Abstract

Background

Upper extremity rehabilitation in persons with stroke should be dose-dependent and task-oriented. Virtual reality (VR) has the potential to be used safely and effectively in home-based rehabilitation. This study aimed to investigate the effects of home-based virtual reality upper extremity rehabilitation in persons with chronic stroke.

Methods

This was a single-blind, randomized, controlled trial conducted at two centers. The subjects were 14 outpatients with chronic stroke more than 6 months after the onset of the stroke. The participants were randomly divided into two groups. The intervention group (n = 7) performed a home rehabilitation program for the paretic hand (30 min/day, five days/week) using a VR device (RAPAEL Smart Glove™; NEOFECT Co., Yung-in, Korea) for four weeks. The control group (n = 7) participated in a conventional home rehabilitation program at the same frequency. All participants received outpatient occupational therapy once a week during the study period. The outcome measures included the Fugl-Meyer Assessment of upper extremity motor function (FMA-UE), Motor Activity Log-14 (MAL), Jebsen-Taylor Hand Function Test (JTT), and Box and Block Test (BBT) scores.

Results

All 14 participants completed the study. Compared to the control group, the intervention group showed more significant improvements in FMA-UE (p = 0.027), MAL (p = 0.014), JTT (p = 0.002), and BBT (p = 0.014). No adverse events were observed during or after the intervention.

Conclusion

Compared to a conventional home program, combining a task-oriented virtual reality home program and outpatient occupational therapy might lead to greater improvements in upper extremity function and the frequency of use of the paretic hand.

Trial registration: This study was registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trial Registry in Japan (Unique Identifier: UMIN000038469) on November 1, 2019; https://center6.umin.ac.jp/cgi-open-bin/ctr/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000043836.

Keywords: Stroke, Virtual reality, Upper extremity, Rehabilitation, Home-based training, Occupational therapy

Introduction

Upper extremity motor function is critical for independence in activities of daily living (ADL) in persons with hemiparetic stroke. A previous study showed that upper extremity motor function is impaired in more than 85% of persons with stroke [1]. Persons with chronic stroke tend to have difficulty using their paretic hand in ADL. Functional recovery of the paretic upper extremity requires dose-dependent and task-specific rehabilitation [2]. Improvement at the level of activities after stroke is driven by neural repair and by learning compensation strategies [3]. Motor learning is essential for skill reacquisition. Key elements in motor learning are considered to include massed practice/repetitive practice, task-specific practice, increasing difficulty, multisensory stimulation, and feedback [4]. This indicates that motor learning requires a sufficient amount of rehabilitation training. Additionally, the content of rehabilitation training should be task-oriented [5]. Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT), an approach using active task-oriented practice or behavioral strategies for the paretic upper extremity, is practical and based on both these principles [6]. Recently, functional electrical stimulation, robotics, and brain-machine interface have been applied to persons with moderate and severe paresis, according to dose and task-dependent principles [7–10].

However, many persons with chronic stroke have limited opportunities to receive sufficient doses of rehabilitation because of constraints related to therapist resources and high costs. Hence, many recent researches have focused on rehabilitation using virtual reality (VR) [11–13]. Currently, task-oriented practice with VR devices is available as a medical device [14]. Many reports using VR devices have positioned VR as an attractive and easy-to-motivate tool, as it allows users to engage in enjoyable, game-like exercises while receiving direct feedback [15]. Further, VR rehabilitation offers the advantage of incorporating repeated task-oriented exercises tailored to the person's abilities in home exercise.

A previous systematic review reported that VR rehabilitation improved upper extremity function in persons with stroke [16]. In addition, VR devices exhibit considerable potential in home rehabilitation due to their compact size, safety, and ease of management, as no external force is used.

There is also evidence from previous studies supporting the effectiveness of home-based VR programs for upper extremity rehabilitation. Cramer et al. conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing activity-based training delivered in traditional in-clinic settings and through home-based telerehabilitation for individuals with post-stroke arm impairments. Their findings demonstrated significant improvements in arm motor function in both groups [17]. Qui et al. reported measurable improvements in upper extremity function after using their Home-Based Virtual Rehabilitation System with minimal supervision for individuals with upper limb disabilities caused by stroke [18]. Additionally, Gauthier et al. compared self-practice, telerehabilitation, conventional rehabilitation, and constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT). They found that telerehabilitation achieved outcomes equivalent to CIMT, despite requiring only one-fifth of the therapist's involvement time [19]. All of these studies utilized video game-based VR tasks. However, the efficacy of a task-oriented upper extremity home program using VR, along with periodic professional advice for persons with chronic stroke remains unclear. This study aimed to investigate the effects of home-based task-oriented VR upper extremity rehabilitation in persons with chronic stroke.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study was a two-center, single-blind, randomized, controlled study. The participants were recruited from the outpatient clinics of the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine of Juntendo University Hospital or Juntendo Tokyo Koto Geriatric Medical Center from November 2019 to June 2023.

The inclusion criteria of this study were: (1) age ≧ 20 years; (2) more than 6 months since stroke onset; (3) unilateral upper extremity dysfunction after stroke; and (4) muscle strength in wrist joint flexion or extension, rotation and extension of the forearm, and hand flexion and extension of the fingers of at least Medical Research Council grade 2 or higher.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) mental dysfunction that would interfere with participation in this study (Mini-Cog test [20] results within the normal range); (2) severe aphasia that made communication difficult; (3) severe pain that prevented upper extremity rehabilitation; (4) previous neurological disease causing motor impairment; and (5) contraindications or prohibitions to the use of the VR device (presence of open wounds, skin infections, skin conditions on the hand undergoing treatment, a Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS) score of 3 or higher, or injuries to the treatment area).

Participants were randomly assigned to the VR group or control group using a computerized substitution block method (size 6).

Intervention

Participants in the each group were asked to practice the home program for 30 min a day, five days a week, for 4 weeks. The VR group performed the rehabilitation program by wearing a VR device (RAPAEL Smart Glove™; NEOFECT Co., Yung-in, Korea) on their paretic hand after being taught how to use the device by an occupational therapist (Fig. 1). The device consists of a strain gauge, accelerometer, and goniometer, which measure the movements of the forearm, wrist, and finger. Using this Smart Glove, participants move their hands on the screen and play tasks that simulate daily living activities (e.g., cutting food with a knife, catching a ball, pouring water from a bottle into a glass, etc.).The tasks were classified based on the movement areas, allowing for exercises such as forearm pronation and supination, wrist flexion and extension, radial and ulnar deviation, and finger flexion and extension. Before starting each task, calibration was performed to determine the range of motion for the specific movement area. Consequently, participants were required to repeatedly perform movements within their initial achievable range, aligned with the timing and speed of the tasks. Feedback was provided based on the success or failure of the tasks. Movement data, such as range of motion, movement duration, and task success rate, were recorded by the device.

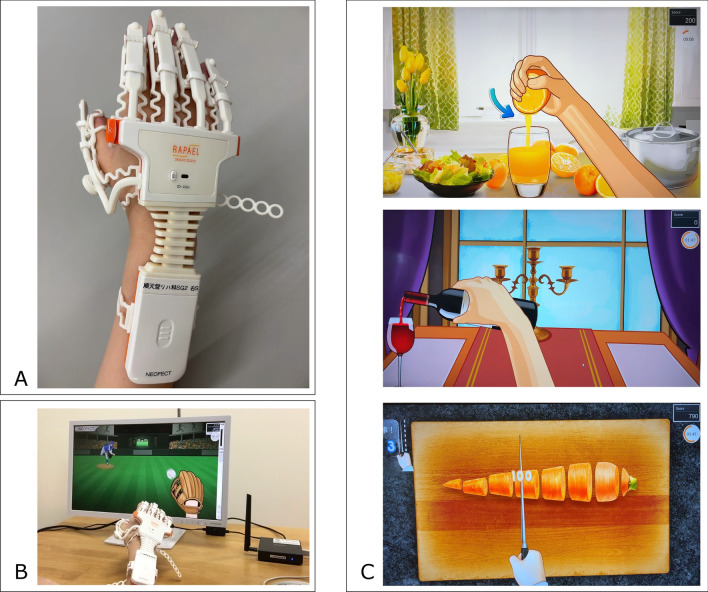

Fig. 1.

Images of the VR device used. A A sensor-powered device was attached to each finger using a plastic hook (the participant could attach and detach it himself/herself). B Image of use: Sensors detect actual movements and perform tasks on the screen. C Image of the task: More than 40 tasks were performed in the training mode

For example, one of the tasks involved squeezing an orange (Fig. 1C, top), requiring repeated finger flexion and extension, as well as sustained grasping or releasing. Similarly, the middle section involved forearm pronation and supination to pour wine, while the lower section included wrist radial and ulnar deviation to simulate cutting food. Each task was performed for 3 min, and various tasks were combined to create a total practice duration of 30 min. The VR home program was performed only on the paretic hand.

VR is classified mainly into two types: immersive and non-immersive [21]. Immersive VR creates a highly engaging environment by using technologies like head-mounted displays or large-screen projections to provide users with a strong sense of presence. These systems simulate real-world objects and events in three-dimensional spaces, enhancing motor relearning by fully involving the user's visual, auditory, and sometimes tactile senses. Non-immersive VR allows users to interact with a virtual environment displayed on a standard computer screen, often with input devices like joysticks, computer mice, or haptic tools. Unlike immersive systems, it does not fully surround the user, providing a lower sense of presence while still offering interactive training opportunities. In the present study, a non-immersive device was chosen for safety reasons because participants were conducting the program alone. Since no external force is involved, there is little risk of pain or injury during the exercise, and the system can be safely used at home. Each VR rehabilitation task was adjusted according to the participant's range of motion to enable safe and repetitive practice at home. The range of motion of the joints involved in the exercises was measured before the start of each task, allowing the tasks to be adjusted to the participant's current condition and enabling safe and repetitive practice at home. If participants felt that the tasks were too easy to perform or if improvements in their movements were observed, occupational therapists proposed task modifications or adjustments to the difficulty level during outpatient therapy sessions.

In the control group, the occupational therapist planned forearm, wrist, and finger home exercises according to each participant's condition and treatment goal. The participants in the control group were provided with a pamphlet containing approximately five repetitive single-joint upper limb exercises suggested by an occupational therapist. Based on the pamphlet, they performed the exercises as a home program. Participants in the control group were asked to practice the conventional home program without using the VR device for the same amount of time and at the same frequency as the VR group. In both groups, the content of the exercises was instructed by the occupational therapist during weekly outpatient occupational therapy sessions for four weeks and the participants independently performed the home program.

Outcome measures

The participants were asked to record the time spent performing home exercises. Exercise time was documented using a self-reported log, where participants recorded the date and duration of each exercise session during the intervention period. For the VR group, exercise time was also recorded within the device, ensuring that the reported duration matched the actual time spent exercising. For the control group, exercise time was based on self-reported durations. The effects on upper extremity function and activity were assessed three times: before the start of the intervention program (before), post the end of the intervention program (post), and 4 weeks later post the end of the intervention program (post 4w). All other outcome measures were assessed inside the hospital by either a physician or an occupational therapist who was unaware of the assignment of all subjects. The primary outcome was the Fugl-Meyer assessment of upper extremity motor function score (FMA-UE) [22]. Further, the Jebsen-Taylor Hand Function Test (JTT) [23], Box and Block Test (BBT) [24], and amount of use score in Motor Activity Log-14 (MAL-14 AoU) [25] were assessed as secondary outcomes. The MAL includes two components: the amount of use (AoU), which evaluates the frequency of paretic hand use, and the quality of movement (QoM), which assesses the ease of use. QoM is more suitable for individuals with mild to moderate paresis [25], AoU was selected in this study to evaluate changes in usage frequency. The JTT assessed (1) turning over five cards, (2) picking up and moving small objects (bottle lid (crown), paper clip, coin), (3) eating (scooping beans with a spoon), (4) stacking game pieces, (5) lifting an empty can, and (6) lifting and moving a heavy can (450 g) can. The upper limit of measurement for each subtest was 180 s.

The FMA-UE [26], JTT [27], BBT [28], and MAL-14 AoU [25] have all been previously examined for reliability and validity, and are used to assess upper extremity function in people with stroke. The physician and occupational therapist monitored participants for adverse events during the intervention. The assessments were performed by physicians or occupational therapists who were blind to the participant's group assignment. The physicians and occupational therapists who participated in the evaluation practiced the assessment methods used in this study to maintain interrater reliability.

Sample size

The sample size was determined based on the effect size of the difference between the active and control groups on the change in FMA scores with each intervention. A previous study on upper extremity function in hemiplegic patients with chronic stroke reported an effect size of 1.27 for the change in FMA scores between intervention and control groups [29]. Using G-Power 3.1 software to determine the minimum sample size with a significance level of 0.05 and a power of 0.8, a sample size of 12 individuals per group (24 in total) was initially chosen. To accommodate a potential 20% loss to follow-up, the sample size was increased from 12 to 15 individuals per group (30 in total).

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare nonparametric and parametric data between the two groups, and Fisher's exact test was used for comparing nominal data. The duration of exercise implementation was checked based on self-reported records and exercise records in the VR group, to confirm that training was performed for at least 30 min five days a week. Each endpoint for upper extremity function was compared between groups using the Mann–Whitney U test, evaluating changes with each intervention and during the 4-week observation period, and the U value, degrees of freedom (df), interquartile range (IQR), and P-value were reported. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare outcomes before and post-intervention in each group, and the W statistic, interquartile range (IQR), and P-value were reported. The data obtained were analyzed using JMP® Pro version 17.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

From November 2019 to June 2023, 22 individuals were evaluated for eligibility, 14 of whom met the study criteria (Fig. 2). Although the calculated required sample size was 30 participants, it was difficult to recruit 30 participants with stroke because of the prevailing COVID-19 pandemic in Japan during the study period. The 14 participants were randomly assigned to the VR group (n = 7) and the control group (n = 7) (Table 1). All participants completed the intervention. No intervention-related adverse events were observed in either group, and the intervention was well accepted in both groups. The demographic characteristics of the participants between the two groups are shown in Table 1. The control group had an average FMA-UE score that was 7.3 lower and an average MAL-14 AoU score that was 0.40 lower compared to the VR group at the start of the intervention. All the participants in both groups completed an average of 30 min of training per day, 5 days per week during the study period, and performed outpatient occupational therapy once a week. The average exercise time performed during the intervention period was 838.0 ± 271.8 min for the VR group and 467.9 ± 137.8 min for the control group.

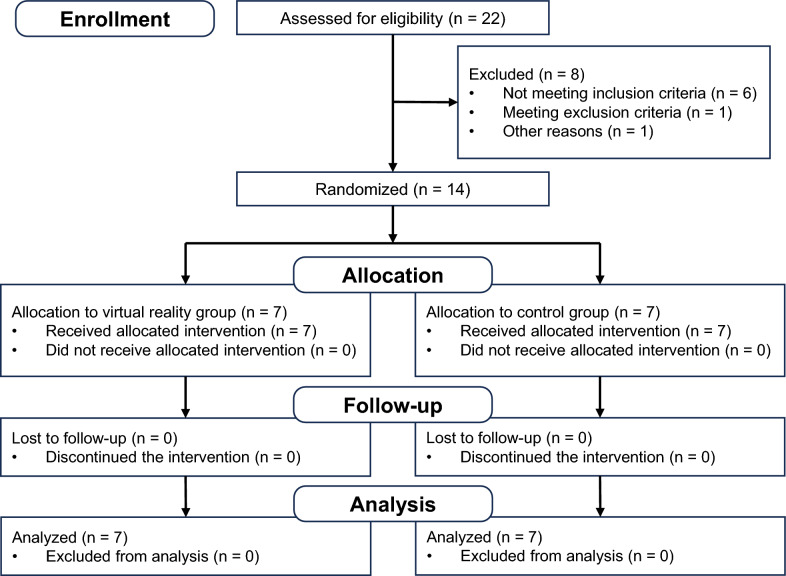

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram of the randomization procedure (CONSORT statement 2010)

Table 1.

Demographic data of study participants (n = 14)

| Characteristicsa | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | VR group (n = 7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45 | 65 | 56 | 60 | 58 | 62 | 60 | 58.0 ± 6.4 |

| Gender | M | M | M | M | M | F | M | 6 Male, 1 females |

| Type of stroke | H | I | H | I | H | I | I | 4 ischemic, 3 hemorrhagic |

| Hemiparetic side | L | R | L | L | L | R | R | 3 right, 4 left |

| Time from stroke onset (years) | 7.4 | 9.8 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 9.5 | 5.3 | 3.5 | 5.4 ± 3.7 |

| FMA-UE total | 37 | 58 | 58 | 56 | 35 | 56 | 52 | 50.3 ± 10.0 |

| A. Shoulder/elbow/forearm | 30 | 30 | 35 | 35 | 30 | 33 | 34 | 28.3 ± 5.0 |

| B. Wrist | 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 6.1 ± 3.5 |

| C. Hand | 12 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 13 | 11.4 ± 2.1 |

| D. Coordination/speed | 2 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4.4 ± 1.3 |

| MAL-14 AoU | 0.92 | 1.93 | 1.08 | 1.60 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 2.33 | 1.26 ± 0.7 |

| Characteristicsa | Case 8 | Case 9 | Case 10 | Case 11 | Case 12 | Case 13 | Case 14 | Control group (n = 7) | p values b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50 | 60 | 43 | 57 | 42 | 53 | 57 | 51.4 ± 6.7 | 0.085 |

| Gender | M | M | M | M | M | M | F | 6 male, 1 females | 1.000 |

| Type of stroke | H | H | H | H | H | H | I | 1 ischemic, 6 hemorrhagic | 0.094 |

| Hemiparetic side | R | L | R | R | L | L | R | 4 right, 3 left | 0.593 |

| Time from stroke onset (years) | 8.8 | 10 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 1 | 8.6 | 4.7 ± 4.2 | 0.760 |

| FMA-UE total | 38 | 47 | 53 | 62 | 52 | 20 | 29 | 43.0 ± 14.8 | 0.303 |

| A. Shoulder/elbow/forearm | 28 | 28 | 35 | 35 | 30 | 10 | 17 | 25.1 ± 8.8 | 0.609 |

| B. Wrist | 7 | 4 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 5.6 ± 3.2 | 0.741 |

| C. Hand | 5 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 6 | 7 | 9.4 ± 3.3 | 0.366 |

| D. Coordination/speed | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2.9 ± 2.4 | 0.255 |

| MAL-14 AoU | 0.77 | 0.92 | 1.43 | 0.71 | 1.45 | 0.50 | 0.21 | 0.86 ± 0.5 | 0.250 |

FMA-UE Fugl-Meyer assessment upper extremity, MAL-14 AoU motor activity log-14 amount of use, H hemorrhagic, I ischemic

aValues are shown as mean ± standard deviation or median with range in parentheses

bP values indicate a significance level of between-group differences with Mann–Whitney U test or χ2 tests

Table 2 shows the FMA-UE scores before, post, and post 4w intervention. In the VR group, the mean difference in FMA-UE scores before–post intervention was 8.9 ± 6.9 (mean = 8, IQR = 2–16), and before–post 4w intervention was 10.1 ± 7.7 (mean = 8, IQR = 5–15). We found significant improvement in FMA-UE scores at post (W = 14.0, P = 0.016) and post 4w (W = 14.0, P = 0.016) compared to before intervention in the VR group by the Wilcoxon signed rank test. These changes exceeded both the minimal detectable change at the 90% confidence level (MDC90) of 3.2 [30] and the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 5.25 [31] for the FMA-UE. In the control group, the mean difference in FMA-UE scores before–post intervention was 1.7 ± 1.7 (mean = 2, IQR = 0–2), and before–post 4w intervention was 2.7 ± 4.0 (mean = 1, IQR = 0–5), indicating no significant improvement in FMA-UE scores at post (W = 12.5, P = 0.063) and post 4w (W = 12.5, P = 0.063) compared to before intervention in the control group.

Table 2.

Intervention scores pre, post, and post 4w of outcome measures in the VR and control groups

| Testa | VR group (n = 7) | Control group (n = 7) | Between-group difference in change | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | Postb | Post 4 weeksb | Before-post change | Before-post 4w change | Before | Postb | Post 4 weeksb | Before-post change | Before-post 4w change | p valuesc (before-post) |

p valuesc (before-post 4w) |

|

| FMA-UE Total | 50.3 ± 10.0 | 59.1 ± 4.4* | 60.4 ± 4.6* | 8.9 ± 1.9 | 10.1 ± 7.7 | 43.0 ± 14.8 | 44.7 ± 15.8 | 45.7 ± 4.6 | 1.7 ± 1.9 | 2.7 ± 4.0 | 0.027* | 0.024* |

| A. Shoulder/elbow/forearm | 28.3 ± 5.0 | 32.4 ± 2.4* | 33.0 ± 1.8* | 4.1 ± 3.6 | 4.7 ± 3.9 | 25.1 ± 8.8 | 26.1 ± 9.3 | 26.0 ± 9.1 | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 0.9 ± 2.0 | 0.051 | 0.033* |

| B. Wrist | 6.1 ± 3.5 | 8.7 ± 1.4* | 8.6 ± 1.5* | 2.6 ± 2.3 | 2.4 ± 3.0 | 5.6 ± 3.2 | 5.9 ± 3.4 | 6.0 ± 3.6 | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.006** | 0.040* |

| C. Hand | 11.4 ± 2.1 | 12.9 ± 1.1 | 13.4 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 2.0 ± 1.9 | 9.4 ± 3.3 | 9.9 ± 3.7 | 10.3 ± 3.9 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 1.1 | 0.300 | 0.260 |

| D. Coordination/speed | 4.4 ± 1.3 | 5.1 ± 1.1 | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 0.7 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 2.4 | 2.9 ± 2.1 | 3.4 ± 2.1 | 0.0 ± 0.6 | 0.6 ± 2.0 | 0.085 | 0.099 |

| MAL-14 AoU | 1.27 ± 0.71 | 1.94 ± 0.87* | 2.43 ± 1.09* | 0.67 ± 0.42 | 1.16 ± 0.68 | 0.86 ± 0.46 | 0.97 ± 0.51 | 0.84 ± 0.42 | 0.11 ± 0.24 | − 0.02 ± 0.19 | 0.014* | 0.007** |

| JTT | 524.7 ± 402.5 | 336.2 ± 312.2** | 303.1 ± 294.7** | − 118.4 ± 112.5 | − 221.5 ± 147.3 | 579.9 ± 454.1 | 588.6 ± 456.6 | 594.1 ± 457.4 | 8.7 ± 30.7 | 14.2 ± 50.5 | 0.002** | 0.002** |

| BBT | 18.1 ± 12.6 | 21.9 ± 11.9* | 23.7 ± 10.9* | 3.7 ± 2.4 | 5.6 ± 3.3 | 14.1 ± 7.5 | 13.0 ± 8.0 | 14.1 ± 8.0 | − 1.1 ± 2.8 | 0.0 ± 1.2 | 0.014* | 0.002** |

aValues are shown as mean ± standard deviations

bComparison between before, post, and post 4w intervention values in each group with Wilcoxon signed rank test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

cComparison between group difference in change with Mann–Whitney U test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Evaluation of the mean difference in FMA-total score between the two groups by the Mann–Whitney U test indicated a statistically significant improvement in before–post (U = 7.0, df = 12, IQR = 1–8, P = 0.027) and before–post 4w (U = 6.5, df = 12, IQR = 1–9.5, P = 0.024) intervention differences in the VR versus the control groups. In terms of FMA sub-score, we found statistically significant differences in FMA-A (shoulder/elbow/forearm) scores in the before–post 4w change (U = 7.5, df = 12, IQR = 0–4, P = 0.033) by the Mann–Whitney U test. Similarly, the FMA-B (wrist) scores both before–post change (U = 4.0, df = 12, IQR = 0–1.5, P = 0.006) and before–post 4w change (U = 9.5, df = 12, IQR = 0–1.25, P = 0.040) were statistically significantly different between the two groups.

The results of the secondary outcome measures are also shown in Table 2. The Mann–Whitney U test showed that the mean difference between the VR and control groups was statistically significant for MAL-14 AoU before–post (U = 5.0, df = 12, IQR = 0–0.71, P = 0.014) and before–post 4w (U = 3.0, df = 12, IQR = 0–1.31, P = 0.007). Similarly, a significant difference was observed between the groups in terms of JTT scores for before–post (U = 0.0, df = 12, IQR = -265.3–0, P = 0.002) and before–post 4w (U = 0.0, df = 12, IQR = -268.8–0, P = 0.002) between the two groups. BBT scores showed significant differences between the two groups for both before–post (U = 5.0, df = 12, IQR = -1.25–4, P = 0.014) and before–post 4w (U = 0.0, df = 12, IQR = 0–6.5, P = 0.002). These results indicate that the VR intervention led to improvements not only in upper extremity function but also in the frequency of paretic hand use and tool and object manipulation in daily life in persons with chronic stroke.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated home-based upper extremity VR rehabilitation in persons with chronic stroke. Home-based upper extremity VR rehabilitation improved FMA-UE, MAL-14 AoU, BBT, and JTT scores. This RCT is the first study to show the effectiveness of task-oriented VR in home-based upper extremity rehabilitation in persons with chronic stroke.

The VR group showed significant improvement compared to the dose-adjusted home program without VR in this study. The improvement could be attributed to the application of task-oriented training using the VR device. This suggests that task-oriented training is one of the optimal approaches for improving upper extremity function.

People with stroke have difficulty using their paretic hands in their ADL due to difficulty in adapting to tools, environments, and activities. Very often, they stop using their paretic hands. Taub et al. explained this phenomenon as "learned nonuse" [32]. They emphasized the necessity for behavioral modifications achieved through opportunities for hand utilization and successful experiences, which are essential for daily functioning.

VR technology can simulate complex tool manipulation. VR provides users with an experience that mimics actual execution. It allows them to achieve a sense of task accomplishment through simplified, simulated operations rather than actual tool manipulation. Previous study showed that VR exercises effectively promoted functional improvements in motor control and daily skills [33]. In this study, VR group participants could repeatedly engage in therapist-recommended, task-oriented practice tailored to their functional level. This task-oriented repetitive practice likely contributed to their functional improvement.

We supposed that increased paretic upper extremity use contributed to the improvement in the VR group in this study. This intervention follows the principle of dose dependence. Evidence shows that intensive, task-specific practice with active patient engagement in challenging motor behaviors improves upper extremity function after stroke [34]. A previous study indicated the potential for functional improvement in upper limb rehabilitation even in the chronic phase of stroke [35]. On the other hand, a vital issue with home-based training is the inability to continue it consistently. A previous study found that adherence to program execution was better with stroke rehabilitation in the presence of a healthcare professional [36]. In contrast, adherence was only 65% in a self-managed home program after discharge from the stroke rehabilitation unit [37]. The main reasons for poor adherence include pain and fear of failure, boredom with exercise, and exercise other than those instructed. The difference in exercise duration during the intervention period between the two groups might have been influenced by these factors. We considered that the outpatient occupational therapy intervention included in the rehabilitation program resolved these issues, leading to continuation of the home program in the VR group. The task-oriented VR device in this study was usable at home without medical personnel. Although there is a need for further study on the optimal frequency and amount of practice required, the observed improvement might have been due to the practice focusing on the elements needed by each participant, with frequent feedback. The device used in this study measured the range of motion (ROM) during each task, allowing adjustments based on changes in ROM and physical condition. However, modifications such as adjusting task difficulty, changing tasks, and correcting posture—key components of motor learning, including increasing difficulty and providing explicit feedback—needed to be addressed during outpatient occupational therapy sessions.

Combining outpatient occupational therapy and home-based VR training allowed for a gradual, individualized program. It is suggested that practice should progress gradually and be appropriately tailored to the individual's abilities and the environmental context [38]. Frequent assessments and gradual changes to home-based VR programs with outpatient occupational therapy made this coordination possible. The VR group showed improvements in MAL-14 AoU post 4w observation. It means that the participants self-perceived increased the amount of use of their paretic hand in their ADL and keep to use their paretic hands. This gradual assistance might have encouraged active use of the paretic hand in daily life and increased its frequency of use.

Limitations of this study

The first limitation of this study was its small sample size. The COVID-19 pandemic often interrupted outpatient clinical practice, making it impossible to collect the predetermined number of study participants. However, the disparity between the actual mean values before and after treatment was 8.9 ± 1.9 in the VR group and 1.7 ± 1.9 in the control group. Based on these metrics, the effect size was calculated as 3.79, with a power value of 0.99 and an alpha error of 0.05. Therefore, the results of this study are still considered valid. In this study, the changes were analyzed as the differences in scores from before to post-intervention and before to post-4 weeks for both the FMA-UE and MAL-14 AoU, considering the impact of baseline score differences between the two groups. Care should be taken when interpreting the results, as the control group had lower baseline scores at the start of the intervention. Second, while improvements were observed after the intervention, the assessment was limited to this duration, and sustained effects of the intervention over a longer period were not tested beyond 4 weeks later. Third, VR interventions are not effective for all persons with functional impairment of the upper extremity. VR devices that do not have external forces must be able to perform at least some range of motion on their own. In particular, VR training without the application of external force is practical for relatively mild paralysis [39]. Finally, the inherent characteristics of the intervention made it difficult to apply blinding of the study participants.

Conclusions

Compared to the conventional home program, the combination of a task-oriented VR home program and outpatient occupational therapy demonstrated significant improvements in upper extremity function and increased the frequency of paretic hand use in persons with chronic stroke. Furthermore, the consistent guidance provided during outpatient occupational therapy sessions likely played a critical role in facilitating the transfer of VR-based movements to meaningful daily activities. These findings suggest that integrating task-oriented VR home programs with professional supervision may enhance rehabilitation outcomes for persons with stroke. On the other hand, considering the advantages of the VR device in ensuring safety and promoting more autonomous use, it is necessary to examine whether professional advice can be provided less frequently while supporting a more self-directed approach to improvement. The results of this study can be expected to be applied to verify whether home programs can be effective through telemedicine advice in the future.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ADL

Activities of daily living

- CIMT

Constraint-induced movement therapy

- VR

Virtual reality

- before

Before the start of the intervention program

- post

Post the end of the intervention program

- post 4w

4 Weeks later post the end of the intervention program

- FMA-UE

Fugl-Meyer assessment of upper extremity motor function score

- JTT

Jebsen-Taylor Hand Function Test

- BBT

Box and Block Test

- MAL-14 AoU

Amount of use score in Motor Activity Log-14

- MAL-14 QoM

Quality of movement score in Motor Activity Log-14

Author contributions

HA, TT, FW, AT, and TF conceptualized and designed the study. HA, TT, and TF performed the formal analysis. YM, MT, RI, KH, HA, and TF carried out the investigation. KH, AT, HA, and TF developed the methodology. TF supervised the study. HA, YM, MT, and RI prepared the original draft. TT, FW, KH, AT, and TF reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by our department and not by any external funding.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants provided written, informed consent for study participation. The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Juntendo University (approval number: H19-0100).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kwakkel G, Kollen BJ, van der Grond J, Prevo AJ. Probability of regaining dexterity in the flaccid upper limb: impact of severity of paresis and time since onset in acute stroke. Stroke. 2003;34(9):2181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taub E, Uswatte G, Mark VW, Morris DM. The learned nonuse phenomenon: implications for rehabilitation. Eura Medicophys. 2006;42(3):241–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buma F, Kwakkel G, Ramsey N. Understanding upper limb recovery after stroke. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2013;31(6):707–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maier M, Ballester BR, Verschure P. Principles of neurorehabilitation after stroke based on motor learning and brain plasticity mechanisms. Front Syst Neurosci. 2019;13:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, Bates B, Cherney LR, Cramer SC, et al. Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery. Stroke. 2016;47(6):e98–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwakkel G, Veerbeek JM, van Wegen EE, Wolf SL. Constraint-induced movement therapy after stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(2):224–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shindo K, Fujiwara T, Hara J, Oba H, Hotta F, Tsuji T, et al. Effectiveness of hybrid assistive neuromuscular dynamic stimulation therapy in patients with subacute stroke: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25(9):830–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawakami M, Fujiwara T, Ushiba J, Nishimoto A, Abe K, Honaga K, et al. A new therapeutic application of brain-machine interface (BMI) training followed by hybrid assistive neuromuscular dynamic stimulation (HANDS) therapy for patients with severe hemiparetic stroke: a proof of concept study. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2016;34(5):789–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veerbeek JM, Langbroek-Amersfoort AC, van Wegen EE, Meskers CG, Kwakkel G. Effects of robot-assisted therapy for the upper limb after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2017;31(2):107–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murakami Y, Honaga K, Kono H, Haruyama K, Yamaguchi T, Tani M, et al. New artificial intelligence-integrated electromyography-driven robot hand for upper extremity rehabilitation of patients with stroke: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2023;37(5):298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laver KE, Lange B, George S, Deutsch JE, Saposnik G, Crotty M. Virtual reality for stroke rehabilitation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Wu J, Zeng A, Chen Z, Wei Y, Huang K, Chen J, et al. Effects of virtual reality training on upper limb function and balance in stroke patients: systematic review and meta-meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(10): e31051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J, Or CK, Chen T. Effectiveness of using virtual reality-supported exercise therapy for upper extremity motor rehabilitation in patients with stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(6): e24111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin JH, Kim MY, Lee JY, Jeon YJ, Kim S, Lee S, et al. Effects of virtual reality-based rehabilitation on distal upper extremity function and health-related quality of life: a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2016;13:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Chen JL, Wong AMK, Liang KC, Tseng KC. Game-based virtual reality system for upper limb rehabilitation after stroke in a clinical environment: systematic review and meta-analysis. Games Health J. 2022;11(5):277–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bargeri S, Scalea S, Agosta F, Banfi G, Corbetta D, Filippi M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of virtual reality rehabilitation after stroke: an overview of systematic reviews. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;64: 102220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cramer SC, Dodakian L, Le V, See J, Augsburger R, McKenzie A, et al. Efficacy of home-based telerehabilitation vs in-clinic therapy for adults after stroke: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(9):1079–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu Q, Cronce A, Patel J, Fluet GG, Mont AJ, Merians AS, et al. Development of the home based virtual rehabilitation system (HoVRS) to remotely deliver an intense and customized upper extremity training. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2020;17(1):155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gauthier LV, Nichols-Larsen DS, Uswatte G, Strahl N, Simeo M, Proffitt R, et al. Video game rehabilitation for outpatient stroke (VIGoROUS): a multi-site randomized controlled trial of in-home, self-managed, upper-extremity therapy. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;43: 101239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, Vitaliano P, Dokmak A. The mini-cog: a cognitive “vital signs” measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(11):1021–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson A, Korner-Bitensky N, Levin M. Virtual reality in stroke rehabilitation: a systematic review of its effectiveness for upper limb motor recovery. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2007;14(2):52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fugl-Meyer AR, Jääskö L, Leyman I, Olsson S, Steglind S. The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. a method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1975;7(1):13–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robert H. Jebsen MD, Cincinnati O, Neal Taylor MD, Roberta B. Trieschmann PD, Martha J. Trotter BA, Linda A. Howard BA. An objective and standardized test of hand function. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1969:311–9. [PubMed]

- 24.Mathiowetz V, Volland G, Kashman N, Weber K. Adult norms for the box and block test of manual dexterity. Am J Occup Ther. 1985;39(6):386–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uswatte G, Taub E, Morris D, Vignolo M, McCulloch K. Reliability and validity of the upper-extremity motor activity log-14 for measuring real-world arm use. Stroke. 2005;36(11):2493–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gladstone DJ, Danells CJ, Black SE. The fugl-meyer assessment of motor recovery after stroke: a critical review of its measurement properties. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2002;16(3):232–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mollà-Casanova S, Llorens R, Borrego A, Salinas-Martínez B, Serra-Añó P. Validity, reliability, and sensitivity to motor impairment severity of a multi-touch app designed to assess hand mobility, coordination, and function after stroke. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2021;18(1):70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desrosiers J, Bravo G, Hébert R, Dutil E, Mercier L. Validation of the Box and Block Test as a measure of dexterity of elderly people: reliability, validity, and norms studies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75(7):751–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takebayashi T, Koyama T, Amano S, Hanada K, Tabusadani M, Hosomi M, et al. A 6-month follow-up after constraint-induced movement therapy with and without transfer package for patients with hemiparesis after stroke: a pilot quasi-randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(5):418–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.See J, Dodakian L, Chou C, Chan V, McKenzie A, Reinkensmeyer DJ, et al. A standardized approach to the Fugl-Meyer assessment and its implications for clinical trials. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013;27(8):732–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin JH, Hsu MJ, Sheu CF, Wu TS, Lin RT, Chen CH, et al. Psychometric comparisons of 4 measures for assessing upper-extremity function in people with stroke. Phys Ther. 2009;89(8):840–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taub E, Uswatte G, Morris DM. Improved motor recovery after stroke and massive cortical reorganization following constraint-induced movement therapy. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2003;14(1 Suppl):S77-91 (ix). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiper P, Godart N, Cavalier M, Berard C, Cieślik B, Federico S, et al. Effects of immersive virtual reality on upper-extremity stroke rehabilitation: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2023;13(1):146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schweighofer N, Han CE, Wolf SL, Arbib MA, Winstein CJ. A functional threshold for long-term use of hand and arm function can be determined: predictions from a computational model and supporting data from the extremity constraint-induced therapy evaluation (EXCITE) trial. Phys Ther. 2009;89(12):1327–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hatem SM, Saussez G, Della Faille M, Prist V, Zhang X, Dispa D, et al. Rehabilitation of motor function after stroke: a multiple systematic review focused on techniques to stimulate upper extremity recovery. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jurkiewicz MT, Marzolini S, Oh P. Adherence to a home-based exercise program for individuals after stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2011;18(3):277–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller KK, Porter RE, DeBaun-Sprague E, Van Puymbroeck M, Schmid AA. Exercise after stroke: patient adherence and beliefs after discharge from rehabilitation. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2017;24(2):142–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levin MF, Demers M. Motor learning in neurological rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(24):3445–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Everard G, Declerck L, Detrembleur C, Leonard S, Bower G, Dehem S, et al. New technologies promoting active upper limb rehabilitation after stroke: an overview and network meta-analysis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2022;58(4):530–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.