Abstract

The molecular and crystal structures of six compounds containing sulfonamide moieties are described. It has been shown that the geometric parameters of the sulfonamide group depend little on the nature of the substituents. Their bond lengths and bond angles remain almost the same and are in good accordance with those known from the literature. In crystals, depending on the type of substituents the molecules exist in the form of either monomers or dimers joined by intermolecular hydrogen bonds involving sulfonamide fragments. Introduction of large substituents into the molecules changes the way of packing of the studied sulfonamides and decreases the number of intermolecular hydrogen bonds in the crystals. The value of this dihedral angle may affect the nature and strength of the intermolecular bonding of the species in crystals. In silico analyses predicted low toxicity and potential enzyme inhibition, along with antiprotozoal properties, suggesting these compounds as candidates against protozoan pathogens. Molecular docking confirmed inhibitory potential against trypanothione reductase, supporting antiprotozoal activity. Consequently, these compounds may serve as promising lead-like molecules for drug development targeting protozoan infections.

Keywords: sulfonamide derivatives, structure, target fishing, in silico, docking

1. Introduction

Sulfonamides are a significant group of therapeutic agents in contemporary medical science [1], commonly employed to treat infections caused by both Gram-positive and Gram-negative microorganisms, as well as some fungi and other microorganisms. Derivatives of this class of compounds also have diuretic, hypoglycaemic and antitumour properties, which are actively used in medical practice along with antibiotics [2–5]. Currently, the mechanisms involved in the transition of sulfonamides between immiscible liquid phases, as well as between aqueous environments and biological membrane models, which are utilized to explain variations in the pharmacological activity of these compounds, have not been thoroughly investigated. There are ideas that these properties are largely determined by the features of the molecular structure of molecules [6]. Adsmond and Grant conducted an analysis of several established crystal structures of sulfonamides, with a focus on characterizing hydrogen bond networks and organizing them using various graph notations [7]. The authors attempted to describe the donor and acceptor affinities of atoms within the studied molecules through a statistical analysis of hydrogen bonds in both solvated and unsolvated crystals. Meanwhile, Kelly and colleagues explored how iodine and nitro groups at different positions on the aryl ring affected a broad spectrum of diverse yet competitive supramolecular interactions [8].

Previously [9–19], we reported on the synthesis of several aromatic derivatives of sulfonamides and a comparative study of the features of their crystalline and molecular structure, the topology of hydrogen bonds, as well as the physicochemical characteristics of the isolated compounds: sublimation, solubility and solvation characteristics. The transfer processes of sulfonamides with different substituents on phenyl rings from water to 1-octanol were examined by analysing enthalpic and entropic components, which could offer additional mechanistic insights. This information is valuable for studying the physical stability of liquid dosage forms, particularly in processes involving temperature changes, and during the pre-formulation stage of a new drug when only a limited quantity of the drug is available. According to the obtained results, the analysis of the enthalpy–entropy relationship indicated that hydrogen bond interactions directly influence the transfer of solutes from aqueous media to 1-octanol, while hydrophobic immobilization of the solutes within phospholipid bilayers primarily determines their partitioning into liposomes.

Sulfonamide molecules have the ability to form complex hydrogen bond networks due to the presence of donor and acceptor atoms, which can influence the solubility of these substances. Therefore, a thorough investigation of sulfonamides is valuable not only for their significant practical applications but also for gaining insights into the processes involved in the dissolution and solvation of molecular crystals and their subsequent biological activity.

This study builds on our previous research, focusing on determining the molecular and crystal structures of six newly characterized sulfonamides (figure 1) that feature aromatic and aliphatic substituents, along with in silico predictions of their toxicity and biological activity.

Figure 1.

Formulae of the studied sulfonamides.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Material and reagents

All the major chemicals, including 2,4-dibromo- (I), 2-chloro- (III), 4-chloro- (IV), 2-nitro- (V), 2-chloro-4-methylaniline (VI) and diethylamine (II) with benzenesulfonyl chloride (I), 4-acetamido- (II, VI), 2-chloro-4-acetamido- (III), 2-methyl-4-acetamidobenzenesulfonyl chloride (IV, V) were purchased from Merck and Sigma-Aldrich and used as received without further purification.

2.2. Synthesis

The synthesis of sulfonamide derivatives (figure 1) was carried out according to a previously described method [17] by the reaction of a substituted aromatic amine (i.e. 2,4-dibromo- (I), 2-chloro- (III), 4-chloro- (IV), 2-nitro- (V), 2-chloro-4-methylaniline (VI) and diethylamine (II)) with benzenesulfonyl chloride (I), (4-acetamido (II, VI), 2-chloro-4-acetamido (III), 2-methyl-4-acetamido (IV, V)) benzenesulfonyl chloride, followed by hydrolytic deacetylation in an alkaline aqueous medium (approx. 1 M NaOH) and precipitation of the final product by acidification (approx. 1 M HCl) to pH 5. The compounds were meticulously purified through repeated re-crystallization from an aqueous ethanol solution. The resulting precipitates were filtered and dried under vacuum at room temperature until a constant mass was achieved. This process was repeated multiple times, with the product being analysed by 1H NMR after each re-crystallization step, until the proton NMR signals indicated a purity of >99.9% (Bruker CXP-200 spectrometer, operating frequency 200 MHz, CDCl3 solvent, internal standard tetramethylsilane). All the reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., USA, and were of 99% purity grade. The structures of all the compounds were proved by NMR studies (see electronic supplementary material, S2–S10) and X-ray analysis on single crystals. Single crystals of the isolated compounds were obtained by growing them from a water–ethanol solution (20 : 1, v/v), with ethanol vapour diffusing into the pure water. The details of the synthesis and characterization of these compounds are as follows.

N-(2,4-Dibromophenyl)benzenesulfonamide (I). 2,4-Dibromoaniline (0.13 g (0.5 mmol)) was dissolved in pyridine (10 ml), cooled to 0°C on an ice bath, and after that 0.12 ml (1 mmol) of benzenesulfonyl chloride was added to the solution and stirred for 30 min. The reaction mixture was allowed to heat up to room temperature and then stirred for an additional 12 h (TLC control). The solution was poured into 6 M HCl (20 ml), filtered off, washed with H2O (3 × 3 ml) and dried under vacuum and then in air. Yield: 0.13 g (78%); light-brown powder; m.p. 119–121°C. 1H NMR (700.2 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.76 (dd, J = 8.4, 0.9 Hz, 2H), 7.57–7.59 (m, 2H), 7.47 (dd, J = 8.4, 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.42 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (br.s, 1H). 13C NMR (176.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 133.8, 128.8, 127.8, 127.2, 126.4, 124.5 (2C), 122.4 (2C), 121.4, 119.1, 113.5. m/z [M+]: 390.8.

N-{4-[(Diethylamino)sulfonyl]phenyl}acetamide (II-Ac). Diethylamine (0.11 ml (1.1 mmol)) was dissolved in pyridine (10 ml) and cooled to 0°C on an ice bath, after which 0.5 g (2.2 mmol) of 4-acetamidobenzenesulfonyl chloride was added to the solution and stirred for 30 min. The reaction mixture was allowed to heat up to room temperature and then stirred for an additional 12 h (TLC control). The solution was poured into 6 M HCl (20 ml) and extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 15 ml). Organic layer was dried with anhydrous magnesium sulfate, concentrated under vacuum and separated by column chromatography (SiO2, 23 × 1.6 cm, eluent: heptane). Yield 0.22 g (75%); colourless oil. 1H NMR (700.2 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.75 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.60 (br.s, 1H), 3.22 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 4H), 2.22 (s, 3H), 1.13 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (176.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 168.7, 141.6, 135.2, 128.2 (2C), 119.3 (2C), 42.0 (2C), 24.7, 14.2 (2C).

4-Amino-N,N-diethylbenzenesulfonamide (II). 0.22 g (0.7 mmol) of II-Ac was dissolved in ethanol (5 ml) and a solution of 0.09 g (1.5 mmol) of potassium hydroxide in 50/50 H2O/ethanol (5 ml) was added. Resulting reaction mixture was stirred under reflux for 4 h (TLC control). Ten millilitres of H2O was poured and the resulting solution was extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 15 ml). Organic layer was dried with anhydrous magnesium sulfate, concentrated under vacuum and separated by column chromatography (SiO2, 23 × 1.6 cm, eluent: heptane). Yield 0.15 g (80%); slow crystallizing colourless oil; m.p. 121–123°C. 1H NMR (700.2 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.59 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.68 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 4.08 (br.s, 2H), 3.19 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 4H), 1.12 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (176.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 150.1, 129.1 (2C), 128.8, 114.1 (2C), 41.9 (2C), 14.1 (2C). m/z [M+]: 288.1.

For the synthesis of 4-amino-2-chloro-N-(2-chlorophenyl)benzenesulfonamide (III), 4-amino-N-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-methylbenzenesulfonamide (IV), 4-amino-2-methyl-N-(2-nitrophenyl)benzenesulfonamide (V), and 4-amino-N-(2-chloro-4-methylphenyl)benzenesulfonamide (VI), a two-step process was followed as illustrated in electronic supplementary material, figure S1. Initially, 0.1 mmol of the respective benzenesulfonamide derivative was dissolved in 20 ml of pyridine and then cooled to 0°C in an ice bath. Subsequently, 2.0 mmol of the corresponding 4-acetamidobenzenesulfonyl chloride derivative was added, and the mixture was stirred for 30 min. The reaction mixture was then allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for an additional 12 h. The solution was poured into 20 ml of 6 M HCl and extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 20 ml). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate and concentrated under vacuum. The resulting compounds were dissolved in ethanol, and a solution of potassium hydroxide (approx. 1 M) in a 1 : 1 H2O/ethanol mixture was added. The reaction mixture was then stirred under reflux for 4 h, monitored by TLC. After cooling, 10 ml of water was added, and the mixture was extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 15 ml). The organic layer was again dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, concentrated under vacuum and purified by column chromatography (SiO₂, 23 × 1.6 cm, eluent: heptane).

Compound (III): yield 75%; m.p. 128–129°C. 1H NMR (700.2 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 9.92 (NH), 5.28 (NH2), 6.49–8.00 (CHar). m/z [M+]: 315.9; compound (IV): yield 82%; m.p. 125–126°C. 1H NMR (700.2 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 9.02 (NH), 4.28 (NH2), 6.42–7.89 (CHar), 2.62 (CH3). m/z [M+]: 296.1; compound (V): yield 85%; m.p. 131–133°C. 1H NMR (700.2 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 10.12 (NH), 6.21 (NH2), 6.41–8.01 (CHar), 2.34 (CH3). m/z [M+]: 307.1; compound (VI): yield 69%; m.p. 125–128°C. 1H NMR (700.2 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 9.92 (NH), 5.28 (NH2), 6.51–8.19 (CHar), 2.74 (CH3). m/z [M+]: 296.1.

2.3. Crystallographic characteristics

Crystallographic characteristics, experimental data and structure refinement results are given in table 1. The structures were solved by the direct method [20,21] using the SHELX-86 program [22] and refined by the full-matrix least squares method in the anisotropic approximation of the displacements of all atoms, except for hydrogen atoms. Hydrogen atoms near nitrogen atoms were localized from different Fourier synthesis, and their positional and thermal parameters were refined in the isotropic approximation. The remaining hydrogen atoms were placed in geometric positions and included in the refinement in accordance with the ‘rider’ model. The calculations were performed with the SHELXTL program [23]. Crystal structures are deposited in the Cambridge Structural Database and can be freely obtained upon request.

Table 1.

The crystal data and structure refinement of I–VI.

|

compound |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

empirical formula |

C12H9Br2NO2S |

C10H16N2O2S |

C12H10Cl2N2O2S |

C14H13N2O2S |

C13H13N3O4S |

C14H13N2O2S |

|

formula weight |

391.08 |

228.31 |

317.18 |

296.76 |

307.32 |

296.76 |

|

crystal system, space group, Z |

triclinic, P-1, 2 |

monoclinic, P21/n, 4 |

triclinic, P-1, 4 |

triclinic, P-1, 4 |

monoclinic, C 1 2 /c 1, 8 |

triclinic, P-1, 8 |

|

unit cell dimensions | ||||||

|

a, b, c, Å |

7.9498(4), 8.4728(5), 10.4419(6) |

11.900(2), 8.0380(16), 12.401(3) |

7.40212(20), 12.5882(4), 14.8486(4) |

6.65752(19), 15.1117(6), 15.4039(6) |

24.3825(8), 7.5031(2), 14.8401(5) |

12.6218(3), 15.3946(4), 16.6603(5) |

|

α, β, γ, град |

78.673(5), 84.067(5), 71.548(5) |

90.00, 90.21(3), 90.00 |

80.296(3), 89.789(2), 73.500(3) |

66.111(4), 88.990(3), 77.591(3) |

90.00, 102.014(3), 90.00 |

84.010(2), 67.932(3), 66.082(3) |

|

V, Å [3] |

653.53(6) |

1186.2(4) |

1306.20(7) |

1379.68(8) |

2655.44(15) |

2738.02(12) |

|

Dcalc, g cm−3 |

1.987 |

1.278 |

1.613 |

1.429 |

1.537 |

1.440 |

|

irradiation; λ, Å |

МоKα; 0.71073 |

|||||

|

absorption coefficient μ, mm−1 |

6.353 |

0.257 |

0.257 |

0.427 |

0.265 |

0.430 |

|

Т, K |

150.01(10) |

293(2) |

150.01(10) |

150.01(10) |

150.01(10) |

150.01(10) |

|

crystal size, mm |

0.50 × 0.40 × 0.25 |

0.50 × 0.45 × 0.40 |

0.50 × 0.45 × 0.45 |

0.50 × 0.40 × 0.35 |

0.45 × 0.40 × 0.30 |

0.40 × 0.25 × 0.25 |

|

diffractometer |

Bruker XSCANS |

|||||

|

scanning type |

/ω ω/2θ |

|||||

|

Tmin, Tmax |

2.96, 31.60 |

2.86, 32.56 |

2.89, 41.15 |

3.03, 35.95 |

2.97, 41.32 |

2.82, 34.50 |

|

θ max |

29.07 |

25.62 |

41.1547 |

35.8902 |

41.35 |

35.547 |

|

index ranges |

h(−10 – 8), k(−11 – 10), l(−14 – 13) |

h(−14 – 14), k(−9 – 0), l(0 – 13) |

h(−13 – 13), k(−20 – 22), l(−27 – 26) |

h(−10 – 5), k(−24 – 24), l(−24 – 25) |

h(−45 – 45), k(−13 – 3), l(−27 – 27) |

h(−20 – 16), k(−24 – 23), l(−26 – 26) |

|

reflections collected/independent reflections with I > 2σ(I) |

3469/2795 |

2062/425 |

16 390/12 208 |

12 097/9495 |

8859/7589 |

23 145/15 275 |

|

R1 |

0.5736 |

1.6592 |

0.5283 |

0.5039 |

0.5156 |

0.9728 |

|

R1/wR2 |

0.4244 |

0.3460 |

0.3973 |

0.3661 |

0.4464 |

0.5709 |

|

S |

1.038 |

0.796 |

1.122 |

1.049 |

1.177 |

0.976 |

|

Δρmin/Δρmax, e/Å [3] |

0.001/0.000 |

0.002/0.000 |

0.001/0.000 |

0.001/0.000 |

0.001/0.000 |

0.001/0.000 |

|

ССDC |

1899994 |

1875080 |

1875322 |

1875319 |

187534 |

1875338 |

2.4. In silico target fishing

To predict the biological activity of the studied compounds, computer modelling was used in the PASS system [24]. The forecast was carried out based on two-dimensional structural formulae. Biological activity was described qualitatively by its presence or absence. The resulting prediction results included the name of the biological activity itself and estimates of the probability of manifestation (Pa) and absence (Pi), having a value from 0 to 1 with 85% probability. The toxicity of the compounds using the main routes of administration was calculated using the GUSAR program [25]. A self-consistent regression algorithm was used to generate models. The resulting prediction results included the toxicity class for various routes of administration of the studied compounds, as well as the LD50 indicator—the lethal dose for 50% of the experimental animals.

The canonical SMILES formats of the sulfonamides under study were submitted to the SwissADME server [26–28], AdmetSar [29] and ADMETlab 2 [30] to calculate various physicochemical and medicinal chemistry properties, as well as for target prediction. Additionally, the Toxtree v2.5.1 software platform was used to predict toxicity classifications [31].

To identify the manner of contact and binding energy via ligand–enzyme interaction that supports the biological activity (antiprotozoal activity) of the ligands, a molecular docking study was conducted. To prepare for molecular docking simulation, the crystal structure of trypanothione reductase (TR) complexed with 6-(sec-butoxy)-2-((3-chlorophenyl)thio)pyrimidin-4-amine was retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB entry: 5EBK) [32]. The TR protein complex was then prepared by removing all water molecules and co-crystallized ligands. Additionally, polar hydrogen atoms and partial charges were added to the structure file. For ligand preparation, the structures of individual compounds were sketched using Marvin Sketch software, followed by energy minimization using the MMFF94s force field in Avogadro software [33]. The ligands were converted to *.pdbqt format and prepared by including polar hydrogens and Gasteiger charges. The study of interaction and estimation of binding affinity of the TR protein complex with compounds through molecular docking experiments were conducted using AutoDock Vina v. 1.2.3 [34,35]. The validation of docking protocols was performed by re-docking known inhibitors (co-crystallized ligands) into their binding site in the protein model. To confirm the docked positions, root mean squared deviations (RMSD) were calculated using DockRMSD, and overlaid structures of the ligands were generated [36]. Docking parameters were set, including grid box centre coordinates for the ligand-binding site (x = −3.918, y = 19.496, z = 6.879) and the size of the box as 24 × 24 × 24. Other parameters were kept consistent with the program’s default settings. Ligands with the most negative binding energy and optimal interactions with amino acid residues in the active site were selected as the best poses. These interaction results were visualized using Discovery Studio Visualizer software.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Structure of aromatic and aliphatic sulfonamide derivatives

According to crystallographic data, the molecular structures of compounds I–VI are close to each other. As examples, the structures of the studied compounds are presented in figures 2–4 and in electronic supplementary material, figures S11–S13. Some bond lengths and bond angles of sulfonamide fragments are presented in tables 2 and 3. As can be seen, their main characteristics differ little from each other and from the values known in the literature [7–19].

Figure 2.

ORTEP representation of compound I with atom labelling (displacement ellipsoids shown at 50% probability level for non-hydrogen atoms).

Figure 4.

ORTEP representation of compound V with atom labelling (displacement ellipsoids shown at 50% probability level for non-hydrogen atoms).

Table 2.

Bond lengths (Å) of the sulfonamide fragments of compounds I–VI.

|

compound |

S–O |

S–N |

S–C |

N–C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

I |

1.433(3) 1.430(3) |

1.640(3) |

1.756(4) |

1.422(5) |

|

II |

1.455(7) 1.435(5) |

1.608(9) |

1.725(9) |

1.457(13) 1.468(11) |

|

III |

1.4344(17) 1.4404(17) |

1.6320(18) |

1.7581(19) |

1.416(3) |

|

IV |

1.4427(10) 1.4408(10) |

1.6161(12) |

1.7611(12) |

1.4281(17) |

|

V |

1.4384(11) 1.4381(11) |

1.6489(11) |

1.7487(12) |

1.4070(19) |

|

VI |

1.4363(11) 1.4383(10) |

1.6346(12) |

1.7456(14) |

1.4160(18) |

|

[10] |

1.438(5) 1.428(4) |

1.625(4) |

1.753(4) |

1.442(4) |

|

[18] |

1.439(4) 1.427(5) |

1.639(4) |

1.751(4) |

1.430(4) |

Table 3.

Some bond angles in compounds I–VI.

|

compound |

N(1)–S(1)–C(1) |

C(7)–N(1)–S(1) |

O(1)–S(1)–C(1) |

O(2)–S(1)–C(1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

I |

105.88(17) |

122.9(3) |

109.77(17) |

107.79(18) |

|

II |

110.2(4) |

122.2(8) 117.1(8) |

107.8(4) |

107.2(4) |

|

III |

106.84(9) |

124.84(15) |

110.39(10) |

106.61(10) |

|

IV |

109.90(6) |

124.00(9) |

109.90(6) |

106.43(6) |

|

V |

107.42(6) |

124.95(11) |

110.24(6) |

108.30(6) |

|

VI [10] [18] |

108.05(7) 109.0(3) 108.0(3) |

125.55(10) 119.9(30) 120.7(4) |

110.16(7) 108.9(3) 109.5(3) |

108.72(7) 108.0(4) 107.5(3) |

Figure 3.

ORTEP view of II with atom labelling scheme (displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level for non-hydrogen atoms).

In the structure of compound V (figure 4), the disordering of the aniline fragment of the molecule in two positions with 50% occupation of each position is observed, which leads to a decrease in syngony.

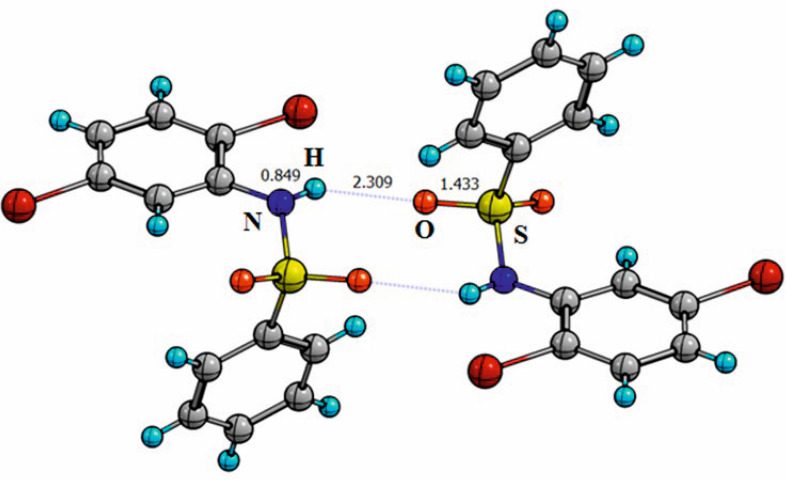

In crystals, different systems of hydrogen bonds are observed for all the compounds. In the crystal of compound I (containing no substituents in the former benzenesulfonyl chloride fragment of the molecule) centrosymmetric dimeric associates are realized with the participation of sulfonamide fragments, in which the molecules are connected by intermolecular hydrogen bonds of the N–H…O type (figure 5) with the parameters: H…O = 2.309 Å, N…O = 3.546 Å, NHO = 119.8°. This differs from previously reported structures of relevant sulfonamides [9–18] in which the lattice stabilization occurs by the formation of monomeric structures with linear systems of intermolecular N–H…O bonding. The exception is p-amino substituted sulfonamides in which the lattices are stabilized by a branched architecture of hydrogen bonds involving amino groups and sulfonamide fragments of neighbouring molecules [13,14,17,18]. Thus, it is possible to assume that the introduction of large substituents into the molecules changes the way of packing of the studied sulfonamides and decreases the number of intermolecular hydrogen bonds in the crystals.

Figure 5.

Formation of dimeric associates in the crystal structure of compound I. Intermolecular hydrogen bonds are marked as dashed lines.

In the other structures presented in this paper, intermolecular hydrogen bonds are also realized, but dimeric associates are not formed. In compound II, an intermolecular hydrogen bond N–H…O is formed between the amino group of one molecule and the oxygen of another (figure 6) with the parameters: H…N {0.5 + x, 0.5 − y, −0.5 + z} = 2.344 Å, N…O = 3.093 Å, NHO = 147.3°.

Figure 6.

Formation of an intermolecular hydrogen bond (dashed line) in compound II.

In compound III, a complex system of intermolecular hydrogen bonds of two types is realized: one N–H…N bond with parameters H…N {−x, 1 − y, 1 − z} = 2.428 Å, N…N = 3.173 Å, NHN = 155.4°, and four bonds of N–H…O type with the parameters presented in electronic supplementary material, figure S14 and table S1. In compound IV, same as in compound III, a complex system of intermolecular hydrogen bonds of two types is realized: one N–H…N bond with the parameters H…N {−x, −1 − y, −1 − z} = 2.098 Å, N…N = 2.949 Å, NHN = 77.8°, and two bonds of the N–H…O type with the parameters presented in electronic supplementary material, figure S15 and table S2. The parameters of intramolecular hydrogen bonds of V and VI are presented in electronic supplementary material, table S3 and figure S16, and in electronic supplementary material, table S4 and S17, respectively.

The angles between the planes of phenyl fragments in compounds I, III–VI are presented in table 4. As is evident, the values vary from 73.5° in compound VId to 102.3° in compound IVa, which correlates with the previously reviewed data [10]. The value of this dihedral angle may affect the nature and strength of the intermolecular bonding of the species in crystals.

Table 4.

Interplane angles of phenyl fragments in compounds I, III–VI.

|

compound |

angle (°) |

|---|---|

|

I |

101.7 |

|

IIIa IIIb |

81.2 75, 6 |

|

IVa IVb |

102.3 87.3 |

|

V |

97.8 |

|

VIa VIb VIc VId |

82.6 91.7 77.5 73.5 |

3.2. Toxicity and biological activity

Prediction of potential biological activity in the PASS system indicated that the greatest likelihood of impact was associated with inhibition of several enzymes, which is illustrated in electronic supplementary material, figure S18. In addition to inhibitory properties, compounds I–VI possess antiprotozoal (coccidial) properties with a high degree of probability (figure 7) and, therefore, can be recommended as potential drugs used against protozoan unicellular microorganisms and blood parasitic pathogens. The coccidial activity is the least for compound II with the aliphatic diethylamino fragment and reaches its maximum with the introduction of methyl substituents into the former benzenesulfonyl chloride fragment.

Figure 7.

Probability of antiprotozoal (coccidial) properties of compounds I–VI.

Prediction of acute toxicity of compounds, carried out using the GUSAR computer program, evaluates the toxic properties of compounds in relation to rodents (rats) on a five-point scale, and compounds with toxicity classes 4 and 5 are of low toxicity. The forecast results are presented in table 5.

Table 5.

Prediction of acute toxicity of compounds I–VI in relation to rodents (rats) for various routes of administration according to the LD50 classification.

|

method of administration |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

intraperitoneal |

n/ta |

4 |

n/t |

n/t |

n/t |

n/t |

|

intravenous |

n/t |

n/t |

n/t |

5 |

5 |

n/t |

|

oral |

5 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

|

subcutaneous |

5 |

5 |

n/t |

n/t |

5 |

n/t |

n/t, non-toxic.

As can be seen, according to predictions, all the described compounds are non-toxic or of low toxicity. The greatest toxic properties are predicted for compound II containing an aliphatic moiety compared with the compounds consisting of both aromatic parts. The introduction of halogen atoms and nitro groups into the composition of molecules does not increase the acute toxicity of the compounds.

The initial phases of drug design and discovery involve evaluating physicochemical properties, medicinal chemistry and ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity) computations [28,31,37,38]. According to the literature, the Lipinski (Pfizer) filter criteria for drug delivery include a molecular weight of ≤500, WLOGP of ≤4.15, a maximum of 10 (n + O) atoms, and no more than 5 (NH + OH) groups [37]. In this study, all six compounds examined met these criteria without any violations.

Among the suitable physicochemical properties of compounds I–VI for oral bioavailability, as illustrated in the radars (electronic supplementary material, figure S19), only the saturation (fraction Csp3) in compounds I and III–VI fell below the minimum threshold of 0.22. Compounds I and II were predicted to have the highest likelihood of penetrating the brain and crossing the blood–brain barrier, while compounds III–VI were anticipated to exhibit high gastrointestinal absorption, as indicated by their human intestinal absorption predictions.

Target identification, or target fishing, is a crucial stage in modern drug development that employs various methods to explore the mechanisms of action of bioactive small molecules by identifying their interacting proteins. To accelerate drug development, computational target fishing utilizes cheminformatics tools and machine learning algorithms to predict the biological targets of a chemical in silico [38]. Figure 8 presents the top 15 molecular targets and therapeutic classes for compounds I–VI. In this context, compounds I–VI primarily interact with lyases. However, compounds III, V and VI are computationally predicted to also interact with kinases. For compound I, the most likely interactions are with family A G-protein-coupled receptors and proteases.

Figure 8.

Distribution of targets in various classes for compounds I–VI.

3.3. Molecular docking simulation

The antibacterial mechanisms of action of the test molecules were forecasted through docking studies. To provide a better understanding of the molecular interaction and evaluate the inhibitory potential against TR exhibited by these six compounds, an in silico investigation of synthesized compounds was conducted using molecular docking methods. Numerous protein targets in Leishmania parasites are used for various metabolic processes, and one such protein identified as a potential drug target is TR. The results of binding affinities and interacting residues of six sulfonamides with TR are shown in table 6 and figure 9.

Table 6.

Binding affinities and interacting residues of compounds against TR.

|

compound |

binding affinity (kcal mol−1) |

hydrogen bond |

hydrophobic |

|---|---|---|---|

|

I |

−8.642 |

— |

Ile199, Cys52, Lys60, His461, Cys57, Pro336, Leu334 |

|

II |

−6.101 |

Cys52, Thr51, Ser14 |

Asp327, Cys52 |

|

III |

−7.222 |

His461, Cys57 |

Ile199, Lys60, Cys52, Cys57 |

|

IV |

−7.64 |

Asp35 |

Val34, Val36, Ala293, Phe126 |

|

V |

−7.415 |

Thr51, Ser162, Val55, Thr335 |

Ala338, Asp327, Thr51, Cys52, Met333 |

|

VI |

−7.94 |

Ser14 |

Thr160, Ala159, Ala338, Cys52, Asp327 |

Figure 9.

Two-dimensional representation of interaction within complexes between compounds I–VI and TR.

According to the literature, TR can reduce trypanothione, which is utilized by the Leishmania tryparedoxin/tryparedoxin peroxidase system to neutralize hydroperoxides produced by the host cell during infection. As a result, TR is essential for the parasite’s survival within the host. The TR-catalysed reaction mechanism involves the reduction of trypanothione disulfide (TS2) by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). This process begins with the transfer of two electrons from NADPH to the Cys52–Cys57 disulfide bridge via flavin adenine dinucleotide. Upon TS2 binding to the protein, Cys52 is deprotonated by the His461–Glu466 pair, which then attacks the trypanothione disulfide bridge, forming a mixed disulfide bridge. The reaction is completed by a subsequent attack from the protein’s second cysteine (Cys57) on Cys52, resulting in the full reduction of trypanothione [39].

The binding affinity of the six synthesized compounds when attached to TR ranges from −6.101 to −8.642 kcal mol−1, with compound I exhibiting the highest affinity at −8.642 kcal mol−1.

Compounds II, III, IV, V and VI show significant binding affinities of −6.101, −7.222, −7.64, −7.415 and −7.94 kcal mol−1, respectively. Compound I demonstrates a very strong binding, although most interactions are hydrophobic. Specifically, this compound exhibits hydrophobic interactions with Lys60, His461, Pro336, Cys57, Leu334 (in the form of pi–alkyl and alkyl interactions), Ile199 (in the form of pi–sigma interaction) and Cys52 (in the form of pi–sulfur interaction) within the active site of the TR protein. This may be associated with the special types of intermolecular association in the lattice (i.e. possibility of formation of dimeric associates).

Pi–sigma interaction with Ile199 and pi–alkyl interaction with Lys60 are also observed in the TR complex with compound III. Additionally, this compound forms two hydrogen bonds with crucial amino acid residues Cys57 and His461. The oxygen atom in the sulfonamide group of compound II establishes three hydrogen bonds with residues Cys52, Thr51 and Ser14, along with pi–anion interaction with Asp327 and pi–alkyl interaction with Cys52 on its aromatic ring. Compound IV is observed to have a hydrogen bond with Asp35 and hydrophobic interactions with Val34, Val36, Ala293 (in the form of pi–alkyl and alkyl interactions) and Phe126 (in the form of pi–sulfur interaction). Five hydrogen bonds with Thr51, Ser162, Val55 and Thr335 are present in the TR–V complex. Furthermore, compound V forms hydrophobic interactions with Cys52, Met333, Ala338, Asp327 and Thr51. Compound VI has only one hydrogen bond with Ser14 and forms hydrophobic interactions with Asp327 (in the form of pi–anion interaction), Ala159, Ala338, Cys52 (in the form of alkyl and pi–alkyl interactions) and Thr160 (in the form of amide–pi stacked interaction).

4. Conclusion

The molecular and crystal structures of six compounds containing sulfonamide moieties are described. The geometric parameters of the sulfonamide group depend little on the nature of the substituents. Their bond lengths and bond angles remain almost the same and are in good accordance with those known from the literature. This indicates the crystallographic stability of the sulfonamide fragment. In crystals, depending on the type of substituents the molecules exist in the form of either monomers or dimers joined by intermolecular hydrogen bonds involving sulfonamide fragments. Introduction of large substituents into the molecules changes the way of packing of the studied sulfonamides and decreases the number of intermolecular hydrogen bonds in the crystals. The value of this dihedral angle may affect the nature and strength of the intermolecular bonding of the species in crystals. The potential biological activity and acute toxicity of the compounds were predicted using the in silico method. Their low toxicity and potential manifestation of inhibitory properties of a series of enzymes, as well as antiprotozoal (coccidial) properties have been shown, which makes it possible to predict the possibility of using the studied sulfonamides as potential drugs against protozoan unicellular microorganisms and blood parasitic pathogens. In the drug discovery pipeline, the compounds can be considered lead-like molecules with high antimicrobial activities. The biological activity and toxicity of the compounds are associated with the nature of the substituents and nature of the hydrogen bonds in their crystals.

Contributor Information

Anh Van Nguyen, Email: anhnv@huit.edu.vn.

Anh Thi Ngoc Vu, Email: vuthingocanh@tdtu.edu.vn.

Andrey N. Utenyshev, Email: andruten@mail.ru.

Valeriy Tkachev, Email: vatka@mail.ru.

Nadezhda Polyanskaya, Email: polyanskaya-na@rudn.ru.

Dmitriy Shchevnikov, Email: shchevnikov_dm@pfur.ru.

Magrarita Vasil’eva, Email: dodokina_96@mail.ru.

Hieu Tran-Trung, Email: trantrunghieu94tc@gmail.com.

Xuan Ha Nguyen, Email: hanguyenxuan98@gmail.com.

Olga V. Kovalchukova, Email: kovalchukova-ov@rguk.ru.

Ethics

This work did not require ethical approval from a human subject or animal welfare committee.

Data accessibility

The data are available on Dryad [40].

Electronic supplementary material is available online [41].

Declaration of AI use

We have not used AI-assisted technologies in creating this article.

Authors’ contributions

A.V.N.: investigation, methodology, writing—original draft; A.T.N.V.: data curation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing; A.N.U.: formal analysis, investigation; V.T.: software, visualization; N.P.: investigation, validation; D.S.: data curation, visualization; M.V.: investigation, validation; H.T.-T.: formal analysis, investigation; X.H.N.: formal analysis, investigation; O.V.K.: conceptualization, project administration, supervision, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

The studies were performed with the state assignment no. 124013100858-3, and with the support of the RUDN Strategic Academic Leadership Program.

References

- 1. Owa T, Nagasu T. 2000. Novel sulphonamide derivatives for the treatment of cancer. Expert Opin. Ther. Patents 10, 1725–1740. ( 10.1517/13543776.10.11.1725) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abbate F, Supuran CT, Scozzafava A, Orioli P, Stubbs MT, Klebe G. 2002. Nonaromatic sulfonamide group as an ideal anchor for potent human carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: role of hydrogen-bonding networks in ligand binding and drug design. J. Med. Chem. 45, 3583–3587. ( 10.1021/jm011131t) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scozzafava A, Owa T, Mastrolorenzo A, Supuran CT. 2003. Anticancer and antiviral sulfonamides. Curr. Med. Chem. 10, 925–953. ( 10.2174/0929867033457647) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Supuran CT, Scozzafava A. 2000. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and their therapeutic potential. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 10, 575–600. ( 10.1517/13543776.10.5.575) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sehgelmeble F, et al. 2012. Sulfonimidamides as sulfonamides bioisosteres: rational evaluation through synthetic, in vitro, and in vivo studies with γ-secretase inhibitors. ChemMedChem 7, 396–399. ( 10.1002/cmdc.201200014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ucucu U, Isikdag I, Dogu H. 1995. Studies on the determination of the physicochemical parameters of some commercially available sulfonamide drugs in Turkey. Acta Pharm. Turc. 37, 134–137. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adsmond DA, Grant DJW. 2001. Hydrogen bonding in sulfonamides. J. Pharm. Sci. 90, 2058–2077. ( 10.1002/jps.1157) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kelly CJ, Skakle JMS, Wardell JL, Wardell S, Low JN, Glidewell C. 2002. Iodo-nitroarenesulfonamides: interplay of hard and soft hydrogen bonds, I...O interactions and aromatic π...π stacking interactions. Acta Crystallogr. B 58, 94–108. ( 10.1107/S0108768101016858) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Perlovich GL, Ryzhakov AM, Tkachev VV, Hansen LKr. 2011. Sulfonamide molecular crystals: thermodynamic and structural aspects. Cryst. Growth Des. 11, 1067–1081. ( 10.1021/cg1012389) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Perlovich GL, Ryzhakov AM, Tkachev VV, Hansen LKr, Raevsky OA. 2013. Sulfonamide molecular crystals: structure, sublimation thermodynamic characteristics, molecular packing, hydrogen bonds networks. Cryst. Growth Des. 13, 4002–4016. ( 10.1021/cg400666v) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nguyen VA, Vu TNA, Polyanskaya N, Utenyshev A, Shilov G, Vasil’eva M, Anh Tien N, Kovalchukova O. 2023. Structure and properties of some S-containing azo-derivatives of 5-pyrazolone and their Cu(II), Co(II), and Ni(II) metal complexes. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 158, 111648. ( 10.1016/j.inoche.2023.111648) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Nguyen A, Ngoc Vu AT, Utenyshev AN, Kovalchukova OV. 2021. Novel products of nitrosation of a series of trihydroxybenzene derivatives and their complexation with Cu(II), Cd(II) and Fe(III): synthesis, characterization, and theoretical modeling. ChemistrySelect 6, 3461–3467. ( 10.1002/slct.202100227) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kovalchukova OVV, Vu TNA, Andrey NU, Adam IS, Mikhail AR, Abbas AI TRA, Violetta KV, Leah VB. 2020. Novel Cu(II), Ni(II), Zn(II), Cd(II), and Mg(II) complexes with a series of 2-arylhydrazono-1,3-dicarbonyl compounds: synthesis, structure and spectroscopic characteristics. Polyhedron 184, 114557. ( 10.1016/j.poly.2020.114557) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perlovich GL, Tkachev VV, Kazachenko VP, Raevsky OA. 2007. 4-Amino-N-(2,5-dichlorophenyl)benzenesulfonamide. Acta Crystallogr. E 63, o1526–o1528. ( 10.1107/S1600536807008744) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perlovich GL, Kazachenko VP, Strakhova NN, Raevsky OA. 2014. Octanol/water partition coefficients of sulfonamides: experimental determination and calculation using physicochemical descriptors. J. Chem. Eng. 59, 4217–4226. ( 10.1021/je900189v) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perlovich GL, Strakhova NN, Kazachenko VP, Volkova TV, Tkachev VV, Schaper KJ, Raevsky OA. 2007. Studying thermodynamic aspects of sublimation, solubility and solvation processes and crystal structure analysis of some sulfonamides. Int. J. Pharm. 334, 115–124. ( 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.10.033) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Perlovich GL, Strakhova NN, Kazachenko VP, Volkova TV, Tkachev VV, Schaper KJ, Raevsky OA. 2008. Sulfonamides as a subject to study molecular interactions in crystals and solutions: sublimation, solubility, solvation, distribution and crystal structure. Int. J. Pharm. 349, 300–313. ( 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.07.034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perlovich GL, Tkachev VV, Strakhova NN, Kazachenko VP, Volkova TV, Surov OV, Schaper KJ, Raevsky OA. 2009. Thermodynamic and structural aspects of sulfonamide crystals and solutions. J. Pharm. Sci. 98, 4738–4755. ( 10.1002/jps.21784) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Perlovich GL, Ryzhakov AM, Strakhova NN, Kazachenko VP, Schaper KJ, Raevsky OA. 2014. Thermodynamic aspects of solubility and partitioning processes of some sulfonamides in the solvents modeling biological media. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 69, 56–65. ( 10.1016/j.jct.2013.09.027) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sheldrick GM. 2008. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A 64, 112–122. ( 10.1107/S0108767307043930) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sheldrick GM. 2015. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C 71, 3–8. ( 10.1107/S2053229614024218) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sheldrik GM. 1986. SHELX-86, program for crystal structure determination. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sheldrick GM. 2000. SHELXTL v. 6.14, structure determination software suite. Madison, WI: Brucker AXS. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Filimonov DA, Lagunin AA, Gloriozova TA, Rudik AV, Druzhilovskii DS, Pogodin PV, Poroikov VV. 2014. Prediction of the biological activity spectra of organic compounds using the PASS Online web resource. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 50, 444–457. ( 10.1007/s10593-014-1496-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lagunin A, Zakharov A, Filimonov D, Poroikov V. 2011. QSAR modelling of rat acute toxicity on the basis of PASS prediction. Mol. Informatics 30, 241–250. ( 10.1002/minf.201000151) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Daina A, Zoete V. 2016. A BOILED-Egg to predict gastrointestinal absorption and brain penetration of small molecules. ChemMedChem 11, 1117–1121. ( 10.1002/cmdc.201600182) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. 2014. iLOGP: a simple, robust, and efficient description of n-octanol/water partition coefficient for drug design using the GB/SA approach. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 54, 3284–3301. ( 10.1021/ci500467k) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. 2017. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7, 42717. ( 10.1038/srep42717) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang H, Liu C, Sun L, Li J, Cai Y, Wang Z, Li W, Liu G. 2019. admetSAR 2.0: web-service for prediction and optimization of chemical ADMET properties. Bioinformatics 35, 1067–1069. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty707) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xiong G, et al. 2021. ADMETlab 2.0: an integrated online platform for accurate and comprehensive predictions of ADMET properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W5–W14. ( 10.1093/nar/gkab255) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cheng F, Li W, Zhou Y, Shen J, Wu Z, Liu G, Lee PW, Tang Y. 2012. admetSAR: a comprehensive source and free tool for assessment of chemical ADMET properties. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 52, 3099–3105. ( 10.1021/ci300367a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bell EW, Zhang Y. 2019. DockRMSD: an open-source tool for atom mapping and RMSD calculation of symmetric molecules through graph isomorphism. J. Cheminform. 11, 40. ( 10.1186/s13321-019-0362-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Halgren TA. 1999. MMFF VI. MMFF94s option for energy minimization studies. J. Comput. Chem. 20, 720–729. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Trott O, Olson AJ. 2010. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461. ( 10.1002/jcc.21334) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eberhardt JSM, Santos-Martins D, Tillack AF, Forli SJ. 2021. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new docking methods, expanded force field, and Python bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61, 3891–3898. ( 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wan H. 2013. What ADME tests should be conducted for preclinical studies? ADMET DMPK 1, 19–28. ( 10.5599/admet.1.3.8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. 2012. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Drug Deliv. Rev. 64, 4–17. ( 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang L, Xie XQ. 2014. Computational target fishing: what should chemogenomics researchers expect for the future of in silico drug design and discovery? Future Med. Chem. 6, 247–249. ( 10.4155/fmc.14.5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Baiocco P, et al. 2013. Inhibition of Leishmania infantum trypanothione reductase by azole-based compounds: a comparative analysis with its physiological substrate by X-ray crystallography. ChemMedChem 8, 1175–1183. ( 10.1002/cmdc.201300176) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nguyen AV, Vu ATN, Utenyshev A, Tkachev V, Polyanskaya Net al. 2025. Crystallographic and Computational Characterization and in Silico Target Fishing of Six Aromatic and Aliphatic Sulfonamide Derivatives. Dryad ( 10.5061/dryad.k0p2ngfhg) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nguyen AV, Vu ATN, Utenyshev A, Tkachev V, Polyanskaya N, Shchevnikov Det al. 2025. Supplementary material from: Crystallographic and computational characterization and in silico target fishing of six aromatic and aliphatic sulfonamide derivatives. FigShare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.7644197) [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available on Dryad [40].

Electronic supplementary material is available online [41].