Abstract

Probiotics have been proposed as a potential strategy for managing ulcerative colitis (UC). However, the underlying mechanisms mediating microbiota-host crosstalk remain largely elusive. Here, we report that Limosilactobacillus reuteri (L. reuteri), as a probiotic, secretes cytoplasmic membrane vesicles (CMVs) that communicate with host cells, alter host physiology, and alleviate dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis. First, L. reuteri-CMVs selectively promoted the proliferation of the beneficial bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila (AKK) by upregulating the expression of glycosidases (beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase and alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase) involved in glycan degradation and metabolic pathways and restored the disrupted gut microbiota balance. Second, L. reuteri-CMVs were taken up by intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), elevated the expression of ZO-1, E-cadherin (Cdh1), and Occludin (Ocln), decreased intestinal permeability, and exerted protective effects on epithelial tight junction functionality. RNA sequencing analysis demonstrated that L. reuteri-CMVs repaired intestinal barrier by activating the HIF-1 signaling pathway and upregulating HMOX1 expression. Third, L. reuteri-CMVs increased the population of double positive (DP) CD4+CD8+ T cells in the intestinal epithelial layer, suppressing gut inflammation and maintaining gut mucosal homeostasis. Finally, L. reuteri-CMVs exhibited satisfactory stability and safety in the gastrointestinal tract and specifically targeted the desired sites in colitis mice. Collectively, these findings shed light on how L. reuteri interact with the host in colitis, and provide new insights into potential strategies for alleviating colitis.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12951-025-03158-8.

Keywords: Limosilactobacillus reuteri, Cytoplasmic membrane vesicles, Gut microbiota, Intestinal barrier, Double positive CD4+CD8+ T cells, Colitis

Introduction

The human gastrointestinal tract contains a vast and diverse microbiome, which plays a vital role in digestion, pathogen resistance, human diseases, and health [1]. The gut microbiota contributes to maintaining systemic homeostasis by mediating microbe-microbe and microbe-host communication [1]. Recently, accumulated studies have found that alterations or dysbiosis of the gut microbiota are associated with a plethora of intestinal and extraintestinal diseases, such as intestinal bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and several kinds of cancer [1–3]. For example, multi-omics analyses of the gut microbial ecosystem have revealed that IBD, a prototypic inflammatory intestinal disease, is linked with changes in gut microbiome composition, characterized by a decrease in obligate anaerobes such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia hominis, as well as an increase in facultative anaerobes like Escherichia coli [4]. Additionally, the gut microbiota involved in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer has been identified, including Fusobacterium nucleatum, Escherichia coli, and Bacteroides fragilis, which directly damage host DNA and contribute to tumor progression [3]. In a nutshell, the modulation and maintenance of the gut microbiota is generally shaped by novel therapeutic approaches.

In recent years, probiotics have garnered significant attention as potential interventions for restoring gut microbiota homeostasis and as promising alternatives in the management of IBD. For instance, fecal microbiota transplantation is an effective intervention strategy for patients with recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections and IBD [5, 6]. However, the clinical application of probiotics remains hampered by several limitations. The gastrointestinal harsh milieu—comprising gastric acid, bile, and digestive enzymes—compromises the stability and viability of probiotics. This often limits their persistence in the intestinal environment following oral administration, thereby reducing their sustained therapeutic effects. Additionally, prolonged use of a single or restricted set of probiotic strains may induce immune tolerance, diminishing their clinical efficacy over time. This tolerance may also increase susceptibility to opportunistic infections and exacerbate intestinal injury through disrupting the integrity of the intestinal barrier. Moreover, the lack of a comprehensive understanding of the precise mechanisms by which probiotics exert their beneficial effects in IBD further complicates the development of more effective and durable probiotic-based therapies. Such gaps in mechanistic knowledge present a significant challenge to advancing probiotics as a reliable and long-term treatment option for IBD [7].

Recent years have seen remarkable interest in bacterial extracellular vesicles (EVs) as an emerging promising postbiotic. There is a large body of evidence that bacterial EVs derived from parental microbiota are crucial in the underlying mechanisms behind the initiation and progression of host diseases. This is because the gastrointestinal epithelial layer constitutes a physical and biochemical barrier that limits the translocation of gut microbes and direct interactions between gut microbes and the host [8–10]. Bacterial EVs released from the cell surface into the extracellular environment, are composed of bi-layered membrane nanostructures ranging from 20 nm to 400 nm in size [11]. These EVs consist of two primary subtypes: cytoplasmic membrane vesicles (CMVs) produced by Gram-positive bacteria and outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) secreted by Gram-negative bacteria [12]. Importantly, bacterial EVs contain various parental bioactive components, including proteins, lipids, DNA, and RNA, which can bypass the gastrointestinal epithelial barrier, directly communicate with host cells, and exert different biological functions [12]. For example, Porphyromonas gingivalis, a key periodontal pathogen, releases OMVs can enter endothelial cells and inhibit levels of endothelial intercellular junction proteins, contributing to an increase in endothelial permeability and risk for cardiovascular diseases [13]. Fusobacterium nucleatum-secreted OMVs can selectively target intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), promote immune cell infiltration, deplete the mucus layer, and increase levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-8 (IL-8) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), thereby inducing intestinal inflammation in mice [14]. Conversely, Clostridium butyricum-derived CMVs protect the intestinal barrier and maintain gut microbiota homeostasis, which contribute to alleviating dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced mice colitis [15]. In summary, more attention is paid to bacterial EVs as potential targets for clinical diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

Limosilactobacillus reuteri (L. reuteri), a Gram-positive bacterium, predominantly colonizes the gastrointestinal tract of healthy individuals and adheres to the intestinal epithelium to regulate the intestinal immune system [16]. It is known that L. reuteri exerts multifaceted roles in maintaining the gut microbiota and intestinal barrier function, increasing beneficial metabolites, protecting against oxidative stress, and decreasing microbial translocation from the intestinal lumen to the host by producing antimicrobial molecules and promoting the functionality of regulatory T cells [17, 18]. Impressively, significant research has highlighted the promising potential of using L. reuteri as a novel therapeutic modality for patients with IBD, whereas the mechanisms remain undeciphered [19]. We have previously discovered that Portulaca oleracea L-derived exosome-like nanoparticles promote L. reuteri growth and mitigate DSS-induced colitis [20]. However, the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. L. reuteri-CMVs with potential to overcome the limitations of traditional probiotics have attracted tremendous research interest in its application to treating colitis. Consequently, this study is initiated to explore whether L. reuteri-CMVs exert protective effects on colitis and elucidate their underlying mechanisms of action. We found that L. reuteri-CMVs effectively navigated the complex gastrointestinal environment, preserving their stability and specifically targeting the colitis-affected regions. Notably, L. reuteri-CMVs contributed to maintain gut microbiota homeostasis, protect the intestinal barrier, and regulate immune responses in DSS-induced colitis, while exhibiting a favorable safety profile. Furthermore, we demonstrated that L. reuteri-CMVs promoted intestinal barrier function by activating the HIF-1 signaling pathway and upregulating the expression of HMOX1.

Materials and methods

L. reuteri strain culture

L. reuteri (BNCC192190) was purchased from the BeNa Culture Collection (BNCC), and cultured in MRS broth (Huankai) at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions. For oral gavage, L. reuteri was harvested at the logarithmic phase by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in PBS to reach a density of 1*109 colony forming units (CFUs)/mL.

L. reuteri-CMVs isolation, purification, and physicochemical characterization

In an anaerobic chamber, a single colony of L. reuteri after grown on MRS Agar Plate for 24 h was collected and inoculated into MRS broth (Huankai) at 37 ◦C for 12 h. The culture was then refreshed by a 1:100 dilution in fresh MRS broth and incubated at 37 °C for about 16 h until the OD600 reached 1. After centrifugation at 15,000g for 30 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm polyvinylidene fluoride filter (Millipore) and concentrated approximately 20-fold using 50 kDa ultra centrifugal filters (Millipore). The supernatant was again filtered with a 0.22 μm filter (Millipore), and then CMVs were collected by ultracentrifugation at 150,000 g for 3 h at 4 °C (Ultracentrifuge Optima™ XE-100 with a Type 70 Ti rotor, Beckmann Coulter, USA). The pellet was finally resuspended in PBS and filtered aseptically through a 0.22 μm filter to remove intact bacteria or cell debris. The filtrate was collected and stored at -80 °C for further use. The protein concentration of CMVs was quantified using the BCA protein assay kit (EpiZyme). The morphology of CMVs was visualized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (HT7700 electron microscope), and the size of CMVs was analyzed using dynamic light scattering (DLS, Zetasizer Nano AS90) according to our previous study [20].

Lipidomic analysis of L. reuteri-CMVs and proteomic profiles of L. reuteri-CMVs and L. reuteri

Lipidomic composition analysis of L. reuteri-CMVs was investigated based on our previous study [20]. The proteins in L. reuteri-CMVs and L. reuteri were extracted and separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Protein lysates were prepared and subjected to nano-LC-MS/MS analysis to identify and quantify their proteins using Orbitrap mass spectrometry (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany).

Cell culture

HT-29 and Caco2 human intestinal epithelial cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). HT-29 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco™) containing 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 mg/ml). Caco-2 cells were cultivated in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) (Gibco™) supplemented with 20% FBS, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 mg/ml). All cells were grown at 37 °C in an incubator with 5% CO2.

Stimulation of IECs in vitro

Upon reaching 70% confluence in complete media, HT-29 or Caco2 cells were stimulated with 2% DSS (MP Biomedicals) and hrTNF (PeproTech, 10 ng/ml) for 24 h. Cells were harvested for further experiments as described below.

L. reuteri-CMVs labeling

To enable flurescent tracking, L. reuteri-CMVs were labeled using two distinct dyes: IRDye 800CW near-infrared fluorescent dye (IRDye® 800CW NHS Ester) and Dil dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The IRDye 800CW labeling was performed as described previously [20]. Briefly, a 0.21-mM solution of fluorescent IRDye 800CW was added to 1 mg of L. reuteri-CMVs in 1 ml of PBS. Then, the mixture was incubated with a 0.2-M sodium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.3) for 2 h at room temperature. To remove unbound dye, the labeled CMVs were purified using a 100 kDa ultra centrifugal filter (Millipore). For Dil labeling, 5 µl of Dil (1 mM) was added to 1 mL of CMVs, mixed thoroughly, and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The Dil-labeled CMVs were similarly purified using a 100 kDa ultra centrifugal filter (Millipore) to remove any unbound dye. Both IRDye 800CW-labeled and Dil-labeled CMVs were resuspended in PBS and stored for further experiments.

L. reuteri-CMVs stability

The stability of IRDye® 800CW-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs was investigated based on our previous study [20]. IRDye® 800CW-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs were incubated in stomach-like solution or intestine-like solution at 37 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, the IRDye® 800CW-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs were collected through exosome spin columns with a molecular weight cutoff of 4,000 (MW4000).

Depletion of L. reuteri in mice

In order to deplete the gut commensal L. reuteri, C57BL/6 mice were treated with a cocktail containing vancomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, 0.5 g/L) and ampicillin (Sigma-Aldrich, 1 g/L) in drinking water for 7 days. The abundance of L. reuteri was regularly detected in fresh stool samples by qRT-PCR.

Animals and housing

C57BL/6 and IL-10-deficient (IL-10−/−) mice were purchased from Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China and Gempharmatech CO., Ltd, Jiangsu, China, respectively. All mice were housed in a germ-free environment with a 12-hour light/dark cycle. At 8 weeks of age, they were used for experiments according to the guidelines and regulations of the Animal Care Committee of Shenzhen People’s Hospital, Shenzhen, China (No. 2024 − 118). All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Efficacy of L. reuteri-CMVs in treating DSS-induced colitis

All mice were given 3% DSS in drinking water continuously for 6–7 days to induce colitis as described previously [20, 21]. The intervention was performed for 6–7 consecutive days, starting on day 1 of the DSS treatment. C57BL/6 mice were divided into four groups: healthy control group, PBS group, L. reuteri group, and CMVs group. IL-10−/− mice were divided into three groups: healthy control group, PBS group, and CMVs group. Mice depleted of L. reuteri were divided into three groups: PBS group, L. reuteri group, and CMVs group. The colitis mice were fed daily with either 1*109 CFUs/ml of L. reuteri (200 µl of bacterial suspension), 200 µl of PBS containing CMVs (2.5 mg/ml), or 200 µl of PBS as a control.

The body weight, fecal characteristics, and physical activity of the mice were assessed daily throughout the experiment. The disease activity index (DAI) was calculated using a previously established scoring system [20, 21]. On days 6 or 7, the mice were euthanized using CO2 inhalation. Blood samples were obtained from the orbits of the mice for further use. The colon length was measured from the cecum to the rectum. Colon samples, feces, and major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) were harvested for further experiments.

Biodistribution and uptake of L. reuteri-CMVs in the gastrointestinal tract

To assess the biodistribution of L. reuteri-CMVs in the gastrointestinal tract, colitis mice and untreated mice were gavaged with 200 µl of PBS containing IRDye® 800CW-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs (2.5 mg/ml). At various time points after oral administration (4, 12, and 24 h), the mice were euthanized using CO2 inhalation. Intestine tissues and major organs (brain, heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) were then obtained for fluorescence imaging through an IVIS spectrum imaging system (Hopkinton, USA), which allows for visualization and quantification of the fluorescence emitted by the IRDye® 800CW-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs in these tissues.

In order to investigate the uptake of L. reuteri-CMVs in the gastrointestinal tract, colitis mice were administered 200 µl of Dil-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs (2.5 mg/ml) by oral gavage. The stomach, small intestine, and colon were harvested 8 h post-administration. The tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h at 4 °C. Subsequently, the tissues were immersed in PBS containing 30% sucrose for 48 h at 4 °C until they bottomed out. The tissues were then buried in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT), frozen, and sectioned into 5 μm slices. The frozen slices were cleaned with PBS, blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and subsequently incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. Following 3 washes with PBS, the slices were incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the nuclei were stained using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Beyotime). Images were acquired using a fluorescence scanner (Pannoramic MIDI, 3DHISTECH, Hungary).

Cell uptake of L. reuteri-CMVs

A volume of 10 µl Dil-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs (2.5 mg/ml) was incubated with Caco-2 and HT-29 cells for 8 h at 37 °C, respectively. After incubation, the cells were washed three times with PBS and stained with DAPI. The uptake of L. reuteri-CMVs was then visualized by a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) (ZEISS LSM 900, Germany).

Biosafety of L. reuteri-CMVs in vitro and in vivo

In vitro, the MTT assay was used to assess the cytotoxicity of L. reuteri-CMVs on Caco-2 and HT-29 cells. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1*104 cells/well and incubated for 24 h. Cells were then incubated with 100 µl of complete medium with L. reuteri-CMVs for 24 and 48 h. After the medium containing CMVs was removed, the cells were thoroughly rinsed once with PBS and incubated with 100 µl of MTT (5 mg/ml) for 3 h at 37 °C. Finally, the media were discarded and 100 µl of dimethylsulfoxide was added to each well prior to spectrophotometric reading at 490 nm. Untreated cells were defined as negative controls.

In vivo, blood samples were collected for the detection of creatine kinase isoenzymes (CK-MB), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), serum creatinine (CREA), and serum urea (UREA) after colitis mice were treated with L. reuteri-CMVs for 7 days. The healthy mice and untreated colitis mice were controls. In addition, heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney samples were harvested and performed to evaluate the toxicity of the L. reuteri-CMVs using hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining.

H&E and alcian blue (AB) staining

Briefly, the colon tissues were fixed in a 4% polyformaldehyde solution. Then, they were dehydrated in an ethanol gradient, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Subsequently, they were cut into 5 μm-thick slices for H&E and AB staining. Histological scores were estimated as previously described [22]. Goblet cell counts were performed by calculating the number of AB-stain positive cells in each crypt (≥ 6 crypts per mouse were examined) [23].

FITC-dextran permeability assay

FITC-dextran (Sigma-Aldrich, 0.6 mg/g) was administered orally to mice for 12 h without eating or drinking. Serum samples were collected 4 h after the administration of the FITC-dextran. The FITC fluorescence intensity of the serum was measured using a multimode reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at an excitation wavelength of 490 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm.

Gut microbiota 16 S rRNA sequencing

Briefly, the HiPure Stool DNA Kit from Magen (Guangzhou, China) was used to extract total fecal DNA based on the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA quality and concentration were scrutinized using agarose gel electrophoresis and a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer, respectively. The v3-v4 regions of the 16 S rRNA gene were amplified using primers: 341 F: CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG and 806R: GGACTACHVGGGTATCTAAT. Sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq PE250 platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA). Sequencing data processing and bioinformatics analysis were performed using the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform (Guangzhou Genedenovo Bio-Technology Company Limited, Guangzhou, China).

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells and colon tissues using the TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The concentration of RNA was detected using the NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Gene expression was performed using the PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara). Primers were designed and obtained in Supplement 1.

Enzymelinked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and IL-10 were determined in serum samples using ELISA kits (Elabscience) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

For IHC analysis, colon sections were put in 0.01 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and high-pressure treated for 3 min for antigen repair. The sections were then blocked by 5% BSA for 30 min and underwent subsequent incubation with a myeloperoxidase (MPO) primary antibody (Abcam, ab208070, 1:200) overnight at 4 °C. The sections were then incubated with an appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h, and the immunoreactivity was detected using a DAB substrate kit.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

Cells and colon sections were fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and blocked with 3% BSA. They were then incubated with primary antibodies (anti-ZO-1 (Invitrogen, 33-9100, 1:200), anti-Occludin (Ocln) (Abcam, ab216327, 1: 100), anti-Mucin2 (Muc2) (Servicebio, GB11344, 1:1000), anti-E-cadherin (Cdh1) (Servicebio, GB12083, 1:1000), anti-CD4 (Servicebio, GB15064-100, 1:200), anti-CD8 (Servicebio, GB15068-100, 1:400), and anti-HMOX1 (Proteintech, 66743-1-Ig, 1:200)) at appropriate dilutions overnight at 4 °C. Following the removal of the primary antibodies, samples were then washed with PBS and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Abcam) and/or Alexa Fluor 555 (Abcam) at room temperature for 1 h. Finally, the nuclei were stained with DAPI. The images were acquired by a fluorescence scanner and CLSM.

Western blot analysis

Cells or colon tissue were lysed on ice for 30 min using RIPA lysis buffer (EpiZyme) containing a phosphatase inhibitor (EpiZyme). Protein concentration was measured using the BCA protein assay kit (EpiZyme). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (EpiZyme) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Sigma-Aldrich). Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with various primary antibodies at appropriate concentrations: ZO-1 (Invitrogen, 33-9100, 1:400), Ocln (Abcam, ab216327, 1:1000), Cdh1 (CST, 3195T, 1:000), and HMOX1 (Proteintech, 66743-1-Ig, 1:2000) with β-actin (Proteintech, 66009-1-Ig, 1:50000) serving as a control. Membranes were then treated with secondary antibodies (mouse secondary antibody (Affinity, S0002), rabbit secondary antibody (Affinity, S0001)) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the results were imaged by a Bio-Rad Imaging System.

Growth curve experiment of bacteria and bacterial uptake of L. reuteri-CMVs

Akkermansia muciniphila (AKK) (BNCC341917) was purchased from the BNCC and cultured in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth supplemented with Threonineat (6 g/L) and N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) (4.4 g/L) under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C. Subsequently, AKK cultures were supplemented with 10 µl of PBS containing L. reuteri-CMVs (2.5 mg/ml), and untreated AKK was defined as a control. Optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured every 4 h at 37 °C using a NanoDrop 2000 to monitor bacterial growth and calculate the total number of bacterial cells.

To assess bacterial uptake, 1 ml of logarithmic phase AKK solution was co-cultured with 10 µl of PBS containing Dil-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs (2.5 mg/ml). The mixture was centrifuged at 7,000 g for 5 min after 24 h. The collected samples were washed three times with PBS to remove unincorporated Dil-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs. The uptake of L. reuteri-CMVs by AKK was visualized using CLSM.

Bacterial RNA-sequencing analysis

Under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C, AKK was co-incubated with PBS or CMVs for 72 h. After incubation, bacterial pellets were harvested, and total RNA was extracted using a bacterial RNA extraction kit (TIANGEN). RNA sequencing libraries was prepared using the Fast RNA-seq Lib Prep Kit V2 (ABclonal, RK20306). Transcriptome sequencing was performed on the Illumina platform at Novogene Co.,Ltd. (Beijing, China). The clean reads were mapped to the reference AKK genome (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) using HISAT2 (v2.0.5). HTSeq (v0.9.1) was used to count the reads numbers mapped to each gene. Differential expression analysis of two groups was performed using the DESeq2 R package (v1.20.0). Genes with P adj < 0.05 and |log2(foldchange)| > 0 were identified as differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) were used for enrichment analysis of DEGs.

Cellular RNA-sequencing analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, the amount and quantity of mRNA were evaluated using a Nanodrop 2000. RNA-seq libraries were prepared, sequenced, and analyzed on the Illumina sequencing platform by Guangzhou Genedenovo Bio-Technology Company Limited (Guangzhou, China). Reads obtained from the sequencing machines were further filtered by fastp (v0.18.0). Short reads alignment tool Bowtie2 (v2.2.8) was used for mapping reads to ribosome RNA (rRNA) database. An index of the reference genome was built, and paired-end clean reads were mapped to the reference genome using HISAT2 (v2.1.0). Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed with R package gmodels (http://www.r-project.org/) in this experience. Correlation analysis was performed by R. RNAs differential expression analysis was performed by DESeq2 software between two different groups. The genes with the parameter of false discovery rate (FDR) below 0.05 and absolute fold change > 1.5 were considered DEGs. Consequence, gene expression heat map, volcano plot, GO analysis, and KEGG pathway analysis of these DEGs were performed. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed to identify the significant enrichment of gene sets in relevant pathways.

Availability and analysis of transcriptomic datasets

Single-cell datasets were available at http://scibd.cn24. The relative expression of HMOX1 was evaluated in epithelial cell subsets.

Statistical analysis

A comparison of multiple experimental groups was carried out by one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A t-test was calculated to compare the means of the two groups. Data are presented as means ± SEM. The p < 0.05*, p < 0.01**, p < 0.001***, and p < 0.0001**** represent statistically significance, and ns represents non-significance.

Results

Isolation and identification of CMVs released by L. reuteri

The 16 S rRNA sequence analysis showed that the L. reuteri in this study matched L. reuteri strain 149 with 99.53% identity based on the information available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (Supplement 1). Then, L. reuteri-CMVs were obtained through bacterial reproduction, centrifugation, and purification procedures. TEM displayed that L. reuteri-CMVs were spherical with a lipid bilayer structure (Figure S1A). And, nanoparticle tracking analysis displayed that their size ranged from 100 nm to 486 nm (Figure S1B). Zeta potential measurements showed that L. reuteri-CMVs exhibited a negative zeta potential of -3 mV (Figure S1C). Meanwhile, L. reuteri-CMVs were subjected to incubation in different aqueous solutions simulating stomach-like and intestine-like solutions to assess their stability in the gastrointestinal tract. Changes in their size were evaluated, which revealed virtually no change in the size heterogeneity of L. reuteri-CMVs incubated in both stomach-like and intestine-like solutions compared to PBS incubation (Figure S1D). These findings demonstrate that L. reuteri-CMVs can maintain their integrity and resist digestion during gastrointestinal transport. Similarly, IRDye® 800CW-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs retained their fluorescence signals without attenuation after incubation in these solutions, further confirming their stability (Figure S1E). The lipidomic analysis indicated that L. reuteri-CMVs were primarily comprised of diacylglycerol (DG, 30.39%), sphingolipids (SPH, 19.13%), wax esters (WE, 18.65%), and monoglyceride (MG, 15.89%) (Figure S1F). The protein composition profiles showed that a total of 182 proteins and 247 proteins were identified in L. reuteri-CMVs and L. reuteri, respectively. Moreover, there were 178 common proteins between L. reuteri-CMVs and L. reuteri, which indicated that L. reuteri-CMVs originated from the parental L. reuteri cells (Figure S1G). Figure S1H showed the top 43 proteins in both L. reuteri-CMVs and L. reuteri.

L. reuteri-CMVs have similar effects as L. reuteri in the retardation of DSS-induced colitis

To explore whether L. reuteri-CMVs exert protective effects in DSS-induced colitis, C57BL/6 mice were randomized into four groups: healthy control group, PBS group, L. reuteri group, and CMVs group. The mice were gavaged daily with PBS, L. reuteri or L. reuteri-CMVs coupled with 3% DSS in drinking water for 7 days (Figure S2A). The body weight was continually increased in the healthy control group during the entire experiment, whereas it was markedly decreased in the PBS group. Interestingly, L. reuteri or L. reuteri-CMVs treatment strikingly attenuated DSS-induced body weight loss, with similar efficacy between the L. reuteri and CMVs groups (Figure S2B). Consistently, L. reuteri or L. reuteri-CMVs administration dramatically alleviated the colon length shortening (Figure S2D and S2E) and prevented the DAI increase (Figure S2C) in DSS-induced colitis. Histological analyses further demonstrated that L. reuteri or L. reuteri-CMVs attenuated pathological damage and reduced inflammatory cell infiltration compared to the PBS group (Figure S2F and S2G). These results reveal that L. reuteri-CMVs possess protective effects in DSS-induced colitis.

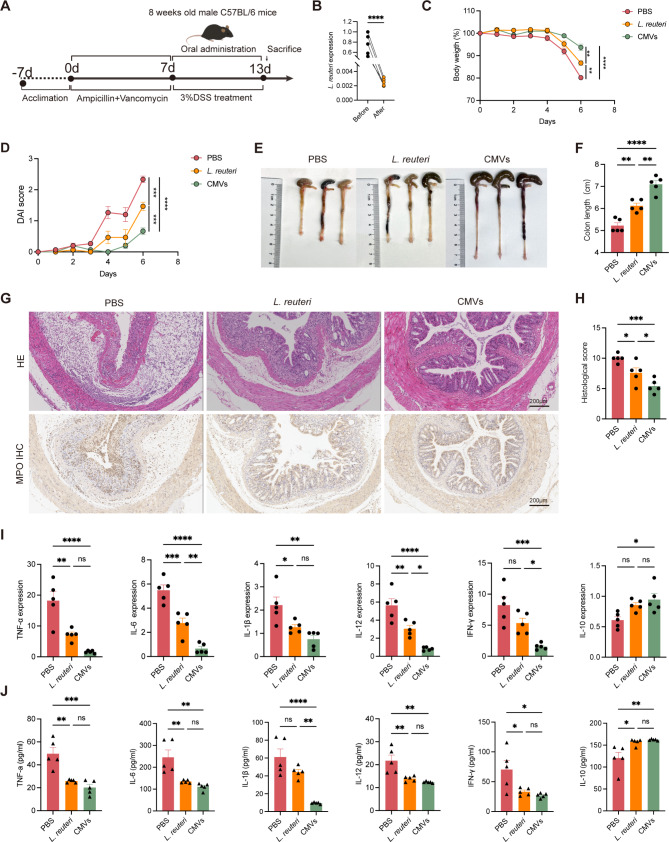

L. reuteri-CMVs alleviate DSS-induced colitis

To further assess the therapeutic effects of L. reuteri-CMVs in colitis, C57BL/6 mice were randomized into three groups: healthy control group, PBS group, and CMVs group. The colitis mice were treated daily with L. reuteri-CMVs or PBS for 7 days (Fig. 1A). L. reuteri-CMVs treatment prominently alleviated DSS-induced body weight loss (Fig. 1B) and markedly decreased DAI compared with the PBS group (Fig. 1C). Consistently, colon length shortening was significantly attenuated (Fig. 1D and E) and histological analyses showed reduced pathological damage and inflammatory cell infiltration in L. reuteri-CMVs administration in comparison with the PBS group (Fig. 1F and G). It is known that the induction of proinflammatory cytokines exerts a causative role in DSS-induced colitis. As expected, qRT-PCR and ELISA results showed that the mRNA and protein levels of colon tissue pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-12, and IFN-γ were significantly increased in the PBS group but were markedly reduced in the CMVs group. On the contrary, IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, was dramatically increased in the CMVs group compared with the PBS group (Fig. 1H and I).

Fig. 1.

L. reuteri-CMVs alleviate dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis. (A) Schematic diagram for the treatment of DSS-induced C57BL/6 colitis mice. (B) Daily body weight over 7 days. (C) Disease activity index (DAI) scores. (D) Photographs of colons. (E) Colon length. (F) H&E and myeloperoxidase (MPO) IHC staining for colons. (G) Histological scores. (H) The mRNA expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-12, and IFN-γ) and anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-10) in colons. (I) The concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-12, and IFN-γ) and anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-10) in the serum quantified by the ELISA method. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; ns, non-significance

It is known that IL-10−/− mice exhibit increased spontaneous susceptibility to colitis [24]. For this reason, we further examined the effect of L. reuteri-CMVs in this mouse model. The intervention approach in IL-10−/− colitis mice is depicted in Figure S3A. Impressively, orally administrated L. reuteri-CMVs also exerted protective effects in terms of body weight loss, colon length shortening, and DAI increase (Figure S3B-S3E), as well as attenuation of pathological damage and inflammatory cell infiltration in colon tissues (Figure S3F and S3G). Additionally, L. reuteri-CMVs treatment also decreased the mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-12, and IFN-γ in the colon tissues of DSS-induced IL-10−/− colitis mice (Figure S3H).

L. reuteri-CMVs mitigate DSS-induced colitis in L. reuteri-depleted mice

Inspired by these results, we further investigated the potential of L. reuteri-CMVs in treating DSS-induced colitis in L. reuteri-depleted mice. L. reuteri depletion was achieved through a 7-day treatment regimen with vancomycin and ampicillin, resulting in virtually undetectable levels of L. reuteri in fresh feces (Fig. 2B). Subsequently, the L. reuteri-depleted mice were treated daily with PBS, L. reuteri or L. reuteri-CMVs for 6 days (Fig. 2A). Impressively, both L. reuteri and L. reuteri-CMVs administration exerted decreased susceptibility of the L. reuteri-depleted mice to DSS. The body weight loss, colon length shortening, and DAI score increase were remarkably abolished compared with the PBS group (Fig. 2C-F). As expected, supplementation of L. reuteri and L. reuteri-CMVs inhibited colon histological damage and inflammatory cell infiltration (Fig. 2G and H). Consistently, orally administered L. reuteri or L. reuteri-CMVs not only suppressed levels of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, and IFN-γ, but also promoted levels of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (Fig. 2I and J). Interestingly, it has been found that L. reuteri-CMVs exhibited a more significant therapeutic effect than L. reuteri in the attenuation of DSS-induced colitis in L. reuteri-depleted mice (Fig. 2C-J).

Fig. 2.

L. reuteri-CMVs mitigate DSS-induced colitis in L. reuteri-depleted mice. (A) Schematic illustration for the administration regimen of DSS-induced colitis in L. reuteri-depleted C57BL/6 mice. (B) The mRNA expression levels of L. reuteri in mice treated with vancomycin plus ampicillin for 7 days. (C) Daily body weight over 6 days. (D) DAI scores. (E) Photographs of colons. (F) Colon length. (G) H&E and MPO IHC staining for colons. (H) Histological scores. (I) The mRNA expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-12, and IFN-γ) and anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-10) in colon tissues. (J) The concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-12, and IFN-γ) and anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-10) in the serum quantified by the ELISA method. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; ns, non-significance

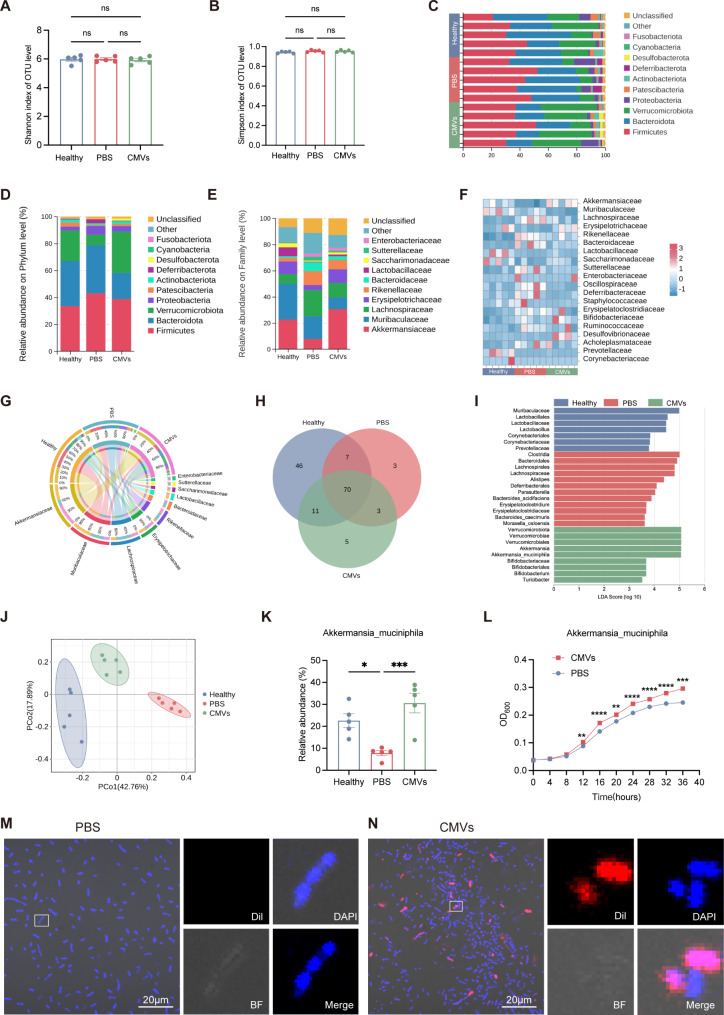

L. reuteri-CMVs restore gut microbiota dysbiosis in DSS-induced colitis

To investigate how L. reuteri-CMVs mitigate colitis, the impact of L. reuteri-CMVs on the gut microbiota was assessed in DSS-induced C57BL/6 colitis mice. Microbial composition analysis was performed in the healthy control group, PBS group, and CMVs group using 16 S rRNA sequencing. The abundance of the gut microbiota was assessed by calculating the number of OTUs. Shannon and Simpson indexes showed no significant differences between the healthy control group, PBS group, and CMVs group (Fig. 3A and B). This may be due to the fact that both L. reuteri-CMVs and DSS lead to changes in specific bacterial populations, resulting in insignificant changes in the species abundance of the three groups. The microbiome composition on the Phylum and Family levels was detailed across these groups in the heat map and bar charts (Fig. 3C-F). The relative proportions of beneficial bacteria, such as Akkermansiaceae, Lactobacillaceae and Sacharmonadaceae were prominently decreased in the PBS group but increased in the CMVs group, whereas harmful bacteria, such as Sutterellaceae, were drastically elevated in the PBS group but reduced in the CMVs group (Fig. 3E-G). The Venn diagram revealed that the PBS group had a decreased diversity of the gut microbiota compared with the healthy control group and CMVs group (Fig. 3H). Furthermore, linear discriminant analysis (LDA) demonstrated that the abundance taxa of the gut microbiota in each group were significantly different. The dominant bacterial communities in the PBS group were harmful bacteria, such as Clostridia and Lachnospirales, whereas the dominant bacterial communities in the healthy control group and CMVs group were beneficial bacteria, such as Muribaculaceae and Lactobacillales in the healthy control group, and Verrucomicrobiota and Bifidobacteriaceae in the CMVs group (Fig. 3I). Principal Co-ordinates Analysis (PCoA) showed that there were significant differences in gut microbiota composition in the PBS group compared with that in the healthy control group and CMVs group, where the CMVs group was closer in composition to that of the healthy control group (Fig. 3J). The relative abundance of AKK in the PBS group had a distinct decrease in comparison with the healthy control group. Nevertheless, L. reuteri-CMVs treatment significantly enhanced the AKK abundance in the DSS-induced colitis mice (Fig. 3K). Additionally, L. reuteri-CMVs promoted the proliferation of AKK by OD600 measurements in vitro (Fig. 3L). To further determine whether L. reuteri-CMVs directly interacted with AKK, Dil-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs or PBS were co-incubated with AKK. Three-dimensional (3D) CLSM images revealed that L. reuteri-CMVs were internalized by AKK after coincubation, and localized within the bacterial internal nucleic acid regions (Fig. 3M and N), which may be the mechanism that promotes the growth and functions of AKK.

Fig. 3.

L. reuteri-CMVs restore gut microbiota dysbiosis in DSS-induced colitis. (A, B) 𝛼-diversity analysis by Shannon index and Simpson index. (C) Microbial composition analysis of different species on Phylum level. (D, E) Histograms of microbial community composition on Phylum and Family levels. (F) Community heatmap analysis on Family level. (G) Circos plot of the gut microbiota in different groups on Family level. (H) Venn diagram of the gut microbiota in different groups. (I) Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) for demonstrating dominant bacterial communities in different groups. (J) Principal Co-ordinates Analysis (PCoA) of the gut microbiota in different groups. (K) The relative abundance of Akkermansia_muciniphila (AKK) in different groups. (n = 5). (L) The growth curves of AKK in the PBS and CMVs groups measured by recording the OD value at 600 nm. (M, N) 3D CLSM images of AKK after incubation with PBS and Dil-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs. (n = 3). Data are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; ns, non-significance

Consequently, microbial composition analysis was also conducted in the PBS group, L. reuteri group, and CMVs group for DSS-induced colitis in L. reuteri-depleted mice using 16 S rRNA sequencing. There were no significant differences in Shannon and Simpson indexes among these groups (Figure S4A and S4B). However, the bar charts demonstrated that the composition of the gut microbiota significantly differed in these groups at the Phylum, Family, and Genus levels (Figure S4C-S4F). Circos plot and heat map showed that L. reuteri-CMVs treatment markedly enhanced the abundances of Akkermansiaceae and Bacteroidaceae (Figure S4G and S4H). And, there were significant differences in the abundance taxa of the gut microbiota among these groups. The dominant bacterial communities of the PBS group were primarily composed of harmful bacteria including Escherichia_Shigella and Klebsiella, while the dominant bacterial communities in the L. reuteri group and the CMVs group were beneficial bacteria including Bacteroides_Stercorirosoris and Bacteroides in the L. reuteri group, as well as Bacteroides_acidifaciens and Akkermansia_muciniphila in the CMVs group (Figure S4I). The Venn diagram demonstrated that L. reuteri-CMVs treatment led to an increased abundance of the gut microbiota compared to the PBS group and L. reuteri group (Figure S4J). PCoA revealed that the gut microbiota composition of the PBS group was significantly different compared with that of the CMVs group and L. reuteri group (Figure S4K). The relative abundance of AKK declined in the PBS group but was restored by L. reuteri-CMVs in the DSS-induced colitis in L. reuteri-depleted mice (Figure S4L).

Based on these promising results, we further investigated the mechanism underlying L. reuteri-CMVs in promoting the growth of AKK. RNA sequencing analysis was analyzed for AKK treated with L. reuteri-CMVs or PBS. PCA indicated that the gene composition of the two groups exhibited differences (Fig. 4A). The heatmap and volcano plot of the DEGs of the PBS group vs. the CMVs group shown in Fig. 4B and C displayed the 73 upregulated and 55 downregulated genes in the CMVs group compared with the PBS group. GO enrichment analysis revealed that the DEGs were significantly enriched in biological processes were highly associated with hydrolase activity, cellular component, metabolic and biosynthetic processes, and translation (Fig. 4D). In KEGG enrichment analysis, the role of CMVs were highly corelated with metabolic pathways, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites and amino acids, as well as glycan degradation (Fig. 4E). GSEA further emphasized the significant role of L. reuteri-CMVs treatment in modulating genes associated with the glycan degradation signaling pathway (Fig. 4F). The heatmap shown in Fig. 4G provided an integrative view of the specific gene alterations related to glycan degradation and metabolic pathways following CMVs and PBS treatment. Notably, the gene expression of beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase (GOZ73_RS02135) and alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase (GOZ73_RS06515) (hydrolases which hydrolyze specific sugar residues in glycosaminoglycans (such as GlcNAc), helping bacteria acquire nutrients) was increased in the CMVs group as compared with that in the PBS group (Fig. 4G), suggesting that glycan metabolism regulation plays a significant role in the AKK growth. To assess the functional relevance of this observation, we found that the growth of AKK was notably inhibited in the absence of GlcNAc in the medium (Fig. 4H). Additionally, qRT-PCR confirmed the significant upregulation of beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase and alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase gene expression in AKK treated with L. reuteri-CMVs (Fig. 4I).

Fig. 4.

The regulation mechanism of L. reuteri-CMVs promoting AKK proliferation. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) of the gene expression level (FPKM) in different samples between the PBS group and the CMVs group. (B, C) Heatmap and volcano plot analysis of the total differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the PBS-treated and CMVs-treated AKK. (D, E) Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis based on DEGs. (F) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) for genes associated with the other glycan degradation signaling pathway. (G) Heatmap of DEGs related to metabolic pathways and glycan degradation between in PBS and CMVs groups. (H) The growth curves of AKK between in different media measured by recording the OD value at 600 nm. (I) The mRNA expression levels of beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase and alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase in AKK between in PBS and CMVs groups. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001

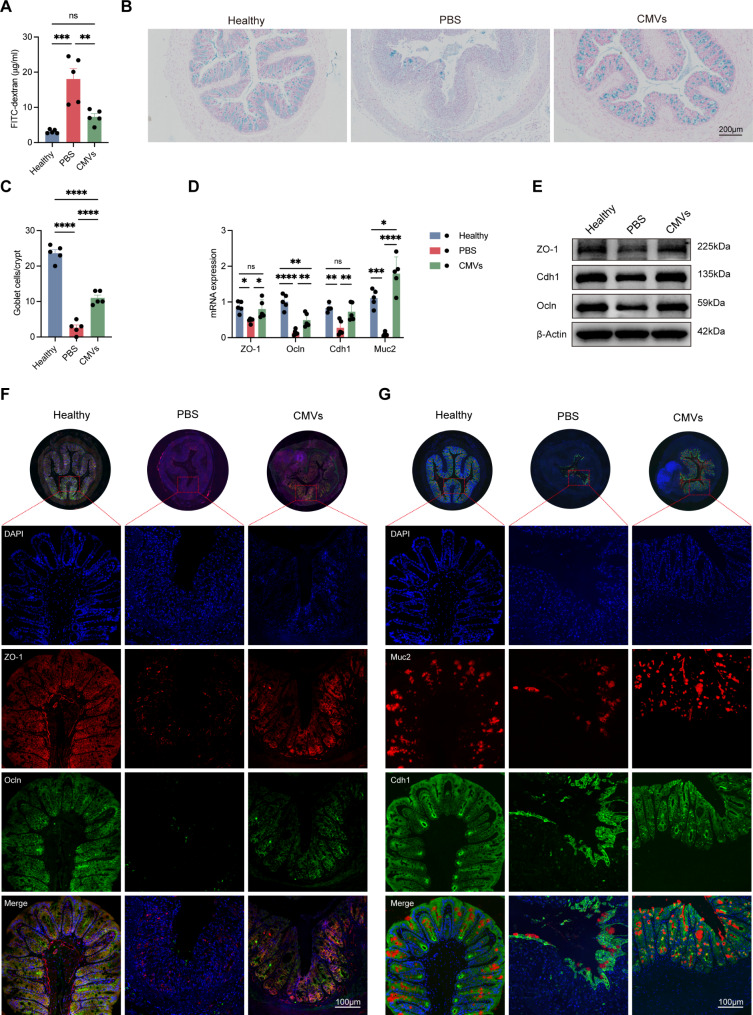

L. reuteri-CMVs repair intestinal barrier dysfunction in DSS-induced colitis

There is emerging evidence that intestinal barrier dysfunction is a crucial contributor to the colitis pathophysiology [25]. The intestinal barrier is mainly comprised of the secreted barrier and the cellular barrier [26]. The secreted barrier is primarily characterized by the mucin glycoprotein Muc2 synthesized by goblet cells, while the cellular barrier features tight junction proteins, such as ZO-1 and Ocln, secreted by IECs contributing to cell-cell tight junctions [27]. To elucidate the underlying mechanisms by which L. reuteri-CMVs alleviate colitis, their effects on the intestinal barrier function was assessed.

In DSS-induced C57BL/6 colitis mice, FITC-dextran assays showed that intestinal permeability was significantly increased in the DSS-induced colitis, which was reversed by L. reuteri-CMVs administration (Fig. 5A). Additionally, AB staining displayed a significant decrease in the number of goblet cells in the PBS group, whereas L. reuteri-CMVs treatment effectively inhibited goblet cell loss in the colon (Fig. 5B and C). Besides, the mRNA expression of ZO-1, Ocln, Cdh1, and Muc2 was significantly decreased in the PBS group but was restored by L. reuteri-CMVs treatment (Fig. 5D). Western blot analysis demonstrated that L. reuteri-CMVs upregulated the protein levels of ZO-1, Ocln, and Cdh1 (Fig. 5E). IF staining revealed that ZO-1, Ocln, Cdh1, and Muc2 protein levels were dramatically down-regulated in the colon samples of the DSS-induced colitis mice compared with those of the healthy control group. However, orally administered L. reuteri-CMVs to the DSS-induced colitis mice prominently alleviated the downregulation of these proteins in the colon samples (Fig. 5F and G).

Fig. 5.

L. reuteri-CMVs repair intestinal barrier dysfunction in DSS-induced colitis. (A) FITC-dextran levels in serum. (B) AB staining of goblet cells in colons. (C) The goblet cell count. (D) The mRNA expression levels of ZO-1, Occludin (Ocln), E-cadherin (Cdh1), and Mucin2 (Muc2). (E) Western blot analysis of ZO-1, Ocln, and Cdh1. (F, G) Immunofluorescence (IF) images of ZO-1, Ocln, Cdh1, and Muc2. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; ns, non-significance

Similarly, in DSS-induced colitis in L. reuteri-depleted mice, orally administered L. reuteri-CMVs also decreased intestinal permeability and increased the number of goblet cells per crypt in the colon (Figure S5A-S5C). Moreover, L. reuteri-CMVs treatment also promoted the expression of Muc2, ZO-1, Cdh1, and Ocln in the colon tissues of DSS-induced colitis in L. reuteri-depleted mice (Figure S5D-S5G).

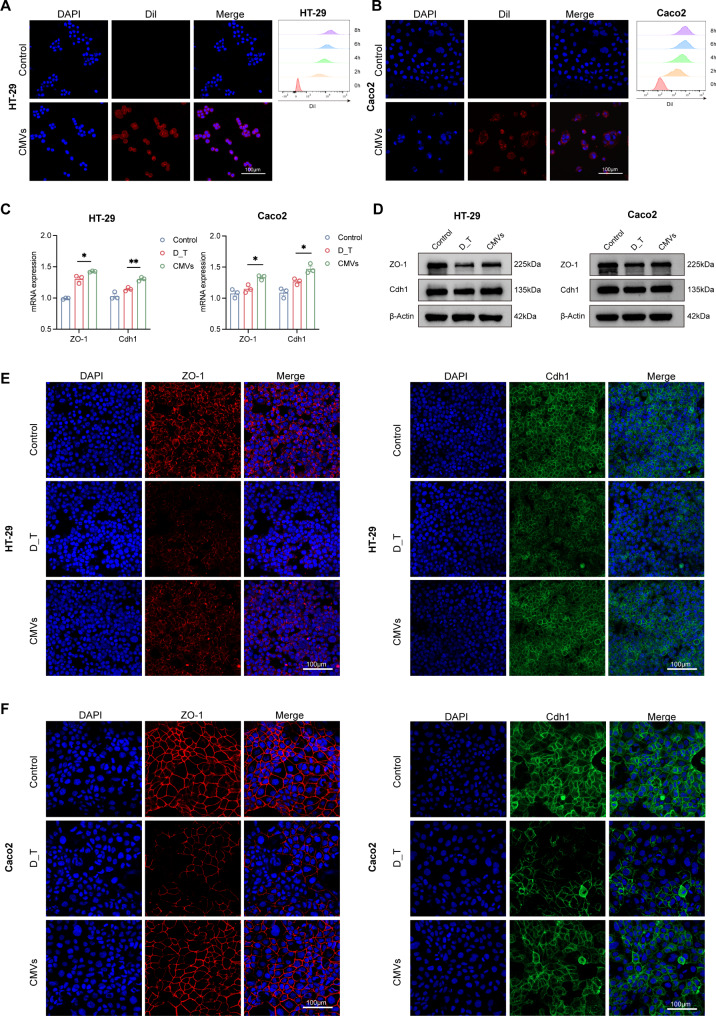

L. reuteri-CMVs are taken up by IECs and improve the tight junction protein expression of IECs

To further identify how L. reuteri-CMVs are directly associated with the IECs, the Dil-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs were co-incubated with Caco-2 and HT-29 cells. CLSM images showed that L. reuteri-CMVs were internalized by both Caco-2 and HT-29 cells and the fluorescence intensity of Dil in these cells increased with prolonged co-incubation time, indicating that L. reuteri-CMVs can be continuously internalized (Fig. 6A and B). In addition, L. reuteri-CMVs treated substantially enhanced mRNA and protein levels of ZO-1, Cdh1, as shown by qRT-PCR, western blot, and IF compared to the DSS_hrTNF-treated (D_T) lonely group in HT-29 and Caco-2 cells (Fig. 6C-F).

Fig. 6.

L. reuteri-CMVs promote tight junction proteins in vitro. (A, B) Dil-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs are internalized by HT-29 and Caco2 cells, and the Dil fluorescence intensity increased with prolonged co-incubation time. (C) The mRNA expression levels of ZO-1 and Cdh1 in HT-29 and Caco2 cells. (D-F) The protein levels of ZO-1 and Cdh1 in HT-29 and Caco2 cells using Western blot and IF analysis. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

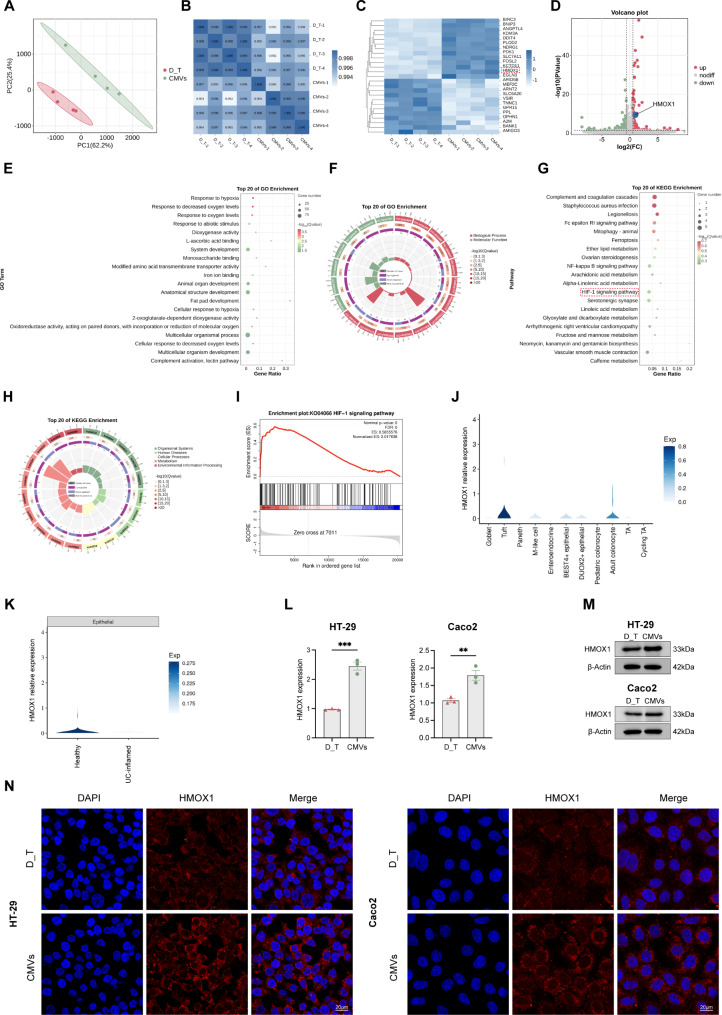

L. reuteri-CMVs promote intestinal barrier function by activating the HIF-1 signaling pathway in vitro

In order to explore the mechanism of L. reuteri-CMVs promoting the expression of tight junction proteins, RNA sequencing analysis was performed on D_T-treated HT-29 cells treated with L. reuteri-CMVs or PBS. PCA showed distinct transcriptional variations between the D_T group and CMVs group (Fig. 7A). Pearson correlation coefficient confirmed high repeatability among each sample (Fig. 7B). The heatmap and volcano plot analysis revealed that L. reuteri-CMVs treatment contributed to an upregulation of 73 genes and a downregulation of 128 genes compared to the D_T group, indicating significant alterations in gene expression (Fig. 7C and D) (p < 0.05 and fold change > 1.5). GO enrichment analysis showed that DEGs were mainly involved in response to hypoxia, system development, anatomical structure development, and multicellular organismal processes (Fig. 7E and F). KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that DEGs were mainly enriched in complement and coagulation cascades, HIF-1 signaling pathway, and vascular smooth muscle contraction (Fig. 7G and H). GSEA further highlighted the critical role of L. reuteri-CMVs treatment in the regulation of genes involved in the HIF-1 signaling pathway (Fig. 7I).

Fig. 7.

RNA-seq analysis of L. reuteri-CMVs treating DSS_hrTNF-treated (D_T) epithelial cell line HT-29. (A) PCA showing distinct transcriptional variations in the D_T group and the CMVs group. (n = 4). (B) Pearson correlation coefficient among each sample. (C, D) Heatmap and volcano plot analysis displaying the DEGs (p < 0.05 and fold change > 1.5). (E, F) GO enrichment analysis based on DEGs. (G, H) KEGG enrichment analysis based on DEGs. (I) GSEA involved in the HIF-1 signaling pathway. (J) Expression of HMOX1 in the intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) subset based on single-cell datasets. (K) The relative expression levels of HMOX1 in colon tissues of UC patients and the healthy control. (L) HMOX1 mRNA expression levels of HT-29 and Caco2 cells in D_T and CMVs groups. (M, N) HMOX1 protein levels of HT-29 and Caco2 cells in D_T and CMVs groups by Western blot and IF analysis. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

HMOX1 (HO-1), as a pivotal effector molecule in the HIF-1 signaling pathway, garnered our attention because several studies have indicated that HIF-1 signaling pathway activation and HMOX1 gene regulation significantly enhance intestinal barrier function [28–30]. Based on single-cell datasets, HMOX1 was significantly expressed in colonocyte and tuft cells of the IECs subset (Fig. 7J). However, there was a marked decrease in the expression of HMOX1 in colon tissues of ulcerative colitis (UC) patients compared with the healthy control (Fig. 7K) [31]. Impressively, qRT-PCR, western blot, and IF demonstrated significant enhancement in the mRNA expression and protein levels of HMOX1 in D_T-induced epithelial cell lines Caco-2 and HT-29 treated with L. reuteri-CMVs (Fig. 7L-N).

L. reuteri-CMVs regulate mucosal immune responses

It is known that an aberrant intestinal mucosal immune system is involved in the accumulation of T cells and their cytokines, which participate in the pathophysiology and progression of IBD [32]. T cells are generally composed of three main groups: proinflammatory CD8+ T cells with cytotoxic capacity, CD4+ T helper (Th) cells with innate immunity control, and anti-inflammatory CD4+ T cells (Treg) with inflammatory response repression [33, 34]. In addition, naïve CD4+ T cells are activated and differentiated into distinct cell subtypes according to transcript factors, including double positive (DP) CD4+CD8+ T cells [35]. DP CD4+CD8+ T cells play a crucial role in the suppression of intestinal inflammation, maintenance of gut mucosal homeostasis, and secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines. We have previously found that the population of DP CD4+CD8+ T cells was markedly decreased in colon samples of UC patients and DSS-induced colitis mice compared to their corresponding healthy control colon samples [21]. Moreover, we further demonstrated that the increase of DP CD4+CD8+ T cells in colon tissues inhibited inflammatory cytokine release, suppressed the intestinal inflammation response, and maintained gut mucosal homeostasis [20]. However, whether L. reuteri-CMVs have an impact on the population of DP CD4+CD8+ T cells remains unclear. In DSS-induced C57BL/6 colitis mice, the number of DP CD4+CD8+ T cells was dramatically decreased in the colon samples compared to the healthy control group. Strikingly, L. reuteri-CMVs treatment markedly promoted the population of DP CD4+CD8+ T cells in the colon tissues of these mice (Fig. 8A). Consistently, L. reuteri-CMVs administration prominently increased the number of DP CD4+CD8+ T cells in the colon tissues of DSS-induced colitis in L. reuteri-depleted mice (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

L. reuteri-CMVs promote the differentiation of double positive (DP) CD4+CD8+ T cells. (A) IF images showing the population of DP CD4+CD8+ T cells increased in colon samples of L. reuteri-CMVs treating DSS-induced C57BL/6 colitis mice. (n = 3). (B) L. reuteri-CMVs treatment promoting the differentiation of DP CD4+CD8+ T cells for DSS-induced colitis in L. reuteri-depleted C57BL/6 mice. (n = 3)

In vivo distribution of L. reuteri-CMVs

The therapeutic effect of oral agents hinges on their specific accumulation in the inflamed colon. To investigate the in vivo distribution profiles of orally administered L. reuteri-CMVs, we tracked IRDye® 800CW-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs at different time points (4, 12, and 24 h) in both the healthy control group and DSS-induced C57BL/6 colitis mice. The results at 4 h showed that fluorescence dye signals were mainly distributed in the stomach and small intestine in both groups. At 12 h, the signals gradually increased in the colon and six main organs (brain, heart, liver, lung, kidney, and spleen) in both groups. However, the signals gradually weakened in the colon and six main organs in the healthy control group at 24 h, whereas they remained stable in the colon of the DSS-induced colitis group (Figure S6A).

Furthermore, in order to confirm the cellular localization of L. reuteri-CMVs in the colon, fluorescence signals of Dil-labeled L. reuteri-CMVs were detected in the tissues of the stomach, small intestine, and colon in DSS-induced colitis mice. Interestingly, strong signals were observed in the colon, mainly in colonic epithelial cells, whereas few signals were detected in the stomach and small intestine (Figure S6B).

Biosafety of orally administered L. reuteri-CMVs

Biosafety is a critical consideration for the clinical translation of L. reuteri-CMVs. To assess their safety profile, we evaluated the potential cytotoxicity of L. reuteri-CMVs in the epithelial cell lines Caco-2 and HT-29. MTT assays showed that L. reuteri-CMVs had no cytotoxicity against Caco-2 and HT-29 cells at concentrations up to 100 µg/ml (Figure S7A and S7B). Subsequently, blood serum samples and vital organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) were obtained from the C57BL/6 mice divided into the healthy control group, PBS group, and CMVs group. H&E staining revealed that L. reuteri-CMVs treatment had no noticeable signs of tissue or cellular damage in the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney compared with the healthy control group and PBS group (Figure S7C). In addition, L. reuteri-CMVs treatment showed no significant changes in CK-MB, ALT, AST, CREA, and UREA levels in comparison with the healthy control group and PBS group (Figure S7D).

Discussion and conclusion

IBD is a chronic and relapsing inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract with two main subtypes: UC and Crohn’s disease. The etiology and pathogenesis of IBD are very complicated and not fully undisclosed [36]. In addition to genetic predisposition and environmental factors, gut microbiota dysbiosis plays a crucial role in the development and progression of IBD [36, 37]. Accordingly, restoration of the gut microbiota, such as fecal microbiota transplantation, has displayed excellent therapeutic effects in clinical applications for IBD patients [38]. Bacterial EVs derived from parental bacteria contain several biological components from within the parent bacteria that facilitate bacteria-bacteria and bacteria-host communication, thereby modulating gut homeostasis [37]. Consequently, bacterial EVs are emerging as pivotal regulators in the pathogenesis of IBD and as promising therapeutic modalites [37, 39]. In this study, we found that oral administration of L. reuteri-CMVs suppressed the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-12, and IFN-γ) while promoting the level of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, effectively alleviating the DSS-induced colitis mice. The underlying mechanisms by which L. reuteri-CMVs mitigate colitis are versatile and multifaceted. We discovered that L. reuteri-CMVs restored gut microbiota dysbiosis and promoted the growth of AKK. Moreover, L. reuteri-CMVs increased the expression of tight junction proteins (Muc2, ZO-1, Cdh1, and Ocln), maintaining intestinal barrier integrity by activating the HIF-1 signaling pathway. In addition, L. reuteri-CMVs promoted the population of anti-inflammatory DP CD4+CD8+ T cells to suppress inflammatory responses and promote immunological tolerance.

The importance of the gut microbiota in the pathogenesis and progression of IBD is undisputed. The gut microbiota in the IBD shows a marked decrease in abundance and diversity, as well as a prominent increase in pathogenic bacterium [40]. For instance, the abundance of Roseburia and Phascolarctobacterium was dramatically decreased, whereas that of Clostridium was significantly increased in the gut microbiota of IBD patients [41]. Accordingly, the gut microbiota secretes bacterial EVs to construct bacteria-bacteria and bacteria-host connections, stabilize the intestinal microenvironments, and regulate host health. In terms of bacteria-bacteria interactions, bacterial EVs play a central role in modulating intestinal homeostasis by helping, competing with, or eliminating other bacteria [42]. For instance, enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli-derived OMVs prevent the growth of probiotics and promote the IECs injury, contributing to intestinal inflammation [43]. On the contrary, Clostridium butyricum or AKK-derived OMVs markedly improve the abundance and diversity of the gut microbiota, and significantly promote the growth of probiotics, such as Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, and Alistipes, resulting in the attenuation of colitis in mice [15, 44]. Recently, more attention has been paid to concentrating on the function of Gram-negative bacteria-derived OMVs rather than Gram-positive bacteria-derived CMVs [45]. In this study, we found that L. reuteri-CMVs restored the balanced gut microbial structure. Furthermore, L. reuteri-CMVs were internalized by the beneficial bacteria AKK and promoted its growth in vivo and in vitro.

AKK is a pivotal commensal bacterium that predominantly colonizes the mucus layer of the human gut. Extensive research has demonstrated its capacity to enhance intestinal barrier integrity by promoting mucus layer thickness, stimulating antimicrobial peptide production, and supporting intestinal stem cell proliferation [46, 47]. AKK is particularly noted for its exceptional mucin-degrading ability, which is primarily attributed to a diverse repertoire of glycosidases. These enzymes enable AKK to acquire essential nutrients and thus contribute to both bacterial growth and the maintenance of intestinal health [48]. A recent study highlighted the role of the glycosidase Amuc_2109 from AKK, which has been shown to mitigate colitis in murine models by enhancing the intestinal barrier and modulating the gut microbiota [49]. In our study, we found that L. reuteri-CMVs were capable to upregulate the gene expression of glycosidases, including beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase and alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase. This upregulation activated glycan degradation and metabolic pathways, thereby promoting the AKK proliferation, further revealing a novel mechanism by which L. reuteri-CMVs regulate the microbiota and promote intestinal health.

The intestinal barrier is comprised of IECs and intercellular tight junction proteins, which play a crucial role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis and resisting intestinal infections [50]. An impaired intestinal barrier leads to “leaky gut” (or intestinal hyperpermeability), which is closely correlated with the pathogenesis and progression of IBD [51]. Recently, it has been found that the bacterial EVs exert various roles in the intestinal barrier based on their origin. Desulfovibrio fairfieldensis, as an opportunistic pathogen prevalent in the human intestine, has been found to down-regulate the expression of tight junction proteins, including Ocln, ZO-1, and ZO-2, thereby impairing intestinal barrier function in mice [52]. Similarly, pathogen Fusobacterium nucleatum-secreted OMVs induce the apoptosis of IECs through FADD-receptor interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1)-caspase-3 pathway, resulting in intestinal barrier dysfunction [53]. On the contrary, EVs from probiotic bacteria prevent intestinal inflammation and maintain intestinal barrier function. For example, probiotic E. coli-derived OMVs promote the levels of tight junction protein via activating the NOD1 signaling pathway, leading to intestinal homeostasis [54]. AKK-derived OMVs up-regulate the expression of tight junction proteins, including Ocln and ZO-1, enhancing the integrity of the gut barrier and attenuating intestinal inflammation in colitis mice [44]. In our study, we discovered that L. reuteri-CMVs were internalized by IECs and elevated the levels of tight junction proteins such as Muc2, ZO-1, Cdh1, and Ocln in colitis mice. Moreover, L. reuteri-CMVs decreased gut permeability and maintained the integrity of the intestinal barrier in colitis.

Extensive studies have shown that the HIF-1 signaling pathway and its critical effector molecules regulate the expression of the epithelial barrier genes, such as mucin-3, intestinal trefoil factor-3 and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, contributing to providing intestinal barrier protection and promoting intestinal barrier wound healing [28, 30, 55]. Moreover, it has been found that HIF-1 knockout mice are highly susceptible to DSS-induced colitis, exhibiting greater body weight loss, faster onset of rectal bleeding, and shorter colon length compared to wild-type animals [56]. In addition, HIF-1 expression is dramatically decreased in colon tissues in TNBS-induced colitis, which is highly correlated with more severe clinical symptoms, such as body weight loss, shortened colon length, and increased DAI [57]. However, the activation of HIF-1 promotes the expression of barrier-protective genes, resulting in the protection of epithelial barrier function and the attenuation of colitis [57]. Thus, the HIF-1 signaling pathway is a promising therapeutic candidate to administrate IBD. In this study, we found that HMOX1, as a critical effector molecule of the HIF-1 signaling pathway, was predominantly enriched in the IECs of the healthy control, whereas it was significantly decreased in colon tissues of UC patients. Moreover, RNA sequencing analysis revealed that D_T-treated IECs contributed to the decrease of HMOX1 expression and the inactivation of the HIF-1 signaling pathway. However, L. reuteri-CMVs treatment reversed the HMOX1 level decrease and the HIF-1 signaling pathway inactivation, thereby alleviating intestinal barrier damage.

Additionally, bacterial EVs also play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis and development of IBD through modulating the immune response and promoting anti- or pro-inflammatory factors. For instance, Bacteroides fragilis-derived OMVs activated the dendritic cells via toll-like receptor 2, contributing to enhancing regulatory T cells and anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 production, thereby ameliorating the colitis [58]. Similarly, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron-secreted OMVs activated regulatory dendritic cells and promoted the expression of IL-10, resulting in intestinal homeostasis [59]. DP CD4+CD8+ T cells, as intestinal immune cells, are crucial for the suppression of intestinal inflammation, maintenance of gut mucosal homeostasis, and secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines. We have previously demonstrated that the population of DP CD4+CD8+ T cells was dramatically decreased in both UC patients and DSS-induced colitis [21]. Subsequently, we further found that an increase in DP CD4+CD8+ T cells within colon tissues inhibited inflammatory cytokine release, suppressed the intestinal inflammation response, and maintained gut mucosal homeostasis [20]. In this study, we observed that L. reuteri-CMVs administration markedly elevated the population of DP CD4+CD8+ T cells, promoted the expression of IL-10, and modulated the intestinal immune response in colitis models.

The off-target effects of therapeutic agents in non-target tissues are a critical concern in the treatment of UC, as these effects can provoke inflammatory responses, aberrant immune activation, or other toxic side effects. In our study, we demonstrate that orally administered L. reuteri-CMVs effectively accumulate at the site of colitis lesions in mice, without significant distribution to other organs. In vitro experiments further confirmed that L. reuteri-CMVs are efficiently endocytosed by IECs. Histological analyses of other organs did not reveal any notable morphological alterations, and functional assays of the heart, liver, and kidneys showed no significant differences between the treatment and control groups. Based on the data from our study, although no substantial off-target effects were observed in non-gastrointestinal tissues, future studies should further validate the systemic impact of L. reuteri-CMVs, particularly regarding their safety profile in long-term therapies and varied dosing regimens. Additionally, targeted modifications to L. reuteri-CMVs may be necessary to further optimize their gastrointestinal specificity and minimize potential adverse effects in non-target tissues.

This study presents the following advantages. First, our findings confirm one of the mechanistic knowledge about L. reuteri in the alleviation of colitis. Second, we elucidate key mechanisms involved in gut microbiota-microbiota and microbiota-host interactions in the attenuation of colitis. Third, according to our previous study on exosomes as a novel generation of targeted delivery agents in the treatment of IBD [60, 61], L. reuteri-CMVs are particularly explored as delivery carriers in the administration of colitis. Moreover, the combination of L. reuteri-CMVs with existing therapeutic strategies holds considerable promise for enhancing treatment efficacy. L. reuteri-CMVs may complement conventional therapies at multiple levels. Their immunomodulatory properties could potentially reduce the dosage requirements of conventional drugs, thereby mitigating their associated side effects. Moreover, their ability to modulate the gut microbiota and repair the intestinal epithelial barrier could amplify the anti-inflammatory effects of biologics. Additionally, they may modulate the immunosuppressive actions of corticosteroids, reducing the risk of infection.

Undeniably, our study has several limitations. While L. reuteri-CMVs demonstrated significant short-term efficacy in a colitis model, further long-term pharmacological studies are required to establish their clinical applicability. In fact, clinical trials have shown that an 8-week course of rectal infusion of L. reuteri significantly alleviated mucosal inflammation in children with distal UC, highlighting the potential for probiotics to exert long-term effects on intestinal mucosal immunity [62]. Moreover, preclinical evidence suggests that oral administration of L. reuteri-CMVs in combination with photothermal therapy resulted in complete tumor elimination within 32 days in a mouse tumor model. Notably, L. reuteri-CMVs demonstrated high therapeutic efficacy across various routes of administration—oral, intraperitoneal, and intravenous—owing to their robust environmental stability, which supports their potential for sustained therapeutic effects [63]. Therefore, future investigations should focus on assessing the long-term impacts of L. reuteri-CMVs administration, optimizing administration frequency and dosage, and exploring their specific effects on intestinal immune responses and microbiota composition in extended treatment regimens. In addition, despite the invaluable contributions of mouse models to UC research, their direct translation to human disease remains uncertain. Several key factors account for these discrepancies. First, differences in immune system development, immune cell composition, activation pathways, and response timing between mice and humans may result in variations in immune responses that limit the relevance of findings from mouse models to human patients. Additionally, disparities in diet, living conditions, and environmental exposures between mice and humans can influence the composition and function of the gut microbiota, further complicating the comparison. Importantly, the interactions between the microbiota and the immune system in mice are not fully representative of the human scenario. Mouse models also struggle to capture the genetic and environmental diversity inherent in human populations [64, 65]. These differences present challenges in translating the efficacy of L. reuteri-CMVs to human clinical applications. To bridge the gap between preclinical findings and clinical trials, future studies should consider incorporating humanized mouse models, intestinal organoids, or other animal models, such as non-human primates, to enhance the translatability of these therapies to human disease.

In conclusion, our findings disclose the potential of L. reuteri-CMVs as a safe and effective therapeutic strategy for mitigating the DSS-induced colitis by restoring the gut microbiota, protecting intestinal barrier function, and modulating immune responses. These results suggest that L. reuteri-CMVs may be a promising alternative approach for the intervention and prevention of colitis.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Ningning Yue, Hailan Zhao, Peng Hu, and Defeng Li designed the study, performed experiments, and wrote the manuscript; Yuan Zhang, Chengmei Tian, Chen Kong, Zhiliang Mai, Longbin Huang, and Qianjun Luo contributed to performing the experiments and data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; Daoru Wei, Ruiyue Shi, Shaohui Tang, and Yuqiang Nie provided the advisement. Yujie Liang, Jun Yao, Lisheng Wang, and Defeng Li supervised the research and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Committee of Shenzhen (No.JCYJ20210324113802006, No.JCYJ2022053015180024, No.JCYJ20240813175903005, and No.JCYJ20210324113613035).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Shenzhen People’s Hospital, Shenzhen, China (No. 2024-118).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ningning Yue, Hailan Zhao and Peng Hu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yujie Liang, Email: liangyjie@126.com.

Jun Yao, Email: yj_1108@126.com.

Lisheng Wang, Email: wanglsszrmyy@163.com.

Defeng Li, Email: ldf830712@163.com.

References

- 1.de Vos WM, Tilg H, Van Hul M, et al. Gut microbiome and health: mechanistic insights. Gut. 2022;71:1020–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mars RAT, Yang Y, Ward T, et al. Longitudinal multi-omics reveals subset-specific mechanisms underlying irritable bowel syndrome. Cell. 2020;183:1137–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tilg H, Adolph TE, Gerner RR, et al. The intestinal microbiota in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:954–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd-Price J, Arze C, Ananthakrishnan AN, et al. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature. 2019;569:655–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopetuso LR, Deleu S, Godny L et al. The first international Rome consensus conference on gut microbiota and faecal microbiota transplantation in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2023;72:1642–1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Suez J, Zmora N, Segal E, et al. The pros, cons, and many unknowns of probiotics. Nat Med. 2019;25:716–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iyaswamy A, Lu K, Guan XJ et al. Impact and advances in the role of bacterial extracellular vesicles in neurodegenerative disease and its therapeutics. Biomedicines 2023;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Choi Y, Park HS, Kim YK. Bacterial extracellular vesicles: a candidate molecule for the diagnosis and treatment of allergic diseases. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2023;15:279–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hosseini-Giv N, Basas A, Hicks C, et al. Bacterial extracellular vesicles and their novel therapeutic applications in health and cancer. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:962216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang X, Dai N, Sheng K, et al. Gut bacterial extracellular vesicles: important players in regulating intestinal microenvironment. Gut Microbes. 2022;14:2134689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie J, Haesebrouck F, Van Hoecke L et al. Bacterial extracellular vesicles: an emerging avenue to tackle diseases. Trends Microbiol 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Farrugia C, Stafford GP, Murdoch C. Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles increase vascular permeability. J Dent Res. 2020;99:1494–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engevik MA, Danhof HA, Ruan W et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum secretes outer membrane vesicles and promotes intestinal inflammation. mBio 2021;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Ma L, Shen Q, Lyu W, et al. Clostridium butyricum and its derived extracellular vesicles modulate gut homeostasis and ameliorate Acute Experimental Colitis. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10:e0136822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu Z, Chen J, Liu Y, et al. The role of potential probiotic strains Lactobacillus reuteri in various intestinal diseases: new roles for an old player. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1095555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh TP, Tehri N, Kaur G, et al. Cell surface and extracellular proteins of potentially probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri as an effective mediator to regulate intestinal epithelial barrier function. Arch Microbiol. 2021;203:3219–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garg S, Singh TP, Malik RK. In vivo implications of potential probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri LR6 on the gut and immunological parameters as an Adjuvant against Protein Energy Malnutrition. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2020;12:517–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H, Zhou C, Huang J, et al. The potential therapeutic role of Lactobacillus reuteri for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12:1569–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu MZ, Xu HM, Liang YJ, et al. Edible exosome-like nanoparticles from portulaca oleracea L mitigate DSS-induced colitis via facilitating double-positive CD4(+)CD8(+)T cells expansion. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21:309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu HM, Xu J, Yang MF, et al. Epigenetic DNA methylation of Zbtb7b regulates the population of double-positive CD4(+)CD8(+) T cells in ulcerative colitis. J Transl Med. 2022;20:289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee Y, Sugihara K, Gillilland MG 3, et al. Hyaluronic acid-bilirubin nanomedicine for targeted modulation of dysregulated intestinal barrier, microbiome and immune responses in colitis. Nat Mater. 2020;19:118–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Li J, Niu C, Ai H, et al. TSP50 attenuates DSS-Induced colitis by regulating TGF-beta signaling mediated maintenance of Intestinal Mucosal Barrier Integrity. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11:e2305893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jofra T, Galvani G, Cosorich I, et al. Experimental colitis in IL-10-deficient mice ameliorates in the absence of PTPN22. Clin Exp Immunol. 2019;197:263–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGuckin MA, Eri R, Simms LA, et al. Intestinal barrier dysfunction in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:100–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dahlgren D, Lennernas H. Review on the effect of chemotherapy on the intestinal barrier: epithelial permeability, mucus and bacterial translocation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;162:114644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merga Y, Campbell BJ, Rhodes JM. Mucosal barrier, bacteria and inflammatory bowel disease: possibilities for therapy. Dig Dis. 2014;32:475–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim YI, Yi EJ, Kim YD, et al. Local Stabilization of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1alpha Controls Intestinal Inflammation via enhanced gut barrier function and Immune Regulation. Front Immunol. 2020;11:609689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goggins BJ, Minahan K, Sherwin S, et al. Pharmacological HIF-1 stabilization promotes intestinal epithelial healing through regulation of alpha-integrin expression and function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;320:G420–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh R, Chandrashekharappa S, Bodduluri SR, et al. Enhancement of the gut barrier integrity by a microbial metabolite through the Nrf2 pathway. Nat Commun. 2019;10:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nie H, Lin P, Zhang Y, et al. Single-cell meta-analysis of inflammatory bowel disease with scIBD. Nat Comput Sci. 2023;3:522–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]