Abstract

Idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD) is a type of Castleman disease unrelated to the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus type 8 (KSHV/HHV8) infection. Presently, iMCD is classified into iMCD-IPL (idiopathic plasmacytic lymphadenopathy), iMCD-TAFRO (thrombocytopenia, anasarca, fever, reticulin fibrosis/renal insufficiency, and organomegaly), and iMCD-NOS (not otherwise specified). The most common treatment for iMCD is using IL-6 inhibitors; however, some patients resist IL-6 inhibitors, especially for iMCD-TAFRO/NOS. Nevertheless, since serum IL-6 levels are not significantly different between the iMCD-IPL and iMCD-TAFRO/NOS cases, cytokines other than IL-6 may be responsible for the differences in pathogenesis. Herein, we performed a transcriptome analysis of cytokine storm-related genes and examined the differences between iMCD-IPL and iMCD-TAFRO/NOS. The results demonstrated that counts per million of STAT2, IL1R1, IL1RAP, IL33, TAFAIP1, and VEGFA (P < 0.001); STAT3, JAK2, MAPK8, IL17RA, IL18, TAFAIP2, TAFAIP3, PDGFA, VEGFC, CXCL10, CCL4, and CXCL13 (P < 0.01); and STAT1, STAT6, JAK1, MAPK1, MAPK3, MAPK6, MAPK7, MAPK9, MAPK10, MAPK11, MAPK12, MAPK14, NFKB1, NFKBIA, NFKBIB, NFKBIZ, MTOR, IL10RB, IL12RB2, IL18BP, TAFAIP6, TNFAIP8L1, TNFAIP8L3, CSF2RBP1, PDGFB, PDGFC, and CXCL9 (P < 0.05) were significantly increased in iMCD-TAFRO/NOS. Particularly, upregulated IL33 expression was demonstrated for the first time in iMCD-TAFRO/NOS. Thus, inflammatory signaling, such as JAK-STAT and MAPK, may be enhanced in iMCD-TAFRO/NOS and may be a cytokine storm.

Keywords: idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease, cytokine storm, transcriptome analysis

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD) is a rare, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus type 8 (KSHV/HHV8)-negative, lymphoproliferative disease of unknown etiology.1,2 It is clinically classified into three subtypes: idiopathic plasmacytic lymphadenopathy (IPL); thrombocytopenia, anasarca, fever, reticulin fibrosis/renal insufficiency, organomegaly (TAFRO); and not otherwise specified (NOS).3–7 Recent studies have established it as an independent clinicopathological entity, although iMCD-IPL was previously included in iMCD-NOS.8 In Japan, most iMCD cases are considered iMCD-IPL and present with better outcomes than the other iMCD subtypes.9,10 Recently, iMCD-TAFRO was shown to induce a disease-causing cytokine storm.11–14 However, there are no reports of gene expression analysis regarding the association between iMCD-TAFRO and cytokine storms.

iMCD-IPL presents with IL-6-related symptoms, such as hypergammaglobulinemia, thrombocytosis, and plasmacytosis.8,11,12 Contrastingly, patients with iMCD-TAFRO and NOS present with severe inflammatory symptoms with often fatal course.5,13 Additionally, the serum levels of various inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, have been previously reported to be elevated.16,17

IL-6 inhibitors are the most common treatment for iMCD.18–20 However, some patients with iMCD are non-responsive to IL-6 inhibitors. Previously, studies have shown patients with IL-6 inhibitor resistance, especially those with iMCD-TAFRO/NOS.13,21 Serum IL-6 levels were not significantly different between the iMCD-IPL and iMCD-TAFRO/NOS, although the treatment effects of IL-6 inhibitors vary.8,18 Therefore, investigating whether cytokines other than IL-6 differ between iMCD subtypes is necessary. Furthermore, identifying the pathogenesis of the iMCD subtypes is crucial for establishing biomarkers and treatment strategies. Herein, we performed a transcriptome analysis of the cytokine storm-related genes to examine how they differed between iMCD-IPL and iMCD-TAFRO/NOS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

This study included 19 Japanese patients with lymph node lesions in the iMCD-IPL (n = 12), iMCD-TAFRO (n = 2), and iMCD-NOS (n = 5). All cases were retrieved from the surgical pathology consultation files of Okayama University, Japan. All cases had formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks and the frozen specimens were available. All iMCD cases met the iMCD diagnostic criteria.1 According to previous reports,6,7 we defined iMCD-IPL as a case meeting all four criteria: (1) prominent polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia (gamma globulin > 4.0 g/dL or serum immunoglobulin G level >3500 mg/dL), (2) multiple lymphadenopathy, (3) absence of a definite autoimmune disease, and (4) sheet-like infiltration of mature plasma cells. Additionally, iMCD-TAFRO was defined according to the criteria provided in a previous report.4 iMCD-TAFRO was defined as meeting at least four clinical criteria (thrombocytopenia, anasarca, fever/hyperinflammatory state, organomegaly), renal dysfunction or reticulin fibrosis, and lymph node pathology. iMCD-NOS included cases that met the iMCD criteria1 but not the iMCD-IPL6,7 and iMCD-TAFRO4 criteria. All cases were serologically or immunohistochemically negative for KSHV/HHV8. All FFPE blocks were sliced into 3 µm thin sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining to evaluate the histological findings.

The Institutional Review Board of Okayama University approved this study (protocol number 2007-033), which was performed in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

RNA extraction and transcriptome analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the frozen specimens using a RNeasy Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was quantified using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States). Following processing using the poly A method, the remaining RNAs were fragmented using a fragmentation buffer and reverse-transcribed into cDNA with random primers. RNA sequencing was performed using the NovaSeq 6000 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States).

Statistical Analysis

The chi-square test was used for categorical data. All P-values were calculated from two-sided tests, and statistical significance was set using a threshold of 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.3.2; https://cran.r-project.org).

The transcriptome data were corrected for counts per million (CPM). CPM < 0.5 in all cases was excluded from the analysis. Additionally, the CPM was log-transformed.

RESULTS

Clinical findings

Table 1 reveals the clinical findings of the iMCD-IPL and iMCD-TAFRO/NOS cases.

Table 1. Comparison of the clinical findings between iMCD-IPL and iMCD-TAFRO/NOS.

| iMCD-IPL (n = 12) | iMCD-TAFRO/NOS (n = 7) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| age (mean±SD) | 56.7 ± 11.1 | 55.6 ± 9.1 | 0.703 |

| sex (M/F) | 6/6 | 4/3 | |

| anasarca, n (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (85.7) | <0.001 |

| WBC (/µL) | 7401.1 ± 2459.9† | 7923.1 ± 3353.8 | 0.837 |

| Plt (×104/µL) | 35.0 ± 15.3† | 20.9 ± 13.4 | 0.0853 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 9.2 ± 2.6† | 10.3 ± 1.8 | 0.421 |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 5222.0 ± 1359.1 | 2304.7 ± 1161.4 | <0.001 |

| IgM (mg/dL) | 196.6 ± 87.8† | 106.8 ± 16.0‡ | <0.05 |

| IgA (mg/dL) | 523.0 ± 224.8† | 300.0 ± 118.3‡ | 0.0553 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 7.3 ± 3.8† | 10.5 ± 9.0 | 0.860 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8 ± 0.2† | 7.6 ± 14.1‡ | <0.05 |

Significance was calculated using the Mann–Whitney U test. Fisher’s exact analysis or the chi-square test was used for the statistical analysis of nominal scales. Significant P-values are indicated in bold. SD, standard deviation; WBC, white blood cell; Plt, platelet; Hb, hemoglobin; Ig, immunoglobulin; CRP, C-reactive protein.

†WBC, Plt, Hb, IgM, IgA, CRP and Creatinine levels were available for 9, 11, 11, 10, 10, 11 and 7 patients with iMCD-IPL, respectively. ‡IgM, IgA and Creatinine levels were available for 5, 5 and 6 patients with iMCD-TAFRO/NOS, respectively.

Six of the seven iMCD-TAFRO/NOS cases presented with anasarca, but none presented with iMCD-IPL (P < 0.001). White blood cell counts and hemoglobin levels were not significantly different between the two diseases (P = 0.837 and P = 0.421, respectively). Platelet count tended to be higher in the iMCD-IPL group (P = 0.0853). Serum IgG and IgM levels were significantly higher in the iMCD-IPL group than in the iMCD-TAFRO/NOS group (P < 0.001, P < 0.05, respectively). No significant differences in serum IgA levels between the two groups (P = 0.0553). Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were higher in the iMCD-TAFRO/NOS group; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.860). Furthermore, creatinine levels were significantly higher in the iMCD-TAFRO/NOS group than in the iMCD-IPL group (P < 0.05).

Table 2 shows a comparison of the clinical findings of iMCD-TAFRO and iMCD-NOS according to the consensus criteria for iMCD-TAFRO.4

Table 2. Comparison of the clinical findings between iMCD-TAFRO and iMCD-NOS.

| No. | iMCD subtype | Age | Sex | (T) Thrombocytopenia (<10×104/µL) |

Platelet (×104/µL) |

(A) Anasarca (Pleural effusion, ascites, or subcutaneous edema) |

(F) Fever or hyperinflammatory status (Fever ≥37.5 °C or CRP ≥2.0 mg/dL) |

CRP (mg/dL) |

(R) Renal insufficiency (eGFR ≤ 60, Cre >1 mg/dL (F), >1.3 mg/dL (M), or renal failure necessitating hemodialysis) |

eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) |

Creatinine (mg/dl) |

Reticulin fibrosis | (O) Organomegaly (lymphadenopathy in two or more regions, hepatomegaly, or splenomegaly) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TAFRO | 48 | M | + | 2.1 | + | + | 8.49 | + | N/A | 1.73 | N/A | + |

| 2 | TAFRO | 64 | M | + | 3.8 | + | + | 17.23 | + | 62.9 | 0.94 | N/A | + |

| 3 | NOS | 51 | F | - | 24.1 | + | + | 29.4 | + | 54.7 | 0.86 | + | + |

| 4 | NOS | 49 | F | - | 35.8 | + | + | 4.1 | - | 104.7 | 0.48 | - | + |

| 5 | NOS | 74 | M | - | 22 | + | - | 0.9 | - | N/A | 1.17 | N/A | + |

| 6 | NOS | 49 | M | - | 12.2 | + | + | 6 | + | 35.1 | 1.72 | N/A | + |

| 7 | NOS | 54 | F | - | 40.4 | - | + | 7.26 | + | 46.6 | 0.98 | N/A | + |

The reference considered was the laboratory data before the lymph node biopsy. The thresholds for each data point are determined based on the iMCD-TAFRO consensus criteria.4 iMCD-TAFRO was defined as meeting at least four clinical criteria (thrombocytopenia, anasarca, fever/hyperinflammatory status, and organomegaly), renal dysfunction or reticulin fibrosis, and pathological criteria for lymph nodes. Patient 4 presented with renal failure and did not require hemodialysis.

All cases of iMCD-TAFRO and four cases of iMCD-NOS presented with anasarca. Organomegaly was observed in all iMCD-TAFRO/NOS cases. Elevated CRP was observed in all cases, excluding one case of iMCD-NOS (case No. 5). Renal insufficiency was present in all but two cases of iMCD-NOS cases. No iMCD-NOS cases met the thrombocytopenia criteria.

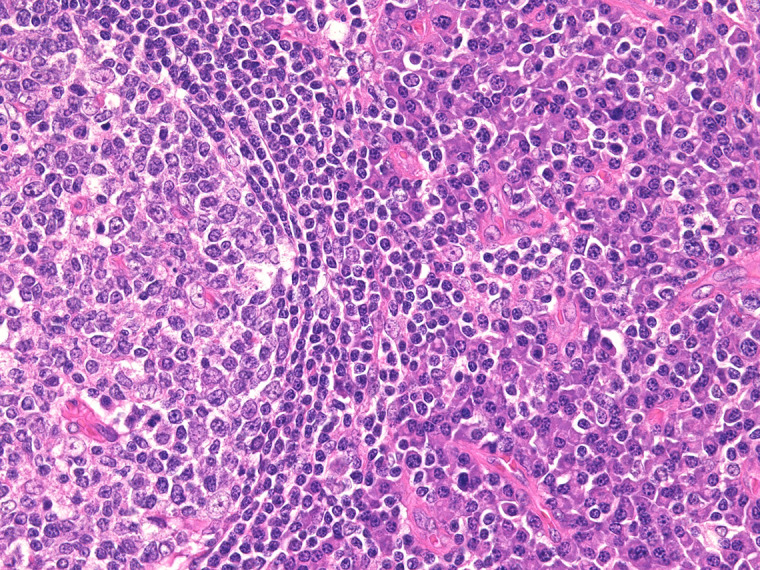

Histological findings

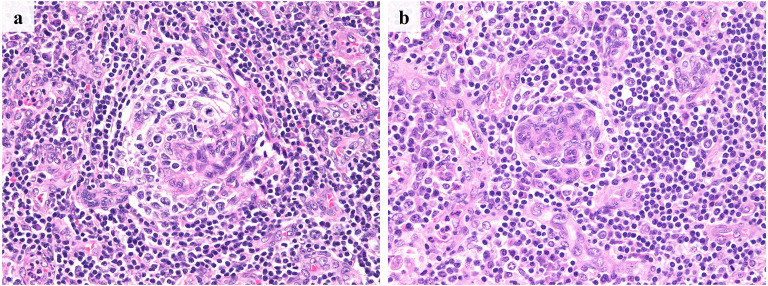

Figures 1 and 2 present the histological findings of iMCD.

Fig. 1.

Histological findings of iMCD-IPL

Hyperplastic germinal centers and sheet-like proliferation of mature plasma cells are seen. No prominent vascularization is noted.

Fig. 2.

Histological findings of iMCD-TAFRO and iMCD-NOS

a: iMCD-TAFRO (case no. 2). b: iMCD-NOS (case no. 3). In both cases, whirl-like vascular proliferation was observed in the atrophic germinal centers. Additionally, marked vascularization was observed in the interfollicular area.

Hyperplastic germinal centers and sheet-like proliferation of mature plasma cells were observed in iMCD-IPL. No or slight vascular proliferation in the germinal centers and interfollicular areas was observed (Figure 1).

Contrastingly, atrophic germinal centers were observed in the iMCD-TAFRO (Figure 2a) and iMCD-NOS (Figure 2b) groups. Additionally, marked vascular proliferation was observed in the germinal centers and interfollicular areas. In the iMCD-TAFRO/NOS group, whirl-like vascularization was also observed in the germinal centers (Figure 2). Sheet-like proliferation of mature plasma cells was not observed in either group in contrast to iMCD-IPL. Histological findings of iMCD-TAFRO and iMCD-NOS were similar.

Transcriptome analysis

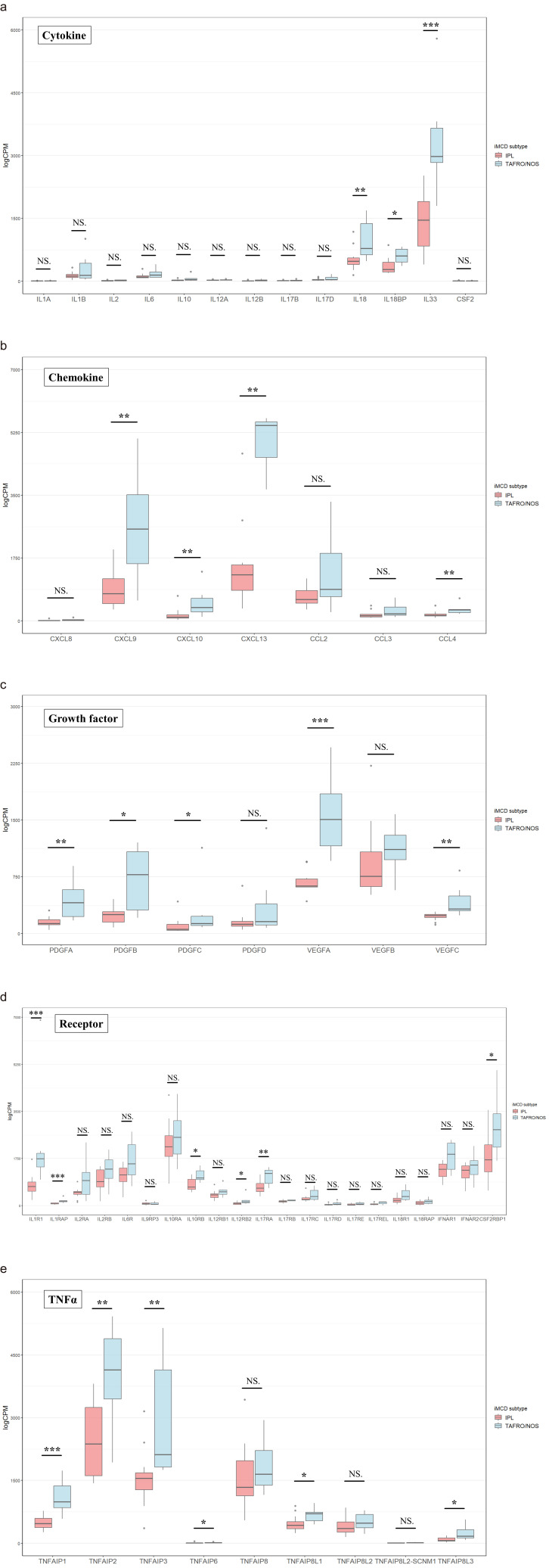

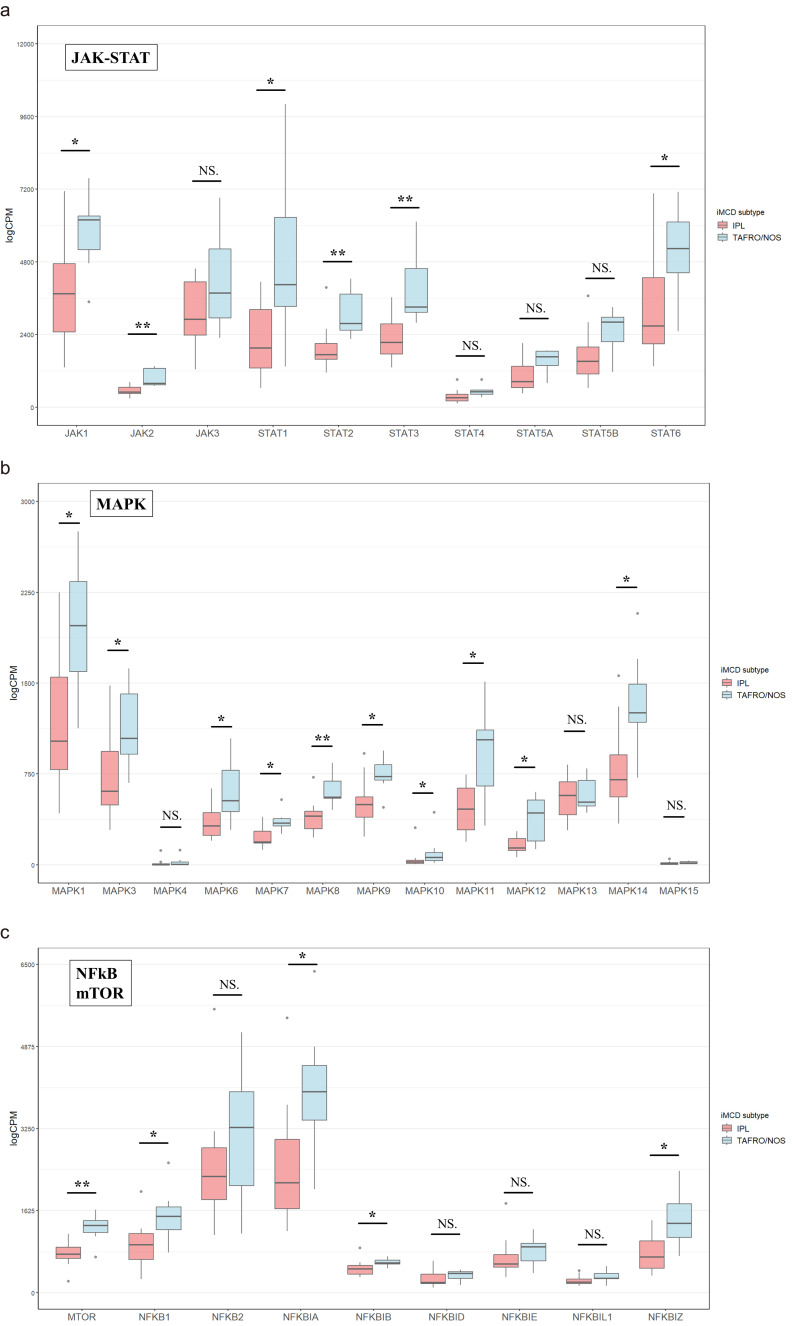

Figures 3 and 4 show a comparison of the CPM of the cytokine storm-related genes between iMCD-TAFRO/NOS and iMCD-IPL. Genes were selected and compared for cytokines and chemokines, which are generally reported to be mediators of the cytokine storm.11 Additionally, we compared the Janus kinase (JAK)-STAT, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and NFκB-related genes that have been reported to be activated by IL-6 signaling.22,23

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the counts per million for the cytokine storm-related genes between iMCD-IPL and iMCD-TAFRO/NOS

a: Cytokines. b: Chemokines. c: Growth factors. d: Receptors for interleukins. e: Tumor necrosis factor-related genes. NS, Not significant. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the counts per million of JAK-STAT, MAPK, and mTOR and NFκB-related genes between iMCD-IPL and iMCD-TAFRO/NOS

a: JAK-STAT-related genes. b: MAPK-related genes. c: mTOR- and NFκB-related genes.

NS, Not significant. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

A comparison of cytokine gene expression revealed that IL18, IL18BP, and IL33 were significantly upregulated in iMCD-TAFRO/NOS (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, and P < 0.001, respectively). Among these, IL33 expression was the highest. The CPM of the other interleukins was low, and no difference was observed between the two groups (Figure 3a). The CPM of IL9 was extremely low; therefore, it was excluded from the study. Among the chemokines, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL13, and CCL4 were significantly upregulated in iMCD-TAFRO/NOS (P < 0.01, P < 0.01, P < 0.01, and P < 0.01, respectively). The CPM of CXCL8 and CCL3 CPM was low and not significantly different (Figure 3b). The CPM of growth factors, such as PDGF and VEGF was significantly upregulated among PDGFA, PAGFB, PDGFC, VEGFA, and VEGFC in iMCD-TAFRO/NOS (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.001, and P < 0.01, respectively). The CPM of VEGFA was the most upregulated, and the differences between the subtypes were statistically significant (Figure 3c). The CPM of several cytokine receptors was lower (Figure 3d); however, a significant upregulation of IL1R1, IL1RAP, IL10RB, IL12RB2, IL17RA, and CSF2RBP1 was noted (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.05, respectively). Additionally, significant upregulation was observed in several TNAα related genes such as TNFAIP1, TNFAIP2, TNFAIP3, TNFAIP6, TNFAIP8L1, and TNFAIP8L3 (P < 0.001, P < 0.01, P < 0.01, P < 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.05, respectively) (Figure 3e).

Among the JAK-STAT signaling-related genes (Figure 4a), JAK1/2 and STAT1/2/3/6 were upregulated (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.01, P < 0.05, respectively). Additionally, some MAPK-related genes, such as MAPK1/3/6/7/8/9/10/11/12/14 were upregulated in iMCD-TAFRO/NOS (P < 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.05, respectively) (Figure 4b). Furthermore, MTOR and NFκB signal-related genes like NFKB1, NFKBIA/B, and NFKBIZ were upregulated (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.05, respectively) (Figure 4c).

DISCUSSION

Transcriptome analysis revealed that the expression of cytokine storm-related genes differed between the iMCD-IPL and iMCD-TAFRO/NOS groups. Thus, these two diseases may have different pathogenesis in their gene expression patterns. Although no significant differences were observed in the IL6 expression between iMCD-IPL and iMCD-TAFRO/NOS, STAT, MAPK, mTOR, and NFκB-related gene expression was upregulated in the iMCD-TAFRO/NOS group.

Herein, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) was the most significantly upregulated gene among those associated with JAK-STAT in the iMCD-TAFRO/NOS group. STAT3 is a member of the STAT family, which plays a role in immunomodulation via the JAK-STAT pathway. Various cytokines affect the JAK-STAT pathway, especially STAT3, associated with IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, IL-9, IL-21, IFNα/β, and growth factors (GF).24,25 Several members of the MAPK family were upregulated in the iMCD-TAFRO/NOS group, with the highest expression of MAPK1. MAPK signaling regulates various cellular processes, including cell proliferation, growth, differentiation, transformation, and apoptosis.26 MAPK1 (ERK2) is known to be activated by GFs such as PDGF and VEGF, TNFα, and IL-1.27 Moreover, MTOR expression was upregulated in the iMCD-TAFRO/NOS group. Previous studies have demonstrated that mTOR activation is increased in the serum proteomes of patients with iMCD.28,29 The finding of enhanced MTOR in the transcriptome analysis of lymph nodes was consistent with the results of previous reports.

This study observed a significant upregulation of interleukin receptors (TNFAIP1/2/3/6, TNEAIP8L1/3) and GFs (VEGF and PDGF) in the iMCD-TAFRO/NOS group. Additionally, IL6 tended to be upregulated, although the difference was not significant. These cytokines may be linked to the upregulation of JAK-STAT, MAPK, mTOR, and NFκB-related genes.

Activation of STAT signaling may be associated with a cytokine storm.30–32 Various cytokines have been suggested to enhance STAT and MAPK signaling in iMCD-TAFRO/NOS, and the pathological condition may be a cytokine storm (Figure 5). The definition of a cytokine storm is unclear, and there is disagreement as to how these diseases differ from normal inflammatory responses.11 Cytokine storms commonly demonstrate elevated inflammatory cytokine levels; however, no laboratory parameters are included in their grading.33 The inflammatory symptoms of iMCD-TAFRO/NOS are present independent of the treatment and are considered temporary cytokine storms.

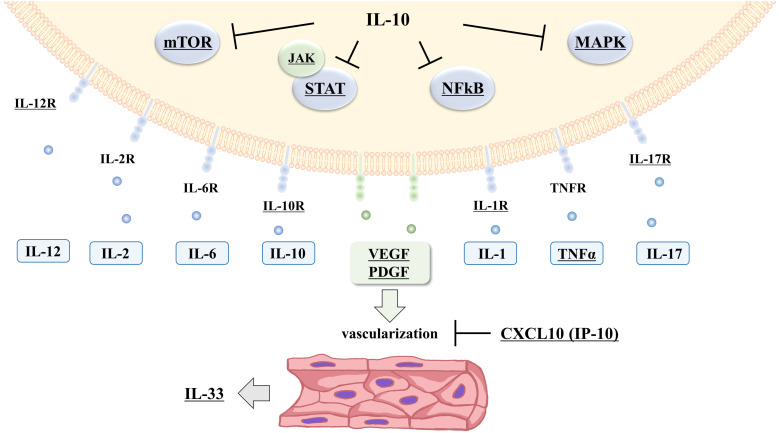

Fig. 5.

Pathological prediction of iMCD-TAFRO/NOS based on transcriptome analysis

Based on transcriptome analysis, mediators of the cytokine storms with gene upregulation in TAFRO/NOS are illustrated. Statistically significant factors are underlined. Several inflammatory cytokines have been suggested to be upregulated and activate various inflammatory signals in iMCD-TAFRO/NOS. Additionally, growth factors such as VFGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) and PDGF (platelet-derived growth factor) may mediate vascularization in the lymph node lesions. CXCL10 and IL-10 upregulation is thought to inhibit inflammatory signaling and vascularization.

Particularly, STAT3 and NF-κB activation promotes angiogenesis by VEGF.23,34 VEGFA upregulation causes vascularization and improves vascular permeability.35,36 VEGFA may result in anasarca and vascularization of lymph node lesions in iMCD-TAFRO/NOS.

Moreover, IL33 was upregulated in the iMCD-TAFRO/NOS group. Furthermore, IL-33 has been previously found to be produced in vascular endothelial and fibroblastic reticular cells.37 IL33 upregulation in iMCD-TAFRO/NOS may be associated with the hypervascularization of lymph node lesions. Previously, IL-33 has been shown to activate MAPK and STAT3 signaling and function as a pro-inflammatory factor.15 Since IL33 is upregulated, serum IL-33 levels are possibly elevated in iMCD-TAFRO/NOS. However, there are no reports examining the IL-33 levels in iMCD-TAFRO/NOS; further studies are necessary.

Additionally, significant upregulation of CXCL10 and a tendency to upregulation of IL10 were observed in the iMCD-TAFRO/NOS group. CXCL10 upregulation is consistent with a previous report on serum cytokine analysis in iMCD.17 CXCL10, also called IP-10, is an inflammatory chemokine and an inflammation and angiogenesis regulator, and almost all immune cells, including lymphocytes, monocytes, and neutrophils, produce this chemokine.38,39 Although the patients with iMCD-TAFRO/NOS presented clinically acute inflammatory symptoms, the expression of these genes was upregulated. Thus, CXCL10 and IL10 upregulation may be a regulatory mechanism for activating the JAK-STAT, MAPK, mTOR and NF-κB pathway, and VEGFA.

This study had several limitations. First, identifying cells that expressed each gene was challenging because the transcriptome analysis performed in this study was bulky. Second, the number of TAFRO/NOS cases was small; therefore, detecting statistically significant differences was not possible.

Furthermore, none of the cytokine storm-related genes examined in this study were upregulated in the iMCD-IPL group. These results suggest that the pathogenesis of iMCD-IPL is not a cytokine storm. Clinically, iMCD-IPL is known to present an indolent clinical course compared to iMCD-TAFRO/NOS.8 Therefore, other genes may be related to the inflammatory pathogenesis of iMCD-IPL and require further analysis.

Herein, the clinical findings of the iMCD-NOS cases were similar to those of the iMCD-TAFRO cases. However, iMCD-TAFRO had consensus criteria, whereas the iMCD-NOS cases did not meet all of these criteria. Four of the five patients with iMCD-NOS presented with anasarca, and none met the criteria for thrombocytopenia. Contrastingly, the gene expression patterns suggested that iMCD-TAFRO and iMCD-NOS overlap.40 Additionally, they shared similar histological findings. Based on these results, the present study analyzed iMCD-NOS, which is similar to iMCD-TAFRO in the same group. However, future studies should examine the distinction between the two. Furthermore, specific biomarkers should be established to clarify the differences in the pathogenesis of iMCD subtypes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP 23K1447605 and 24KK0172, MHLW Program Grant Number JPMH 23FC1025, AMED under Grant Number JP 22ek0109589h0001, and Ryobi Teien Memory Foundation (2023) in Japan (F.O.).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fajgenbaum DC, Uldrick TS, Bagg A, et al. International, evidence-based consensus diagnostic criteria for HHV-8-negative/idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2017; 129: 1646-1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishimura MF, Nishimura Y, Nishikori A, Yoshino T, Sato Y. Historical and pathological overview of Castleman disease. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2022; 62: 60-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwaki N, Fajgenbaum DC, Nabel CS, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of TAFRO syndrome demonstrates a distinct subtype of HHV-8-negative multicentric Castleman disease. Am J Hematol. 2016; 91: 220-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishimura Y, Fajgenbaum DC, Pierson SK, et al. Validated international definition of the thrombocytopenia, anasarca, fever, reticulin fibrosis, renal insufficiency, and organomegaly clinical subtype (TAFRO) of idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Am J Hematol. 2021; 96: 1241-1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishimura Y, Nishimura MF, Sato Y. International definition of iMCD-TAFRO: future perspectives. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2022; 62: 73-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mori S, Mohri N. [Clinicopathological analysis of systemic nodal plasmacytosis with severe polyclonal hyperimmunoglobulinemia]. Proceedings of the Japanese Society of Pathology. 1978; 67: 252-253. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeuchi K. Idiopathic plasmacytic lymphadenopathy: A conceptual history along with a translation of the original Japanese article published in 1980. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2022; 62: 79-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishikori A, Nishimura MF, Nishimura Y, et al. Idiopathic Plasmacytic Lymphadenopathy Forms an Independent Subtype of Idiopathic Multicentric Castleman Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23: 10301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L, Dong YJ, Peng HL, et al. A national, multicenter, retrospective study of Castleman disease in China implementing CDCN criteria. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023; 34: 100720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishikori A, Nishimura MF, Fajgenbaum DC, et al. Diagnostic challenges of the idiopathic plasmacytic lymphadenopathy (IPL) subtype of idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD): Factors to differentiate from IgG4-related disease. J Clin Pathol. 2024. Feb 20: jcp-2023-209280. doi: . Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Fajgenbaum DC, June CH. Cytokine Storm. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383: 2255-2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishikori A, Nishimura MF, Nishimura Y, et al. Investigation of IgG4-positive cells in idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease and validation of the 2020 exclusion criteria for IgG4-related disease. Pathol Int. 2022; 72: 43-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fajgenbaum DC. Novel insights and therapeutic approaches in idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2018; 132: 2323-2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abe N, Kono M, Kono M, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β/CCR6-positive bone marrow cells correlate with disease activity in multicentric Castleman disease-TAFRO. Br J Haematol. 2022; 196: 1194-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arrizabalaga L, Risson A, Ezcurra-Hualde M, Aranda F, Berraondo P. Unveiling the multifaceted antitumor effects of interleukin 33. Front Immunol. 2024; 15: 1425282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sumiyoshi R, Koga T, Kawakami A. Biomarkers and Signaling Pathways Implicated in the Pathogenesis of Idiopathic Multicentric Castleman Disease/Thrombocytopenia, Anasarca, Fever, Reticulin Fibrosis, Renal Insufficiency, and Organomegaly (TAFRO) Syndrome. Biomedicines. 2024; 12: 1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwaki N, Gion Y, Kondo E, et al. Elevated serum interferon γ-induced protein 10 kDa is associated with TAFRO syndrome. Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 42316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Rhee F, Wong RS, Munshi N, et al. Siltuximab for multicentric Castleman’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014; 15: 966-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanda J, Kawabata H, Yamaji Y, et al. Reversible cardiomyopathy associated with Multicentric Castleman disease: successful treatment with tocilizumab, an anti-interleukin 6 receptor antibody. Int J Hematol. 2007; 85: 207-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pierson SK, Shenoy S, Oromendia AB, et al. Discovery and validation of a novel subgroup and therapeutic target in idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood Adv. 2021; 5: 3445-3456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fajgenbaum DC, Langan RA, Japp AS, et al. Identifying and targeting pathogenic PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in IL-6-blockade-refractory idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. J Clin Invest. 2019; 129: 4451-4463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brasier AR. The nuclear factor-kappaB-interleukin-6 signalling pathway mediating vascular inflammation. Cardiovasc Res. 2010; 86: 211-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang B, Lang X, Li X. The role of IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in cancers. Front Oncol. 2022; 12: 1023177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xue C, Yao Q, Gu X, et al. Evolving cognition of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway: autoimmune disorders and cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023; 8: 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vignais ML, Gilman M. Distinct mechanisms of activation of Stat1 and Stat3 by platelet-derived growth factor receptor in a cell-free system. Mol Cell Biol. 1999; 19: 3727-3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrison DK. MAP kinase pathways. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012; 4: a011254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cargnello M, Roux PP. Activation and function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated protein kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2011; 75: 50-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips AD, Kakkis JJ, Tsao PY, Pierson SK, Fajgenbaum DC. Increased mTORC2 pathway activation in lymph nodes of iMCD-TAFRO. J Cell Mol Med. 2022; 26: 3147-3152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arenas DJ, Floess K, Kobrin D, et al. Increased mTOR activation in idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2020; 135: 1673-1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dhall A, Patiyal S, Sharma N, Devi NL, Raghava GPS. Computer-aided prediction of inhibitors against STAT3 for managing COVID-19 associated cytokine storm. Comput Biol Med. 2021; 137: 104780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gajjela BK, Zhou MM. Calming the cytokine storm of COVID-19 through inhibition of JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Drug Discov Today. 2022; 27: 390-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salem F, Li XZ, Hindi J, et al. Activation of STAT3 signaling pathway in the kidney of COVID-19 patients. J Nephrol. 2022; 35: 735-743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee DW, Santomasso BD, Locke FL, et al. ASTCT Consensus Grading for Cytokine Release Syndrome and Neurologic Toxicity Associated with Immune Effector Cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019; 25: 625-638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo C, Ruan Y, Sun P, et al. The Role of Transcription Factors in Coronary Artery Disease and Myocardial Infarction. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2022; 27: 329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou H, Geng F, Chen Y, et al. The mineral dust-induced gene, mdig, regulates angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in lung adenocarcinoma by modulating the expression of VEGF-A/C/D via EGFR and HIF-1α signaling. Oncol Rep. 2021; 45: 60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferrara N. From the discovery of vascular endothelial growth factor to the introduction of avastin in clinical trials - an interview with Napoleone Ferrara by Domenico Ribatti. Int J Dev Biol. 2011; 55: 383-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cayrol C, Girard JP. IL-33: an alarmin cytokine with crucial roles in innate immunity, inflammation and allergy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014; 31: 31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antonelli A, Ferrari SM, Giuggioli D, et al. Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL)10 in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2014; 13: 272-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu M, Guo S, Hibbert JM, et al. CXCL10/IP-10 in infectious diseases pathogenesis and potential therapeutic implications. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011; 22: 121-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishimura Y, Nishikori A, Sawada H, et al. Idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease with positive antiphospholipid antibody: atypical and undiagnosed autoimmune disease? J Clin Exp Hematop. 2022; 62: 99-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]