Abstract

Background

Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is a leading form of non-small cell lung cancer characterized by a complex tumor microenvironment (TME) that influences disease progression and therapeutic response. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) within the TME promote tumorigenesis and evasion of immune surveillance, though their heterogeneity poses challenges in understanding their roles and therapeutic targeting. Additionally, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) offers potential anti-cancer agents that could modulate the immune landscape.

Methods

We conducted single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on LUAD samples, performing an in-depth analysis of macrophage populations and their expression signatures. Network pharmacology was used to identify TCM components with potential TAM-modulatory effects, focusing on Astragalus membranaceus. Pseudotime trajectory analysis, immunofluorescence staining, and in vitro assays examined the functional roles of TAMs and the effects of selected compounds on macrophage polarization.

Results

Our scRNA-seq analysis identified notable heterogeneity among macrophages, revealing predominant M2-like phenotypes within TAMs. Network pharmacology highlighted active TCM ingredients, including quercetin, isorhamnetin, and kaempferol, targeting genes related to macrophage function. Survival analysis implicated AHSA1, CYP1B1, SPP1, and STAT1 as prognostically significant factors. Further experiments demonstrated kaempferol’s efficacy in inhibiting M2 polarization, underlining a selective influence on TAM functionality.

Conclusions

This study delineates the diverse macrophage landscape in LUAD and suggests a pivotal role for STAT1 in TAM-mediated immunosuppression. Kaempferol, identified from TCM, emerges as an influential agent capable of altering TAM polarization, potentially enhancing anti-tumoral immunity. These findings underscore the translational potential of integrating TCM-derived compounds into immunotherapeutic strategies for LUAD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-025-01832-9.

Keywords: Lung adenocarcinoma, Macrophage heterogeneity, Tumor microenvironment, Single-cell transcriptomics, Kaempferol

Introduction

Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), a predominant form of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), presents a substantial global health burden, exhibiting high incidence and mortality rates [1, 2]. Despite advancements in therapeutic strategies, the prognosis for LUAD patients remains suboptimal, urging a continual quest for innovative treatment approaches [3, 4]. The intricate tumor microenvironment (TME) of LUAD is characterized by a dynamic interplay between various cell types, with immune cells, such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), playing critical roles in tumorigenesis, progression, and the response to therapy [5, 6].

TAMs, originating from circulating monocytes, are abundantly present within the TME and are known for their phenotypic plasticity [7]. Functionally, they are delineated into two polar states: the classical, pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype, and the alternative, angiogenic and immunosuppressive M2 phenotype [8, 9]. While M1 macrophages have been implicated in anti-tumoral responses, M2 macrophages facilitate tumor progression and metastasis by creating an immunosuppressive microenvironment conducive to tumor cell survival and evasion from immune surveillance [8, 9].

Recent breakthroughs in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) have provided unprecedented resolution into the cellular heterogeneity of the immune landscape in cancer, highlighting distinct macrophage subpopulations within the TME [10, 11]. These refined classifications of macrophages necessitate reevaluation of their functional contributions to the TME and the clinical course of LUAD.

Furthermore, the integration of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) into cancer therapeutics is gaining momentum, with numerous studies validating the anti-cancer properties of herbal constituents [12, 13]. Arglabin has demonstrated good anti-cancer properties in prostate cancer, indicating that active ingredients in traditional Chinese medicine can be used as anti-cancer drugs [14]. The potential of TCM compounds to modulate immune responses, particularly TAM polarization, offers an exciting therapeutic window that warrants extensive exploration [15]. Astragalus membranaceus is considered in traditional Chinese medicine to have the effect of enhancing the body’s immune system and is also used in modern times as an adjunct treatment for tumors [16, 17]. However, there are many active ingredients in Astragalus membranaceus, and it is not yet clear which specific ingredients are responsible for boosting the immune system and assisting in cancer treatment. Therefore, identifying the active ingredients in Astragalus membranaceus has become a problem that needs to be addressed.

In this study, we sought to construct a comprehensive single-cell transcriptomic atlas of LUAD, dissecting the cellular composition and perturbations within the TME, with an emphasis on TAM diversity and functionality. Additionally, we ventured to uncover pharmacologically active TCM compounds that target macrophage gene expression signatures, providing a bridge between traditional remedies and modern oncological practices. Pseudotime trajectory analysis and immunofluorescence validation were employed to interpret the functional states and polarization pathways of TAMs, while in vitro assays were conducted to assess the modulatory effects of identified TCM compounds on macrophage polarization.

Through systematic investigations, we aim to elucidate the role of macrophages in LUAD progression, introduce novel biomarkers for prognosis, and furnish evidence for the repurposing of TCM-derived compounds as potential immunomodulatory agents against LUAD. Through these efforts, we aspire to contribute to the growing repository of knowledge that could inform future strategies for the tailored management of LUAD.

Materials and methods

Single-cell data processing

Single-cell data of LUAD was obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), with accession ID GSE117570 and GSE198099 [18]. The raw data was stored in the standard data format by the data provider using 10X Genomics. We used the Seurat package for the entire analysis and processing of the single-cell data. The creatseuratobject function was used to generate the Seurat object. Since doublets had already been removed by the data provider, there was no need to perform doublet removal. Low-quality cells (nCount_RNA > 1000 & percent.mt < 30 & nFeature_RNA > 600) were removed using the subset function. All samples were integrated into one Seurat object using the merge function, and the harmony package was utilized to remove batch effects. All cells were clustered into different cell subpopulations at a resolution of 0.4. Based on the paper by the data uploader and considering the situation of cell clustering, we ultimately determined a resolution of 0.4. CellMarker 2.0 database (http://117.50.127.228/CellMarker/) was then used for manual annotation of all cell subpopulations [19]. For the macrophage subpopulations, the same standard single-cell data processing workflow was followed. Subsequently, we use the AddModuleScore function to calculate the inflammation score for each macrophage, using a gene set related to inflammation as the basis for calculation (TNF, CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CXCL10, S100A8, CXCL1).

Pseudotime analysis

We conducted pseudotime analysis using the Monocle2 package [20]. We extracted the macrophage subpopulations from the Seurat object of all cells and converted them into a Monocle object using the newCellDataSet function. Subsequently, we loaded the feature genes into the Monocle object and utilized the DDRTree method for dimensionality reduction. The cells were then ordered based on the computed pseudotime ordering. We used the plot_genes_in_pseudotime function to illustrate the expression changes of genes of interest over pseudotime.

Network pharmacology analysis

We used the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP) database (https://www.tcmsp-e.com/) to obtain the active ingredients (with oral bioavailability (OB) > 30% & drug-likeness (DL) ≥ 0.18) of Astragalus membranaceus and the target proteins of these active ingredients [21]. The criteria for selecting the active ingredients mentioned above have been validated by existing network pharmacology literature [22–24]. The target protein names were converted using the STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/) to obtain the corresponding gene names. A Venn diagram was employed to display the intersection genes between the drug-target genes and macrophage-related feature genes. Subsequently, the obtained network of active drug ingredients and target genes was visualized using Cytoscape software, with drug components assigned the color green and target genes assigned the color blue.

Gene enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis are the most commonly used methods for gene enrichment analysis. We used the Metascape database (https://www.metascape.org) for the above analysis [25]. The gene list was uploaded to the analysis page, then Gene Ontology Biological Process (GOBP) and KEGG analysis options were selected, along with default parameters (Min Overlap = 3 & P Value Cutoff = 0.01 & Min Enrichment = 1.5) for the analysis. The criteria for enriching pathways above are the default parameters recommended by the Metascape database. The results of the analysis were visualized using the ggplot2 package. A significance level of P < 0.01 was considered statistically significant.

Survival prognosis analysis

We conducted survival prognosis analysis on the intersection genes using the GEPIA database (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/) [26]. The GEPIA database is a survival prognosis analysis tool established by the creators of the database using a large amount of sequencing data. We selected the LUAD database, allowed for automatic calculation of the cutoff value, uploaded the gene list for which survival curves needed to be plotted, and obtained the completed survival curves. The Hazard Ratio (HR) value and P-value were automatically annotated on the survival curves. The 95% confidence interval was automatically labeled on the survival curve. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, while HR > 1 was considered a risk factor, and HR < 1 was considered a protective factor.

Immunofluorescence staining

We obtained tissue microarrays of LUAD from the Baiqiandu Company, comprising 80 cancer tissues and corresponding pericancerous tissues from different patients. The tissue microarrays were deparaffinized using xylene and hydrated using a gradient concentration of alcohol. The hydrated microarrays were then subjected to antigen retrieval using high-temperature EDTA treatment. After antigen retrieval, the microarrays were stained using the tyramide signal amplification (TSA) staining kit (ABclonal, CAT #RK05902). The primary antibodies used were CD68 (ABclonal, CAT #A20803) and STAT1 (ABclonal, CAT #A12075). Subsequently, staining procedures were performed according to the instructions of the TSA staining kit, and DAPI was used to stain the cell nuclei. Finally, the stained sections were scanned and imaged using a confocal microscope (Leica, STELLARIS 5).

Cell culture

THP1 cells were seeded into plate/dish and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Servicebio, CAT #G4531) supplemented with 10% FBS (Servicebio, CAT #G8003), 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol (MCE, CAT #HY-Y0326), and 1% P/S (Servicebio, CAT #G4003). The recombinant human protein IL4 (abcam, CAT #ab155733) is used to induce THP1 polarization towards the M2 direction, while lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Beyotime, CAT #ST1470) is used to induce THP1 polarization towards the M1 direction.

Flow cytometry

All processed cells need to be incubated with the following antibodies at 4 °C: anti-CD45-APC (Invitrogen, CAT #17-0459-42), anti-CD11b-PE (Invitrogen, CAT #12-0112-82), anti-CD80-PerCP (Invitrogen, CAT #46-0809-42), anti-CD206-PE-CY7 (Invitrogen, CAT #25-2061-82). After the cell fixation was performed, the Beckman CytoFLEX flow cytometer was used to generate and export data. The exported data was then further analyzed using FlowJo.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software and GraphPad Prism 9. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K–S) test and Shapiro–Wilk (S–W) test were used to determine if the data followed a normal distribution. If the data followed a normal distribution, the student’s t-test was used to assess differences between two groups. If the data did not follow a normal distribution, non-parametric tests were used to determine differences between two groups. A significance level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Single-cell transcriptomic atlas of LUAD

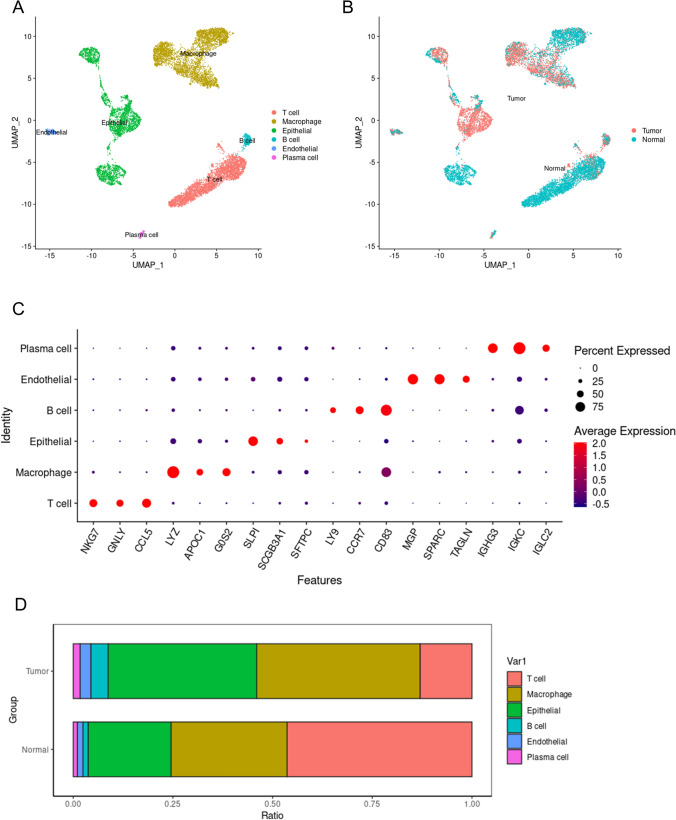

After the removal of low-quality cells, a total of 11,485 cells were classified into six major cell types (Fig. 1A). Among them, the epithelial cells originating from tumor tissues are malignant tumor cells, while epithelial cells from normal tissues could be epithelial cells from different tissue origins, such as tracheal epithelial cells. Endothelial cells originating from tumor tissues could be vascular endothelial cells within the tumor, whereas endothelial cells from normal tissues are normal vascular endothelial cells. The remaining four cell types are all immune cells, with macrophages being the most prominent, followed by T cells, B cells, and plasma cells, respectively. All cells are colored according to their tissue origin. It can be observed that cells from tumor tissue and normal tissue exhibit significant heterogeneity, indicating that in the tumor microenvironment, not only have the tumor cells undergone changes, but there is also an alteration in the biological function of other cells (Fig. 1B). Figure 1C shows the marker genes used for the annotation of cell types. We observed a significant difference in the proportion of macrophages between tumor tissue and normal lung tissue, with more macrophages present in the tumor tissue (Fig. 1D). This indicates the important role of macrophages in the tumor immune microenvironment.

Fig. 1.

Lung adenocarcinoma single-cell panoramic map. A All cells are colored according to cell type, where dots of different colors represent different types of cells. B All cells are colored based on tissue origin, with dots of different colors representing cells from different tissues. C marker genes of the cells, red indicates high gene expression levels, blue indicates low gene expression levels, and the size of the bubbles represents the percentage of gene expression. D The bars of different colors represent the proportions of different types of cells in tumor tissue or normal lung tissue

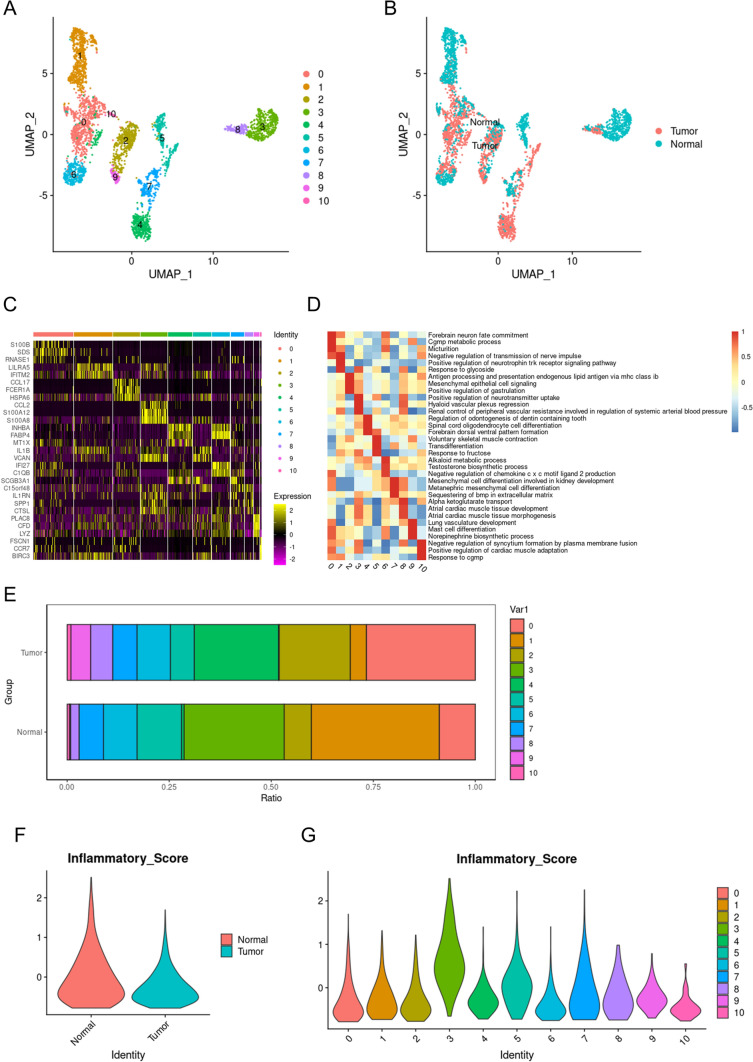

Macrophage single-cell panoramic

A total of 1928 macrophages were screened for further analysis. These macrophages were divided into 11 subgroups (Fig. 2A). Based on the source of the samples, the cells can be divided into those originating from tumor tissue and those from normal lung tissue. After coloring the macrophages according to tissue origin, it can be seen that there is considerable heterogeneity between macrophages originating from normal tissues and those from tumor tissues (Fig. 2B). These macrophages were divided into 11 subsets based on the markers they express (Fig. 2C). Each of these 11 subgroups of macrophages had different functions. We further elucidated the specific functions undertaken by the macrophages in each subgroup using GSVA analysis (Fig. 2D). We further observed that the proportions of different macrophage subpopulations vary between tumor tissues and normal lung tissues (Fig. 2E). This indicates that macrophages exhibit heterogeneity in different microenvironments. Macrophages derived from tumor tissues are generally referred to as TAMs. Previous studies have considered TAMs to have anti-tumor effects, but there is also evidence that TAMs maintain the tumor immune microenvironment, promote tumor immune escape, and facilitate tumor progression [27, 28]. It is generally believed that M1-type macrophages play an anti-tumor role, whereas M2-type macrophages promote tumor development. We used an inflammation score to rate each macrophage and found that macrophages from normal tissues had higher inflammation scores than those from tumor tissues (Fig. 2F). This indicates a large presence of M2-type macrophages in tumor tissues. Subgroup 3 macrophages had higher inflammation scores than the other ten subgroups, suggesting that subgroup 3 is primarily composed of M1-type macrophages (Fig. 2G). Inflammation scores can indirectly indicate the polarity of macrophages; M1 macrophages exhibit higher inflammation scores, while M2 macrophages show lower inflammation scores.

Fig. 2.

Macrophages’ single-cell panoramas. A All macrophages are colored according to subgroups, with dots of different colors representing macrophages from different subgroups. B All macrophages are colored according to the tissue of origin, with dots of different colors representing macrophages from different tissues. C Different colored bars represent different macrophage subgroups, and each stripe in the heatmap represents a cell. Yellow indicates increased expression, while purple indicates decreased expression. D Red indicates that the pathway is activated, while blue indicates that the pathway is not activated. E The bars of different colors represent the proportions of different macrophage subgroups in tumor tissue or normal lung tissue. F The inflammasome scores of macrophages originating from tumors and normal tissues. G The inflammasome scores of macrophages from different subgroups

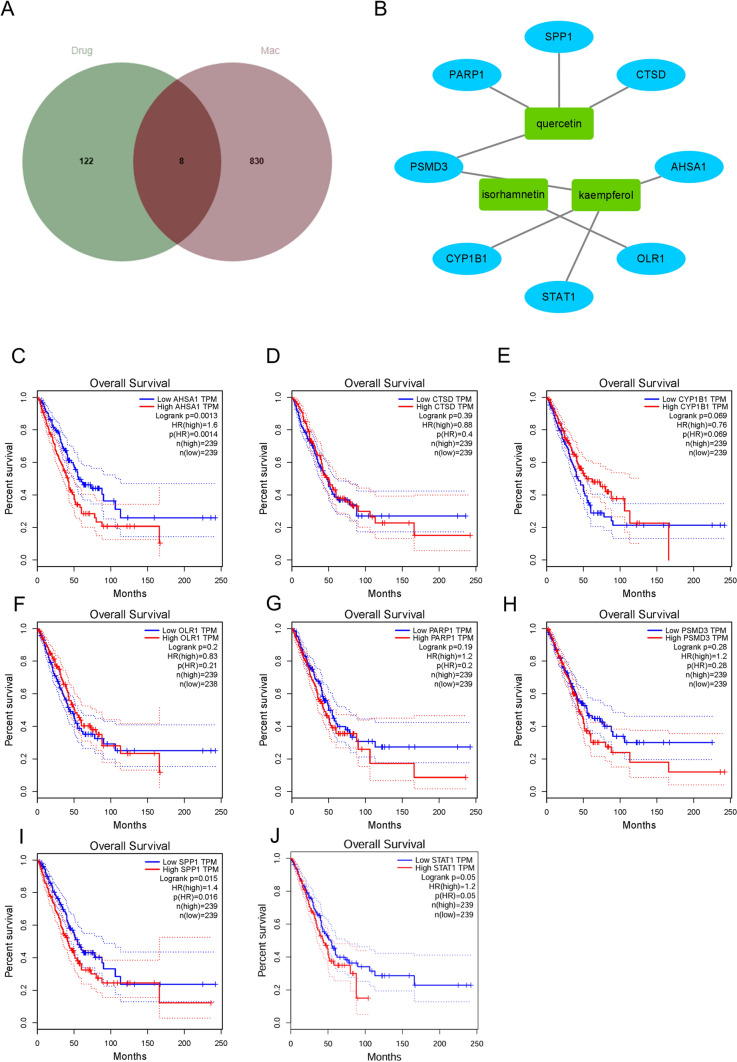

Network pharmacology and survival analysis

A search of the TCM database revealed that there are 17 main components of Astragalus membranaceus, and the target genes corresponding to the main components total 130 (Table S1). The intersection of target genes corresponding to all main drug components and the characteristic genes of macrophages yielded a total of 8 intersecting genes (Fig. 3A). There are 3 main components corresponding to these 8 intersecting genes, which are quercetin, isorhamnetin, and kaempferol (Fig. 3B). Survival analysis showed the difference in overall survival rates between high and low expression groups of these 8 genes in patients with LUAD. Among them, AHSA1, CYP1B1, SPP1, and STAT1 showed statistical differences (Fig. 3C, E, I, and J), while CTSD, OLR1, PARP1, and PSMD3 did not show significant statistical differences (Fig. 3D, F, G, and H). This suggests that AHSA1, CYP1B1, SPP1, and STAT1 may play an important role in the development and progression of LUAD.

Fig. 3.

Network pharmacology and survival analysis. A The intersection between the target genes of the drug and the characteristic genes of macrophages. B A network graph of the intersecting genes and corresponding drug components, with blue representing genes and green representing drugs. C KM (Kaplan–Meier) survival curve of AHSA1. D KM survival curve of CTSD. E KM survival curve of CYP1B1. F KM survival curve of OLR1. G KM survival curve of PARP1. H KM survival curve of PSMD3. I KM survival curve of SPP1. J KM survival curve of STAT1. The dashed line represents the 95% confidence interval of the survival curve

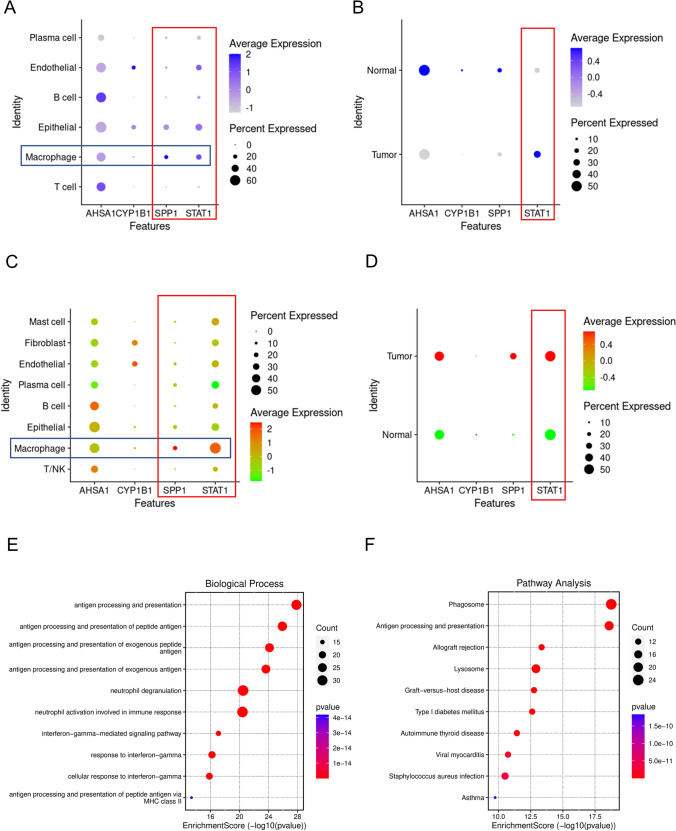

STAT1 plays a key role in LUAD’s TAMs

In our study, we examined the expression levels of various genes in macrophages and observed notable differences. AHSA1, SPP1, and STAT1 are expressed at higher levels in macrophages, while CYP1B1 shows lower expression in these cells (Fig. 4A). Specifically, TAMs and macrophages derived from normal tissue, only STAT1 is significantly upregulated in TAMs. In contrast, AHSA1, SPP1, and CYP1B1 are upregulated in macrophages from normal tissue (Fig. 4B). To validate these findings externally, we utilized data from GSE198099, which confirmed the increased expression of STAT1 and SPP1 in macrophages (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, we identified elevated levels of STAT1 specifically in TAMs (Fig. 4D), suggesting a pivotal role for STAT1 in TAMs. Kaempferol, a known anti-tumor compound, has been shown to induce apoptosis in tumor cells across various cancers, thus exhibiting potential anti-tumor effects. Given the importance of STAT1 in TAMs, it is conceivable that kaempferol may exert its effects by modulating STAT1 in TAMs, altering the tumor immune microenvironment and enhancing anti-tumor activity. To explore this hypothesis, we classified macrophages into STAT1-positive and STAT1-negative groups based on their STAT1 expression levels and conducted enrichment analysis on differentially expressed genes between these groups. Our analysis revealed that upregulated genes in the STAT1-positive group were primarily enriched in immune-related pathways (Fig. 4E and F), highlighting the strong association between STAT1 and immune function in the tumor microenvironment.

Fig. 4.

STAT1 plays an important role in TAMs. A Expression levels of prognostically relevant genes in different cell types in GSE117570. B Expression levels of prognostically relevant genes in macrophages of tumor tissue and normal tissue in GSE117570, with blue indicating increased expression and gray indicating decreased expression. C Expression levels of prognostically relevant genes in different cell types in GSE198099. D Expression levels of prognostically relevant genes in macrophages of tumor tissue and normal tissue in GSE198099, with red indicating increased expression and green indicating decreased expression. E GOBP (Gene Ontology Biological Process) enrichment of upregulated genes in macrophages expressing STAT1. F KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) enrichment of upregulated genes in macrophages expressing STAT1

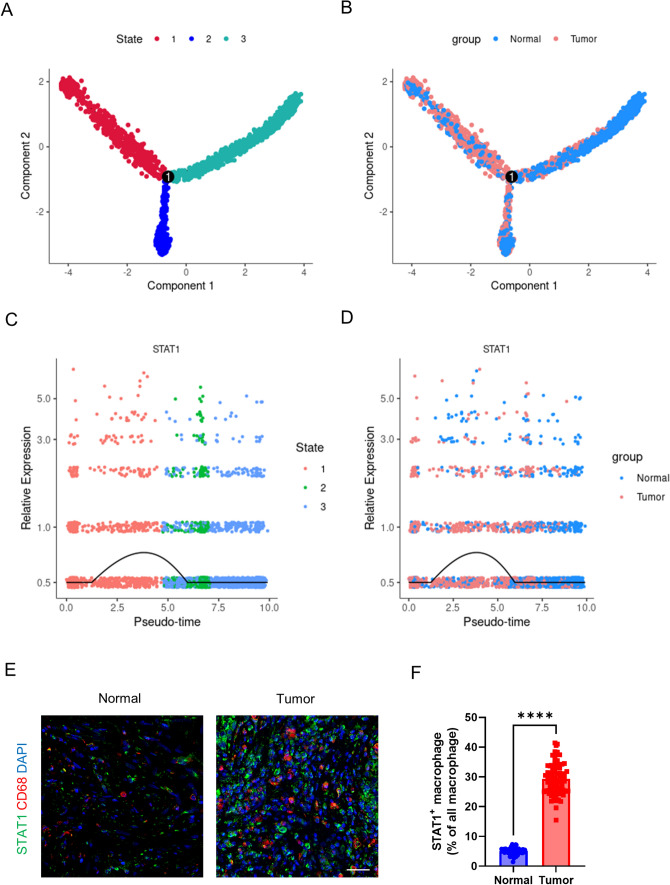

The pseudo-time analysis and immunofluorescence validation

Pseudo-time analysis reveals the status of all macrophages arranged in virtual time under genetic changes. All macrophages can be divided into three states, starting from state 1 and, after reaching the bifurcation node, differentiate into states 2 and 3 (Fig. 5A). When macrophages are colored according to tissue origin, a transition state is observed between macrophages from normal tissue and TAMs (Fig. 5B). STAT1 has the highest expression in state 1 and is most highly expressed in TAMs (Fig. 5C and D). This indicates the crucial role of STAT1 in TAMs, which may have an impact on macrophage polarization. Moreover, after using tissue microarrays to perform immunofluorescence colocalization, it was discovered that STAT1 expression increases in tumor tissues, and STAT1 is expressed in TAMs (Fig. 5E and F). Although STAT1 may also be expressed in other cells, its expression level in TAMs is significantly higher than in macrophages derived from normal tissue. This highlights the role of STAT1 as a key transcription factor in TAMs.

Fig. 5.

Pseudotime analysis of STAT1 and immunofluorescence validation. A All macrophages are colored according to their status and distributed along the pseudotime branches. B All macrophages are colored according to their tissue origin and distributed along the pseudotime branches. C Distribution of STAT1 expression along the pseudotime axis, with cells colored by status. D Distribution of STAT1 expression along the pseudotime axis, with cells colored by tissue origin. E Representative images of STAT1 and CD68 immunofluorescence staining and F statistical results of the immunofluorescence. **** means P < 0.001

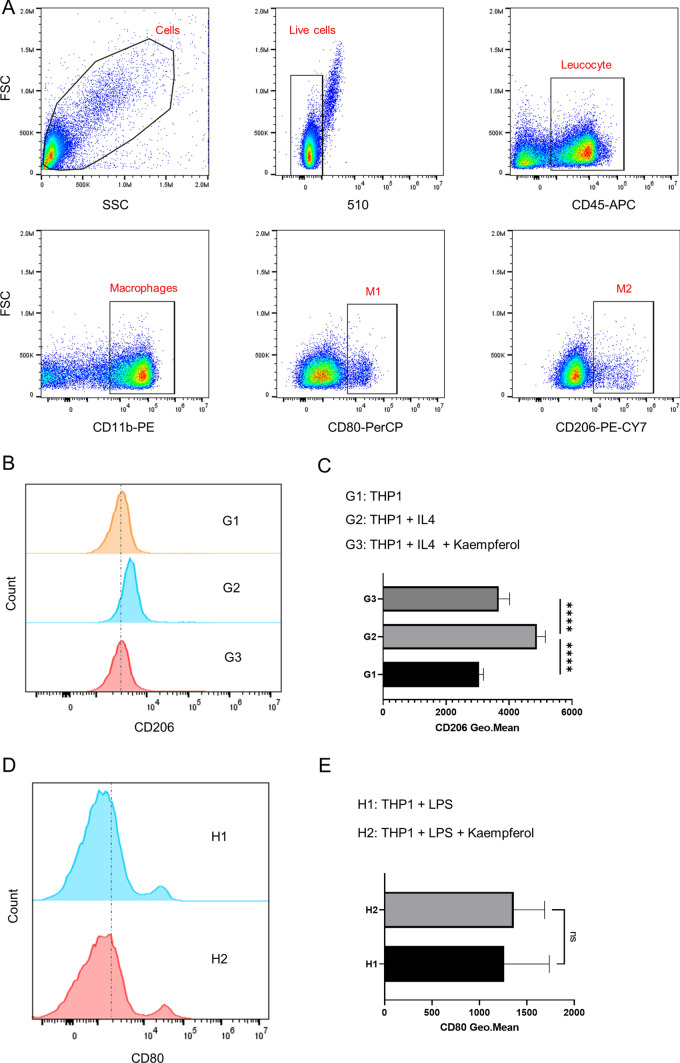

Kaempferol affects the M2 polarization of macrophages

We use THP1 cells to simulate the polarization of macrophages, and the polarization toward M1 or M2 can be induced in THP1 cells by using LPS and IL4. Figure 6A shows the flow cytometry gating procedure for detecting macrophages. We use IL4 to induce the polarization toward M2. Then, we add Kaempferol (50 μM) to observe whether it will affect the M2 polarization of THP1 cells. After the induction with IL4, the expression of CD206 in THP1 cells can be detected by flow cytometry. It is found that the expression of CD206 increases after adding IL4, but this trend can be reversed by the addition of Kaempferol (Fig. 6B and C). This suggests that Kaempferol may reduce macrophage M2 polarization. When we add LPS in THP1 cells to induce macrophage M1 polarization, we find that there is no statistical difference in the expression of CD80 between the two groups after adding Kaempferol (Fig. 6D and E), indicating that Kaempferol does not affect the M1 polarization of macrophages. Delivering Kaempferol to TAMs more precisely is one of the anti-tumor strategies.

Fig. 6.

Kaempferol inhibits macrophage M2 polarization. A Flow cytometry strategy for screening M1 and M2 macrophages. B Representative flow cytometry graphs of kaempferol inhibiting macrophage M2 polarization and C flow cytometry statistical results (Each group n = 15). D Representative flow cytometry graphs showing that kaempferol has no significant effect on macrophage M1 polarization and E flow cytometry statistical results (Each group n = 15)

Discussion

The present research provides comprehensive insights into the heterogeneity and functional states of macrophages in LUAD by employing single-cell transcriptomics, network pharmacology, and pseudotime analysis. Our study not only delineates the distribution of macrophage subpopulations within the TME but also identifies pharmacologically active components from TCM that could modulate the polarization of macrophages, potentially offering new therapeutic avenues for LUAD.

The observed heterogeneity in macrophage subpopulations, particularly in TAMs, substantiates the multiplicity of roles that immune cells play within the TME. Notably, TAMs are typically associated with an immune suppressive environment, fostering tumor growth and progression [29, 30]. Our results indicated a parsimonious presence of M1-type macrophages in LUAD tissues, which could explain the often-dysregulatory TME that allows cancer cells to evade immune surveillance. The identification of increased M2-type macrophages within tumor tissues corresponds with previously reported tendencies for these cells to contribute to tumor progression and metastasis [31].

Our analysis discovered four genes (AHSA1, CYP1B1, SPP1, and STAT1) among the intersection of TCM target genes and macrophage-specific genes that were differentially expressed and carried prognostic value for LUAD. This underscores the impact these genes could have on macrophage function and the overall outcome of LUAD. STAT1’s marked expression in TAMs and its overarching role in immune pathways, as evidenced by the differential expression analysis, singles it out as a potential key regulator within the TME. Interestingly, previous studies have highlighted the dual role of STAT1 in cancer, where it may contribute to both tumor suppressive and tumor promoting mechanisms depending on the context. STAT1 plays an important role in tumor immunity. Its function can promote tumor immune surveillance. STAT1 is mainly activated through cytokine pathways such as IFN, subsequently translocating to the cell nucleus to regulate the expression of multiple genes related to immune responses. Activation of STAT1 can enhance the anti-tumor activity of NK cells and is associated with the polarization of macrophages [32].

The active compounds derived from Astragalus membranaceus—quercetin, isorhamnetin, and kaempferol—target a number of genes expressed in macrophages, which could modulate their function. These findings are supported by the immunofluorescence experiments that confirm the elevated expression of STAT1 in TAMs within the LUAD tissues. The ensuing cell culture experiments revealed that kaempferol can reverse M2 polarization induced by IL4 in THP1 cells, suggesting a role for this TCM-derived agent in modulating macrophage plasticity. Interestingly, kaempferol did not alter M1 polarization induced by LPS, indicating a selective regulatory aspect. The signaling pathways activated by M1 polarization and M2 polarization of macrophages are different. Kaempferol may inhibit M2 polarization of macrophages by blocking the signaling pathway of M2 polarization. However, for the signaling pathway of M1 polarization, kaempferol may not have a blocking effect. This finding aligns with existing literature that points to the diverse biological effects of kaempferol, including anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor properties.

The implication that kaempferol inhibits M2 polarization of macrophages paves the way for novel therapeutic strategies targeting TAMs to improve immune responses in LUAD. With immunotherapy becoming a mainstay in cancer treatment, understanding the molecular underpinnings influencing the immune landscape within the TME is crucial. Therapeutic strategies aimed at skewing TAMs towards a M1 phenotype might impede cancer progression and enhance the efficacy of existing treatments.

Our study, nonetheless, is not devoid of limitations. For instance, the extrapolation of results from in vitro studies to clinical outcomes necessitates caution, and in-depth in vivo verifications are warranted. Additionally, the drug candidates were selected based on their ability to cross the intestinal barrier, but their pharmacokinetics and dynamics within the human body, specifically their ability to target intra-tumoral macrophages, remain to be validated.

In summary, this study not only enriches our understanding of the complex interplay between immune cells and cancer cells within the TME of LUAD but also identifies potential components from TCM that could significantly affect macrophage polarization and function. STAT1 emerges as a pivotal regulator of TAM activity, and kaempferol as a promising therapeutic agent, meriting further investigation into its clinical application for modulating macrophage phenotypes in cancer therapy.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

L.W. wrote the main manuscript text. L.W., W.H. and L.L. prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. Y.S. and Lin W. reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the GEO with the primary accession code GSE117570 and GSE198099.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Permission of the Hospital Ethics Committee was obtained by the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center’s ethics committee. All participants in the study signed an informed consent form, and the study did not include minors.

Methods statement

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Laiyi Wan, Lin Wang and Yanzheng Song contributed equally to this work and shared last authorship.

Contributor Information

Laiyi Wan, Email: wanlaiyi@shaphc.org.

Lin Wang, Email: wlxxs2011@163.com.

Yanzheng Song, Email: yanzhengsong@163.com.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Miller K, Wagle N, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(1):17–48. 10.3322/caac.21763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu F, Wang L, Zhou C. Lung cancer in China: current and prospect. Curr Opin Oncol. 2021;33(1):40–6. 10.1097/cco.0000000000000703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Succony L, Rassl D, Barker A, McCaughan F, Rintoul R. Adenocarcinoma spectrum lesions of the lung: detection, pathology and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2021;99: 102237. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2021.102237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel R, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei K, Ma Z, Yang F, et al. M2 macrophage-derived exosomes promote lung adenocarcinoma progression by delivering miR-942. Cancer Lett. 2022;526:205–16. 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu F, Fan J, He Y, et al. Single-cell profiling of tumor heterogeneity and the microenvironment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2540. 10.1038/s41467-021-22801-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang L, Zhang Y, Wang C, et al. Integrated single-cell RNA sequencing analysis reveals distinct cellular and transcriptional modules associated with survival in lung cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):9. 10.1038/s41392-021-00824-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salcher S, Sturm G, Horvath L, et al. High-resolution single-cell atlas reveals diversity and plasticity of tissue-resident neutrophils in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(12):1503-1520.e8. 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Xu Y, Sun Q, et al. New insights from the single-cell level: tumor associated macrophages heterogeneity and personalized therapy. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2022;153:113343. 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C, Yu Q, Song T, et al. The heterogeneous immune landscape between lung adenocarcinoma and squamous carcinoma revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):289. 10.1038/s41392-022-01130-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao X, Peng Y, Wang Z, et al. A novel immune checkpoint siglec-15 antibody inhibits LUAD by modulating mφ polarization in TME. Pharmacol Res. 2022;181: 106269. 10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller K, Nogueira L, Devasia T, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(5):409–36. 10.3322/caac.21731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Widyananda M, Kharisma V, Pratama S, et al. Molecular docking study of sea urchin (Arbacia lixula) peptides as multi-target inhibitor for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) associated proteins. J Pharm Pharmacognosy Res. 2021;9:484–96. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menna EG, Samy AFM, Michael S, Tatiana S, Thomas S. Arglabin, an EGFR receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022. 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jia C, Huike M, Yujiao M, et al. Analysis of the mechanism underlying diabetic wound healing acceleration by Calycosin-7-glycoside using network pharmacology and molecular docking. Phytomedicine. 2023. 10.1016/j.phymed.2023.154773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu J, Wang Z, Huang L, et al. Review of the botanical characteristics, phytochemistry, and pharmacology of Astragalus membranaceus (Huangqi). Phytotherapy Res PTR. 2014;28(9):1275–83. 10.1002/ptr.5188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li C, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Li J, Lai J. Astragalus polysaccharide: a review of its immunomodulatory effect. Arch Pharmacal Res. 2022;45(6):367–89. 10.1007/s12272-022-01393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qianqian S, Gregory AH, Leonard W, et al. Dissecting intratumoral myeloid cell plasticity by single cell RNA-seq. Cancer Med. 2019. 10.1002/cam4.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Congxue H, Tengyue L, Yingqi X, et al. Cell Marker 2.0: an updated database of manually curated cell markers in human/mouse and web tools based on scRNA-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022. 10.1093/nar/gkac947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiaojie Q, Qi M, Ying T, et al. Reversed graph embedding resolves complex single-cell trajectories. Nat Methods. 2017. 10.1038/nmeth.4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jinlong R, Peng L, Jinan W, et al. TCMSP: a database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J Cheminform. 2014. 10.1186/1758-2946-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lisheng C, Lei C, Wenbin W, et al. Multi-omics analysis combined with network pharmacology revealed the mechanisms of rutaecarpine in chronic atrophic gastritis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024. 10.1016/j.jep.2024.119151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yaping M, Zhenghui X, Xiangxia Z, et al. Ergothioneine ameliorates liver fibrosis by inhibiting glycerophospholipids metabolism and TGF-β/Smads signaling pathway: based on metabonomics and network pharmacology. J Appl Toxicol. 2024. 10.1002/jat.4728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bingying D, Guoyong Z, Yixuan Z, et al. Gualou Xiebai Banxia decoction suppresses cardiac apoptosis in mice after myocardial infarction through activation of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase 2. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024. 10.1016/j.jep.2024.119143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yingyao Z, Bin Z, Lars P, et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 2019. 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zefang T, Chenwei L, Boxi K, et al. GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017. 10.1093/nar/gkx247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antonella A, Alessandro A, Ingrid Catalina C, Giulia DM, Vanessa D. Decoding the intricate landscape of pancreatic cancer: insights into tumor biology, microenvironment, and therapeutic interventions. Cancers (Basel). 2024. 10.3390/cancers16132438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amanda Katharina B, Franziska B, Jan D, Niels S. Non-coding RNA in tumor cells and tumor-associated myeloid cells-function and therapeutic potential. Int J Mol Sci. 2024. 10.3390/ijms25137275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bo M, Na Z, Petra M, et al. Hypoxia drives HIF2-dependent reversible macrophage cell cycle entry. Cell Rep. 2024. 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chi-Shuan F, Hui-Chen H, Chia-Chi C, et al. Development of a humanized antibody targeting extracellular HSP90α to suppress endothelial-mesenchymal transition-enhanced tumor growth of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Cells. 2024. 10.3390/cells13131146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mengyuan H, Fengying D, Xinlei S, Hongkun Z, Fei Y. The crosstalk between immune cells and tumor pyroptosis: advancing cancer immunotherapy strategies. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024. 10.1186/s13046-024-03115-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren Y, Ma Q, Zeng X, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals immune microenvironment niche transitions during the invasive and metastatic processes of ground-glass nodules and part-solid nodules in lung adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):263. 10.1186/s12943-024-02177-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the GEO with the primary accession code GSE117570 and GSE198099.