Abstract

Palygorskite exhibits distinctive morphological and textural characteristics due to its fibrous and micropore nature. This research experimentally investigates the microstructure of palygorskite and how acid treatment changes the fibrous shape and ability to adsorb. Acetic and hydrochloric acid were used to study the effect of acid on palygorskite fibrous morphology. The effect of several factors, including acid type, hydrochloric acid concentration, mixing time, and temperature, on the efficiency of palygorskite in removing Cu was also studied. Different analytical techniques were used: scanning electron microscopy, field emission scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, X-ray fluorescence, particle size distribution, and zeta potential. Results illustrated that acetic acid effectively dispersed fibre aggregates, creating voids within the fibrous structure and reducing particle size while keeping the shape of the fiber. Hydrochloric acid led to varying degrees of structural changes. A concentration of 0.5, 1, and 2 M dispersed the fibre agglomerates and increased positive surface charge. Formation of an amorphous silica phase at 4 and 6 M, accompanied by a reduction in positive zeta potential. In general, acid pretreatment kept the morphology of the palygorskite fibre; however, 6 M HCl induced microfractures and roughness on the fibre rod. At room temperature and with a mixing time of one hour, the adsorption capacity of raw palygorskite for Cu was 298.4 ppm, while that of acetic acid pretreated palygorskite was 277.2 ppm. The primary decrease in Cu concentration occurred following palygorskite treatment with 0.5 M HCl to 212 ppm.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-88449-8.

Keywords: Acid treatment, Fibrous morphology, Microstructure, Palygorskite

Subject terms: Environmental chemistry, Structural materials

Introduction

Palygorskite (Pal), also known as attapulgite, is a kind of clay mineral. Pal is crystalline hydrated magnesium silicate with a chemical formula of (Mg, Al)5[(OH)2(Si, Al)8O20]8H2O1,2. The structure of Pal belongs to the 2:1 aluminosilicate; the sheets of silica tetrahedral are periodically inverted with respect to the tetrahedral bases3. As a result of this inversion, the octahedral sheets are periodically interrupted, and terminal cations must complete their coordination spheres with water molecules. This structure confers to the material a fibrous morphology1. The periodic inversion of tetrahedral top oxygen atoms limits the lateral extension of octahedral sheet, and the crystal structure (fibrous rod-shaped) of Pal brings it excellent physicochemical properties, such as a high adsorption capacity, fibrous morphology, high porosity, high surface area, moderate cation exchange, excellent surface reactivity and charge in the lattice4–6. Pal is widely utilized in the chemical industry for various applications, including adsorption, ion exchange, catalysis, fillers, and water softening4,7–10. It is widely known that the physical and chemical properties of Pal, which are attributed to its rod crystal shape and nanopore structure, provide the basis of its large-scale, multi-domain applications. These unique structural characteristics also distinguish Pal from other layered silicates5.

To enhance the properties of Pal and expand its applications, Pal underwent extensive processing. Considerable effort has been dedicated to enhancing the morphology and surface properties, in particular through acid processing. The process involves removing the impurities minerals in the Pal clay (carbonates or oxides), modifying the surface area, micropore volume and porosity, and increasing the adsorption sites through disaggregation of Pal particles. It can also get rid of some octahedral ions to get partially dissolved materials with better surface activity that can be used for things like adsorption, decolorizations, and reactions that need acidic catalysis11,12. The properties of Pal are related to its unique rod-like crystal structure; hence, the acid pretreatment process influences not only the surface characteristics but also the fibrous morphology and the shape and length of rods. A previous study reported that the effect of acid treatment on clay is dependent on the type of acid used and the type of clay. The acid-treatment process is often studied by varying the acid concentration, acid treatment time, and acid treatment temperature13–16. Acid activation of Pal induces cation leaching, causing alteration in the tetrahedral and octahedral sheets and leading to change in its microstructure. Cations Mg2+, Al3+, and Fe3+ are leached from the octahedron during acid treatment, resulting in their reduced content and an increase in Si4+ within the tetrahedral sheets. The reaction is proceeding with the continuous leaching of the octahedral cations, accompanied by structural evolution, which eventually destroys the rod morphology17. Acid treatment of Pal eliminates mineral impurities, generate more active OH– groups on its surface, and increases its surface area and pore volume18. Boudriche et al. (2011) studied the impact of hydrochloric acid on the textural and surface properties of Pal. At low concentration of acid, the carbonate minerals are removed, resulting in an increase in the surface area and pore volumes of attapulgite. The morphology and the crystal structure of the Pal remain unchanged. Increasing acid concentrations beyond 3 M causes dissolution of Al+ 3 and Mg+ 2 from the tetrahedral and octahedral sheets, which leads to destruction of the chemical structure and formation of amorphous silica while preserving the original fibrous morphology19. Hussein et al. (2020) studied the impact of acetic acid type and concentration on the rheology properties of Pal. Pretreatment of Pal with acetic acid improves the properties and makes it appropriate for usage in drilling fluids20. The texture of Pal clay has a variety of morphological fibre features. This study aims to investigate the morphology of raw Pal, evaluate the impact of acid pretreatment on its crystal structure, with a specific focus on its application in Cu adsorption. To comprehend the processes of morphological change and crystal behavior as a result of acid treatment, one must have an understanding of textural and structural differences. By utilizing analytical techniques such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray fluorescence (XRF), particle size distribution (PSD), and zeta potential analysis, this study provides new insights into the relationship between acid-induced modifications and the adsorption efficiency of Pal. Furthermore, the research uniquely explores Pal from the Bahir Al Najaf deposit, contributing valuable knowledge about its potential for industrial and environmental applications.

Materials and methods

Bulk pal collection

Bulk Pal was collected from a deposit in Bahr Al- Najaf area in the central part of Iraq about 170 km southwest of Baghdad (32°00′00″N 44°20′00″E). Bahr Al-Najaf (Sea of Al-Najaf) is considered one of the key wetlands in Iraq that is in the lower parts of Iraq, in a region called the Middle Euphrates to the west of the Euphrates River, and 2 km west of Al-Najaf city21. The samples were collected in the mine area at the same thickness of the clay layer (2 to 5 m in the vertical section), distanced by 2 m in the horizontal Sect. 10 bulk samples (5 kg each) were collected using hoe and shovel and then were packed in plastic bags. Bulk samples were dried at 110∘ C to remove moisture water. Then, they were mechanically ground, powdered in a ball mill, and passed through a 75 mesh. An equal proportion of bulk samples (5 kg) was mixed and homogenized to form a single representative sample that was used for all the tests.

Mineralogical and chemical characterization of pal

The diffractograms were obtained from a LabX Shimadzu XRD-6000 diffractometer using a copper anode with 2θ scan in the range of 2–60° with a scan speed of 0.02 ° 2θ/s. The pattern of XRD was compared with X-ray reference patterns for the identification of the different minerals, Identification of mineralogical components of Pal type was carried out applying the protocol established by Thorez22. Chemical analyses of Pal were accomplished by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) using a Magix Pro Philips PW2440 instrument. morphological of Pal samples was analysis using the scanning electron microscope (SEM) (JEOL JSM 6390 LV) and HITACHI S-4160 Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FESEM). Particle Size Analyzer provided with 90Plus particle sizing software Ver. 5.34 was utilized to display the distribution of Pal. particle size before and after acid treatment. An electrophoresis analyzer with an accuracy of 54.1 mV was used to determine the Zeta potential of the Pal samples. This was accomplished by first dispersing the samples in anhydrous ethanol using ultrasonic agitation at room temperature. Then, they were injected into the sample cell.

Acid pretreatment

Crushed Pal was treated with 0.832 M acetic acid (at solid/ liquid ratio 1/10) for one hour at 800 rpm using a Heidolph electrical stirrer of type RZR2041 to remove all calcite mineral without affecting the structure of the Pal. The resulting suspension was rinsed with distilled water until the pH reached 7. The quartz mineral was then extracted using a wet sieving operation with a 50 μm mesh size. The resultant clay was then dried at 110◦ C for 3 h.

Pal also, was pretreated with hydrochloric acid at concentrations of 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 6 M at room temperature for one hour. HCl treatment procedure was implemented using a reflux system while this system was impeded at a water bath for greater temperature control. The treated Pal was then dried at 110◦ C for 3 h after being rinsed with distilled water until the pH reached 7 and sieved with a 38 μm mesh size.

Preparation of heavy metal solution

1 g of [Cu(NO3)2.2H2O] was dissolved in 1 litter of distilled water at room temperature using an electromagnetic stirrer to produce [Cu(NO3)2.2H2O] solution (copper solution 338 ppm). The mixture is continuously stirred until there are no visible solid particulates at the bottom of the conical flask.

After that 0.1 g of pretreated Pal was added to 50 ml of [Cu (NO3)2.2H2O] solution with a mixing time of 15 min. Pal was then separated from the solution using a 4000 rpm centrifuge. The resulting solution was used in an atomic adsorption test to examine the concentration of copper in the remining solution. while the separated clay was desiccated at 110° C for 6 h in preparation for other required tests.

Result and discussion

Chemical characterization of pal

Table 1 lists the chemical components of raw Pal (R-Pal) and after acid treatment. The primary oxides present in Pal include SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3, MgO and CaO. Among these, SiO2 and Al2O3 are the most abundant oxides commonly found in clay minerals. To determine the change in Pal structure after being treated with varying doses of acid, a quantitative analysis of the elemental composition of the clay after treatment will be required. The development of the element percentages in relation to acetic acid and hydrochloric acid, as Table 1 presents: the percentage of Si increases, whereas the percentages of Ca+ 2, Mg2+, Al3+, and Fe3+ decrease. This reduction was attributed to the partial treatment of the octahedral sheets, which contained Mg2+, Al3+, and Fe3+ cations. During the acid treatment, Mg2+, Al3+, and Fe3+ in the octahedron are leached, leading to a reduction in their concentration, and the proportion of Si elements in the tetrahedron is increased5. Ca+ 2 reduction is attributed to dissolution of carbonated impurities, especially calcite, and the removal of metal-exchange cations (Ca+ 2)12,18,20. As the reaction proceeds, the octahedral cations are continuously washed away, which changes the structure of Pal. Over time, acid treatment destroys the morphology of the Pal rod5. The decrease in Ca+ 2 content after acid treatment (acetic acid or hydrochloric acid) confirms the previous studies, that carbonate impurities are almost entirely removed at 1 M acid, while the slight decrease in Mg2+, Al3+, and Fe3+ content demonstrates that the raw Pal can be purified in this manner. Lilya et al. (2011) report similar findings on Pal characteristics following treatment with 1 M HCl19.

Table 1.

The chemical composition of raw pal (R-Pal) and after treated with acetic acid and hydrochloric acid.

| Wt.% | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | NaO | K2O | TiO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R- Pal | 50.1 | 12.2 | 6.8 | 21.3 | 8.1 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 1.1 |

| After acetic acid at 0.832 M | 66.1 | 11.9 | 6.7 | 2.3 | 7.8 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 1.1 |

| After 0.5 M HCl | 69.6 | 11.1 | 6.6 | 1.6 | 7.0 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.0 |

| After 1 M HCl | 71.5 | 10.7 | 6.6 | 0.3 | 7.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.0 |

| After 2 M HCl | 73.8 | 9.7 | 6.2 | 0 | 6.8 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| After 4 M HCl | 75.5 | 9.2 | 5.9 | 0 | 6.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| After 6 M HCl | 77.2 | 8.9 | 5.1 | 0 | 5.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

The qualitative analysis shows that Pal constitutes 9.9% of the total and illite for 8.3% (Table 2). Illite mineral is the most common clay mineral associated with the Iraqi Pal deposits23. Within Pal, calcite and quartz are the predominant non-clay minerals, accounting for 37.8% and 25.7% of the total, respectively. Quartz and calcite are the predominant non-clay minerals found in Iraqi Pal deposits. Quartz is especially common in the fluvial and lacustrine deposits23.

Table 2.

The mineral composition of pal.

| Minerals | Calcite | Quartz | Palygorskite | Illite | Halite | Chlorite | Albite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wt. % | 37.8 | 25.7 | 9.9 | 8.3 | 3 | 6.3 | 9 |

X-ray diffraction analysis of pal

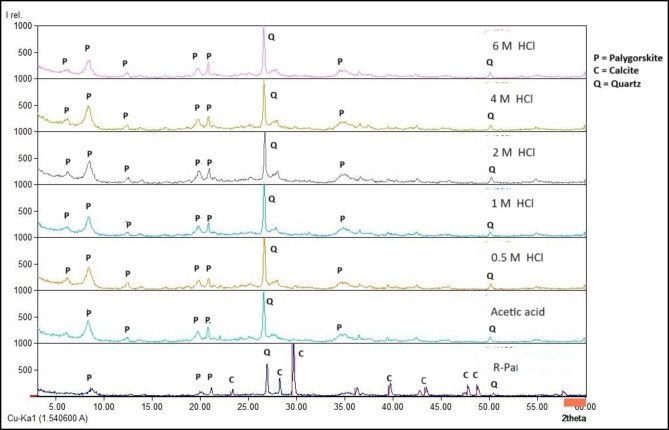

An X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns showed the major phases representative of R-Pal at peak in 2θ = 8.43, 20.1, 21.1, 23.3, 29.6, 34.9, 35.2 ,36.2 and 43.4 (Fig. 1) with d space 10.47, 4.4, 4.2, 3.8, 3, 2.56, 2.54, 2.47 and 2.08 A˚ which is a typical signal of Pal24. The typical diffraction peak in 2θ = 8.4 can confirm the presence of the Pal plane crystal face25,26. The peaks in 2θ = 8.43 and 29.6 indicate a monoclinic symmetry with C2/m space group1. As minor phases, XRD patterns showed the presence of calcite was also detected at the strong peak 2θ = 28.2, besides quartz peak at 2θ = 26.9.

Fig. 1.

XRD for R-Pal and after treated with acid.

Treatment of the Pal sample with acetic acid gives no significant shift in the Pal peaks. However, after one hour of acetic acid treatment, the strong reflection at 8.43 slight changed to 8.45 with a d space of 10.45 A˚. New weak reflections appear at 6.2 and 7.8, 12.4 and 13.6 and 13.9 and 22.07 with d space of 14.19, 11.32, 7.08, 6.46, 6.33 and 4.02 A˚. Acetic acid treatment gives further increases in the intensity of the weak peaks at 20.1, 21.1, 35.2 and 36.2 and shows a slight shift to 19.7, 20.8, 35.4 and 36.6 with d space of 4.48, 4.25, 3.49 and 3.34 A˚. Beyond this value, increasing in the peak intensity of quartz with a shift to 26.6 A˚ suggests that quartz is unaffected by the acid. Reduction in the peak intensity of calcite; complete removal of the impurities was not achieved because of the fibrous and strongly matted nature of the clay mineral.

Hydrochloric acid pretreatment gives a shift of some Pal peaks and increases in intensity compared with R-Pal; on treating the clay samples with 0.5 M HCl for one hour, the strong reflection at 8.4 increases appreciably in intensity with a slight shift to 8.54. This finding contradicts the findings of Lilya et al. (2011), who observed that the XRD diffractogram of Pal remains unchanged after treated with 0.5 M HCl19. Following 1 M HCl treatment, the peak intensity of Pal has increased substantially with a slight shift to 8.5. There is a noticeable increase in weak peaks at 2Ɵ = 20.1, 21.1, 35.2 and 36.2 with a slight shift to 19.8, 20.8, 34.8 and 36.5, A new weak peak located at 2 θ = 6.6, 12.3, and 13.7.

For 2 M HCl, Pal reflection peak at 8.4 has increased noticeably in intensity compared to raw clay without shifting, and weak additional reflection peaks form at 6.6, 12.4 and 13.7. A weak peak intensity at 2Ɵ= 20.1, 21.1, 35.2 and 36.2 increased with a slight shift to 19.9, 20.9, 34.6 and 36.6.

following 4 M HCl, the intensity of the strong peak at 8.4 increases to a level that is nearly equal to the intensity when treated with a 0.5 M HCl concentration without shifting. Weak peaks at 20.1, 21.1, 35.2 and 36.2 increased with a slight shift to 19.9, 20.9, 34.6 and 36.6. For 6 M HCl, the strong diffraction peak at 8.4 increased without shifting to a level was less than the intensity when treated with 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 M. Stronger acid or increasing the acid concentration to Pal treatment led to more significant changes in the intensity of reflections of Pal. Increasing the intensity of XRD reflections after acid treatment due to the shorter rods and lower crystallinity of the Pal sample19. The broadened band (between 5 and 36 A˚) corresponds to the loss of crystallinity and formation of an amorphous silica phase, insoluble in acid medium, generated by the dissolution of octahedral sheet in Pal under acid treatment18. Boudriche et al. (2011) have reported similar results on Pal, with 3 M HCl19. Pal according to the results of this study, has a layered structure with channels running along its fibres. Impurities, such as calcite, can be dissolved by acid treatment, which increases the Pal surface area and reveals previously concealed crystalline areas, resulting in new weak reflections in the XRD pattern. Increasing the acid concentration, which in turn increases the removal of impurities that had previously hidden the signal from the less strong crystalline phases. Acid treatment can enhance the crystallinity and preferred orientation of Pal. Once these obstructions are removed, the X-rays are able to interact with the smaller crystallites or less common phases more efficiently, resulting in a more clearly signal and stronger peak intensity.

Particle size

The particle size and particle size distribution are very critical factors for performance evaluation of raw and acid treated clay particles. Significant variations are observed in particle size and particle size distribution after treatment with acetic acid and hydrochloric acid (0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 6 M). Table 3 shows R-Pal and acid treated Pal particles with their median (D50), mean (Dav), skew and polydispersity index (PDI index).

Table 3.

Particle size distribution of R-Pal and acid treated pal.

| Median D50 |

Mean log Dav |

Mean Dav(skw) |

Skew | Effective diameter | Polydispersity index (PDI index) | GSD, geometric standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-Pal | 81.9 nm | 94.1 | 70.8 | -2.67 | 81.9 nm | 0.322 | 1.696 |

| Acetic acid | 54.7 | 59.5 | 47.3 | 0.002 | 54.7 | 0.189 | 1.510 |

| HCl 0.5 M | 49.6 | 49.7 | 33.7 | 2.09 | 49.6 | 0.005 | 1.073 |

| HCl 1 M | 39.7 | 39.8 | 28.7 | -0.05 | 39.7 | 0.005 | 1.073 |

| HCl 2 M | 46.0 | 46.2 | 31.4 | 0.42 | 46 | 0.005 | 1.073 |

| HCl 4 M | 63 | 63.1 | 50.9 | -0.20 | 63 | 0.005 | 1.073 |

| HCl 6 M | 44.9 | 45 | 25.5 | 1.07 | 44.9 | 0.005 | 1.073 |

Pre-treating samples with acetic acid generated decrease particle size to D50 of 54.7 and Dav 59.5 from D50 81.9 and Dav 94.1 for R-Pal. Table 3 showed further breakdown of Pal particles into smaller sizes following HCl pretreatment. Particle sizes D50 (49.6, 39.7, 46, and 44.9) and Dav (49.7, 39.8, 46.2, and 45) were demonstrated to decrease after treatment with HCl at concentrations of 0.5, 1, 2, and 6 M. Contrary 4 M HCl pretreatment had the opposite effect, D50 (63) and Dav (63.1) shifted into coarser sizes. Possible explanation: an abundance of fine grains that encouraged particle clustering. This can be verified by referring to the images obtained from the SEM analysis, as shown in Fig. 5. The untreated R-Pal sample exhibited a coarser particle size of 0.322 compared to the acid-treated clay samples. In general, all HCl-treated samples demonstrated decreased dispersion and exceptionally low polydispersity indices (PDI) of 0.005, suggesting a highly uniform particle size distribution. In contrast, acetic acid-treated samples displayed a broader particle size distribution, as shown by a PDI of 0.189. PDI serves as a quantitative measure of particle size heterogeneity within a sample. A lower PDI corresponds to a more uniform particle size distribution, while a higher value implies greater variability27. Skewness expresses the degree of asymmetry of a polydispersity particle size PSD in comparison to a normal distribution28. Skewness is an additional measure of grain-size sorting that reflects sorting in the tails of the distribution29. Acetic acid pretreatment decreased particle size and influenced size distribution to near symmetry (0.002) and Dav (skew) 47.3. In contrast, HCl pretreatment induced varying degrees of particle size reduction and skewed distributions. Treatment of Pal with 0.5 M or 4 M HCl produced a strongly fine-skewed distribution (skew 2.09, 1.07 and Dav (skew) 33.7, 25.5). A fine-skewed distribution is seen at 2 M HCl (skew 0.42 and Dav (skew) 31.4), while IM HCl shows near symmetrical (skew − 0.05) and Dav (skew) 28.7). Sample with 4 M HCl revealed a drastic shift to strongly coarse skewed (skew − 0.20) and Dav (skew) 50.9). R-Pal is exhibited a strongly negatively skewed (coarse) (skew − 2.67) and Dav (skew 70), indicating a predominance of larger particles. Overall, acid pretreatment, particularly at lower concentrations, shifted the particle size distribution towards finer particles or positively skewed and increased homogeneity.

Fig. 5.

Effect of acid treatment of Pal on Cu adsorption.

Grain size distribution (GSD) refers to a statistical and graphic parameter, including special sizes such as D10, D30, and D60; coefficients of sorting, uniform and curvature; and skewness. These are strongly dependent on the probability distributions. A low GSD value for Pal indicates a low degree of particle aggregation, suggesting a more uniform sample30.

All the samples that were treated with HCl exhibit a GSD value of 1.073, suggesting a relatively low degree of particle aggregation. The two samples R-Pal and acetic acid show values 1.696 and 1.510 indicate a high degree of particle aggregation and broader particle size distributions. The differences in GSD values for untreated Pal and acid treated pal due to acid processing.

In the current study, acetic acid pretreatments caused incomplete dispersion, while HCl pretreatments caused complete dispersion, resulting in the formation of monodisperse particles. Schulte et al. (2016) observed that HCl pretreatment is particularly selective; carbonates are dissociated and extracted from Pal samples when HCl is added31. The HCl treatment mainly changed the relative amount of calcite, resulting in a greater change in particle size distribution than the acetic acid treatment (Fig. 1). The difference in particle size between samples with acid pretreatment and R-Pal that contained a high amount of calcite was distinct and like the results reported by Koza et al. (2021)32.

SEM and FESEM analysis of pal

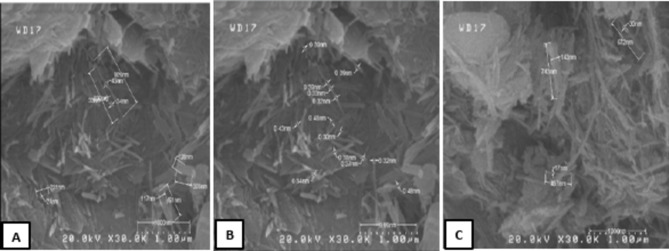

The fibrous morphology of Pal is its main characteristic and has been described since the first studies of this mineral. Several terms have been used to name the particles and the aggregates, such as fibre, lath, rod, bundle, tape, and strip. Garcı´a-Romero and Sua´rez (2013) proposed a simple nomenclature that is not only descriptive but also has a crystallographic element: lath, rod, and bundles. Lath is an individual crystal, and the fibre length ranges from centimetres (macroscopic) to less than 1 μm33. A rod is formed by several Pal crystals, and a bundle is a group of laths or rods that are parallel to a fibre axis. SEM images reveal the alterations in the microstructure and morphology of Pal.

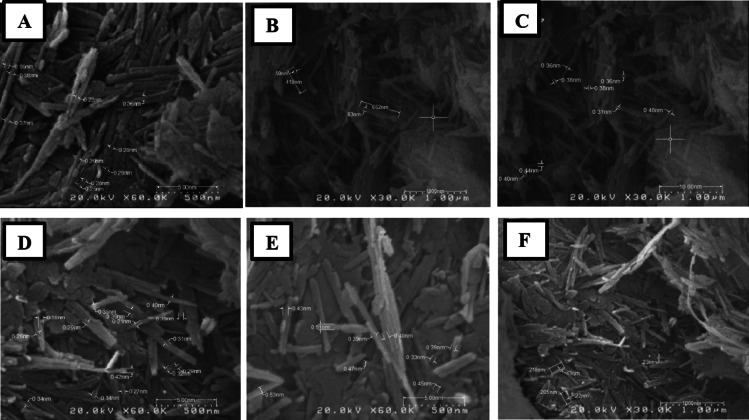

Figure 2 (A, B, and C) displays the R-Pal sample; the fibres are randomly stacked and intricately intertwined. Most of the time the fibres seen are in bundles; occasionally they take the form of rods or even laths (Fig. 2 (A and B)). The longer fibres show clear signs of bending or curling (Fig. 2C). Figure 2B shows that the R-Pal has a fibrous appearance, with fibres (lath) ranging in width from 30 to 48 nm and an average length less than 1 μm (929 nm). The fibres consist of smaller fibres that form rods and bundles, as shown in Fig. 2A. The R-Pal exhibits a fibrous morphology Characterized by aggregated rods and bundles. Pal Bahr Al-Najaf was formed by the transformation of smectite and illite-smectite. Short and thin fibres characterize this kind of Pal23. Pal aggregation can be caused by carbonate impurities, and the acid treatment disperses these flakes. A typical crystalline inclusion was observed in the R-Pal sample, which could be attributed to the presence of carbonated impurities (Fig. 2C). Based on the XRF analysis of raw Pal (Table 2), the calcite mineral content is determined to be 37.8%. Figure 3A and B show a SEM micrograph of the Pal treated with acetic acid 0.832 M and 0.5 M HCl (Fig. 3C, D, and E). It can be observed that the process keeps the fibrous morphology of Pal unchanged compared with R-Pal; most carbonate impurities have disappeared, leaving holes in the fibrous solid. Also, the aggregates of fibre were dispersed.

Fig. 2.

SEM of the R-Pal sample.

Fig. 3.

SEM and FESEM of treated Pal acetic acid (A and B), 0.5 M HCl (C–E) and 1 M HCl (F–H).

Fibres disaggregated because more carbonate impurities were removed following treatment with 1 M HCl (Fig. 3F, G, and H). The agglomerates of fibres were dispersed include straight fibres, rods and bundles with different sizes. At 500 nm, it is possible to observe softly bending or curling in certain elongated laths or rods. The rods demonstrate diminished randomization and align themselves in specific orientations and tend to assume the shape of rods and bundles when treated with 2 M HCl (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the rods exhibit minute fractures that are discernible at 500 nm. After being processed with 4 M HCl, it was discovered that the laths and rods exhibited a propensity to cluster and agglomerate (Fig. 4B and C). Based on the results of the particle size analysis Pal particles have a larger average size (D50-63.1 and Dav-63.1) compared to other acid treatments. The mechanism behind Pal agglomerate is the flocculation of negatively charged separates32. The existence of aggregates has an adverse effect on the physical and chemical properties of clay minerals19. Pal treated with 6 M HCl (Fig. 4D, E, and F). exhibited four main morphological changes: rod microfractures and roughness, fibres that tended to take on rod and bundle shapes, and, regardless of fibre length, bending or curling of some fibres. According to a study by García-Romero and Suárez (2013), fibres that are softly curled can correspond to small fibres, intermediate fibres to macroscopic fibres33. This suggests that the curl is not related to the size of the fibre.

Fig. 4.

SEM and FESEM of treated Pal with 2 M HCl (A), 4 M HCl (B and C) and 6 M HCl (D–F).

Pal may appear either as dense fibre masses that are connected to one another to form a dense lattice (closed porosity) or as grown-out fibres (open porosity), which resemble sticks. The fibres usually get covered by other fibres, particularly those that are longer and curlier, while impurities minerals, particularly calcite, aggregate, thereby decreasing the surface area33. Acid treatment reduces the impurities and buildup of entangled fibres by removing the calcite and releasing the fibres. It is important to mention that the fibrous morphology is still maintained following acid treatment 0.5, 1, 2,4 and 6 M.

Gonzalez et al. (1989), studied the effects of a strong treatment with 5 M HCl on the fibrous shape of the Pal. A silica gel was generated after activation with 5 M HCl. This gel has the potential to act as a protective covering while preserving Pal fibrous shape34. HCl pretreatment affects clays is dependent on their mineral structure. there are two structure units that are present in all clay, and these are tetrahedral and octahedral sheets. Depending on the cation/anion ratio, the octahedral sheets can be categorized as dioctahedral or trioctahedral35. When clay minerals are treated with HCl, the octahedral sheet loses exchangeable cations and Al, Mg, and Fe, whereas the SiO4 groups in the tetrahedral sheets are mostly intact36. The main effect of HCl on the clay mineral structure is the corrosion of the octahedral sheets. The dissolution rate of trioctahedral layers is much higher than that of dioctahedral layers35. The greater substitution of Mg2+ and/or Fe3+ for Al3+ in dioctahedral increases their dissolution rate in HCl37.

Pal can contain amorphous phases or areas that are poorly ordered. Amorphous areas can obfuscate weaker peaks and contribute to background noise in the XRD pattern. In the current study, XRD results show that acid treatment at varying concentrations for 1 h improves Pal crystallinity through removing impurities and minerals that obscured the weaker crystalline phases signals. Once these obstructions are removed, the X-rays are able to interact with the smaller crystallites or less plentiful phases more efficiently, resulting in a brighter signal and higher peak intensity. Furthermore, SEM images reveal that Pal fibres remain intact after acid treatment, but microfractures and roughness of Pal rods manifest after 6 M HCl. This suggests that the rods were released during acid treatment and that a strong acid treatment (6 M for 1 h) did not result in the formation of silica gel that covers Pal fibres.

Zeta potential

Zeta potential analysis of Pal is illustrated in Table 4. The negative charge of R-Pal is due to the hydroxyl groups that are exposed on the surface of Pal. Besides, the proportion of Si4+ in tetrahedral is replaced by Al3+, generating excess negative charges38.

Table 4.

Zeta potential of pal samples.

| Sample | R-Pal | Pretreatment of pal with acid | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetic acid | 0.5 M HCl | 1 M HCl | 2 M HCl | 4 M HCl | 6 M HCl | ||

| Zeta potential (mV) | − 10.6 | 54.82 | 60.65 | 61.14 | 77.09 | 22.68 | 12.52 |

Following acid treatment, Table 4 shows that the zeta potential converted from negative to positive on the acid treated Pal surface. The value of the zeta potential of the pal samples exhibits an increase in positive value with an increase in acid dose, followed by a decrease. Specifically, the value of the zeta potential of pal pretreatment with 2 M HCl is higher than 1 M HCl, 0.5 M HCl, and acetic acid, respectively. Among the samples, the positive zeta potential value of 2 M HCl by 77.09 is the highest.

Acetic acid treatment removed carbonate impurities, increased surface area, and exposed more negative charges and hydroxyl groups. The acid solution transformed the hydroxyl groups (Si-OH) on the surface of Pal into oxonium ions (Si-OH2+). This made the zeta potential positive.

The use of HCl results in removal of more carbonate impurities and exposes more hydroxyl groups, thus leading to more positive zeta potential compared to acetic acid. In addition, the removal of exchangeable cations on the Pal surface and replacement by H ions increases the positive charge on the Pal surface and increases the positive zeta potential. Increasing acid concentrations to 2 M HCl results in a more notable shift in zeta potential. Acid could dissolve alumina and silica from the Pal structure, exposing positively charged sites on the clay surface.

On the other hand, the positive zeta potential reduced by 22.68 and 12.52 when the concentration of HCl was increased to 4 M and 6 M HCl respectively. According to SEM, increasing the concentration of acid resulted in increased aggregation of Pal fibres; these fibre agglomerates led to a decrease in surface area, which led to a noticeable decrease in the zeta potential.

Effect of acid treatment of pal on Cu adsorption

Table 5 illustrates the effectiveness of Pal in removing Cu ions from solution. The influence of various factors, including type of acid, HCl concentration, mixing time, and temperature, on Cu removal efficiency was examined.

Table 5.

Effect of acid treatment of pal on Cu Adsorption at different temperature and mixing time (hour) (AC = acetic acid 1 M) (HCl = 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6 M) (Cu ppm = concentration of Cu in solution) (initial Cu concentration in solution = 338 ppm).

| Pal | Room temperature | 50 °C | 60 °C | 70 °C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu ppm | Time h | Cu ppm | Time h | Cu ppm | Time h | Cu ppm | Time h | |

| R-Pal | 298.4 | 1 | 295.9 | 1 | 294.5 | 1 | 294.1 | 1 |

| 0.832 M AC | 277.2 | 1 | 273.8 | 1 | 272.9 | 1 | 272.1 | 1 |

| 0.5 M HCl | 212 | 1 | 197.8 | 1 | 225 | 1 | 182.9 | 1 |

| 0.5 M HCl | 220 | 2 | 201.6 | 2 | 213.2 | 2 | 193.2 | 2 |

| 0.5 M HCl | 216 | 4 | 210.6 | 4 | 220.4 | 4 | 195.9 | 4 |

| 0.5 M HCl | 212 | 6 | 214.8 | 6 | 218.6 | 6 | 205.3 | 6 |

| 1 M HCl | 214 | 1 | 204.5 | 1 | 231.2 | 1 | 229.1 | 1 |

| 1 M HCl | 205 | 2 | 206.9 | 2 | 223.8 | 2 | 220.7 | 2 |

| 1 M HCl | 228 | 4 | 200.2 | 4 | 221.3 | 4 | 232.4 | 4 |

| 1 M HCl | 210 | 6 | 211.1 | 6 | 218.9 | 6 | 232.9 | 6 |

| 2 M HCl | 220 | 1 | 201.7 | 1 | 216.1 | 1 | 230.4 | 1 |

| 2 M HCl | 213 | 2 | 205.1 | 2 | 219.4 | 2 | 232.4 | 2 |

| 2 M HCl | 215 | 4 | 209.4 | 4 | 208.6 | 4 | 232.8 | 4 |

| 2 M HCl | 193.4 | 6 | 196.3 | 6 | 211.4 | 6 | 248.3 | 6 |

| 4 M HCl | 220 | 1 | 197.4 | 1 | 213.1 | 1 | 230.9 | 1 |

| 4 M HCl | 220 | 2 | 197.4 | 2 | 223.5 | 2 | 230.5 | 2 |

| 4 M HCl | 214 | 4 | 195 | 4 | 216.1 | 4 | 229.2 | 4 |

| 4 M HCl | 215 | 6 | 200.6 | 6 | 213.3 | 6 | 235.4 | 6 |

| 6 M HCl | 215 | 1 | 192.6 | 1 | 208.9 | 1 | 242.6 | 1 |

| 6 M HCl | 217 | 2 | 194.8 | 2 | 204.4 | 2 | 235.5 | 2 |

| 6 M HCl | 218 | 4 | 204.2 | 4 | 208.7 | 4 | 233.4 | 4 |

| 6 M HCl | 217 | 6 | 205.5 | 6 | 207 | 6 | 230.5 | 6 |

R-Pal reduces Cu concentration from 338 ppm to 298.4 ppm at room temperature after 1 h of mixing. 0.832 M acetic acid-treated Pal improves Cu removal to 277.2 ppm at room temperature. Both raw and acetic acid treated Pal are effective in removing Cu from solution. Acetic acid treatment significantly enhances the Cu removal efficiency of Pal. Increasing temperature from room temperature to 50, 60, and 70 °C did not significantly impact Cu removal by either raw or acetic acid-treated Pal. Pre-treating of Pal with HCl includes different concentrations of 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 6 M and a mixing time of 1, 2, 4, and 6 h at room temperature, 50, 60, and 70° C. HCl treated Pal samples were subsequently utilized for Cu adsorption, as shown in Table 5 and Fig. 5. The primary decrease in Cu concentration occurred following Pal treatment with a low concentration of HCl, specifically 0.5 M. The Cu concentration in solution reduced from 338 ppm to 212 ppm, 197.8 ppm, 225 ppm and 182.9 ppm over 1 h of mixing at room temperature, 50, 60 and 70° C, respectively. Despite the variability of influence, increasing the HCl concentration applied to the Pal resulted in lower final Cu ppm values, suggesting improved efficiency in Cu removal from the solution. There is a general trend for decreasing Cu concentrations over time; however, the impact is not consistently uniform. The impact of temperature on Cu removal is less clear-cut and seems to vary depending on the HCl concentration and mixing time.

Effect of acid treatment of pal structure

Pal has unique physicochemical properties4. This characteristic can be attributed to its fibrous rod shape and nanopore structure; therefore, Pal is widely applied as an adsorption5.

R-Pal exhibited a fibrous morphology with randomly stacked and intertwined fibres; carbonate impurities interfere with the natural arrangement of these fibres. These impurities act as binding agents, leading to the aggregation of Pal fibres into bigger clusters and thereby diminishing the Pal surface area. The particle size distribution of R-Pal exhibited a strong negative skewness (-2.67), indicating a predominance of larger particles. The negative zeta potential of R-Pal (-10.6) suggests a greater abundance of negative charges compared to positive charges on the Pal surface. Cu ions interact chemically with functional groups on the Pal surface, such as hydroxyl groups (-OH), to form bonds or complexes. Cu ions also exchange with other cations present on the Pal surface (Ca2+) or inside the fibre structure6. The decreasing concentration of Cu reflects the electrical potential at the interface between charged Pal particles and the Cu leading to their adsorption. To enhance the properties of Pal, acid pretreatment has been undertaken to adjust the structure and surface qualities. The acetic acid treatment maintained the fibrous morphology of Pal, similar to that of R-Pal. The removal of carbonate impurities led to the dispersion of fibre aggregates and the creation of voids within the fibrous structure. Additionally, the particle size decreased, leading to a more symmetrical size distribution. The zeta potential of 54.82 indicates that the acetic acid treatment changed the Pal surface to a positively charged state. This positive surface charge obstructs the chemical interaction and cation exchange involving Cu ions and the Pal surface. Despite the positive surface charge, the adsorption of Cu improved and increased compared to R-Pal. The adsorption of Cu occurred within the micropores of the fibrous structure, while electrostatic interactions also played a role in the adsorption process6. The treatment of Pal with 0.5 M HCl preserved its fibrous morphology while effectively removing calcite impurities. This process resulted in the formation of voids within the fibrous structure and dispersed the fibres agglomerated. While the surface of Pal becomes positively charged after acid treatment, Cu ions are still attracted to the Pal. The adsorption of Cu occurs within the micropores of the fibrous structure, with electrostatic interactions also playing a role in the adsorption process. This suggests that the micropores act as absorption sites for Cu ions. The small size of these pores allows for selective adsorption of specific ions, hence enhancing it in comparison to R-Pal and acetic acid treated Pal. Following treatment with 1 M and 2 M HCl, more fibres were released due to most carbonate impurities that had been filling the pores of Pal being removed, which is consistent with the XRD and XRF. More positive charges were carried to the surface and fibrous structure of Pal; H + in the acid solution replaced cations in the Pal crystals. As a result, the zeta potential value of Pal increased to 61.14, and 77.09 respectively. The effectiveness of Pal in removing copper was comparable to that achieved with a 0.5 M HCl treatment. The treatment of Pal with HCl concentrations of 4 M and 6 M results in notable changes to its crystal structure and characteristics. The observed changes in XRD patterns indicate complete dissolution of impurities, as well as changes in the intensity and position of diffraction peaks of crystal structures. Acid attacks the octahedral sheets, resulting in a decrease of crystallite size. Additionally, there is a loss of crystallinity and the formation of an amorphous silica phase. These structural changes contributed to the observed changes in zeta potential and decreased to 22.68 and 12.52, respectively. Despite the structural change, Pal retained its efficacy in removing Cu ions. This suggests that the acid treatment process, even at elevated concentrations, did not significantly impair Pal adsorption capacity compared to that achieved with 0.5 M HCl treatment.

Increasing the mixing time and temperature can influence the adsorption process, and effect on Cu removal from solution in current study was less significant effect on adsorption. Adsorption is a dynamic process; as the contact time between the two phases of the adsorption system increases, the amount of Cu ions retained on the adsorbent materials increases39. This increase is more pronounced in the initial stage and depends on the nature of the adsorbent material16. Cu ions need to diffuse to the surface and micropores of the Pal to be adsorbed. Increasing mixing time can enhance diffusion and then increase the adsorption. Results show that there appears to be no trend indicating an increase in Cu removal with increasing mixing time and acid concentration. The effect of temperature on the adsorptive effectiveness of Pal is more complex. In some cases, higher temperatures lead to increased adsorption, while in others, there is little or no effect. The adsorption of Cu with R-Pal and acetic acid-treated Pal showed a slight increase with temperature.

At room temperature, the findings indicate that an increased mixing time led to fluctuations in Cu removal with 0.5 M and 1 M HCl-treated pal, while Cu removal with 2 M, 4 M, and 6 M HCl-treated pal decreased. At 50 °C, the adsorption of HCl-treated pal shows fluctuations in Cu removal as time progresses, whereas increasing the temperature to 60 and 70 °C results in a decline in Cu removal. Higher temperatures affect the solubility of Cu compounds and the properties of Pal, influencing its adsorption capacity. At high temperatures, the diffusion rate of molecules in the adsorbent decreases. Therefore, the adsorption will slow down, and the surface coating will decrease from repulsion16. This suggests that Cu ions adsorbent by Pal decrease or are released back into solution over time as the temperature increases.

Conclusions

R-Pal exhibited a fibrous morphology with randomly stacked fibres with positive surface charge. Impurity minerals act as binding agents, leading to the aggregation of Pal fibres into bigger clusters and decreasing the surface area. To enhance the properties of Pal, acid pretreatment has been undertaken to adjust the structure and surface qualities.

Treatment with acetic acid maintained the fibrous morphology of Pal and dispersed the fibre aggregates, creating voids within the fibrous structure and decreasing particle size. The treatment with 0.5, 1, and 2 M HCl kept the morphology of Pal fibres, dispersed the fibres agglomerated, and raised the positive surface charge. Treatment of Pal with 4 and 6 M HCl resulted in notable changes to its crystal structure and the formation of an amorphous silica phase. The structural modifications resulted in a reduction of positive zeta potential.

Cu removal efficiency enhanced from 298.4 to 277.2 ppm after treating Pal with acetic acid. The primary decrease in Cu concentration occurred following Pal treatment with 0.5 M HCl, resulting in a reduction in the level of Cu in solution to 212 ppm. Increasing temperature from room temperature to 50°, 60°, and 70° C did not significantly impact Cu removal by either raw or acid treated Pal.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

M.A. and A.F. wrote the main manuscript text and A.A. prepared figures and tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript.”

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nefzi, H., Abderrabba, M., Ayadi, S. & Labidi, J. Formation of Palygorskite Clay from treated Diatomite and its application for the removal of Heavy metals from Aqueous Solution. Water10 (9), 1257. 10.3390/w10091257 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi, T. et al. Calcined Attapulgite Clay as supplementary cementing material: Thermal Treatment, Hydration Activity and Mechanical properties. Int. J. Concrete Struct. Mater.16 (10). 10.1186/s40069-022-00499-8 (2022).

- 3.Guggenheim, S. & Krekeler, M. P. S. The structures and microtextures of the palygorskite–Sepiolite Group minerals. Developments Clay Sci.3 (2013).

- 4.García-Rivas, J., del Sánchez, M., García-Romero, E. & Suárez, M. An insight into the structure of a palygorskite from Palygorskaja: some questions on the standard model. Appl. Clay Sci.148, 39–47 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu, Y., Wang, W., Wang, Q., Xu, J. & Wang, A. Effect of oxalic acid-leaching levels on structure, color, and physico-chemical features of palygorskite. Appl. Clay Sci.183, 105301. 10.1016/j.clay.2019.105301 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Bidry, M. A. & Hamed, R. S. Utilizing Attapulgite as Anti-spill Liners of Crude Oil. Baghdad Sci. J.19 (3), 0693–0693. 10.21123/bsj.2022.19.3.0693 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiang, Y. B. et al. Fabrication of a pH responsively controlled-release pesticide using an attapulgite-based hydrogel. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng.6 (2), 1192–1201 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marrakchi, F., Khanday, W. A., Asif, M. & Hameed, B. H. Cross-linked chitosan/sepiolite composite for the adsorption of methylene blue and reactive orange 16. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.93, 1231–1239. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.09.069 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu, Y. S. et al. A comparative study of different natural palygorskite clays for fabricating cost-efficient and ecofriendly iron red composite pigments. Appl. Clay Sci.167, 50–59 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ouyang, J., Zhao, Z., Suib, S. L. & Yang, H. M. Degradation of Congo Red dye by a Fe2O3@CeO2-ZrO2/Palygorskite composite catalyst: synergetic effects of Fe2O3. J. Colloid Interface Sci.539, 135–145 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding, J. J., Huang, D. J., Wang, W. B., Wang, Q. & Wang, A. Q. Effect of removing coloring metal ions from the natural brick-red palygorskite on properties of alginate/palygorskite nanocomposite film. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.122, 684–694 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sattar, A. & Al-Bidry, M. A. Activation and enhancement of the performance of Iraqi Ca-Bentonite for Use as Drilling Fluid in Iraqi Oil Fields. Iraqi J. Sci.61 (11). 10.24996/ijs.2020.61.11.18 (2020).

- 13.Jozefaciuk, G. & Bowanko, G. Effect of acid and alkali treatments on surface areas and adsorption energies of selected minerals. Clays Clay Miner.50, 771–783 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibrahim, A. S. & Al-Bidry, M. A. Activation of Iraqi bentonite for use as drilling mud. IOP Conf. Seri. Mater. Sci. Eng. 579(1), 012006. 10.1088/1757-899X/579/1/012006 (2019).

- 15.Al-Bidry, M. A. & Azeez, R. A. Removal of sulfur components from heavy crude oil by natural clay. Ain Shams Eng. J.11 (4), 1265–1273. 10.1016/j.asej.2020.03.010 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Bidry, M. A., Al-Najar, J. & Al-Wassity, A. Study of the characteristics of porcellanite rocks and their application as a sorbent for removing crude oil. Appl. Earth Sci.132 (2), 142–157. 10.1080/25726838.2023.2223942 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen, T. H., Feng, Y. L. & Shi, X. L. Study on products and structural changes of the reaction of palygorskite with acid. J. Chin. Ceramic Soc.31, 959–964 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cruz, K. M. et al. Effects of Acid Treatment on the Clay Palygorskite: XRD, Surface Area, Morphological and Chemical Composition. Mater. Res.17 (Suppl. 1), 3–8. 10.1590/S1516-14392014005000057 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boudriche, L., Calvet, R., Hamdi, B. & Balard, H. Effect of acid treatment on surface properties evolution of attapulgite clay: an application of inverse gas chromatography. Colloids Surf. A392, 45–54 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussein, A. F., Al Khalaq, A. & AL Wassity, A. A. Effect of acidic treatment on rheological properties of Iraqi Attapulgite clay. AIP Conf. Proc.2213, 020038–020031. 10.1063/5.0000344 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salim, M. A. & Abed, S. A. Avifauna Diversity of Bahr Al-Najaf Wetlands and the surrounding areas, Iraq. Jordan J. Biol. Sci.10 (3), 167–176 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorez, J. Practical Identification of Clay Minerals: A Handbook for Teachers and Students in Clay Mineralogy. Mineralogy Clay Belgium (1976).

- 23.Al-Bassam, K. S. Palygorskite deposits and occurrences in Iraq: an overview. Iraqi Bull. Geol. Min. Special IssueNo. 8, 203–224 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zotiadis, V. & Argyraki, A. Development of innovative environmental applications of attapulgite clay. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece. 47 (2). 10.12681/bgsg.11139 (2013).

- 25.Sheng, G. et al. Adsorption of pb (II) on diatomite as affected via aqueous solution chemistry and temperature. Colloids Surf. A339, 159–166 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 26.da Silva, M. L. D. G. et al. R., & da Silva Leite, C. M. Palygorskite organophilic for dermopharmaceutical application. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 115, 2287–2294 (2014).

- 27.Mudalige, T. et al. Characterization of nanomaterials: Tools and challenges. In Nanomaterials for Food Applications Micro and Nano Technologies, 313–353. 10.1016/B978-0-12-814130-4.00011-7 (2019).

- 28.Tascón, A. Influence of particle size distribution skewness on dust explosibility. Powder Technol.338, 438–445. 10.1016/j.powtec.2018.07.044 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boggs, S. Petrology of sedimentary rocks(2nd ed.), 595 (2009).

- 30.Li, Y., Huang, C., Wang, B., Tian, X. & Liu, J. A unified expression for grain size distribution of soils. Geoderma288, 105–119. 10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.11.011 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulte, P. et al. Influence of HCl pretreatment and organo-mineral complexes on laser diffraction measurement of loess–paleosol-sequences. CATENA137, 392–405. 10.1016/j.catena.2015.10.015 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koza, M. et al. Consequences of chemical pretreatments in particle size analysis for modelling wind erosion. Geoderma396, 115073. 10.1016/j.geoderma.2021.115073 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 33.García-Romero, E. & Suárez, M. Sepiolite–palygorskite: textural study and genetic considerations. Appl. Clay Sci.86, 129–144. 10.1016/j.clay.2013.09.013 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzalez, F. et al. Structural and textural evolution of Al- and Mg-rich palygorskites I: under acid treatment. Appl. Clay Sci.4, 373–388 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu, B., Zhang, C. & Zhang, X. The effects of Hydrochloric Acid pretreatment on different types of Clay minerals. Minerals12 (9), 1167. 10.3390/min12091167 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steudel, A., Batenburg, L. F., Fischer, H. R., Weidler, P. G. & Emmerich, K. Alteration of swelling clay minerals by acid activation. Appl. Clay Sci.44, 105–115 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steudel, A., Batenburg, L. F., Fischer, H. R., Weidler, P. G. & Emmerich, K. Alteration of non-swelling clay minerals and magadiite by acid activation. Appl. Clay Sci.44, 95–104 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu, J. et al. Study on the ball milling modification of attapulgite. Mater. Res. Express. 7, 115006. 10.1088/2053-1591/abc932 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lucaci, A. R., Bulgariu, D., Popescu, M. C. & Bulgariu, L. Adsorption of Cu(II) ions on adsorbent materials obtained from Marine Red Algae Callithamnion corymbosum sp. Water12, 372. 10.3390/w12020372 (2020). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].