When darkness falls and blinking neon brightens the often drab cities and towns of Japan, white-collar workers crowd into tiny bars — there are 15 000 in Tokyo alone — and unwind by sipping Suntory Gold whisky and water at $15 a shot. Tradesmen and labourers head for “standbars” and gulp down plastic cups of shochu, cheaper distilled spirits dispensed from vending machines. And although there is little absenteeism in Japan due to drinking, the country's doctors are worried — problem drinkers numbered 3 million at the last tally.

Japan's thirst has continued unabated long after the economic twilight fell on the Land of the Rising Sun. “There is no question that alcoholism is increasing in Japan,” says Dr. Hiorakai Kono, former director of the National Institute of Alcoholism in Tokyo. “What astonishes us is the size of the problem.”

Problem drinking cuts across all levels of society, according to the latest study by the Leisure Development Research Centre in Tokyo. Sixty percent of problem drinkers are salaried businessmen who claim that getting drunk with clients or coworkers is part of their job and a mark of company loyalty. To refuse a drink from the boss is a terrible insult that can damage a career. And although alcohol consumption is now decreasing in most industrialized countries, it has quadrupled in Japan since 1960.

Drinking is not a moral issue here, since there is no religious prohibition against alcohol consumption, and the temperance movement has never had an impact. And unlike many Westerners, the Japanese don't regard alcohol as a drug.

Traditionally, there has been an indulgent attitude toward those who drink too much — and for good reason. In a tightly knit society where concealing emotions and frustrations is a highly developed and necessary part of maintaining “consensus,” getting drunk is a socially sanctioned safety valve. “Alcohol here plays the role of psychiatry in the West,” says Charles Pomeroy, former president of the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan and a Tokyo resident for 45 years. “I think the country would explode without it.”

Japan lags far behind Western countries in recognizing and treating alcoholism. Fewer than 1200 hospital beds are available for alcoholic patients, and the country's 2 national mental hospitals provide only 200 beds. Private treatment centres are becoming more common, but no medical credentials or accreditation are required to operate them.

There are 5 halfway houses, all run by religious groups, but for the most part follow-up and rehabilitation services do not exist. Instead, families, aided by groups such as Japan's version of Alcoholics Anonymous, take on the burden of rehabilitation. — Dave Milne, Tokyo

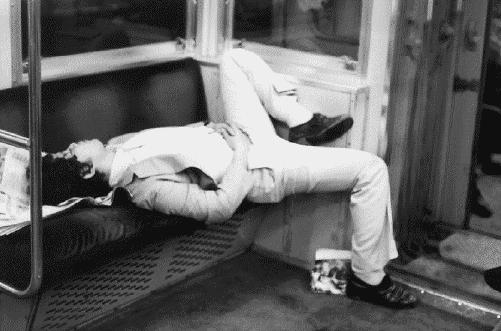

Figure. One for the road Photo by: Dave Milne