Abstract

The agroforestry system with high biodiversity enhances ecosystem stability and reduces vulnerability to environmental disturbances and diseases. Investigating the mechanisms of interspecies allelopathic interactions for disease suppression in agroforestry offers a sustainable strategy for plant disease management. Here, we used Panax ginseng cultivated under Pinus koraiensis forests, which have low occurrences of Alternaria leaf spot, as a model to explore the role of allelochemicals in disease suppression. Our findings demonstrate that foliar application of P. koraiensis needle leachates effectively enhanced the resistance of P. ginseng against Alternaria leaf spot. Using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, we identified and quantified endo-borneol as a key compound in P. koraiensis leachates and confirmed its ability to prime resistance in neighboring P. ginseng plants. We discovered that endo-borneol not only directly activates defense-related pathways in P. ginseng to confer resistance but also indirectly recruits its beneficial rhizospheric microbiota by promoting the secretion of ginsenosides, thereby triggering induced systemic resistance. Notably, higher concentrations of endo-borneol, ranging from 10 to 100 mg/l, have a greater capacity to induce plant resistance and enhance root secretion, thereby recruiting more microbiota compared to lower concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 1 mg/l. Additionally, endo-borneol exhibits antifungal activities against the growth of the pathogen Alternaria panax when concentrations exceeded 10 mg/l. These results reveal the multifaceted functions of allelochemical endo-borneol in disease suppression within agroforestry systems and highlight its potential as an environmentally friendly agent for sustainable agriculture.

Key words: agroforestry, allelopathy, induced resistance, rhizosphere microbiome, secondary metabolites

This study provides evidence that endo-borneol in Pinus koraiensis needle leachates enhances Panax ginseng resistance to Alternaria leaf spot. Endo-borneol exhibits multifaceted functions in disease suppression, both by directly activating defense-related pathways and indirectly by modifying root secretions to recruit beneficial microbes, thus priming induced systemic resistance and inhibiting pathogen growth at higher concentrations.

Introduction

Agroforestry systems, characterized by high biodiversity, enhance ecosystem stability and reduce vulnerability to environmental disturbances. This contributes to decreased crop disease prevalence and lowers the risk of pesticide pollution (Yang et al., 2014; Ain et al., 2023). Allelopathy plays a crucial role in maintaining resilience within agroforestry systems (Ratnadass et al., 2012), reducing plant disease infections (Ain et al., 2023). Research has consistently shown that allelochemicals serve multifunctional roles, including antimicrobial activity and induction of plant resistance, to impart resistance to plants against pathogen infections (Gahukar, 2012; Verma et al., 2012; Ye et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023). Additionally, certain allelochemicals affect plant metabolism and secretion, thereby modifying the associated microbial communities (Wu et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2010; Fernandez et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2018; Shi and Shao, 2022). Importantly, some rhizosphere microorganisms show intrinsic antagonistic abilities against pathogens and can trigger induced systemic resistance (ISR) in various plant species to enhance disease resistance (Doornbos et al., 2012; Kong et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2022). Despite these insights, the specific allelochemicals and their underlying mechanisms that regulate plant metabolism and the rhizosphere microbiome’s impact on disease suppression in agroforestry systems remain largely unknown. Therefore, fully exploiting the potential of allelochemicals in agroforestry biodiversity systems will provide a sustainable strategy for plant disease management.

The agroforestry system has been successfully employed in recent years for cultivating shade-loving medicinal herbaceous species under forest canopies, including Panax ginseng, Panax notoginseng, Coptis chinensis, and Gastrodia elata (Jing et al., 2009; Yang, 2016; Ye et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2020; Li et al., 2023). Pine forests are reported as the main tree species for the cultivation of Panax genus medicinal herbs, providing suitable habitats that contribute to lower disease prevalence (Ye et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023). Alternaria leaf spot, one of the main foliar diseases of P. ginseng, can be significantly mitigated when P. ginseng is cultivated under a canopy of Pinus koraiensis Siebold et Zucc). This mitigation is possibly enhanced by the allelopathic effects of pine forests, which include the inhibition of microbial growth and induction of resistance in adjacent plants (Aslam et al., 2017; Bachheti et al., 2020; Chomel et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023). We hypothesize that foliar sprays with leachates from P. koraiensis pine needles can alleviate Alternaria leaf spot.

In this study, we investigated the allelopathic effects of needle leachates from P. koraiensis on the severity of Alternaria leaf spot under forest conditions, identified the active allelochemicals in the pine needle leachates, and elucidated the mechanisms by which endo-borneol reduces this disease. Through these analyses, we aim to reveal the allelochemical mechanisms underlying disease suppression in agroforestry systems and develop a promising strategy for disease control.

Results

Foliar spray of pine needle leachates alleviates Alternaria leaf spot

Field experiments (Figures 1A and 1B) demonstrated a significant reduction in the severity of Alternaria leaf spot on both 2-year-old and 4-year-old P. ginseng plants after the application of foliar spray with P. koraiensis needle leachates (Figures 2A and 2B). The leachates did not exhibit significant inhibitory activity against the mycelial growth of Alternaria panax at concentrations ranging from 0 to 50 g/l (Supplemental Figure 1). The efficacy of the leachates was categorized based on their concentrations in the field into low concentration (0.25–1 g/l) and high concentration (5–50 g/l) groups, with high concentrations generally achieving higher disease control efficiency (Figures 2A and 2B).

Figure 1.

Flow charts illustrating the identification of main allelochemicals in P. koraiensis needle leachates, assessing their allelopathic effects on P. ginseng for disease control, and examining the underlying mechanisms.

(A) Determination of the main compounds in P. koraiensis leachates and their effects on pathogen growth.(B) Assessment of disease severity in P. ginseng under field conditions following leaf sprays of the leachates and the main allelochemical at various concentrations. The rhizosphere soil of P. ginseng was collected to assess seedling emergence, analyze the microbial community, and profile metabolites. Culturable microbes in the rhizosphere were isolated, and those related to disease severity were validated for their ability to induce systemic resistance (ISR) and their relationships with key soil metabolites regulated by the allelochemical.(C) Examination of the effects of allelochemical foliar applications on gene expression regulation in the above- and belowground parts of P. ginseng.

Figure 2.

Assessment of the allelopathic effects of P. koraiensis needle leachates on disease control and identification of endo-borneol within the leachates.

(A and B) Effects of leaf spray of the leachates on the severity of Alternaria leaf spot on (A) 2-year-old and (B) 4-year-old P. ginseng plants.(C) Total ion chromatogram (TIC) of P. koraiensis needle leachates obtained via GC–MS/MS for qualitative analysis. The mass spectrum of endo-borneol is displayed in the top right of the figure.(D) TIC of standard endo-borneol analyzed via GC–MS/MS. The mass spectrum of endo-borneol is also displayed in the top right of the figure.(E) Monthly precipitation in Benxi during the growing season of P. ginseng for the past six consecutive years (2016–2021). Monthly precipitation levels are categorized into low, medium, and high.(F) Concentration of endo-borneol in simulated indoor needle leachates analyzed via GC/MSD. Data are presented as the mean ± SE, bars indicate SEs, and different letters indicate significant differences analyzed by one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05.

Endo-borneol identification and quantification in needle leachates by GC–MS

Based on the screening criteria of a monthly detection frequency above 60% during the growing season, similarity with the NIST14 and NIST14s libraries greater than 80%, and a peak area percentage above 0.01%, a total of 15 compounds were identified in the leachates from P. koraiensis needles via gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) (Figure 1A; Supplemental Table 1; Supplemental Figure 2). The identified compounds from the needle leachates included monoterpenes such as endo-borneol (CAS 507-70-0), alpha-terpineol (CAS 98-55-5), citronellol (CAS 106-22-9), neodihydrocarveol (CAS 18675-34-8), bornyl acetate (CAS 76-49-3), 2-cyclohexen-1-one, 3-methyl-6-(1-methylethyl)- (CAS 89-81-6), cyclohexanol, 2-methyl-5-(1-methylethenyl)- (CAS 619-01-2), bicyclo [3.1.1] hept-2-ene-2-methanol, 6,6-dimethyl- (CAS 515-00-4), bicyclo [3.1.1] hept-3-en-2-one, 4,6,6-trimethyl-, (1S)- (CAS 1196-01-6), and p-mentha-1,5-dien-8-ol (CAS 1686-20-0); sesquiterpenoids including alpha-cadinol (CAS 481-34-5) and tau-muurolol (CAS, 19912-62-0); pentanols as prenol (CAS 556-82-1); oxolanes as 2-furanmethanol, 5-ethenyltetrahydro-alpha, alpha, 5-trimethyl-, cis- (CAS 5989-33-3), and other terpenes such as 3-cyclohexen-1-ol, 4-methyl-1-(1-methylethyl)-, (R)- (CAS, 20126-76-5) (Supplemental Figure 2B). Among these compounds, the target compound endo-borneol was selected due to its high similarity with the NIST14 and NIST14s libraries (greater than 90%), a monthly detection rate of 100%, and a peak area percentage exceeding 1% (Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Figure 2). The presence of endo-borneol in P. koraiensis leachates was further confirmed using GC–MS (Supplemental Figures 3C and 4) and GC–MS/MS (Figures 2C and 2D) by comparing the retention time (RT) and mass spectrum with the standard for endo-borneol. The peak area percentages for endo-borneol in leachates of each month vary, ranging from 1.76% to 5.39% (Supplemental Table 1).

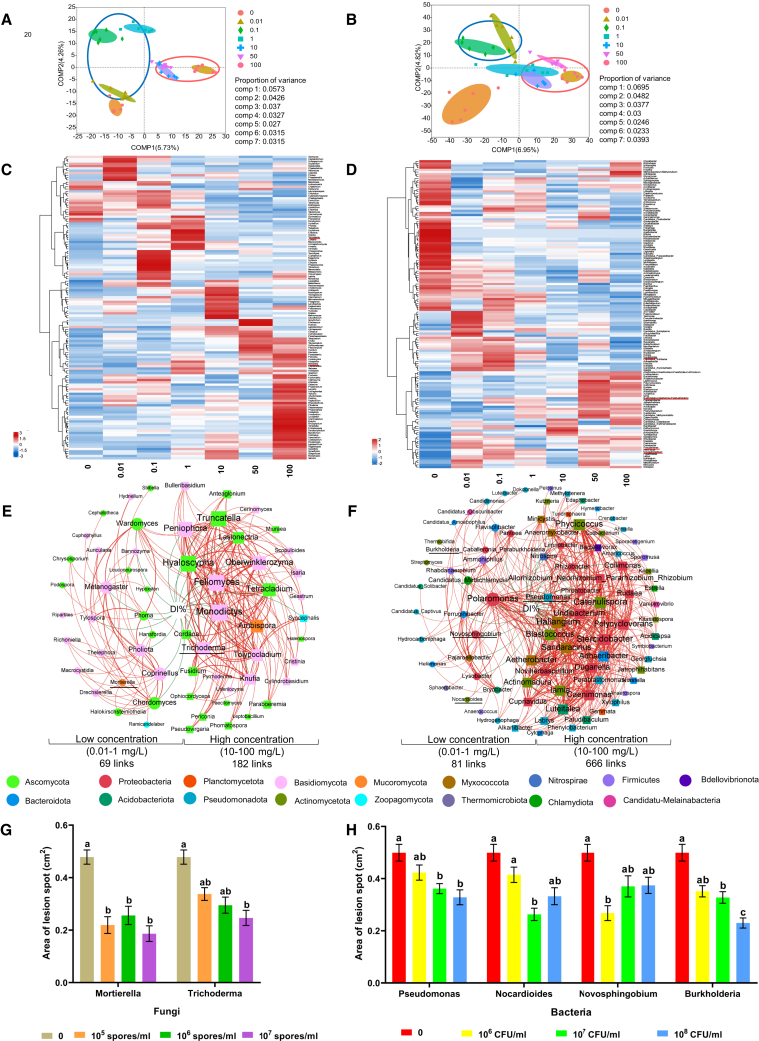

Figure 4.

Effects of endo-borneol leaf sprays on the rhizosphere microbiome of 4-year-old P. ginseng plants and the ability of key isolated microbes to trigger ISR.

Partial least-squares discriminant analysis identifies the community structure and composition of fungi and bacteria in rhizosphere soil: (A) fungi and (B) bacteria at the operational taxonomic unit (OTU) level. Proportions of variance for fungi and bacteria are listed in the table at the bottom right. Heatmaps displaying the relative abundance of genera that significantly differ from the CK in (C) fungi and (D) bacteria. Network analysis showing the negative correlations between the Alternaria disease severity index (DI%) and the relative abundance of rhizosphere microbial genera: direct and indirect negative correlations of DI% with (E) fungi and (F) bacteria at the genus level (p < 0.05, and Pearson’s |R| > 0.75). Circles and squares represent genera with negative correlations to DI% under low (0.01–1 mg/l) and high concentrations (10–100 mg/l), respectively. It includes genera that exhibited significant negative correlations with DI% and those whose relative abundance had a significant positive correlation with the aforementioned genera. The size of a node and its label are proportional to the number of connections. Red and green lines denote significant positive and negative linear relationships, respectively. Different phyla are indicated by different colors in nodes. Genera selected for resistance induction assessment are underscored with a bold line. Effects of inoculating target genera on resistance induction in 2-year-old P. ginseng plants against Alternaria leaf spot: lesion areas of Alternaria leaf spot on P. ginseng plants were scanned for (G) fungi and (H) bacteria at different inoculating concentrations. Data are presented as the mean ± SE, bars indicate SE, and different letters indicate significant differences analyzed by one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05. CFU, colony-forming unit.

Indoor needle-leaching simulations were conducted to quantify the actual concentrations of endo-borneol under P. koraiensis forests during the growing season of P. ginseng, based on local precipitation patterns and the duration of monthly rainfall over a continuous six-year period (2016–2021). Monthly rainfall intensities were categorized into low (34.6 mm), medium (104.2 mm), and high (285.8 mm) levels (Figure 2E). Based on the indoor simulated leaching, concentrations of endo-borneol corresponding to these rainfall intensities were quantified as 0.0041, 0.0104, and 0.0158 mg/l, respectively (Figure 2F and Supplemental Table 2).

Foliar spray of endo-borneol reduces the severity of Alternaria leaf spot

Increasing concentrations of endo-borneol in foliar spray (Figure 1B) significantly reduced the disease severity of Alternaria leaf spot on 2-year-old and 4-year-old P. ginseng plants (Figures 3A and 3B). Endo-borneol also effectively triggered resistance against Alternaria infections in Panax (Panax quinquefolius, P. notoginseng) and Solanum (Solanum lycopersicum) plants (Supplemental Figure 5). In addition, endo-borneol had no adverse effects on the growth of P. ginseng (Supplemental Figure 6). Consistent with the trends observed in leachate treatments, the control efficacy of endo-borneol could be categorized into low (0.01–1 mg/l) and high (10–100 mg/l) concentrations based on its impact on disease severity (Figures 3A and 3B). Notably, endo-borneol exhibited no discernible antifungal activity at low concentrations but demonstrated a dose-dependent antifungal effect on the growth of A. panax, significantly reducing colony diameter and mycelial biomass at concentrations above 10 mg/l (Figure 3C–3E).

Figure 3.

Allelopathic effects of endo-borneol on disease control and pathogen growth.

Effects of endo-borneol leaf sprays on the severity of Alternaria leaf spot on (A) 2-year-old and (B) 4-year-old P. ginseng plants. Inhibitory effects of endo-borneol against (C) colony growth, (D) colony diameter and (E) mycelial biomass of A. panax. Data are shown as the mean ± SE, bars indicate SEs, and different letters indicate significant differences analyzed by one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05.

Foliar spray of endo-borneol recruits beneficial rhizosphere microbiota to induce resistance

Pot experiments with unsterilized rhizosphere soil treated with endo-borneol at concentrations of 0.1 mg/l and 100 mg/l (Figure 1B) demonstrated enhanced growth vigor in P. ginseng seeds compared to those in sterilized soil (Supplemental Figure 7). These results indicate that the function of the rhizosphere microbiome was altered following the foliar application of endo-borneol. To further explore the diversity and composition of the rhizosphere soil microbiome affected by different concentrations of endo-borneol, soil samples from seven treatments (0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 50, and 100 mg/l) were analyzed. A total of 5675 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of fungi (Supplemental Table 3) and 8932 OTUs of bacteria (Supplemental Table 4) were identified from 42 samples, with both groups achieving an average Good’s coverage of 99.09% and reaching a sequence similarity of 97%. Compared to control groups, endo-borneol treatments had a more significant impact on community richness and diversity in fungi than in bacteria (Supplemental Figure 8). Partial least-squares discriminant analysis showed distinct separations in both fungal (Figure 4A) and bacterial (Figure 4B) communities at the OTU level following the leaf spray of endo-borneol. Notably, both fungal and bacterial communities treated with low concentrations of endo-borneol (0.1–1 mg/l) were clearly distinct from those treated with high concentrations (10–100 mg/l) (Figures 4A and 4B).

Furthermore, heatmap analysis demonstrated that both low and high concentrations of endo-borneol differentially shifted the composition of rhizosphere fungi (Figure 4C) and bacteria (Figure 4D) at the genus level. For the fungal community, a total of 132 fungal genera were significantly regulated by endo-borneol (Figure 4C). These genera can be classified into two clusters: one consisting of 54 genera notably enriched by low concentrations of endo-borneol (0.1–1 mg/l), and another comprising 78 genera significantly enriched by high concentrations of endo-borneol (10–100 mg/l). Among these, 82 genera were upregulated by both low and high concentrations, with 30 genera upregulated exclusively at low concentrations and 12 exclusively at high concentrations. The relative abundance of 143 bacterial genera in the rhizosphere was altered by endo-borneol (Figure 4D). These genera could be categorized into two clusters: one included 70 genera whose relative abundance was suppressed after treatments with increasing concentrations of endo-borneol, while the other comprised 73 genera whose abundance increased with increasing endo-borneol concentrations. Among the upregulated genera, 54 showed increased abundance at both low and high concentrations, 16 were only upregulated at low concentrations and 3 at high concentrations.

The co-occurrence negative networks for fungi (Figure 4E) and bacteria (Figure 4F) consisted of genera that exhibited significant negative correlations with disease severity index (DI%) and those whose relative abundance had a significant positive correlation with the aforementioned genera at both low and high concentrations. The network at high concentrations contained more genera related to the severity of Alternaria leaf spot than those at low concentrations. Specifically, within the fungal co-occurrence network (Figure 4E), 26 genera were negatively correlated with disease severity at low concentrations, compared to 35 genera at high concentrations. In the bacteria co-occurrence network (Figure 4F), 30 genera were negatively correlated to DI% at low concentrations, compared to 62 at high concentrations. The negative networks at high concentrations were more complex, reflecting enhanced topological properties, including a greater total number of links (edges between two nodes) and higher average degree (number of edges connected to a node) (Figures 4E and 4F).

To determine the function of specific genera in the network, we selected Mortierella, Novosphingobium, Nocardiodes, and Burkholderia as representative genera whose relative abundance was negatively correlated with DI% at low concentrations. Conversely, Trichoderma and Pseudomonas were chosen for their negative correlation with DI% at high concentrations to assess their ability to induce resistance in P. ginseng against A. panax (Figure 1B). All six isolates significantly reduced the lesion area caused by A. panax infection, although the effective concentration of fungi/bacteria required to reduce lesion areas varied among the genera (Figures 4G and 4H).

Foliar spray of endo-borneol triggers plant defense and secondary metabolism

To study the effects of endo-borneol application on P. ginseng, comprehensive transcriptomic analyses of both aboveground and belowground gene expression were conducted (Figure 1C). Through weighted gene co-expression network analysis, three distinct gene modules (labeled with different colors) were identified, each representing clusters of highly interconnected and co-expressed genes (Supplemental Figure 9B). Specifically, the blue module contained 14571 genes and showed a significant positive correlation with leaves treated with endo-borneol at concentrations of 0.1 mg/l and 100 mg/l (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.43 and 0.42, respectively). The brown module contained 653 genes that were significantly positively correlated with roots treated with 100 mg/l endo-borneol (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.83). The turquoise module contained 17802 genes that were significantly positively correlated with roots treated with 0.1 mg/l endo-borneol (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.46) (Supplemental Figure 9C). In the blue module, 165 hub genes were identified from leaf samples treated with 0.1 mg/l endo-borneol (Supplemental Figure 9D), along with 256 hub genes from leaf samples treated with 100 mg/l endo-borneol (Supplemental Figure 9E), both selected based on module membership > 0.6 and gene significance > 0.7. Using the same module membership and gene significance filtering criteria, 64 hub genes were identified from the turquoise module in root samples treated with 0.1 mg/l endo-borneol (Supplemental Figure 9F), and 575 hub genes were identified from the brown module in root samples treated with 100 mg/l endo-borneol (Supplemental Figure 9G).

To elucidate the distinct features and biological significance of each group, identification of significant Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways and plant-defense-related Gene Ontology (GO) terms were performed (Figure 5). Except for fundamental cellular and physiological processes, endo-borneol influenced additional pathways and GOs with specific functions. For example, treatment with 0.1 mg/l endo-borneol led to the upregulation of secondary metabolic processes such as flavonoid, terpene, and benzoxazinoid metabolism in leaves, and hormone-mediated signaling pathways (such as auxin and ethylene signaling) in roots. At a concentration of 100 mg/l, endo-borneol treatment enriched a broader spectrum of significant KEGG pathways and GOs in both leaves and roots. In leaves, more KEGG pathways and GOs were associated with protecting plants from external stimuli, especially those that regulate defense responses to other organisms. In roots, the treatment triggered responses to stress and biological processes related to lipid and carbohydrate metabolism (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Co-expression analysis of transcriptome specificity in leaf and root samples treated with varying concentrations of endo-borneol by foliar spraying.

Left: significant Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways associated with each module. Plant-defense-related biological processes organized by significant Gene Ontology (GO) terms are shown on the right side. Red, green, blue, and purple squares represent genes within the four modules, respectively. Each column within the group corresponds to a different sample.

Foliar spray of endo-borneol modulates root secretions to enrich ISR-associated microbiota

A total of 859 metabolites were identified from all rhizosphere soil samples of P. ginseng using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) based on the KEGG database (https://www.kegg.jp/) (Figure 1B and Supplemental Figure 10). Principal-component analysis revealed clear discrimination among experimental groups from three provenances in both positive and negative modes (Supplemental Figure 11). There were 365 and 375 differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs) (variable important in projection >1 and p < 0.05) between the control (0 mg/l) rhizosphere soil and soil from plants that received foliar sprays of 0.1 mg/l or 100 mg/l endo-borneol (Supplemental Tables 5 and 6). In the KEGG pathway analysis, DEMs were enriched in 28 metabolic pathways in the 0.1 mg/l treatment and 36 pathways in the 100 mg/l treatment (pathway impact > 0). Specifically, DEMs were enriched in six and eight KEGG pathways (pathway impact > 0 and p < 0.05) in rhizosphere soils from the 0.1 mg/l and 100 mg/l endo-borneol treatment, respectively (Figure 6A and Supplemental Figure 12). Collectively, treatments with endo-borneol increased the secretion of 24 metabolites and decreased the secretion of nine metabolites in the soil (Figure 6A). Based on KEGG compound classification, these metabolites include three phytochemical compounds in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (nine saponins and one lipid in the biosynthesis of various plant secondary metabolites), two nucleic acids in pyrimidine metabolism, and seven lipids in brassinosteroid, steroid, cutin, suberine and wax biosynthesis. The nine metabolites downregulated by endo-borneol included four phytochemical compounds in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, one phytochemical compound in the biosynthesis of various plant secondary metabolites, one lipid in cutin, suberine, and wax biosynthesis, and one nucleic acid in pyrimidine metabolism.

Figure 6.

Soil metabolites involved in significantly enriched KEGG pathways.

(A) Heatmaps showing the concentrations of metabolites from rhizosphere soil from plants that received foliar spray of 0.1 and 100 mg/l endo-borneol. (B) Effects of metabolites on the growth regulation of key genera. The x-axis shows the concentrations of metabolites and the y-axis shows the log2 fold change (treatment/0 mg/l). Data are presented as the mean ± SE, bars indicate SE. The color of each bar represents the effect on microbial strain growth relative to the control (0 mg/l): significantly promoted (red), significantly inhibited (green), and no significant effect (orange).

To further investigate the effect of these metabolites on growth of the identified ISR-associated isolates, seven ginsenosides (ginsenoside F2, ginsenoside Rh1, ginsenoside Rb1, ginsenoside C-K, ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Rg3, and protopanaxatriol), two non-ginsenoside compounds (oleic acid, and eugenol), and four compounds that were downregulated by endo-borneol (2-phenylacetamide, coumarin, phenylpyruvic acid, and matairesinol) were tested (Figure 6A). The results indicated that the ginsenosides (ginsenoside F2, Rh1, Rb1, C-K, Rg1, Rg3, and protopanaxatriol) promoted the growth of Mortierella, Novosphingobium, Nocardiodes, and Burkholderia (Figure 6B). Specifically, Pseudomonas growth was mainly enhanced by the upregulated ginsenosides (Rh1, Rg1, Rg3, and C-K), while Trichoderma growth wasenhanced by the non-ginsenoside compound (eugenol). Interestingly, the downregulated metabolites (coumarin, phenylpyruvic acid, and matairesinol) were found to slightly promote or have no effect on the growth of Burkholderia, Nocardiodes, Novosphingobium, and Mortierella at low concentrations, but inhibit the growth of Pseudomonas and Trichoderma (Figure 6B). This suggests that the downregulation of these metabolites alleviates the suppression of the growth of ISR-associated microbiota.

Discussion

Agroforestry systems are characterized by high biodiversity and low disease occurrence. In the current study, we investigated the interspecific allelopathic interactions within agroforestry systems that contribute to plant disease suppression by inducing resistance and manipulating rhizosphere microbiomes. We found that the incidence of Alternaria leaf spot on P. ginseng was significantly reduced when the plants were cultivated under P. koraiensis forests. Endo-borneol, derived from the needle leachates of P. koraiensis, could directly induce resistance in P. ginseng against Alternaria leaf spot by increasing the expression of defense-related genes. Additionally, it indirectly recruited beneficial rhizospheric microbiota by enhancing the biosynthesis and secretion of secondary metabolites from the roots of P. ginseng to trigger ISR (Figure 7). Our study supports the consensus that interspecies allelopathic interactions enhance ecosystem stability and reduce its vulnerability to diseases (Grewal et al., 1999; Ehrmann and Ritz, 2014).

Figure 7.

Conceptual model for allelochemical-mediated interspecies interactions among P. koraiensis, P. ginseng, and rhizosphere beneficial microbes via soil metabolites.

The main compound, endo-borneol, found in P. koraiensis needle leachates, can induce a defense system in P. ginseng by causing a shift in soil metabolite composition, which facilitates the recruitment of beneficial microbes in the rhizosphere.

Endo-borneol acts as a plant-derived allelochemical, priming the resistance of P. ginseng against leaf diseases. The allelochemicals released through volatilization, leaching, root exudation, and residue decomposition have been found to alter the surrounding microhabitat, inhibit microbial growth, and modulate the growth of nearby crops (Li et al., 2023). Field experiments confirmed that endo-borneol, as the main allelochemical in the leachates of P. koraiensis, exhibited a suppressive pattern against Alternaria leaf spot similar to that of the leachates, indicating that endo-borneol is a major allelochemical in the leachates that mediates disease suppression. Although endo-borneol showed antifungal activity against A. panax at concentrations exceeding 10 mg/l, the actual concentration in the forest environment, as simulated by indoor leaching, is far below this inhibitory level, suggesting a greater likelihood of triggering resistance in P. ginseng. Several studies have shown that many allelochemicals are effective not only due to their antimicrobial properties (Tholl and Lee, 2011; Riedlmeier et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2022a) but also because they induce both local and systemic resistance in plants against subsequent pathogen attacks (Kuc, 1982; Walters and Fountaine, 2009). Allelochemicals act as elicitors or signals to trigger SAR, protecting host plants from pathogen attack by activating innate immune systems through salicylic acid or methyl jasmonate-dependent processes (Baldwin et al., 2006; Walters et al., 2013; Riedlmeier et al., 2017). Consistent with observations that high concentrations of endo-borneol enhance resistance in P. ginseng, it is evident that higher concentrations activate more defense-related GOs, including inositol phosphate metabolism, N-glycan biosynthesis, and benzoxazinoid biosynthesis in leaves (Jia et al., 2019; von Schaewen et al., 2008; Yop et al., 2023; de Bruijn et al., 2018). In contrast to the 0.1 mg/l treatment, leaves treated with 100 mg/l endo-borneol upregulated more genes related to hormone-mediated signaling pathways, including those involved in auxin, abscisic acid, brassinosteroid, gibberellin, and steroid hormone pathways. This hormone crosstalk integrates a complex network that tailors plant responses to diverse abiotic and biotic stresses (Aerts et al., 2021). However, the deeper mechanisms involved in endo-borneol-mediated resistance induction warrant further exploration.

Endo-borneol exhibits a dose-dependent pattern in enriching rhizosphere microbiota to induce resistance in P. ginseng against Alternaria infection. Rhizomicrobe-primed ISR has been reported to protect plants against various foliar pathogens (Pieterse et al., 2003; Noman et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023). Our study reveals that foliar spraying with endo-borneol can enrich beneficial microbiota to prime ISR, although higher concentrations result in more significant modifications to the beneficial microbiota in the rhizosphere. Based on the culturable microbial isolation and verification, it is evident that endo-borneol recruits microbes, including Trichoderma, Mortierella, Novosphingobium, Nocardiodes, Burkholderia, and Pseudomonas—all known to be beneficial to plants and trigger ISR in P. ginseng against Alternaria leaf spot. These microbiota have been recognized for their significant role in inducing plant responses against various stresses. Specifically, strains from Burkholderia, Pseudomonas, and Novosphingobium regulate the biosynthesis and signaling of abscisic acid (ABA) and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), priming defense mechanisms in plants against biotic and abiotic stresses (Vives-Peris et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020; Kong et al., 2022). Furthermore, salicylic acid and IAA secreted by Nocardioides spp., arachidonic acid produced by the Mortierella genus, as well as harzianolide and bioactive volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from Trichoderma spp., act as resistance elicitors to counteract pathogen infection (Cai et al., 2013; Dedyukhina et al., 2014; Jalali et al., 2017; Meena et al., 2020).

Endo-borneol enhances root secondary metabolism and secretion, thereby enriching the rhizosphere microbiota. Root exudates play a crucial role in recruiting specific microbes in response to biotic and abiotic stresses (Sharma et al., 2023). In this study, we observed a dose-dependent activation of secondary metabolic processes (specifically flavonoids, terpenoids, and phenylpropanoids) in both leaves and roots induced by endo-borneol, which subsequently enhanced the secretion of secondary metabolites into the soil. Notably, ginsenosides—major constituents upregulated by endo-borneol in the soil—significantly promoted the growth of Burkholderia, Nocardioides, Novosphingobium, Mortierella, and Pseudomonas in a dose-dependent manner. These results align with those presented by Luo et al. (2020), who indicated that soil microbes could utilize ginsenosides differently as carbon sources. Additionally, non-ginsenoside compounds such as oleic acid and eugenol, upregulated by endo-borneol, also promoted the growth of Burkholderia, Nocardioides, Novosphingobium, Mortierella, and Trichoderma. These non-ginsenoside compounds serve as favorable carbon sources for some microbes (Pantazaki et al., 2010; Kadakol and Kamanavalli, 2010). Overall, the metabolites increased by endo-borneol treatment proved beneficial for the growth of soil microbes. Regarding metabolites decreased after the endo-borneol treatment (such as 2-phenylacetamide,coumarin, phenylpyruvic acid, and matairesinol), their antimicrobial effects on the growth of tested microbes were substantially mitigated or even eliminated at lower concentrations. This observation aligns with findings that phenolic compounds (including conifer aldehyde, coniferyl alcohol, and ferulic acid) and coumarin inhibit bacterial and fungal growth in vitro (Daurade-Le Vagueresse et al., 2001; Figueiredo et al., 2008; Medina et al., 2011; Zou et al., 2021). These findings suggest that metabolites downregulated by endo-borneol tend to be innocuous or even beneficial to soil microbiota at relatively low concentrations. Therefore, endo-borneol can modify secondary metabolism, leading to the enrichment of beneficial microbes in the rhizosphere soil to prime ISR.

In conclusion, certain plant-derived compounds from one plant can directly enhance the resistance of neighboring plants and indirectly recruit associated beneficial microbiota by regulating the secretion of secondary metabolites to prime ISR. Notably, endo-borneol from P. koraiensis exhibits multifunctional properties and shows promise as an effective agent for reducing plant diseases within sustainable agricultural systems. Therefore, our study underscores the importance of interspecies allelopathic interactions in combating plant diseases and suggests that manipulating rhizosphere communities through foliar stimulation could effectively promote disease suppression.

Methods

Effects of P. koraiensis needle leachates on P. ginseng growth

A field experiment was conducted with P. ginseng on a farm under P. koraiensis forests (41°4′17″ N, 124°29′58″ E, 578 m altitude, 965.9 hPa) in Benxi, Liaoning Province, China. The experiment assessed the effects of needle leachate leaf sprays in mitigating Alternaria leaf spot on 2-year-old and 4-year-old P. ginseng plants from July to August, 2021. Fresh needles of P. koraiensis were randomly collected, and every 150 g of them were soaked in 1000 ml of sterilized water for 48 h at room temperature. The solution was subsequently filtered twice using qualitative filter paper (9-cm diameter, Jiaojie, Fushun City, China) through suction filtration (Li et al., 2023). The resultant aqueous leachates, with a concentration of 150 g/l, were stored at 4°C for further use.

Sixty days post seedling emergence of P. ginseng (early July), the needle leachates were diluted to concentrations of 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 25, and 50 g/l for leaf spraying. Each treatment was replicated six times, using 4 × 1.5-m plots arranged in a randomized complete block design. Throughout the growing season of P. ginseng, aqueous leachates were sprayed once a week, and all treatments were maintained under routine field agronomic management. Disease incidence and severity were recorded and assessed according to Guan et al. (2008) in late August. Subsequently, P. ginseng from each plot was sampled and analyzed in the laboratory to investigate underground agronomic traits.

Identification of needle leachates of P. koraiensis via GS–MS

The types and doses of allelochemicals released by plants into the environment are influenced by intrinsic plant factors and environmental conditions, including biotic and abiotic stresses (Zhang et al., 2018). In this study, aqueous extracts obtained from the fresh needles of P. koraiensis were monitored and analyzed monthly during the growing season of P. ginseng (from May to September), with three replicates performed each month. The procedures for preparing needle leachates from P. koraiensis are detailed in the section “effects of P. koraiensis needle leachates on P. ginseng growth.” A volume of 100 ml of leachates was extracted with 300 ml of ethyl acetate (analytical grade, Tianjin Fengchuan Chemical Reagent, Tianjin, China) and then concentrated using a roary evaporator (R-200, BÜCHI, Flawil, Switzerland) at 45°C, with condensed water being recycled at 4°C in a low-temperature circulator (CCA-1112A, Tokyo Rikakikai, Tokyo, Japan). The residue was dissolved in 2.5 ml of hexane (high-performance liquid chromatography grade, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and filtered through a 0.22-μm Millipore filter (cartridge filter, Jin Teng, China) for GC–MS analysis (GCMS-QP2010 Ultra, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

The GC–MS instrument and techniques used to identify the components of P. koraiensis needle leachates followed the protocols outlined by Ye et al. (2021) using full scan mode. The constituents of the leachates were identified using the GC–MS Solutions software (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) by comparing their mass spectra with those in the NIST14 and NIST14s libraries (Supplemental Table 7). Compounds were selected for further analysis if they had a similarity to library standards higher than 80%, a monthly detection rate of at least 60%, and a peak area percentage greater than 0.01% (Supplemental Figure 2A). Endo-borneol was selected for further investigation from the identified compounds due to its high similarity with the library standards (97%), substantial percentage of peak area (≥ 1%), and consistent monthly detection rate (100%) (Supplemental Figure 2).

A standard endo-borneol sample (95%, Sichuan Weikeqi Biological Technology, Sichuan, China) was used to confirm the identity of endo-borneol in the needle leachates by matching the mass spectra and RT using GC–MS/MS and GC–MS. The GC–MS methods and instruments used for verification were the same as those used for initial compound identification in the needle leachates. For the GC–MS/MS analysis, an Agilent 7890 Gas Chromatograph (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) equipped with a 19091S-433UI HP-5MS Ultra Inert column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Agilent, Santa Clara, USA), and an Agilent 5975 mass spectrometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) were used. Helium gas (99.999% purity) was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1 ml/min. The temperature program was set to start at 40°C, increasing by 15 °C/min to 125°C, followed by a 5 °C/min increase to 210°C, a 10°C/min increase to 270°C, and a 20°C/min increase to 305°C, which was held for 5 min. The interface temperature between GC and MS was maintained at 270°C. The ionization source utilized positive ion electron ionization at 70 eV. The temperatures of the ion source and quadrupole were maintained at 240°C and 160°C, respectively. Mass spectra were recorded across the mass range of 50–600 m/z, with a scanning rate of 1562 u/s. The raw GC–MS/MS data were analyzed using MassHunter Qualitative Analysis B.08.00 software (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) to compare the endo-borneol in the needle leachates with the standard.

Quantification of endo-borneol by indoor simulated rainfall via GC–MS

The detection of endo-borneol in leachates from tree canopies to the forest floor was investigated. Endo-borneol from in situ leachates, which flushed from the tree canopy to the forest floor by natural precipitation, did not reach the detection limit of GC–MS. Indoor simulated leaching was carried out, with modifications based on methods from Zheng et al. (2012). Meteorological data on monthly precipitation from May to October for the years 2016 to 2021 were obtained from the local weather bureau in Benxi. Based on these historical meteorological data, monthly precipitation levels were categorized as low (34.6 mm, 771.63 min), medium (104.2 mm, 2223.07 min), and high (285.8 mm, 5233.03 min). To determine the representative weight of fresh needles per unit area in the forest of P. koraiensis, the tree canopy within a 1 m2 area was trimmed, and the fresh needles collected from five random points were weighed. The average weight (3980.58 g/m2) was established as the representative weight for fresh needles per square meter. For the simulation, 84.03 g of fresh needles was evenly distributed over two layers of absorbent gauze (specification: 22C, Kunming Kangye Medical Devices, Kunming, China) and secured at the top of a 5-l vessel (16.4-cm inside diameter), which was placed on the ground and filled with a specific volume of double-distilled water to mimic the graded monthly precipitation. A peristaltic pump with a constant flow rate of 3770 ml/min was used to percolate water through the packed fresh needle surface. The resulting leachates were filtered twice using qualitative filter paper (9-cm diameter, Jiaojie, Fushun, China) through suction filtration (Li et al., 2023) and subsequently stored at 4°C for quantification.

The extracted graded leachates were processed using the same methods as described in the section “identification of needle leachates of P. koraiensis via GS-MS.” After rotary evaporation, the remaining sediment was dissolved in 5 ml of ethyl acetate (high-performance liquid chromatography grade, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). This solution was then filtered through a 0.22-μm Millipore filter (cartridge filter, Jin Teng, China) for analysis. A series of endo-borneol concentrations in ethyl acetate was prepared to establish a standard curve (Supplemental Table 8). Quantification of endo-borneol was carried out using an Agilent 8860 GC/5977B MSD (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) equipped with an HP-5MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) in selected ion monitoring mode. Parameter settings for the GC/MSD and the total ion chromatogram (TIC) of the endo-borneol standard, with an RT at 7.454 min, are detailed in Supplemental Figure 3. The concentrations of endo-borneol in both the simulated rainfall and in the field were calculated based on the known injection concentrations (Supplemental Table 2).

Effects of leachates and endo-borneol on pathogen growth

The antifungal activities of leachates and endo-borneol were assessed following methodologies from previous research (De Araujo and Roussos, 2002; Li et al., 2023). The antifungal effects of leachates against A. panax were tested at concentrations of 0, 0.1, 1, 10, 25, and 50 g/l. Similarly, the antifungal activity of endo-borneol against A. panax was evaluated at concentrations of 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, and 1000 mg/l. Endo-borneol was dissolved in 60% ethanol to prepare stock solutions. The final concentration of ethanol in the tested PDA medium was limited to 0.6% (vol/vol), a level determined not to inhibit the mycelial growth of A. panax in a preliminary test. This ethanol concentration was consistently used in all endo-borneol-based antifungal tests. For the assay, a mycelium block (5 mm in diameter) was placed at the center of each Petri dish, which had been prepared with designated concentrations of the test solutions in PDA. Control plates contained mycelium blocks grown on PDA with only distilled water. Five replicates were analyzed for each concentration. After 7 days of incubation at 25°C in darkness, colony diameters were measured (Li et al., 2023), and inhibition rates were calculated according to the method described by Shafi et al. (2004).

In addition to colony diameter measurements, an in vitro antifungal test of endo-borneol on the mycelial biomass of A. panax was conducted following the method described in Darwesh and Elshahawy (2021) with minor modifications. Briefly, three 5-mm mycelium disks from A. panax cultures were placed in a 250 ml flask containing 100 ml of potato dextrose broth, supplemented with various concentrations of sterilized endo-borneol. The flasks were incubated on a rotary shaker at 25°C ± 2°C for 6 days, after which the mycelium was filtered and oven-dried at 60°C until a constant weight was achieved. Then, dry biomass of the mycelium was recorded, and the corresponding inhibition rate was calculated.

Effects of endo-borneol foliar spray on the growth of P. ginseng

Endo-borneol leaf sprays were administered at seven concentrations: 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 50, and 100 mg/l. The plot arrangement, application method, and timing of these sprays were consistent with those used for the needle leachate sprays described in the section “effects of P. koraiensis needle leachates on P. ginseng growth.” The disease incidence and severity of Alternaria leaf spot, along with the agronomic traits of P. ginseng, were assessed using the methods outlined in the same section. For each treatment, six replicates were obtained by sampling healthy 4-year-old P. ginseng plants from each plot. Rhizosphere soil was collected following the methods described by Luo et al. (2022). The collected rhizosphere soil samples were divided into two parts: approximately 10 g from each replicate were snap-frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for subsequent metabolism and microbial community analysis. The remaining rhizosphere soil samples were stored at 4°C for the isolation and identification of culturable microorganisms, as well as for examining their functions.

Analysis of. community structure and functionality of soil rhizosphere microbes

Microbial functional analysis

The effective concentrations of endo-borneol for inducing resistance and promoting biomass accumulation in P. ginseng were identified as 0.1 mg/l and 100 mg/l. Subsequently, rhizosphere soils from the 0.1- and 100-mg/l treatments were divided into two portions: one sterilized and one left unsterilized to assess the function of rhizosphere microorganisms under each condition. Additionally, forest soil not used for P. ginseng cultivation was sterilized via dry heat at 180°C for 4 h and used as the background soil (Liang et al., 2016). Both sterilized and unsterilized rhizosphere soils were mixed with the background soil at a 1:9 (w/w) ratio (Mendes et al., 2011) and designated as sterilized and unsterilized soils for the 0.1 mg/l and 100 mg/l treatments, respectively. The mixed soils for each treatment were then placed in pots (diameter, 11.6 cm; height, 10.5 cm) in four replicates, with each replicate consisting of 10 pots. Seeds of P. ginseng were sterilized according to the method described by Li et al. (2023). Eight seeds were sown in each pot and cultivated to evaluate seedling survival rates and plant biomass over the following year.

Microbial community analysis

For soil microbial community analysis, genomic DNA was extracted from soil samples using the E.Z.N.A. soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The bacterial 16S rRNA gene V3–V4 regions were amplified from the extracted soil DNA using primers 338F and 806R, and the fungal ITS regions were amplified using primers ITS1F and ITS2R, following the procedures described in Liu et al. (2024). Paired-end reads were merged using FLASH (v.1.2.7), and raw reads were processed and analyzed to remove low-quality sequences using fastp (v.0.19.6) (Tanja and Steven, 2011; Chen et al., 2018). The high-quality sequences were then clustered into OTUs at 97% sequence similarity using UPARSE 7.1 (Stackebrandt and Goebel, 1994; Edgar, 2013). The most abundant sequence from each OTU was selected as the representative sequence. The taxonomy of each representative OTU sequence was determined using RDP Classifier version 2.2 (Wang et al., 2007) against the 16S rRNA gene database (Silva v138) with a confidence threshold of 0.7.

Isolation and resistance assessment of soil rhizosphere microbes

This study identified potential culturable microorganisms in the rhizosphere soil modified by foliar sprays of endo-borneol. Bacteria and fungi were isolated using nutrient agar (NA) and potato dextrose agar (PDA) media, respectively, as described by Luo et al. (2019). The isolated and purified culturable fungi and bacteria were identified based on their morphology and using ITS or 16S rDNA protocols, respectively (Claesson et al., 2010; Tedersoo and Lindahl, 2016). The potential of these microbial strains to induce plant defense against Alternaria leaf spot in P. ginseng was assessed. Two-year-old P. ginseng seedlings were transplanted into pots (10 plants per pot). Target bacterial suspensions were prepared at concentrations of 106, 107, and 108 CFU/ml for each strain, while fungal spore suspensions were diluted to 105, 106, and 107 spores/ml (Haidar et al., 2021; Saengchan et al., 2022). For each strain, 50 ml of suspension was added to the pots for soil inoculation, whereas control pots received 50 ml of sterilized water. After inoculation, all pots were enclosed in clear plastic bags to prevent soil contamination by A. panax. After 24 h, each seedling was inoculated with A. panax mycelium disks (4 mm in diameter) and incubated following the method described by Li et al. (2023). When symptoms of Alternaria leaf spot appeared, the lesion areas on leaves infected with A. panax were scanned using a scanner (600 dpi resolution; Epson Perfection V19, Japan) and analyzed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, USA).

De novo leaf and root transcriptome analysis

Two-year-old P. ginseng seedlings were transplanted into pots (six plants/pot) to evaluate gene expression levels in leaves and roots from plants that received endo-borneol leaf sprays. To ensure that the endo-borneol was applied only to the leaves and not to the soil, the pots were wrapped with plastic bags. Each treatment consisted of four replicates, with six pots per replicate, and was placed in a plastic storage box. Endo-borneol solutions of 0, 0.1, and 100 mg/l were sprayed onto the leaves to the dripping point once daily (Li et al., 2023). After three days of treatment, leaves were sampled from half of the pots, and clean fibrous roots were sampled from the other half. All samples were immediately immersed in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis. The effects of endo-borneol on the resistance of Panax (P. quinquefolius and P. notoginseng) and Solanum (S. lycopersicum) plants against Alternaria infection were assessed following the same treatment. Once disease symptoms appeared, the lesion areas on infected leaves were calculated following the method in the section “isolation and resistance assessment of soil rhizosphere microbe.”

We then performed high-throughput RNA sequencing and de novo assembly of the transcriptome for all samples. RNA extraction and sequencing were carried out according to Wang et al. (2022) by MetWare (Wuhan, China) on an Illumina sequencing platform. Trinity (Grabherr et al., 2011) was used to assemble all trimmed clean reads. The assembled unigenes were annotated against KEGG and GO databases for functional analysis. Expression levels of the unigenes were quantified using the fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads method (Mortazavi et al., 2008). Statistical enrichment of genes in KEGG pathways and GO terms was analyzed using ClusterProfiler R software (Yu et al., 2012). After filtering out genes with unchanged or low-expression levels from the samples, a total of 36 395 genes from the transcriptome data were used for the weighted gene co-expression network analysis module using fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads values.

Analysis and evaluation of Rhizosphere soil metabolism and its impact on beneficial microorganisms

The metabolism of rhizosphere soil was assessed using LC–MS/MS with six biological replicates for each treatment at endo-borneol concentrations of 0.1 and 100 mg/l, following the non-targeted metabolomics method described by Kong et al. (2022). The LC–MS/MS analyses were conducted on a Thermo UHPLC-Q Exactive HF-X system equipped with an ACQUITY HSS T3 column (100 × 2.1 mm; internal diameter 1.8 μm; Waters, USA) at Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology (Shanghai, China). Mobile phases, sample injection volumes, flow rates, and column temperatures were set as specified in Kong et al. (2022). LC-MS/MS raw data were preprocessed using Progenesis QI software (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA) and exported in CSV format (Supplemental Table 9). Metabolites were categorized based on their involvement in biochemical pathways via metabolic enrichment and pathway analysis, referencing the KEGG database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/).

Metabolites associated with significant KEGG pathways were selected to assess their impacts on the growth of beneficial microorganisms identified in the section “analysis of community structure and functionality of soil rhizosphere microbes.” The effects of the metabolites on bacterial growth were evaluated according to the method of Deng et al. (2023), with some modifications. Briefly, bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth to the log phase and collected by centrifugation. The optical density at 600 nm was adjusted to 0.4 with sterilized water. Each metabolite was added to 1/10 LB medium to achieve the indicated final concentrations (0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 μg/ml) in a 96-well plate with an equivalent amount of 0.1% methanol serving as a blank control. After incubation (28°C, 48 h) on a shaker at 180 rpm, the optical density at 600 nm was recorded using a spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Four replicates were set for each treatment. The methods for evaluating the effects of metabolites on fungi are referenced from the section “effects of leachates and endo-borneol on pathogen growth.”

Statistical analysis

Data analysis and graphing were performed using SPSS 22.0 software (SPSS, USA), Gephi version 0.10.1 (Bastian et al., 2009), and hiplot (https://hiplot.cn). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test (homogeneity of variances, Levene’s test, p > 0.05), Tamhane’s T2 test (homogeneity of variances, Levene’s test, p < 0.05), t-tests, and correlation analysis with the Pearson correlation coefficient were utilized for data analysis.

Data and code availability

The raw transcriptome data have been uploaded to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database (accession numbers: SRP487467, PRJNA1071309). The raw sequencing reads of bacteria and fungi have also been deposited into the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database (accession number: SRP486992, PRJNA1071274). The raw MS data for the identification of needle leachates (study ID: ST003309), endo-borneol quantification (study ID: ST003310), and rhizosphere soil metabolomics (study ID: ST003307) were deposited at the Metabolomics Workbench (https://www.metabolomicsworkbench.org/) (Sud et al., 2016).

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (U23A20202, 32202400), the Major Science and Technology Project of Kunming (2021JH002), and the Yunnan Provincial Key Laboratory Special Fund (202005AG070146). We are grateful for the support from Metabolomics Workbench, which provided a platform for uploading raw data and is funded by NIH grants U2C-DK119886 and OT2-OD030544.

Acknowledgments

No conflict of interest is declared.

Author contributions

S.Z. and Y.Z. designed the research. M.Y., H.H., Y.L., and X.H. assisted with experimental design. W.L. and W.K. supported X.-Y.J. in conducting the experiments. X.-Y.J. and S.Z. performed data analysis, visual plotting, and manuscript writing. C.Y. revised the manuscript. W.S. and L.S. provided assistance with field experiments in Liaoning Province.

Published: October 15, 2024

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and CEMPS, CAS.

Supplemental information is available at Plant Communications Online.

Contributor Information

Huichuan Huang, Email: huanghc@ynau.edu.cn.

Youyong Zhu, Email: yyzhu@ynau.edu.cn.

Shusheng Zhu, Email: sszhu@ynau.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

References

- Aerts N., Pereira Mendes M., Van Wees S.C.M. Multiple levels of crosstalk in hormone networks regulating plant defense. Plant J. 2021;105:489–504. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ain Q., Mushtaq W., Shadab M., Siddiqui M.B. Allelopathy: an alternative tool for sustainable agriculture. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 2023;29:495–511. doi: 10.1007/s12298-023-01305-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslam F., Khaliq A., Matloob A., Tanveer A., Hussain S., Zahir Z.A. Allelopathy in agro-ecosystems: a critical review of wheat allelopathy-concepts and implications. Chemoecology. 2017;27:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s00049-016-0225-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bachheti A., Sharma A., Bachheti R.K., Husen A., Pandey D.P. In: Co-Evolution of Secondary Metabolites. Mérillon J.M., Ramawat K.G., editors. Springer; Berlin: 2020. Plant allelochemicals and their various applications. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin I.T., Halitschke R., Paschold A., Von Dahl C.C., Preston C.A. Volatile signaling in plant-plant interactions: "talking trees" in the genomics era. Science. 2006;311:812–815. doi: 10.1126/science.1118446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian M., Heymann S., Jacomy M. Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. Proceedings of ICWSM. 2009;3:361–362. doi: 10.1609/icwsm.v3i1.13937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai F., Yu G., Wang P., Wei Z., Fu L., Shen Q., Chen W. Harzianolide, a novel plant growth regulator and systemic resistance elicitor from Trichoderma harzianum. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013;73:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Balan P., Popovich D.G. Ginsenosides analysis of New Zealand–grown forest Panax ginseng by LC-QTOF-MS/MS. J. Ginseng Res. 2020;44:552–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Zhou Y., Chen Y., Gu J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.J., Zheng Y.Q., Kong C.H., Zhang S.Z., Li J., Liu X.G. 2, 4-Dihydroxy-7-methoxy-1, 4-benzoxazin-3-one (DIMBOA) and 6-methoxy-benzoxazolin-2-one (MBOA) levels in the wheat rhizosphere and their effect on the soil microbial community structure. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:12710–12716. doi: 10.1021/jf1032608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomel M., Baldy V., Guittonny M., Greff S., DesRochers A. Litter leachates have stronger impact than leaf litter on Folsomia candida fitness. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020;147 doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2020.107850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Claesson M.J., Wang Q., O'Sullivan O., Greene-Diniz R., Cole J.R., Ross R.P., O'Toole P.W. Comparison of two next-generation sequencing technologies for resolving highly complex microbiota composition using tandem variable 16S rRNA gene regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e200. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daurade-Le Vagueresse M.H., Romiti C., Grosclaude C., Bounias M. Coevolutionary toxicity as suggested by differential coniferyl alcohol inhibition of ceratocystis species growth. Toxicon. 2001;39:203–208. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwesh O.M., Elshahawy I.E. Silver nanoparticles inactivate sclerotial formation in controlling white rot disease in onion and garlic caused by the soil borne fungus Stromatinia cepivora. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2021;160:917–934. doi: 10.1007/s10658-021-02296-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dedyukhina E.G., Kamzolova S.V., Vainshtein M.B. Arachidonic acid as an elicitor of the plant defense response to phytopathogens. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2014;1:18. doi: 10.1186/s40538-014-0018-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Araujo A.A., Roussos S. A technique for mycelial development of ectomycorrhizal fungi on agar media. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2002;98:311–318. doi: 10.1385/ABAB:98-100:1-9:311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruijn W.J.C., Gruppen H., Vincken J.P. Structure and biosynthesis of benzoxazinoids: Plant defence metabolites with potential as antimicrobial scaffolds. Phytochemistry. 2018;155:233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yop G.d.S., Gair L.H.V., da Silva V.S., Machado A.C.Z., Santiago D.C., Tomaz J.P. Abscisic acid is involved in the resistance response of Arabidopsis thaliana against Meloidogyne paranaensis. Plant Dis. 2023;107:2778–2783. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-22-1726-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L., Luo L., Li Y., Wang L., Zhang J., Zi B., Ye C., Liu Y., Huang H., Mei X., et al. Autotoxic ginsenoside stress induces changes in root exudates to recruit the beneficial Burkholderia strain B36 as revealed by transcriptomic and metabolomic approaches. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023;71:4536–4549. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c00311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doornbos R.F., van Loon L.C., Bakker P.A.H.M. Impact of root exudates and plant defense signaling on bacterial communities in the rhizosphere. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012;32:227–243. doi: 10.1007/s13593-011-0028-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R.C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:996–998. doi: 10.1038/NMETH.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrmann J., Ritz K. Plant: soil interactions in temperate multi-cropping production systems. Plant Soil. 2014;376:1–29. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1921-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez C., Monnier Y., Santonja M., Gallet C., Weston L.A., Prévosto B., Bousquet-Mélou A., Baldy V., Bousquet-Mélou A. The impact of competition and allelopathy on the trade-off between plant defense and growth in two contrasting tree species. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:594. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo A.R., Campos F., de Freitas V., Hogg T., Couto J.A. Effect of phenolic aldehydes and flavonoids on growth and inactivation of Oenococcus oeni and Lactobacillus hilgardii. Food Microbiol. 2008;25:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahukar R.T. Evaluation of plant-derived products against pests and diseases of medicinal plants: a review. Crop Protect. 2012;42:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2012.07.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y.M., Wu L.J., Pang S.F., Li G., Liu T.H. Fungicide activity of three kinds of novel fungicides in controlling Alternaria panax Whetz. and efficacy in field. Special Wild Econ. Anim. Plant Res. 2008;30:47–49. doi: 10.16720/j.cnki.tcyj.2008.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C., Yang M., Jiang B., Ye C., Luo L., Liu Y., Huang H., Mei X., Zhu Y., Deng W., et al. Moisture controls the suppression of Panax notoginseng root rot disease by indigenous bacterial communities. mSystems. 2022;7 doi: 10.1128/MSYSTEMS.00418-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr M.G., Haas B.J., Yassour M., Levin J.Z., Thompson D.A., Amit I., Adiconis X., Fan L., Raychowdhury R., Zeng Q., et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal P.S., Lewis E.E., Venkatachari S. Allelopathy: a possible mechanism of suppression of plant-parasitic nematodes by entomopathogenic nematodes. Nematology. 1999;1:735–743. doi: 10.1163/156854199508766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haidar R., Yacoub A., Roudet J., Fermaud M., Rey P. Application methods and modes of action of Pantoea agglomerans and Paenibacillus sp., to control the grapevine trunk disease-pathogen, Neofusicoccum parvum. Oeno one. 2021;55:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jalali F., Zafari D., Salari H. Volatile organic compounds of some Trichoderma spp. increase growth and induce salt tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Fungal Ecol. 2017;29:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.funeco.2017.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Q., Kong D., Li Q., Sun S., Song J., Zhu Y., Liang K., Ke Q., Lin W., Huang J. The function of inositol phosphatases in plant tolerance to abiotic stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:3999. doi: 10.3390/ijms20163999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing S.Q., Jiang H.P., Liu F.Y., Dou D.Q. Comparison of seven ginsenoside contents in Shengshaishen Hongshen and Linxiashen. Chinese Arch. Tra. Chinese Medi. 2009;27:207–209. doi: 10.13193/j.archtcm.2009.01.209.jingshq.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadakol J.C., Kamanavalli C.M. Biodegradation of eugenol by Bacillus cereus strain PN24. J. Chem. 2010;7:S474–S480. doi: 10.1155/2010/364637. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong H.G., Song G.C., Ryu C.M. Inheritance of seed and rhizosphere microbial communities through plant–soil feedback and soil memory. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2019;11:479–486. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong P., Li X., Gouker F., Hong C. cDNA transcriptome of Arabidopsis reveals various defense priming induced by a broad-spectrum biocontrol agent Burkholderia sp. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:3151. doi: 10.3390/IJMS23063151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuc J. Induced immunity to plant disease. Bioscience. 1982;32:854–860. doi: 10.2307/1309008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li T.Y., Ye C., Zhang Y.J., Zhang J.X., Yang M., He X.H., Mei X.Y., Liu Y.X., Zhu Y.Y., Huang H.C., Zhu S.S. 2, 3-Butanediol from the leachates of pine needles induces the resistance of Panax notoginseng to the leaf pathogen Alternaria panax. Plant Divers. 2023;45:104–116. doi: 10.1016/j.pld.2022.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z., Li L., Wan F., Liu W. Feedback of soil biota on Ageratina adenophora growth and competitiveness with native plant: a comparison of different sterilization methods. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2016;24:1223–1230. doi: 10.13930/j.cnki.cjea.160040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P., Ding S., Liu N., Mo Y., Liang Y., Ma J. Effects of detritus treatments on soil microbial community composition, structure and nutrient limitation in a subtropical karst ecosystem. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024;24:3265–3281. doi: 10.1007/s42729-024-01750-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L.F., Yang L., Yan Z.X., Jiang B.B., Li S., Huang H.C., Liu Y.X., Zhu S.S., Yang M. Ginsenosides in root exudates of Panax notoginseng drive the change of soil microbiota through carbon source different utilization. Plant Soil. 2020;455:139–153. doi: 10.1007/s11104-020-04663-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L., Zhang J., Ye C., Li S., Duan S., Wang Z., Huang H., Liu Y., Deng W., Mei X., et al. Foliar pathogen infection manipulates soil health through root exudate-modified rhizosphere microbiome. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022;10 doi: 10.1128/SPECTRUM.02418-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L., Guo C., Wang L., Zhang J., Deng L., Luo K., Huang H., Liu Y., Mei X., Zhu S., Yang M. Negative plant-soil feedback driven by re-assemblage of the rhizosphere microbiome with the growth of Panax notoginseng. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1597. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meena K.K., Bitla U.M., Sorty A.M., Singh D.P., Gupta V.K., Wakchaure G.C., Kumar S. Mitigation of salinity stress in wheat seedlings due to the application of phytohormone-rich culture filtrate extract of methylotrophic actinobacterium Nocardioides sp. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:2091. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.02091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina A., Jakobsen I., Egsgaard H. Sugar beet waste and its component ferulic acid inhibits external mycelium of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011;43:1456–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.03.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes R., Kruijt M., De Bruijn I., Dekkers E., Van Der Voort M., Schneider J.H.M., Piceno Y.M., DeSantis T.Z., Andersen G.L., Bakker P.A.H.M., Raaijmakers J.M. Deciphering the rhizosphere microbiome for disease-suppressive bacteria. Science. 2011;332:1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1203980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A., Williams B.A., Mccue K., Schaeffer L., Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noman M., Ahmed T., Ijaz U., Shahid M., Li D., Li D., Manzoor I., Song F. Plant–Microbiome crosstalk: Dawning from composition and assembly of microbial community to improvement of disease resilience in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:6852. doi: 10.3390/ijms22136852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen C.C., Nguyen T.Q.C., Kanaori K., Binh T.D., Dao X.H.T., Vang L.V., Kamei K. Antifungal activities of Ageratum conyzoides L. extract against rice pathogens Pyricularia oryzae Cavara and Rhizoctonia solani Kühn. Agriculture. 2021;11:1169. doi: 10.3390/AGRICULTURE11111169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazaki A.A., Dimopoulou M.I., Simou O.M., Pritsa A.A. Sunflower seed oil and oleic acid utilization for the production of rhamnolipids by Thermus thermophilus HB8. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;88:939–951. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2802-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse C.M., van Pelt J.A., Verhagen B.W., Ton J., van Wees S.C., Léon-Kloosterziel K.M., Van Loon L.C. Induced systemic resistance by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Symbiosis. 2003;35:39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ratnadass A., Fernandes P., Avelino J., Habib R. Plant species diversity for sustainable management of crop pests and diseases in agroecosystems: a review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012;32:273–303. doi: 10.1007/s13593-011-0022-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riedlmeier M., Ghirardo A., Wenig M., Knappe C., Koch K., Georgii E., Dey S., Parker J.E., Schnitzler J.P., Vlot A.C. Monoterpenes support systemic acquired resistance within and between plants. Plant Cell. 2017;29:1440–1459. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saengchan C., Sangpueak R., Le Thanh T., Phansak P., Buensanteai N. Induced resistance against Fusarium solani root rot disease in cassava plant (Manihot esculenta Crantz) promoted by salicylic acid and Bacillus subtilis. Acta Agric. Scand., Sect. B. 2022;72:516–526. doi: 10.1080/09064710.2021.2018033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shafi P.M., Nambiar M.G., Clery R.A., Sarma Y.R., Veena S.S. Composition and antifungal activity of the oil of Artemisia nilagirica (Clarke) Pamp. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2004;16:377–379. doi: 10.1080/10412905.2004.9698748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma I., Kashyap S., Agarwala N. Biotic stress-induced changes in root exudation confer plant stress tolerance by altering rhizospheric microbial community. Front. Plant Sci. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/FPLS.2023.1132824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi K., Shao H. Changes in the Soil Fungal Community Mediated by a Peganum harmala Allelochemical. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.911836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stackebrandt E., Goebel B.M. Taxonomic note: A place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1994;44:846–849. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-4-846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sud M., Fahy E., Cotter D., Azam K., Vadivelu I., Burant C., Edison A., Fiehn O., Higashi R., Nair K.S., et al. Metabolomics Workbench: An international repository for metabolomics data and metadata, metabolite standards, protocols, tutorials and training, and analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:463–470. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanja M., Steven S. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedersoo L., Lindahl B. Fungal identification biases in microbiome projects. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2016;8:774–779. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholl D., Lee S. Terpene specialized metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Arabidopsis Book. 2011;9:e0143. doi: 10.1199/tab.0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S.S., Yajima W.R., Rahman M.H., Shah S., Liu J.J., Ekramoddoullah A.K.M., Kav N.N.V. A cysteine-rich antimicrobial peptide from Pinus monticola (PmAMP1) confers resistance to multiple fungal pathogens in canola (Brassica napus) Plant Mol. Biol. 2012;79:61–74. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9895-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vives-Peris V., Gómez-Cadenas A., Pérez-Clemente R.M. Salt stress alleviation in citrus plants by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria Pseudomonas putida and Novosphingobium sp. Plant Cell Rep. 2018;37:1557–1569. doi: 10.1007/s00299-018-2328-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Schaewen A., Frank J., Koiwa H. Role of complex N-glycans in plant stress tolerance. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008;3:871–873. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.10.6227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters D.R., Fountaine J.M. Practical application of induced resistance to plant diseases: an appraisal of effectiveness under field conditions. J. Agric. Sci. 2009;147:523–535. doi: 10.1017/S0021859609008806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walters D.R., Ratsep J., Havis N.D. Controlling crop diseases using induced resistance: challenges for the future. J. Exp. Bot. 2013;64:1263–1280. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Garrity G.M., Tiedje J.M., Cole J.R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Du Z., Yang X., Wang L., Xia K., Chen Z. An integrated analysis of metabolomics and transcriptomics reveals significant differences in floral scents and related gene expression between two varieties of Dendrobium loddigesii. Appl. Sci. 2022;12:1262. doi: 10.3390/APP12031262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Wang H.L., Tang R.P., Sun M.Y., Chen T.M., Duan X.C., Lu X.F., Liu D., Shi X.C., Laborda P., et al. Pseudomonas putida represses JA-and SA-mediated defense pathways in rice and promotes an alternative defense mechanism possibly through ABA signaling. Plants. 2020;9:1641. doi: 10.3390/PLANTS9121641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Wang X., Xue C. Effect of cinnamic acid on soil microbial characteristics in the cucumber rhizosphere. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2009;45:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ejsobi.2009.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. Main practice and effects of Chinese herbal medicine planting under forest development in Xiji county. Moder. Agricul. Sci. and Tech. 2016;18:79. [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Zhang Y., Qi L., Mei X., Liao J., Ding X., Deng W., Fan L., He X., Vivanco J.M., et al. Plant-plant-microbe mechanisms involved in soil-borne disease suppression on a maize and pepper intercropping system. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye C., Fang H.Y., Liu H.J., Yang M., Zhu S.S. Current status of soil sickness research on Panax notoginseng in Yunnan, China. Allelopathy J. 2019;47:1–14. doi: 10.26651/allelo.j/2019-47-1-1216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye C., Liu Y., Zhang J., Li T., Zhang Y., Guo C., Yang M., He X., Zhu Y., Huang H., et al. α-Terpineol fumigation alleviates negative plant-soil feedbacks of Panax notoginseng via suppressing Ascomycota and enriching antagonistic bacteria. Phytopathol. Res. 2021;3:13–17. doi: 10.1186/s42483-021-00090-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G., Wang L.G., Han Y., He Q.Y. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16:284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.X., Gao Y., Zhao Y.J. Study on allelopathy of three species of Pinus in North China. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2018;16:6409–6417. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S.A., Zheng X., Chen C. Leaching behavior of heavy metals and transformation of their speciation in polluted soil receiving simulated acid rain. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Jia H., Ge X., Wu F. Effects of vanillin on the community structures and abundances of Fusarium and Trichoderma spp. in cucumber seedling rhizosphere. J. Plant Interact. 2018;13:45–50. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2017.1414322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.L., Liu X.Y., Zhou C., Han S.F., Xu F.R., Dong X. Root-Associated Microbiomes of Panax notoginseng under the Combined Effect of Plant Development and Alpinia officinarum Hance Essential Oil. Molecules. 2022;27:6014. doi: 10.3390/molecules27186014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J., Liu Y., Guo R., Tang Y., Shi Z., Zhang M., Wu W., Chen Y., Hou K. An in vitro coumarin-antibiotic combination treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2021;16 doi: 10.1177/1934578X20987744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement