ABSTRACT

The C1 and C2 alcohols hold great promise as substrates for biomanufacturing due to their low cost and rich resources. Pichia pastoris is considered a preferred host for methanol and ethanol bioconversion due to its natural utilization of methanol and ethanol. However, the scarcity of strong and tightly regulated alcohol-inducible promoters limits its extended use. This study aimed to develop enhanced methanol- and ethanol-inducible promoters capable of improving gene expression in P. pastoris. Rational design strategies were employed to rewire the upstream regulatory sequence of the methanol-inducible PAOX1, generating several high-strength methanol-inducible promoters with a stringent regulatory pattern. Eleven strong promoters were identified from 36 endogenous ethanol-inducible candidates recognized from transcriptome analysis. Core promoter regions, the crucial element influencing transcriptional strength, were also characterized. Five high-activity core promoters were then combined with four upstream regulatory sequences of high-strength promoters, resulting in four groups of synthetic promoters. Ultimately, the highly active methanol-inducible PA13 and ethanol-inducible P0688 and PsynIV-5 were selected for the expression of an α-amylase and yielded enzyme activity 1.6, 2.6, and 4.5 times higher as compared to that of PAOX1. This work expands the genetic toolkit available for P. pastoris, providing more precise and efficient options for regulating gene expression. It benefits the use of P. pastoris as an efficient platform for the C1 and C2 alcohol-based biotransformation in industrial biotechnology.

IMPORTANCE

P. pastoris represents a preferred microbial host for the bio-utilization of C1 and C2 alcohols that are regarded as renewable carbon sources based on clean energy. However, lack of efficient and regulated expression tools highly limits the C1 and C2 alcohols based bioproduction. By exploring high-strength and strictly regulated alcohol-inducible promoters, this study expands the expression toolkit for P. pastoris on C1 and C2 alcohols. The newly developed methanol-inducible PA13 and ethanol-inducible PsynIV-5 demonstrate significantly higher expression levels than the commercial PAOX1 system. The endogenous and synthetic promoter series established in this study provides new construction references and alternative tools for expression control in P. pastoris for C1 and C2 alcohols based biomanufacturing.

KEYWORDS: Pichia pastoris, methanol, ethanol, synthetic promoter

INTRODUCTION

C1 and C2 alcohols, i.e., methanol and ethanol, have notable advantages as substrates for biomanufacturing and bioconversion, owing to their low cost, wide availability, and high energy density (1–4). Both C1 and C2 alcohols can be synthesized from CO2, making them promising candidates for next-generation clean energy and substrates (3, 5, 6). Compared to traditional substrates like glucose, methanol has a higher reduction degree, which is beneficial for product synthesis (1, 7, 8). Ethanol, on the other hand, is easily metabolized into acetyl-CoA, providing sufficient precursor for microbial growth and product synthesis (2, 9–11). These benefits have driven researchers to develop efficient bioconversion systems utilizing methanol and ethanol.

Pichia pastoris (syn. Komagataella phaffii) is considered an ideal chassis for methanol biotransformation due to its natural methanol metabolic pathways and powerful methanol assimilation capacity (1, 4, 7, 12). Furthermore, P. pastoris exhibits efficient ethanol metabolism, enabling the synthesis of various products from ethanol (2, 9–11). Numerous studies have demonstrated that P. pastoris is a versatile chassis host for methanol and ethanol biotransformation. For efficient biotransformation, enzyme expression control by strong and tightly regulated promoters is often required (13). While P. pastoris possesses several effective methanol-inducible promoters (14), ethanol-inducible promoters are quite limited (9, 15). Moreover, the scarcity of strong and tightly regulated promoters limits further improvements in biotransformation efficiency of P. pastoris (13, 16).

To present, different transcriptional regulatory tools for C1 and C2 alcohols biotransformation have been developed in P. pastoris (9–11, 17–21). However, most high-strength transcriptional tools require modifications to cellular regulatory networks or the design of complex genetic circuits (9, 19–24). In complicated regulation cases particularly the pathway control, simpler and more straightforward transcriptional tools are preferred. Therefore, many studies focused on the modification and reconstruction of high-strength and tightly regulated promoters, especially the methanol-inducible alcohol oxidase 1 promoter (PAOX1) (21, 25–29). Deletions, insertions, and mutations in sequences have been performed to obtain higher-strength PAOX1 variants. As transcription factors and their binding sites on the PAOX1 have been identified (30–32), the rational promoter modifications become predictable and feasible. In contrast, research on ethanol-inducible promoters in P. pastoris still remains limited. This study rationally modifies and reconstructs the upstream regulatory sequence (URS) of PAOX1 based on the distribution of transcription factor-binding sites to select higher-strength methanol-inducible promoter mutants. On the other hand, transcriptome analysis was used to identify strong and tightly inducible ethanol promoters. High-activity endogenous core promoters were further screened and combined with high-activity URSs to construct synthetic alcohol-inducible promoters. With these efforts, we aim to offer flexible and efficient expression tools for C1 and C2 alcohols based biomanufacturing in P. pastoris.

RESULTS

Redesign of upstream regulatory sequence of PAOX1

The PAOX1 is the most widely used methanol-inducible promoter in P. pastoris. Previous studies have identified binding sites of transcription factors within the URS of PAOX1, allowing rational reconstruction of the URS. Our previous study proved that activators of Mxr1, Prm1, and Mit1 had multiple binding sites within the URS, while the repressor Nrg1 showed two independent binding sites and three overlapping binding sites with Mxr1 and Prm1, respectively (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). These results clarified the basic mechanism that supporting the rational rewiring of the URS.

Fig 1.

Redesign and characterization of URS of PAOX1. (A) The URS of the PAOX1 promoter was systematically truncated, resulting in a series of deletion mutants (PA1 to PA11). The binding sites for key transcription factors (Nrg1, Mxr1, Mit1, Prm1, details in Fig. S1) and the TATA box are highlighted in different colors. (B) The mutant PA12 was constructed by combining the deletion sequences of two high-strength mutants, PA2 and PA3. Additional 5′ end duplications of PA12 generated three more mutants (PA13, PA14, and PA15). The duplication sequences are marked with dashed boxes. Mit1 was overexpressed by PGAP to further improve the activity of PA13. Then, the GFP intensity of the strains was measured after cultured in YNM medium. Statistical significance of GFP intensity of each strain at 24 h is shown (**P < 0.01).

To enhance the activity of the promoter, we initially deleted the region containing the Nrg1-binding sites at the 5′ end of PAOX1, generating two mutants: PA1 (Δ−940~−848 bp) and PA2 (Δ−940~−718 bp) (Fig. 1A). The green fluorescent protein (GFP) was used as a reporter to evaluate promoter activity. Fluorescence detection showed that the deletion of two independent Nrg1-binding sites did not increase PA1 activity significantly; but, the deletion of four Nrg1 binding sites significantly increased PA2 activity by 68.7% despite the simultaneous deletion of two Mxr1-binding sites. We then segmented and deleted unknown functional sequences between the transcriptional activator binding sequences in the URS, producing nine mutants from PA3 to PA11 (Fig. 1A). Considering that the deletion of Mxr1 binding sites did not negatively affect the mutant PA2, we deleted the long regions containing Mxr1 binding sites in PA5 and PA9. All the deletions led to significant activity reduction but not the mutant PA3. The mutant PA3 (Δ−672~−624 bp) showed a 69.1% increase in activity relative to the PAOX1. Next, we combined the most effective deletions from the high-activity mutants PA2 and PA3 to create the mutant PA12, which exhibited 2.06-fold activity as compared to the PAOX1 (Fig. 1B). To further enhance promoter strength, we separately duplicated the specific segments of 45 bp (containing two Mit1 binding sites), 97 bp (containing two Mit1 and two Mxr1 binding sites), and 222 bp (containing five Mit1 and two Mxr1 binding sites) from the 5′ end of PA12, resulting in mutants PA13, PA14, and PA15 (Fig. 1B). The results showed that PA13 exhibited 2.88-fold activity relative to the PAOX1, but no further increase in strength was observed from PA14 (2.62-fold) and PA15 (2.58-fold) despite that additional duplication of Mit1 and Mxr1 binding sequences were added. As more Mit1 binding sites were added, they may recruit more Mit1 for this rewired promoter. On the other hand, our group and other groups reported that Mit1 overexpression obviously enhanced PAOX1 activity (19, 24, 33). Therefore, we then overexpressed Mit1 to further improve the activity of PA13. This strategy increased the intensity of PA13 by 16% (Fig. 1B), achieving 3.36-fold activity relative to the PAOX1.

Subsequently, seven high-strength mutant promoters were evaluated for activity under different carbon sources to assess regulatory stringency. Despite some Nrg1 binding site were deleted, all the seven improved mutants maintained low basal expression under glucose, glycerol, and ethanol conditions (Fig. S2). In summary, through rational design and reconstruction, we generated a PAOX1 mutant toolbox and identified URS mutants with enhanced activity and high regulatory stringency, which can be applied in subsequent experimental designs.

Screening of ethanol-inducible promoters in P. pastoris

Unlike the abundance of methanol-inducible promoters, ethanol-inducible transcription tools are relatively scarce in P. pastoris. In order to identify natural promoters responsive to ethanol, we performed transcriptome sequencing on the wild-type strain GS115 under glucose and ethanol conditions. Differential gene expression analysis indicated genes with significantly higher expression in ethanol in comparison to glucose (ethanol/glucose_foldchange >5, TPM_ethanol >500) (Fig. 2A and B). A 1,000 bp sequence upstream of the start codon of these genes was chosen as the promoter region to drive GFP expression. A total of 36 endogenous ethanol-inducible promoters were identified, and their activities were tested by GFP under ethanol conditions (Fig. S3; Table S1). Among them, 11 high-strength promoters were ultimately selected for further activity assessment under different carbon sources (Fig. 2C; Fig. S4). Consistent with the transcriptome data, the P0874 showed the highest activity under ethanol conditions but also with remarkable leakage expression under glucose condition. In contrast, the P0688 and P0074 demonstrated high activity under ethanol conditions with low leakage, making them more suitable for ethanol-inducible gene expression. Additionally, some promoters also demonstrated high expression levels under methanol condition, with the P0104 and P0110 exhibiting even higher activity in methanol than in ethanol (Fig. S4). We selected seven promoters with high expression levels under both methanol and ethanol conditions. Their activities were assessed by a mixed methanol-ethanol feeding strategy, revealing that promoter activity under mixed methanol-ethanol substrates closely matched that under ethanol conditions (Fig. 2D). These findings provide valuable insights and references for their industrial applicability.

Fig 2.

Screening and characterization of ethanol-inducible promoters. The scatter plot (A) and volcano plot (B) of transcriptomic comparison of P. pastoris wild-type strain GS115 grown in glucose and ethanol conditions. Eleven promoters with good expression levels were selected from a total of 36 endogenous promoters screened by RNA-Seq analysis (Fig. S3) and marked with blue dots in (A) and (B). (C) The GFP intensity of the 11 selected promoters was measured after cultured in YNE medium. (D) The GFP intensity of the seven promoters responsive to both ethanol and methanol was measured after cultured in the YNEM medium.

Construction and characterization of synthetic promoters

In addition to URS, core promoter regions also play a crucial role in determining promoter strength. While the AOX1 core promoter (cPAOX1) is frequently studied and modified, other native core promoters have been comparatively less explored. Therefore, 12 native strong promoters (13, 14, 34–39) were selected, with the region from 20 bp upstream of the TATA box to the start codon site defined as the core promoter region (Fig. S5A). These core promoters were combined with the URS of PAOX1 to generate synthetic promoters, with their activity measured under methanol conditions by GFP fluorescence detection (Fig. S5B). Four core promoters (cPTHI11, cPGCW14, cPGAP, cPDAS2) showed higher activity than the cPAOX1. These four, along with cPAOX1, were combined with the URS of PAOX1 and three previously identified high-activity promoters (PA13, P0688, and P0074), resulting in four groups of synthetic promoters (Fig. 3A). Group I and Group II were induced with methanol, using PAOX1 and PA13 as controls, respectively. Group III and Group IV were induced with ethanol, using P0688 and P0074 as controls, respectively. In Group I, all synthetic promoters displayed activities comparable to PAOX1 (Fig. 3B). In contrast, in Group II, the synthetic promoters showed lower activity than the PA13, suggesting that URS modifications can impact the compatibility between URS and core promoters (Fig. 3C). Notably, two synthetic promoters in Group III showed higher activity than the P0688, but their induction was delayed, with significant fluorescence intensity observed only 24 h (Fig. 3D). In Group IV, synthetic promoters generally had lower activity, with only the PsynIV-5 reaching 1.2 times as that of the P0074 (Fig. 3E). Although Group I and Group II had similar URS, synthetic promoter strength trends were inconsistent, suggesting URS and core promoter functions are interdependent. Additionally, the leaky expression of all synthetic promoters under glucose condition was evaluated, showing that these promoters maintained strict regulation, with regulatory patterns closely associated with their upstream regulatory sequences (Fig. S6).

Fig 3.

Design and characterization of synthetic promoters with high activity URSs and core promoters. (A) A schematic diagram illustrating the combination of four highly active URSs with five highly active core promoters, resulting in four groups of synthetic promoters. The activities of synthetic promoters in group I (B) and group II (C) were measured after cultured in YNM medium. The activities of synthetic promoters of group III (D) and group IV (E) were measured in after cultured YNE medium.

Expression of α-amylase by synthetic alcohol-inducible promoters

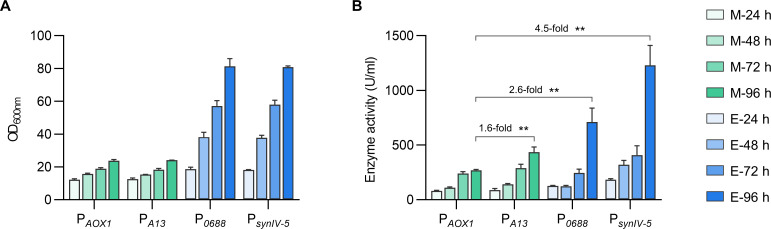

Considering promoter strength and response sensitivity, we selected methanol-inducible PA13 and ethanol-inducible P0688 and PsynIV-5 to express an α-amylase of deep-sea origin (40), with the same protein expressed under PAOX1 as the control, to evaluate their performance in protein expression. Both strains showed similar growth trends under the same carbon source conditions, suggesting that the synthetic promoters did not impose an additional burden on cellular regulatory networks (Fig. 4A). Enzyme activity driven by PA13 under methanol was 1.6 times higher than that driven by PAOX1. Under ethanol condition, enzyme activity driven by the P0688 and PsynIV-5 were 2.6 and 4.5 times higher than that driven by PAOX1, respectively (Fig. 4B). These results differed from fluorescence assay, likely due to substantial cell growth under ethanol condition. Overall, these engineered methanol- and ethanol-inducible promoters showed better expression capacity in comparison to the widely used PAOX1 in P. pastoris.

Fig 4.

Evaluation of high-activity promoters on α-amylase production. Methanol-inducible PAOX1 and PA13, along with ethanol-inducible P0688 and PIV-5, were employed to express α-amylase. The OD600nm of culture broth (A) and enzyme activity of α-amylase (B) were measured every 24 h. Statistical significance of enzyme activity of each strain at 96 h is shown (**P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

The C1 and C2 alcohols, which can be produced in large quantities through catalytic conversion of syngas components (such as CO and CO2) or from various renewable resources, have the potential to serve as renewable feedstocks for the future biomanufacturing industry (1, 2, 5, 7). P. pastoris, with its efficient methanol and ethanol metabolism, serves as an ideal chassis for alcohol biotransformation. Developing effective induction tools that decouple cell growth from product synthesis is crucial for optimizing microbial cell factories. In this study, we expanded the alcohol-inducible expression toolkit in P. pastoris by screening and engineering a range of native and synthetic promoters with varying strengths. These efficient tools can well support P. pastoris as a superior chassis platform for green biomanufacturing and bioconversion.

The reconstruction of the PAOX1 has consistently attracted significant attention. In this study, using a rational design strategy targeting the URS of PAOX1, we successfully generated several mutants with enhanced promoter strength while maintaining stringent regulation. The URS of PAOX1 has been a longstanding research focus, but prior random deletion strategies hardly provided significant activity improvements (27, 29). In contrast, our approach, combining the deletion of repressor binding sites and the duplication of activator binding sites, led to a 2.88-fold increase in comparison to the PAOX1 activity, highlighting the significance of the −717 to −673 region. The promoter remodeling strategies in this study could provide valuable reference and assistance for further research on PAOX1 and artificial modification of other promoters (41, 42). Despite deleting four repressor sites, the mutated promoters maintained stringent regulation, presenting them as strong methanol-inducible tools, potentially replacing the commercial PAOX1 system. However, the deletion of non-transcription factor binding sequences in the −672 to −163 region had no positive effect, confirming that these sequences, though not bound by transcription factors, play significant roles in PAOX1 activity. The base mutation strategy (25, 28) could be applied in this region, alongside the deletions from this study, to potentially achieve a more potent methanol-inducible promoter in future.

Beyond promoter modification, some studies have explored transcription factor reprogramming to improve expression efficiency and regulatory flexibility in P. pastoris (19, 21, 33, 43). For example, overexpression of activators, knock-out of repressors, and dynamic control of transcription factor expression. In this study, Mit1 overexpression further enhanced the activity of PA13, illustrating the compatibility of promoter engineering with transcription factor reprogramming. Therefore, the combined use of cis-acting element engineering and trans-acting element rewiring can improve promoter activity synergistically, which will certainly facilitate the development of customizable and high-performance promoters.

Ethanol-driven biosynthesis in P. pastoris has been extensively studied, showing promising applications (9–11). However, the scarcity of robust ethanol-responsive regulatory tools remains a major bottleneck in developing ethanol-based biosynthesis systems. We addressed this by conducting transcriptomic analyses to identify ethanol-inducible promoters with diverse expression strengths and regulatory stringency, offering valuable tools for ethanol-based biotransformation. Further screening and core promoter replacement significantly enhanced the activity of these ethanol-inducible promoters. Notably, the PsynIV-5 under ethanol outperformed the PAOX1 under methanol in protein expression, making it a promising new tool for ethanol-driven production. Additionally, we identified and characterized dual carbon source-inducible promoters (e.g., P0104 and P0110) with comparable expression under ethanol and methanol conditions, offering greater flexibility and broader application potential for P. pastoris in alcohol utilization and conversion.

The interdependence between the URS and core promoter regions also played a crucial role in determining promoter strength. While the URS is essential for regulating the transcriptional response to external signals, the core promoter governs the recruitment of basal transcriptional machinery, directly affecting overall promoter strength (44, 45). Our study revealed that the compatibility between URS and core promoters is not always straightforward. For example, synthetic promoters combining high-activity URS with various core promoters exhibited inconsistent performance, with some constructs even displaying lower activity than expected (Fig. 3C). These findings suggest that URS modifications may affect core promoter functionality in ways that are not fully predictable, possibly due to changes in chromatin structure or transcription factor dynamics. Therefore, future promoter engineering efforts should consider the complex interplay between URS and core promoter regions to achieve optimal expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, strains, and growth conditions

The plasmids pP-PAOX1G and pPlacO1cAG were previously constructed in our laboratory (23). Other plasmids used in this study were constructed by Gibson assembly. Details of plasmid construction can be found in the supplemental material. All plasmids were linearized with SalI and transformed into competent cells of P. pastoris wild-type strain GS115. The plasmids and strains used in this study are listed in Tables S2 and S3. Primers used for the construction of plasmids were synthesized by Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd., China, and listed in Table S4. Escherichia coli was cultured at 37°C in LB medium (0.5% yeast extract, 1% tryptone, and 1% NaCl). 100 µg/mL ampicillin was added when required. P. pastoris was cultured at 30°C in YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% tryptone, and 2% glucose) medium for cell growth, or YND (0.67% YNB, 0.5% glucose) plate for transformant screening.

Transcriptome analysis

The wild-type P. pastoris GS115 was pre-cultured in YPD medium to a log phase and then separately shifted to YNE medium (0.67% YNB, 0.5% ethanol) and YND medium supplement with histidine of 50 µg/mL. Each group was cultured independently in triplicate. Cells were collected at 6 h for RNA extraction and transcriptome sequencing, which was performed by Majorbio (Shanghai, China). High-quality reads were aligned onto the indexed GS115 reference genome (GCF_000027005.1_ASM2700v1) (46). Bioinformatic analysis was performed using the online tools of Majorbio Cloud Platform (http://www.majorbio.com).

GFP fluorescence measurement

P. pastoris strains were pre-cultured in YPD medium to a log phase and then transferred to YNB medium containing the required carbon sources (1% glucose, 1% glycerol, 0.5% ethanol, 0.5% methanol) in a 24-well plate. Culture samples were collected at specific time points for fluorescence detection. GFP fluorescence (normalized with OD600nm) from various samples was analyzed using a multi-mode microplate reader (Synergy 2, BioTek Instruments, USA).

Production and activity assays of α-amylase

P. pastoris strains producing α-amylase were pre-cultured in YPD medium to a log phase and then transferred to BMY medium (2% tryptone, 1% yeast extract, 1.34% YNB, and 100 mmol/L potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.0) supplemented with 1% methanol or 1% ethanol. Corresponding carbon sources were added every 24 h, and samples were collected to measure OD600nm and enzyme activity. The enzyme activity of α-amylase was determined by the DNS method as previously reported (40).

Statistical analysis

Data were obtained from three biological replicates from at least three experimental batches and presented as mean ± standard deviation. For transcriptomic analysis, gene expression was quantified using TPM. GraphPad Prism was used for Figure presentation and data analysis. The unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to assess the differences among the groups. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Young Scientist Fund of National Natural Science Foundation of China (32201206), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC2805102), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022M711146).

Contributor Information

Meng-hao Cai, Email: cmh022199@ecust.edu.cn.

Yvonne Nygård, Chalmers tekniska hogskola AB, Gothenburg, Sweden.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All data in the paper will be provided by authors upon request.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.02191-24.

Supplemental methods, Tables S1 to S4, and Figures S1 to S6.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sarwar A, Lee EY. 2023. Methanol-based biomanufacturing of fuels and chemicals using native and synthetic methylotrophs. Synth Syst Biotechnol 8:396–415. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2023.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sun M, Gao AX, Liu X, Bai Z, Wang P, Ledesma-Amaro R. 2024. Microbial conversion of ethanol to high-value products: progress and challenges. Biotechnol Biofuels Bioprod 17:115. doi: 10.1186/s13068-024-02546-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wagner N, Wen L, Frazão CJR, Walther T. 2023. Next-generation feedstocks methanol and ethylene glycol and their potential in industrial biotechnology. Biotechnol Adv 69:108276. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2023.108276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gregory GJ, Bennett RK, Papoutsakis ET. 2022. Recent advances toward the bioconversion of methane and methanol in synthetic methylotrophs. Metab Eng 71:99–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2021.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hamadou B, Djomdi D, Zieba Falama R, Djouldé Darnan R, Audonnet F, Fontanille P, Delattre C, Pierre G, Dubessay P, Michaud P, Christophe G. 2023. Optimization of energy recovery efficiency from sweet sorghum stems by ethanol and methane fermentation processes coupling. Bioengineered 14:228–244. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2023.2234135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shih CF, Zhang T, Li J, Bai C. 2018. Powering the future with liquid sunshine. Joule 2:1925–1949. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2018.08.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guo F, Qiao Y, Xin F, Zhang W, Jiang M. 2023. Bioconversion of C1 feedstocks for chemical production using Pichia pastoris. Trends Biotechnol 41:1066–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2023.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wu X, Cai P, Gao L, Li Y, Yao L, Zhou YJ. 2023. Efficient bioproduction of 3-hydroxypropionic acid from methanol by a synthetic yeast cell factory. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng 11:6445–6453. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c00410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu Y, Bai C, Liu Q, Xu Q, Qian Z, Peng Q, Yu J, Xu M, Zhou X, Zhang Y, Cai M. 2019. Engineered ethanol-driven biosynthetic system for improving production of acetyl-CoA derived drugs in Crabtree-negative yeast. Metab Eng 54:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Qian Z, Yu J, Chen X, Kang Y, Ren Y, Liu Q, Lu J, Zhao Q, Cai M. 2022. De novo production of plant 4'-deoxyflavones baicalein and oroxylin a from ethanol in crabtree-negative yeast. ACS Synth Biol 11:1600–1612. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.2c00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kang Y, Qian Z, Yu H, Lu J, Zhao Q, Qiao X, Ye M, Zhou X, Cai M. 2024. Programmable biosynthesis of plant-derived 4'-deoxyflavone glycosides by an unconventional yeast consortium. Small Methods 8:e2301371. doi: 10.1002/smtd.202301371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cai P, Wu X, Deng J, Gao L, Shen Y, Yao L, Zhou YJ. 2022. Methanol biotransformation toward high-level production of fatty acid derivatives by engineering the industrial yeast Pichia pastoris. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119:e2201711119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2201711119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yan C, Yu W, Yao L, Guo X, Zhou YJ, Gao J. 2022. Expanding the promoter toolbox for metabolic engineering of methylotrophic yeasts. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 106:3449–3464. doi: 10.1007/s00253-022-11948-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vogl T, Sturmberger L, Kickenweiz T, Wasmayer R, Schmid C, Hatzl AM, Gerstmann MA, Pitzer J, Wagner M, Thallinger GG, Geier M, Glieder A. 2016. A toolbox of diverse promoters related to methanol utilization: functionally verified parts for heterologous pathway expression in Pichia pastoris. ACS Synth Biol 5:172–186. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Karaoğlan M, Erden-Karaoğlan F, Yılmaz S, İnan M. 2020. Identification of major ADH genes in ethanol metabolism of Pichia pastoris. Yeast 37:227–236. doi: 10.1002/yea.3443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sun W, Zuo Y, Yao Z, Gao J, Shao Z, Lian J. 2022. Recent advances in synthetic biology applications of Pichia species, p 251–292. In Darvishi Harzevili F (ed), Synthetic biology of yeasts. Springer International Publishing, Cham. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nong L, Zhang Y, Duan Y, Hu S, Lin Y, Liang S. 2020. Engineering the regulatory site of the catalase promoter for improved heterologous protein production in Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol Lett 42:2703–2709. doi: 10.1007/s10529-020-02979-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ergün BG, Demir İ, Özdamar TH, Gasser B, Mattanovich D, Çalık P. 2020. Engineered deregulation of expression in yeast with designed hybrid-promoter architectures in coordination with discovered master regulator transcription factor. Adv Biosyst 4:e1900172. doi: 10.1002/adbi.201900172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vogl T, Sturmberger L, Fauland PC, Hyden P, Fischer JE, Schmid C, Thallinger GG, Geier M, Glieder A. 2018. Methanol independent induction in Pichia pastoris by simple derepressed overexpression of single transcription factors. Biotechnol Bioeng 115:1037–1050. doi: 10.1002/bit.26529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhu Q, Liu Q, Yao C, Zhang Y, Cai M. 2022. Yeast transcriptional device libraries enable precise synthesis of value-added chemicals from methanol. Nucleic Acids Res 50:10187–10199. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. An JL, Zhang WX, Wu WP, Chen GJ, Liu WF. 2019. Characterization of a highly stable α-galactosidase from thermophilic Rasamsonia emersonii heterologously expressed in a modified Pichia pastoris expression system. Microb Cell Fact 18:180. doi: 10.1186/s12934-019-1234-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rantasalo A, Landowski CP, Kuivanen J, Korppoo A, Reuter L, Koivistoinen O, Valkonen M, Penttilä M, Jäntti J, Mojzita D. 2018. A universal gene expression system for fungi. Nucleic Acids Res 46:e111. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu Q, Song L, Peng Q, Zhu Q, Shi X, Xu M, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Cai M. 2022. A programmable high-expression yeast platform responsive to user-defined signals. Sci Adv 8:eabl5166. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abl5166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haghighi Poodeh S, Ranaei Siadat SO, Arjmand S, Khalifeh Soltani M. 2022. Improving AOX1 promoter efficiency by overexpression of Mit1 transcription factor. Mol Biol Rep 49:9379–9386. doi: 10.1007/s11033-022-07790-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang J, Cai H, Liu J, Zeng M, Chen J, Cheng Q, Zhang L. 2018. Controlling AOX1 promoter strength in Pichia pastoris by manipulating poly (dA:dT) tracts. Sci Rep 8:1401. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19831-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Portela RMC, Vogl T, Ebner K, Oliveira R, Glieder A. 2018. Pichia pastoris alcohol oxidase 1 (AOX1) core promoter engineering by high resolution systematic Mutagenesis. Biotechnol J 13:e1700340. doi: 10.1002/biot.201700340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xuan Y, Zhou X, Zhang W, Zhang X, Song Z, Zhang Y. 2009. An upstream activation sequence controls the expression of AOX1 gene in Pichia pastoris. FEMS Yeast Res 9:1271–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2009.00571.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hartner FS, Ruth C, Langenegger D, Johnson SN, Hyka P, Lin-Cereghino GP, Lin-Cereghino J, Kovar K, Cregg JM, Glieder A. 2008. Promoter library designed for fine-tuned gene expression in Pichia pastoris. Nucleic Acids Res 36:e76. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ruth C, Zuellig T, Mellitzer A, Weis R, Looser V, Kovar K, Glieder A. 2010. Variable production windows for porcine trypsinogen employing synthetic inducible promoter variants in Pichia pastoris. Syst Synth Biol 4:181–191. doi: 10.1007/s11693-010-9057-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang X, Wang Q, Wang J, Bai P, Shi L, Shen W, Zhou M, Zhou X, Zhang Y, Cai M. 2016. Mit1 transcription factor mediates methanol signaling and regulates the alcohol oxidase 1 (AOX1) promoter in Pichia pastoris. J Biol Chem 291:6245–6261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.692053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang X, Cai M, Shi L, Wang Q, Zhu J, Wang J, Zhou M, Zhou X, Zhang Y. 2016. PpNrg1 is a transcriptional repressor for glucose and glycerol repression of AOX1 promoter in methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol Lett 38:291–298. doi: 10.1007/s10529-015-1972-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kumar NV, Rangarajan PN. 2012. The zinc finger proteins Mxr1p and repressor of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (ROP) have the same DNA binding specificity but regulate methanol metabolism antagonistically in Pichia pastoris. J Biol Chem 287:34465–34473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.365304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang J, Wang X, Shi L, Qi F, Zhang P, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Song Z, Cai M. 2017. Methanol-independent protein expression by AOX1 promoter with trans-acting elements engineering and glucose-glycerol-shift induction in Pichia pastoris. Sci Rep 7:41850. doi: 10.1038/srep41850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu B, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Yan C, Zhang Y, Xu X, Zhang W. 2016. Discovery of a rhamnose utilization pathway and rhamnose-inducible promoters in Pichia pastoris. Sci Rep 6:27352. doi: 10.1038/srep27352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Landes N, Gasser B, Vorauer-Uhl K, Lhota G, Mattanovich D, Maurer M. 2016. The vitamin-sensitive promoter PTHI11 enables pre-defined autonomous induction of recombinant protein production in Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol Bioeng 113:2633–2643. doi: 10.1002/bit.26041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liang S, Zou C, Lin Y, Zhang X, Ye Y. 2013. Identification and characterization of P GCW14: a novel, strong constitutive promoter of Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol Lett 35:1865–1871. doi: 10.1007/s10529-013-1265-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ahn J, Hong J, Park M, Lee H, Lee E, Kim C, Lee J, Choi E, Jung J, Lee H. 2009. Phosphate-responsive promoter of a Pichia pastoris sodium phosphate symporter. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:3528–3534. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02913-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stadlmayr G, Mecklenbräuker A, Rothmüller M, Maurer M, Sauer M, Mattanovich D, Gasser B. 2010. Identification and characterisation of novel Pichia pastoris promoters for heterologous protein production. J Biotechnol 150:519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.09.957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vogl T, Glieder A. 2013. Regulation of Pichia pastoris promoters and its consequences for protein production. N Biotechnol 30:385–404. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2012.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Huang M, Gao Y, Zhou X, Zhang Y, Cai M. 2017. Regulating unfolded protein response activator HAC1p for production of thermostable raw-starch hydrolyzing α-amylase in Pichia pastoris. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 40:341–350. doi: 10.1007/s00449-016-1701-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vogl T, Fischer JE, Hyden P, Wasmayer R, Sturmberger L, Glieder A. 2020. Orthologous promoters from related methylotrophic yeasts surpass expression of endogenous promoters of Pichia pastoris. AMB Express 10:38. doi: 10.1186/s13568-020-00972-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Garrigós-Martínez J, Vuoristo K, Nieto-Taype MA, Tähtiharju J, Uusitalo J, Tukiainen P, Schmid C, Tolstorukov I, Madden K, Penttilä M, Montesinos-Seguí JL, Valero F, Glieder A, Garcia-Ortega X. 2021. Bioprocess performance analysis of novel methanol-independent promoters for recombinant protein production with Pichia pastoris. Microb Cell Fact 20:74. doi: 10.1186/s12934-021-01564-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chang CH, Hsiung HA, Hong KL, Huang CT. 2018. Enhancing the efficiency of the Pichia pastoris AOX1 promoter via the synthetic positive feedback circuit of transcription factor Mxr1. BMC Biotechnol 18:81. doi: 10.1186/s12896-018-0492-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vogl T, Ruth C, Pitzer J, Kickenweiz T, Glieder A. 2014. Synthetic core promoters for Pichia pastoris. ACS Synth Biol 3:188–191. doi: 10.1021/sb400091p [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Portela RMC, Vogl T, Kniely C, Fischer JE, Oliveira R, Glieder A. 2017. Synthetic core promoters as universal parts for fine-tuning expression in different yeast species. ACS Synth Biol 6:471–484. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. De Schutter K, Lin Y-C, Tiels P, Van Hecke A, Glinka S, Weber-Lehmann J, Rouzé P, Van de Peer Y, Callewaert N. 2009. Genome sequence of the recombinant protein production host Pichia pastoris. Nat Biotechnol 27:561–566. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental methods, Tables S1 to S4, and Figures S1 to S6.

Data Availability Statement

All data in the paper will be provided by authors upon request.