi BE, Horney JA, Nwegbu S, Trainor JE. US immigrants’ experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic-findings from online focus groups. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2021;14(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kung WW, Liu X, Goldmann E, Huang D, Wang X, Kim K, Kim P, Yang LH. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the short and medium term following the world trade center attack among Asian Americans. J Commun Psychol. 2018;46(8):1075–91. 10.1002/jcop.22092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.DeYoung SE, Lewis DC, Seponski DM, Augustine DA, Phal M. Disaster preparedness and well-being among Cambodian– and Laotian-Americans. Disaster Prev Manage Int J. 2020;29(4):425–43. 10.1108/DPM-01-2019-0034. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Meltzer GY, Zacher M, Merdjanoff AA, Do MP, Pham NK, Abramson DM. The effects of cumulative natural disaster exposure on adolescent psychological distress. J Appl Res Child. 2021;12(1):6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pham NK, Do M, Diep J. Social support and community embeddedness protect against post-disaster depression among immigrants: a vietnamese American case study. Front Psych. 2023;14:1075678. 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1075678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yusuf KK, Madu E, Kutchava S, Liu SK. The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and mental health of African immigrants in the United States. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2022;19(16):10095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Raker EJ. Natural hazards, disasters, and demographic change: the case of severe tornadoes in the United States, 1980–2010. Demography. 2020;57(2):653–74. 10.1007/s13524-020-00862-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hinchey LM-E, Nashef R, Bazzi C, Gorski K, Javanbakht A. The longitudinal impact of war exposure on psychopathology in Syrian and Iraqi refugee youth. Int J Soc Psych. 2023. 10.1177/00207640231177829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lara M, Díaz Fuentes C, Calderón J, Geschwind S, Tarver M, Han B. Pilot of a community health worker video intervention for immigrant day laborers at occupational health risk. Front Public Health. 2021. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.662439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Calvo R, Waters MC. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on older Latino immigrants. RSF Russell Sage Found J Soc Sci. 2023;9:60–76. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hamideh S, Sen P. Experiences of vulnerable households in low-attention disasters: marshalltown, Iowa (United States) after the EF3 Tornado. Glob Environ Chang. 2022;77:102595. 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102595. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chu H, Liu S, Yang JZ. Together we survive: the role of social messaging networks in building social capital and disaster resilience among minority communities. Nat Hazards. 2021;106(3):2711–29. 10.1007/s11069-021-04562-7. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chu H, Yang JZ. Building disaster resilience using social messaging networks: the WeChat community in Houston, Texas, during Hurricane Harvey. Disasters. 2020;44(4):726–52. 10.1111/disa.12388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Drakes O, Tate E, Rainey J, Brody S. Social vulnerability and short-term disaster assistance in the United States. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021;53:102010. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.102010. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Martinez O, Wu E, Sandfort T, Dodge B, Carballo-Dieguez A, Pinto R, Rhodes SD, Moya E, Chavez-Baray S. Evaluating the impact of immigration policies on health status among undocumented immigrants: a systematic review. J Immigr Minority Health Cent Minority Publ Health. 2015;17(3):947–70. 10.1007/s10903-013-9968-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ornelas IJ, Yamanis TJ, Ruiz RA. The health of undocumented Latinx immigrants: What We Know and Future directions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41(1):289–308. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Patel R, Gleason K. The association between social cohesion and community resilience in two urban slums of Port au Prince, Haiti. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.10.003. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Teo M, Goonetilleke A, Ahankoob A, Deilami K, Lawie M. Disaster awareness and information seeking behaviour among residents from low socio-economic backgrounds. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.09.008. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Uekusa S, Matthewman S. Vulnerable and resilient? Immigrants and refugees in the 2010–2011 Canterbury and Tohoku disasters. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017;22:355–61. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.02.006. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Burke S, Bethel JW, Britt AF. Assessing disaster preparedness among Latino migrant and seasonal farmworkers in eastern north Carolina. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2012. 10.3390/ijerph9093115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Fussell E, Delp L, Riley K, Chávez S, Valenzuela A. Implications of social and legal status on immigrants’ health in disaster zones. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(12):1617–20. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Morrow BH. Identifying and Mapping Community Vulnerability. Disasters. 1999;23(1):1–18. 10.1111/1467-7717.00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Collins T, Bolin B. Characterizing vulnerability to water scarcity: the case of a groundwater-dependent, rapidly urbanizing region. Environ Hazards. 2007;7(4):399–418. 10.1016/j.envhaz.2007.09.009. [Google Scholar]