Abstract

Neuroblastoma is a deadly pediatric cancer that originates from the neural crest and frequently develops in the abdomen or adrenal gland. Although multiple approaches, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, are recommended for treating neuroblastoma, the tumor will eventually develop resistance, leading to treatment failure and cancer relapse. Therefore, a firm understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying therapeutic resistance is vital for the development of new effective therapies. Recent research suggests that cancer-specific modifications to multiple subtypes of nonapoptotic regulated cell death (RCD), such as ferroptosis and cuproptosis, contribute to therapeutic resistance in neuroblastoma. Targeting these specific types of RCD may be viable novel targets for future drug discovery in the treatment of neuroblastoma. In this review, we summarize the core mechanisms by which the inability to properly execute ferroptosis and cuproptosis can enhance the pathogenesis of neuroblastoma. Therefore, we focus on emerging therapeutic compounds that can induce ferroptosis or cuproptosis, delineating their beneficial pharmacodynamic effects in neuroblastoma treatment. Cumulatively, we suggest that the pharmacological stimulation of ferroptosis and ferroptosis may be a novel and therapeutically viable strategy to target neuroblastoma.

Keyword: Neuroblastoma, Ferroptosis, Cuproptosis, Compounds

Introduction

Neuroblastoma (NB), the most common extracranial solid malignancy, is of sympathetic origin and is characterized by a heterogeneous clinical course ranging from a localized tumor to a spontaneous and widely metastatic disease [1–4]. NB accounts for 8–10% of all pediatric tumors and results in approximately 15% of cancer-related deaths in children [5]. Unique features of NB include the high frequency of metastatic disease at diagnosis, the early age of onset, and the tendency for spontaneous regression of tumors in infancy [6].

The main drivers of NB formation are underlying abnormalities in sympathoadrenal cells derived from neural crest cells [7]. Several germline and sporadic genomic rearrangements have been detected in NB, including MYCN [8], anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) [9], encoding lin 28 homolog B (LIN28B) [10], paired-like homeobox 2b (PHOX2B) [11], and polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 14 (GALNT14) [12]. The amplification of the MYCN oncogene is observed in 20% of all patients with NB, especially in patients who are resistant to therapy and have a poor prognosis [8, 13, 14]. Approximately 2% of NB cases appear to be hereditary, with ALK being the first gene identified to be responsible for familial NB [9, 15]. The specific pathogenesis of NB is still obscure in most cases, leading to limited efficacy in applying specific targeted approaches [16]. NB can be classified into three risk groups (low, intermediate, and high) depending on the extent of disease, age, histology, and presence of cytogenetic abnormalities [17, 18]. The treatment for high-risk NB remains challenging, and the current standard treatment model includes three treatment blocks: induction, consolidation, and maintenance [3, 19]. The consolidation block involves the administration of high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) and radiotherapy [20, 21]. Induction chemotherapy aims to reduce and shrink the tumor, in addition to reducing the risk of metastasis via chemotherapy and surgery [20, 21]. The maintenance block includes immunotherapy via differentiation therapy with 11‐cis retinol, an anti‐disialoganglioside (GD2) monoclonal antibody (mAb), and cytokines [20, 21]. Induction chemotherapy generally uses platinum compounds (cisplatin, carboplatin), cyclophosphamide, vincristine (COJEC), and etoposide [6, 7, 22–25], alongside topotecan (topoisomerase inhibitors) and anthracyclines in North America [26, 27]. These methods of chemotherapeutic induction are preferential inducers of apoptosis [22]. However, this type of pharmacological treatment generates chemotherapeutic drug resistance, hindering the eradication of NB and promoting relapse [4]. Hence, further exploration into the different mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of NB is needed to identify effective targets for the development of new targeted therapies.

Regulated cell death (RCD) is a ubiquitous process that is essential for restoring biological balance under stress and is essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis [28]. RCD includes apoptosis, programmed cell death (PCD), and regulated necrosis [28]. PCD is a type of RCD that can be activated by external factors and is highly regulated by a number of pathways and intracellular molecules [29]. Ferroptosis [30] and cuproptosis [31] are two newly identified types of PCD. Research has revealed that deficient activation of ferroptosis and cuproptosis is strongly associated with the pathogenesis of many diseases, including NB [32].

Thus, RCD is crucial in NB [33–35]. In this review, we critically discuss the core mechanisms by which nonapoptotic mechanisms of RCD, including ferroptosis and ferroptosis, interact with the pathogenesis and treatment resistance of NB. Next, we focus on therapeutic compounds that modulate RCD activity within NB, delineating their beneficial pharmacological effects. Overall, we suggest that pharmacologically targeting nonapoptotic RCD is a potent therapeutic strategy for treating NB.

Overview of Regulated Cell Death

Ferroptosis

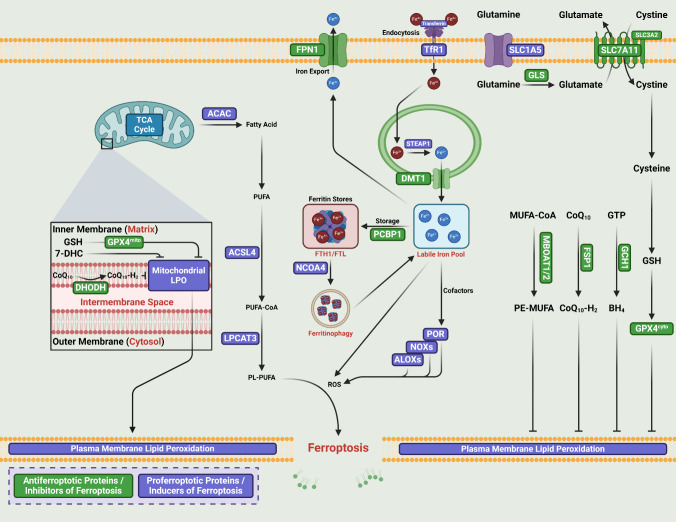

Ferroptosis is a nonapoptotic RCD induced by the iron-mediated oxidative modification of phospholipid membranes [30, 36, 37] (Fig. 1). An imbalance between ferroptosis defense and induction systems dictates the execution of ferroptosis [38]. The cellular antioxidant systems that directly neutralize lipid peroxides constitute the ferroptosis defense systems [39–41]. Five major ferroptosis defense systems with distinctive subcellular localizations have been identified, i.e., the SLC7A11–GPX4 (solute carrier family 7 member 11–glutathione peroxidase 4) axis [38, 42] and the FSP1–CoQH2 (ferroptosis suppressor protein 1–coenzyme Q10 ubiquinol) [43, 44], GCH1–BH4 (GTP cyclohydrolase 1–tetrahydrobiopterin) [45, 46], DHODH–CoQH2 (dihydroorotate dehydrogenase–dihydroubiquione) [47], and MBOAT1/2–MUFA (O-acyltransferase domain containing 1/2–monounsaturated fatty acids) systems [48]. Free iron accumulation and the inhibition of antioxidant systems are the two key initial signals that induce ferroptosis [49]. When iron-dependent reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxides (LPOs), the two ferroptosis-promoting factors, substantially override the inhibitory capacity of ferroptosis defense systems, phospholipid polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA-PLs) can be converted to peroxidized PUFA-PLs or phospholipid hydroperoxides (PUFA-PLs-OOH) in the membrane via both enzymatic lipid peroxidation (LPO) reactions and nonenzymatic Fenton reactions with the help of bioactive iron and the catalysis of oxidase [50, 51]. PUFA-PLs-OOH accumulate in cellular membranes and eventually cause rupture, resulting in ferroptosis [38].

Fig. 1.

Core mechanisms of ferroptosis

PUFA-PLs are the primary and major substrates for LPO [52]. Acyl-coenzyme A synthetase long chain family member 4 (ACSL4) catalyzes the ligation of CoA with free PUFAs, which include arachidonic acid (AA) and adrenic acid (AdA), to generate PUFA-CoAs in the enzymatic LPO pathway [53, 54]. Lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) then inserts acyl groups into lysophospholipids and incorporates PUFA-CoAs into PLs to produce PUFA-PLs [53, 55]. Arachidonate lipoxygenases (ALOXs) and cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR), two iron-dependent enzymes, work together with labile iron using O2 to generate PUFA-PLs-OOH from membranous PUFA-PLs through a peroxidation reaction [52, 56]. Iron functions as an essential cofactor for ALOXs and POR to perform a nonenzymatic Fenton reaction in the LPO pathway. ALOXs and POR promote LPO, the secondary products of which include 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and malondialdehyde (MDA), which induce pore formation at lipid bilayers, leading to ferroptotic cell death [57].

Cuproptosis

Copper functions as an essential micronutrient and trace metal required for life [58]. Redox-active Cu works as an essential key structural or catalytic cofactor for enzymes that are involved in a wide array of biological processes, including OXPHOS, connective tissue cross-linking, biocompound synthesis, iron homeostasis, signal transmission, and ROS detoxification, in almost all organisms [59, 60]. Cu can be cytotoxic, and an overload of Cu promotes Cu-mediated Fenton reactions, producing damaging ROS and disrupting iron‒sulfur cofactor function. Chronic or long-term exposure to copper results in toxicity, and increased intracellular copper leads to many diseases, including cancers. Cu plays vital roles in regulating tumor growth and metastasis [61]. However, the machinery underlying the toxicity and cell death induced by copper remains elusive.

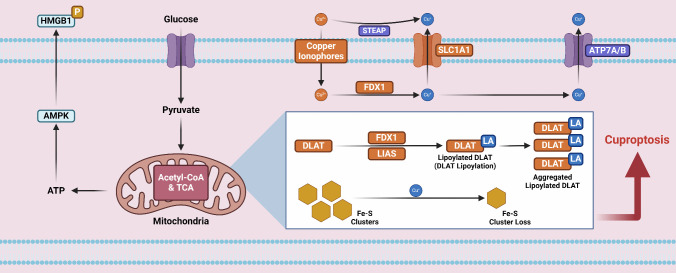

The current goal is to uncover how copper accumulation causes cellular toxicity, inducing copper-mediated cell death, i.e., cuproptosis, and how this process differs from pyroptosis, ferroptosis, necroptosis, and apoptosis [62]. Tsvetkov and colleagues coined the term “cuproptosis” in 2022 (Fig. 2) [31] based on the pioneering works that have shown that copper induces cell death [63] and promotes cancer cell death [64]. Lipoyl synthase (LIAS) and the mitochondrial enzyme ferredoxin (FDX1) were identified as key regulators of Cu toxicity [62], and disulfiram (DSF) was shown to have anticancer activity [65]. Copper-based anticancer compounds induce cell death [65], copper improves the antitumor activity of disulfiram [65], copper induces nonapoptotic programmed cancer cell death [65], elesclomol induces cancer cell apoptosis [65], and copper selectively transported to the mitochondria kills cancer cells [66]. The mechanism underlying how the Cu ionophore elesclomol (ES) exerts anticancer activity was revealed in 2019 [62]; in this context, Tsvetkov and colleagues described Cu-mediated cell death, revealing that ES increases the sensitivity of cancer cells to proteasome inhibitor-induced toxicity in a multiple myeloma mouse model. A mechanistic study revealed that ES-bound Cu2+ interacts with FDX1 to reduce Cu+2 to Cu+, leading to increased production of ROS [62, 67]. Gao reported that LPO mediates the lethality of ES [68]. Tsvetkov and colleagues named this unique form of Cu-mediated cell death cuproptosis in 2022 following this discovery, which is characterized by a loss of Fe-S proteins and the aggregation of lipoylated mitochondrial enzymes [31]. Disruption of specific mitochondrial metabolic enzymes plays a role in copper-mediated toxicity, greatly contributing to delineating how copper overload causes mitochondrial dysfunction [31]. Ionophores can transport excess intracellular Cu2+ into mitochondria, where it is reduced to Cu+ by FDX1. Increased Cu+ directly binds to lipoylated DLAT, causing lipoylated protein aggregation and destabilization of Fe-S cluster proteins, resulting in proteotoxic stress and subsequent cuproptosis [31]. Notably, genetic or pharmacological inhibition of ferroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis cannot halt ES-Cu complex-induced cell death in multiple cancer cell lines. The antioxidants N-acetylcysteine, ebselene, α-tocopherol, and JP4-039 fail to reverse ES-Cu-induced growth inhibition, indicating that ROS are not required for cuproptosis. However, the hydrophilic antioxidant glutathione (GSH) can inhibit ES-Cu-induced toxicity by chelating intracellular Cu, suggesting that cuproptosis differs from previously regulated cell death mechanisms [31]. Tsvetkov et al. revealed a strong link between mitochondria and copper toxicity. Accordingly, rotenone (an inhibitor of respiratory chain complex I), antimycin (an inhibitor of respiratory chain complex III), UK5099 (an inhibitor of mitochondrial pyruvate uptake), and genetic inhibition of complex I inhibit cuproptosis. Tsvetkov et al. reported that galactose-mediated mitochondrial respiration renders lung cancer cells more sensitive to ES-Cu-induced growth inhibition than cells that rely on glucose-induced glycolysis [31]. Hypoxia (1% O2) decreases the sensitivity of cancer cells to cuproptosis, whereas basal or adenosine 5′-triphosphate-linked respiration is not affected by ES-Cu in cancer cells. This discriminates cuproptosis from ferroptosis, namely, as a mechanism that requires glucose uptake and pyruvate oxidation. Thus, cuproptosis and ferroptosis are coupled to distinct alterations in mitochondrial function and energy metabolism. Taken together, these findings suggest that cuproptosis is a newly identified oxidative stress-independent, Cu-dependent, and mitochondria-induced cell death mechanism [69].

Fig. 2.

Basic core mechanisms of cuproptosis. The uptake of Cu2+ into cells occurs via solute carrier family 31 member 1 (SLC31A1) or copper ionophores. Cu2+ then binds selectively to lipoylated tricarboxylic acid cycle proteins and mediates Fe-S cluster protein instability to induce a toxic gain of function through mitochondrial proteotoxic stress, namely, copper-dependent oligomerization of lipoylated proteins, eventually leading to cell death. Elesclomol functions as a copper ionophore to transport copper into cells. The copper importers SLC31A1 and the copper exporter ATPase copper-transporting beta (ATP7B) can also regulate intracellular copper levels. Ferredoxin 1 (FDX1) can reduce Cu2+ to Cu+ and subsequently lipoylates mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle enzymes, especially dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase (DLAT), to promote Fe-S cluster protein loss. Copper-mediated damage to the mitochondrial respiratory chain causes hyperactivation of the energy sensor AMPK, which accelerates cuproptosis and the release of the proinflammatory mediator HMGB1. LA-DLAT, lipoylated DLAT; LIAS, lipoyl synthase

Role of Regulated Cell Death in the Development of Neuroblastoma

Role of Ferroptosis in the Genesis of Neuroblastoma

Oncogenes Dictate the Vulnerability of NB to Ferroptosis

Amplified MYCN is found in 20–25% of cases of NB, and MYCN-amplified NB accounts for a large percentage of pediatric cancer-related deaths. A recent study revealed that amplified MYCN enhances iron influx by increasing the expression of transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) and lowering the expression of ferroportin, facilitating system/GSH pathway activation by upregulating SLC3A2 and SLC7A11 [70]. This study provides novel insights into how MYCN alters the transcriptome of NB to improve growth and survival. These changes increase the vulnerability of NB to ferroptosis inducers and highlight a potential strategy to treat MYCN-amplified NB by repurposing auranofin. MYCN-amplified NB cells are sensitive to GPX4-targeting ferroptosis inducers through the upregulation of TfR1 expression. TfR1 overexpression selectively increases sensitivity to GPX4 inhibition and ferroptosis. TFRC upregulation confers sensitivity to ferroptosis in NB cells with MYCN amplification, suggesting that GPX4-targeting ferroptosis inducers or TFRC agonists may constitute a new strategy for treating NB harboring MYCN amplification [71]. These observations were corroborated by other studies, which reported that MYCN mediates cysteine adduction and sensitizes NB cells to ferroptosis [72]. Depletion of cysteine promotes MYCN, which induces and sensitizes cells to ferroptosis. The uptake and transsulfuration pathways meet the high cysteine demand in MYCN-amplified childhood NB [72]. When cysteine uptake is limited, protein synthesis mediated by cysteine is maintained, but the loss of GSH triggers ferroptosis, resulting in spontaneous tumor regression in low-risk NB. Pharmacologically inhibiting both cystine uptake and transsulfuration combined with inactivating GPX4 depletes intracellular cysteine and GSH availability and causes tumor remission by triggering ferroptosis in an orthotopic MYCN-amplified NB model. These results suggest that combining multiple ferroptotic targets is a promising therapeutic strategy for aggressive MYCN-amplified NB [72]. Further study revealed that MYCN activates the transsulfuration pathway in NB [73]. Cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) and methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP) were increased in MYCN-amplified NB cell lines and tumors. CBS is the rate-limiting enzyme in transsulfuration, and MTAP is an enzyme that helps salvage methionine following polyamine metabolism. MYCN orchestrates both cystine uptake and activation of the transsulfuration pathway to confer ferroptosis vulnerability in MYCN-amplified NB [73]. A recent study revealed that the selenoprotein P receptor LRP8 functions as a key determinant through the inhibition of ferroptosis in MYCN-amplified NB [74]. Loss of LRP8 triggers ferroptosis resulting from an insufficient supply of selenocysteine, which is required for the translation of the antiferroptotic selenoprotein GPX4. This study suggested that LRP8 dictates the vulnerability of MYCN-amplified NB to ferroptosis [74]. Taken together, these results suggest that the oncogene MYCN influences the vulnerability of NB to ferroptosis.

Ferroptosis Dictates the Chemosensitivity of Neuroblastoma

A recent study revealed that the E3 ligase tripartite motif (TRIM) 59 protein promotes chemoresistance by suppressing ferroptosis in NB [75]. Silencing TRIM59 enhances the inhibitory effect of doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX) on the proliferation of neuroblastoma cells. TRIM59 expression was positively linked to cell proliferation in response to DOX. TRIM59 knockdown or overexpression promotes or inhibits ferroptosis, respectively, in neuroblastoma cells [75]. Moreover, TRIM59 inhibits ferroptosis by directly interacting with p53, promoting its ubiquitination and degradation in DOX-exposed neuroblastoma cells. Silencing TRIM59 increases neuroblastoma cell sensitivity to DOX by inducing ferroptosis. The ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) reverses TRIM59 knockdown-induced ferroptosis in neuroblastoma, whereas silencing TRIM59 facilitates the therapeutic efficacy of DOX in xenografted mice [75]. Together, the results of this study suggest that TRIM59 functions as an oncogene to induce chemoresistance to DOX in neuroblastoma through the suppression of ferroptosis through p53 ubiquitination and degradation [75].

Role of Cuproptosis in the Pathogenesis of Neuroblastoma

The role of cuproptosis in the immune landscape and prognosis of NB was first elucidated in 2022 [76]. The authors revealed that the cuproptosis-related gene signature can function as a valuable prognostic biomarker and allows for precise characterization of the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) in patients with NB. Based on publicly available mRNA expression profile data, the authors initially characterized the specific expression profiles of cuproptosis-related genes (CRGs) in NB samples. The authors classified patients with NB according to the CRGs in the GEO cohort and identified two cuproptosis-related subtypes that were associated with prognosis and the immunophenotype. Then, they constructed a cuproptosis-related prognostic signature, which was validated by LASSO regression. This model can accurately predict patient prognosis, immunotherapy response, and immune infiltration. Silencing the cuproptosis-related gene pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 alpha subunit (PDHA1) significantly inhibited proliferation, migration, and invasion but promoted cell cycle arrest at the S phase and apoptosis in NB cells [76].

A recent study revealed that novel CRG signatures can predict overall survival in pediatric patients with neuroblastoma [77]. Univariate Cox regression analysis revealed that 31 CRGs were associated with overall survival. Patients with NB could be classified into two CRG score groups according to a prognostic model comprising 9 CRGs that was established with LASSO regression analysis [77]. Multivariate analysis suggested that the CRG score was correlated with age, INSS stage, and MYCN status and that COG risk was an independent prognostic indicator. Stratification analysis still revealed a high predictive ability for survival prediction. The higher CRG score group was associated with immune cell infiltration, lower immune scores, and decreased expression of immune checkpoints. The CRG score can predict the drug sensitivity of patients with NB to chemotherapy [77]. These observations were corroborated by other studies, which reported that the established cuproptosis score and prediction model could effectively distinguish between individuals in low- and high-risk groups with high predictive value [78]. In particular, the novel CRG signature PDHA1 plays crucial roles in tumor progression, TIME features, and the long-term prognosis of patients with NB [78]. Taken together, the CRG signature may be used as a prognostic predictor in patients with NB, facilitating the development of effective anticancer therapies for NB.

Therapeutic Strategies for Neuroblastoma That Target Regulated Cell Death

Therapeutic Strategies for Neuroblastoma That Target Ferroptosis

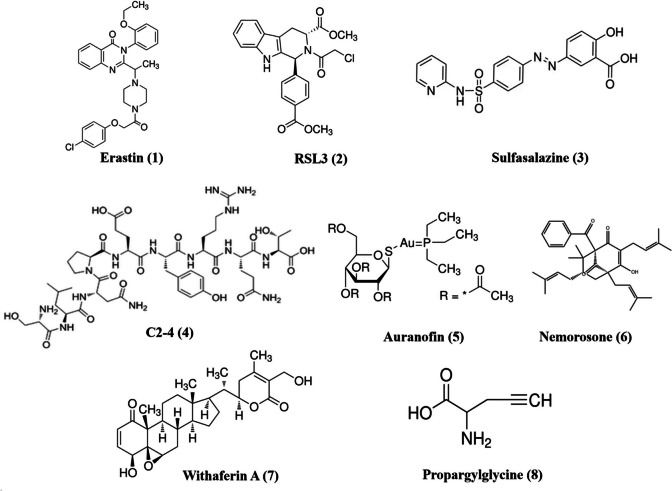

Emerging evidence has shown that the induction of ferroptosis is a novel therapy for NB. Emerging ferroptosis-inducing bioactive compounds (Fig. 3) can kill cancer cells in NB. Table 1 lists some compounds that target ferroptosis to kill NB cells.

Fig. 3.

Chemical structures of small molecules that target ferroptosis to treat neuroblastoma

Table 1.

Emerging compounds that target ferroptosis to inhibit neuroblastoma

| Compounds | Experimental model | Targets | Effects | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erastin (1) | CLP/C57BL/6 J male mice | System xc− | Kills mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) neuroblastoma (NB) | [66] |

| RSL3 (2) | LPS/HT22 cells | System xc− | Kills mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) neuroblastoma (NB) | [66] |

| Erastin (1) or RSL3 (2) | Neuroblastoma N2A cells | System xc− | Erastin or RSL3 induces ferroptosis in RAS-proficient N2A cells through upregulating HO-1 and downregulating GPX4 | [82] |

| Sulfasalazine (3) or C2-4 (4) | Etoposide-sensitive and resistant neuroblastoma CSCs | System xc− | Etoposide in combination with sulfasalazine or an inhibitor of PKCα (C2-4) sensitizes CSCs to etoposide by decreasing intracellular GSH levels, inducing a metabolic switch from OXPHOS to aerobic glycolysis, downregulating glutathione-peroxidase-4 activity and stimulating lipid peroxidation, thus leading to ferroptosis | [85] |

| PTC596 (5) | HTLA-230 and HTLA-ER cells treated with etoposide | System xc− | PTC596, alone or in combination with etoposide, significantly reduces GSH levels, increases peroxide production, stimulates lipid peroxidation, and induces ferroptosis | [86] |

| Sulfasalazine (3) | PDXs | System xc− | Sulfasalazine blocks growth and induces ferroptosis in MYCN-amplified, patient-derived xenograft models | [70] |

| Auranofin (6) | PDXs | System xc− | Auranofin blocks growth and induces ferroptosis in MYCN-amplified, patient-derived xenograft models | [70] |

| Nemorosone (7) | IMR-32 cells | System xc− | ↓GSH; ↓system xc− cystine/glutamate antiporter (SLC7A11); ↑intracellular labile Fe2+ pool; ↑heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX1) | [94] |

| Withaferin A (8) | Neuroblastoma N2A cells | GPX4 | Withaferin A induces ferroptosis through activating Nrf2 or inactivating GPX4. Withaferin A boosts the antitumor activity of etoposide or cisplatin in killing a heterogeneous panel of high-risk neuroblastoma cells and in suppressing the growth and relapse rates of neuroblastoma xenografts | [105] |

| Propargylglycine (9) | IMR5/75, GI-ME-N cells | Cystathionine gamma-lyase | Propargylglycine triggers ferroptosis through blocking cystathionine gamma-lyase, a key enzyme involved in cysteine synthesis in MYCN-driven neuroblastomas | [72] |

| IONP-GA/PAA (10) | IMR-32 cells | IONP-GA/PAA induces ferroptosis in IMR-32 cells, which is blocked by canonical ferroptosis inhibitors, including deferoxamine and ciclopirox olamine (iron chelators), and ferrostatin-1, the lipophilic radical trap | [106] |

4-HNE 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, BBB blood–brain barrier, BUN blood urea nitrogen, CK-MB creatine kinase MB, CLP cecal ligation and puncture, FPN ferroportin (SLC40A1), FSP1 ferroptosis suppressor protein 1, FTL ferritin light chain, FTH ferritin heavy chain, GSH glutathione, GSSG oxidized glutathione, HFD high-fat diet-fed, HO-1 heme oxygenase-1, IL-1β interleukin-1, IκBα inhibitor of kappa Bα, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, LPS lipopolysaccharide, MCTR1 maresin conjugates in tissue regeneration 1, MDA malondialdehyde, NF-κB nuclear factor kappa B, Nrf2 nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2, PTGS2 prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2, SCr serum creatinine, SLC7A11 solute carrier family 7 member 11, SOD superoxide dismutase, TECs renal tubular epithelial cells, TLR4 Toll-like receptor 4, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor-alpha, NCOA4 nuclear receptor coactivator 4

Ferroptosis Inducers Kill NB

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) are central to tumor stroma formation and promote the metastasis of NB to the bone marrow (BM). There is currently no effective method to eradicate these BMSCs affected by NB (NB-BMSCs). A recent study revealed that NB-BMSCs are more sensitive to ferroptosis than normal BMSCs are, as evidenced by how NB-BMSCs synthesize more iron‒sulfur clusters and heme while having lower levels of intracellular free iron and a downregulated xc−/GSH/GPX4 system. Erastin (1) is a class I ferroptosis inducer that functions as an inhibitor of system xc−, thereby preventing cysteine import and resulting in GSH depletion [79–81]. Accordingly, 1 and RAS-selective lethal 3 (RSL3, 2) could significantly kill NB-BMSCs but not normal BMSCs, providing a potential treatment for tumor-associated BMSCs in patients with NB. This observation has been corroborated by other studies, which showed that 1 and 2 induce ferroptosis in neuroblastoma N2A cells but not in normal neural cells [82]. Small molecules 1 and 2 induce ferroptosis in RAS-proficient neuroblastoma N2A cells. N2A cells are more vulnerable to 1 and 2 than are primary mouse cortical neural stem cells (NSCs) or neurons because of the lower expression of ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH), a ferroxidase that oxidizes redox-active Fe2+ to redox-inactive Fe3+, in N2A cells than in NSCs. Overexpression of FTH inhibits ferroptosis by upregulating GPX4 in N2A cells. Decreased expression of FTH was detected in neuroblastoma cell lines. These results suggest that 1 and 2 induce ferroptosis in neuroblastoma N2A cells due to inadequate FTH, highlighting new evidence that inducing ferroptosis is a promising therapeutic target for NB [82].

Ferroptosis Inducers Increase the Antitumor Activity of Chemotherapy

Sulfasalazine (3), an azo bridge-linked anti-inflammatory agent and a class I ferroptosis inducer that was originally synthesized from the antibiotic sulfapyridine, functions as an inhibitor of system xc−, thereby preventing cysteine import and resulting in GSH depletion [79–81, 83]. Compound 3 was found to inhibit the absorption of cystine, resulting in the attenuation of GSH and ultimately leading to cell death in certain types of cancer cells [84]. Compound 3 triggers ferroptosis by inhibiting the function of system xc− [30]. MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma accounts for a large percentage of pediatric cancer-related deaths. MYCN confers NB therapeutic vulnerability by rewiring the expression of key receptors, ultimately increasing iron influx by increasing the expression of iron import transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1). This increases NB cell reliance on the cystine/glutamate antiporter (system xc−) to detoxify ROS by increasing the transcription of this receptor [70]. Compound 3 and auranofin (6) can block cancer growth by inducing ferroptosis by targeting the system xc−/GSH pathway in MYCN-amplified, patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models. The ferroptosis inhibitors ferrostatin-1, N-acetyl-L-cysteine, and deferoxamine (DFO, an iron scavenger) largely reversed this antitumor activity. This study demonstrated how MYCN modulates intracellular iron levels and subsequent GSH pathway activity, revealing the antitumor activity of the FDA-approved auranofin in PDX models of MYCN-amplified NB [70].

C2-4 (4), an inhibitor of PKCα that indirectly targets xCT, increases the antitumor activity of chemotherapy in NB [85]. Compound 4 increases the sensitivity of neuroblastoma stem cells to etoposide by stimulating ferroptosis, as evidenced by decreased intracellular GSH levels, inducing a metabolic switch from OXPHOS to aerobic glycolysis, downregulating GPX4 activity, and facilitating LPO [85]. Compound 4 enhances the antitumor activity of etoposide by increasing the sensitivity of neuroblastoma stem cells to etoposide through the induction of ferroptosis, highlighting that PKCα inhibition-induced ferroptosis might be a useful strategy to overcome CSC chemoresistance [85].

PTC596 (5), an inhibitor of the oncoprotein BMI-1, has a strong cytotoxic effect on MDR NB cells. PTC596, alone or in combination with etoposide, significantly reduced GSH levels, increased peroxide production, stimulated lipid peroxidation, and induced ferroptosis. These findings indicate that PTC596 could be a promising approach to overcome chemoresistance through triggering ferroptosis by inhibiting BMI-1 in NB [86].

Small Molecules That Induce Ferroptosis

Nemorosone (7) is a bicyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinol derivative that was originally isolated from Clusia spp. and can be obtained through chemical synthesis via different synthetic strategies [87]. Compound 6 exerts antitumor effects on several types of malignancies, such as hepatocellular carcinoma, human colorectal cancer, leukemia, pancreatic cancer, and breast cancer [88–93]. Compound 7 functions as a ferroptosis-inducing compound (FIN) in NB; it induces ferroptosis by decreasing glutathione (GSH) levels, blocking SLC7A11 and increasing the intracellular labile Fe2+ pool via heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX1) induction [94]. Withaferin A (8), the most active phytocompound extracted from the renowned dietary supplement Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal, has remarkable antitumor efficacy in many cancers [95–103]. Previous studies have shown that 8 exerts antitumor activity by inhibiting activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) in NB [104]. Compound 8 triggers ferroptosis by activating Nrf2 through the targeting of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) to increase the level of intracellular labile Fe2+ upon excessive activation of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and inactivation of GPX4. This dual-edged mechanism enhances the efficacy of WA in combination with etoposide or cisplatin to kill a heterogeneous panel of high-risk BN cells, inhibiting the growth and relapse rates of NB xenografts [105].

Small Molecules Increase the Antitumor Activity of Ferroptosis Inducers

MYCN induces transsulfuration to prevent ferroptosis in NB [72]. Cystathionine gamma-lyase (CTH) and S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine hydrolase (AHCY) are two methyltransferases that feed into Hcy production and show synthetic lethality with high MYCN. CTH converts Cysta to cysteine, and AHCY synthesizes Hcy for transsulfuration. Supplementing either Hcy or Cysta prevents ferroptosis in all cystine-deprived adrenergic neuroblastoma cell lines tested with high or intermediate oncogenic MYC(N) expression but not in the less common mesenchymal NB cell lines. Propargylglycine (PPG), which pharmacologically inhibits CTH, enhances adrenergic cell lines with high MYCN levels to promote either imidazole ketone erastin (IKE)-induced or erastin-induced cell death. Silencing AHCY impaired colony formation in adrenergic high MYCN NB cells, as evidenced by decreased GSH levels and reduced GSH reduced-to-oxidized ratios. These data suggest that the transsulfuration pathway provides an internal cysteine source for GSH biosynthesis, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis in high MYCN adrenergic NB cells.

Therapeutic Strategies for Neuroblastoma That Target Cuproptosis

As a novel unique cell death modality, cuproptosis has sparked great interest in the field of cancer research, providing a novel mechanism to inhibit or kill tumor cells and overcome chemotherapeutic resistance [69, 107, 108]. Interestingly, emerging compounds, such as 2-deoxy-D-glucose, a glucose metabolism inhibitor, which increases the sensitivity of cancer cells to cuproptosis, have been shown to induce cuproptosis in preclinical models [108]. Octyl itaconate (4-OI) increases the sensitivity of cancer cells to cuproptosis by inhibiting aerobic glycolysis mediated by GAPDH [108]. 4-OI also enhances the antitumor activity of elesclomol-Cu in vivo [108]. Importantly, 4-OI promotes cuproptosis by inhibiting aerobic glycolysis, which targets GAPDH [108]. Anisomycin, a p38MAPK signaling pathway agonist, significantly inhibits the proliferation of ovarian cancer stem cells (OCSCs) by promoting cuproptosis and downregulating metallothionein, the PDH complex, the lipoid acid pathway, and FeS cluster protein utilization [109]. Plicamycin may be a cuproptosis inducer that inhibits the progression of HNSCC [110]. Sorafenib, a multityrosine kinase inhibitor, promotes cuproptosis by enhancing copper-mediated lipoylated protein aggregation, suppressing the degradation of FDX1, decreasing intracellular GSH synthesis, and inhibiting cystine import in primary liver cancer cells [111]. Erastin induces ferroptosis by inhibiting system xc−, leading to depleted GSH levels [52]. A recent study revealed that erastin and sorafenib could facilitate copper ionophore ES- and ES-Cu-induced cuproptosis by enhancing copper-mediated lipoylated protein aggregation, reducing intracellular GSH synthesis, and decreasing cystine import in HCC cells [111]. This study reveals crosstalk between ferroptosis and cuproptosis, where a combination of ferroptosis inducers and copper ionophores could be a novel therapeutic regimen for HCC. These findings strongly suggest that ferroptosis inducers work as cuproptosis inducers, suggesting that inducers or inhibitors of ferroptosis may also function as inducers or inhibitors of cuproptosis.

Recent research has shown that zinc pyrithione (ZnPT) significantly inhibits TNBC progression by inducing cuproptosis, as evidenced by ZnPT-induced disrupted copper homeostasis, which promotes the oligomerization of dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase, a landmark molecule of cuproptosis [112]. Taken together, these findings indicate that ZnPT can act as a model molecule for future drug discovery toward cuproptosis induction. To our knowledge, no previous studies have determined whether these compounds can induce cuproptosis in NB. Thus, cuproptosis inducers could enable the development of a cuproptosis-based therapy for NB in the future. However, whether cuproptosis can survive as a novel therapeutic regimen for NB remains to be determined.

Conclusions and Perspectives

This review presents recent progress in our understanding of the role of ferroptosis in NB. The oncogene MYCN dictates the vulnerability of NB to ferroptosis. Emerging evidence has confirmed that inducing ferroptosis is generally identified as an effective approach to induce cell death in NB. Ferroptosis inducers can kill NB cells or increase the antitumor activity of chemotherapy. Small molecules induce ferroptosis or increase the antitumor activity of ferroptosis inducers in NB. However, research on the role of ferroptosis is still in its infancy and represents an emerging field. Inevitable challenges remain before its practical application. First, little is known about the role of ferroptosis in NB, along with other cancers such as melanoma [113]. Second, much is still unknown about the role of ferroptosis in overcoming drug resistance to various chemotherapy regimens. Third, although some small-molecule compounds can induce ferroptosis or increase the antitumor activity of chemotherapy, more work is needed to screen and discover novel compounds that induce ferroptosis. Several small molecules can kill cancer cells by inducing ferroptosis. Thus, these drugs may be repurposed for the treatment of NB. Therefore, future exploration of the roles of ferroptosis in NB will promote the discovery of novel therapeutic strategies for NB. Fourth, there remains an urgent unmet need to develop predictive and personal biomarkers for labeling if ferroptosis can be used to treat specific tumors [71, 114, 115]. Fifth, emerging evidence has shown that the Nrf2‒NQO1 pathway regulates ferroptosis-related cell death in brain tumors [116]. However, the role of this pathway in NB is largely unknown and warrants further investigation. Cuproptosis in cancer and NB is still an emerging field and is in its infancy. First, the role of cuproptosis in NB is not yet well understood. Second, the regulatory mechanism underlying cuproptosis in NB needs to be elucidated. Third, the induction of cuproptosis may overcome resistance to conventional chemotherapy in some types of cancer; however, it is not known whether the induction of cuproptosis could overcome drug resistance to chemotherapy in NB. Taken together, ferroptosis and cuproptosis have been identified as novel types of RCD, and the induction of ferroptosis and cuproptosis can kill cancer cells. Thus, inducing ferroptosis and cuproptosis may be a novel potential therapeutic regimen for treating NB.

Author Contributions

YL and LH: writing—original draft preparation; YL and LH: writing—review; HW and JSF editing and visualization; YL and LH: funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2022-MS-209), the Liaoning Provincial Department of Education Scientific Research Project (QNZR2020012), the Henan Pediatric Disease Clinical Medical Research Center Foundation (YJZX202207), the CAAE Epilepsy Research Fund (CX-B-2021–02), and 2023 to support China Medical University high-quality development fund (2023JH2/20200119).

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ying Liu, Email: 20092406@cmu.edu.cn.

Liang Huo, Email: huol@sj-hospital.org.

References

- 1.Maris JM, Hogarty MD, Bagatell R, Cohn SL (2007) Neuroblastoma Lancet 369(9579):2106–2120. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60983-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pastor ER, Mousa SA (2019) Current management of neuroblastoma and future direction. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 138:38–43. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qiu B, Matthay KK (2022) Advancing therapy for neuroblastoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 19(8):515–533. 10.1038/s41571-022-00643-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kholodenko IV, Kalinovsky DV, Doronin II, Deyev SM, Kholodenko RV (2018) Neuroblastoma origin and therapeutic targets for immunotherapy. J Immunol Res 2018:7394268. 10.1155/2018/7394268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pai Panandiker AS, Beltran C, Billups CA, McGregor LM, Furman WL, Davidoff AM (2013) Intensity modulated radiation therapy provides excellent local control in high-risk abdominal neuroblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60(5):761–765. 10.1002/pbc.24350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthay KK, Maris JM, Schleiermacher G, Nakagawara A, Mackall CL, Diller L, Weiss WA (2016) Neuroblastoma Nat Rev Dis Primers 2:16078. 10.1038/nrdp.2016.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park JR, Eggert A, Caron H (2010) Neuroblastoma: biology, prognosis, and treatment. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 24(1):65–86. 10.1016/j.hoc.2009.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwab M, Alitalo K, Klempnauer KH, Varmus HE, Bishop JM, Gilbert F, Brodeur G, Goldstein M, Trent J (1983) Amplified DNA with limited homology to myc cellular oncogene is shared by human neuroblastoma cell lines and a neuroblastoma tumour. Nature 305(5931):245–248. 10.1038/305245a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mossé YP, Laudenslager M, Longo L, Cole KA, Wood A, Attiyeh EF, Laquaglia MJ, Sennett R, Lynch JE, Perri P, Laureys G, Speleman F, Kim C, Hou C, Hakonarson H, Torkamani A, Schork NJ, Brodeur GM, Tonini GP, Rappaport E, Devoto M, Maris JM (2008) Identification of ALK as a major familial neuroblastoma predisposition gene. Nature 455(7215):930–935. 10.1038/nature07261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diskin SJ, Capasso M, Schnepp RW, Cole KA, Attiyeh EF, Hou C, Diamond M, Carpenter EL, Winter C, Lee H, Jagannathan J, Latorre V, Iolascon A, Hakonarson H, Devoto M, Maris JM (2012) Common variation at 6q16 within HACE1 and LIN28B influences susceptibility to neuroblastoma. Nat Genet 44(10):1126–1130. 10.1038/ng.2387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Limpt V, Schramm A, van Lakeman A, Sluis P, Chan A, van Noesel M, Baas F, Caron H, Eggert A, Versteeg R (2004) The Phox2B homeobox gene is mutated in sporadic neuroblastomas. Oncogene 23(57):9280–9288. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Mariano M, Gallesio R, Chierici M, Furlanello C, Conte M, Garaventa A, Croce M, Ferrini S, Tonini GP, Longo L (2015) Identification of GALNT14 as a novel neuroblastoma predisposition gene. Oncotarget 6(28):26335–26346. 10.18632/oncotarget.4501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brodeur GM (1990) Neuroblastoma: clinical significance of genetic abnormalities. Cancer Surv 9(4):673–688 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang LL, Teshiba R, Ikegaki N, Tang XX, Naranjo A, London WB, Hogarty MD, Gastier-Foster JM, Look AT, Park JR, Maris JM, Cohn SL, Seeger RC, Asgharzadeh S, Shimada H (2015) Augmented expression of MYC and/or MYCN protein defines highly aggressive MYC-driven neuroblastoma: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Br J Cancer 113(1):57–63. 10.1038/bjc.2015.188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogawa S, Takita J, Sanada M, Hayashi Y (2011) Oncogenic mutations of ALK in neuroblastoma. Cancer Sci 102(2):302–308. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01825.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maris JM, Kyemba SM, Rebbeck TR, White PS, Sulman EP, Jensen SJ, Allen C, Biegel JA, Yanofsky RA, Feldman GL, Brodeur GM (1996) Familial predisposition to neuroblastoma does not map to chromosome band 1p36. Cancer Res 56(15):3421–3425 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ackermann S, Cartolano M, Hero B, Welte A, Kahlert Y, Roderwieser A, Bartenhagen C, Walter E, Gecht J, Kerschke L, Volland R, Menon R, Heuckmann JM, Gartlgruber M, Hartlieb S, Henrich KO, Okonechnikov K, Altmüller J, Nürnberg P, Lefever S, de Wilde B, Sand F, Ikram F, Rosswog C, Fischer J, Theissen J, Hertwig F, Singhi AD, Simon T, Vogel W, Perner S, Krug B, Schmidt M, Rahmann S, Achter V, Lang U, Vokuhl C, Ortmann M, Büttner R, Eggert A, Speleman F, O’Sullivan RJ, Thomas RK, Berthold F, Vandesompele J, Schramm A, Westermann F, Schulte JH, Peifer M, Fischer M (2018) A mechanistic classification of clinical phenotypes in neuroblastoma. Science 362(6419):1165–1170. 10.1126/science.aat6768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herd F, Basta NO, McNally R, Tweddle DA (2019) A systematic review of re-induction chemotherapy for children with relapsed high-risk neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer 111:50–58. 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.12.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinto NR, Applebaum MA, Volchenboum SL, Matthay KK, London WB, Ambros PF, Nakagawara A, Berthold F, Schleiermacher G, Park JR, Valteau-Couanet D, Pearson AD, Cohn SL (2015) Advances in risk classification and treatment strategies for neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol 33(27):3008–3017. 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coughlan D, Gianferante M, Lynch CF, Stevens JL, Harlan LC (2017) Treatment and survival of childhood neuroblastoma: evidence from a population-based study in the United States. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 34(5):320–330. 10.1080/08880018.2017.1373315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith V, Foster J (2018) High-risk neuroblastoma treatment review Children (Basel) 5(9):114. 10.3390/children5090114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maris JM (2010) Recent advances in neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med 362(23):2202–2211. 10.1056/NEJMra0804577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berlanga P, Cañete A, Castel V (2017) Advances in emerging drugs for the treatment of neuroblastoma. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 22(1):63–75. 10.1080/14728214.2017.1294159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Twist CJ, Schmidt ML, Naranjo A, London WB, Tenney SC, Marachelian A, Shimada H, Collins MH, Esiashvili N, Adkins ES, Mattei P, Handler M, Katzenstein H, Attiyeh E, Hogarty MD, Gastier-Foster J, Wagner E, Matthay KK, Park JR, Maris JM, Cohn SL (2019) Maintaining outstanding outcomes using response- and biology-based therapy for intermediate-risk neuroblastoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group study ANBL0531. J Clin Oncol 37(34):3243–3255. 10.1200/JCO.19.00919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zafar A, Wang W, Liu G, Wang X, Xian W, McKeon F, Foster J, Zhou J, Zhang R (2021) Molecular targeting therapies for neuroblastoma: progress and challenges. Med Res Rev 41(2):961–1021. 10.1002/med.21750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon T, Längler A, Harnischmacher U, Frühwald MC, Jorch N, Claviez A, Berthold F, Hero B (2007) Topotecan, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide (TCE) in the treatment of high-risk neuroblastoma. Results of a phase-II trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 133(9):653–661. 10.1007/s00432-007-0216-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park JR, Scott JR, Stewart CF, London WB, Naranjo A, Santana VM, Shaw PJ, Cohn SL, Matthay KK (2011) Pilot induction regimen incorporating pharmacokinetically guided topotecan for treatment of newly diagnosed high-risk neuroblastoma: a Children’s Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 29(33):4351–4357. 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.3293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanz AB, Sanchez-Niño MD, Ramos AM, Ortiz A (2023) Regulated cell death pathways in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 19(5):281–299. 10.1038/s41581-023-00694-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mishra AP, Salehi B, Sharifi-Rad M, Pezzani R, Kobarfard F, Sharifi-Rad J, Nigam M (2018) Programmed cell death, from a cancer perspective: an overview. Mol Diagn Ther 22(3):281–295. 10.1007/s40291-018-0329-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS, Morrison B 3rd, Stockwell BR (2012) Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149(5):1060–1072. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsvetkov P, Coy S, Petrova B, Dreishpoon M, Verma A, Abdusamad M, Rossen J, Joesch-Cohen L, Humeidi R, Spangler RD, Eaton JK, Frenkel E, Kocak M, Corsello SM, Lutsenko S, Kanarek N, Santagata S, Golub TR (2022) Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science 375(6586):1254–1261. 10.1126/science.abf0529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wan S, Zhang G, Liu R, Abbas MN, Cui H (2023) Pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and autophagy cross-talk in glioblastoma opens up new avenues for glioblastoma treatment. Cell Commun Signal 21(1):115. 10.1186/s12964-023-01108-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang S, Gu S (2020) Targeting autophagy in neuroblastoma. World J Pediatr Surg 3(3):e000121. 10.1136/wjps-2020-000121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang H, Zhou X, Li C, Yan S, Feng C, He J, Li Z, Tu C (2022) The emerging role of pyroptosis in pediatric cancers: from mechanism to therapy. J Hematol Oncol 15(1):140. 10.1186/s13045-022-01365-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao Y, Ji P, Chen H, Ge J, Xu Y, Wang P, Xu L, Yan Z (2023) Ferroptosis-based drug delivery system as a new therapeutic opportunity for brain tumors. Front Oncol 13:1084289. 10.3389/fonc.2023.1084289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Q, Ren L, Ren N, Yang Y, Pan J, Zheng Y, Wang G (2023) Ferroptosis: a new promising target for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. Mol Cell Biochem. 10.1007/s11010-023-04893-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y, Liu J, Wu S, Xiao J, Zhang Z (2023) Ferroptosis: opening up potential targets for gastric cancer treatment. Mol Cell Biochem. 10.1007/s11010-023-04886-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lei G, Zhuang L, Gan B (2022) Targeting ferroptosis as a vulnerability in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 22(7):381–396. 10.1038/s41568-022-00459-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gu Y, Li Y, Wang J, Zhang L, Zhang J, Wang Y (2023) Targeting ferroptosis: paving new roads for drug design and discovery. Eur J Med Chem 247:115015. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.115015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Wu S, Li Q, Sun H, Wang H (2023) Pharmacological inhibition of ferroptosis as a therapeutic target for neurodegenerative diseases and strokes. Adv Sci (Weinh) :e2300325. 10.1002/advs.202300325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Wang Y, Wu X, Ren Z, Li Y, Zou W, Chen J, Wang H (2023) Overcoming cancer chemotherapy resistance by the induction of ferroptosis. Drug Resist Updat 66:100916. 10.1016/j.drup.2022.100916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun Y, Xia X, Basnet D, Zheng JC, Huang J, Liu J (2022) Mechanisms of ferroptosis and emerging links to the pathology of neurodegenerative diseases. Front Aging Neurosci 14:904152. 10.3389/fnagi.2022.904152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bersuker K, Hendricks JM, Li Z, Magtanong L, Ford B, Tang PH, Roberts MA, Tong B, Maimone TJ, Zoncu R, Bassik MC, Nomura DK, Dixon SJ, Olzmann JA (2019) The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit ferroptosis. Nature 575(7784):688–692. 10.1038/s41586-019-1705-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M, da Silva MC, Ingold I, Goya Grocin A, Xavier da Silva TN, Panzilius E, Scheel CH, Mourão A, Buday K, Sato M, Wanninger J, Vignane T, Mohana V, Rehberg M, Flatley A, Schepers A, Kurz A, White D, Sauer M, Sattler M, Tate EW, Schmitz W, Schulze A, O’Donnell V, Proneth B, Popowicz GM, Pratt DA, Angeli J, Conrad M (2019) FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature 575(7784):693–698. 10.1038/s41586-019-1707-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kraft V, Bezjian CT, Pfeiffer S, Ringelstetter L, Müller C, Zandkarimi F, Merl-Pham J, Bao X, Anastasov N, Kössl J, Brandner S, Daniels JD, Schmitt-Kopplin P, Hauck SM, Stockwell BR, Hadian K, Schick JA (2020) GTP cyclohydrolase 1/tetrahydrobiopterin counteract ferroptosis through lipid remodeling. ACS Cent Sci 6(1):41–53. 10.1021/acscentsci.9b01063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soula M, Weber RA, Zilka O, Alwaseem H, La K, Yen F, Molina H, Garcia-Bermudez J, Pratt DA, Birsoy K (2020) Metabolic determinants of cancer cell sensitivity to canonical ferroptosis inducers. Nat Chem Biol 16(12):1351–1360. 10.1038/s41589-020-0613-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mao C, Liu X, Zhang Y, Lei G, Yan Y, Lee H, Koppula P, Wu S, Zhuang L, Fang B, Poyurovsky MV, Olszewski K, Gan B (2021) DHODH-mediated ferroptosis defence is a targetable vulnerability in cancer. Nature 593(7860):586–590. 10.1038/s41586-021-03539-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liang D, Feng Y, Zandkarimi F, Wang H, Zhang Z, Kim J, Cai Y, Gu W, Stockwell BR, Jiang X (2023) Ferroptosis surveillance independent of GPX4 and differentially regulated by sex hormones. Cell. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G, Tang D (2021) Ferroptosis in infection, inflammation, and immunity. J Exp Med. 218(6). 10.1084/jem.20210518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Chen X, Li J, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Tang D (2021) Ferroptosis: machinery and regulation. Autophagy 17(9):2054–2081. 10.1080/15548627.2020.1810918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liang D, Minikes AM, Jiang X (2022) Ferroptosis at the intersection of lipid metabolism and cellular signaling. Mol Cell 82(12):2215–2227. 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hadian K, Stockwell BR (2020) SnapShot: ferroptosis. Cell 181(5):1188-1188.e1. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dixon SJ, Winter GE, Musavi LS, Lee ED, Snijder B, Rebsamen M, Superti-Furga G, Stockwell BR (2015) Human haploid cell genetics reveals roles for lipid metabolism genes in nonapoptotic cell death. ACS Chem Biol 10(7):1604–1609. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, Irmler M, Beckers J, Aichler M, Walch A, Prokisch H, Trümbach D, Mao G, Qu F, Bayir H, Füllekrug J, Scheel CH, Wurst W, Schick JA, Kagan VE, Angeli JP, Conrad M (2017) ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol 13(1):91–98. 10.1038/nchembio.2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F, Angeli JP, Doll S, Croix CS, Dar HH, Liu B, Tyurin VA, Ritov VB, Kapralov AA, Amoscato AA, Jiang J, Anthonymuthu T, Mohammadyani D, Yang Q, Proneth B, Klein-Seetharaman J, Watkins S, Bahar I, Greenberger J, Mallampalli RK, Stockwell BR, Tyurina YY, Conrad M, Bayır H (2017) Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol 13(1):81–90. 10.1038/nchembio.2238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zou Y, Li H, Graham ET, Deik AA, Eaton JK, Wang W, Sandoval-Gomez G, Clish CB, Doench JG, Schreiber SL (2020) Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase contributes to phospholipid peroxidation in ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol 16(3):302–309. 10.1038/s41589-020-0472-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang D, Kroemer G (2020) Ferroptosis. Curr Biol 30(21):R1292–R1297. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.09.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsang T, Davis CI, Brady DC (2021) Copper biology. Curr Biol 31(9):R421–R427. 10.1016/j.cub.2021.03.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen L, Min J, Wang F (2022) Copper homeostasis and cuproptosis in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther 7(1):378. 10.1038/s41392-022-01229-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xiong C, Ling H, Hao Q, Zhou X (2023) Cuproptosis: p53-regulated metabolic cell death. Cell Death Differ 30(4):876–884. 10.1038/s41418-023-01125-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ge EJ, Bush AI, Casini A, Cobine PA, Cross JR, DeNicola GM, Dou QP, Franz KJ, Gohil VM, Gupta S, Kaler SG, Lutsenko S, Mittal V, Petris MJ, Polishchuk R, Ralle M, Schilsky ML, Tonks NK, Vahdat LT, Van Aelst L, Xi D, Yuan P, Brady DC, Chang CJ (2022) Connecting copper and cancer: from transition metal signalling to metalloplasia. Nat Rev Cancer 22(2):102–113. 10.1038/s41568-021-00417-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsvetkov P, Detappe A, Cai K, Keys HR, Brune Z, Ying W, Thiru P, Reidy M, Kugener G, Rossen J, Kocak M, Kory N, Tsherniak A, Santagata S, Whitesell L, Ghobrial IM, Markley JL, Lindquist S, Golub TR (2019) Mitochondrial metabolism promotes adaptation to proteotoxic stress. Nat Chem Biol 15(7):681–689. 10.1038/s41589-019-0291-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beratis NG, Yee M, LaBadie GU, Hirschhorn K (1980) Effect of copper on Menkes’ and normal cultured skin fibroblasts. Dev Pharmacol Ther 1(5):305–317 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bégin ME, Ells G, Horrobin DF (1988) Polyunsaturated fatty acid-induced cytotoxicity against tumor cells and its relationship to lipid peroxidation. J Natl Cancer Inst 80(3):188–194. 10.1093/jnci/80.3.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin Q, Hou S, Dai Y, Jiang N, Lin Y (2020) Monascin exhibits neuroprotective effects in rotenone model of Parkinson’s disease via antioxidation and anti-neuroinflammation. Neuroreport 31(9):637–643. 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li X, Wang Q, Xu C, Zhang L, Zhou J, Lv J, Xu M, Jiang D (2023) Ferroptosis inducers kill mesenchymal stem cells affected by neuroblastoma. Cancers (Basel) 15(4):1301. 10.3390/cancers15041301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nagai M, Vo NH, Shin Ogawa L, Chimmanamada D, Inoue T, Chu J, Beaudette-Zlatanova BC, Lu R, Blackman RK, Barsoum J, Koya K, Wada Y (2012) The oncology drug elesclomol selectively transports copper to the mitochondria to induce oxidative stress in cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med 52(10):2142–2150. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gao W, Huang Z, Duan J, Nice EC, Lin J, Huang C (2021) Elesclomol induces copper-dependent ferroptosis in colorectal cancer cells via degradation of ATP7A. Mol Oncol 15(12):3527–3544. 10.1002/1878-0261.13079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Y, Chen Y, Zhang J, Yang Y, Fleishman JS, Wang Y, Wang J, Chen J, Li Y, Wang H (2023) Cuproptosis: a novel therapeutic target for overcoming cancer drug resistance. Drug Resist Updat 72:101018. 10.1016/j.drup.2023.101018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Floros KV, Cai J, Jacob S, Kurupi R, Fairchild CK, Shende M, Coon CM, Powell KM, Belvin BR, Hu B, Puchalapalli M, Ramamoorthy S, Swift K, Lewis JP, Dozmorov MG, Glod J, Koblinski JE, Boikos SA, Faber AC (2021) MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma is addicted to iron and vulnerable to inhibition of the system Xc-/glutathione axis. Cancer Res 81(7):1896–1908. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-1641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lu Y, Yang Q, Su Y, Ji Y, Li G, Yang X, Xu L, Lu Z, Dong J, Wu Y, Bei JX, Pan C, Gu X, Li B (2021) MYCN mediates TFRC-dependent ferroptosis and reveals vulnerabilities in neuroblastoma. Cell Death Dis 12(6):511. 10.1038/s41419-021-03790-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alborzinia H, Flórez AF, Kreth S, Brückner LM, Yildiz U, Gartlgruber M, Odoni DI, Poschet G, Garbowicz K, Shao C, Klein C, Meier J, Zeisberger P, Nadler-Holly M, Ziehm M, Paul F, Burhenne J, Bell E, Shaikhkarami M, Würth R, Stainczyk SA, Wecht EM, Kreth J, Büttner M, Ishaque N, Schlesner M, Nicke B, Stresemann C, Llamazares-Prada M, Reiling JH, Fischer M, Amit I, Selbach M, Herrmann C, Wölfl S, Henrich KO, Höfer T, Trumpp A, Westermann F (2022) MYCN mediates cysteine addiction and sensitizes neuroblastoma to ferroptosis. Nat Cancer 3(4):471–485. 10.1038/s43018-022-00355-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Floros KV, Chawla AT, Johnson-Berro MO, Khatri R, Stamatouli AM, Boikos SA, Dozmorov MG, Cowart LA, Faber AC (2022) MYCN upregulates the transsulfuration pathway to suppress the ferroptotic vulnerability in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. Cell Stress 6(2):21–29. 10.15698/cst2022.02.264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alborzinia H, Chen Z, Yildiz U, Freitas FP, Vogel F, Varga JP, Batani J, Bartenhagen C, Schmitz W, Büchel G, Michalke B, Zheng J, Meierjohann S, Girardi E, Espinet E, Flórez AF, Dos Santos AF, Aroua N, Cheytan T, Haenlin J, Schlicker L, Xavier da Silva TN, Przybylla A, Zeisberger P, Superti-Furga G, Eilers M, Conrad M, Fabiano M, Schweizer U, Fischer M, Schulze A, Trumpp A, Friedmann Angeli JP (2023) LRP8-mediated selenocysteine uptake is a targetable vulnerability in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. EMBO Mol Med 15(8):18014. 10.15252/emmm.202318014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu Y, Jiang N, Chen W, Zhang W, Shen X, Jia B, Chen G (2024) TRIM59-mediated ferroptosis enhances neuroblastoma development and chemosensitivity through p53 ubiquitination and degradation. Heliyon 10(4):e26014. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tian XM, Xiang B, Yu YH, Li Q, Zhang ZX, Zhanghuang C, Jin LM, Wang JK, Mi T, Chen ML, Liu F, Wei GH (2022) A novel cuproptosis-related subtypes and gene signature associates with immunophenotype and predicts prognosis accurately in neuroblastoma. Front Immunol 13:999849. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.999849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang H, Yang J, Bian H, Wang X (2022) A novel cuproptosis-related gene signature predicting overall survival in pediatric neuroblastoma patients. Front Pediatr 10:1049858. 10.3389/fped.2022.1049858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhou R, Huang D, Fu W, Shu F (2023) Comprehensive exploration of the involvement of cuproptosis in tumorigenesis and progression of neuroblastoma. BMC Genomics 24(1):715. 10.1186/s12864-023-09699-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Capelletti MM, Manceau H, PuyPeoc’h HK (2020) Ferroptosis in liver diseases: an overview. Int J Mol Sci 21(14):4908. 10.3390/ijms21144908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim KM, Cho SS, Ki SH (2020) Emerging roles of ferroptosis in liver pathophysiology. Arch Pharm Res 43(10):985–996. 10.1007/s12272-020-01273-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tang D, Kang R (2023) From oxytosis to ferroptosis: 10 years of research on oxidative cell death. Antioxid Redox Signal 39(1–3):162–165. 10.1089/ars.2023.0356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lu R, Jiang Y, Lai X, Liu S, Sun L, Zhou ZW (2021) A shortage of FTH induces ROS and sensitizes RAS-proficient neuroblastoma N2A cells to ferroptosis. Int J Mol Sci 22(16):8898. 10.3390/ijms22168898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gout PW, Buckley AR, Simms CR, Bruchovsky N (2001) Sulfasalazine, a potent suppressor of lymphoma growth by inhibition of the x(c)- cystine transporter: a new action for an old drug. Leukemia 15(10):1633–1640. 10.1038/sj.leu.2402238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wahl C, Liptay S, Adler G, Schmid RM (1998) Sulfasalazine: a potent and specific inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B. J Clin Invest 101(5):1163–1174. 10.1172/JCI992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Monteleone L, Speciale A, Valenti GE, Traverso N, Ravera S, Garbarino O, Leardi R, Farinini E, Roveri A, Ursini F, Cantoni C, Pronzato MA, Marinari UM, Marengo B, Domenicotti C (2021) PKCα inhibition as a strategy to sensitize neuroblastoma stem cells to etoposide by stimulating ferroptosis. Antioxidants (Basel) 10(5). 10.3390/antiox10050691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Valenti GE, Roveri A, Venerando R, Menichini P, Monti P, Tasso B, Traverso N, Domenicotti C, Marengo B (2023) PTC596-induced BMI-1 inhibition fights neuroblastoma multidrug resistance by inducing ferroptosis. Antioxidants (Basel) 13(1):3. 10.3390/antiox13010003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cuesta-Rubio O, Monzote L, Fernández-Acosta R, Pardo-Andreu GL, Rastrelli L (2023) A review of nemorosone: chemistry and biological properties. Phytochemistry 210:113674. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2023.113674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wolf RJ, Hilger RA, Hoheisel JD, Werner J, Holtrup F (2013) In vivo activity and pharmacokinetics of nemorosone on pancreatic cancer xenografts. PLoS ONE 8(9):e74555. 10.1371/journal.pone.0074555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Camargo MS, Oliveira MT, Santoni MM, Resende FA, Oliveira-Höhne AP, Espanha LG, Nogueira CH, Cuesta-Rubio O, Vilegas W, Varanda EA (2015) Effects of nemorosone, isolated from the plant Clusia rosea, on the cell cycle and gene expression in MCF-7 BUS breast cancer cell lines. Phytomedicine 22(1):153–157. 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Frión-Herrera Y, Gabbia D, Cuesta-Rubio O, De Martin S, Carrara M (2019) Nemorosone inhibits the proliferation and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Life Sci 235:116817. 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Frión-Herrera Y, Gabbia D, Díaz-García A, Cuesta-Rubio O, Carrara M (2019) Chemosensitizing activity of Cuban propolis and nemorosone in doxorubicin resistant human colon carcinoma cells. Fitoterapia 136:104173. 10.1016/j.fitote.2019.104173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Frión-Herrera Y, Gabbia D, Scaffidi M, Zagni L, Cuesta-Rubio O, De Martin S, Carrara M (2020) Cuban brown propolis interferes in the crosstalk between colorectal cancer cells and M2 macrophages. Nutrients 12(7):2040. 10.3390/nu12072040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Frión-Herrera Y, Gabbia D, Scaffidi M, Zagni L, Cuesta-Rubio O, De Martin S, Carrara M (2020) The Cuban propolis component nemorosone inhibits Proliferation and metastatic properties of human colorectal cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci 21(5):1827. 10.3390/ijms21051827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fernández-Acosta R, Hassannia B, Caroen J, Wiernicki B, Alvarez-Alminaque D, Verstraeten B, Van der Eycken J, Vandenabeele P, Vanden Berghe T, Pardo-Andreu GL (2023) Molecular mechanisms of nemorosone-induced ferroptosis in cancer cells. Cells 12(5):735. 10.3390/cells12050735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vyas AR, Singh SV (2014) Molecular targets and mechanisms of cancer prevention and treatment by withaferin a, a naturally occurring steroidal lactone. AAPS J 16(1):1–10. 10.1208/s12248-013-9531-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McKenna MK, Gachuki BW, Alhakeem SS, Oben KN, Rangnekar VM, Gupta RC, Bondada S (2015) Anti-cancer activity of withaferin A in B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Biol Ther 16(7):1088–1098. 10.1080/15384047.2015.1046651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mahadevappa R, Kwok HF (2017) Phytochemicals - a novel and prominent source of anti-cancer drugs against colorectal cancer. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen 20(5):376–394. 10.2174/1386207320666170112141833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yin X, Yang G, Ma D, Su Z (2020) Inhibition of cancer cell growth in cisplatin-resistant human oral cancer cells by withaferin-A is mediated via both apoptosis and autophagic cell death, endogenous ROS production, G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and by targeting MAPK/RAS/RAF signalling pathway. J BUON 25(1):332–337 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Meghalatha TS, Muninathan N (2022) Antitumor activity of withaferin-A and propolis in benz (a) pyrene-induced breast cancer. Bioinformation 18(9):841–844. 10.6026/97320630018841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Abeesh P, Guruvayoorappan C (2023) The therapeutic effects of withaferin A against cancer: overview and updates. Curr Mol Med. 10.2174/1566524023666230418094708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Khalil R, Green RJ, Sivakumar K, Varandani P, Bharadwaj S, Mohapatra SS, Mohapatra S (2023) Withaferin A increases the effectiveness of immune checkpoint blocker for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Cancers (Basel) 15(12):3089. 10.3390/cancers15123089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kumar V, Dhanjal JK, Sari AN, Khurana M, Kaul SC, Wadhwa R, Sundar D (2023) Effect of withaferin-A, withanone, and caffeic acid phenethyl ester on DNA methyltransferases: potential in epigenetic cancer therapy. Curr Top Med Chem. 10.2174/1568026623666230726105017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Xing Z, Su A, Mi L, Zhang Y, He T, Qiu Y, Wei T, Li Z, Zhu J, Wu W (2023) Withaferin A: a dietary supplement with promising potential as an anti-tumor therapeutic for cancer treatment - pharmacology and mechanisms. Drug Des Devel Ther 17:2909–2929. 10.2147/DDDT.S422512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yco LP, Mocz G, Opoku-Ansah J, Bachmann AS (2014) Withaferin A inhibits STAT3 and induces tumor cell death in neuroblastoma and multiple myeloma. Biochem Insights 7:1–13. 10.4137/BCI.S18863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hassannia B, Wiernicki B, Ingold I, Qu F, Van Herck S, Tyurina YY, Bayır H, Abhari BA, Angeli J, Choi SM, Meul E, Heyninck K, Declerck K, Chirumamilla CS, Lahtela-Kakkonen M, Van Camp G, Krysko DV, Ekert PG, Fulda S, De Geest BG, Conrad M, Kagan VE, Vanden Berghe W, Vandenabeele P, Vanden Berghe T (2018) Nano-targeted induction of dual ferroptotic mechanisms eradicates high-risk neuroblastoma. J Clin Invest 128(8):3341–3355. 10.1172/JCI99032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fernández-Acosta R, Iriarte-Mesa C, Alvarez-Alminaque D, Hassannia B, Wiernicki B, Díaz-García AM, Vandenabeele P, Vanden Berghe T, Pardo Andreu GL (2022) Novel iron oxide nanoparticles induce ferroptosis in a panel of cancer cell lines. Molecules 27(13):3970. 10.3390/molecules27133970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wang M, Zheng L, Ma S, Lin R, Li J, Yang S (2023) Cuproptosis: emerging biomarkers and potential therapeutics in cancers. Front Oncol 13:1288504. 10.3389/fonc.2023.1288504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yang W, Wang Y, Huang Y, Yu J, Wang T, Li C, Yang L, Zhang P, Shi L, Yin Y, Tao K, Li R (2023) 4-Octyl itaconate inhibits aerobic glycolysis by targeting GAPDH to promote cuproptosis in colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother 159:114301. 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nie X, Chen H, Xiong Y, Chen J, Liu T (2022) Anisomycin has a potential toxicity of promoting cuproptosis in human ovarian cancer stem cells by attenuating YY1/lipoic acid pathway activation. J Cancer 13(14):3503–3514. 10.7150/jca.77445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fan K, Dong Y, Li T, Li Y (2022) Cuproptosis-associated CDKN2A is targeted by plicamycin to regulate the microenvironment in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front Genet 13:1036408. 10.3389/fgene.2022.1036408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wang W, Lu K, Jiang X, Wei Q, Zhu L, Wang X, Jin H, Feng L (2023) Ferroptosis inducers enhanced cuproptosis induced by copper ionophores in primary liver cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 42(1):142. 10.1186/s13046-023-02720-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yang X, Deng L, Diao X, Yang S, Zou L, Yang Q, Li J, Nie J, Zhao L, Jiao B (2023) Targeting cuproptosis by zinc pyrithione in triple-negative breast cancer. IScience 26(11):108218. 10.1016/j.isci.2023.108218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ta N, Jiang X, Zhang Y, Wang H (2023) Ferroptosis as a promising therapeutic strategy for melanoma. Front Pharmacol 14:1252567. 10.3389/fphar.2023.1252567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Vinik Y, Maimon A, Dubey V, Raj H, Abramovitch I, Malitsky S, Itkin M, Ma’ayan A, Westermann F, Gottlieb E, Ruppin E, Lev S (2024) Programming a ferroptosis-to-apoptosis transition landscape revealed ferroptosis biomarkers and repressors for cancer therapy. Adv Sci (Weinh) :e2307263. 10.1002/advs.202307263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 115.Qiu L, Zhou R, Luo Z, Wu J, Jiang H (2022) CDC27-ODC1 axis promotes metastasis, accelerates ferroptosis and predicts poor prognosis in neuroblastoma. Front Oncol 12:774458. 10.3389/fonc.2022.774458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yuhan L, Khaleghi Ghadiri M, Gorji A (2024) Impact of NQO1 dysregulation in CNS disorders. J Transl Med 22(1):4. 10.1186/s12967-023-04802-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.