Abstract

Background

Nephrolithiasis, a common urinary system disorder, exhibits high morbidity and recurrence rates, correlating with renal dysfunction and the increased risk of chronic kidney disease. Nonetheless, the precise role of disrupted cellular metabolism in renal injury induced by calcium oxalate (CaOx) crystal deposition is unclear. The purpose of this study is to investigate the involvement of the ubiquitin-like protein containing PHD and RING finger structural domain 1 (UHRF1) in CaOx-induced renal fibrosis and its impacts on cellular lipid metabolism.

Methods

Various approaches, including snRNA-seq, transcriptome RNA-seq, immunohistochemistry, and western blot analyses, were employed to assess UHRF1 expression in kidneys of nephrolithiasis patients, hyperoxaluric mice, and CaOx-induced renal tubular epithelial cells. Subsequently, knockdown of UHRF1 in mice and cells corroborated its effect of UHRF1 on fibrosis, ectopic lipid deposition (ELD) and fatty acid oxidation (FAO). Rescue experiments using AICAR, ND-630 and Compound-C were performed in UHRF1-knockdown cells to explore the involvement of the AMPK pathway. Then we confirmed the bridging molecule and its regulatory pathway in vitro. Experimental results were finally confirmed using AICAR and chemically modified si-UHRF1 in vivo of hyperoxaluria mice model.

Results

Mechanistically, UHRF1 was found to hinder the activation of the AMPK/ACC1 pathway during CaOx-induced renal fibrosis, which was mitigated by employing AICAR, an AMPK agonist. As a nuclear protein, UHRF1 facilitates nuclear translocation of AMPK and act as a molecular link targeting the protein phosphatase PP2A to dephosphorylate AMPK and inhibit its activity.

Conclusion

This study revealed that UHRF1 promotes CaOx -induced renal fibrosis by enhancing lipid accumulation and suppressing FAO via inhibiting the AMPK pathway. These findings underscore the feasible therapeutic implications of targeting UHRF1 to prevent renal fibrosis due to stones.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10565-025-09991-9.

Keywords: UHRF1, AMPK, Renal fibrosis, Lipid synthesis, Fatty acid oxidation

Introduction

Nephrolithiasis is well-known urology condition globally, with CaOx accounting for approximately 70% of all kidney stone types, representing the most prevalent type. In Chinese adults, the prevalence of nephrolithiasis is 5.8% (Wang et al. 2021), with a 50% recurrence rate (Wang et al. 2017)and a lifetime prevalence of 15.5% (Zeng et al. 2017). Considering the financial, physical, and emotional burden on nephrolithiasis patients, serious attention must be focused on preventive strategies and treatment options to reduce both new and recurrent stone formation (Peerapen and Thongboonkerd 2023).The deposition of CaOx crystals in Randall's plaques triggers renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs) damage and extracellular matrix accumulation (Alexander et al. 2022).Prolonged recurrent renal stone episodes lead to urethral obstruction and hydronephrosis. Consequently, long-term renal stones often contribute to renal fibrosis, which accelerates the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Uribarri 2020).

UHRF1 (also known as NP95 or ICBP90) is widely recognized for maintain DNA methylation and regulating cell proliferation in multiple species (Mancini et al. 2021; Jenkins et al. 2005). The classical role of UHRF1 involves binding to H3K9me2/3 or hemimethylated CpG sites, thereby recruiting DNMT1 to preserve DNA methylation and facilitating crosstalk between H3K9 methylation and DNA methylation (Liu et al. 2013). Furthermore, UHRF1 is involved in the progression of interstitial lung fibrosis (Cheng et al. 2022, Liu et al. 2022a, b). Emerging evidence suggests a potential association between UHRF1 and cell metabolism and proliferation, independent of its methylation function (Hu et al. 2019; Xu et al. 2022).

AMPK is a crucial regulator of energy homeostasis, playing a pivotal role in various energy metabolic pathways, including glucose and lipid metabolism, as well as mitochondrial autophagy(Herzig and Shaw 2018; Li et al. 2021). Under kidney ischemia–reperfusion, decreased AMPK activity leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and notable accumulation of lipid droplets (LDs) and free fatty acids (FFAs) in the kidney(Ma et al. 2022). Activation of the AMPK/ACC pathway reduces renal lipid accumulation and slows the CKD progression, particularly in diabetic nephropathy-associated kidney injury (Kim et al. 2018). In AMPK knockout mice, adipose tissue exhibits reduced ATGL phosphorylation and activity, resulting in decreased basal lipolysis levels(Kim et al. 2016), emphasizing the significant regulatory role of AMPK in lipid metabolism.

Recent evidence suggests AMPK acts as a bridge facilitating UHRF1's regulation of metabolic processes. UHRF1 inhibits AMPK-mediated p-EZH2(T311) and p-H2(S36), thereby suppressing lipolysis and glycolysis(Hsu et al. 2022). Overexpressing of UHRF1 in mouse liver impairs AMPK activity, leading to elevated expression of gluconeogenesis-related genes (G6pc, Pepck), and lipid synthesis-related genes (Fasn, Srebp6c) (Xu et al. 2022). However, the role of UHRF1 in mediating abnormal lipid metabolism during tubule injuries and interstitial fibrosis caused by renal stones, and the underlying mechanism of UHRF1's interaction with AMPK in this process, remains unclear.

Our results demonstrate that UHRF1 expression is remarkably elevated in kidneys of nephrolithiasis patients contrasted to those of normal individuals. Moreover, increased UHRF1 levels correlate with upregulated lipid accumulation. Mechanistically, we found that UHRF1's involvement in CaOx-induced renal fibrosis by recruiting PP2A to dephosphorylate AMPK, leading to ectopic lipid deposition. These findings position UHRF1 as a promising therapeutic target for renal calculus patients.

Material and methods

Human samples

Human kidney tissues, including non-functioning kidneys from patients with CaOx calculi (Nephrolithiasis, n = 8), and adjacent non-tumor kidney tissues from patients who underwent radical nephrectomy (NC, n = 8) were obtained from the Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, China. The collection of clinical specimen was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University (approval number: WDRY2021-KS047).

Animals

Male C57BL/6 J mice, aged 6–8 weeks, weighing 20–28 g were selected for this experiment. The Experimental Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Wuhan University People's Hospital (approval number: WDRM20200604) permitted all animal procedures. Animals were housed in barrier environments where animal welfare could be guaranteed. Serotype 9 AAV vectors (AAV9) carrying Sh-UHRF1 or Sh-NC (Hanheng Biotechnology) were injected into five different sites of the renal cortex according to the manufacture’s instruction. Three weeks after injection, the efficiency of UHRF1 knockdown was verified by western blot.

Four groups of mice (n = 9 in each group) were used to explore the effect of UHRF1 on CaOx crystal-induced kidney fibrosis: control, hyperoxaluria, hyperoxaluria + vector, and hyperoxaluria + Sh-UHRF1. Mice in the hyperoxaluria groups were intraperitoneally injected with glyoxylate (120 mg/kg/day; G10601; Sigma-Aldrich) for 12 consecutive days (Ye et al. 2022; Xia et al. 2021). Additionally, another four groups of mice (n = 9 in each group) to examine the therapeutic effects of AICAR (AMPK agonist) and chemically modified si-UHRF1 on kidney stones: control, Gly, Gly + Si-UHRF1, and Gly + Si-UHRF1 + AICAR. On day 1 before glyoxylate injection and on days 1, 3, 6, 9, and 11 after glyoxylate treatment, AICAR (0.05 g/mL) was administered intraperitoneally, and si-UHRF1 (5 nmol/20 g) was injected intraperitoneally on days 0, 4, 8 and 11.

Target sequences of sh-UHRF1 and si-UHRF1 were listed in Table S1. Additionally, the siRNAs were modified with methoxy and cholesterol and obtained from GenePharma, Shanghai, China.

Cell culture

HK-2 cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (Vivacell, C2910-0500) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin solution. Cells were placed at 37℃ and 5% CO2 environment. Different concentrations of calcium oxalate stimulated HK-2 cells for 24 h. 150 μg/mL was determined to be the optimal concentration for affecting UHRF1 expression. Si-NC (control), Si-UHRF1, and Si-PPP2CA (from GenePharma Shanghai, China) were transfected into cells by Lipo6000 (C0526, Beyotime).

The sequences of siRNAs in cell experiments were listed in Table S2.

To study the inhibition effect of the AMPK pathway, cells were treated with AICAR (0.5 μM, 24 h), Compound C (5 μM, 18 h), or ND-630 (1 μM, 48 h) after modelling. All the reagents are from MCE (MedChemExpress; New Jersey, USA).

Transcriptome RNA sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

Kidneys from the glyoxylate group (Gly, n = 3) and the control group (NC, n = 3) were collected for transcriptome RNA sequencing. Each sample provided 3 μg total RNA by the TRIzol kit (Invitrogen). RNA sequencing assay and subsequent data analysis were performed by BGI Group (Shenzhen, China). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified based on the criteria of lg|FC|> 1 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. The results were analysed through heatmap, volcano plot, KEGG, and GO using DEseq2 of R Studio.

The Kidney Precision Medicine Project (KPMP; https://www.kpmp.org/) provided the single-nucleus RNA-Seq dataset. This dataset was utilized to compare UHRF1 expression levels in RTECs between patients with CKD and healthy individuals. The snRNA-seq dataset included 25 healthy reference and 37 CKD samples.

The gene expression dataset GSE73680(Taguchi et al. 2017) from the calculi study is downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). This dataset includes 62 samples of Randall's plaque tissues, encompassing 29 patients with kidney stones and 33 healthy individuals. The current study investigated correlations between UHRF1 and ECM protein expression levels.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using VeZol (R411-01, Vazyme). cDNA was obtained using a cDNA Synthesis Kit (R312-01, Vazyme). β-actin as an internal reference, and the relative mRNA expression was figured by the 2−ΔΔCt method, using the En Turbo™ SYBR Green PCR SuperMix kit (Yeasen, Shanghai, China).

The primers used in the assay were listed in Table S3.

Methylation specific PCR (MSP)

The Blood/Cell/Tissue Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (EP007, ELK Biotechnology, Wuhan, China) was utilized for genomic DNA extraction. Methylation status in the promoter region of AMPK was assayed using the Methylation-gold Kit (ZYMO, D5005S). Methylated and unmethylated AMPK gene-specific PCR primers were listed in Table S3. Results of agarose gel electrophoresis were captured using a UV imaging system.

Renal function assessment

Mice serum creatinine (SCr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels were measured as indicators of renal function, following the standard protocols provided by JianCheng (Nanjing, China).

Western blot

The steps of Western blot were referred to a previously published article from our group(Sun et al. 2024). The antibodies were listed in Table S4.

Renal histopathology and detection renal CaOx crystals

Prepare paraffin-embedded kidney tissue Sects (2 ~ 4 μm thick) were prepared and stained with hematoxylin–eosin (HE), Masson, Sirius-Red, and Von-Kossa after dewaxing and rehydrating slices. The severity of renal injury was evaluated using the Tubular Injury Score (Ye et al. 2022), which was ranked from 0 to 4 to assess injury severity based on the percentage of injury: 0 (No injury), 1 (25% of tubular injuries), 2 (25%−49% of tubular injuries), 3 (50%−75% of tubular injuries), and 4 (75% of tubular injuries).

The collagen areas by Sirius-Red and Masson staining were quantified using ImageJ software (1.8.0). CaOx-deposition was detected by Von-Kossa staining, and ImageJ software (1.8.0) was employed to measure the crystal deposition area.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

5 mm-thick mouse sections were dewaxed and rehydrated. The sections were then treated with 3% H2O2 for 10 min, followed by 10% citrate buffer to repair the antigen (P0081, Beyotime). Block slices with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min. The sections were then incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. Then wash with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Secondary antibody incubates with sections for 30 min. Subsequently, sections were washed, stained, redyed, dehydrated, and sealed and then observed under a microscope (BX51, Olympus). ImageJ (1.8.0) performed semi-quantitative analysis. The dilution and utilization of primary antibodies were listed in Table S4.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

HK-2 cells with a density of 70% cultured on a slide fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, and kidney sections were fixed for 24 h. Permeate them with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min, then seal with 5% BSA for 1 h. Subsequently, the samples were incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. Incubate with a fluorescent secondary antibody (4412, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the slices were blocked with an anti-fluorescence quencher (P0131, Beyotime Biotechnology). ImageJ (version 1.8.0) was utilized to analyze the images captured using a fluorescence microscope (BX51, Olympus). The primary antibodies and reagents and their dilutions were listed in Table S4.

Lipid staining

Lipid droplets (LDs) were stained using BODIPY493/503 solution (10 mM) for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Imaging was conducted using both a fluorescence microscope (BX51, Olympus) and a confocal microscope (NIKON Eclipse Ti, Japan).

Oil Red O Solution was employed to stain fixed cells on 6-μm thick frozen tissue sections or slides at room temperature overnight depending on the kit (ab150678, Abcam). Staining was observed by a microscope (BX51, Olympus) and quantified through ImageJ (version 1.8.0).

Nile red was used to stain kidney tissue sections. Frozen sections were reheated for 3 min, fixed at room temperature with fixative for 20 min. After incubation with a light- sensitive staining solution for 10 min at room temperature, and then washed again with PBS. Subsequently, block the slices using an anti-fluorescence quencher (S2100, Solarbio). Images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (BX51, Olympus).

Measurement of Oxygen consumption rate (OCR)

The oxygen consumption rate (OCR)was measured using the Seahorse XFe 96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Agilent Biotechnologies). Cells were seeded into XFe96 plates and stimulated by COM with or without Si-UHRF1. The analyzer then administered oligomycin, FCCP, and a combination of rotenone and antimycin A at specified time points to determine the basal respiration, ATP production, and maximal respiration. Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) was measured utilizing the Mitochondrial Stress Test Kit (103015100; Agilent). The FAO level was assessed by exogenous palmitate oxidation.

Biochemical detection

Lipid content, particularly FFAs and TG, in mouse kidney tissue, serum, and HK-2 cells was performed using biochemical kits (ADS-W-ZF013; ADS-W-ZF001, Jiangsu Aidisheng Biological Technology Co., Ltd).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISA kits (MK6291A; MK15091A, Jiangsu Sumeike Biological Technology Co., Ltd) were utilized to detect diacylglycerol (DAG) and ceramide-1-phosphate (C-1-P) in mouse kidney tissue, serum, and HK-2 cells.

Co-immunoprecipitation (CO-IP)

Whole-cell protein of HK2 cells was extracted for Co-IP, which were at 4 °C, incubated with primary antibodies for 2 h and then with magnetic beads for 2 h. Use magnetic rack to precipitate magnetic beads. The proteins were separated from the magnetic beads by SDS. Verify supernatant through western blot. The primary antibodies and concentrations were listed in Table S4.

Transmission electron microscope (TEM)

The fresh renal cortex was promptly fixed with 4℃ electron microscope fixation solution (G1102, Servicebio). Tissues were sliced into ultra-thin sections at 60–80 nm and underwent uranium-lead double staining at 4 °C for 20 min. LDs and mitochondria were observed and imaged under TEM (Hitachi, Ltd).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (San Diego, CA, USA). All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Two sets of data were analysed by T-tests, while more than two sets of data were tested by One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P < 0.05 reached statistical significance.

Results

UHRF1 is upregulated in the kidney tissue of patients with renal calculi and mouse kidney stone model

To elucidate the epigenetic role in CaOx deposition, particularly focusing on DNA methylation-related molecules, kidneys were collected from both stone model mice and control mice for transcriptome RNA sequencing. Heatmap analysis of the data highlighted UHRF1 among 16 enzymes commonly associated with DNA methylation and demethylation, revealing a significant upregulation in the expression of UHRF1 (Fig. 1A). RNA-seq identified 2160 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of which 1486 were upregulated and 674 were downregulated. The volcano plot depicted a significant upregulation of UHRF1 in mice with glyoxylate-induced kidney stones (Fig. 1B). Validation of the differentially expressed epigenetic-related genes in Fig. 1A at mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 1C-D) revealed significant increases in Mbd2, Dnmt1, Uhrf1 and Pcna. Single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-Seq) revealed increased UHRF1 expression in proximal tubular epithelial cells of CKD compared with that in normal individuals (Fig. 1E). Subsequently, IF and RT-qPCR confirmed higher UHRF1 expression in renal tissues from patients with non-functioning kidneys and renal calculi, compared to normal individuals (Fig. 1F-H). Additionally, IF results showed the levels of fibrosis markers were significantly increased in the kidneys of nephrolithiasis patients compared to normal kidneys (Fig. 1I-J). UHRF1 was mainly localized in the nucleus in human and mouse kidneys, and was positively correlated with the expression intensity of fibrosis marker α-SMA (Fig. 1K), which suggests a possible correlation between UHRF1 and kidney fibrosis. The GSE73680 dataset from the GEO database(Taguchi et al. 2016, 2017) further revealed a strong correlation between UHRF1 and fibrosis markers in kidney tissues of stone-afflicted patients, while no such correlation was observed in the normal kidney tissues (Fig. 1L).

Fig. 1.

(A) RNA transcriptome heatmap showing DNA methylation–related genes between hyperoxaluric mice and healthy controls. High-expression and low-expression genes are respectively shown in red and blue. (B) Volcano plot of DEGs in the Gly group when compared with those in the control. (C) mRNA expression levels of DEGs in panel A. (D) Dnmt3b, Mbd2, Dnmt1, Pcna, Ctcf, and Mecp2 protein levels. (E) snRNA-Seq results showing that UHRF1 expression was upregulated in the nuclei of proximal RTECs in CKD. (F-G) Immunohistochemistry and (H) RT-qPCR showing that UHRF1 expression in the renal tissues of patients with renal calculi was higher than that of healthy individuals. Scale bar = 20 μm. (I-J) Immunofluorescence detection of the renal tissue fibrosis marker molecules α-SMA, Vimentin, and Collagen I in patients with renal calculi, and quantification of the percentage of positive area. Scale bar = 20 μm. (K) Double immunofluorescent staining was performed on the kidney tissues of mice in control and Gly groups. (L) Correlation analysis of UHRF1 and ECM molecules in terms of expression levels. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001 compared with the control group

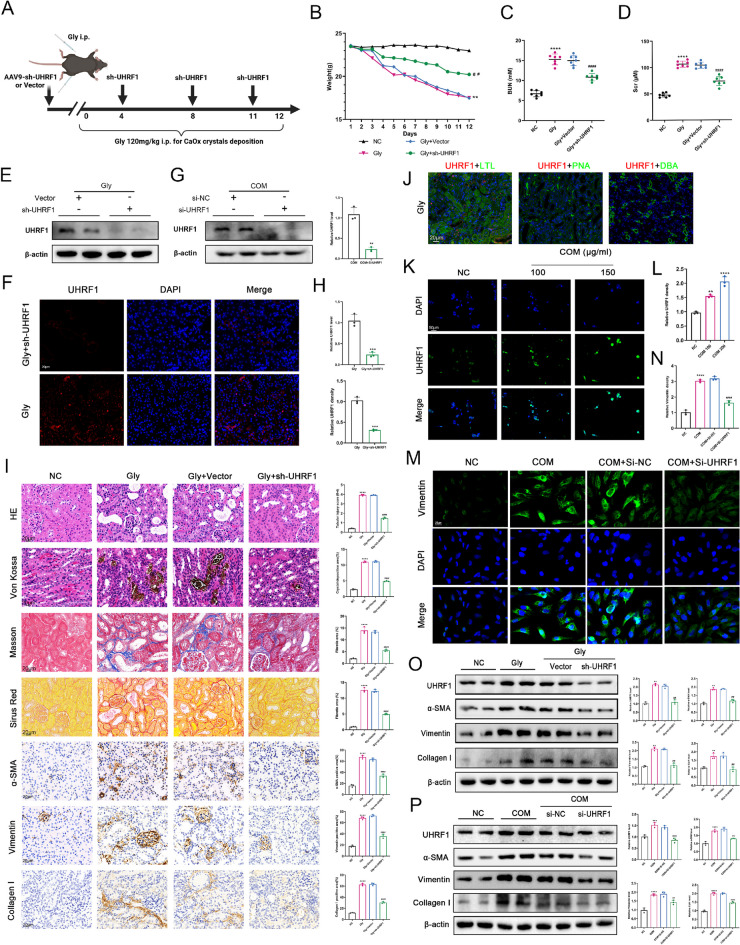

Downregulation of UHRF1 alleviates renal tubular injury, calculi deposition and interstitial fibrosis caused by CaOx deposition

To investigate whether UHRF1 promoted CaOx crystal formation and renal fibrosis, a kidney-specific UHRF1 knockdown system was utilized in mice. After a 3-day acclimatization period, serotype 9 AAV vectors (AAV9) carrying Sh-UHRF1 or Sh-NC were injected into five different sites of the renal cortex to knockdown UHRF1 in kidneys. Mice were induced with the CaOx-induced renal calculi model (Fig. 2A). Mouse weight measurements were recorded daily throughout the modelling process (Fig. 2B). Sh-UHRF1 administration reduced BUN and SCr levels in all experimental groups (Fig. 2C- D), and mitigated weight loss (Fig. 2B). Verification of UHRF1 knockdown efficiency in animal models was confirmed through western blot and IF analyses (Fig. 2E-F, H). Von-Kossa staining revealed significant calcium salt deposition in the kidneys of hyperoxaluria mice compared to controls, which was notably alleviated by sh-UHRF1. Histopathological staining demonstrated renal tubular dilatation, inflammatory cell infiltration, tubular lumen stenosis, and interstitial fibrosis in the hyperoxaluria group, all of which were attenuated in glyoxylate-injected mice treated with sh-UHRF1 (Fig. 2I). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) indicated elevated expression of fibrosis markers α-SMA, Vimentin, and Collagen I in the hyperoxaluria group, while sh-UHRF1 reduced their expression (Fig. 2I). By co-localization analysis with renal tubular markers, we found that UHRF1 was mainly expressed in proximal tubular epithelial cells, but not in distal tubules and collecting ducts (Fig. 2J). We found that the UHRF1 expression was COM concentration-dependent in HK-2 cells (Fig. 2K-L). Western blot verified si-UHRF1 knockdown efficiency of in vitro (Fig. 2G). Moreover, si-UHRF1 treatment significantly reduced CaOx-induced Vimentin expression (Fig. 2M). Classic markers of fibrosis, α-SMA, Vimentin, and Collagen I in vivo and in vitro, were reduced after UHRF1 knockdown(Fig. 2O-P). These results suggest that the knockdown of UHRF1 may inhibit renal fibrosis and suppress crystal deposition.

Fig. 2.

(A) Mouse modeling diagram. (B) Effect of sh-UHRF1 on body weight (n = 6). (C-D) SCr and BUN levels of mice in each group (n = 6). (E–F, H) Western blot and immunofluorescence (IF) to detect the knockdown efficiency of sh-UHRF1 in vivo. Scale bar = 20 μm. (I) Percentage of pathological staining and immunochemistry positive area was calculated. Scale bar = 20 μm. (J) Colocalization results of UHRF1 with markers in each renal tubular segment (LTL, PNA and DBA). Scale bar = 20 μm. (K-L) 24 h after COM treatment at different concentrations. IF staining showing the expression level of UHRF1 in HK-2 cells. (G) Western blot to detect the knockdown efficiency of si-UHRF1 in HK-2 cells. (M-P) IF and western blot detected the expression levels of fibrotic molecules in HK-2 cells (M–O) and kidney tissues in the Gly group after 150 μg/mL COM treatment. Scale bar = 20 μm. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs control group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, ####P < 0.0001 vs Gly group

Knockdown of UHRF1 alleviates lipid accumulation in vivo and in vitro

This study conducted Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis and Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis using the top 400 DEGs from RNA-seq data. Figure 3A-B display the top 8 KEGG entries and the top 5 GO biological process (GO-BO) entries, revealing significant enrichment of DEGs in "metabolic pathways", "lipid metabolism", and "fatty acid metabolism". Next, the lipid accumulation status in the kidneys of hyperoxaluric mice was examined. In the hyperoxaluric group, lipid deposition was predominantly observed in proximal tubular epithelial cells (Fig. 3C). Oil red O (ORO) staining confirmed substantial lipid deposition in kidneys of hyperoxaluric mice, which was alleviated by si-UHRF1 treatment (Fig. 3D-F). Moreover, the positive ORO area was strongly correlated with UHRF1 expression (Fig. 3E). Similar results were observed in ORO staining of the COM group and control HK-2 (Fig. 3G-H). To validate these results, oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and palmitate oxidative stress tests were performed. The results indicated that the knockdown of UHRF1 reduced the basal and maximal respiration while improving the fatty acid oxidation (FAO)-coupled OCR compared to COM groups (Fig. 3I-M). These findings collectively suggest that inhibiting UHRF1 in vivo and in vitro can alleviate ectopic lipid deposition induced by CaOx crystals.

Fig. 3.

(A-B) KEGG and GO enrichment analysis of RNA-seq data. (C) Nile red staining showing that the site of lipid deposition in the Gly group was co-localized with LTL in the proximal RTECs. (D-F) Representative images of lipid accumulation in the kidney of hyperoxaluric mice. (G-H) Representative images of Oil Red O staining in HK-2 cells. (I) OCR of NC, COM and COM + si-UHRF1 HK-2 cells were measured with a Seahorse XFe96 analyser. Basal respiration (J), ATP production (K), maximal respiration (L), and FAO level (M) of 3 groups. n = 6 biologically independent samples. Scale bar = 20 μm. ****P < 0.001 compared with the control group; ####P < 0.0001 compared with the Gly group

UHRF1 regulates CaOx crystal-induced ELD and fibrosis through the AMPK pathway

Gene set enrichment analysis revealed that “negatively regulated metabolic process” was significantly activated in the kidney of mice induced by glyoxylate (Fig. 4A). AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a pivotal regulator of lipid metabolism (Herzig and Shaw 2018), plays a central role in the metabolic reprogramming associated with renal fibrosis (Zhu et al. 2021). While the classical role of UHRF1 involves binding to DNMT1 to regulate DNA methylation (Liu et al. 2013), MethPrimer predicted CpG islands in the promoter region of AMPKα1 (Fig.S1A). To determine whether UHRF1-mediated AMPK expression was associated with DNA methylation, Western blot analysis showed no change in AMPK protein levels following si-UHRF1 treatment. However, there was an increase in phosphorylated AMPK (p-AMPK) in CaOx cultured HK-2 cells (Fig.S1B). Methylation-specific PCR (MSP), revealed no AMPK methylation in control, CaOx-treated, or si-UHRF1 groups (Fig.S1C). Consequently, the results suggested that, although UHRF1, as a DNA methyltransferase, does not directly regulate AMPK expression via DNA methylation, it modulates the phosphorylation level of AMPK via post-translational modification, thereby modulating its biological activity. Further studies are necessary to identify whether there are indirect molecules regulated by UHRF1 methylation that might alter AMPK transcription levels.

Fig. 4.

(A) The GO-BP term "negative regulation of lipid metabolic processes" enriched in Gly group. (B-C) Relative protein expression of key molecules of the UHRF1 and AMPK pathways of lipid metabolism in renal tissue lysates of control, Gly, and sh-UHRF1-treated mice. (D-E) BODIPY493/503 staining pictures of LDs in HK-2 cells. Scale bar = 20 μm. (F-I) Renal cortex samples from each group were examined by ORO staining. (F) HK-2 cells were treated with Compound C and si-UHRF1 for rescue experiments. (I-J) Representative TEM images showed the sizes and numbers of LDs. scale bar for TEM = 2 μm and 1 μm. (G-H) Scale bar for ORO staining = 20 μm. (K) Renal and serum TG and FFAs levels were determined in the indicated groups. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs. control; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, ####P < 0.0001 vs. Gly group

Western blot analysis of key downstream molecules of AMPK related to lipid synthesis, metabolism, and AMPK signalling pathway (p-AMPK, p-ACC, CPT1α, ACOX1) (Fig. 4A) revealed reduced expression in kidneys of hyperoxaluric mice, which was restored upon sh-UHRF1 treatment (Fig. 4B-C). IHC results corroborated these findings (Fig.S2). AICAR, a potent AMPK activator (Taguchi et al. 2017), significantly decreased lipid accumulation in CaOx-treated HK-2 cells (labeled with BODIPY493/503) (Fig. 4D- E). To further illustrate the role of UHRF1 in regulating AMPK pathway, we designed rescue experiments using Compound C, an AMPK activity inhibitor (Gong et al. 2022). We found that si-UHRF1 attenuated AMPK pathway activation, and fibrosis induced by Compound C (Fig. 4F, Fig.S1D). Both AICAR and sh-UHRF1 treatment substantially reduced lipid accumulation in hyperoxaluric mice compared to the untreated group (Fig. 4G-H). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) confirmed these results by showing a reduction in the number and size of LDs in the RTECs of the four groups of mice, consistent with the observed mitochondrial damage (Fig. 4I-J). Triglyceride (TG) and FFAs assays on serum and kidney tissues further validated these observations, showing significantly elevated TG and FFA levels in hyperoxaluric mice, which were reversed by drug treatments (Fig. 4K). Overall, these results indicate that UHRF1 regulates CaOx-induced lipid deposition and fibrosis by modulating the phosphorylation level of AMPK.

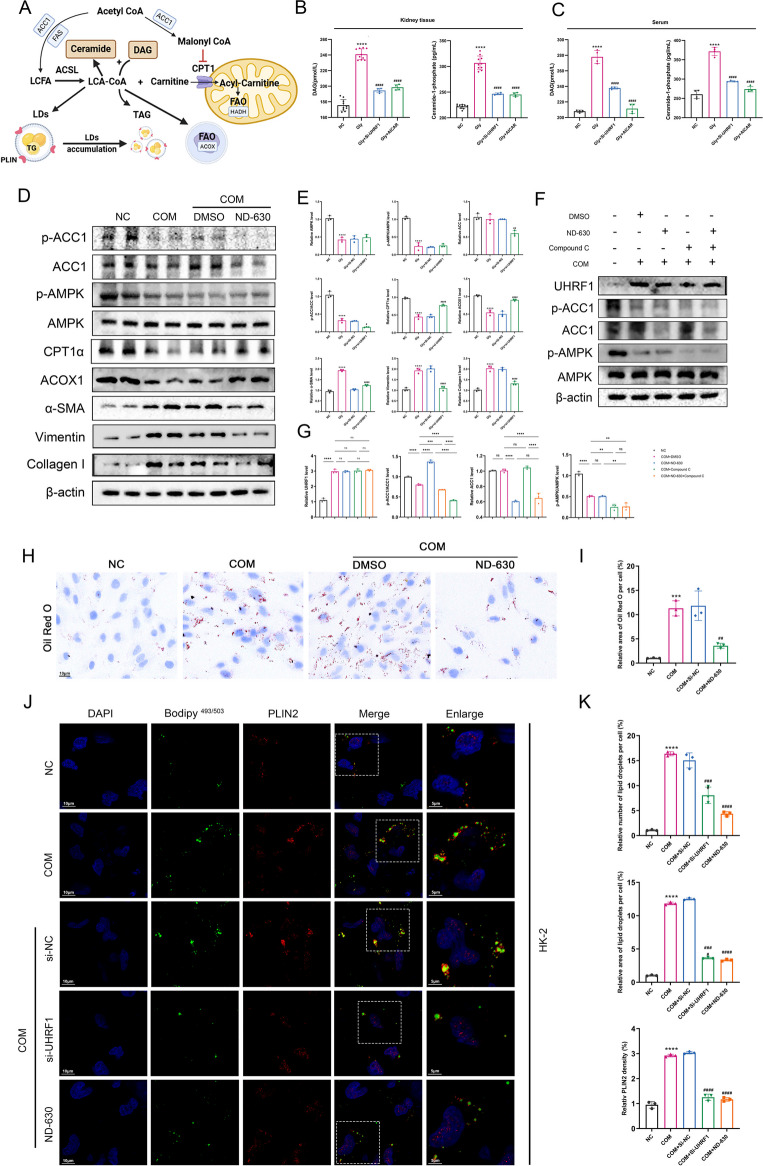

AMPK/ACC1 pathway regulates lipid accumulation process and lipotoxicity in HK-2 cells

Lipotoxic substances primarily consisting of metabolites derived from long-chain lipoyl coenzyme A(LCA-CoA) and LDs, include diacylglycerol (DAG) and ceramide-1-phosphate (C-1-P) (Schelling 2022; Weinberg 2006). Figure 5A depicts the main process and key molecules involved in DAG and C-1-P generation. Acetyl-CoA converted into long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) in the presence of ACC1 and fatty acid synthase (FAS), which are subsequently transformed into LCA-CoA by the long-chain fatty acyl CoA synthetase (ACSL) family(Zhu and Thompson 2019). LCA-CoA acts as an active intermediate in FAO (Nishi et al. 2019, Zeng et al. 2022). Notably, the accumulation of LCA-CoA is most pronounced when FAO is inhibited. The transport of LCA-CoA to the mitochondrial matrix, facilitated by CPT1α, is crucial for FAO (Nishi et al. 2019). Excessive accumulated LCA-CoA contributes partly to the lipotoxic metabolites such as C-1-P and the synthesis of TG and LDs (Schelling 2022). Moreover, the saturated carnitine shuttle inhibits LCA-CoA mediated conversion of DAG to TG, leading to the DAG accumulation, a lipotoxic metabolite. ACC1 serves as a rate-limiting enzyme in the first step of fatty acid synthesis, producing malonyl-CoA (Mal-CoA) (Brownsey et al. 1997), which also serves as an endogenous inhibitor of CPT1α, subsequently reducing FAO (Fillmore and Lopaschuk 2014; Ngo et al. 2023). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assays revealed a significant increase in both DAG and C-1-P contents in hyperoxaluric mice compared with control mice. Treatment with either si-UHRF1 or AICAR notably reduced their levels (Fig. 5B-C).

Fig. 5.

(A) Graphical representation of intracellular fatty acid synthesis and LDs formation. (B-C) DAG and C-1-P contents in the kidney tissue and serum in the indicated groups. (D-E) Relative protein levels of the AMPK/ACC1 pathway and CPT1α, ACOX1, Col-I, Vimentin, and α-SMA in the renal tissues.(F-G) Recovery experiments using ND-630 and Compound-C. (H-I) ORO detection of the effect of ND-630 on lipid deposition in COM-stimulated HK-2 cells. (J-K) Laser confocal images of BODIPY493/503 and PLIN2 were obtained under each set of conditioned treatments, and LDs and PLIN2 fluorescence was quantified. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with the control group; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, ####P < 0.0001 compared with the Gly group

Based on biochemical tests and pertinent literature (Gnoni et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2023; Gao et al. 2020), we hypothesized that the AMPK/ACC1 pathway plays a role in lipid accumulation and associated lipotoxicity during renal fibrosis. As expected, COM stimulation reduced p-AMPK and p-ACC1 levels and inhibited key FAO molecules such as CPT1α and ACOX1. ND-630, also known as Firsocostat, an ACC1 inhibitor (Harriman et al. 2016), did not affect AMPK or p-AMPK levels but increased the p-ACC1/ACC1 ratio, alleviating the reduction in CPT1α and ACOX1, potentially related to the reduced Mal-CoA production, which inhibits FAO (Fig. 5D-E). Further rescue experiments verified the regulatory relationship between AMPK and ACC1. Co-administration of Compound C with ND-630 reduced the p-ACC1/ACC1 ratio compared to usage of ND-630 alone. Combination therapy did not change p-AMPK/AMPK ratio compared to the Compound-C alone treatment group (Fig. 5F-G). ORO staining indicated that ACC1 inhibition attenuated CaOx-induced lipid accumulation (Fig. 5H-I). Confocal microscopy validated CaOx-induced LDs accumulation and detected the presence of the LDs shell protein PLIN2 on the surface of BODIPY-positive LDs (Fig. 5J-K), with PLIN2 levels consistent with the trend in changes in the size and number of LDs.

The above results demonstrate that the AMPK/ACC1 pathway is inhibited under CaOx-stimulated conditions, leading to increased lipid accumulation and lipotoxic metabolites in HK-2 cells.

UHRF1 inhibits the AMPK pathway through PP2A-mediated dephosphorylation

Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is a typical AMPK phosphatase activated by ceramide and DAG(Cornell et al. 2009; Ma et al. 2022; Bandet et al. 2019). Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays verified the interaction between AMPKα and PP2A, which increased under COM stimulation (Fig. 6A). Endogenous UHRF1 significantly increased under COM stimulation and interacted with AMPKα and PP2A(Fig.S3). Knockdown of UHRF1 during CaOx stimulation notably weakened the interaction between AMPKα and PP2A (Fig. 6B), indicating the necessity of UHRF1 for the AMPKα-PP2A interaction. Therefore, UHRF1 may serve as a connecting link between PP2A and AMPK. Knockdown of PP2A hindered the dephosphorylation of AMPK, leading to increased activation of the AMPK pathway and higher proportion of p-ACC1. Si-PPP2CA, targeting PP2A, exhibited synergistic effects with si-UHRF1 (Fig. 6C-D). Changes in the subcellular localization of AMPK is related to the UHRF1 expression in HK-2 cells. CaOx stimulation increased the nuclear translocation of AMPK compared to the uniform cellular expression observed in control cells, a phenomenon mitigated by UHRF1knockdown (Fig. 6E-F). Consequently, UHRF1 potentially regulates AMPK activity via PP2A-dependent dephosphorylation, acting as a bridge between AMPK and PP2A.

Fig. 6.

(A) Whole-cell extracts of COM-stimulated HK-2 cells were immunoprecipitated using AMPK antibody and immunoblotted using PP2A and UHRF1 antibodies. (B) Si-UHRF1 reduced the extent of PP2A interaction with AMPK. (C-D) In the presence or absence of Si-UHRF1 or Si-PPP2CA conditions, UHRF1, PP2A, and AMPK/ACC1 pathways were detected using western blot and quantified using densitometry. (E–F) UHRF1 expression levels in the control, COM, and Si-UHRF1 groups captured using a laser confocal microscope. (E–F) Representative images of UHRF1 and AMPK in the indicated groups were captured using a laser confocal microscope. Quantified by densitometry of the relative ratio of the red fluorescence intensity of AMPK in the nucleus to that of the cytoplasm and the relative fluorescence intensity of UHRF1. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with the control group; ##P < 0.01, ####P < 0.0001 compared with the Gly group

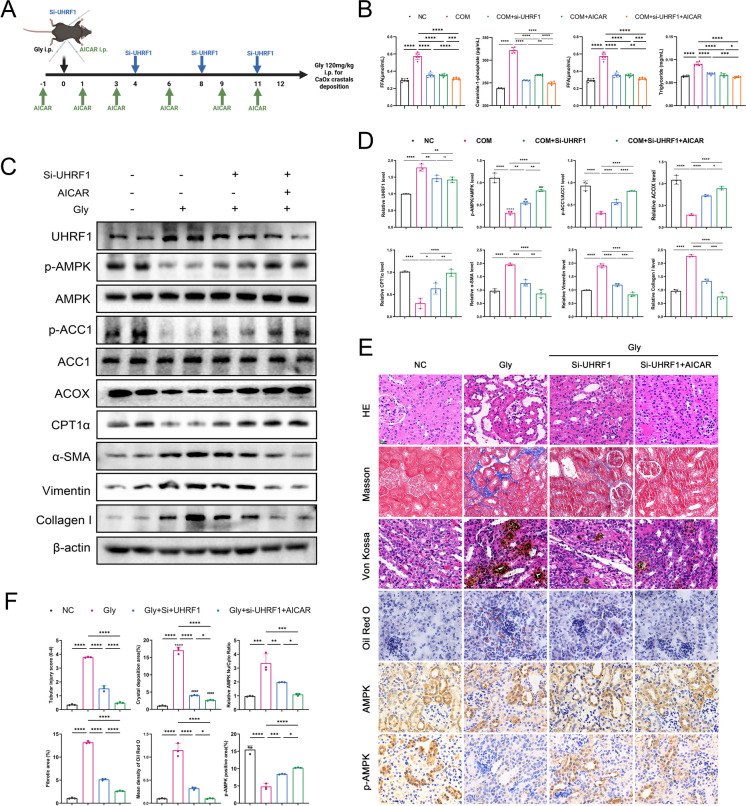

Si-UHRF1 and AICAR alleviated lipid accumulation and renal interstitial fibrosis in hyperoxaluria mice

Both si-UHRF1 and AICAR activated the AMPK pathway. Considering that AICAR, as a synthetic compound, has the defects of progressive loss of efficacy and high cost, it is not enough to apply AICAR to the treatment of chronic kidney disease. The combination therapy of small nucleotide drugs (such as si-UHRF1) and AICAR, on the one hand, can increase the therapeutic effect to deal with the complex disease; on the other hand, depending on individual differences and further clinical trials, the combination of the two drugs in the long-term treatment cycle can reduce the dosage and frequency of AICAR, maintain the efficacy, reduce the economic burden of patients, and improve the treatment effect. To explore the safety and efficacy of small nucleic acid drug therapy, and provide evidences for clinical translation, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 5 nmol methoxy-and cholesterol-modified si-UHRF1. In addition, 0.05 g/mL of AICAR was also administered to investigate the synergistic therapeutic effects with si-UHRF1 in vivo (Fig. 7A). We also performed the same synergistic treatment in the HK-2 cell model. Co-treatment decreased the levels of lipotoxic metabolites DAG and C-1-P compared not only to the calcium oxalate-modeled group, but also to si-UHRF1 or AICAR alone (Fig. 7B). Thus, the findings led to the hypothesis that si-UHRF1 and AICAR have a synergistic effect in alleviating lipid accumulation and associated lipotoxicity. In the mouse models established for this study, Western blot and histopathological staining confirmed that combining si-UHRF1 and AICAR further activated the AMPK pathway further than si-UHRF1 or AICAR alone, promoting FAO recovery and ameliorating renal fibrosis (Fig. 7C-E). IHC staining of AMPK and p-AMPK corroborated the nuclear translocation of AMPK upon CaOx stimulation (Fig. 7E-F). Treatment with both AICAR and si-UHRF1 resulted in more significant activation of the AMPK pathway, further reducing lipid accumulation and interstitial fibrosis compared to si-UHRF1 treatment alone.

Fig. 7.

(A) Si-UHRF1 combined with AICAR administration strategy in glyoxylate-induced renal calculi mouse. (B) COM-stimulated HK-2 cells were treated with si-UHRF1, AICAR, and the two in combination, and TG and FFAs contents were measured in each group. (C-D) Western blot results of UHRF1, AMPK/ACC1 pathway, FAO key molecules, and fibrosis markers in mouse kidney tissues. (E–F) HE, Von-Kossa, Masson, and ORO staining was used to evaluate renal tubular injury, CaOx deposition, interstitial fibrosis, and lipid accumulation, respectively. Immunohistochemistry was used to detect AMPK and p-AMPK expression. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

Discussion

The formation of renal stones is a complex physiological process that involves multiple stages, including stone crystal adhesion and deposition on RTECs. This triggers inflammatory responses and cellular metabolic disruptions (Washino et al. 2020, Chen et al. 2019, Kumar et al. 2022; Mulay et al. 2014). These events culminate in the deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) components (e.g., α-SMA, Fibronectin, Collagen I, etc. (Zeisberg and Neilson 2010). Inflammatory and metabolic disturbances, coupled with ECM deposition, often lead to structural damage and dysfunction of renal tubules. Long-term, recurrent renal stones in patients are often associated with renal tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis (Zisman et al. 2015), conditions exacerbated by complications like ureteral obstruction and hydronephrosis (Washino et al. 2020). This often results in CKD, a condition challenging to reverse and lacking a definitive cure (GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration 2020). Early identification of CKD risk and effective strategies to manage kidney stone formation and renal fibrosis are critical for preventing the onset CKD.

Lipids and their metabolites serve various vital structural and functional roles. They constitute essential components of cell and organelle membranes and are a primary energy source for cells. Additionally, lipids act as intracellular and intercellular signaling molecules (Martin-Perez et al. 2022; Jeon et al. 2023). Ectopic lipid deposition (ELD) and lipotoxic accumulation are recognized as risk factors for renal fibrosis. In the initial stages of CKD, lipids primarily deposit in RTECs (Mitrofanova et al. 2023), independent of systemic hyperlipidemia (Yan et al. 2018). Numerous studies indicate that disturbances in fatty acid metabolism, excessive LDs accumulation, and the formation of lipotoxic substances contribute to renal tubular injury (Liu et al. 2022a, b; Kang et al. 2015; Chung et al. 2018; Li et al. 2022; Yan et al. 2018).

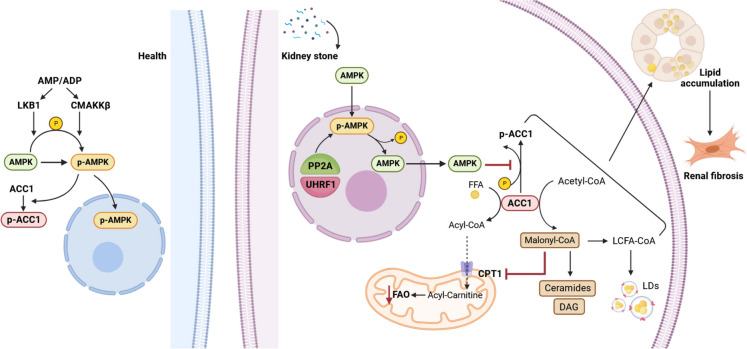

Our investigation revealed significant ELD in the kidneys of glyoxylate-induced CaOx calculi mice compared with normal kidneys, and similar results were observed in CaOx-stimulated HK-2 cells. Analysis of public databases and analysis preliminarily identified significant upregulation of UHRF1 in renal calculi patients and hyperoxaluria mice. Subsequent experiments verified the increase of UHRF1 and the concomitant accumulation of fibrosis and lipotoxic substances in the stone model. UHRF1 plays a pivotal role in regulating epigenetic inheritance, notably aiding DNMT1 in localizing DNA replication forks and maintaining DNA methylation (Liu et al. 2013). Intriguingly, recent research has uncovered a new pivotal function in regulating AMPK activity, affecting cellular carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. This occurs through its influence on AMPK's nuclear translocation and phosphorylation, independent of its involvement in DNA methylation (Xu et al. 2022). Our findings showed no change in AMPK protein levels following CaOx treatment. On the contrary, there was a notable reduction in AMPK phosphorylation. Additionally, MSP results supported that CaOx stimulation did not directly affect AMPK's DNA methylation status. Consequently, this study shifted the focus from UHRF1's epigenetic role to its regulatory effect on cellular metabolism. PP2A, a serine/threonine phosphatase, is a regulator of multiple kinases and signaling cascades (O'Connor et al. 2018; Ronk et al. 2022). There are interactions between AMPK and PP2A, and PP2A and UHRF1, and the extent of AMPK-PP2A interaction strongly correlated with the expression level of UHRF1, which was notably enhanced in CaOx-treated HK-2 cells. Furthermore, UHRF1 inhibition decreased the AMPK-PP2A interaction, maintaining AMPK phosphorylation. Notably, knocking down either PP2A or UHRF1 increased p-AMPK under CaOx conditions. CaOx treatment led to the increase of UHRF1 in nucleus, at the same time AMPK shuttled from the cytoplasm into the nucleus, where it was inactivated by PP2A-mediated dephosphorylation of facilitated by UHRF1 (Fig. 8). Our study demonstrates the specific function by which UHRF1 mediates lipid metabolism during renal fibrosis caused by kidney stones.

Fig. 8.

Under normal conditions (left side), AMPK is activated by LKB1, CAMKKβ, or AMP/ADP, which activates the AMPK pathway. In the presence of kidney stones (right side), CaOx-stimulated elevated expression of UHRF1 in RTECs, which, as a nuclear protein, bridged AMPK dephosphorylation by PP2A and increased nuclear translocation and nuclear retention of AMPK. Inhibition of the AMPK/ACC1 pathway promotes the synthesis of Mal-CoA and FFAs in the cytoplasm, leading to the accumulation of triglycerides and LDs; however, excessive accumulation of Mal-CoA is converted to lipotoxic substances such as ceramides and DAG; and finally, Mal-CoA acts as an endogenous inhibitor of CPT1α and reduces FAO. Disturbances in these lipid metabolic processes promote lipid accumulation in RTECs and renal interstitial fibrosis

AMPK regulates fatty acid metabolism through its effects on ACC1, the first rate-limiting enzyme in fatty acid synthesis. ACC1 converts acetyl coenzyme A to Mal-CoA (Brownsey et al. 1997). When AMPK is phosphorylated, the catalytic activity of ACC1 is inhibited, reducing fatty acid synthesis. However, under conditions of CaOx or COM-induced inhibition of the AMPK pathway, the p-ACC1/ACC1 ratio decreased, boosting fatty acid synthesis. Simultaneously, key enzymes involved in FAO, such as CPT1α and ACOX1, were also inhibited due to AMPK dephosphorylation (Jadeja et al. 2019; Rong et al. 2021). Mal-CoA, the direct product of ACC1, acts as an inhibitor of CPT1α, further attenuating FAO (Fillmore and Lopaschuk 2014; Ngo et al. 2023). Consequently, AMPK pathway inhibition during CaOx-induced fibrosis led to increased lipid synthesis, decreased FAO, resulting in lipid accumulation. These results highlight that changes in lipid metabolism can affect the disease process by regulating the lipid accumulation and renal fibrosis, which warrants further investigation in the future.

Chemical modification can maintain the high activity of siRNA, reduce the immunogenicity, minimize the toxicity of siRNA to experimental animals, and improve the bioavailability of siRNA in vivo, which has been widely used in the study of gene function in vivo (Herzig and Shaw 2018; Li et al. 2021). By September 2024, six siRNA drugs have appeared for market use, mainly for the treatment of rare diseases and chronic diseases. Lumasiran is an RNA interference therapeutic agent for the treatment of primary hyperoxaluria, that is currently undergoing phase 3 clinical trials. In most patients, urinary acid excretion levels significantly reduced and the course of renal failure significantly improved after 6 months of Lumasiran treatment(Garrelfs et al. 2021; Saland et al. 2024). In our study, specific UHRF1 knockdown in kidneys of mice was performed by injecting methoxy-and cholesterol-modified siRNA, which protected the siRNA from degradation by nuclease enhanced knockdown efficiency through multiple injections. The combination of si-UHRF1 and AICAR can improve the therapeutic effect for ectopic lipid deposition and renal fibrosis induced by renal calculi formation and recurrence. For the development of small nucleotide drugs targeted UHRF1 to treat kidney stones and fibrosis, more experimental and clinical evidence is needed in the future.

In conclusion, our findings strongly indicate that renal ectopic lipid deposition and renal fibrosis due to calcium oxalate stones correlates with altered lipid metabolism, which is regulated by the AMPK/ACC1 pathway and controlled by UHRF1. UHRF1 acts as a mediator in the dephosphorylation of AMPK by PP2A, influencing lipid metabolism during renal fibrosis. Furthermore, kidney-targeted delivery of si-UHRF1, in combination with AICAR, improved the therapeutic efficacy for kidney injury and fibrosis. Consequently, targeting UHRF1 appears to be a promising and attractive therapeutic option for patients with renal calculi.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Bullet Edits Limited for the linguistic editing and proofreading of the manuscript. We thank Biorender (Biorender.com) for graphic abstracts (Fig.8), animal model diagrams (Fig.2A, Fig.7A), and the mechanism diagram (Fig.5A). Permissions are provided in Supplementary Material.

Abbreviations

- CaOx

Calcium oxalate

- UHRF1

Ubiquitin-like protein containing PHD and RING finger structural domain 1

- siRNA

Small interfering RNA

- ELD

Ectopic lipid deposition

- LDs

Lipid droplets

- FFAs

Free fatty acids

- TG

Triglyceride

- DAG

Diacylglycerol

- C-1-P

Ceramide-1-phosphate

- LCFA

Long-chain fatty acids

- ACC1

Acetyl-CoA -carboxylase 1

- Mal-CoA

Malonyl-CoA

- PP2A

Protein phosphatase 2A

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- RTECs

Renal tubular epithelial cells

- BUN

Blood urea nitrogen

- Scr

Serum Creatinine

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- IF

Immunofluorescence

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- MSP

Methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction

- Co-IP

Co-immunoprecipitation

- Gly

Glyoxylate

- α-SMA

Alpha smooth muscle Actin

- Col1

Collagen I

- Vim

Vimentin

- OCR

Oxygen consumption rate

Author contributions

YSS, BJL, and BFS designed research; ZHY, XZY and LL performed research; TR, FYL, XJZ and YQX analyzed data; YSS, BJL, WL and FC wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170775, 82370765, 82270802, 82100806, 82300766 and 82272232), Shanghai Municipal Key Clinical Specialty (shslczdzk02503) and supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2042023kf0022).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. Datas is available on request from authors. The Kidney Precision Medicine Project (KPMP; https://www.kpmp.org/) provided the single-nucleus RNA-Seq dataset. The snRNA-seq dataset included 25 healthy reference and 37 CKD samples. The gene expression dataset GSE73680(Taguchi et al. 2017) from the calculi study is downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

The Kidney Precision Medicine Project (KPMP; https://www.kpmp.org/) provided the single-nucleus RNA-Seq dataset. The snRNA-seq dataset included 25 healthy reference and 37 CKD samples.

The gene expression dataset GSE73680(Taguchi et al. 2017) from the calculi study is downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of the Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University approved the clinical specimen collection (approval number: WDRY2021-KS047). The Experimental Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Wuhan University People's Hospital (approval number: WDRM20200604) permitted all animal experiments.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yushi Sun, Bojun Li, Baofeng Song, Ting Rao, and Fan Cheng contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ting Rao, Email: tinart@126.com.

Fan Cheng, Email: urology1969@aliyun.com.

References

- Alexander RT, Fuster DG, Dimke H. Mechanisms underlying calcium nephrolithiasis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2022;84:559–83. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-052521-121822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandet CL, Tan-Chen S, Bourron O, Le Stunff H, Hajduch E. Sphingolipid metabolism: New insight into ceramide-induced lipotoxicity in muscle cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3). 10.3390/ijms20030479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brownsey RW, Zhande R, Boone AN. Isoforms of acetyl-CoA carboxylase: structures, regulatory properties and metabolic functions. Biochem Soc Trans. 1997;25(4):1232–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Liu WR, Hou JB, Ding JR, Peng ZJ, Gao SY, Dong X, Ma JH, Lin QS, Lu JR, Guo ZY. Metabolomic analysis reveals a protective effect of Fu-Fang-Jin-Qian-Chao herbal granules on oxalate-induced kidney injury. Bioscience Rep. 2019;39(2):BSR20181833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng D, Wang Y, Li Z, Xiong H, Sun W, Xi S, Zhou S, Liu Y, Ni C. Liposomal UHRF1 siRNA shows lung fibrosis treatment potential through regulation of fibroblast activation. JCI insight. 2022;7(22). 10.1172/jci.insight.162831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chung KW, Lee EK, Lee MK, Goo Taeg Oh, Byung Pal Yu, Chung HY. Impairment of PPARα and the Fatty Acid Oxidation Pathway Aggravates Renal Fibrosis during Aging. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(4):1223–37. 10.1681/ASN.2017070802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell TT, Hinkovska-Galcheva V, Sun L, Cai Q, Hershenson MB, Vanway S, Shanley TP. Ceramide-dependent PP2A regulation of TNFalpha-induced IL-8 production in respiratory epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296(5):L849–56. 10.1152/ajplung.90516.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore N, Lopaschuk GD. Malonyl CoA: A promising target for the treatment of cardiac disease. IUBMB Life. 2014;66(3):139–46. 10.1002/iub.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Zhigang Xu, Huang Z, Tang Y, Yang D, Huang J, He L, Liu M, Chen Z, Teng Y. CPI-613 rewires lipid metabolism to enhance pancreatic cancer apoptosis via the AMPK-ACC signaling. J Experimental Clin Cancer Res : CR. 2020;39(1):73. 10.1186/s13046-020-01579-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrelfs SF, Frishberg Y, Hulton SA, Koren MJ, O’Riordan WD, Cochat P, Deschênes G, Shasha-Lavsky H, Saland JM, Van’t WG, Hoff DG, Fuster DM, Moochhala SH, Schalk G, Simkova E, Groothoff JW, Sas DJ, Meliambro KA, Jiandong Lu, Sweetser MT, Garg PP, Vaishnaw AK, Gansner JM, McGregor TL, Lieske JC. Lumasiran, an RNAi Therapeutic for Primary Hyperoxaluria Type 1. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(13):1216–26. 10.1056/NEJMoa2021712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):709–33. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30045-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnoni A, Di Chiara Stanca B, Giannotti L, Gnoni GV, Siculella L, Damiano F. Quercetin Reduces Lipid Accumulation in a Cell Model of NAFLD by Inhibiting De Novo Fatty Acid Synthesis through the Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase 1/AMPK/PP2A Axis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong H, Chen H, Xiao P, Huang N, Han X, Jian Zhang Yu, Yang TL, Zhao T, Tai H, Weitong Xu, Zhang G, Gong C, Yang M, Tang X, Xiao H. miR-146a impedes the anti-aging effect of AMPK via NAMPT suppression and NAD+/SIRT inactivation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):66. 10.1038/s41392-022-00886-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harriman G, Greenwood J, Bhat S, Huang X, Wang R, Paul D, Tong L, Saha AK, Westlin WF, Kapeller R, James Harwood H. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibition by ND-630 reduces hepatic steatosis, improves insulin sensitivity, and modulates dyslipidemia in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(13):E1796–805. 10.1073/pnas.1520686113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzig S, Shaw RJ. AMPK: guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(2):121–35. 10.1038/nrm.2017.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C-C, Tsai Y-S, Lin H-K. UHRF1: a novel metabolic guardian restricting AMPK activity. Cell Res. 2022;32(1):3–4. 10.1038/s41422-021-00589-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Qin Yi, Ji S, Wenyan Xu, Liu W, Sun Q, Zhang Z, Liu M, Ni Q, Xianjun Yu, Xiaowu Xu. UHRF1 promotes aerobic glycolysis and proliferation via suppression of SIRT4 in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019;452:226–36. 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadeja RN, Chu X, Wood C, Bartoli M, Khurana S. M3 muscarinic receptor activation reduces hepatocyte lipid accumulation via CaMKKβ/AMPK pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2019;169:113613. 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins Y, Markovtsov V, Lang W, Sharma P, Pearsall D, Warner J, Franci C, Huang B, Huang J, Yam GC, Vistan JP, Pali E, Vialard J, Janicot M, Lorens JB, Payan DG, Hitoshi Y. Critical role of the ubiquitin ligase activity of UHRF1, a nuclear RING finger protein, in tumor cell growth. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(12):5621–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon YG, Kim YY, Lee G, Kim JB. Physiological and pathological roles of lipogenesis. Nat Metab. 2023;5(5):735–59. 10.1038/s42255-023-00786-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HM, Ahn SH, Choi P, Ko Y-A, Han SH, Chinga F, Park ASD, Tao J, Sharma K, Pullman J, Bottinger EP, Goldberg IJ, Susztak K. Defective fatty acid oxidation in renal tubular epithelial cells has a key role in kidney fibrosis development. Nat Med. 2015;21(1):37–46. 10.1038/nm.3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S-J, Tang T, Abbott M, Viscarra JA, Wang Y, Sul HS. AMPK Phosphorylates Desnutrin/ATGL and Hormone-Sensitive Lipase To Regulate Lipolysis and Fatty Acid Oxidation within Adipose Tissue. Mol Cell Biol. 2016;36(14):1961–76. 10.1128/MCB.00244-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Lim JH, Kim MY, Kim EN, Yoon HE, Shin SJ, Choi BS, Kim Y-S, Chang YS, Park CW. The Adiponectin Receptor Agonist AdipoRon Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy in a Model of Type 2 Diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(4):1108–27. 10.1681/ASN.2017060627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Yang Z, Lever JM, Chávez MD, Fatima H, Crossman DK, Maynard CL, George JF, Mitchell T. Hydroxyproline stimulates inflammation and reprograms macrophage signaling in a rat kidney stone model. Biochimica Et Biophys Acta Mol Basis of Dis. 2022;1868(9):166442. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2022.166442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Dixon EE, Wu H, Humphreys BD. Comprehensive single-cell transcriptional profiling defines shared and unique epithelial injury responses during kidney fibrosis. Cell Metabolism. 2022;34(12):1977–98. 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Li J, Miao X, Cui W, Miao L, Cai Lu. A minireview: Role of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling in obesity-related renal injury. Life Sci. 2021;265:118828. 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Ning X, Wei L, Zhou Y, Zhao L, Ma F, Bai M, Yang X, Wang Di, Sun S. Twist1 downregulation of PGC-1α decreases fatty acid oxidation in tubular epithelial cells, leading to kidney fibrosis. Theranostics. 2022a;12(8):3758–75. 10.7150/thno.71722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Gao Q, Li P, Zhao Q, Zhang J, Li J, Koseki H, Wong J. UHRF1 targets DNMT1 for DNA methylation through cooperative binding of hemi-methylated DNA and methylated H3K9. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1563. 10.1038/ncomms2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Yi, Cheng D, Wang Y, Xi S, Wang T, Sun W, Li G, Ma D, Zhou S, Li Z, Ni C. UHRF1-mediated ferroptosis promotes pulmonary fibrosis via epigenetic repression of GPX4 and FSP1 genes. Cell Death Dis. 2022b;13(12):1070. 10.1038/s41419-022-05515-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Guo X, Cui S, Yongmei Wu, Zhang Y, Shen X, Xie C, Li J. Dephosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase exacerbates ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury via mitochondrial dysfunction. Kidney Int. 2022;101(2):315–30. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini M, Magnani E, Macchi F, Bonapace IM. The multi-functionality of UHRF1: epigenome maintenance and preservation of genome integrity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(11):6053–68. 10.1093/nar/gkab293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Perez M, Urdiroz-Urricelqui U, Bigas C, Benitah SA. The role of lipids in cancer progression and metastasis. Cell Metab. 2022;34(11):1675–99. 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrofanova A, Merscher S, Fornoni A. Kidney lipid dysmetabolism and lipid droplet accumulation in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2023;19(10):629–45. 10.1038/s41581-023-00741-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulay SR, Evan A, Anders H-J. Molecular mechanisms of crystal-related kidney inflammation and injury. Implications for cholesterol embolism, crystalline nephropathies and kidney stone disease. Nephrol, Dialysis, Transpl: Off Publication Eur Dialysis Transplant Assoc - Eur Renal Assoc. 2014;29(3):507–14. 10.1093/ndt/gft248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo J, Choi DW, Stanley IA, Stiles L, Molina AJA, Chen P-H, Lako A, Sung ICH, Goswami R, Kim M-Y, Miller N, Baghdasarian S, Kim-Vasquez D, Jones AE, Roach B, Gutierrez V, Erion K, Divakaruni AS, Liesa M, Danial NN, Shirihai OS. Mitochondrial morphology controls fatty acid utilization by changing CPT1 sensitivity to malonyl-CoA. EMBO J. 2023;42(11):e111901. 10.15252/embj.2022111901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi H, Higashihara T, Inagi R. Lipotoxicity in Kidney, Heart, and Skeletal Muscle Dysfunction. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1664. 10.3390/nu11071664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor CM, Perl A, Leonard D, Sangodkar J, Narla G. Therapeutic targeting of PP2A. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2018;96:182–93. 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peerapen P, Thongboonkerd V. Kidney Stone Prevention. Advances In Nutrition (Bethesda, Md). 2023;14(3):555–69. 10.1016/j.advnut.2023.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong Q, Han B, Li Y, Yin H, Li J, Hou Y. Berberine reduces lipid accumulation by promoting fatty acid oxidation in renal tubular epithelial cells of the diabetic kidney. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:729384. 10.3389/fphar.2021.729384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronk H, Rosenblum JS, Kung T, Zhuang Z. Targeting PP2A for cancer therapeutic modulation. Cancer Biol Med. 2022;19(10):1428–39. 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2022.0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saland JM, Lieske JC, Groothoff JW, Frishberg Y, Shasha-Lavsky H, Magen D, Moochhala SH, Simkova E, Coenen M, Hayes W, Hogan J, Sellier-Leclerc A-L, Willey R, Gansner JM, Hulton S-A. Efficacy and safety of lumasiran in patients with primary hyperoxaluria type 1: results from a phase III clinical trial. Kidney International Reports. 2024;9(7):2037–46. 10.1016/j.ekir.2024.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelling JR. The Contribution of Lipotoxicity to Diabetic Kidney Disease. Cells. 2022;11(20):3236. 10.3390/cells11203236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Li B, Zhou X, Rao T, Cheng F. The identification of key molecules and pathways in the crosstalk of calcium oxalate-treated TCMK-1 cells and macrophage via exosomes. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):20949. 10.1038/s41598-024-71755-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi K, Hamamoto S, Okada A, Unno R, Kamisawa H, Naiki T, Ando R, Mizuno K, Kawai N, Tozawa K, Kohri K, Yasui T. Genome-Wide Gene Expression Profiling of Randall’s Plaques in Calcium Oxalate Stone Formers. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(1):333–47. 10.1681/ASN.2015111271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi K, Okada A, Hamamoto S, Unno R, Moritoki Y, Ando R, Mizuno K, Tozawa K, Kohri K, Yasui T. M1/M2-macrophage phenotypes regulate renal calcium oxalate crystal development. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35167. 10.1038/srep35167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribarri J. Chronic kidney disease and kidney stones. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2020;29(2):237–42. 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Fan J, Huang G, Li J, Zhu Xi, Tian Ye, Li Su. Prevalence of kidney stones in mainland China: A systematic review. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41630. 10.1038/srep41630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Deng Q, Liang H. Recent advances on the mechanisms of kidney stone formation. Int J Mol Medi. 2021;48(2):1–10. 10.3892/ijmm.2021.4982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washino S, Hosohata K, Miyagawa T. Roles played by biomarkers of kidney injury in patients with upper urinary tract obstruction. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(15):5490. 10.3390/ijms21155490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg JM. Lipotoxicity. Kidney Int. 2006;70(9):1560–6. 10.1038/sj.ki.5001834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Zhou X, Ye Z, Weimin Yu, Ning J, Ruan Y, Yuan R, Lin F, Ye P, Zheng Di, Rao T, Cheng F. Construction and analysis of immune infiltration-related ceRNA network for kidney stones. Front Genet. 2021;12:774155. 10.3389/fgene.2021.774155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Ding G, Liu C, Ding Y, Chen X, Huang X, Zhang C-S, Shanxin Lu, Zhang Y, Huang Y, Chen Z, Wei W, Liao L, Lin S-H, Li J, Liu W, Li J, Lin S-C, Ma X, Wong J. Nuclear UHRF1 is a gate-keeper of cellular AMPK activity and function. Cell Res. 2022;32(1):54–71. 10.1038/s41422-021-00565-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Qi, Yuan Song Lu, Zhang ZC, Yang C, Liu S, Yuan X, Gao H, Ding G, Wang H. Autophagy activation contributes to lipid accumulation in tubular epithelial cells during kidney fibrosis. Cell Death Discovery. 2018;4:2. 10.1038/s41420-018-0065-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Z, Xia Y, Zhou X, Li B, Weimin Yu, Ruan Y, Li H, Ning J, Chen L, Rao T, Cheng F. CXCR4 inhibition attenuates calcium oxalate crystal deposition-induced renal fibrosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;107:108677. 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisberg M, Neilson EG. Mechanisms of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(11):1819–34. 10.1681/ASN.2010080793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng G, Mai Z, Xia S, Wang Z, Zhang K, Wang Li, Long Y, Ma J, Li Yi, Wan SP, Wenqi Wu, Liu Y, Cui Z, Zhao Z, Qin J, Zeng T, Liu Y, Duan X, Mai X, Yang Z, Kong Z, Zhang T, Cai C, Shao Yi, Yue Z, Li S, Ding J, Tang S, Ye Z. Prevalence of kidney stones in China: an ultrasonography based cross-sectional study. BJU Int. 2017;120(1):109–16. 10.1111/bju.13828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng S, Fan Wu, Chen M, Li Y, You M, Zhang Y, Yang P, Wei Li, Ruan XZ, Zhao L, Chen Y. Inhibition of Fatty Acid Translocase (FAT/CD36) Palmitoylation Enhances Hepatic Fatty Acid β-Oxidation by Increasing Its Localization to Mitochondria and Interaction with Long-Chain Acyl-CoA Synthetase 1. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2022;36(16–18):1081–100. 10.1089/ars.2021.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhang W, Yang Li, Zhao W, Liu Z, Wang E, Wang J. Phytochemical gallic acid alleviates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease via AMPK-ACC-PPARa axis through dual regulation of lipid metabolism and mitochondrial function. Phytomed : Int J Phytotherapy Phytopharmacol. 2023;109:154589. 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Thompson CB. Metabolic regulation of cell growth and proliferation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(7):436–50. 10.1038/s41580-019-0123-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Jiang L, Long M, Wei X, Hou Y, Yujun Du. Metabolic reprogramming and renal fibrosis. Front Med. 2021;8:746920. 10.3389/fmed.2021.746920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisman AL, Evan AP, Coe FL, Worcester EM. Do kidney stone formers have a kidney disease? Kidney Int. 2015;88(6):1240–9. 10.1038/ki.2015.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. Datas is available on request from authors. The Kidney Precision Medicine Project (KPMP; https://www.kpmp.org/) provided the single-nucleus RNA-Seq dataset. The snRNA-seq dataset included 25 healthy reference and 37 CKD samples. The gene expression dataset GSE73680(Taguchi et al. 2017) from the calculi study is downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

The Kidney Precision Medicine Project (KPMP; https://www.kpmp.org/) provided the single-nucleus RNA-Seq dataset. The snRNA-seq dataset included 25 healthy reference and 37 CKD samples.

The gene expression dataset GSE73680(Taguchi et al. 2017) from the calculi study is downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).