Abstract

Recent regulatory limits on concentrations of cadmium (Cd), an element of concern for human health, have made Cd reduction a key issue in the global chocolate industry. Research into Cd minimization has investigated soil management, cacao genetic variation, and postharvest processing, but has overlooked the cacao-associated microbiome despite promising evidence in other crops that root-associated microorganisms could help reduce Cd uptake.

A novel approach combining both amplicon and metagenomic sequencing identified microbial bioindicators associated with leaf and stem Cd accumulation in sixteen field-grown genotypes of Theobroma cacao. Sequencing highlighted over 200 amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) whose relative abundance was related to cacao leaf and stem Cd content or concentration. The two highest-accumulating genotypes, PA 32 and TRD 94, showed enrichment of four ASVs belonging to the genus Haliangium, the family Gemmataceae, and the order Polyporales. ASVs whose relative abundance was most negatively associated with plant Cd were identified as Paenibacillus sp. (β = −2.21), Candidatus Koribacter (β = −2.17), and Candidatus Solibacter (β = −2.03) for prokaryotes, and Eurotiomycetes (β = −4.58) and two unidentified ASVs (β = −4.32, β = −3.43) for fungi. Only two ASVs were associated with both leaf and stem Cd, both belonging to the Ktedonobacterales. Of 5543 C d-associated gene families, 478 could be assigned to GO terms, including 68 genes related to binding and transport of divalent heavy metals. Screening for Cd-related bioindicators prior to planting or developing microbial bioamendments could complement existing strategies to minimize the presence of Cd in the global cacao supply.

Keywords: Bioamendment, Cadmium-tolerant bacteria, Cocoa, Heavy metal bioremediation, Microbiome

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Sixteen diverse cacao genotypes varied 30–50x in leaf and stem Cd content.

-

•

Variation in microbiome composition may have contributed to Cd accumulation.

-

•

Amplicon sequencing highlighted >200 ASVs that may alter plant Cd accumulation.

-

•

Metagenomics identified >5500 gene families that may affect soil Cd availability.

-

•

These bioindicators could be used in soil screening or bioamendment development.

1. Introduction

Cd is a naturally occurring metal ion that is a concern in agriculture due to its detrimental impacts on human health. Cd damages the lungs, kidneys, liver, reproductive organs, and bones and is a known carcinogen [1]. Therefore, maximum allowable concentrations of Cd in cocoa powder and chocolate products were established by the European Commission in 2019, which garnered increased attention for the reduction of Cd throughout the global chocolate industry.

Reducing the Cd content of cacao beans requires an understanding of its movement through the soil-plant system and potential points for intervention [2,3]. Cd levels in agricultural soils are determined by natural factors, such as weathering of geological parent material, and anthropogenic impacts, such as fertilization with rock phosphates, manure, or sewage sludge, atmospheric deposition of pollutants, and nearby manufacturing [4,5]. The mobility of Cd in soil is generally low except under acidic conditions, where Cd-containing compounds are dissolved and Cd2+ is released into soil solution, becoming available for plant uptake [6]. The presence of complementary ions or soils with low redox potentials can result in reduced mobility and plant availability through the precipitation and sorption of Cd2+ [7]. These theoretical justifications of the importance of pH and adsorption sites in soil are supported by an evaluation of soil physicochemical parameters related to bean Cd content across cacao-growing regions [8]. Soil pH was one of the strongest predictors of bean Cd accumulation (in addition to total soil Cd and leaf Cd), and soil organic carbon moderated the effects of high soil Cd. Other soil physicochemical parameters and metal ions can also affect Cd uptake by cacao [9].

Currently, soil management strategies, such as the application of lime, biochar, and zeolites, are the main techniques used to mitigate Cd in cacao. Lime is frequently applied to Cd-containing soils to increase pH and reduce Cd availability to the plant; however, liming of surface soils does not prevent root uptake of Cd throughout the soil profile [10]. The effectiveness of the applications of biochar and lime is greatest when these compounds are incorporated into the root zone [11]. The application of lime via this method was greater than that of biochar for the mitigation of Cd in cocoa. Additionally, applying charcoal with lime may increase this effectiveness [12].

However, soil management practices are only a partial solution: in one field study, biochar application reduced the plant-available Cd for six months but liming, even at twice the recommended rate, was only effective for three months [13].

A second strategy involves capitalizing on cacao genetic variation in Cd uptake and allocation to breed cultivars with reduced uptake from the soil or translocation to beans. The effects of cacao genotype on uptake and partitioning between vegetative tissues and beans are well documented [[14], [15], [16]]. The uptake and translocation of Cd in plants have a genetically regulated component. This has been best characterized in rice [17]; however, the ability to detect these effects may depend on the environment, genetic diversity, and timing of the study [18]. Grafting commercially desirable scions to low-Cd rootstock may further aid in Cd mitigation [19,20].

The soil microbial community offers untapped potential for novel Cd mitigation strategies to complement soil management and rootstock breeding. Certain soil bacteria and fungi inhibit plant Cd uptake via mechanisms including alteration of redox conditions, binding of Cd to the microbial cell wall surface, synthesis of organic compounds that sequester Cd, and the production of compounds that form insoluble precipitates [6,21]. In addition, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are thought to reduce plant uptake by sequestering Cd from the soil in the extraradical mycelium [22]. Despite these well-described mechanisms, and numerous Cd studies in a variety of plant species (Table S1), research on cacao-specific Cd-tolerant microorganisms is limited [[23], [24], [25]].

Most research on Cd-tolerant microorganisms for cacao to date has been conducted on individual microorganisms in vitro or with inoculation studies. This research, primarily centered in Ecuador and Colombia, has identified multiple native strains of Cd-tolerant bacteria and begun to measure impacts on cacao Cd levels [[24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30]]. Microcalorimetry has been used to measure Cd metabolism and solution culture studies have been used to characterize potential tolerance mechanisms or measure changes in Cd availability [21,23,24,27]. Recently, a small number of field-scale survey studies have started to investigate the relationships between microbial communities as a whole and Cd accumulation in cacao [25,31,32]. Studies integrating plant and microbial aspects of Cd uptake are lacking, however.

To accelerate the development of microbial strategies for Cd mitigation in cacao, amplicon and metagenomic sequencing were used to compare soil prokaryotic and fungal communities associated with sixteen high- and low-Cd-accumulating cacao cultivars in Trinidad. The aim of this study was to identify cacao genotypes and microbial taxa and genes that are associated with reduced leaf and stem Cd content. We hypothesized that a) high-accumulating genotypes would be enriched in specific taxa relative to low-accumulating genotypes, and b) taxa and genes with genotype-independent strong and significant associations with plant Cd could be identified. Screening for these bioindicators or using them to develop bioamendments could complement soil management and breeding mitigation efforts, helping to meet the increasing global demand for cacao while minimizing the negative impacts of Cd on human health.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Site and germplasm description

T. cacao trees sampled in this study were grown at the International Cocoa Genebank, Trinidad (ICGT) in Centeno, Trinidad (10°35′N, 61°20′W) – the largest and most diverse public cacao germplasm collection in the world. The ICGT, a 34-ha site, is located on acidic soils (pH 4.94) classified as Aquic Eutropepts and receives approx. 2000 mm of precipitation annually [15].

Currently, the ICGT contains approximately 2400 genotypes of T. cacao that were mainly propagated as rooted cuttings; these trees are approximately 30 years old. Sixteen of these genotypes representing different genetic backgrounds, including five known genetic groups as well as the hybrid Refractario [33], were assessed in this study (Table 1). Seven genotypes were identified as low Cd accumulators in a previous field study, whereas the remaining nine were identified as high Cd accumulators [15]. Three field-grown trees were sampled per genotype (n = 48).

Table 1.

Cacao accessions sampled for cadmium uptake. Classifications of Cd accumulation were based on field studies in Lewis et al. (2018).

| Genotype | Genetic Group | Propagation Method | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| GS 10 | Amelonado | Rooted cutting | Low accumulator |

| SLC 18 | Amelonado | Rooted cutting | Low accumulator |

| GU 255/P | Guiana | Rooted cutting | High accumulator |

| GU 351/P | Guiana | Grafted | High accumulator |

| IMC 103 | Iquitos | Rooted cutting | Low accumulator |

| IMC 14 | Iquitos | Rooted cutting | Low accumulator |

| IMC 33 | Iquitos | Rooted cutting | Low accumulator |

| IMC 58 | Iquitos | Rooted cutting | Low accumulator |

| LCT EEN 368 | Purus | Grafted | High accumulator |

| PA 32 | Marañon | Rooted cutting | High accumulator |

| NA 154 | Nanay | Rooted cutting | High accumulator |

| TRD 94 | Nanay | Rooted cutting | High accumulator |

| CLM 35 | Refractario | Grafted | High accumulator |

| SLC 8 | Refractario | Rooted cutting | High accumulator |

| LX 44 | Refractario | Rooted cutting | Low accumulator |

| POUND 31/C | Unknown | Rooted cutting | High accumulator |

2.2. Sample collection

Because impacts of the soil microbiome on Cd accumulation occur over relatively time horizons, soil samples were collected for sequencing a few months prior to measuring leaf and stem Cd levels. Soil samples were collected from around three trees per accession in the month of March 2021. Composited soil samples were collected at four points around the drip zone of each tree using a stainless-steel auger (diameter = 3 cm) at a depth of 0–20 cm. Collected soil samples were stored in a polystyrene foam cooler containing dry ice during field collection. These samples were then placed in a −20 °C freezer until sample analysis. After collection, samples were packaged in a polystyrene foam cooler and shipped on dry ice to the lab where they were processed for microbial and Cd analysis.

Leaf and stem samples were collected at the late interflush-2 stage of development during the month of October 2021. These samples were collected from each of the trees where soil samples were collected, excluding the accessions IMC 14, IMC 103, and SLC 8. For these accessions, only two of the three trees were sampled due to the third suffering extensive physical damage or high disease prevalence. Cacao leaves and stems develop concomitantly during flushing, so a combination of physiological parameters was used to identify flushes at the late interflush-2 stage. These are 1) leaf color was the deep green color found at maturity; 2) stem was mature; and 3) Early stages of phellem development on the side of the stem associated with the adaxial side of the leaf. These characteristics describe a fully developed and mature flush [34,35]. From each tree, between 5 and 10 flushes at the late interflush-2 stage of development were collected from different points in the canopy. Collected leaf and stem samples were separated, then cleaned of surface contaminants using 1.2 % NaOCl, then using distilled and deionized water. Cleaned samples were placed in paper bags and dried in an oven at 70 °C until no further loss in mass was observed.

2.3. Soil and plant Cd analysis

Dried plant samples were ground and sifted through a 40-mesh sieve, whereas soil samples were air-dried, ground, and sifted through a 60-mesh sieve. Cd concentrations in leaves, stems, and soil were measured using a nitric acid/hydrogen peroxide closed vessel microwave digestion system followed by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) at the UC Davis Analytical Laboratory, Davis, CA, USA [36]. The analysis had a Cd detection limit of 0.1 mg kg−1.

2.4. Microbial analysis

DNA was extracted from 0.75 g soil in three technical replicates per tree using DNeasy PowerSoil Pro kits (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD, USA). Lysis was performed using a PreCellys Evolution (Bertin Instruments, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France) with a first step of 3 15s at 5000 rpm followed by 2 30s at 6800 rpm. The original 515F/806R primer pair [37] was used to amplify the V4 region of 16S rRNA for prokaryotes, and the ITS1F/ITS2 primer pair was used to amplify the ITS1 region for fungi [38,39]. Metagenomic sequencing was conducted by Novogene, Inc. in accordance with their standard methods. Briefly, genomic DNA underwent fragmentation, end repair, A-tailing, and ligation to Illumina adapters, followed by PCR amplification, selection of fragments of the correct size, and purification. Libraries were pooled and sequenced at a depth of 12 GB.

2.5. Data analysis

Downstream analyses of sequencing data as well as all statistical analyses were conducted using R v.4.1.3 [40]. The dada2 pipeline was used for sequence denoising, quality filtering (parameters: maxN = 0, maxEE = c(2,2), truncQ = 2), removal of 16S sequences outside the expected length of 250–256 bp, and generation of amplicon sequence variant (ASV) tables [41]. The phyloseq package was used to remove chloroplast and mitochondria sequences [42].

Constrained analysis of principal coordinates (CAP) was used to ordinate prokaryotic and fungal communities separately. ASV tables were transformed to relative abundance using the microbiome package v.1.16.0 [43] and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrices were ordinated with genotype as a fixed factor using the vegan package v.2.5.7 [44]. Significant genotype effects were tested with permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) with 5000 permutations.

The emmeans package v.1.7.2 [45] was used to compare Cd concentrations by calculating estimated marginal means and standard errors for each genotype and tissue type. Post hoc tests were based on α = 0.05 with the Šidák correction to adjust for multiple comparisons.

Positive and negative relationships between microbial ASVs and leaf or stem cadmium concentrations were tested with linear models as implemented in the MaAsLin2 package v.1.8.0 [46]. This approach was developed to detect statistically significant associations between multi-omics data and complex metadata. ASVs were required to be present in a minimum of 10 % of samples to be included in the analysis. Generalized linear models were run twice each for ASV tables of prokaryotes and fungi subjected to compositional transformation, first using leaf and stem Cd contents as fixed effects and then using concentration data. These models yield coefficients (β) and significance statistics (q, p) for each ASV, with positive coefficients representing positive relationships between relative abundance of that ASV in the microbiome and plant Cd, and negative coefficients representing the inverse. Associations were considered significant for this study with a Bonferroni-Holm-corrected q < 0.25 and p < 0.05.

Metagenomics reads from individual trees were trimmed and mapped to multiple databases using the HUMAnN v4 standard workflow pipeline [47]. Briefly, trimmed WGS reads from soil samples were aligned to a taxonomic database and unmapped reads were assembled for further alignment to a database of functional annotations. Remaining unmapped and unaligned reads, where possible, were aligned to UniRef50 to assign functional classification based on cluster ID, even if organism-agnostic. It is worth noting that despite these efforts, the majority of reads from each sample remained unmapped and unclassified, but enough were classifiable to enable per-sample comparison between gene family abundances, pathway abundance, and pathway coverage. To assess functional differences between soil communities of high versus low Cd accumulating trees, significantly represented gene family abundances (represented as reads per kilobase) were further analyzed with generalized linear models using leaf and stem Cd concentrations as fixed effects in MaAsLin2. The minimum prevalence threshold was set at 10 % and the maximum significance (q) was set at 0.25 for this analysis with other parameters set at their default values, including of total sum of squares normalization and significance adjustment with the Bonferroni-Holm method.

Significant UniRef50 cluster IDs were assigned GO terms using the UniProtKB database, hosted by EMBL-EBI [48]. This metagenomics component of the study required high sequence coverage, on average 150.5M reads per sample, before significant representation of gene families and metabolic pathways could be identified. Despite this high coverage, an average of 50 % of reads remained unmapped, presumably due to limited database entries for microorganisms from tropical soils. To address this, the metagenomics sequence set was also screened against 709 microbial nucleotide sequences that are known to be related to Cd processing. These genes were pulled from a review of Cd-related literature and compiled into a custom fasta file. Metagenomics sequences were aligned to these 709 genes using BWA [49], and the resulting aligned files were processed to count read coverage per gene. These coverages were normalized and analyzed for significance in MaAsLin2, using leaf and stem Cd concentrations as fixed effects. Again, default parameters were used for these generalized linear models, with a minimum prevalence threshold of 10 % across samples, q < 0.25, total sum of squares normalization, and Bonferroni-Holm adjustment.

3. Results

3.1. Cacao genotypes differed in cadmium accumulation

The leaf and stem Cd content of the sixteen cacao genotypes assessed in this study exhibited a continuous distribution (Fig. 1). Leaf Cd ranged from 0.0023 to 0.0754 mg, and stem Cd content ranged from 0.00032 to 0.016 mg. PA 32, Pound 31/C, GU 255/P, TRD 94, and GU 351/P were the five highest-accumulating genotypes as measured by both leaf and stem Cd, and SLC 18, GS10, LX44, and IMC 103 were among the five lowest-accumulating genotypes in both cases. However, differences among genotypes were significant only for leaf Cd content (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Cadmium accumulation by genotype. Leaf Cd content ranged from 0.0023 to 0.0754 mg, and stem Cd content ranged from 0.00032 to 0.016 mg. Bars represent estimated marginal means for three trees per genotype (n = 48). Error bars represent standard error. Bars not labeled with the same letter are significantly different at α = 0.05.

The order of these genotypes differed when based on leaf and stem Cd concentration rather than content (Fig. S1). Leaf and stem concentrations ranged from 0.28 to 10.38 mg kg−1 and 0.67–14.86 mg kg−1, respectively. The ranking of genotypes was nearly identical for the two tissue types, with TRD 94 accumulating roughly twice as much Cd as any of the other genotypes and SLC 18 accumulating the least. Only TRD 94 was significantly different from all other genotypes at the α = 0.05 level.

3.2. Prokaryotic and fungal communities were affected by host genotype

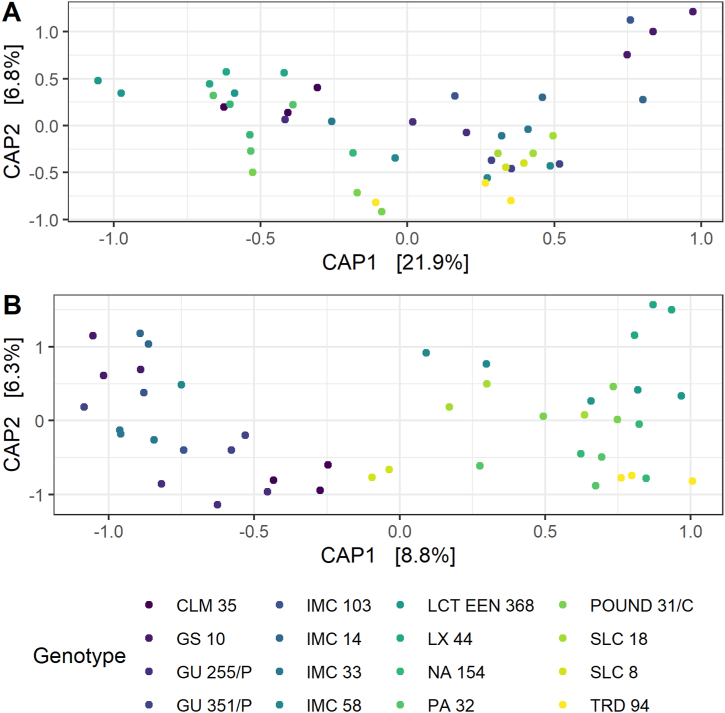

Root-associated microbial communities tended to cluster by cacao genotype, with microbiome samples obtained from trees of the same accession more similar to one another than to samples obtained from trees of other accessions (Fig. 2). PERMANOVA revealed that cacao genotype was a strong and significant driver of variation for prokaryotic (R2 = 0.60, p < 2e-04) and fungal communities (R2 = 0.50, p < 2e-04).

Fig. 2.

Constrained ordination of microbial communities associated with different cacao genotypes. Constrained analysis of principal coordinates (CAP) was used with cacao genotype as a fixed factor to ordinate microbial relative abundance data for A) prokaryotes and B) fungi. Dots represent microbial communities associated with a single tree and colors represent the sixteen cacao genotypes sampled.

3.3. Microbial ASVs were associated with variation in plant Cd uptake

Fifty-six unique prokaryotic ASVs were associated with leaf or stem Cd content (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). None of these ASVs had coefficients of the same sign for both leaf and stem Cd: 18 had negative leaf coefficients but positive stem coefficients, three had negative stem coefficients but positive leaf coefficients, and the remainder only had a coefficient for one plant tissue. The highest-magnitude negative coefficients were found for ASV1983B (Paenibacillus sp., β = −2.21), ASV722B (Candidatus Koribacter, β = −2.17), ASV2216B (Candidatus Solibacter, β = −2.03), and ASV4878B (family Chlamydiaceae, β = −1.71). The highest positive coefficients were found for ASV958B (family Nitrososphaeraceae, leaf β = 2.39), ASV900B (family Gemmataceae, leaf β = 2.60), ASV4878B (family Chlamydiaceae, stem β = 2.03), ASV739B (Streptomyces cyanogenus, leaf β = 2.02), and ASV984B (Citrifermentans sp., leaf β = 1.86). Two ASVs had notably higher relative abundance across samples than the other ASVs: a member of the family Xanthobacteraceae (leaf β = 0.72) and a member of the genus GOUTA6 (leaf β = −0.40). None of the ASVs had genotype-specific enrichment patterns.

Fig. 3.

Prokaryotic ASVs associated with leaf Cd content. General linear models identified 36 unique prokaryotic ASVs that were associated with leaf Cd content. Coefficients for the relationship between each ASV and leaf Cd are shown above the heatmap, with red indicating negative relative abundance-Cd associations and green indicating positive associations (q > 0.25, p > 0.05). Cell color represents the relative abundance of ASVs (heatmap columns) across samples (heatmap rows). ASVs are labeled with the lowest identifiable taxonomic rank and samples are labeled with the name of the accession followed by the tree ID (biological replicate). Leaf Cd concentrations for each sample are shown to the left of the heatmap.

Fig. 4.

Prokaryotic ASVs associated with stem Cd content. General linear models identified 33 unique prokaryotic ASVs that were associated with stem Cd content. Coefficients for the relationship between each ASV and stem Cd are shown above the heatmap, with red indicating negative relative abundance-Cd associations and green indicating positive associations (q > 0.25, p > 0.05). Cell color represents the relative abundance of ASVs (heatmap columns) across samples (heatmap rows). ASVs are labeled with the lowest identifiable taxonomic rank and samples are labeled with the name of the accession followed by the tree ID (biological replicate). Stem Cd concentrations for each sample are shown to the left of the heatmap.

128 unique fungal ASVs were associated with leaf or stem Cd content, 109 of which had at least one positive coefficient and 83 of which had at least one negative coefficient (Table S2). The majority of these belonged to the phylum Ascomycota (88), followed by the Basidiomycota (20). Only three genera were represented by three or more ASVs: Geastrum sp. (4), Fusarium sp. (3), and Trichoderma sp. (3). The highest-magnitude negative coefficients were found for ASV56F (class Eurotiomycetes, leaf β = −4.58), ASV42F (unidentified, leaf β = −4.32), ASV216F (unidentified, leaf β = −3.43), ASV1036 (Entoloma sp., leaf β = −2.98), and ASV406 (Fusarium sp., leaf β = −2.72). The highest positive coefficients were found for ASV42 (unidentified, stem β = 4.12), ASV56F (class Eurotiomycetes, stem β = 3.87), ASV92F (Paracremonium sp., stem β = 2.74), ASV280F (Ascobolus sp., leaf β = 2.71), and ASV1336F (Talaromyces sp., stem β = 2.69).

In light of differences in plant Cd accumulation based on Cd content as compared to concentration, the analysis was re-run using concentration data. Seventeen prokaryotic ASVs were found to be associated with leaf or stem Cd concentrations (Fig. S2), of which only two were also associated with Cd content. Both of those consensus taxa were members of the Ktedonobacterales. Of the prokaryotic ASVs, two (a member of the Gemmatimonadaceae family and a member of the Ktedonobacteraceae family, genus 1921–2) were negatively associated with stem Cd but positively associated with leaf Cd (Fig. S2). All other Cd-associated ASVs were positively associated with either leaf or stem Cd. A heatmap of relative abundance of Cd-associated ASVs across samples highlighted genotype-specific enrichment patterns (e.g. ASV 2628 and ASV 3699 in PA 32, Fig. S2).

Two fungal Cd-concentration-associated ASVs were identified, both members of the Polyporales, and both were positively associated with leaf Cd (ASV 577: β = 1.90, p < 4.02e-07; ASV 304: β = 2.07, p < 8.16e-07). Both ASVs were highly enriched in TRD 94 and PA 32 relative to other genotypes (Fig. S3).

3.4. Metagenomic analysis showed gene families and GO terms associated with Cd

5543 gene families and four pathway abundances were significantly associated with leaf or stem Cd content. Of those gene families, 2719 (49 %) were unclassified, meaning that they could not be matched with entries in the UniRef50 database. 1874 (34 %) gene families were associated with leaf Cd and 3669 (67 %) were associated with stem Cd, with 465 (8 %) associated with both leaf and stem Cd. More gene families were positively associated with plant Cd (1091 positively associated with leaf Cd, 3002 with stem Cd) than negatively associated (783 with leaf Cd, 667 with stem Cd).

Gene families were mapped to GO terms to investigate their molecular functions, yielding 314 GO terms that were positively associated with leaf or stem Cd and 164 that were negatively associated (Fig. 5). Many of these GO terms had putative functions related to divalent metal cation binding and transport. The strongest positive association was identified for GO:0005384, described as related to manganese ion transmembrane transport activity (β = 2.57, p = 4.97e-05), and other strong positive associations were identified for GO:0005506 (iron ion binding, β = 2.49, p = 2.06e-05), GO:0000287 (magnesium ion binding, β = 1.59, p = 1.71e-04), and GO:0030145 (manganese ion binding, β = 1.59, p = 1.71e-04) (Fig. 4A). Strong negative associations with leaf and stem Cd were found for GO:0046872 (metal ion binding, β = 1.59, p = 1.38e-04), GO:0005506 (iron ion binding, β = 1.46, p = 1.23e-04), and GO:0016151 (nickel cation binding, β = 1.46, p = 1.23e-04) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 5.

Molecular functions related to divalent metal cation binding or transport of GO terms with positive (A) and negative (B) associations with plant Cd content. Microbiome-specific linear models of leaf and stem Cd content were used to identify UniRef50 gene families with significant coefficients (q < 0.25, p < 0.05), and GO terms were assigned to significant UniRef50 gene families using the UniProtKB database. The sign of the coefficient represents the direction of the association between relative abundance of that term and plant Cd content, the absolute value of the coefficient indicates the magnitude of the association, and the p value can be used to determine its significance.

Other GO terms with large positive or negative coefficients were not clearly related to metal ion binding or transport. The largest negative association with leaf Cd was identified as GO:0004733, with a putative function of pyridoxamine phosphate oxidase activity (β = 2.34, p = 9.33e-05), followed by GO:0008705 (methionine synthase activity, β = 2.26, p = 8.59e-05) and GO:0003677 (DNA binding, β = 2.23, p = 1.64e-04). Strong positive associations were observed for GO:0008168 (methyltransferase activity, β = 2.46, p = 6.54e-06), GO:0003924 (GTPase activity, β = 2.31, p = 1.40e-04), and GO:0008047 (enzyme activator activity, β = 2.29, p = 3.57e-05).

Finally, we searched this dataset for a set of 709 microbial Cd-related genes identified from the NCBI Gene database and tested them for significant associations with leaf or stem Cd. NZ_UIGE01000001.1, a cadC protein from Brevundimonas diminuta, was positively associated with leaf Cd (β = 0.43, p = 1.66e-04) and negatively associated with stem Cd (β = −0.39, p = 7.33e-04).

4. Discussion

The finding of differences in leaf and stem Cd among these genotypes is consistent with other studies showing substantial genetic variation in cacao for Cd uptake and partitioning [19,20,50,51]. Based on leaf Cd content data and Lewis et al. [15], SLC 18, GS 10, LX 44, and IMC 103 could be recommended as low-accumulating cacao genotypes for cultivation in high-Cd soils.

Soil data from a previously published study indicates that these differences were indeed due to genetic factors and not to heterogeneous soil Cd [15]. The continuous distribution of leaf Cd content observed here suggests multiple genes are involved in the control of Cd uptake and translocation. Leaf Cd content of “low accumulators” SLC 18, GS 10, LX 44, IMC 14, IMC 103, and IMC 58 was low but not significantly lower than that of “high accumulators” LCT EEN 368 or SLC 8 (Fig. 1A). This result underscores the fact that categorical classifications of “high-Cd” and “low-Cd” clones based on a single type of data could be misleading, as such classifications may not be consistent for Cd content vs. concentration, between plant organs, across soil environments, or over time. Rankings based on both leaf Cd concentration and content are likely more reliable because these variables incorporate the mass effect in an opposing manner. Clone recommendations for Cd mitigation should ideally be validated locally and with large sample sizes, though this may not always be feasible, and it is important to report the plant organ in which Cd was measured. Large multi-location trials over multiple growing seasons could also help identify clones suitable for Cd mitigation across environments.

Though describing the mechanisms responsible for differences in Cd among cultivars was out of scope for this experiment, understanding those mechanisms would be useful for breeding programs. Many pathways could lead to differences in Cd accumulation, and these have been extensively reviewed elsewhere [52]. For example, research in amaranth shows that genetic variation in root exudation of organic acids can be responsible for cultivar differences [53], as low pH in the rhizosphere can contribute to soil Cd mobilization and enhanced uptake.

One objective of this study was to identify ASVs that could be responsible for cultivar differences in Cd uptake by seeking out genotype-specific enrichment patterns on relative abundance heatmaps of Cd-associated taxa. We identified four prokaryotic and fungal ASVs that were positively associated with plant Cd concentration or content, i.e. higher relative abundance of those ASVs was associated with increased plant Cd, and were enriched in high-accumulating genotypes. These ASVs were identified as belonging to the genus Haliangium, the family Gemmataceae, and the order Polyporales, and were enriched in the two highest-accumulating genotypes, PA 32 and TRD 94 (Figs. S2 and S3). The combination of positive association with Cd and overrepresentation in high-accumulating genotypes suggests a possible influence of these taxa on Cd availability that should be investigated further, as validation of potential mechanisms is beyond the scope of this study. The genus Haliangium has been noted elsewhere to be found at higher relative abundance in higher-Cd than lower-Cd soils [54], for example, which is the pattern observed for Cd-tolerant bacteria [21]. In light of substantial variation in relative abundance between biological replicates of these genotypes, however, future studies would benefit from employing larger sample sizes.

None of the ASVs we identified with negative coefficients showed genotype-specific enrichment patterns, but ASVs not recruited by specific cacao genotypes may be even more useful as potential soil bioamendments for Cd mitigation. Some ASVs identified here with large negative coefficients for leaf Cd, such as Paenibacillus sp. and Fusarium sp., belong to genera known to contain species with proven Cd biosorption capabilities [55,56]. Others, including members of the genus Candidatus Solibacter and the class Eurotiomycetes, belong to genera whose relative abundance has been found to be correlated with soil Cd [57,58], perhaps suggesting tolerance mechanisms that could be exploited to reduce cacao uptake. Even ASVs with negative coefficients for stem Cd and positive coefficients for leaf Cd, such as two members of the Ktedonobacterales (Fig. S2), could potentially be used for this purpose in light of evidence supporting preferential Cd translocation from branches to nibs rather than from leaves to nibs [59]. The Ktedonobacterales appear particularly important given that they were the only taxa identified by both Cd content and concentration data, as well as associated with both stem and leaf Cd, but this order is not well characterized in Cd inoculation studies (Table S1) nor in the thorough review of cadmium-tolerant bacteria by Bravo and Braissant [21]. This order of Gram-positive bacteria with morphological similarities to the actinomycetes belongs to the phylum Chloroflexi and is found in diverse soils, though little is known about its ecology [60]. More research is needed to understand the potential mechanisms for cadmium mitigation by this taxonomic group. Not all cadmium-tolerant bacteria would contribute to decreased plant uptake, so understanding the mechanisms contributing to resistance is critical. A primary trait conferring Cd tolerance is the presence of efflux transporters, which allow bacteria to remove Cd from their own cells but would not alter plant availability [61]. Other mechanisms, however, such as chemisorption to the cell wall via the presence of functional groups that bind Cd or enzymes that alter its bioavailability, could be highly useful in reducing plant uptake [21,61]. In addition, future research should build on the present study by investigating the effect of community-level properties and rhizosphere ecological interactions on plant Cd uptake.

Numerous genes with large positive or negative coefficients had putative functions related to binding or transport of divalent metal cations (Fig. 5), which could be involved in microbial mechanisms of Cd tolerance and sequestration [21]. More of the GO terms with functions related to metal ion binding and transport had positive coefficients than negative coefficients, but the terms with negative coefficients should be explored further for phylogenetic signals to identify additional Cd-tolerant microorganisms. In light of sparse coverage of prokaryotic genes related to metal metabolism in UniRef50 [62], we also searched this dataset for over 700 microbial Cd-related genes found in the NCBI database. Only one of these entries, a cadC gene, was identified as significantly associated with leaf and stem Cd here. cadC is a transcriptional regulator in the cad cadmium resistance operon, which contains a Cd efflux transporter, and has been identified in numerous Cd-tolerant bacteria [21,63]. Larger databases of prokaryotic genes in general, and particularly those related to metal transport and processing, will be required for metagenomics to be a more useful tool in identifying microbial solutions for amelioration or remediation of Cd or other metals.

Many of the GO terms that were strongly and significantly associated with reduced Cd uptake were not related to divalent metal cation binding or transport. Interestingly, a metagenomic study investigating genetic determinants of microbial Cd resistance found multiple open reading frames that were associated with Cd resistance despite the lack of an obvious direct mechanism [63]. Expressing one of these, a histidine kinase-like adenosine triphosphatase, in E. coli reduced Cd accumulation by 33 %, highlighting the fact that mechanisms of Cd resistance may not always be readily apparent, especially when attempting to interpret single pathway steps identified in metagenomic studies. Furthermore, focusing on gene families with defined functions is limiting: of the 5543 UniRef50 gene families significantly associated with leaf or stem Cd, only 478 were able to be assigned to GO terms. The unassigned gene families thus represent a wealth of untapped data, but characterizing these proteins, their functions, and their relationship to novel mechanisms of Cd mitigation was beyond the scope of this paper.

Rootstock genetics and the soil microbiome are two of many factors that may be included in multifaceted solutions to the problem of Cd accumulation in cacao. Soil physicochemical characteristics (including not only Cd concentration and speciation but also pH, soil organic matter, and micronutrient availability) and plant physiological traits also affect uptake and translocation [[5], [8], [64], [65], [66]], and could provide important complements to strategies derived from the results of this study. For example, soil chemical amendments to reduce Cd availability, targeted to soil type and applied using methods that maximize effectiveness [[10], [11], [67], [68], [69]], could be combined with microbial inoculants that sequester Cd [[21], [24], [55], [70]] and biotechnological approaches that leverage recent advances in understanding of Cd uptake, transport, and storage [[71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77]].

5. Conclusions

We showed that sixteen diverse genotypes of Theobroma cacao exhibit continuous variation in leaf and stem Cd concentration and content. Genotypes SLC 18, GS 10, LX 44, and IMC 103 accumulated the least Cd and PA 32 and TRD 94 accumulated the most. These results suggest that Cd accumulation is under polygenic control and present germplasm with contrasting phenotypes for this trait for potential use in breeding programs. Furthermore, we highlight microbial taxa and genes that may be partially responsible for the differentiation among these cacao genotypes in Cd accumulation as well as microbial biomarkers associated with Cd independently of plant genotype.

The findings of this study could become part of multiple solutions to Cd mitigation in cacao. First, the list of ASVs or genes positively or negatively associated with plant Cd could inform soil screenings of potential new planting sites as a complement to soil Cd testing. Given that the present study was conducted in a single region, these specific biomarkers would need to be validated in other geographic and climatic contexts before use. The presence of ASVs or genes with positive coefficients could indicate a higher than usual risk of Cd uptake at a given concentration of soil Cd, while the presence of ASVs or genes with negative coefficients might offer some level of protection. Second, selected microorganisms or genes could be further developed into bioamendments to be applied to high-Cd soils. ASVs with large negative coefficients for plant Cd and microorganisms possessing genes identified here as negatively associated with plant Cd could be promising candidates. The first steps would be to propagate these microorganisms and screen them in vitro and under controlled conditions to verify their ability to metabolize Cd and prevent it from being taken up by plants. Traits a strain must possess to be successfully developed into a biofertilizer, such as those that enable culturing under laboratory conditions and shelf stability, do not always coexist with target traits for plant growth promotion or other desirable agronomic outcomes. If those challenges can be resolved, however, a Cd-mitigating bioamendment could be a fast-acting, rhizosphere-targeted complement to other soil management strategies such as liming, zeolites, and biochar. Genes identified here could theoretically also be used to engineer novel strains with increased Cd sequestration activity, as previous studies have shown that engineering bacterial strains to enhance expression of metallothioneins or other proteins related to Cd mitigation can reduce plant uptake from soil. However, deployment of genetically engineered Cd-sequestering microorganisms in agricultural fields is unlikely to be feasible from a regulatory perspective nor accepted by consumers in the near future. In conclusion, the results of this study can be further developed into bioindicator screening methods or bioamendments to complement soil management, choice of germplasm, and postharvest processing as strategies to minimize Cd concentrations in the global cacao supply.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jennifer E. Schmidt: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Project administration, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Caleb A. Lewis: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Alana J. Firl: Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Pathmanathan Umaharan: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Conceptualization.

Data availability

The data used in this study has not been provided because it is confidential.

Funding

Plant and soil analysis for this study was supported by Mars Inc., which also employs AF and JS.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:Jennifer Schmidt reports financial support was provided by Mars Wrigley. Alana Firl reports financial support was provided by Mars Wrigley. Jennifer Schmidt reports a relationship with Mars Wrigley that includes: employment. Alana Firl reports a relationship with Mars Wrigley that includes: employment. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e41890.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Cai K., Yu Y., Zhang M., Kim K. Concentration, source, and total health risks of cadmium in multiple media in densely populated areas, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16 doi: 10.3390/ijerph16132269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliveira B.R.M., de Almeida A.-A.F., Santos N. de A., Pirovani C.P. Tolerance strategies and factors that influence the cadmium uptake by cacao tree. Sci. Hortic. 2021 doi: 10.1016/J.SCIENTA.2021.110733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vanderschueren R., Argüello D., Blommaert H., Montalvo D., Barraza F., Maurice L., Schreck E., Schulin R., Lewis C., Vazquez J.L., Umaharan P., Chavez E., Sarret G., Smolders E. Mitigating the level of cadmium in cacao products: reviewing the transfer of cadmium from soil to chocolate bar. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;781 doi: 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2021.146779. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.OECD . 1995. OECD ENVIRONMENT MONOGRAPH SERIES NO. 104 RISK REDUCTION MONOGRAPH NO. 5: CADMIUM. Paris. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gramlich A., Tandy S., Gauggel C., López M., Perla D., Gonzalez V., Schulin R. Soil cadmium uptake by cocoa in Honduras. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;612:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bali A.S., Sidhu G.P.S., Kumar V. Root exudates ameliorate cadmium tolerance in plants: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020;18:1243–1275. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01012-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sessitsch A., Kuffner M., Kidd P., Vangronsveld J., Wenzel W.W., Fallmann K., Puschenreiter M. The role of plant-associated bacteria in the mobilization and phytoextraction of trace elements in contaminated soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013;60:182–194. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wade J., Ac-Pangan M., Favoretto V.R., Taylor A.J., Engeseth N., Margenot A.J. Drivers of cadmium accumulation in Theobroma cacao L. beans: a quantitative synthesis of soil-plant relationships across the Cacao Belt. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0261989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis C., Lennon A.M., Eudoxie G., Sivapatham P., Umaharan P. Plant metal concentrations in Theobroma cacao as affected by soil metal availability in different soil types. Chemosphere. 2021;262 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Argüello D., Montalvo D., Blommaert H., Chavez E., Smolders E. Surface soil liming reduces cadmium uptake in cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) seedlings but is counteracted by enhanced subsurface Cd uptake. J. Environ. Qual. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jeq2.20123. jeq2.20123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramtahal G., Umaharan P., Davis C., Roberts C., Hanuman A., Ali L. Mitigation of cadmium uptake in Theobroma cacao L: efficacy of soil application methods of hydrated lime and biochar. Plant Soil. 2022;2022:1–16. doi: 10.1007/S11104-022-05422-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mourato M.P., Calixta C., Jiménez C., Valentina L., Fernández P., Rodrigues Reis C.E. Lowering the toxicity of Cd to theobroma cacao using soil amendments based on commercial charcoal and lime. Toxics. 2022;10:15. doi: 10.3390/TOXICS10010015. 10 (2022) 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramtahal G., Umaharan P., Hanuman A., Davis C., Ali L. The effectiveness of soil amendments, biochar and lime, in mitigating cadmium bioaccumulation in Theobroma cacao L. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;693 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arévalo-Gardini E., Arévalo-Hernández C.O., Baligar V.C., He Z.L. Heavy metal accumulation in leaves and beans of cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) in major cacao growing regions in Peru. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;605–606:792–800. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis C., Lennon A.M., Eudoxie G., Umaharan P. Genetic variation in bioaccumulation and partitioning of cadmium in Theobroma cacao L. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;640–641:696–703. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.05.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engbersen N., Gramlich A., Lopez M., Schwarz G., Hattendorf B., Gutierrez O., Schulin R. Cadmium accumulation and allocation in different cacao cultivars. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;678:660–670. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu T., Sun L., Meng Q., Yu J., Weng L., Li J., Deng L., Zhu Q., Gu X., Chen C., Teng S., Xiao G. Phenotypic and genetic dissection of cadmium accumulation in roots, nodes and grains of rice hybrids. Plant Soil. 2021;463:39–53. doi: 10.1007/s11104-021-04877-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt J.E., DuVal A., Isaac M.E., Hohmann P. At the roots of chocolate: understanding and optimizing the cacao root-associated microbiome for ecosystem services. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022;42(2):1–19. doi: 10.1007/S13593-021-00748-2. 42 (2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernández-Paz J., Cortés A.J., Hernández-Varela C.A., Mejía-de-Tafur M.S., Rodriguez-Medina C., Baligar V.C. Rootstock-mediated genetic variance in cadmium uptake by juvenile cacao (theobroma cacao L.) genotypes, and its effect on growth and physiology. Front. Plant Sci. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/FPLS.2021.777842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Almeida N.M., de Almeida A.-A.F., Santos N. de A., do Nascimento J.L., de Carvalho Neto C.H., Pirovani C.P., Ahnert D., Baligar V.C. Scion-rootstock interaction and tolerance to cadmium toxicity in juvenile Theobroma cacao plants. Sci. Hortic. 2022;300 doi: 10.1016/J.SCIENTA.2022.111086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bravo D., Braissant O. Cadmium-tolerant bacteria: current trends and applications in agriculture. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2022;74:311–333. doi: 10.1111/LAM.13594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janoušková M., Pavlíková D., Vosátka M. Potential contribution of arbuscular mycorrhiza to cadmium immobilisation in soil. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Bravo D. Bacterial cadmium-immobilization activity measured by isothermal microcalorimetry in cacao-growing soils from Colombia. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.910234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quiroga-Mateus R., López-Zuleta S., Chávez E., Bravo D. Cadmium-tolerant bacteria in cacao farms from antioquia, Colombia: isolation, characterization and potential use to mitigate cadmium contamination. Processes. 2022;10:1457. doi: 10.3390/pr10081457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bravo D., Pardo-Díaz S., Benavides-Erazo J., Rengifo-Estrada G., Braissant O., Leon-Moreno C. Cadmium and cadmium-tolerant soil bacteria in cacao crops from northeastern Colombia. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018;124:1175–1194. doi: 10.1111/jam.13698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guerra Sierra B., Arteaga-Figueroa L., Sierra-Pelaéz S., Alvarez J. Talaromyces santanderensis: a new cadmium-tolerant fungus from cacao soils in Colombia. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Cordoba-Novoa H.A., Cáceres-Zambrano J., Torres-Rojas E. Assessment of native cadmium-tolerant bacteria in cacao (Theobroma cacao L.)-cultivated soils in Cundinamarca-Colombia. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Cordoba-Novoa H.A., Cáceres-Zambrano J., Torres-Rojas E. Isolation of native cadmium-tolerant bacteria and fungi from cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) - cultivated soils in central Colombia. Heliyon. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curi M.A., Gutierrez A.M.E., Montesinos M.C.K.Y.E., Ibarra J.P.J., Atanacio J.W.P., Godoy D.D.R., Manrique A.S.S. ISOLATION, morphological identification and evaluation of cadmium tolerance of fungi from cocoa crops. Plant Cell Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. 2021:74–83. https://www.ikprress.org/index.php/PCBMB/article/view/6187 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feria-Cáceres P.F., Penagos-Velez L., Moreno-Herrera C.X. Tolerance and cadmium (Cd) immobilization by native bacteria isolated in cocoa soils with increased metal content. Microbiol. Res. 2022;13:556–573. doi: 10.3390/microbiolres13030039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaramillo-Mazo C., Bravo D., Guerra Sierra B.E., Alvarez J.C. Association between bacterial community and cadmium distribution across Colombian cacao crops. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024 doi: 10.1128/spectrum.03363-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmidt J.E., Dorman M., Ward A., Firl A. Rootstock, scion, and microbiome contributions to cadmium mitigation in five Indonesian cocoa cultivars. Pelita Perkebunan (a Coffee and Cocoa Research Journal) 2023;39:201–215. doi: 10.22302/ICCRI.JUR.PELITAPERKEBUNAN.V39I3.555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Motilal L.A., Zhang D., Mischke S., Meinhardt L.W., Umaharan P. Microsatellite-aided detection of genetic redundancy improves management of the International Cocoa Genebank. Trinidad, Tree Genetics & Genomes. 2013;9(6):1395–1411. doi: 10.1007/S11295-013-0645-5. 2013 9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greathouse D.C., Laetsch W.M., Phinney B.O. The shoot-growth rhythm of a tropical tree, theobroma cacao. Am. J. Bot. 1971;58:281. doi: 10.2307/2441407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niemenak N., Cilas C., Rohsius C., Bleiholder H., Meier U., Lieberei R. Phenological growth stages of cacao plants (Theobroma sp.): codification and description according to the BBCH scale. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2010;156:13–24. doi: 10.1111/J.1744-7348.2009.00356.X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sah R.N., Miller R.O. Spontaneous reaction for acid dissolution of biological tissues in closed vessels. Anal. Chem. 1992;64:230–233. doi: 10.1021/AC00026A026/ASSET/AC00026A026.FP.PNG_V03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caporaso J.G., Lauber C.L., Walters W.A., Berg-Lyons D., Lozupone C.A., Turnbaugh P.J., Fierer N., Knight R. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4516–4522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000080107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White T.J., Bruns T., Lee S., Taylor J.W. In: PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. Innis M.A., Gelfand D.H., Sninsky J.J., White T.J., editors. Academic Press, Inc.; New York: 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gardes M., Bruns T.D. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes ‐ application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993;2:113–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.1993.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Callahan B.J., McMurdie P.J., Rosen M.J., Han A.W., Johnson A.J.A., Holmes S.P. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McMurdie P.J., Holmes S. Phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lahti L., Shetty S. microbiome R package. 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oksanen J., Blanchet F.G., Friendly M., Kindt R., Legendre P., Mcglinn D., Minchin P.R., O’hara R.B., Simpson G.L., Solymos P., Henry M., Stevens H., Szoecs E., Wagner H. 2020. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lenth R.v. 2022. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mallick H., Rahnavard A., McIver L. 2020. MaAsLin 2: Multivariable Association in Population-Scale Meta-Omics Studies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beghini F., McIver L.J., Blanco-Míguez A., Dubois L., Asnicar F., Maharjan S., Mailyan A., Manghi P., Scholz M., Thomas A.M., Valles-Colomer M., Weingart G., Zhang Y., Zolfo M., Huttenhower C., Franzosa E.A., Segata N. Integrating taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling of diverse microbial communities with biobakery 3. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/ELIFE.65088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bateman A., Martin M.J., Orchard S., Magrane M., Ahmad S., Alpi E., Bowler-Barnett E.H., Britto R., Bye-A-Jee H., Cukura A., Denny P., Dogan T., Ebenezer T.G., Fan J., Garmiri P., da Costa Gonzales L.J., Hatton-Ellis E., Hussein A., Ignatchenko A., Insana G., Ishtiaq R., Joshi V., Jyothi D., Kandasaamy S., Lock A., Luciani A., Lugaric M., Luo J., Lussi Y., MacDougall A., Madeira F., Mahmoudy M., Mishra A., Moulang K., Nightingale A., Pundir S., Qi G., Raj S., Raposo P., Rice D.L., Saidi R., Santos R., Speretta E., Stephenson J., Totoo P., Turner E., Tyagi N., Vasudev P., Warner K., Watkins X., Zaru R., Zellner H., Bridge A.J., Aimo L., Argoud-Puy G., Auchincloss A.H., Axelsen K.B., Bansal P., Baratin D., Batista Neto T.M., Blatter M.C., Bolleman J.T., Boutet E., Breuza L., Gil B.C., Casals-Casas C., Echioukh K.C., Coudert E., Cuche B., de Castro E., Estreicher A., Famiglietti M.L., Feuermann M., Gasteiger E., Gaudet P., Gehant S., Gerritsen V., Gos A., Gruaz N., Hulo C., Hyka-Nouspikel N., Jungo F., Kerhornou A., Le Mercier P., Lieberherr D., Masson P., Morgat A., Muthukrishnan V., Paesano S., Pedruzzi I., Pilbout S., Pourcel L., Poux S., Pozzato M., Pruess M., Redaschi N., Rivoire C., Sigrist C.J.A., Sonesson K., Sundaram S., Wu C.H., Arighi C.N., Arminski L., Chen C., Chen Y., Huang H., Laiho K., McGarvey P., Natale D.A., Ross K., Vinayaka C.R., Wang Q., Wang Y., Zhang J. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D523–D531. doi: 10.1093/NAR/GKAC1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/BIOINFORMATICS/BTP324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galvis D.A., Jaimes-Suárez Y.Y., Rojas Molina J., Ruiz R., León-Moreno C.E., Carvalho F.E.L. Unveiling cacao rootstock-genotypes with potential use in the mitigation of cadmium bioaccumulation. Plants. 2023;12:2941. doi: 10.3390/PLANTS12162941/S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zakariyya F., Santoso T.I., Abdoellah S. Absorption of cadmium and its effect on the growth of halfsib family of three cocoa clones seedling. Pelita Perkebunan (a Coffee and Cocoa Research Journal) 2022;38:171–178. doi: 10.22302/ICCRI.JUR.PELITAPERKEBUNAN.V38I3.534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin L., Wu X., Deng X., Lin Z., Liu C., Zhang J., He T., Yi Y., Liu H., Wang Y., Sun W., Xu Z. Mechanisms of low cadmium accumulation in crops: a comprehensive overview from rhizosphere soil to edible parts. Environ. Res. 2024;245 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.118054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu Z.M., Wang J.F., Li W.L., Wang Y.F., He T., Wang F.P., Lu Z.Y., Li Q.S. Nitrogen fertilizer affects rhizosphere Cd re-mobilization by mediating gene AmALM2 and AmALMT7 expression in edible amaranth roots. J. Hazard Mater. 2021;418 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu X., Zhao J.T., Liu X., Sun L.X., Tian J., Wu N. Cadmium pollution impact on the bacterial community structure of arable soil and the isolation of the cadmium resistant bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/FMICB.2021.698834/FULL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luo Y., Liao M., Zhang Y., Xu N., Xie X., Fan Q. Cadmium resistance, microbial biosorptive performance and mechanisms of a novel biocontrol bacterium Paenibacillus sp. LYX-1. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2022;29:68692–68706. doi: 10.1007/S11356-022-20581-8/METRICS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumar V., Singh S., Singh G., Dwivedi S.K. Exploring the cadmium tolerance and removal capability of a filamentous fungus Fusarium solani. Geomicrobiol. J. 2019;36:782–791. doi: 10.1080/01490451.2019.1627443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuang X., Si K., Song H., Peng L., Chen A. Lime-phosphorus fertilizer efficiently reduces the Cd content of rice: physicochemical property and biological community structure in Cd-polluted paddy soil. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/FMICB.2021.749946/FULL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo Y., Cheng S., Fang H., Yang Y., Li Y., Zhou Y. Responses of soil fungal taxonomic attributes and enzyme activities to copper and cadmium co-contamination in paddy soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;844 doi: 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2022.157119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blommaert H., Aucour A.M., Wiggenhauser M., Moens C., Telouk P., Campillo S., Beauchêne J., Landrot G., Testemale D., Pin S., Lewis C., Umaharan P., Smolders E., Sarret G. From soil to cacao bean: unravelling the pathways of cadmium translocation in a high Cd accumulating cultivar of Theobroma cacao L. Front. Plant Sci. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/FPLS.2022.1055912/FULL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yabe S., Sakai Y., Abe K., Yokota A. Diversity of ktedonobacteria with actinomycetes-like morphology in terrestrial environments. Microbes Environ. 2017;32:61. doi: 10.1264/JSME2.ME16144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abbas S.Z., Rafatullah M., Hossain K., Ismail N., Tajarudin H.A., Abdul Khalil H.P.S. A review on mechanism and future perspectives of cadmium-resistant bacteria. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;15(1):243–262. doi: 10.1007/S13762-017-1400-5. 15 (2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li X., Islam M.M., Chen L., Wang L., Zheng X. Metagenomics-guided discovery of potential bacterial metallothionein genes from the soil microbiome that confer Cu and/or Cd resistance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020;86 doi: 10.1128/AEM.02907-19/SUPPL_FILE/AEM.02907-19-S0001.PDF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zheng X., Chen L., Chen M., Chen J., Li X. Functional metagenomics to mine soil microbiome for novel cadmium resistance genetic determinants. Pedosphere. 2019;29:298–310. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(19)60804-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gil J.P., López-Zuleta S., Quiroga-Mateus R.Y., Benavides-Erazo J., Chaali N., Bravo D. Cadmium distribution in soils, soil litter and cacao beans: a case study from Colombia. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022;19:2455–2476. doi: 10.1007/s13762-021-03299-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chavez E., He Z.L., Stoffella P.J., Mylavarapu R.S., Li Y.C., Baligar V.C. Chemical speciation of cadmium: an approach to evaluate plant-available cadmium in Ecuadorian soils under cacao production. Chemosphere. 2016;150:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ramtahal G., Yen I.C., Bekele I., Bekele F., Wilson L., Maharaj K., Harrynanan L., Ramtahal G., Yen I.C., Bekele I., Bekele F., Wilson L., Maharaj K., Harrynanan L. Relationships between cadmium in tissues of cacao trees and soils in plantations of Trinidad and Tobago. Food Nutr. Sci. 2016;7:37–43. doi: 10.4236/FNS.2016.71005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.López J.E., Arroyave C., Aristizábal A., Almeida B., Builes S., Chavez E. Reducing cadmium bioaccumulation in Theobroma cacao using biochar: basis for scaling-up to field. Heliyon. 2022;8 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ramtahal G., Umaharan P., Hanuman A., Davis C., Ali L. The effectiveness of soil amendments, biochar and lime, in mitigating cadmium bioaccumulation in Theobroma cacao L. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;693 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Argüello D., Dekeyrel J., Chavez E., Smolders E. Gypsum application lowers cadmium uptake in cacao in soils with high cation exchange capacity only: a soil chemical analysis. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022 doi: 10.1111/EJSS.13230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.S S., W S. Cadmium-tolerant bacteria reduce the uptake of cadmium in rice: potential for microbial bioremediation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013;94:94–103. doi: 10.1016/J.ECOENV.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blommaert H., De Meese C., Wiggenhauser M., Sarret G., Smolders E. Evidence of cadmium transport via the phloem in cacao seedlings. Plant Soil. 2024;3:1–13. doi: 10.1007/S11104-024-06753-0/FIGURES/4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dashner Z. 2024. Novel Biotechnological Approaches to Understand and Reduce Cadmium in the Iron Uptake Pathway of Theobroma Cacao. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Blommaert H., Castillo-Michel H., Veronesi G., Tucoulou R., Beauchêne J., Umaharan P., Smolders E., Sarret G. Ca-oxalate crystals are involved in cadmium storage in a high Cd accumulating cultivar of cacao. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2024 doi: 10.1016/J.ENVEXPBOT.2024.105713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kaminsky L.M., Trexler R.V., Malik R.J., Hockett K.L., Bell T.H. The inherent conflicts in developing soil microbial inoculants. Trends Biotechnol. 2019;37:140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Valls M., Atrian S., De Lorenzo V., Fernández L.A. Engineering a mouse metallothionein on the cell surface of Ralstonia eutropha CH34 for immobilization of heavy metals in soil. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18(6):661–665. doi: 10.1038/76516. 18 (2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Valls M., De Lorenzo V., Gonzàlez-Duarte R., Atrian S. Engineering outer-membrane proteins in Pseudomonas putida for enhanced heavy-metal bioadsorption. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2000;79:219–223. doi: 10.1016/S0162-0134(99)00170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li X., Ren Z., Crabbe M.J.C., Wang L., Ma W. Genetic modifications of metallothionein enhance the tolerance and bioaccumulation of heavy metals in Escherichia coli. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021;222 doi: 10.1016/J.ECOENV.2021.112512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study has not been provided because it is confidential.