Abstract

Background

Subchondral bone cysts (SBCs) can significantly impact the outcomes of cartilage repair procedures such as autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI). However, the etiology and progression of SBCs following ACI remain poorly understood. This case report highlights a progressively enlarging SBC following ACI using all-suture anchors, treated with autologous osteochondral transplantation (AOT).

Case presentation

A 58-year-old female with progressive right knee pain, varus alignment, and Kellgren-Lawrence grade 3 osteoarthritis underwent atelocollagen-associated ACI combined with medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy. Longitudinal radiological assessment revealed bone hole enlargement corresponding to all-suture anchor sites, with one hole continuing to expand up to 15 months postoperatively, reaching a size of 11 × 13 × 13 mm. This expanding SBC exhibited a connection to the joint cavity via a tiny fissure, scant osteosclerotic rim on CT, and fluid intensity on MRI. Histological analysis of tissue obtained during subsequent AOT revealed several findings. The SBC was located at the anterior portion of the medial femoral condyle, just beneath the all-suture anchor. Osteochondral necrosis was observed surrounding the anchor site, with no evidence of foreign body reaction. The cyst was filled with a mucoid substance and featured an aggregation of foamy macrophages. A sclerotic wall indicative of a strain response was observed. Notably, the presence of osteoclasts along the adjacent bone surface indicated ongoing bone resorption. The patient underwent AOT, which resulted in confirmed bone union. Postoperative follow-up demonstrated successful integration of the osteochondral graft and improved knee function scores over three years.

Conclusion

This case report documents SBC formation following knee surgery with all-suture anchors and provides histological evaluation of such a cyst. The observed histological findings may contribute to our understanding of SBC pathophysiology in the context of cartilage repair procedures. This case underscores the importance of secure suturing techniques in high-stress areas and suggests the potential benefit of extended post-operative monitoring of SBC progression beyond one year. These observations may inform future strategies for the early detection of SBC formation and its progression, as well as timely intervention to prevent further joint damage in similar cases, though further research is needed to establish broader clinical implications.

Keywords: Subchondral bone cyst, Autologous chondrocyte implantation, All-suture anchor, Longitudinal radiological assessment, Histological evaluation, Autologous osteochondral transplantation

Introduction

Subchondral bone has garnered attention for its significant biological and biomechanical impacts on its overlying articular cartilage, including autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) [1–4]. Subchondral bone cysts (SBCs), commonly observed with the progression of osteoarthritis (OA), are increasingly recognized as complications after cartilage repair procedures, affecting clinical outcomes [5, 6].

The clinical prevalence of SBCs following ACI ranges from 14.7 to 38.8% [1, 3, 7]. In sheep models, where more detailed examinations are possible, researchers have observed a 92.0% incidence of SBCs at six months after cartilage repair procedure [8]. Despite this high prevalence, the etiology and natural history of SBCs following ACI remain unclear, which could be addressed by histological and longitudinal assessments. However, SBCs following ACI are mainly evaluated using computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at specific time points rather than through longitudinal studies, with limited histological evaluations.

Recent reports indicate that SBCs also occur around the suture anchors in shoulder surgeries, such as rotator cuff repair and Bankart repair [9, 10]. Histological evaluation of peri-anchor cysts in the shoulder has been performed in only one animal study, revealing cyst formation exceeding the anchor size itself [11]. Despite the increasing use of suture anchor in knee surgeries, such as meniscal repair, the occurrence and histological characteristics of SBCs following the use of suture anchors in knee surgeries remain uninvestigated.

Herein, we report a rare case of a progressively enlarging SBC following ACI with all-suture anchors in the knee, subsequently underwent autologous osteochondral transplantation (AOT) and accompanied by longitudinal radiological and detailed histological evaluations.

Case presentation

Patient information and preoperative plan

A 58-year-old female (weight, 85 kg; height, 158 cm; body mass index, 34.0 kg/m2) presented with progressive right knee pain exacerbated by walking. Despite conservative management, including oral analgesics and intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections, her symptoms progressively deteriorated, leading to her referral to our facility. Physical examination revealed knee effusion, medial joint line tenderness, and a reduced knee flexion angle of 120°.

Plain radiographs showed a varus deformity consistent with Kellgren-Lawrence grade 3 right knee osteoarthritis (Fig. 1). Alignment measurement of the affected lower extremity revealed a Hip-knee-ankle (HKA) angle of -2.8°, anatomical femoro-tibial angle (aFTA) of 178.2°, % mechanical axis (%MA) of 33.7%, a mechanical lateral distal femoral angle (mLDFA) of 87.0° and a medial proximal tibial angle (MPTA) of 84.4°. MRI identified a large chondral defect on the medial femoral condyle (MFC) and mild degeneration of the medial meniscus without ligamentous injuries (Fig. 2). The chondral lesion measured 30 × 15 mm.

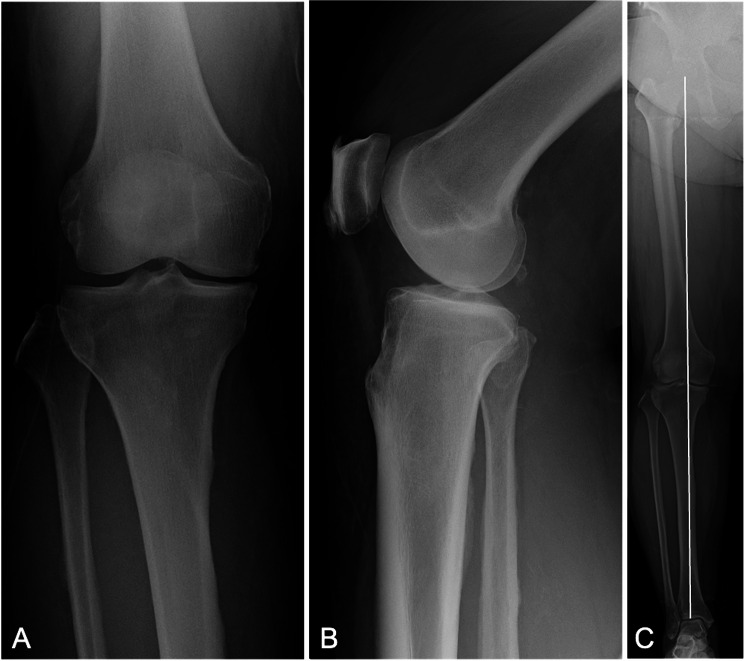

Fig. 1.

Preoperative anteroposterior (A), lateral (B), and full-leg length standing (C) radiographs of the right knee. The white line represents the mechanical axis, which shows a varus alignment

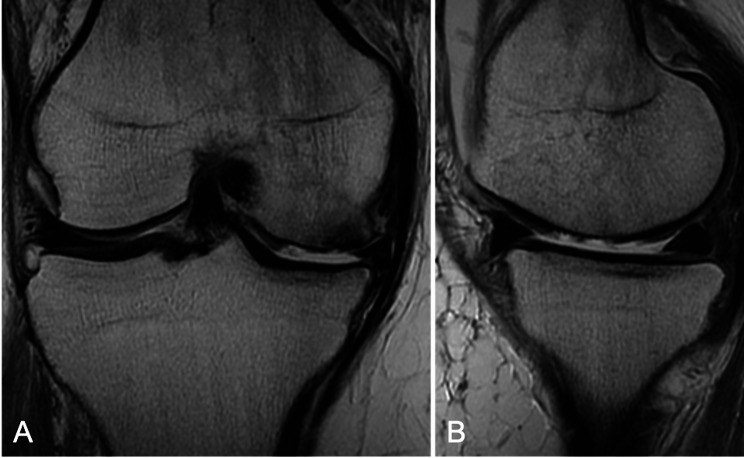

Fig. 2.

Coronal (A) and sagittal (B) T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the affected knee demonstrating a large chondral defect on the medial femoral condyle

Given the large chondral lesion and tibial varus alignment, we addressed the chondral defect on the MFC with ACI in conjunction with a medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy (MOWHTO). The selected ACI was Atelocollagen-associated ACI (A-ACI), which is the only insurance-approved ACI treatment in our country.

Operative procedure: autologous chondrocyte implantation and medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy

The A-ACI procedure has been detailed in prior studies [12, 13]. Initially, an arthroscopic evaluation of the chondral lesion was performed following the harvesting of approximately 0.4 g of healthy cartilage (Fig. 3A). The cartilage cells were isolated and cultured within atelocollagen gel in a three-dimensional manner for four weeks at a dedicated facility (Japan Tissue Engineering Co., Ltd., Gamagori, Japan). The surface of the surrounded cartilage was smooth but exhibited soft indentation (International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) grade 1). The medial meniscus showed mild degenerative changes with fibrillation in the middle segment. Additionally, a bone spur was observed on the medial aspect of the MFC.

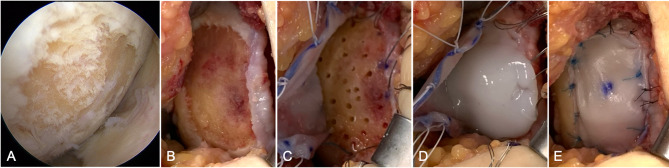

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative images of an atelocollagen-associated autologous chondrocyte implantation. (A) Arthroscopic view of the chondral lesion in the medial femoral condyle. (B) Exposed and debrided chondral lesion until normal surrounding tissue appeared. (C) Drilling of the sclerotic subchondral bone and suturing of the collagen membrane to the surrounding normal cartilage. (D) Application of atelocollagen gels encapsulating cultivated chondrocytes onto the lesion. (E) Suturing of the collagen membrane with all-suture anchors and 5 − 0 nylon sutures

Four weeks after the cartilage harvest, MOWHTO and A-ACI were performed concurrently. First, MOWHTO was carried out with a procedure of distal tibial tuberosity arc osteotomy with the application of a medial locking plate (TriS Medial HTO Plate System, Olympus Terumo Biomaterials, Tokyo, Japan) with a correction angle of 8 degrees [14]. The tibial valgus correction angle was calculated using the approach described by Miniaci et al. [15], which utilizes a full-length standing anteroposterior radiograph of the lower extremity. The correction angle was determined to aim for a postoperative %MA of 66%, which aligns with the Fujisawa point, because sufficient valgus correction is needed to obtain excellent 10-year results [16–18]. Second, the chondral lesion was completely exposed through an arthrotomy and debrided peripherally until stable and healthy surrounding cartilage was observed (Fig. 3B). The cartilage defect size was 30 × 15 mm. The sclerotic subchondral bone was thoroughly excised and perforated using a 1.5 mm Kirschner wire (Fig. 3C). For bone marrow stimulation, we performed 24 perforations to a depth of 6 mm. The atelocollagen gels encapsulating cultured chondrocytes were then positioned over the defect and secured with a porcine-derived type I/III collagen membrane (Chondro-Gide, Geistlich Biomaterials, Wolhusen, Switzerland) (Fig. 3D). Suture fixation of the collagen membrane was primarily performed using the pull-out technique with 2 − 0 braided polyester sutures (Wayolax, Matsuda Ika Kogyo Company, Tokyo, Japan). A total of ten all-suture anchors (Jugger knot soft anchor 1.0 mm, Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, Indiana, USA) were additionally employed circumferentially. The remaining unsecured portions of the collagen membrane were sutured with 5 − 0 nylon to prevent leakage of the implanted cartilage (Fig. 3E).

Postoperative course after autologous chondrocyte implantation and medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy

After two weeks of knee immobilization, continuous passive motion exercises were initiated. Partial weight-bearing was begun at six weeks, progressing to full weight-bearing (FWB) at eight weeks. A functional knee brace was used for three months.

Postoperative plain radiographs confirmed knee alignment correction from varus to valgus. HKA angle, aFTA, %MA, and MPTA were corrected to 2.9°, 172.8°, 66.7%, and 91.6°, respectively (Fig. 4). The functional knee score and Lysholm score showed improvement at 15 months postoperatively. The Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score improved from 55 preoperatively to 80 points, while the Lysholm score improved from 64 preoperatively to 81 points. The Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) also demonstrated improvement in all subscales. Symptoms improved from 54 preoperatively to 82.1, Pain from 52 to 77.8, Activities of Daily Living (ADL) from 65 to 89.7, Function in Sport and Recreation (Sports/Rec) from 20 to 35.0, and Knee-related Quality of Life (QOL) from 40 to 68.8. Serial follow-up CT and MRI scans, performed at 1, 2, 5, 9, 15 months and 1, 3, 5, 9, 12 months postoperatively, in CT and MRI, respectively, revealed a time-dependent expansion of the bone holes at the A-ACI implantation site (Figs. 5 and 6). The locations of the enlarging bone holes corresponded topographically to one of the all-suture anchors. Nine of bone holes stabilized in size by one year postoperatively; however, one bone hole in the anteromedial portion of the MFC continued to expand and became spherical in shape, subsequently designated as an SBC. It merged with adjacent bone holes, reaching 11 × 13 × 13 mm at 15 months postoperatively. The characteristics of this expanding SBC were a tenuous connection to the joint cavity and less peri-cystic bone density increase on CT compared to the stable bone holes. MRI characterization of the expanding SBC showed T2 hyperintensity. The progressive enlargement of the SBC was the primary indication for the revision surgery, as it posed a risk of impairing the integration of the transplanted cartilage and could lead to fracture and collapse of the subchondral bone, as noted in the literature by Gao et al. [1]. Despite the patient being asymptomatic at the time of the revision, the enlarging SBC, indicative of necrotic changes that occurred without any traumatic episode, was addressed with AOT during the removal of the HTO locking plate.

Fig. 4.

Postoperative anteroposterior (A), lateral (B), and full-leg length standing (C) radiographs of the right knee. The white line represents the mechanical axis, which shows a corrected alignment from varus to valgus

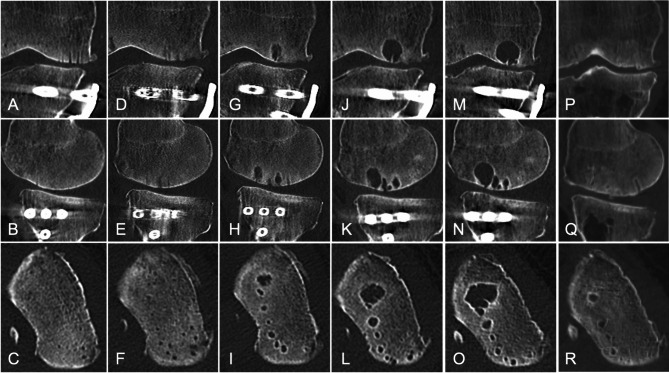

Fig. 5.

Computed tomography scans showing time-dependent enlargement of the cyst at the autologous chondrocyte implantation site. Coronal (A, D, G, J, M), sagittal (B, E, H, K, N), and axial (C, F, I, L, O) images. Postoperative at 1 month (A-C), 2 months (D-F), 5 months (G-I), 9 months (J-L), and 15 months (M-O). Postoperative images after autologous osteochondral transplantation at 12 months (P-R)

Fig. 6.

Magnetic resonance images showing a time-dependent enlargement of the subchondral bone cyst at the autologous chondrocyte implantation site. Coronal (A, E, I, M, Q, U), sagittal (B, F, J, N, R, V), and axial (C, D, G, H, K, L, O, P, S, T, W, X) images. Postoperative at 1 month (A-D), 3 months (E-H), 5 months (I-L), 9 months (M-P), and 12 months (Q-T). Postoperative after autologous osteochondral transplantation at 2 years (U-X)

Operative procedure and histological evaluation: autologous osteochondral transplantation

Following the removal of the locking plate, an assessment arthroscopy and arthrotomy were performed utilizing the pre-existing incision. The chondral lesion, previously addressed with A-ACI, was nearly fully resurfaced with cartilage-like tissue (Fig. 7A, B). The implanted tissue conformed well to the native condylar curvature, integrating into the surrounding cartilage with slight disruption. The surface of the implanted tissue was smooth and white, resembling native cartilage in stiffness. The area of the SBC was not visibly detectable but could be palpated as a softened region. An autologous osteochondral graft was harvested using a 10 mm diameter Osteochondral Autograft Transfer System (OATS; Arthrex, Inc., Naples, Florida) from the lateral femoral condyle and transplanted into the SBC site (Fig. 7C). The joint fluid was collected during the revision surgery, and culture results were negative for any infection.

Fig. 7.

Intraoperative images of autologous osteochondral transplantation for a subchondral bone cyst after autologous chondrocyte implantation. (A) Arthroscopic evaluation showing the implanted tissue similar in color and hardness to surrounding healthy cartilage. (B) Well-integrated implanted tissue into surrounding cartilage tissue with slight disruption. (C) Performance of autologous osteochondral transplantation at the site of the subchondral bone cyst

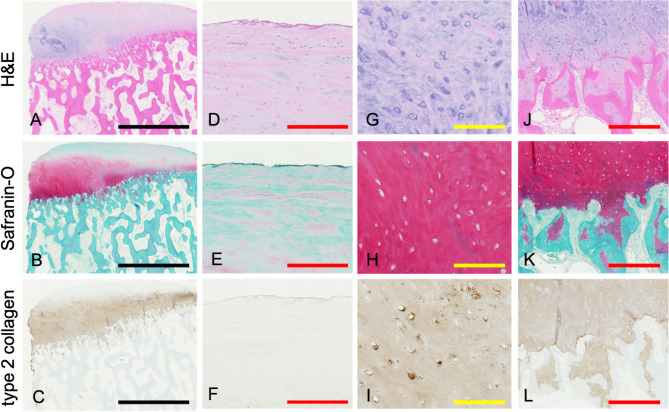

Histological and immunohistological assessments of the implanted tissue obtained during AOT confirmed the presence of cartilage-like tissue (Fig. 8). The tissue sections were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and stained with H&E for general structure and Safranin-O for proteoglycan content. Type II collagen was detected using a purified mouse monoclonal antibody to human type II collagen (F-57, Kyowa Pharma Chemical, Toyama, Japan) following proteinase K antigen retrieval, and the tissue stained positive for both Safranin-O and type II collagen, showing significant integration into the subchondral bone (Fig. 8). Paraffin-embedded sections of the cystic lesion revealed the presence of polyethylene anchors located just above the SBC (Fig. 9A). Evaluation under polarized light microscopy confirmed the presence of these polyethylene anchors, consistent with those observed in paraffin-embedded sections. However, these anchors were absent within the cyst and peri-cystic tissue (Fig. 9B, C). The superficial tissue surrounding the anchor exhibited chondrocyte depletion and empty bone lacunae, indicative of osteochondral necrosis (Fig. 9D). The tissue surrounding the anchor at the subchondral bone consisted of fibrous tissue without multinucleated giant cells, indicating an absence of a foreign body inflammatory response (Fig. 9E).

Fig. 8.

Histological and immunohistological evaluation of regenerative tissue. (A-C) Low-power magnification showing H&E staining (A), Safranin-O staining (B), and type II collagen immunostaining (C). Higher magnification images of the superficial zone (D-F), intermediate zone (G-I), and subchondral zone (J-L), with H&E staining (D, G, J), Safranin-O staining (E, H, K), and type II collagen immunostaining (F, I, L). The cartilage-like tissue showed positive staining for both Safranin-O and type II collagen, with good integration into the subchondral bone. The black bar represents 2500 μm, red bar 250 μm, and yellow bar 100 μm

Fig. 9.

Histological evaluations at the all-suture anchor site and subchondral bone cyst. (A) Macroscopic view with paraffin block. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining. (C) Polarized light microscopy. The tissue around the all-suture anchors at the border between cartilage and subchondral bone (D) and at subchondral bone (E). (F) The sclerotic cyst wall without a synovial lining. (G) Foamy histiocytes and active osteoclasts (black arrows) at the cyst wall. The black bar represents 500 μm, and yellow bar 100 μm

Osteosclerotic changes were evident in the trabecular bone surrounding the cyst, characterized by a thickening of the trabecular bone in a lamellar pattern (Fig. 9F). The cyst was devoid of synovial lining cells (Fig. 9F), which is analogous to what is observed in osteoarthritic SBCs. Additionally, the cyst was filled with a mucoid substance and featured an aggregation of foamy macrophages (Fig. 9G). The presence of osteoclasts along the adjacent bone surface was indicative of ongoing bone resorption (Fig. 9G).

Post operative course after autologous osteochondral transplantation

Range of motion exercise began immediately post-surgery. FWB was permitted one week postoperatively. Postoperative CT and MRI confirmed a well-integrated autologous osteochondral graft (Figs. 5P, Q and R and 6U, V, W and X). The Magnetic Resonance Observation of Cartilage Repair Tissue (MOCART) 2.0 scoring system evaluated the grafts at 3, 12, and 36 months after ACI, yielding scores of 45, 70, and 80 points, respectively [19]. At three years post-ACI, the JOA score further improved to 85 points, and the Lysholm score to 88 points. The KOOS continued to improve: Symptoms reached 82 points, Pain 92 points, ADL 93 points, Sports/Rec 50 points, and QOL 94 points.

Discussion

This case report describes a 58-year-old female with progressive enlargement of bone holes, culminating in an SBC following ACI for a large chondral lesion. Radiologic findings showed that the expanding bone holes were localized at the site of all-suture anchors used for collagen membrane fixation. Histological examination revealed osteochondral necrosis adjacent to the all-suture anchor, with the SBC located directly beneath it.

For cases with moderate unicompartmental osteoarthritis and large focal cartilage defects, the main treatment options are cartilage repair procedures alone, HTO alone, combined cartilage repair with HTO, unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA), or total knee arthroplasty (TKA). While UKA and TKA can provide good clinical outcomes, we did not select this option due to the increased risk of revision surgery in younger active patients and the patient’s preference to avoid arthroplasty [20]. Given the focal nature of the cartilage lesion, a cartilage repair procedure was deemed appropriate. Among cartilage repair procedures (including microfracture, allograft transplantation, autograft transplantation, and ACI), we selected ACI because it has demonstrated superior clinical outcomes for defects larger than 4 cm² [21]. Although allograft transplantation could be considered, it is not available in our country. In cases with osteoarthritic changes, ACI combined with HTO has shown better clinical outcomes and lower reoperation rates compared to cartilage repair alone [22]. Previous studies have demonstrated that ACI can be effective even in patients with early osteoarthritis, with one study showing that 92% of patients were able to delay joint replacement at 5 years postoperatively [23]. However, we recognize that the degree of osteoarthritis in this case may have exceeded the optimal window for cartilage repair procedures.

The choice of ACI over AOT in this case was primarily guided by two key factors. First, the patient’s chondral lesion measured 4.5 cm² (30 × 15 mm), which exceeds the size threshold where AOT is typically recommended [21]. AOT is considered suitable for lesions smaller than 2–4 cm², while ACI has shown superior outcomes for larger defects due to its ability to address extensive areas with regenerative tissue [21]. Second, AOT would require multiple osteochondral plugs to achieve full coverage, which poses a risk of significant donor site morbidity. To avoid compromising the patient’s remaining joint integrity, ACI was preferred as it does not involve harvesting cartilage from weight-bearing areas, making it a more conservative and sustainable option for addressing large cartilage defects.

The development pattern for most of the bone holes in our case aligns with previous reports [9, 10, 24]. A previous study on cartilage repair procedure revealed that SBCs were not detectable at three weeks postoperatively but were confirmed at 12 and 24 months [24]. Similarly, peri-anchor cysts associated with all-suture anchors in glenoid labral repair have been reported to enlarge during the first year postoperatively and then stabilize in size [9, 10]. In our case, most bone holes followed this pattern and ceased to expand midway through the postoperative period, while 10% (1/10) of bone holes continued to enlarge and progressed to form SBCs. This enlarging SBC was characterized by its connection to the joint cavity with a tiny fissure and scant osteosclerotic rim as observed on CT, with fluid intensity on MRI. Pressurized joint fluid is known to be a key factor in SBC formation, and a sclerotic rim is typically observed once the growth ceases [25]. These findings highlight the necessity for careful monitoring of such radiological features of bone holes post-ACI, due to the potential risk of their enlargement beyond the typical stabilization period.

A biomechanical study suggests that all-suture anchors are weaker than solid anchors, potentially leading to higher micromotion [11]. Peri-anchor cysts in glenoid repair were larger when anchors were inserted at the anteroinferior and posterior aspects of the glenoid, where load stress is high [9, 10]. These reports suggest that peri-anchor cyst enlargement is influenced by the type of suture anchor used and site-specific loading patterns. Finite element analysis in the knee highlighted high shear and compressive stress on the anteromedial side of the subchondral bone of the MFC, corresponding to the site of the SBC in our case. These observations underline the necessity for secure suturing techniques, especially in high-stress areas, to minimize the risk of SBC formation and enlargement [26].

Histologically, the SBC in our case was located at the anterior portion of the MFC, just beneath the all-suture anchor. There was no evidence of a foreign body reaction, often associated with suture debris and the use of absorbable anchors [27, 28]. Instead, the osteochondral necrosis surrounding the suture anchor is postulated to be caused by mechanical stress from micromotion of the suture anchor rather than an immune reaction. The sclerotic wall of the SBC is indicative of a strain response, as observed in animal models [11]. The presence of histiocytes within the SBC suggested an immune response for debris removal [29]. Furthermore, osteoclast activity and bone resorption at the wall of the SBC supported the evidence of its ongoing expansion [1].

The pathogenesis of SBCs remains not fully elucidated [1]. Two prevailing theories attempt to explain the SBC formation. The internal theory postulates that synovial fluid infiltrates the subchondral bone through a fissure. The external theory suggests that bone contusions lead to microfractures in the subchondral bone, resulting in inflammation. We propose that the SBC formation in this case resulted from multiple factors: pre-existing osteoarthritis, microfractures, and all-suture anchor usage. Our radiological and histological findings support this multi-factorial pathogenesis: the presence of a tiny fissure connecting to the joint cavity suggests synovial fluid infiltration (internal theory), while the observed osteochondral necrosis around the anchor sites indicates mechanical stress-induced damage (external theory). The combination of these factors likely created a pathway for synovial fluid infiltration while simultaneously weakening the subchondral bone structure. Specifically, all-suture anchors inserted into the MFC of an OA knee in a high-stress area led to micromotion and microdamage to the implanted tissue and subchondral bone. This mechanical instability resulted in osteochondral necrosis and subchondral bone resorption, facilitating further synovial fluid intrusion and inflammation. Regarding the rationale for performing microfractures, while ACI is indeed typically chosen to avoid subchondral bone damage, some degree of calcified cartilage removal and subchondral perforation is performed to allow the ingrowth of bone marrow-derived cells, which has been shown to improve cartilage repair tissue integration [30]. However, we acknowledge that our aggressive approach to subchondral preparation (24 perforations to a depth of 6 mm) combined with the use of 10 all-suture anchors may have created excessive subchondral damage in the degenerative intra-articular environment, which may contribute to SBC formation.

Bone holes with fluid-like intensity on MRI and lacking a sclerotic rim on CT have the potential to continue expanding beyond the typical stabilization period of one year [25]. The clinical impact of subchondral bone cysts has been linked to alterations in the structural support for weightbearing, potentially undermining joint biomechanics and leading to cartilage degeneration, subchondral collapse, and fracture, as reported by Gao et al. [1]. Additionally, McCarthy et al. [3] demonstrated that the presence of SBCs is significantly associated with worse clinical outcomes. Therefore, although the patient was relatively asymptomatic in this case, we performed AOT procedure to SBCs.

There are some limitations in this study. First, as this is a single case report, our findings cannot be generalized to establish causality between all-suture anchors and SBC formation. Second, the use of anchors is not standard in most published ACI studies. Third, although we conducted regular radiological follow-up, the optimal timing and frequency of imaging studies for detecting and monitoring SBC progression remains to be established. Fourth, ACI is generally indicated for well-defined focal cartilage lesions rather than for cases with generalized structural alterations or advanced joint degeneration. Considering the patient’s age and osteoarthritic condition, this case may not be ideal for ACI. Finally, we cannot definitively separate the relative contributions of multiple factors to the development and progression of the SBC in this case, including the osteoarthritic environment, microfracture procedure, and all-suture anchors.

In conclusion, longitudinal radiological assessment and histological analysis reveal a complex interplay of internal and external factors in SBC formation after A-ACI using all-suture anchors in this degenerative intra-articular environment. Our findings emphasize the necessity for secure suturing techniques in high-stress areas to minimize the risk of SBC formation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Howard Tarnoff for proofreading this article.

Abbreviations

- SBC

Subchondral Bone Cyst

- ACI

Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation

- OA

Osteoarthritis

- CT

Computed Tomography

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- AOT

Autologous Osteochondral Transplantation

- HKA

Hip-Knee-Ankle angle

- aFTA

anatomical Femoro-Tibial Angle

- %MA

Percent Mechanical Axis

- mLDFA

mechanical Lateral Distal Femoral Angle

- MPTA

Medial Proximal Tibial Angle

- MFC

Medial Femoral Condyle

- MOWHTO

Medial Opening Wedge High Tibial Osteotomy

- A-ACI

Atelocollagen-associated Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation

- FWB

Full Weight-Bearing

- OATS

Osteochondral Autograft Transfer System

- MOCART

Magnetic Resonance Observation of Cartilage Repair Tissue

- KOOS

Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score

Author contributions

TK and EK was involved in the design of the study, performed the clinical assessment, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted and revised the manuscript. TK and MM were involved in the design of the study, assisted with data interpretation, and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. KI, TO, DM, and NI were involved in the design of the study and the data acquisition and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. ZT and ST were involved in the histological assessment. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data in this case report are not publicly available because it contains information that may violate patient privacy, but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case report was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gao L, Cucchiarini M, Madry H. Cyst formation in the subchondral bone following cartilage repair. Clin Transl Med. 2020;10(8):e248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madry H, van Dijk CN, Mueller-Gerbl M. The basic science of the subchondral bone. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(4):419–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarthy HS, McCall IW, Williams JM, Mennan C, Dugard MN, Richardson JB, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Parameters at 1 year correlate with clinical outcomes up to 17 years after autologous chondrocyte implantation. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(8):2325967118788280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merkely G, Ogura T, Bryant T, Minas T. Severe bone marrow Edema among patients who underwent prior marrow stimulation technique is a significant predictor of graft failure after autologous chondrocyte implantation. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(8):1874–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaspiris A, Hadjimichael AC, Lianou I, Iliopoulos ID, Ntourantonis D, Melissaridou D, et al. Subchondral bone Cyst Development in Osteoarthritis: from pathophysiology to bone microarchitecture changes and clinical implementations. J Clin Med. 2023;12(3):815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanal HT, Chen L, Haghighi P, Trudell DJ, Resnick DL. Carpal bone cysts: MRI, gross pathology, and histology correlation in cadavers. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2014;20(6):503–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasiliadis HS, Danielson B, Ljungberg M, McKeon B, Lindahl A, Peterson L. Autologous chondrocyte implantation in cartilage lesions of the knee: long-term evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging and delayed gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging technique. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(5):943–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck A, Murphy DJ, Carey-Smith R, Wood DJ, Zheng MH. Treatment of articular cartilage defects with microfracture and Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis leads to extensive subchondral bone cyst formation in a Sheep Model. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(10):2629–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JH, Kang JS, Park I, Shin SJ. Serial changes in Perianchor cysts following arthroscopic Labral Repair using all-suture anchors. Clin Orthop Surg. 2021;13(2):229–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milewski MD, Diduch DR, Hart JM, Tompkins M, Ma SY, Gaskin CM. Bone replacement of fast-absorbing biocomposite anchors in arthroscopic shoulder labral repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(6):1392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfeiffer FM, Smith MJ, Cook JL, Kuroki K. The histologic and biomechanical response of two commercially available small glenoid anchors for use in labral repairs. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2014;23(8):1156–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaibara T, Kondo E, Matsuoka M, Iwasaki K, Onodera T, Momma D, et al. Large osteochondral defect in the lateral femoral condyle reconstructed by Atelocollagen-associated autologous chondrocyte implantation combined with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaibara T, Kondo E, Matsuoka M, Iwasaki K, Onodera T, Sakamoto K et al. Atelocollagen-associated autologous chondrocyte implantation for the repair of large cartilage defects of the knee: results at three to seven years. J Orthop Sci. 2024;29(1):207-216. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Akiyama T, Osano K, Mizu-Uchi H, Nakamura N, Okazaki K, Nakayama H, et al. Distal tibial Tuberosity Arc Osteotomy in Open-Wedge Proximal Tibial Osteotomy to Prevent Patella Infra. Arthrosc Tech. 2019;8(6):e655–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miniaci A, Ballmer FT, Ballmer PM, Jakob RP. Proximal tibial osteotomy. A new fixation device. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;246:250–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naudie D, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, Bourne TJ. The install award. Survivorship of the high tibial valgus osteotomy. A 10- to -22-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;367:18–27. [PubMed]

- 17.Yasuda K, Majima T, Tsuchida T, Kaneda K. A ten- to 15-year follow-up observation of high tibial osteotomy in medial compartment osteoarthrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;282:186–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rinonapoli E, Mancini GB, Corvaglia A, Musiello S. Tibial osteotomy for varus gonarthrosis. A 10- to 21-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;353:185–93. [PubMed]

- 19.Schreiner MM, Raudner M, Marlovits S, Bohndorf K, Weber M, Zalaudek M et al. The MOCART (Magnetic Resonance Observation of Cartilage Repair Tissue) 2.0 knee score and Atlas. Cartilage. 2021;13(1_suppl):571S-587S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Hang JR, Stanford TE, Graves SE, Davidson DC, de Steiger RN, Miller LN. Outcome of revision of unicompartmental knee replacement. Acta Orthop. 2010;81(1):95–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richter DL, Schenck RC Jr, Wascher DC, Treme G. Knee articular cartilage repair and restoration techniques: a review of the literature. Sports Health. 2016;8(2):153–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhillon J, Kraeutler MJ, Fasulo SM, Belk JW, Mulcahey MK, Scillia AJ, et al. Cartilage repair of the Tibiofemoral Joint with Versus without Concomitant Osteotomy: a systematic review of clinical outcomes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2023;11(3):23259671231151707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minas T, Gomoll AH, Solhpour S, Rosenberger R, Probst C, Bryant T. Autologous chondrocyte implantation for joint preservation in patients with early osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):147–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cole BJ, Farr J, Winalski CS, Hosea T, Richmond J, Mandelbaum B, et al. Outcomes after a single-stage procedure for cell-based cartilage repair: a prospective clinical safety trial with 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1170–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox LG, Lagemaat MW, van Donkelaar CC, van Rietbergen B, Reilingh ML, Blankevoort L, et al. The role of pressurized fluid in subchondral bone cyst growth. Bone. 2011;49(4):762–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang K, Li L, Yang L, Shi J, Zhu L, Liang H et al. The biomechanical changes of load distribution with longitudinal tears of meniscal horns on knee joint: a finite element analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Lovric V, Goldberg MJ, Heuberer PR, Oliver RA, Stone D, Laky B et al. Suture wear particles cause a significant inflammatory response in a murine synovial airpouch model. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Ruiz Ibán MA, Vega Rodriguez R, Ruiz Díaz R, Pérez Expósito R, Zarcos Paredes I, Diaz Heredia J. Arthroscopic remplissage with all-suture anchors causes cystic lesions in the humerus: a volumetric CT study of 55 anchors. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(7):2342–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bejarano PA, Aranda-Michel J, Fenoglio-Preiser C. Histochemical and immunohistochemical characterization of foamy histiocytes (muciphages and xanthelasma) of the rectum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(7):1009–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seow D, Yasui Y, Hutchinson ID, Hurley ET, Shimozono Y, Kennedy JG. The subchondral bone is affected by bone marrow stimulation: a systematic review of Preclinical Animal studies. Cartilage. 2019;10(1):70–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this case report are not publicly available because it contains information that may violate patient privacy, but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.