Abstract

Background & Aims

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third-leading and fastest rising cause of cancer-related death worldwide. The discovery and preclinical development of compounds targeting HCC are hampered by the absence of authentic tractable systems recapitulating the heterogeneity of HCC tumors in patients and the tumor microenvironment (TME).

Methods

We established a novel and simple patient-derived multicellular tumor spheroid model based on clinical HCC tumor tissues, processed using enzymatic and mechanical dissociation. After quality controls, 22 HCC tissues and 17 HCC sera were selected for tumor spheroid generation and perturbation studies. Cells were grown in 3D in optimized medium in the presence of patient serum. Characterization of the tumor spheroid cell populations was performed by flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry (IHC), and functional assays. As a proof of concept, we treated patient-derived spheroids with FDA-approved anti-HCC compounds.

Results

The model was successfully established independently from cancer etiology and grade from 22 HCC tissues. The use of serum from patients with HCC was essential for tumor spheroid generation, TME function, and maintenance of cell viability. The tumor spheroids comprised the main cell compartments, including epithelial cancer cells, as well as all major cell populations of the TME [i.e. cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), macrophages, T cells, and endothelial cells]. Tumor spheroids reflected HCC heterogeneity, including variability in cell type proportions and TME, and mimicked the original tumor features. Moreover, differential responses to FDA-approved anti-HCC drugs were observed between the donors, as observed in patients.

Conclusions

This patient HCC serum-tumor spheroid model provides novel opportunities for drug discovery and development as well as mechanism-of-action studies including compounds targeting the TME. This model will likely contribute to improve the therapeutic outcomes for patients with HCC.

Impact and implications:

HCC is a leading and fast-rising cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Despite approval of novel therapies, the outcome of advanced HCC remains unsatisfactory. By developing a novel patient-derived tumor spheroid model recapitulating tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment, we provide new opportunities for HCC drug development and analysis of mechanism of action in authentic patient tissues. The application of the patient-derived tumor spheroids combined with other HCC models will likely contribute to drug development and to improve the outcome of patients with HCC.

Keywords: Liver cancer, 3D model, Tumor spheroids, Drug discovery and development, Immuno-oncology

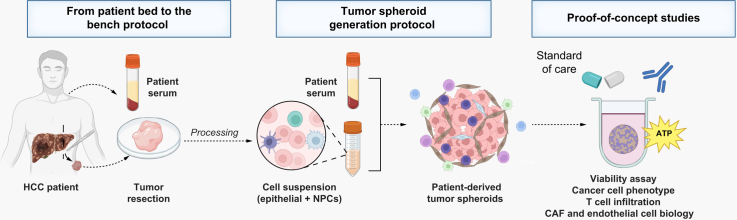

Graphical abstract

Highlights:

-

•

A tumor spheroid model was established using HCC tissues and patient sera.

-

•

Tumor spheroids include the main cell compartments and the TME.

-

•

Addition of HCC patient serum improves tumor spheroid viability and TME function.

-

•

Tumor spheroids reflect HCC heterogeneity and retain features of original tumors.

-

•

This model will improve drug development and the understanding of cancer biology.

Introduction

HCC is the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide and the leading cause of death in patients with cirrhosis,1 with HCC incidence increasing rapidly in Europe and the USA.1 The major causes of HCC are chronic HBV and HCV, alcohol abuse, and metabolism-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Although viral hepatitis was previously a major cause of liver disease and HCC, metabolic liver disease will likely be the major cause of HCC in the future due to changes in lifestyle associated with increasing obesity and diabetes.2

Current treatment options remain unsatisfactory. Early-stage tumors can be treated using surgical approaches, radiofrequency ablation, or liver transplantation; nevertheless, fewer than 30% of patients with HCC are eligible because their disease is often diagnosed at an advanced stage.3,4 Although the recently approved combination of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-targeting agents with immune checkpoint inhibitors (CPIs) targeting programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) has changed the standard of care, both overall response rates and improvement of survival remain limited.3,4

A roadblock to HCC drug discovery and development is HCC heterogeneity among patients.5 Moreover, preclinical assessment of the efficacy of anti-HCC candidate compounds is hampered by the absence of tractable systems recapitulating the heterogeneity of tumors and the TME, which have a key role in treatment response.6 Two-dimensional (2D) or planar cell culture remains one of the most applied models in drug discovery because it is simple to use, low cost, and easily applied in high-throughput screening. However, it does not effectively mimic the activity, function, and behavior of cells in an organ or the complex cell–cell, cell–extracellular matrix (ECM) and cell–tissue interactions.7 Organoids have emerged as a major breakthrough in cell biology and drug discovery by recapitulating functional features of in vivo tissues in 3D culture. However, they must be grown by stem cells through a complex induction process that hampers the success rate of organoid cultures.8 Their growth relies on rigid ECMs that create biochemical forces on cells, reducing drug penetration.9 Moreover, HCC organoids often lack tumor stroma and do not allow TME-targeting drug testing.8 Finally, the use of animal models is also limited because of their complexity, cost, and differences between species, as well as their limited translatability to patients.10 To address these limitations, we established a simple and robust patient-derived spheroid model recapitulating HCC heterogeneity and TME to facilitate drug development and improve understanding of cancer biology.

Materials and methods

Human subjects

Human liver tissues and sera were obtained from patients with liver disease undergoing liver resection. Patients were given an information sheet requesting their leftover biological material (i.e. liver resection and blood samples) collected during their medical treatment for research purposes. All patients received and signed an informed consent form for deidentified use of their samples from Strasbourg University Hospitals, University of Strasbourg, France (DC-2016-2616 and RIPH2 LivMod IDRCB 2019-A00738-49, ClinicalTrial.gov ID: NCT04690972) or from Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan (approval number: HI-98-21). The protocols were approved by the local Ethics Committee of the University of Strasbourg Hospitals and the Hiroshima University Ethical Committee, respectively. All material was collected during medical procedures strictly performed within the frame of the medical treatment of each patient. While there was clinical descriptive data available, the identity of the patients was protected by internal coding. A brief summary of clinical characteristics is provided in Tables S1 and S2. Sera from healthy patients were collected at Etablissement Français du Sang, Strasbourg, France.

Tissue processing and tumor spheroid generation from fresh tissue

The references of the reagents used for tumor spheroid generation are reported in the JHEP Reports CTAT methods. A protocol ‘from patient bed to the bench’ was established with surgeons from Strasbourg University Hospital to preserve tissue integrity and cell viability. Tissue resections were immediately preserved after surgery in cold transplantation medium (HypoThermosol®, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO), kept on ice to avoid warm ischemia, and processed a maximum of 30 min after resection. Fresh tissues were directly processed and minced into small pieces. Then, 0.2–1 g of tissue was transferred into GentleMACS™ C Tubes (Miltenyi Biotec, Paris, France) and dissociating using a tumor dissociation kit and GentleMACS™ Octo Dissociator with Heaters (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After dissociation, the cells were filtered using a 100-μm strainer to eliminate debris and centrifuged at 700 g for 7 min. The pellet was gently resuspended and washed in cold Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS). Erythrocytes were lysed using erythrocyte lysis buffer (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) and cells were washed again with HBSS. The number of cells and cell viability were assessed using Trypan Blue and an automatic cell counter (Countess 3 Cell Counters, Thermo Fisher Scientific, France).

The required number of cells was then resuspended in complete Mammocult medium (MammoCult™ Human Medium Kit, STEMCELL Technologies, Grenoble, France), supplemented with human proliferation supplement (3.4%), hydrocortisone (0.056%), heparin (0.011%), amphotericin B, primocin, and 20% serum from patients with HCC, and seeded in 96- or 384-well ultra-low attachment plates (Corning®, Thermo Fisher Scientific). For 96-well plates (characterization), ∼75,000–100,000 cells in 50 μL were required per well. For 384-well plates (for screening of FDA-approved drugs), ∼30,000 cells in 25 μL were required. The plates were then centrifuged at 300 g for 6 min. From 2 to 3 days after seeding, 50 or 25 μl of complete medium was added per well. This small volume of medium at the beginning of the culture enables cell concentration and improves cell migration. Tumor spheroid formation began between 4 and 7 days post seeding and was patient dependent, as was the expected tumor spheroid size (on average 100–250 μm in 96-well plates). Of note, extra cells were frozen at –80 °C in CryoStor® cryopreservation media (Sigma-Aldrich).

Go/no go step: for fresh tissue, the expected cell viability was, on average, 60–70%. If viability was ∼40%, dead cell removal was required using a Dead Cell Removal Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. When viability was <30%, the advantage of dead cell removal versus cell viability was lost, given that poor viability resulted in tumor spheroid generation failure.

Tumor spheroid generation from frozen tissue or frozen cells

HCC tissue freezing can be performed by cutting the tissue into small pieces and freezing them in CryoStor® cryopreservation media with slow temperature decrease (Thermo Fisher Scientific Mr. Frosty™ Freezing Container). Use of DMSO alone may affect immune cell viability after thawing. To generate tumor spheroids from cryopreserved tissues, the tissue pieces or frozen cells were thawed at 37 °C, rinsed and then washed with HBSS to eliminate the cryopreservative medium; either the dissociation protocol for tissues was then followed or dead cell removal was performed using the dissociated cells, as described above. Erythrocyte lysis was not needed for frozen samples. Perturbation studies were then performed only if the cell viability after processing was >40% and cells had properly aggregated after 3 to 4 days.

Statistical analysis and reproducibility

For experiments on patient-derived tumor spheroids and with patient sera, the limited amount of HCC tissue and blood restricted the number of repeated experiments for the same donor. Thus, to ensure the reproducibility of our findings, and for arresting conclusions, we performed independent experiments on different tissues. The number of technical replicates was three or four for each experiment (unless otherwise stated). The precise number (n) of biologically independent samples is indicated in the figure legends. The data are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical analyzes were performed for n ≥3, using parametric tests (unpaired Student t test, one-way ANOVA) or nonparametric tests (two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test) as indicated in figure legends, after determination of distribution by the Shapiro-Wilk normality test; p <0.05 was considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism was used for all statistical analyses (V10.2.1; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

More information about the materials and method, antibodies, and primers lists is available in the supplementary information online and CTA table.

Results

A simple and robust protocol to establish patient-derived HCC tumor spheroids

As detailed in the Materials and Methods sections in the supplementary information online, a protocol ‘from patient bed to the bench’ was established to generate high-quality patient-derived tumor spheroids using HCC tumor tissues (Fig. 1A). Tumor tissues were dissociated using mechanical and enzymatic digestion and tumor spheroids were generated using a scaffold-free approach, in ultra-low attachment microplates in the presence of patient autologous sera (Fig. 1A). Cell aggregation started 3 to 4 days after seeding, with complete cell compaction into tumor spheroids after 5–7 days on average (Fig. 1B). Optimal culture conditions maintained high cell viability up to 7 days after seeding (Fig. 1C). Moreover, the cell suspension obtained after tissue dissociation to generate tumor spheroids allowed homogenous formation of spheres among the different wells (Fig. 1D; Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

A simple and robust protocol to establish a patient-derived HCC tumor spheroid.

(A) Experimental approach. HCC tissue and patient serum were processed to generate tumor spheroids that were used for characterization and perturbation studies. (B) Tumor spheroid formation. Aggregation of cells was observed, on average, 4 days after seeding. Cell compaction and tumor spheroid generation were observed, on average, after 7 days. Three representative examples are shown (MOTIC AE2000 Lordill, 10x). (C) Tumor spheroid viability. Viability was assessed by measurement of ATP levels and was stable at least for 7 days. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4, three independent experiments). (D) Homogenous tumor spheroid formation. To show homogeneity in sphere generation, images of tumor spheroid formation for 10 tumor spheroids generated in 384-well plates is shown (MOTIC AE2000 Lordill, 10x). (A) created with BioRender (biorender.com). HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; RLU, relative light unit.

Next, we applied this protocol to a large panel of surgical resections from a cohort of patients with various etiologies and grades of HCC (Tables S1 and S2). Tumor spheroids were successfully generated independently of etiology and tumor grades, with an overall success rate of ∼90% when using fresh tissues (see Methods in the supplementary information online). Tumor spheroid generation failure resulted from the poor quality of the tissue or necrotic tissue, from which only a low fraction of living cells was recovered after dissociation. The procedure was also successfully applied to cryopreserved HCC tissues (Tables S1 and S2), but with a more limited success rate resulting from cell death after thawing in some cases.

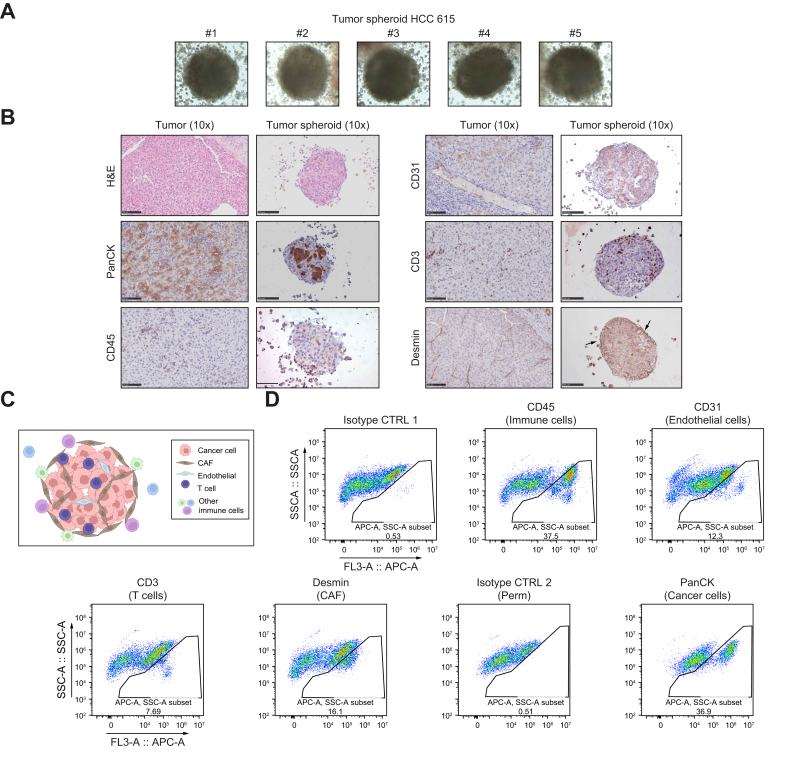

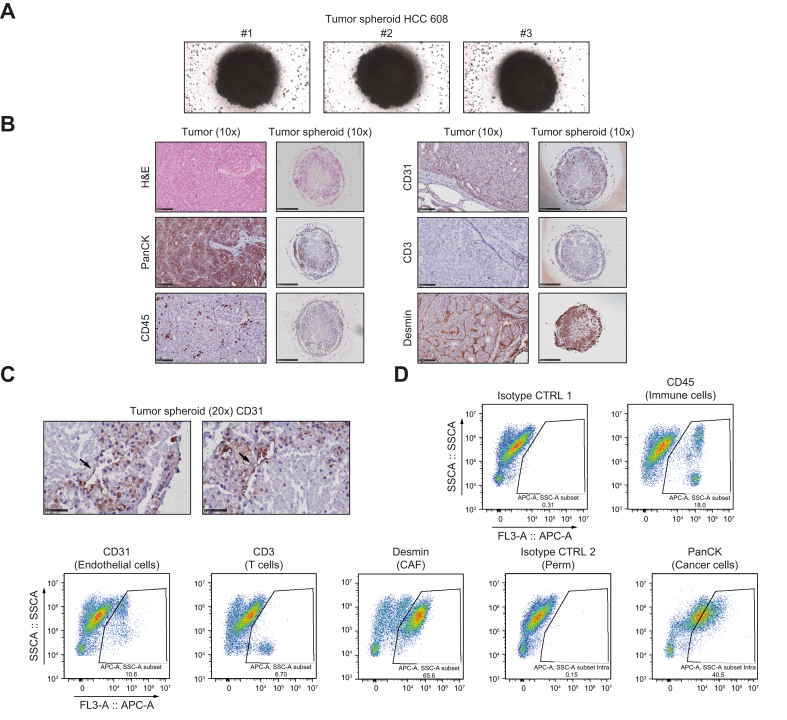

Tumor spheroids retain the original tumor features, including the main HCC cell compartments and TME

To characterize the model, we established IHC and H&E staining protocols. To demonstrate that our tumor spheroid system reflected patient heterogeneity in cell composition and structure, we selected two cases of moderately differentiated HCC that had arisen on normal liver (HCC 615) or cirrhotic tissue (HCC 608). For processing and fixation, tumor spheroids were embedded in hydrogel (Fig. 2, Fig. 3A) (see Methods in the supplementary information online). IHC analyses using established markers11,12 showed that the tumor spheroids contained epithelial cancer cells (pan-cytokeratin, PanCK) and different nonparenchymal cells, including CD45+ immune cells, CD3+ T cells, CD31+ endothelial cells, and Desmin+ cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs; Fig. 2, Fig. 3B). Moreover, H&E and IHC stainings performed side-by-side on the original tumor and tumor spheroids demonstrated that the spheroids self-organized in a compact structure mimicking that of the original tumor (Fig. 2, Fig. 3B). As an example, analysis of HCC 615 showed an organization of cancer cells in islets surrounded by Desmin+ CAFs with infiltration of CD3+ cells (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the corresponding tumor spheroids showed a similar organization (Fig. 2B, schematized in Fig. 2C). CD31+ endothelial cells were detected within the tumor spheroids, with organization into vessel-like structures in a patient-dependent manner (Fig. 2, Fig. 3B,C).

Fig. 2.

Tumor spheroids contain the main HCC cell compartments and self-organize as tumor-like structures (case HCC 615).

(A) Representative images of tumor spheroids in hydrogel before FFPE inclusion. Surrounding cells correspond to immune cells. Cells were imaged after 5 days of culture (MOTIC AE2000 Lordill, 10x). (B) Side-by-side H&E stainings and IHC analysis of the original tumor and corresponding tumor spheroids. Scale bars = 100 μm. (C) Model of tumor spheroid organization. (D) Analysis of different cell compartments in tumor spheroids by flow cytometry. CD45+ indicates immune cells, CD3+ indicates T cells, CD31+ indicates endothelial cells, Desmin+ indicates cancer-associated fibroblasts, and PanCK+ indicates epithelial cancer cells. (C) created with BioRender (biorender.com). FFPE, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IHC, immunohistochemistry; PanCK, pan-cytokeratin.

Fig. 3.

Tumor spheroids contain the main HCC cell compartments and self-organize in a tumor-like structure (case HCC 608).

(A) Representative images of tumor spheroids in hydrogel before FFPE inclusion. Cells were imaged after 5 days of culture (MOTIC AE2000 Lordill, 10x). (B) Side-by-side H&E stainings and IHC analysis of the original tumor and corresponding tumor spheroids. Scale bars = 100 μm. (C) High magnification of CD31 staining showed that endothelial cells organized in vessel-like structures in tumor spheroids. Scale bars = 50 μm. (D) Analysis of different cell compartments in tumor spheroids by flow cytometry. CD45+ indicate immune cells, CD3+ indicate T cells, CD31+ indicate endothelial cells, Desmin+ indicate cancer-associated fibroblasts, and PanCK+ indicate epithelial cancer cells (arrows). FFPE, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; PanCK, pan-cytokeratin.

Analyses of the tumor spheroid cell composition by flow cytometry using the same cell markers confirmed the presence of the main HCC cell compartments in the tumor spheroids with variable proportions (Fig. 2, Fig. 3D). Interestingly, while CD45+ immune cells were detected by flow cytometry, IHC analyses revealed that immune cells either infiltrated the spheres (CD3+ T cells) or were present at the periphery of the tumor spheroids (Fig. 2, Fig. 3D).

Importantly, further flow cytometry analyses of the original tissue and the corresponding tumor spheroids showed that the proportion of the different cell compartments was preserved in tumor spheroids (Figs. S2 and S3; summarized in Table S3). These results indicate that our approach did not lead to enrichment of a particular cell population but included all cell populations that were present in the original liver tissue at the time of sampling. Tumor spheroids generated from different donors harbored cell population proportions that were specific to each individual at the time of collection, reflecting HCC tissue heterogeneity among patients (compare HCC 544 and HCC 576 in Figs. S2 and S3, and Table S3,). A high proportion of immune cells led to variation in tumor spheroid size and shape and less compaction (compare HCC 544 and HCC 576 in Fig. 1B).

Next, we studied whether the cancer cell phenotype was preserved in tumor spheroids. We analyzed a HCC subset that expressed epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EPCAM), a progenitor marker associated with stem cell features.13 IHC and flow cytometry analysis showed that EPCAM expression on cancer cells was preserved in tumor spheroids generated from EPCAM+ HCC (Figs. S2–S4). We further studied the endothelial compartment and observed that the proportion of CD31+ endothelial cells differed between the original tumor and tumor spheroids (Table S3). This difference could be explained by the ability of endothelial cells to form, or not, vessel-like structures within the spheres (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

Together, our results showed that the patient-derived tumor spheroid model included the main HCC cell compartments, retained the original tumor features, and preserved the interindividual heterogeneity of HCC.

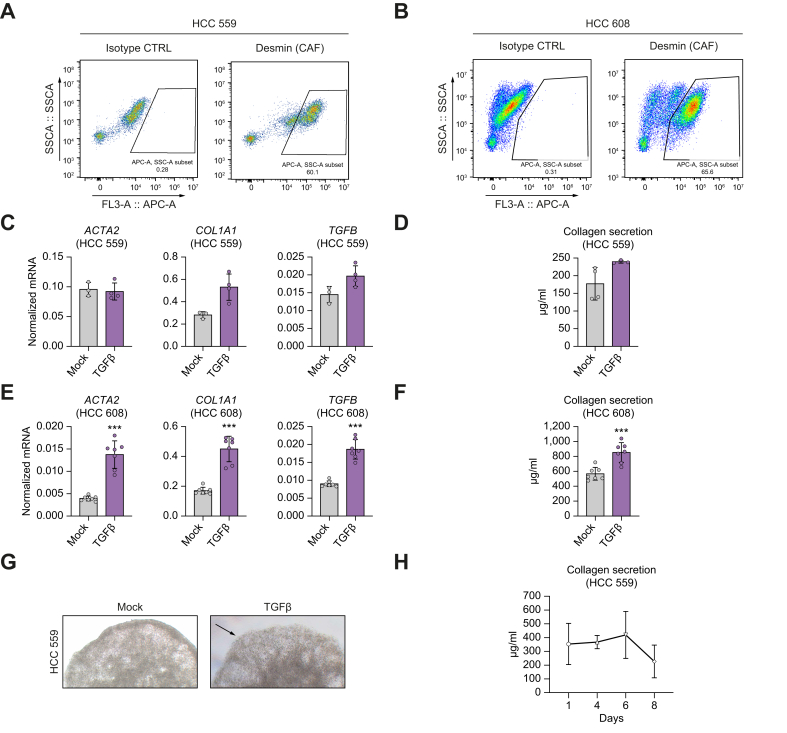

Tumor spheroids comprise functional CAFs producing ECM

CAFs are a central component of the TME with several functions, including ECM secretion and remodeling as well as cytokine/growth factor production.14 To further investigate tumor spheroid formation in a scaffold-free approach, we analyzed CAF function and ability to produce ECM components in our tumor spheroids. Flow cytometry analysis using Desmin as a marker of activated fibroblasts and CAFs and analysis of ACTA2 (encoding alpha smooth muscle actin) expression by qRT-PCR12 confirmed the presence of CAFs in the tumor spheroids (Fig. 4A–E).

Fig. 4.

Tumor spheroids contain functional CAFs.

(A,B) Tumor spheroids from two donors, HCC 559 (A) and 608 (B), were dissociated and analyzed by flow cytometry using Desmin as a CAF marker. (C–G) Effect of TGFβ treatment on tumor spheroids. Tumor spheroids were treated with TGFβ for 24 h. (C,E) Fibrotic gene expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD of normalized mRNA expression. HCC 559 n = 4; HCC 608 n = 7; ∗∗∗p <0.001 (two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test). (D,F). Collagen secretion was measured at day 7 by colorimetric assay in culture supernatant. Data are presented as mean ± SD of collagen secretion. HCC 559 n = 4; HCC 608 n = 8; ∗∗∗p <0.001 (two-tailed unpaired t test) (G) After TGFβ stimulation, tumor spheroids were imaged using MOTIC AE2000, Lordill (20x). (H) Collagen secretion from tumor spheroids was stable for at least 7 days. A kinetic experiment was performed without treatment using tumor spheroids. Data are presented as mean ± SD of collagen secretion (n = 3 for each day, one representative experiment out of two is shown). ACTA2, Actin alpha 2, smooth muscle; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; COL1A1, collagen type I alpha 1 chain; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

To demonstrate that these CAFs were functional, we stimulated tumor spheroids with TGFβ and assessed fibrotic marker expression and collagen secretion. We observed an increase in collagen expression and secretion in the culture supernatant (Fig. 4D,F,G) associated with changes in tumor spheroid morphology at the periphery (Fig. 4G). Moreover, kinetic experiments showed that functional CAFs produced collagen up to 1 week after tumor spheroid generation (Fig. 4H). ECM protein secretion by fibroblasts is likely to have contributed to aggregation of the different cell types and generation of stable tumor spheroids in the absence of scaffold.

Serum from patients with HCC facilitates tumor spheroid generation and preserves TME

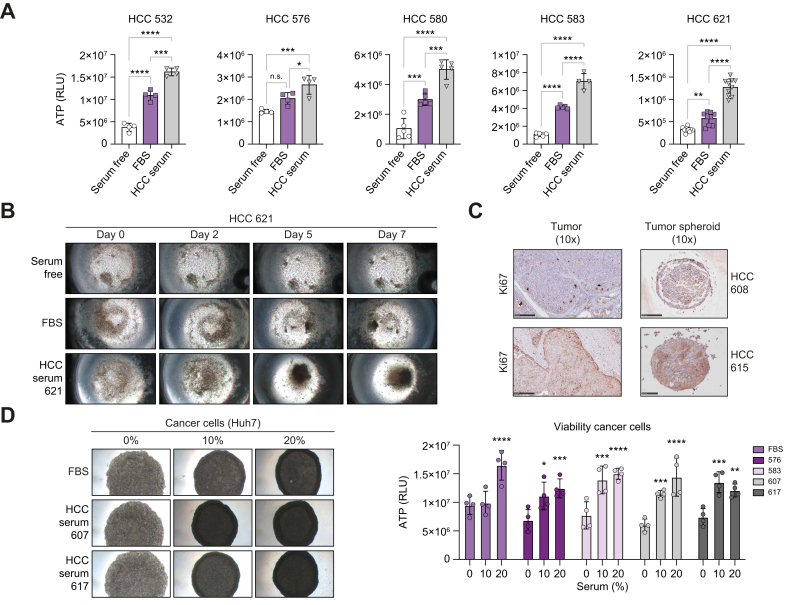

In cell culture, serum is widely used to not only provide growth factors, but also promote cell adhesion.15 Therefore, we analyzed the effect of FBS compared with sera from patients with HCC on the tumor spheroid phenotype. The presence of autologous patient serum robustly improved the cell viability of the tumor spheroids from different donors compared with FBS (Fig. 5A). Moreover, kinetic experiments showed that the presence of HCC serum robustly facilitated cell aggregation and compaction into spheres (Fig. 5B). Of note, HCC serum did not induce cell proliferation of a specific cell compartment within the tumor spheroids, as confirmed by Ki67 stainings (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Sera from patients with HCC facilitate tumor spheroid aggregation and preserve tumor spheroid viability.

(A,B) Autologous sera from patients with HCC improve tumor spheroid viability. Tumor spheroids were generated from different HCC tissues without serum or in the presence of FBS or autologous serum from patients. Viability was assessed by measuring ATP levels. Data are presented as mean ± SD of ATP quantity (HCC 532, 576, and HCC 583 n = 4; HCC 580 n = 5; HCC 621, n = 10); ∗p = 0.05; ∗∗p = 0.005; ∗∗∗p = 0.0001; ∗∗∗∗p <0.0001 (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). (B) Autologous sera from patients with HCC induced tumor spheroid formation. Timeline of tumor spheroid formation is shown in serum-free conditions, and in the presence of FBS or HCC serum. Aggregation of cells was observed after 5 days only in the presence of HCC serum. Cell compaction was observed 7 days after seeding (MOTIC AE2000 Lordill, 10x). (C) IHC staining of the proliferation marker Ki67 in the original tumor and corresponding tumor spheroids in the presence of HCC serum. (D) Sera from patients with HCC improved compaction of Huh7 cell 3D culture. (Left) Huh7 spheroid culture performed in serum-free conditions, or in the presence of FBS or HCC serum from different donors at 10% or 20% (MOTIC AE2000 Lordill, 10x). (Right) Viability assessed by measurement of ATP levels (day 3). Data are presented as mean ± SD of ATP quantity (n = 4 for each condition). Serum 10% and 20% were compared with serum free for each condition; ∗p = 0.05; ∗∗p = 0.005; ∗∗∗p <0.0005, ∗∗∗∗p <0.0001 (2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IHC, immunohistochemistry; RLU, relative light unit.

Next, we investigated the effect of sera from patients with HCC on the phenotype and function of the individual HCC cell compartments and TME components. As a simplified model of HCC cancer cells, we first used Huh7 cells cultured in 3D. Similar to observations in patient-derived tumor spheroids, HCC serum improved cell compaction in 3D (Fig. 5D). However, it did not lead to Huh7 cell proliferation compared with FBS, in line with Ki67 staining (Fig. 5C,D). It is likely that HCC serum preserved epithelial cancer cell viability in tumor spheroids by allowing cell aggregation and survival rather than by inducing epithelial cancer proliferation.

We next used LX2 stellate cells as a simplified model of fibroblasts, co-cultured in 3D with Huh7 cells and increasing concentrations of sera from patients with HCC or FBS (Fig. 6A). Sera from patients with HCC triggered stellate cell activation and CAF-like phenotype, as shown by the change in spheroid morphology and increase in ACTA2 and COL1A1 (encoding collagen type I alpha 1 chain) expression independently from the etiology (Fig. 6A–C; Fig. S5A–D). Ten to 20% of patient serum was sufficient to obtain this phenotype. Importantly, this phenotype was only observed with sera from patients with HCC and not with sera from healthy patients, indicating that soluble factors specific from HCC led to fibroblast activation (Fig. S6). Increase in COL1A1 expression in patient-derived tumor spheroids confirmed that HCC serum preserves CAF activation in the spheres (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

Sera from patients with HCC preserve the TME phenotype.

(A–C) Effect of sera from patients with HCC on Huh7/LX2 spheroids. (A) Spheroids from Huh7/LX2 (80-20%) cells were generated in absence of serum or increasing concentrations of FBS or sera from patients with HCC. After 72 h, tumor spheroids were imaged using MOTIC AE2000, Lordill (4x). (B) Viability was assessed by measuring ATP levels. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4 for each condition); ∗p <0.05; two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (compared with serum-free condition). (C) Stellate cell activation was assessed by measuring ACTA2 and COL1A1 expression by qRT-PCR. One representative experiment out of three is shown (see also Fig. S5). Data are presented as mean ± SD of normalized mRNA relative quantity (n = 3 for each condition). (D) Sera from patients with HCC induce macrophage differentiation in TAM-like cells. THP1-derived macrophages were incubated in presence of 10% FBS or sera from patients with HCC. After 3 days, cells were imaged using MOTIC AE2000, Lordill (20x) and macrophage phenotype was characterized by measuring different TAM markers by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD of normalized mRNA relative quantity (n = 4 for each condition). One representative experiment out of three is shown (see also Fig. S7); ∗p <0.05; two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. (E,F) Sera from patients with HCC preserve the tumor spheroid TME phenotype. Tumor spheroids were cultured in presence of FBS (partial sphere formation only) and of HCC serum. Different marker expression was assessed by qRT-PCR (ACTA2 and COL1A1 for CAFs (E) and CD163 and TNFA for TAMs (F)). Data are presented as mean ± SD of normalized mRNA relative quantity (n = 5 for each condition); ∗p <0.05; two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. (G) HCC serum prevents T cell activation in culture. CD3+ T cells were isolated from patient HCC tumors and grown in serum-free conditions (SF), in presence of FBS or of autologous sera from patients with HCC. T cell activation marker expression was assessed by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD of normalized mRNA relative quantity (n = 3 for each donor). Two representative experiments out of four are shown (see also Fig. S9A). ACTA2, Actin alpha 2, smooth muscle; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; COL1A1, collagen type I alpha 1 chain; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IHC, immunohistochemistry; RLU, relative light unit; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; TME, tumor microenvironment.

We used a differentiated monocyte-derived cell line (THP1) as a model of macrophages, finding that HCC sera induced phenotypic changes in macrophages (Fig. 6D; Fig. S7A and B). Further investigation indicated differentiation of THP1-derived macrophages into tumor-associated macrophage (TAM)-like cells, as demonstrated by an increase in CD204, CD206, CD163, and IL10 expression (Fig. 6D; Fig. S7A and B). Interestingly, the expression of these markers is often associated with tumor growth and poor prognosis in patients.16,17 Macrophage differentiation in TAM was only observed in the presence of sera from patients with HCC and not sera from healthy patients, demonstrating the specific effects of HCC serum (Fig. S7C). Of note, CD163 expression in patient-derived tumor spheroid showed only a trend in increase, most likely because of the robust basal expression of CD163 in patient TAMs (Fig. 6F).16,17 The decrease in TNFA expression suggests maintenance of an immunosuppressive milieu in tumor spheroids (Fig. 6F).

Finally, we analyzed the effect of HCC serum on T cell phenotype in tumor spheroids. We isolated CD3+ T cells from HCC tumors from patients (Fig. S8) and grew them in serum-free conditions, in the presence of FBS or patient autologous serum. As a readout, we measured the expression of early (CD69) and middle (IL2RA/CD25 and IFNG) T cell activation markers.18 Addition of FBS to the culture medium induced activation of T cells compared with serum-free conditions, as shown by the constant increase in IL2RA/CD25 and IFNG expression among the different donors (Fig. 6G; Fig. S9A). Increase in CD69 expression in the presence of FBS was patient dependent (Fig. 6G; Fig. S9A). By contrast, T cell activation was not observed following the addition of patient autologous serum, indicating that HCC serum was superior to FBS for maintenance of T cell phenotypes in tumor spheroids. The effect of FBS and HCC serum on T cells was confirmed at protein level by analysis of the CD3+ cell compartment in tumor spheroids by flow cytometry (Fig. S9B–D).

Collectively, these results indicate that the use of sera from patients with HCC facilitates tumor spheroid generation and is superior to FBS in maintaining the TME phenotype ex vivo.

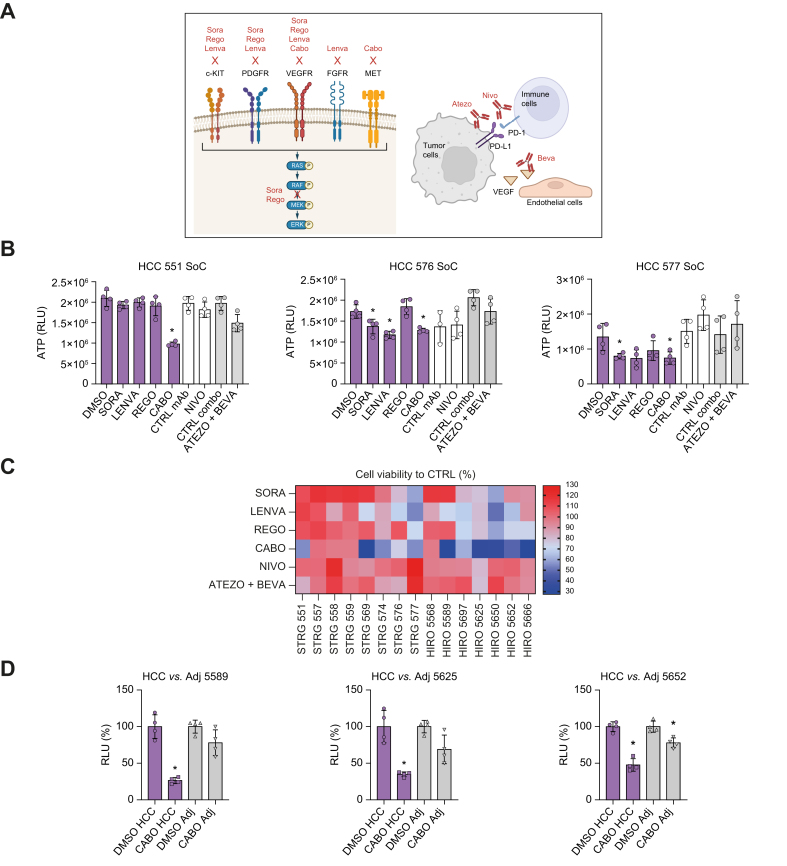

HCC tumor spheroids show heterogeneous responses to FDA-approved drugs

Next, we investigated whether our model can be applied for therapeutic response. As proof of concept, we treated HCC tumor spheroids with a panel of FDA-approved compounds (Fig. 7A). Tumor spheroids were generated from tissues from 15 patients with HCC and treated with multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), as well as nivolumab, an anti- PD-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb), and the combination of atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1 mAb) and bevacizumab (anti-VEGF mAb). Before their application in the patient tumor spheroid model, the drug concentrations inhibiting targeted signaling pathways were determined in a Huh7 3D spheroid model (Fig. S10). The optimal concentrations for the mAbs were selected according to the literature.19,20

Fig. 7.

HCC tumor spheroids show heterogeneous responses to FDA-approved drugs.

(A) Schematic of the molecular target of selected FDA-approved anti-HCC drugs. (B,C) Drug screening in tumor spheroids. Tumor spheroids were generated from tissues from 17 patients with HCC (Strasbourg and Hiroshima biobank) and treated with different FDA-approved drugs for 3 days. Viability was assessed by measurement of ATP levels. (B) Data are presented as mean ± SD of ATP quantity (n = 4) for three representative HCC tumor spheroids; ∗p <0.05, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (TKI vs. DMSO, mAb vs. CTRL mAb). (C) Percentage of cell viability compared with control (DMSO or CTRL mAbs); n = 4 for 15 HCC tumor spheroids. (D) Anti-HCC drug response is higher in HCC tumor spheroids compared with spheroids generated from adjacent nontumoral tissues. Data are presented as mean ± SD of percentage of cell viability vs. respective controls (n = 4, three independent experiments); ∗p <0.05, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (Cabo vs. DMSO). (A) Created with BioRender (biorender.com). Atezo, atezolizumab; Beva, bevacizumab; Cabo, cabozantinib; CTRL, control; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; Lenva, lenvatinib; mAb, monoclonal antibody; Nivo, nivolumab; Rego, regorafenib; SoC, standard of care; Sora, sorafenib.

First, we observed a heterogeneous response to TKIs, likely reflecting inter- and intra- individual tumor phenotypes (Fig. 7B,C). As an example, HCC 577 was sensitive to all tested TKIs, whereas HCC 551 was sensitive to only cabozantinib. HCC 576 harbored an intermediate phenotype and showed sensitivity to sorafenib, lenvatinib, and cabozantinib, but resistance to regorafenib (Fig. 7B,C). The response rate obtained with sorafenib was 13.33%, which reflects response rates observed clinically in patients3 (Fig. 7C). Moreover, lenvatinib showed a superior response compared with sorafenib, as also observed in patients21 (Fig. 7C). A robust response rate was observed for cabozantinib, which correlates with a recent meta-analysis demonstrating superiority of cabozantinib in second-line settings22 (Fig. 7C).

To further confirm the validity of the model for the investigation of chemotherapeutic agents, we generated spheroids from adjacent nontumoral liver tissues using the same approach and compared treatment responses with the corresponding tumor spheroids (Fig. 7D). As a proof-of-concept study, we selected HCC tissues responding to cabozantinib (Fig. 7C). Cabozantinib strongly decreased cellular viability only in tumor spheroids, with minor or absent effects on the adjacent nontumoral spheroids (Fig. 7D), demonstrating the specificity of the tumor spheroid model for tumor-targeting drugs.

Next, we compared TKI treatment response obtained on tumor spheroids generated from fresh and cryopreserved tissues from the same patient. Treatment response and cell viability were comparable between fresh and cryopreserved tissues when tumor spheroids were successfully formed (Fig. S11A and B). However, cryopreservation in some cases resulted in failure of proper tumor spheroid formation, leading to heterogeneous treatment response (Fig. S11C and D). Therefore, assessment of the quality of tumor spheroid generation and viability before treatment is essential to obtain robust, reproducible results (see Methods in the supplementary information online).

Finally, tumor spheroids were treated also with immunotherapies. A consistent but low-level response was observed for four out of 15 of the tumor spheroids tested (Fig. 7C). To validate the specific antitumor efficacy of mAbs in our model, we measured target expression in tumor spheroids. Flow cytometry analysis after nivolumab treatment demonstrated target engagement on CD3+ T cells (Fig. 8A,B). Moreover, treatment with bevacizumab resulted in a robust decrease in VEGF levels in tumor spheroid culture supernatants (Fig. 8C), confirming target engagement.

Fig. 8.

HCC tumor spheroids respond to immunotherapy.

(A,B) Tumor spheroids from HCC 569 and HCC 580 were treated with nivolumab or CTRL mAb for 6 days. At day 6, they were dissociated and analyzed by flow cytometry. Gating shows selection of a specific CD3+ T cell population among total cells. PD-1 was detected as a T cell exhaustion marker targeted by nivolumab. (C) Tumor spheroids from HCC 600 and 608 were treated with standard-of-care combination therapy comprising atezolizumab and bevacizumab for 6 days. VEGF levels were measured in culture supernatants by ELISA assay. Data are presented as mean ± SD of VEGF quantity; ∗∗∗p <0.0005; ∗∗∗∗p <0.0001 (two tailed unpaired t test). CTRL, control; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; mAb, monoclonal antibody; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Discussion

In this study, we established a simple, patient-derived, multicellular HCC spheroid model recapitulating tumor heterogeneity and TME for HCC drug discovery and development. While HCC spheroid systems have been described previously,[23], [24], [25], [26], [27] the conceptual advances and innovation of the model established in this study relate to the combination of tumor spheroids with sera from patients with HCC and inclusion of the TME.

Characterization of the tumor spheroids using different assays and markers suggests that our system is representative of key features and phenotypes of the original tumors. Side-by-side comparison of the tumor and tumor spheroids demonstrated that they included the main HCC cell compartments and that the proportions were preserved. Moreover, using EPCAM as an example, the cancer cell phenotype was preserved in the tumor spheroids. Finaly, we showed that the tumor spheroid self-organized into a 3D structure that was very close to the original tumor. Thus, our approach enables the generation of functional tumor spheroids for drug proof-of-concept studies within only a few days, with high and stable viability.

HCCs are characterized by significant intratumor and interpatient heterogeneity.5 Compared with 3D cell culture models, the tumor spheroid system preserved original tumor features and recapitulated this patient heterogeneity. Over the past decade, HCC organoids have emerged as a major technical advancement to study HCC biology.8 However, their use is limited by a low success rate of ∼27%.8 Moreover, HCC organoids can only easily be established from high-grade HCC with a high proliferative index.8 Our model overcomes these limitations by enabling tumor spheroid generation regardless of grade and etiology with a high success rate. In contrast to organoids, tumor spheroids also included stromal, endothelial, and immune cells.8 Finally, we used a matrix-free approach to generated tumor spheroids, based on the self-aggregation capabilities of cells. Therefore, our model overcomes the limitations of previously described matrix-based methods, such as the variability of matrix batches, reproducibility issues, high costs, and limitations to drug or large molecule diffusion.28

Recently, precision cut tumor slices (PCTSs) have also emerged as a major breakthrough to study HCC biology and for drug development.29 However, generation of PCTSs is dependent on the availability of fresh HCC specimens.29 By contrast, tumor spheroids can be generated from frozen tissues. Moreover, PCTSs likely only partially reproduce the hypoxic TME of HCC tumors.29 Spheroid cultures have been shown to model hypoxia by inducing an oxygen gradient from the periphery to the hypoxic core of the spheroid.10 Finally, in contrast to PCTSs, the tumor spheroid system can be more easily adapted to high-throughput studies using screening formats with homogenous sphere formation.

As with any model, patient-derived tumor spheroids have their limitations. In contrast to organoids, tumor spheroids cannot be passaged. Cell death during cryopreservation of HCC tissues can lead to selection of specific cell subtypes after thawing and failure of tumor spheroid generation. Therefore, the quality of HCC cryopreservation is crucial for success. Finally, as for any model system, it is unlikely that all aspects of the patient tumor are represented in the tumor spheroids. Combining investigations applying the tumor spheroids with other HCC models will address this limitation.

The other innovation is the use of autologous patient sera to generate spheroids. Hepatocarcinogenesis is accompanied by secretome modification. The secretome is present in patient sera, including tumor-associated proteins and immune mediators with key roles in tumorigenesis;30,31 thus, HCC serum may mimic the HCC secretome. Our data demonstrated that sera from patients with HCC facilitated cell aggregation and was key to preserving high cell viability in patient-derived tumor spheroids. Moreover, it contributed to the preservation of CAFs and the immune cell phenotype as well as an immunosuppressive TME, most likely through different soluble factors (i.e. cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular vesicles). These features offer a unique opportunity to study cellular communication within the cellular and noncellular TME.

By using FDA-approved drugs in proof-of-concept studies, we demonstrated that this serum-tumor spheroid system enables study of the efficacy of anti-HCC therapies in authentic patient material. A limitation of the model was that responses to CPIs were detectable but at a low magnitude. It is conceivable that CPIs do not induce robust cancer cell mortality in tumor spheroids because of the limited number of immune cells in the spheres (no infiltration/recruitment of new cells is possible in this model) or the absence of tertiary lymphoid structures. Nevertheless, target engagement assays suggest that the tumor spheroid model will contribute to understanding the mechanism of action of immunotherapy-based treatments.

The next step will be a prospective study to compare treatment responses in tumor spheroids with clinical responses in patients from whom the material was derived. However, given that the material from patients used in this study was from liver resections as part of a surgical curative approach, retrospective data on the response to systemic therapies of the patients, from whom the resections were obtained, are not available. Nevertheless, the opportunity to assess treatment responses of tumor spheroids from liver biopsies of patients undergoing future treatment may harness our model for future precision medicine.

Concluding remarks

In conclusion, the HCC serum-tumor spheroid system based on authentic patient tissue and autologous sera offers new perspectives to improve HCC drug discovery and development, including compounds targeting the TME. Based on these opportunities and perspectives, the serum-tumor spheroid model will likely contribute to improve outcomes for patients with HCC.

Abbreviations

ACTA2, actin alpha 2, smooth muscle; Atezo, atezolizumab; Beva, bevacizumab; Cabo, cabozantinib; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; COL1A1, collagen type I alpha 1 chain; CPI, checkpoint inhibitors; CTRL, control; ECM, extracellular matrix; EPCAM, epithelial cell adhesion molecule; HBSS, Hanks' balanced salt solution; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IHC, immunohistochemistry; Lenva, Lenvatinib; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated liver disease; Nivo, nivolumab; PanCK, pan-cytokeratin; PCTS, precision cut tumor slices; PD-1, programmed cell death-1; Rego, regorafenib; RLU, relative light unit; SoC, standard of care; Sora, sorafenib; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; TME, tumor microenvironment; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Financial support

This work was supported by the European Union (ERC-AdG-2020-FIBCAN #101021417 to T.F.B.), and ARC Foundation Paris and IHU Strasbourg (TheraHCC2.0 IHUARC2019 to T.F.B.). This work was published under the framework of the LABEX ANR-10-LABX-0028_HEPSYS and Inserm Plan Cancer and benefits from funding from French state funds managed within the ‘Plan Investissements d’Avenir’ and by the ANR (ANR-10-IAHU-02 and ANR-10-LABX-0028), along with French state funds managed by the ANR within the France 2030 program (ANR-21-RHUS-0001 DELIVER). N.A.’s PhD was partially funded by Région Grand Est, France. This work of the Interdisciplinary Thematic Institute IMCBio+, as part of the ITI 2021-2028 program of the University of Strasbourg, CNRS and Inserm, was supported by IdEx Unistra (ANR-10-IDEX-0002), and by SFRI-STRAT’US project (ANR 20-SFRI-0012) and EUR IMCBio (ANR-17-EURE-0023) under the framework of the French Investments for the Future Program. K.C. was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under grant no. 23fk0210122h0001.

Authors’ contributions

Initiated and coordinated the study: EC, TFB, CS. Designed and performed the experiments and/or analyzed the data: EC, NA, SCD, MP, MO, CG, NR. Organized the collection of liver tissues: EC, SCD, AS, CS. Provided liver tissues: FG, EF, PP, , HO, HA and KC. Provided clinical information: EF, FG, AS. Initiated the methodology of patient-derived spheroids: HTFD. Conceptualized and wrote the manuscript: EC, TFB, CS.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest that pertain to this work.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Centre de Ressources Biologiques (CRB)/Biological Resource Centre, Strasbourg, France, for the management of patient-derived liver tissues and access to clinical information (Céline Roth, Etienne Bergmann, Mihalea Onea, and Marie Pierrette Chenard).

Footnotes

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2024.101252.

Contributor Information

Emilie Crouchet, Email: ecrouchet@unistra.fr.

Thomas F. Baumert, Email: thomas.baumert@unistra.fr.

Catherine Schuster, Email: catherine.schuster@unistra.fr.

Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Vogel A, Meyer T, Sapisochin G, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2022;400:1345–1362. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang DQ, El-Serag HB, Loomba R. Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:223–238. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00381-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ducreux M., Abou-Alfa G.K., Bekaii-Saab T., et al. The management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Current expert opinion and recommendations derived from the 24th ESMO/World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer, Barcelona, 2022. ESMO Open. 2023;8 doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang C., Zhang H., Zhang L., et al. Evolving therapeutic landscape of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:203–222. doi: 10.1038/s41575-022-00704-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barcena-Varela M., Lujambio A. The endless sources of hepatocellular carcinoma heterogeneity. Cancers. 2021;13:2621. doi: 10.3390/cancers13112621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng H., Zhuo Y., Zhang X., et al. Tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: key players for immunotherapy. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2022;9:1109–1125. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S381764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lam M., Reales-Calderon J.A., Ow J.R., et al. In vitro 3D liver tumor microenvironment models for immune cell therapy optimization. APL Bioeng. 2021;5 doi: 10.1063/5.0057773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nuciforo S., Heim M.H. Organoids to model liver disease. JHEP Rep. 2021;3 doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deville SS, Cordes N. The extracellular, cellular, and nuclear stiffness, a trinity in the cancer resistome-a review. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1376. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunti S, Hoke ATK, Vu KP, et al. Organoid and spheroid tumor models: techniques and applications. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:874. doi: 10.3390/cancers13040874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aizarani N, Saviano A, Sagar, et al. A human liver cell atlas reveals heterogeneity and epithelial progenitors. Nature. 2019;572:199–204. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1373-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin Z., Dong C., Jiang K., et al. Heterogeneity of cancer-associated fibroblasts and roles in the progression, prognosis, and therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:101. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0782-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoshida Y, Nijman SMB, Kobayashi M, et al. Integrative transcriptome analysis reveals common molecular subclasses of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7385–7392. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng B, Wu J, Shen B, Jiang F, Feng J. Cancer-associated fibroblasts and resistance to anticancer therapies: status, mechanisms, and countermeasures. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22:166. doi: 10.1186/s12935-022-02599-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Underwood PA, Bean PA, Mitchell SM, et al. Specific affinity depletion of cell adhesion molecules and growth factors from serum. J Immunol Methods. 2001;247:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong L-Q, Zhu X-D, Xu H-X, et al. The clinical significance of the CD163+ and CD68+ macrophages in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arvanitakis K, Koletsa T, Mitroulis I, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis, prognosis and therapy. Cancers. 2022;14:226. doi: 10.3390/cancers14010226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rea IM, McNerlan SE, Alexander HD. CD69, CD25, and HLA-DR activation antigen expression on CD3+ lymphocytes and relationship to serum TNF-α, IFN-γ, and sIL-2R levels in aging. Exp Gerontol. 1999;34:79–93. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(98)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C, Thudium KB, Han M, et al. In vitro characterization of the Anti-PD-1 antibody nivolumab, BMS-936558, and in vivo toxicology in non-human primates. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:846–856. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wieleba I, Wojas-Krawczyk K, Chmielewska I, et al. In vitro preliminary study on different anti-PD-1 antibody concentrations on T cells activation. Sci Rep. 2022;12:8370. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-12136-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang S, Wang Y, Yu J, et al. Lenvatinib as first-line treatment for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers. 2022;14:5525. doi: 10.3390/cancers14225525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park R, Lopes da Silva L, Nissaisorakarn V, et al. Comparison of efficacy of systemic therapies in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: updated systematic review and frequentist network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2021;8:145–154. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S268305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song H., Bucher S., Rosenberg K, et al. Single-cell analysis of hepatoblastoma identifies tumor signatures that predict chemotherapy susceptibility using patient-specific tumor spheroids. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4878. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32473-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song Y., Kim J-S, Kim S-H, et al. Patient-derived multicellular tumor spheroids towards optimized treatment for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:109. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0752-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q., Liu J., Yin W, et al. Generation of multicellular tumor spheroids with micro-well array for anticancer drug combination screening based on a valuable biomarker of hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:1087656. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.1087656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dituri F, Centonze M, Berenschot EJW, et al. Complex tumor spheroid formation and one-step cancer-associated fibroblasts purification from hepatocellular carcinoma tissue promoted by inorganic surface topography. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:3233. doi: 10.3390/nano11123233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaki MYW, Shetty S., Wilkinson AL, et al. Three-dimensional spheroid model to investigate the tumor-stromal interaction in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vis Exp. 2021;175 doi: 10.3791/62868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui X, Hartanto Y, Zhang H. Advances in multicellular spheroids formation. J R Soc Interface. 2017;14:20160877. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2016.0877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jagatia R, Doornebal EJ, Rastovic U, et al. Patient-derived precision cut tissue slices from primary liver cancer as a potential platform for preclinical drug testing. EBioMedicine. 2023;97:104826. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujiwara N, Kobayashi M, Fobar AJ, et al. A blood-based prognostic liver secretome signature and long-term hepatocellular carcinoma risk in advanced liver fibrosis. Med. 2021;2:836–850. doi: 10.1016/j.medj.2021.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uhlén M, Karlsson MJ, Hober A, et al. The human secretome. Sci Signal. 2019;12:eaaz0274. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaz0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors, upon reasonable request.