Abstract

Background

Cotinus coggygria has a long history of use in traditional medicine in Europe and Asia. The aim of study was to explore the cytotoxicity of extracts (EE-ethanol, MME-methylene chloride/methanol, and WE-water) and compounds (butin, butein, fisetin, sulfuretin, taxifolin, eriodictyol, fustin, cotinignan A, sulfuretin auronol, 3-O-methylepifustin, 3-O-methylfustin, and sitosterol-3-O-β-D-glucoside) isolated from C. coggygria. Mechanisms of anticancer effects of three extracts, butin, butein, and sulfuretin were examined.

Methods

Compounds were isolated from the EE using silica gel column chromatography and semipreparative HPLC. Structure elucidation was performed using NMR spectroscopy. Cytotoxicity was evaluated using MTT assay. The effects on cell cycle and cell death were investigated by flow cytometry. The antimigration effects were examined by scratch assay, while expression of the MMP2, MMP9, and VEGFA were measured by quantitative real time PCR. The antioxidant effects were examined by flow cytometry.

Results

3-O-methylepifustin, epitaxifolin, and sulfuretin auronol were found for the first time in C. coggygria. The extracts and compounds showed selective cytotoxicity against HeLa, MDA-MB-231, HL-60, K562, A375, PC-3, and DU 145 cells. HeLa cells were the most sensitive to the cytotoxicity of MME (IC50 value of 47.45 µg/mL), while leukemia K562 and HL-60 cells were the most sensitive to the MME and EE (IC50 values in the range from 31.04 to 44.57 µg/mL). Butein exerted strong cytotoxicity on HeLa, K562, and MDA-MB-231 cells (IC50 values of 8.66 µM, 13.91 µM, and 22.36 µM). EE, butin, butein, sulfuretin, and fisetin were highly selective against leukemia K562 cells when compared with normal fibroblasts MRC-5 (selectivity index: 4.01, 5.15, 6.17, 7.05, > 4.41, respectively). Butein and fisetin showed high selectivity in the cytotoxic activity against HeLa cells when compared with MRC-5 cells (selectivity index: 9.91 and > 6.61). Three extracts, butin, butein, and sulfuretin, initiated apoptosis in HeLa cells by activating caspase-8 and caspase-9. The extracts, butin, butein, and sulfuretin inhibited HeLa cell migration. EE, MME, butein, and sulfuretin exerted cytoprotective effects in normal fibroblasts.

Conclusions

This research might suggest promising anticancer effects and underscores the need for additional research on C. coggygria extracts and compounds to assess their potential in cancer prevention and therapy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12906-025-04768-3.

Keywords: Cotinus coggygria, Cytotoxic activity, Proapoptotic effects, Antimigration effects, Cytotoprotective properties

Background

The plant family Anacardiaceae comprises approximately 60–74 genera, encompassing approximately 400–600 species [1]. The family exhibits very high species diversity, including shrubs, woody forms, vines, and occasionally perennial plants [1]. Cotinus coggygria (European smoke tree) is one of the two species belonging to the genus Cotinus, the family Anacardiaceae [1]. The plant is widely distributed in Southern Europe and the Mediterranean, from Moldova to the Caucasus, as well as in the central China and at the Himalayas [2].

In the traditional medicine, smoke tree has been utilized in the treatment of hypertension and heart disorders, diabetes, wound healing, liver diseases, periodontal disease, stomatitis, gingivitis, gastric/duodenal ulcers, gastritis, hemorrhoid symptoms, throat inflammation, cough, increased immunity, as a local antipyretic, for urinary infections, skin disorders, and eye diseases [3–11]. C. coggygria represents one of the medicinal plants recognized in the traditional Turkish folk medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, Bulgarian phytotherapy, local folk medicine of the southwestern Romania, and Serbian traditional medicine [3–11].

Plants and natural products have been used in traditional medicine for centuries to treat various diseases, including malignant diseases in numerous regions around the world. The plant remedies often have fewer adverse effects than synthetic compounds, which can sometimes pose greater risks through their potential side effects than the intended conditions they are meant to treat [12]. Plants serve as inexhaustible reservoirs for a diverse range of bioactive phytochemicals including phenolic compounds, terpenoids, nitrogen-containing compounds, vitamins, and other secondary metabolites. Numerous plant compounds show anticancer, antioxidative, and antigenotoxic effects, both in vitro and in vivo [13–15].

The most important biological and pharmacological properties of the smoke tree and its essential oils and extracts include antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, anticancer, antigenotoxic, hepatoprotective, and anti-inflammatory effects, as reviewed by Matić et al. 2016 [3]. The biologically active compounds identified in the extracts from different parts of the smoke tree include flavonoids, phenolic acids, and tannins [3 and references cited therein]. In Serbian folk medicine, cancer has also been treated using a decoction prepared from the bark of the smoke tree [16, 17].

In this study cytotoxic activity of the three C. coggygria heartwood extracts and the main compounds from the ethanol extract was investigated. From the ethanol extract of C. coggygria twelve main compounds were isolated and their structure elucidated on the basis of 1D and 2D NMR, IR, UV, and polarimetry. Three of them: 3-O-methylepifustin, epitaxifolin, and sulfuretin auronol were found for the first time in C. coggygria. Auronolignan cotinignan A was added from the previous investigation to explore cytotoxic activity against new cell lines. The mechanisms of anticancer effects of three extracts and selected compounds butin, butein, and sulfuretin were further examined in human cervical adenocarcinoma HeLa cells. The effects of extracts and selected compounds on intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species were investigated in normal human fibroblasts MRC-5.

Methods

General experimental procedures

For the experimental work of isolation and structure elucidation the same equipment and chemicals were used as described by Novaković et al. [18]. The only difference was that NMR spectra were obtained on two instruments; besides Bruker Avance III 500 (500 MHz for 1H; 125 MHz for 13C), a Varian 400/54 Premium Shielded spectrometer (400 MHz for 1H; 100 MHz for 13C) was used.

Plant material and extraction

The C. coggygria heartwood was collected at Deliblatska Pescara (Deliblato Sand), Vojvodina province, Serbia, in July 2018. Plant material was identified by Prof. Milan Veljić, Faculty of Biology, University of Belgrade, and voucher specimen BEOU 17422 was deposited at the Herbarium of the Institute of Botany and Botanical Garden “Jevremovac”, Belgrade, Serbia. C. coggygria Scop. is not endangered plant species and no permission was necessary to collect plant material. The heartwood was air-dried and milled to fine powder. Wood powder, 200.0 g, was extracted three times with 3 L of 96% ethanol for 24 h (1st h of extraction in ultrasonic bath) at room temperature to give 18.0 g of crude extract which was subjected to fractionation by Si gel CC. Methylene chloride/methanol (1:1) extract (MME) was prepared by triple extraction in the same way like the ethanol extract (EE): 20 g of wood powder was extracted 3 times with 300 mL of CH2Cl2/MeOH (1:1) and after filtration extracts were combined and evaporated on a rotavapor. The yield was 8.6%. The water extract (WE) was prepared in a form of herbal tea, 20 g of wood powder was boiled in 300 mL of water for 15 min and after filtration WE was evaporated on a rotavapor under reduced pressure at 40 °C. The yield was 6.4%.

Isolation and identification of compounds 1–12

Similar to our previous work [18] the crude EE (10.0 g) was chromatographed on a Si gel CC column (750 × 45 mm), with CH2Cl2/MeOH (gradient elution - from 95/5 to 60/40) and 250 fractions were obtained. Column chromatography was monitored by TLC, and the fractions with similar Rf values were combined: 1–10, 11–18, 19–25, 26–30, 30–38, 39–41, 42–50, 51–60, 61–70, 71–82, 83–96, 97–111, 112–130, 131–152, 153–180. Fractions 1–10, 30–38 and 61–70 were used for the isolation of flavonoid compounds by reversed phase semipreparative HPLC. All isolated compounds were identified using 1H, 13C, COSY, NOESY, HSQC and HMBC NMR spectra and by comparison of their spectral data with those from the literature. Butin (1) [18–20], 3-O-methylfustin (3) [18, 21], 3-O-methylepifustin (4), eriodictyol (5) [18, 20], and butein (9) [18–20] were isolated from combined fractions 1–10 by semipreparative HPLC using following method: 0–20 min, 20–37% B; 20–21 min, 37–50% B; 21–22 min, 50% B; and 23–30 min, 50–100% B. Solvent A was 0.2% HCOOH, solvent B was MeCN, temperature was 40 °C, flow rate was 4 mL/min and detection wavelengths were 254 and 280 nm.

Fustin (2) [18–21], taxifolin (6) [18, 19, 21], epitaxifolin (7), fisetin (8) [18, 19, 21], sulfuretin (10) [18–22] were isolated from fractions 30–38 by semipreparative HPLC using another, faster method: 0–20 min, 25–40% B, 20–24 min, 40–100% B, where and solvent A was 0.2% HCOOH, solvent B was MeCN, temperature was 40 °C, flow rate was 4 mL/min and detection wavelengths were 254 and 280 nm. Separation of taxifolin and epitaxifolin required different HPLC method since their peaks were slightly overlapped. Their separation was performed using following HPLC method: 0–20 min, 5–30% B, 20–21 min, 30–100% B where solvent B was MeCN and solvent A was 0.2% HCOOH. Temperature was 40 °C, flow rate was 4 mL/min and detection wavelengths were 254 and 280 nm.

Fustin (2), taxifolin (6), fisetin (8), sulfuretin (10) and sulfuretin auronol (2-benzyl-2,6,3’,4’-tetrahydroxycoumaran-3-one, 11) were isolated from fractions 61–70 using following HPLC method: 0–20 min, 25–40% B; 20–24 min, 40–100% B, where solvent B was MeCN and solvent A was 0.2% HCOOH. Temperature was 40 °C, flow rate was 4 mL/min and detection wavelengths were 254 and 280 nm. Compound 3-O-β-D-sitosterol glucoside (12) was isolated from this fraction as a precipitate in pure MeOH, since it was poorly soluble in MeOH and completely dissolved in mixture methylene chloride/methanol.

Reagents for cell culture experiments

All chemicals used in the cell culture experiments were obtained from Sigma Aldrich unless stated otherwise. Thermo Scientific™ Biolite™ 96-well, 6-well cell culture plates and 25cm2 cell culture flasks were used for each experiment, unless specified otherwise.

In vitro cytotoxic activity

The cytotoxic activity of three extracts (EE, MME, WE) and 12 compounds (1–6 and 8–13) isolated from the C. coggygria heartwood was evaluated against seven human malignant cell lines after a 72 h exposure: cervical adenocarcinoma HeLa (2000 cells per well), malignant melanoma A375 (3000 cells per well), triple-negative breast adenocarcinoma MDA-MB-231 (5000 cells per well), prostate carcinoma DU 145 (5000 cells per well), prostate adenocarcinoma PC-3 (5000 cells per well), chronic myelogenous leukemia K562 (5000 cells per well), and acute promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells (7000 cells per well). Among all isolated compounds, cytotoxic activity of epitaxifolin (7) was not investigated due to the small amount of the isolated compound. The intensity of cytotoxic activity was also determined against two normal human cell lines, keratinocytes HaCaT (7000 cells per well) and lung fibroblasts MRC-5 (5000 cells per well). The cell lines were acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Dried extracts and compounds were solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide at concentration of 20 mg/mL for extracts and 20 mM for compounds. The five concentrations used for the treatment were: extracts (12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 µg/mL), and compounds (12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 µM or 400 µM). Following a 72 h incubation period, 10 µL of MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dyphenyl tetrazolium bromide) solution (5 mg/mL) was dispensed into the wells of the 96-well microtiter plates. After 4 h, 100 µL of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was added. The used MTT protocol was firstly established by Mosmann [23], modified by Ohno and Abe [24], and described by Matić et al. [25]. The absorbance was read at 570 nm using a Thermo Scientific™ Multiskan SkyHigh microplate spectrophotometer. Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate. Cisplatin was used in the experiments as a positive control.

Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle phase distribution analysis was performed on HeLa cells using flow cytometry [25, 26]. After 24 h of seeding, HeLa cells (200000 cells per well) were treated with two concentrations (IC50 and 2IC50) of three extracts (MME, EE, and WE) and three compounds (butin (1), butein (9), and sulfuretin (10)) isolated from C. coggygria. Control cells were grown in cell culture medium only. Following a 24 h and 48 h incubation, the cells were collected by trypsinization, washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed in cold 70% ethanol on ice. The cells were stored at -20 °C for a minimum duration of one week. In brief, the cell samples were washed, and PBS containing RNase A was added. Following 30 min incubation at 37 °C, the solution of propidium iodide was added, and the cells were incubated for 10 min before analysis. A total of 10000 cells were collected within the designated gate for each cell sample using a BD FACSCalibur™ flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The data obtained were subjected to analysis using BD CellQuest™ Pro software. Three independent experiments were performed.

Identification of target caspases

Specific peptide cell-permeable caspase inhibitors, Z-DEVD-FMK, a caspase-3 inhibitor, Z-IETD-FMK, a caspase-8 inhibitor, and Z-LEHD-FMK, a caspase-9 inhibitor (R&D Systems), were used to examine the potential activation of caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9. HeLa cells (200000 cells per well) were pretreated with caspase inhibitors (concentration of 40 µM) 2 h prior to treatment [25, 27] and afterwards treated with 2IC50 concentrations of the three compounds (butin (1), butein (9), and sulfuretin (10)) and three extracts (EE, WE, and MME) and incubated for 24 h. Following 24 h incubation, the cells were collected by trypsinization and handled further in accordance with the protocol for the cell cycle flow cytometric analysis, described in previous section.

FITC annexin V-propidium iodide staining flow cytometric assay

HeLa cells (200000 cells per well of the 6-well plate) were treated with 2IC50 concentrations of the examined extracts and compounds. Following a 24 h incubation, the cells were collected by trypsinization. After washing the cell suspension, 100 µL of annexin V binding buffer was added to the cell suspension. Subsequently, 5 µL of annexin V-FITC and 10 µL of propidium iodide were administered in dark. The cells were incubated for 15 min in the dark. Following the incubation period, an additional 400 µL of annexin V binding buffer was added before flow cytometric analysis. FITC annexin V and annexin V binding buffer were purchased from BD Pharmingen (catalog number 556419 and 556454, respectively). The recommended assay procedure is provided by BD Pharmingen for FITC annexin V product.

Gene expression analysis

HeLa cells (1 × 106 cells per 25 cm2 cell culture flask) were treated with IC50 concentrations of the extract or compound during 24 h. Total ribonucleic acid was extracted using TriReagent following the manufacturer’s protocol. The concentrations and A260/280 nm ratios were subsequently determined using BiospecNano (Shimadzu Corporation, Japan). Reverse transcription and RT-qPCR amplification were performed according to previously described protocol [27]. Amplification targeting MMP2 (Hs01548727_m1), MMP9 (Hs00957562_m1), VEGFA (Hs00900055_m1), and GAPDH (Hs02758991_g1) were used as the reference gene. Quantification of VEGFA, MMP2, and MMP9 gene expression was conducted using the QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems™). Data analysis was performed using the comparative delta delta threshold cycle (ddCt) method, calibrated to the untreated control sample and gene expression levels are reported in relative quantity units (RQ) [27].

In vitro scratch assay

HeLa cells (70000 cells per well) were seeded in 24-well plates reaching confluence after 24 h. Afterwards, a scratch consistent width along the well was made in the HeLa monolayer using a 200 µL pipette tip held at a 90-degree angle when making the scratch [28]. The cells were washed, the fresh medium was added to the control wells, and IC50/2 concentrations of the respective extracts or compounds were added to the rest of the wells. The cells were photographed at 0, 24, and 48 h using inverted phase contrast Olympus microscope. The ImageJ.js version for Browser was used for scratch assay image analysis and measuring of the desired area of the wound/scratch made in the confluent layer of HeLa cells. Percentage of wound remaining was set at 100% for time point of 0 h.

Measurement of intracellular reactive oxygen species levels

The intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in control MRC-5 cells and those treated with non-toxic concentrations (IC50/4 determined after 72 h incubation by MTT assay) of the three extracts and three compounds were evaluated. This assessment was conducted using flow cytometry to measure the fluorescence of the cell-permeable dye using 2′,7′ - dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA). In brief, MRC-5 cells (250 000 cells per well) were treated with three extracts and three compounds for 24 h. The subsequent day, the cells were collected, washed, stained with 30 µM DCFH-DA, and subjected to analysis according to protocol described in more detail by Mihailović et al. [29].

To investigate antioxidant effects of the extracts and selected compounds, the influence of 24 h pretreatment of MRC-5 cells with IC50/4 concentrations of the extracts and compounds on the generation of ROS caused by brief exposure to hydrogen peroxide was investigated. Control and treated MRC-5 cells were incubated with DCFH-DA, and subsequently the cells were exposed to 5 mM H2O2 for 15 min to induce oxidative stress.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed independently three times. The IC50 values are presented as average plus/minus standard deviation of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. For each extract and compound, the selectivity index was calculated using average IC50 values.

Statistical analysis was performed by first determining the normality of the distribution of the three biological replicates in each experiment (independent experiments or biological replicates, each containing control and treatment samples). Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test or Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, with Q-Q plots used for visual confirmation. Data were considered normally distributed if p > 0.05 and significantly deviated from normality if p ≤ 0.05. Levene’s test was used to assess the homogeneity of variance across groups. If the variances were equal (p > 0.05), a standard unpaired t-test assuming equal variances was performed. If the variances were unequal, a t-test with Welch’s correction was applied. For datasets deviating from normality, the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the medians between groups. The significance level (p-value) was set at 0.05 for all tests.

Results

Extracts and compounds isolated from Cotinus coggygria

Isolated compounds have been presented on Fig. 1. NMR spectra of all isolated compounds have been given in Supplementary Material (Figures S1-S75) including NMR spectra of compound 13 cotinignan A (Figures S76-S85) not isolated in this work, but added from the previous investigation in order to check its cytotoxic activity. The majority of the isolated compounds were flavonoids, except compound 12, a triterpene saccharide. Structural characteristic of the isolated flavonoids is the presence of catechol moiety in all of them in ring B and 7-OH in ring A, as well, suggesting the same biosynthetical origin [30]. Isolated compounds 1–12, are already known and their NMR data were in agreement with the literature, except for 3-O-methylepifustin (6). For this compound NMR data were not found and we here report its complete NMR analysis. Compounds 1–5, 8–11 and 13, were already known compounds from C. coggygria [18]. Most of them, i.e.2, 5, 8–12 are the known secondary metabolites from related Rhus species like Rhus verniciflua (syn. Toxicodendron vernicifluum) [31], while 3-O-methylepifustin (4), epitaxifolin (7) and sulfuretin auronol (11) isolated in this work were known compounds, but found for the first time in C. coggygria.

Fig. 1.

Compounds isolated from ethanol extract of Cotinus coggygria heartwood

Compound 3-O-methylepifustin (4) was reported in a single reference so far as a constituent of Trachylobium verrucosum (Gaertn.) Oliv. [32]. Complete spectral data, above all, NMR data, have not been reported so far, except the coupling constant between vicinal H-2 and H-3 that was J2,3=2.0 Hz [32]. Hence, this is the first time that 3-O-methylepifustin is completely chemically characterized and all NMR spectra are given in Supplementary Material (Supplementary Material, Figures S31-S37). In the 1H NMR spectrum of 4 the pattern of the aromatic signals was the same and chemical shifts were very similar to those in known 3-O-methylfustin (3) [18, 21], (Supplementary Material, Figures S31 and S13). The main difference was observed in the aliphatic region; instead of the two doublets of H-2 and H-3 protons at δH 5.07 and 4.17, respectively, with the characteristic coupling constant J2,3 = 10.4 Hz for the trans disposition, in the 1H NMR spectrum of 4, two doublets at δH 5.32 and 3.74 with the characteristic coupling constant J2,3 = 1.2 Hz indicated cis disposition H-2/H-3 (Supplementary Material, Figures S31 and S13). Compounds 3 and 4 exhibited very similar 13C NMR spectra (Figures S32 and S14) and all remaining NMR data were in accordance with the structure of 3-O-methylepifustin (4) (Supplementary Material, Figures S31-S37). Polarymetric analyses revealed that 3-O-methylepifustin (4) isolated in this work was levorotatory or (-) isomer, [αD]22 was − 3.0, similar to fustin (2) ([αD]22 = -30.0) and 3-O-methylfustin (3) ([αD]22 = -51.0).

Epitaxifolin (7) was found for the first time in C. coggygria. Its NMR data (Supplementary Material, Figures S38-S43) are in accordance with the literature [33]. Due to the insufficient isolated amount of this compound, epitaxifolin was not investigated for its cytotoxic activity.

Sulfuretin auronol (11) is already known as a constituent of Rhus vernicifluum and many plant species. R. vernicifluum is taxonomically close to C. coggygria since genus Cotinus belonged earlier to genus Rhus, but later was excluded from the genus. Additionally, R. vernicifluum is chemically very similar with C. coggygria. Our NMR data (Supplementary Material, Figure S70-S75) fit well with the literature data [31].

Chemical composition of extracts

According to the HPLC-DAD analyses of ethanolic extract, the main compounds were: fustin (22.1% ± 0.8%), sulfuretin (14.4% ± 0.4%), butin (9.3% ± 0.4%), fisetin (5.0% ± 0.4%), taxifolin (2.0% ± 0.3%), and butein (0.8% ± 0.3%). In the methylene chloride/methanol (1:1) extract the main compounds were fustin (19.2% ± 0.8%), sulfuretin (12.4% ± 0.5%), butin (8.9% ± 0.5%), fisetin (5.3% ± 0.4%), taxifolin (1.8% ± 0.3%), and butein (1.1% ± 0.3%). In the water extract of C. coggygria, the main compounds were: fustin at 24.8% ± 1.0%, butin at 6.3% ± 0.5%, sulfuretin at 3.4% ± 0.6%, and taxifolin at 1.7% ± 0.3%.

Cytotoxic effects of C. coggygria extracts and isolated compounds

Ethanol (EE), methylene chloride/methanol (1:1) (MME), and water (boiled) (WE) heartwood extracts from C. coggygria, and 12 compounds isolated from the ethanol extract showed concentration-dependent cytotoxicity against seven human malignant cell lines: HeLa, MDA-MB-231, HL-60, K562, A375, PC-3, and DU 145. These results are presented in Table 1. EE, MME, and WE exerted cytotoxic activities against all tested malignant cell lines, with IC50 concentrations ranging from 31.04 to 168.59 µg/mL for EE, from 33.74 to 160.92 µg/mL for MME, and from 51.05 to 184.72 µg/mL for WE. The sensitivities of MDA-MB-231 and HeLa malignant cell lines to the effects of EE were nearly identical.

Table 1.

In vitro cytotoxic activity of the extracts and compounds isolated from Cotinus coggygria

| Compound Extract |

HeLa | MDA-MB-231 | HL-60 | K562 | A375 | DU 145 | PC-3 | HaCaT | MRC-5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50[µg/mL for extracts and µM for compounds]average ± SD | |||||||||

| EE | 73.57 ± 3.16 | 72.54 ± 7.80 | 31.04 ± 4.30 | 34.84 ± 4.24 | 67.95 ± 2.67 | 168.59 ± 9.43 | 96.65 ± 1.02 | 122.43 ± 0.56 | 139.85 ± 13.56 |

| WE | 75.48 ± 5.54 | 117.35 ± 7.26 | 51.05 ± 7.51 | 89.72 ± 5.98 | 135.13 ± 3.38 | 184.72 ± 4.98 | 115.11 ± 6.39 | 125.67 ± 3.40 | 179.73 ± 15.37 |

| MME | 47.45 ± 3.23 | 67.50 ± 8.03 | 33.74 ± 2.86 | 44.57 ± 5.91 | 72.45 ± 5.49 | 160.92 ± 16.03 | 83.53 ± 0.83 | 123.71 ± 6.76 | 131.43 ± 11.58 |

| (1) butin | 44.48 ± 5.16 | 104.10 ± 2.03 | 28.76 ± 4.35 | 19.67 ± 2.49 | 89.09 ± 2.10 | 186.03 ± 24.19 | 195.57 ± 0.77 | 72.12 ± 2.19 | 101.31 ± 16.03 |

| (2) fustin | > 400 | 178.59 ± 19.68 | > 200 | 155.30 ± 3.46 | 186.59 ± 11.66 | > 400 | > 400 | > 400 | > 400 |

| (3) 3- O -methylfustin | NA | 201.26 ± 1.80 ** | NA | 74.38 ± 9.40 ** | 338.19 * | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| (4) 3- O -methylepifustin | NA | 193.34 * | NA | 47.71 * | 345.08 * | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| (5) eriodictyol | 147.03 ± 17.45 | 51.32 ± 6.40 | 116.97 ± 15.07 | 125.61 ± 8.11 | 137.92 ± 6.65 | 387.69 ± 15.95 | 283.98 ± 7.54 | 172.04 ± 6.81 | 154.93 ± 7.48 |

| (6) taxifolin | 195.19 ± 2.84 | 174.12 ± 20.36 | 187.20 ± 14.49 | 166.66 ± 10.90 | 190.52 ± 5.54 | > 400 | 390.72 ± 16.07 | 391.40 ± 14.89 | > 400 |

| (8) fisetin | 60.47 ± 11.11 | 45.05 ± 7.60 | 42.79 ± 3.07 | 90.78 ± 2.73 | 161.20 ± 5.91 | > 400 | 159.74 ± 14.41 | 79.40 ± 6.03 | > 400 |

| (9) butein | 8.66 ± 1.10 | 22.36 ± 2.60 | 41.14 ± 2.32 | 13.91 ± 2.61 | 39.14 ± 6.86 | 90.52 ± 4.74 | 48.61 ± 1.24 | 36.47 ± 3.46 | 85.78 ± 8.90 |

| (10) sulfuretin | 78.76 ± 9.66 | 54.63 ± 5.71 | 36.24 ± 4.69 | 21.94 ± 3.42 | 69.03 ± 9.91 | 265.50 ± 10.08 | 116.00 ± 5.94 | 126.09 ± 3.02 | 154.69 ± 10.24 |

| (11) sulfuretin auronol | > 400 | > 400 | 42.50 ± 6.70 | 129.24 ± 5.42 | > 400 | > 400 | > 400 | > 400 | > 400 |

| (12) 3- O - β -D-sitosterol glucoside | > 200 ** | 333.33 * | NA | > 200 ** | > 200 * | > 400 ** | > 400 ** | 104.41* | > 400** |

| (13) cotinignan A | 54.73 ± 9.44 | NA | NA | 19.04 ± 3.79 | NA | 75.04 ± 2.87 | 76.37 ± 14.58 | NA | 63.19 ± 3.68 |

| cisplatin | 1.37 ± 0.15 | 20.59 ± 0.52 | 1.60 ± 0.30 | 9.70 ± 0.70 | 2.30 ± 0.48 | 6.72 ± 0.05 | 5.75 ± 0.16 | 2.86 ± 0.21 | 6.37 ± 0.20 |

Compound 7 was not investigated due to low amount

*The determination of this value is based on a single independent experiment due to low amount

**The determination of this value is based on two independent experiments due to low amount

Among 12 isolated compounds, butein (9) exerted the strongest cytotoxic activity against all examined malignant cell lines, with IC50 values ranging from 8.66 µM on HeLa cells to 90.52 µM on DU 145 cells (Table 1). Notably, butein (9) cytotoxicity was also strong in K562, MDA-MB-231, and A375 cells. Moreover, a high selectivity in the cytotoxic activity was observed for butein (9) against HeLa cells when compared to its cytotoxicity against normal cells MRC-5 and HaCaT, with selectivity coefficient being 9.91 for MRC-5 and 4.21 for HaCaT (Tables 2 and 3). Prostate adenocarcinoma PC-3 cells were more sensitive to the cytotoxicity of butein (9) compared with prostate carcinoma DU 145 cells (1.86 lower IC50 value). Butin (1) exhibited potent cytotoxic effect and selectivity against the K562 cells with an IC50 value of 19.67 µM, and against HL-60 cells with an IC50 value of 28.76 µM. Pronounced cytotoxicity of butin (1) was observed against HeLa cells with IC50 value of 44.48 µM. Two different types of prostate cancer, DU 145 and PC-3 cells, exhibited a comparable level of sensitivity to butin (1). Similarly, butin (1), fustin (2), 3-O-methylepifustin (4), taxifolin (6), sulfuretin (10), and cotinignan A (13) demonstrated highest intensity of cytotoxicity against the K562 cell line, of all tested lines. Cotinignan A (13) demonstrated high cytotoxic activity against the K562 cells, with an IC50 concentration of 19.04 µM. Additionally, cotinignan A (13) showed moderate cytotoxic effect against HeLa cells, while lower cytotoxicity was observed against PC-3 and DU 145 prostate cancer cells which showed similar sensitivity. Sulfuretin (10) exhibited the highest cytotoxicity against K562 myelogenous leukemia cells, with its cytotoxic effect being 12 times lower against the DU 145 cell line, which showed the lowest sensitivity. The sensitivity of PC-3 cells to sulfuretin (10) was approximately two times lower than that observed in DU 145 cells. Fisetin (8) exhibited the strongest cytotoxic effect on acute promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells and breast adenocarcinoma MDA-MB-231 cells, showing an IC50 values (42.79 and 45.05 µM respectively) that were nearly two times lower than the IC50 value observed for chronic myelogenous leukemia K562 cells. At a concentration of 400 µM, fisetin did not exhibit any cytotoxicity against DU 145 cells. Eriodictyol (5) demonstrated the highest cytotoxicity towards MDA-MB-231 cells, with an IC50 value of 51.32 µM, whereas DU 145 cells exhibited low sensitivity to eriodictyol. Fustin (2) did not display any cytotoxic effects when administered at doses of 400 µM against HeLa, PC-3, HaCaT, MRC-5, and DU 145 cells. However, it exerted cytotoxic activity against K562, MDA-MB-231, and A375 at lower concentrations (155.30 µM, 178.59 µM, and 186.59 µM, respectively). Sulfuretin auronol (11) displayed cytotoxic activity only against leukemia HL-60 cells and K562 cells. High selective index was observed for HL-60 cells compared to both MRC-5 and HaCaT cells. At 400 µM, taxifolin (6) did not show cytotoxic effects on MRC-5 and DU 145 cells. Both MDA-MB-231 and K562 cells had similar level of sensitivity to taxifolin. The cytotoxic activity of the compounds tested against normal human lung fibroblasts MRC-5 ranged between 63.19 and 400 µM and 131.43–179.73 µg/mL for extracts. The cytotoxicity of the compounds tested against the normal human keratinocytes HaCaT was evaluated, revealing a range of 36.47–400 µM and for extracts from 122.43 to 123.71 µg/mL. 3-O-Methylepifustin (4) demonstrated cytotoxicity towards MDA-MB-231 and A375 cells, along with its pronounced cytotoxic effect on K562 cells.

Table 2.

Selectivity in the cytotoxic activity of Cotinus coggygria extracts and compounds against normal fibroblasts MRC-5

| Selectivity index | HeLa | MDA-MB-231 | HL-60 | K562 | A375 | DU 145 | PC-3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC 50 for MRC-5/IC 50 for malignant cell line | ||||||||

| EE | 1.90 | 1.93 | 4.51 | 4.01 | 2.06 | 0.83 | 1.45 | |

| WE | 2.38 | 1.53 | 3.52 | 2.00 | 1.33 | 0.97 | 1.56 | |

| MME | 2.77 | 1.95 | 3.90 | 2.95 | 1.81 | 0.82 | 1.57 | |

| (1) butin | 2.28 | 0.97 | 3.52 | 5.15 | 1.14 | 0.54 | 0.52 | |

| (2) fustin | > 1 | > 2.24 | > 2 | > 2.58 | > 2.14 | > 1 | > 1 | |

| (3) 3- O -methylfustin | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| (4) 3- O -methylepifustin | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| (5) eriodictyol | 1.05 | 3.02 | 1.32 | 1.23 | 1.12 | 0.40 | 0.55 | |

| (6) taxifolin | > 2.04 | > 2.30 | > 2.14 | > 2.40 | > 2.10 | > 1 | > 1.02 | |

| (8) fisetin | > 6.61 | > 8.88 | > 9.35 | > 4.41 | > 2.48 | > 1 | > 2.5 | |

| (9) butein | 9.91 | 3.84 | 2.09 | 6.17 | 2.19 | 0.95 | 1.76 | |

| (10) sulfuretin | 1.96 | 2.83 | 4.27 | 7.05 | 2.24 | 0.58 | 1.33 | |

| (11) sulfuretin auronol | > 1 | > 1 | > 9.41 | > 3.10 | > 1 | > 1 | > 1 | |

| (12) 3- O - β -D-sitosterol glucoside | > 2 | > 1.2 | NA | > 2 | > 2 | > 1 | > 1 | |

| (13) cotinignan A | 1.15 | NA | NA | 3.32 | NA | 0.84 | 0.83 | |

IC50 values for compounds are presented in µM, while IC50 values for extracts are presented in µg/mL

Table 3.

Selectivity in the cytotoxic activity of Cotinus coggygria extracts and compounds against normal keratinocytes HaCaT

| Selectivity index | HeLa | MDA-MB-231 | HL-60 | K562 | A375 | DU 145 | PC-3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC 50 for HaCaT/IC 50 for malignant cell line | |||||||

| EE | 1.66 | 1.69 | 3.94 | 3.51 | 1.80 | 0.73 | 1.27 |

| WE | 1.66 | 1.07 | 2.46 | 1.40 | 0.93 | 0.68 | 1.09 |

| MME | 2.61 | 1.83 | 3.67 | 2.78 | 1.71 | 0.77 | 1.48 |

| (1) butin | 1.62 | 0.69 | 2.51 | 3.67 | 0.81 | 0.39 | 0.37 |

| (2) fustin | > 1 | > 2.24 | > 2 | > 2.58 | > 2.14 | > 1 | > 1 |

| (3) 3- O -methylfustin | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| (4) 3- O -methylepifustin | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| (5) eriodictyol | 1.17 | 3.35 | 1.47 | 1.37 | 1.25 | 0.44 | 0.61 |

| (6) taxifolin | 2.01 | 2.25 | 2.09 | 2.35 | 2.05 | < 0.98 | 1.00 |

| (8) fisetin | 1.31 | 1.76 | 1.86 | 0.88 | 0.49 | < 0.20 | 0.50 |

| (9) butein | 4.21 | 1.63 | 0.89 | 2.62 | 0.93 | 0.40 | 0.75 |

| (10) sulfuretin | 1.60 | 2.31 | 3.47 | 5.75 | 1.83 | 0.48 | 1.09 |

| (11) sulfuretin auronol | > 1 | > 1 | > 9.41 | > 3.10 | > 1 | > 1 | > 1 |

| (12) 3- O - β -D-sitosterol glucoside | < 0.52 | < 0.31 | NA | < 0.52 | < 0.52 | < 0.26 | 0.26 |

| (13) cotinignan A | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

IC50 values for compounds are presented in µM, while IC50 values for extracts are presented in µg/mL

The mechanisms of anticancer effects were further examined for each of the three extracts and three compounds derived from C. coggygria: butin (1) and butein (9), which showed the highest intensity of cytotoxic activity, and sulfuretin (10), which exhibited not only prominent cytotoxic activity, but which was also one of the most abundant compound in the examined extracts.

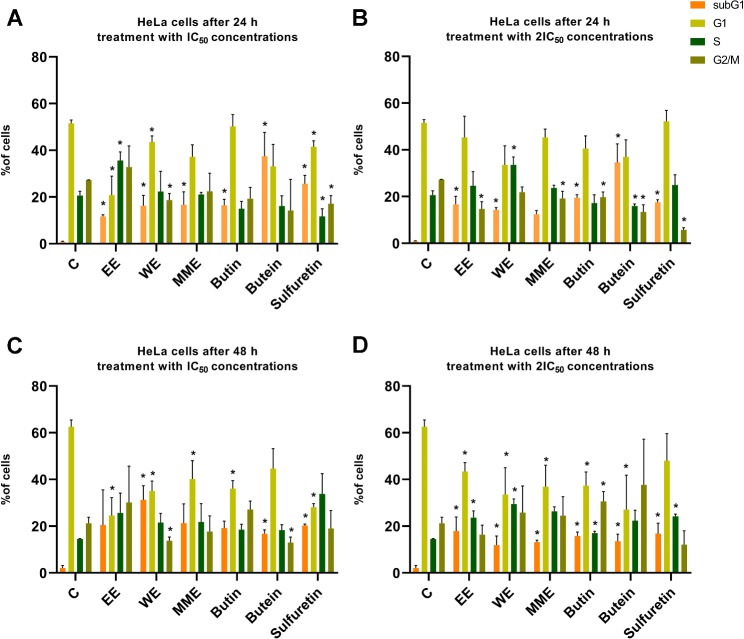

Changes in the cell cycle phase distribution

The influence of extracts and compounds derived from C. coggygria on the distribution of cell cycle phases in HeLa cells exposed to IC50 and 2IC50 concentrations for 24 h and 48 h was firstly explored (Fig. 2). The tested EE, WE, MME, butin, butein, and sulfuretin, caused an increase in the percentage of HeLa cells in the subG1 phase of the cell cycle both after 24 h and 48 h incubation in comparison with control cells. The most significant increase in the percentage of subG1 cells after 24 h was observed in cells treated with butein at the IC50 concentration (37.40% compared to 0.84% in the control cell sample, p < 0.05), followed by cells treated with butein at the 2IC50 concentration after same duration of treatment (34.66% vs. 0.84%, p < 0.05). After 48 h treatment period, the experiment revealed that the increase in the percentage of HeLa cells in the subG1 phase was significant in the cell sample treated with WE at the IC50 concentration (amounting to 31.27% in comparison with the control sample with 2.1% of cells in the subG1 phase, p < 0.05). MME and EE, administered at the IC50 concentration, followed this trend closely with 21.29% and 20.47% of cells in the subG1 phase after treatment, but this increase was not statistically significant. EE induced significant increase in the percentage of HeLa cells in S phase after 24 h treatment with IC50 concentration (p < 0.01) and after 48 h treatment with 2IC50 concentration (p < 0.05, respectively). WE induced significant S phase arrest after 24 h treatment with 2IC50 concentration (p < 0.05) and 48 h treatment with 2IC50 concentration (p < 0.05). In addition, MME and sulfuretin caused increase in the percentage of cells within S phase after 48 h incubation. The increase of the amounts of cells within S phase was significant for treatment with 2IC50 concentration of sulfuretin (p < 0.01). After 48 h of treatment, there was an increase in the proportion of HeLa cells in the G2/M phase when exposed to 2IC50 butein, IC50 and 2IC50 butin, IC50 EE, 2IC50 MME and 2IC50 WE when compared with control cells; increase was significant for cell samples treated with 2IC50 concentration of butin (p < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Alterations in the distribution of cell cycle phases in HeLa cells treated with Cotinus coggygria extracts and compounds, examined after 24 h (A and B) and 48 h (C and D), when applied at IC50 (A and C) and 2IC50 concentrations (B and D). P value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant and the asterisk indicates statistical significance

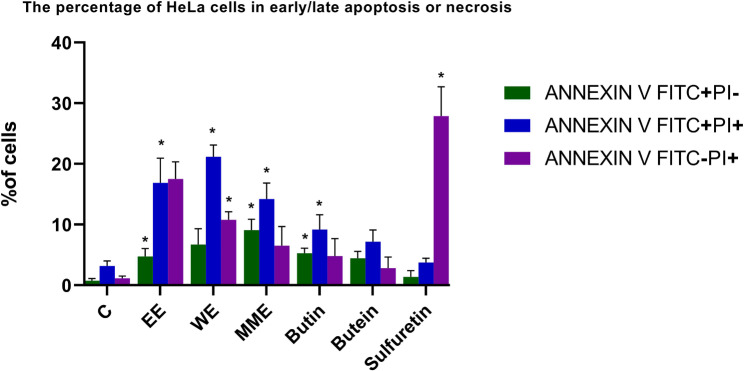

Effects on cell death

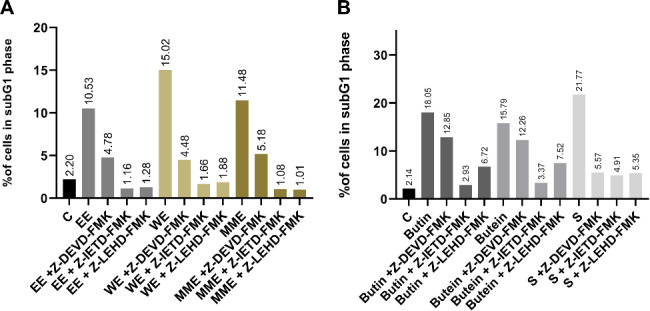

Previous administration of a caspase-3 inhibitor to HeLa cells before exposure to the 2IC50 concentrations of EE, WE, MME, butin, and sulfuretin resulted in a decrease in the proportion of cells in the subG1 phase, compared to those treated only with the extracts or compound. The previous administration of a caspase-3 inhibitor to HeLa cells before exposure to the 2IC50 concentrations of butein resulted in a slight decrease in the proportion of cells in the subG1 phase, as compared to those treated only with the compound (12.26% vs. 15.79%) (Fig. 3). The most notable reduction in the percentage of HeLa cells (4.48% versus 15.02%) was observed in the sample treated with WE along with the caspase-3 inhibitor compared to treatment with WE alone. Administering a caspase-8 inhibitor prior to treatment with 2IC50 concentration of each compound (butin, butein, sulfuretin) and each extract (EE, MME, WE) resulted in a significant decrease in the percentage of HeLa cells in the subG1 phase, compared to cells treated only with the respective extract or compound. The most notable decline in the percentage of HeLa cells was observed in samples treated with MME, EE, and WE (1.08% vs. 11.48%, 1.16% vs. 10.53%, and 1.66% vs. 15.02%, respectively) when combined with the caspase-8 inhibitor, in contrast to treatment with the respective extract alone. In the HeLa cell sample, a decrease in the percentage of cells within the subG1 phase was noted after pretreatment with a caspase-9 inhibitor before exposure to each extract and compound compared to the control cell sample. The most substantial reduction was observed in cells treated with caspase-9 inhibitor along with MME, EE, and WE (1.01% vs. 11.48%, 1.28% vs. 10.53%, and 1.88% vs. 15.02%). These findings suggest that extracts and compounds obtained from C. coggygria and compounds may initiate apoptotic cell death in HeLa cells through caspase − 3, caspase − 8, and caspase − 9, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Determination of the influence of the Z-DEVD-FMK (caspase-3 inhibitor), Z-IETD-FMK (caspase-8 inhibitor), and Z-LEHD-FMK (caspase-9 inhibitor), on the percentage of HeLa cells in the subG1 phase of the cell cycle after 24 h treatment with 2IC50 concentrations of the Cotinus coggygria extracts (A) and compounds (B)

Exposure of HeLa cells to 2IC50 concentrations of each of the three extracts, butin, butein, and sulfuretin caused elevated percentages of early and late apoptotic cells compared to untreated cells (Fig. 4). Notably, treatment with WE resulted in increase in the apoptotic cells (27.90% compared with 3.91% in controls), causing significant increase in the percentage of cells in the late stages of apoptosis (p < 0.01). Similarly, MME treatment induced a significant increase in the proportion of early and late apoptotic HeLa cells (23.30% compared to the control, 3.91%), with a significantly incerased percentage of cells in the early stage of apoptosis (9.09%, p < 0.05) and late stage of apotosis (14.21%, p < 0.05). Conversely, in MME-treated cells a higher percentage of cells in the early apoptotic stage was detected, whereas in WE-treated cells a higher percentage of cells in the late stage was found. Cells exposed to EE showed an increase in propidium iodide positive and annexin V negative dead cells (17.50% compared with 1.16% in controls) and cells undergoing apoptosis, with a significant proportion in both the early (p < 0.05) and late stages (p < 0.05) (21.63% compared with 3.91% in controls). Additionally, treatment with sulfuretin significantly elevated (p < 0.01) the proportion of dead cells stained with propidium iodide only (27.88% compared to 1.16% in controls). Butin displayed a slightly stronger effect compared to butein. Butin significantly increased the percentage of HeLa cells undergoing apoptosis from 3.91% in the control group to 14.47% (p < 0.01 for early apoptotic cells and p < 0.05 for late apoptotic cells), whereas butein increased this percentage from 3.91 to 11.63%, but this increase was not significant when compared with control.

Fig. 4.

The percentage of HeLa cells in early and late apoptosis or necrosis following a 24 h treatment with 2IC50 concentrations of Cotinus coggygria extracts and compounds. P value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant and the asterisk indicates statistical significance

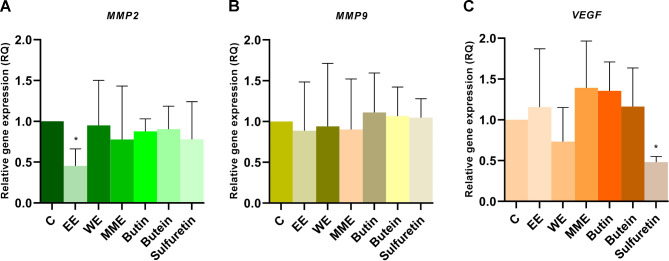

Effects on gene expression levels

This study aimed to investigate the effects of C. coggygria extracts and compounds on MMP2, MMP9, and VEGFA gene expression levels in HeLa cells after 24 h. The results showed that the levels of MMP2 were decreased in HeLa cells treated with all tested compounds and extracts, when compared with control cells, with a significant decrease observed for EE (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5). MMP2 gene expression levels were only slightly decreased in HeLa cells treated with WE, butin, and butein. Additionally, treatment with EE, MME, and WE lowered the levels of MMP9 expression (slightly below the control sample) in HeLa cells. However, treatment with all tested compounds resulted in higher MMP9 levels than in the untreated control cells. Furthermore, after treatment with WE and sulfuretin, VEGFA levels were lower than those in the control. The levels of VEGFA expression were significantly decreased by sulfuretin, with p < 0.01.

Fig. 5.

Gene expression levels of MMP2 (A), MMP9 (B) and VEGFA (C) in HeLa cells after 24 h treatment with Cotinus coggygria extracts and compounds. P value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant and the asterisk indicates statistical significance

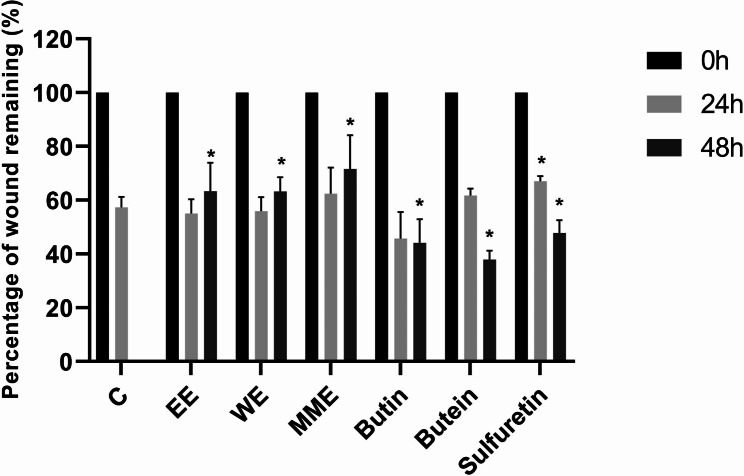

Effects on cell migration

MME (p < 0.05), EE (p < 0.01), WE (p < 0.01), butin (p < 0.05), butein (p < 0.01), and sulfuretin (p < 0.01) exerted significant antimigratory effects on HeLa cells after 48 h incubation, as it could be seen in Fig. 6. Among extracts, MME showed the strongest inhibitory effect on HeLa cell migration following 48 h exposure (wound remaining 71.64%). Sulfuretin and butin exerted similar suppressive effect measured after 48 h (47.88% and 44.19%), while butein had to some extent lower effect (37.91%).

Fig. 6.

Effects of Cotinus coggygria extracts and compounds on HeLa cell migration after 24 and 48 h treatment. P value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant and the asterisk indicates statistical significance

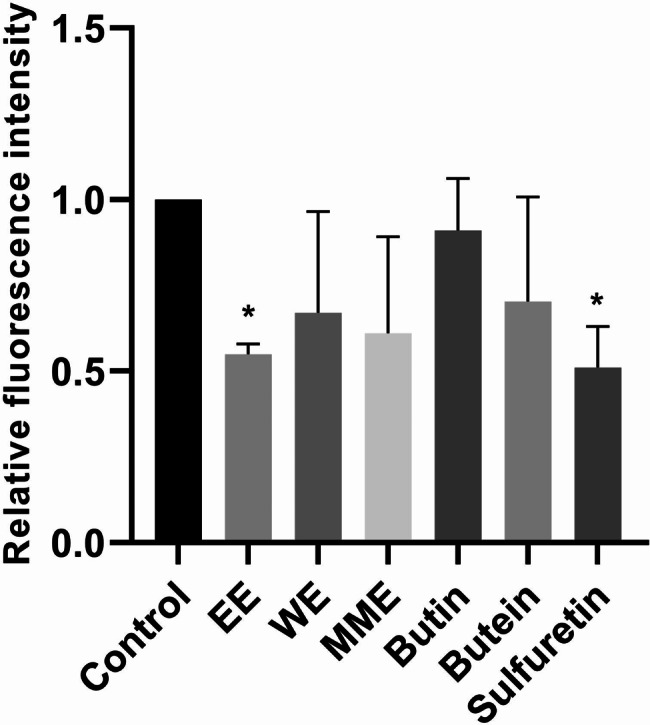

Effects on intracellular ROS levels

To investigate potential antioxidative properties, the effects of EE, MME and WE, butin, butein, and sulfuretin on the concentration of intracellular ROS species in normal fibroblasts MRC-5 were assessed following a 24 h exposure. As depicted in Fig. 7, a reduction in the intracellular levels of ROS species was noted in MRC-5 cells treated with each extract, butein, and sulfuretin after 24 h incubation in comparison to untreated control cells. The significant reduction (p < 0.01) in intracellular ROS levels was observed in MRC-5 cells treated with EE. Treatment of MRC-5 cells with sulfuretin resulted in a significant 50% decrease in intracellular ROS concentration compared to control cells (p < 0.05). Similarly, a nearly high reduction in intracellular ROS levels was observed in MRC-5 cells incubated with MME and WE (39% and 33% respectively). Butein treatment of MRC-5 cells resulted in a 30% reduction in ROS levels compared to the control. In contrast, butin treatment resulted in the lowest decrease in the ROS concentration, with a reduction of only 9%.

Fig. 7.

Effects of 24 h treatment with Cotinus coggygria extracts and compounds on intracellular reactive oxygen species levels in MRC-5 cells. P value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant and the asterisk indicates statistical significance

To investigate the in vitro antioxidative and cytoprotective effects of the analyzed extracts and compounds, experiments were conducted using hydrogen peroxide to elevate intracellular ROS levels. A brief exposure of control MRC-5 cells to hydrogen peroxide led to the generation of ROS, resulting in 2.16 times higher levels of ROS than those observed in cells not exposed to hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 8). Intracellular ROS levels were 2.81 times lower in MRC-5 cells exposed to hydrogen peroxide following treatment with MME when compared with untreated cells exposed to hydrogen peroxide, marking the most prominent decrease in ROS levels observed thus far. However, only treatment with EE induced significant decrease in ROS levels triggered by hydrogen peroxide (p < 0.05). Intracellular ROS concentration was diminished by 2.80×, 2.54×, 1.67×, 1.64×, and 1.23× following treatment with MME, EE, sulfuretin, butein, and WE, respectively. Butin treatment resulted in an elevation of intracellular ROS levels by 2.11 times compared to the control cells treated solely with hydrogen peroxide. The capacities of EE, MME, WE, butein, and sulfuretin to lower oxidative stress levels in MRC-5 cells after hydrogen peroxide treatment indicates their notable antioxidative properties.

Fig. 8.

Effects of 24 h treatment with Cotinus coggygria extracts and compounds on intracellular reactive oxygen species levels in MRC-5 cells induced by hydrogen peroxide. P value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant and the asterisk indicates statistical significance

Discussion

In this study cytotoxic effects of three extracts prepared and twelve compounds isolated from the C. coggygria heartwood were investigated. Extracts were obtained from the wooden part of the plant and had different main constituents than those obtained from other parts of the plant. Chalcone butein (9) demonstrated the strongest cytotoxic effect against all evaluated cancer cell lines, showing the highest cytotoxicity against HeLa cells. Moreover, butein (9) showed excellent selectivity coefficient of 9.91 for MRC-5 and 4.21 for HaCaT cells when compared to its cytotoxicity against HeLa cells. The impact of butein on cell survival was evaluated in another study, uncovering concentration- and time-dependent cytotoxicity on cervical C-33 A and SiHa cancer cells. According to the reported data, the IC50 for SiHa cervical cells was recorded as 8.30 µM following 72 h of incubation with butein, a result consistent with the IC50 value observed in our investigation, which was 8.66 µM for HeLa cells after the same duration of treatment [34]. Comparing to its “closed”, aurone analogue sulfuretin (10), butein (9) exhibited better cytotoxic activity.

Flavanon butin (1) displayed potent cytotoxic effect and selectivity against the K562 leukemia cell line. Comparable levels of sensitivity to butin were observed in two types of prostate cancer, DU 145 and PC-3. To the best of our knowledge, there was no reported data on the cytotoxic activity of butin. It is noteworthy that additional hydroxyl group in position 3 (fustin (2)) or position 5 (eriodyctiol (4)), and methoxy group in position 3 (3-O-methylfustin (3)), decreased the cytotoxic activity.

Fisetin (8) showed the highest cytotoxic activity on breast cancer MDA-MB-231 and HL-60 leukemia cells. On normal human cells MRC-5 fisetin showed no cytotoxic effects at concentration of 400 µM, which is consistent with findings that demonstrated that fisetin exhibited minimal or no impact on healthy cells even at concentrations significantly cytotoxic to breast cancer cells [35]. The use of a combination of fisetin and 5-fluorouracil had been shown to decrease the overall number of intestinal tumors. Fisetin could potentially be utilized as a preventive measure and an adjuvant therapy in conjunction with 5-fluorouracil for the treatment of PIK3CA-mutant colorectal cancer [36]. MDA-MB-453 breast cancer cells exhibited an inverse relationship between cell number and fisetin concentration. As fisetin concentration increased from 0 to 100 µM, a decrease in cell number was observed in various time intervals [37]. Also, fisetin showed cytotoxicity against prostate carcinoma DU 145 at concentrations of 400 µM, but exerted cytotoxic effects against prostate adenocarcinoma PC-3 cells at IC50 values of 159.74 µM. Fisetin, when administered in a time- and dose-dependent manner, was found to induce apoptosis in HeLa cervical cancer cells. According to the research of Ying and colleagues, it was discovered that fisetin displayed anticancer properties and promoted apoptosis in HeLa cells, both in vitro and in vivo [38].

Sulfuretin (10) showed potent cytotoxicity against myelogenous leukemia K562 cells and high selectivity in the cytotoxicity, with SI being 7.05 against normal MRC-5 cells and SI of 5.75 against normal HaCaT cells. Sulfuretin showed the highest selectivity in the cytotoxic activity against K562 cells when compared to MRC-5 cells among all tested compounds and extracts tested on K562 cells. In comparison to sulfuretin, its auronol (11) showed cytotoxic effects only against HL-60 and K562 leukemia cell lines, with no cytotoxic effects against other tested malignant and normal cell lines, revealing that additional hydroxyl group at C-2 and interruption of resonance and electron delocalization has negative effect on the cytotoxic activity. The sensitivity of HL-60 and U937 cells to sulfuretin (10) was found to be moderate, with IC50 concentrations of 56.8 µM and 76.3 µM, respectively [39]. This is consistent with our findings for HL-60 cell line. Sulfuretin (10) and sulfuretin auronol (11) demonstrated cytotoxicity against HL-60 cells with an IC50 concentrations of 36.24 µM and 42.50 µM. In addition, sulfuretin auronol (11) had SI > 9.41 against both tested normal cell lines.

Our results showed that the IC50 values for eriodictyol (5) for the malignant cell lines were relatively low in our study, with the exception of cytotoxic effect on MDA-MB-231 cells. In study conducted by Debnath et al. eriodictyol (5) was tested at concentrations ranging from 0 to 200 µM on four human cancer cell lines: renal cancer SK-RC-45 cells, cervical adenocarcinoma HeLa, colorectal carcinoma HCT-116, and breast adenocarcinoma MCF-7 cells [40]. Similar to our results, eriodictyol (5) had good selectivity in the cytotoxic activity against breast cancer cells (SI > 2.66, while in our study SI values were 3.02 and 3.35), although stronger cytotoxicity was demonstrated against MDA-MB-231 cells then against MCF-7 cells, as shown by Debnath et al. [40]. IC50 values higher than 100 µM and low selectivity of eriodictyol were confirmed for HeLa cells.

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no reported information about the cytotoxic activity of cotinignan A (13), since it was recently isolated for the first time [18]. Cotinignan A (13) exhibited strong cytotoxicity against K562 cells, while lower intensity of cytotoxicity was observed against HeLa cells. Additionally, cotinignan A (13) demonstrated similar cytotoxicity against both PC-3 and DU 145 prostate cancer cell lines. Fustin (2) showed no cytotoxicity against HeLa, DU 145, PC-3, HL-60, HaCaT, and MRC-5 cell lines. Furthermore, fustin (2) only showed activity against MDA-MB-231, K562, and A375 cancer cells. This is in accordance with recently published study which reported cancer suppressive effects of fustin against B16 melanoma cells [41].

Regarding cytotoxic effects of three examined extracts, MME and EE exhibited the strongest cytotoxicity against HL-60 and K562 leukemia cells. WE exerted the strongest cytotoxic effect against leukemia HL-60 cells. Treatment with WE revealed lower intensity of cytotoxicity against DU 145, MRC-5, A375, K562, HL-60, MDA-MB-231, and PC-3 cells compared to MME and EE. Against HeLa cells, EE and WE showed comparable IC50 values, but MME showed lower IC50 values. It is important to evaluate the percentage of compounds in the extracts, particularly when comparing EE and WE. The EE obtained from C. coggygria contained 9.3% butin (1), 0.8% butein (9), and 5% fisetin (8), whereas WE does not contain fisetin (8), all of which could influence or modulate the cytotoxicity of the extracts. Additionally, the content of sulfuretin (10) in EE was 14.4%, whereas it is only 3.4% in WE, which could also impact the cytotoxicity of the extracts. It is essential to consider these differences when discussing the percentage of compounds present in the extracts. The effect of multiple compounds in an extract can be either synergistic or antagonistic or not influenced, which can result in altered cytotoxicity levels when compared to individual compounds. When we compare the cytotoxicity of EE and WE, we can conclude several things: EE exhibited 2.5 times higher cytotoxic effect against K562 and almost the same against A375 cells than WE. WE had 28% lower IC50 values than normal human lung fibroblasts MRC-5. Furthermore, WE had higher IC50 values and consequently lower cytotoxicity against all tested malignant cell lines with the exception of HeLa and DU 145 cells. MME exhibited higher cytotoxicity on HeLa, PC-3, and DU 145 cells than EE and WE. On K562, A375, and DU 145 cells, MME and EE showed comparable cytotoxicity. It could be discussed whether a higher percentage of sulfuretin (10), butin (1), butein (9), and fisetin (8) in EE may influence the high intensity of cytotoxicity against leukemia cell lines. However, we must acknowledge that our ability to do so is limited by the current level of evidence. In brief, the impact of extracts versus individual compounds on normal and malignant cell lines is influenced by many factors, such as the composition of the extracts, specific structural properties and bioactivity of each compound, potential synergistic effects, and sensitivity of distinct cell lines.

Methanol extracts from the leaves and flowers of C. coggygria were examined for their activity on two human carcinoma cell lines, HeLa and LS174 [42]. The leaf extract displayed more potency against the HeLa cell line, while the flower extract displayed a slightly better inhibition effect on the LS174 cell line. The main components in C. coggygria leaf and flower extracts were predominantly gallic acid and its derivatives, with only trace amounts of ursolic acid present [42]. Gospodinova and her team examined the consequences of an aqueous ethanolic extract from smoketree leaves that had been standardized for total polyphenols and flavonoids. The cytotoxicity tests on human breast cancer cells MCF-7 demonstrated a substantial cytotoxic effect [43]. The leaf and flower extracts of C. coggygria showed distinct differences from the compounds derived from extracts obtained from the wooden parts of the same plant examined in this study.

The potential for modulating cell survival has been widely acknowledged, owing to its significant anticancer therapeutic implications. The typical features and energy-dependent biochemical processes of programmed cell death, are well-defined. Apoptosis has been widely acknowledged as a distinct and essential mechanism of “programmed” cell death, characterized by the genetically predetermined eradication of cells [44]. Plant-derived extracts and compounds are more effective and prone to regulation if they induce apoptotic cell death compared with other types of unregulated and stochastic cell death types. The distribution of HeLa cells throughout the phases of the cell cycle after treatment with three compounds (butin (1), butein (9), and sulfuretin (10)) and three extracts (EE, WE, and MME) showed a significant increase in the percentage of cells in the subG1 phase of the cell cycle after treatment with 2IC50 concentrations after 24 h and 48 h for every tested compound or extract when compared to the control, with the exception of MME for 24 h. Butein showed the highest increase in the percentage of cells in the subG1 phase after IC50 treatment after 24 h of incubation among all the tested compounds. The WE treatment of HeLa cells showed the highest proportion of cells in the subG1 phase treated with IC50 concentrations after 48 h. Three extracts, butin, and sulfuretin showed a significant decrease in the percentage of cells in the G1 phase after treatment with the IC50 concentration after 48 h.

Following a 24 h treatment with non-toxic concentrations of butin (1) in MRC-5 cells, a slight decrease in intracellular ROS was observed. In an additional experiment, in which hydrogen peroxide was used to induce higher levels of oxidative stress, the aim was to determine if butin could reduce these levels. However, butin not only failed to decrease these levels, but actually increased ROS levels twofold. In study conducted by Zhang et al. when hydrogen peroxide was used to stimulate a rise in mitochondrial ROS in Chinese hamster lung fibroblast (V79-4) cells, butin treatment decreased the excessively high level of ROS [45]. Hydrogen peroxide elevated the level of 8-OHdG (8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine), a reliable marker of DNA base modification caused by ROS and associated with the pathological process of cancer. In contrast, butin decreased the level of 8-OhdG, in contrast to the findings of this study, our results indicate otherwise [46].

The biological properties of butein (9) have been extensively studied and have been found to possess a wide range of biological effects. These effects include anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, neuroprotective, and anticancer properties, which have been highlighted in various studies [48 and references cited therein]. Chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic drugs primarily focus on cell cycle progression, and butein is a novel anticancer compound that has been reported to disrupt different stages of the cell cycle [48]. Butein led to a substantial increase in the proportion of cells in the subG1 phase of the cell cycle at concentrations of 2IC50 after 24 h and 48 h of incubation. Treatment of HeLa cells with 2IC50 concentration of butein induced accumulation in the S phase of the cell cycle after 48 h of treatment, but this results did not reach statistical significance. However, our study did not detect G2/M phase arrest, in contrast to the study by Moon et al. [48]. Our findings revealed that the use of specific peptide caspase inhibitors demonstrated that butein treatment resulted in the activation of caspase-8 and caspase-9, but not caspase 3-dependent apoptosis. However, butein treatment activated caspase-3 in human hepatoma cancer HepG2 and Hep3B cell lines as showed by Moon et al. [48]. Butein showed a concentration-dependent increase in the number of T-cell leukemia MT-4 and T-cell lymphoma HuT-102 cells in the sub-G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle [49]. Butein treatment notably enhanced the annexin-V proportion in both HepG2 and Hep3B hepatoma cell lines, as demonstrated by Moon et al., and our results corroborate this finding [48]. Specifically, after a 24 h incubation period with a 2IC50 concentration, the proportion of cells in both early and late stages of apoptosis increased remarkably.

The influence of C. coggygria heartwood extracts and three isolated compounds on expression of the three oncogenes involved in invasion and angiogenesis - MMP2, MMP9, and VEGFA was examined to see which extract and compound may be associated with the most favorable gene expression profile. Interestingly, only treatment with the EE significantly lowered MMP2 gene expression levels, which may indicate that the mixture of compounds, abundant in the particular ratios in this extract, may reduce the migratory potential of HeLa cells via this MMP2 mRNA reduction. On the other hand, treatment with sulfuretin, one of the compounds in our extract, reduced the migratory effect of HeLa cells, that might be attributed at least in part to silencing VEGFA expression. We have demonstrated that extracts and isolated compounds have an inhibitory effect on cervical cancer migration and that various compounds and the mixture or combination of compounds from this extract may suppress specific signaling pathways.

In study conducted by Lee et al. sulfuretin markedly and time-sensitively elevated the activation of caspase-8, -9, and − 3 and the cleavage of their substrate PARP in human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cell line [39]. Inhibition of caspase-9 was only found to had a mildly inhibitory effect on sulfuretin-stimulated apoptosis in HL-60 cells. These findings imply that the activation of the intrinsic pathway alone is insufficient to account for the induction of apoptosis by sulfuretin [39]. Proportions of annexin V-positive cells, which indicate early apoptotic cells, were observed to rise in a time-dependent manner following treatment with sulfuretin in HL-60 and U937 cells [39]. These results align with our findings on HeLa cells, where treatment with sulfuretin resulted in an increase in the percentage of annexin V-positive cells (indicators of both early and late stage of apoptotic cell death) and induced apoptosis through activation of initiator caspases-8 and caspase-9, as well as effector caspase-3. Sulfuretin treatment did not increase the percentage of necrotic cells in HL-60 and human histocytic lymphoma U937 cells, contrary to our findings on HeLa cells, where high percentage of secondary necrotic cells stained with PI only was detected. Our findings also indicate that sulfuretin (10) exhibits strong antioxidative and cytoprotective properties, as evidenced by the decreased levels of ROS following treatment with sulfuretin in MRC-5 cells. Additionally, to support this, sulfuretin reduced the levels of ROS induced by hydrogen peroxide in normal fibroblasts. When tested on the L02 hepatic cell line, sulfuretin was found to reduce ROS levels and protect cells from damage caused by treatment with palmitate [50]. Furthermore, sulfuretin had been reported to exhibit hepatoprotective properties by reducing the levels of ROS [50]. Sulfuretin protects hepatic cells through regulation of ROS levels and autophagic flux [50].

To the best of our understanding, we have not come across any research that examined anticancer effects of extracts derived from the wooden parts of C. coggygria. In the present study, EE, WE, and MME triggered apoptosis by activating all three caspases − 3, -8, and − 9. Our results are in line with study by Gospodinova et al. which reported that extract derived from dry leaves of C. coggygria grown in Bulgaria induced significant increase in the percentage of MCF-7 breast cancer cells in the subG1 phase [43]. Furthermore, each of the investigated three extracts suppressed the migration of HeLa cells, while MME and EE also reduced the MMP2 gene expression levels. Our study is the first to report antimigratory effects of extracts obtained from the heartwood of C. coggygria, pointing out remarkable anticancer potential of C. coggygria, as a rich source of bioactive phytochemicals.

Although in vitro cell culture models provide valuable insights into cellular mechanisms and treatment responses, they do not fully replicate the complexity of in vivo systems. Factors, such as tumor microenvironment, tissue interactions, systemic effects, immune responses, and pharmacokinetics, cannot be assessed in this context. For that reason, future studies involving in vivo models are essential to validate the anticancer effectiveness of extracts and compounds from the heartwood of Cotinus coggygria Scop. and better understand the potential translational implications of the investigated extracts and compounds in addition to in vivo evaluation of toxicity.

Conclusions

Extracts obtained from Cotinus coggygria Scop. and twelve isolated compounds exerted selective cytotoxic effects against malignant cell lines. Butein (9) showed the strongest cytotoxicity, especially against HeLa, K562, and MDA-MB-231 cells. The most sensitive malignant cell lines were K562 and HL-60 leukemia cells with the exception of chalcone butein (9) which was the most active against HeLa cells. Among tested extracts, EE exerted the best selective cytotoxic action on HL-60 and K562 leukemia cells. Three extracts, butin, butein, and sulfuretin induced apoptosis in HeLa cells and inhibited migration of HeLa cells in vitro. EE significantly reduced MMP2 expression level in HeLa cells, while sulfuretin significantly decreased VEGFA expression, pointing out their suppressive action on cancer cell invasion and angiogenesis. Three extracts, butein and sulfuretin, exhibited cytoprotective effects in normal human fibroblasts MRC-5. Results of our study might imply that C. coggygria heartwood extracts and compounds possess potent anticancer properties in vitro, especially due to selective targeting of malignant cells and lower cytotoxicity towards normal cells.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Tatjana Petrović and Dušica Petrović for their excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- CC

Column chromatography

- EE

Ethanol extract

- MME

Methylene chloride/methanol extract

- WE

Water extract

- MTT

(3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dyphenyl tetrazolium bromide)

- RQ

Relative quantity

- DCFH-DA

2′,7′ - dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- MMP2

Matrix metalloproteinase 2

- MMP9

Matrix metalloproteinase 9

- VEGFA

Vascular endothelial growth factor A

Author contributions

IP: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft; MN: Conceptualization, Supervision, Resources, Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft; VT: Resources, Writing - review & editing; SM: Review & editing; NP: Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing; TS: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing - review & editing; IZM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

The authors are grateful to the Ministry of Science, Technological Development, and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia for the financial support (Grant numbers: 451-03-66/2024-03/200043, 451-03-66/2024-03/200026, and 451-03-66/2024-03/200168), and to the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (Grant No. F188).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Raw and processed data are stored in the laboratories and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Simpson MG. Plant systematics 3rd edition, Academic press, 2019. 10.1016/C2015-0-04664-0

- 2.Novaković M, Vučković I, Janaćković P, Soković M, Filipović A, Tešević V, Milosavljević S. Chemical composition, antibacterial and antifungal activity of the essential oils of Cotinus coggygria from Serbia. J Serb Chem Soc. 2007;72:1045–51. 10.2298/JSC0711045N. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matić S, Stanić S, Mihailović M, Bogojević D. Cotinus coggygria Sanp.: An overview of its chemical constituents, pharmacological and toxicological potential. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2016;23(4):452–61. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahman S, Jan G, Jan FG, Rahim HU. Phytochemical Investigation and Therapeutical Potential of Cotinus coggygria Scop. in Alloxan-Induced Diabetic Mice. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022; 2022: 8802178. 10.1155/2022/8802178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Ivanova D, Gerova D, Chervenkov T, Yankova T. Polyphenols and antioxidant capacity of Bulgarian medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;96(1–2):145–50. 10.1016/j.jep.2004.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruning E, Seiberg M, Stone VI, Zhao Z. Use of Cotinus coggygria extract treating hemorrhoids. Patent, Pub. No.WO2008055107 A2, 2008.

- 7.Shen Q, Shang D, Ma F, Zhang Z. Pharmacological study on anti-hepatitis effect of Cotinus coggygria scop. Syrup. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi -. China J Chin Materia Med. 1991;16(12):746–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marčetić M, Božić D, Milenković M, Malešević N, Radulović S, Kovačević N. Antimicrobial, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of young shoots of the smoke tree, Cotinus coggygria scop. Phytother Res. 2013;27(11):1658–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antal DS, Ardelean F, Jijie R, Pinzaru I, Soica C, Dehelean C. Integrating Ethnobotany, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacology of Cotinus coggygria and Toxicodendron vernicifluum: what predictions can be made for the European Smoketree? Front. Pharmacol. 2021;12:662852. 10.3389/fphar.2021.662852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thapa P, Prakash O, Rawat A, Kumar R, Srivastava RM, Rawat DS, Pant AK. Essential oil composition, Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, insect antifeedant and sprout suppressant activity in essential oil from Aerial Parts of Cotinus coggygria scop. J Essent Oil Bear Plants. 2020;23:64–76. 10.1080/0972060X.2020.1729246. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ertas B, Okuyan B, Şen A, Ercan F, Önel H, Göğer F, Şener G. The effect of Cotinus coggygria L. ethanol extract in the treatment of burn wounds. J Res Pharm. 2022;26(3):554–64. 10.29228/jrp.153. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballabh B, Chaurasia OP. Traditional medicinal plants of cold desert Ladakh-used in treatment of cold, cough and fever. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;112(2):341–9. 10.1016/j.jep.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majrashi TA, Alshehri SA, Alsayari A, Muhsinah AB, Alrouji M, Alshahrani AM, Shamsi A, Atiya A. Insight into the Biological roles and mechanisms of Phytochemicals in different types of Cancer. Target Cancer Ther Nutrients. 2023;15(7):1704. 10.3390/nu15071704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patra S, Pradhan B, Nayak R, Behera C, Das S, Patra SK, Efferth T, Jena M, Bhutia SK. Dietary polyphenols in chemoprevention and synergistic effect in cancer: clinical evidences and molecular mechanisms of action. Phytomedicine. 2021;90:153554. 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Georgiev V, Ananga A, Tsolova V. Recent advances and uses of grape flavonoids as nutraceuticals. Nutrients. 2014;6(1):391–415. 10.3390/nu6010391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demirci B, Demirci F, Başer KHC. Composition of the essential oil of Cotinus coggygria scop. From Turkey. Flavour Fragr J. 2003;18(1):43–4. 10.1002/ffj.1149. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tzakou O, Bazos I, Yannitsaros A. Essential oils of leaves, inflorescences and infructescences of spontaneous Cotinus coggygria scop. From Greece. Flavour Fragr J. 2005;20(5):531–3. 10.1002/ffj.1456. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novakovic M, Djordjevic I, Todorovic N, Trifunovic S, Andjelkovic B, Mandic B, Jadranin M, Vuckovic I, Vajs V, Milosavljevic S, Tesevic V. New aurone epoxide and auronolignan from the heartwood of Cotinus coggygria scop. Nat Prod Res. 2019;33(19):2837–44. 10.1080/14786419.2018.1508141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valianou L, Stathopoulou K, Karapanagiotis I, Magiatis P, Pavlidou E, Skaltsounis AL, Chryssoulakis Y. Phytochemical analyses of young fustic (Cotinus coggygria heartwood) and identification of isolated colourants in historical textiles. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009;394:871–82. 10.1007/s00216-009-2767-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antal DS, Schwaiger S, Ellmerer-Muller EP, Stuppner H. Cotinus coggygria Wood: Novel Flavanone Dimer and Development of an HPLC/UV/MS Method for the Simultaneous Determination of Fourteen Phenolic Constituents. Planta Med. 2010;76(15):1765–72. 10.1055/s-0030-1249878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.da Costa MP, Bozinis MC, Andrade WM, Costa CR, da Silva AL, Alves de Oliveira CM, Kato L, Fernandes OFL, Souza LKH, Silva MRR. Antifungal and cytotoxicity activities of the fresh xylem sap of Hymenaea courbaril L. and its major constituent fisetin. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:245. 10.1186/1472-6882-14-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westenburg HE, Lee KJ, Lee SK, Fong HH, van Breemen RB, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD. Activity-guided isolation of antioxidative constituents of Cotinus coggygria. J Nat Prod. 2000;63(12):1696–8. 10.1021/np000292h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65(1–2):55–63. 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohno M, Abe T. Rapid colorimetric assay for the quantification of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). J Immunol Methods. 1991;145(1–2):199–203. 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90327-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matić IZ, Aljančić I, Žižak Ž, Vajs V, Jadranin M, Milosavljević S, Juranić ZD. In vitro antitumor actions of extracts from endemic plant Helichrysum zivojinii. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013; 13: 36. 10.1186/1472-6882-13-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Ormerod MG. Flow cytometry. A practical approach. Oxford University Press; 2000.

- 27.Matić IZ, Ergün S, Đorđić Crnogorac M, Misir S, Aliyazicioğlu Y, Damjanović A, Džudžević-Čančar H, Stanojković T, Konanç K, Petrović N. Cytotoxic activities of Hypericum perforatum L. extracts against 2D and 3D cancer cell models. Cytotechnology. 2021;73(3):373–89. 10.1007/s10616-021-00464-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matić IZ, Aljančić I, Vajs V, Jadranin M, Gligorijević N, Milosavljević S, Juranić ZD. Cancer-suppressive potential of extracts of endemic plant Helichrysum Zivojinii: effects on cell migration, invasion and angiogenesis. Nat Prod Commun. 2013;8:1291–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mihailović N, Marković V, Matić IZ, Stanisavljević NS, Jovanović ŽS, Trifunović S, Joksović L. Synthesis and antioxidant activity of 1,3,4-oxadiazoles and their diacylhydrazine precursors derived from phenolic acids. RSC Adv. 2017;7:8550–60. 10.1039/C6RA28787E. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boucherle B, Peuchmaur M, Boumendjel A, Haudecoeur R. Occurrences, biosynthesis and properties of aurones as high-end evolutionary products. Phytochemistry. 2017;142:92–111. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hashida K, Tabata M, Kuroda K, Otsuka Y, Kubo S, Makino R, Kubojima Y, Tonosaki M, Ohara S. Phenolic extractives in the trunk of Toxicodendron vernicifluum: chemical characteristics, contents and radial distribution. J Wood Sci. 2014;60:160–8. 10.1007/s10086-013-1385-8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Merwe JP, Ferreira D, Brandt EV, Roux DG. Immediate Biogenetic precursors of Mopanols and Peltogynols. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1972. 10.1039/C39720000521. 521 – 22. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiehlmann E, Slade PW. Methylation of Dihydroquercetin acetates: synthesis of 5-O-Methyldihydroquercetin. J Nat Prod. 2003;66(12):1562–6. 10.1021/np034005w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang PY, Hu DN, Kao YH, Lin IC, Liu FS. Butein induces apoptotic cell death of human cervical cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2018;16(5):6615–23. 10.3892/ol.2018.9426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith ML, Murphy K, Doucette CD, Greenshields AL, Hoskin DW. The Dietary Flavonoid Fisetin causes cell cycle arrest, caspase-dependent apoptosis, and enhanced cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs in Triple-negative breast Cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117:1913–25. 10.1002/jcb.25490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan N, Jajeh F, Eberhardt EL, Miller DD, Albrecht DM, Van Doorn R, Hruby MD, Maresh ME, Clipson L, Mukhtar H, Halberg RB. Fisetin and 5-fluorouracil: effective combination for PIK3CA-mutant colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2019;145(11):3022–32. 10.1002/ijc.32367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo G, Zhang W, Dang M, Yan M, Chen Z. Fisetin induces apoptosis in breast cancer MDA-MB-453 cells through degradation of HER2/neu and via the PI3K/Akt pathway. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2019;33(4):e22268. 10.1002/jbt.22268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ying TH, Yang SF, Tsai SJ, Hsieh SC, Huang YC, Bau DT, Hsieh YH. Fisetin induces apoptosis in human cervical cancer HeLa cells through ERK1/2-mediated activation of caspase-8-/caspase-3-dependent pathway. Arch Toxicol. 2012; 86(2): 263–73. Erratum in: Arch Toxicol. 2012; 86(5):823. 10.1007/s00204-011-0754-6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Lee KW, Chung KS, Seo JH, Yim SV, Park HJ, Choi JH, Lee KT. Sulfuretin from heartwood of Rhus verniciflua triggers apoptosis through activation of Fas, Caspase-8, and the mitochondrial death pathway in HL-60 human leukemia cells. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113(9):2835–44. 10.1002/jcb.24158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Debnath S, Sarkar A, Mukherjee DD, Ray S, Mahata B, Mahata T, Parida PK, Das T, Mukhopadhyay R, Ghosh Z, Biswas K. Eriodictyol mediated selective targeting of the TNFR1/FADD/TRADD axis in cancer cells induce apoptosis and inhibit tumor progression and metastasis. Transl Oncol. 2022;21:101433. 10.1016/j.tranon.2022.101433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumazoe M, Fujimura Y, Shimada Y, Onda H, Hatakeyama Y, Tachibana H. Fustin suppressed melanoma cell growth via cAMP/PKA-dependent mechanism. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2024;88(8):900–7. 10.1093/bbb/zbae072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Savikin K, Zdunic G, Jankovic T, Stanojkovic T, Juranic Z, Menkovic N. In vitro cytotoxic and antioxidative activity of Cornus mas and Cotinus coggygria. Nat Prod Res. 2009;23(18):1731–9. 10.1080/14786410802267650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]