Abstract

Introduction

Patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) can experience intermittent claudication, which limits walking capacity and the ability to undertake daily activities. While exercise therapy is an established way to improve walking capacity in people with PAD, it is not feasible in all patients. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) provides a way to passively induce repeated muscle contractions and has been widely used as a therapy for chronic conditions that limit functional capacity. Preliminary trials in patients with PAD demonstrate that stimulation of the leg muscles using a footplate-NMES device can be performed without pain and may lead to significant gains in walking capacity. Studies, to date, have been small and have not been adequately controlled to account for any potential placebo effect. Therefore, the current trial will compare the effect of a 12-week programme of footplate-NMES with a placebo-control on walking capacity (6 min walking distance) and other secondary outcomes in patients with PAD.

Methods and analysis

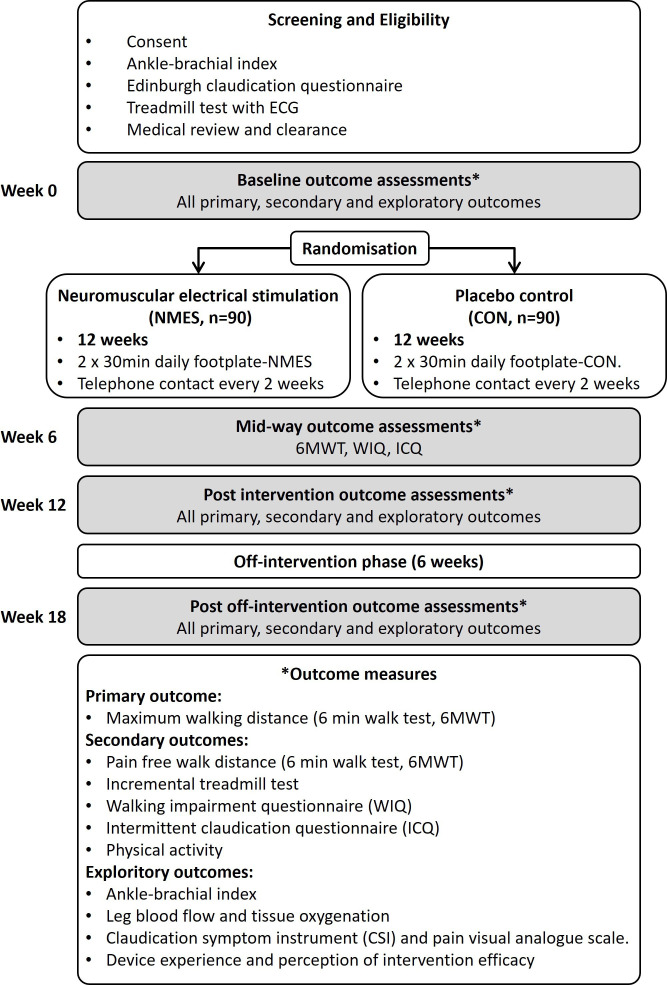

The Foot-PAD trial is a double-blinded, randomised placebo-controlled trial to determine the effect of a 12-week home-based programme of footplate NMES on walking capacity in people with PAD. This is a single-centre trial with numerous recruitment locations. A total of 180 participants with stable PAD and intermittent claudication will be randomly assigned (1:1 ratio) to receive either footplate-NMES (intervention condition) or footplate-placebo (control condition) for two 30 min periods each day for 12 weeks. The footplate-NMES device will deliver stimulation sufficient to induce contraction of the leg muscles and repeated plantar and dorsiflexion at the ankles. The footplate-placebo device will deliver a momentary low-intensity transient stimulation that is insufficient to induce contraction of the leg muscles. Outcomes will be assessed at baseline (week 0), mid-intervention (week 6), postintervention (week 12) and 6 weeks after the completion of the intervention (week 18). The primary outcome is walking capacity at week 12, measured as maximum walking distance during the 6 min walk test. Secondary outcomes will include pain-free walking distance during the 6 min walk test; pain-free and maximum walking time during a graded treadmill walking test; disease-specific quality of life (Intermittent Claudication Questionnaire), self-reported walking impairment (Walking Impairment Questionnaire) and accelerometer-derived physical activity levels. Exploratory outcomes will include the Ankle-Brachial Index; leg vascular function; perception of device-use experience and symptom monitoring throughout the trial using the Claudication Symptom Instrument and a pain Visual Analogue Scale.

Ethics and dissemination

The Foot-PAD trial has received ethics approval from the Human Research Ethics Committees of Queensland Health Metro North Hospital and Health Service (78962) and the University of the Sunshine Coast (A21659). Regardless of the study outcomes, the study findings will be published in peer-reviewed scientific journals and presented at scientific meetings.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12621001383853.

Keywords: Exercise Test, Quality of Life, VASCULAR MEDICINE, VASCULAR SURGERY, Electric Stimulation Therapy

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The primary outcome of this study, maximum walking distance during the 6 min walk test, is a meaningful clinical parameter that is strongly associated with quality of life and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in people with peripheral artery disease (PAD).

The outcome measurements included in this study provide a range of objective, subjective and exploratory data, which will provide a comprehensive understanding of potential benefits of neuromuscular electrical stimulation therapy in people with PAD.

Devices used in the control and interventional groups will look identical, and participants and outcome assessors will be blinded to the group allocation throughout the trial.

Introduction

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is an atherosclerotic condition characterised by the stenosis or occlusion of one or more lower limb arteries supplying blood to the legs. The prevalence of PAD increases with advancing age from 3% to 5% in adults younger than 60 years, to an estimated ≥25% in those over the age of 80.1,3 It has been estimated that approximately 236 million people globally have PAD, and the prevalence of PAD has increased by 17% since 2010, which is reflective of an ageing population.2 4 Hospitalisation rates and the presence of comorbidities are elevated in patients with PAD, with studies demonstrating the risk of hospitalisation to be more than twice that of people without PAD.5 Worldwide, PAD-related treatment and associated hospitalisation impose a significant economic strain on healthcare systems with studies indicating annual costs ranging from US$6 to US$21 billion annually.6 7

Intermittent claudication (IC) is the most well-recognised symptom reported by patients with PAD, although a range of other symptoms are also reported and many patients are asymptomatic.8,11 Irrespective of symptoms, walking capacity and quality of life are substantially reduced in people with PAD.12,15 Patients with PAD and IC avoid physical activity because of pain and their poor walking capacity,11 16 17 and physical inactivity is associated with elevated mortality, independent of disease severity and age.18 19 Therefore, improving walking capacity is a primary treatment goal for patients with PAD.

Treatment for PAD includes the medical management of symptoms and cardiovascular risk, exercise therapy and in cases of severe or lifestyle-limiting disease, lower limb revascularisation procedures may be indicated (eg, endovascular or open surgical procedures).20 Supervised exercise therapy is a class IA recommendation in several international guidelines for improving walking capacity in patients with PAD.21,24 However, patients with PAD typically find exercise difficult, reporting a paradoxical situation where they are advised to exercise, but their leg pain discourages or prevents them from doing so. As a result, adherence to exercise programmes is often poor, with drop-out rates of up to 45% in programmes conducted in clinical settings.25 26 Patients also often fail to adhere to home exercise instruction and interventions.27 These findings highlight the need for pain-free, accessible therapeutic approaches that will reduce symptoms and enable people with PAD to be more physically active.

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) is an established therapy for the treatment of muscle impairment associated with various musculoskeletal, neurological, pulmonary and cardiovascular conditions.28 29 NMES consists of the application of an electrical current to produce contraction of stimulated muscles while the participant is in a rested state. Muscle contraction triggered by an NMES device is the result of the depolarisation of motor neuron axons and their branches. This can be achieved in several ways, including direct stimulation over the superficial muscle belly via self-adhesive surface electrodes or indirectly over motor nerves.30 31 The current trial will use a commercially available footplate-NMES device which delivers an indirect stimulation via rubberised foot pads to the plantar surface of the feet while the participant is in the seated position.

Evidence, to date, suggests that NMES is well tolerated and may have both functional and haemodynamic benefits for patients with PAD. A systematic review of non-invasive therapies for PAD identified three small trials (N=40 participants) of different NMES devices and reported that NMES of the leg muscles led to a 34%–150% increase in treadmill walking capacity, measured at 4–8 weeks compared with baseline.32 Preliminary studies (without control) that assessed the effect of a 6-week footplate NMES intervention in patients with PAD, demonstrated a 46% improvement in maximal walking distance (p<0.001), and a 71% improvement in pain-free walking distance (PFWD) (p<0.001) during a constant-load treadmill test.33 During a subsequent randomised trial of 42 patients that compared supervised exercise alone versus exercise plus home-based NMES, the addition of NMES led to a greater improvement in treadmill PFWD (mean change: 40.4 m vs 7.5 m; p=0.012).33 Analysis of compliance diaries completed by all participants showed a mean adherence rate to NMES device use of 97% (range 81%–100%) over the intervention period. It has also been demonstrated that an acute bout of NMES induces an increase in femoral arterial blood flow by 140%, in the absence of measurable muscle ischaemia or pain.34 These findings suggest that patients with PAD can use NMES without experiencing pain, and considering the high level of intervention adherence, NMES therapy demonstrates a high level of acceptability for patients and supports the potential effectiveness of this treatment modality. However, as highlighted by Jéhannin et al in their systematic review,35 evidence, to date, is limited to a small number of randomised-controlled trials that are characterised by small sample sizes and a high risk of bias. Available studies have not adequately controlled for the potential placebo effect of using an NMES device, and, there has been no attempt to investigate the time course of changes with NMES. Thus, we now present a protocol for the Foot-PAD trial: a double-blinded, randomised placebo-controlled trial to determine the effect of a 12-week home-based programme of footplate NMES on walking capacity in people with PAD.

Objectives

The primary objective of this trial is to compare the effect of a 12-week home-based programme of NMES using a commercially available footplate device against a placebo control footplate device (CON), in addition to usual care, on change in maximum walking distance during the 6 min walk test (6MWT), measured at baseline and week 12 (postintervention), in people with PAD.

The secondary objectives of the trial include the assessment of changes in (1) PFWD during the 6MWT, (2) pain-free and maximum walk time during an incremental treadmill walking test, (3) disease-specific quality of life assessed with the Intermittent Claudication Questionnaire (ICQ), (4) self-reported walking impairment/capacity assessed with the Walking Impairment Questionnaire (WIQ) and (5) physical activity levels measured objectively using a thigh-mounted triaxial accelerometer.

The trial will also include exploratory objectives aimed at providing measures of intervention adherence, to determine participant satisfaction and perception of treatment/placebo effects, to provide insight into potential physiological mechanisms of action and to establish the short-term maintenance of intervention effects. The exploratory objectives of the trial include the assessment of changes in (1) Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI), (2) limb blood flow (measured with strain gauge plethysmography) and tissue oxygenation (measured with near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS)) assessed at rest and during reactive hyperaemia, (3) adherence to intervention device use (NMES or CON) assessed with a daily diary and automated device data logging, (4) severity of symptoms measured with the Claudication Symptom Instrument (CSI) and a pain Visual Analogue Scale and (5) device experience and perception of intervention efficacy (NMES or CON). To determine the short-term maintenance of treatment effects, all outcome measures will be repeated at week 18, that is, 6 weeks following the completion of the 12-week intervention phase. Finally, a safety assessment will be conducted including a formal evaluation of all related and unrelated adverse events (AEs) throughout the study.

Methods and analysis

Study design

The Foot-PAD trial is a parallel-group, double-blinded, randomised placebo-controlled study (figure 1). All eligible participants will continue to receive usual care and medical advice from their local doctor and vascular surgeon, and they will be randomly allocated to receive either the NMES or CON interventions, which will be undertaken for two 30 min periods each day for 12 weeks. This will be followed by a 6-week off-intervention phase to assess the short-term maintenance of treatment effects. Outcome measures will be assessed at baseline (week 0), midway through (week 6) and at the end of the intervention period (week 12) and again at the end of the 6-week off-intervention phase (week 18). In addition, participants will be contacted by telephone throughout the intervention period (weeks 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12) to monitor and support intervention adherence. In accordance with Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials, a schedule of participant enrolment, intervention and assessments is presented in table 1.36

Figure 1. Overview of the Foot-PAD trial. CON, placebo control condition; NMES, neuromuscular electrical stimulation.

Table 1. Schedule of participant assessments.

| Milestones | Activity | Prescreen | Screen | Baseline(preintervention) | Mid-intervention | Postintervention | Post off-treatment period |

| Week | −4 to −1 | −1 | 0 | 6 | 12 | 18 | |

| Visit (time point) | 1 | 2 | 3–4 | 5 | 6–7 | 8–9 | |

| Recruitment | Patient identification | X | |||||

| Prescreen checklist for eligibility | X | ||||||

| Enrolment and screening | Consent | X | |||||

| Confirm eligibility criteria (ABI, ECQ) | X | ||||||

| Demographics and health history | X | ||||||

| Blood pathology tests | X | ||||||

| Medical review familiarisation, randomisation | Treadmill walk test with ECG, medical review | X | |||||

| Familiarisation with 6 min walk and vascular tests | X | ||||||

| Randomisation | X | ||||||

| Set up and familiarisation with intervention device | X | ||||||

| Interventions | Daily footplate NMES (weeks 1–12) |

|

|||||

| Daily footplate placebo CON (weeks 1–12) |

|

||||||

| Off-treatment | Off-treatment follow-up period (weeks 13–18) |

|

|||||

| Primary outcome | 6 min walk test | X | X | X | X | ||

| Secondary outcomes | Quality of life and function (WIQ, ICQ) | X | X | X | X | ||

| Treadmill walking test | X | X | X | ||||

| Physical activity (7-day accelerometer) | X | X | X | ||||

| Exploratory outcomes | ABI | X | X | X | |||

| Leg blood flow and vascular function | X | X | X | ||||

| Monitoring and compliance | Symptoms (CSI, VAS) (weeks 0, 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18) |

|

X | ||||

| Device experience (weeks 1 and 12) | X | X | |||||

| Device diary and data log (daily, weeks 1–12) |

|

||||||

| Telephone monitoring and support, unblinded(weeks 1, 3, 6, 9, 12) |

|

||||||

All participants will continue to receive usual care and medical advice from their general practitioner (local doctor) and vascular surgeon, and they will be randomly allocated to the NMES programme () or placebo controlCON programprogramme () for 12 weeks. Outcome measures will be assessed at baseline (week 0), midway through (week 6) and at the end of the intervention period (week 12), and again at the end of the 6-week off-intervention phase (week 18). The six6 min walk test and the treadmill walking test will always be conducted during separate visits at each assessment time point. Telephone monitoring calls will be made at weeks 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12.

ABI, Ankle-Brachial Index; CONplacebo controlCSI, Claudication Symptom Instrument; ECQ, Edinburgh Claudication Questionnaire; ICQ, Intermittent Claudication Questionnaire; NMESneuromuscular electrical stimulationVAS, Visual Analogue ScaleWIQ, Walking Impairment Questionnaire

Study participants and recruitment

The Foot-PAD trial will enrol 180 participants with PAD and IC. Participant recruitment and data collection commenced in February 2021 and is anticipated to be completed by the end of 2024. Preliminary findings are expected to be presented in early 2026. This is a single-centre trial with numerous recruitment locations across metropolitan and regional areas of Southeast Queensland in Australia. Participants will be recruited through the vascular units of two major public health service regions (Sunshine Coast and Brisbane Metro North Hospital and Health Service regions of Queensland, Australia), through private vascular clinics, and through community sources and advertising. Participant eligibility will be assessed in accordance with the following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Inclusion criteria

-

Clinical diagnosis of PAD with IC by a vascular surgeon, confirmed with:

Positive Edinburgh Claudication Questionnaire (ECQ).

Resting ABI≤0.9; OR positive walking claudication test (fall in ankle pressure >30 mm Hg (or 20%), following treadmill walking test).

18 years of age or older.

Able to understand and communicate in English sufficient to complete the informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Walking distance limited by symptoms other than IC or leg discomfort during initial screening treadmill walking test, for example, angina, general fatigue, back pain, shortness of breath.

Critical limb ischaemia including rest pain, arterial ulcers (tissue loss) or gangrene of one or both legs or feet.

Severe disease requiring surgical or endovascular intervention.

Previous lower limb or foot amputation.

Plantar wounds, including broken or bleeding skin, or ulcers.

Any implanted electronic, cardiac or defibrillator device.

Being treated for lower limb deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or potential presence of DVT based on presentation (ie, pain, swelling, tenderness, heavy ache, warm skin and redness of lower limb).

Pregnant or intending to become pregnant during the trial period.

Has participated in a supervised exercise programme within the previous 3-month period.

Has used any form of lower limb NMES therapy within the previous 3 month period.

Has previously used at any time a Revitive footplate NMES device.

Unwilling or unable to engage with the technology required for the intervention.

Terminal illness or other medical condition that may affect the ability to complete the trial, or deemed unfit to undertake the trial procedures (eg, where walking tests may be contraindicated because of an existing or unstable medical condition that may be made worse or exacerbated by participation).

Consent

Prior to any screening assessments, participants will be required to provide their informed consent to participate in the study which will occur at the commencement of the initial study visit (visit 1). A trained study staff member authorised by the principal investigator (PI) will explain the details of the study and procedures and obtain informed consent. Participants will be informed that they have an equal chance of being randomised to the NMES or CON groups. Participants who are willing to participate in the study will be asked to voluntarily provide their written consent by signing the consent form. The study staff member will also sign and date the consent form. A copy of the information sheet and signed consent form will be given to participants along with a withdrawal of consent form.

Screening and enrolment

Screening and enrolment procedures will be carried out across two study visits (see table 1). As part of the initial study visit (visit 1), screening procedures will be undertaken to ensure that participants meet the inclusion criteria for the study. Assessments include the ABI, confirmation of IC symptoms using the ECQ, collection of medical history and demographic data, anthropometric measurements (eg, height, weight and calf circumferences), and referral for blood pathology testing for cardiovascular risk assessment and medical review (full blood count, electrolytes and liver function tests, cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein/low-density lipoprotein, creatinine, glucose, estimated glomerular filtration rate, haemoglobin A1c and C reactive protein). Participants will also undergo a medical review by the study medical practitioner (visit 2). During this visit, participants will undertake an incremental treadmill walking test with medical supervision using the same graded protocol as described in the study outcomes section. Prior to the test, participants will rest in the supine position for baseline measures of ABI, and a recording and review of the resting ECG. Participants will receive standardised encouragement and the walking test will continue until the point the participant does not want or does not feel able to continue due to lower limb discomfort, or any other reason. Following the treadmill test, participants will return immediately to the supine position for postexercise measures of the ABI and monitoring. Based on their review of medical history and the screening assessment data, the study medical practitioner will be required to provide clearance for each participant to enter the trial.

Randomisation

A random sequence for group (NMES vs CON) allocation will be generated prior to commencement where consecutive participant enrolment codes are randomly assigned to device codes. Device codes will be randomly generated, and it will not be possible for participants or staff to differentiate between NMES or CON devices by this code. Randomisation will be conducted using a secure, auditable, independent web-based randomisation system (SealedEnvelope.com) without stratification. Randomisation will be in a 1:1 ratio and random blocks of 4–8 participants will be used to ensure equal group numbers throughout the recruitment and enrolment period. Randomisation will occur at the completion of baseline outcome assessments (visit 4: see table 1) to ensure there is no impact of group allocation on baseline measures. Allocation concealment will be ensured prior to randomisation as the SealedEnvelope service will not release the device code until the participant has completed all baseline measurements.

Blinding

Participants, investigators, outcome assessors and data analysts will be blinded to the intervention allocation throughout the trial. The following measures are in place to maintain the ‘double-blinded’ nature of the trial. First, the description of the sensations that may be experienced during device use will be the same for all participants. Prospective participants will be informed of the range of sensations, from light tingling and feelings of pins and needles, to noticeable muscle twitches and contractions in the muscles of the feet and legs. Second, familiarisation and ongoing support with the intervention and control devices will be managed by an unblinded staff member, and this person will provide feedback and cues to the participant that their sensations and feelings in response to using the device are as expected or ‘normal’. Any enquiries regarding the device during the trial period will only be handled by the unblinded staff member. Lastly, the packaging, user instructions and appearance of the devices will be identical. Each device will be labelled with a randomly allocated device code, and a log of device codes against the serial numbers of each device will be maintained by the unblinded staff member, who is not involved in the collection or analysis of trial outcome data. Unblinding of a study participant’s intervention allocation will only occur if it is necessary as part of the investigation or treatment of an AE.

Interventions

All participants will continue to receive usual care and medical advice from their local doctor and vascular surgeon throughout the study. While usual care for PAD will not be altered by this protocol, on consent to the study each participant’s local doctor and vascular surgeon will be contacted to request to provide their best possible medical care throughout the study. In addition to usual care, eligible participants will be randomised in equal proportions (1:1) to receive either a home programme of footplate-NMES (intervention condition) or footplate-CON (placebo condition).

Participants in the NMES group will be provided with a Revitive Medic Coach which is a CE Marked and Therapeutic Goods Administration approved Class IIa, NMES medical device intended to actively improve circulation in the lower limbs to alleviate symptoms associated with poor circulation due to age, sedentary lifestyle, PAD and chronic venous insufficiency. Participants use the device while in the seated position. The device causes muscle contraction by applying electrical stimulation to the soles of the feet via large conductive rubber footpad electrodes. Participants will also be provided with an Android smartphone preinstalled with the Revitive Controller Application (App) to control the device and log device-use data. The device is preprogrammed with a standard stimulation programme that runs for 15 min and then repeats. The programme comprises a series of stimulation patterns that last approximately 60 s each. Each pattern (or waveform) is made up of a sequence of bursts that are composed of stimulation pulses delivered in cycles at a range of stimulation frequencies (20–44 Hz) and durations (450–970μs).

The intensity of electrical stimulus can be varied from level 1 to level 99, which corresponds with an increase in the electrical current. Optimal intensity level to induce muscle contractions varies from person to person and may be dependent on factors including foot plantar surface skin hydration. The user controls the intensity using the Revitive App and sets an intensity that is sufficient to induce repeated contraction and ankle plantar/dorsi flexion, which in turn causes ‘rocking’ of the footplate device. When first using the NMES device during the familiarisation visit (visit 4), baseline sensory and motor thresholds will be established by systematically increasing the stimulation intensity in increments of one unit while the participant provides verbal sensory feedback. The minimal intensity at which the participant can clearly feel electrical stimulation will be recorded as the sensory threshold; and the intensity that produces visible muscle twitches will be the motor threshold. The stimulation intensity will be adjusted to produce visible but non-painful contraction of the lower limb musculature at twice the individual motor threshold or as much as the participant can tolerate as comfortably, whichever is greater (ie, the therapy target threshold). Participants will be encouraged to increase the intensity of the NMES intervention as tolerated throughout the intervention period. Participants will be asked to use the device for two 30 min sessions per day, at the target therapy threshold intensity sufficient to evoke lower limb muscle contractions. Adherence will be recorded in a device use diary and collected via the Revitive App.

Participants in the CON group will be provided with a placebo (sham) device which is a modified Revitive Medic Coach. The external appearance of the placebo device is identical to the active intervention device, however, the stimulation protocol is modified with a stimulation intensity cap. This intensity cap will only enable stimulation to a level of 5 (out of 99) for the first minute of use, then level 2 for the second minute, then to level zero for the remaining duration of the session. The intensity reading on the device and Revitive App will range between 1 and 99 to mimic the active intervention device for the entire session. Participants in the CON group will also be asked to use the device for two 30 min sessions each day, and adherence data will be recorded in a device use diary and collected via the Revitive App.

Modifications to interventions

If participants indicate that they are unable to tolerate extended periods of sitting or device use, modifications to the intervention will be guided by the unblinded support staff member, and participants will be instructed that they are able to break the total duration into shorter sessions each day (eg, 6×10 min). If device use causes irritation to the skin, participants will be instructed to alter the frequency and intensity of stimulation. Participants will be asked to note any skin irritation in the device use diary and to inform the research team. If skin irritation persists, the participant will be reviewed by the trial medical practitioner who will advise on whether the intervention should be discontinued, which would be reported as an AE of special interest (AESI). In such cases, study participants will be retained in the trial whenever possible to enable follow-up data collection and prevent missing data for intention-to-treat-based analyses.

Adherence to interventions

Strategies are incorporated into the protocol to monitor and promote adherence to the trial interventions. The importance of accumulating the recommended duration of treatment (ie, 60 min per day) will be explained to the participants in the participant information sheet and consent form and during the introductory familiarisation session. Telephone support will be available 24 hours/7 days and participants will be encouraged to contact the research support team at any time to discuss questions or difficulties they may have with the intervention device. Participants will be asked to keep a daily diary of self-reported device use. Participants will be contacted by telephone through the intervention period (weeks 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12) and asked to report their average device use and will be supported to maintain or improve their adherence as required. Device use data will also be logged and objectively assessed using the Revitive App and will serve as a secondary outcome measure for intervention adherence. For each session, this information will be logged every 60 s and will include the average intensity and duration of stimulation and whether the stimulation was sufficient to induce rocking of the device (ie, plantar and dorsiflexion). Participants will be made aware in the participant information sheet and consent form and at the commencement of the trial that device use is monitored using the mobile phone App; however, these data will not be revealed or discussed with participants throughout the trial to maintain appropriate blinding of these data as a measure of adherence. Where there are missing App data related to technical issues (eg, interrupted internet connection), the participant-reported device use diary data will be used in lieu of missing data for the assessment of adherence.

Study outcomes

As outlined in table 1, outcome measures will be assessed at baseline (week 0), midway through (week 6), at the end of the intervention period (week 12), and again at the end of the 6-week off-intervention phase (week 18). During weeks 0, 12 and 18, participants will carry out assessment over two visits, to ensure they have sufficiently recovered between walking tests. For the follow-up assessments at weeks 6, 12 and 18, the assessment window may be extended by up to 7 days to accommodate unforeseen circumstances (eg, participant illness). All outcome measures will be conducted at the VasoActive Laboratory at the University of the Sunshine Coast. All staff involved in the assessment of study outcomes will be fully trained and credentialled to carry out assessments in line with standard operating procedures, and where possible the same personnel will conduct outcome assessments throughout the trial. Outcome measures include primary and secondary outcomes, as well as exploratory outcomes that will provide insight into the mechanisms of any treatment effects and further information about the time course of any change in symptoms throughout the trial.

Primary outcome

The 6MWT will be conducted at weeks 0, 6, 12 and 18. The primary outcome for this trial will be change in maximum walking distance during the 6MWT between baseline and week 12. As per standard procedures, a course of 30 m in length is marked out in a covered area with cones at each end.37 Participants will be asked to walk up and down the course for 6 min and complete as many laps as possible. Chairs will be placed every 10 m along the course for participants to sit and rest if their symptoms become intolerable; however, the timing continues and participants will be instructed to resume walking as soon as possible. The 6MWT is a validated and widely used test that closely represents walking capacity in daily life in people with PAD.38 Maximum walking distance during the 6MWT strongly correlates with a range of clinical outcomes including patient-reported quality of life, free-living physical activity levels and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with PAD.38,41 Furthermore, the 6MWT is known to improve in response to therapeutic interventions in people with PAD and is not associated with a learning effect when repeated testing is involved.42 Nevertheless, participants will be familiarised with the 6MWT in this trial using a practice test.43

Secondary outcomes

Additional 6MWT endpoints

The change in maximum walking distance (MWD) in the 6MWT from baseline to week 6 and week 18 will be reported as secondary outcomes. Change in PFWD during the 6MWT for all time points will also be reported as a secondary outcome for the study. Participants will be asked to indicate the onset of claudication or leg discomfort during the test which will be marked on the walking course and recorded as the PFWD. They will also be asked to rate the severity of claudication for each leg every 60 metres (ie, the start of each lap) using a hand-signal in accordance with the claudication severity scale (0 no pain, 1 mild, 2 moderate, 3 intense, 4 maximal).

Graded treadmill walking test

A graded treadmill walking test including measures of maximum walk time (MWT) and pain-free walking time (PFWT) will be performed at weeks 0, 12 and 18. The Gardner-Skinner protocol will be used, which was specifically developed for the assessment of walking capacity in patients with PAD and is widely used in clinical trials and practice.44 45 The treadmill will start at 3.2 km/hour at a 0% incline, and then every 2 min the gradient of the treadmill will increase by 2%. Participants will be asked to indicate the onset of claudication or leg discomfort, which will be recorded as the PFWT. They will then be asked to rate the severity of leg symptoms using the claudication scale for each leg every 60 s. The test will continue until the point the participant does not want or does not feel able to continue due to claudication (or for any other reason), which is recorded as the MWT. At the end of the test, participants will be asked to rate their symptoms in each leg using the claudication scale, and to provide a rating of their general perceived exertion using the modified Borg scale.46 Graded (incremental) walking tests have been used extensively in our studies previously and are more reliable than constant load treadmill tests for determining walking capacity in patients with PAD.4547,50 Participants will be familiarised with the graded treadmill walking test during the screening visit conducted under medical supervision.

Quality-of-life assessment

Disease-specific quality of life will be assessed using the ICQ at weeks 0, 6, 12 and 18. The ICQ is a self-administered tool consisting of 16 items that focus on limitations imposed by claudication while performing various tasks, such as walking specific distances or performing activities of daily living.51 The validity of the ICQ has been established against other functional and quality-of-life assessments and is sensitive to changes with various treatments.12 The instrument is scored by summing the participant responses to individual items, which are all equally weighted, and transformed to a 0–100 composite score, where 0 is the best score. The composite score and individual question scores will be used for analysis.

Self-reported walking impairment

Self-reported walking impairment (capacity) will be assessed using the WIQ at weeks 0, 6, 12 and 18. The WIQ is a PAD-specific measure of self-reported difficulty during walking with three domains: walking distance, walking speed and stair climbing.52 Each domain is scored on a scale from 0 to 100 (100 indicating the best possible score). The WIQ has been validated in several large studies, correlating with treadmill measures of walking capacity.52 53

Physical activity levels

Physical activity levels will be objectively assessed using an activPAL accelerometer (PAL Technologies, Glasgow, UK) at weeks −1 (prior to baseline measures), 12 and 18. This is a thigh-mounted triaxial accelerometer that enables the assessment of body position (ie, sitting/lying vs standing) and walking activity from continuous recordings (20 Hz) that are logged on the accelerometer. The small accelerometer unit is wrapped in a waterproof sleeve and attached to the right thigh of the participant (mid-line; one-third of the distance from the inguinal fold to the top of the patella) using a waterproof adhesive dressing.54 The accelerometer will be worn continuously by the participant for eight consecutive nights, to ensure seven full days of data capture. Data will be screened to ensure there is a minimum of five valid days of data according to the following criteria: (a) >500 steps taken in a day; (b) <95% of time spent doing any one activity and (c) 10+ hours of waking wear data in a day.55 The primary measure of physical activity will be average steps per day. Other measures will include total sedentary time, and time spent completing low, moderate and vigorous levels of activity (stepping cadence bands), sit-to-stand movements and the number of walking bouts for each upright event. During the 7-day monitoring period, participants will also keep a brief daily physical activity diary to record periods of sleep, work and structured exercise. The activPAL accelerometer has been reported to be reliable and valid for the assessment of walking, body posture and sedentary behaviour during free-living activity,56,58 and when used in patients with PAD.12 59

Exploratory outcomes

Ankle-Brachial Index

ABI of both legs will be measured at weeks 0, 12 and 18. After resting in a supine position for 10 min, brachial and ankle blood pressures will be measured. Brachial blood pressures will be measured in the right and left arm using an automated blood pressure monitor (Connex 3400 SureBP, Welch Allyn, Skaneateles Falls, USA).60 Systolic blood pressure of the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arteries at the left and right ankles will also be measured using a manual cuff sphygmomanometer (DS55 Sphygmomanometer, Welch Allyn, Skaneateles Falls, USA) and handheld 8 MHz Doppler ultrasound probe (SD2 Huntleigh Dopplex, Huntleigh Healthcare, Cardiff, Wales). Measurements will be made in a standardised order in triplicate. The average of the closest two recordings at each artery will be recorded. The ABI for each leg will be calculated by dividing the higher pressure of the posterior tibial artery or dorsalis pedis artery value by the highest brachial artery value obtained from either side.48

Limb blood flow and tissue oxygenation

Assessments of limb blood flow (measured with strain gauge plethysmography) and tissue oxygenation (measured with (NIRS)) will be undertaken at rest and during reactive hyperaemia in both legs at weeks 0, 12 and 18. After 10 min of supine rest, participants will undergo resting measures of leg blood flow and tissue oxygenation. Following resting measures, a thigh cuff is inflated to a supra-systolic pressure (200 mm Hg) for 5 min. On release of the cuff pressure (to 60 mm Hg), the measures of leg blood flow and tissue oxygenation are repeated to capture the peak (reactive hyperaemia) responses. This is a standard test of vascular function that is commonly used and highly reliable in patients with and without PAD.61 62 Where participants have previously had a revascularisation procedure involving a vascular graft or stenting of the femoral or popliteal arteries, the reactive hyperaemia test will not be performed in that limb. Measures of leg blood flow and tissue oxygenation will be carried out in accordance with the strain gauge plethysmography and NIRS sections below.

Strain gauge plethysmography

This technique requires the veins to be temporarily occluded using a thigh cuff (CC17, contoured leg cuff, Hokanson, Bellevue, USA) and rapid inflator (E20 Rapid Cuff Inflator and AG101 Inflator Air Source, Hokanson, Bellevue, USA) causing a subtle increase in limb volume.63 64 The rate of increase in limb volume is used to calculate the rate of blood flow into the limb.61 65 The strain gauge (EC6 Plethysmograph and MSGLIMB Strain Gauge, Hokanson, Bellevue, USA) will be calibrated so that an increase of one mV is equal to a 1% increase in leg volume (ie, mL/100 mL). Participants will also be fitted with three ECG electrodes (lead II configuration) for the assessment of heart rate and the identification of cardiac cycles during the assessment of blood flow. For each measurement, the thigh cuff will be inflated to a light pressure (60 mm Hg) to occlude venous flow and determine the rate of increase in leg volume and blood flow. Triplicate measures of blood flow, each separated by 30 s, will be made at rest, and a single measure during the reactive hyperaemia period immediately after the vascular responsiveness test.

Near-infrared spectroscopy

NIRS-derived signals for oxygenated (O2Hb), deoxygenated (HHb) and total haemoglobin (THB=O2Hb+HHb) as well as tissue oxygen saturation (StO2=O2Hb/THB×100) will be continuously recorded during rest, cuff-occlusion and for 120 s following cuff-release with a non-invasive NIRS device (Portalite, Artinis Medical Systems BV, Zetten, Netherlands).66 The method used for acquiring NIRS data has been previously published67 and is briefly outlined here. The NIRS probe will be affixed to the calf over the belly of the medial gastrocnemius muscle in line with the widest calf circumference. To ensure measurement consistency, the location of the device will be measured and recorded in relation to anatomical landmarks. The device will be secured using an opaque adhesive dressing to shield against ambient light contamination. Signal data will be exported and used to identify baseline (the average over 60 s prior to occlusion) minimum (during cuff-occlusion) and maximum (post cuff-release) values from which the magnitude and rate of the reactive hyperaemia response will be calculated.67 68

Limb blood flow and tissue oxygenation measured during device use

This assessment will be undertaken at week 18 to determine the acute haemodynamic effects of the active (NMES) and placebo (CON) stimulus, respectively, in each group. Following the resting and reactive hyperaemia measures, participants will undergo measures of blood flow and tissue oxygenation in response to a short (5 min) period of device use using the device they were allocated for the intervention period. Measures will be made in the participant’s most symptomatic limb (or that with the lowest ABI) while in the seated position, following similar procedures we have reported previously.61 65 69 Participants will be instrumented with the NIRS probe and plethysmography strain gauge as described above. Measures will be made at rest and then immediately on the cessation of device use.

Monitoring of symptoms and device use experience

Participants will be sent an online link by email to complete the following self-assessment questionnaires at weeks 0, 1, 3, 6, 9, 12 and 18: (1) CSI, which is a 5-item validated survey to establish the extent to which patients experience different presentations of claudication (ie, pain, numbness, heaviness, cramping and tingling).70 Analysis will include the CSI composite score and individual question response; (2) Visual Analogue Scale question asking participants to rate the average severity of their lower limb pain or discomfort. In addition, the Revitive App will be programmed to ask participants to rate the impact of their key symptom (ie, leg pain and discomfort) on daily activities during the last few days. This question will be presented to participants every 2 weeks during the intervention period (ie, weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12) and responses will be uploaded with the device-use data (adherence data). Finally, participants will complete a device experience questionnaire to determine the ease of using the device (NMES or CON) and perceived device efficacy. This item will be used to assess whether the blinding of the placebo intervention is effective throughout the intervention period and will be completed at the end of weeks 1 and 12 only.

Statistical analysis

Full details of the planned analyses are included in the Statistical Analysis Plan which will be made publicly available on the completion of data collection prior to the commencement of analysis (https://doi.org/10.25907/00855) and a summary is provided here. Reporting will follow the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement guidelines. The primary analysis will be performed based on the intention-to-treat principle, where all participants will be analysed as per their group allocation, regardless of the treatment they received. Sensitivity analyses will be conducted to assess the robustness of the conclusions. Non-compliance and non-adherence will be assessed through per-protocol analyses, including participants with no protocol violations or deviations. Missing data will also be explored, with both completed cases and imputed cases analysed.

Data will be analysed by using Stata V.18 software. The change from baseline in walk distance will be analysed using a linear mixed model with factors for treatment group, time, time-by-group interaction term and subject as a random effect. Baseline walk distance will be included as a covariate, as will a term for the baseline-by-time interaction so that the stronger correlation between baseline and the earlier time point (week 6) does not overemphasise the baseline covariate and then overcorrect later time points. Treatment effects at each post-baseline time point will be estimated using the marginal means. This approach provides a clinically interpretable measure of the treatment effects across the study period and accounts for the correlation structure in repeated measures. Inclusion of the time-by-group interaction gives full flexibility in having different treatment effects at each time point and thus enables estimates of NMES versus CON to be obtained at the 6-week, 12-week and 18-week time points. The primary comparison will be NMES vs CON at the 12-week time point. The comparison of NMES versus CON at the 6-week time point is a secondary endpoint. Participants will repeat all outcome measures (primary, secondary and exploratory) at week 18, that is, following the 6-week off-intervention phase. This postintervention period is included as an exploratory assessment of the short-term maintenance of treatment (NMES and CON) effects on all outcomes.

For all analyses, p<0.05 will be, a priori, considered statistically significant. In addition to the planned analyses, the average device use time will be compared between groups using either an independent samples t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. The analysis of secondary outcomes will be undertaken regardless of whether the primary outcome is statistically significant. Adjustment for multiplicity for secondary outcomes and the Family Wise Error Rate will be undertaken using Hochberg adjustment.

Subgroup analyses will be undertaken to determine the consistency of effects and safety across the study population and to assess the influence of key variables on trial outcomes. Subgroups will include, but not be limited to, age, sex, anatomical site of disease, disease severity and recruitment source (eg, public vs private hospital clinics). Analyses will also include an assessment of outcomes against established minimum clinically important difference (MCID) values. Where relevant MCID values have been established and published for people with PAD, these will be used to guide the interpretation of results during the primary analysis. MCID values established in people without PAD will be considered where appropriate.

Sample size calculation

To date, there have been four published studies of NMES in patients with PAD where maximum walking distance on a treadmill test was reported as the primary outcome3371,73; this includes two pilot studies with no control.33 73 Based on these available studies, the effect size for NMES on maximum treadmill walking distance in patients with PAD ranges from 0.52 to 0.93. There have been no previous studies of the effect of NMES on 6MWT distance in patients with PAD. Previous trials of lower limb NMES in patients with other chronic diseases (eg, heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) where 6MWT distance was the primary outcome indicate a potential effect of ≥30 m with an SD of 90 m.74 75 This provides a small effect size of 0.33. With a required power of 80%, alpha of 0.05, measurements at 2 time points (Baseline, Week 12) an expected correlation over time of 0.7, and an expected effect size of 0.33, and based on a linear mixed effects model, 74 participants would be required in each group. Allowing for ~18% drop-out or non-compliance and non-adherence, 90 participants will be recruited in each group.

Patient and public involvement

The design of the intervention was informed through preliminary studies and pilot investigations including people with and without PAD. Feedback will be provided to all participants at the completion of the trial which will include a summary of trial outcomes, and participants will be informed at that time which intervention group they had been assigned to during the trial. This feedback will be prepared in a brief report and provided in person (or via videoconference) and participants will have the opportunity to ask questions about the trial design, procedures and outcomes. The outcome measures for the trial specifically include an assessment of patient experience and preferences. Where incidental findings are uncovered during the research, these will be discussed with participants.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics, protocol amendments, dissemination and confidentiality

This study is approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees of Queensland Health Metro North Hospital and Health Service (78962) and the University of the Sunshine Coast (A21659). This study will be conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines. In addition, all local and site-specific research and clinical governance approvals have been obtained prior to the enrolment of participants. Written informed consent will be required from all participants upon study enrolment and prior to the collection of study data. Any significant protocol amendments will be approved by the Trial Steering Committee (refer to authors’ contribution section), Actegy Pty Ltd (funder) and the Human Research Ethics Committees.

The study results will be published in peer-reviewed medical and scientific journals and presented at scientific conferences by the authors, regardless of the study outcomes. Authorship will be granted to individuals making a substantial contribution to the design, initiation or conduct of the trial and/or analysis and interpretation of trial data. The trial funder will not be involved in the analysis or interpretation of data and findings.

All individual participant information will be deidentified in the reporting of data and resulting publications or presentations to fully protect the confidentiality of participants. Participants will be informed at the time of consent that reports from the study will be prepared and will be submitted for publication. Participant information will normally be presented as group data. If necessary, information obtained from specific individuals may be presented; however, names will not be used to identify the individuals. Participants will only be identified in such publications by an identification number and possibly their age and sex. All participants will be informed of the group they were allocated to at the end of the trial, and all participants, regardless of group, will be offered a Revitive NMES device to keep at the end of the trial.

Adverse events

Study and non-study-related AEs including any untoward medical occurrence, unintended medical treatment, unreported disease or injury, or any untoward clinical signs (including abnormal laboratory findings) will be recorded throughout the trial. AEs will be graded by the PI or delegate as either (1) mild (tolerated and causing no limitation of usual activities), (2) moderate (causing some limitation of usual activities) or (3) severe (causing inability to carry out usual activities). Furthermore, the PI or delegate will determine the AEs causality in relation to the trial procedures based on the temporal relationship and their clinical judgement. AEs will be classified as being (1) definitely related, (2) probably related, (3) possibly related, (4) unlikely or (5) not related to the study intervention or procedures. The clinical course of each event will be followed until resolution, stabilisation or until it has been determined that the study intervention or participation is not the cause. All logged events will be summarised and reported to the relevant ethics committees and governance agencies as part of the reporting requirements.

AESIs include events that are thought to be potentially associated with the study intervention (NMES/CON) or the disease being studied (PAD) that warrant investigation into the participant’s safety. All AESIs will be investigated by study staff for the purpose of immediate revision of the intervention for safety, or to prompt the participant to be reviewed by their medical practitioner. In the event of an AESI, the PI will be notified immediately. If required, the participant will be directed to receive the appropriate medical attention. If the AESI uncovers a significant safety issue with the protocol or intervention, the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), sponsor, funder and ethics committees will be promptly notified, and the protocol or intervention will be reviewed.

Serious AEs

A serious AE (SAE) is defined as a medical occurrence that either (1) results in death, (2) is life-threatening in the opinion of the attending clinician, (3) requires inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, (4) results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity or (5) is an important medical event in the opinion of the study medical practitioner. All SAEs will be reported within 24 hours of occurrence to all investigators including the TSC, the study funder and the research ethics committees in accordance with National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia guidelines.

An independent medical monitor will be appointed and report to the TSC to investigate any SAEs that may be related to the trial procedures. A safety board will be convened if deemed necessary, for example, where a trend in incidents or events is noted, by the TSC. SAE reports and relevant correspondence will be included in the participant’s case report form and study file. Any SAE that occurs after the study period and is considered to be possibly related to the intervention will also be recorded and reported immediately. Safety assessments will be performed on the intention-to-treat dataset and the per-protocol dataset to determine any effect of treatment allocation (NMES or CON) during the study period on total AEs, SAEs and AESIs.

Data management

All data collected during the trial will be coded and will be stored for a minimum of 15 years. Prospective participants will be assigned a screening number and on consenting to the trial they will be assigned a participant identification code. A coding log will be maintained and kept in a secure location as per the trial management plan and the University of the Sunshine Coast data security policy. Only the PI and authorised personnel will have access to participants’ individual identifiable and sensitive data. Access to the coding log would only occur in the case where further medical history information is required in relation to a specific participant, in case of an emergency (eg, to identify contact for the next of kin), or during the investigation of an AE. Access to the final dataset will be provided to the trial statistician for the purposes of carrying out the planned analyses. Ongoing access to the data will only be available to the research team for the purpose of carrying out related research. On completion of the trial and publications, the funder will be transferred the trial outcome data. This will not include source documents or medical records and will be fully anonymised. All identifiable information will be removed. Participants will be fully informed of this prior to consent.

Trial management

The trial will be overseen by a TSC comprising lead investigators with expertise in vascular surgery and medicine, biostatistics, clinical trial methodology and other relevant individuals as required, all with appropriate clinical and/or research expertise relevant to the design and conduct of the trial. The TSC has the right to appoint new members and co-opt others to add to the integrity of the conduct of the study and analyses. The day-to-day activities of the Foot-PAD trial will be managed by the trial coordinator under the supervision of the PI. The PI will facilitate data quality assurance processes including random internal monitoring of data and trial compliance.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mary M. McDermott MD for her contributions to the manuscript. We also acknowledge the generous support of the University of the Sunshine Coast Clinical Trials Centre.

Footnotes

Funding: The trial activities are funded by Actegy (Funder) as part of a clinical investigation research agreement with the University of the Sunshine Coast (Sponsor). Funding for the trial includes staffing costs for the Trial Coordinator and research assistants, sitting fees for the participation of investigators in the TSC activities and consultancy costs for statistical and medical support as required.

Prepublication history for this paper is available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-093162).

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collaborators: The following investigators are members of the Foot-PAD Trial Group: Karl Schulze, Pankaj Jha, Rebecca Magee, Jill O’Donnell, Daniel Hagley, Daniel McGlade, Amanda Shepherd, Sarah Philpot, Michael Nam, David Lack, Hannah Sudell, Vivienne Moult, Jason Jenkins, Julie Jenkins, Michelle McGrath, Lucy Guazzo, Samantha Peden, Danella Favot, Vanessa Ng, Peter Kamen, Muhammad Raza, Helen Rodgers, Megan Hawkins, Andrew Kwintowski, Sian Campbell, Rachelle Seizovic, Grace Young, Amanda Moore.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Contributor Information

On behalf of the Foot-PAD Trial Group:

Karl Schulze, Pankaj Jha, Rebecca Magee, Jill O’Donnell, Daniel Hagley, Daniel McGlade, Amanda Shepherd, Sarah Philpot, Michael Nam, David Lack, Hannah Sudell, Vivienne Moult, Jason Jenkins, Julie Jenkins, Michelle McGrath, Lucy Guazzo, Samantha Peden, Danella Favot, Vanessa Ng, Peter Kamen, Muhammad Raza, Helen Rodgers, Megan Hawkins, Andrew Kwintowski, Sian Campbell, Rachelle Seizovic, Grace Young, and Amanda Moore

References

- 1.Bergiers S, Vaes B, Degryse J. To screen or not to screen for peripheral arterial disease in subjects aged 80 and over in primary health care: a cross-sectional analysis from the BELFRAIL study. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song P, Rudan D, Zhu Y, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2015: an updated systematic review and analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e1020–30. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Criqui MH, Matsushita K, Aboyans V, et al. Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: Contemporary Epidemiology, Management Gaps, and Future Directions: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;144:e171–91. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fowkes FGR, Rudan D, Rudan I, et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. The Lancet . 2013;382:1329–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arruda-Olson AM, Moussa Pacha H, Afzal N, et al. Burden of hospitalization in clinically diagnosed peripheral artery disease: A community-based study. Vasc Med . 2018;23:23–31. doi: 10.1177/1358863X17736152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahoney EM, Wang K, Cohen DJ, et al. One-year costs in patients with a history of or at risk for atherothrombosis in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1:38–45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.775247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohn CG, Alberts MJ, Peacock WF, et al. Cost and inpatient burden of peripheral artery disease: Findings from the National Inpatient Sample. Atherosclerosis. 2019;286:142–6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDermott MM, Greenland P, Liu K, et al. Leg symptoms in peripheral arterial disease: associated clinical characteristics and functional impairment. JAMA. 2001;286:1599–606. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.13.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDermott MM, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, et al. Asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease is associated with more adverse lower extremity characteristics than intermittent claudication. Circulation. 2008;117:2484–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.736108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDermott MM, Mehta S, Greenland P. Exertional leg symptoms other than intermittent claudication are common in peripheral arterial disease. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:387–92. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDermott MM. Lower extremity manifestations of peripheral artery disease: the pathophysiologic and functional implications of leg ischemia. Circ Res. 2015;116:1540–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golledge J, Leicht AS, Yip L, et al. Relationship Between Disease Specific Quality of Life Measures, Physical Performance, and Activity in People with Intermittent Claudication Caused by Peripheral Artery Disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2020;59:957–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2020.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regensteiner JG, Hiatt WR, Coll JR, et al. The impact of peripheral arterial disease on health-related quality of life in the Peripheral Arterial Disease Awareness, Risk, and Treatment: New Resources for Survival (PARTNERS) Program. Vasc Med. 2008;13:15–24. doi: 10.1177/1358863X07084911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green S, Askew CD. In: Sports Medicine for Specific Ages and Abilities. 1st ed. Maffulli N, Chan KM, MacDonald R, et al., editors. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2001. The physiology of walking performance in peripheral arterial disease; pp. 385–93. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gornik HL, Aronow HD, Goodney PP, et al. 2024 ACC/AHA/AACVPR/APMA/ABC/SCAI/SVM/SVN/SVS/SIR/VESS Guideline for the Management of Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149:e1313–410. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner AW, Montgomery PS, Killewich LA. Natural history of physical function in older men with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:73–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abaraogu U, Ezenwankwo E, Dall P, et al. Barriers and enablers to walking in individuals with intermittent claudication: A systematic review to conceptualize a relevant and patient-centered program. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0201095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner AW, Montgomery PS, Parker DE. Physical activity is a predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:117–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner AW, Addison O, Katzel LI, et al. Association between Physical Activity and Mortality in Patients with Claudication. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021;53:732–9. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, et al. Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II) J Vasc Surg. 2007;45 Suppl S:S5–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nordanstig J, Behrendt C-A, Baumgartner I, et al. Editor’s Choice -- European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Asymptomatic Lower Limb Peripheral Arterial Disease and Intermittent Claudication. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2024;67:9–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2023.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Treat-Jacobson D, McDermott MM, Bronas UG, et al. Optimal Exercise Programs for Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e10–33. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Askew CD, Parmenter B, Leicht AS, et al. Exercise & Sports Science Australia (ESSA) position statement on exercise prescription for patients with peripheral arterial disease and intermittent claudication. J Sci Med Sport. 2014;17:623–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.10.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tew GA, Harwood AE, Ingle L, et al. The bases expert statement on exercise training for people with intermittent claudication due to peripheral arterial disease. Sport Exerc Sci. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gelin J, Jivegård L, Taft C, et al. Treatment efficacy of intermittent claudication by surgical intervention, supervised physical exercise training compared to no treatment in unselected randomised patients I: one year results of functional and physiological improvements. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2001;22:107–13. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2001.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harwood AE, Smith GE, Cayton T, et al. A Systematic Review of the Uptake and Adherence Rates to Supervised Exercise Programs in Patients with Intermittent Claudication. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;34:280–9. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pymer S, Ibeggazene S, Palmer J, et al. An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of home-based exercise programs for individuals with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2021;74:2076–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2021.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nussbaum EL, Houghton P, Anthony J, et al. Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation for Treatment of Muscle Impairment: Critical Review and Recommendations for Clinical Practice. Physiother Can. 2017;69:1–76. doi: 10.3138/ptc.2015-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomes Neto M, Oliveira FA, Reis HFCD, et al. Effects of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation on Physiologic and Functional Measurements in Patients With Heart Failure: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW WITH META-ANALYSIS. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2016;36:157–66. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Enoka RM, Amiridis IG, Duchateau J. Electrical Stimulation of Muscle: Electrophysiology and Rehabilitation. Physiology (Bethesda) 2020;35:40–56. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00015.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo Y, E Phillips B, Atherton PJ, et al. Molecular and neural adaptations to neuromuscular electrical stimulation; Implications for ageing muscle. Mech Ageing Dev. 2021;193:111402. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2020.111402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams KJ, Babber A, Ravikumar R, et al. Non-Invasive Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;906:387–406. doi: 10.1007/5584_2016_129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Babber A, Ravikumar R, Onida S, et al. Effect of footplate neuromuscular electrical stimulation on functional and quality-of-life parameters in patients with peripheral artery disease: pilot, and subsequent randomized clinical trial. Br J Surg. 2020;107:355–63. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abraham P, Mateus V, Bieuzen F, et al. Calf muscle stimulation with the Veinoplus device results in a significant increase in lower limb inflow without generating limb ischemia or pain in patients with peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:714–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.08.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jéhannin P, Craughwell M, Omarjee L, et al. A systematic review of lower extremity electrical stimulation for treatment of walking impairment in peripheral artery disease. Vasc Med. 2020;25:354–63. doi: 10.1177/1358863X20902272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:200–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDermott MM, Ades PA, Dyer A, et al. Corridor-based functional performance measures correlate better with physical activity during daily life than treadmill measures in persons with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:1231–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.06.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDermott MM, Greenland P, Tian L, et al. Association of 6-Minute Walk Performance and Physical Activity With Incident Ischemic Heart Disease Events and Stroke in Peripheral Artery Disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001846. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.001846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McDermott MM, Tian L, Liu K, et al. Prognostic value of functional performance for mortality in patients with peripheral artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1482–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golledge J, Yip L, Fernando ME, et al. Relationship between requirement to stop during a six-minute walk test and health-related quality of life, physical activity and physical performance amongst people with intermittent claudication. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;76:363–9. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2021.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McDermott MM, Guralnik JM, Criqui MH, et al. Six-minute walk is a better outcome measure than treadmill walking tests in therapeutic trials of patients with peripheral artery disease. Circulation. 2014;130:61–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.007002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Birkett ST, Harwood AE, Caldow E, et al. A systematic review of exercise testing in patients with intermittent claudication: A focus on test standardisation and reporting quality in randomised controlled trials of exercise interventions. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0249277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gardner AW, Skinner JS, Vaughan NR, et al. Comparison of three progressive exercise protocols in peripheral vascular occlusive disease. Angiol Open Access. 1992;43:661–71. doi: 10.1177/000331979204300806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gardner AW, Skinner JS, Cantwell BW, et al. Progressive vs single-stage treadmill tests for evaluation of claudication. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991;23:402–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Borg GAV. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc . 1982;14:377. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198205000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hou X ‐Y., Green S, Askew CD, et al. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial ATP production rate and walking performance in peripheral arterial disease. Clin Physio Funct Imaging. 2002;22:226–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1475-097X.2002.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanderson B, Askew C, Stewart I, et al. Short-term effects of cycle and treadmill training on exercise tolerance in peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:119–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Askew CD, Green S, Hou XY, et al. Physiological and symptomatic responses to cycling and walking in intermittent claudication. Clin Physio Funct Imaging. 2002;22:348–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1475-097X.2002.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barker GA, Green S, Askew CD, et al. Effect of propionyl-L-carnitine on exercise performance in peripheral arterial disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:1415–22. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200109000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chong PFS, Garratt AM, Golledge J, et al. The intermittent claudication questionnaire: a patient-assessed condition-specific health outcome measure. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:764–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Regensteiner J, Steiner J, Panzer R, et al. Evaluation of walking impairment by questionnaire in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Med Biol. 1990;2:142–52. [Google Scholar]

- 53.McDermott MM, Liu K, Guralnik JM, et al. Measurement of walking endurance and walking velocity with questionnaire: validation of the walking impairment questionnaire in men and women with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 1998;28:1072–81. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(98)70034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stanton R, Guertler D, Duncan MJ, et al. Validation of a pouch-mounted activPAL3 accelerometer. Gait & Posture. 2014;40:688–93. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2014.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Edwardson CL, Winkler EAH, Bodicoat DH, et al. Considerations when using the activPAL monitor in field-based research with adult populations. J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6:162–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ryan CG, Grant PM, Tigbe WW, et al. The validity and reliability of a novel activity monitor as a measure of walking. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:779–84. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.027276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grant PM, Ryan CG, Tigbe WW, et al. The validation of a novel activity monitor in the measurement of posture and motion during everyday activities. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:992–7. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.030262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grant PM, Dall PM, Mitchell SL, et al. Activity-monitor accuracy in measuring step number and cadence in community-dwelling older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2008;16:201–14. doi: 10.1123/japa.16.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clarke CL, Holdsworth RJ, Ryan CG, et al. Free-living physical activity as a novel outcome measure in patients with intermittent claudication. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;45:162–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2012.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Montgomery PS, Gardner AW. Comparison of Three Blood Pressure Methods Used for Determining Ankle/Brachial Index in Patients with Intermittent Claudication. Angiol Open Access. 1998;49:723–8. doi: 10.1177/000331979804901003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meneses AL, Nam MCY, Bailey TG, et al. Skeletal muscle microvascular perfusion responses to cuff occlusion and submaximal exercise assessed by contrast-enhanced ultrasound: The effect of age. Physiol Rep. 2020;8:e14580. doi: 10.14814/phy2.14580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Young GM, Krastins D, Chang D, et al. Influence of cuff-occlusion duration on contrast-enhanced ultrasound assessments of calf muscle microvascular blood flow responsiveness in older adults. Exp Physiol. 2020;105:2238–45. doi: 10.1113/EP089065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tonnesen KH. Simultaneous measurement of the calf blood flow by strain-gauge plethysmography and the calf muscle blood flow measured by 133Xenon clearance. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1968;21:65–76. doi: 10.3109/00365516809076978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Isacsson SO. Venous occlusion plethysmography in 55-year old men. A population study in Malmö, Sweden. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1972;537:1–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meneses AL, Nam MCY, Bailey TG, et al. Leg blood flow and skeletal muscle microvascular perfusion responses to submaximal exercise in peripheral arterial disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018;315:H1425–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00232.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boushel R, Langberg H, Olesen J, et al. Monitoring tissue oxygen availability with near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) in health and disease. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2001;11:213–22. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2001.110404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kriel Y, Kwintowski A, Feka K, et al. Near-Infrared Spectroscopy During Reactive Hyperemia for the Assessment of Lower Limb Vascular Function. J Vis Exp . 2024 doi: 10.3791/66511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Young GM, Krastins D, Chang D, et al. The Association Between Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound and Near-Infrared Spectroscopy-Derived Measures of Calf Muscle Microvascular Responsiveness in Older Adults. Heart Lung Circ. 2021;30:1726–33. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2021.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Menêses A, Krastins D, Nam M, et al. Toward a Better Understanding of Muscle Microvascular Perfusion During Exercise in Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease: The Effect of Lower-Limb Revascularization. J Endovasc Ther. 2024;31:115–25. doi: 10.1177/15266028221114722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]