Although several studies have shown that US physicians make greater use of medical technologies than UK physicians, no study has examined variation in specialty referral rates, the step before specialised procedures. We compared rates of referral to specialists in the United Kingdom and the United States. To hold the effects of gatekeeping systems constant, we studied US managed care settings that used a structured referral process similar to that in the United Kingdom.

Participants, methods, and results

We included non-pregnant patients aged 0 to 64 years, with at least six months of enrolment on a health plan or general practice registration and at least one consultation with their primary care physician during 1996 (US) or 1997 (UK). The US sample comprised 384 693 patients from five health maintenance organisations. All US patients had been assigned physician gatekeepers, who authorised specialty referrals. We used the general practice research database for the UK sample (n=757,680).1

We measured referral rates as the annual percentage of patients with a new referral to a specialist physician. In the United Kingdom, general practitioners recorded whether each visit led to a referral. In the United States, patients with at least one visit to a specialist were considered to have had a specialty referral. To limit misclassification of follow up visits to a specialist as new referrals we did not count visits during 1996 (the study period) if the patient had also had a visit to the same type of specialist in 1995.

We used the Johns Hopkins adjusted clinical group system2 to develop a “treated morbidity index.” Patients in the same clinical group have a similar need for healthcare resources. For each adjusted clinical group category, we determined a referral rate for the largest US health maintenance organisation and then divided by the overall average referral rate for the plan to yield an index score. Higher scores indicate sicker patients, greater morbidity burden, and greater need for referral.

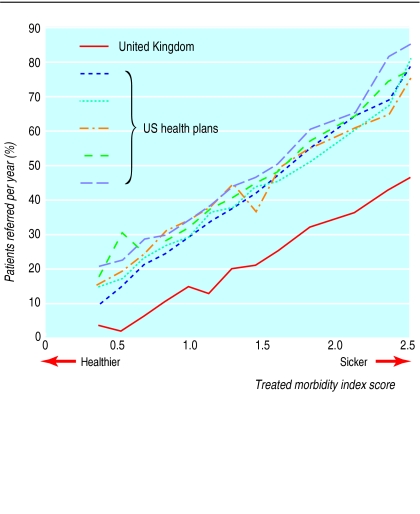

Across the five US health plans, 30.0% to 36.8% of patients per year were referred compared with 13.9% per year for the UK patients. The figure shows that the US health plans clustered closely around the same trend line and that US patients were referred more commonly than UK patients, regardless of the morbidity burden.

Comment

Among patients who visit their primary care physician, about one in three patients in the United States are referred to a specialist annually compared with one in seven in the United Kingdom. Our data do not provide information on whether the US rates are too high or the UK rates are too low. Nevertheless, the twofold difference in referral rates held true for the healthiest as well as the sickest patients.

The low availability of specialists, and resultant long waiting lists, in the United Kingdom is an important explanation for these differences. The supply of specialists in the United States exceeds that in the United Kingdom by twofold.3 Just 1% of US patients wait four months or longer for elective surgery compared with 33% of UK patients.4 General practitioners believe that waits for appointments with specialists threaten their capacity to deliver high quality care.5 Absence of waits is likely to have lowered the US physicians' referral thresholds.

Other possible explanations include a less intensive practice style among UK physicians, the common practice of self referral among US patients (even those in health maintenance organisations), and a broader scope of practice among UK physicians. Given the low rates of referral in the United Kingdom relative to the United States, it seems unlikely that referral guidelines, which have been proposed as a method to reduce pressure on UK outpatient services, will dramatically enhance specialty capacity by decreasing demand.

Supplementary Material

Figure.

Referral rate as a function of morbidity burden of patients. A treated morbidity index score was assigned to patients according to their adjusted clinical group category (groups are based on information on diagnosis, age, and sex). Higher scores indicate greater morbidity burden and greater need for specialty referrals

Acknowledgments

We thank Steven Foldes, Steve Parente, Terry Bernhardt, Carol Walters, Jeff Smith, Katharine Hiltunen, and Tom Brown for assisting us in the creation of the administrative databases. We also thank the management at the four US health insurance companies for their willingness to share their data. Sarah von Schrader, Tom Richards, Klaus Lemke, and Joyce Hines provided technical and administrative support in the United States. Barbara Starfield, Paul Nutting, Robert Reid, and Juan Gérvas provided comments on early versions of the manuscript. Cathy Hodgson provided technical and programming support in the United Kingdom.

Footnotes

Funding: This project was funded in part by a grant from the Commonwealth Fund. AM was also supported by a national primary care scientist award funded by the NHS Research and Development Directorate. CBF was supported in part by an independent scientist award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Competing interests: None declared.

See additional tables on bmj.com

References

- 1.Lawson DH, Sherman V, Hollowell J. The General Practice Research Database. QJM. 1998;91:445–452. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/91.6.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. The Johns Hopkins University ACG case-mix system. http://acg.jhsph.edu (accessed 2 Feb 2002).

- 3.Stoddard J, Sekscenski E, Weiner J. The physician workforce: broadening the search for solutions. Health Aff (Millwood) 1998;17:252–257. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.1.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donelan K, Blendon RJ, Schoen C, Davis K, Binns K. The cost of health system change: public discontent in five nations. Health Aff (Millwood) 1999;18:206–216. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.3.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McColl E, Newton J, Hutchinson A. An agenda for change in referral—consensus from general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:157–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.