Abstract

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic, multidomain, inflammatory disease requiring long-term treatment. Guselkumab, a fully human interleukin [IL]-23p19-subunit inhibitor, and the IL-17A inhibitors (IL-17Ai) ixekizumab and secukinumab are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for adults with active PsA. Real-world data evaluating on-label treatment persistence is an important consideration for patients.

Methods

This retrospective claim-based analysis (IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus) included adults with PsA receiving guselkumab or their first subcutaneous (SC) IL-17Ai (ixekizumab/secukinumab) per FDA label (“on-label”) between July 14, 2020, and June 30, 2022. Baseline demographic and disease characteristics were collected in the 12 months preceding the index date (date of first guselkumab or SC IL-17Ai claim); follow-up extended through the earlier of the end of continuous insurance eligibility or end of data availability. Baseline characteristics were balanced between the cohorts by propensity score weighting (standardized mortality ratio [SMR]). Discontinuation was defined as a gap 2 × the FDA-approved maintenance dosing interval (guselkumab:112 days; SC IL-17Ai: 56 days); on-label persistence in the weighted cohorts was assessed using Kaplan-Meier curves and compared with a Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

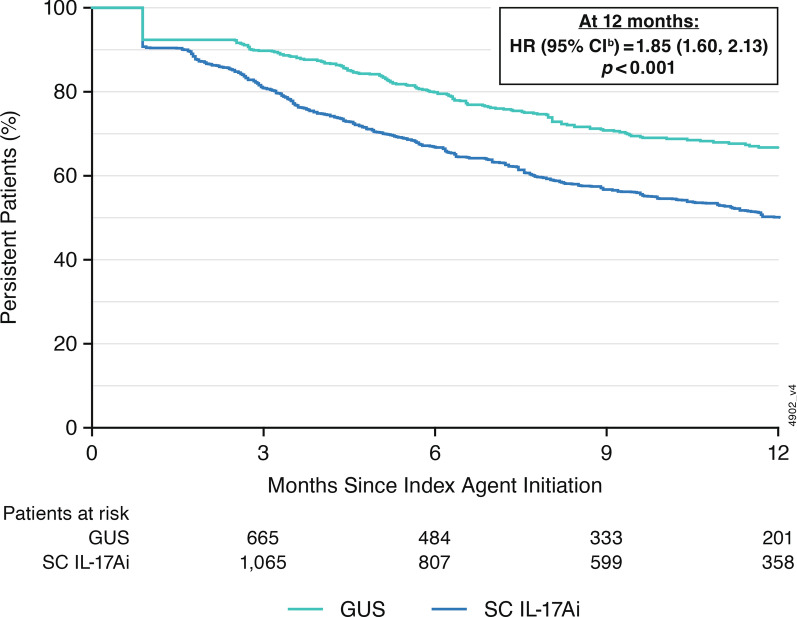

Weighted demographic and disease characteristics were well balanced between the cohorts (guselkumab: N = 910, mean age = 50.4 years, 60.4% female; SC IL-17Ai: N = 2740, mean age = 50.2, 59.4% female). At 12 months, the guselkumab cohort was 1.85 × more likely to remain persistent with on-label therapy vs the SC IL-17Ai cohort (p < 0.001); median time to discontinuation was not reached for guselkumab and was 12.3 months for SC IL-17Ai. At 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, persistence rates in the weighted cohorts were higher with guselkumab than with SC IL-17Ai (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

In this real-world claims data analysis in adults with PsA, on-label persistence rates were statistically significantly higher with guselkumab, as early as 3 months, with ~ 2 × greater likelihood of persistence at 12 months relative to SC IL-17Ai.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-024-03042-1.

Keywords: Guselkumab, Psoriatic arthritis, Persistence, Real-world evidence, Subcutaneous interleukin-17A inhibitors

Plain Language Summary

Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic, progressive, inflammatory disease that requires long-term treatment. Overproduction of proteins called cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-23 and IL-17A, are known to be involved in psoriatic arthritis. Current treatment guidelines for patients with psoriatic arthritis recommend using medications made from antibodies (biologics), including those that inhibit IL-23 and IL-17A, for some patients. Guselkumab is an antibody medication that blocks IL-23; ixekizumab and secukinumab are antibody medications that block IL-17A. All three treatments are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis and are given subcutaneously at specific dosing regimens (referred to as “on-label”). This study used information collected from health insurance prescription claims to measure how many patients who started taking guselkumab, ixekizumab, or secukinumab using an on-label dosage were still taking this medication after 12 months. Anonymous patient information was selected from the database for adults who had at least two claims for psoriatic arthritis and started taking either guselkumab or one of the two IL-17A blockers (ixekizumab, secukinumab) between July 14, 2020 and June 30, 2022. Medication claims were included from 910 patients taking guselkumab and 2740 patients taking an IL-17 blocker. The characteristics of these groups (e.g., age, comorbidities, prior psoriatic arthritis treatments) were balanced between the two groups using a statistical method called propensity score weighting. At 1 year, patients in the guselkumab group were almost twice as likely to still be using their medication as the patients using ixekizumab or secukinumab.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-024-03042-1.

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic, multidomain, inflammatory disease that often requires long-term treatment with biologics; therefore, real-world evidence may provide a better understanding of persistence with particular therapies and is of interest to patients and their health care providers |

| Guselkumab, a fully human interleukin (IL)-23p19-subunit inhibitor, was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) for the treatment of active PsA, and real-world data of on-label persistence with guselkumab in comparison with biologics utilizing other mechanisms of action are limited |

| What did the study ask? |

| This retrospective claims-based analysis utilized real-world data to compare treatment persistence through 12 months for patients receiving guselkumab or their first subcutaneous (SC) IL-17A inhibitor (i) (ixekizumab, secukinumab) at dosing regimens consistent with FDA-approved labeling (on-label); treatment discontinuation was defined as a gap 2 × the FDA-approved maintenance interval (guselkumab: 112 days; SC IL-17Ai: 56 days) |

| What has been learned from the study? |

| After propensity score weighting to balance the guselkumab (N = 910) and SC IL-17Ai (N = 2740) cohorts, patients in the guselkumab cohort had statistically significantly higher rates of on-label persistence at 3, 6, and 9 months and were approximately 2× more likely to remain persistent with on-label treatment at 12 months compared with patients in the SC IL-17Ai cohort |

| These findings may provide valuable information for patients and health care providers when considering treatment options |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a graphical abstract, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article, go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.27248352.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory disease primarily affecting the peripheral joints and skin [1]. The manifestations of PsA often present in a heterogeneous manner with signs and symptoms across the six disease domains recognized by the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA): peripheral arthritis, axial disease, enthesitis, dactylitis, and skin and nail psoriasis [2]. Updated GRAPPA treatment guidelines for PsA are focused on selecting therapies to address active disease domains while also accounting for safety considerations of related conditions (inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] and uveitis) in individual patients [2]. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, and conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), including methotrexate, are generally utilized early in the disease process or for patients with less severe disease, while biologic (b) DMARDs are typically recommended for patients who do not experience adequate disease control with conventional nonbiologic medications or for those with certain prognostic factors, such as an elevated risk for radiographic progression [2, 3]. Currently, several bDMARDs, including those inhibiting tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL)-23, and IL-17A, have demonstrated efficacy in improving PsA signs and symptoms across domains and are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for patients with active PsA [2].

Guselkumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that selectively inhibits the IL-23p19 subunit [4]. In the phase 3, randomized, double-blind clinical trials, DISCOVER-1 (biologic-naïve and -experienced) and DISCOVER-2 (biologic-naïve), guselkumab 100 mg administered as subcutaneous (SC) injections every 4 weeks (Q4W) or at weeks 0, 4, and every 8 weeks (Q8W) demonstrated efficacy vs placebo in improving the signs and symptoms of active PsA [5, 6]. The Q8W dosing regimen was subsequently approved by the US FDA in July 2020 for adults with active PsA [4]. Both ixekizumab and secukinumab are monoclonal antibody IL-17A inhibitors (IL-17Ai) and are also approved for administration by SC injection in treating adults with active PsA [7, 8]. The US FDA-approved dosing regimens in PsA are 160 mg (two 80-mg injections) at Week 0, then 80 mg Q4W for ixekizumab [7], and 150 mg Q4W (with or without a loading dose of 150 mg at Weeks 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4), with possible maintenance dose escalation to 300 mg Q4W for secukinumab [8].

Given the multidomain effects and chronic nature of PsA, maintaining persistence with an effective treatment is critical to maximizing the treatment benefit. In clinical practice, many factors may influence patient persistence with a particular therapy, including effectiveness, adverse effects, and personal preferences regarding mode and frequency of administration [9]. With the availability of several bDMARD treatment options for PsA with distinct mechanisms of action, information related to the likelihood of long-term on-label persistence with treatment can be beneficial in shared decision-making for patients and their health care providers.

In the 1-year DISCOVER-1 and 2-year DISCOVER-2 studies, 91% [10] and 90%, [11], respectively, of participants randomized to guselkumab Q8W completed treatment through the end of the study. Real-world data evaluating treatment persistence for guselkumab [12] in patients with PsA are limited owing to the relatively recent approval for this patient population. Among patients with PsA who were enrolled in the CorEvitas PsA/Spondyloarthritis (SpA) Registry and initiated guselkumab Q8W, nearly 80% remained persistent with this dosing regimen through 6 months [12]. Comparative analyses for bDMARDs to date have primarily evaluated persistence versus TNF inhibitors (TNFi). A recent claims-based analysis compared treatment persistence, in accordance with FDA-approved dosing regimens, for patients with PsA who had newly initiated either guselkumab or their first SC TNFi. At 12 months, patients in the guselkumab cohort were 3× more likely than those in the SC TNFi cohort to remain persistent with on-label treatment [13]. Using similar methods, the current study compared the treatment persistence of patients with PsA receiving on-label dosing regimens of either guselkumab or their first SC IL-17Ai (ixekizumab and secukinumab).

Methods

Data Source

IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus is a health plan claims database of predominantly commercially insured patients that comprises fully adjudicated claims for inpatient and outpatient services, including outpatient prescription drugs. It contains information such as dates of service, demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, and geographic region), and health plan enrollment start and stop dates. The IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus database encompasses information from more than 215 million unique enrollees across the US, with over 95 million individuals having both medical and pharmacy benefits (40 million individuals in the most recent 10 years), providing a diverse representation of geographic zones, employers, payers, health care providers, and therapeutic specialties.

The IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus database, used under license for this study, complies with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations. The data obtained from these analyses were de-identified; thus, no Institutional Review Board approval was required. Data for this study were collected between July 14, 2019, and December 31, 2022, to allow for 12 months of data availability for the assessment of baseline patient characteristics prior to guselkumab FDA approval for the treatment of active PsA (i.e., July 13, 2020).

Study Design and Population

This retrospective cohort analysis evaluated treatment persistence of adults with PsA receiving either guselkumab or their first SC IL-17Ai (secukinumab or ixekizumab). The index date represents initiation of the treatment under study and was defined as the date of the first claim for guselkumab or SC IL-17Ai during the intake period. Many commercial insurance plans require preauthorization for bDMARDs to assure that the medications will be used for their intended purpose consistent with FDA-approved indications. Because all three medications under study are approved for patients with active PsA, initiation of these therapies was considered a proxy for active disease. The intake period began July 14, 2020, following FDA approval for guselkumab, and ended June 30, 2022, providing the potential for ≥ 6 months of follow-up time prior to the end of data availability, December 31, 2022. Baseline characteristics were determined during the 12-month period prior to treatment initiation. On-label persistence was assessed from the index date until the end of continuous insurance eligibility or end of data availability, whichever occurred first.

Patients were included in these analyses if they were aged ≥ 18 years; had ≥ 12 months of continuous insurance eligibility before the index date; and had ≥ 2 claims with a diagnosis of PsA (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] code: L40.5x) ≥ 30 days apart during the 12-month period up to and including the index date and ≥ 1 prescription claim for PsA medications of interest, guselkumab, ixekizumab, or secukinumab, consistent with a previously validated algorithm for identifying patients with PsA (Fig. 1) [14]. Patients were excluded from the study population if they had claims for > 1 index agent on the index date or ≥ 1 claim for any of the index agents (guselkumab, ixekizumab, secukinumab) during the period of continuous insurance eligibility prior to the index date.

Fig. 1.

Study schema. aThe IQVIA™ Health Plan Claims Data is comprised of fully adjudicated claims for inpatient and outpatient services and outpatient prescription drugs, offering a diverse representation of geographic zones, employers, payers, providers, and therapy areas. bA validated algorithm for identifying patients with PsA in US claims data was used. cPatients could be biologic-naïve or biologic-experienced during baseline but were naïve to treatment with guselkumab or SC IL-17Ai (i.e., ixekinumab or secukinumab). dPatients in the SC IL-17Ai cohort were newly initiated within the class. eDiagnoses for PsA include claims on the index date and were identified based on ≥ 2 PsA diagnoses (ICD-10-CM code L40.5x) ≥ 30 days apart and ≥ 1 prescription claim for a PsA-related medication (i.e., guselkumab or SC IL-17Ai). GUS, guselkumab; ICD-10-CM, International Classification of Disease, 10th revision, Clinical Modification; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; SC IL-17Ai, subcutaneous interleukin-17A inhibitor

Patients were also excluded if they had ≥ 1 claim with a diagnosis for other potentially confounding rheumatic conditions: ankylosing spondylitis (ICD-10 code: M45.x), other inflammatory arthritides (i.e., gout [ICD-10 codes: M10, M1A], calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease [CPPD; ICD-10 codes: M11.20, M11.80], nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis [ICD-10 code: M45.A], post-infectious and reactive arthritis [ICD-10 code: M02.x]), other spondylopathies (ICD-10 code: M48), rheumatoid arthritis (ICD-10 codes: M05, M06, M08, M12), systemic connective tissue disorders (ICD-10 codes: M30-M35.x), relapsing polychondritis (ICD-10 code: M94.1), or unspecified connective tissue disease (ICD-10 code: L94.9).

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analyses

The primary outcome of these analyses was the length of on-label persistence with the index agent (guselkumab or SC IL-17Ai), defined as the absence of treatment discontinuation or any dose escalation/reduction inconsistent with the respective FDA-approved SC dosing instructions. All three agents under study are approved for adults with active PsA as well as adults with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. The FDA-approved dosing regimen for guselkumab [4] is SC injections of 100 mg at Weeks 0, 4, and then Q8W. The FDA-approved PsA dosing regimen for ixekizumab [7] is 160 mg (two 80-mg injections) at Week 0, then 80 mg Q4W; for patients with a prior diagnosis of psoriasis, a dosing regimen of 160 mg (two 80-mg injections) at Week 0, then 80 mg at Weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 and Q4W was classified as on-label in this analysis. The FDA-approved SC secukinumab [8] dosing regimen for patients with PsA is 150 mg Q4W or 150 mg Q4W with a loading dose of 150 mg at Weeks 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 with possible dose escalation to 300 mg Q4W. Additionally, for patients with a prior diagnosis of psoriasis, secukinumab dosing regimens of 300 mg Q4W or 300 mg at Weeks 0, 1, 2, and 3 and Q4W were classified as on label in the current analysis.

Treatment discontinuation was defined as twice the longest duration of time between administrations according to the FDA-approved dosing of each index agent. Because loading doses are administered at shorter intervals relative to maintenance doses, the longest interval permitted with the FDA-approved label was selected for determining treatment gaps. Thus, treatment gaps were defined as 112 days (56 days × 2) for guselkumab and 56 days (28 days × 2) for ixekizumab and secukinumab. Given the potential discrepancy between reported days of supply and the interval between claims in administrative databases, caused by restrictions on the maximum days of supply imposed by some health plans [15], the days of supply were imputed for both medical and pharmacy claims in the guselkumab cohort. For guselkumab, the days of supply from medical claims were imputed as 28 days for the first claim and 56 days for subsequent claims, in accordance with the FDA-approved dosing regimen. For guselkumab pharmacy claims, the days of supply were imputed as 28 days for the first claim and for subsequent claims imputed as 28 days if the time to next claim was < 42 days, 56 days if the time to next claim was 42–70 days, and 84 days if the time to next claim was > 70 days. Pharmacy claims for SC IL-17Ai are typically consistent with approved labeling; therefore, reported days of supply was used for SC IL-17Ai with no imputation. Additionally, there is no Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code for SC IL-17Ai in medical claims; thus, there were no medical claims for these treatments. Two sensitivity analyses were conducted. The first utilized a treatment gap of 1 × the recommended dosing interval per the FDA-approved label (56 days for guselkumab and 28 days for SC IL-17Ai), and the second utilized a fixed gap of 84 days for both cohorts.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics were assessed during the period of 12-month continuous insurance eligibility prior to the index date. The classification of patients as biologic-experienced (i.e., prior exposure to TNFi, ustekinumab, abatacept, or risankizumab) or biologic-naïve status was based on biologic use during the baseline period. To reduce the impact of confounding effects inherent in differing baseline characteristics in the guselkumab and SC IL-17Ai cohorts, propensity score weighting based on the standardized mortality ratio (SMR) approach was used. Balanced variables were defined as a standardized difference between cohorts of < 10% [16].

Kaplan-Meier (KM) analysis adjusted for propensity score weights was performed to determine the proportions of patients who were persistent with on-label treatment during the 12-month follow-up period. The relative likelihood (expressed as a hazard ratio [HR]) of patients remaining persistent with on-label treatment with guselkumab relative to SC IL-17Ai was assessed over time; patients were censored when they discontinued treatment or their dose changed to one inconsistent with FDA-approved labeling. If discontinuation was not observed, patients were censored at the earliest of the date of first observed off-label claim (i.e., dose escalation or reduction relative to FDA-approved dosing, reflected as a change in interval between administrations or change in the number of injections per claim) or the last day of index agent supply before the end of the follow-up period. Persistence in the weighted cohorts was compared at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months with Cox proportional hazard models. HRs and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported for each time point.

Results

Study Cohorts and Baseline Characteristics

In total, 3653 patients met the study selection criteria and were included in this analysis: 910 in the guselkumab cohort and 2743 in the SC IL-17Ai cohort (ixekizumab, 1010 [36.8%]; secukinumab, 1733 [63.2%]) (Fig. 2). Three patients in the SC IL-17Ai cohort with extreme weights were excluded from the comparison. Baseline demographic and disease characteristics were considered balanced (difference between cohorts < 10%) between the weighted treatment cohorts; baseline characteristics for both the unweighted and weighted cohorts are shown in Table 1. In the weighted guselkumab and SC IL-17Ai cohorts, respectively, the mean age (at index date) was 50.4 and 50.2 years, 60.4% and 59.4% of patients were female, 51.9% and 52.5% had received prior bDMARD therapy, and 22.5% and 18.1% had received prior tsDMARD therapy. Hyperlipidemia was the most common comorbidity, occurring in 34.7% of patients in the guselkumab cohort and 34.8% in the SC IL-17Ai cohort; 1.4% and 1.1%, respectively, had IBD, and no patient in either cohort had uveitis. There were no significant differences between the guselkumab and SC IL-17Ai cohorts in the proportions of patients with diagnoses of obesity, fatigue, liver disease, or depression (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Identification of the study population of patients with PsA receiving guselkumab or an SC IL-17Ai. aFirst guselkumab or SC IL-17Ai claim during intake period (July 14, 2020–June 30, 2022). bThe SC IL-17Ai cohort is defined as patients with an index claim for an SC IL-17Ai (i.e., ixekizumab or secukinumab). cNumbers of patients excluded sequentially among those remaining after the prior criterion was applied are reported. dBefore index date. eOn the index date. fRheumatic diseases included ankylosing spondylitis, other inflammatory arthritides, other spondylopathies, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic connective tissue disorders, relapsing polychondritis, or unclassified connective tissue disease occurring in the 12-month baseline period preceding the index date. Dx diagnosis, GUS guselkumab, PsA psoriatic arthritis, SC IL-17Ai subcutaneous interleukin-17A inhibitor

Table 1.

Unweighted and weighted baseline characteristics of patients in the guselkumab and SC IL-17Ai cohorts

| Mean ± SD [median] or n (%) | Unweighted cohorts | Weighted cohortsa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guselkumab | SC IL-17Ai | Standard difference | Guselkumab | SC IL-17Ai | Standard difference | |

| N = 910 | N = 2743 | N = 910 | N = 2740 | |||

| Age at index date, years | 50.4 ± 11.1 [52.0] | 50.3 ± 11.1 [51.0] | 0.1 | 50.4 ± 11.1 [52.0] | 50.2 ± 11.3 [51.0] | 0.2 |

| Female | 60.4 | 59.8 | 0.6 | 60.4 | 59.4 | 1.0 |

| Region of residence at index date | ||||||

| South, unknown | 55.2 | 47.2 | 8.0 | 55.2 | 54.6 | 0.6 |

| Midwest | 20.5 | 23.5 | − 3.0 | 20.5 | 21.0 | − 0.5 |

| Northeast | 14.0 | 16.4 | − 2.4 | 14.0 | 14.7 | − 0.7 |

| West | 10.3 | 12.9 | − 2.6 | 10.3 | 9.7 | 0.7 |

| Insurance type at index date | ||||||

| Preferred provider organization | 77.8 | 72.6 | 5.2 | 77.8 | 75.3 | 2.5 |

| Health maintenance organization | 10.4 | 15.6 | − 5.2 | 10.4 | 14.8 | − 4.4 |

| Otherb | 11.8 | 11.8 | 0.0 | 11.8 | 9.9 | 1.9 |

| Year of index date | ||||||

| 2020 | 13.2 | 23.0 | − 9.8 | 13.2 | 12.9 | 0.3 |

| 2021 | 53.6 | 52.8 | 0.8 | 53.6 | 52.7 | 0.9 |

| 2022 | 33.2 | 24.2 | 9.0 | 33.2 | 34.4 | − 1.2 |

| Time between latest observed PsA diagnosis to index date, months | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 1.2 ± 1.5 | 0.1 | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 0.0 |

| Quan− CCI | 0.6 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 1.3 | 0.0 |

| Comorbiditiesc | ||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 34.7 | 37.0 | − 2.2 | 34.7 | 34.8 | − 0.1 |

| Osteoarthritis | 29.7 | 33.0 | − 3.3 | 29.7 | 29.1 | 0.6 |

| Diabetes | 16.4 | 15.3 | 1.1 | 16.4 | 16.6 | − 0.2 |

| IBDd | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 0.4 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2.5 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 2.5 | 2.7 | − 0.2 |

| Uveitis | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – |

| Psoriasis | 86.5 | 76.2 | 10.3 | 86.5 | 87.6 | − 1.1 |

| Smoking | 9.9 | 11.7 | − 1.8 | 9.9 | 9.2 | 0.7 |

| Any prior PsA treatment | ||||||

| bDMARDse | 51.9 | 60.9 | 9.1 | 51.9 | 52.5 | − 0.6 |

| 1 | 43.6 | 49.4 | − 5.8 | 43.6 | 44.0 | − 0.4 |

| ≥ 2 | 8.2 | 11.5 | − 3.2 | 8.2 | 8.5 | − 0.2 |

| csDMARDsf | 30.0 | 32.4 | − 2.4 | 30.0 | 31.0 | − 1.0 |

| tsDMARDsg | 22.5 | 16.2 | 6.3 | 22.5 | 18.1 | − 4.5 |

| JAKi | 7.4 | 4.2 | 3.2 | 7.4 | 4.7 | 2.7 |

| Non-narcotic analgesics | 3.6 | 3.0 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 0.1 |

| Corticosteroids | 43.1 | 44.8 | − 1.7 | 43.1 | 44.2 | − 1.2 |

| Opioids | 32.4 | 31.5 | 0.9 | 32.4 | 32.6 | − 0.2 |

b/cs/tsDMARDs biologic/conventional synthetic/targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, CCI Charlson comorbidity index, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, ICD-10 International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, IL-17Ai interleukin-17A inhibitor, JAKi Janus kinase inhibitor, PsA psoriatic arthritis, SC subcutaneous, SD standard deviation

aPropensity score weighting based on the standardized mortality ratio weighting approach was used to adjust for differences in baseline characteristics between the guselkumab and SC IL-17Ai cohorts. Weights were estimated using a multivariable logistic regression model. Baseline covariates were age at index date; sex; region; insurance plan type; index year and half; relationship to primary beneficiary (e.g., self, spouse, child); presence of psoriasis (ICD-10:L40.x, excluding L40.5), other autoimmune diseases (IBD), and comorbidities;c Quan-CCI; and prior use of non-narcotic analgesics, corticosteroids, opioids, and other PsA treatments.e,f,g

bIncludes point-of-service, consumer-directed health care, indemnity/traditional, and unknown plan type

cComorbidities included in the logistic regression model: cardiovascular disease (i.e., hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease), diabetes, osteoarthritis, IBD, and smoking

dIncludes unclassified IBD, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis

eIL-12/23 inhibitor (ustekinumab), anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 agent (abatacept), IL-23p19-subunit inhibitor (risankizumab), subcutaneous tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, and golimumab), and intravenous tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (infliximab, infliximab biosimilars, and golimumab). The proportions of patients with 1 and ≥ 2 bDMARDs are reported among those with any bDMARD use

fMethotrexate, leflunomide, cyclosporine, mycophenolate, azathioprine, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine

gApremilast, deucravacitinib, and Janus kinase inhibitors (upadacitinib, baricitinib, and tofacitinib)

On-Label Persistence

The mean follow-up times for the guselkumab and SC IL-17Ai cohorts were 14 months and 15 months, respectively. In the primary persistence analysis with treatment gaps defined as twice the longest duration consistent with FDA-approved labeling, the persistence rates in the weighted cohorts at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months were 89.8%, 80.0%, 71.3%, and 66.8%, respectively, in the guselkumab cohort and 81.2%, 67.1%, 57.5%, and 50.1%, respectively, in the SC IL-17Ai cohort (all log-rank p value < 0.001; Table 2). Patients in the guselkumab cohort were 1.85× more likely to remain persistent with on-label treatment at 12 months than patients in the SC IL-17Ai cohort (95% CI 1.6, 2.1; Fig. 3). The median time to discontinuation (i.e., the time at which 50% of patients had discontinued) was not reached in the guselkumab cohort and was 12.3 months in the SC IL-17Ai cohort.

Table 2.

On-label persistence through 12 months in weighted guselkumab and SC IL-17Ai cohorts: primary analysis (gap of twice the duration of time between administrations per US FDA-approved label)

| Cox proportional hazards modela | 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients at risk, n (%)b | ||||

| Guselkumab (N = 910) | 665 | 484 | 333 | 201 |

| SC IL-17Ai (N = 2740) | 1065 | 807 | 599 | 358 |

| Hazard ratios (95% CI) | 1.36 (1.18, 1.58) | 1.62 (1.41, 1.88) | 1.75 (1.52, 2.02) | 1.85 (1.60, 2.13) |

| Chi-square p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| KM persistence, % (95% CI) | ||||

| Guselkumab | 89.8 (84.2, 93.5) | 80.0 (74.9, 84.3) | 71.3 (65.9, 76.0) | 66.8 (61.1, 71.8) |

| SC IL-17Ai | 81.2 (76.7, 84.8) | 67.1 (61.5, 72.0) | 57.5 (51.0, 63.4) | 50.1 (42.6, 57.2) |

| Log-rank test p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Propensity score weighting based on the standardized mortality ratio weighting approach was used to adjust for differences in baseline characteristics between the guselkumab and SC IL-17Ai cohorts. Weights were estimated using a multivariable logistic regression model. Baseline covariates were age at index date; sex; region; insurance plan type; index year and half; relationship to primary beneficiary (e.g., self, spouse, child); presence of psoriasis (ICD-10:L40.x, excluding L40.5), other autoimmune diseases (inflammatory bowel diseasec), and comorbidities;d Quan-Charlson comorbidity index; and prior use of non-narcotic analgesics, corticosteroids, opioids, and other PsA treatments.e,f,g

bDMARD biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug, CI confidence interval, ICD-10 International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, KM Kaplan-Meier, PsA psoriatic arthritis, SC IL-17Ai subcutaneous interleukin-17A inhibitor, US FDA United States Food and Drug Administration

aCox proportional hazard models were used to compare risk of discontinuation between the weighted guselkumab and SC IL-17Ai cohorts

bPatients at risk of having the event are patients who have not had the event and have not been lost to follow-up at that point in time

cIncludes unclassified inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis

dCardiovascular disease (i.e., hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease), diabetes, smoking, and osteoarthritis

eInterleukin-12/23 inhibitor (ustekinumab), anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 agent (abatacept), interleukin-23p19-subunit inhibitor (risankizumab), subcutaneous tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, and golimumab), and intravenous tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (infliximab, infliximab biosimilars, and golimumab). The proportions of patients with 1 and ≥ 2 bDMARDs are reported among those with any bDMARD use

fMethotrexate, leflunomide, cyclosporine, mycophenolate, azathioprine, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine

gApremilast, deucravacitinib, and Janus kinase inhibitors (upadacitinib, baricitinib, and tofacitinib)

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of on-label persistence in weighted guselkumab and SC IL-17Ai cohortsa: primary analysis (gap of twice the duration of time between administrations per FDA label). aPropensity score (standardized mortality ratio) weighting was used to obtain a balanced sample. Weights were estimated using a multivariable logistic regression model. Baseline covariates were age at index date; sex; region; insurance plan type; index year and half; relationship to primary beneficiary (e.g., self, spouse, child); presence of psoriasis (ICD-10:L40.x, excluding L40.5), other autoimmune diseases (inflammatory bowel diseasec), and comorbidities;d Quan-Charlson comorbidity index; and prior use of non-narcotic analgesics, corticosteroids, opioids, and other PsA treatments.e,f,g. bWeighted Cox proportional hazard model was used to compare risk of discontinuation between the GUS and SC IL-17Ai cohorts. cIncludes unclassified inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis. dCardiovascular disease (i.e., hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease), diabetes, smoking, and osteoarthritis. eInterleukin-12/23 inhibitor (ustekinumab), anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 agent (abatacept), interleukin-23p19-subunit inhibitor (risankizumab), subcutaneous tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, and golimumab), and intravenous tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (infliximab, infliximab biosimilars, and golimumab). The proportions of patients with 1 and ≥ 2 bDMARDs are reported among those with any bDMARD use. fMethotrexate, leflunomide, cyclosporine, mycophenolate, azathioprine, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine. gApremilast, deucravacitinib, and Janus kinase inhibitors (upadacitinib, baricitinib, and tofacitinib). bDMARD biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug, CI confidence interval, FDA Food and Drug Administration, GUS guselkumab, HR hazard ratio, ICD-10 International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, SC IL-17Ai subcutaneous interleukin-17A inhibitor

Results of both sensitivity analyses were consistent with the primary analysis. In the first sensitivity analysis utilizing a treatment gap that was defined as the longest duration per FDA-approved label, weighted KM persistence rates (weighted) at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months were 83.0%, 70.8%, 60.4%, and 55.5%, respectively, in the guselkumab cohort and 72.2%, 54.2%, 43.3%, and 35.0%, respectively, in the SC IL-17Ai cohort (Supplemental Table 1). Patients receiving guselkumab were 1.70× more likely than those receiving an SC IL-17Ai to remain persistent with treatment at 12 months (95% CI 1.49–1.94; p < 0.001) (Supplemental Fig. 1); the median times to discontinuation were 16.7 months in the guselkumab cohort and 7.0 months in the SC IL-17Ai cohort. In the second sensitivity analysis, with a fixed gap of 84 days, KM persistence rates at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months in the weighted cohorts were 88.0%, 76.7%, 67.1%, and 62.9%, respectively, for the guselkumab cohort and 83.2%, 71.2%, 62.6%, and 57.0%, respectively, for the SC IL-17Ai cohort (Supplemental Table 2). At 12 months, patients in the guselkumab cohort were 1.22× more likely (95% CI 1.05–1.42; p = 0.009) to be persistent with treatment relative to those in the SC IL-17Ai cohort (Supplemental Fig. 2). The median times to discontinuation in the guselkumab and SC IL-17Ai cohorts were 22.0 and 18.5 months, respectively.

Discussion

Current GRAPPA treatment guidelines for adults with PsA support selecting therapies to address active disease domains in individual patients [2]. For certain patient populations, such as those with an inadequate response to conventional nonbiologic therapies or those with poor prognostic indicators, biologics are typically recommended [2]. Historically, TNFi have often been the first biologic prescribed [17]; however, with the approval of other biologics for PsA that target distinct mechanisms of action, patients and health care providers now have several treatment options available. Because long-term therapy is often required for patients with PsA, treatment persistence over time is an important consideration. Treatment persistence can be affected by both clinical effectiveness and safety as well as non-clinical factors, such as patient preferences related to frequency and mode of administration and financial/insurance considerations [18]. In addition to findings from randomized placebo-controlled trials, data from real-world studies can provide important information for consideration into the shared decision-making process.

In the phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled DISCOVER-2 trial of biologic-naïve patients, 90% of those randomized to the guselkumab Q8W dosing regimen completed study treatment through 2 years [11]. However, real-world data sources are needed to more comprehensively assess on-label treatment persistence as seen in routine clinical practice settings, apart from the restrictions of a typical randomized controlled trial. In a recent evaluation of participants enrolled in the CorEvitas PsA/SpA Registry who initiated on-label therapy with guselkumab for active PsA, nearly 80% remained persistent at 6 months [12]. These patients had statistically significant mean improvements in PsA disease activity, with nearly one-quarter achieving minimal disease activity [12], and many patients, 40% and 30%, in this cohort achieved meaningful improvements in patient-reported pain and physical function, respectively [19].

In separate US-based claims analyses of patients with PsA, 53% were persistent with ixekizumab [20] and 64% were persistent with secukinumab (not limited to on-label use) at 12 months [21]. In these analyses, persistence was estimated using treatment gaps of 60 and 90 days, respectively, and only one claim with a PsA diagnosis code was required for inclusion, in contrast to two claims in the present analysis. In another US claims-based analysis comparing persistence (fixed gap of 45 days) of ixekizumab and secukinumab in patients with PsA, 40% and 43% (p = 0.411), respectively, were persistent for ≥ 12 months; two claims with a PsA diagnosis code were required in the analysis, but dosing regimens were not restricted to those consistent with FDA labeling [22].

On-label persistence across several biologics was evaluated in patients with psoriasis and comorbid PsA, utilizing treatment gaps similar to those of the present analysis, with 77% of patients receiving guselkumab, 67% receiving ixekizumab, and 64% receiving secukinumab remaining persistent with treatment at 12 months [23]. The current analysis represents, to our knowledge, the first claims-based comparative analysis of on-label guselkumab and SC IL-17Ai treatment persistence in a PsA population. In this study of 3653 patients who had ≥ 2 claims with a PsA diagnosis and initiated either guselkumab or their first SC IL-17Ai, patients receiving guselkumab were significantly more likely (1.85 ×) to remain persistent with on-label treatment at 12 months than those who were receiving either ixekizumab or secukinumab, with separation between the cohorts observed at each prior timepoint assessed (3, 6, and 9 months). Of note, in the primary analysis (gap of 2 × the FDA-approved interval), < 50% of patients in the guselkumab cohort discontinued treatment before 12 months; thus, the median time to discontinuation was not reached. For patients in the SC IL-17Ai cohort, the median time to discontinuation was 12.3 months. The higher likelihood of remaining on treatment with guselkumab relative to an SC IL-17Ai at 12 months was further confirmed in both sensitivity analyses.

IL-23 and IL-17A are key cytokines in the pathogenesis of PsA, with IL-23 secretion by myeloid dendritic cells acting as an upstream regulator of IL-17A expression through activation of Th17 cells [24]. This pathway is known to drive inflammation that results in the psoriasis, synovitis, enthesitis, and dactylitis characteristic of PsA [25]. IL-23 has also been shown to act independently of this pathway in indirectly activating keratinocyte proliferation [26], and expression of IL-23 in the synovium has been associated with greater PsA disease activity [27]. Of note, recent in vitro studies have shown that as a result of its unique molecular attributes (i.e., having a wild-type Fc region), guselkumab can simultaneously bind CD64 on the myeloid cell surface and IL-23 secreted by these cells [28]. The ability of guselkumab to bind CD64 may enhance neutralization of IL-23 at the source in inflamed tissues, possibly influencing maintenance of clinical response and treatment persistence.

Safety considerations are also an important aspect of treatment decisions. Patients with PsA have an increased risk of IBD relative to the general population, and to address this concern, GRAPPA treatment guidelines currently recommend against using IL-17Ai in PsA patients with comorbid IBD owing to exacerbations of Crohn’s disease in randomized controlled trials of these therapies [2]. For these patients, the GRAPPA guidelines recommend choosing therapies with other mechanisms of action, including inhibition of IL-23. In a pooled analysis of 11 phase 2 and phase 3 studies of guselkumab in adults with either active PsA or moderate-to-severe psoriasis, no increased risk of IBD exacerbation was observed [29]. The concern of exacerbating comorbid IBD may influence treatment persistence with guselkumab for some patients.

The reported use of corticosteroids (including both oral medications and local injections) during the baseline period, ~ 40% of patients in both cohorts, appears to be inconsistent with the current treatment guidelines that recommend limited use of these medications at low doses and for short durations. Additionally, approximately one-third of patients in both cohorts had ≥ 1 claim for an opioid, which were not considered in the current treatment guidelines, during the baseline period. The usage of these medications has become more common among patients with PsA as seen in previous observational real-world analyses [30–32]. The key drivers of these prescribing patterns are unclear and require further study. Of note, in the current analysis, whether or not the patient actually used the medication as well as details of the dose and duration is unknown.

The current analysis is limited by the nature of claims-based analyses. Inaccuracies in medical coding used to identify diagnoses, procedures, and medications may have led to case misidentification. The information available from insurance claims cannot be used to determine whether patients used the medications as prescribed or the reasons for why patients discontinued their treatment. Additionally, treatment effectiveness cannot be discerned from the information available in this database. The accuracy of reported days of supply can be affected by insurance coverage restrictions. Although the imputation method utilized here (guselkumab cohort) is a common valid approach in claims-based persistence analyses, it may lead to misclassifications. Reporting of baseline characteristics, including medication history, were limited to the 12-month period prior to the index date; therefore, some patient characteristics may have been misclassified, including prior biologic status. The claims database utilized in this analysis primarily includes patients enrolled in commercial insurance plans in the US; therefore, these results may not be generalizable to patients in the US without commercial insurance or those in other countries.

Despite these limitations, there were several methodological features that strengthen the findings of the current analysis. Over 2700 patients were included in the SC IL-17Ai cohort, and considering the FDA approval for guselkumab for patients with active PsA in July 2020, the guselkumab cohort in the current study (N = 910) was relatively large. Additionally, propensity score weighting based on the SMR weighting approach to reduce the risk of confounding effects of outliers and to account for potential imbalances in baseline characteristics was used. Further increasing the reliability of the results, the criteria for identifying patients with active PsA in a US claims database was derived from a validated algorithm [14]. Additionally, results of the primary analysis (gap of 2 × the FDA-approved interval) were further confirmed in two separate sensitivity analyses (gap of 1 × the FDA-approved interval and fixed gap of 84 days).

Conclusions

The results reported here represent, to our knowledge, the first formal comparative US claims database study of on-label treatment persistence of guselkumab and SC IL-17Ai (ixekizumab or secukinumab) in patients with PsA. In the primary analysis as well as two sensitivity analyses, patients were significantly more likely to remain on treatment with guselkumab relative to SC IL-17Ai at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. Taken together with a previous study demonstrating significantly greater persistence through 12 months with on-label guselkumab compared with SC TNFi in patients with PsA, [13] these findings may provide useful insights for patients and their health care providers when considering treatment options for PsA.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Rebecca Clemente, PhD, of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, a Johnson & Johnson company, (the study sponsor) under the direction of the authors in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2022;175:1298-1304).

Author Contribution

Study design: Shannon A Ferrante, Natalie J Shiff, Timothy P Fitzgerald, Soumya D Chakravarty. Data collection, analysis, or interpretation: Philip J Mease, Shannon A Ferrante, Natalie J Shiff, Timothy P Fitzgerald, Soumya D Chakravarty, Jessica A Walsh. Drafted/revised the manuscript: Philip J Mease, Shannon A Ferrante, Natalie J Shiff, Timothy P Fitzgerald, Soumya D Chakravarty, Jessica A Walsh. Final approval for submission: Philip J Mease, Shannon A Ferrante, Natalie J Shiff, Timothy P Fitzgerald, Soumya D Chakravarty, Jessica A Walsh.

Funding

This analysis, the Rapid Service Fee, and the Open Access Fee were funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, a Johnson & Johnson company.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Philip J Mease has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Acelyrin, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Immagene, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, and Ventyx; speaker fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; and research grants from AbbVie, Acelyrin, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB. Shannon A Ferrante, Natalie J Shiff, Timothy P Fitzgerald, and Soumya D Chakravarty are or were employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, a Johnson & Johnson company at the time this work was performed and own stock in Johnson & Johnson. Natalie J Shiff also owns stock in or has owned stock in AbbVie, Gilead, Iovance, Novo-Nordisk, and Pfizer within the past 3 years and is currently an employee of Alpine Immune Sciences, A Vertex Company. Jessica A Walsh has received consulting fees for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB; and research funding from AbbVie, Merck, and Pfizer.

Ethical approval

The IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus database, used under license for this study, complies with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations. The data obtained from these analyses were de-identified; thus, no Institutional Review Board approval was required.

Footnotes

Prior presentation: These data have been presented, in part, at Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium 2024, Maui, Hawaii (February 14-17, 2024).

References

- 1.Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:957–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coates LC, Soriano ER, Corp N, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA): updated treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis 2021. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18:465–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh JA, Guyatt G, Ogdie A, et al. Special Article: 2018 American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation guideline for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:5–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tremfya: Package insert. Horsham: Janssen Biotech, Inc.; 2024.

- 5.Deodhar A, Helliwell PS, Boehncke WH, et al. Guselkumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis who were biologic-naive or had previously received TNFα inhibitor treatment (DISCOVER-1): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1115–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mease PJ, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB, et al. Guselkumab in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis (DISCOVER-2): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1126–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taltz: Package insert. Indianapolis: Eli Lilly and Company; 2022.

- 8.Cosentyx: Package insert. East Hanover: Novartis; 2023.

- 9.Sumpton D, Kelly A, Craig JC, et al. Preferences for biologic treatment in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a discrete choice experiment. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2022;74:1234–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritchlin CT, Helliwell PS, Boehncke WH, et al. Guselkumab, an inhibitor of the IL-23p19 subunit, provides sustained improvement in signs and symptoms of active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of a phase III randomised study of patients who were biologic-naive or TNFα inhibitor-experienced. RMD Open. 2021;7: e001457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McInnes IB, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of guselkumab, a monoclonal antibody specific to the p19 subunit of interleukin-23, through two years: results from a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74:475–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mease PJ, Ogdie A, Tesser J, et al. Six-month persistence and multi-domain effectiveness of guselkumab in adults with psoriatic arthritis: real-world data from the CorEvitas Psoriatic Arthritis/Spondyloarthritis Registry. Rheumatol Ther. 2023;10:1479–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh J, Lin I, Zhao R, et al. Comparison of real-world on-label treatment persistence in patients with psoriatic arthritis receiving guselkumab versus subcutaneous TNF inhibitors. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2024;11:487–99. 10.1007/s40801-024-00428-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H, Ford JA, Jin Y, et al. Validation of claims-based algorithms for psoriatic arthritis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2020;29:404–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu C, Ferrante SA, Fitzgerald T, Pericone CD, Wu B. Inconsistencies in the days supply values reported in pharmacy claims databases for biologics with long maintenance intervals. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2023;29:90–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Austin PC. Goodness-of-fit diagnostics for the propensity score model when estimating treatment effects using covariate adjustment with the propensity score. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17:1202–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mease P. A short history of biological therapy for psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:S104–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Y, Sudharshan L, Hsu MA, et al. Patient preferences associated with therapies for psoriatic arthritis: a conjoint analysis. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2018;11:408–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mease PJ, Ogdie A, Tesser J, et al. Improvements in patient-reported outcomes through six months of guselkumab treatment in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: real-world data from the CorEvitas Psoriatic Arthritis/Spondyloarthritis Registry. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2024;6:304–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murage MJ, Princic N, Park J, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and healthcare costs in patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with ixekizumab: a retrospective study. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2021;3:879–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oelke KR, Chambenoit O, Majjhoo AQ, Gray S, Higgins K, Hur P. Persistence and adherence of biologics in US patients with psoriatic arthritis: analyses from a claims database. J Comp Eff Res. 2019;8:607–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pizzicato LN, Vadhariya A, Birt J, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and use of adjunctive pain and anti-inflammatory medications among patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with IL-17A inhibitors in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2023;29:24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu C, Teeple A, Wu B, Fitzgerald T, Feldman SR. Treatment adherence and persistence of seven commonly prescribed biologics for moderate to severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in a US commercially insured population. J Dermatol Treat. 2022;33:2270–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marinoni B, Ceribelli A, Massarotti MS, Selmi C. The Th17 axis in psoriatic disease: pathogenetic and therapeutic implications. Auto Immun Highlights. 2014;5:9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fragoulis GE, Siebert S. The role of IL-23 and the use of IL-23 inhibitors in psoriatic arthritis. Musculoskelet Care. 2022;20(Suppl 1):S12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan JR, Blumenschein W, Murphy E, et al. IL-23 stimulates epidermal hyperplasia via TNF and IL-20R2-dependent mechanisms with implications for psoriasis pathogenesis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2577–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Celis R, Planell N, Fernández-Sueiro JL, et al. Synovial cytokine expression in psoriatic arthritis and associations with lymphoid neogenesis and clinical features. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGonagle D, Atreya R, Abreu M, et al. Guselkumab, an IL-23p19 subunit–specific monoclonal antibody, binds CD64+ myeloid cells and potently neutralises IL-23 produced from the same cells. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82:1128–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strober B, Coates LC, Lebwohl MG, et al. Long-term safety of guselkumab in patients with psoriatic disease: an integrated analysis of eleven phase II/III clinical studies in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Drug Saf. 2024;47:39–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hunter T, Nguyen C, Birt J, et al. Pain medication and corticosteroid use in ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis in the United States: a retrospective observational study. Rheumatol Ther. 2021;8:1371–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor MT, Noe MH, Horton DB, Barbieri JS. Trends in opioid prescribing at outpatient visits for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:200–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheahan A, Anjohrin S, Suruki R, Stark JL, Sloan VS. Opioid use surrounding diagnosis and follow-up in patients with ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis: Results from US claims databases. Clin Rheumatol. 2024;43:1897–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.