Summary

Background

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) may induce overlapping myositis/myasthenia gravis (MG) features, sparking current debate about pathophysiology and management of this emerging disease entity. We aimed to clarify whether ICI-induced (ir-) myositis and ir-MG represent distinct diseases or exist concurrently.

Methods

We performed a retrospective multicenter cohort study. Using the Paris University Hospitals database (n = 2,910,417), we screened all patients with International Classification of Diseases codes or free text related to myositis/MG signs and ICI (n = 620). ‘Ir-MG signs' were defined by fatigability, repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS) decrement, and/or acetylcholine receptor antibodies (AChR Abs).

Findings

Ir-MG signs were never observed in the absence of ir-myositis (pathological diagnosis (n = 12/14) or CK levels >8000 U/L (n = 2/14)). Among ir-myositis patients, fatigability (2%; n = 1/62) and RNS decrement (2%; n = 1/41) were demonstrated only in one patient with pre-existing MG. AChR Abs testing yielded positive results in 26% of ir-myositis patients (n = 14/53). We revealed that test results were already positive prior to ICI therapy (n = 8/9). Clinically, ir-myositis frequently presented with “MG-like” oculomotor disease (50%; n = 31/62), bulbar dysfunction affecting speech (29%; n = 18/62) and swallowing (42%; n = 26/62), and respiratory disorders (53%; n = 33/62). Extraocular and diaphragm muscles necropsies disclosed intense muscle inflammation (100%; n = 5/5).

Interpretation

In our extensive database, we found no evidence of isolated ir-MG, nor of clear neuromuscular junction dysfunction in ir-myositis. These findings suggest that patients with ir-MG suspicion frequently have ir-myositis and ir-MG might be rare. “MG-like” symptoms may stem from ir-myositis-specific predilection for oculo-bulbo-respiratory musculature. Indeed, we revealed florid inflammatory infiltration of the oculomotor and respiratory muscles. Additional studies are needed to confirm these results and to elucidate the role of pre-existing AChR Abs in ir-myositis.

Funding

None.

Keywords: Myositis, Myasthenia gravis, Immune checkpoint inhibitor, Immunotherapy, Immune-related adverse event, Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced myositis, Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced myasthenia gravis, Acetylcholine receptor antibodies, Biomarker, Autoimmunity

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

To characterize neuromuscular toxicities related to expanding immune checkpoint inhibitor exposure world-wide, we conducted a search on PubMed using the terms ‘myositis' or ‘myasthenia gravis’ (MG) and ‘immune checkpoint inhibitor’ (ICI), without language restrictions, from 2011, when the first ICI was approved by the Food and Drug Administration, to March 2022. We mainly identified case reports and case series. These published data have led to systematic reviews of the literature on ‘ICI-induced myasthenia gravis' and ‘ICI-induced myositis’, allowing for the perception of these two entities as distinct immune-related adverse events. Consequently, international consensus guidelines for management of MG have provided therapeutic recommendations for patients with ICI-induced MG. However, in most reported cases of ICI-induced MG, increased muscle enzyme levels were noted, suggesting muscle damage. On the other hand, described cases of ICI-induced myositis frequently exhibited oculomotor signs, which are very unusual in idiopathic myositis and typically suggestive of neuromuscular junction pathology. Furthermore, the presence of MG-related autoantibodies was regularly reported in ICI-induced myositis. Finally, some studies described cases of overlapping ICI-induced myositis and MG.

Added value of this study

We endeavored to clarify the spectrum of ICI-induced neuromuscular toxicity. The present retrospective cohort study was conducted using the Clinical Data Warehouse of the largest hospital trust in Europe (Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris). We systematically searched for patients with isolated and/or overlapping features of ICI-induced myositis and MG and provide a thorough characterization of these patients, including results of autoantibody testing in sera obtained prior to ICI exposure, and autopsies of the extraocular muscles and diaphragm.

We found no patients with isolated ICI-induced MG, nor evidence of novel neuromuscular junction transmission defect in patients with ICI-induced myositis. Anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies pre-exist in a quarter of ICI-induced myositis patients, demonstrating that they are not induced by ICI. In addition, we reveal florid inflammatory infiltration of the oculomotor and respiratory muscles, suggesting that “MG-like” symptoms may stem from ICI-induced myositis-specific predilection for oculo-bulbo-respiratory musculature.

Implications of all the available evidence

While not dismissing the possibility of ICI-induced neuromuscular junction pathology, this work suggests that isolated cases of ICI-induced MG may represent an entity whose significance should be reconsidered. In contrast, distinctive muscle involvement in ICI-induced myositis establishes it as a unique disease entity, warranting specific management. Notably, our findings highlight the potential significance of anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies as a biomarker for identifying patients that are at risk of developing ICI-induced myositis.

Introduction

“Immune checkpoints” constitute immuno-inhibitory signaling pathways that mediate negative regulation of T-cell activation (e.g., induction of T-cell anergy – for maintenance of peripheral tolerance,1, 2, 3, 4 or in the context of tumor cells, immune evasion).5 Blockade of these cell membrane receptor interactions by immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) leads to T-cell activation and restoration of anti-tumor T-cell activity.6,7

ICIs have been demonstrated to elicit sustained clinical responses in patients with previously untreatable, metastatic disease.8, 9, 10 This burgeoning pillar in oncotherapy has become the standard of care for an expanding plethora of indications, currently concerning over 40% of oncology patients.11 In addition, the ongoing development of novel ICIs anticipates increasing ICI exposure in the future.

The downside of “unleashing” endogenous immunity however, is triggering autoimmunity. ICIs induce immune-related adverse events (irAEs) in over half of cases, frequently leading to premature termination of therapy, disability, and mortality.8

Inflammatory myopathy (ir-myositis) and myasthenia gravis (ir-MG) are the first and the second most commonly reported neurological irAEs, respectively.12 Among all irAEs, ir-myotoxicity (ir-myositis and/or ir-myocarditis) exhibits the highest fatality rate.13

Besides higher mortality (>20%,13 and approaching 60% in presence of concurrent ir-myocarditis),14 ir-myositis differs substantially from its spontaneous counterpart by frequent (“MG-like”) oculomotor (ophthalmoparesis and/or ptosis, in half of patients) and bulbar involvement, and early respiratory failure.13,15,16 In addition, presence of acetylcholine receptor antibodies (AChR Abs) in a subset of patients may suggest concurrent neuromuscular junction disorder.15,17, 18, 19, 20 Indeed, in recent literature, there is conflicting data on whether ir-myositis and ir-MG represent distinct diseases or exist concurrently.13,15, 16, 17, 18

Distinguishing muscle from neuromuscular junction pathology is crucial in these patients, as it may influence selection of therapy (e.g., corticosteroids vs plasmapheresis vs intravenous immunoglobulin treatment,21 alternative immunosuppressive and biological agents, and possibly MG-specific symptomatic treatment). Notably, pioneering therapeutic approaches (e.g., immune checkpoint agonists and Janus kinase inhibitors) have recently shown promising results in ir-myotoxicity,22 raising the question whether such treatment strategies could also be employed in patients with ir-MG suspicion.

Our study aimed to clarify whether muscle and/or neuromuscular junction pathology underlies motor neuromuscular signs in patients treated with ICI. By unraveling pathophysiology of overlapping ir-myositis/MG features, we hope to pave the way for better prevention, recognition, and management of this rapidly emerging and fulminant disease entity, ultimately reducing patient disability and mortality.

Methods

Study design

A multicentric, retrospective cohort study was conducted using the Clinical Data Warehouse of the Greater Paris University Hospitals (Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, AP-HP), the largest hospital trust in Europe. Patients from Sorbonne University Hospitals (Pitié Salpêtrière, Tenon, Saint Antoine, and Charles Foix) were included. Final data extraction was performed in March 2022. Data collected during routine clinical care were analyzed by an expert team (LP, EM, HC). Additionally, results of electrodiagnostic studies and cardiac investigations were re-evaluated by a clinical neurophysiologist and cardiologist, respectively, from Pitié Salpêtrière University Hospital, tertiary referral center for neuromuscular disease. Approval for this study was granted by the AP-HP Scientific and Ethics Committee at Pitié Salpêtrière University Hospital (CSE-20-37-JOCARDITE; NCT04294771).

For comparison, a control group of MG patients was employed. Its constitution was approved by local ethics committees (RCB 2006-A00164-47 and 2010-A00250-39).

Patients

Patient selection process is summarized in Fig. 1. All patients were screened automatically for International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 codes or free text terms related to motor neuromuscular signs and ICI treatment. ICD-10 codes included those associated with myositis, myasthenia, myopathy, respiratory/diaphragm insufficiency, rhabdomyolysis, myalgia, diplopia, and ptosis (details provided in Supplementary Table S1). Free text terms included nivolumab, pembrolizumab, ipilimumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, avelumab, cemiplimab, and dostarlimab.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart.

Subsequently, medical reports retrieved during screening were analyzed manually to identify patients with ‘ir-motor neuromuscular disorder suspicion’, defined by any of the following signs occurring after ICI exposure: 1) oculomotor, bulbar, respiratory, or other muscle weakness or fatigability, 2) creatine kinase (CK) elevation (upper reference limit 140 U/L for females and 170 U/L for males), 3) decrement on repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS), or, 4) detectable AChR Abs.

Thereafter, we excluded patients with muscle weakness and/or CK elevation that was mild and transient and not suggestive of ir-myositis or ir-MG. Patients with muscle weakness and/or CK elevation more likely attributable to a diagnosis other than ir-myositis or ir-MG were additionally excluded.

Finally, ‘isolated ir-MG’ (ir-MG without concurrent ir-myositis) was defined by 1) fluctuating/fatigable muscle weakness, and/or decrement on RNS, and/or presence of AChR Abs, and, 2) absence of ir-myositis.

‘Ir-myositis’ (ir-myositis with or without concurrent ir-MG) was defined by 1) inflammatory infiltrates on muscle pathology, or if myopathology was not available, muscle weakness and CK elevation exceeding five times the upper reference limit, and 2) absence of a more likely, alternative diagnosis including dermatomyositis and anti-synthetase syndrome, based on expert opinion.

Ir-myocarditis diagnosis was based on previously defined criteria for ‘definite myocarditis’.22

Sex (classified as female or male) was self-reported at initial hospital visit.

Idiopathic, adult MG patients from a previously described French database,23 were included as a control group.

Muscle pathology

All muscle biopsies and post-mortem tissue from the diaphragm and rectus inferior, superior, and lateralis muscles were analyzed by a myopathology expert (SLL) in Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, tertiary referral center for neuromuscular disease, as described previously.16 In short, cryostat sections (7 μm) were stained by routine preparations, including hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemistry, with markers directed against major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I), C5b-9, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD20, and CD56. Pathological diagnosis of ir-myositis was based on presence of inflammatory infiltrates.

Electrodiagnostic studies

Electrodiagnostic evaluation was performed in Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, following standardized procedures. Myopathic findings were defined by abnormal spontaneous activity or polyphasic, short-duration, or low-amplitude motor unit potentials on concentric needle electromyography (EMG). Low frequency (3 Hz) RNS was performed in at least six nerves: the spinal accessory, facial, and anconeus nerves, bilaterally. Decremental response of more than 10% amplitude in at least one of the nerves tested was determined as evidence of neuromuscular junction dysfunction.

Antibody testing

Antinuclear, myositis-associated (anti-Ku, anti-PM-Scl100, anti-PM-Scl75, anti-Ro52, and anti-U1RNP), and myositis-specific (anti-Mi2A, anti-Mi2B, anti-TIF1γ, anti-MDA5, anti-NXP2, anti-SAE1, anti-SRP, anti-Jo1, anti-PL7, anti-PL12, anti-EJ, anti-OJ) Abs testing was performed with commercially available standard kits.16 AChR Abs testing was performed using an inhibition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (ELISA RSR TM AChRAb RSR Limited), as previously reported.22 Positive results for AChR Abs (>0·5 nmol/L) prompted additional AChR Abs assessment in serum samples obtained prior to ICI exposure. Muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) Abs testing (with a threshold for a positive result set at 0·40 U/mL) was performed using the MuSK-Ab ELISA kit from IBL International GmbH.

Statistical analysis

R statistical software (version 4.3.2) and GraphPad Prism were employed for data analysis and visualization. Descriptive analysis of clinical parameters is reported with absolute frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and with median and interquartile range (IQR) for quantitative variables.

Role of funding source

None.

Results

Absence of isolated ir-MG in patients with suspicion of motor neuromuscular toxicity

Among a total of 2,910,417 patients, we were not able to find any patient with ir-MG in absence of ir-myositis (Flowchart in Fig. 1). Fatigable/fluctuating muscle weakness and/or decrement on RNS were observed only in one patient. This one patient had diagnosis of MG prior to ICI treatment, and developed (pathologically proven) ir-myositis after ICI exposure.

AChR Abs (>0·5 nmol/L) were detected in this and 13 other patients, all of whom were diagnosed with ir-myositis, based on myopathology (n = 12/14) or, in absence of muscle biopsy, CK levels higher than 8000 U/L (n = 2/14).

In ir-myositis patients, muscular inflammatory infiltrates may explain “MG-like” symptoms

We retrieved 62 patients with ir-myositis, with or without concurrent ir-MG. An overview of basic characteristics, disease course and ancillary investigations is provided in Table 1, Table 2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with ir-myositis ± MG (n = 62).

| Baseline characteristics | No. (%) or median [IQR] |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70 [IQR 60–76] |

| Male, female | 37 (60%), 25 (40%) |

| History of autoimmune disease | 4 (6%) |

| Indication for ICI therapy: | |

| Skin cancer | 20 (32%) |

| Pulmonary cancer | 17 (27%) |

| Other | 25 (40%) |

| Metastatic disease at ICI onset | 39 (63%) |

| Oncologic treatment prior to ICI therapy | 48 (77%) |

| ICI treatment regimen: | |

| Monotherapy | 48 (77%) |

| Anti-PD1 | 42 (68%) |

| Anti-PDL1 | 6 (10%) |

| Combination therapy: | 14 (23%) |

| Anti-PD1 + anti-CTLA4 | 13 (21%) |

| Anti-PD1 + anti-LAG3 | 1 (2%) |

Table 2.

Disease course and ancillary investigations in patients with ir-myositis ± MG (n = 62).

| Disease course | No. (%) or median [IQR] |

|---|---|

| Time from ICI exposure to symptom onset (days) | 27 [18–43] |

| Time from symptom onset to last follow-up (days) | 315 [78–452] |

| Symptoms: | |

| Neck and/or limb muscle weakness | 51 (82%) |

| Fatigable/fluctuating muscle weakness | 1 (2%)a |

| Myalgia | 36 (58%) |

| Oculomotor dysfunction | 31 (50%) |

| Diplopia without ptosis | 8 (13%) |

| Ptosis without diplopia | 9 (15%) |

| Diplopia and ptosis | 14 (23%) |

| Disorders of speech | 18 (29%) |

| Dysphagia | 26 (42%) |

| Requiring gastrostomy | 9 (15%) |

| Dyspnea | 33 (53%) |

| Requiring non-invasive ventilation | 18 (29%) |

| Requiring invasive ventilation | 7 (11%) |

| Concurrent myocarditis | 42/49 (86%) |

| Intensive care admission | 44 (71%) |

| Death | 25 (40%) |

| Ancillary investigations | No. (%) or median [IQR] |

|---|---|

| Serology: | |

| Antinuclear antibodies | 24/58 (41%) |

| Myositis-associated or -specific antibodies | 7/58 (12%) |

| MuSK Abs at diagnosis | 0/50 (0%) |

| AChR Abs at diagnosis | 14/53 (26%) |

| Positive prior to ICI exposure | 8/9 (89%) |

| Biochemistry: | |

| Peak creatine kinase (norm <170 U/L (males)/<140 U/L (females)) | 2800 [1300–6946] |

| Radiology: | |

| MRI: Muscle T2 hyperintensity | 12/16 (75%) |

| Electrodiagnostic studies: | |

| Myopathic pattern on EMG | 33/56 (59%) |

| Decrement on RNS | 1/41 (2%)a |

| Muscle pathology: | |

| Inflammation on peripheral muscle biopsy | 55/55 (100%) |

| Inflammation on muscle necropsy | |

| Diaphragm | 5/5 (100%) |

| Extraocular muscles | 1/1 (100%) |

Patient with pre-existing MG.

Median age was 70 [60–76] years, and 60% (n = 37/62) were male. Six percent (n = 4/62) of patients reported history of autoimmune disease (Hashimoto disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, MG, and anti-SRP-antibody-positive immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy). Skin cancer (32%; n = 20/62) including melanoma (24%; n = 15/62) and squamous cell carcinoma (8%; n = 5/62), and pulmonary cancer (27%; n = 17/62), were the most frequent indications for ICI therapy. Other indications were kidney cancer (10%; n = 6/62), liver cancer (6%; n = 4/62), thymoma (5%; n = 3/62), thymic epidermoid, oropharyngeal, colon, and bladder cancer (3%; n = 2/62, each), and ureter, cervical, breast, and Merkel cell cancer (2%; n = 1/62, each). Cancer was metastatic in 63% (n = 39/62) of patients. In a quarter (23%; n = 14/62) of cases, ICI treatment was given as first-line therapy. Patients received anti-PD1 (68%; n = 42/62) or anti-PDL1 (10%; n = 6/62) monotherapy in 77% (n = 48/62) of cases. The remaining patients (23%; n = 14/62) received combination therapy, targeting PD1 and CTLA4 (21%; n = 13/62), or PD1 and LAG3 (2%; n = 1/62). Median time from ICI exposure to symptom onset was 27 [18–43] days. Most patients exhibited neck and/or (predominantly proximal) limb muscle weakness (82%; n = 51/62), with a fatigable/fluctuating component only in the patient with pre-existing MG (2%; n = 1/62). Myalgia was frequently present (58%; n = 36/62). In addition, half of patients displayed oculomotor dysfunction, manifesting as isolated ptosis (15%; n = 9/62), isolated diplopia (13%; n = 8/62), or both ptosis and diplopia (23%; n = 14/62). Ptosis was asymmetric in approximately half of cases. Bulbar dysfunction included disorders of speech (29%; n = 18/62) and dysphagia (42%; n = 26/62), resulting in gastrostomy in 15% (n = 9/62) of patients. Dyspnea was observed in over half (53%; n = 33/62) of patients. In 29% (n = 18/62) and 11% (n = 7/62) of cases, respiratory failure required non-invasive and invasive ventilation, respectively. For patients with available cardiac workup (79%; n = 49/62), concurrent ‘definite’, ‘probable’ and ‘possible’ myocarditis were observed in 86% (n = 42/49), 4% (n = 2/49) and 10% (n = 5/49) of cases, respectively.22 Intensive care unit admission was required in 71% (n = 44/62) of cases. At a median follow-up of 315 [78–452] days, mortality was 40%. Death was due to cardiac arrest (8%; n = 5/62), respiratory insufficiency directly related to myotoxicity (6%; n = 4/62) or associated with pulmonary infection (11%; n = 7/62), and cancer (15%; n = 9/62). A Kaplan–Meier survival curve is provided in Supplementary Fig. S1.

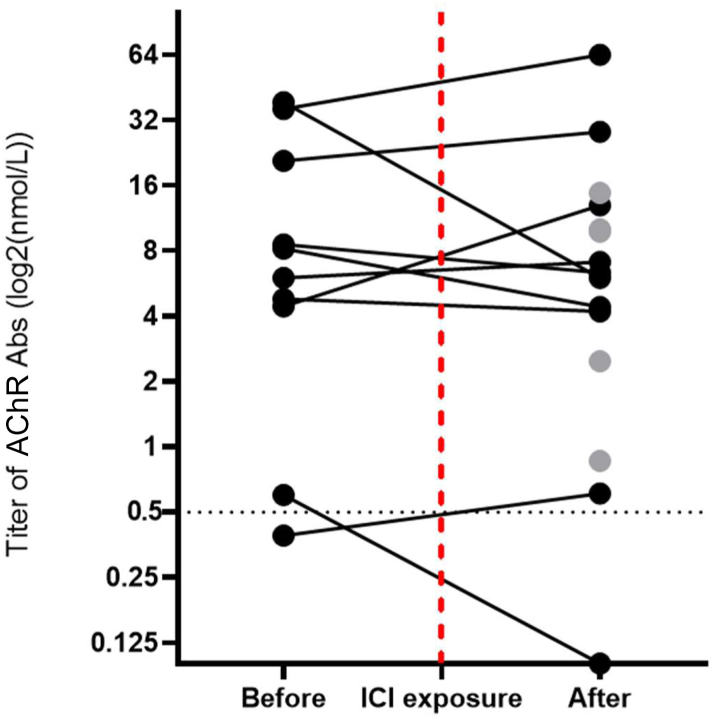

Antinuclear antibodies were present in 41% (n = 24/58) of patients. One-tenth of patients exhibited myositis-associated antibodies (directed against Ro60/SSA (7%; n = 4/58), PM-Scl (2%; n = 1/58), and U1-RNP (2%; n = 1/58)). Myositis-specific antibodies were observed only in one patient with pre-existing anti-SRP myopathy. This patient developed novel muscle weakness after ICI exposure and showed typical ir-myositis myopathology on muscle biopsy. Anti-MuSK Abs testing yielded negative results in all patients tested (0%; n = 0/50). At time of diagnosis, AChR Abs were present at a level of >0·5 nmol/L in 14 patients (26%; n = 14/53). In nine out of these 14 patients, we were able to additionally examine serum samples obtained prior to ICI exposure. We retrieved positive test results (>0·5 nmol/L) in eight out of nine patients, and a borderline negative test result (0·39 nmol/L) in the remaining patient. Furthermore, in one additional patient with no detectable AChR Abs at diagnosis, a positive test result could be noted prior to ICI exposure. An overview of pre- and post-ICI AChR Abs titers is provided in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S2. Among the eight patients with positive test results before and after ICI exposure, AChR Abs titer decreased following treatment in half the cases and increased in the other half (n = 4/8). Median AChR Abs titer (only including titers >0·5 nmol/L) was 8·6 [5·4–28·4] nmol/L (n = 9) before and 6·7 [IQR 4·2–13·0] nmol/L (n = 14) after ICI exposure. Of note, all patients with detectable AChR Abs (before or after ICI exposure) were treated with corticosteroids following ir-myositis diagnosis.

Fig. 2.

AChR Abs titer evolution pre-/post-ICI exposure. Spaghetti plot of AChR Abs titer (log2 scale, nmol/L) dynamics in patients with ir-myositis ± MG, showing evolution between last available AChR Abs titer before and first available AChR Abs titer after ICI exposure (black, n = 10) or, in patients without available pre-ICI AChR Abs testing, solely showing first available AChR Abs titer after ICI exposure (grey, n = 5). The dotted vertical red line indicates time of ICI exposure. The dotted horizontal black line denotes the threshold titer at which an AChR Abs test result was considered positive (0·5 nmol/L).

In our control group of idiopathic, adult MG patients (n = 438), with a median age of 44 [32–62] years and a female majority (66%; n = 289/438), the percentage of patients with a positive AChR Abs test at diagnosis (71%; n = 309/438) was significantly higher than that found in ir-myositis patients (26%; n = 14/53) (p < 0.0001). Among AChR Abs-positive patients, median antibody titer (19·8 [IQR 5·5–92·2] nmol/L) was also significantly higher compared to that in ir-myositis (6·7 [IQR 4·2–13·0] nmol/L) (p < 0.05).

CK peak level was 2800 [1300–6946] U/L. Magnetic Resonance Imaging showed muscle T2 hyperintensity in 75% (n = 12/16) of patients. EMG was myopathic in 59% (n = 33/56) of cases.

A decrement was demonstrated only in the patient with pre-existing MG (2%; n = 1/41). Considering that sensitivity of RNS in MG is dependent on clinical presentation, we sub-characterized patients with negative RNS. Out of 40 patients, 38 (95%) presented with neck and/or limb muscle weakness (n = 36/40) and/or generalized myalgia (n = 24/40). Two out of 40 patients (5%) exhibited extraocular muscle weakness in absence of more generalized muscle weakness or myalgia.

A muscle biopsy was obtained in 89% (n = 55/62) of patients. Additionally, we performed necropsies of the diaphragm (n = 5/5) and extraocular muscles (n = 1/1) in five patients (8%; n = 5/62). Both muscle biopsies and necropsies demonstrated intense and diffuse inflammation. Endomysial inflammatory cell densities were of CD68+ (macrophage) and CD8+ T-cell predominance. Necrosis, MHC class I upregulation, and C5b-9 deposition (on necrotic and non-necrotic fibers) were near-universal features and most commonly showed a multifocal distribution. Typical histopathology of the oculomotor, neck/limb, and respiratory (diaphragm) muscles using H&E staining is shown in Fig. 3, along with the frequency of clinical symptoms associated with dysfunction of these muscle groups (i.e., diplopia and/or ptosis, neck/limb weakness, and respiratory insufficiency, respectively). Representative findings of CD68+ and CD8+ cells immunohistochemical staining in muscle tissue including the diaphragm are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 3.

Oculomotor, neck/limb, and respiratory muscles: frequency of clinical involvement (n = 62, left) and typical histopathology on biopsy and necropsy (right) in ir-myositis ± MG patients. Left: Frequency of clinically significant oculomotor (50%; n = 31/62), neck/limb (82%; n = 51/62), and respiratory (53%; n = 33/62) muscle involvement in our cohort of ir-myositis ± MG patients (n = 62). Details in Table 2. Right: Representative histopathological findings on biopsy and necropsy of oculomotor (a, lateral rectus muscle, H&E, 100× magnification), neck/limb (b, deltoid muscle, H&E, 100× magnification), and respiratory (c, diaphragm, H&E, 25× magnification) muscles, showing florid, multifocal inflammatory cell densities (of CD68+ and CD8+ predominance, immunohistochemistry shown in Fig. 4) and necrosis. Other universal features included MHC class I upregulation and C5b-9 deposition on necrotic and non-necrotic fibers (not shown here).

Fig. 4.

Typical myopathology on diaphragm necropsy in ir-myositis ± MG patients: CD68+ and CD8+ cells. Immunohistochemistry reveals that inflammatory infiltrates in ir-myositis ± MG are composed mainly of macrophages (a, diaphragm, CD68, 100× magnification) and CD8+ T-cells (b, diaphragm, CD8, 100× magnification).

Discussion

Based on our extensive database, with a total of 2,910,417 patients including 620 patients evaluated for suspected ICI-induced motor neuromuscular disorder, and summarizing the experience of a decade of ICI use in Parisian hospitals including tertiary centers for myositis/MG, we were not able to find any patient with signs suggesting ir-MG (i.e., presence of fatigable or fluctuating muscle weakness, decrement on RNS, or AChR Abs) in absence of ir-myositis. Ir-myositis was myopathologically proven in most patients, or indicated by severe rhabdomyolysis (CK > 8000 U/L) in two patients without available muscle biopsy or autopsy. Our results are in accordance with a recent retrospective cohort study including patients with neurological irAEs from 20 hospitals in Spain, that noted pathological diagnosis of myositis in all patients with ir-MG suspicion.24 Accordingly, in studies describing cases of ‘ir-MG’ based on “MG-like” oculobulbar and/or respiratory symptoms, and/or presence of AChR Abs, increased CK levels are noted in >90% of patients.18,25,26 Together, these data lead to suggest that patients with ir-MG suspicion frequently appear to have (isolated, or concurrent) ir-myositis. While recognizing that the retrospective design of our study (i.a., lack of routine diagnostic testing) and the diagnostic challenges inherently associated with MG preclude any conclusive inferences, our results suggest lower incidence of isolated ir-MG than has often been reported.

In addition, in our cohort of ir-myositis patients (n = 62), we found no clear clinical or electromyographic indication that motor neuromuscular symptoms are (partly) caused by neuromuscular junction disorder. Although further research is needed, our findings suggest that the reported high incidence of concurrent ir-MG in some studies could be overestimated. We observed ptosis and/or diplopia in 50%, disorders of speech in 29%, dysphagia in 42% (requiring gastrostomy in 15%), and dyspnea in 53% (requiring non-invasive ventilation in 29% and invasive ventilation in 11%) of cases. These results confirm previous reports of frequent oculomotor and bulbar involvement, and early, severe respiratory failure in ir-myositis.13,15,16 Although these symptoms are uncommon in most other types of myositis,27 and could prompt suspicion of concurrent ir-MG,18,25 we were not able to find any patient with fatigable or fluctuating muscle weakness, nor electromyographic evidence of neuromuscular junction pathology, with the exception of one patient with pre-existing MG. This patient developed (pathologically proven) myositis after ICI exposure. In alignment with this observation, previous studies that reported clinical fatigability or decremental response on RNS in patients with suspected (concurrent) ir-MG also included patients with known MG diagnosis prior to ICI exposure.25

At time of ir-myositis diagnosis, a quarter of patients were found to test positive for AChR Abs (26%; n = 14/53). Presence of AChR Abs in a subset of ir-myositis patients is consistent with findings in earlier studies.15,17, 18, 19, 20 In addition, we demonstrate that patients already exhibit AChR Abs before receiving ICI treatment and that antibody titer does not increase after treatment. Serum samples obtained prior to ICI exposure were examined for antibodies in nine out of 14 patients with AChR Abs at time of diagnosis, demonstrating positive test results (>0·5 nmol/L) in eight out of nine patients, and a borderline negative test result (0·39 nmol/L) in the remaining patient. We did not observe a trend towards increased AChR Abs titer in sera obtained at time of ir-myositis diagnosis compared to that in sera obtained prior to ICI exposure, although we cannot exclude that this observation may be influenced by treatment with corticosteroids. Of note, although oculobulbar symptoms might also raise suspicion of concurrent anti-MuSK Abs-positive MG, none of the patients in our cohort exhibited anti-MuSK antibodies.

Our findings call into question whether the role of AChR Abs in these patients is the same as in classic, idiopathic MG. AChR Abs positivity has previously been described in non-myasthenic, idiopathic autoimmune conditions.28 In one study investigating ICI-treated cancer patients, neuromuscular autoantibodies, including AChR Abs, were detected in 63% (n = 15/24) of patients that developed irAE, compared to 7% (n = 3/44) of ICI-treated patients without irAE.29 In another study, AChR Abs were more prevalent in patients with ir-myocarditis compared to ICI-treated patients without ir-myocarditis.30 Similarly, a recent clinical trial in ICI-treated thymoma patients showed an association between pre-existence of AChR Abs and development of ir-myositis.17 A recent in vitro study revealed that AChR Abs from two ir-myositis patients lacked the effector functions (antigenic modulation, complement fixation, and receptor blocking) exerted by AChR Abs from idiopathic MG patients.31 Additionally, in our study, AChR Abs titer was significantly lower in ir-myositis compared to idiopathic MG. Together, these observations show that the role of AChR Abs in the pathogenesis of ICI-induced myotoxicities, occurring shortly (27 [18–43] days) after ICI exposure, is yet to be elucidated. Pre-existence of anti-AChR autoantibodies in some patients suggests presence of underlying imbalance in immune tolerance that is further disrupted by ICI therapy. Although further research efforts are needed, AChR Abs could potentially serve as a biomarker to identify patients that are most at risk of developing ir-myotoxicities after ICI exposure. Furthermore, we propose that presence of AChR Abs might not be a valid diagnostic marker for (concurrent) ir-MG in absence of clear clinical or electromyographic evidence of neuromuscular transmission defect, as has also recently been suggested by others.32 Instead, presence of AChR Abs in combination with motor neuromuscular symptoms should trigger meticulous evaluation for ir-myositis and ir-myocarditis in addition to ir-MG, in order to consider specific therapy for ir-myotoxicities.22

“MG-like” oculobulbar and respiratory symptoms may occur as a result of a particular, ir-myositis-specific distribution of muscle weakness (i.e., predilection for oculobulbar and respiratory musculature), instead of AChR Abs-mediated neuromuscular junction impairment. Indeed, necropsy of the extraocular muscles as well as the diaphragm revealed florid inflammatory infiltrates in all cases. Accordingly, extraocular muscle inflammation has been observed on magnetic resonance imaging by others.15 We speculate that inflammation of the oculobulbar muscles and diaphragm could cause the oculomotor and respiratory symptoms that we frequently observe in ir-myositis.

To conclude, incidence of ir-MG might be lower than is often suggested. In patients receiving ICI treatment, the appearance of “MG-like” oculobulbar and respiratory symptoms and/or AChR Abs should not only lead to consideration of ir-MG diagnosis, but also prompt screening and monitoring for inflammatory muscle disease, including concurrent, lethal ir-myocarditis, as management of ir-MG and ir-myotoxicities may differ.

Several limitations of our study should be noted. RNS, although performed in most patients, was not routinely studied in patients without clinical suspicion of neuromuscular junction disorder. In addition, single fiber EMG was not assessed and response to edrophonium was investigated in only one patient (negative result). While remaining cognizant of these limitations, considering the large number of patients we analyzed, the high percentage of analyzed patients with generalized muscle weakness and/or myalgia (95%) and severe disease and the high sensitivity of RNS in these cases (80% in generalized MG,33 and more sensitive in patients with fulminant disease34), it is unlikely that we failed to find evidence of a neuromuscular junction disorder in a significant portion of our study cohort. In addition, while acknowledging the possibility of recruitment bias, the wide-ranging expertise of our university's tertiary referral centers within the neurological and oncological field including those specialized in MG, myositis, and immunotherapy-related neurotoxicities, ensures significant involvement of the recruiting centers in treating patients with both peripheral nervous system disorders and neuro-oncological diseases, mitigating the risk of sampling bias.

Contributors

LP, HC and YA designed and wrote the first draft of the report.

DP, TM, SL, AZ, FT, MT, CA, NW, NC, AR, SD, NW, MAA, RLP, FT, MADD, LC, BA, MCB, AP, TS, CM, MD and SE provided the study materials or patients for the study.

LP, HC, EM, MCB, JES, OB and YA performed data curation, analysis and interpretation.

Lastly, all authors critically reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

Deidentified patient data from this study can be made available to qualified investigators who provide a methodologically sound research proposal and sign a data access agreement. Please email yves.allenbach@aphp.fr for information.

Declaration of interests

None of the authors received financial support for the submitted work. CA reports one patent planned in the field of management of immune checkpoint inhibitors toxicities. BA reports a research grant from MSD Avenir, consulting fees from Novartis, Astellas, and Sanofi, personal honorarium from Sanofi, AstraZeneca, BMS, MSD and Astellas, and support for attending meetings and/or travel from Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, IPSEN Pharma and Takeda. MT reports a grant from Sanofi, consulting fees from Servier, Novocure and NH TherAguiX, personal honorarium from Servier, Novocure and ONO, and support for attending meetings and/or travel from Servier. MT participated on a Data Safety Monitoring or Advisory Board for Servier. MCB reports personal honorarium, and support for attending meetings and/or travel from Novartis. SE reports consulting fees from Bayer, Amgen and Ipsen, and personal honorarium from AstraZeneca, BMS, Philips, General Electric, and Eisai. FT reports non-personal consulting fees from MSD, Novartis, and GSK. JES reports personal consulting fees from AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS and Novartis, several patents planned, issued or pending in the field of management of immune checkpoint inhibitors toxicities. YA received research funding from Sanofi and Association Recherche contre le Cancer, consulting fees from BMS, personal honorarium from RE-IMAGINE Health Agency and CSL Behring SA, and support for attending meetings and/or travel from CSL Behring SA and Boehringer Ingelheim France. YA had several patents planned, issued or pending in the field of management of immune checkpoint inhibitors toxicities.

Acknowledgements

We thank the support (SIGNIT) from the ARC Foundation for Cancer Research for this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.101192.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Wing K., Onishi Y., Prieto-Martin P., et al. CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science. 2008;322(5899):271–275. doi: 10.1126/science.1160062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman G.J., Long A.J., Iwai Y., et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med. 2000;192(7):1027–1034. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waterhouse P., Penninger J.M., Timms E., et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in Ctla-4. Science. 1995;270(5238):985–988. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishimura H., Nose M., Hiai H., Minato N., Honjo T. Development of lupus-like autoimmune diseases by disruption of the PD-1 gene encoding an ITIM motif-carrying immunoreceptor. Immunity. 1999;11(2):141–151. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong H., Strome S.E., Salomao D.R., et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. 2002;8(8):793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pardoll D.M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geraud A., Gougis P., Vozy A., et al. Clinical pharmacology and interplay of immune checkpoint agents: a yin-yang balance. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2021;61:85–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-022820-093805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodi F.S., O'Day S.J., McDermott D.F., et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellmann M.D., Paz-Ares L., Bernabe Caro R., et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):2020–2031. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paz-Ares L., Dvorkin M., Chen Y., et al. Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10212):1929–1939. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haslam A., Gill J., Prasad V. Estimation of the percentage of US patients with cancer who are eligible for immune checkpoint inhibitor drugs. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marini A., Bernardini A., Gigli G.L., et al. Neurologic adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review. Neurology. 2021;96(16):754–766. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anquetil C., Salem J.E., Lebrun-Vignes B., et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myositis: expanding the spectrum of cardiac complications of the immunotherapy revolution. Circulation. 2018;138(7):743–745. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pathak R., Katel A., Massarelli E., Villaflor V.M., Sun V., Salgia R. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced myocarditis with myositis/myasthenia gravis overlap syndrome: a systematic review of cases. Oncologist. 2021;26(12):1052–1061. doi: 10.1002/onco.13931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shelly S., Triplett J.D., Pinto M.V., et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myopathy: a clinicoseropathologically distinct myopathy. Brain Commun. 2020;2(2) doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcaa181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Touat M., Maisonobe T., Knauss S., et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related myositis and myocarditis in patients with cancer. Neurology. 2018;91(10):e985–e994. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mammen A.L., Rajan A., Pak K., et al. Pre-existing antiacetylcholine receptor autoantibodies and B cell lymphopaenia are associated with the development of myositis in patients with thymoma treated with avelumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor targeting programmed death-ligand 1. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(1):150–152. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Safa H., Johnson D.H., Trinh V.A., et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor related myasthenia gravis: single center experience and systematic review of the literature. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):319. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0774-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinal-Fernandez I., Quintana A., Milisenda J.C., et al. Transcriptomic profiling reveals distinct subsets of immune checkpoint inhibitor induced myositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(6):829–836. doi: 10.1136/ard-2022-223792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aldrich J., Pundole X., Tummala S., et al. Inflammatory myositis in cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(5):866–874. doi: 10.1002/art.41604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diez-Porras L., Homedes C., Alberti M.A., Velez-Santamaria V., Casasnovas C. Intravenous immunoglobulins may prevent prednisone-exacerbation in myasthenia gravis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70539-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salem J.E., Bretagne M., Abbar B., et al. Abatacept/ruxolitinib and screening for concomitant respiratory muscle failure to mitigate fatality of immune-checkpoint inhibitor myocarditis. Cancer Discov. 2023;13(5):1100–1115. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-22-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lefeuvre C.M., Payet C.A., Fayet O.M., et al. Risk factors associated with myasthenia gravis in thymoma patients: the potential role of thymic germinal centers. J Autoimmun. 2020;106 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2019.102337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fonseca E., Cabrera-Maqueda J.M., Ruiz-Garcia R., et al. Neurological adverse events related to immune-checkpoint inhibitors in Spain: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(12):1150–1159. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao S., Zhou Y., Sun W., Li Z., Wang C. Clinical features, diagnosis, and management of pembrolizumab-induced myasthenia gravis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2023;211(2):85–92. doi: 10.1093/cei/uxac108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weaver J.M., Dodd K., Knight T., et al. Improved outcomes with early immunosuppression in patients with immune-checkpoint inhibitor induced myasthenia gravis, myocarditis and myositis: a case series. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(9):518. doi: 10.1007/s00520-023-07987-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mariampillai K., Granger B., Amelin D., et al. Development of a new classification system for idiopathic inflammatory myopathies based on clinical manifestations and myositis-specific autoantibodies. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(12):1528–1537. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun F., Tavella-Burka S., Li J., Li Y. Positive acetylcholine receptor antibody in nonmyasthenic patients. Muscle Nerve. 2022;65(5):508–512. doi: 10.1002/mus.27500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller-Jensen L., Knauss S., Ginesta Roque L., et al. Autoantibody profiles in patients with immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced neurological immune related adverse events. Front Immunol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1108116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fenioux C., Abbar B., Boussouar S., et al. Thymus alterations and susceptibility to immune checkpoint inhibitor myocarditis. Nat Med. 2023;29(12):3100–3110. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02591-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masi G., Pham M.C., Karatz T., et al. Clinicoserological insights into patients with immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced myasthenia gravis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2023;10(5):825–831. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guidon A.C., Burton L.B., Chwalisz B.K., et al. Consensus disease definitions for neurologic immune-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(7) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-002890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bou Ali H., Salort-Campana E., Grapperon A.M., et al. New strategy for improving the diagnostic sensitivity of repetitive nerve stimulation in myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2017;55(4):532–538. doi: 10.1002/mus.25374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oh S.J., Jeong D., Lee I., Alsharabati M. Repetitive nerve stimulation test in myasthenic crisis. Muscle Nerve. 2019;59(5):544–548. doi: 10.1002/mus.26390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.