Abstract

Peroxins are proteins required for peroxisome assembly and are encoded by the PEX genes. Functional complementation of the oleic acid–nonutilizing strain mut1-1 of the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica has identified the novel gene, PEX24. PEX24 encodes Pex24p, a protein of 550 amino acids (61,100 Da). Pex24p is an integral membrane protein of peroxisomes that exhibits high sequence homology to two hypothetical proteins encoded by the open reading frames YHR150W and YDR479C of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Pex24p is detectable in wild-type cells grown in glucose-containing medium, and its levels are significantly increased by incubation of cells in oleic acid–containing medium, the metabolism of which requires intact peroxisomes. pex24 mutants are compromised in the targeting of both matrix and membrane proteins to peroxisomes. Although pex24 mutants fail to assemble functional peroxisomes, they do harbor membrane structures that contain subsets of peroxisomal proteins.

INTRODUCTION

Peroxisomes belong to the microbody family of organelles, which also includes the glyoxysomes of plants and the glycosomes of trypanosomes. Peroxisomes are spherical in shape, delimited by a single membrane and contain a fine granular matrix and sometimes a paracrystalline core. Peroxisomes inactivate toxic substances, regulate cellular oxygen concentration, and metabolize lipids, nitrogen bases, and carbohydrates (reviewed by Lazarow and Fujiki, 1985; van den Bosch et al., 1992; Subramani, 1998; Purdue and Lazarow, 2001). Peroxisomes are essential for genetic disorders collectively known as the peroxisome biogenesis disorders (PBD), such as Zellweger syndrome, in which peroxisomes fail to assemble properly (Lazarow and Moser, 1994; Subramani, 1998; Subramani et al., 2000; Purdue and Lazarow, 2001).

Defining the molecular bases of the PBDs has been an area of intense research in recent years, particularly in regards to the identification of genes controlling peroxisome assembly. Much progress has been made in the identification of these so-called PEX genes by the use of various yeasts as model systems. To date, the PEX genes for 23 peroxins have been isolated from yeast (for reviews, see Subramani, 1998; Titorenko and Rachubinski, 2001; Purdue and Lazarow, 2001). Thirteen human orthologues of these yeast PEX genes have been identified, and mutations in 11 of these have been shown to cause PBDs (for reviews, see Subramani et al., 2000; Fujiki, 2000; Gould and Valle, 2000).

Protein targeting to peroxisomes is defective in pex mutants. Peroxisomal proteins are encoded by nuclear genes and synthesized on cytosolic polysomes (Lazarow and Fujiki, 1985; Subramani, 1993, 1998; Subramani et al., 2000; Purdue and Lazarow, 2001). Most matrix proteins are targeted to the peroxisome by one of two types of peroxisome targeting signal (PTS). PTS1 is a carboxyl-terminal tripeptide with the consensus sequence (S/A/C)(K/R/H)(L/M) (Gould et al., 1987, 1989, 1990; Aitchison et al., 1991; Swinkels et al., 1992) and is found in the majority of matrix proteins. PTS2 is a sometimes cleaved amino-terminal nonapeptide with the consensus motif (R/K)(L/V/I)X5(H/Q)(L/A), which is found in a smaller subset of matrix proteins (Osumi et al., 1991; Swinkels et al., 1991; Glover et al., 1994b; Waterham et al., 1994). A few peroxisomal matrix proteins are targeted by internal PTSs, which remain largely uncharacterized (Purdue et al., 1990; Kragler et al., 1993; Elgersma et al., 1995). Pex5p and Pex7p are the receptors for PTS1- and PTS2-containing proteins, respectively, and various peroxins, notably Pex13p and Pex14p, form a docking complex at the peroxisomal membrane for these receptors (reviewed by Subramani 1998; Hettema et al., 1999; Terlecky and Fransen, 2000; Purdue and Lazarow, 2001; Titorenko and Rachubinski, 2001). The pathway of targeting proteins to the peroxisomal membrane has been less well defined; however, it appears to be independent of the pathway for matrix protein targeting. Motifs consisting of stretches of basic amino residues have been suggested to target proteins to the peroxisomal membrane (McCammon et al., 1994; Dyer et al., 1996; Elgersma et al., 1997; Pause et al., 2000). A distinctive feature of peroxisomes is their ability to import assembled oligomeric proteins (Glover et al., 1994a; McNew and Goodman, 1994; Titorenko et al., 1998, 2002).

Here, we report the isolation and characterization of a novel PEX gene, PEX24, from the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Mutants of PEX24 are compromised in peroxisome assembly and mislocalize both peroxisomal matrix and membrane proteins. Pex24p is an integral membrane protein of peroxisomes, whose levels are increased by incubation of cells in oleic acid–containing medium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Culture Conditions

The Y. lipolytica strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All strains were cultured at 30°C. Strains with plasmids were cultured in minimal medium (YND or YNO), except for strain P24TR, which expresses the PEX24 gene from the plasmid pUB4 (Kerscher et al., 2001) and was cultured in YEPD or YPBO supplemented with Hygromycin B (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at a concentration of 125 μg/ml. Media components were as follows: YEPD, 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose; YPBO, 0.3% yeast extract, 0.5% peptone, 0.5% K2HPO4, 0.5% KH2PO4, 1% Brij 35, 1% (vol/vol) oleic acid; YND, 0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 2% glucose; YNO, 0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 0.05% (wt/vol) Tween 40, 0.1% (vol/vol) oleic acid. YND and YNO were supplemented with leucine, lysine, and uracil, each at 50 μg/ml, as required.

Table 1.

Y. lipolytica strains used in this study

| Straina | Genotype |

|---|---|

| E122 | MATA, ura3-302, leu2-270, lys8-11 |

| mut1-1 | MATA, ura3-302, leu2-270, lys8-11, ole |

| pex24KOA | MATA, ura3-302, leu2-270, lys8-11, pex24∷URA3 |

| P24TR | MATA, ura3-302, leu2-270, lys8-11, pUB4(HygBR)PEX24 |

Strain E122 was a gift of C. Gaillardin (Thiverval-Grignon, France). All other strains were from this study.

Cloning, Sequencing, and Integrative Disruption of the PEX24 Gene

The mut1-1 mutant strain was isolated from randomly mutagenized Y. lipolytica wild-type strain E122 as described previously (Nuttley et al., 1993). The PEX24 gene was isolated by functional complementation of the mut1-1 strain with a Y. lipolytica genomic DNA library in the autonomously replicating Escherichia coli shuttle vector, pINA445 (Nuttley et al., 1993). Leu+ transformants were screened on YNO agar plates for restoration of the ability to use oleic acid as the sole carbon source. Total DNA was isolated from colonies that recovered growth on YNO and used to transform E. coli for plasmid recovery. Restriction fragments of the initial complementing genomic insert were subcloned and tested for their ability to complement the mut1-1 strain. The shortest complementing fragment was sequenced in both directions, and the gene contained therein was designated PEX24.

The URA3 gene of Y. lipolytica was used for targeted integrative disruption of the PEX24 gene. Nine hundred thirty-nine base pairs of DNA immediately upstream of the PEX24 open reading frame (ORF) were amplified by the PCR using the oligonucleotides 5′-ATTGAATTCAGTACCAGTACATGAAAGATC (primer A) and 5′-TGTATAAAGTCGACGTGTGCGGGTGGTTGTGT (primer B), cleaved with EcoRI and SalI, and inserted into the corresponding sites of the vector pGEM4Zf (Promega, Madison, WI) to generate the plasmid pUP. Eight hundred forty-six base pairs of DNA immediately downstream of the PEX24 ORF was amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotides 5′-GCACACGTCGACTTTATACAACATTGTCGAGCG (primer C) and 5′-ATTAAGCTTGTCGCGTGTCGAGAC (primer D), cleaved with SalI and HindIII, and inserted into pUP to produce the plasmid pUP-DS. A 1.7-kbp SalI fragment containing the Y. lipolytica URA3 gene was ligated into the SalI site of pUP-DS. A fragment containing the URA3 gene flanked by the 939 base pairs of sequence upstream and the 846 base pairs of sequence downstream of the PEX24 ORF was amplified by PCR using primers A and D. This fragment was used to transform Y. lipolytica wild-type strain E122 to uracil prototrophy. Ura+ transformants were selected and screened for their inability to grow on oleic acid–containing medium. Integration of the URA3 gene into the correct locus was confirmed by PCR.

Antibodies

Antibodies to Pex24p were raised in rabbit and guinea pig against a maltose-binding protein-Pex24p fusion. A HindIII fragment encompassing nucleotides 969-1653 of the PEX24 ORF was cloned into the vector pMAL-c2 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) in-frame and downstream of the ORF encoding maltose-binding protein, followed by expression in E. coli (Eitzen et al., 1995). Anti-Pex24p antibodies were affinity purified as described (Crane et al., 1994). Antibodies to the carboxyl-terminal SKL tripeptide, isocitrate lyase (ICL), thiolase (THI), acyl-CoA oxidase subunit 5 (AOX), Pex1p, Pex2p, Pex6p, Pex16p, Pex19p, Pex20p, and Kar2p have been described previously (Aitchison et al., 1992; Eitzen et al., 1996; Lambkin et al., 2001; Titorenko et al., 1997, 1998, 2000, 2002). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG and HRP-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG secondary antibodies (Amersham Biosciences, Baie d'Urfé, Quebec, Canada) were used to detect primary antibodies in immunoblot analysis. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and rhodamine-conjugated anti-guinea pig IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) were used to detect primary antibodies in immunofluorescence microscopy.

Microscopic Analysis

Cells were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature and processed for immunofluorescence microscopy as described (Pringle et al., 1991), except that spheroplasts were prepared by incubation in 0.1 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, 1.2 M sorbitol, 40 μg of Zymolyase-100T/ml, and 38 mM 2-mercaptoethanol for 15–30 min at 30°C with gentle agitation. Images were captured with a digital fluorescence camera (Spot Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI).

Electron microscopy of whole yeast cells was performed as described previously (Goodman et al., 1990)

Cell Fractionation and Peroxisome Subfractionation

Fractionation of oleic acid–induced cells was performed essentially as described (Szilard et al., 1995). Homogenized spheroplasts were subjected to differential centrifugation at 1000 × g for 10 min at 4°C in a JS13.1 rotor (Beckman, Fullerton, CA) to yield a postnuclear supernatant (PNS) fraction. The PNS fraction was subjected to further differential centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to yield a pellet (20KgP) fraction enriched for peroxisomes and mitochondria and a supernatant (20KgS) fraction enriched for cytosol. Peroxisomes were purified from the 20KgP fraction by isopycnic centrifugation on a discontinuous sucrose gradient (Titorenko et al., 1996).

To subfractionate peroxisomes, 10 volumes of ice-cold 0.1 M Na2CO3, pH 11.5, were added to the 20KgP fraction containing 100 μg of protein (Fujiki et al., 1982). The sample was incubated on ice for 45 min with occasional agitation, followed by centrifugation at 200,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C in a TLA120.2 rotor (Beckman) to yield a pellet fraction enriched for integral membrane proteins and a supernatant fraction enriched for soluble proteins.

Analytical Procedures

Enzymatic activity of the mitochondrial marker cytochrome c oxidase (Douma et al., 1985) was measured as described. Whole cell lysates were prepared as described (Eitzen et al., 1997). Extraction of nucleic acid from yeast lysates and manipulation of DNA were performed as described (Ausubel et al., 1994). Immunoblotting was performed using a wet transfer system (Ausubel et al., 1994), and antigen-antibody complexes in immunoblots were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences). Protein concentration was determined using a commercially available kit (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and bovine serum albumin as a standard. Proteins were precipitated by addition of trichloroacetic acid to 10%, followed by washing of the precipitate with chilled 80% acetone. Oligonucleotides were synthesized on an Oligo 1000 M DNA Synthesizer (Beckman). Sequencing was performed on an ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyzer (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

RESULTS

Isolation and Characterization of the PEX24 Gene

The mut1-1 mutant strain (Table 1) was isolated from randomly mutagenized wild-type Y. lipolytica cells by its inability to grow on medium containing oleic acid as the sole carbon source (the ole phenotype; Figure 1). Morphological and biochemical analyses (data presented below) determined that this strain was defective in peroxisome assembly. The PEX24 gene was isolated from a Y. lipolytica genomic DNA library by functional complementation, i.e., restoration of growth on oleic acid–containing medium (the OLE phenotype), of the mut1-1 strain. DNA was isolated from the complemented strain, and the complementing plasmid was recovered by transformation of E. coli. The complementing fragment, CS-01, was mapped by restriction endonuclease digestion (Figure 2A). Various restriction fragments were subcloned and introduced by transformation into the mut1-1 strain to delineate the region of complementation (Figure 2A). Sequencing of the complementing fragment CS-SS revealed an ORF of 1650 nucleotides encoding a protein of 550 amino acids, Pex24p, with a predicted molecular weight of 61,100 (Figure 2B). Based on algorithms predicting membrane-associated regions in proteins (Eisenberg et al., 1984; Rao and Argos, 1986), Pex24p is predicted to contain two membrane-spanning domains at amino acids 216–249 and 335–361. A search of protein databases with the use of the GENINFO(R) BLAST Network Service of the National Center for Biotechnology Information revealed two proteins encoded by the ORFs YHR150W and YDR479C of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome (Figure 3) that share extensive sequence homology with Pex24p. Sequencing of the PEX24 gene in the mut1-1 strain revealed a nonsense mutation at codon 118.

Figure 1.

Growth of various Y. lipolytica strains on glucose-containing (YEPD) and oleic acid–containing (YPBO) media. The strains listed in Table 1 were grown to midlog phase in liquid YEPD medium, spotted at dilutions of 10−1 to 10−5 on both YEPD and YPBO agar, and grown for 5 d at 30°C.

Figure 2.

Cloning and analysis of the PEX24 gene. (A) Complementing activity of inserts, restriction map analysis, and targeted gene disruption strategy for the PEX24 gene. The thick black line represents the original complementing insert DNA. (Solid lines) Y. lipolytica genomic DNA; (dotted lines) vector DNA. The ORFs of the PEX24 and URA3 genes and their directionality are denoted by the wide arrows. (+) Ability and (−) inability of an insert to confer growth on oleic acid to strain mut1-1. (B) Nucleotide sequence of the PEX24 gene and deduced amino acid sequence of Pex24p. These sequence data have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession number AF480881.

Figure 3.

Sequence alignment of Pex24p with the hypothetical proteins Yhr150wp and Ydr479cp encoded by the ORFs YHR150W and YDR479C, respectively, of the S. cerevisiae genome. Amino acid sequences were aligned with the use of the ClustalW program (EMBL, Heidelberg, Germany). Identical residues (black) and similar residues (gray) in at least two of the proteins are shaded. Similarity rules: G = A = S; A = V; V = I = L = M; I = L = M = F = Y = W; K = R = H; D = E = Q = N; and S = T = Q = N. Dashes represent gaps.

The PEX24 gene was deleted by targeted integration of the Y. lipolytica URA3 gene to generate the strain pex24KOA (Table 1). This strain was unable to grow on oleic acid–containing medium (Figure 1) and showed similar morphological and biochemical defects to the original mut1-1 strain (see below).

pex24 Cells Lack Normal Peroxisomes and Mislocalize Peroxisomal Proteins to the Cytosol

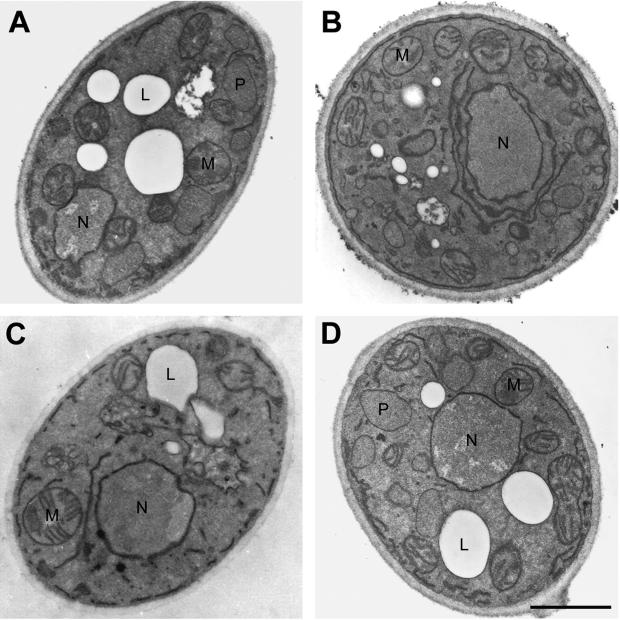

In electron micrographs, normal peroxisomes of Y. lipolytica grown in oleic acid–containing medium appear as round vesicular structures, 0.2–0.5 μm in diameter, surrounded by a single unit membrane and containing an homogenous granular matrix (Figure 4A). The original mutant strain mut1-1 (Figure 4B) contained small vesicular structures and some larger vesicles resembling peroxisomes and accumulated membranous sheets around the nucleus that were rarely seen in wild-type cells. The deletion strain pex24KOA showed no morphologically recognizable peroxisomes but again showed an accumulation of extended membranes (Figure 4C). Strain P24TR transformed with the PEX24 gene had the appearance of the wild-type strain and showed normal peroxisome morphology (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Ultrastructure of wild-type, pex24 mutant, and PEX24-transformed strains. The E122 (A), mut1-1 (B), pex24KOA (C), and P24TR (D) strains were grown in glucose-containing YEPD medium for 16 h, shifted to oleic acid–containing YPBO medium and incubated for an additional 9 h. Cells were fixed in 1.5% KMnO4 and processed for electron microscopy. L, lipid droplet; M, mitochondrion; N, nucleus; P, peroxisome. Bar, 1 μm.

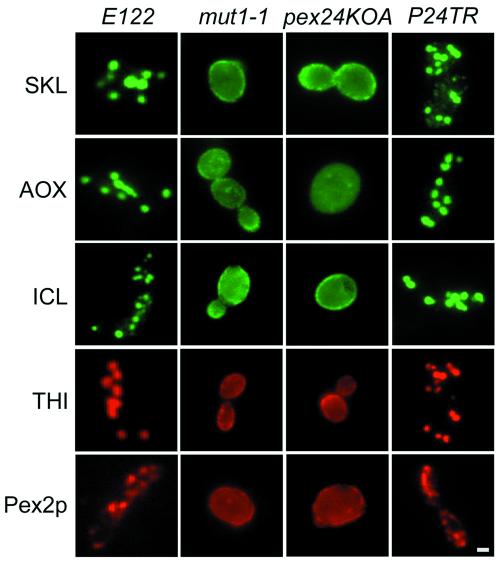

Immunofluorescence analysis of oleic acid–incubated wild-type E122 cells with anti-SKL antibodies and antibodies to the matrix proteins acyl-CoA oxidase (AOX), isocitrate lyase (ICL), and thiolase (THI) and to the peroxisomal integral membrane protein Pex2p showed a punctate pattern of staining characteristic of peroxisomes (Figure 5). In contrast, mut1-1 and pex24KOA cells stained with the same antibodies showed a more diffuse pattern of fluorescence characteristic of a cytosolic localization (Figure 5). Strain P24TR transformed with the PEX24 gene showed the characteristic peroxisomal staining pattern observed in wild-type cells, indicating the ability of this gene to rescue the import of these peroxisomal proteins.

Figure 5.

Peroxisomal matrix and membrane proteins are mislocalized in pex24 mutant strains. Wild-type strain E122, mutant strains mut1-1 and pex24KOA, and transformed strain P24TR were grown in YEPD medium for 16 h, transferred to YPBO medium, and incubated for an additional 9 h. Cells were processed for immunofluorescence microscopy with antibodies to the PTS1 tripeptide SKL (SKL), acyl-CoA oxidase (AOX), isocitrate lyase (ICL), thiolase (THI), and the integral peroxisomal membrane protein Pex2p. Rabbit primary antibodies (SKL, AOX, and ICL) were detected with fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibodies. Guinea pig primary antibodies (THI and Pex2p) were detected with rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibodies. Bar, 1 μm.

Cells of the wild-type strain E122 and of the mutant strains mut1-1 and pex24KOA were grown for 16 h in glucose-containing medium, shifted to oleic acid–containing medium for an additional 9 h, and then fractionated into a 20,000 × g pellet (20KgP) fraction enriched for peroxisomes and mitochondria and a 20,000 × g supernatant (20KgS) fraction enriched for cytosol. In agreement with data from immunofluorescence microscopy, peroxisomal matrix proteins (Figure 6) were preferentially localized to the 20KgP fraction of wild-type cells; however, they were localized primarily to the 20KgS fraction of both mutant strains. It is noteworthy that AOX was found equally distributed between the 20KgS and 20KgP fractions of the original mutant strain mut1-1. The mitochondrial marker enzyme cytochrome c oxidase was preferentially localized to the 20KgP fraction of all strains. Because in pex24 mutant strains all matrix proteins investigated mislocalized preferentially to the 20KgS fraction enriched for cytosol and exhibited a generalized pattern of fluorescence characteristic of the cytosol in immunofluorescence microscopy, pex24 mutants are compromised in the import of PTS1 (ICL and anti-SKL proteins), PTS2 (THI), and non-PTS1, non-PTS2 proteins (AOX; Wang et al., 1999). The peroxisomal peroxin Pex19p (Lambkin and Rachubinski, 2001), the peripheral peroxisomal membrane peroxin Pex16p (Eitzen et al., 1997) and the integral peroxisomal membrane peroxin Pex2p (Eitzen et al., 1996) were all localized primarily to the 20KgP of E122 cells (Figure 6). In contrast, these peroxins were localized almost exclusively to the 20KgS of both mut1-1 and pex24KOA cells, demonstrating a preferential mislocalization of these peroxisomal peroxins to the cytosol in these strains.

Figure 6.

Peroxisomal matrix proteins and peroxisomal peroxins show mislocalization in pex24 mutant strains. The wild-type strain E122, the original mutant strain mut1-1, and the deletion strain pex24KOA were grown in glucose-containing YEPD medium for 16 h, transferred to oleic acid–containing YPBO medium, and incubated for an additional 9 h. Cells were subjected to subcellular fractionation to yield a 20KgP fraction enriched for peroxisomes and mitochondria and a 20KgS fraction enriched for cytosol. Equal portions of the 20KgS and 20KgP were analyzed by immunoblotting to peroxisomal matrix proteins (SKL, ICL, AOX, and THI) and to peroxisomal peroxins.

pex24 Cells Contain Membrane Structures Containing Both Peroxisomal Matrix and Membrane Proteins

The 20KgP fractions of the wild-type strain E122 and of the mut1-1 and pex24KO mutant strains incubated in oleic acid–containing medium were subjected to isopycnic sucrose gradient density centrifugation. Fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies to peroxisomal matrix proteins (anti-SKL proteins, ICL, AOX, and THI), to the peroxins Pex16p, Pex19p, and Pex2p, and to the endoplasmic reticulum-resident protein, Kar2p (Figure 7). In E122 cells, all peroxisomal proteins investigated were found primarily in fractions 3–5, peaking in fraction 4 at a density of 1.21 g/cm3, which has previously been reported as the density of peroxisomes of Y. lipolytica in sucrose (Szilard et al., 1995; Titorenko et al., 1996; Brown et al., 2000), whereas Kar2p exhibited an almost even distribution across all gradient fractions. In mut1-1 and pex24KOA cells, evidence of membrane structures having a density similar to that of wild-type peroxisomes was observed; however, these structures contained a complement of proteins different from that of wild-type peroxisomes. Anti-SKL proteins, ICL, THI, and Pex19p, but not the peripheral membrane protein Pex16p or the integral membrane protein Pex2p, were detected in structures found in fraction 4 of the mut1-1 strain. Only anti-SKL proteins, ICL and THI, were detected in structures found in fraction 4 of the deletion strain pex24KOA. Membrane structures of density less than that of wild-type peroxisomes but containing peroxisomal proteins were also observed for both wild-type cells and to a much greater extent for mut1-1 and pex24KOA cells. The origin of these membrane structures is currently unknown, but it should be noted that Kar2p is readily seen to cofractionate with them in gradients of the mut1-1 and pex24KOA strains. It is noteworthy that both the 47-kDa precursor form and the 45-kDa mature form of thiolase were detected in the mut1-1 strain, whereas only the precursor form was detected in the pex24KOA deletion strain. For all strains, the mitochondrial marker cytochrome c oxidase localized primarily to fractions 9 and 10 with densities of 1.18 and 1.17 g/cm3, well separated from fraction 4 containing the peak immunodetection of peroxisomal proteins for the wild-type strain.

Figure 7.

Peroxisomal proteins of pex24 cells localize in part to membrane structures that are of the same density as wild-type peroxisomes. The 20KgP fractions of the wild-type strain E122, the original mutant strain mut1-1 and the deletion strain pex24KOA incubated in oleic acid–containing medium for 9 h were subjected to isopycnic centrifugation on discontinuous sucrose gradients. Fifteen 2-ml fractions were collected from the bottom of each tube. Equal volumes of each fraction were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies to the indicated proteins. The volume of fractions of the mut1-1 and pex24KOA strains analyzed by SDS-PAGE was 10 times that of fractions of the wild-type strain E122.

Pex24p Is an Integral Membrane Protein of Peroxisomes

Double-labeling indirect immunofluorescence microscopy of wild-type cells incubated in oleic acid–containing medium with antibodies to thiolase and to Pex24p showed colocalization of these proteins to punctate structures (Figure 8A). Pex24p was localized exclusively to the 20KgP fraction enriched for peroxisomes and mitochondria from wild-type cells (Figure 8B) and fractionated with peroxisomes in isopycnic density gradient centrifugation (Figure 7). Lysis of peroxisomes with alkali Na2CO3, followed by high-speed centrifugation, showed that Pex24p cofractionated with Pex2p to the pellet fraction enriched for integral membrane proteins (Figure 8C). Therefore, Pex24p is an integral membrane proteins of peroxisomes.

Figure 8.

Pex24p is an integral peroxisomal membrane protein. (A) Double-labeling, indirect immunofluorescence microscopy of wild-type cells with antibodies to thiolase (THI) and to Pex24p. Bar, 1 μm. (B) Immunoblot analysis of 20KgS and 20KgP subcellular fractions from wild-type cells incubated in oleic acid–containing medium with anti-Pex24p antibodies. Equivalent portions of each fraction were analyzed. (C) Immunoblot analysis of wild-type peroxisomes treated with alkali Na2CO3 and separated by centrifugation into supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions. The top and second blots were probed with antibodies to THI and acyl-CoA oxidase (AOX), respectively, to detect peroxisomal matrix proteins. The third blot was probed with antibodies to the peroxisomal integral membrane protein Pex2p. The bottom blot was probed with antibodies to Pex24p. Equivalent portions of the supernatant and pellet fractions were analyzed.

Synthesis of Pex24p Is Induced by Incubation of Cells In Oleic Acid-Containing Medium

Wild-type E122 cells grown in glucose-containing medium were transferred to oleic acid–containing YPBO medium and incubated for 8 h in this medium. Aliquots of cells were removed at various times during the incubation in YPBO medium, and their lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Pex24p was barely detectable at the time of transfer to YPBO medium, but its synthesis increased with time after the transfer (Figure 9). Under the same conditions, the level of the peroxisomal matrix enzyme thiolase (THI) increased dramatically, whereas the level of the cytosolic enzyme glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) remained unchanged.

Figure 9.

Synthesis of Pex24p is induced by incubation of Y. lipolytica in oleic acid–containing medium. Wild-type E122 cells grown for 16 h in glucose-containing YEPD medium were transferred to, and incubated in, oleic acid–containing YPBO medium. Aliquots of cells were removed from the YPBO medium at the times indicated, and total cell lysates were prepared. Equal amounts of protein from the total cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antibodies to Pex24p, thiolase (THI), and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH).

DISCUSSION

We have identified and characterized a novel mutant of peroxisome assembly of the yeast Y. lipolytica. Functional complementation of this mutant strain has led to the identification of the gene PEX24, which encodes a 550-amino acid protein, Pex24p, with a predicted molecular mass of 61,100 Da. Pex24p was shown to be peroxisomal by both double-label, indirect immunofluorescence microscopy and subcellular fractionation. Pex24p is predicted to contain two membrane-spanning domains and displays the characteristics of an integral membrane protein during extraction of a subcellular fraction enriched for peroxisomes with alkali sodium carbonate. Pex24p shows strong sequence similarity to two putative proteins encoded by the ORFs YHR150W and YDR479C of the S. cerevisiae genome. These proteins, which have not yet been characterized, are the subject of current investigations in our laboratory. Possible functional redundancy between these two proteins may have prevented their ready identification as PEX genes in S. cerevisiae by selection procedures involving random mutagenesis.

The ability to use oleic acid as sole carbon source was greatly reduced in the original mutant strain mut1-1, whereas it was completely abolished in the deletion strain pex24KOA. DNA sequencing revealed a nonsense mutation at codon 118 of the PEX24 gene of the mut1-1 strain. Judging from the reduced growth of the mut1-1 strain on oleic acid–containing medium and the presence of small vesicular structures resembling peroxisomes in mut1-1 cells seen by electron microscopy, it can be speculated that the shortened form of Pex24p synthesized in the mut1-1 strain retains some of its function(s).

Isopycnic density gradient centrifugation analysis showed that both the original mutant strain mut1-1 and the deletion strain pex24KOA contain membrane structures having densities both like and less than that of normal peroxisomes. These membrane structures are not “peroxisome ghosts,” which are found in cells of Zellweger syndrome patients and were defined originally as membranous structures containing peroxisomal membrane proteins but not peroxisomal matrix proteins (Santos et al., 1988), because they contain both peroxisomal matrix and membrane proteins. Similar membrane structures have been reported for other Y. lipolytica pex strains (Brown et al., 2000; Lambkin and Rachubinski, 2001). Whether these structures are precursors to mature peroxisomes (South and Gould, 1999; Titorenko et al., 2000) or simply types of peroxisomes lacking their full complement of peroxisomal proteins is unknown at present.

Pex5p and Pex7p act as cytosolic receptors for PTS1- and PTS2-containing proteins, respectively. Although there is distinct separation in these two pathways of matrix protein import at this initial stage, convergence of the two pathways is believed to occur at the level of the peroxisome and to involve the peroxins Pex13p and Pex14p. Pex13p and Pex14p are integral proteins of the peroxisomal membrane that recognize both Pex5p and Pex7p and form a complex with each other (for reviews, see Subramani, 1998; Hettema et al., 1999; Purdue and Lazarow, 2001; Titorenko and Rachubinski, 2001). Because the import of all peroxisomal matrix proteins investigated in this study is compromised in the pex24 mutant strains regardless of their type of PTS, Pex24p may act downstream of the point of convergence of the PTS1 and PTS2 pathways, thereby affecting the import of all peroxisomal matrix proteins. It should be noted that the targeting of peroxisomal membrane proteins is also compromised in pex24 mutant strains. Because the targeting of peroxisomal matrix and membrane proteins apparently occurs by independent pathways and mechanisms (for reviews, see Subramani, 1998; Hettema et al., 1999; Purdue and Lazarow, 2001; Titorenko and Rachubinski, 2001), the primary role of Pex24p may actually be in the targeting and/or assembly of peroxisomal membrane proteins. The effects of mutation of Pex24p on peroxisomal matrix protein import would therefore be secondary to the primary defect in peroxisomal membrane protein targeting/assembly. Dysfunction and/or absence of Pex24p could also be proposed to lead to major structural alterations in the peroxisomal membrane that would prevent or hinder the correct assembly of the translocation machineries required for the import of matrix and membrane proteins. Defining the exact role played by Pex24p in the peroxisome assembly process awaits further experimentation, including an analysis of the interacting partners of Pex24p.

In conclusion, we have identified and characterized a novel peroxin, Pex24p, required for peroxisome assembly in the yeast Y. lipolytica. Pex24p is an integral peroxisomal membrane protein. Mutants of the PEX24 gene are compromised in the targeting of both peroxisomal matrix and membrane proteins and fail to assemble functional peroxisomes, but they are nevertheless capable of assembling membrane structures that exhibit peroxisomal characteristics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Honey Chan for help with electron microscopy and Richard Poirier for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by grant MOP-9208 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to R.A.R. R.A.R. is Canada Research Chair in Cell Biology, a Senior Investigator of the CIHR, and an International Research Scholar of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Abbreviations used:

- 20KgP

20,000 × g pellet

- 20KgS

20,000 × g supernatant

- AOX

acyl-CoA oxidase

- ICL

isocitrate lyase

- ORF

open reading frame

- PBD

peroxisome biogenesis disorder

- pex

peroxisome assembly mutant

- PEX

gene encoding a peroxin

- PNS

postnuclear supernatant

- PTS

peroxisome targeting signal

- THI

thiolase

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E02–02–0117. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E02–02–0117.

REFERENCES

- Aitchison JD, Murray WW, Rachubinski RA. The carboxyl-terminal tripeptide Ala-Lys-Ile is essential for targeting Candida tropicalis trifunctional enzyme to yeast peroxisomes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:23197–23203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitchison JD, Szilard RK, Nuttley WM, Rachubinski RA. Antibodies directed against a yeast carboxyl-terminal peroxisomal targeting signal specifically recognize peroxisomal proteins from various yeasts. Yeast. 1992;8:721–734. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel F, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TW, Titorenko VI, Rachubinski RA. Mutants of the Yarrowia lipolytica PEX23 gene encoding an integral peroxisomal membrane peroxin mislocalize matrix proteins and accumulate vesicles containing peroxisomal matrix and membrane proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:141–152. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane DI, Kalish JE, Gould SJ. The Pichia pastoris PAS4 gene encodes a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme required for peroxisome assembly. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21835–21844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douma AC, Veenhuis M, de Koning W, Evers M, Harder W. Dihydroxyacetone synthase is localized in the peroxisomal matrix of methanol-grown Hansenula polymorpha. Arch Microbiol. 1985;143:237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer JM, McNew JA, Goodman JM. The sorting sequence of the peroxisomal integral membrane protein PMP47 is contained within a short hydrophilic loop. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:269–280. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Schwarz E, Komaromy M, Wall R. Analysis of membrane and surface protein sequences with hydrophobic moment plot. J Mol Biol. 1984;179:125–142. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitzen GA, Aitchison JD, Szilard RK, Veenhuis M, Nuttley WM, Rachubinski RA. The Yarrowia lipolytica gene PAY2 encodes a 42-kDa peroxisomal integral membrane protein essential for matrix protein import and peroxisome enlargement but not for peroxisome membrane proliferation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1429–1436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitzen GA, Szilard RK, Rachubinski RA. Enlarged peroxisomes are present in oleic acid-grown Yarrowia lipolytica overexpressing the PEX16 gene encoding an intraperoxisomal peripheral membrane peroxin. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1265–1278. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitzen GA, Titorenko VI, Smith JJ, Veenhuis M, Szilard RK, Rachubinski RA. The Yarrowia lipolytica gene PAY5 encodes a peroxisomal integral membrane protein homologous to the mammalian peroxisome assembly factor PAF-1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20300–20306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgersma Y, Kwast L, van den Berg M, Snyder WB, Distel B, Subramani S, Tabak HF. Overexpression of Pex15p, a phosphorylated peroxisomal integral membrane protein required for peroxisome assembly in S. cerevisiae, causes proliferation of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. EMBO J. 1997;16:7326–7341. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.24.7326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgersma Y, van Roermund CW, Wanders RJ, Tabak HF. Peroxisomal and mitochondrial carnitine acetyltransferases of Saccharomyces cerevisiae are encoded by a single gene. EMBO J. 1995;14:3472–3479. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki Y. Peroxisome biogenesis and peroxisome biogenesis disorders. FEBS Lett. 2000;476:42–46. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01667-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki Y, Hubbard AL, Fowler S, Lazarow PB. Isolation of intracellular membranes by means of sodium carbonate treatment: application to endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 1982;93:97–102. doi: 10.1083/jcb.93.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover JR, Andrews DW, Rachubinski RA. Saccharomyces cerevisiae peroxisomal thiolase is imported as a dimer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994a;91:10541–10545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover JR, Andrews DW, Subramani S, Rachubinski RA. Mutagenesis of the amino targeting signal of Saccharomyces cerevisiae 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase reveals conserved amino acids required for import into peroxisomes in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1994b;269:7558–7563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman JM, Trapp SB, Hwang H, Veenhuis M. Peroxisomes induced in Candida boidinii by methanol, oleic acid and D-alanine vary in metabolic function but share common integral membrane proteins. J Cell Sci. 1990;97:193–204. doi: 10.1242/jcs.97.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould SJ, Valle D. Peroxisome biogenesis disorders: genetics and cell biology. Trends Genet. 2000;16:340–345. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould SJ, Keller G-A, Subramani S. Identification of a peroxisomal targeting signal at the carboxy terminus of firefly luciferase. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2923–2931. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould SJ, Keller G-A, Hosken N, Wilkinson J, Subramani S. A conserved tripeptide sorts proteins to peroxisomes. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1657–1664. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.5.1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould SJ, Krisans S, Keller G-A, Subramani S. Antibodies directed against the peroxisomal targeting signal of firefly luciferase recognize multiple mammalian peroxisomal proteins. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:27–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema EH, Distel B, Tabak HF. Import of proteins into peroxisomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1451:17–34. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerscher SJ, Eschemann A, Okun PM, Brandt U. External alternative NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase redirected to the internal face of the mitochondrial inner membrane rescues complex I deficiency in Yarrowia lipolytica. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3915–3921. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.21.3915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragler F, Langeder A, Raupachova J, Binder M, Hartig A. Two independent peroxisomal targeting signals in catalase A of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:665–673. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambkin GR, Rachubinski RA. Yarrowia lipolytica cells mutant for the peroxisomal peroxin Pex19p contain structures resembling wild-type peroxisomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3353–3364. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarow PB, Fujiki Y. Biogenesis of peroxisomes. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1985;1:489–530. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.01.110185.002421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarow PB, Moser HW. Disorders of peroxisome biogenesis. In: Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle AD, editors. The Metabolic Basis of Inherited Disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. pp. 2287–2324. [Google Scholar]

- McCammon MT, McNew JA, Willy PJ, Goodman JM. An internal region of the peroxisomal membrane protein PMP47 is essential for sorting to peroxisomes. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:915–925. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.6.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNew JA, Goodman JM. An oligomeric protein is imported into peroxisomes in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1245–1257. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.5.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttley WM, Brade AM, Gaillardin C, Eitzen GA, Glover JR, Aitchison JD, Rachubinski RA. Rapid identification and characterization of peroxisomal assembly mutants in Yarrowia lipolytica. Yeast. 1993;9:507–517. [Google Scholar]

- Osumi T, Tsukamoto T, Hata S, Yokota S, Miura S, Fujiki Y, Hijikata M, Miyazawa S, Hashimoto T. Amino-terminal presequence of the precursor of peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase is a cleavable signal peptide for peroxisomal targeting. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;181:947–954. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)92028-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pause B, Saffrich R, Hunziker A, Ansorge W, Just WW. Targeting of the 22 kDa integral peroxisomal membrane protein. FEBS Lett. 2000;471:23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle JR, Adams AEM, Drubin DG, Haarer BK. Immunofluorescence methods for yeasts. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:565–602. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94043-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdue PE, Lazarow PB. Peroxisome biogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:701–752. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdue PE, Takada Y, Danpure CJ. Identification of mutations associated with peroxisome-to-mitochondrion mistargeting of alanine/glyoxylate aminotransferase in primary hyperoxaluria type 1. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2341–2351. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao MJK, Argos P. A coformational preference parameter to predict helices in integral membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;869:197–214. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(86)90295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos MJ, Imanaka T, Shio H, Small GM, Lazarow PB. Peroxisomal membrane ghosts in Zellweger syndrome—aberrant organelle assembly. Science. 1988;239:1536–1538. doi: 10.1126/science.3281254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South ST, Gould SJ. Peroxisome synthesis in the absence of preexisting peroxisomes. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:255–266. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.2.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramani S. Protein import into peroxisomes and biogenesis of the organelle. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:445–478. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.002305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramani S. Components involved in peroxisome import, biogenesis, proliferation, turnover, and movement. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:171–188. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramani S, Koller A, Snyder WB. Import of peroxisomal matrix and membrane proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:399–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinkels BW, Gould SJ, Bodnar AG, Rachubinski RA, Subramani S. A novel, cleavable peroxisomal targeting signal at the amino-terminus of the rat 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase. EMBO J. 1991;10:3255–3262. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinkels BW, Gould SJ, Subramani S. Targeting efficiencies of various permutations of the consensus C-terminal tripeptide peroxisomal targeting signal. FEBS Lett. 1992;305:133–136. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80880-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilard RK, Titorenko VI, Veenhuis M, Rachubinski RA. Pay32p of the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica is an intraperoxisomal component of the matrix protein translocation machinery. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1453–1469. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terlecky SR, Fransen M. How peroxisomes arise. Traffic. 2000;1:465–473. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titorenko VI, Rachubinski RA. The life cycle of the peroxisome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:357–368. doi: 10.1038/35073063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titorenko VI, Chan H, Rachubinski RA. Fusion of small peroxisomal vesicles in vitro reconstructs an early step in the in vivo multistep peroxisome assembly pathway of Yarrowia lipolytica. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:29–44. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titorenko VI, Eitzen GA, Rachubinski RA. Mutations in the PAY5 gene of the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica cause the accumulation of multiple subpopulations of peroxisomes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20307–20314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titorenko VI, Nicaud J-M, Wang H, Chan H, Rachubinski RA. Acyl-CoA oxidase is imported as a heteropentameric, cofactor-containing complex into peroxisomes of Yarrowia lipolytica. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:481–494. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titorenko VI, Ogrydziak DM, Rachubinski RA. Four distinct secretory pathways serve protein secretion, cell surface growth, and peroxisome biogenesis in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5210–5226. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titorenko VI, Smith JJ, Szilard RK, Rachubinski RA. Pex20p of the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica is required for the oligomerization of thiolase in the cytosol and for its targeting to the peroxisome. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:403–420. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bosch H, Schutgens RBH, Wanders RJA, Tager JM. Biochemistry of peroxisomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:157–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.001105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HJ, Le Dall M-T, Waché Y, Laroche C, Belin J-M, Gaillardin C, Nicaud J-M. Evaluation of acyl-Coenzyme A oxidase (Aox) isozyme function in the n-alkane-assimilating yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5140–5148. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5140-5148.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterham HR, Titorenko VI, Haima P, Cregg JM, Harder W, Veenhuis M. The Hansenula polymorpha PER1 gene is essential for peroxisome biogenesis and encodes a peroxisomal matrix protein with both carboxy- and amino-terminal targeting signals. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:737–749. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]