Abstract

Background

Osteoporosis significantly increases the risk of vertebral fractures, particularly among postmenopausal women, decreasing their quality of life. These fractures, often undiagnosed, can lead to severe health consequences and are influenced by bone mineral density and abnormal loads. Management strategies range from non-surgical interventions to surgical treatments. Moreover, the interaction between immune cells and bone cells plays a crucial role in bone repair processes, highlighting the importance of osteoimmunology in understanding and treating bone pathologies.

Methods

This study aims to investigate the xCell signature-based immune cell profiles in osteoporotic patients with and without vertebral fractures, utilizing advanced predictive modeling through the XGBoost algorithm.

Results

Our findings reveal an increased presence of CD4 + naïve T cells and central memory T cells in VF patients, indicating distinct adaptive immune responses. The XGBoost model identified Th1 cells, CD4 memory T cells, and hematopoietic stem cells as key predictors of VF. Notably, VF patients exhibited a reduction in Th1 cells and an enrichment of Th17 cells, which promote osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. Gene expression analysis further highlighted an upregulation of osteoclast-related genes and a downregulation of osteoblast-related genes in VF patients, emphasizing the disrupted balance between bone formation and resorption. These findings underscore the critical role of immune cells in the pathogenesis of osteoporotic fractures and highlight the potential of XGBoost in identifying key biomarkers and therapeutic targets for mitigating fracture risk in osteoporotic patients.

Keywords: Osteoporosis, Vertebral fractures, XGBoost, Th17 cell differentiation

Background

Osteoporosis, a condition marked by the weakening of bones, substantially escalates the risk of fractures, particularly in the spine, posing significant health risks including chronic pain, mobility loss, and a decline in the quality of life. Vertebral compression fractures are notably common among postmenopausal women, where osteoporosis stands out as a primary risk factor. The approach to managing these fractures ranges from non-surgical methods focusing on alleviating pain and restoring function to surgical interventions for more severe cases [1]. Vertebral fractures exhibit a complex classification spectrum, entailing various types and degrees of deformity, with bone mineral density being a key factor linked to the fracture’s severity and frequency [2]. While osteoporotic vertebrae can sustain normal daily loads, they are susceptible to unusual “error” loads, which, although not typically traumatic, can precipitate fractures [3]. Radiographic diagnosis plays a pivotal role in identifying both symptomatic and asymptomatic vertebral fractures, which are frequently overlooked in clinical assessments. Employing standardized grading schemes is crucial for an accurate diagnosis [4, 5]. Pharmaceutical treatments for osteoporosis aim at diminishing bone turnover and augmenting bone mass to mitigate the risk of vertebral fractures [6]. The quantity and gravity of these fractures adversely affect the health-related quality of life among postmenopausal women with osteoporosis [7]. A notable portion of this demographic has undetected osteoporotic vertebral fractures, with a high prevalence of densitometric osteoporosis [8]. Additionally, osteoporotic vertebral fractures may occasionally trigger neurological symptoms owing to the backward pushing of bone fragments that narrows the spinal canal [9]. However, it is essential to acknowledge that not all vertebral fractures in the elderly stem from osteoporosis; some may be due to trauma, occurring in vertebrae with normal bone density [10].

The vital role of immune cells in the healing process of bone fractures is a complex and significant area of study. It delves into the dynamic interactions between the immune system and the mechanisms of bone repair. Following a fracture, immune cells are pivotal in the physiological response, orchestrating the mobilization and activation of various cell types essential for bone regeneration. Research highlights the indispensable function of macrophages in bone healing. These cells signal to their counterparts within the fracture callus, influencing the healing trajectory by secreting cytokines, which serve as critical modulators of the repair process [11]. In the context of chronic spinal cord injury, there’s a noticeable impairment in the primary antibody responses. This impairment hinders the ability to develop optimal antibody responses to new antigens. Despite this, pre-existing humoral immunity and secondary responses appear to remain intact [12]. Additionally, the realm of sex differences sheds light on the distinct pronociceptive immune responses following a fracture. Women exhibit enduring immune alterations in both the fractured limb and spinal cord, characterized by variations in cytokine signaling and microglial activity [13]. An intriguing observation is the altered immune response in fractures coinciding with traumatic brain injury. There’s a reported reduction in neutrophils and mast cells at the fracture site, a phenomenon that might contribute to an increase in bone content by diminishing callus remodeling [14]. The integrity and functionality of immune cells, encompassing elements from both the innate and adaptive immune systems, are crucial for effective fracture healing. Any alterations in these cells could potentially hinder the repair process, emphasizing the need for a deeper understanding of these interactions [15].

The dynamic interplay between the immune system and bone cells, especially osteoclasts and osteoblasts, underpins the fundamental mechanisms governing bone integrity and pathological conditions. Osteoclasts, which originate from the hematopoietic myeloid lineage, have a pivotal role that extends beyond mere bone resorption; they influence osteoblast functions and contribute significantly to immune responses, thereby playing a versatile role in bone remodeling and osteoimmunology [16–18]. In the realm of fracture healing, the Th17 subset of T-lymphocytes emerges as a key player, producing IL-17 F, a cytokine instrumental in the maturation of osteoblasts and subsequent bone repair, highlighting the direct impact of immune cells on osteoblast activity during this critical process [19]. Moreover, the orchestration between osteoclasts and osteoblasts is meticulously regulated by cytokines such as RANKL and M-CSF. These cytokines are not only crucial for the formation of osteoclasts but are also expressed by cells of the osteoblast lineage, thus emphasizing the interconnected regulatory mechanisms governing their activities [17, 20]. The influence of osteoclast precursors and mature osteoclasts extends to the modulation of differentiation in various cell types, including those in the osteoblastic lineage, and they play a role in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cell trafficking, underscoring their comprehensive involvement in both bone remodeling and immune system interactions [18]. Furthermore, the engagement of immune cells, notably T and B cells, in the process of osteoclastogenesis, and their potential impact on osteoblast function, presents an intriguing facet of the osteoimmunological interface, although the specifics of these interactions warrant further investigation [21]. Understanding these complex relationships is paramount for the development of innovative treatments aimed at mitigating skeletal diseases such as osteoporosis, where the balance between bone formation and resorption is perturbed.

In order to comprehensively understand the potential impacts of having or not having vertebral fractures on immune and stromal cells in patients with clinical osteoporosis, this study adopts a multifaceted strategy. Utilizing the cell signature analysis, we examine the differences in immune cell populations in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of clinical patients, as published by Neto et al. [22]. This analysis is supplemented by the use of the XGBoost algorithm to predict key immune cells associated with vertebral fractures. Additionally, the L1000 Ligand assay is employed to identify the most significant gene sets of cytokines or growth factors. In conjunction with EnrichR and relevant keywords, we assess the enrichment of gene sets related to immune cells and bone-forming/osteolytic cells in the Gene Ontology (GO) and various Pathway Databases. In summary, our integrative approach leverages advanced bioinformatic and molecular techniques to dissect the intricate interplay between immune cells and bone metabolism in the context of vertebral fractures in osteoporosis. By identifying key cellular and molecular mediators, this study not only enhances our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of bone fragility but also paves the way for novel therapeutic targets.

Methods

Data accessibility and x-Cell signature scoring

Here we describe the dataset utilized in this study, sourced from the research conducted by Neto et al. [22]. The dataset comprises a cohort of 36 postmenopausal women diagnosed with osteoporosis, aged between 73 and 91 years with a median age of 82. All participants are of Latin American ethnicity, indicating a high degree of homogeneity among the patients. Among these women, 24 have experienced vertebral fractures (VF), while the remaining 12 exhibit no such fractures (NVF). After downloading the dataset, we conducted an ID conversion to standardize gene identifiers across different databases. The log₂-transformed expression values were reverted back to their original scale. The data were then organized into a matrix format suitable for computational processing. The Immune Oncology Biological Research (IOBR) package (v0.99.8) in R (v4.3.3) was utilized for implementing x-Cell signature scoring. The single sample gene-set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) based x-Cell signature scores were computed based on a reference panel of gene signatures associated with specific cell types, including various immune and stromal cells. For data visualization, we generated heatmaps and boxplots using ComplexHeatmap (v2.18.0) and ggplot2 (v3.5.1) packages. The cell types were categorized into five major categories according to the xCell signature’s original classification: Lymphoids, Myeloids, Stromals, Stem cells, and Others. The Lymphoid category was further subdivided into Innate and Adaptive immune responses. Within the Adaptive subcategory, further distinction was made among B cell lineage, CD4 T cell lineage, and CD8 T cell lineage. The Innate subcategory was subdivided into Monocyte lineage and Dendritic cell lineage. The Stromal category specifically isolated endothelial cells as a distinct group.

XGboost machine learning approach

The VF status was encoded as a binary variable, with VF assigned a value of 1 and NVF a value of 0. The data was randomly divided into a training set comprising 75% of the patients and a testing set with the remaining 25%. This division was critical for training the model while ensuring an unbiased evaluation of its predictive performance. We chose XGBoost as our predictive tool due to its exceptional performance in handling structured data and its ability to capture complex nonlinear relationships. XGBoost is known for its efficiency, scalability, and robustness against overfitting, making it well-suited for our dataset and classification task [23]. We configured the XGBoost model using xgboost package (v1.7.8.1) in R with specific parameters to optimize the analysis. The model was set with an objective of binary logistic regression. To determine the optimal hyperparameters, we conducted a grid search combined with five-fold cross-validation. We tested various values for key parameters to enhance model performance while preventing overfitting. The learning rate was fine-tuned by evaluating values ranging from 0.01 to 0.1 in increments of 0.01. Through cross-validation, we found that a learning rate of 0.05 provided the best balance between training speed and model accuracy, helping to prevent overfitting while allowing the model to learn effectively. The maximum depth of the decision trees was tested between 3 and 15. A max depth of 10 was selected because it captured the necessary complexity in the data without leading to overfitting, as indicated by stable validation scores during cross-validation. We used a column sample by tree ratio of 0.5 after experimenting with values between 0.3 and 1.0. This setting helped reduce overfitting by randomly sampling features for each tree, which improved the model’s generalization capability. The minimum child weight parameter was set to 1 based on grid search results, ensuring that the model did not create nodes with too few samples, which could lead to overfitting. After splitting the dataset, we applied SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) to address class imbalance in the training set. Specifically, we used a K value of 6 and a duplication size of 3, effectively generating additional synthetic minority-class examples. Model performance was assessed using SHAP values to interpret the feature influences on the prediction outcomes. The F1 score, precision, and recall were calculated using the caret package (v6.0-94), while the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) was computed using mltools package (v0.3.5). Additionally, the model’s discriminative ability was evaluated through the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, focusing on the area under the curve (AUC) metric. For robust validation, the model underwent 100 repeated training cycles to test its stability and reliability across various data splits. This extensive testing helped in identifying the most consistent and influential features, with an emphasis on the top 20 features that appeared most frequently across different iterations. This approach ensures that the model’s findings are both reliable and applicable to general clinical settings involving osteoporosis and fracture risk assessment.

L1000 ligand perturbation signature

We utilized the DESeq2 package (v1.42.1) to compute fold changes in gene expression between the VF and NVF groups. The fold changes were then ranked from highest to lowest, forming the gene symbol named gene list for subsequent enrichment analysis. Using the clusterProfiler (v4.10.1) package’s GSEA function, we evaluated the enrichment scores of individual ligands against the VF versus NVF differential expression profiles. The LINCS L1000 Ligand Perturbations gene sets includes a diverse array of ligand associated signatures across various cell lines, which is accessible in SigCom LINCS website (https://maayanlab.cloud/sigcom-lincs/#/Download) [24]. To identify significantly enriched ligands, we applied an FDR threshold of < 0.25. This stringent filtering step ensures the selection of ligands with robust associations to the gene expression changes observed between VF and NVF conditions. For a comprehensive evaluation of ligands with substantial impact, we further analyzed those meeting the FDR < 0.25 criterion by stacking their NES based on gene symbols. This approach enabled us to aggregate and visualize the influence of significant ligands in a consolidated manner. We employed a color-coding scheme to represent FDR values, facilitating the assessment of statistical significance and the identification of key ligands driving the differential gene expression patterns.

STRING based cellular component analysis

To determine the protein complexes and cellular components linked to these ligands, we performed an analysis using the STRING database [25]. Initially, ligands from the L1000 signatures that met the FDR < 0.25 criterion were screened. These genes were then input into the STRING database to explore their interactions and associations. STRING analysis provides a comprehensive view of the protein-protein interaction networks, facilitating the identification of cellular components to which these genes belong. We focused on the Compartment category of the Gene Ontology cellular components (GOCC) terms during the STRING analysis. This allowed us to specifically evaluate which cellular structures or complexes the genes associated with each enriched ligand were part of. To visualize the relationships between the enriched ligands and their corresponding cellular components, we used the GOchord function from the GOplot (v1.0.2) package in R.

ClusterProfiler based GSEA visualization

We utilized the EnrichR database to perform keyword screening and obtain highly relevant gene-set collections [26]. For example, in Fig. 4, we used “CD4” as a keyword input in EnrichR, selecting the “Cell Marker 2024” library to extract gene sets containing the substring “Blood.” The resultant gene sets were exported in GMT format for further analysis. Using the ClusterProfiler package, we conducted GSEA on the selected gene sets. The ClusterProfiler tool facilitates the functional interpretation of genomic data by identifying significantly enriched pathways or gene sets. The results were visualized using the plotting functions provided by ClusterProfiler. The ridgeplot function was employed to visualize the distribution of the fold changes of genes in corresponding gene-sets. The heatplot function was used to generate heatmaps, providing a detailed view of the expression levels and enrichment patterns of the identified genes across different gene-sets. The cnetplot function was used to create network plots, illustrating the relationships between gene sets and their corresponding genes, facilitating an understanding of the interconnectedness of the biological pathways involved. Specific coding modifications were made to tailor the visualizations to our needs. These adjustments ensured that the plot accurately represented the data and highlighted key findings effectively. The modifications included adjustments to the color schemes, axis labels, and plot dimensions to enhance readability and interpretability.

Fig. 4.

Visualization of the L1000 Ligand signature GSEA in PBMC samples from patients with osteoporosis. The volcano plot (top left) displays the enrichment of various cytokines and growth factors with the corresponding negative log p-value against normalized enrichment score (NES), indicating significant associations. The bar plot (top right) summarizes the stacked NES values, with color intensity representing the q-value. The network diagram (bottom left) illustrates interactions among the enriched ligands. The chord diagram (bottom right) depicts the relationships between ligands and their associated cellular components, based on their NES values

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.3.3). Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs) and were compared using independent t-tests.

Results

Differential cellular profiles in osteoporotic patients with and without vertebral fractures

In a pioneering study analyzing PBMC samples from 36 clinical osteoporosis patients published by Neto et al., we observed distinct cellular landscapes between patients with vertebral fractures (VF) and those without (NVF). Using the xCell algorithm to derive cell type enrichment scores, we quantified the relative abundance of various immune and stromal cell types in the samples. xCell signature is a computational method that performs cell type enrichment analysis from gene expression data, providing a comprehensive view of cellular heterogeneity within tissue samples [27]. The results, presented in a heatmap and accompanying violin plots, highlight significant disparities in the immune and somatic cell profiles of these two patient groups, which may underpin the pathology of osteoporotic fractures. The heatmap provides a comprehensive visualization of the differential expression of cell types, with the red and blue gradients denoting higher and lower abundance, respectively. The violin plots provide further clarification regarding these discrepancies, offering a distinct visual representation of the cellular distribution variance. It is noteworthy that the VF group exhibited considerably elevated levels of CD4 T cell lineage. These findings are consistent with previous research that has identified the pivotal role of the adaptive immune response in bone remodeling and repair mechanisms. Interestingly, lymphoid cells associated with CD8 T cells show a significant difference between the two groups, hinting at a more complex interplay between different immune system components in osteoporotic conditions.

Detailed analysis of immune cell subsets in osteoporosis patients with vertebral fractures

Expanding upon the initial cellular profile analysis in Fig. 1, we delved deeper into the immune system’s intricacies by examining individual immune cell subsets among osteoporotic patients with and without VF. Our stratified evaluation, presented in Fig. 2, offers a granular view of the adaptive immune landscape, with particular emphasis on the B cell and T cell lineages. The insights gained from this analysis could prove vital in understanding the immunological shifts associated with osteoporosis and fracture susceptibility. In the realm of adaptive immunity, we detected a heightened score for regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the VF group (p = 0.0187), suggesting a possible role for immune regulation in the pathogenesis of fractures. This observation aligns with existing research positing that Tregs can influence bone metabolism indirectly by modulating immune responses. In contrast, the B cell lineage did not exhibit significant differences across subsets, including class-switched memory B cells (p = 0.726), memory B cells (p = 0.185), naïve B cells (p = 0.324), plasma cells (p = 0.578), and pro B cells (p = 0.551), indicating a potentially lesser role for humoral immunity in the direct context of fracture occurrence. Significantly, the CD4 + T cell lineage displayed marked variations, particularly in naïve T cells (p = 0.00103), central memory T cells (Tcm, p = 0.00936), and effector memory T cells (Tem, p = 0.0828), with the VF group presenting higher scores. CD4+ memory T cells (p = 0.0374) and total CD4+ T cells (p = 0.00526) were also elevated in the VF group. These findings could reflect an ongoing or past immune response, potentially related to the repair processes or chronic inflammation associated with osteoporotic fractures. The presence of central memory T cells (Tcm) and effector memory T cells (Tem) was particularly notable, with the VF group showing increased levels of CD4+ Tcm, which may suggest a sustained immunological readiness or a memory of previous inflammatory insults related to bone integrity. Moreover, within the CD8+ T cell lineage, we noted a reduction in the score of effector memory T cells (CD8+ Tem, p = 0.0434) in the VF group. This finding hints at a moderate cytotoxic response or a potential mechanism to tackle osteoclastogenic processes that lead to bone loss. Other subsets, including CD8+ naïve T cells (p = 0.213), CD8+ Tcm (p = 0.354), and total CD8+ T cells (p = 0.158), did not exhibit significant differences between groups.

Fig. 1.

Comprehensive immune and somatic cell profile comparisons between osteoporotic patients with VF and those without vertebral fractures (NVF). Left panel: Heatmap representation of standardized xCell scores, indicating the relative abundance of cell types in PBM) samples from 36 clinical osteoporosis patients. The heatmap color gradient (red to blue) reflects high to low standardized scores. Right panel: Violin plots depicting the standardized xCell scores across various immune and somatic cell lineages, contrasting between the VF (orange) and NVF (blue) groups. Significant differences were identified through the use of independent t-tests, and p-values were included above each comparison. Significant results are indicated with asterisks (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001)

Fig. 2.

Detailed stratification and comparison of immune cell subsets within the PBMC samples from osteoporotic patients, classified by the presence and absence of vertebral fractures. The boxplots detail the standardized xCell scores of specific lymphoid cell populations, encompassing adaptive immune cells, B cell lineage, CD4+ T cell lineage, and CD8+ T cell lineage, for both VF (red) and NVF (blue) groups. Statistically significant differences are indicated (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). Tcm: central memory T cell; Tem: effector memory T cell; Treg: regulatory T cells; Tgd: gamma-delta T cells

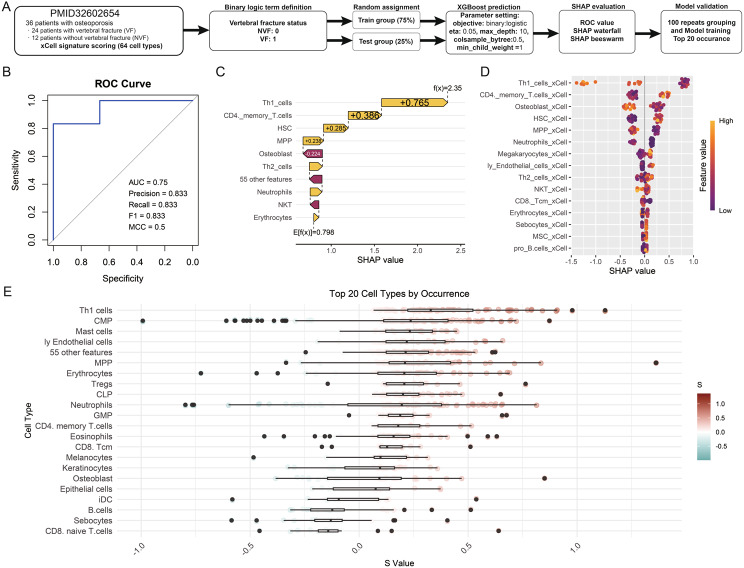

Predictive modeling of VF in osteoporosis using XGBoost and SHAP values

The flowchart illustrates the workflow of this study, encompassing patient data collection, model training, and evaluation processes (Fig. 3A). The study involved 36 osteoporosis patients, of whom 24 had vertebral fractures and 12 had non-vertebral fractures. Immune cell profiles were assessed using the xCell signature, encompassing 64 immune cell types derived from PBMC samples. To predict VF status, the data was divided into a training group (75%) and a test group (25%), ensuring an unbiased evaluation of the model’s performance. Using the XGBoost algorithm, binary classification was performed to distinguish between VF and NVF patients. The model parameters were optimized (e.g., eta = 0.05, max_depth = 10, colsample_bytree = 0.5, min_child_weight = 5) to enhance predictive accuracy. Model outputs were evaluated using metrics such as ROC-AUC, precision, recall, F1 score, and MCC, confirming its robustness. The SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) framework was employed to interpret feature importance, offering insights into the contribution of individual immune cell types to VF prediction. The analysis was further validated through 100 repeats of data randomly grouping and model training, with the top 20 immune cell types ranked by occurrence. This comprehensive workflow integrates machine learning and immune profiling to elucidate potential biomarkers and mechanisms underlying fracture susceptibility in osteoporosis patients. The model’s predictive capacity is evidenced by the ROC curve, boasting an AUC of 0.889, precision of 0.8, recall of 1, F1 score of 0.889, and MCC of 0.8, indicating a strong model with high discriminatory power (Fig. 3B). Through SHAP analysis, the model offers an interpretable representation of the contribution of each immune cell type to VF prediction. SHAP values nearing 1 suggest a stronger association with VF, providing a crucial measure for clinical decision-making. The waterfall chart for sample prediction highlights the significant contribution of specific features to the model’s output (Fig. 3C). For example, Th1 cells (SHAP value = + 0.765), CD4 memory T cells (+ 0.385), and hematopoietic stem cells (HSC, + 0.238) exhibited higher SHAP values, underscoring their potential roles as predictive biomarkers for VF in osteoporotic patients. Notably, Th1 cells emerged as the top contributing feature, consistent with their role in inflammation and autoimmunity, both of which are implicated in osteoporosis pathophysiology. Similarly, CD4 memory T cells reflect chronic immune activation, which may play a role in bone remodeling processes. The SHAP beeswarm plot further corroborates these findings, with immune cells such as Th1 cells, CD4 memory T cells, and neutrophils showing consistent importance across samples (Fig. 3D). The top 20 cell types by occurrence, visualized in the lower panel, highlight a diverse range of immune cells correlating with vertebral fracture status. Alongside the aforementioned Th1 cells and memory T cells, multipotent progenitors (MPP), megakaryocytes, and neutrophils also demonstrated high SHAP values. Conversely, features such as osteoblasts and erythrocytes exhibited negative SHAP values, suggesting that their decreased occurrence or altered functional status might either be protective or have a non-contributory role in VF development (Fig. 3E). This counterintuitive finding could shed light on new aspects of osteoporosis pathology, potentially implicating systemic factors like vascular health or oxygenation in bone quality.

Fig. 3.

Application of XGBoost machine learning algorithm to identify the association between immune cell profiles and clinical outcomes in osteoporotic patients. (A) Overview of the study workflow. (B) Model performance was validated using metrics including ROC-AUC, precision, recall, F1 score, and MCC. (C) SHAP waterfall chart illustrating the individual contributions of key features to model predictions for VF. (D) SHAP beeswarm plot depicting the influence of various immune cell types on VF prediction. Each dot represents a SHAP value for a specific cell type across samples, with color intensity (purple to orange) indicating feature values from low to high. (E) Top 20 immune cell types ranked by occurrence, with boxplots summarizing their contributions to VF prediction. The color gradient represents the feature values associated with each cell type, with darker orange indicating higher values and darker purple indicating lower values

Cytokine and growth factor enrichment in PBMCs of vertebral fracture patients through L1000 ligand signature and GSEA

Our comprehensive assessment of cytokine and growth factor profiles in PBMC samples from VF patients leverages the L1000 ligand signature and GSEA to elucidate the molecular underpinnings of osteoporosis-related fractures. The L1000 ligand signature is derived from the Library of Integrated Network-based Cellular Signatures (LINCS) project, which provides a high-throughput gene expression profiling method [24]. This method measures the transcriptional responses of cells to a wide array of ligands—molecules that bind to receptors to induce a biological response. By analyzing these ligand-induced gene expression signatures, researchers can identify key signaling pathways and molecular interactions involved in various diseases. Through this high-throughput approach, we have unearthed a robust constellation of signaling molecules enriched in the context of VF, providing insight into the complex biological interactions at play. The volcano plot in Fig. 4 illuminates a diverse array of ligands that are significantly associated with VF, each dot representing a unique cytokine or growth factor. The prominence of interferon alpha (IFNA) and gamma (IFNG), along with tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFA), underscores the role of inflammatory pathways in the pathogenesis of VF. These findings are corroborated by the bar plot, where stacked NES values are corrected for multiple comparisons using FDR, revealing the most significantly enriched signals within the VF PBMC landscape. Notably, the negative enrichment of growth factors like hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) aligns with the established knowledge that these molecules play pivotal roles in bone regeneration and repair. Their reduction in VF patients could reflect a mitigated bone remodeling process or a response to skeletal injury. In the network diagram, the intricate web of ligand interactions illustrates the complexity of signaling pathways activated in VF patients. It is apparent that no single ligand acts in isolation; rather, they partake in a tightly regulated communication network. For example, the central positioning of IFNG and IL1A suggests their potential as master regulators in the inflammatory milieu associated with VF. The chord diagram further accentuates the connections between these enriched ligands and various cellular components. This representation is particularly insightful, linking specific cytokines and growth factors to cellular structures such as the NF-κB complex, growth factor complex, and various interleukin complexes, thereby mapping the landscape of cellular machinery potentially involved in the disease process.

Association of CD4+ T cell-related gene sets with vertebral fractures: insights from EnrichR analysis

In our recent study, we utilized the EnrichR database to conduct an enrichment analysis of gene sets associated with CD4+ T cells in the context of patients with VF [26]. By analyzing “CellMarker2024” terms, we aimed to identify significant phenotypes of CD4+ T cell that are enriched in VF patients, thereby shedding light on the molecular and phenotypic underpinnings that may influence the occurrence of fractures in osteoporotic conditions. The analysis revealed a strong association of Naïve CD4+ T cell and Central memory CD4+ T cell markers with VF, as depicted in Fig. 2. Conversely, we found that Effector CD4+ T cells and Effector Memory T cells were significantly negatively enriched in VF patients. This suggests a tendency towards reduced T cell activation in the adaptive immune response of VF patients, indicating an altered immune landscape that may contribute to the pathophysiology of vertebral fractures in osteoporosis.

Comparative analysis of T cell differentiation pathways in VF

We employed the Elsevier pathway collection to investigate the differentiation patterns of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells in patients with VF. The Elsevier Pathway Collection is a comprehensive database of curated biological pathways, providing detailed insights into molecular and cellular processes across various biological systems. It includes information on signaling cascades, metabolic routes, and gene regulatory networks, which are invaluable for understanding complex biological interactions. Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells are subsets of CD4+ T helper cells that play crucial roles in orchestrating the immune response. Th1 cells are involved in cell-mediated immunity and produce cytokines like interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), which activate macrophages. Th2 cells support humoral immunity by aiding B cell differentiation and producing cytokines such as interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interleukin-5 (IL-5). Th17 cells produce interleukin-17 (IL-17) and are associated with pro-inflammatory responses and autoimmune diseases. The differentiation of these cells from naive T cells is influenced by specific cytokine environments and transcription factors. The GSEA provided the initial insights into the dynamics of T cell responses in VF (Fig. 6). Notably, “Th17 cell differentiation” “showed the highest Running Enrichment Score, indicating a dominant enrichment over Th1 and Th2 pathways. This finding is critical as it suggests that Th17 cells may play a more significant role in the pathophysiology of VF than previously recognized. Further analysis was presented through the NES barplot, which reinforced the prominence of Th17 differentiation with an NES of 1.804 and an FDR less than 0.001. The Ridge plot analysis depicted a more nuanced view, focusing on the fold changes of genes associated with Th17 differentiation. Heatmap analysis further delineated the expression differences of key cytokines and receptors, including IL2 and IL6, across the Th1, Th2, and Th17 differentiation pathways. Lastly, the Cnetplot provided a comprehensive visualization linking individual genes to their respective differentiation pathways. This plot not only confirmed the upregulation of critical genes such as IL6ST, IL6R, IL23A, IRF4, and IL1B in the Th17 pathway but also illustrated the interconnected nature of cytokine signaling and T cell differentiation.

Fig. 6.

Gene-set Enrichment Analysis of T Cell Differentiation in VF. The GSEA plot in the top left provides a visual representation of the cumulative distribution of gene sets for Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell differentiation, indicating the predominance of the Th17 pathway as evidenced by the highest Running Enrichment Score. Adjacent to this, the NES barplot in the top middle clearly quantifies the normalized enrichment scores and false discovery rate. The Ridge plot to the right illustrates the distribution of fold changes in gene expression within the T cell differentiation pathways. Below these, the heatmap on the bottom left details the differential expression of pivotal cytokines and receptors. The Cnetplot on the bottom right serves as a network graph that visually links individual genes to the three T cell differentiation pathways. The plot uses node size to represent gene expression levels and colored lines to depict association strength and pathway involvement

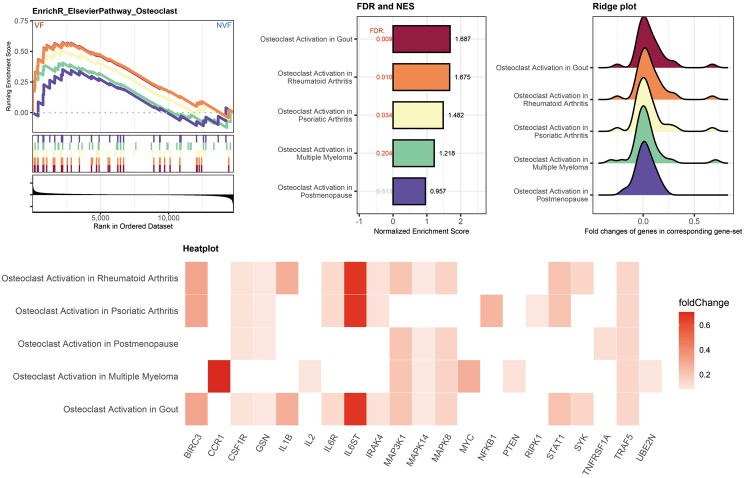

Validation of the enrichment of osteoclast activation associated gene sets in vertebral fracture patients

The intricate balance between bone formation and resorption is pivotal in maintaining skeletal integrity. Disruption of this balance is a hallmark of osteoporotic VF. To explore the impact of Th17 differentiation on osteoclast, we conducted a comprehensive enrichment analysis using the EnrichR database, focusing on gene sets related to series of gene-sets associated with osteoclasts activation (Fig. 7). Notably, the gene sets associated with gout, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriatic Arthritis showed positive NES, suggesting an upregulation of genes, especially IL6R, IL6ST, and IRK4, that promote the activation of osteoclasts in VF. This finding corroborates the notion that enhanced osteoclast activity, leading to increased bone resorption, is a critical factor in the development of osteoporotic fractures. On the contrary, the “Osteoclast Activation in Postmenopause” gene-set did not reach statistical significance, as indicated by an FDR > 0.25. This lack of significant enrichment implies that osteoclast activation in patients with VF may be predominantly induced by the immune system rather than primarily due to individual differences post-menopause. The enrichment of osteoclast-related gene sets in VF patients underscores the potential for targeting specific immune response as a therapeutic strategy.

Fig. 7.

GSEA depicting the enrichment analysis for gene sets related to osteoclast activation in VF patients. The GSEA plots trace the running sum of the enrichment score, marked by vertical lines indicating the position of genes within the ranked list. The NES barplot displays the NES for Elsevier pathways associated with osteoclast activation, comparing patients with vertebral fractures to those without. The ridge plot shows the distribution of fold changes of genes within the corresponding gene sets. The heatmap at the bottom illustrates specific genes that are differentially expressed in the context of osteoclast activation in different diseases, color-coded by the magnitude of their fold change between VF and NVF patients

Discussion

Our study reveals significant differences in immune and stromal cell profiles between osteoporotic patients with VF and those without (NVF). Figure 1 highlights an increased presence of higher abundance of CD4+ T cells in VF patients, suggesting distinct immunological environments. Figure 2 further examines immune cell subsets, showing elevated Tregs, CD4+ naïve T cells, and CD4+ central memory T cells in VF patients, indicative of ongoing adaptive immune responses. Figure 3 demonstrates the predictive power of our XGBoost model, with SHAP values identifying Th1 cells, CD4+ memory T-cells, and hematopoietic stem cells as key predictors of VF, in which patients with VF have lower Th1 cells proportion overall. Figures 4 and 5 explore cytokine and growth factor enrichment, revealing significant associations with inflammatory pathways and CD4+ T cell activation in VF patients. Figure 6 focuses on T cell differentiation, showing dominant Th17 cell pathway enrichment in VF and distinct IL6 associated gene expression, while Fig. 7 highlights an upregulation of osteoclast activation-related gene sets, emphasizing the immune system disrupted balance between bone formation and resorption in osteoporotic fractures.

Fig. 5.

Enrichment analysis outputs using the EnrichR database for gene sets associated with CD4 as the keyword in the context of VF patients. The GSEA plot (left) displays the ranking of gene sets across the dataset, highlighting significant enrichment of specific CD4+ T cell subsets in VF cases. The Normalized Enrichment Score (NES) bar plot (middle) further quantifies this enrichment, with bars representing the NES of different T cell subsets. FDR values less than 0.05 were marked in red. Adjacent to this, the ridge plot (right) illustrates the distribution of gene expression fold changes within each subset. Peaks towards the right suggest increased expression in VF, and peaks towards the left indicate increased expression in NVF. The heatplot (bottom) summarizes the fold change of key genes across CD4+ T cell subsets, using a color gradient from blue (decrease) to red (increase). Each cell in the heatmap corresponds to the fold change of a particular gene in a specific T cell subset, providing a concise overview of gene expression alterations associated with vertebral fractures

Osteoporosis is characterized by weakened bones and an increased risk of fractures, with recent research highlighting the interplay between the immune system and bone metabolism. Among the immune cells, T helper cells, particularly Th17 cells—which are a subset of CD4+ T cells known for producing interleukin-17 (IL-17) and playing a crucial role in inflammatory and autoimmune responses—play a significant role in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Th17 cells have been implicated in the regulation of bone loss due to estrogen deficiency, suggesting their specific involvement in osteoporosis [28]. Identified as a novel subset of Th cells, Th17 cells promote osteoclastogenesis—the process by which osteoclasts are formed and activated to break down bone tissue—and accelerate bone loss, particularly under inflammatory conditions, making them potential therapeutic targets for osteoporosis [29]. Furthermore, a significant negative correlation between bone mass and Th17 cell frequency has been observed, indicating that Th17 cells are associated with increased bone resorption in conditions such as primary sclerosing cholangitis [30]. Acting as osteoclastogenic helper T cells, Th17 cells link T cell activation to bone destruction. The IL-23-IL-17 axis is a critical immune signaling pathway where interleukin-23 (IL-23) stimulates the differentiation and proliferation of Th17 cells, leading to the production of interleukin-17 (IL-17) [31]. IL-17 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays a significant role in bone resorption and inflammation. This suggests that targeting the IL-23-IL-17 axis could be a viable therapeutic strategy for preventing bone loss in autoimmune diseases [32]. Immune cells, particularly various subsets of T cells, play significant roles in bone regeneration and fracture healing. The interaction between the immune system and bone repair mechanisms involves both positive and negative regulatory effects. γδ T cells produce IL-17 A, which promotes bone formation and accelerates fracture healing by stimulating the proliferation and differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells [33]. Fractures induce the expansion of callus γδ T cells and intestinal Th17 cells, improving fracture repair. The microbiome, particularly Th17 cell-inducing bacteria, is crucial for this process, suggesting that microbiome modifications could be a therapeutic strategy for fracture healing [34, 35]. T and B cells infiltrate the fracture callus in a two-wave fashion, indicating a regulatory role in the later stages of bone repair, particularly during callus mineralization [36, 37].

The interplay between Th17 cells and central memory T cells is crucial in immunological research, particularly concerning chronic diseases, autoimmune pathologies, and cancer immunotherapy. Th17 cells, a subset of proinflammatory T helper cells, play significant roles in inflammation and autoimmune diseases, as well as in antitumor immunity. Notably, human Th17 cells exhibit characteristics of long-lived effector memory T cells, displaying high proliferative self-renewal and resistance to apoptosis, suggesting their role as a persistent memory T cell population in chronic disease contexts [38]. Th17 cells can differentiate from FOXP3 + naive regulatory T cells, with IL-1RI expression on Tregs marking an early intermediate stage in this process, leading to a population that retains both proinflammatory and regulatory functions [39]. Additionally, Th17-derived memory cells maintain a stem-like molecular signature, indicative of a less mature state with enhanced survival and self-renewal capabilities, which may contribute to their efficacy in antitumor responses [40]. The development and plasticity of Th17 cells are influenced by various signaling pathways, including the Notch and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) pathways, which regulate antiapoptotic gene expression, and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, associated with a stem cell-like phenotype [38, 40, 41]. Furthermore, Th17 cells exhibit plasticity, with the potential to convert into other types of T helper cells, a feature that may be critical for their function in immune responses and memory formation [38, 42].

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and its signaling components, including the IL-6 receptor (IL6R) and the signal transducer IL6ST, play crucial roles in the regulation of bone metabolism and the pathogenesis of osteoporosis, especially in postmenopausal women. IL-6, along with its soluble receptor (sIL-6R), can either promote or suppress osteoclast differentiation induced by RANKL, depending on RANKL levels, suggesting a dual role for IL-6 in osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption [43]. Genetic variations in the promoter region of the IL6 gene, such as the IL6 -634G > C (rs1800796) polymorphism, have been associated with osteoporosis and lower bone mineral density (BMD) in postmenopausal women, indicating a genetic predisposition influenced by IL6 [44, 45]. Additionally, the IL6 G-174 C polymorphism (rs1800795) has been linked to lower BMD at the femoral neck and distal radius, with individuals possessing the C/C genotype exhibiting a reduced risk of developing osteoporosis, suggesting a protective effect against bone loss [46]. Furthermore, salivary IL6 levels have been proposed as a valid biomarker for the diagnosis of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women, with higher levels correlating with lower BMD and a higher prevalence of osteoporosis [47]. IRF4 is a central regulator in the development of T helper cells, particularly influencing the differentiation of both TH2 and TH17 cells, which are crucial in autoimmune and inflammatory responses [48]. Recent studies have expanded the understanding of IRF4’s roles beyond immune cell lineage decisions to skeletal health, demonstrating its involvement in ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis. Specifically, IRF4 contributes to bone instability by inhibiting the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells [49]. This dual functionality of IRF4, impacting both immune and bone cell lineages, suggests a complex regulatory network where inflammatory signals mediated by TH17 cells could intersect with bone metabolism pathways, potentially linking inflammatory conditions and bone density alterations. Such insights underscore the potential therapeutic targets within the IRF4 signaling pathways for conditions like osteoporosis and related inflammatory diseases.

These findings link specific immune pathways to the increased fracture risk observed in VF patients. The enrichment of Th17 cell pathways and elevated IL-6 expression suggest a shift toward a pro-inflammatory state that promotes osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. Th17 cells produce cytokines like IL-17, which are known to stimulate osteoclast activity and accelerate bone loss under inflammatory conditions. The lower proportion of Th1 cells in VF patients may further contribute to this imbalance, as Th1 cells are generally associated with protective immune responses. The upregulation of osteoclast activation-related genes underscores the direct impact of these immune alterations on bone density and strength. By connecting these pathways to our specific results, we highlight the mechanistic role of the immune system in osteoporotic fractures. The interplay between elevated Th17 cells, increased IL-6 levels, and enhanced osteoclast activity provides a comprehensive understanding of how immune dysregulation contributes to bone degradation in VF patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study identifies distinct immune profiles in osteoporotic patients with vertebral fractures, characterized by a higher abundance of Th17 cells, elevated IL-6 expression, and upregulated osteoclast-related genes. These immune changes are directly associated with increased bone resorption and fracture risk. For future research, these findings suggest investigating the therapeutic potential of targeting the Th17/IL-6 axis to prevent or mitigate fractures in osteoporosis. In clinical practice, assessing immune cell profiles could enhance fracture risk prediction and enable more personalized treatment strategies. For patient care, interventions that modulate the immune response may improve bone health outcomes, offering a novel avenue to reduce the incidence of fractures in osteoporotic patients.

Limitations

While our study provides valuable insights into the immunological differences between VF and NVF patients, it is important to acknowledge potential limitations. The sample size of 36 patients is relatively small, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. A larger cohort would strengthen the statistical power and provide more robust conclusions. Additionally, the study population is homogeneous, consisting of postmenopausal women aged between 73 and 91 years, all of whom are Latin American. This homogeneity, while reducing variability, may limit the applicability of the results to other populations with different demographics or ethnic backgrounds. Furthermore, direct verification of the xCell scores against actual cellular composition in clinical patients was not feasible, thereby restricting our ability to confirm the absolute accuracy of these infiltration estimates in vivo. Future studies with larger and more diverse cohorts, including the possibility of validating xCell-based predictions in clinical or histological samples, are needed to strengthen and extend these findings.

Abbreviations

- aDC

Activated dendritic cells

- AUC

Area Under the ROC Curve

- cDC

Conventional dendritic cells

- CLP

Common lymphoid progenitors

- CML

Chronic myeloid leukemia

- CMP

Common myeloid progenitors

- DC

Dendritic cells

- EO

Eosinophil

- ER

Erythrocytes

- ERP

Erythrocytes progenitors

- FDR

False discovery rate

- GMP

Granulocyte-macrophage progenitors

- GO

Gene Ontology

- GRAN

Granulocyte progenitors

- GSEA

Gene-set enrichment analysis

- HSC

Hematopoietic stem cells

- iDC

Immature dendritic cells

- LMPP

Lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors

- ly Endothelial cells

Lymphatic endothelial cells

- MCC

Matthews Correlation Coefficient

- MDP

Monocyte/dendritic cell progenitors

- MEP

Megakaryocyte–erythroid progenitors

- MK

Megakaryocyte

- MKP

Megakaryocyte progenitors

- MPP

Multi-potent progenitor

- MSC

Mesenchymal stem cells

- Multi-Lin

Multi-lineage progenitors

- mv Endothelial cells

Microvascular endothelial cells

- NES

Normalized enrichment score

- NK

Nature killer cells

- NKT

Nature killer T cell

- NVF

No vertebral fractures

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PC

Plasma cells

- pDC

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells

- ROC

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- SHAP

Shapley additive explanations

- Tcm

Central memory T-cells

- Tem

Effector memory T-cells

- Tregs

Regulatory T-cells

- VF

Vertebral fractures

Author contributions

J.-H. Chang and C.-H. Yu conceived the conception of this study. Y.-L. Chiu, S.-M. Huang, and Y.-C. Chen designed the methodology. Y.-L. Chiu and Y.-C. Chen developed the models and performed analysis. Y.-L. Chiu and H.-C. Su interpreted the results. All authors revised and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This study is partially supported by National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (R.O.C.) (NSTC-111-2314-B-016-019-MY3 to Y.-L. Chiu); Ministry of National Defense-Medical Affairs Bureau (MND-MAB-D-113140 to Y.-L. Chiu); Chi-Mei Medical Center (CMNDMC10905 and CMNDMC11001 to H.-C. Su); Cardinal Tien Hospital (CTH111AK-NDMC-2224 to J.-H. Chang); and Taoyuan General Hospital, Ministry of Health and Welfare (PTH111060 and PTH112056 to C.-H. Yu).

Data availability

The dataset employed in this investigation was derived from the study conducted by Neto et al., as cited in https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mgg3.1391.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yi-Chou Chen and Hui-Chen Su contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ching-Hsiao Yu, Email: smalloil1205@yahoo.com.tw.

Jen-Huei Chang, Email: ortchang@gmail.com.

Yi-Lin Chiu, Email: yilin1107@mail.ndmctsgh.edu.tw.

References

- 1.Kim DH, Vaccaro AR. Osteoporotic compression fractures of the spine; current options and considerations for treatment. Spine J. 2006;6(5):479–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eastell R, et al. Classification of vertebral fractures. J Bone Min Res. 1991;6(3):207–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Homminga J, et al. The osteoporotic vertebral structure is well adapted to the loads of daily life, but not to infrequent error loads. Bone. 2004;34(3):510–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grigoryan M, et al. Recognizing and reporting osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Eur Spine J. 2003;12(Suppl 2):S104–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Genant HK, Jergas M. Assessment of prevalent and incident vertebral fractures in osteoporosis research. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(Suppl 3):S43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riggs BL, Melton LJ 3rd, and, O’Fallon WM. Drug therapy for vertebral fractures in osteoporosis: evidence that decreases in bone turnover and increases in bone mass both determine antifracture efficacy. Bone. 1996;18(3 Suppl):s197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fechtenbaum J, et al. The severity of vertebral fractures and health-related quality of life in osteoporotic postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(12):2175–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanfélix-Genovés J, et al. The population-based prevalence of osteoporotic vertebral fracture and densitometric osteoporosis in postmenopausal women over 50 in Valencia, Spain (the FRAVO study). Bone. 2010;47(3):610–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan PA, Orton DF, Asleson RJ. Osteoporosis with vertebral compression fractures, retropulsed fragments, and neurologic compromise. Radiology. 1987;165(2):533–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang G, et al. Vertebral fractures in the elderly may not always be osteoporotic. Bone. 2010;47(1):111–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baht GS, Vi L, Alman BA. The role of the Immune cells in Fracture Healing. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2018;16(2):138–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oropallo MA, et al. Chronic spinal cord injury impairs primary antibody responses but spares existing humoral immunity in mice. J Immunol. 2012;188(11):5257–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo TZ, et al. Sex differences in the temporal development of pronociceptive immune responses in the tibia fracture mouse model. Pain. 2019;160(9):2013–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haffner-Luntzer M, et al. Altered early immune response after fracture and traumatic brain injury. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1074207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehnert S, et al. Effects of immune cells on mesenchymal stem cells during fracture healing. World J Stem Cells. 2021;13(11):1667–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charles JF, Aliprantis AO. Osteoclasts: more than ‘bone eaters’. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20(8):449–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyce BF. Advances in the regulation of osteoclasts and osteoclast functions. J Dent Res. 2013;92(10):860–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyce BF, et al. New roles for osteoclasts in bone. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1116:245–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nam D, et al. T-lymphocytes enable osteoblast maturation via IL-17F during the early phase of fracture repair. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e40044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yasuda H, et al. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(7):3597–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber A, Chan PMB, Wen C. Do immune cells lead the way in subchondral bone disturbance in osteoarthritis? Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2019;148:21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jales Neto LH, et al. Overexpression of SNTG2, TRAF3IP2, and ITGA6 transcripts is associated with osteoporotic vertebral fracture in elderly women from community. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020;8(9):e1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen T, Guestrin C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 2016;785-94.

- 24.Evangelista JE, et al. SigCom LINCS: data and metadata search engine for a million gene expression signatures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(W1):W697–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szklarczyk D, et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D638–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen EY, et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aran D, Hu Z, Butte AJ. xCell: digitally portraying the tissue cellular heterogeneity landscape. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao R. Immune regulation of bone loss by Th17 cells in oestrogen-deficient osteoporosis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013;43:1195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng-Lai Y, et al. Type 17 T-helper cells might be a promising therapeutic target for osteoporosis. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;39:771–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt T, et al. Th17 cell frequency is associated with low bone mass in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2019;70 5:941–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kikly K, et al. The IL-23/Th(17) axis: therapeutic targets for autoimmune inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18(6):670–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kojiro S, et al. Th17 functions as an osteoclastogenic helper T cell subset that links T cell activation and bone destruction. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2673–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ono T et al. IL-17-producing γδ T cells enhance bone regeneration. Nat Commun. 2016;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Aurora R, Matthew JS. T cells heal bone fractures with help from the gut microbiome. J Clin Invest. 2023;133(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Hamid YD, et al. Callus γδ T cells and microbial-induced intestinal Th17 cells improve fracture healing in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation; 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Khassawna TE, et al. T lymphocytes influence the mineralization process of bone. Front Immunol. 2017;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Könnecke I, et al. T and B cells participate in bone repair by infiltrating the fracture callus in a two-wave fashion. Bone. 2014;64:155–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ilona K, et al. Human TH17 cells are long-lived Effector Memory cells. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:104–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caroline R, et al. Ex vivo IL-1 receptor type I expression in human CD4 + T cells identifies an early Intermediate in the differentiation of Th17 from FOXP3 + Naive Regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:5196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muranski P, et al. Th17-Derived memory cells are long-lived and retain a stem-like Molecular signature. Blood. 2010;116:1018–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Majchrzak K et al. β-catenin and PI3Kδ inhibition expands precursor Th17 cells with heightened stemness and antitumor activity. JCI Insight. 2017;2(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Muranski P, Restifo N. Essentials of Th17 cell commitment and plasticity. Blood. 2013;121 13:2402–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feng W et al. Combination of IL-6 and sIL-6R differentially regulate varying levels of RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis through NF-κB, ERK and JNK signaling pathways. Sci Rep. 2017;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Giampietro P, et al. The role of cigarette smoking and statins in the development of postmenopausal osteoporosis: a pilot study utilizing the Marshfield Clinic Personalized Medicine Cohort. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:467–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ota N, et al. A nucleotide variant in the promoter region of the interleukin-6 gene associated with decreased bone mineral density. J Hum Genet. 2001;46:267–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ni Y, et al. Association of IL-6 G-174 C polymorphism with bone mineral density. J Bone Miner Metab. 2014;32:167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jabber WF, et al. Salivary interleukin 6 is a valid biomarker for diagnosis of osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women. Chem Mater Res. 2015;7:65–9. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brüstle A, et al. The development of inflammatory TH-17 cells requires interferon-regulatory factor 4. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(9):958–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu X, et al. Interferon Regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) plays a key role in osteoblast differentiation of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2024;29(3):115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Here we describe the dataset utilized in this study, sourced from the research conducted by Neto et al. [22]. The dataset comprises a cohort of 36 postmenopausal women diagnosed with osteoporosis, aged between 73 and 91 years with a median age of 82. All participants are of Latin American ethnicity, indicating a high degree of homogeneity among the patients. Among these women, 24 have experienced vertebral fractures (VF), while the remaining 12 exhibit no such fractures (NVF). After downloading the dataset, we conducted an ID conversion to standardize gene identifiers across different databases. The log₂-transformed expression values were reverted back to their original scale. The data were then organized into a matrix format suitable for computational processing. The Immune Oncology Biological Research (IOBR) package (v0.99.8) in R (v4.3.3) was utilized for implementing x-Cell signature scoring. The single sample gene-set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) based x-Cell signature scores were computed based on a reference panel of gene signatures associated with specific cell types, including various immune and stromal cells. For data visualization, we generated heatmaps and boxplots using ComplexHeatmap (v2.18.0) and ggplot2 (v3.5.1) packages. The cell types were categorized into five major categories according to the xCell signature’s original classification: Lymphoids, Myeloids, Stromals, Stem cells, and Others. The Lymphoid category was further subdivided into Innate and Adaptive immune responses. Within the Adaptive subcategory, further distinction was made among B cell lineage, CD4 T cell lineage, and CD8 T cell lineage. The Innate subcategory was subdivided into Monocyte lineage and Dendritic cell lineage. The Stromal category specifically isolated endothelial cells as a distinct group.

The dataset employed in this investigation was derived from the study conducted by Neto et al., as cited in https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mgg3.1391.