Abstract

Reproductive cancers, including prostate and ovarian cancer, are highly prevalent worldwide and pose significant health challenges. The molecular underpinnings of these cancers are complex and involve dysregulation of various cellular pathways. Understanding these pathways is crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies. This review aims to provide an overview of the molecular pathways implicated in prostate and ovarian cancers, highlighting key genetic alterations, signaling cascades, and epigenetic modifications. A comprehensive literature search was conducted using databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Articles focusing on molecular pathways in prostate and ovarian cancer were reviewed and analyzed. In prostate cancer, recurrent mutations in genes like AR, TP53, and PTEN drive tumor growth and progression. Androgen signaling plays a significant role, with alterations in the AR pathway contributing to resistance to antiandrogen therapies. In ovarian cancer, high-grade serous carcinomas are characterized by mutations in TP53, BRCA1/2, and homologous recombination repair genes. PI3K and MAPK pathways are frequently activated, promoting cell proliferation and survival. Epigenetic alterations, including DNA methylation and histone modifications, are also prevalent in both cancer types. The molecular pathways involved in prostate and ovarian cancer are diverse and complex. Targeting these pathways with precision medicine approaches holds promise for improving patient outcomes. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanisms of resistance and identify novel therapeutic vulnerabilities.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Ovarian cancer, Molecular pathways, Androgen receptor, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, PTEN, BRCA1, BRCA2, Targeted therapy

Introduction

Cancer is a diverse collection of diseases distinguished by unregulated cell growth and the ability to infiltrate or metastasize to other areas of the body [1, 2]. The wide range of cancer types arises from differences in the cells from which they originate and the molecular abnormalities that propel their advancement [3–5]. On a global scale, cancer is a prominent contributor to illness and death, with millions of new cases identified each year [6]. Reproductive malignancies, such as prostate and ovarian tumors, impose substantial health burdens [6–8].

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in males worldwide and is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in many regions [8]. The androgen receptor (AR) signaling pathway is essential for the progression and growth of prostate cancer. The AR receptor is a nuclear hormone receptor that regulates the transcription of genes involved in cell growth and survival. It accomplishes this by binding to androgens such as testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a process that occurs in the nucleus [9–13]. Aberrant and deviant AR signaling, often resulting from overexpression, genetic abnormalities, or persistent activation, promotes the proliferation of prostate cancer and contributes to the emergence of resistance to conventional therapies [14]. Thus, the emphasis on the AR pathway remains crucial in the management of prostate cancer.

Ovarian cancer, although less prevalent than prostate cancer, is more lethal among gynecological malignancies. The primary reason for this is that ovarian cancer is frequently detected at advanced stages and is characterized by its aggressive nature [15]. Both forms of cancer have distinct epidemiological patterns, risk factors, and clinical behaviors, which require targeted investigation into their specific molecular mechanisms [7].

The formation and progression of cancer are strongly linked to disruptions in molecular pathways that regulate cellular activities, including proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [16–18]. Deviations from the normal functioning of these pathways, frequently caused by genetic mutations, epigenetic changes, or environmental influences, can result in cancer progression [19–21]. Understanding these pathways is essential for discovering potential biomarkers for early identification, prognostic indicators, and treatment targets. Hence, it is imperative to comprehend the precise molecular mechanisms that contribute to reproductive cancers to optimize therapy outcomes.

This study aims to provide an up-to-date overview of the molecular pathways implicated in prostate and ovarian cancers. Notable progress in the fields of genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics has broadened our understanding of the molecular characteristics of various malignancies. Prostate cancer research has emphasized the functions of androgen receptor signaling, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, and DNA damage response pathways. Furthermore, research on ovarian cancer has prioritized the significance of pathways involving BRCA1/2 mutations, homologous recombination repair, and angiogenesis [12, 14, 22–24].

Recent research has unveiled novel and distinct alterations at the molecular level while elucidating the interplay between various pathways that contribute to the diversity of cancer and its capacity to withstand therapy. New areas of interest encompass the examination of the interplay between AR signaling and immune evasion in prostate cancer, as well as the communication between the tumor microenvironment and cellular metabolism in ovarian cancer [25–28]. This review aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the molecular basis of these cancers, focusing on the latest discoveries, and highlights potential avenues for tailored treatment approaches.

Purpose of the review

The primary aim of this study is to strengthen the current comprehension of the molecular pathways involved in prostate and ovarian cancers. The review aims to conduct a thorough examination of these pathways, with the objective of elucidating their role in the initiation, progression, and resistance to therapy of illnesses. This review aims to consolidate the findings of recent research in order to present a comprehensive analysis of the primary molecular pathways implicated in both forms of cancer. This will highlight the clinical importance of these pathways in terms of their function in diagnosing, predicting the outcome, and treating the illnesses.

The review will identify deficiencies in the current knowledge base and provide prospective topics for future research to remedy these deficiencies. Another essential aspect of this review is to assess the feasibility of transferring information acquired from researching molecules to practical medical interventions, particularly within the framework of personalised medicine. The evaluation seeks to enhance the capacity of clinicians and researchers to provide more effective diagnostic tools and treatment alternatives for prostate and ovarian malignancies, eventually resulting in enhanced patient outcomes. It achieves this by providing a comprehensive comprehension of these routes.

Search strategy

In order to complete this evaluation, a methodical search technique was utilised to guarantee a thorough examination of the pertinent literature. The search was performed using prominent scientific databases, such as PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus, with an emphasis on research published during the past ten years to encompass the latest developments in the field. The search utilised the following keywords: ‘‘prostate cancer,’’ ‘‘ovarian cancer,’’ ‘‘molecular pathways,’’ ‘‘androgen receptor signalling,’’ ‘‘BRCA mutations,’’ ‘‘PI3K/AKT/mTOR,’’ ‘‘homologous recombination,’’ and ‘‘tumour microenvironment.’’

The selected studies had explicitly stated inclusion criteria to assure the literature's quality and relevance. The criteria included original research publications, reviews, and meta-analyses that have undergone peer review that offered comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms, signalling pathways, and genetic or epigenetic changes in prostate and ovarian malignancies. In addition, the study encompassed both clinical and preclinical investigations that provided substantial insights into the translational capacity of molecular discoveries.

On the other hand, the exclusion criteria were set up to eliminate less relevant studies. Non-English articles were removed to ensure consistency in language comprehension. Studies that did not specifically examine molecular pathways or lacked adequate methodological information were also omitted in order to maintain the review's emphasis on rigorous, thorough research. Publications published before 2013 were mostly not included, save for influential works that offered crucial foundational knowledge required to comprehend the advancement of modern molecular understandings.

The search procedure involved initially reviewing titles and abstracts to identify relevant articles, followed by a thorough assessment of the complete text to confirm their adherence to the inclusion criteria. Furthermore, reference lists of selected publications were thoroughly examined in order to discover any additional relevant studies. The collected literature was subsequently classified methodically according to the kind of cancer and the precise biological pathways that were addressed.

Molecular pathways in prostate cancer

Prostate cancer, a prevalent malignancy, involves the aberrant activation and dysregulation of specific cellular pathways that contribute to its initiation, progression, and therapeutic resistance. Key molecular pathways implicated in prostate cancer include the androgen receptor (AR) pathway, the PI3K/Akt pathway, the MAPK pathway, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, and the PTEN pathway [29–33]. These pathways regulate cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and invasion, among other critical cellular processes. Understanding the molecular basis of prostate cancer enables the development of targeted therapies that disrupt these pathways and effectively diminish tumor growth and progression. These pathway are broadly explained in the Table 1 below;

Table 1.

Showing molecular pathways in prostate cancer

| Pathway | Mechanism overview | Key components | Dysregulation in prostate cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Androgen receptor signaling | - Governs proliferation, differentiation, and function of prostate epithelial cells, primarily through androgens like DHT [32, 34] |

- Androgen Receptor (AR) - Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) |

- Overexpression of AR leads to increased androgen sensitivity, arising from gene amplification or post-translational modifications [35] - Dysregulated AR signaling contributes to prostate cancer onset and progression [36] |

| B. PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway | - Regulates cell growth, proliferation, and survival; activated by growth factors binding to receptors, leading to a cascade that includes PI3K, AKT, and mTOR [29] |

- Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) - Protein Kinase B (AKT) - Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) |

- Genetic alterations like PI3KCA mutations and PTEN loss cause abnormal pathway activation, leading to increased cell proliferation, survival, and therapeutic resistance [37, 38] |

| MAPK pathway | The MAPK pathway transmits signals from cell surface receptors, initiating a phosphorylation cascade that ultimately activates ERK, modulating gene expression involved in cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis [33, 39] | Ras, Raf (e.g., Raf-1), ERK, MEK | Dysregulation of the MAPK pathway in prostate cancer is often driven by specific mutations, including point mutations in the KRAS and BRAF genes, as well as alterations in the NRAS gene. Additionally, amplifications of the EGFR and FGFR2 genes have been implicated in the enhanced signaling of this pathway. These genetic alterations contribute to the tumorigenic processes, leading to increased cell invasion, survival, and proliferation [33, 39] |

| PTEN pathway | The PTEN pathway is a tumor suppressor pathway that inhibits the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway by dephosphorylating PIP3, preventing hyperactivation that promotes cancer cell proliferation and survival | PTEN | Loss of PTEN function, typically due to mutations or chromosomal deletions, results in increased proliferation and metastasis [31] |

| Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway | The Wnt/β-catenin pathway regulates cell proliferation and differentiation through β-catenin stabilization and nuclear translocation upon Wnt ligand binding, facilitating tumor growth | Wnt ligands, LRP5/6, Frizzled, β-catenin | Abnormal activation due to mutations or dysregulated Wnt production contributes to prostate cancer initiation and metastasis [30] |

| Notch pathway | Notch signaling involves interactions between Notch receptors and ligands leading to the release of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD), influencing tissue differentiation and cell fate | Notch receptors (Notch1-4), Jagged, Delta-like | Dysregulated Notch signaling, marked by altered expression of receptors and ligands, promotes tumor progression in prostate cancer [40] |

Molecular pathways in ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer is a complex disease with a variety of molecular pathways involved in its development and progression [41]. These pathways include the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, the MAPK pathway, and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (Table 2). The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is involved in cell growth and survival, and its dysregulation can lead to uncontrolled cell proliferation. The MAPK pathway plays a role in cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, and its deregulation can contribute to tumor growth and resistance to therapy. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is involved in cell proliferation and differentiation, and its dysregulation can lead to the development of cancer stem cells.

Table 2.

Showing the molecular pathway of ovarian cancer

| Pathway | Mechanism overview | Key components | Dysregulation in ovarian cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| PI3K/AKT/mTOR (PAM) | About 70% of ovarian cancer cases involve the activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, crucial for regulating cell growth, survival, proliferation, and metabolism [41–43]. The pathway includes multiple upstream regulators and downstream effectors linked with oncogenesis [44] |

- Class I PI3Ks (PI3Kα, PI3Kβ, PI3Kδ, PI3Kγ) - AKT (p110α, p110β, p110δ) - mTOR (mTORC1, mTORC2) - PTEN |

Genetic alterations such as PIK3CA mutations are common and lead to hyperactivation, contributing to tumorigenesis and resistance to therapies [45–48] |

| MAPK | The MAPK pathway, also known as the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway, regulates cell processes, including proliferation and differentiation [49]. It transmits signals from growth factor receptors leading to activation and phosphorylation of downstream kinases [50] |

- Ras - Raf - MEK1/2 - ERK - RTKs and GPCRs |

Inactivating the MAPK pathway could provide a therapeutic target for type I ovarian tumors with K-ras and B-raf mutations, whereas it is a positive factor in high-grade serous carcinoma. Additionally, alterations in HRAS and NF1 have also been implicated in this dysregulation [51, 52] |

| PTEN pathway | PTEN is a tumor suppressor gene with phosphatase activity that negatively regulates the PI3K pathway by dephosphorylating PIP3 to PIP2, impacting cell proliferation and survival | PTEN gene, PIP3, PIP2, PI3K | Loss of function mutations in PTEN lead to continuous PI3K signaling, contributing to tumorigenesis; mutations found in approximately 15% of ovarian carcinomas but rare in other cancers [45 48, 53, 54] |

| BRCA1/2 pathway | BRCA1 and BRCA2 are critical for DNA repair and transcription regulation; mutations are associated with hereditary ovarian cancer | BRCA1 gene, BRCA2 gene | Germline mutations contribute to a high risk of ovarian cancer in carriers (60% for BRCA1, 30% for BRCA2); implicated in type II carcinomas [45, 55, 56] |

| Wnt/β-catenin pathway | This pathway regulates cell differentiation and proliferation; dysregulation is associated with endometrioid cancers | Wnt proteins, β-catenin, CTNNB1 | Mutations in β-catenin and Wnt pathway components are observed in around 30% of endometrioid ovarian tumors, leading to increased treatment resistance and neovascularization [57–60] |

| Notch pathway | The Notch signaling pathway governs cell fate decisions and interacts with other signaling pathways like Wnt; jagged ligands activate this pathway through crosstalk with VEGF | Notch receptors, Jagged1, Jagged2, DLL1, DLL3, DLL4 | Aberrant activation linked to ovarian carcinoma; interactions with Wnt/β-catenin enhance proliferation and migration of cancer stem cells [57, 61, 62] |

Targeting molecular pathways in reproductive cancers

-

A.

Androgen receptor inhibitors in prostate cancer

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), which can be achieved through medical or surgical means, is a cornerstone in the treatment of prostate cancer. This therapy reduces the levels of male hormones or blocks the activation of androgen receptors (AR), thereby inhibiting the growth of prostate cancer cells. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) can efficiently inhibit the growth of tumours by decreasing the amounts of circulating androgens or preventing their interaction with the AR [63–66]. However, despite an initial favourable reaction, a considerable proportion of men eventually develop castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). CRPC, also known as castration-resistant prostate cancer, is a very aggressive variant of the disease that continues to depend on androgen receptor (AR) signalling even in the presence of low testosterone levels. This is a substantial obstacle for therapy.

Several advanced AR inhibitors have been created to specifically target the ongoing activation of AR signalling in CRPC. These medications have a stronger suppressive impact on the activity of the AR through several methods (Table 3) [67, 68].

Table 3.

summarizes key AR inhibitors, illustrating their mechanisms, efficacy, safety profiles, and clinical applications

| Drug | Mechanism of action | Efficacy | Safety profile | Clinical applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Enzalutamide | Enzalutamide inhibits AR translocation to the nucleus, prevents its binding to DNA, and obstructs the recruitment of coactivators | It has shown significant efficacy in extending survival in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), effectively blocking genes critical for cancer cell survival and proliferation [74, 80] | Common side effects include fatigue, hot flashes, hypertension, and seizures due to its penetration into the central nervous system (CNS) [74, 80] | Widely used for metastatic CRPC; ongoing studies are evaluating its use in earlier stages of prostate cancer [80] |

| 2. Apalutamide | Apalutamide binds directly to the AR, preventing its activation and subsequent translocation into the nucleus | Demonstrated effectiveness in both metastatic and non-metastatic CRPC settings [74, 80, 89] | Similar to enzalutamide but with a slightly lower incidence of CNS-related side effects [89] | Approved for use in both non-metastatic and metastatic CRPC [80] |

| 3. Darolutamide | Darolutamide has a unique structure that limits its ability to cross the blood–brain barrier, which may reduce CNS-related side effects | Effective in delaying metastasis in non-metastatic CRPC patients [74, 80] | Generally well tolerated with fewer CNS side effects compared to enzalutamide [80] | Approved for non-metastatic CRPC; ongoing trials are assessing its efficacy in combination with other therapy |

Enzalutamide is a potent and efficient inhibitor of the AR that impedes the translocation of AR into the nucleus, inhibits its interaction with DNA, and obstructs the recruitment of coactivators. Enzalutamide has demonstrated significant efficacy in extending the lifespan of individuals with CRPC by blocking the activation of key genes that are essential for the survival and proliferation of cancerous cells. Currently, it is a widely employed therapy for persons suffering from metastatic CRPC [69–71] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The Z15 mechanism effectively inhibits the androgen receptor (AR) pathway, offering a solution to antiandrogen resistance. By binding to both the ligand-binding domain (LBD) and the activation function 1 (AF1) of AR, Z15 reduces AR nuclear translocation and antagonizes AR functionality. Additionally, it promotes the degradation of AR and AR variants (ARVs) through the proteasome pathway. This multifaceted approach allows Z15 to address issues related to AR mutations, overexpression, and resistance induced by ARVs, making it a promising therapeutic option in combating resistant forms of prostate cancer

Apalutamide, similar to enzalutamide, binds directly to the AR, preventing its activation and translocation into the nucleus. This inhibition effectively disrupts the transcriptional programmes regulated by AR. Apalutamide has shown promising results in treating both metastatic and non-metastatic CRPC, making it a valuable treatment option for patients at different stages of disease progression [72–75].

Darolutamide possesses a unique structural composition that restricts its capacity to traverse the blood–brain barrier, setting it apart from other androgen receptor inhibitors. This attribute may lead to a decreased frequency of adverse consequences in the central nervous system. This characteristic is particularly vital for those who may be prone to cognitive problems. Darolutamide has shown efficacy in delaying the metastasis of cancer in patients with non-metastatic CRPC, providing an alternative and effective option for managing the illness [76, 77] (Table 4, 5).

Table 4.

summarizes key PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors, illustrating their mechanisms, efficacy, safety profiles, and clinical applications

| Inhibitor | Mechanism | Efficacy | Clinical application | Safety profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Abiraterone | Primarily a CYP17A1 inhibitor that reduces androgen production. This reduction indirectly affects the PI3K pathway by decreasing androgen receptor activity | Demonstrated ability to lower androgen levels effectively, leading to suppression of AR signaling. This is crucial for inhibiting prostate cancer cell growth | Mainly utilized in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) to improve treatment outcomes by diminishing downstream PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling | Generally well-tolerated; common side effects include hypertension and hypokalemia [74, 107] |

| 2. Ipatasertib | A selective AKT inhibitor that directly inhibits AKT activity, which is a key player in cell survival and proliferation | Shows enhanced efficacy when used in conjunction with abiraterone in mCRPC patients with PTEN loss, leading to improved clinical outcomes | Acts as a targeted therapy specifically for patients who possess particular genetic mutations (e.g., PTEN loss) that result in augmented AKT activation | Common side effects may include diarrhea and rash; ongoing studies are evaluating the long-term safety and tolerability of this drug [74, 107] |

| 3. Alpelisib | Selectively inhibits the PI3Kα isoform, a vital component of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway implicated in cancer proliferation | Shown to effectively treat ovarian cancer patients harboring PIK3CA mutations, by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis | Approved for use in specific subtypes of breast cancer, alpelisib shows promise in treating ovarian cancer as well | Adverse effects that may occur include hyperglycemia and gastrointestinal disturbances [108, 109] |

| 4. Everolimus | An mTOR inhibitor that disrupts the activity of mTORC1, a critical regulator of cell growth and metabolism | Typically used in combination therapies to boost anti-tumor effects by targeting multiple pathways concurrently, enhancing overall therapeutic efficacy | Approved for various cancers, with ongoing studies examining its potential role in ovarian cancer as part of combination treatment regimens | Known side effects include stomatitis, infections, and fatigue [107, 110] |

Table 5.

presenting the pathway mechanisms involved in the MAPK pathway relevant to prostate and ovarian cancer

| Pathway | Mechanism overview | Key components | Dysregulation in prostate and ovarian cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK | The MAPK pathway regulates crucial cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, and survival through a cascade of kinase activation | RAS, RAF, MEK, ERK | Dysregulated activation often due to mutations in RAS or RAF, leading to increased cell proliferation and survival, contributing to tumorigenesis in both prostate and ovarian cancer [125, 126] |

| MEK inhibition | Targeting MEK (e.g., selumetinib) disrupts signals that promote growth and survival, revealing therapeutic potential in genetically altered tumors | MEK1, MEK2 | In prostate cancer, MEK inhibitors can enhance therapeutic outcomes, particularly in tumors with mutations in the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway [125, 126]. In ovarian cancer, low-grade serous variants show similar response profiles [125, 127] |

| Tumor microenvironment | The interactions between tumor cells and their microenvironment affect signaling outcomes and treatment responses | ECM components, cytokines, immune cells | In both cancers, abnormalities in the tumor microenvironment can foster MAPK pathway activation, raising resilience against therapies [125, 128] |

| Pathway crosstalk | Activation of compensatory pathways (e.g., PI3K/AKT) often occurs in response to MAPK inhibition, sustaining tumor growth | PI3K, AKT | Resistance against MAPK inhibitors can result from crosstalk with alternative pathways, complicating treatment strategies in prostate and ovarian cancers [126, 128] |

| Genetic alterations | Mutations in key genes can lead to alterations in MAPK signaling and therapeutic resistance | HER2, NF1 | Oncogenic mutations lead to resistance in therapy; overexpression of HER2 and loss of NF1 in tumors impacts responsiveness to MAPK inhibitors, particularly in ovarian cancer [127, 128] |

| Adaptive resistance | Tumor cells may adapt to targeted therapies by upregulating different survival pathways, necessitating combination treatment strategies | Various survival pathways | In both types of cancer, adaptive responses to therapies highlight the need for combinations to effectively counteract resistance mechanisms and improve patient outcomes [125, 127] |

Abiraterone is an effective androgen biosynthesis inhibitor used primarily for prostate cancer treatment. By blocking the CYP17 enzyme, it reduces testosterone levels, critical for the growth of metastatic CRPC and high-risk metastatic CSPC, often in conjunction with prednisone to alleviate side effects [78]. Abiraterone acetate blocks CYP17's 17-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase activities, diminishing androgen synthesis in testes, adrenal glands, and tumor tissues [78]. It is noted for its effectiveness in both metastatic CRPC and CSPC alongside standard androgen deprivation therapy [79, 80]. Despite manageable side effects, there are significant risks requiring careful patient management [78]. Future research focuses on combining abiraterone with next-generation androgen receptor antagonists to enhance treatment efficacy [80].

Upcoming AR degraders and inhibitors

The study "Discovery of ARD-1676 as a Highly Potent and Orally Efficacious AR PROTAC Degrader with a Broad Activity against AR Mutants for the Treatment of AR + Human Prostate Cancer, presents ARD-1676, a novel PROTAC targeting the androgen receptor (AR) in prostate cancer. ARD-1676 exhibits potent degradation efficacy with DC50 values of 0.1 nM in VCaP cells and 1.1 nM in LNCaP cells. With impressive oral bioavailability rates—up to 99% in monkeys—it effectively inhibits tumor growth in preclinical models, reducing AR protein levels by 96% within 6 h of administration. Importantly, it addresses resistance mechanisms linked to AR mutations [81].

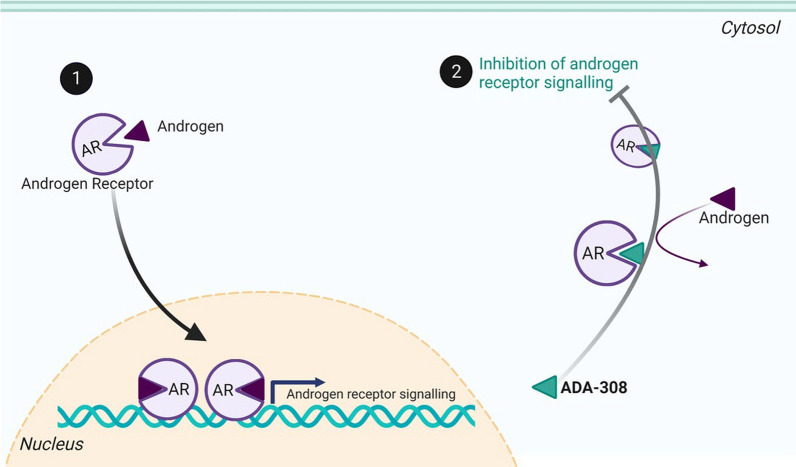

A recent study by Nouruzi et al. titled ‘‘Targeting adenocarcinoma and enzalutamide-resistant prostate cancer using the novel anti-androgen inhibitor ADA-308,’’ reveals the promise of ADA-308 in treating resistant prostate cancer. Key findings indicate that ADA-308 significantly inhibits cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo, outpacing current anti-androgens like enzalutamide and darolutamide in potency against androgen receptor action. The mechanism suggests it may degrade AR variants linked to treatment resistance. These insights highlight the importance of ongoing research into anti-androgen therapies like ADA-308, which are vital in addressing the challenges of advanced prostate cancer and improving patient outcomes [82] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

ADA-308 disrupts androgen signaling by binding to the androgen receptor (AR), preventing natural androgens from binding. In normal processes, androgen binding initiates AR nuclear translocation and subsequent AR-mediated signaling. However, when ADA-308 occupies the androgen binding site, it inhibits AR activity, effectively blocking the signaling pathway activated by androgens. This mechanism showcases ADA-308’s potential therapeutic role in conditions driven by androgen excess. The graph in Fig. 2 illustrates these steps clearly, emphasizing the competitive nature of ADA-308 in relation to androgen binding and its impact on AR signaling

Furthermore, Bagal et al. [83] highlights significant advancements in developing orally bioavailable androgen receptor (AR) degraders for prostate cancer treatment. Prostate cancer, especially CRPC, poses treatment challenges due to drug resistance to traditional therapies, such as androgen deprivation therapy and AR antagonists. The study introduces a new class of compounds utilizing proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) that effectively degrade the AR, thus overcoming resistance and offering greater efficacy. The degraders' oral bioavailability enhances accessibility and potential patient compliance, suggesting a promising alternative for advanced cases resistant to existing treatments.

The forthcoming AR inhibitors represent significant advancements in the treatment of prostate cancer, particularly for persons with CRPC. However, the effectiveness of these approaches is continually weakened by various resistance mechanisms. For instance, some AR splice variants lacking the targeted ligand-binding domain can remain active and stimulate tumour growth [84–86]. In addition, the cancer itself can produce androgens, which can continue to activate androgen receptor signalling, even in the absence of androgens in the rest of the body.

To overcome these challenges, ongoing research aims to develop combination medications that can efficiently target many pathways simultaneously, hence reducing the likelihood of resistance. To improve the long-term success of AR-targeted treatments in prostate cancer, it is crucial to investigate the underlying reasons for resistance and identify novel therapy targets [87, 88]. As our understanding of AR signalling and its role in prostate cancer deepens, it is likely that new strategies may emerge, therefore improving patient outcomes and extending survival in this prevalent and challenging disease.

Resistance mechanisms

Despite the advancements in androgen receptor (AR)-targeted therapies, resistance remains a significant challenge. Several mechanisms contribute to this phenomenon:

AR Splice Variants: Some variants lack the ligand-binding domain and can remain active even when traditional androgen signaling is inhibited. These variants can promote tumor growth independently of androgen levels [74, 80, 89].

Intratumoral Androgen Synthesis: Tumors may produce their own androgens, sustaining AR signaling despite systemic androgen deprivation [89, 90]

Alterations in Co-regulators: Changes in the expression or function of AR co-regulators can alter AR activity and contribute to resistance [9, 91].

-

B.

PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors in prostate and ovarian cancer

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is a key regulator of cell growth, survival, and metabolism, significantly influencing tumor development and progression in both prostate and ovarian cancers. Dysregulation through mutations or dysfunction of tumor suppressors such as PTEN, along with the activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR components, plays a critical role in malignant processes across various tumors [12, 92, 93].

Importantly, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) serves as an energy sensor that can influence the mTOR pathway. When cellular energy levels are low, AMPK is activated and inhibits mTOR signaling, consequently promoting catabolic processes and cell survival under stress. The interplay between AMPK and mTOR not only highlights a critical balance in cellular metabolism but also emphasizes potential therapeutic targets in cancers characterized by metabolic dysregulation. Therefore, understanding the role of AMPK alongside the mTOR pathway provides a more complete picture of the molecular mechanisms driving tumorigenesis. This relationship underscores the importance of these pathways as targets for therapeutic intervention’’.

Similarities in prostate and ovarian cancer

In both cancers, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is involved in cancer cell survival and proliferation. In prostate cancer, inhibitors targeting this pathway have shown promising results. Notably, Abiraterone, while primarily a CYP17A1 inhibitor, also reduces AR signaling, indirectly leading to decreased PI3K pathway activity and thereby conferring therapeutic benefits [94–96]. Concurrently, Ipatasertib—a selective AKT inhibitor—demonstrates efficacy in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) harboring PTEN loss, by directly inhibiting AKT activity [97, 98].

In ovarian cancer, similar activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway often stems from mutations in the PIK3CA gene. This pathway's inhibition has potential for improving treatment outcomes. Alpelisib, which selectively inhibits PI3Kα, has shown effectiveness in treating ovarian cancer patients with PIK3CA mutations, leading to reduced tumor cell proliferation and enhanced apoptosis [45, 99–102].. Furthermore, Everolimus, an mTOR inhibitor, is employed alongside other agents to increase anti-tumor efficacy, illustrating the importance of multi-targeted approaches in managing both cancers [103–105].

Unique characteristics in prostate and ovarian cancer

Despite the similarities, distinct differences exist in how these cancers respond to PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibition. In ovarian cancer, the presence of PIK3CA mutations leads to a more direct role of this pathway in tumorigenesis, whereas in prostate cancer, aberrations in AR signaling significantly influence the pathway's activation.

Recent studies are exploring combination therapies that target the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway alongside additional mechanisms to counteract resistance and enhance clinical efficacy. For instance, integrating PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors with AR inhibitors in prostate cancer, or with other targeted therapies in ovarian cancer, may provide a more complete suppression of the oncogenic pathways driving tumor progression [44, 93, 106].

Resistance mechanisms

Resistance to PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors can develop through several mechanisms, including:

Feedback Activation: Inhibition of a particular pathway may result in the compensatory activation of parallel pathways, such as the RAS or MAPK pathways. This unintended consequence can diminish the overall effectiveness of targeted therapies [74, 107].

Mutations in Pathway Components: Genetic alterations, particularly in the PIK3CA or PTEN genes, may lead to persistent activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, rendering treatments ineffective [108, 109]

Tumor Heterogeneity: The variability within tumor cell populations can produce differential responses to therapy, posing challenges for effective treatment strategies. This heterogeneity complicates the ability to predict treatment outcomes and monitor responses in clinical settings [107, 111].

-

C.

DLL3 pathway in prostate cancer

Puca et al. [112] explore the role of Delta-like protein 3 (DLL3) in neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC), a highly aggressive variant typically originating from castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). Their study reveals that DLL3 expression is significantly higher in NEPC compared to benign or localized prostate cancers and correlates with poor prognosis due to associations with aggressive characteristics and loss of the tumor suppressor gene RB1 [36]. The research also investigates the potential of the antibody–drug conjugate SC16LD6.5 (rovalpituzumab tesirine), which demonstrated impressive tumor regression in preclinical models involving DLL3-expressing CRPC-NE xenografts [112]. Clinically, a patient treated with SC16LD6.5 showed substantial tumor size reduction without disease progression after two cycles, indicating a promising therapeutic pathway for advanced NEPC [36]. The findings advocate for DLL3 as a biomarker for aggressive NEPC and suggest the potential for combination therapies and further studies on DLL3’s role in the tumor microenvironment [113, 114].

-

D.

MAPK Inhibitors in prostate and ovarian cancer

The MAPK pathway, encompassing the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling cascade, plays a pivotal role in regulating cell division and differentiation. Genetic alterations in key components such as RAS and BRAF often lead to disruptions within this pathway, significantly contributing to the tumorigenesis of both prostate and ovarian cancers [115–117].

Prostate cancer and the MAPK Pathway

Deregulation of the MAPK pathway in prostate cancer is associated with disease progression and reduced therapeutic efficacy. Current research has focused on pharmacological inhibitors of MEK, such as selumetinib, which has shown potential in laboratory studies and clinical trials. By inhibiting MEK, selumetinib effectively disrupts the signaling pathways that promote cell growth and survival, particularly in tumors harboring activating mutations within the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK cascade [94, 118]. Current studies are exploring the efficacy of selumetinib in combination with other targeted therapies to enhance treatment outcomes and combat resistance mechanisms.

Ovarian cancer and the MAPK pathway

In ovarian cancer, particularly in low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, activation of the MAPK pathway is commonly observed, often occurring alongside specific genetic alterations [119, 120]. Research has increasingly focused on targeting this pathway due to its critical role in tumor biology. Trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, has demonstrated effectiveness in treating low-grade serous ovarian cancer, leading to reduced tumor progression and improved progression-free survival among patients with relevant genetic modifications [121]. Additionally, the MEK inhibitor, cobimetinib, is currently under investigation for its synergistic effects when combined with other agents, such as PI3K inhibitors. This approach aims to improve treatment efficacy and circumvent resistance by simultaneously targeting multiple pathways, thereby impeding the cancer cells' reliance on alternative survival routes [122–124].

-

E.

PTEN pathway in prostate and ovarian cancer: similarities and unique characteristics

Overview of the PTEN pathway

The PTEN pathway serves as a critical tumor suppressor pathway that negatively regulates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling cascade. By dephosphorylating PIP3 to PIP2, PTEN inhibits hyperactivation of this pathway, which is pivotal in controlling cell proliferation and survival.

Similarities in prostate and ovarian cancer

Loss of PTEN function is a common alteration in both prostate and ovarian cancers, often resulting from mutations or chromosomal deletions. In both cancer types, the loss of PTEN leads to increased proliferation and enhanced metastatic potential [31]. The activation of the PI3K pathway, therefore, emerges as a shared mechanism driving tumorigenesis in both conditions.

Unique characteristics in prostate and ovarian cancer

While the fundamental role of the PTEN pathway is similar across these cancers, there are noteworthy distinctions. In prostate cancer, PTEN loss is associated with aggressive disease and is often linked to other genetic alterations, further complicating the molecular landscape. Conversely, in ovarian cancer, loss of function mutations in the PTEN gene occur in approximately 15% of cases, making it a significant but not the predominant driver of tumorigenesis. In addition, PTEN mutations are notably rare in other malignancies, highlighting the unique prevalence of this alteration in ovarian carcinoma [45, 48, 53, 54].

-

F.

Notch pathway: commonalities and distinctions in prostate and ovarian cancer

=

The Notch signaling pathway plays a critical role in the regulation of cell fate decisions in both prostate and ovarian cancers. It mediates various interactions with other signaling pathways, including Wnt, and is activated by its ligands, such as Jagged1, Jagged2, and Delta-like (DLL) family members. Crosstalk with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is also a notable feature that underlines its significance in tumor biology.

Similarities in the notch pathway involvement

In both prostate and ovarian cancers, aberrant activation of the Notch pathway has been identified as a key contributor to tumor progression. In ovarian carcinoma, studies have demonstrated that dysregulation of Notch signaling, often influenced by interactions with Wnt/β-catenin, is linked to the enhanced proliferation and migratory capabilities of cancer stem cells [57, 61, 62]. Similarly, in the context of prostate cancer, the Notch pathway has been found to promote tumor growth through the dysregulation of receptor and ligand expression, contributing to tumor progression [40].

Unique characteristics in prostate and ovarian cancer

While both cancers share some common mechanisms involving the Notch signaling pathway, there are notable differences in their specific molecular interactions and biological outcomes:

In Ovarian Cancer: The emphasis is on the interplay between Notch and other pathways like Wnt/β-catenin, which significantly impacts the behavior of cancer stem cells. The presence of enhanced Notch signaling is often correlated with aggressive tumor phenotypes and poor outcomes.

In Prostate Cancer: The dysregulated expression of Notch receptors (Notch1-4) and their corresponding ligands leads to distinct outcomes in terms of tumor differentiation and progression. This dysregulation is associated with various clinical manifestations of prostate cancer, including treatment resistance.

-

G.

Wnt/β-Catenin pathway in prostate and ovarian cancer

Similarities in prostate and ovarian cancer

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays a crucial role in regulating cell proliferation and differentiation, primarily through the stabilization and nuclear translocation of β-catenin upon Wnt ligand binding. This activation is essential for promoting tumor growth in both prostate and ovarian cancers.

In prostate cancer, abnormal activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, often due to mutations or dysregulated Wnt production, is implicated in disease initiation and progression. Specifically, alterations in the components of this pathway have been shown to facilitate tumor metastasis [30].

Similarly, in ovarian cancer, particularly endometrioid cancers, dysregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is also associated with tumorigenesis. Numerous studies identify mutations in β-catenin and other key pathway components in approximately 30% of endometrioid ovarian tumors. These mutations contribute to increased treatment resistance and promote neovascularization, which are critical factors affecting disease outcome [57–60].

Unique characteristics of prostate and ovarian cancer

While both cancer types share common alterations in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, distinct characteristics are noteworthy. In prostate cancer, the role of the pathway seems more pronounced in the initiation and progression of disease, suggesting that targeting the Wnt pathway may be a viable therapeutic approach.

In contrast, in ovarian endometrioid cancers, the mutations and dysregulation not only contribute to tumor growth but also significantly impact the resistance to treatments, highlighting the need for tailored therapeutic strategies that address the specific mechanisms of Wnt pathway involvement in ovarian cancer.

BRCA1/2 pathway in prostate and ovarian cancer

Similarities in prostate and ovarian cancer

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are critical genes that play essential roles in DNA repair and transcription regulation. Mutations in these genes are associated with hereditary cancer syndromes, particularly in ovarian cancer. In both prostate and ovarian cancers, germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 lead to an increased risk of developing malignancies, reflecting similar underlying mechanisms in tumorigenesis.

Unique characteristics of prostate and ovarian cancer

Ovarian Cancer: Germline mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are significant risk factors for ovarian cancer. These mutations are known to substantially elevate the likelihood of developing ovarian cancer, particularly type II ovarian carcinomas. Women with BRCA1 mutations face a cumulative risk of approximately 44% to 49% of developing ovarian cancer by age 80, with some studies suggesting a risk as high as 60% in certain populations [129, 130]. For those with BRCA2 mutations, the cumulative risk is around 17% to 21%, with estimates reaching up to 30% in specific cohorts [129, 130]. These figures indicate that while both BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations significantly increase ovarian cancer risk, BRCA1 mutations confer a higher risk compared to BRCA2. The majority of ovarian cancers associated with these mutations are primarily of the type II variety, which is generally more aggressive and has poorer outcomes compared to type I ovarian cancers. This association underscores the importance of genetic screening and counseling for women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer, particularly those belonging to high-risk groups.

Prostate Cancer: BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are well-known genetic factors linked to an increased risk of several cancers, notably breast and ovarian cancers in women. However, their role in prostate cancer, while less pronounced, is significant, particularly for men carrying BRCA2 mutations. Men with BRCA2 mutations face a 20% to 60% lifetime risk of developing prostate cancer, significantly higher than the general population risk of approximately 16% [131]. Studies indicate that BRCA2 carriers are more likely to develop aggressive forms of prostate cancer and experience earlier onset, often before age 65 [132, 133]. The mutation is associated with a 3- to 8.6-fold increase in prostate cancer risk compared to non-carriers [131]. The lifetime risk for men with BRCA1 mutations is estimated at about 7% to 29%, which is still above the general population risk but less impactful than BRCA2 [131]. Evidence suggests that while the overall risk increase is modest, BRCA1 carriers may also experience more aggressive disease if they do develop prostate cancer [3, 4]. The mechanisms by which BRCA mutations influence prostate cancer development are not fully understood and warrant further investigation. Current research suggests that defective BRCA genes compromise DNA repair mechanisms, leading to increased tumor formation as DNA damage accumulates [134].

Upstream regulators of key signaling pathways in cancer

The complex nature of cancer biology makes it essential to understand the regulation of signaling pathways, as these pathways play a pivotal role in cancer progression, metastasis, and resistance to therapy. Each signaling pathway has specific upstream regulators that can either activate or inhibit its activity, leading to distinct outcomes in cellular behavior. Here, we explore several major signaling pathways in cancer and their respective upstream regulators.

Androgen receptor signaling pathway

The androgen receptor (AR) signaling pathway is for prostate cancer progression, where its regulation is primarily driven by:

Testosterone: Testosterone, the principal male sex hormone, activates androgen receptors in prostate cells, which promotes their growth and survival. This activation is crucial as it drives the proliferation of prostate cancer cells, making testosterone a key player in the disease's development and progression. The conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) enhances this effect, as DHT binds more effectively to the AR, leading to significant cellular responses that facilitate tumor growth [135–137].

AR Co-regulators (e.g., SRC-1, SRC-2): AR co-regulators, such as SRC-1 and SRC-2, are proteins that enhance the transcriptional activity of the androgen receptor. These co-regulators are essential for modulating AR function and can significantly influence prostate cancer progression. For instance, increased expression of these coactivators has been linked to heightened AR activity even in low-androgen environments, contributing to the resistance observed in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) [9, 136]. The interplay between AR and its co-regulators is complex; alterations in their expression can lead to changes in AR ligand specificity and overall transcriptional activity, further fueling tumor progression [9, 135].

APUC Genes: The regulation of androgen receptor (AR) signaling is intricately influenced by a unique family of genes known as APUC genes, which are responsible for crucial processes including androgen production, uptake, and conversion. Genetic variants within these APUC genes, such as HSD3B1, have been implicated in modulating the therapeutic responses of patients suffering from metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) when treated with androgen-targeted therapies. Studies show that these genetic variants can result in elevated levels of biologically active androgens. This increase in active androgen levels has a direct impact on enhancing AR signaling pathways, which in turn can promote cancer progression and exacerbate the malignancy in mCRPC patients [138].

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

Growth Factors: The PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway often experiences activation through the engagement of growth factors, most notably insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). These growth factors activate receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), triggering a complex orchestration of signaling cascades that are critical for not only cancer stem cell maintenance but also for the overall tumorigenicity of cancer cells. As such, several upstream components can significantly influence the activation of this pivotal pathway, which has vast implications for cellular growth and survival in cancer biology [139, 140].

MicroRNAs: Specific microRNAs have been identified as key modulators of gene expression concerning various components within the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. The presence and activity of these microRNAs can have profound effects on tumor growth and development, as well as on the resilience of cancer cells against therapeutic interventions. Their regulatory roles illustrate the intricate balance between microRNA-mediated control and tumor dynamics [139, 140].

MAPK Pathway

Cytokines and Growth Factors: The MAPK signaling pathway is activated by a diverse array of extracellular signals, including cytokines and various growth factors. These signals interact with receptor tyrosine kinases or G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), initiating a signaling cascade that leads to the activation of specific MAPK proteins such as ERK, JNK, and p38 MAPK. This pathway is integral to essential cellular processes, including cell proliferation and differentiation, highlighting its vital role in oncogenesis and the maintenance of malignant phenotypes [141].

Small G Proteins: Critical signaling mechanisms within the MAPK cascade are facilitated by small G proteins, notably Ras, which serve as important relay points for signals emanating from RTKs and GPCRs. Their function is essential in ensuring the proper transmission of these signals to the MAPK cascade, thus underscoring their role as key upstream regulators in this pathway [127, 141]. Mutations in Ras proteins can lead to constitutive activation of the MAPK pathway, driving tumorigenesis [142, 143].

PTEN Pathway

MicroRNAs: Various microRNAs have been discovered that target PTEN (Phosphatase and tensin homolog) directly, thus regulating its expression levels. These interactions can significantly influence downstream signaling mechanisms, particularly those involving the PI3K/Akt pathway. The modulation of PTEN through microRNAs is crucial, as it can impact tumor growth and the metastatic potential of different cancers, offering insights into therapeutic targets for intervention [144].

Transcription Factors: The expression of PTEN is also subject to modulation by certain transcription factors. These factors, particularly those responsive to hypoxic conditions, can lead to the downregulation of PTEN expression. This reduction enhances the survival of cancer cells under low oxygen scenarios, illustrating the intricate interplay between transcriptional regulation and tumorigenesis in cancer [144, 145].

Wnt/β-Catenin pathway

Wnt Ligands: The Wnt signaling pathway is predominantly activated through the binding of Wnt ligands to Frizzled receptors. This engagement triggers a cascade of events that stabilize β-catenin, a central player in the Wnt pathway. The regulatory dynamics of this process are finely tuned by upstream components, including secreted Wnt inhibitors such as DKK1 (Dickkopf-1) and SFRP (Secreted Frizzled Related Protein), which play a crucial role in modulating Wnt signaling and its associated biological outcomes [146].

Notch pathway

The activation of Notch signaling occurs through the direct interactions between Notch receptors and their respective ligands, such as Jagged or Delta. The regulation of these ligands is pivotal, as it can substantially influence Notch signaling activity, which is crucial for facilitating cancer progression and the maintenance of stem-like properties within tumors [147].

BRCA1/2 pathway

DNA Damage Response Proteins: The BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathways are subject to regulation by a variety of upstream DNA damage response proteins that play essential roles in sensing DNA double-strand breaks. These proteins recruit BRCA1 and BRCA2 to sites of DNA damage, facilitating crucial repair processes. The effective regulation of these pathways is vital for maintaining genomic stability within the cell, and any dysfunction in this mechanism can have significant ramifications for cancer development and progression [148].

Recent findings

New research has uncovered additional complexities within these signaling pathways. For instance:

RAB4A has been identified as a master regulator that influences multiple signaling pathways, including Notch and Wnt/β-catenin [149]. Its modulation may affect cancer stemness and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), significantly contributing to tumor heterogeneity and resilience [149, 150].

The interplay between pathways, such as PI3K/AKT and MAPK, complicates therapeutic targeting [151]. Their interconnected nature suggests that targeting a single pathway might not be sufficient to inhibit cancer progression effectively.

Recent research by Ku et al. [152] sheds light on the crucial role of Notch signaling in advanced prostate cancer, with a particular emphasis on neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC). One of the primary discoveries of the study is that Notch signaling acts as a tumor suppressor in NEPC. The research reveals that Notch-2 expression inhibits neuroendocrine differentiation, thereby restraining tumor growth. Specific genes associated with neuroendocrine characteristics, such as DLL3 and ASCL1, were suppressed in the presence of Notch signaling, while the development of prostate luminal lineage was promoted. This finding suggests that enhancing Notch signaling could provide a therapeutic strategy to counteract the aggressive features characteristic of NEPC. The study further highlights the significant impact of Notch signaling on the immune microenvironment within prostate cancer. Tumors exhibiting active Notch signaling demonstrated enhanced infiltration of various immune cells, including dendritic cells, macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, and neutrophils. Moreover, there was an observable upregulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II molecules, pointing to a more immunogenic tumor profile. This enhancement in immune cell presence suggests that Notch signaling not only helps inhibit tumor progression but may also improve the immune response against prostate cancer. An intriguing aspect of the research is the differential roles that Notch signaling plays across various prostate cancer types. While the study establishes Notch as a tumor suppressor in NEPC, it also notes its potential oncogenic roles in other forms, such as adenocarcinoma. This dual function underscores the complexity of targeting Notch signaling therapeutically, as interventions may have disparate effects depending on the specific cancer subtype involved. The insights provided by Ku et al. [152] pave the way for novel therapeutic approaches targeting the Notch signaling pathway, especially in NEPC. Current clinical trials are investigating T-cell engager therapies that target DLL3, promising potential new treatment options for patients facing this formidable cancer type. As research progresses, understanding the nuances of Notch signaling could be pivotal in designing effective, tailored therapies that improve outcomes for patients with advanced prostate cancer.

The study ‘‘Lineage-specific canonical and non-canonical activity of EZH2 in advanced prostate cancer subtypes" by Venkadakrishnan et al. [153] examines the enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) in prostate cancer, particularly in prostate adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC). It finds that EZH2 has both canonical functions, mainly involved in gene repression within the PRC2 complex in adenocarcinoma, and non-canonical activities in NEPC that activate transcription related to therapy resistance. Key mechanisms involve the regulation of EZH2 stability by protein kinase PKCλ/ι, impacting cancer phenotype and suggesting novel therapeutic targets for aggressive prostate cancer forms.

Challenges and future directions in targeted therapy

Although targeted medicines such as MAPK inhibitors have promise for the treatment of prostate and ovarian malignancies, there are still significant obstacles that need to be addressed. An important problem is the activation of parallel circuits that hinders the long-term efficiency of feedback. Cancer cells frequently adjust by stimulating compensatory signalling pathways, which enable them to sustain their ability to multiply and survive. Drug resistance, including secondary mutations and changes in signalling networks, also diminishes the effectiveness of MAPK inhibitors.

To tackle these problems, additional research and the implementation of combined techniques are necessary. The integration of MAPK inhibitors with other targeted medicines, such as PI3K or AKT inhibitors, results in a thorough obstruction of oncogenic signalling networks. Gaining knowledge of resistance mechanisms and developing biomarkers for patient classification are essential for optimising treatments and enhancing results.

The presence of diverse tumour characteristics makes it challenging to discover targets that are universally effective and to determine the efficacy of therapies that target a specific agent. Therefore, a personalised medicine strategy is necessary. Challenges arise from side effects and toxicity, necessitating the creation of inhibitors that are more specific and dose regimens that are optimised.

Major obstacles include the need for clinical studies and dependable biomarkers to classify patients and predict their response. There is a need for improved clinical trials that use biomarkers to select patients and enhance the effectiveness of focused therapy.

Potential future avenues of research involve the creation of multi-target inhibitors, innovative methods of drug administration, and the exploration of immunotherapy combinations. Progress in comprehending the tumour microenvironment and cancer stem cells will provide novel opportunities for therapy. Sustained research and innovation are crucial in order to surpass existing constraints and enhance results for individuals diagnosed with prostate and ovarian malignancies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, reproductive cancers, particularly prostate and ovarian cancer, are driven by complex molecular pathways that involve genetic alterations, dysregulated signaling cascades, and epigenetic modifications. Understanding these pathways is crucial for accurate diagnosis, personalized treatment, and the development of novel therapeutic strategies. By unraveling the molecular underpinnings of these cancers, we can identify actionable targets and develop targeted therapies that specifically inhibit the growth and progression of reproductive tumors. Future research in molecular medicine aims to elucidate the interplay between genetic and epigenetic factors, explore the role of non-coding RNAs, and investigate the impact of the tumor microenvironment on molecular pathways. By gaining a comprehensive understanding of the molecular landscapes of reproductive cancers, we can pave the way for precision medicine approaches that improve patient outcomes and ultimately reduce the burden of these devastating diseases.

Acknowledgements

We thank the reviewers for their helpful comments.

Author contributions

Mega Obukohwo Oyovwi & Ayodeji FolorunshoAjayi participated in sorting and conceptualizing the manuscript and wrote the manuscript. Ayodeji Folorunsho Ajayi, Mega Obukohwo Oyovwi, & Oyedayo Phillips Akano organized the literature and presented ideas. Mega Obukohwo Oyovwi read and approved the submitted version. Mega Obukohwo Oyovwi, Ayodeji Folorunsho Ajayi, Oyedayo Phillips Akano, Grace Bosede Akanbi, & Florence Bukola Adisa is responsible for the contribution. The author contributed to the revision of the manuscript, read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bisoyi P. A brief tour guide to cancer disease understanding cancer. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown JS, Amend SR, Austin RH, Gatenby RA, Hammarlund EU, Pienta KJ. Updating the definition of cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2023;21(11):1142–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoadley KA, Yau C, Hinoue T, Wolf DM, Lazar AJ, Drill E, et al. Cell-of-origin patterns dominate the molecular classification of 10,000 tumors from 33 types of cancer. Cell. 2018;173(2):291–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ke Q, Dinalankara W, Younes L, Geman D, Marchionni L. Efficient representations of tumor diversity with paired DNA-RNA aberrations. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021;17(6): e1008944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gargiulo G, Serresi M, Marine JC. Cell states in cancer: drivers, passengers, and trailers. Cancer Discov. 2024;14(4):610–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Musekiwa A, Moyo M, Mohammed M, Matsena-Zingoni Z, Twabi HS, Batidzirai JM, et al. Mapping evidence on the burden of breast, cervical, and prostate cancers in Sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. Front Public Health. 2022;16(10): 908302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang W, Cao G, Wu F, Wang Y, Liu Z, Hu H, et al. Global burden of prostate cancer and association with socioeconomic status, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2023;13(3):407–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heinlein CA, Chang C. Androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Endocr Rev. 2004;25(2):276–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lonergan PE, Tindall DJ. Androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer development and progression. J Carcinog. 2011;10:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng J, Li L, Zhang N, Liu J, Zhang L, Gao H, Wang G, Li Y, Zhang Y, Li X, Liu D. Androgen and AR contribute tobreast cancer development and metastasis: an insight of mechanisms. Oncogene. 2017;36(20):2775–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Glaviano A, Foo AS, Lam HY, Yap KC, Jacot W, Jones RH, et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2023;22(1):138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zakari S, Ekenwaneze CC, Amadi EC, AbuHamdia A, Ogunlana OO. Unveiling the latest insights into androgen receptors in prostate cancer. Int J Med Biochem. 2024;7(2):20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crumbaker M, Khoja L, Joshua AM. AR signaling and the PI3K pathway in prostate cancer. Cancers. 2017;9(4):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Momenimovahed Z, Tiznobaik A, Taheri S, Salehiniya H. Ovarian cancer in the world: epidemiology and risk factors. Int J Womens Health. 2019;30(11):287–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(No authors listed). Radon in homes and risk of lung cancer: collaborative analysis of individual data from 13 European case-control studies. BMJ. 2000;321(7257):223–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng F, Liao M, Qin R, Zhu S, Peng C, Fu L, et al. Regulated cell death (RCD) in cancer: key pathways and targeted therapies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wani AK, Akhtar N, Mir TU, Singh R, Jha PK, Mallik SK, et al. Targeting apoptotic pathway of cancer cells with phytochemicals and plant-based nanomaterials. Biomolecules. 2023;13(2):194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sadikovic B, Al-Romaih K, Squire JA, Zielenska M. Cause and consequences of genetic and epigenetic alterations in human cancer. Curr Genomics. 2008;9(6):394–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grazioli E, Dimauro I, Mercatelli N, Wang G, Pitsiladis Y, Di Luigi L, et al. Physical activity in the prevention of human diseases: role of epigenetic modifications. BMC Genomics. 2017;18:111–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fardi M, Solali S, Hagh MF. Epigenetic mechanisms as a new approach in cancer treatment: an updated review. Genes Dis. 2018;5(4):304–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacob A, Raj R, Allison DB, Myint ZW. Androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer and therapeutic strategies. Cancers. 2021;13(21):5417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choudhury AD. PTEN-PI3K pathway alterations in advanced prostate cancer and clinical implications. Prostate. 2022;82:S60-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugawara T, Nevedomskaya E, Heller S, Böhme A, Lesche R, von Ahsen O, et al. Dual targeting of the androgen receptor and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways in prostate cancer models improves antitumor efficacy and promotes cell apoptosis. Mol Oncol. 2024;18(3):726–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fares J, Fares MY, Khachfe HH, Salhab HA, Fares Y. Molecular principles of metastasis: a hallmark of cancer revisited. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yip HY, Papa A. Signaling pathways in cancer: therapeutic targets, combinatorial treatments, and new developments. Cells. 2021;10(3):659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pawaskar R, Mahajan N, Wangoo E, Khan W, Bailey J, Vines R. Staff perceptions of the management of mental health presentations to the emergency department of a rural Australian hospital: qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhat GR, Sethi I, Sadida HQ, Rah B, Mir R, Algehainy N, et al. Cancer cell plasticity: from cellular, molecular, and genetic mechanisms to tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2024;43(1):197–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shtivelman E, Beer TM, Evans CP. Molecular pathways and targets in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5(17):7217–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koushyar S, Meniel VS, Phesse TJ, Pearson HB. Exploring the Wnt pathway as a therapeutic target for prostate cancer. Biomolecules. 2022;12(2):309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hollander M, Blumenthal G, Dennis P. PTEN loss in the continuum of common cancers, rare syndromes and mouse models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vickman RE, Franco OE, Moline DC, Vander Griend DJ, Thumbikat P, Hayward SW. The role of the androgen receptor in prostate development and benign prostatic hyperplasia: a review. Asian J Urol. 2020;7(3):191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Montalto G, Cervello M, et al. Mutations and deregulation of Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR cascades which alter therapy response. Oncotarget. 2012;3(9):954–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elzenaty RN, Du Toit T, Flück CE. Basics of androgen synthesis and action. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;36(4): 101665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawaf RR, Ramadan WS, El-Awady R. Deciphering the interplay of histone post-translational modifications in cancer: Co-targeting histone modulators for precision therapy. Life Sci. 2024;13: 122639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beltran H, Demichelis F. Therapy considerations in neuroendocrine prostate cancer: what next? Endocr Relat Cancer. 2021;28(8):T67-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martini M, Ciraolo E, Gulluni F, Hirsch E. Targeting PI3K in cancer: any good news? Front Oncol. 2013;8(3):108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang X, Chen S, Asara JM, Balk SP. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway activation in phosphate and tensin homolog (PTEN)-deficient prostate cancer cells is independent of receptor tyrosine kinases and mediated by the p110β and p110δ catalytic subunits. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(20):14980–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarker D, Reid AH, Yap TA, De Bono JS. Targeting the PI3K/AKT pathway for the treatment of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(15):4799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi Q, Xue C, Zeng Y, et al. Notch signaling pathway in cancer: from mechanistic insights to targeted therapies. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ricciardelli C, Oehler MK. Diverse molecular pathways in ovarian cancer and their clinical significance. Maturitas. 2009;62(3):270–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fruman DA, Chiu H, Hopkins BD, Bagrodia S, Cantley LC, Abraham RT. The PI3K pathway in human disease. Cell. 2017;170(4):605–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gasparri ML, Bardhi E, Ruscito I, Papadia A, Farooqi AA, Marchetti C, et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in ovarian cancer treatment: are we on the right track? Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2017;77(10):1095–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu L, Wei J, Liu P. Attacking the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway for targeted therapeutic treatment in human cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;85:69–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rinne N, Christie EL, Ardasheva A, Kwok CH, Demchenko N, Low C, et al. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in epithelial ovarian cancer, therapeutic treatment options for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2021;4(3):573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lien EC, Dibble CC, Toker A. PI3K signaling in cancer: beyond AKT. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2017;45:62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ortega MA, Asúnsolo Á, Leal J, Romero B, Alvarez-Rocha MJ, Sainz F, et al. Implication of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in the process of incompetent valves in patients with chronic venous insufficiency and the relationship with aging. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:1495170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Polivka J Jr, Janku F. Molecular targets for cancer therapy in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;142(2):164–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hendrikse CS, Theelen PM, Van Der Ploeg P, Westgeest HM, Boere IA, Thijs AM, et al. The potential of RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK (MAPK) signaling pathway inhibitors in ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2023;171:83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kotsopoulos IC, Papanikolaou A, Lambropoulos AF, Papazisis KT, Tsolakidis D, Touplikioti P, et al. Serous ovarian cancer signaling pathways. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24(3):531–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hew KE, Miller PC, El-Ashry D, Sun J, Besser AH, Ince TA, et al. MAPK activation predicts poor outcome and the MEK inhibitor, selumetinib, reverses antiestrogen resistance in ER-positive high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(4):935–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tolcher AW, Peng W, Calvo E. Rational approaches for combination therapy strategies targeting the MAP kinase pathway in solid tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17(1):3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luongo F, Colonna F, Calapà F, Vitale S, Fiori ME, De Maria R. PTEN tumor-suppressor: the dam of stemness in cancer. Cancers. 2019;11(8):1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nero C, Ciccarone F, Pietragalla A, Scambia G. PTEN and gynecological cancers. Cancers. 2019;11(10):1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Osman MA. Genetic cancer ovary. Clin Ovarian Other Gynecol Cancer. 2014;7(1–2):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barili V, Ambrosini E, Bortesi B, Minari R, De Sensi E, Cannizzaro IR, et al. Genetic basis of breast and ovarian cancer: approaches and lessons learnt from three decades of inherited predisposition Testing. Genes. 2024;15(2):219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nowicki A, Kulus M, Wieczorkiewicz M, Pieńkowski W, Stefańska K, Skupin-Mrugalska P, et al. Ovarian cancer and cancer stem cells—cellular and molecular characteristics, signaling pathways, and usefulness as a diagnostic tool in medicine and oncology. Cancers. 2021;13(16):4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nguyen VH, Hough R, Bernaudo S, Peng C. Wnt/β-catenin signalling in ovarian cancer: insights into its hyperactivation and function in tumorigenesis. J Ovarian Res. 2019;12:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matsui WH. Cancer stem cell signaling pathways. Medicine. 2016;95(1S):S8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Teeuwssen M, Fodde R. Wnt signaling in ovarian cancer stemness, EMT, and therapy resistance. J Clin Med. 2019;8(10):1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katoh M, Katoh M. Precision medicine for human cancers with Notch signaling dysregulation. Int J Mol Med. 2020;45(2):279–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bocchicchio S, Tesone M, Irusta G. Convergence of Wnt and Notch signaling controls ovarian cancer cell survival. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(12):22130–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harris WP, Mostaghel EA, Nelson PS, Montgomery B. Androgen deprivation therapy: progress in understanding mechanisms of resistance and optimizing androgen depletion. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2009;6(2):76–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aragon-Ching JB, Dahut WL. Novel androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in the treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Drug Discov Today Ther Strateg. 2010;7:31–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Crawford ED, Heidenreich A, Lawrentschuk N, Tombal B, Pompeo AC, Mendoza-Valdes A, et al. Androgen-targeted therapy in men with prostate cancer: evolving practice and future considerations. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2019;22(1):24–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Desai K, McManus JM, Sharifi N. Hormonal therapy for prostate cancer. Endocr Rev. 2021;42(3):354–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Coutinho I, Day TK, Tilley WD, Selth LA. Androgen receptor signaling in castration-resistant prostate cancer: a lesson in persistence. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016;23(12):T179–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen B, Wang H, Miao L, Lin X, Chen Q, Jing L, Lu X. NOTCH pathway genes in ovarian cancer: Clinical significance and associations with immune cell infiltration. Front Biosci. 2023;28(9):220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guerrero J, Alfaro IE, Gómez F, Protter AA, Bernales S. Enzalutamide, an androgen receptor signaling inhibitor, induces tumor regression in a mouse model of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate. 2013;73(12):1291–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Merseburger AS, Haas GP, von Klot CA. An update on enzalutamide in the treatment of prostate cancer. Ther Adv Urol. 2015;7(1):9–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]