Abstract

Introduction: Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare, chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by persistent symptoms and sudden flares of painful sterile pustules, sometimes accompanied by systemic inflammation. Patients with GPP experience chronic disease burden even when not experiencing flares. There is an unmet need for guidelines on continuous long-term management of this disease. Areas Covered: This review summarizes existing literature describing the chronic disease burden of GPP, the persistence of symptoms and effects on quality of life (QoL) when patients are not experiencing a flare, the recurring nature of GPP flares, and the high prevalence of chronic comorbidities. We also present an overview of results from the EFFISAYIL® 2 study, which was the first randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial to systematically evaluate continuous management with subcutaneous spesolimab, a first-in-class anti-interleukin-36 receptor monoclonal antibody specifically designed to treat GPP. Expert Opinion: An unmet need in GPP is the establishment of guidelines for chronic disease management, including measures for treating GPP between flares, flare prevention, and long-term disease control. Treatment strategies should mitigate both the persistent disease burden and potentially life-threatening flare episodes. Intravenous spesolimab is currently the only FDA-approved medication to treat GPP flares, and subcutaneous spesolimab is the only FDA-approved medication to treat GPP when patients are not experiencing a flare. Guidelines should aim to advance the recognition of GPP as a chronic disease and emphasize prompt diagnosis and timely access to FDA-approved therapies according to the diagnostic criteria established by the International Psoriasis Council and the National Psoriasis Foundation.

Keywords: pustular psoriasis, rare disease, chronic disease, spesolimab, expert opinion

Plain Language Summary

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a skin condition that causes blisters filled with pus over large areas of the body. People living with GPP have painful flareups, which can be life-threatening if they are not treated. GPP seriously affects quality of life, even when the person is not currently having a flareup. Right now, there is only one medicine, spesolimab, that is approved to treat GPP. However, researchers and doctors still do not understand the best ways to treat GPP flareups over the long term or what advice to give people living with long-term GPP. This report gives an overview of current research on GPP and what still needs to be studied to help people with this condition. This report also explains the results of a recent study called EFFISAYIL® 2. The study showed that one year of spesolimab treatment reduced the number of flareups in people with GPP. Research still needs to be done on how to help people with GPP at all times, how to prevent flareups from coming back, and how to control the disease over a long period of time.

Introduction

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by persistent symptoms and sudden flares of painful sterile pustules, which may be accompanied by systemic inflammation. 1 The clinical course of GPP is unpredictable as flares may occur due to a particular trigger or without any evident cause. 1 Patients with GPP often experience significant chronic disease burden even in the absence of flares, including ongoing symptoms such as scaling and erythema.2-5 GPP is also associated with persistent effects on quality of life (QoL) and a high prevalence of chronic comorbidities.6-9 GPP flares can be life-threatening if left untreated. 5 The impairment of the functional skin barrier can result in the percutaneous loss of fluids, nutrients, and electrolytes, culminating in multisystem organ failure. 10 Patients with GPP flares are also at greater risk for sepsis due to the compromised defensive barrier functions of the skin. 10 Therefore, continuous treatment to prevent flares is critical.

The approval of spesolimab, a first-in-class, humanized, selective antibody that targets interleukin-36 receptor signaling, represented a milestone for the management of GPP. 11 It is the first approved treatment for GPP evaluated in statistically powered, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials (EFFISAYIL™ 1 and EFFISAYIL® 2).12,13 To date, intravenous (IV) spesolimab has been approved by regulatory authorities in 48 countries, including the United States, Japan, China, and the EU, to treat GPP flares in adults.11,14-16

However, current GPP guidelines do not address chronic disease management, including how to maintain long-term control of GPP and prevent future flares.3,17,18 This results in uncertainty regarding how to approach management of GPP after flare treatment. Here, we present an overview of current literature describing the chronic disease burden of GPP, with a focus on current unmet needs, and a discussion of future directions for long-term GPP management. We also present a review of EFFISAYIL® 2, which was the first randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial to systematically evaluate the long-term treatment of GPP between flares with spesolimab as a subcutaneous (SC) injection.

Review of Current Literature

GPP is a Chronic Persistent Disease

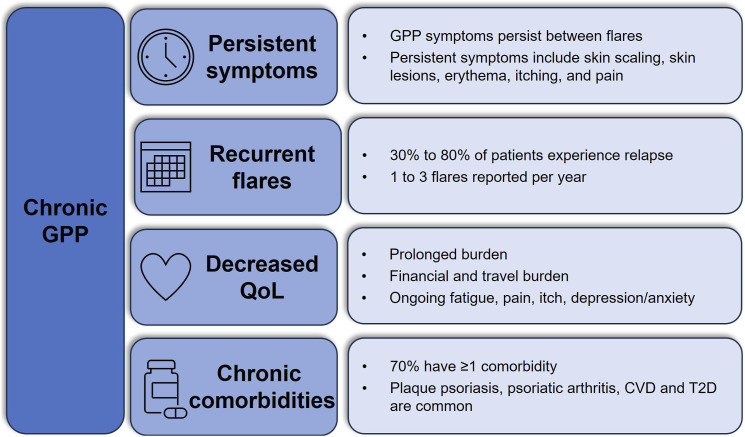

GPP presents as a chronic persistent disease with episodic recurrent flares (Figure 1).19,20 In a survey of 29 dermatologists experienced in GPP, 83% (24/29) agreed that patients experience continued disease burden post-flare, with symptoms such as skin scaling (76%), skin lesions (66%) and erythema (66%) commonly requiring up to 3 months to resolve. 5 This is consistent with a retrospective multicenter study where 74% (63/86) of patients had GPP symptoms at the time of their last visit, while another study found that 34% (32/95) of patients had persistent pustular lesions or erythematous thin plaques despite the use of off-label systemic therapies.2,7 Likewise, 40% (6/15) of patients in the placebo group of EFFISAYIL® 2 who were not experiencing a flare had ≥1 GPP Physician Global Assessment (GPPGA) total score of 2 (ranking of severity from 0-4) over the trial period. 21

Figure 1.

GPP is a chronic disease. CVD, cardiovascular disease; GPP, generalized pustular psoriasis; PsO, psoriasis; QoL, quality of life; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Patient-reported outcomes also reflect persistent disease in GPP. In an online survey of 66 patients with GPP in the United States, 24% (16/66) and 6% (4/66) reported symptoms of moderate and high severity, respectively, even when GPP flares were under control. 4 Approximately one-quarter of survey participants (27%, 18/66) identified as disabled. 4 Chronic symptoms of GPP, such as itching and pain, interfered with patient perception of treatment success. 22 In a cohort study that included 7 patients with GPP, patient-reported treatment satisfaction was significantly affected by ongoing disease severity. 22

Recurrent GPP Flares

Many patients with GPP experience periodic flares which can last over 3 months (Figure 1).2,9,23,24 While most patients experience an average of 1 flare per year, surveys have shown some patients experience 2-3 flares per year.4,5,25,26 Triggering factors for GPP flares are reported in 41%-85% of cases,1,7,27 though not all triggers are identifiable or avoidable, highlighting the need for consistent disease management to mitigate flare occurrence. Flare triggers can include medications (i.e., vaccines, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, and hydroxychloroquine), infections (bacterial and viral), pregnancy, menstruation, and corticosteroid withdrawal, with some evidence for flares triggered by seasonal changes, stress, and hypocalcemia.1,3,6,28-38 However, cases of GPP flares may also be idiopathic. 39 A recent review of real-world evidence (RWE) reported there was no identifiable cause for GPP flares in 15%-62% of patients. 6

Quality of Life

The chronic nature of GPP and prevalence of persistent symptoms detrimentally impacts patient QoL (Figure 1). A review of RWE on the humanistic burden of GPP reported a mean Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score from 7.8-12.4, indicating moderate to very large effects on QoL. 6 GPP can negatively impact a variety of physical, mental, and financial factors. 40 For instance, substantial costs may be associated with traveling long distances for specialist care, obtaining specialty medications, and undergoing long-term treatment. Patients may also face barriers to treatment due to misdiagnosis or prolonged insurance authorization procedures. Chronic symptoms such as fatigue, pain, and itching also contribute to poor QoL, and the debilitating anxiety or depression stemming from the unpredictability of GPP flares can affect patients’ mental and emotional well-being. When surveyed, patients reported that GPP impacted their daily lives even when flares were absent, with 36% reporting prolonged disease burden for months and 38% reporting the burden for years due to delays in diagnosis. 4 Furthermore, several respondents felt their physician did not understand the psychological and emotional or physical pain caused by their GPP. 4

Comorbidities

RWE studies have demonstrated a high prevalence of chronic comorbidities in patients with GPP that contribute to greater overall disease and mortality burden (Table 1). A Swedish population-based registry study of 1093 patients with GPP from 2004-2015 found that 70% of patients with GPP had comorbid conditions, in comparison with 46% of the general population, and 63% of patients with plaque psoriasis (PsO). 8 Increased comorbidity was associated with increased risk of mortality in patients with GPP,6,41 with the most common causes of mortality being septic shock/sepsis and cardiovascular complications. 9

Table 1.

Prevalence of Most Common Comorbidities in Patients With GPP.

| Comorbidity | Prevalence (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plaque PsO | 15-83 | 6,9,42 |

| Hypertension | 8-48 | 7-9,42 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidities | ||

| Ischemic heart disease | 26 | 42 |

| Congestive heart failure | 24 | 42 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 4-30 | 8,9,42 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 7-28 | 7-9,42 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 5-40 | 6-9,42 |

| Obesity | 7-59 | 6-8 |

GPP, generalized pustular psoriasis; PsO, psoriasis.

Furthermore, patients experiencing flares often require more frequent and prolonged hospitalization. In a Japanese retrospective cohort study, patients with GPP (N = 110) were more likely to require inpatient hospitalization compared to patients with plaque PsO (N = 20,254) or the general population (N = 436), with frequencies of 25% vs 6% vs 5%, respectively. 43 A French population-based study showed a median duration of stay of 8 days in the hospital and 12 days in the intensive care unit among 4195 patients with GPP. 42

Unmet Need For Chronic GPP Management

Prior to the availability of spesolimab, there was an unmet need for safe and effective treatment strategies for long-term control of GPP.44,45 Non-biologic systemic agents (i.e., retinoids, methotrexate, and cyclosporine) were often used to treat GPP flares, while several biologics gained approval for GPP in Japan based on small studies without validated measures for endpoints, and were used off-label in other countries.46,47 Patients were often switched from agent to agent, indicating a lack of evidence-based guidelines to manage GPP long-term. 48 Evidence from 2 US databases (Optum Clinformatics Data Mart and IBM MarketScan Commercial) from 2015-2020 showed that most patients did not receive systemic therapy within the first month of diagnosis, and treatments changed frequently over time, with low adherence over 2 years.49,50

Moreover, many non-GPP-specific treatments are associated with substantial toxicities that deter long-term off-label use. 51 Cyclosporine, while viable as a short-term therapy option, is associated with nephrotoxicity and hypertension with prolonged use. 52 Prolonged therapy with methotrexate can lead to liver and hematological toxicity, 52 and retinoids are associated with liver toxicity, alopecia, diffuse skeletal hyperostosis, and osteoporosis. 53 Both methotrexate and retinoids are contraindicated in pregnancy and should be used with caution in individuals of child-bearing potential.53,54 Methotrexate can also impact fertility in both sexes. 54 Withdrawal of systemic corticosteroids may trigger GPP flare, and the prolonged use of topical corticosteroids (particularly those of high potency) is associated with adrenal insufficiency, Cushing’s Syndrome, and osteoporosis.55,56 Prior to EFFISAYIL® 2, aside from some case reports and open-label studies, data were limited regarding the long-term management of chronic GPP.57-67

Discussion of EFFISAYIL® 2

EFFISAYIL® 2 was the first randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial in which GPP flare prevention was systematically evaluated. 13 The aim of the study was to assess the efficacy and safety of SC spesolimab for GPP flare prevention over 48 weeks. Patients with a history of GPP were randomized 1:1:1:1 to 3 groups receiving a SC dose of spesolimab (300 mg every 4 weeks [q4w] after a 600 mg loading dose; 300 mg every 12 weeks [q12w] after a 600 mg loading dose; and 150 mg every 12 weeks [q12w] after a 300 mg loading dose), and 1 group receiving placebo q4w (Figure 2(a)). Endpoints included time to first GPP flare by week 48, and the occurrence of ≥1 flare by week 48.

Figure 2.

EFFISAYIL® 2 study design (A) and likelihood of flare up to week 48 when treated with spesolimab versus placebo (B). 14 . CI, confidence interval; GPP, generalized pustular psoriasis; HR, hazard ratio; q4w, every 4 weeks; q12w, every 12 weeks. aNot significant. bNot tested (statistical significance was not seen in previous families in the statistical testing hierarchy).

A total of 123 participants were randomized (300 mg q4w, n = 30; 300 mg q12w, n = 31; 150 mg q12w, n = 31; placebo, n = 31). Patients were either Asian (64%; 79/123) or White (36%; 44/123), 62% (76/123) of patients were female, and the mean age was 40.4 years (SD, 15.8). At randomization, patients were required to have a GPPGA total score of 0 or 1, and 86.2% had a GPPGA total score of 1 indicating some skin severity at baseline. The treatment groups were comparable regarding baseline characteristics and had a similar mean GPPGA total score. IL36RN mutation occurred in 13% (4/31) of the placebo group, vs 23% (7/31) of the 150 mg q12w group, 32% (10/31) of the 300 mg q12w group, and 23% (7/30) of the 300 mg q4w group.

The 300 mg q4w spesolimab group showed significant improvement vs placebo in time to GPP flare (hazard ratio [HR], 0.16; 95% CI: 0.05-0.54; P = 0.0005) (Figure 2(b)). HRs were 0.35 (95% CI: 0.14-0.86; nominal P = 0.0057) in the 150 mg q12w group, and 0.47 (0.21-1.06; P = 0.027) in the 300 mg q12w group. By week 48, 35 patients had GPP flares: 23% (7/31) of patients in the 150 mg q12w group, 30% (9/31) in the 300 mg q12w group (exposure-adjusted), 13% (3/30) in the 300 mg q4w group (exposure-adjusted), and 52% (16/31) in the placebo group. All flares in the 300 mg q4w spesolimab group occurred by week 4 following the first 300 mg SC dose at week 4. A non-flat dose-response relationship was shown for all 3 doses of spesolimab compared with placebo, with statistically significant P-values for each predefined model (linear P = 0.0022, emax1 P = 0.0024, emax2 P = 0.0023, and exponential P = 0.0034). Additionally, using a one-sided α of 0.0063 (adjusted for multiplicity), 300 mg q4w spesolimab showed significant improvement compared with placebo in occurrence of ≥1 flare by week 48 (P = 0.0013).

In addition to its high efficacy, spesolimab had a favorable safety profile in EFFISAYIL® 2. The incidence of adverse events (AEs) was similar between patients receiving spesolimab and placebo (90% [84/93] vs 87% [26/30]), though the incidence of serious AEs was higher in the treatment arm (10% [9/93] vs 3% [1/30]). The most frequently reported serious AE was pustular PsO, which was reported in 3 patients (3.2%) across the 3 spesolimab dosage groups, but not in the placebo group. The incidence of AEs was not dose-dependent (Table 2). Infection rates were similar between the treatment and placebo arms (33% [31/93] vs 33% [10/30]), with no deaths or hypersensitivity reactions resulting in discontinuation.

Table 2.

Adverse Events in the Safety Population of EFFISAYIL® 2. 14

| n (%) | Spesolimab | Placebo (n = 30) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 mg q4w (n = 30) | 300 mg q12w (n = 31) | 150 mg q12w (n = 32) | ||

| Any AE | 26 (87) | 29 (94) | 29 (91) | 26 (87) |

| Severe AE | 5 (17) | 7 (23) | 6 (19) | 7 (23) |

| DRAE | 12 (40) | 11 (35) | 14 (44) | 10 (33) |

| Serious AE | 3 (10) | 1 (3) | 5 (16) | 1 (3) |

| AE resulting in discontinuation | 3 (10) | 2 (6) | 0 | 0 |

| AE resulting in death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

AE, adverse event; DRAE, investigator-assessed drug-related adverse event.

Subgroup analyses of EFFISAYIL® 2 demonstrated consistent efficacy of spesolimab in preventing flares in patients with and without IL36RN mutation, with the presence or absence of plaque PsO at baseline, and in all body mass index categories. 68 There were rapid improvements in DLQI among patients who received 300 mg q4w spesolimab compared with placebo, and this effect was sustained through week 48. 69

Evidence suggested that study participants were experiencing chronic GPP burden prior to treatment with spesolimab. Patients exhibited underlying GPP disease activity at baseline despite receiving biologic therapies, systemic therapies, or both. 13 In a subgroup analysis of 15/31 placebo-group patients who did not experience a flare over the study duration, a DLQI score of moderate (6-10) or very large (11-20) impact on QoL was reported in 67% (10/15) and 40% (6/15) of patients, respectively, during ≥1 study visit. 21 Moreover, 40% (6/15) of placebo-group patients who did not experience a flare had a GPPGA total score of 2 (ranking of severity from 0-4) during ≥1 study visit, with 4 patients reporting a score of 2 at ≥4 visits, and several patients reporting a moderate (7/15) or severe (3/15) score on the pain Visual Analog Scale during ≥1 study visit. 21 These data provide further evidence that GPP negatively affects patients who are not currently experiencing a flare or receiving adequate long-term management. The main limitation of EFFISAYIL® 2 was its limited participant diversity, as study participants were either Asian or White and predominantly female. Evidence from more patients and for a longer duration is needed to determine the long-term effects of continuous management with spesolimab in GPP. Overall, the results from EFFISAYIL® 2 confirmed that spesolimab was effective and safe to treat patients with GPP.

Conclusion

GPP is a chronic disease characterized by persistent disease burden, recurrent flares, high incidence of chronic comorbidities, and enduring impact on patient QoL. Thus, GPP requires a long-term continuous management approach. Improved recognition among healthcare providers of GPP as a chronic disease and a multidisciplinary treatment strategy are needed. Now that spesolimab is an approved IV and SC treatment for patients with GPP, more data are needed on the outcomes of multi-year spesolimab treatment, including the results of the EFFISAYIL® 2 open-label extension study. 70 Additionally, more information is needed regarding the effects of long-term management of GPP on patient QoL. The disease burden of GPP affects most patients beyond the duration of flares, and there remains a need for guidelines on how to manage chronic GPP, including flare prevention and treatment of sustained symptoms. Data from EFFISAYIL® 2 demonstrated that 300 mg q4w SC spesolimab after a 600 mg loading dose significantly reduced the risk of flare occurrence over 48 weeks vs placebo and had a reassuring safety profile, leading to FDA approval to treat GPP when not experiencing a flare in adult patients and pediatric patients aged 12 and over and weighing at least 40 kg.

Expert Opinion

A major unmet need in GPP is the establishment of guidelines for a multidisciplinary approach to the long-term management of GPP, including standardized measurements to assess disease severity, QoL and pain, flare treatment, flare prevention, and management of comorbid conditions. This review demonstrates that chronic management strategies should mitigate both the persistent disease burden patients experience between flares as well as the potentially life-threatening nature of GPP flares. It is important for GPP to be treated using FDA-approved medications because of its impact on QoL, high morbidity, and high mortality rate. Long-term management with SC spesolimab is a new FDA-approved strategy to treat GPP when not experiencing a flare, which could improve QoL and reduce or improve comorbidities in patients who experience recurring flares and chronic disease burden. Continuous management of GPP may also prevent hospitalization and other serious, potentially life-threatening consequences of flares. Unfortunately, access to treatment may be limited by barriers associated with insurance and the healthcare system. The establishment of official guidelines that recommend therapy for long-term management of GPP could help ease the logistical burden that causes delays in accessing treatment.

In addition to access to FDA-approved therapies, early detection and diagnosis of GPP are vital for providing timely treatment. The rarity and unpredictability of GPP flares and lack of awareness of standardized diagnostic criteria for GPP are obstacles to prompt diagnosis and treatment in settings where patients are most likely to present with flares (i.e., non-dermatologist settings such as the emergency department and the hospital). 71 Patients are frequently misdiagnosed with acute infection until negative cultures are confirmed, delaying flare treatment and underscoring the need for widespread physician education on the clinical appearance of GPP. Recent consensus statements from the International Psoriasis Council (IPC) and the National Psoriasis Foundation have established standardized diagnostic criteria for GPP, and both indicate that the potentially life-threatening nature of GPP necessitates immediate treatment.17,72 The IPC identified the primary clinical diagnostic criteria as “macroscopically visible sterile pustules on erythematous base and not restricted to the acral region or within psoriatic plaques.” Because ensuring timely access to FDA-approved therapies is critical to reducing morbidity and mortality during GPP flares, diagnosis should be made without relying on biopsy,17,72 nor should treatment be delayed by tuberculosis testing. 73 Currently, spesolimab is the only medication approved in the US to specifically treat GPP, based on its efficacy and safety profile. GPP flares may be treated with a single 900 mg IV infusion with an optional second infusion 1 week afterwards for persistent flare symptoms, and GPP may be treated while not experiencing a flare with a 600 mg SC loading dose followed by 300 mg SC injections q4w.11-13

For patients to receive optimal treatment, GPP must be recognized by dermatologists and physicians of all specialties as a chronic disease. Further long-term research and follow-up with patients with GPP will allow for better understanding of the chronic pathophysiology of GPP and may help identify additional flare triggers and how best to avoid them. More research on the long-term effects of GPP treatment is also needed, including a multi-year follow-up of patients taking spesolimab for long-term management, as well as other therapies.

The approval of SC spesolimab will enable patients to self-administer maintenance doses of the medication at home and alleviate the burden of traveling to clinics for IV infusions. Patients with GPP should have easier access to long-term therapies that relieve persistent symptoms and ease the anxiety and QoL burden associated with GPP. Ongoing and future studies should emphasize that GPP is a chronic disease associated with multiple comorbidities, and treatment guidelines should target the treatment of GPP both chronically and during flare episodes, as well as outline stepwise therapy approaches for the management of patients with and without chronic disease burden.

Acknowledgements

The authors met criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). The authors did not receive payment related to the development of this manuscript. Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (BIPI) was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as well as intellectual property considerations. Jia Gao, PharmD, of Elevate Scientific Solutions LLC, provided medical writing, editorial support, and formatting support, which were contracted and funded by BIPI.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: BE and MGL contributed to conception of this review article, interpretation of data, and writing the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: BE is an investigator for AbbVie, Amgen (previously Celgene), AnaptysBio, Bausch Health (formerly Valeant Pharmaceuticals), Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Menlo, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, UCB, and Vanda; and is a consultant for Amgen (previously Celgene), Arcutis, Bausch Health (formerly Valeant Pharmaceuticals), Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Novartis, and UCB. MGL is an employee of Mount Sinai and receives research funds from: Abbvie, Amgen, Arcutis, Avotres, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cara Therapeutics, Dermavant Sciences, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Inozyme, Janssen Research & Development, LLC, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, Sanofi-Regeneron, and UCB, Inc., and is a consultant for Almirall, AltruBio Inc., AnaptysBio, Apogee, Arcutis, Inc., AstraZeneca, Atomwise, Avotres Therapeutics, Brickell Biotech, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Castle Biosciences, Celltrion, Corevitas, Dermavant Sciences, EPI, Evommune, Inc., Facilitation of International Dermatology Education, Forte Biosciences, Foundation for Research and Education in Dermatology, Galderma, Genentech, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mindera, Pfizer, Sanofi-Regeneron, Seanergy, Strata, Takeda, Trevi, and Verrica.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: this work was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Ridgefield, CT, USA. The authors received no payment related to the development of the manuscript.

Ethical Statement

Ethical Approval

Research ethics approval was not required as no participants took part in this study.

ORCID iD

Boni Elewski https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1475-2874

References

- 1.Rivera-Diaz R, Dauden E, Carrascosa JM, Cueva P, Puig L. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review on clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2023;13(3):673-688. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00881-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kromer C, Loewe E, Schaarschmidt ML, et al. Drug survival in the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis: a retrospective multicenter study. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(2):e14814. doi: 10.1111/dth.14814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puig L, Choon SE, Gottlieb AB, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a global Delphi consensus on clinical course, diagnosis, treatment goals and disease management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(4):737-752. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reisner DV, Johnsson FD, Kotowsky N, Brunette S, Valdecantos W, Eyerich K. Impact of generalized pustular psoriasis from the perspective of people living with the condition: results of an online survey. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(suppl 1):65-71. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00663-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strober B, Kotowsky N, Medeiros R, et al. Unmet medical needs in the treatment and management of generalized pustular psoriasis flares: evidence from a survey of Corrona Registry dermatologists. Dermatol Ther. 2021;11(2):529-541. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00493-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhutani T, Farberg AS. Clinical and disease burden of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: a review of real-world evidence. Dermatol Ther. 2024;14(2):341-360. doi: 10.1007/s13555-024-01103-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choon SE, Lai NM, Mohammad NA, Nanu NM, Tey KE, Chew SF. Clinical profile, morbidity, and outcome of adult-onset generalized pustular psoriasis: analysis of 102 cases seen in a tertiary hospital in Johor, Malaysia. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(6):676-684. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lofvendahl S, Norlin JM, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Comorbidities in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: a nationwide population-based register study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88(3):736-738. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.09.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prinz JC, Choon SE, Griffiths CEM, et al. Prevalence, comorbidities and mortality of generalized pustular psoriasis: a literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(2):256-273. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inamadar AC, Palit A. Acute skin failure: concept, causes, consequences and care. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71(6):379-385. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.18007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spevigo [package insert] . Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim. Accessed January 31, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/761244s003lbl.pdf (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bachelez H, Choon SE, Marrakchi S, et al. Trial of spesolimab for generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(26):2431-2440. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2111563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morita A, Strober B, Burden AD, et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous spesolimab for the prevention of generalised pustular psoriasis flares (Effisayil 2): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2023;402(10412):1541-1551. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01378-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boehringer Ingelheim. SPEVIGO® approved for expanded indications in China and the US [press released]. https://www.boehringer-ingelheim.com/us/human-health/skin-and-inflammatory-diseases/gpp/spevigo-approved-expanded-indications-china-and-us. Accessed 4 April 2024.

- 15.Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency . New drugs approved in FY. 2022. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000267877.pdf. Accessed 8 April 2024.

- 16.European Medicines Agency . Spevigo [summary of product characteristics]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/spevigo-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 8 April 2024.

- 17.Armstrong AW, Elston CA, Elewski BE, Ferris LK, Gottlieb AB, Lebwohl MG. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a consensus statement from the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90(4):727-730. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.09.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu C-K, Huang Y-H, Chang C-H, et al. Taiwanese Dermatological Association consensus recommendations for the diagnosis, treatment, and management of generalized pustular psoriasis. Dermatol Sin. 2024;42(2):98-109. doi: 10.4103/ds.DS-D-24-00070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navarini AA, Burden AD, Capon F, et al. European consensus statement on phenotypes of pustular psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(11):1792-1799. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng M, Jullien D, Eyerich K. The prevalence and disease characteristics of generalized pustular psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(suppl 1):5-12. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00664-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strober B, Mostaghimi A, Anadkat M, et al. Measuring GPPGA, pain, symptom, and quality of life index scores in untreated generalized pustular psoriasis: results from the placebo group of the Effisayil-2 trial. J of Skin. 2024;8(2):s361. doi: 10.25251/skin.8.supp.361 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coscarella G, Falco GM, Palmisano G, et al. Low grade of satisfaction related to the use of current systemic therapies among pustular psoriasis patients: a therapeutic unmet need to be fulfilled. Front Med. 2023;10:1295973. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1295973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellinato F, Gisondi P, Marzano AV, et al. Characteristics of patients experiencing a flare of generalized pustular psoriasis: a multicenter observational study. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11(4):740. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11040740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin H, Cho HH, Kim WJ, et al. Clinical features and course of generalized pustular psoriasis in Korea. J Dermatol. 2015;42(7):674-678. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choon SE, Lebwohl MG, Turki H, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of generalized pustular psoriasis flares. Dermatology. 2023;239(3):345-354. doi: 10.1159/000529274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zema CL, Valdecantos WC, Weiss J, Krebs B, Menter AM. Understanding flares in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis documented in US electronic health records. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(10):1142-1148. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.3142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choon SE, Navarini AA, Pinter A. Clinical course and characteristics of generalized pustular psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(suppl 1):21-29. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00654-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dayani D, Rokhafrouz H, Balighi K. Generalized pustular psoriasis flare-up after both doses of BBIBP-CorV vaccination in a patient under adalimumab treatment: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2023;15(1):61-65. doi: 10.1159/000530074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elamin S, Hinds F, Tolland J. De novo generalized pustular psoriasis following Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47(1):153-155. doi: 10.1111/ced.14895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ennouri M, Bahloul E, Sellami K, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: clinical and genetic characteristics in a series of eight patients and review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(8):e15593. doi: 10.1111/dth.15593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang D, Liu T, Li J, Lu Y, Ma H. Generalized pustular psoriasis recurring during pregnancy and lactation successfully treated with ixekizumab. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(12):e15878. doi: 10.1111/dth.15878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isse Ali A, Mohamed Abdulkadir M, Ali Mumin H, Ibrahim Aden A, Sheikh Hassan M. Treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis in pregnancy with systemic corticosteroid: a rare case report. Ann Med Surg. 2022;82:104568. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kodali N, Blanchard I, Kunamneni S, Lebwohl MG. Current management of generalized pustular psoriasis. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32(8):1204-1218. doi: 10.1111/exd.14765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onsun N, Kaya G, Isik BG, Gunes B. A generalized pustular psoriasis flare after CoronaVac COVID-19 vaccination: case report. Health Promot Perspect. 2021;11(2):261-262. doi: 10.34172/hpp.2021.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pavia G, Gargiulo L, Spinelli F, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis flare in a patient affected by plaque psoriasis after BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, successfully treated with risankizumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(7):e502-e505. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samotij D, Gawron E, Szczech J, Ostanska E, Reich A. Acrodermatitis continua of hallopeau evolving into generalized pustular psoriasis following COVID-19: a case report of a successful treatment with infliximab in combination with acitretin. Biologics. 2021;15:107-113. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S302164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H, Jin H. Update on the aetiology and mechanisms of generalized pustular psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2021;31(5):602-608. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2021.4047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kara Polat A, Alpsoy E, Kalkan G, et al. Sociodemographic, clinical, laboratory, treatment and prognostic characteristics of 156 generalized pustular psoriasis patients in Turkey: a multicentre case series. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(8):1256-1265. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ly K, Beck KM, Smith MP, Thibodeaux Q, Bhutani T. Diagnosis and screening of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2019;9:37-42. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S181808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hawkes JE, Reisner DV, Bhutani T. Exploring the quality-of-life impact, disease burden, and management challenges of GPP: the provider and patient perspective [podcast]. Clin Cosmet Invest Dermatol. 2023;16:3333-3339. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S444238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ericson O, Lofvendahl S, Norlin JM, Gyllensvard H, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Mortality in generalized pustular psoriasis: a population-based national register study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(3):616-619. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.04.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viguier M, Bentayeb M, Azzi J, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a nationwide population-based study using the National health data system in France. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38(6):1131-1139. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okubo Y, Kotowsky N, Gao R, Saito K, Morita A. Clinical characteristics and health-care resource utilization in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis using real-world evidence from the Japanese medical data center database. J Dermatol. 2021;48(11):1675-1687. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gooderham MJ, Van Voorhees AS, Lebwohl MG. An update on generalized pustular psoriasis. Expet Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15(9):907-919. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1648209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reich K, Augustin M, Gerdes S, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: overview of the status quo and results of a panel discussion. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2022;20(6):753-771. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burden AD, Okubo Y, Zheng M, et al. Efficacy of spesolimab for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis flares across pre-specified patient subgroups in the Effisayil 1 study. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32(8):1279-1283. doi: 10.1111/exd.14824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krueger J, Puig L, Thaci D. Treatment options and goals for patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(suppl 1):51-64. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00658-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tada Y, Guan J, Iwasaki R, Morita A. Treatment patterns and drug survival for generalized pustular psoriasis: a patient journey study using a Japanese claims database. J Dermatol. 2024;51(3):391-402. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.17097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feldman SR, Bohn RL, Gao R, et al. Poor adherence to and persistence with biologics in generalized pustular psoriasis: a claim-based study using real-world data from two large US databases. JAAD Int. 2024;15:78-83. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2023.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feldman SR, Gao R, Bohn RL, et al. Varied treatment pathways with no defined treatment sequencing in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: a claims-based study. JAAD Int. 2024;15:59-61. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2023.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fujita H, Terui T, Hayama K, et al. Japanese guidelines for the management and treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis: the new pathogenesis and treatment of GPP. J Dermatol. 2018;45(11):1235-1270. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Balak DMW, Gerdes S, Parodi A, Salgado-Boquete L. Long-term safety of oral systemic therapies for psoriasis: a comprehensive review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2020;10(4):589-613. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00409-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aryal A, Upreti S. A brief review on systemic retinoids. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2017;8(9):3630-3639. doi: 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.8(9).3630-39 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Methotrexate [package insert] . Eatontown, NJ: West-Ward Pharmaceuticals Corp. Accessed January 31, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/040054s015,s016,s017.pdf (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benjegerdes KE, Hyde K, Kivelevitch D, Mansouri B. Pustular psoriasis: pathophysiology and current treatment perspectives. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2016;6:131-144. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S98954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Erdem B, Gonul M, Ozturk Unsal I, Ozdemir Sahingoz S. Evaluation of psoriasis patients with long-term topical corticosteroids for their risk of developing adrenal insufficiency, Cushing's syndrome and osteoporosis. J Dermatol Treat. 2024;35(1):2298880. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2023.2298880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burlando M, Salvi I, Paravisi A, Cozzani E, Parodi A. Severe generalized pustular psoriasis successfully treated with ixekizumab: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2022;14(3):326-329. doi: 10.1159/000526037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heyer S, Seiringer P, Eyerich S, et al. Acute generalized pustular psoriasis successfully treated with the IL-23p19 antibody risankizumab. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2022;20(10):1362-1364. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Imafuku S, Honma M, Okubo Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: a 52-week analysis from phase III open-label multicenter Japanese study. J Dermatol. 2016;43(9):1011-1017. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li J, Gao X, Ma L, Fang Y. Secukinumab for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis: a case report. Medicine (Baltim). 2023;102(18):e33693. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000033693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morita A, Okubo Y, Morisaki Y, Torisu-Itakura H, Umezawa Y. Ixekizumab 80 mg every 2 weeks treatment beyond week 12 for Japanese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis and erythrodermic psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;12(2):481-494. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00666-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morita A, Yamazaki F, Matsuyama T, et al. Adalimumab treatment in Japanese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: results of an open-label phase 3 study. J Dermatol. 2018;45(12):1371-1380. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saeki H, Nakagawa H, Nakajo K, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab treatment for Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis and generalized pustular psoriasis: results from a 52-week, open-label, phase 3 study (UNCOVER-J). J Dermatol. 2017;44(4):355-362. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sano S, Kubo H, Morishima H, Goto R, Zheng R, Nakagawa H. Guselkumab, a human interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody in Japanese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis and erythrodermic psoriasis: efficacy and safety analyses of a 52-week, phase 3, multicenter, open-label study. J Dermatol. 2018;45(5):529-539. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xue G, Lili M, Yimiao F, Miao W, Xiaohong Y, Dongmei W. Case report: successful treatment of acute generalized pustular psoriasis of puerperium with secukinumab. Front Med. 2022;9:1072039. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.1072039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamanaka K, Okubo Y, Yasuda I, Saito N, Messina I, Morita A. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in Japanese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis or erythrodermic psoriasis: primary analysis and 180-week follow-up results from the phase 3, multicenter IMMspire study. J Dermatol. 2023;50(2):195-202. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamasaki K, Nakagawa H, Kubo Y, Ootaki K. Efficacy and safety of brodalumab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis and psoriatic erythroderma: results from a 52-week, open-label study. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(3):741-751. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Warren R, Burden D, Choon SE, et al. Effect of subcutaneous spesolimab on the prevention of generalized pustular psoriasis flares over 48 weeks: subgroup analyses from the Effisayil 2 trial. J of Skin. 2023;7(6):s245. doi: 10.25251/skin.7.supp.245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gottlieb AB, Strober B, Kokolakis G, et al. Spesolimab rapidly improves quality of life in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis, as per dermatology life quality index scores: data from the Effisayil 2 trial. In: ePoster at: American academy of dermatology annual meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, 8-12 March 2024. https://eposters.aad.org/abstracts/51856. Accessed 11 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morita A, Choon SE, Bachelez H, et al. Design of Effisayil™ 2: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of spesolimab in preventing flares in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2023;13(1):347-359. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00835-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rivera-Diaz R, Epelde F, Heras-Hitos JA, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: practical recommendations for Spanish primary care and emergency physicians. Postgrad Med. 2023;135(8):766-774. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2023.2285730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Choon SE, van de Kerkhof P, Gudjonsson JE, et al. International consensus definition and diagnostic criteria for generalized pustular psoriasis from the International Psoriasis Council. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:758-768. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.0915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hackley M, Thampy D, Waseh S, et al. Increased risk of severe generalized pustular psoriasis due to tuberculosis screening delay for spesolimab initiation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90(2):408-410. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.09.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]